Abstract

Colon-specific drug delivery is critical for treating diseases of colon, such as colon cancer, amoebiasis, irritable bowel syndrome, and inflammatory bowel disease. This study reviews the effects of targeted oral drug delivery on patient by measuring the accurate administration of the drug to specific disease spot, thus enhancing the therapeutic efficacy and provides better therapeutic outcomes. Medically targeted delivery to colon produces local effect on the diseases and hinders the systemic toxic effects of drugs. The delivery of therapeutics to the specific diseased part of colon has its merits over systemic drug delivery, albeit has some obstacles and problems. Colon drug delivery can be used to create both systemic and local effects. Many advanced approaches are used, such as conventional methods for drug release to colon, delayed release dosage forms, nanoparticles, carbon nanotubes, dendrimers, and alginate coated microparticles. This concise review summarizes and elaborates the details of different techniques and strategies on targeted oral drug delivery to colon as well as studies the advantages, disadvantages, and limitations to improve the application of drug in the part of the affected colon.

Key words: Alginate, carbon nanotubes, dendrimers, drug delivery, microparticles, nanoparticles

INTRODUCTION

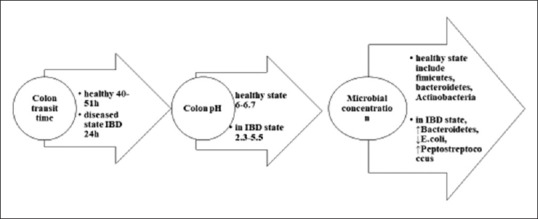

Oral route for drug administration is considered the most convenient way due to its simplicity, effectiveness, and being noninvasive method.[1] Thus, orally targeted drug delivery to colon is center of interest to treat different localized diseases, inflammatory bowel syndrome, ulcerative colitis (UC), Crohn's disease, and colorectal cancer (CRC).[2] On account of high prevalence of CRC, 1.3 million people are diagnosed with CRC per year, rated as the third deadliest cancer in world.[3] Furthermore, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), UC, Crohn's disease, and CRC need a longer duration for treatment.[4] Colon Specific Drug Delivery targets direct treatment at the diseased spots, prevents metabolism of drug in liver due to first pass metabolism, and decreases absorption of drug to system, thus enhances therapeutic efficacy.[4] Merits and demerits of CTDDs in different dosage forms has been further discussed in Table 1. Nevertheless, there are some obstacles and problems to get to this target, as gastrointestinal (GI) tract has different regions in varying environments with different pH, for example, hostile pH of the gastric region, first-pass metabolism, GI Transit, enzymes in small intestine, normal flora, and bacterial enzymes of large intestine itself. These conditions can be highly variable in the condition of diseased conditions from patient to patient. It could have significant effects on the purpose of colonic-specific drug delivery, as shown in Figure 1. Therefore, drugs need to be protected from such conditions. In this way, newer drug delivery approaches are applied, such as nanoparticles (NPs), Micro Matrix Systems, polymer-based formulations, polysaccharide-based micro/nano beads, and so forth.[5]

Table 1.

Merits and Demerits of Colon Targeted Drug Dilvery System (CTDDS)

| CTDDS | Strength | Weakness | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Nanoparticle systems | Site-specific effect, better bioavailability, and therapeutic outcomes | High cost of fabrication, need expert for design, less amount of research | [5] |

| 2 | Microparticulate systems | Microparticle systems have site specificity, high patient compliance, increased targeting to the inflamed colon | High cost of fabrication, need expert for design | [15] |

| 3 | Carbon nanotubes | Decreased toxicity but high efficacy | Safety and efficacy is not proven in human beings | [9] |

| 4 | Prodrug | Feasible, protection from FPM, localized effects of the drug | Interpatient variability can cause unintentional early drug release at undesired site or failure of drug release | [16] |

| 5 | Multi-matrix systems | Localized drug affects, low cost | Possibility of failure in drug loading fails | [17] |

| 6 | Mucoadhesive approach | Prolonged residence time, ↑ bioavailability, drug protection through GIT, local or systemic effects | Lack of in vitro models, poor organoleptic properties | [18] |

| 7 | Multiparticulate systems | Better stability, ↑ patient compliance, ↑bioavailability | ↓ drug loading, high need of excipients, unstable release | [19] |

| 8. | Biodegradable saccharide systems | Uniform dispersion through GIT uniform absorption, flexible fabrication | Drug release before colon | [20,21] |

FPM: First pass metabolism, GIT: Gastrointestinal tract, ↑: Increase, ↓: Decrease

Figure 1.

