Abstract

The tumor, node, metastasis (TNM) staging system approved by International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer (IASLC) and the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) to stage lung cancer was recently revised. The latest revision is the 8th edition published in January, 2017. This new edition made some important changes to the previous edition, including modification of the T classification based on 1 cm increment, downstage of T descriptor including endobronchial tumor disregarding its distance from carina (T2), merging total and partial atelectasis/pneumonitis into the same T category (T2), upstage diaphragmatic invasion to T4, new classification concept of adenocarcinoma in situ and minimally invasive adenocarcinoma for pure and part-solid ground-glass nodules, and further division of extrathoracic metastasis into M1b and M1c based on the number and sites of extrathoracic metastases. Consensus is reached for debating situations not covered in the previous edition of staging system, such as the classification of pancoast tumor based on its invasion depth and staging tumors that extend directly across the fissure as T2a. Classification of multiple sites of pulmonary involvement, including multiple primary lung cancer, separate lung cancer nodules, multiple ground-glass or lepidic lesions, and consolidation, is also discussed. Even though the 8th edition of the TNM lung staging system provides us with more precise classification based on prognostic analysis of each TNM descriptors, there are still some potential limitations and clinical situations that have not yet been clarified in terms of clinical staging by imaging. It is important for radiologists to understand the major changes introduced in the 8th edition of TNM staging and to recognize the potential pitfalls and limitations of imaging interpretation to precisely classify the clinical stage of lung cancer.

Among all present diagnostic cancers, lung cancer is the second leading cancer but the leading cause of cancer-related death in both sexes (1). It is important to stage lung cancer based on various descriptors that have great influence on the prognosis. International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer (IASLC) is recognized as the primary source of data-based evidence for classification of thoracic cancer and has made multiple revisions based on enlarging survival database throughout time (2). The tumor, node, metastasis (TNM) staging system by IASLC is used by the Union for International Cancer Control (UICC) and the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) to stage lung cancer. The latest one is the AJCC 8th edition of TNM Staging System published in January, 2017 (3). This revision was derived from the most thorough database incorporated with 94708 lung cancer patients around the world from 1999–2010 (3). The cases were collected from 46 centers in more than 19 countries, with the majority of patients from Europe and Asia. The analysis of this database was performed by the nonprofit organization, Cancer Research and Biostatics (CRAB), and resulted in few important changes from previous TNM staging system based on validating the 7th TNM staging system and expanding prognostic data collected from global medical centers (2, 3). Considering the revised components, it seems that the 8th edition took clinical imaging studies into consideration, especially CT scans.

Although there had been recent articles concerning the revision of the 8th edition of lung cancer staging, emphasis on imaging aspects and potential limitations of clinical staging remain to be clarified from the diagnostic standpoint of a radiologist. In this article, we discuss the changes with applicability to radiology and point out potential imaging interpretation pitfalls of the 8th edition of the UICC/AJCC TNM staging system.

TNM descriptors of the new 8th edition with pictorial illustrations and main concern on imaging staging

The T descriptor

The T descriptor of the new 8th TNM staging system is composed of tumor size, tumor invasion, and location of separate tumor with respect to the primary tumor. For the 8th edition, the tumor size is more precisely classified, in increments of 1 cm, based on prognostic differentiation validated on a total of 33115 patients with known non-small cell lung tumor sizes without metastasis (2). Running log-rank statistics was used to assess tumor size cutoff points, with results validating the cutoff point of 7th edition to be remained at 3 cm for T1 and T2 tumors. Multivariate Cox regression analysis, adjusted for age, sex, histologic type, and geographic region, was used to evaluate T descriptors and found a distinct 5-year prognosis for every centimeter increment in tumor size between 1 and 5 cm (2). The cutoff point of 5 cm further separates T3 from T2 as the 5-year survival of patients significantly decreased from 60%–65% to 52%–57% when tumor is >5 cm. Additionally, T3 and T4 are distinguished by the cutoff of 7 cm, as the 5-year survival rate further shifted to 38%–47% for patients with T4 diseases (2).

New T category of Tis and T1mi are introduced to the 8th edition of AJCC lung cancer staging of adenocarcinoma. Studies have shown that the lepidic component of lung adenocarcinoma was correlated with the ground glass appearance on CT, while the invasive adenocarcinoma component was correlated with the solid parts of part-solid nodules (4). In the 7th edition, the term Tis is only used for squamous cell carcinoma in situ, but in the 8th edition, Tis can also be applied to adenocarcinoma in situ. For tumor of pure lepidic adenocarcinoma that appears as ground-glass nodule ≤ 3 cm in total size, the 8th edition reclassifies them as Tis, tumor in situ. It is considered T1a only if the pure ground-glass nodule is >3 cm. T1mi (minimally invasive) is a term used to classify lepidic predominant adenocarcinoma, which appears as part-solid nodules ≤3 cm in total size, with the solid part ≤0.5 cm in size (2). A part-solid tumor, with a total size ≤3 cm and a solid part larger than 0.5 cm, is classified as T1a if its solid part is 0.6–1.0 cm, T1b if 1.1–2.0 cm, and T1c if 2.1–3.0 cm (5).

Additionally, the T category is directed by tumor invasion to adjacent structures. Tumor involvement of a main bronchus is downstaged from T3 to T2 regardless of the distance from the carina. Likewise, total atelectasis or pneumonitis involving the whole lung is also downstaged from T3 to T2, same as partial atelectasis or pneumonitis, based on similar prognosis. However, for diaphragmatic invasion, the new 8th edition upstages this T descriptor from T3 to T4 as the prognosis is analogous to other T4 descriptors (6). Involvement of mediastinal pleura is deleted as a T descriptor (5).

Furthermore, visceral pleural invasion is considered as a T descriptor for the T2 category. Study had found that pleural invasion involving the pleural surface presented worse prognosis than involvement beyond the elastic layer but still within the visceral pleura (7). Thus, it is recommended to further use elastic stains to assure the degree of visceral pleural invasion for patients who are in high suspicion of pleural invasion.

In summary, the clinical T descriptors in the 8th TNM classification are now grouped into five main categories, Tis, T1, T2, T3, and T4, with further subdivision of T1 and T2 categories (Table 1).

Table 1.

