Significance Statement

Genetic hypercalciuric stone-forming rats, which universally and spontaneously form calcium phosphate stones, have a pathophysiology resembling that of human idiopathic hypercalciuria. The authors previously demonstrated that chlorthalidone, but not potassium citrate, decreased stone formation in this rat model. In this study, they investigated whether chlorthalidone and potassium citrate combined would reduce calcium phosphate stone formation more than either medication alone. They found that chlorthalidone was more effective than potassium citrate alone or combined with chlorthalidone in reducing stone formation and increasing mechanical strength and bone quality. However, replication of these findings in patients with nephrolithiasis is needed before concluding that chlorthalidone alone is more efficacious in this regard than potassium citrate alone or in combination with chlorthalidone.

Keywords: calcium, hypercalciuria, kidney stones

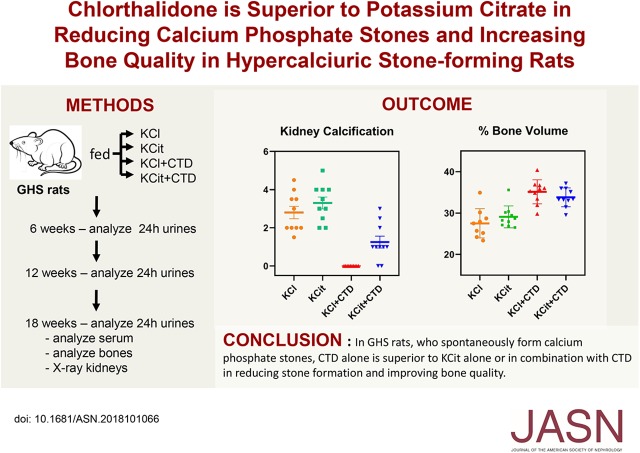

Visual Abstract

Abstract

Background

The pathophysiology of genetic hypercalciuric stone-forming rats parallels that of human idiopathic hypercalciuria. In this model, all animals form calcium phosphate stones. We previously found that chlorthalidone, but not potassium citrate, decreased stone formation in these rats.

Methods

To test whether chlorthalidone and potassium citrate combined would reduce calcium phosphate stone formation more than either medication alone, four groups of rats were fed a fixed amount of a normal calcium and phosphorus diet, supplemented with potassium chloride (as control), potassium citrate, chlorthalidone (with potassium chloride to equalize potassium intake), or potassium citrate plus chlorthalidone. We measured urine every 6 weeks and assessed stone formation and bone quality at 18 weeks.

Results

Potassium citrate reduced urine calcium compared with controls, chlorthalidone reduced it further, and potassium citrate plus chlorthalidone reduced it even more. Chlorthalidone increased urine citrate and potassium citrate increased it even more; the combination did not increase it further. Potassium citrate, alone or with chlorthalidone, increased urine calcium phosphate supersaturation, but chlorthalidone did not. All control rats formed stones. Potassium citrate did not alter stone formation. No stones formed with chlorthalidone, and rats given potassium citrate plus chlorthalidone had some stones but fewer than controls. Rats given chlorthalidone with or without potassium citrate had higher bone mineral density and better mechanical properties than controls, whereas those given potassium citrate did not.

Conclusions

In genetic hypercalciuric stone-forming rats, chlorthalidone is superior to potassium citrate alone or combined with chlorthalidone in reducing calcium phosphate stone formation and improving bone quality.

Idiopathic hypercalciuria (IH), an excess of urinary calcium (Ca) without a demonstrable metabolic cause, is the most common metabolic abnormality in patients who form Ca-based kidney stones.1–3 Elevated levels of urinary Ca increase the probability for nucleation and growth of calcium oxalate (CaOx) or calcium hydrogen phosphate (brushite) crystals into clinically significant kidney stones.4 Patients with IH generally have normal serum Ca, normal or elevated serum 1,25–dihydroxyvitamin D3, normal or elevated serum parathyroid hormone, and low bone mineral density (BMD).4,5 IH exhibits a polygenic mode of inheritance.3,6,7

To study this disorder we generated a strain of rats, the genetic hypercalciuric stone-forming (GHS) rats to model human IH. Selectively inbred for over 111 generations, GHS rats excrete approximately ten times the normal urine Ca of their parent Sprague–Dawley rats.8,9 When fed a normal Ca diet, all form calcium phosphate (CaP) kidney stones.10 We have shown that hypercalciuria in GHS rats is polygenic.11,12 Like patients with IH, these rats have increased intestinal Ca absorption,10,13 decreased renal Ca reabsorption,14 and increased bone resorption,15 leading to increased urine Ca excretion and CaP stone formation10,16,17 as well as a decrease in BMD.18,19 Serum 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 levels are normal.13,20,21

Two important strategies that are used to decrease recurrent stone formation in humans are the use of potassium citrate (KCit) or thiazide diuretics, alone or in combination.22,23 In humans both KCit and thiazides alone have been shown to decrease stone formation24; however, there is a paucity of data directly comparing the efficacy of these two medications in combination to prevent recurrent stone formation. We have previously shown that giving GHS rats thiazides (specifically chlorthalidone [CTD]) decreases urine Ca, reduces urine CaP supersaturation, and decreases stone formation.25 We also found that CTD improves BMD and bone quality in GHS rats.26 In a separate study we observed that giving GHS rats KCit also decreases urine Ca, but increases CaP supersaturation and does not decrease stone formation.27 In this study, we tested the hypothesis that CTD and KCit combined would more effectively reduce CaP stone formation and improve BMD and bone quality in GHS rats than either treatment alone.

Methods

Study Protocol

Three-month-old GHS rats from the 111th generation were randomly divided into four groups (each n=10) and housed individually in metabolic cages. All rats were fed a fixed amount of a normal Ca (1.2% Ca) and phosphorus (0.65%) diet, supplemented with either potassium chloride (4 mmol/d), KCit (4 mmol/d), CTD (1.25 mg/d) plus potassium chloride (to keep potassium intake constant), or KCit plus CTD, and had free access to deionized, distilled water. At weeks 6, 12, and 18, each rat was weighed and 24-hour urine was collected over 4 days, with two collections in thymol for pH, uric acid, and chloride, and two collections in hydrogen chloride for all other measurements. Each rat received an intraperitoneal injection of 1% calcein green at 10 and 2 days before being euthanized for dynamic histomorphometry. At 18 weeks, rats were euthanized and blood was collected via cardiac puncture. Kidneys, ureters, and bladders were removed for x-ray imaging in a Faxitron. Femurs, humeri, tibiae, and vertebral columns were harvested and prepared for BMD, histologic studies, and mechanical testing. The University of Rochester Committee for Animal Resources approved all procedures.

