Abstract

Background:

The key point in the production procedure of inbred animals is checking the genetic purity. Skin grafting and coat color test are used traditionally to prove genetic purity, but they have some disadvantages. Recent advances in DNA profiling have enabled scientists to check easily the genetic purity of laboratory animals. In the current study, a set of microsatellite markers was designed to check the purity of inbred laboratory mice.

Materials and Methods:

Twenty microsatellites located on 20 chromosomes were employed to create a distinctive genetic profile for parentage analysis. Each individual primer was designed based on distinguishable colors and separable sizes.

Results:

Twenty specific microsatellite markers were used in the polymerase chain reaction mixture to identify inbred BALB/cJ strains. Our results confirmed that the designed microsatellites are excellent genetic markers for testing inbred BALB/cJ strain in laboratories.

Conclusion:

Our study showed that genetic profiling using microsatellite markers allows us to detect the genetic differences of laboratory mouse species in quality control tests and validation steps.

Keywords: BALB/cJ, genetic profile, inbred, laboratory mice, microsatellite

Introduction

Animals have popularly used in biomedical and behavioral research due to remarkable benefits for human health. For example, the use of animals in experimental medicine increased notably life expectancy in the United States.[1] Among laboratory animals, small rodents, particularly rats and mice, are frequently used in quality control (QC) tests.[2] The latter also plays an important role in scientific researches.[2] Moreover, with advances in gene-editing technologies, the number of available transgenic mouse models is growing fast, and the art of managing mouse colonies is more important than ever. Therefore, colony managers often request mouse husbandry experts to develop economical and efficient techniques to determine genetically well-defined animals.[3]

Two major classes of laboratory mice include inbred and outbred strains. The first defines as a genetically homologous strain which the heterogeneity in the genome is <1% among the colony. This strain is produced by mating within a family over at least 20 generations. Due to this procedure, many genetic variants become fixed, and a specific and reliable genetic background is created in the colony. The use of such inbred mouse strains could decrease experimental variations and increase reproducibility and repeatability of in vivo tests.[4] Although inbred mice are treated as genetically identical, errors in DNA replication and germline transmissions invariably create genetic variations within an inbred strain. As a result, each mouse harbors new variations in the genome (approximately 60 loci). Although this amount of variation may not significant when considering the size of the genome, these mutations will accumulate and may become fixed in the population, causing an inbred strain to drift genetically over time.[5] This means that any inbred strain maintained for >20 generations will become genetically distinct from its parental strain. In the last 30 years, many animal vendors began to prevent this drift by the refreshing breeding stock of inbred strains from the cryopreserved embryos at defined intervals to reset this genetic clock and maintain the strain with a consistent genetic background over the time.[3] Therefore, genetic drift is no longer an issue for most commercial mice.

Nonetheless, the identification of drift during the breeding is a critical step for applying such an approach to prevent the accumulation of genetic variations in an inbred strain. Traditional methods, such as skin grafting and coat color test, are used to prove genetic purity, but these methods have some disadvantages including low accuracy, high cost, being laborious, and requirement of technical expertise.[6] On the other hand, genetically approaches have been developed and popularly recommended for this purpose as an easy, simple, and accurate method for genetic detections in many fields of medicine and health sciences.[6] Among genetic-based approaches, there has been a great deal of attention toward microsatellites. Microsatellites are repetitive short sequences with single-nucleotide regions that are abundantly distributed in the genome of eukaryotes and are used popularly as markers in genetic studies. Microsatellite markers, also known as short tandem repeats (STRs), were discovered in the 1990s.[7] They have been very valuable for gene identification by means of linkage study and gene segregation analysis for prenatal diagnosis.[8] They were used for human identification as early as 2001.[9] Since then, STR markers have been used for various purposes including quantitative fluorescence polymerase chain reaction (PCR),[10] autozygosity studies, animal parentage testing as well as animal identification.[11] STR markers are now a powerful tool for testing if an animal (e.g. laboratory animal species) are inbred or not? Therefore, in the current study, we aimed to develop a novel panel of STR markers selected from different chromosomes for testing whether different breeds of laboratory mice are inbred or not.

