Significance Statement

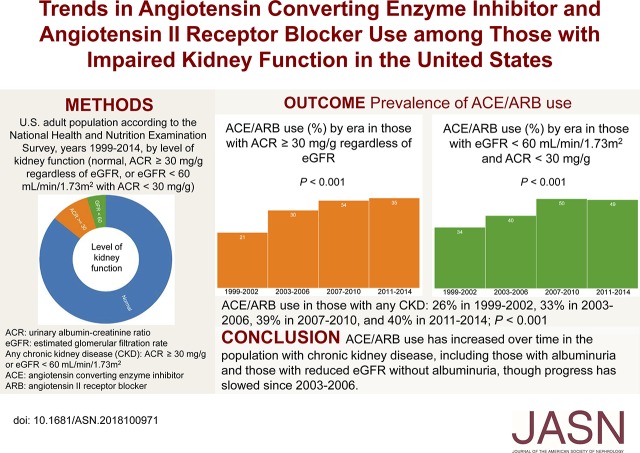

Although angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor and angiotensin II receptor blocker (ARB) medications are mainstays of treatment in CKD, the frequency of ACE/ARB use has not been well characterized in this population. Nationally representative data from 1999 to 2014 showed that overall ACE/ARB use during this period was only 34.9% among those with CKD; use rose significantly with time (from 25.5% in 1999–2002 to 40.1% in 2011–2014) but seemed to level off after the early 2000s, a trend similarly observed in multiple CKD subgroups. Overall, regardless of era, ACE/ARB use in CKD was the exception unless concomitant illnesses, like diabetes mellitus or cardiac disease, were present. This suggests that a significant opportunity exists for improvement in the care in community-based CKD.

Keywords: ACE inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor blocker, chronic kidney disease, hypertension, disparities, temporal trends

Visual Abstract

Abstract

Background

Although hypertension is common in CKD and evidence-based treatment of hypertension has changed considerably, contemporary and nationally representative information about use of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACEs) inhibitors or angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) in CKD is lacking.

Methods

We examined ACE/ARB trends from 1999 to 2014 among 38,885 adult National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey participants with creatinine-based eGFR<60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 or urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio ≥30 mg/g.

Results

Of 7085 participants with CKD, 34.9% used an ACE/ARB. Across four eras studied, rates of use rose significantly (rates were 25.5% in 1999–2002, 33.3% in 2003–2006, 39.0% in 2007–2010, and 40.1% in 2011–2014) but appeared to plateau after 2003. Among those with CKD, use was significantly greater among non-Hispanic white and black individuals (36.1% and 38.2%, respectively) and lower among Hispanic individuals (26.7%) and other races/ethnicities (29.3%). In age-, sex-, and race/ethnicity-adjusted models, ACE/ARB use was significantly associated with era (adjusted odds ratios [aOR], 1.41; 95% confidence interval [95% CI], 1.14 to 1.74 for 2003–2006, 1.84; 95% CI, 1.48 to 2.28 for 2007–2010, and 2.02; 95% CI, 1.61 to 2.53 for 2011–2014 versus 1999–2002); it also was significantly associated with non-Hispanic black versus non-Hispanic white race/ethnicity (aOR, 1.40; 95% CI, 1.19 to 1.66). Other multivariate associations included older age, men, elevated BMI, diabetes mellitus, treated hypertension, cardiac failure, myocardial infarction, health insurance, and receiving medical care within the prior year.

Conclusions

Rates of ACE/ARB use increased in the early 2000s among United States adults with CKD, but for unclear reasons, use appeared to plateau in the ensuing decade. Research examining barriers to care and other factors is needed.

Hypertension, which is highly prevalent in patients with CKD, is associated with cardiovascular outcomes in both the general1,2 and CKD populations.3 Several recent changes in the therapeutic management of hypertension are relevant in patients with CKD. For example, the Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial (SPRINT) demonstrated that lower BP targets reduced cardiovascular events, primarily driven by reduced risk of cardiac failure, an effect unmodified by the presence of CKD.4 More recently, the American Heart Association (AHA) recommended that the threshold to define hypertension should be lowered from 140/90 to 130/80 mm Hg and that individuals with CKD should initiate antihypertensive medication at this level regardless of proteinuria.5 The AHA guidelines differ from the recommended Eighth Report of the Joint National Committee (JNC-8) and most recent Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) guidelines, which both predate the SPRINT. Thus, the JNC-8 maintains a uniform threshold of 140/90 mm Hg, regardless of proteinuria,6 whereas KDIGO recommends a threshold of 130/80 mm Hg to be treated with angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor or angiotensin II receptor blocker (ARB) when albuminuria is present or 140/90 mm Hg when it is not.7

ACE/ARB therapy is a cornerstone of hypertension and proteinuria management in CKD. ACE/ARB medications have been shown to have apparently salutary effects on markers of kidney function and cardiovascular events in populations with diabetes mellitus and kidney disease8,9; similar findings have been observed in patients with CKD without diabetes.10–16 ACE/ARB medications also are first-line therapy in patients with cardiac failure with reduced ejection fraction, a population with a very high prevalence of CKD.17–19 They are also recommended in select patients with myocardial infarction.20,21

Given the change in the therapeutic landscape of hypertension and the public health burden of CKD, it seems reasonable to suggest that trends in ACE/ARB use in the United States CKD population should be followed closely. In the United States, ACE/ARB use increased in the general adult population from 1999 to 2012.22 ACE/ARB use from 2001 to 2010 increased among those with hypertension,23 whereas from 1988 to 2002, ACE use alone increased in those with hypertension and CKD.24 In the absence of information about contemporary practice patterns in the CKD population, we set out to assess ACE/ARB use in the United States population between 1999 and 2014.

