Abstract

Nephrotoxicity is defining as rapid deterioration in the kidney function due to toxic effect of medications and chemicals. There are various forms, and some drugs may affect renal function in more than one way. Nephrotoxins are substances displaying nephrotoxicity. Different mechanisms lead to nephrotoxicity, including renal tubular toxicity, inflammation, glomerular damage, crystal nephropathy, and thrombotic microangiopathy. The traditional markers of nephrotoxicity and renal dysfunction are blood urea and serum creatinine which are regarded as low sensitive in the detection of early renal damage. Thus, the detection of the initial renal injures required new biomarkers which are more sensitive and highly specific that gives an insight into the site of underlying renal damage. Kidney injury molecule-1, Cystatin C, and neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin sera levels are more sensitive than blood urea and serum creatinine in the detection of acute kidney injury during nephrotoxicity.

Key words: Cystatin C, glomerular damage, nephrotoxicity

INTRODUCTION

The kidney is the main organ required by the human body to achieve and perform different important functions including detoxification, regulation of extracellular fluids, homeostasis, and excretion of toxic metabolites.[1]

Nephrotoxicity is defining as rapid deterioration in the kidney function due to toxic effect of medications and chemicals. There are various forms, and some drugs may affect renal function in more than one way. Nephrotoxins are substances displaying nephrotoxicity. Nephrotoxicity should not be confused with the fact that some medications have a predominantly renal excretion and need their dose adjusted for the decreased renal function (e.g., heparin). The nephrotoxic effect of most drugs is more profound in patients already suffering from kidney failure. About 20% of nephrotoxicity is induced and caused by drugs; this percentage is augmented in the elderly due to an increase in the life span and poly-medications.

Aminoglycoside causes nephrotoxicity, which particularly affects the proximal tubule epithelial cells due to selective endocytosis and accumulation of aminoglycosides via the multi-ligand receptor megalin. A consensus set of phenotypic criteria for induced nephrotoxicity have recently been published. Novel renal biomarkers, in particular kidney injury molecule-1, identify proximal tubular injury earlier than traditional markers and have shown promise in observational studies. Further studies need to demonstrate a clear association with clinically relevant outcomes to inform translation into clinical practice.[2]

MECHANISM OF DRUG-INDUCED NEPHROTOXICITY

There are different mechanisms of nephrotoxicity, including renal tubular toxicity, inflammation, glomerular damage, crystal nephropathy, and thrombotic microangiopathy.[3]

Normally, the kidney preserves constant glomerular filtration rate (GFR) through regulation of afferent and efferent arterioles pressure which depends on renal prostaglandin and angiotensin II. Therefore, prostaglandin antagonists such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs), and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) lead to glomerular dysfunction.[4]

Renal proximal renal tubular cells are in contact with drugs due to tubular reabsorption and prolonged concentration processes. Toxic agents and drugs cause potential damage to the tubular transport system through the induction of oxidative stress which leads to tubular mitochondrial damage. The drugs that cause tubular damage are aminoglycoside, amphotericin B, and antivirals such as adefovir and foscarnet.[5]

Therefore, the pathogenic mechanisms of drug-induced nephrotoxicity are summarized into the followings:

Alterations of renal intraglomerular hemodynamic

Normally, about 120 mL of plasma is filtered per minute under the effect of intraglomerular pressure that maintains normal glomerular filtration; this pressure depends on the different pressure at afferent and efferent arterioles. Afferent arterioles pressure depend on the circulating prostaglandins, while efferent arterioles and intraglomerular pressures depends on the circulating angiotensin II-mediated vasoconstriction.[6] Therefore, NSAIDs like diclofenac, ARBs like valsartan, and ACEIs like captopril lead to severe deterioration of intraglomerular pressure and reduction of GFR. In addition, cyclosporine and tacrolimus cause dose-dependent afferent arteriole vasoconstrictions.[7]

Renal tubular cytotoxicity

The renal proximal tubules play a major role in eliminating waste products from the body, including drugs and their metabolites. Their active secretion and reabsorption mechanisms together with biotransformation capacity make proximal tubule cells especially sensitive to drug-induced toxicity and subsequent acute kidney injury. As well, proximal tubule epithelium stably expressing a broad range of functional transporters and metabolic enzymes that acts in concert in renal drug elimination. Renal drug transporters are highly condensed contributing to the relative high sensitivity of proximal renal tubules to the toxic agents such as antiretroviral drugs and cisplatin.[8]