Changes in microbial and physiological pH of gastrointestinal tract in inflammatory bowel disease patient

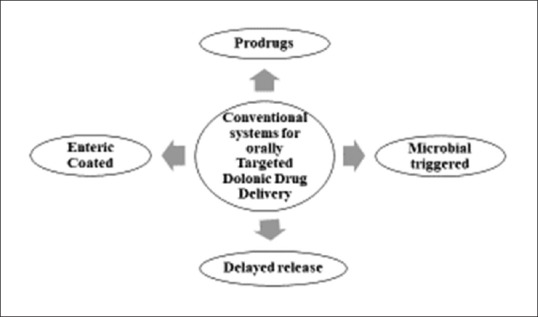

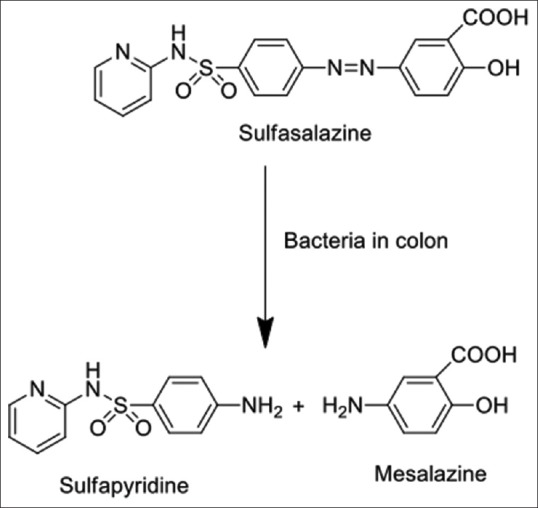

For decades, different approaches have been used to obtain specific Targeted Oral Drug Delivery conventional strategies are presented in Figure 2. In prodrug approach, inactive pharmacological drug will undergo enzymatic transformation such as of 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA), sulfasalazine, or olsalazine, as shown in Figure 3, is cleaved by the enzymes of colonic bacteria into active metabolites.[6] Azo-based anticancer prodrugs such as methotrexate, oxaliplatin, and gemcitabine have been figured out.[7] Another double prodrug novel approach was studied for benzenesulfonamide cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor using celecoxib, i.e., activated by azoreductase enzyme before releasing the drug by cyclization.[8] In cancer therapy, high doses of anti-tumor drug molecules are usually delivered to achieve maximum efficacy. However, this high dose can induce toxicity to normal organs; thus, it is recommended to produce dosage forms such as prodrugs, drugs loaded inside microspheres, liposomes, NPs, and carbon nanotubes (CNTs).[9] Xylan-5-fluorouracil conjugated to acetic acid are fabricated as a prodrug for colon cancer treatment. It shows a potential increase in drug release with reduced cytotoxicity.[10] Polymers have a great contribution in drug delivery to colon on the basis of their nature that solubilize in specific pH, can stabilize active pharmaceutical ingredient, and can control drug release, and can also be incorporated in novel systems that can eventually improve their applications and properties by working as vehicles and drug carriers.[11] Chitosan is a naturally based polymer that has been applied in the formulation of chitosan-coated poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) NPs, they are excellent carriers for delivering proteins in their active form to specific organs.[12] The formulation of chitosan-succinyl-prednisolone encoated in Eudragit L microspheres were reported by Vats et al. that toxic side-effects of drugs were reduced in rats with colitis.[13] The following peer review presents strategies and new approaches used to target colon by administering the drug orally.

Figure 2.

Conventional systems for colonic drug delivery

Figure 3.