Methods

Study Population

The National Health and Nutrition Health Examination Survey (NHANES) is a series of nationally representative cross-sectional surveys conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics among noninstitutionalized adults and children in the United States sampled in a stratified, clustered probability design.25 Surveys are performed continuously and have been documented in 2-year increments since 1999. The survey includes a questionnaire, physical examination, and laboratory data. Our study was limited to those ages ≥20 years old with serum creatinine and urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio (ACR) measurements surveyed between 1999 and 2014.

Measures of Kidney Function

Kidney function was defined by both creatinine-based eGFR and urinary ACR. The Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration equation was used to calculated eGFR.26 Calibration of creatinine was performed according to the recommended calibration equations for particular survey years requiring it before the use of an isotope dilution mass spectrometry-traceable reference method.27–29 Participants were considered to have impaired kidney function if they had eGFR<60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 or ACR≥30 mg/g.30,31 Sensitivity analysis using a threshold of ACR≥100 mg/g did not produce meaningfully different results.

Medication Use, Comorbidities, and Other Characteristics

Prescription medications used within the 30 days before the NHANES assessment were documented during in-home interviews, including by inspection of prescription medication bottles. All medications solely or in combination with other medications containing ACE/ARB according to their coded ingredient category were assessed to determine if the participant was using an ACE/ARB.

Age, sex, race/ethnicity, education (known to have graduated high school versus not), health insurance status (known to be uninsured versus not), income status (known to be at or below poverty level25 versus not), and medical care over the prior year were all assessed by questionnaire. Because of changes in the questionnaire regarding medical care in the prior year, participants were categorized as being known to not have had care in the prior year or not. Diabetes mellitus was defined as present with either hemoglobin A1c ≥6.5%32 or self-reported history of the disease. Reflecting the fact that all study participants were evaluated before the SPRINT findings were known,4 hypertension was defined as present either when the mean of up to three resting BP measurements was ≥140/90 mm Hg or by self-report and further characterized by use of any self-described antihypertensive medication. Cardiac failure and myocardial infarction were defined by self-report.

Statistical Analyses

In this 16-year study, participant statistical weights were determined by dividing the NHANES 2-year Mobile Examination Center statistical weight (“wtmec2yr”) by eight as recommended by the National Center for Health Statistics.33,34 For our primary analysis, the chi-squared test was used to evaluate the null hypothesis of no change over time in the proportion of individuals with eGFR<60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 or ACR≥30 mg/g using ACE/ARB medications. Logistic regression was used to calculate odds ratios for ACE/ARB use adjusting for age, sex, and race/ethnicity. R version 3.4.4 was used for statistical analyses (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Characteristics of the general United States study population (n=38,885) are shown in Table 1. For age distribution, 38.1% (SEM=0.5%) were 20–39 years of age, 45.2% (0.4%) were 40–64 years of age, and 16.7% (0.3%) were 65 years of age or older (Table 1); 51.9% (0.2%) were women, 70.0% (1.1%) were of non-Hispanic white race/ethnicity, 10.7% (0.6%) were of non-Hispanic black ethnicity, 13.3% (0.9%) were of Hispanic ethnicity, and 6.0% (0.3%) were of other ethnicities (Table 1). Additionally, 14.1% (0.3%) of the study population had eGFR<60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 or ACR≥30 mg/g (Table 1). Overall, 15.1% (0.3%) of the study population used an ACE/ARB (Table 1).

Table 1.

Prevalence of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin II receptor blocker use in the general United States adult population by era, level of kidney function, demographic characteristics, and comorbidities (the National Health and Nutrition Health Examination Survey 1999–2014)

| Characteristic | Percentage with Characteristic (SEM) | Percentage Using ACE/ARB (SEM) | P Valuea | Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI)b | P Valueb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | 15.1 (0.3) | ||||

| NHANES era | <0.001 | ||||

| 1999–2002 | 23.0 (0.7) | 9.9 (0.5) | 1 [Reference] | ||

| 2003–2006 | 24.5 (1.0) | 14.1 (0.6) | 1.43 (1.24 to 1.66) | <0.001 | |

| 2007–2010 | 25.6 (0.9) | 17.2 (0.7) | 1.86 (1.62 to 2.13) | <0.001 | |

| 2011–2014 | 26.9 (0.9) | 18.3 (0.8) | 1.98 (1.71 to 2.30) | <0.001 | |

| eGFR, ml/min per 1.73 m2 and ACR, mg/gc | <0.001 | ||||

| eGFR≥60 and ACR<30 (no CKD) | 85.9 (0.3) | 11.8 (0.3) | 1 [Reference] | ||

| eGFR≥60 and ACR≥30 | 7.4 (0.2) | 25.1 (1.0) | 1.91 (1.69 to 2.16) | <0.001 | |

| eGFR=30–59 and ACR<30 | 4.5 (0.2) | 44.2 (1.4) | 2.23 (1.95 to 2.54) | <0.001 | |