Glomerulonephritis and interstitial nephritis

Glomerulonephritis is the inflammation of glomeruli caused by numerous nephrotoxic agents including gold, interferon, NSAIDs, lithium, hydralazine, and pamidronate.[9] Indeed, allergic response to the drugs may cause interstitial nephritis as in allopurinol, rifampicin, sulfonamide, lansoprazole, and quinolones. Certain drugs may cause chronic interstitial nephritis including cyclosporine, Chinese herbal medicine, and NSAIDs (>1 g/day) for 2 years. Initial and early appreciation of this condition should be recognized, because it may progress into end-stage kidney disease.[10]

Drug-induced crystal nephropathy

Many drugs produced crystals which are insoluble in the urine and precipitated within distal renal tubules, which causing interstitial reaction and obstruction. The most common drugs that generate crystals are sulfonamides, ampicillin, acyclovir, ciprofloxacin, methotrexate, and triamterene.[11] These drugs are mainly precipitated at acidic urine causing crystal nephropathy mainly in patients with renal impairment. In addition, tumor lysis during the induction of chemotherapy as in lymphoproliferative diseases causes significant uric acid and calcium deposition leading to acute renal failure.[12]

Drug-induced thrombotic microangiopathy

Drug-induced microangiopathy is due to a drug-induced immune reaction that leads to thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura and platelet activations, which eventually lead to endothelial cytotoxicity as illustrated in different medications such as ticlopidine, cyclosporine, and quinine.[13]

Drug-induced rhabdomyolysis

Different drugs may cause damage to the skeletal muscles due to direct toxic effect on the myocytes or predisposition of myocyte to the toxic effect of exercise. This damage leads to lysis of myocytes and discharge of the intracellular myoglobin and creatine kinase. Myoglobin leads to renal damage due to direct toxicity and tubular obstructions. Many drugs have been reported to produce rhabdomyolytic effect including statins, alcohol, heroin, ketamine, and cocaine.[14]

BIOMARKERS OF NEPHROTOXICITY

The traditional markers of nephrotoxicity and renal dysfunction are blood urea and serum creatinine which are specific with low sensitivity in the detection of earlier renal damage. Thus, the discovery of the initial renal injury required new biomarkers which are more sensitive and highly specific that gives an insight into the site of underlying renal damage.[15]

A urinary protein is regarded as a potential marker of acute and chronic renal damage that is induced by nephrotoxic drugs. Normally, the glomeruli restrict the transport and migration of high-molecular-weight proteins from the blood to the lumen of the nephron, but during pathological conditions, high-molecular-weight proteins can be identified and detected in the urine due to nephron dysfunction.[16] High-molecular-weight proteins such as albumin, transferrin, and immunoglobulin G are more sensitive proteins in the early detection of glomerular filtration dysfunction, glomerular damage, and structural glomerular damage, respectively.[17] Normally, low-molecular-weight proteins are mainly reabsorbed at renal proximal tubules, but when there is an excess in the amount of low-molecular-weight protein concentrations this lead to nephron overload that exceeding the proximal renal tubules reabsorbing capacity. Therefore, proximal renal tubules damage lead to low-molecular-weight proteinuria due to failure of the reabsorption capacity.[18]

Low-molecular-weight proteins such as α1-microglobulin, β2-microglobulin, Cystatin C (Cys C), retinol-binding protein, and kidney injury molecule-1 (KIM-1) are obviously recorded as the main proteins that reflect the underlying renal glomerular and/or tubular damage during nephrotoxicity.[19] Nephrotoxic agents such as cisplatin, NSAIDs, and aminoglycoside lead to upregulation of KIM-1 due to ischemic reperfusion injury. Thus serum level of KIM-1 is linked and correlated with the immune response of renal proximal tubules damage during nephrotoxicity.[20] In addition, mRNA of KIM-1 is vastly expressed in the injured kidney which is exposed into the lumen and then released into the lumen, which finally excreted in the urine. Furthermore, KIM-1 is detected in the blood since it stable and can be directly identified.[21]