T classification for appearance on chest CT for TNM 8th edition

| T classification | T components on CT | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Tis (AIS) | Pure GGN ≤ 3 cm | ||

|

| |||

| T1 | T1mi | ≤ 0.5 cm solid part within part-solid tumor total size ≤3 cm | |

| T1a | 0.6–1.0 cm solid part within part-solid tumor total size ≤3 cm | ||

| Pure GGN >3 cm | |||

| ≤ 1 cm solid tumor | |||

| T1b | 1.1–2.0 cm solid part within part-solid tumor total size ≤3 cm | ||

| >1–2 cm solid tumor | |||

| T1c | 2.1–3 cm solid part within part-solid tumor total size ≤3 cm | ||

| >2–3 cm solid tumor | |||

|

| |||

| T2 | T2a | 3.1–4 cm | Involves main bronchus without involvement of carina |

| T2b | 4.1–5 cm | Total/partial atelectasis | |

| Total/partial pneumonitis | |||

| Involves hilar fat | |||

| Involves visceral pleura (PL1 or PL2) | |||

|

| |||

| T3 | 5.1–7 cm | Separate tumor nodules in the same lobe as the primary | |

| Involves parietal pleura (PL3) | |||

| Parietal pericardium | |||

| Chest wall | |||

| Phrenic nerve | |||

|

| |||

| T4 | >7 cm | Involves diaphragm | |

| Mediastinal fat or other mediastinal structures (trachea, great vessels, heart, recurrent laryngeal nerve, esophagus) | |||

| Carina | |||

| Vertebral body | |||

| Visceral pericardium | |||

| Separate tumor nodules in the same lung but different lobes as the primary | |||

CT, computed tomography; AIS, adenocarcinoma in situ; GGN, ground-glass nodules; mi, minimally invasive; PL1, tumor invasion of the elastic layer of visceral pleura without reaching the visceral pleural surface; PL2, tumor invasion of the visceral pleural surface; PL3, tumor invasion of the parietal pleura or chest wall.

Tis is assigned for carcinoma in situ of adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma with CT appearances as pure ground-glass nodules that are ≤3 cm (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Chest CT showed pure ground-glass nodule of 0.8 cm in diameter (arrow) in a 45-year-old woman with frozen section showing adenocarcinoma in situ of right upper lobe of the lung without definite stromal invasion or lymphovascular permeation. In the 8th edition of TNM imaging staging, it will be staged as Tis.

The new classification subdivides T1 lung cancer measuring ≤ 3 cm into T1a, T1b, and T1c, based on tumor sizes of invasive solid parts of subsolid nodules and total size of solid nodules, which are 0.6–1.0 cm for T1a, 1.1–2.0 cm for T1b, and 2.1–3 cm for T1c (Fig. 2). Minimally invasive adenocarcinomas are classified as T1(mi) when the invasive component is ≤0.5 cm in a total size of ≤3 cm (2, 5). As for pure ground-glass nodules larger than 3 cm, they are classified as T1a (5).

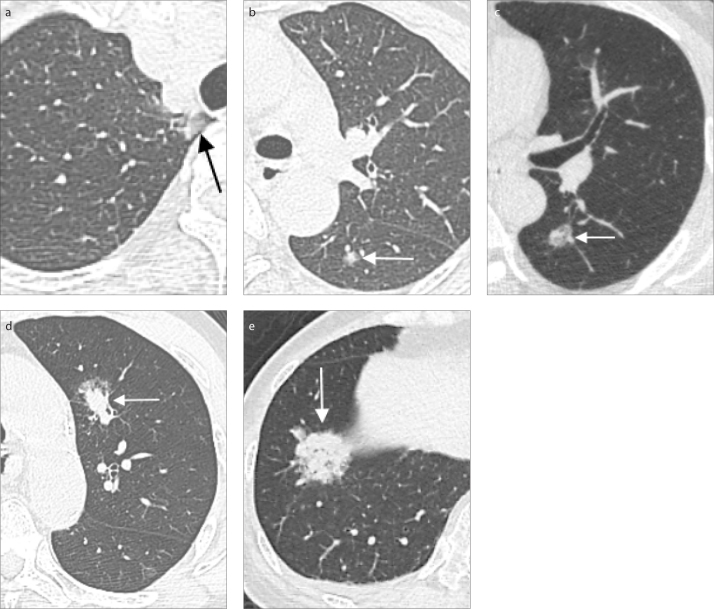

Figure 2. a–e.

Part-solid nodules of various sizes that correspond to different T stages. Chest CT images (a, b) of a 55-year-old female with two part-solid nodules, one found in the apical segment of the right upper lobe of the lung with total diameter of 1.0 cm and a solid component of 0.3 cm (a, arrow), and the other noted in the superior segment of the left lower lobe of the lung with a diameter of 0.7 cm and a solid component of 0.4 cm (b, arrow). Pathology proved adenocarcinoma of lung. The imaging staging was cT1mi (m), m for multiple nodules. CT image (c) of a part-solid nodule with a solid component measuring up to 0.8 cm in maximum diameter with total size of 1.8 cm (arrow), imaging staging T1a, in a 53-year-old man with pathology showing non-small cell carcinoma. Lung CT image (d) of a 62-year-old male, a case of esophageal cancer, pT2N0M0, status post thoracoscopic esophagectomy and gastric tube reconstruction. Follow-up chest CT found one part-solid nodule up to 1.8 cm with 1.2 cm solid part (arrow) in the left upper lobe without obvious lymph node and distant metastasis, imaging staging T1a (≤2 cm) in the 7th edition and T1b in the 8th edition, suspected primary lung cancer. Pathology showed moderately differentiated mixed mucinous and acinar adenocarcinoma and hilar/mediastinum lymph node metastasis. Lung CT image (e) of a 76-year-old female with incidental finding of a 2.8 cm part-solid tumor with a solid part measuring up to 2.7 cm (arrow), located at the right lower lobe of the lung. Imaging staging of AJCC 8th edition is T1c. CT-guided biopsy revealed adenocarcinoma.

For T2 lung cancers, defined as tumor >3 cm but ≤5 cm, the 8th edition further divides these tumors into T2a for tumors ≤4 cm and T2b for tumors from 4 cm to 5 cm. Other characteristics of tumors that are classified as T2 include visceral pleural (PL1, 2) involvement, any atelectasis, pneumonitis, and involvement of main bronchus without touching the carina (Fig. 3) (2).