Urine and Serum Chemistries

Urine Ca, magnesium, phosphorus, ammonium, and creatinine were measured spectrophotometrically using a Beckman AU autoanalyzer (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA). Urine potassium, chloride, and sodium were measured by ion-specific electrodes on the Beckman AU and urine pH using a glass electrode. Urine citrate, oxalate, and sulfate were measured by ion chromatography using a Dionex ICS 2000 system (Dionex Corp., Sunnyvale, CA). Oxalate was measured enzymatically using oxalate oxidase. All urine solutes were measured at 6, 12, and 18 weeks and a mean value for each time period as well as an overall mean was calculated. Serum Ca and phosphorus were determined colorimetrically (BioVision, Milpitas, CA). Serum parathyroid hormone and Receptor activator of NF-κB ligand were determined by enzyme immunoassay (Immutopics, San Clemente, CA and R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). All of these methods have been used previously.16,26–30

Urine Supersaturation

Urine supersaturation with respect to CaOx and CaP solid phases were calculated from solute measurements using the computer program EQUIL2,31 as we have done previously.10,27,30,32–34

Kidney Stone Formation

Kidneys and ureters were removed from each rat en bloc, frozen, and imaged in a Faxitron radiography device (Tucson, AZ) to determine extent of kidney stone formation. Three observers blinded to treatment scored all radiographs on a scale ranging from 0 (no stones) to 4 (extensive stones).

Dual-Energy X-Ray Absorptiometry

Dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry with a Lunar PIXImus Bone Densitometer (Lunar GE, Mississauga, Canada) was used to determine tissue density and mineral content. The areal BMD, bone mineral content, and bone area were measured.

Microcomputed Tomography

Microcomputed tomography with an 1174 compact Micro-CT (Skyscan, Kontich, Belgium) was used to measure volumetric bone mineral density (vBMD) and microarchitecture of the mid-diaphysis of right femurs and L6 vertebrae. For vertebrae, density was measured between the growth plates, and for femurs, 1 mm above and below the midshaft of the bone. Measured parameters include femoral vBMD, anterior-posterior diameter, trabecular vBMD, bone volume (BV/TV), trabecular number (Tb.N), trabecular thickness (Tb.Th), and trabecular separation (Tb.Sp).

Tissue-Level Remodeling

Tissue-level remodeling was assessed via histomorphometry on both mineralized (undecalcified) bone and unmineralized (decalcified) bone. Stained sections were viewed microscopically and results quantified using computer software.

Undecalcified Histomorphometry

Undecalcified histomorphometry differentiates between mineralized and demineralized tissue in bones fixed in 70% ethanol. Sections were used for static and dynamic histomorphometric analysis. Cross-sections of the left distal tibiae were used for back-scattered electron microscopy.

Static Histomorphometry

Sections of undecalcified right tibiae were stained with Goldner trichrome and quantified using the Bioquant Osteo 11.2.6 MIR software (Bioquant Image Analysis, Nashville, TN). Trabecular bone was analyzed in the proximal tibia metaphysis region. Parameters measured include percent BV/TV, percent bone surface, Tb.N, Tb.Sp, Tb.Th, osteoid volume, percent osteoid volume per bone volume, osteoid surface, percent osteoid surface per bone surface, and osteoid width.

Dynamic Histomorphometry

Sections of calcein-labeled undecalcified right tibiae were used for dynamic histomorphometry and quantified using Bioquant Osteo 11.2.6 MIR software. Parameters measured include percent mineralized surface per bone surface, mineral apposition rate, bone formation rate normalized over bone surface, and bone formation rate normalized over bone volume.

Decalcified Histology

Sections of decalcified left tibiae were stained for tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase to measure osteoclasts for assessment of bone resorption and quantified using Bioquant Osteo 11.2.6 software. Trabecular bone of proximal tibial metaphysis was analyzed for osteoclast surface, percent osteoclast surface, number of osteoclasts, and number of osteoclasts per mm osteoclast surface.

Biomechanical Properties

Biomechanics of femurs were assessed using an Instron 4465 mechanical testing instrument (Instron, Burlington, Canada) and Labview 5.0 data acquisition software (National Instruments, Austin, TX) to define a load-displacement curve. Ultimate load, stiffness, ultimate displacement, and energy to break were calculated from the load-displacement curve. Data were normalized for specimen geometry to create a stress-strain curve to derive ultimate stress, failure strain, toughness, and the Young modulus.

Three-Point Bending

Three-point bending was performed on the right femurs to test the strength of the cortical bone.

Vertebral Compression

Vertebral compression was measured on excised L6 vertebrae. Vertebral compression does not result in complete fracture; the failure point was determined by an 8%–10% reduction in load.

Femoral Neck Fracture

The proximal end of the femurs was subjected to femoral neck fracture using an Instron 4465 to test the mechanical properties of cortical and trabecular bone combined.

Degree of Mineralization

Back-scattered electron microscopy on both right tibiae and left distal tibiae cross-section samples was done with a scanning electron microscope (XL300ESEM; Philips). Images were taken using a solid-state back-scattered electron microscopy detector (FEI Company, Hillsboro, OR).

Statistical Analyses

Urine analytes, serum values, and stone formation, expressed as mean±SEM, were compared among the four treatment groups (KCl, KCit, KCl+CTD, and KCit+CTD) by ANOVA with Bonferroni correction for pairwise comparison among the treatment groups (Statistica; StatSoft, Tulsa, OK). The main effects of the two drugs (KCit and CTD) and their interaction effects at 18 weeks were tested by comparing to potassium chloride (as control group) using linear regression models on urine analytes, serum values, and stone formation (SAS v9.4; StataCorp., Cary, NC), assuming normally distributed. Bone parameters were compared by t test using the SPSS Statistics 20 program (SPSS, Chicago, IL) and expressed as mean±SD. P<0.05 was considered significant.

Results

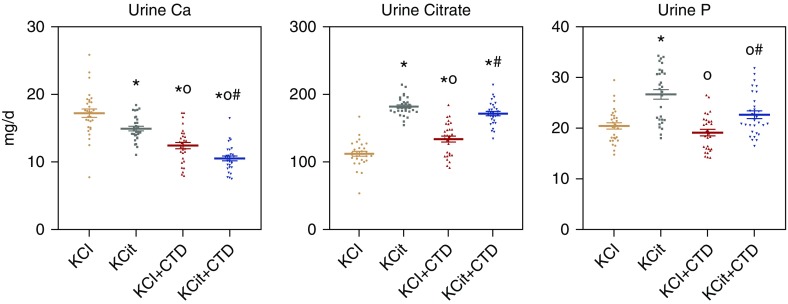

Urine and Serum

At the end of the study mean overall urine Ca for the entire 18-week study was significantly decreased in male rats fed KCit, CTD decreased urine Ca further, and KCit+CTD decreased it even more (Figure 1). Mean overall urine citrate was increased by both KCit and CTD alone; KCit+CTD was not different from KCit alone. Urine phosphorus was elevated by KCit but not by CTD or KCit+CTD, although urine phosphorus with KCit+CTD was greater than CTD alone.