Materials and Methods

Microsatellite locus analysis and primer design

Using the NCBI database and Mouse Genome Informatics, locus information and sequence details of all microsatellites were obtained.[11] Primers were designed using Gene Runner software version 6.5.51 (Copyright © 1992-2018 Frank Buquicchio) according to the Whitehead Institute's MIT database [Table 1].

Table 1.

Designed markers and their sizes used in the study

| No. | Marker | Sequence | Initial size (bp) | Fluorescent color (Size) | Final size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | D10Mit230 | F: TGGCCTTGGTCTGCAAAAGT | 146 | FAM (39bp) | 185 |

| R: TTAAGAAGGGTAACAGTTGT | |||||

| 2 | D15Mit14 | F: TCCACACATATAAGCTCACAGATA | 186 | 225 | |

| R: AACCCATCAATGAACCATGTAGCC | |||||

| 3 | D3Mit55 | F: AGTTAGCTTTGAAATGGCATC | 264 | 303 | |

| R: GATCTAAGCATAAACCATACAT | |||||

| 4 | D12Mit4 | F: AAACCATCTCAAGACCAATCCAA | 303 | 342 | |

| R: TACAGTGATGCCCCATTTCAGA | |||||

| 5 | D8Mit304 | F: GCATGCACGCACACATGTG | 119 | HEX (38bp) | 157 |

| R: TTGAGGAATGAAGTCCAGGTA | |||||

| 6 | D12Mit56 | F: GCAGAGGCCACTTACTGCTGTGTC | 159 | 197 | |

| R: CACTGTAGAACAAAAGATGAGTCC | |||||

| 7 | D17Mit70 | F: AATTTTGACAACTAAGACTTA | 177 | 215 | |

| R: CCACCCACCAACTGTCTACA | |||||

| 8 | D8Mit200 | F: GCAGTACCTTGTCTAAGAATTAGAAGC | 209 | 247 | |

| R: TGCTGCTGATGTTGATGTTG | |||||

| 9 | D15Mit16 | F: AAATCCGTGGTACCTAAGAGGG | 255 | 293 | |

| R: TACACCTATCTGCTTTATTTTGCCC | |||||

| 10 | D11Mit167 | F: GCCTGAATCCTGCCAAGAG | 322 | 360 | |

| R: TCCTTGGCAAAATCCTTGAG | |||||

| 11 | D16Mit110 | F: CAGAGAATCCCCACCTTGAA | 96 | NED (39bp) | 135 |

| R: GGTACCATGGATATCAAGTATGAGC | |||||

| 12 | D11Mit179 | F: TTTGGCATTCACATGTAGGTC | 135 | 174 | |

| R: TTGCTTTATAATCTTTCTCTGTGTG | |||||

| 13 | D11Mit224 | F: CCTCAAGCCCTGAGTTTGAT | 214 | 253 | |

| R: CTCCTTTTTAAGACAAAACATCAACTA | |||||

| 14 | D9Mit2 | F: TTCTGCTGGATTCTGTTGA | 289 | 328 | |

| R: AAATGGAGACAGGTAAAAACA | |||||

| 15 | D13Mit78 | F: ATCAAAGTGTAAAGTGCTTG | 297 | 336 | |

| R: GGTTGCCAGCTATGCCTGCCAG | |||||

| 16 | D12Mit263 | F: TCCCCTGGAGCATATTTGAC | 130 | PET (39bp) | 169 |

| R: TCAGATCTCAGCAGATAAATACTTGG | |||||

| 17 | D1Mit17 | F: CAAGCTTGTACACAAAATGC | 175 | 214 | |

| R: TCCCCTGCTGGCCTCCTTGG | |||||

| 18 | D13Mit66 | F: CCAACTTCAGCCATAAGACAG | 214 | 253 | |

| R: ACTATGGACAAGGGTTGAAGC | |||||

| 19 | D2Mit51 | F: ATTTCAGGGCCTGGGGAGATGG | 285 | 324 | |

| R: CCCTTATTGTTTTGAGACGGGGTC | |||||

| 20 | D1Mit15 | F: TCCATGAAGAAACCCATGC | 320 | 359 | |

| R: CCAAGAGAAGAAATATCAGC |

DNA samples

The number of mice was computed using the following formula to detect the herd contamination with a prevalence of 10%.