Bacterial transformation of sulfasalazine

MINITABLETS APPROACH

Hadi et al, reported colon targeted minitablets of lornoxicam and naproxen in hidroxy propyl methyl cellulose capsule shell for rheumatoid arthritis treatment provided a uniform drug release and an excellent patient compliance.[14] These mini-tablets processing includes different techniques of formulation like the use of polymers that release drug in time-dependent manner called core mini-tablets filled with pulsincap, employing pH dependent and microsomal enzyme-dependent polymers, that are known as capsules filled with matrix mini-tablets or filled with coated mini-tablets by utilizing pH-dependent polymers.[12]

MICROSPHERES

Biodegradable polymers or protein-based microspheres having free-flowing properties and particle size 5200 nm have a variety of advantages over conventional drug delivery systems. Where the environmental factors are highly variable from patient to patient and in different diseases, they can provide localized delivery, sustained delivery, and stabilization of the sensitive drug.[36] Different kinds of matrices used in these microspheres are observed, one of them is polysaccharide-based microspheres that were introduced by Zhang et al. Acombination of prodrug approach along with multiparticulate system is reported by Vaidya et al., who explained the production of pectin metronidazole microspheres for amoebiasis treatment.[5] A microemulsion loaded with 5-ASA silicon dioxide NPs were formulated by Tang et al. for UC, with lower cytotoxicity and better efficacy.[37]

MUCOADHESIVE APPROACH

Valdecoxib mucoadhesive matrix prepared with sodium alginate and coated inside Eudragit S 100 as an anti-inflammatory drug was reported by Zhang et al. in micro and nanocarriers for colonic drug delivery.[38] Naproxen sodium mucoadhesive polymer made of sodium alginate and eudragit S100 for the treatment of colitis was prepared by Chawla et al.[26] NPs with better mucoadhesive properties are developed as reported by Chuah et al. The production of NPs made of curcumin and chitosan have a mucoadhesive drug delivery potential, thereby increasing the residence time of drug and bioavailability.[39] Ullah et al. reported the production of oxaliplatin hydrogel for colon cancer that response to pH, prepared gelatin-based oxaliplatin hydrogels suspension was biocompatible, and its 4000 mg/kg was said to be tolerable, without any kind of cytotoxicity in rabbits.[40]

MULTIMATRIX SYSTEMS

Multi-matrix systems have been produced to provide single-dose therapy, enhancing patient compliance, and efficacy of therapy, Fiorino et al. reported the multi-matrix system of mesalamine as a single dose for therapy of UC and treatment of IBD.[41] Time-dependent delivery system was used in the fabrication of dosage form for delivery of insulin to colon, as indicated by Maroni et al. chronotopic™ system where insulin was loaded into cores and coated with hydroxypropyl methylcellulose by spray drying method, with the assessment of long-term stability and efficacy.[42]

NANOPARTICLES

NPs include different types such as metallic NPs, CNTs, biodegradable polymers, and dendrimers, used in targeting drug delivery to colon are discussed briefly. NPs with their distinct and distinguished properties have shifted the medicine industry. For instance, doxorubicin loaded inside polyacrylic acid a pH-sensitive polymer with mesoporous silica SBA-15 by grafting strategy, to improve efficacy and safety of drug with good bioavailability high drug loading of 785.7 mg/g and awesome pH-susceptibility was reported by Tian et al.[43] Enzyme responding mesoporous silica NPs of 5-fluorouracil capped inside layer of guar gum was fabricated that had an excellent drug release in the presence of enzymes.[32] Ayub et al. reported improvement in the delivery of paclitaxel to cancerous cells of colon, by producing nanospheres with a layer by layer approach of cysteamine-based disulfide cross-linked sodium alginate, that had more than 70% of cell internalization.[44] Theiss et al. reported NPs delivered in hydrogel fabricated by the electrostatic interactions among sulfate ions or calcium ions of alginate and chitosan to crosslink, and these crosslinks are cleaved by colonic enzymes that make drug bioavailable. Alginate/chitosan hydrogel containing anti-inflammatory peptide Lysine-Prolin-Valine encapsulated inside NPs were applied in the treatment of dextran sodium sulfate-induced murine colitis.[45] Surface-modified paclitaxel-loaded NPs made of PLGA-polyethylene glycol (PEG) polymers were prepared by precipitation at nano level with carcinoembryonic antigen on surface to target CRC cells, that eventually provided the formulation to interact the target diseased cells.[46] Unique surface chemistry and size of NPs make them effective in targeted colon drug delivery, with enhanced permeabililty therefore they can embed and penetrate sites of inflammation through gut wall that will eventually help in better uptake of through tissues. Residential time of particles increase with reduction of size, particles below size range of 10μm accumulates in inflamed region, however nanoparticles size rang minimizes clearance of drug.[47] Moreover, NPs have versatile physicochemical properties that can be effectively applied to increase drug concentration in colon and minimize systemic side effects, some of the research done on polysaccharide based micro/nano carriers have been presented in Table 2.[48]

Table 2.