| eGFR=30–59 and ACR≥30 | 1.6 (0.1) | 49.6 (2.5) | 2.73 (2.20 to 3.40) | <0.001 | |

| eGFR<30 and ACR<30 | 0.2 (0) | 54.7 (4.9) | 3.09 (2.03 to 4.71) | <0.001 | |

| eGFR<30 and ACR≥30 | 0.4 (0) | 45.3 (3.9) | 2.54 (1.83 to 3.52) | <0.001 | |

| Age, yr | <0.001 | ||||

| 20–39 | 38.1 (0.5) | 2.0 (0.1) | 1 [Reference] | ||

| 40–64 | 45.2 (0.4) | 17.3 (0.4) | 10.1 (8.69 to 11.7) | <0.001 | |

| ≥65 | 16.7 (0.3) | 38.7 (0.8) | 30.6 (26.4 to 35.5) | <0.001 | |

| Sex | 0.21 | ||||

| Men | 48.1 (0.2) | 15.3 (0.4) | 1 [Reference] | ||

| Women | 51.9 (0.2) | 14.8 (0.4) | 0.89 (0.83 to 0.95) | <0.001 | |

| Race/ethnicity | <0.001 | ||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 70.0 (1.1) | 16.2 (0.4) | 1 [Reference] | ||

| Non-Hispanic black | 10.7 (0.6) | 17.1 (0.5) | 1.45 (1.33 to 1.58) | <0.001 | |

| Hispanic | 13.3 (0.9) | 8.9 (0.5) | 0.79 (0.69 to 0.91) | 0.001 | |

| Other | 6.0 (0.3) | 11.8 (0.9) | 0.92 (0.77 to 1.09) | 0.33 | |

| Health insurance status | <0.001 | ||||

| Insured | 84.2 (0.3) | 17.6 (0.4) | 1 [Reference] | ||

| Uninsured | 15.8 (0.3) | 1.4 (0.2) | 0.09 (0.07 to 0.12) | <0.001 | |

| Received medical care in last year | <0.001 | ||||

| Yes | 84.3 (0.3) | 17.6 (0.4) | 1 [Reference] | ||

| No | 15.7 (0.3) | 1.3 (0.2) | 0.09 (0.07 to 0.12) | <0.001 | |

| Income status | <0.001 | ||||

| Above poverty level | 86.5 (0.4) | 15.5 (0.4) | 1 [Reference] | ||

| Below or equal to poverty level | 13.5 (0.4) | 11.9 (0.5) | 1.01 (0.92 to 1.10) | 0.90 | |

| High school graduation | <0.001 | ||||

| No | 18.5 (0.5) | 17.4 (0.6) | 1 [Reference] | ||

| Yes | 81.5 (0.5) | 14.5 (0.3) | 0.95 (0.86 to 1.04) | 0.25 | |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | <0.001 | ||||

| <30 | 66.2 (0.4) | 10.9 (0.3) | 1 [Reference] | ||

| ≥30 | 33.8 (0.4) | 22.9 (0.5) | 2.60 (2.41 to 2.80) | <0.001 | |

| Diabetes mellitusd | <0.001 | ||||

| No: SR−, A1c<6.5% | 90.0 (0.2) | 11.4 (0.3) | 1 [Reference] | ||

| Yes: SR−, A1c≥6.5% | 2.0 (0.1) | 28.0 (1.8) | 1.95 (1.61 to 2.37) | <0.001 | |

| Yes: SR+, A1c<6.5% | 2.9 (0.1) | 51.5 (1.9) | 5.21 (4.42 to 6.13) | <0.001 | |

| Yes: SR+, A1c≥6.5% | 5.2 (0.2) | 54.0 (1.3) | 6.04 (5.35 to 6.82) | <0.001 | |

| Hypertensione | <0.001 | ||||

| No: SR−, BP<140/90 | 64.5 (0.5) | 1.8 (0.1) | 1 [Reference] | ||

| Yes: SR−, BP≥140/90 | 6.1 (0.2) | 3.7 (0.4) | 1.29 (0.98 to 1.68) | 0.07 | |

| Yes: SR+, BP<140/90, no BP medication | 4.1 (0.2) | 2.6 (0.5) | 1.45 (0.94 to 2.22) | 0.09 | |

| Yes: SR+, BP≥140/90, no BP medication | 1.2 (0.1) | 3.8 (1.1) | 1.58 (0.87 to 2.85) | 0.14 | |

| Yes: SR+, BP<140/90, ≥1 BP medication | 16.0 (0.4) | 58.6 (0.9) | 51.0 (43.5 to 59.7) | <0.001 | |

| Yes: SR+, BP≥140/90, ≥1 BP medication | 8.1 (0.2) | 51.3 (1.1) | 33.5 (28.2 to 39.8) | <0.001 | |

| Cardiac failure | <0.001 | ||||

| No | 97.7 (0.1) | 14.2 (0.3) | 1 [Reference] | ||

| Yes | 2.3 (0.1) | 52.7 (1.8) | 3.13 (2.67 to 3.67) | <0.001 | |

| Prior myocardial infarction | <0.001 | ||||

| No | 96.7 (0.1) | 13.9 (0.3) | 1 [Reference] | ||

| Yes | 3.3 (0.1) | 48.4 (1.7) | 2.69 (2.30 to 3.15) | <0.001 |

ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; ARB, angiotensin II receptor blocker; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; NHANES, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey; ACR, albumin-to-creatinine ratio; SR−, no by self-report; SR+, yes by self-report.