Besides, neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) which is a 25 kDa protein is attached to the granulocytes; it correlated with nephrotoxicity since it is responsible for the inflammation during renal ischemia and acute renal injury.[22]

In addition, different cytokines such as interleukin (IL), interferon, and colony-stimulating factors play an important and integral role in the renal tubular damage and repair, so they are considered as biomarkers of kidney injury during drug-induced nephrotoxicity.[23]

All these biomarkers can be detected in both urine and blood for estimation of drug-induced nephrotoxicity. For that reason, measurement of urine proteins regarded as a basic test for estimation of nephrotoxicity and renal damage. Nephrotoxic agents are closely linked with acute kidney injury as well as chronic renal dysfunction. Although conventional measurement of blood urea and serum creatinine does not determine the severity of nephrotoxic-induced renal damage.[24]

Moreover, IL-18 was initially illustrated and described as inducing factor of interferon gamma which is activated by caspase-1 during apoptosis. IL-18 acts on specific receptors which found on specific cells including mast, dendritic, T-cells, and basophils cells. IL-18 is involved in the pathogenesis of obesity, inflammatory bowel diseases, and chronic kidney diseases. Besides, high IL-18 serum levels are linked with renal tubular atrophy and interstitial fibrosis. In addition, high urinary IL-18 is correlated with acute kidney injury and drug-induced nephrotoxicity. High levels of IL-18 in acute kidney injury may be a biomarker of renal injury or as a protective factor that prevents the further progression of this disease.[25,26]

Cys C was initially mentioned in 1961 as trace protein in the urine and cerebrospinal fluid in patients with renal failure. It was anticipated as a marker of renal failure in 1985. Furthermore, Cys C together with blood urea and serum creatinine is used for evaluation of renal function and GFR. Cys C is a low-molecular-weight protein excreted by glomerular filtration, so high level of Cys C is linked with reduction of GFR and glomerular filtration. It has been shown that Cys C serum levels predict the stage and progression of renal diseases. Cys C serum levels also increased in cigarette smoking, cancer, neurological, and atherosclerosis.[27]

Vitronectin (VTN) is a 70–83 kDa glycoprotein synthesized by hepatocytes and circulated in the plasma, and it was firstly described in 1967 as serum spreading factor. It colocalized with C5b-9 (active complement cascade) and immune glomerular deposit during the pathogenesis of the renal disease, thus it may promote or attenuate fibrogenesis during renal interstitial injury. VTN serum levels are correlated with fibrosis in renal diseases. Moreover, VTN binds and prolong the half-life of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 leads to more production of plasmin which has a glomerular protective effect during acute kidney injury.[28]

Integrin (ITN) is a transmembrane receptor that assists extracellular matrix adhesion, and it consists of α- and β-subunits. ITN regulates critical cell functions and homeostasis during glomerular injury through antifibrotic effect, leading to significant glomerular protection. On the other hand, ITN α2β1 may lead to glomerular injury through upregulation of collagen synthesis; therefore ITN α2β1inhibitors may be of great value in the reduction of renal damage.[29] In addition, ITN α2β1inhibitors attenuate cyclosporine-induced nephrotoxicity through inhibition of mesangial production of collagen.[30]