Polysaccharide-based micro/nano-carriers

| Polysacchride-based micro/nano-carriers | Model of drug | Coating materials | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Guar gum | 5-FU | Eudragit S100 | [22] |

| Dextran microspheres | rIL-2 | PLGA-PLA | [23] |

| Chitosan nanocarriers | 5-FU | Hyaluronic acid | [24] |

| Chitosan microsphere | Fe-bLf protein saturated with iron | Alginate | [25] |

| Alginate microspheres | Naproxen | Eudragit S100 | [26] |

| Pectin | 5-FU | Pellets of zinc pectin | [27] |

| Triglyceride esters | 5-FU solid lipid nanoparticles | - | [28] |

| Biodegradable mesalamine microspheres | Mesalamine microspheres | PLGA | [29] |

| Pectin nanoparticles | 5-flurouracil | Eudragit S100 | [30] |

| PHBV and PLGA nanoparticles | Oxaliplatin and 5-fluorouracil | PLGA | [31] |

| Mesoporous silica nanoparticles | 5-flurouracil | Guar gum | [32] |

| Tablets coated with high amylose corn starch | Paracetamol | High amylose starch of corn | [33] |

| Hydrogel | Lysine, valine, proline | Alginate and chitosan | [34] |

| Nano-sized hydrogel | 5-aminosalicylic acid | Chitosan | [35] |

5-FU: 5-fluorouracil, rIL-2: Recombinant interleukin-2, Fe-bLf: Bovine lactoferrin

METAL NANOPARTICLES

Metal NPs are mostly colloidal systems produced by the support of reductive technology. Some are synthesized with the help of seed-based technology, such as NPs of porous silica. When colloidal suspensions are magnetized in a liquid carrier, its ability to interact with external magnetic fields and fluidity makes them applicable medically. A recent study done by Khan et al. have synthesized nickel oxide NPs with a size range of 20–25 nm and their cytotoxicity has been evaluated showing decreased cytotoxicity; however, most metallic NPs have been reported toxic as they accumulate in the body.[49]

LIPOSOMES

Liposomes are phospholipid bilayer vesicles of nanosize that have been in use for targeted colon drug delivery as explicated by Garg et al. PEGylated Doxirubicin liposomes were reported by Alberto Gabizon that showed decrease in macrophage recognition, better biocompatibility, enhanced half-life.[50] 5-fluorouracil loaded liposomes with folic acid as ligand to target colon cells was prepared, and it is in vivo efficacy was studied where 5-FU liposomes revealed better activity in killing cancer cells.[51] Doxorubicin-loaded liposomes were fabricated and tested on Caco 2 colon cancerous cells by Neuberger et al., showed better circulation time, better drug internalization, and much lower cytotoxicity.[52]

MAGNETIC NANOPARTICLES

Heating power is generated from the magnetic fluctuation (alternating magnetic field [AMF]) in magnetic NPs (MNPs) that has been extensively applied in biomedical, particularly as a novel method for cancers and tumors therapies.[53] A previous study from Mannucci et al. shows that the natural fabrication of MNPs produced by magnetotactic bacteria is generated from MSR-1 strain of Magnetospirillum gryphiswaldense. It is anti-neoplastic activity on human colon carcinoma HT-29 cell cultures and its interaction to cells on in vivo level was assessed, that showed better uptake with no evidence of being cytotoxic.[54]

On the other hand, thermotherapy is a potent tool used in therapy of many types of tumor, unfortunately, it has poor specificity. A variety of approaches are proposed and utilized to elevate the efficacy of the technique. In this way, magnetic fluid hyperthermia goes through AMFs in which it increases tissue temperature, hence maximizing the efficiency of the method by enhancing the intra-tumoral delivery of MNPs. Creixell et al. state that the production of epidermal growth factor (EGF) adjusted to carboxymethyl dextran and encapsulated iron oxide MNPs with a better internalization in cells is monodisperse and stable, as compared to nontargeted NPs.[55]

