Abstract

Episodic memory impairment is a hallmark for early diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease. Most actual tests used to diagnose Alzheimer's disease do not assess the spatiotemporal properties of episodic memory and lead to false-positive or -negative diagnosis. We used a newly developed, nonverbal navigation test for Human, based on the objective experimental testing of a spatiotemporal experience, to differentially Alzheimer's disease at the mild stage (N = 16 patients) from frontotemporal lobar degeneration (N = 11 patients) and normal aging (N = 24 subjects). Comparing navigation parameters and standard neuropsychological tests, temporal order memory appeared to have the highest predictive power for mild Alzheimer's disease diagnosis versus frontotemporal lobar degeneration and normal aging. This test was also nonredundant with classical neuropsychological tests. As a conclusion, our results suggest that temporal order memory tested in a spatial navigation task may provide a selective behavioral marker of Alzheimer's disease.

Introduction

Pathophysiology in Alzheimer's disease (AD) is associated with medial temporal lobe dysfunction (Seab et al., 1988; Jobst et al., 1992; Scahill et al., 2002; Thompson et al., 2003). Already during the initial stages of AD, tau pathology is found in the medial temporal lobe (Braak and Braak, 1991; Van Hoesen et al., 1991). Marked hippocampal atrophy with tau- and amyloid-related lesions are specific to AD. Indeed, hippocampal atrophy specifically predicts conversion to AD in mild cognitive impairment (MCI) (Trivedi et al., 2006; Chupin et al., 2009) and hippocampal function differentiates AD from normal aging and frontotemporal lobe degeneration (FTLD)— the second most common dementia after Alzheimer's disease (Rabinovici et al., 2007; Drzezga et al., 2008).

This hippocampal locus of early AD pathology is consistent with spatiotemporal orientation impairments in everyday activities (Pai and Jacobs, 2004), such as difficulties in finding one's way in unfamiliar environments in both patients with prodromal AD—the symptomatic predementia phase (deIpolyi et al., 2007; Cushman et al., 2008)—and AD patients (Bird et al., 2010). Correspondingly, patients with mild AD are impaired for spatial memory (Kessels et al., 2005; Hort et al., 2007; Cushman et al., 2008) as well as for spatiotemporal memory (Cherrier et al., 2001; Kalová et al., 2005; deIpolyi et al., 2007).

According to the new diagnostic criteria (Dubois et al., 2010), hippocampal-dependent episodic memory impairment appears as a major and “core” criterion to be associated with one supportive criterion based on biomarkers or genetics, for early diagnosis of AD. To take care of Alzheimer patients as early as possible, a simple behavioral tool that specifically diagnoses Alzheimer's disease early on is of major importance.

However, defining a behavioral task that is sufficient to provide a satisfactory diagnosis is still a challenge. Limitations of the memory tests used in clinic primarily concern their unsatisfactory differential diagnostic power (Elfgren et al., 1994; Chen et al., 2000; Simons et al., 2002; Thompson et al., 2005; Tierney et al., 2005). One possible reason for this is that memory tests used in clinic do not model proper hippocampal function. Indeed, most tests can be resolved without reference to a spatiotemporal context, which precisely depends on hippocampal function (for review, see Burgess et al., 2002).

Our aim was to develop a sensitive and specific behavioral nonverbal marker of mild AD. We hypothesized that AD would be best diagnosed by a test assessing spatiotemporal memories acquired through active navigation, because this requires hippocampal function (Maguire et al., 1998; Burgess et al., 2002; Iglói et al., 2010).

Here we use a paradigm consisting in the creation of a nonverbal spatiotemporal memory using the Starmaze navigation task (Rondi-Reig et al., 2006; Iglói et al., 2009, 2010), which activates the hippocampus in young healthy subjects (Iglói et al., 2010). We tested three age groups of healthy volunteers and FTLD, amnestic MCI (aMCI), and AD patients to disentangle age- and AD pathology-related impairments compared with a battery of other standard neuropsychological tests.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

Patients with AD (N = 16, 8 males and 8 females), amnestic mild cognitive impairment (aMCI, N = 14, 10 males and 4 females) or FTLD (N = 11, 6 males and 5 females) were recruited from the Memory Center of the Salpêtrière Hospital. Sixty-three healthy controls also participated in this study. They were divided into three age groups (20–39, N = 20, 9 males and 11 females, 40–59, N = 19, 10 males and 9 females, 60–80 years old, N = 24, 11 males and 13 females).

All patients with AD, aMCI and FTLD were evaluated by a neurologist with experience in cognitive and behavioral neurology. The neurological interview included an investigation of depression symptoms and, when the neurologist judged necessary, the Montgomery Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (Montgomery and Åsberg, 1979) was used to assess depressive state (in this case, a score >16 of 60 was considered as pathological). All subjects (patients and controls) underwent a neuropsychological examination that included the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) (Folstein et al., 1975); the free and cued selective reminding test (FCSRT) (Grober and Buschke, 1987) for verbal episodic memory; the delayed recall of the Rey figure (RCFT) (Rey, 1993) for visual memory; the Frontal Assessment Battery (FAB) (Dubois et al., 2000) for executive functions; the Corsi Block-Tapping Task (Corsi, 1972) with the forward version (CBT-F, testing the exact recall of a spatial sequence) for visuospatial span, and the backward version (CBT-B, testing the recall of a spatial sequence backwards) for working memory (Kessels et al., 2008). Gestual praxis and visuoconstructive function were tested by copying the Rey figure (RCFT) (Rey, 1993), and by MMSE pentagons. Clinical severity of the disease was assessed by the Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) (Berg, 1988; Morris, 1993). In addition, all patients underwent the Verbal Fluency test (letter S and category: fruit in 2 min) (Kremin et al., 1999). When dementia other than that observed in AD was clinically suspected, an additional specific neuropsychological battery was administered to increase the specificity of the clinical diagnosis using tests to assess orbitofrontal function for frontal variant of FTLD, semantic memory for semantic dementia, and language for progressive non-fluent aphasia.

Subjects who presented any of the following were excluded: 1) systemic illnesses that could interfere with cognitive functioning; 2) major depression; 3) score on MMSE lower than 15; 4) history of stroke, 5) clinical or neuroimaging evidence of focal lesions or presence of subcortical vascular lesions on brain MRI; 6) visual deficit that could interfere with the performance on the experimental task (all subjects should have normal vision or corrected to normal vision).

Patients with AD (N = 16) fulfilled the NINCDS-ADRDA (Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders Association) criteria (McKhann et al., 1984) and the new research criteria for AD (Dubois et al., 2010). All AD patients had progressive amnesia of the medial temporal type (Dubois et al., 2007) characterized by a low free recall not normalized with cueing (Dubois and Albert, 2004), and at least one positive in vivo marker of AD pathology among the following: CSF amyloid β; total tau and phospho-tau. All AD patients had a CDR score >0.5.

Patients with aMCI (N = 14) had progressive amnesia of the medial temporal type, without other cognitive impairment, and without impairment of normal daily life activities. Their CDR was of 0.5.

Patients with FTLD (N = 11) were included according to consensual criteria (Neary et al., 1998; McKhann et al., 2001). This group included patients presenting the following clinical profiles: (1) frontal variant of FTLD (N = 5) characterized by decline in behavior and executive functioning, (2) semantic dementia (N = 3), associated with fluent progressive aphasia, impaired word comprehension, and poor object knowledge, and (3) progressive non-fluent aphasia (N = 3), associated with effortful speech and impaired grammatical comprehension.

Healthy adults were also included (N = 63), among whom there were 24 healthy old adults (60–80 years old), age-matched to patients. The young adults were recruited from university or public announcements. Old adults were recruited from social clubs for retired people and none had impaired activities of daily living. All healthy controls underwent a short clinical interview to exclude medical disorders that could interfere with cognitive performance and underwent the same neuropsychological assessment as patients. Normal controls had no neurological complaints nor symptoms of depression, had normal neuropsychological examinations, and had preserved daily life functioning (CDR = 0).

Computer experience was quantified using a scale ranging from 0 to 3. A score of 0 corresponded to no or sparse computer experience. If the subject frequently used a computer, a score of 1 was given. Playing 2D computer games corresponded to a score of 2, and playing games implemented in virtual reality corresponded to a score of 3. Patients and age-matched controls (60–80 group) were matched for computer ability according to this scale.

We obtained written informed consent from all subjects according to the Declaration of Helsinki (BMJ 1991; 302: 1194) and the study was approved by the Pitié Salpêtriere Ethics Committee.