Figure 1.

Urine Ca, citrate, and phosphorus (P) were significantly altered by KCit, CTD or KCit+CTD. Rat diets were supplemented with either potassium chloride (KCl; 4 mmol/d) as a control, KCit (4 mmol/d), CTD (1.25 mg/d) plus potassium chloride or KCit+CTD. Twenty-four hour urine collections were done at 6, 12, and 18 weeks for analysis of solute levels as described in Methods and an overall mean of all three collections was calculated. Results are mean±SEM for ten rats per group. *P<0.05 versus potassium chloride; oP<0.05 versus KCit alone; #P<0.05 versus CTD alone.

Although KCit alone and CTD alone each significantly decreased urine Ca, there was no significant drug interaction between KCit and CTD when urine Ca measurements at 18 weeks were analyzed (P=0.55). KCit alone and CTD alone increased urine citrate and there was a significant negative interaction effect when rats received both KCit+CTD (P=0.007). Only KCit alone significantly increased urine phosphorus and there was a significant negative interaction effect (P=0.02) when both KCit and CTD were given.

Mean overall urine oxalate was increased by KCit; however, oxalate was decreased with CTD and with KCit+CTD (Figure 2). Mean overall urine ammonium (NH4) was decreased by KCit and increased by CTD; the combination of KCit+CTD increased NH4 compared with KCit but decreased it compared with CTD alone. Mean overall urine pH was increased by KCit, decreased by CTD, and the combination was not different than KCit alone.

Figure 2.

Urine oxalate (Ox), NH4, and pH were significantly altered by KCit, CTD or KCit+CTD. Rat diets were supplemented with either potassium chloride (KCl; 4 mmol/d) as a control, KCit (4 mmol/d), CTD (1.25 mg/d) plus potassium chloride, or KCit+CTD. Twenty-four hour urine collections were done at 6, 12, and 18 weeks for analysis of solute levels as described in Methods and an overall mean of all three collections was calculated. Results are mean±SEM for ten rats per group. *P<0.05 versus potassium chloride; oP<0.05 versus KCit alone; #P<0.05 versus CTD alone.

There was a no significant drug interaction at 18 weeks (P=0.18) between the effects of KCit and CTD on urine oxalate. Although KCit decreased and CTD increased urine ammonium, there was a significant negative interaction effect (P=0.001) when both KCit and CTD were given. Although KCit increased and CTD decreased urine pH, there was a significant positive interaction effect (P=0.02) on pH when both KCit and CTD were given.

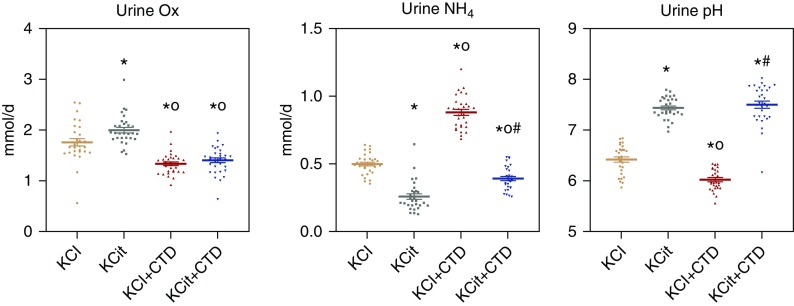

Mean overall urine supersaturation with respect to CaP was increased by KCit but not CTD, whereas KCit+CTD was not different from KCit alone (Figure 3). Supersaturation with respect to CaOx was decreased only by CTD, whereas KCit and KCit+CTD were not different from potassium chloride alone. There was no significant interaction between KCit and CTD for either CaP supersaturation (P=0.19) or CaOx supersaturation (P=0.50) at 18 weeks.

Figure 3.

Urine supersaturation (SS) of CaP and CaOx were differentially regulated by KCit, CTD or KCit+CTD. Rat diets were supplemented with either potassium chloride (KCl; 4 mmol/d) as a control, KCit (4 mmol/d), CTD (1.25 mg/d) plus potassium chloride, or KCit+CTD. Twenty-four hour urine collections were done at 6, 12, and 18 weeks for analysis of solute levels as described in Methods. These values were used to calculate relative supersaturation and an overall mean of all three collections was calculated. Values for relative supersaturation are unitless. Results are mean±SEM for ten rats per group. *P<0.05 versus potassium chloride; oP<0.05 versus KCit alone; #P<0.05 versus CTD alone.

At 18 weeks on each of the diets, serum values for sodium, potassium, bicarbonate, Ca, phosphorus, creatinine, and parathyroid hormone were not different between groups (Table 1). Serum chloride was significantly decreased by CTD compared with potassium chloride alone or KCit alone. Receptor activator of NF-κB ligand was significantly increased only by CTD+KCit compared with potassium chloride.

Table 1.

Serum measurements after 18 weeks in GHS rats fed KCl, KCit, CTD, or KCit+CTD

| Solute | KCl | KCit | KCl+CTD | KCit+CTD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sodium, mmol/d | 149.3±2.2 | 150.0±1.9 | 127.0±14.4 | 147.4±1.6 |

| Potassium, mmol/d | 4.37±0.09 | 4.76±0.29 | 4.04±0.04 | 4.62±0.45 |

| Chloride, mmol/d | 105.6±2.0 | 104.7±1.5 | 96.5±2.5a,b | 99.0±1.4 |

| Bicarbonate, mmol/d | 25.4±0.9 | 28.8±0.7 | 27.5±1.0 | 28.9±0.7 |

| Ca, mg/dl | 10.2±0.2 | 10.4±0.2 | 10.0±0.4 | 10.8±0.3 |

| Phosphate, mg/dl | 5.47±0.17 | 6.33±0.27 | 5.90±0.38 | 6.54±0.41 |

| Creatinine, mg/d | 0.30±0.03 | 0.29±0.01 | 0.25±0.01 | 0.27±0.01 |

| PTH, pg/ml | 612.2±179.4 | 669.4±180.9 | 168.7±22.8 | 350.7±64.5 |

| RANKL, pg/ml | 31.1±7.0 | 45.1±9.6 | 61.1±16.0 | 102.1±27.9a |

Results are mean±SEM for nine to ten rats per group. There were no significant differences comparing KCl+CTD to KCit+CTD. KCl, potassium chloride; PTH, parathyroid hormone; RANKL, Receptor activator of NF-κB ligand.

P<0.05 versus KCl alone

P<0.05 versus KCit alone.