Chi-squared test.

Logistic regression adjusted for age, sex, and race/ethnicity.

eGFR is by the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration equation. Normal kidney function is eGFR≥60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 and ACR<30 mg/g.

Diabetes mellitus status is defined by self-reported history and hemoglobin A1c.

Hypertension status is defined by self-reported history and resting BP (in millimeters of mercury); it is further characterized by use of any self-described antihypertensive medication (BP medication) among those who are SR+.

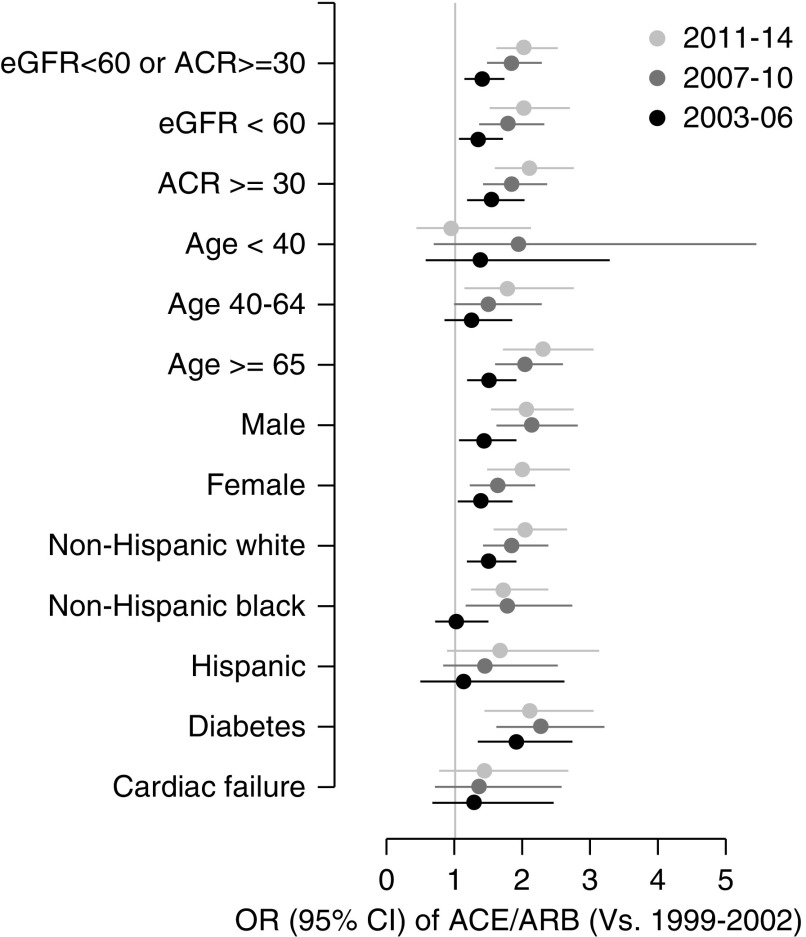

Characteristics of participants with eGFR<60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 or ACR≥30 mg/g (n=7085) are shown in Table 2. Overall, 34.9% (0.8%) of this subgroup used an ACE/ARB medication (Table 2); corresponding values for eGFR<60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (regardless of ACR) and ACR≥30 mg/g (regardless of eGFR) were 45.8% (1.2%) and 30.2% (0.9%), respectively (data not tabulated). ACE/ARB use in the subgroup with eGFR<60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 or ACR≥30 mg/g increased over time from 25.5% (1.7%) in 1999–2002 to 33.3% (1.3%) in 2003–2006, 39.0% (1.5%) in 2007–2010, and 40.1% (1.6%) in 2011–2014 (P<0.001) (Table 2). In models adjusted for age, sex, and race/ethnicity, odds ratios for ACE/ARB use were 1.41 (95% confidence interval [95% CI], 1.14 to 1.74 [versus 1999–2002]; P=0.002) for 2002–2006, 1.84 (95% CI, 1.48 to 2.28; P<0.001) for 2007–2010, and 2.02 (95% CI, 1.61 to 2.53; P<0.001) for 2011–2014 (Table 2). Regarding era, similar patterns were present within subgroups defined by eGFR<60 ml/min per 1.73 m2, ACR≥30 mg/g, age, sex, race/ethnicity, and the presence of diabetes mellitus or cardiac failure (Figure 1 and Supplemental Figure 1). Other adjusted associations of ACE/ARB use in the population with impaired kidney function included older age, men, non-Hispanic black race/ethnicity, body mass index ≥30 kg/m2, awareness of diabetes, awareness and treatment of self-reported hypertension, prior myocardial infarction, cardiac failure, being uninsured, and having had no medical care in the prior year (Table 2).

Table 2.