Experimental procedure and analysis of behavioral data

Virtual environment

The virtual reality Starmaze, designed with 3D StudioMax (Autodesk Fortune 1000) and made interactive with Virtools (v3.5) (Dassault Systèmes), comprised five central alleys forming a pentagon and five alleys radiating from the angles of the central pentagon (Fig. 1A). Participants used a joystick to move their viewpoint forward or backward or to turn left or right; they could move around and perform rotations freely in all of the alleys. Distant environmental cues surround the maze for orientation (Fig. 1B). These cues were placed between the ends of adjacent alleys and every cue was present twice around the maze, so that solving the task required knowledge of the spatial configuration of cues rather than a guidance strategy based on a single cue. Participants were told to find a goal that would always be at the same place in the environment. The goal had no visible identifiers but, when it was reached, a virtual gift went off to indicate the successful end of the trial, thus providing feedback. Participants knew that the environment would not change during the experiment. Before testing started, subjects spent a few minutes moving freely in one alley of the environment to practice the motor aspects of the task. They were taught to observe the landscape by turning without moving forward. As soon as subjects were comfortable with the joystick, the experiment started.

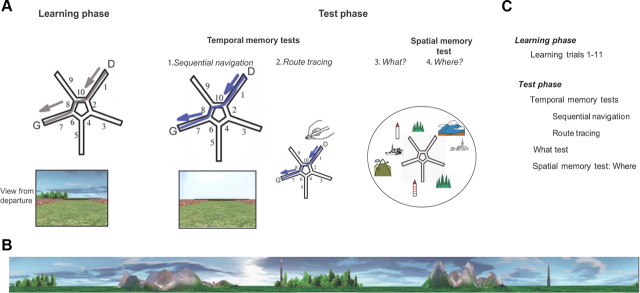

Figure 1.

The Starmaze task. A, Tasks performed. The Starmaze is composed of a central pentagonal ring (alleys 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10) from which five centrally symmetric alleys (1, 3, 5, 7, and 9) radiate. D, Departure alley; G, goal alley, where a virtual reward appeared when the subject reached the goal. The learning phase. Subjects were told to navigate toward a fixed hidden reward (G), with the most direct path possible, starting from the same departure point (D). The ideal path toward the goal is shown in gray. For the first three learning trials, if the subject had not found the reward within time or distance limits, he was placed at the entrance of the goal alley (7) and an arrow indicated the way to the reward. The test phase. The temporal memory tests. (1) Sequential navigation: All environmental cues were removed; the virtual environment only consisted of the walls boarding the alleys. Participants were told to reproduce the sequence of turns performed on the last learning trial. (2) Route tracing: Participants had to trace the path they had performed on the last learning trial on a map of the maze. The “what” test: Participants were asked to name the visual cues they had seen in the environment (“what”). The spatial memory test-“where” test: Subjects had to place the recalled cues on the map of the Starmaze. B, Configuration of the virtual environment. The landmarks consisted of two different mountains and villages, two distinct forests and two antennas, which were located between the ends of two adjacent alleys. To encourage the participants to encode the relationships between environmental landmarks, these landmarks were presented in sets of two. C, Succession of tests.

The experiment consisted of learning trials followed by the temporal and spatial memory tests (see Fig. 1C for complete trial order). During the learning phase, successful navigation could be supported by either type of representation: sequential egocentric (sequence of body-turns), allocentric (location relative to environmental cues) (see also Iglói et al., 2009, 2010) or a combination of both. During this phase, healthy subjects learned both the sequential egocentric and the allocentric strategies in parallel (Iglói et al., 2009). Therefore, they learned a sequence of movements leading to the goal, and also the configuration of external landmarks surrounding the maze.

Learning phase

The learning phase consisted of 11 learning trials. A trial ended either when a subject reached the goal location, or after the 90 s time-limit, except if after the 90 s time-limit the subject had not traveled the minimum distance in the maze (corresponding to four central and three peripheral alleys); in which case the trial ended when this amount of distance was traveled. One exception was the first three learning trials: if subjects failed to reach the goal within these conditions on time and distance, they were placed in the goal alley and were told to reach the goal by going straight forward.

Every 200 ms, the exact position of the subject was registered in a Cartesian coordinate system. Learning performance was measured by two parameters: percentage of successful trials and percentage of direct trials (Fig. 2). Successful trials corresponded to the trials where a subject reached the goal within the time or distance limit. Direct trials corresponded to the trials where a subject reached the goal without entering any peripheral alley different from the arrival alley.

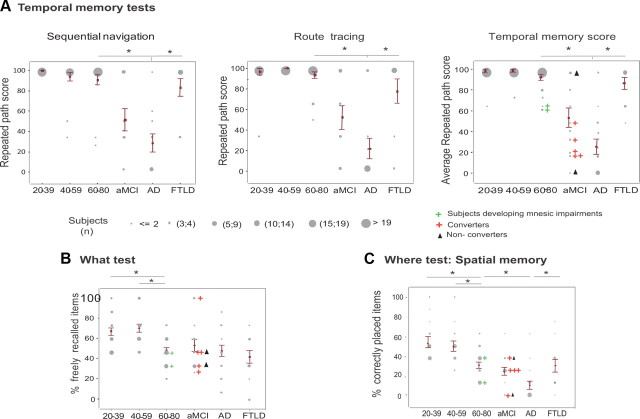

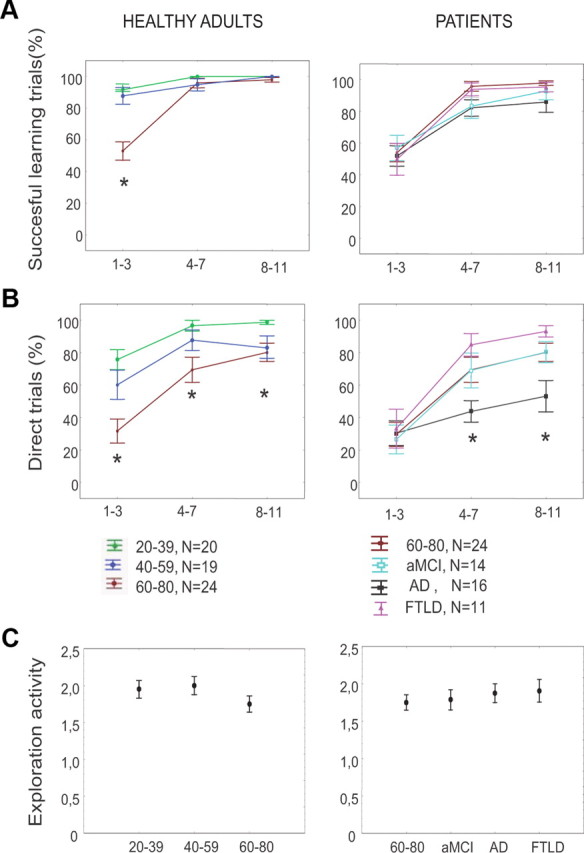

Figure 2.

Navigation performance in healthy adults (left) and patients (right) during the learning phase. Shown are the evolutions of navigation performances over learning trials, in each group. For display purposes, learning trials were grouped in three blocks (trials 1–3, 4–7, and 8–11). A, Percentage of successful learning trials, as defined by the capacity to reach the goal within the time and distance limits. B, Percentage of trials with direct paths to the goal. C, Exploration activity, defined as the number of peripheral alleys (excluding the start arm) that were visited during the first learning trial for the first time, and taken as a control of exploration activity. *p < 0.05, Group effect.

An exploration mark was defined as the number of entries in peripheral alleys (Fig. 1, alleys 1, 3, 5, 7, and 9) during the first trial of the learning phase. This score was previously used by Moffat et al. (2001). This measure was used to control that old and young subjects did not differ in their initial exploration of the environment, i.e., that all subjects were equally able to move and turn in the virtual environment.

Test phase

Temporal memory tests.

The temporal memory tests, called sequential navigation and route tracing, were performed after the 11th trial. They both aim at testing the subject's ability to have memorized the sequence of body turns. In both tests, subjects were told to reproduce the exact same trajectory as the one performed during the last trial of the learning phase (learning trial 11 or T11).

Sequential navigation.

Right after the learning phase, subjects were told to reproduce the exact sequence of body-turns performed during the last trial (T11). To test for the temporal aspect of sequential navigation, all environmental cues were removed (Fig. 1A1). The trial ended when a peripheral alley was fully visited.

Route tracing.

In the route tracing test, subjects had to trace the route that they had taken on the last learning trial on a table-top drawing of the Starmaze provided to the subject (Fig. 1A2). Correct answers were not provided after these tests.