S = log (p)/log (U)

Fifty BALB/cJ mice (6–8 weeks) were used for the study, and samples were obtained by cutting the ends of the mice's tail after local anesthesia. DNA purification was performed from the samples as follow. 288 μl lysis buffer (584 mg NaCl, 93 mg ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid disodium, 125 mg sodium dodecyl sulfate, 5 ml 1M tris buffer, up to 50 ml) and 6 μl proteinase K were added to 1.5 ml microtube containing 2 mm of the tail. The samples were then incubated at 55°C for overnight. After incubation, 1 ml of ethanol 100% was added to the mixture and mixed well. The samples were then centrifuged for 30 min at 16,000 g. The precipitate was washed with 1 ml 70% alcohol and re-centrifuged 16,000 g for 20 min. The supernatant was discarded, and the precipitate was dissolved in 300 μl ddH2O by a 2 h incubation at 55°C. Finally, the samples were kept at −20°C for further analysis.

Multiplex polymerase chain reactions

At first, distilled water, 10x buffer, 100 mM MgCl2, 40 mM dNTP, forward and reverse primers (100 pM), Taq DNA polymerase (1 unit), and DNA of each sample (200 ng/μl) were added into the 0.2 μl microtubes and mixed well. The microtubes were then inserted into a thermocycler device, and multiplex PCR was performed according to the following program (95°C for 5 min [1 cycle]; 95°C for 1 min, 60°C for 1.5 min, and 70°C for 2 min [30 cycles]; and 70°C for 15 min [1 cycle]). To ensure multiplex PCR works correctly, the PCR products were electrophoresed on 1% agarose gel. Then, the samples were subjected to a genetic analyzer (ABI 3130XL Genetic Device) for further analysis.

Examination of polymerase chain reaction products using genetic analyzer

PCR products were evaluated to measure the amount of each marker using the ABI 3130XL Genetic Device. Briefly, 17 μl methanol was added into the samples and heated to 95°C for 5 min. Then, the samples were placed on ice for 3 min, and 1 μl of each product was applied to the device. The GeneMapper software was used to analyze the results in FASTA format.