Prevalence of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin II receptor blocker use in the United States adult population with impaired kidney function by era, demographic characteristics, and comorbidities (the National Health and Nutrition Health Examination Survey 1999–2014)

| Characteristic | Percentage with Characteristic (SEM)a | Percentage Using ACE/ARB (SEM) | P Valueb | Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI)c | P Valuec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | 34.9 (0.8) | ||||

| NHANES era | <0.001 | ||||

| 1999–2002 | 22.0 (1.0) | 25.5 (1.7) | 1 [Reference] | ||

| 2003–2006 | 25.1 (1.3) | 33.3 (1.3) | 1.41 (1.14 to 1.74) | 0.002 | |

| 2007–2010 | 24.4 (1.0) | 39.0 (1.5) | 1.84 (1.48 to 2.28) | <0.001 | |

| 2011–2014 | 28.5 (1.2) | 40.1 (1.6) | 2.02 (1.61 to 2.53) | <0.001 | |

| Age, yr | <0.001 | ||||

| 20–39 | 15.9 (0.7) | 7.0 (1.2) | 1 [Reference] | ||

| 40–64 | 35.0 (0.7) | 31.7 (1.4) | 6.06 (4.11 to 8.93) | <0.001 | |

| ≥65 | 49.1 (0.9) | 46.3 (1.1) | 11.7 (8.03 to 16.9) | <0.001 | |

| Sex | <0.001 | ||||

| Men | 42.5 (0.8) | 37.8 (1.1) | 1 [Reference] | ||

| Women | 57.5 (0.8) | 32.7 (1.0) | 0.81 (0.72 to 0.92) | 0.001 | |

| Race/ethnicity | <0.001 | ||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 70.9 (1.3) | 36.1 (1.0) | 1 [Reference] | ||

| Non-Hispanic black | 11.9 (0.8) | 38.2 (1.6) | 1.40 (1.19 to 1.66) | <0.001 | |

| Hispanic | 11.5 (1.0) | 26.7 (1.8) | 1.01 (0.81 to 1.26) | 0.93 | |

| Other | 5.7 (0.5) | 29.3 (3.6) | 0.97 (0.69 to 1.37) | 0.88 | |

| Health insurance status | <0.001 | ||||

| Insured | 91.4 (0.4) | 37.8 (0.8) | 1 [Reference] | ||

| Uninsured | 8.6 (0.4) | 3.8 (0.8) | 0.09 (0.05 to 0.13) | <0.001 | |

| Received medical care in last year | <0.001 | ||||

| Yes | 91.5 (0.5) | 37.8 (0.8) | 1 [Reference] | ||

| No | 8.5 (0.5) | 3.3 (0.8) | 0.08 (0.05 to 0.12) | <0.001 | |

| Income status | <0.001 | ||||

| Above poverty level | 84.3 (0.7) | 36.0 (0.9) | 1 [Reference] | ||

| Below or equal to poverty level | 15.7 (0.7) | 28.8 (1.4) | 0.94 (0.81 to 1.09) | 0.43 | |

| High school graduation | 0.10 | ||||

| No | 26.8 (0.8) | 36.9 (1.4) | 1 [Reference] | ||

| Yes | 73.2 (0.8) | 34.2 (0.9) | 1.02 (0.88 to 1.20) | 0.78 | |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | <0.001 | ||||

| <30 | 58.7 (0.9) | 29.4 (1.0) | 1 [Reference] | ||

| ≥30 | 41.3 (0.9) | 42.6 (1.4) | 2.06 (1.76 to 2.43) | <0.001 | |

| Diabetes mellitusd | <0.001 | ||||

| No: SR−, A1c<6.5% | 72.5 (0.8) | 27.3 (0.8) | 1 [Reference] | ||

| Yes: SR−, A1c≥6.5% | 4.2 (0.3) | 32.7 (3.1) | 1.26 (0.96 to 1.65) | 0.10 | |

| Yes: SR+, A1c<6.5% | 7.2 (0.4) | 62.3 (2.4) | 3.61 (2.84 to 4.58) | <0.001 | |

| Yes: SR+, A1c≥6.5% | 16.1 (0.7) | 57.9 (2.0) | 3.42 (2.79 to 4.18) | <0.001 | |

| Hypertensione | <0.001 | ||||

| No: SR−, BP<140/90 | 33.5 (0.9) | 8.6 (1.0) | 1 [Reference] | ||

| Yes: SR−, BP≥140/90 | 9.4 (0.4) | 9.0 (1.2) | 0.76 (0.52 to 1.10) | 0.15 | |

| Yes: SR+, BP<140/90, no BP medication | 2.3 (0.3) | 13.1 (3.4) | 1.72 (0.94 to 3.14) | 0.08 | |

| Yes: SR+, BP≥140/90, no BP medication | 1.6 (0.2) | 15.6 (5.1) | 1.48 (0.69 to 3.21) | 0.32 | |

| Yes: SR+, BP<140/90, ≥1 BP medication | 29.5 (0.8) | 62.3 (1.5) | 13.2 (9.85 to 17.8) | <0.001 | |

| Yes: SR+, BP≥140/90, ≥1 BP medication | 23.7 (0.6) | 56.0 (1.7) | 9.94 (7.42 to 13.3) | <0.001 | |

| Cardiac failure | <0.001 | ||||

| No | 91.7 (0.4) | 32.9 (0.8) | 1 [Reference] | ||

| Yes | 8.3 (0.4) | 57.3 (2.5) | 1.93 (1.57 to 2.38) | <0.001 | |

| Prior myocardial infarction | <0.001 | ||||

| No | 90.5 (0.4) | 32.8 (0.8) | 1 [Reference] | ||

| Yes | 9.5 (0.4) | 55.2 (2.3) | 1.73 (1.41 to 2.13) | <0.001 |

ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; ARB, angiotensin II receptor blocker; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; NHANES, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey; SR−, no by self-report; SR+, yes by self-report.