Both temporal tests are scored using the repeated path score. The sequence performed on T11 is taken as reference. We compare the behavior of the subject at each choice point with the behavior at the same choice point during the reference trial. At a given choice point, if the subject reproduces the same path as during the reference trial, it is considered as a “correct turn” and we allocate a mark of 100. If the subject moves away from the T11 pathway, a mark of 0 is allocated. The average of the marks for all choice points yields the repeated path score. With such scoring, a repeated path score of 100 means that the subject has performed the same path on the temporal test as on T11. Contrary to the percentage of direct paths that reflects the capacity to optimally (in terms of directness of path) use allocentric or sequential egocentric navigation strategies, the repeated path score reflects the use of the sequential egocentric strategy based on temporal order memory, be it optimal or not.

To minimize the impact on the repeated path score of random navigation that characterizes lost subjects, the repeated path score was computed on the portion of the performed path comprised between the starting point and the first extremity of a peripheral alley visited.

To control for an accidental error in one of the temporal tests, we considered the mean repeated path score obtained on both sequential and route tracing tests as a better index to assess sequence memory deficit, than each of these scores taken separately.

“What” test.

Subjects were asked to name the visual cues they had seen in the environment and to specify their number (Fig. 1A3).

This test was evaluated by the percentage of correctly and freely recalled visual cues (maximum of 8, 1 point for each object up to 8 points). Each groove of trees, each individual village and each mountain range were considered as a single object (Fig. 1B).

“Where” test: spatial memory.

Subjects then had to place the visual cues that they had recalled on the table-top drawing of the Starmaze relatively to the goal (Fig. 1A4). The goal, placed in regards to the departure point that had been defined during the route tracing task, was shown to the subject.

The “where” score was equal to the number of correctly placed cues, averaged out by the total number of visual cues (8). It evaluated the capacity to encode an allocentric map (Moffat and Resnick, 2002).

Statistics

Patient groups (AD, aMCI, FTLD) were compared with the age-matched group of healthy adults (60–80). A p < 0.05 level of significance was chosen. ANOVA tests were conducted to compare performances among groups. After a significant main effect, Scheffe post hoc tests were performed. To control for computer experience, an ANCOVA analysis was performed.

Receiver operating characteristic

A Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis was performed to evaluate the discriminating power of each neuropsychological test taken individually. Optimal cutoff points were calculated by selecting the point on the ROC curve that maximized both sensitivity and specificity.

Discriminant analysis

To investigate whether the navigation task provided additional discriminant information to standard neuropsychological tests, a discriminant analysis was performed (Wilk's method) on standard neuropsychological tests and performance parameters of the Starmaze task (STATISTICA for Windows 5.1, Statsoft, Inc) for the 3 groups: AD, 60–80, and FTLD. We first entered all parameters in a preliminary discriminant analysis: model 1 with neuropsychological tests only (12 parameters), and model 2 with neuropsychological tests and Starmaze parameters (18 parameters) to determine the most discriminant parameters. Because the number of variables entered in a model impacts on its discriminating power, we then ran a second definitive discriminant analysis including the 6 most discriminant parameters of the preliminary discriminant analysis to have the same number of parameters in both models.

Wilk's lambda index (where a partial Wilk's lambda score of 0 referred to perfect discrimination) and Youden index (Y = Sensitivity + Specificity − 1) were used to measure each model's discriminating power. To better understand which groups of subjects were best discriminated by one variable, we performed a discriminant analysis on pairs of groups, rather than on all three patients groups.

Factor analysis

To infer to which cognitive function the experimental tests were sensitive, a factor analysis was performed on the 10 neuropsychological tests and the 6 variables from the Starmaze task. Because performances of temporal tests had ceiling effects in young adults, only the three groups 60–80, AD, and FTLD were considered. Factor analysis was based on principal component analysis with varimax rotation. Eigenvalue above one was the criterion that determined the number of factors extracted.

Results

Subjects

Neuropsychological characteristics of the groups are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Neuropsychological characteristics of the participant groups

| Healthy subjects |

Patients |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20–39 (N = 20) | 40–59 (N = 19) | 60–80 (N = 24) | aMCI (N = 14) | AD (N = 16) | FTLD (N = 11) | |

| Age (years) | 28.2 (5.7) | 48.3 (6.8)* | 72 (4.2)* | 70.8 (8.8) | 70.0 (9.0) | 68.2 (7.8) |

| Sex (M/F) | 9/11 | 10/9 | 11/13 | 10/4 | 8/8 | 6/5 |

| Education (years) | 13.4 (1.7) | 12.3 (1.9) | 12.6 (1.9) | 12.9 (3.8) | 13.1 (2.2) | 13.5 (2.2) |

| Computer experience | 2.1 (0.8) | 1.8 (0.8) | 0.8 (0.7)* | 1.0 (0.8) | 0.7 (0.8) | 0.4 (0.5) |

| MMSEb | ||||||

| Orientation | 9.7 (0.5) | 9.8 (0.4) | 9.7 (0.4) | 8.7 (1.4) | 7.4 (2.1) | 8.6 (1.1) |

| Recall | 2.8 (0.4) | 2.5 (0.6) | 2.5 (0.6) | 2.0 (1.0) | 0.9 (1.0) | 2.3 (0.9)† |

| Total (24/30) | ||||||

| General cognitive function | 28.8 (1.2) | 27.9 (1.4) | 28.3 (1.2) | 25.9 (3.4) | 22.8 (3.5) | 24.9 (2.5) |

| CBT | ||||||

| Forwards span | ||||||

| Attention/working memory | 9.4 (1.7) | 8.6 (2.0) | 7.2 (1.3)* | 5.8 (1.6) | 4.7 (1.8) | 4.9 (1.1) |

| Backwards span | 8.9 (1.8) | 8.2 (1.7) | 6.7 (1.2)* | 4.4 (1.3) | 3.4 (1.2) | 3 (1.3) |

| FCSRTc | ||||||

| Free recall (17/48) | ||||||

| Verbal memory | 36.2 (4.1) | 33.4 (4.3) | 30.8 (5.0)* | 11.6 (4.7) | 9.2 (7.0)a | 17.7 (11.1)a |

| Total recall (40/48) | 46.6 (1.2) | 46.7 (1.1) | 46.1 (1.7) | 27.5 (8.8) | 23 (10.5)a | 37.5 (6.8)a† |

| Cue sensitivity (71%) | 93.9 (9.3) | 92.0 (7.0) | 89.6 (9.2) | 45.4 (8.8) | 38.1 (8.9)a | 67.2 (15.4)a† |

| RCFT | ||||||

| Copy (/36) | ||||||

| Visual memory | 35.3 (1.0) | 34.3 (1.7) | 33.6 (1.7)* | 31.7 (4.4) | 25.9 (9.4) | 27.5 (5.6) |

| Memory (/36) | ||||||

| Visuoconstructive function | 26 (3.7) | 21.8 (5.3)* | 18.3 (5)* | 7.1 (3.4)a | 3.9 (3.7)a | 15.5 (6.1)a† |

| FAB (12/16)d | ||||||

| Executive function | 18.0 (0.0) | 17.8 (0.4) | 17.1 (0.8)* | 14.9 (2.3)† | 13.3 (2.2) | 11.5 (1.4) |

Shown are mean values (standard deviation). Higher test scores indicate better performances.

*Scheffe post hoc test, p < 0.05, 40–59 or 60–80 groups compared with 20–39 age group.

†Scheffe post hoc test, p<0.05, patient group compared with AD group.

aScores on the RCFT memory test are missing for 3 aMCI, 4 AD, and 6 FTLD patients and scores on the FCSRT are missing for 1 AD and 1 FTLD patient.

b–dCutoff scores for certain tests (MMSE, FCSRT, FAB) are indicated in parentheses and their explanations are detailed here, below:

bMMSE: Dementia (above cutoff score) versus healthy adult (below cutoff score) (Lezak, 1983).

cFCSRT memory subtests: Prodromal AD (i.e, some aMCI patients, below cutoff scores) versus normal aging (above cutoff scores) (Sarazin et al., 2007).

dFAB: AD (above cutoff score) versus frontotemporal dementia (below cutoff score) (Dubois et al., 2000; Slachevsky et al., 2004).

Healthy adults were divided into three age groups: 20–39, 40–59, and 60–80 years old. There were significant age effects for computer experience (F(2,60) = 19.9, p < 10−3), with younger subjects having more computer experience. Patient groups and healthy controls (60–80) did not differ in terms of education level (F(3.61) = 0.32, p = 0.8), computer experience (F(3.61) = 1.30, p = 0.27), or age (F(3.61) = 0.31, p = 0.81). MMSE was significantly lower in AD and FTLD groups, but not in the aMCI group, compared with the 60–80 group (F(3,61) = 13.3, p = 10−6) (Table 1).