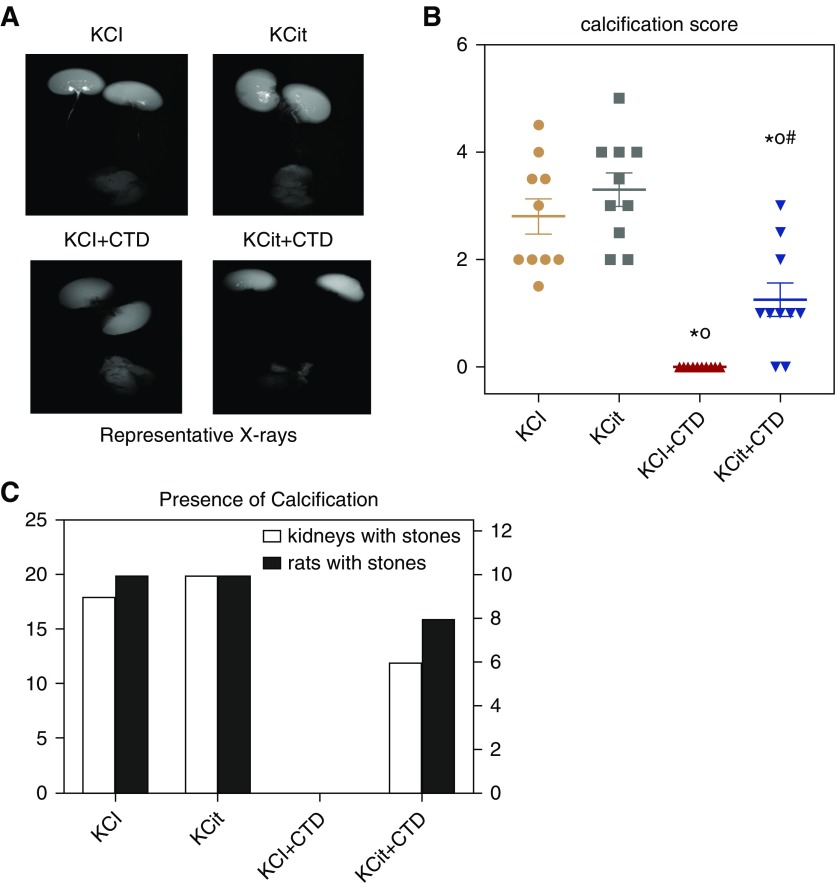

Stone Formation

Representative radiographs of kidneys at 18 weeks on the indicated diets are shown in Figure 4A. Quantitation of the radiographs from all the rats, done by three independent and blinded reviewers, is shown in Figure 4, B and C. Significant calcification was found in all rats fed the potassium chloride control diet. Potassium citrate had no effect on stone formation whereas CTD completely prevented stone formation. Stones were present with CTD+KCit and were significantly fewer than those given KCit alone but significantly greater than those given CTD. There was no significant interaction between KCit and CTD with respect to calcification score (P=0.18).

Figure 4.

Only CTD decreased kidney stones and calcification. At the conclusion of the 18-week study the extent of kidney stones and calcification were determined by three observers as described in Methods. (A) Representative x-rays of kidneys from rats receiving potassium chloride (KCl), KCit, CTD, or KCit+CTD. (B) Quantitation of stone formation and calcification in all rats (mean±SEM, n=10/group). (C) The number of kidneys (left+right) that contain any calcification (open bars) and the number of rats that exhibit any calcification (closed bars). *P<0.05 versus potassium chloride; oP<0.05 versus KCit alone; #P<0.05 versus CTD alone.

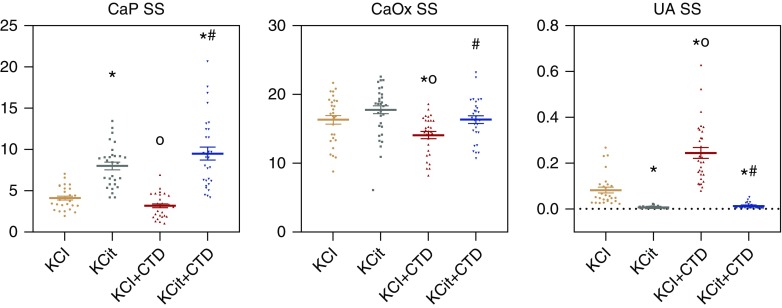

Bone

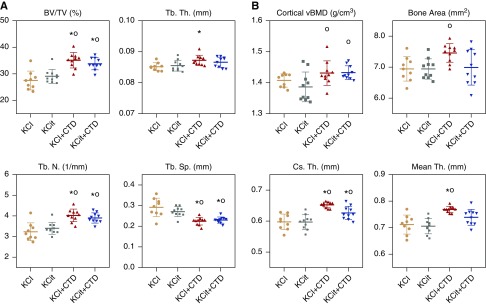

Microcomputed tomography analysis demonstrated that trabecular BV/TV in the L6 vertebrae was increased in both CTD and KCit+CTD compared with potassium chloride and KCit alone groups (Figure 5A). Tb.Th in L6 was increased by CTD compared with potassium chloride. Tb.N in L6 was increased by CTD and KCit+CTD compared with potassium chloride and KCit. Tb.Sp in L6 was decreased by CTD and CTD+KCit compared with potassium chloride and KCit.

Figure 5.

Increased trabecular and cortical bone density in response to CTD after 18 weeks. Rat diets were supplemented with either potassium chloride (KCl; 4 mmol/d) as a control, KCit (4 mmol/d), CTD (1.25 mg/d) plus potassium chloride, or KCit+CTD. At the conclusion of the 18-week study, bones were collected from all rats and analyzed as described in Methods. (A) Percent BV/TV, Tb.Th, Tb.N, and Tb.Sp of L6 vertebrae are presented. (B) Cortical vBMD, bone area, cortical thickness (Cs.Th), and mean thickness (Th) of femoral cortical bone are presented. Results are mean±SD for n=10 bones/group. *P<0.05 versus potassium chloride; oP<0.05 versus KCit alone; there were no significant differences comparing KCl+CTD to KCit+CTD.

Cortical bone from the femur of rats fed CTD or KCit+CTD demonstrated increased volumetric BMD (grams per centimeter squared) compared with KCit alone, whereas only CTD increased cross-sectional bone area compared with KCit (Figure 5B). Both CTD and KCit+CTD increased cortical thickness compared with potassium chloride or KCit, whereas mean cortical thickness was increased by CTD compared with potassium chloride and KCit.

Vertebral compression tests indicate that CTD and KCit+CTD supported a larger ultimate load compared with the potassium chloride control (Table 2). KCit+CTD had a larger fail load compared with potassium chloride. There were no differences in material properties of vertebral bone with any treatments. The results from three-point bending tests indicate that cortical bone from CTD fed rats supported a larger ultimate load compared with potassium chloride and KCit (Table 2). The cortical material properties demonstrated that KCit+CTD had a larger ultimate stress and larger modulus compared with potassium chloride.