DENDRIMERS

Dendrimers are the drug delivery systems that have excellent conjugation capacity as well as good encapsulation capacity. Recently, different types of dendrimers have been formulated and used in cancer research for targeted drug delivery. Dendrimer(s) are molecules that are linked to biologic molecules at cellular level covalently, to DNs, folic acid, antibodies, chemotherapeuticals, and contrast agents used for magnetic resonance imaging. Dendrimers conjugated to specific antibodies are more sensitive and can be extensively used to detect circulating tumor cells in detecting cancer.[56] 5-ASA was delivered to colon by dendrimer conjugates designed with polyamidoamine that is soluble in water, that was reported to have good resistance to drug release before reaching colon.[57]

CARBON NANOTUBES

Liu et al. report that the production of single-walled CNTs (SWNTs) of paclitaxel that have high suppressive activity on tumors in which the paclitaxel is insoluble in water, is linked to poly ethylated SWNTs. Consequently, it increases the water solubility and decreases the toxicity in normal cells.[9] As studied by lee et al. reported the production of C225 antibody inside SWNTs intended for targeted therapy of EGF receptor that are mostly over-expressed in colon cancer. SN38 (7-ethyl-10-hydroxycamptothecin) a topoisomerase I inhibitor is functioned to control release therapy including colon in CRC. SWNT are promising carriers for chemotherapeutic drugs.[58] Gemcitabine multi-walled CNTs loaded hyaluronic acid conjugated with polyethylene glycol were prepared to target colon cancer, and it was evaluated for in vitro and in vivo studies that showed an effective application of CNTs in colon cancer.[59] Based on the discussion of this study supported by different international journals, it is revealed that targeted drug delivery to colon is necessary. Moreover, it can maximize the therapy target, reduce drug-related adverse reactions, and drug cytotoxicity. Newer approaches such as NPs, use of polymers have enhanced therapeutic outcomes.

CONCLUSION

The strategic approaches for localized colon diseases therapies still remain an emerging field of interest with so many obstacles to focus on over time. To sum up, this study demonstrates several conventional approaches that are enhanced by the application of new technologies, making them effective in colon cancer treatment. In this regard, Nanomedicine as an emerging field has revolutionized the medicine industry and enlightens effective treatment observation of cancer around the world. That assures a controlled drug delivery to the affected spot, increasing the efficacy and decreasing the drug-related side effects. As a result, it potentially improves patient compliance and also enhances quality life of affected patients. Although many of the nano-formulations are still under research and clinical trials, a variety of crucial nanotechnological applications have been used in humans and employed in cancer evaluations, early detection, and therapy. Until now, more research and novelties are insured to legitimize the productiveness and specificity of therapies that synergizes the localized effects to treat colon diseases and to thrive thousands of opportunities lying ahead in the future. As colon is a site that functions to excrete metabolic wastes and fewer amounts of products are being absorbed in this region, thus more research is needed in this era.