The learning phase

Exploration activity did not differ among patient groups and the 60–80 control group (F(3,61) = 0.35, p = 0.78, Fig. 2C).

All groups of healthy adults and of patient groups showed a learning effect, determined by a linear regression over the 3 blocks of learning trials for each group individually for both performance parameters: the percentage of successful trials (B coefficient > 3,11, p < 0.05) and the percentage of direct trials (B >7.08, p < 0.01) (Fig. 2A,B). One exception was the AD group, where there was no significant learning effect for the percentage of direct trials (F(1,46) = 2.06, p = 0.15), despite a significant effect for the percentage of successful trials (F(1,46) = 6.7, p = 0.01). In addition, considering the percentage of direct trials, there were significant effects of both age (F(2,60) = 13.1, p = 10−5) and diagnosis (F(3,61) = 2.8, p = 0.03).

Test phase: assessing specific navigation strategies

Temporal memory tests

Sequential navigation.

All healthy subject groups approached optimal performance for the sequential navigation task (Fig. 3A, left). Ten percent (N = 2) of the 40–59 group and 8% (N = 2) of the 60–80 group did not fully succeed this trial.

Figure 3.

Temporally organized memory differentiates AD from normal aging and FTLD better than spatially organized memory. A, Performance on temporal memory tests. The repeated path score measured the percentage of the sequence of turns performed on learning trial 11 that were reproduced during the temporal memory tests. Left, Sequential navigation test. Middle, Route tracing on a survey map of the maze; Right, Temporal memory score (mean value of both temporal tests). B, The “what” test. Percentage of environmental cues freely recalled. C, Spatial memory test (“where”), as defined by the percentage of cues that are correctly placed on the environment layout. Gray dots represent individual scores. Their diameter is proportional to the number of subjects. Individual performances of two subjects from the 60–80 group whose memory performances declined over 18 months are shown (green crosses), as well as AD converters (red crosses) and nonconverters (black triangles). *p < 0.05, Scheffe post hoc test.

For patients, there was a significant effect of diagnosis (F(3,61) = 13.3, p < 10−4) where aMCI and AD patients were each significantly impaired relative to controls (Scheffe's test: p < 0.02 for all) and AD patients were impaired relative to FTLD group (Scheffe's test: p = 0.005). These results remained significant after controlling for computer experience (F(3,60) = 16.2, p < 10−4), mean repeated path score during the learning phase (F(3,60) = 7.8, p = 10−4) and percentage of direct paths during the learning phase (F(3,60) = 21.5, p < 10−7).

Route tracing.

There was no significant age effect in route tracing performance (p > 0.2), as opposed to a significant patient group effect (F(3,61) = 12.8, p = 10−4). Scheffe post hoc tests of the main effect revealed that AD patients were impaired relative to the control and FTLD groups (Scheffe's test: p < 0.002 for all) and aMCI patients were significantly impaired relative to healthy controls (p = 2.10−4) and nonsignificantly to FTLD (Fig. 3A, middle). The repeated path scores for the route tracing task and sequential navigation task correlated significantly (r = 0.61, p<10−5). These results on patient groups remained significant after controlling for computer experience (F(3,60) = 16.7, p < 10−4), mean repeated path score during the learning phase (F(3,60) = 9.4, p < 10−4) and percentage of direct paths during the learning phase (F(3,60) = 27.1, p < 10−7).

During normal aging, there was a clear trend for impairment of temporal memory, evaluated overall by the mean value of performances of the sequential navigation and route tracing subtests, without however reaching statistical significance (F(2,60) = 3.1, p = 0.051). AD patients and, importantly, aMCI patients, were impaired compared with FTLD and normal controls (F(3,61) = 26.2, p < 10−6, Scheffe's test p < 0.001 for both, Fig. 3A, right).

Diagnostic value of mean performances.

The majority of aMCI and AD patients performed unsuccessfully on both temporal tests (50% and 75%, respectively). Conversely, neither healthy subjects nor FTLD patients failed both temporal tests, but rather, a majority performed successfully on both tests (at least 64% of double successes for each group) while a minority performed single errors on the temporal test (25% single errors in the 60–80 group, 36% in the FTLD group).

For AD detection among FTLD and age-matched healthy adults, a cutoff score of 66.5/100 for the temporal memory score (i.e., mean of the two temporal memory tests' performances) yielded maximum sensitivity (87.5%) and specificity (91.4%) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Receiver operating characteristic analysis: neuropsychological tests and performance parameters of the Starmaze task (in bold) associated with AD dementia and performed on groups of healthy old subjects (60–80), and FTLD and AD patients

| Test | AUC | SE | p | Cutoff | Se | Sp | Youden index |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Computer experience | 0.48 | 0.08 | 0.59 | — | — | — | — |

| What | 0.50 | 0.08 | 0.48 | — | — | — | — |

| Exploration | 0.53 | 0.08 | 0.34 | — | — | — | — |

| Education | 0.54 | 0.08 | 0.31 | — | — | — | — |

| % Successful trials | 0.59 | 0.08 | 0.14 | — | — | — | — |

| % Direct trials | 0.69 | 0.08 | 0.01 | 100.0 | 50.1 | 91.4 | 0.41 |

| RCFT copy | 0.71 | 0.08 | 0.004 | 34.0 | 81.0 | 42.9 | 0.24 |

| FAB | 0.71 | 0.08 | 0.005 | 17.0 | 93.8 | 57.1 | 0.51 |

| CBT –F | 0.75 | 0.07 | 10−4 | 7.0 | 97.5 | 48.6 | 0.46 |

| MMSE-O | 0.79 | 0.07 | 10−5 | 10.0 | 81.3 | 60.1 | 0.41 |

| CBT -B | 0.79 | 0.0.07 | 10−5 | 6.0 | 93.8 | 62.9 | 0.57 |

| Spatial memory | 0.82 | 0.06 | <10−5 | 25.4 | 81.3 | 68.6 | 0.49 |

| MMSE -T | 0.84 | 0.06 | <10−5 | 28.0 | 93.8 | 60 | 0.54 |

| MMSE -R | 0.87 | 0.06 | <10−5 | 2.5 | 93.8 | 57.1 | 0.51 |

| Route tracing | 0.87 | 0.06 | <10−5 | 66.7 | 81.3 | 91.2 | 0.72 |

| Sequential navigation | 0.89 | 0.05 | <10−5 | 100.0 | 87.5 | 82.9 | 0.70 |

| FCSRT - CS | 0.89 | 0.05 | <10−5 | 57.1 | 81.3 | 88.6 | 0.70 |

| FCSRT - FR | 0.91 | 0.05 | <10−5 | 23.0 | 93.8 | 74.3 | 0.68 |

| FCSRT - TR | 0.93 | 0.04 | <10−5 | 35.0 | 87.5 | 85.7 | 0.73 |

| Temporal memory | 0.94 | 0.04 | <10−5 | 66.5 | 87.5 | 91.4 | 0.79 |

Optimal cutoff was determined for each test, when possible. Results are presented in order of statistical power.

For aMCI detection among healthy aged adults, a cutoff score of 60.5% yielded a maximum sensitivity of 61% and a specificity of 100%. Seven aMCI patients (50% of the aMCI group) were followed over 12–18 months. Among these, 5 (71%) converted to AD while the 2 others were cognitively stable. These 5 converters all had scores below the cutoff of 60.5% (see color plots, Fig. 3A, right).

“What” memory test

There was a significant effect of age group for the free recall of cues (“what”) (F(2,60) = 12.3, p = 6.10−4), with the 60–80 group recalling less visual cues than both younger groups (Scheffe's test: p < 0.001 for both). No patient group was impaired relative to the age-matched control group for the free recall of objects, with a mean number of freely recalled cues of 3.1 ± 0.41 of 8 cues recalled (Fig. 3B).

Spatial memory test: “where”

There was no effect of age for the positioning of cues (“where”) (Fig. 3C). There was a significant effect of diagnosis (F(3,61) = 5.2, p < 10−7). Scheffe post hoc tests of the main effect revealed that AD patients were significantly impaired relative to controls and FTLD patients (p < 0.03 for both). AD patients placed correctly 11 ± 5% of the cues, compared with 32 ± 3% for controls, 26 ± 7% for aMCI patients, and 32 ± 6% for FTLD patients (Fig. 3C).