Table 2.

Mechanical properties of trabecular (vertebral compression) and cortical (three- point bending) bone from GHS rats fed KCl, KCit, CTD, or KCit+CTD

| Bone Properties | KCl | KCit | KCl+CTD | KCIT+CTD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vertebral compression | ||||

| Structural properties | ||||

| Ultimate load, N | 163.5±9.1 | 176.3±51.4 | 213.1±34.8a | 217±42.5a |

| Fail load, N | 146.7±8.4 | 157.9±47.1 | 190.6±31.7 | 194.8±38.1a |

| Energy to fail, mJ | 95.8±25.8 | 136.3±95.3 | 151.2±46.1 | 156.6±45.4 |

| Stiffness, N/mm | 254.4±69.4 | 289.5±116.4 | 286.2±66.9 | 297.9±121.4 |

| Material properties | ||||

| Ultimate stress, MPa | 74.4±13.2 | 72.4±22.1 | 69.7±9.1 | 78.8±8.6 |

| Fail stress, MPa | 66.8±11.9 | 64.8±20.2 | 62.3±8.3 | 73.2±3.1 |

| Fail strain | 12.8±2.7 | 14.7±6.0 | 15.1±2.3 | 16.1±5.5 |

| Energy to fail, mJ/mm3 | 5.5±1.3 | 7.2±5.1 | 6.8±2.4 | 7.1±2.7 |

| Modulus, MPa | 908.1±313.3 | 928.8±390.6 | 782.2±227.9 | 805±316.1 |

| Three-point bending | ||||

| Structural properties | ||||

| Ultimate load | 169.9±11.2 | 176.9±18.5 | 194±8.5a,b | 185.8±12.6 |

| Fail load | 125.4±36 | 125.3±38.4 | 117.4±30.3 | 103.4±21 |

| Energy to fail | 155.4±41.2 | 139.3±34.7 | 152.4±26.9 | 153.2±38.6 |

| Stiffness | 332.2±17.2 | 333.7±39.4 | 349.9±14.3 | 348.8±35.4 |

| Material properties | ||||

| Ultimate stress | 126.3±15.2 | 133.9±16.3 | 142.9±11.3 | 152.3±16.7a |

| Fail stress | 93.5±28.6 | 94.5±29 | 86.3±21.9 | 79.3±9.2 |

| Fail strain | 11.9±2.2 | 10.9±1.79 | 11.2±1.71 | 13±2.3 |

| Energy to fail | 10.8±2.4 | 10±2.1 | 10.7±1.7 | 11.4±1.9 |

| Modulus | 2602.5±330.2 | 2646.7±344 | 2696±256.3 | 3089.7±485.1a |

Results are mean±SD for nine to ten rats per group. There were no significant differences comparing KCl+CTD to KCit+CTD. KCl, potassium chloride.

P<0.05 versus KCl alone.

P<0.05 versus KCit alone.

For dynamic undecalcified histomorphometry, the percent mineralized surface per bone surface measurement was lower in CTD compared with KCit (Table 3). Analysis of osteoclasts in decalcified bones demonstrated no differences between the groups.

Table 3.

Histomorphometry analyses of bones from GHS rats fed KCl, KCit, CTD, or KCit+CTD

| Histomorphometry | KCl | KCit | KCl+CTD | KCit+CTD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Undecalcified static | ||||

| OV/BV, % | 0.80±0.6 | 0.67±0.4 | 0.27±0.40 | 0.21±0.21 |

| OS/BS, % | 0.11±0.09 | 0.07±0.04 | 0.03±0.04 | 0.02±0.02 |

| Osteoid width, mm | 2.00±1.04 | 2.26±0.54 | 2.33±0.54 | 2.77±1.38 |

| Dynamic | ||||

| MS/BS, % | 0.11±0.07 | 0.2±0.08 | 0.1±0.05a | 0.16±0.08 |

| MAR, μm/d | 1.53±0.58 | 1.58±0.32 | 1.26±0.62 | 1.47±0.57 |

| BFR/BS, μm3/μm2 per d | 0.18±0.16 | 0.32±0.15 | 0.15±0.10 | 0.24±0.14 |

| Decalcified | ||||

| Oc.S, mm | 0.33±0.26 | 0.2±0.22 | 0.23±0.15 | 0.29±0.2 |

| Oc.S/BS, % | 0.05±0.04 | 0.03±0.03 | 0.03±0.02 | 0.05±0.04 |

| N.Oc | 4.70±3.9 | 4±4.5 | 4.2±3.7 | 4.2±2.9 |

| N.Oc/BS (1/mm) | 0.68±0.54 | 0.38±0.29 | 0.49±0.35 | 0.6±0.5 |

| N.Oc/Oc.s (1/mm) | 14.71±2.5 | 15.8±3.8 | 13.76±4.9 | 13.48±2.2 |

There were no significant differences comparing all groups to KCl alone or comparing KCl+CTD to KCit+CTD. Results are mean±SD for eight to ten rats per group. There were no significant differences comparing KCl+CTD to KCit+CTD. KCl, potassium chloride; OV/BV, % osteoid volume/bone volume; OS/BS, % osteoid surface/bone surface; MS/BS, mineralized surface/bone surface; MAR, mineral apposition rate; BFR/BS, bone formation rate/bone surface; Oc.S, osteoclast surface; Oc.S/BS, osteoclast surface/bone surface; N.Oc, number of osteoclasts; N.Oc/BS, number of osteoclasts/bone surface; N.Oc/Oc.s, number of osteoclasts/osteoclast surface.

P<0.05 versus KCit alone.

Discussion

IH is the most common metabolic abnormality in patients who form Ca-containing kidney stones. The increase in urinary Ca excretion increases supersaturation with respect to Ca-containing solid phases and enhances the probability for nucleation and growth of crystals into clinically significant kidney stones. Clinically the two main pharmacologic therapies to treat Ca-containing kidney stones are KCit and thiazide diuretics.22,23,35 A number of studies have demonstrated that both KCit36–39 and thiazide diuretics40–43 are each effective in reducing kidney stone formation. This study tests the hypothesis that combined therapy with KCit and CTD would more effectively decrease CaP kidney stone formation and increase bone quality in GHS rats compared with either treatment alone. The results clearly demonstrate that in GHS rats, CTD reduces kidney stone formation and improves bone density and quality better than the KCit or the combination of KCit+CTD in this rodent model of IH.