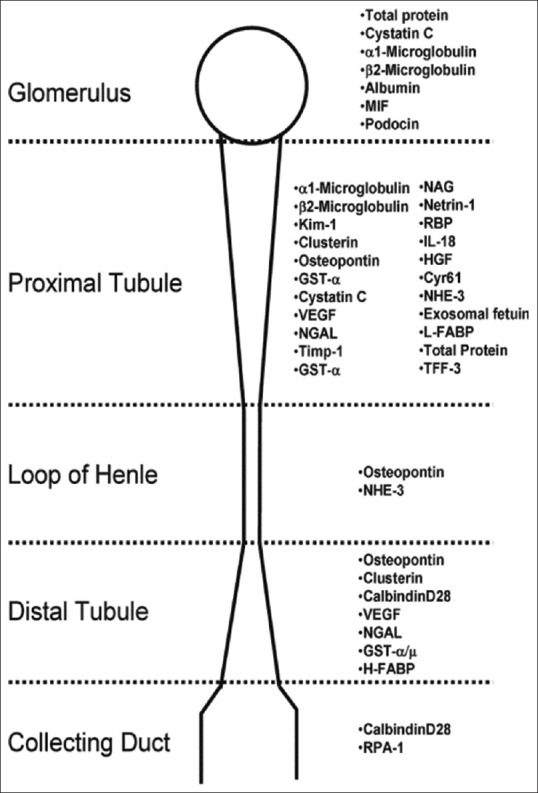

Therefore, novel and new biomarkers may help in estimation of renal damage that give an important picture about disease progression and clinical outcomes [Figure 1].[31]

Figure 1.

Biomarkers of acute injury damage and their predicted sites (Fuchs and Hewitt; 2011)

PREVENTION AND ATTENUATION OF DRUG-INDUCED NEPHROTOXICITY

The preventive strategies for prevention of drug-induced nephrotoxicity required knowledge of certain risk factors and preemptive measures which include the followings:

Patient factors

Patient older than 60 years with concomitant heart failure, dehydration, underlying chronic renal insufficiency, and diabetes mellitus are at high risk for development of acute kidney injury. Gender and genetic variations are common contributing factors into the susceptibility to drug induced-nephrotoxicity as male is more vulnerable compared with female to the nephrotoxic effects due hormonal differences. Furthermore, other factors increase risk of drug induced-renal damage is dehydration, heart failure and hepatic insufficiency.[32]

Drug factors

Some drugs are potentially and inherently nephrotoxic such as cyclosporine and aminoglycosides. As well, prolonged exposure to some drugs lead to chronic interstitial nephritis and crystal nephropathy like allopurinol. Moreover, combination of nephrotoxic drugs as in diuretic and aminoglycoside combination increases the risk of renal damage.[33]

Preventive measures

Using effective but not nephrotoxic drugs

Estimation and amelioration of underlying risk factors

Assessment of baseline renal function before the initiations of therapy

Modification of diet according to the renal functions

In risky patients, the assessment of GFR is mandatory before starting therapy

Using drugs according to the Food and Drug Administration guide

Adequate hydration and treatment of underlying acute and chronic diseases

A good communications between expertise physician and room pharmacist for drug dose monitoring and exploring the dose–response curve.[34,35,36]

RECOGNITION OF RENAL IMPAIRMENT AND EARLY INTERVENTION

The majority of renal dysfunctions induced by nephrotoxic agents are reversible, thus the main measure in this status is stopping and discontinuing the offender agents. Most nephrotoxic agents raise blood urea and serum creatinine, but in spite of that trimethoprim and cimetidine may raise serum creatinine before starting of nephrotoxic effect which may due to competition with creatinine at renal tubular secretion.[37] Serum creatinine is a more precise marker than blood urea in the evaluation of renal function since it not affected by diet. Hence, 50% rise or more than baseline creatinine by 2 mg/dL is regarded as an early sign of acute renal failure. Moreover, all medications of affected patient should be re-viewed to identify the offender nephrotoxic agent.[38]

CONCLUSION

KIM-1, Cys C, and NGAL sera levels are more sensitive than blood urea and serum creatinine in the detection of acute kidney injury during nephrotoxicity.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

The authors express deep thanks for all medical stall in department of pharmacology and clinical therapeutic.