Results

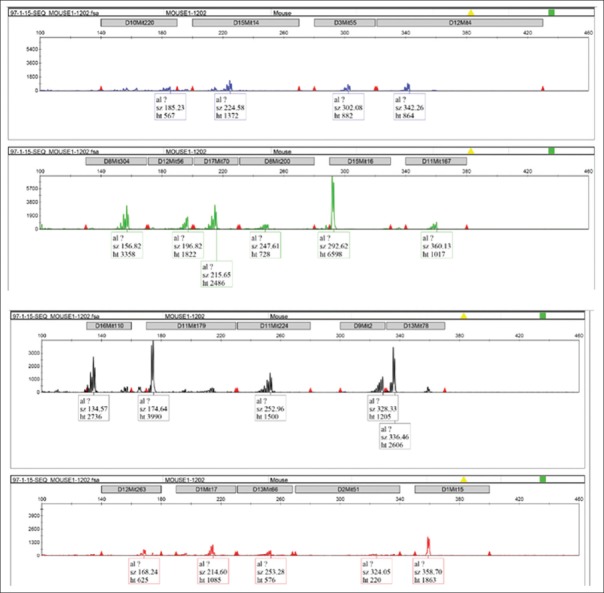

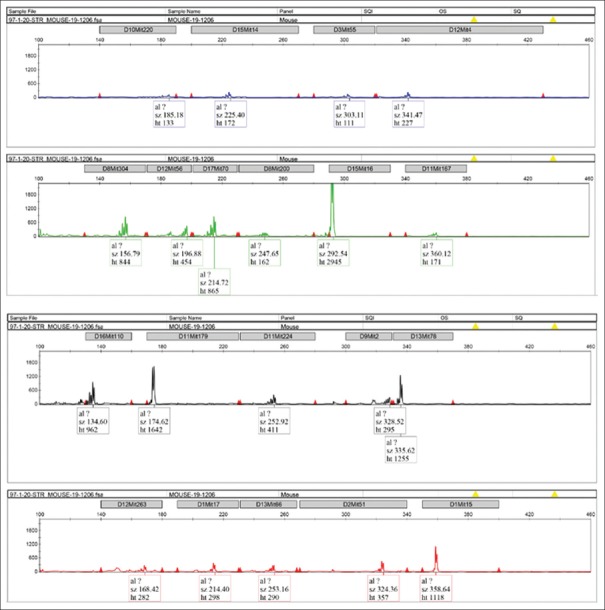

Genomic DNA from the samples was purified and subjected to the multiplex PCR. After confirmation by agarose gel electrophoresis, the samples were applied to the capillary electrophoresis, and the data were analyzed by a genetic analyzer. For example, DNA microsatellite graphs for mouse numbers 1 and 19 were shown in Figures 1 and 2, respectively. The size of each amplified marker is presented in Table 2. The results were matched well with the data compared to Jackson database for inbred BALB/cJ species. The only marker that has a slight difference between the study and database was D16Mit110 (135 bp vs. 139 bp), which did not adequate for the difference in heredity.

Figure 1.

DNA microsatellite graphs regarding to mouse number 1

Figure 2.

DNA microsatellite graphs regarding to mouse number 19

Table 2.

The PCR product size (bp) of each marker obtained for the samples

| D1Mit15 | D2Mit51 | D13Mit66 | D1Mit17 | D12Mit263 | D13Mit78 | D9Mit2 | D11Mit224 | D11Mit179 | D16Mit110 | D11Mit167 | D15Mit16 | D8Mit200 | D17Mit70 | D12Mit56 | D8Mit304 | D12Mit4 | D3Mit55 | D15Mit14 | D10Mit230 | Mice no. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 359 | 324 | 253 | 214 | 169 | 336 | 328 | 253 | 174 | 135 | 360 | 293 | 247 | 215 | 197 | 157 | 342 | 303 | 225 | 185 | 1 |

| 359 | 324 | 253 | 214 | 169 | 336 | 328 | 253 | 174 | 135 | 360 | 293 | 247 | 215 | 197 | 157 | 342 | 303 | 225 | 185 | 2 |

| 359 | 324 | 253 | 214 | 169 | 336 | 328 | 253 | 174 | 139 | 360 | 293 | 247 | 215 | 197 | 157 | 342 | 303 | 225 | 185 | 3 |

| 359 | 324 | 253 | 214 | 169 | 336 | 328 | 253 | 174 | 135 | 360 | 293 | 247 | 215 | 197 | 157 | 342 | 303 | 225 | 185 | 4 |

| 359 | 324 | 253 | 214 | 169 | 336 | 328 | 253 | 174 | 135 | 360 | 293 | 247 | 215 | 197 | 157 | 342 | 303 | 225 | 185 | 5 |

| 359 | 324 | 253 | 214 | 169 | 336 | 328 | 253 | 174 | 135 | 360 | 293 | 247 | 215 | 197 | 157 | 342 | 303 | 225 | 185 | 6 |

| 359 | 324 | 253 | 214 | 169 | 336 | 328 | 253 | 174 | 135 | 360 | 293 | 247 | 215 | 197 | 157 | 342 | 303 | 225 | 185 | 7 |