Similar to what we have demonstrated previously in GHS rats,27 administration of KCit led to an increase in urinary citrate, a reduction in urinary Ca and an increase in urinary phosphorus and oxalate. Citrate is absorbed in the intestine, which leads to systemic alkalization and a subsequent increase in citrate excretion.44 The mechanism by which citrate reduces urine Ca is multifactorial and the contribution of each factor to the reduction in urine Ca is not known.27 In the intestine, citrate binds Ca leading to a reduction in intestinal Ca absorption and subsequent urinary Ca excretion. The systemic alkalization induced by the intestinal absorption of citrate reduces bone resorption45 and increases the glomerular filtrate pH leading to a direct increase in tubular Ca reabsorption and a decrease in urinary Ca excretion. The increase in urine phosphorus may be secondary to citrate binding intestinal Ca, thus decreasing the availability of Ca to bind intestinal phosphorus, allowing more phosphorus to be absorbed and excreted. Similarly, the increase in urinary oxalate may be secondary to intestinal citrate binding Ca, freeing oxalate for absorption and subsequent excretion. In addition, there appears to be a close relationship and interaction between the murine anion transporter Slc26a6, which has specificity for chloride/oxalate exchange, and the citrate transporter NaDC-1.46 NaDC-1 enhances Slc26a6 transport activity, and there is a reciprocal inhibition of NaDC-1 by Slc26a6 to regulate oxalate/citrate homeostasis.

As expected, the administration of CTD to GHS rats led to a reduction in urinary Ca excretion and an increase in urine citrate excretion.25 This reduction in urinary Ca is due to increased renal tubular Ca reabsorption.14 We have previously shown that in both rats25 and humans,47 this decrease in urinary Ca persists as the result of a thiazide-induced reduction in intestinal Ca absorption. The fall in urine oxalate excretion in the CTD-treated rats may be secondary to this reduction in intestinal Ca absorption leading to greater luminal Ca and more CaOx binding in the intestine.

The initial CaP solid phase is similar to the type of stones that the GHS rats spontaneously form.10 CTD alone reduced supersaturation with respect to CaP and to CaOx. Because GHS rats fed a standard diet form only CaP stones, the reduction in CaP supersaturation may guide stone formation. Supporting this hypothesis we have previously shown that CaP stone formation closely follows urine supersaturation with respect to the CaP solid phase in GHS rats. When we reduced dietary phosphate in GHS rats, we could eliminate stone formation when CaP supersaturation was less than approximately 3.8.10 Similarly, in this study, there was universal stone formation at a CaP supersaturation of 4.1 and none at a supersaturation of 3.2 (Figure 3). Here KCit, with or without CTD, led to a significant increase in supersaturation with respect to the CaP solid phase. This suggests that the increase in monohydrogen phosphate secondary to the increase in urine pH more than offsets the fall in urine Ca and the increase in urine citrate induced by the alkali loading. Stone formation was not altered with KCit alone but was reduced somewhat when CTD was added to KCit. Thus, the lowest numerical value of CaP supersaturation, induced by CTD alone, led to the fewest stones. This suggests that, at least in GHS rats, CTD is superior to KCit, either alone or in combination with CTD, in lowering supersaturation with respect to CaP and in suppressing CaP stone formation.

In considering a direct interaction between the effects of KCit and the effects of CTD, there were differences in some, but not all, urine parameters that demonstrated a significant interaction effect when rats received both KCit+CTD. There was a significant negative interaction effect on urine citrate, urine phosphorus, and urine ammonium when both drugs were given. There was a significant positive interaction effect on urine pH when both drugs were given. There was no significant interaction on urine Ca or oxalate when both drugs were given. However, with respect to prevention of stone formation, the importance of a drug interaction between KCit and CTD on these individual urine parameters is not clear, as there was no significant interaction for the differences in urine CaOx supersaturation, CaP supersaturation, or kidney calcification when both drugs were given.

In this study, KCit led to an increase in urinary pH whereas CTD led to a fall in urinary pH. In the vast majority of humans with Ca stones treated with a standard dose of the alkali KCit, urine pH increases.22,23 Whether urinary supersaturation increases with respect to the CaP and CaOx solid phases depends on whether citrate excretion increases and Ca excretion decreases sufficiently to offset the effect of an increase in pH.48 The relative benefit versus risk of citrate in humans with CaP stones is frequently debated in the kidney stone community. However, there are no prospective trials of stone prevention in CaP stone disease, so this is one of the reasons we pursued this study in GHS rats.

A direct consequence of hypercalciuria and subsequent stone formation is a loss of bone mineral, potentially leading to an increase in fracture risk in patients with IH.49 We found that bones from rats given CTD demonstrated increased bone strength and improved mechanical properties compared with KCit, suggesting that bone quality was significantly improved with CTD but not KCit. Overall mechanical testing found that CTD and KCit+CTD increased both cortical and trabecular structural properties of the bone more than KCit alone. CTD increased the ultimate load of both cortical and trabecular bone. Additionally, the KCit+CTD group was effective in improving the ultimate stress and modulus in the cortical bone compared with the control. This agrees with the microcomputed tomography results as CTD, without or with KCit, also led to a larger vBMD and BV/TV compared with KCit or potassium chloride alone. We previously found that CTD improved Tb.N and BV/TV in GHS rats.25,26 These results were confirmed in this study, further supporting the observation that CTD improves bone quality. The results presented here also indicate that a combination of KCit+CTD led to improved mechanical strength and bone quality compared with the potassium chloride control or KCit, but was not different compared with CTD alone.

There have been a number of human studies on the effect of thiazides and/or KCit on bone that have concluded that each treatment has a favorable effect on BMD.35 Adams et al.50 gave thiazides to five hypercalciuric, osteoporotic males and found an increase in BMD after 9 months. In a study using bone biopsies before and after thiazide administration to hypercalciuric stone formers, Steiniche et al. found a reduction in bone turnover after 6 months of treatment.51 Sakhaee et al. studied eight patients with hypercalciuria and a slight elevation in parathyroid hormone and found that after 1 year, the use of thiazide diuretics reduced the secondary hyperparathyroidism and reduced fractional resorption surfaces.49 Thiazides are commonly prescribed as treatment for hypertension. In a meta-analysis encompassing 21 observational studies of almost 400,000 patients, the use of thiazide diuretics was associated with a significant 24% reduction in the risk of hip fracture.52 Pak et al.53 studied the effect of KCit on vertebral BMD in patients with Ca urolithiasis and found increased vertebral BMD after 11 months of treatment. Vescini et al.54 examined the long-term effects of KCit on distal radius BMD in patients with hypercalciuria and also concluded that long term treatment with KCit improved the BMD. These studies did not examine the mechanical properties of the bone. A recent study utilizing computed tomography scans to determine BMD found that both thiazides and KCit improved BMD.55 In our study, we again demonstrate that CTD improves BMD and the mechanical properties of bone,26 consistent with observations in humans.47 However, our results with KCit in GHS rats, in which we find no improvement in bone density or quality, differ from the observations in humans. Perhaps with longer treatment, as in the human studies, KCit would be efficacious in improving bone density and quality in the GHS rats.