REFERENCES

- 1.Stevens LA, Coresh J, Greene T, Levey AS. Assessing kidney function – Measured and estimated glomerular filtration rate. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2473–83. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra054415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Al-Kuraishy HM, Al-Gareeb AI, Al-Nami MS. Pomegranate attenuates acute gentamicin-induced nephrotoxicity in Sprague-Dawley rats: The potential antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2019;12:1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Al-Kuraishy HM, Al-Gareeb AI, Hussien NR. Betterment of diclofenac-induced nephrotoxicity by pentoxifylline through modulation of inflammatory biomarkers. Asian Journal of Pharmaceutical and Clinical Research. 2019;12:433–7. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lucas GN, Leitão AC, Alencar RL, Xavier RM, Daher EF, Silva Junior GB, et al. Pathophysiological aspects of nephropathy caused by non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. J Bras Nefrol. 2019;41:124–30. doi: 10.1590/2175-8239-JBN-2018-0107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vormann MK, Gijzen L, Hutter S, Boot L, Nicolas A, van den Heuvel A, et al. Nephrotoxicity and kidney transport assessment on 3D perfused proximal tubules. AAPS J. 2018;20:90. doi: 10.1208/s12248-018-0248-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Milanesi S, Verzola D, Cappadona F, Bonino B, Murugavel A, Pontremoli R, et al. Uric acid and angiotensin II additively promote inflammation and oxidative stress in human proximal tubule cells by activation of toll-like receptor 4. J Cell Physiol. 2019;234:10868–76. doi: 10.1002/jcp.27929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sudjarwo SA, Eraiko K, Sudjarwo GW, Koerniasari The potency of chitosan-Pinus merkusii extract nanoparticle as the antioxidant and anti-caspase 3 on lead acetate-induced nephrotoxicity in rat. J Adv Pharm Technol Res. 2019;10:27–32. doi: 10.4103/japtr.JAPTR_306_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Qu Y, An F, Luo Y, Lu Y, Liu T, Zhao W, et al. Anephron model for study of drug-induced acute kidney injury and assessment of drug-induced nephrotoxicity. Biomaterials. 2018;155:41–53. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2017.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frazier KS, Obert LA. Drug-induced glomerulonephritis: The spectre of biotherapeutic and antisense oligonucleotide immune activation in the kidney. Toxicol Pathol. 2018;46:904–17. doi: 10.1177/0192623318789399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Suzuki H, Yoshioka K, Miyano M, Maeda I, Yamagami K, Morikawa T, et al. Tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis (TINU) syndrome caused by the Chinese herb “Goreisan”. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2009;13:73–6. doi: 10.1007/s10157-008-0069-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pawar AT, Vyawahare NS. Anti-urolithiatic activity of standardized extract of Biophytum sensitivum against zinc disc implantation induced urolithiasis in rats. J Adv Pharm Technol Res. 2015;6:176–82. doi: 10.4103/2231-4040.165017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cosmai L, Porta C, Ronco C, Gallieni M. Acute kidney injury in oncology and tumor Lysis syndrome. Crit Care Nephrol. 2019;1:234–50. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brocklebank V, Wood KM, Kavanagh D. Thrombotic microangiopathy and the kidney. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018;13:300–17. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00620117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matsubara A, Oda S, Akai S, Tsuneyama K, Yokoi T. Establishment of a drug-induced rhabdomyolysis mouse model by co-administration of ciprofloxacin and atorvastatin. Toxicology letters. 2018;291:184–93. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2018.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Campos MA, de Almeida LA, Grossi MF, Tagliati CA. In vitro evaluation of biomarkers of nephrotoxicity through gene expression using gentamicin. J Biochem Mol Toxicol. 2018;32:e22189. doi: 10.1002/jbt.22189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Al-Kuraishy HM, Algareeb AI, Al-Windy AS. Therapeutic potential effects of pyridoxine and/or ascorbic acid on microalbuminuria in diabetes mellitus patient's: A randomized controlled clinical study. International Journal of Drug Development and Research [Internet] 2013;5:222–31. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim SY, Moon A. Drug-induced nephrotoxicity and its biomarkers. Biomol Ther (Seoul) 2012;20:268–72. doi: 10.4062/biomolther.2012.20.3.268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Al-Kuraishy HM, Al-Gareeb AI, Al-Maiahy TJ. Concept and connotation of oxidative stress in preeclampsia. Journal of laboratory physicians. 