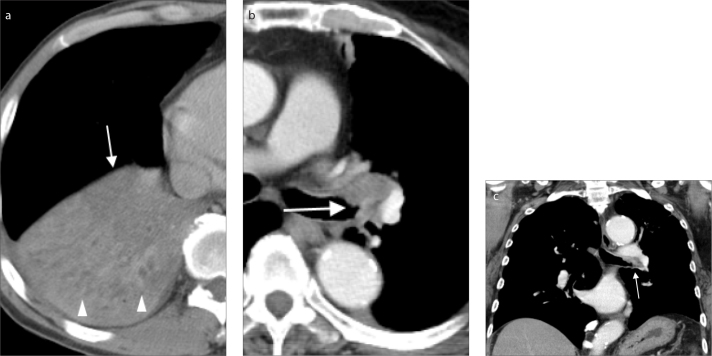

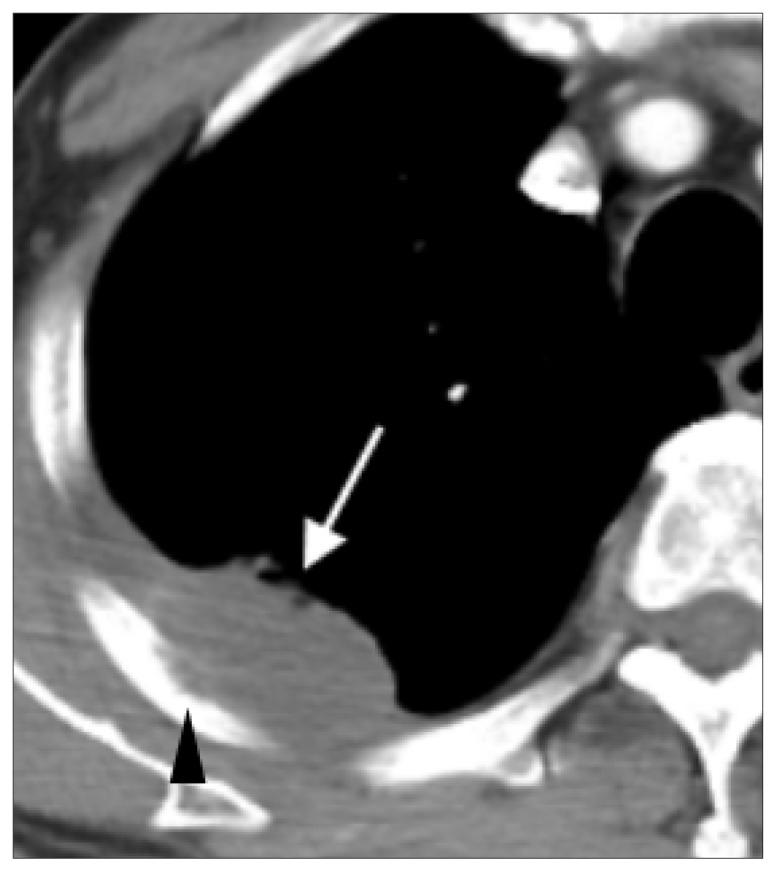

Figure 3. a–c.

Clinical image illustration of lung cancers that have features of T2. Squamous cell carcinoma of the right lower lobe of the lung (a) in a 57-year-old heavy smoker male. Chest CT with contrast showed the poorly enhanced, central tumor (a, arrow) measuring 4.4 cm with distal partial atelectasis/pneumonitis (arrowheads) of the right lower lobe of the lung. The stage is T2b in the 8th edition of lung cancer staging. A case of endobronchial lung cancer of the left upper lobe of the lung (b, c), involving the left main bronchus and left upper lobar bronchus with a maximum diameter of 2.7 cm (arrows). The involvement of main bronchus without touching the carina gives the cancer stage iT2a in the 8th edition of lung cancer staging.

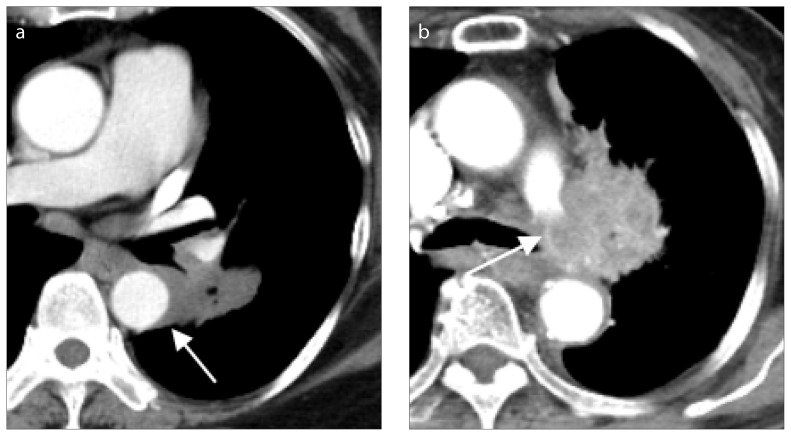

T3 lung tumors are tumors >5 cm and up to 7 cm or tumors involving parietal pleura (PL3), chest wall, phrenic nerve, parietal pericardium, or separate nodules in the same lobe as the primary tumor (Fig. 4) (5, 8).

Figure 4.

A case of lung cancer (arrow) with chest wall invasion in a 65-year-old male. Chest CT showed characteristics of chest wall invasion, including destruction of the right 4th rib (arrowhead), a tumor and pleural contact length of more than 3 cm, an obtuse angle between tumor and chest wall and associated pleural thickening.

For the T4 category, the 8th edition indicates that tumors >7 cm, tumors involving the diaphragm, recurrent laryngeal nerve, great vessels, mediastinal fat or other mediastinal structures, carina, visceral pericardium, vertebral body or separate nodules in the same lung but different lobes as the primary tumor, have the worst prognosis of all T descriptors (Fig. 5) (2, 8).

Figure 5. a, b.

Lung cancer with major vessel invasions. Lung cancer at superior segment of the left lower lobe (a, arrow), with maximum tumor diameter of 4 cm, in a 71-year-old female with pathology from endobronchial ultrasound biopsy proving non-small cell carcinoma, favoring adenocarcinoma. Lung CT showed tumor invasion of descending aorta with contact length more than one fourth (90°) of the circumference of descending aorta, and thus increased the T classification to T4, according to the 8th edition of lung cancer staging. Chest CT (b) showing lung cancer (arrow), with maximum diameter of 4.9 cm, in an 83-year-old female with tumor invasion to the left pulmonary artery.