In conclusion, in GHS rats who universally spontaneously form CaP stones, a diet containing CTD alone is superior to KCit alone or KCit+CTD in reducing stone formation, increasing BMD, and improving bone quality. If these findings in GHS rats are replicated in patients with nephrolithiasis, treatment of recurrent hypercalciuric Ca stone formation with CTD alone is preferable to treatment with KCit or the combination of KCit+CTD both to decrease stone formation and to maintain BMD and quality. Whether adding KCit to CTD when treating CaOx stones is better than either drug alone remains to be studied.

Disclosures

Dr. Krieger reports stock, stock options, spouse is a consultant for Tricida, stock from Amgen, spouse-speaking fees from Sanofi/Genzyme, spouse is a consultant from Relypsa/Vifor/Fresenius, spouse is an adjudicator for adverse events from Novo Nordisk/Covance, grants from National Institutes of Health, grants from Renal Research Institute. Dr. Asplin is an employee of Litholink Corporation. Dr. Ramos has nothing to disclose. Dr. Flotteron has nothing to disclose. Dr. Granja is an employee of Litholink Corporation. Dr. Chen has nothing to disclose. Dr. Wu has nothing to disclose. Dr. Grynpas has nothing to disclose. Dr. Bushinsky reports personal fees and consultant, stock and stock options from Tricida, personal fees and stock from Amgen, speaking fees from Sanofi/Genzyme, personal fees and consultant from Relypsa/Vifor/Fresenius, personal fees from Novo Nordisk/Covance, grants from National Institutes of Health, grants from Renal Research Institute.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Bushinsky and Dr. Asplin designed the study. Mr. Ramos, Ms. Flotteron, Mr. Granja and Dr. Chen carried out the experiments. Dr. Krieger, Dr. Asplin, Dr. Wu, Dr. Grynpas, and Dr. Bushinsky analyzed the data. Dr. Krieger made the figures. Dr. Krieger, Dr. Asplin, Dr. Grynpas, and Dr. Bushinsky drafted and revised the paper, all authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

This work was supported by grant RO1 DK075462 from the National Institutes of Health to Dr. Bushinsky.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