| 359 | 324 | 253 | 214 | 169 | 336 | 328 | 253 | 174 | 135 | 360 | 293 | 247 | 215 | 197 | 157 | 342 | 303 | 225 | 185 | 8 |

| 359 | 324 | 253 | 214 | 169 | 336 | 328 | 253 | 174 | 139 | 360 | 293 | 247 | 215 | 197 | 157 | 342 | 303 | 225 | 185 | 9 |

| 359 | 324 | 253 | 214 | 169 | 336 | 328 | 253 | 174 | 135 | 360 | 293 | 247 | 215 | 197 | 157 | 342 | 303 | 225 | 185 | 10 |

| 359 | 324 | 253 | 214 | 169 | 336 | 328 | 253 | 174 | 135 | 360 | 293 | 247 | 215 | 197 | 157 | 342 | 303 | 225 | 185 | 11 |

| 359 | 324 | 253 | 214 | 169 | 336 | 328 | 253 | 174 | 135 | 360 | 293 | 247 | 215 | 197 | 157 | 342 | 303 | 225 | 185 | 12 |

| 359 | 324 | 253 | 214 | 169 | 336 | 328 | 253 | 174 | 139 | 360 | 293 | 247 | 215 | 197 | 157 | 342 | 303 | 225 | 185 | 13 |

| 359 | 324 | 253 | 214 | 169 | 336 | 328 | 253 | 174 | 135 | 360 | 293 | 247 | 215 | 197 | 157 | 342 | 303 | 225 | 185 | 14 |

| 359 | 324 | 253 | 214 | 169 | 336 | 328 | 253 | 174 | 135 | 360 | 293 | 247 | 215 | 197 | 157 | 342 | 303 | 225 | 185 | 15 |

| 359 | 324 | 253 | 214 | 169 | 336 | 328 | 253 | 174 | 135 | 360 | 293 | 247 | 215 | 197 | 157 | 342 | 303 | 225 | 185 | 16 |

| 359 | 324 | 253 | 214 | 169 | 336 | 328 | 253 | 174 | 135 | 360 | 293 | 247 | 215 | 197 | 157 | 342 | 303 | 225 | 185 | 17 |

| 359 | 324 | 253 | 214 | 169 | 336 | 328 | 253 | 174 | 135 | 360 | 293 | 247 | 215 | 197 | 157 | 342 | 303 | 225 | 185 | 18 |

| 359 | 324 | 253 | 214 | 169 | 336 | 328 | 253 | 174 | 135 | 360 | 293 | 247 | 215 | 197 | 157 | 342 | 303 | 225 | 185 | 19 |

| 359 | 324 | 253 | 214 | 169 | 336 | 328 | 253 | 174 | 135 | 360 | 293 | 247 | 215 | 197 | 157 | 342 | 303 | 225 | 185 | 20 |

| 359 | 324 | 253 | 214 | 169 | 336 | 328 | 253 | 174 | 135 | 360 | 293 | 247 | 215 | 197 | 157 | 342 | 303 | 225 | 185 | 21 |

| 359 | 324 | 253 | 214 | 169 | 336 | 328 | 253 | 174 | 135 | 360 | 293 | 247 | 215 | 197 | 157 | 342 | 303 | 225 | 185 | 22 |

| 359 | 324 | 253 | 214 | 169 | 336 | 328 | 253 | 174 | 135 | 360 | 293 | 247 | 215 | 197 | 157 | 342 | 303 | 225 | 185 | 23 |

| 359 | 324 | 253 | 214 | 169 | 336 | 328 | 253 | 174 | 135 | 360 | 293 | 247 | 215 | 197 | 157 | 342 | 303 | 225 | 185 | 24 |

| 359 | 324 | 253 | 214 | 169 | 336 | 328 | 253 | 174 | 135 | 360 | 293 | 247 | 215 | 197 | 157 | 342 | 303 | 225 | 185 | 25 |