The N descriptor

The N descriptor classification of the 7th edition remained the same for the 8th edition as studies found the classification was clearly separated by prognosis (9). The metastatic nodal classification is based on structural location of involved lymph nodes instead of the number of metastatic nodes that is often used in other cancer staging.

The N descriptors are classified into four main categories based on the location of the metastatic nodes (Table 2). The standard for identifying abnormal lymph node stay as enlarged lymph nodes that were more than 1 cm in short axis on CT or MRI scans in patients with non-small cell lung cancer (10, 11). Other considerations to identify metastatic lymph nodes include abnormal shape, attenuation, and inner necrosis (12). If there is no metastatic lymph node found on image, it is classified as N0. Metastatic lymph nodes involving ipsilateral peripheral, hilar or intrapulmonary nodes, are classified as N1. Ipsilateral mediastinal metastatic adenopathy, including upper, aortico-pulmonary and lower mediastinum, and subcarinal nodes, is considered as N2. Involvement of ipsilateral or contralateral supraclavicular/scalene lymph node or contralateral mediastinal, hilar, interlobar, or peripheral nodes is categorized as N3 (9).

Table 2.

N classification for appearance on chest CT for TNM 8th edition

| N classification | N component on CT |

|---|---|

| N0 | No lymph node metastasis |

| N1 | Ipsilateral peripheral, intrapulmonary or hilar nodes metastasis |

| N2 | Ipsilateral mediastinal (upper, aortico-pulmonary, lower), subcarinal nodes metastasis |

| N3 | Ipsilateral or contralateral supraclavicular/scalene lymph node or contralateral mediastinal, hilar/interlobar, or peripheral nodes metastasis |

It is interesting to note that 59% of the data of the 8th edition for the cN component was collected from Japan, which used the “Naruke-Japanese map” to determine nodal status (9, 13). Another commonly used nodal map was the Mountain-Dresler modification of the American Thoracic Society (MDATS) by countries other than Japan. The Naruke-Japanese map has slightly different anatomical definition of N1 and N2 border of lymph node regions than MDATS map. The Naruke-Japanese map classifies node involvement of subcarinal space as N1, while MDATS classifies it as N2 (9). This difference may have influenced the accuracy of prognosis that was used to assess the nodal classification in the 8th edition with no possible adjustments to correct this inconsistency. Thus, it is suggested to follow the unified international lymph node map (IASLC map) for future categorization of nodal involvements and avoid such discrepancies in forthcoming researches (14).

The M descriptor

The prognosis of the previous 7th edition M descriptor categorization was analyzed, and no significant difference was found for M1a intrathoracic metastasis descriptors. However, for extrathoracic metastasis, classified as M1b in the 7th edition, there seemed to be a significantly superior prognosis for those with a single metastasis in a single organ than those with multiple metastatic lesions in one organ or multiple metastases in multiple organs. Thus, the 8th edition further separates extrathoracic metastasis into M1b and M1c based on the two groups above (14).