Relative discriminating power of the navigation tasks

First, a ROC analysis was performed to compare the discriminating power of neuropsychological tests with that of Starmaze subtests (Table 2). The highest Youden index (Y) of all the tests was found for the temporal memory tests (Y = 0.79) followed by the verbal memory subtests (free, total recall and sensitivity to cueing on the FCSRT) (0.68 < Y < 0.74). The average temporal test was more discriminating than each of the temporal tests, without however reaching statistical significance. An explanation for this may be found by examining the frequency of failures on the temporal test in the different groups. In the aMCI and AD groups, failure on both temporal tests was more frequent than failure on only one temporal test (aMCI patients: 50% vs 28.5%; AD patients: 75% vs 18.7%, respectively). This suggests that assessing temporal memory twice is more discriminating than only once, as it reduces the impact of single errors that may be accidental.

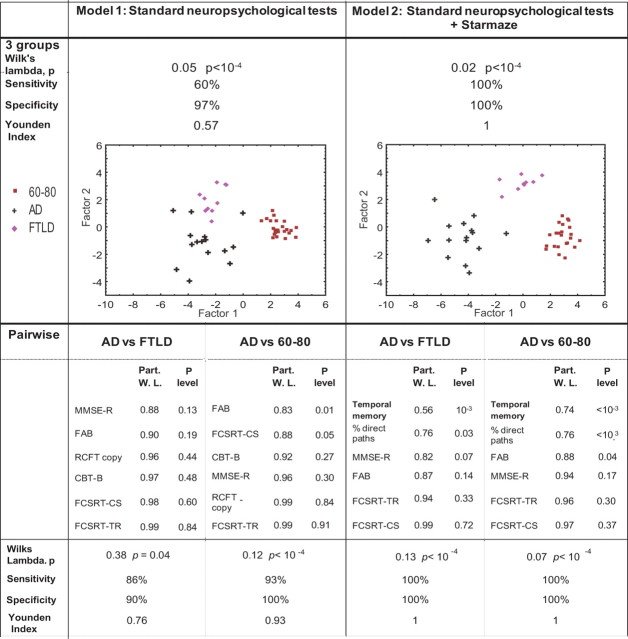

To examine whether the Starmaze tests added any discrimination value for the differential diagnosis of early AD to that of standard neuropsychological tests used in clinic, a discriminant analysis (DA) was performed on AD, FTLD, and 60–80 groups.

Two models with the same number of variables were compared: model 1 with neuropsychological tests and without Starmaze parameters, and model 2 with neuropsychological tests and with Starmaze parameters.

To determine the variables to enter in each case, a preliminary DA was performed on the three groups (AD, FTLD, 60–80) including all variables. In model 1 of the preliminary DA, all neuropsychological and demographic variables were included; in model 2 of the preliminary DA, the latter variables supplied with 6 Starmaze performance variables were included (Table 3). The 6 performance variables from the Starmaze task were: (1) percentage of successful trials on learning trial 11; (2) percentage of direct paths on learning trial 11; (3) exploration activity; (4) the “what” score; (5) the spatial memory score, and (6) temporal memory score. The rationale for including the performances on trial 11, the last learning trial, was to compare the discriminating power of two different strategies performed at an equivalent time during the experience; on the one hand an undetermined strategy (as measured by trial 11), and on the other hand, a strategy based on sequence or spatial memory.

Table 3.

Classifiers' performance of all neuropsychological tests without (left) or with (right) all Starmaze subtests in a preliminary discriminant analysis conducted on the 60–80, AD, and FTLD groups, used to select the six variables for the definitive discriminant analysis

| Model 1: Standard neuropsychological tests |

Model 2: Navigation + Standard neuropsychological tests |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Partial Wilks lambda | p level | Partial Wilks lambda | p level | |||

| FAB | 0.57 | <10−4 | Temporal memory | 0.56 | 10−3 | |

| MMSE -R | 0.81 | 0.03 | FAB | 0.67 | 10−2 | |

| FCSRT- CS | 0.86 | 0.07 | % Direct trials | 0.77 | 0.03 | |

| CBT -B | 0.90 | 0.16 | MMSE -R | 0.85 | 0.12 | |

| RCFT copy | 0.92 | 0.22 | FCSRT- CS | 0.88 | 0.18 | |

| FCSRT- TR | 0.94 | 0.34 | FCSRT- TR | 0.89 | 0.22 | |

| MMSE -T | 0.95 | 0.44 | CBT -F | 0.91 | 0.29 | |

| FCSRT- FR | 0.97 | 0.55 | “What” | 0.92 | 0.33 | |

| MMSE-O | 0.98 | 0.64 | Spatial memory | 0.93 | 0.42 | |

| CBT –F | 0.98 | 0.65 | MMSE-O | 0.95 | 0.55 | |

| Education | 0.98 | 0.65 | CBT -B | 0.97 | 0.73 | |

| Computer experience | 0.98 | 0.76 | Computer experience | 0.97 | 0.68 | |

| RCFT copy | 0.98 | 0.85 | ||||

| MMSE-T | 0.98 | 0.8 | ||||

| FCSRT- FR | 0.98 | 0.69 | ||||

| % Successful trials | 0.99 | 0.88 | ||||

| Education | 0.99 | 0.89 | ||||

| Exploration | 0.99 | 0.89 | ||||

| Wilks lambda | 0.043, p < 10−4 | 0.014, p < 10−4 | ||||

| Sensitivity | 80% | 100% | ||||

| Specificity | 97% | 100% | ||||

| Youden index | 0.77 | 1 | ||||

Model 1: Neuropsychological measures (MMSE-O, MMSE-R, MMSE-T, CBT–F, CBT–B, FCSRT-FR, FCSRT-TR, FCSRT-CS, RCFT copy, FAB) and demographic variables (Education level, Computer experience). Model 2 additionally contains the 6 parameters from the Starmaze task: “what” score, spatial memory score, temporal memory score, percentage of successful trials on learning trial 11, percentage of direct paths on learning trial 11, and exploration activity. Top, Significant variables extracted, with their statistical significance. Bottom, Classifier performance for both models.

The six most discriminating variables of each model 1 and 2 of the preliminary DA were entered into the definitive DA conducted on the three groups (Fig. 4). In model 1, sensitivity and specificity values reached 60% and 97%, respectively (Youden index = 0.57). In model 2, which included temporal memory and percentage of direct paths on learning trial 11 as Starmaze performance parameters, overall discrimination was higher than in model 1, yielding 100% correct classification with 100% sensitivity and 100% specificity (Y = 1). This shows that the inclusion in the DA of the temporal memory component with the percentage of direct paths associated with other standard neuropsychological tests allowed to fully discriminate 60–80, FTLD and AD groups (see color plots in Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Comparison of the discriminating power of two models deprived (model 1) or not (model 2) of Starmaze tests equated for the number of variables. In both models, the 6 most discriminating variables from the preliminary discriminant analysis conducted on all variables were entered in the definitive discriminant analysis [Model 1: (1) FAB, (2) MMSE-R, (3) FCSRT-CS, (4) CBT-B, (5) RCFT copy, (6) FCSRT-TR; Model 2: (1) temporal memory score, (2) FAB, (3) percentage of direct paths on learning trial 11, (4) MMSE-R, (5) FCSRT-CS, (6) FCSRT-TR). Top, Classifier performances for both models performed on the 60–80, AD and FTLD groups. Graphs represent individual classifications along both factors extracted from the discriminant analysis. The more the groups are separated, the more the model discriminates. Bottom, Discriminant analysis on pairs of groups. In each pairwise model of models 1 and 2, significant variables are extracted and, below, classifier performances are shown. FR, Free recall; TR, total recall; CS, sensitivity to cueing (%); W. L., partial Wilks lambda.

Finally, in a DA on model 2 conducted on pairs of groups, temporal memory score was the most significant variable for AD discrimination against both normal aging and FTLD, followed by the percentage of direct paths (Fig. 4, bottom).

Cognitive functions assessed by the navigation tasks

To infer the cognitive functions the experimental tests were sensitive to, a factor analysis with all neuropsychological and experimental tests was performed (Table 4). This identified 4 factors with eigenvalues >1, that explained 72% of total variance. The first factor explained 47% of variance and included verbal memory (FCSRT) subtests (factor loading > 0.84), the temporal memory score (factor loading = 0.73) and the spatial memory test (factor loading = 0.54). This factor essentially constitutes a simple index of memory. The other factors explained <10% variance each, essentially corresponding to general cognitive/visuoconstructive functions, encoding of the environment, and executive function.

Table 4.