Impaired kidney function defined by eGFR<60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 by the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration equation or albumin-to-creatinine ratio ≥30 mg/g.

Chi-squared test.

Logistic regression adjusted for age, sex, and race/ethnicity.

Diabetes mellitus status is defined by self-reported history and hemoglobin A1c.

Hypertension status is defined by self-reported history and resting BP (in millimeters of mercury); it is further characterized by use of any self-described antihypertensive medication (BP medication) among those who are SR+.

Figure 1.

Temporal trends in angiotensin II converting enzyme (ACE) and angiotensin II receptor blocker (ARB) use in CKD-relevant subgroups. Adjusted odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence interval (95% CI) ACE/ARB use in the United States adult population with impaired kidney function (eGFR <60 mL/min per 1.73 m2, by the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration equation, or albumin-to-creatinine ratio [ACR] ≥30 mg/g) by era compared with 1999–2002 in subgroups defined by levels of kidney function, age, sex, race/ethnicity, presence of diabetes mellitus (self-report or hemoglobin A1c ≥6.5%), and presence of cardiac failure. ORs adjusted for age, sex, and race/ethnicity.

No statistically significant change in the distribution of kidney function, defined by both eGFR and ACR, within the United States population comparing 1999–2006 with 2007–2014 was seen (Supplemental Table 1). Further demographic and comorbidity data by NHANES era are shown in Supplemental Table 2.

Discussion

In this study of Unites States adults with CKD, we found that, although use of ACE/ARB increased between 1999 and 2014, it appeared to plateau after 2003, with less than one half of the CKD population using an ACE/ARB. Overall, regardless of era, ACE/ARB use was the exception unless concomitant illnesses, like diabetes mellitus or cardiac disease, were present. It is unclear why this plateau has occurred, and it was similarly observed in multiple CKD subgroups. Among those with reduced eGFR, similar rates of ACE/ARB use were seen regardless of albuminuria. The proportion of participants with preserved eGFR and albuminuria receiving ACE/ARB therapy was particularly low.

The design of this study did not allow us to evaluate the relative contributions of lack of awareness of CKD by individuals and health care systems to its findings. This may include failure to recognize an “abnormal” creatinine measurement if not accompanied by an eGFR. An increased likelihood of identifying CKD may have contributed to increased use of ACE/ARBs whether due to guideline-based assessment of kidney function in diabetes35 and hypertension5 or simply due to access to care. Use of any medication self-described as for treating hypertension was associated with ACE/ARB use. Of note, few participants reported a history of hypertension, and they denied use of any antihypertensive medication; however, a subset of them was using an ACE/ARB. It seems reasonable to suggest that they either used these medications for another indication and/or lacked knowledge about their role in reducing BP.

It seems unrealistic to expect that all individuals with CKD and an appropriate indication would use ACE/ARB medications because of reasons like intolerance of typical effects, such as hypotension, hyperkalemia, eGFR decline, and allergies and anaphylactoid reactions beyond issues of access to care. This being said, the greater use of ACE/ARB in the CKD subgroups with diabetes mellitus or cardiac failure suggests that medication intolerance is an inadequate explanation for nonuse of ACE/ARB medications. Such complications are not assessible in this study design.

Although our analyses focused primarily on associations between era and ACE/ARB use in the CKD population overall, several disparities were present. In models that adjusted for age and sex, the likelihood of ACE/ARB use was greater with non-Hispanic blacks than with non-Hispanic whites. We also found a lower likelihood of ACE/ARB use with women. Concerningly, younger adults with CKD were much less likely to use an ACE/ARB than older adults, with 1 in every 14 individuals age 20–39 years old receiving them compared with 1 in 3 for age 40–64 years old and 1 in 2 for age ≥65 years old. Unsurprisingly, ACE/ARB use was markedly lower in those with CKD who were without health insurance or who did not receive medical care in the preceding year. Yet, even among the large majorities of those with CKD who have health insurance and who received care within the prior year, ACE/ARB use was below one in two. Education and income, as other socioeconomic markers, were not predictive of ACE/ARB use in the CKD population after adjusting for demographic differences.

Our study has similarities to a study in patients with hypertension, including those with CKD, from the late 1980s to early 2000s that also examined ACE use.24 In that study, hypertension was defined as BP≥140/90 mm Hg or use of a self-reported antihypertensive medication, a strategy that should lead to larger estimates for ACE use in the population with hypertension, because all participants using ACE would have hypertension by definition. Participants were considered to have CKD with eGFR<60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 or ACR≥200 mg/g. Among that population, 32% were seen to be on ACE therapy in 1999–2002. Our results differed by including those without evidence of hypertension in the population with impaired kidney function, including those with ACR between 30 and 200 mg/g, including ARB medications, and examining more contemporary populations. Other studies from this era have shown that ACE/ARB use have risen in the general United States population,22 the population with diabetes mellitus,36 and the population with hypertension.23

Strengths of this study are the generalizability to the entire United States noninstitutionalized adult population, calibration of creatinine values, standardized BP measurements, and stringent medication survey methods.