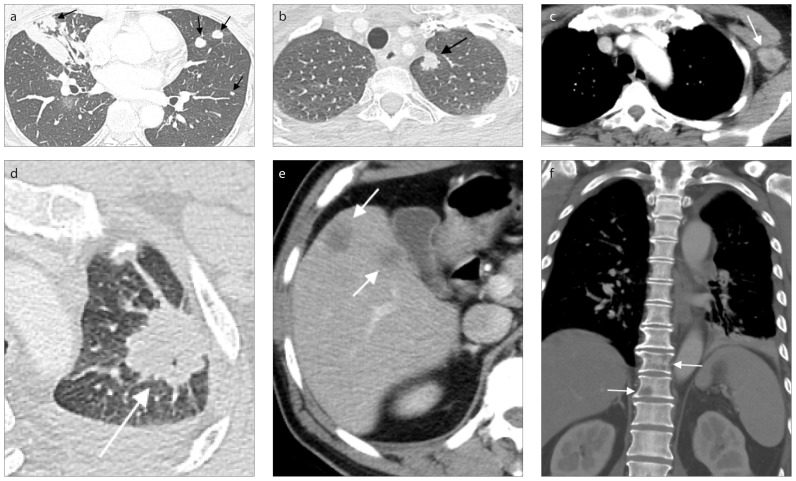

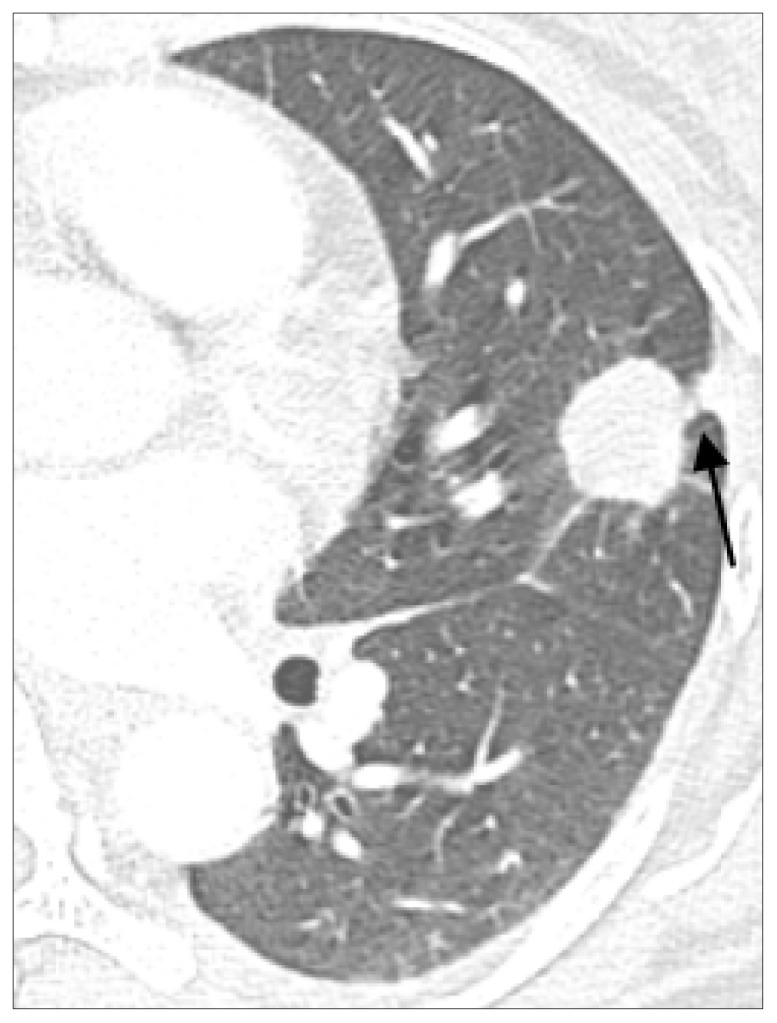

Due to the above reasons, in the 8th edition, intrathoracic metastasis with features including contralateral pulmonary tumor nodules, pleural and pericardial metastatic lesions, is kept as M1a (Fig. 6a). Extrathoracic metastasis is further divided into M1b and M1c. M1b consists of single extrathoracic metastatic lesion in a single organ (Fig. 6b, 6c). Conversely, multiple extrathoracic metastases are considered M1c due to significantly poor prognosis (Table 3, Fig. 6d–6f) (5, 15).

Figure 6. a–f.

CT scans showing three classifications of M descriptors. Chest CT image (a) of a 51-year-old female with a mass having maximum diameter of 4.2 cm and multiple pulmonary nodules in bilateral lungs (arrows), suspected bilateral lung to lung metastasis. Biopsy pathology favored primary lung adenocarcinoma. This case was staged M1a in image staging, with intrapulmonary metastasis. Contrast-enhanced chest CT images (b, c) of a 54 year-old female with lung tumor at left upper lobe of lung and distal metastasis to a nonregional lymph node. Lung window (b) showing the 1.3 cm solid tumor nodule with spiculated margin in the apicoposterior segment of left upper lobe of lung (arrow). Soft tissue window (c) illustrating the extrathoracic lymph node metastasis at left axillary region (arrow). Since no other distant metastasis is detected, this case should be staged as M1b, a single extrathoracic metastasis in a single organ. A case of M1c classification (d–f): multiple extrathoracic metastatic lesions at multiple sites of a 61-year-old male with lung cancer in the apicoposterior segment of left upper lobe of lung with a diameter of 3.3 cm (d, arrow). Soft tissue window (e) showing poorly enhanced nodules (arrows) in segment VII, VIII and V of liver, suspected metastatic lesions. Bone metastatic osteolytic lesions were noted in T10 and T11 vertebrae (f, arrows).

Table 3.

M classification for appearance on chest CT for TNM 8th edition

| M classification | M component on CT | |

|---|---|---|

| M0 | No distal metastasis | |

|

| ||

| M1 | M1a | Intrathoracic metastasis |

| Pleural effusion | ||

| Pericardial effusion | ||

| Contralateral lung nodules/pleural nodules | ||

| M1b | Single extrathoracic metastasis in a single organ | |

| M1c | Multiple extrathoracic metastasis | |

Overall stage groups

Due to the changes of the T and M descriptors, modifications of the existing stage groups and construction of new stage groups have been created for the 8th edition. Stage IA is divided into IA1, IA2, and IA3 to accommodate T1a, T1b, and T1c, when associated with categories N0 and M0, respectively (8, 16). For N0M0 tumors with T2a and T2b categories, they are now classified into stages IB and IIA correspondingly. All T1-2N1M0 tumors, along with T3N0M0, are now added to stage IIB category (5). For T1-2N2M0 tumors and other more locally advanced tumors without metastasis, including T3-4N1M0, stage IIIA is considered. Comparably, T1-2N3M0 tumors and T3-4N2M0 tumors are classified as stage IIIB. A new stage group, IIIC, is given for the most locally advanced lesions, T3 and T4, associated with N3 disease but without metastatic lesions, as they have similar prognoses with IVA tumors (17). Lastly, stage IV, representing advanced disease with metastasis, is now divided into group IVA and IVB based on the location and extent of metastasis. Lung tumors with M descriptor of M1a or M1b are classified as stage IVA, regardless of their T or N classification. Cases with multiple distant metastasis, classified as M1c, are now staged as IVB (16). The above changes in staging are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Overall stage group of lung cancer in TNM 8th edition

| N0 | N1 | N2 | N3 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M0 | Tis | 0 | |||

| T1mi | IA1 | ||||

| T1a | IA1 | IIB | IIIA | IIIB | |

| T1b | IA2 | IIB | IIIA | IIIB | |

| T1c | IA3 | IIB | IIIA | IIIB | |

| T2a | IB | IIB | IIIA | IIIB | |

| T2b | IIA | IIB | IIIA | IIIB | |

| T3 | IIB | IIIA | IIIB | IIIC | |

| T4 | IIIA | IIIA | IIIB | IIIC | |

|

| |||||

| M1a | Tx | IVA | IVA | IVA | IVA |

|

| |||||

| M1b | Tx | IVA | IVA | IVA | IVA |

|

| |||||

| M1c | Tx | IVB | IVB | IVB | IVB |

Potential pitfalls and limitations in interpretation of imaging staging of lung cancer

Even though the 8th edition of the TNM lung staging system provides us with more precise classification based on prognostic analysis of each TNM descriptor, there are still certain imaging interpretations that have not yet been clarified in terms of clinical staging.

Lymphangitis carcinomatosis

One common finding when assessing lung cancer on CT scans is lymphangitis carcinomatosis, a descriptor not included in neither the 7th TNM staging system nor the 8th edition. Key characteristics of lymphangitis carcinomatosis on CT include various sized nodular or smooth thickening of interlobular septum or bronchovascular bundles (Fig. 7). Singh et al. (19) had brought this issue to the attention of the editors of IASLC Lung Cancer Staging Project in 2015. The editors suggested to classify lymphangitis carcinomatosis as an independent descriptor, cLy, with grading into 4 categories based on anatomical extents. However, the prognostic implications of lymphangitis were difficult to conclude due to small sample size and insignificant difference in one-year prognosis of different classification of lymphangitis carcinomatosis (20). Thus, this issue remains unaddressed in the 8th edition.