Factor analysis after varimax rotation on all variables

| First factor | Second factor | Third factor | Fourth factor | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First factor: Memory | ||||

| FCSRT- FR | 0.84 | 0.13 | −0.01 | 0.33 |

| FCSRT- TR | 0.93 | 0.11 | −0.06 | 0.21 |

| FCSRT- CS | 0.93 | 0.10 | −0.06 | 0.22 |

| Temporal memory | 0.73 | 0.40 | 0.18 | 0.09 |

| Spatial memory | 0.54 | 0.40 | −0.32 | 0.05 |

| Second factor: General cognitive and visuoconstructive functions | ||||

| % Successful trials | 0.15 | 0.81 | −0.07 | 0.10 |

| RCFT copy | 0.16 | 0.61 | 0.00 | 0.59 |

| MMSE-O | 0.55 | 0.57 | 0.03 | 0.19 |

| MMSE-R | 0.38 | 0.59 | 0.04 | 0.26 |

| MMSE | 0.54 | 0.50 | −0.07 | 0.50 |

| % Direct trials | 0.22 | 0.54 | 0.44 | −0.14 |

| Exploration | 0.15 | −0.46 | 0.23 | −0.42 |

| Third factor: Encoding of the environment | ||||

| “What” | 0.09 | 0.04 | −0.90 | −0.10 |

| Fourth factor: Executive function | ||||

| FAB | 0.35 | 0.04 | 0.08 | 0.82 |

| CBT-F | 0.46 | 0.25 | 0.13 | 0.61 |

| CBT-B | 0.59 | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.70 |

| % of variance | 47% | 10% | 8% | 7% |

Discussion

We hypothesized that testing spatiotemporal memory in a nonverbal and active navigation task would be appropriate to assess hippocampal function and therefore to discriminate AD or aMCI from FTLD and healthy aging. We used the Starmaze navigation task developed for mice (Burguière et al., 2005; Rondi-Reig et al., 2006) and adapted to humans (Iglói et al., 2009, 2010) to create a spatiotemporal memory, later tested for temporal (“when”) and spatial (“where”) components.

We tested patient groups compared with healthy age-matched control and also younger control groups to define the pathology-specific changes, independently of aging in a spatiotemporal memory task. This task can be solved using allocentric or sequential egocentric navigation strategies which both depend on the hippocampus (Iglói et al., 2010) and are acquired in parallel (Iglói et al., 2009) in healthy young subjects.

We show that the temporal test provides the most reliable tool to differentiate AD from aMCI, FTLD, and normal aging, and that this temporal memory test, along with the percentage of direct paths, increases the discriminating power of other neuropsychological tests to 100%.

There were no significant age- or patient-group differences in the motor aspects of the task assessed by the analysis of their exploration activity on the first trial (Fig. 2C). Furthermore, AD-specific impairments for temporal memory tests do not reflect a difference in computer experience, since entering the latter as a control variable in the analyses did not change any of the results.

Importantly, all groups of subjects showed a learning effect during the navigation task (Fig. 2A,B). Nevertheless, performance of the AD group was lower than the 60–80 and FTLD groups as their percentage of direct paths to the goal was markedly impaired in the last block of the learning phase (Fig. 2B). The form of learning impairment presented here is consistent with other studies' results showing intact topographical perception in AD (Bird et al., 2010) and partially preserved route learning capacities in virtual reality in early AD (Cushman et al., 2008).

Spatial memory impairments in aging and AD pathology

Impairments of spatial memory (“where,” Fig. 3C) in both aged (60–80) versus younger (20–39) subjects, on the one hand, and in AD patients compared with FTLD patients and age-matched healthy controls, on the other, are consistent with previous findings of spatial processing and of navigation related to aging (Moffat and Resnick, 2002; Driscoll and Sutherland, 2005) and to AD pathology (Hort et al., 2007; Bird and Burgess, 2008). Of note, the AD-impairment in the “where” test cannot be explained by object memory impairment, since the AD group was not impaired for the “what” test (Fig. 3B). In agreement with the latter studies, the spatial memory score did not have a sufficient predictive value to discriminate AD from 60 to 80 and FTLD groups (Fig. 3C; Table 2, ROC analysis: sensitivity: 81.3%, specificity: 68.6%).

Temporal memory impairment in AD

Studies assessing spatial memory in aging and pathology have mostly focused on allocentric spatial processing (Moffat and Resnick, 2002; Cushman et al., 2008; Antonova et al., 2009). Here, we additionally focused on the temporal aspect of navigation (Eichenbaum, 2004; Fouquet et al., 2010).

AD and even aMCI patients were impaired in both the sequential navigation task and in the route tracing task. Assessing temporal memory twice allowed differentiating accidental errors from memory errors. These specific impairments of AD and aMCI groups on temporal memory tests are consistent with their deficit for reporting the encountering order of objects along a route (deIpolyi et al., 2007) and in the sequential ordering of places in AD (Kalová et al., 2005). These observations may be explained by the fact that temporal sequence memory, which requires correct encoding where distinct time points are bound together to form a temporal order memory (Fouquet et al., 2010), has been associated with hippocampal function in both rodents (DeCoteau and Kesner, 2000) and humans (Kumaran and Maguire, 2006; Van Opstal et al., 2008; Iglói et al., 2010).

It is important to note that the temporal tests in the Starmaze task is more than a simple temporal order test (e.g., assessing order of words or scenes). The temporal order memory used during the temporal tests and learning of this navigation task can be defined as the capacity to distinguish between two spatial locations visited at different points in time. In this sense, it differs from a simple test of temporal order by including two components, a spatial and a temporal one. The spatial component in this case does not refer to an allocentric representation of space but rather to the ability to maintain a representation of the order in which location (i.e., intersection in our experiment) have been experienced over time (Howland et al., 2008). This particular temporal order memory is strongly dependent on the integrity of both the hippocampus (Chiba et al., 1994; Gilbert et al., 2001; Kesner et al., 2002) and the prefrontal cortex (Chiba et al., 1994; Fuster, 2001; Hannesson et al., 2004) two regions particularly sensitive to damage in AD patients. The temporal test in the Starmaze task therefore requires recall of a spatiotemporal context that involves the encoding of distances and directions along the path. The complexity of this spatiotemporal memory tests might be the key for better detection of Alzheimer's disease than simply temporal memory test.

On the contrary, FTLD patients performed normally on these tasks (Fig. 3A). It has been shown that temporal memory in FTLD is impaired only when important temporal monitoring is required (e.g., active search of items that have not been previously visited) but not for the simple reproduction of sequences (Owen et al., 1990). Results from this study are consistent with our results, since the temporal memory tests require few active monitoring and few executive function, the latter being impaired in FTLD (Neary et al., 1998). Indeed, the temporal tests contain no interfering cues (all alleys and intersections are identical) and no choice of strategy.

As such, testing for temporal sequence memory in a navigation task appears to specifically target memory deficit in AD. Also, the results of the factor analysis validated that the temporal memory test, as well as the spatial memory test, essentially assessed memory, as it is the case for the traditional test used to assess episodic memory (FCSRT).

Can the temporal test be considered as a test of episodic memory? All patients had performed the tested sequence at least 3 times before the last learning trial, so the temporal test does not assess the recall of a unique episode and therefore does not verify the classical definition of episodic memory as the ability to “remember the ‘what’,-‘where’-and-‘when’ components of a unique episode” (Tulving, 2002; Dere et al., 2005). However, the temporal test assesses for the ‘what’,-‘where’-and-‘when’ components of a personal experience. Also, it depends on hippocampal function as hippocampal activation during the recall of repeated events and their context has been shown in the Starmaze task (Iglói et al., 2010). Overall, this suggests that the temporal test shares crucial properties with episodic memory which could explain its sensitivity and specificity to AD diagnosis.

Diagnostic value of temporal memory tests

Temporal memory, as measured by the temporal memory scores, was impaired in AD. Moreover, this temporal memory deficit was highly sensitive (87.5%) and specific (91.4%) to early AD when compared with FTLD patients and healthy aged adults. Indeed, the highest Youden index (Y) of all the tests was found for the temporal memory score (Y = 0.79), and the next most sensitive and specific test was found for verbal recall (FCSRT-TR; Y = 0.73) (Table 2). The temporal memory test added major contribution to the discrimination of AD among healthy aged and FTLD, as revealed by its low partial Wilk's lambda value in the discriminant analysis, Fig. 4). This indicates that the temporal memory score was nonredundant with the other memory tests, that is, it targeted components that were not captured in other neuropsychological tests.