| 359 | 324 | 253 | 214 | 169 | 336 | 328 | 253 | 174 | 139 | 360 | 293 | 247 | 215 | 197 | 157 | 342 | 303 | 225 | 185 | 26 |

| 359 | 324 | 253 | 214 | 169 | 336 | 328 | 253 | 174 | 135 | 360 | 293 | 247 | 215 | 197 | 157 | 342 | 303 | 225 | 185 | 27 |

| 359 | 324 | 253 | 214 | 169 | 336 | 328 | 253 | 174 | 135 | 360 | 293 | 247 | 215 | 197 | 157 | 342 | 303 | 225 | 185 | 28 |

| 359 | 324 | 253 | 214 | 169 | 336 | 328 | 253 | 174 | 135 | 360 | 293 | 247 | 215 | 197 | 157 | 342 | 303 | 225 | 185 | 29 |

| 359 | 324 | 253 | 214 | 169 | 336 | 328 | 253 | 174 | 135 | 360 | 293 | 247 | 215 | 197 | 157 | 342 | 303 | 225 | 185 | 30 |

| 359 | 324 | 253 | 214 | 169 | 336 | 328 | 253 | 174 | 135 | 360 | 293 | 247 | 215 | 197 | 157 | 342 | 303 | 225 | 185 | 31 |

| 359 | 324 | 253 | 214 | 169 | 336 | 328 | 253 | 174 | 139 | 360 | 293 | 247 | 215 | 197 | 157 | 342 | 303 | 225 | 185 | 32 |

| 359 | 324 | 253 | 214 | 169 | 336 | 328 | 253 | 174 | 135 | 360 | 293 | 247 | 215 | 197 | 157 | 342 | 303 | 225 | 185 | 33 |

| 359 | 324 | 253 | 214 | 169 | 336 | 328 | 253 | 174 | 135 | 360 | 293 | 247 | 215 | 197 | 157 | 342 | 303 | 225 | 185 | 34 |

| 359 | 324 | 253 | 214 | 169 | 336 | 328 | 253 | 174 | 135 | 360 | 293 | 247 | 215 | 197 | 157 | 342 | 303 | 225 | 185 | 35 |

| 359 | 324 | 253 | 214 | 169 | 336 | 328 | 253 | 174 | 135 | 360 | 293 | 247 | 215 | 197 | 157 | 342 | 303 | 225 | 185 | 36 |

| 359 | 324 | 253 | 214 | 169 | 336 | 328 | 253 | 174 | 135 | 360 | 293 | 247 | 215 | 197 | 157 | 342 | 303 | 225 | 185 | 41 |

| 359 | 324 | 253 | 214 | 169 | 336 | 328 | 253 | 174 | 135 | 360 | 293 | 247 | 215 | 197 | 157 | 342 | 303 | 225 | 185 | 42 |

| 359 | 324 | 253 | 214 | 169 | 336 | 328 | 253 | 174 | 135 | 360 | 293 | 247 | 215 | 197 | 157 | 342 | 303 | 225 | 185 | 43 |

| 359 | 324 | 253 | 214 | 169 | 336 | 328 | 253 | 174 | 135 | 360 | 293 | 247 | 215 | 197 | 157 | 342 | 303 | 225 | 185 | 44 |

| 359 | 324 | 253 | 214 | 169 | 336 | 328 | 253 | 174 | 135 | 360 | 293 | 247 | 215 | 197 | 157 | 342 | 303 | 225 | 185 | 45 |

| 359 | 324 | 253 | 214 | 169 | 336 | 328 | 253 | 174 | 135 | 360 | 293 | 247 | 215 | 197 | 157 | 342 | 303 | 225 | 185 | 46 |

| 359 | 324 | 253 | 214 | 169 | 336 | 328 | 253 | 174 | 135 | 360 | 293 | 247 | 215 | 197 | 157 | 342 | 303 | 225 | 185 | 47 |

| 359 | 324 | 253 | 214 | 169 | 336 | 328 | 253 | 174 | 135 | 360 | 293 | 247 | 215 | 197 | 157 | 342 | 303 | 225 | 185 | 48 |

| 359 | 324 | 253 | 214 | 169 | 336 | 328 | 253 | 174 | 139 | 360 | 293 | 247 | 215 | 197 | 157 | 342 | 303 | 225 | 185 | 49 |

| 359 | 324 | 253 | 214 | 169 | 336 | 328 | 253 | 174 | 139 | 360 | 293 | 247 | 215 | 197 | 157 | 342 | 303 | 225 | 185 | 50 |