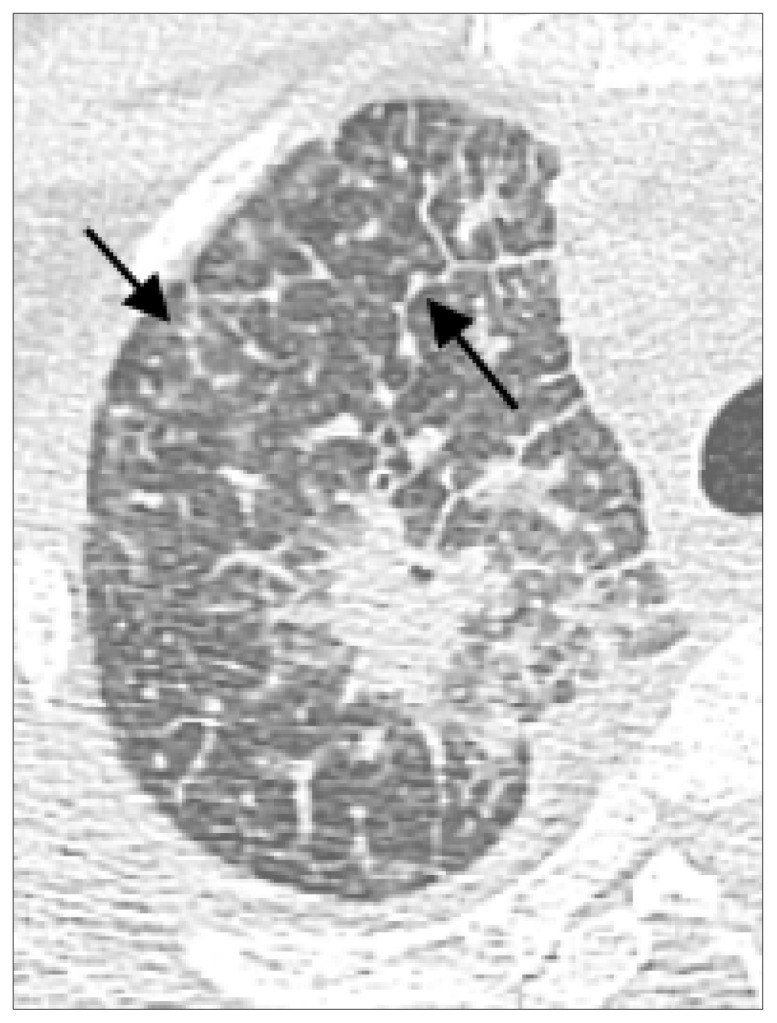

Figure 7.

CT scan of lymphangitis carcinomatosis. This 62-year-old male is diagnosed with adenocarcinoma of right upper lung. CT scan shows a spiculated mass in apical segment of right upper lobe of lung with a maximum dimension of 3.8 cm and extensive nodular septal thickenings (lymphangitis carcinomatosus, arrows).

Pleural invasion

Pleural invasion depending on invasion depth, PL1, PL2, PL3, is an important prognostic factor in the 8th edition of TNM staging, but this invasion is defined by pathologic examination. PL1 indicates tumor invasion of the elastic layer of visceral pleura without reaching the visceral pleural surface; PL2 defines the tumor invasion of the visceral pleural surface; and PL3 specifies tumor invasion of the parietal pleura or chest wall. While PL1 and PL2, limited to involvement of visceral pleura, are classified as T2, the presence of parietal pleural tumor invasion or chest wall invasion, PL3, will upstage the T category to T3.

There are still no absolute criteria to identify pleural invasion or further differentiate visceral or parietal pleural invasion at clinical staging, particularly from CT imaging. The most accurate CT finding for chest wall invasion is the destruction of bone (21). Conventional radiologic criteria for chest wall or parietal pleural invasion on CT include a tumor and pleural contact length of >3 cm, an obtuse angle between tumor and chest wall, and associated pleural thickening. The combination of two or three conventional CT criteria, had sensitivity of 46%–87% and specificity of 59%–91% depending on the radiologist’s experience (21–23). Another CT feature of pleural invasion with accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity of 79%, 82%, and 76%, respectively, is pleural puckering, which is defined as the localized thickening of pleura that is indrawn toward the tumor (24). Ebara et al. (25) proposed that tumor size <8.2 mm or with an interface length <4.1 mm may be an indicator that there is no pleural tumor invasion. They also suggested CT pattern of skirt-like appearance, which is the indrawn pleural thickening toward tumor associated with wrinkling of the indrawn pleura, was an identifier of high risk of pleural invasion with an accuracy of 77% (25). Imai et al. (22) later suggested a better tool to identify parietal pleural invasion on CT: the arch distance-to- maximum tumor diameter ratios >0.9 provided a greater accuracy of pleural invasion exceeding 90%, with sensitivity and specificity of 89.7% and 96.0%, respectively (22).

However, CT scan is still a limited tool in differentiating PL1 and PL2 from PL3. Some researchers had proposed nodule abutment or pleural tag to be indicators of visceral pleural invasion. Hsu et al. (26) classified pleural tags into three different categories, with type 1 as one or more linear pleural tags, type 2 as one or more linear pleural tags with soft-tissue component at pleural end, and type 3 as one or more soft-tissue cord-like pleural tags on the mediastinal window. The authors proposed that the presence of type 2 pleural tags in lung cancer that does not abut the pleura may predict visceral invasion with an accuracy of 71%, sensitivity of 36.4%, and specificity of 92.8% (26). However, for ground-glass opacity <3 cm, Zhao et al. found nodule abutment or pleural tag unreliable at predicting visceral pleural invasion. Larger tumors were thought to be at higher risk of visceral pleural invasion. However, for adenocarcinoma representing as ground-glass nodules, visceral pleural invasion does not correlate with worse prognosis (27). For T1-sized part-solid ground-glass nodules, CT features of pleural thickening, pleural contact with tumor size >2 cm or part-solid proportion larger than 50% are considered significant indicators of visceral pleural invasion (27, 28). (Fig. 8)

Figure 8.

Image illustration that likely present pleural invasion in lung cancer. Chest CT showing 2.3 cm adenocarcinoma of left upper lung with type 2 pleural tags, defined as one or more linear pleural tags with soft tissue component at the pleural end, in a 41-year-old female with pathology showing invasion to the chest wall (arrow).