Limitations of this study include the availability of single measurements only of creatinine and albuminuria rather than longitudinal measurements. Although participants with personally atypical “impaired” kidney function may be included and those with personally atypical “normal” kidney function may be excluded, it seems reasonable to suggest that differential misclassification by the NHANES period is unlikely, allowing for relative comparisons across eras. Additionally, ACE/ARB medications often decrease eGFR levels, leading to a situation where the study outcome could partially define the study population; this being said, such an effect would lead to an overestimation of ACE/ARB use among those with impaired kidney function measured cross-sectionally. This effect is countered by the reduction in albuminuria expected from ACE/ARB use, potentially biasing against ACE/ARB use in the population with measured impaired kidney function with unknown overall effect on the estimated ACE/ARB use over time. A prior study in the population with diabetic kidney disease showed decreasing albuminuria and decreasing eGFR over time, although such changes may be due to increasing ACE/ARB and other medication use.37 Although the threshold eGFR and urinary ACR levels used to define impaired kidney function are frequently used in other studies and conform to existing guidelines, they are necessarily arbitrary.30,31 This low threshold for ACR was chosen to reduce risk for misclassification among those with more significant degrees of albuminuria.

It is unclear why ACE/ARB use among those with CKD and among CKD-relevant subgroups has plateaued over the last decade. This study suggests that comprehensive research examining additional barriers to care, identification of CKD, and guideline adherence are needed.

Disclosures

None.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

Supplemental Material

This article contains the following supplemental material online at http://jasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1681/ASN.2018100971/-/DCSupplemental.

Supplemental Figure 1. Temporal trends in angiotensin II converting enzyme (ACE) and angiotensin II receptor blocker (ARB) use in CKD-relevant subgroups. Adjusted odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence interval (95% CI) and P-value (hover over point-estimate) ACE/ARB use in the United States adult population with impaired kidney function (eGFR <60 mL/min per 1.73 m2, by the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration equation, or albumin-to-creatinine ratio [ACR] ≥30 mg/g) by era compared with 1999-2002 in subgroups defined by levels of kidney function, age, sex, race/ethnicity, presence of diabetes mellitus (self-report or hemoglobin A1c ≥6.5%), and presence of cardiac failure. ORs adjusted for age, sex, and race/ethnicity.

Supplemental Table 1. Percentage of levels of kidney function, demographic characteristics, and comorbidities in the general United States adult population in 2007–2014 (versus 1999–2006), NHANES.

Supplemental Table 2. Prevalence of demographic characteristics and comorbidities in the United States adult population with impaired kidney function by era, NHANES 1999–2014.

References

- 1.Lewington S, Clarke R, Qizilbash N, Peto R, Collins R, Prospective Studies C; Prospective Studies Collaboration : Age-specific relevance of usual blood pressure to vascular mortality: A meta-analysis of individual data for one million adults in 61 prospective studies. Lancet 360: 1903–1913, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rapsomaniki E, Timmis A, George J, Pujades-Rodriguez M, Shah AD, Denaxas S, et al.: Blood pressure and incidence of twelve cardiovascular diseases: Lifetime risks, healthy life-years lost, and age-specific associations in 1·25 million people. Lancet 383: 1899–1911, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Muntner P, He J, Astor BC, Folsom AR, Coresh J: Traditional and nontraditional risk factors predict coronary heart disease in chronic kidney disease: Results from the atherosclerosis risk in communities study. J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 529–538, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wright JT Jr., Williamson JD, Whelton PK, Snyder JK, Sink KM, Rocco MV, et al.: SPRINT Research Group : A randomized trial of intensive versus standard blood-pressure control. N Engl J Med 373: 2103–2116, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey DE Jr., Collins KJ, Dennison Himmelfarb C, et al.: 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: Executive summary: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American heart association task force on clinical practice guidelines. Hypertension 71: 1269–1324, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, Cushman WC, Dennison-Himmelfarb C, Handler J, et al.: 2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: Report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). JAMA 311: 507–520, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Blood Pressure Work Group : KDIGO clinical practice guideline for the management of blood pressure in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int Suppl 2: 337–414, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lewis EJ, Hunsicker LG, Bain RP, Rohde RD; The Collaborative Study Group : The effect of angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibition on diabetic nephropathy. N Engl J Med 329: 1456–1462, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation Study Investigators: Effects of ramipril on cardiovascular and microvascular outcomes in people with diabetes mellitus: Results of the HOPE study and MICRO-HOPE substudy. Heart outcomes prevention evaluation study investigators. Lancet 355: 253–259, 2000 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maschio G, Alberti D, Janin G, Locatelli F, Mann JF, Motolese M, et al.: The Angiotensin-Converting-Enzyme Inhibition in Progressive Renal Insufficiency Study Group : Effect of the angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor benazepril on the progression of chronic renal insufficiency. N Engl J Med 334: 939–945, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.The GISEN Group (Gruppo Italiano di Studi Epidemiologici in Nefrologia): Randomised placebo-controlled trial of effect of ramipril on decline in glomerular filtration rate and risk of terminal renal failure in proteinuric, non-diabetic nephropathy. The GISEN Group (Gruppo Italiano di Studi Epidemiologici in Nefrologia). Lancet 349: 1857–1863, 1997 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wright JT Jr., Bakris G, Greene T, Agodoa LY, Appel LJ, Charleston J, et al.: African American Study of Kidney Disease and Hypertension Study Group : Effect of blood pressure lowering and antihypertensive drug class on progression of hypertensive kidney disease: Results from the AASK trial. JAMA 288: 2421–2431, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brenner BM, Cooper ME, de Zeeuw D, Keane WF, Mitch WE, Parving HH, et al.: RENAAL Study Investigators : Effects of losartan on renal and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med 345: 861–869, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lewis EJ, Hunsicker LG, Clarke WR, Berl T, Pohl MA, Lewis JB, et al.: Collaborative Study Group : Renoprotective effect of the angiotensin-receptor antagonist irbesartan in patients with nephropathy due to type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 345: 851–860, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Agodoa LY, Appel L, Bakris GL, Beck G, Bourgoignie J, Briggs JP, et al.: African American Study of Kidney Disease and Hypertension (AASK) Study Group : Effect of ramipril vs amlodipine on renal outcomes in hypertensive nephrosclerosis: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 285: 2719–2728, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ruggenenti P, Perna A, Gherardi G, Garini G, Zoccali C, Salvadori M, et al.: Renoprotective properties of ACE-inhibition in non-diabetic nephropathies with non-nephrotic proteinuria. Lancet 354: 359–364, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.CONSENSUS Trial Study Group : Effects of enalapril on mortality in severe congestive heart failure. Results of the Cooperative North Scandinavian Enalapril Survival Study (CONSENSUS). N Engl J Med 316: 1429–1435, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yusuf S, Pitt B, Davis CE, Hood WB, Cohn JN; SOLVD Investigators : Effect of enalapril on survival in patients with reduced left ventricular ejection fractions and congestive heart failure. N Engl J Med 325: 293–302, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pfeffer MA, McMurray JJ, Velazquez EJ, Rouleau JL, Køber L, Maggioni AP, et al.: Valsartan in Acute Myocardial Infarction Trial Investigators : Valsartan, captopril, or both in myocardial infarction complicated by heart failure, left ventricular dysfunction, or both. N Engl J Med 349: 1893–1906, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O’Gara PT, Kushner FG, Ascheim DD, Casey DE Jr., Chung MK, de Lemos JA, et al.: American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines : 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction: A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines. Circulation 127: e362–e425, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Amsterdam EA, Wenger NK, Brindis RG, Casey DE Jr., Ganiats TG, Holmes DR Jr., et al.: ACC/AHA Task Force Members; Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons : 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes: Executive summary: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American heart association task force on practice guidelines. Circulation 130: 2354–2394, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kantor ED, Rehm CD, Haas JS, Chan AT, Giovannucci EL: Trends in prescription drug use among adults in the United States from 1999-2012. JAMA 314: 1818–1831, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gu Q, Burt VL, Dillon CF, Yoon S: Trends in antihypertensive medication use and blood pressure control among United States adults with hypertension: The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2001 to 2010. Circulation 126: 2105–2114, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gu Q, Paulose-Ram R, Dillon C, Burt V: Antihypertensive medication use among US adults with hypertension. Circulation 113: 213–221, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.National Center for Health Statistics: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, Atlanta, GA, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2018. Available at: www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/index.htm. Accessed September 4, 2018