2018;10:276–82. doi: 10.4103/JLP.JLP_26_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hao Y, Huang J, Liu C, Li H, Liu J, Zeng Y, et al. Differential protein expression in metallothionein protection from depleted uranium-induced nephrotoxicity. Sci Rep. 2016;6:38942. doi: 10.1038/srep38942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alkuraishy HM, Al-Gareeb AI, Al-Naimi MS. Pomegranate protects renal proximal tubules during gentamicin induced-nephrotoxicity in rats. J Contemp Med Sci. 2019;5:35–40. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vijayasimha M, Jha RK. Kidney injury molecule-1 and its diagnostic ability in various clinical conditions. J Drug Deliv Ther. 2019;9:583–5. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Al-Kuraishy HM, Al-Gareeb AI, Rasheed HA. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects of curcumin contribute into attenuation of acute gentamicin-induced nephrotoxicity in rats. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2019;12:466–68. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eddy AA. Drug-induced tubulointerstitial nephritis: Hypersensitivity and necroinflammatory pathways. Pediatr Nephrol. 2019;28:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s00467-019-04207-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Andankar P, Shah K, Patki V. A review of drug-induced renal injury. J Pediatr Crit Care. 2018;5:36–41. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dinarello CA, Kaplanski G. Indeed, IL-18 is more than an inducer of IFN-γ. J Leukoc Biol. 2018;104:237–8. doi: 10.1002/JLB.CE0118-025RR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ferguson MA, Vaidya VS, Bonventre JV. Biomarkers of nephrotoxic acute kidney injury. Toxicology. 2008;245:182–93. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2007.12.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koksal AR, Alkim H, Boga S, Iyisoy MS, Sen I, Tekin Neijmann S, et al. Value of cystatin C-based e-GFR measurements to predict long-term tenofovir nephrotoxicity in patients with hepatitis B. Am J Ther. 2019;26:e25–31. doi: 10.1097/MJT.0000000000000518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mesnard L, Rafat C, Vandermeersch S, Hertig A, Cathelin D, Xu-Dubois YC, et al. Vitronectin dictates intraglomerular fibrinolysis in immune-mediated glomerulonephritis. FASEB J. 2011;25:3543–53. doi: 10.1096/fj.11-180752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cano-Peñalver JL, Griera M, García-Jerez A, Hatem-Vaquero M, Ruiz-Torres MP, Rodríguez-Puyol D, et al. Renal integrin-linked kinase depletion induces kidney cGMP-axis upregulation: Consequences on basal and acutely damaged renal function. Mol Med. 2016;21:873–85. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2015.00059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sardarian A, Andisheh Tadbir A, Zal F, Amini F, Jafarian A, Khademi F, et al. Altered oxidative status and integrin expression in cyclosporine A-treated oral epithelial cells. Toxicol Mech Methods. 2015;25:98–104. doi: 10.3109/15376516.2014.990595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fuchs TC, Hewitt P. Biomarkers for drug-induced renal damage and nephrotoxicity-an overview for applied toxicology. AAPS J. 2011;13:615–31. doi: 10.1208/s12248-011-9301-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Prasaja Y, Sutandyo N, Andrajati R. Incidence of cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity and associated factors among cancer patients in Indonesia. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2015;16:1117–22. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2015.16.3.1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zununi Vahed S, Ardalan M, Samadi N, Omidi Y. Pharmacogenetics and drug-induced nephrotoxicity in renal transplant recipients. Bioimpacts. 2015;5:45–54. doi: 10.15171/bi.2015.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hayati F, Hossainzadeh M, Shayanpour S, Abedi-Gheshlaghi Z, Beladi Mousavi SS. Prevention of cisplatin nephrotoxicity. J Nephropharmacol. 2016;5:57–60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sharbaf FG, Farhangi H, Assadi F. Prevention of chemotherapy-induced nephrotoxicity in children with cancer. Int J Prev Med. 2017;8:76. doi: 10.4103/ijpvm.IJPVM_40_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Whiting P, Morden A, Tomlinson LA, Caskey F, Blakeman T, Tomson C, et al. What are the risks and benefits of temporarily discontinuing medications to prevent acute kidney injury? A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ open. 2017;7:e012674. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Elsby R, Chidlaw S, Outteridge S, Pickering S, Radcliffe A, Sullivan R, et al. Mechanistic in vitro studies confirm that inhibition of the renal apical efflux transporter multidrug and toxin extrusion (MATE) 1, and not altered absorption, underlies the increased metformin exposure observed in clinical interactions with cimetidine, trimethoprim or pyrimethamine. Pharmacol Res Perspect. 2017;5:1–13. doi: 10.1002/prp2.357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Meijer-Schaap L, Van Putten JW, Janssen WM. Effects of crizotinib on creatinine clearance and renal hemodynamics. Lung Cancer. 2018;122:192–4. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2018.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]