Some may argue the use of MRI to further assess parietal pleural invasion because MRI theoretically has better soft tissue contrast and determination of fat-stripe invasion (29). However, conventional MRI and CT seem to have similar accuracy in detecting chest wall invasion (30, 31). Some studies suggested using particular methods to improve detection of chest wall invasion by MRI. Respiratory dynamic MRI study performed by Akata (32) was found to have a sensitivity of 100% and a specificity of 82.9% to assess chest wall invasion. Moreover, study by Kodalli et al. (33) found movement of 1 cm or 1/3 of the vertebral height of the tumor in respiratory dynamic MRI was enough to determine parietal pleural invasion in middle and lower segments of lower lungs. However, due to the time consuming, expensive, and poor spatial resolution nature of MRI, CT may still be a better conventional modality for assessing lung cancer.

Other considerations

Tumors with features of T2, including involvement of main bronchus without touching the carina, invasion of visceral pleura (PL1 or PL2), and association with atelectasis or obstructive pneumonitis, are classified as T2 if ≤5 cm. These tumors are further divided into T2a and T2b based on size. T2a for tumors with these features if ≤4 cm, even if they are smaller than 3 cm (8).

In addition, uniform consensus had been reached for other situations that were not covered in previous editions of TNM classification. Pancoast tumor is classified as T3, but will be upstaged to T4 if tumor invades vertebral body or spinal canal, subclavian vessels, or superior portion, C8 or above, of brachial plexus. Tumor that extends across the fissure directly into an adjacent lobe is classified as T2a. Isolated tumor nodules involving ipsilateral parietal or visceral pleura are assigned to M1a. However, discontinuous single tumor nodule will be upstaged to M1b if its location is beyond the parietal pleura, such as in the chest wall or in the diaphragm, and M1c if tumors are multiple (5).

The IASLC recommends assessing multiple lung lesions in a multidisciplinary manner. Four individual disease patterns of lung cancer with multiple pulmonary sites of involvement were suggested based on imaging features and pathologic characteristics. The patterns of disease were grouped into lung cancers with separate tumor nodules, multiple primary lung cancers, multiple ground-glass/lepidic lesions, and diffuse pneumonic-type lung adenocarcinoma (34). For separate tumor nodules, in both TNM-7 and TNM-8, the presence of pulmonary tumor nodules with the same histology type is classified with a single stage group on the basis of their location relative to the primary malignancy. This means T3 for nodules found in the same lobe as the primary tumor, T4 for nodules in different lobe but same lung of the primary tumor, and M1a if nodule is found in contralateral lung. However, a separate T, N, and M stage should be provided for each tumor with a different histology and should be considered as multiple primary cancers. Aside from the histologic evidence, other factors that radiologists may take into consideration in differentiating metastatic nodules and other primary tumors include comparison with previous imaging, similarity of radiographic appearance, and presence or absence of other metastatic lesions (5).

As mentioned previously, lung cancer presented as subsolid nodules or pure ground-glass nodules on CT are associated with adenocarcinomas with prominent lepidic components. These multiple lesions have a superior prognosis than solid lung tumors (34). A specific T classification is recommended for multiple ground-glass nodules/lepidic lesions with absence of nodal involvement or metastasis (35). The T descriptor should present the characteristic of the dominant lesion, determined by the largest diameter of the solid component, with the total number of ground-glass lesions in parentheses, regardless of the location of the rest of the lesions. For example, a patient with four ground-glass nodules, with three in the same lobe, one in different lung, and the largest lesion measuring 1.2 cm, will be staged as T1b(4) or simply, T1b(m) for multiple (5, 34).

The last category of lung cancer with multiple pulmonary involvement is the pneumonic type of adenocarcinoma, which refers to tumors with imaging features of pneumonic infiltrates: mixed patchy areas of ground-glass opacity and consolidation without bronchial obstruction (35). This pattern of tumor shows an indistinctive margin and may involve a particular region or appear diffusely throughout the lungs. Histologically, most of the pneumonic type adenocarcinoma yield invasive mucinous adenocarcinomas (34). If the tumor is confined to a single region with a single focus, the general rule for TNM classification is used. However, if multiple foci are found, then the classification is based on the location of involved areas: T3 for involving a single lobe, T4 if involving the other ipsilateral lobes, and M1a if both lungs are involved. When both lungs are involved, the T classification is based on the most advanced tumor size. However, if the tumor size is difficult to measure, T4 should be assigned if the tumor evidently involves an adjacent lobe. The N and M categories should be applied to all pulmonary sites collectively (5, 34, 35).

Assessing node metastasis

Even though the N classification has not changed from the 7th edition, there is an important limitation of the new database as mentioned previously in the article. More than half of the data analyzed to form the 8th edition for the cN component were collected from Japan using the Naruke-Japanese map, while the majority of the rest were assessed with the Mountain-Dresler modification of the American Thoracic Society. These two nodal maps had discrepant definitions of subcarinal space nodes: Naruke map defined them as station 10 (N1) while MDATS map considered them as station 7 (N2) (9). Unification of lymph node map categorization should be pursued in the future.

In addition to the nodal map discrepancy, there are also some features not addressed in the new TNM staging system. For instance, features associated with poor prognosis such as irregular lymph node margins or rare involvement of lymph node groups in the axillary, subpectoral, internal mammary, diaphragmatic, and abdominal regions, are not included in the N classification of the 8th TNM system (17). Even though some argued the definition of metastasis is the nonlymphatic spread of malignancy, the 8th edition considers lymph nodes not included in the N descriptors as M1 metastasis (8, 9, 14, 17).

The potential prognostic impact of the number of involved lymph node stations and the presence/absence of skip metastases should also be taken into consideration as the N descriptor of 8th edition is based on anatomical location rather than the number of invaded nodes. Wei et al. (36) proposed that the number of metastasis lymph nodes, nN category, was a superior prognostic factor than the anatomic location-based lymph node involvement, pN. Study had also shown a better prognosis for patients with skip metastasis of pN2 disease involving a single lymph node station without invading the hilar lymph nodes than patients with pN1 disease at multiple stations (9). The new IASLC database and classification does not include these potential impacts of N classification, and this issue may be further explored.