Discussion

Today, biomedical research using laboratory animal is widespread and has great importance in diagnosis and drug development.[2] Therefore, scientists are mainly looking for animal models that have the lowest genetic variation to gain accurate and reliable results.[12] Using inbred species is one of the most important ways to achieve this goal.[13] Inbred populations are in fact colonies generated by at least 20 subsequent mating cycles from the first generation. In this system, the populations are genetically similar in their genomic natures. In fact, the strains obtained are ideal models for biological, pharmaceutical, and clinical assays. In another word, the genetic changes affecting the biomedical experiments in these species are very low. Different parentage verification and/or monitoring systems were developed and tested for inbred horses. However, among them, the usefulness of microsatellite markers was frequently proved by many investigations on different animal species. In a study, 17 STRs on different locations in the chromosomes were tested for parentage analysis of polish cold blood and Hucul horses. Although their parents were only excluded in a single locus, deviations were mainly observed in the loci. They concluded that DNA typing complications of some STR sequences, sex linkage of STRs as well as the null allelic occurrence were the source of wrong parentage exclusion.[14] In another study, 45 Caspian horses were genotyped for individual identification. Genotype evaluations were carried out by PCR using seven microsatellite markers. All studied microsatellite markers have high polymorphic information content value. They successfully used DNA typing for parentage testing and individual identification of Iranian horses.[15] In a similar investigation, 79 Jeju horses were genotyped using 20 microsatellites for parentage testing. The number of alleles and the polymorphic information contents ranged from 5 to 11 and 0.335–0.816, respectively. The total exclusion probability of the microsatellites was approximately one, and therefore, genotyping of Jeju horses using developed microsatellites was useful for tracking any genetic deviation in the species.[16] In a study by Takasu et al., 31 microsatellite DNAs were employed for genotyping 125 endangered Kiso horses, which 83% of horses were breed. They found that inbreeding level was low and the horses have experienced a rapid loss of population. They concluded that parentage testing using designed microsatellites was highly reliable with a probability of exclusion.[17] Their work confirmed microsatellite markers are also useful for monitoring of wild genetic diversity and could be considered as a powerful tool in maintenance management of wild-type species. In another study by Moshkelani et al., 14 microsatellite markers were successfully used for identification and parentage testing of Iranian Arab horses. The average heterozygosity and the expected of heterozygosity were 0.656 and 0.697 in the population, respectively.[18] Luis et al. used six microsatellites for parentage testing in different Portuguese autochthonous horse breeds. Microsatellite loci were selected based on the polymorphism detected in other breeds. They also compared traditional techniques such as blood groups and protein polymorphisms with microsatellite DNAs in the same breeds. Surprisingly, the results showed that the microsatellite sets are comparable for paternity assignment of two breeds as shown by the high average exclusion probability values.[19]

Conclusion

In this study, BALB/cJ laboratory mice were evaluated in term of genetic purity for biotechnological applications using microsatellite markers. In our research work, 20 microsatellites located on 20 chromosomes were employed to create a distinctive genetic profile. Each individual primer was designed based on distinguishable colors and separable sizes. Our data proposed that the designed STR markers could be considered for genetic testing of BALB/cJ mice in QC tests of pharmaceutical laboratories.

Financial support and sponsorship

This project was financially supported by Pasteur Institute of Iran (Grant No. 615).