References

- 1.Bose A, Monk RD, Bushinsky DA: Kidney stones. In: Williams Textbook of Endocrinology, 13th Ed., edited by Melmed S, Polonsky KS, Larsen PR, Kronenberg HM, Philadelphia, Elsevier, 2016, pp 1365–1384 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Monk RD, Bushinsky DA: Nephrolithiasis and nephrocalcinosis. In: Comprehensive Clinical Nephrology, 5th Ed., edited by Johnson RJ, Frehally J, Floege J, Philadelphia, Elsevier, 2015, pp 688–702 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moe OW, Bushinsky DA: Genetic hypercalciuria: A major risk factor in kidney stones. In: Genetics of Bone Biology and Skeletal Disease, edited by Thakker RV, Whyte MP, Eisman JA, Igarashi T, London, UK, Elsevier, 2013, pp 585–604 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bushinsky DA, Coe FL, Moe OW: Nephrolithiasis. In: The Kidney, 9th Ed., edited by Brenner BM, Philadelphia, W.B. Saunders, 2012, pp 1455–1507 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moe OW, Bonny O: Genetic hypercalciuria. J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 729–745, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stechman MJ, Loh NY, Thakker RV: Genetics of hypercalciuric nephrolithiasis: Renal stone disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1116: 461–484, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Monico CG, Milliner DS: Genetic determinants of urolithiasis. Nat Rev Nephrol 8: 151–162, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bushinsky DA: Bench to bedside: Lessons from the genetic hypercalciuric stone-forming rat. Am J Kidney Dis 36: LXI–LXIV, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bushinsky DA, Frick KK, Nehrke K: Genetic hypercalciuric stone-forming rats. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 15: 403–418, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bushinsky DA, Parker WR, Asplin JR: Calcium phosphate supersaturation regulates stone formation in genetic hypercalciuric stone-forming rats. Kidney Int 57: 550–560, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoopes RR Jr, Reid R, Sen S, Szpirer C, Dixon P, Pannett AA, et al.: Quantitative trait loci for hypercalciuria in a rat model of kidney stone disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 14: 1844–1850, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoopes RR Jr, Middleton FA, Sen S, Hueber PA, Reid R, Bushinsky DA, et al.: Isolation and confirmation of a calcium excretion quantitative trait locus on chromosome 1 in genetic hypercalciuric stone-forming congenic rats. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 1292–1304, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li XQ, Tembe V, Horwitz GM, Bushinsky DA, Favus MJ: Increased intestinal vitamin D receptor in genetic hypercalciuric rats. A cause of intestinal calcium hyperabsorption. J Clin Invest 91: 661–667, 1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsuruoka S, Bushinsky DA, Schwartz GJ: Defective renal calcium reabsorption in genetic hypercalciuric rats. Kidney Int 51: 1540–1547, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krieger NS, Stathopoulos VM, Bushinsky DA: Increased sensitivity to 1,25(OH)2D3 in bone from genetic hypercalciuric rats. Am J Physiol 271: C130–C135, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Asplin JR, Bushinsky DA, Singharetnam W, Riordon D, Parks JH, Coe FL: Relationship between supersaturation and crystal inhibition in hypercalciuric rats. Kidney Int 51: 640–645, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bushinsky DA, Grynpas MD, Nilsson EL, Nakagawa Y, Coe FL: Stone formation in genetic hypercalciuric rats. Kidney Int 48: 1705–1713, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grynpas M, Waldman S, Holmyard D, Bushinsky DA: Genetic hypercalciuric stone-forming rats have a primary decrease in BMD and strength. J Bone Miner Res 24: 1420–1426, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ng AH, Frick KK, Krieger NS, Asplin JR, Cohen-McFarlane M, Culbertson CD, et al.: 1,25(OH)2D3-induces a mineralization defect and loss of bone mineral density in genetic hypercalciuric stone-forming rats. Calcif Tissue Int 94: 531–543, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yao J, Kathpalia P, Bushinsky DA, Favus MJ: Hyperresponsiveness of vitamin D receptor gene expression to 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. A new characteristic of genetic hypercalciuric stone-forming rats. J Clin Invest 101: 2223–2232, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karnauskas AJ, van Leeuwen JP, van den Bemd GJ, Kathpalia PP, DeLuca HF, Bushinsky DA, et al.: Mechanism and function of high vitamin D receptor levels in genetic hypercalciuric stone-forming rats. J Bone Miner Res 20: 447–454, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Coe FL, Worcester EM, Evan AP: Idiopathic hypercalciuria and formation of calcium renal stones. Nat Rev Nephrol 12: 519–533, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zisman AL: Effectiveness of treatment modalities on kidney stone recurrence. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 12: 1699–1708, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fink HA, Wilt TJ, Eidman KE, Garimella PS, MacDonald R, Rutks IR, et al.: Medical management to prevent recurrent nephrolithiasis in adults: A systematic review for an American College of physicians clinical guideline. Ann Intern Med 158: 535–543, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bushinsky DA, Asplin JR: Thiazides reduce brushite, but not calcium oxalate, supersaturation, and stone formation in genetic hypercalciuric stone-forming rats. J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 417–424, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bushinsky DA, Willett T, Asplin JR, Culbertson C, Che SPY, Grynpas M: Chlorthalidone improves vertebral bone quality in genetic hypercalciuric stone-forming rats. J Bone Miner Res 26: 1904–1912, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krieger NS, Asplin JR, Frick KK, Granja I, Culbertson CD, Ng A, et al.: Effect of potassium citrate on calcium phosphate stones in a model of hypercalciuria. J Am Soc Nephrol 26: 3001–3008, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Asplin JR, Donahue SE, Lindeman C, Michalenka A, Strutz KL, Bushinsky DA: Thiosulfate reduces calcium phosphate nephrolithiasis. J Am Soc Nephrol 20: 1246–1253, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Frick KK, Asplin JR, Favus MJ, Culbertson C, Krieger NS, Bushinsky DA: Increased biological response to 1,25(OH)(2)D(3) in genetic hypercalciuric stone-forming rats. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 304: F718–F726, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Frick KK, Asplin JR, Krieger NS, Culbertson CD, Asplin DM, Bushinsky DA: 1,25(OH)2D3-enhanced hypercalciuria in genetic hypercalciuric stone-forming rats fed a low-calcium diet. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 305: F1132–F1138, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Werness PG, Brown CM, Smith LH, Finlayson B: EQUIL2: A BASIC computer program for the calculation of urinary saturation. J Urol 134: 1242–1244, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bushinsky DA, Neumann KJ, Asplin J, Krieger NS: Alendronate decreases urine calcium and supersaturation in genetic hypercalciuric rats. Kidney Int 55: 234–243, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bushinsky DA, Bashir MA, Riordon DR, Nakagawa Y, Coe FL, Grynpas MD: Increased dietary oxalate does not increase urinary calcium oxalate saturation in hypercalciuric rats. Kidney Int 55: 602–612, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bushinsky DA, Asplin JR, Grynpas MD, Evan AP, Parker WR, Alexander KM, et al.: Calcium oxalate stone formation in genetic hypercalciuric stone-forming rats. Kidney Int 61: 975–987, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moe OW, Pearle MS, Sakhaee K: Pharmacotherapy of urolithiasis: Evidence from clinical trials. Kidney Int 79: 385–392, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Barcelo P, Wuhl O, Servitge E, Rousaud A, Pak CY: Randomized double-blind study of potassium citrate in idiopathic hypocitraturic calcium nephrolithiasis. J Urol 150: 1761–1764, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ettinger B, Pak CY, Citron JT, Thomas C, Adams-Huet B, Vangessel A: Potassium-magnesium citrate is an effective prophylaxis against recurrent calcium oxalate nephrolithiasis. J Urol 158: 2069–2073, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lojanapiwat B, Tanthanuch M, Pripathanont C, Ratchanon S, Srinualnad S, Taweemonkongsap T, et al.: Alkaline citrate reduces stone recurrence and regrowth after shockwave lithotripsy and percutaneous nephrolithotomy. Int Braz J Urol 37: 611–616, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Soygür T, Akbay A, Küpeli S: Effect of potassium citrate therapy on stone recurrence and residual fragments after shockwave lithotripsy in lower caliceal calcium oxalate urolithiasis: A randomized controlled trial. J Endourol 16: 149–152, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ettinger B, Citron JT, Livermore B, Dolman LI: Chlorthalidone reduces calcium oxalate calculous recurrence but magnesium hydroxide does not. J Urol 139: 679–684, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fernández-Rodríguez A, Arrabal-Martín M, García-Ruiz MJ, Arrabal-Polo MA, Pichardo-Pichardo S, Zuluaga-Gómez A: [The role of thiazides in the prophylaxis of recurrent calcium lithiasis]. Actas Urol Esp 30: 305–309, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Laerum E, Larsen S: Thiazide prophylaxis of urolithiasis. A double-blind study in general practice. Acta Med Scand 215: 383–389, 1984 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Borghi L, Meschi T, Guerra A, Novarini A: Randomized prospective study of a nonthiazide diuretic, indapamide, in preventing calcium stone recurrences. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 22[Suppl 6]: S78–S86, 1993 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sakhaee K, Williams RH, Oh MS, Padalino P, Adams-Huet B, Whitson P, et al.: Alkali absorption and citrate excretion in calcium nephrolithiasis. J Bone Miner Res 8: 789–794, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bushinsky DA: Metabolic alkalosis decreases bone calcium efflux by suppressing osteoclasts and stimulating osteoblasts. Am J Physiol 271: F216–F222, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ohana E, Shcheynikov N, Moe OW, Muallem S: SLC26A6 and NaDC-1 transporters interact to regulate oxalate and citrate homeostasis. J Am Soc Nephrol 24: 1617–1626, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Coe FL, Parks JH, Bushinsky DA, Langman CB, Favus MJ: Chlorthalidone promotes mineral retention in patients with idiopathic hypercalciuria. Kidney Int 33: 1140–1146, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Preminger GM, Sakhaee K, Skurla C, Pak CY: Prevention of recurrent calcium stone formation with potassium citrate therapy in patients with distal renal tubular acidosis. J Urol 134: 20–23, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sakhaee K, Maalouf NM, Kumar R, Pasch A, Moe OW: Nephrolithiasis-associated bone disease: Pathogenesis and treatment options. Kidney Int 79: 393–403, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Adams JS, Song CF, Kantorovich V: Rapid recovery of bone mass in hypercalciuric, osteoporotic men treated with hydrochlorothiazide. Ann Intern Med 130: 658–660, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Steiniche T, Mosekilde L, Christensen MS, Melsen F: Histomorphometric analysis of bone in idiopathic hypercalciuria before and after treatment with thiazide. APMIS 97: 302–308, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Aung K, Htay T: Thiazide diuretics and the risk of hip fracture. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (10): CD005185, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pak CYC, Peterson RD, Poindexter J: Prevention of spinal bone loss by potassium citrate in cases of calcium urolithiasis. J Urol 168: 31–34, 2002 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vescini F, Buffa A, La Manna G, Ciavatti A, Rizzoli E, Bottura A, et al.: Long-term potassium citrate therapy and bone mineral density in idiopathic calcium stone formers. J Endocrinol Invest 28: 218–222, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Alshara L, Batagello CA, Armanyous S, Gao T, Patel N, Remer EM, et al.: The impact of thiazides and potassium citrate on bone mineral density evaluated by CT scan in stone formers. J Endourol 32: 559–564, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]