These additional components may arise from the fact that the temporal tests model hippocampal function better than the latter. Indeed, to the contrary to the temporal tests, FCSRT and delayed recall RCFT can be resolved without reference to a spatiotemporal context, which precisely is hippocampus dependent (for review, see Burgess et al., 2002). Also, assessment of memory with the FCSRT task that consists in the recall of verbal lists (Grober and Buschke, 1987) may be biased by the verbal aspects of this task; differential familiarity with certain words as well as the rote rehearsal of the list of words (Longoni et al., 1993), which both depend on extrahippocampal functions (Schweickert and Boruff, 1986).

The temporal memory task also differentiated significantly the aMCI group from the control group. Temporal sequence memory impairments in MCI have been reported for sequential ordering of places (Kalová et al., 2005; Weniger et al., 2011). Also, we were able to follow 7 aMCI patients over 3 years. Five of them converted later to AD, while 2 remained stable. The 5 converters had temporal memory scores below the optimal cutoff for aMCI detection among healthy aged adults (60.5%) (Fig. 3A, red crosses). Overall, although the sample size was very small, these results suggest that the temporal memory test might help to differentiate future AD converters at the MCI stage from healthy controls.

Finally, to evaluate the capacity of this test to depict very prodromal AD, we also controlled for memory degradation in healthy adults. Two adults from the 60–80 group showed isolated and significant episodic memory impairments 18 months later, without, however, reaching the criteria for aMCI. Both of these potential converters had the lowest scores in their group (Fig. 3A, green crosses). These observations suggest that temporal memory deficit might be tested as a preliminary detector of very early AD in humans, as it has been shown in rodents (Ohno et al., 2006).

To conclude, the results show that a temporal memory test of an experimentally controlled spatiotemporal memory discriminates AD and aMCI subjects from age-matched control subjects and FTLD patients, with high sensitivity (87.5%) and specificity (91.4%). Compared with the spatial memory test, the temporal memory score is more specific to AD pathology and includes no age-related deficit. Furthermore, this test had higher predictive power than other standard neuropsychological memory tests, and, associated with the latter, selectively raised the power of a discriminant analysis to 100% showing that it added nonredundant discriminant information to standard neuropsychological tests.

Footnotes

This work was supported by Fondation Recherche Médicale (programme Longévité Cognitive et neurosensorielle-DLC20060206428) grants, Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR Young Researcher 07-JCJC-0108-01), and Université Pierre et Marie Curie (BQR 2007). This is a CNRS–AP-HP collaboration. We thank Frederic Jarlier for his help on computer programming and Bénédicte Babayan for careful reading of the manuscript. We also thank the “Institute of Memory and Alzheimer's Disease” staff for their neuropsychological and neurologic reports.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Antonova E, Parslow D, Brammer M, Dawson GR, Jackson SH, Morris RG. Age-related neural activity during allocentric spatial memory. Memory. 2009;17:125–143. doi: 10.1080/09658210802077348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg L. Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) Psychopharmacol Bull. 1988;24:637–639. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird CM, Burgess N. The hippocampus and memory: insights from spatial processing. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9:182–194. doi: 10.1038/nrn2335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird CM, Chan D, Hartley T, Pijnenburg YA, Rossor MN, Burgess N. Topographical short-term memory differentiates Alzheimer's disease from frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Hippocampus. 2010;20:1154–1169. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braak H, Braak E. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol. 1991;82:239–259. doi: 10.1007/BF00308809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess N, Maguire EA, O'Keefe J. The human hippocampus and spatial and episodic memory. Neuron. 2002;35:625–641. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00830-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burguière E, Arleo A, Hojjati M, Elgersma Y, De Zeeuw CI, Berthoz A, Rondi-Reig L. Spatial navigation impairment in mice lacking cerebellar LTD: a motor adaptation deficit? Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:1292–1294. doi: 10.1038/nn1532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen P, Ratcliff G, Belle SH, Cauley JA, DeKosky ST, Ganguli M. Cognitive tests that best discriminate between presymptomatic AD and those who remain nondemented. Neurology. 2000;55:1847–1853. doi: 10.1212/wnl.55.12.1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherrier MM, Mendez M, Perryman K. Route learning performance in Alzheimer disease patients. Neuropsychiatry Neuropsychol Behav Neurol. 2001;14:159–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiba AA, Kesner RP, Reynolds AM. Memory for spatial location as a function of temporal lag in rats: role of hippocampus and medial prefrontal cortex. Behav Neural Biol. 1994;61:123–131. doi: 10.1016/s0163-1047(05)80065-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chupin M, Gérardin E, Cuingnet R, Boutet C, Lemieux L, Lehéricy S, Benali H, Garnero L, Colliot O. Fully automatic hippocampus segmentation and classification in Alzheimer's disease and mild cognitive impairment applied on data from ADNI. Hippocampus. 2009;19:579–587. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corsi P. Human memory and the medial temporal region of the brain. Abstracts Int. 1972;34:891B. [Google Scholar]

- Cushman LA, Stein K, Duffy CJ. Detecting navigational deficits in cognitive aging and Alzheimer disease using virtual reality. Neurology. 2008;71:888–895. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000326262.67613.fe. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeCoteau WE, Kesner RP. A double dissociation between the rat hippocampus and medial caudoputamen in processing two forms of knowledge. Behav Neurosci. 2000;114:1096–1108. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.114.6.1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- deIpolyi AR, Rankin KP, Mucke L, Miller BL, Gorno-Tempini ML. Spatial cognition and the human navigation network in AD and MCI. Neurology. 2007;69:986–997. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000271376.19515.c6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dere E, Huston JP, De Souza Silva MA. Episodic-like memory in mice: simultaneous assessment of object, place and temporal order memory. Brain Res Brain Res Protoc. 2005;16:10–19. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresprot.2005.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driscoll I, Sutherland RJ. The aging hippocampus: navigating between rat and human experiments. Rev Neurosci. 2005;16:87–121. doi: 10.1515/revneuro.2005.16.2.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drzezga A, Grimmer T, Henriksen G, Stangier I, Perneczky R, Diehl-Schmid J, Mathis CA, Klunk WE, Price J, DeKosky S, Wester HJ, Schwaiger M, Kurz A. Imaging of amyloid plaques and cerebral glucose metabolism in semantic dementia and Alzheimer's disease. Neuroimage. 2008;39:619–633. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois B, Albert ML. Amnestic MCI or prodromal Alzheimer's disease? Lancet Neurol. 2004;3:246–248. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(04)00710-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois B, Slachevsky A, Litvan I, Pillon B. The FAB: a Frontal Assessment Battery at bedside. Neurology. 2000;55:1621–1626. doi: 10.1212/wnl.55.11.1621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois B, Feldman HH, Jacova C, Dekosky ST, Barberger-Gateau P, Cummings J, Delacourte A, Galasko D, Gauthier S, Jicha G, Meguro K, O'brien J, Pasquier F, Robert P, Rossor M, Salloway S, Stern Y, Visser PJ, Scheltens P. Research criteria for the diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease: revising the NINCDS-ADRDA criteria. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6:734–746. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70178-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois B, Feldman HH, Jacova C, Cummings JL, Dekosky ST, Barberger-Gateau P, Delacourte A, Frisoni G, Fox NC, Galasko D, Gauthier S, Hampel H, Jicha GA, Meguro K, O'Brien J, Pasquier F, Robert P, Rossor M, Salloway S, Sarazin M, et al. Revising the definition of Alzheimer's disease: a new lexicon. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9:1118–1127. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70223-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichenbaum H. Hippocampus: cognitive processes and neural representations that underlie declarative memory. Neuron. 2004;44:109–120. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elfgren C, Brun A, Gustason L, Johanson A, Minthon L, Passnt U, Risberg J. Neuropsychological tests as discriminators between dementia of Alzheimer type and frontotemporal dementia. Int J Geriatric Psychiatry. 1994;9:635–642. [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fouquet C, Tobin C, Rondi-Reig L. A new approach for modeling episodic memory from rodents to humans: the temporal order memory. Behav Brain Res. 2010;215:172–179. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2010.05.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuster JM. The prefrontal cortex—an update: time is of the essence. Neuron. 2001;30:319–333. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00285-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert PE, Kesner RP, Lee I. Dissociating hippocampal subregions: double dissociation between dentate gyrus and CA1. Hippocampus. 2001;11:626–636. doi: 10.1002/hipo.1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grober E, Buschke H. Genuine memory deficits in dementia. Dev Neuropsychol. 1987;3:13–36. [Google Scholar]