- 26.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AF 3rd, Feldman HI, et al.: CKD-EPI (Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration) : A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med 150: 604–612, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Selvin E, Manzi J, Stevens LA, Van Lente F, Lacher DA, Levey AS, et al.: Calibration of serum creatinine in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES) 1988-1994, 1999-2004. Am J Kidney Dis 50: 918–926, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.National Center for Health Statistics: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. 1999-2000 Data Documentation, Codebook, and Frequencies, Atlanta, GA, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2018. Available at: wwwn.cdc.gov/Nchs/Nhanes/1999-2000/LAB18.htm. Accessed September 4, 2018

- 29.National Center for Health Statistics: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. 2005-2006 Data Documentation, Codebook, and Frequencies, Atlanta, GA, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2018. Available at: wwwn.cdc.gov/Nchs/Nhanes/2005-2006/BIOPRO_D.htm Accessed September 4, 2018

- 30.National Kidney Foundation : K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: Evaluation, classification, and stratification. Am J Kidney Dis 39[Suppl 1]: S1–S266, 2002 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Levey AS, Eckardt KU, Tsukamoto Y, Levin A, Coresh J, Rossert J, et al.: Definition and classification of chronic kidney disease: A position statement from kidney disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO). Kidney Int 67: 2089–2100, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.International Expert Committee : International Expert Committee report on the role of the A1C assay in the diagnosis of diabetes. Diabetes Care 32: 1327–1334, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.National Center for Health Statistics: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey: Estimation Procedures, 2007-2010, Atlanta, GA, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2018. Available at: www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/series/sr_02/sr02_159.pdf. Accessed September 4, 2018

- 34.National Center for Health Statistics: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey: Estimation Procedures, 2011-2014, Atlanta, GA, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2018. Available at: www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/series/sr_02/sr02_177.pdf. Accessed September 4, 2018

- 35.American Diabetes Association : 4. Comprehensive medical evaluation and assessment of comorbidities: Standards of medical care in diabetes-2019. Diabetes Care 42[Suppl 1]: S34–S45, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.de Boer IH, Rue TC, Hall YN, Heagerty PJ, Weiss NS, Himmelfarb J: Temporal trends in the prevalence of diabetic kidney disease in the United States. JAMA 305: 2532–2539, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Afkarian M, Zelnick LR, Hall YN, Heagerty PJ, Tuttle K, Weiss NS, et al.: Clinical manifestations of kidney disease among US adults with diabetes, 1988-2014. JAMA 316: 602–610, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.