Financial support and sponsorship

We would like to thanks to Academic Leadership Grants (ALG) 2019 no 1373b/UN6.O/LT/2019, Universitas Padjadjaran that funding of this study.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lu L, Chen G, Qiu Y, Li M, Liu D, Hu D, et al. Nanoparticle-based oral delivery systems for colon targeting: Principles and design strategies. Sci Bull. 2016;61:670–81. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: Sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer. 2015;136:E359–86. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jaferian S, Negahdari B, Eatemadi A. Colon cancer targeting using conjugates biomaterial 5-flurouracil. Biomed Pharmacother. 2016;84:780–8. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2016.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Agüero L, Zaldivar-Silva D, Peña L, Dias ML. Alginate microparticles as oral colon drug delivery device: A review. Carbohydr Polym. 2017;168:32–43. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2017.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vaidya A, Jain S, Agrawal RK, Jain SK. Pectin-metronidazole prodrug bearing microspheres for colon targeting. J Saudi Chem Soc. 2015;19:257–64. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sinha VR, Kumria R. Colonic drug delivery: Prodrug approach. Pharm Res. 2001;18:557–64. doi: 10.1023/a:1011033121528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sharma R, Rawal RK, Gaba T, Singla N, Malhotra M, Matharoo S, et al. Design, synthesis and ex vivo evaluation of colon-specific azo based prodrugs of anticancer agents. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2013;23:5332–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2013.07.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ruiz JF, Kedziora K, Keogh B, Maguire J, Reilly M, Windle H, et al. Adouble prodrug system for colon targeting of benzenesulfonamide COX-2 inhibitors. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2011;21:6636–40. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.09.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu Z, Chen K, Davis C, Sherlock S, Cao Q, Chen X, et al. Drug delivery with carbon nanotubes for in vivo cancer treatment. Cancer Res. 2008;68:6652–60. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sauraj, Kumar SU, Gopinath P, Negi YS. Synthesis and bio-evaluation of xylan-5-fluorouracil-1-acetic acid conjugates as prodrugs for colon cancer treatment. Carbohydr Polym. 2017;157:1442–50. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2016.09.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Avachat AM, Shinde AS. Feasibility studies of concomitant administration of optimized formulation of probiotic-loaded vancomycin hydrochloride pellets for colon delivery. Drug Dev Ind Pharm. 2016;42:80–90. doi: 10.3109/03639045.2015.1029939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hadi MA, R. Rao NG, Rao AS, Mahtab T, Tabassum S. A Review on Various Formulation Methods in preparing Colon targeted mini-tablets for Chronotherapy. Iranian J Basic Med Sci. 2018;8:158–64. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vats A, Pathak K. Exploiting microspheres as a therapeutic proficient doer for colon delivery: A review. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2013;10:545–57. doi: 10.1517/17425247.2013.759937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mohd AH, Guggilla N, Rao R, Avanapu SR. Matrix-mini-tablets of lornoxicam for targeting early morning peak symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis. Iran J Basic Med Sci. 2014;17:357–69. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lautenschläger C, Schmidt C, Lehr CM, Fischer D, Stallmach A. PEG-functionalized microparticles selectively target inflamed mucosa in inflammatory bowel disease. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2013;85:578–86. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2013.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marquez Ruiz JF, Kedziora K, O'Reilly M, Maguire J, Keogh B, Windle H. Azo-reductase activated budesodine prodrugs for colon targeting. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2012;22:7573–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Asghar LF, Chandran S. Multiparticulate formulation approach to colon specific drug delivery: Current perspectives. J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2006;9:327–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rajput GC, Majmudar FD, Patel JK, Patel KN, Thakor RS. Stomach Specific Mucoadhesive Tablets As Controlled Drug Delivery System – A Review Work. Int J Pharm Biol Res. 2010;1:30–41. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patel PB, Dhake AS. Multiparticulate approach: An emerging trend in colon specific drug delivery for Chronotherapy. J Applied Pharm Sci. 2011;1:59–63. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Patwekar SL, Baramade MK. Controlled release approach to novel multiparticulate drug delivery system. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2012;4:757–63. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sateesh Kumar V, Vijaya Kumar B. Flurbiprofen Pulsatile Colon-Specific Delivery. J Pharm Anal Insights. 2016;104:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Singh S, Kotla NG, Tomar S, Maddiboyina B, Webster TJ, Sharma D, et al. Ananomedicine-promising approach to provide an appropriate colon-targeted drug delivery system for 5-fluorouracil. Int J Nanomedicine. 