- Hannesson DK, Vacca G, Howland JG, Phillips AG. Medial prefrontal cortex is involved in spatial temporal order memory but not spatial recognition memory in tests relying on spontaneous exploration in rats. Behav Brain Res. 2004;153:273–285. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2003.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hort J, Laczó J, Vyhnálek M, Bojar M, Bures J, Vlcek K. Spatial navigation deficit in amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:4042–4047. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611314104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howland JG, Harrison RA, Hannesson DK, Phillips AG. Ventral hippocampal involvement in temporal order, but not recognition, memory for spatial information. Hippocampus. 2008;18:251–257. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iglói K, Zaoui M, Berthoz A, Rondi-Reig L. Sequential egocentric strategy is acquired as early as allocentric strategy: Parallel acquisition of these two navigation strategies. Hippocampus. 2009;19:1199–1211. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iglói K, Doeller CF, Berthoz A, Rondi-Reig L, Burgess N. Lateralized human hippocampal activity predicts navigation based on sequence or place memory. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:14466–14471. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004243107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jobst KA, Smith AD, Szatmari M, Molyneux A, Esiri ME, King E, Smith A, Jaskowski A, McDonald B, Wald N. Detection in life of confirmed Alzheimer's disease using a simple measurement of medial temporal lobe atrophy by computed tomography. Lancet. 1992;340:1179–1183. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)92890-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalová E, Vlcek K, Jarolímová E, Bures J. Allothetic orientation and sequential ordering of places is impaired in early stages of Alzheimer's disease: corresponding results in real space tests and computer tests. Behav Brain Res. 2005;159:175–186. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2004.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kesner RP, Gilbert PE, Barua LA. The role of the hippocampus in memory for the temporal order of a sequence of odors. Behav Neurosci. 2002;116:286–290. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.116.2.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessels RP, Feijen J, Postma A. Implicit and explicit memory for spatial information in Alzheimer's disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2005;20:184–191. doi: 10.1159/000087233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessels RP, van den Berg E, Ruis C, Brands AM. The backward span of the Corsi Block-Tapping Task and its association with the WAIS-III Digit Span. Assessment. 2008;15:426–434. doi: 10.1177/1073191108315611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kremin H, Perrier D, De Wilde M. DENO-100—Paradigme expérimental et test clinique de dénomination contrôlée: effet relatif de 7 variables expérimentales sur les performances de 16 sujets atteints de maladies dégénératives. Rev Neuropsychol. 1999:439–440. [Google Scholar]

- Kumaran D, Maguire EA. The dynamics of hippocampal activation during encoding of overlapping sequences. Neuron. 2006;49:617–629. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lezak MD. Neuropsychological assessment. Ed 2. New York: Oxford UP; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Longoni AM, Richardson JT, Aiello A. Articulatory rehearsal and phonological storage in working memory. Mem Cognit. 1993;21:11–22. doi: 10.3758/bf03211160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguire EA, Burgess N, Donnett JG, Frackowiak RS, Frith CD, O'Keefe J. Knowing where and getting there: a human navigation network. Science. 1998;280:921–924. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5365.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKhann GM, Albert MS, Grossman M, Miller B, Dickson D, Trojanowski JQ. Clinical and pathological diagnosis of frontotemporal dementia: report of the Work Group on Frontotemporal Dementia and Pick's Disease. Arch Neurol. 2001;58:1803–1809. doi: 10.1001/archneur.58.11.1803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer's Disease. Neurology. 1984;34:939–944. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffat SD, Resnick SM. Effects of age on virtual environment place navigation and allocentric cognitive mapping. Behav Neurosci. 2002;116:851–859. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.116.5.851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffat SD, Zonderman AB, Resnick SM. Age differences in spatial memory in a virtual environment navigation task. Neurobiol Aging. 2001;22:787–796. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(01)00251-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JC. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology. 1993;43:2412–2414. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.11.2412-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neary D, Snowden JS, Gustafson L, Passant U, Stuss D, Black S, Freedman M, Kertesz A, Robert PH, Albert M, Boone K, Miller BL, Cummings J, Benson DF. Frontotemporal lobar degeneration: a consensus on clinical diagnostic criteria. Neurology. 1998;51:1546–1554. doi: 10.1212/wnl.51.6.1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohno M, Chang L, Tseng W, Oakley H, Citron M, Klein WL, Vassar R, Disterhoft JF. Temporal memory deficits in Alzheimer's mouse models: rescue by genetic deletion of BACE1. Eur J Neurosci. 2006;23:251–260. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04551.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen AM, Downes JJ, Sahakian BJ, Polkey CE, Robbins TW. Planning and spatial working memory following frontal lobe lesions in man. Neuropsychologia. 1990;28:1021–1034. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(90)90137-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pai MC, Jacobs WJ. Topographical disorientation in community-residing patients with Alzheimer's disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2004;19:250–255. doi: 10.1002/gps.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabinovici GD, Furst AJ, O'Neil JP, Racine CA, Mormino EC, Baker SL, Chetty S, Patel P, Pagliaro TA, Klunk WE, Mathis CA, Rosen HJ, Miller BL, Jagust WJ. 11C-PIB PET imaging in Alzheimer disease and frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Neurology. 2007;68:1205–1212. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000259035.98480.ed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rey A. Psychological examination of traumatic encephalopathy. Clin Neuropsychologist. 1993;7:3–21. [Google Scholar]

- Rondi-Reig L, Petit GH, Tobin C, Tonegawa S, Mariani J, Berthoz A. Impaired sequential egocentric and allocentric memories in forebrain-specific-NMDA receptor knock-out mice during a new task dissociating strategies of navigation. J Neurosci. 2006;26:4071–4081. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3408-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarazin M, Berr C, De Rotrou J, Fabrigoule C, Pasquier F, Legrain S, Michel B, Puel M, Volteau M, Touchon J, Verny M, Dubois B. Amnestic syndrome of the medial temporal type identifies prodromal AD: a longitudinal study. Neurology. 2007;69:1859–1867. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000279336.36610.f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scahill RI, Schott JM, Stevens JM, Rossor MN, Fox NC. Mapping the evolution of regional atrophy in Alzheimer's disease: unbiased analysis of fluid-registered serial MRI. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:4703–4707. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052587399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweickert R, Boruff B. Short-term memory capacity: magic number or magic spell? J Exp Psychol Learn Mem Cogn. 1986;12:419–425. doi: 10.1037//0278-7393.12.3.419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seab JP, Jagust WJ, Wong ST, Roos MS, Reed BR, Budinger TF. Quantitative NMR measurements of hippocampal atrophy in Alzheimer's disease. Magn Reson Med. 1988;8:200–208. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910080210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons JS, Verfaellie M, Galton CJ, Miller BL, Hodges JR, Graham KS. Recollection-based memory in frontotemporal dementia: implications for theories of long-term memory. Brain. 2002;125:2523–2536. doi: 10.1093/brain/awf247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slachevsky A, Villalpando JM, Sarazin M, Hahn-Barma V, Pillon B, Dubois B. Frontal assessment battery and differential diagnosis of frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2004;61:1104–1107. doi: 10.1001/archneur.61.7.1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JC, Stopford CL, Snowden JS, Neary D. Qualitative neuropsychological performance characteristics in frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer's disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76:920–927. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2003.033779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson PM, Hayashi KM, de Zubicaray G, Janke AL, Rose SE, Semple J, Herman D, Hong MS, Dittmer SS, Doddrell DM, Toga AW. Dynamics of gray matter loss in Alzheimer's disease. J Neurosci. 2003;23:994–1005. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-03-00994.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tierney MC, Yao C, Kiss A, McDowell I. Neuropsychological tests accurately predict incident Alzheimer disease after 5 and 10 years. Neurology. 2005;64:1853–1859. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000163773.21794.0B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trivedi MA, Wichmann AK, Torgerson BM, Ward MA, Schmitz TW, Ries ML, Koscik RL, Asthana S, Johnson SC. Structural MRI discriminates individuals with Mild Cognitive Impairment from age-matched controls: a combined neuropsychological and voxel based morphometry study. Alzheimers Dement. 2006;2:296–302. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2006.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tulving E. Episodic memory: from mind to brain. Annu Rev Psychol. 2002;53:1–25. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Hoesen GW, Hyman BT, Damasio AR. Entorhinal cortex pathology in Alzheimer's disease. Hippocampus. 1991;1:1–8. doi: 10.1002/hipo.450010102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Opstal F, Verguts T, Orban GA, Fias W. A hippocampal-parietal network for learning an ordered sequence. Neuroimage. 2008;40:333–341. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weniger G, Ruhleder M, Lange C, Wolf S, Irle E. Egocentric and allocentric memory as assessed by virtual reality in individuals with amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Neuropsychologia. 2011;49:518–527. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2010.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]