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to express their deep gratitude to all who provided support during the course of this research.

References

- 1.Mishra S. Does modern medicine increase life-expectancy: Quest for the moon rabbit? Indian Heart J. 2016;68:19–27. doi: 10.1016/j.ihj.2016.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Franco NH. Animal experiments in biomedical research: A historical perspective. Animals (Basel) 2013;3:238–73. doi: 10.3390/ani3010238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lambert R. A Jackson Laboratory Resource Manual. Bar Harbor, ME 04609 USA, The Jackson Laboratory; 2007. Breeding strategies for maintaining colonies of laboratory mice; pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Festing MF. Evidence should trump intuition by preferring inbred strains to outbred stocks in preclinical research. ILAR J. 2014;55:399–404. doi: 10.1093/ilar/ilu036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lacy RC. Importance of genetic variation to the viability of mammalian populations. J Mammal. 1997;78:320–35. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Flurkey K, Currer JM, Leiter EH, Witham B. The Jackson Laboratory Handbook on Genetically Standardized Mice. Sixth Edition. Bar Harbor, ME 04609 USA, The Jackson Laboratory; 2009. pp. 1–363. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vieira ML, Santini L, Diniz AL, Munhoz Cde F. Microsatellite markers: What they mean and why they are so useful. Genet Mol Biol. 2016;39:312–28. doi: 10.1590/1678-4685-GMB-2016-0027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Montaldo HH, Meza-Herrera CA. Use of molecular markers and major genes in the genetic improvement of livestock. Electron J Biotechnol. 1998;1:15–6. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lander ES, Linton LM, Birren B, Nusbaum C, Zody MC, Baldwin J, et al. Initial sequencing and analysis of the human genome. Nature. 2001;409:860–921. doi: 10.1038/35057062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vahab Saadi A, Kushtagi P, Gopinath P, Satyamoorthy K. Quantitative fluorescence polymerase chain reaction (QF-PCR) for prenatal diagnosis of chromosomal aneuploidies. Int J Hum Genet. 2010;10:121–9. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rebelato AB, Caetano AR. Runs of homozygosity for autozygosity estimation and genomic analysis in production animals. Pesquisa Agropecuária Bras. 2018;53:975–84. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Van der Worp HB, Howells DW, Sena ES, Porritt MJ, Rewell S, O'Collins V, et al. Can animal models of disease reliably inform human studies? PLoS Med. 2010;7:e1000245. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brenner S, Miller JH, Broughton W. Encyclopedia of Genetics. Copyright© 2001 Elsevier Science Inc. ISBN: 978-0-12-227080-2. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ząbek T, Fornal A. Evaluation of the 17-plex STR kit for parentage testing of polish Coldblood and Hucul horses. Ann. Anim. Sci. 2009;9(4):363–372. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seyedabadi H, Amirinia C, Banabazi MH, Emrani H. Parentage verification of Iranian Caspian horse using microsatellites markers. Iran J Biotechnol. 2006;4:260–4. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Choi SK, Cho CY, Yeon SH, Cho BW, Cho GJ. Genetic characterization and polymorphisms for parentage testing of the Jeju horse using 20 microsatellite loci. J Vet Med Sci. 2008;70:1111–5. doi: 10.1292/jvms.70.1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Takasu M, Hiramatsu N, Tozaki T, Kakoi H, Nakagawa T, Hasegawa T, et al. Genetic characterization of endangered Kiso horse using 31 microsatellite DNAs. J Vet Med Sci. 2011;74(2):161–6. doi: 10.1292/jvms.11-0025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moshkelani S, Rabiee S, Javaheri-Koupaei MJ. DNA fingerprinting of Iranian Arab horse using fourteen microsatellites marker. Research Journal of Biological Sciences. 2011;6:402–5. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Luis C, Cothran E, Oom M. Microsatellites in Portuguese autochthonous horse breeds: Usefulness for parentage testing. Genet Mol Biol. 2002;25:131–4. [Google Scholar]