2015;10:7175–82. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S89030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhao H, Wu F, Cai Y, Chen Y, Wei L, Liu Z, et al. Local antitumor effects of intratumoral delivery of rlL-2 loaded sustained-release dextran/PLGA-PLA core/shell microspheres. Int J Pharm. 2013;450:235–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2013.04.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jain A, Jain SK. Optimization of chitosan nanoparticles for colon tumors using experimental design methodology. Artif Cells Nanomed Biotechnol. 2016;44:1917–26. doi: 10.3109/21691401.2015.1111236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chonpathompikunlert P, Fan CH, Ozaki Y, Yoshitomi T, Yeh CK, Nagasaki Y. Redox nanoparticle treatment protects against neurological deficit in focused ultrasound-induced intracerebral hemorrhage. Nanomedicine (Lond) 2012;7:1029–43. doi: 10.2217/nnm.12.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chawla A, Sharma P, Pawar P. Eudragit S-100 coated sodium alginate microspheres of naproxen sodium: Formulation, optimization and in vitro evaluation. Acta Pharm. 2012;62:529–45. doi: 10.2478/v10007-012-0034-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nidhi K, Indrajeet S, Khushboo M, Gauri K, Sen DJ. Hydrotropy: A promising tool for solubility enhancement: A review. Int J Drug Dev Res. 2011;3:26–33. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yassin AE, Anwer MK, Mowafy HA, El-Bagory IM, Bayomi MA, Alsarra IA. Optimization of 5-flurouracil solid-lipid nanoparticles: A preliminary study to treat colon cancer. Int J Med Sci. 2010;7:398–408. doi: 10.7150/ijms.7.398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mahajan M, Manmode NA, Labs E. Preparation and characterization of meselamine loaded plga. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2016;3:208–14. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Perumal S, Babu S, Chandraseharan S, Suhaini M, Mohd B. Nano drug delivery strategy of 5- fluorouracil for the treatment of colorectal cancer. J Cancer Res Pract. 2017;4:45–8. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Handali S, Moghimipour E, Rezaei M, Saremy S, Dorkoosh FA. Co-delivery of 5-fluorouracil and oxaliplatin in novel poly (3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate acid)/poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid) nanoparticles for colon cancer therapy. Int J Biol Macromol. 2019;124:1299–311. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.09.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kumar B, Kulanthaivel S, Mondal A, Mishra S, Banerjee B, Bhaumik A, et al. Mesoporous silica nanoparticle based enzyme responsive system for colon specific drug delivery through guar gum capping. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2017;150:352–61. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2016.10.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bisharat L, Barker SA, Narbad A, Craig DQM. In vitro drug release from acetylated high amylose starch-zein films for oral colon-specific drug delivery. Int J Pharm. 2019;556:311–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2018.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Laroui H, Dalmasso G, Nguyen HT, Yan Y, Sitaraman SV, Merlin D, et al. Drug-loaded nanoparticles targeted to the colon with polysaccharide hydrogel reduce colitis in a mouse model. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:843–530. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saboktakin MR, Tabatabaie RM, Maharramov A, Ramazanov MA. Synthesis and characterization of chitosan hydrogels containing 5-aminosalicylic acid nanopendents for colon: Specific drug delivery. J Pharm Sci. 2010;99:4955–61. doi: 10.1002/jps.22218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hua S, Marks E, Schneider JJ, Keely S. Advances in oral nano-delivery systems for colon targeted drug delivery in inflammatory bowel disease: Selective targeting to diseased versus healthy tissue. Nanomedicine. 2015;11:1117–32. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2015.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tang H, Xiang D, Wang F, Mao J, Tan X, Wang Y. 5-ASA-loaded SiO2 nanoparticles-a novel drug delivery system targeting therapy on ulcerative colitis in mice. Mol Med Rep. 2017;15:1117–22. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2017.6153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang L, Sang Y, Feng J, Li Z, Zhao A. Polysaccharide-based micro/nanocarriers for oral colon-targeted drug delivery. J Drug Target. 2016;24:579–89. doi: 10.3109/1061186X.2015.1128941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chuah LH, Billa N, Roberts CJ, Burley JC, Manickam S. Curcumin-containing chitosan nanoparticles as a potential mucoadhesive delivery system to the colon. Pharm Dev Technol. 2013;18:591–9. doi: 10.3109/10837450.2011.640688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ullah K, Ali Khan S, Murtaza G, Sohail M, Azizullah, Manan A, et al. Gelatin-based hydrogels as potential biomaterials for colonic delivery of oxaliplatin. Int J Pharm. 2019;556:236–45. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2018.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fiorino G, Fries W, De La Rue SA, Malesci AC, Repici A, Danese S, et al. New drug delivery systems in inflammatory bowel disease: MMX and tailored delivery to the gut. Curr Med Chem. 2010;17:1851–7. doi: 10.2174/092986710791111170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Maroni A, Del Curto MD, Serratoni M, Zema L, Foppoli A, Gazzaniga A, et al. Feasibility, stability and release performance of a time-dependent insulin delivery system intended for oral colon release. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2009;72:246–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2008.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tian B, Liu S, Wu S, Lu W, Wang D, Jin L, et al. PH-responsive poly (acrylic acid)-gated mesoporous silica and its application in oral colon targeted drug delivery for doxorubicin. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2017;154:287–96. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2017.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ayub AD, Chiu HI, Mat Yusuf SNA, Abd Kadir E, Ngalim SH, Lim V, et al. Biocompatible disulphide cross-linked sodium alginate derivative nanoparticles for oral colon-targeted drug delivery. Artif Cells Nanomed Biotechnol. 2019;47:353–69. doi: 10.1080/21691401.2018.1557672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Theiss AL, Laroui H, Obertone TS, Chowdhury I, Thompson WE, Merlin D, et al. Nanoparticle-based therapeutic delivery of prohibitin to the colonic epithelial cells ameliorates acute murine colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:1163–76. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pereira I, Sousa F, Kennedy P, Sarmento B. Carcinoembryonic antigen-targeted nanoparticles potentiate the delivery of anticancer drugs to colorectal cancer cells. Int J Pharm. 2018;549:397–403. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2018.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rashid M, Kaur V, Hallan SS, Sharma S, Mishra N. Microparticles as Controlled Drug Delivery Carrier for the treatment of Ulcerative Colitis: A brief review Department of Pharmaceutics; 2 Department of Pharmacology, I.S.F. College of Saudi Pharm J. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.jsps.2014.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang S, Langer R, Traverso G. Nanoparticulate drug delivery systems targeting inflammation for treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Nano Today. 2017;16:82–96. doi: 10.1016/j.nantod.2017.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Khan S, Ansari AA, Malik A, Chaudhary AA, Syed JB, Khan AA, et al. Preparation, characterizations and in vitro cytotoxic activity of nickel oxide nanoparticles on HT-29 and SW620 colon cancer cell lines. J Trace Elem Med Biol. 2019;52:12–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jtemb.2018.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gabizon AA. Pegylated liposomal doxorubicin: Metamorphosis of an old drug into a new form of chemotherapy. Cancer Invest. 2001;19:424–36. doi: 10.1081/cnv-100103136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Handali S, Moghimipour E, Rezaei M, Ramezani Z, Kouchak M, Amini M, et al. Anovel 5-fluorouracil targeted delivery to colon cancer using folic acid conjugated liposomes. Biomed Pharmacother. 2018;108:1259–73. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.09.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Neuberger K, Boddupalli A, Bratlie KM. Regular article Effects of arginine-based surface modifications of liposomes for drug delivery in Caco-2 colon carcinoma cells. Biochem Eng J. 2018;139:8–14. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tietze R, Zaloga J, Unterweger H, Lyer S, Friedrich RP, Janko C, et al. Magnetic nanoparticle-based drug delivery for cancer therapy. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2015;468:463–70. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mannucci S, Ghin L, Conti G, Tambalo S, Lascialfari A, Orlando T, et al. Magnetic nanoparticles from Magnetospirillum gryphiswaldense increase the efficacy of thermotherapy in a model of colon carcinoma. PLoS One. 2014;9:e108959. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0108959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Creixell M, Herrera AP, Ayala V, Latorre-Esteves M, Pe´rez-Torres M, Torres-Lugo M, et al. Preparation of epidermal growth factor (EGF) conjugated iron oxide nanoparticles and their internalization into colon cancer cells. J Magn Magn Mater. 2010;322:2244–50. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Banerjee A, Pathak S, Subramanium VD, Dharanivasan G, Murugesan R, Verma RS. Strategies for targeted drug delivery in treatment of colon cancer: Current trends and future perspectives. Drug Discov Today. 2017;22:1224–32. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2017.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wiwattanapatapee R, Lomlim L, Saramunee K. Dendrimers conjugates for colonic delivery of 5-aminosalicylic acid. J Control Release. 2003;88:1–9. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(02)00461-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lee PC, Chiou YC, Wong JM, Peng CL, Shieh MJ. Targeting colorectal cancer cells with single-walled carbon nanotubes conjugated to anticancer agent SN-38 and EGFR antibody. Biomaterials. 2013;34:8756–65. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.07.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kumar S, Jain A, Shrivastava C, Kumar A. Hyaluronic acid conjugated multi-walled carbon nanotubes for colon cancer targeting. Int J Biol Macromol. 2019;123:691–703. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.11.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]