Conclusion

The new 8th edition of TNM staging system by IASLC is revised based on significant prognostic differences investigated from 1999 to 2010 in the lung cancer database. Major modifications to the T classification include T size classification based on 1 cm increment, reclassification of diaphragm invasion, and merging specific T descriptors, such as endobronchial tumor and atelectasis/pneumonitis, into the same category. New classification concept of adenocarcinoma in situ and minimally invasive adenocarcinoma for pure and part-solid ground-glass nodules was introduced. M classification is further separated based on the number and sites of extrathoracic metastases. Agreements are also reached for other debating situations not covered in previous edition of staging system, such as the classification of pancoast tumor based on its invasion depth and staging tumors that extend directly across the fissure as T2a. New stage groups have been created to accommodate the new descriptor categories. Even though the 8th edition of the TNM lung staging system offers us with more precise classification based on prognostic analysis of each TNM descriptor, there are still some potential interpretation pitfalls and clinical situations that have not yet been clarified in terms of imaging staging. Issues such as lymphangitis carcinomatosis, imaging limitation and assessment of pleural invasion, considerations of special characteristics, lung cancer with multiple pulmonary involvements, and lymph node assessment may raise questions for radiologists during imaging staging.

It is important for radiologists to understand the major changes introduced in the TNM 8th edition and to classify lung cancer using consistent standards for future analysis of the new TNM system.

Main points.

The 8th edition of TNM lung cancer staging modified the T classification based on 1 cm increment of tumor size, and other reclassification of certain features, including downstage of T descriptor of endobronchial tumor disregarding its distance from carina (T2), merging total and partial atelectasis/pneumonitis into the same T category (T2), and upstage of diaphragmatic invasion to T4.

Special considerations for lung cancer with multiple sites of pulmonary disease are categorized into 4 main disease patterns: 1) lung cancers with separate tumor nodules, 2) multiple primary lung cancers, 3) multiple ground-glass/lepidic lesions, and 4) diffuse pneumonic-type lung adenocarcinoma, each with recommended stage classification suggested by IASLC.

The M classification is further divided into M1a, M1b, and M1c, based on location and number of metastasis: M1a as intrathoracic metastasis with features including contralateral pulmonary tumor nodules, pleural and pericardial metastatic lesions, M1b for single extrathoracic metastatic lesion in a single organ, and M1c consisting of multiple extrathoracic metastases.

The 8th edition of TNM cancer staging still failed to address lymphangitis carcinomatosis as a descriptor, but the editors of IASLC Lung Cancer Staging Project suggested to classify lymphangitis carcinomatosis as an independent descriptor, cLy.

Limitations of CT to distinguish pleural invasion is still a concern. Features including a tumor and pleural contact length of >3 cm, an obtuse angle between tumor and chest wall, associated pleural thickening, and arch distance-to-maximum tumor diameter ratios >0.9, can be used to assess pleural invasion on chest CT.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest disclosure

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer Statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rami-Porta R, Bolejack V, Crowley J, et al. The IASLC lung cancer staging project: proposals for the revisions of the T descriptors in the forthcoming eighth edition of the TNM classification for lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2015;10:990–1003. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0000000000000559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brierley J, Gospodarowicz MK, Wittekind C. TNM classification of malignant tumours. Eighth ed. Oxford, UK ; Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Travis WD, Asamura H, Bankier AA, et al. The IASLC lung cancer staging project: proposals for coding T categories for subsolid nodules and assessment of tumor size in part-solid tumors in the forthcoming eighth edition of the TNM classification of lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2016;11:1204–1223. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2016.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rami-Porta R, Asamura H, Travis WD, Rusch VW. Lung cancer - major changes in the American Joint Committee on Cancer eighth edition cancer staging manual. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67:138–155. doi: 10.3322/caac.21390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Detterbeck FC, Boff DJ, Kim AW, Tanoue LT. The eighth edition lung cancer stage classification. Chest. 2017;151:193–203. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2016.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Travis WD, Brambilla E, Rami-Porta R, et al. Visceral pleural invasion: pathologic criteria and use of elastic stains: proposal for the 7th edition of the TNM classification for lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2008;3:1384–1390. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31818e0d9f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Amin MB. American Joint Committee on Cancer and American Cancer Society AJCC cancer staging manual. 8th Ed. Chicago IL: American Joint Committee on Cancer, Springer; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Asamura H, Chansky K, Crowley J, et al. The international association for the study of lung cancer lung cancer staging project: proposals for the revision of the N descriptors in the forthcoming 8th edition of the TNM classification for lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2015;10:1675–1684. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0000000000000678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kay FU, Kandathil A, Batra K, Saboo SS, Abbara S, Rajiah P. Revisions to the Tumor, Node, Metastasis staging of lung cancer (8th edition): Rationale, radiologic findings and clinical implications. World J Radiol. 2017;9:269–279. doi: 10.4329/wjr.v9.i6.269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Glazer GM, Gross BH, Quint LE, Francis IR, Bookstein FL, Orringer MB. Normal mediastinal lymph nodes: number and size according to American Thoracic Society mapping. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1985;144:261–265. doi: 10.2214/ajr.144.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Walker CM, Chung JH, Abbott GF, et al. Mediastinal lymph node staging: from noninvasive to surgical. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012;199:W54–64. doi: 10.2214/AJR.11.7446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Naruke T, Suemasu K, Ishikawa S. Lymph node mapping and curability at various levels of metastasis in resected lung cancer. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1978;76:832–839. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.El-Sherief AH, Lau CT, Wu CC, Drake RL, Abbott GF, Rice TW. International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer (IASLC) lymph node map: radiologic review with CT illustration. Radiographics. 2014;34:1680–1691. doi: 10.1148/rg.346130097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eberhardt WE, Mitchell A, Crowley J, et al. The IASLC lung cancer staging project: proposals for the revision of the M descriptors in the forthcoming eighth edition of the TNM classification of lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2015;10:1515–1522. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0000000000000673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goldstraw P, Chansky K, Crowley J, et al. The IASLC lung cancer staging project: proposals for revision of the TNM stage groupings in the forthcoming (eighth) edition of the TNM classification for lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2016;11:39–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2015.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carter BW, Godoy MC, Wu CC, Erasmus JJ, Truong MT. Current controversies in lung cancer staging. J Thorac Imaging. 2016;31:201–214. doi: 10.1097/RTI.0000000000000213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosado-de-Christenson M, Carter BW. Specialty imaging: thoracic neoplasms. 1st ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2015. p. 500. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Singh N, Baldi M, Behera D. Inclusion of lymphangitis as a descriptor in the new TNM staging of lung cancer: filling up the blank spaces. J Thorac Oncol. 2015;10:e119. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0000000000000682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rami-Porta R, Bolejack V. Reply to “Inclusion of lymphangitis as a descriptor in the new TNM staging of lung cancer: filling up the blank spaces”. J Thorac Oncol. 2015;10:e119–e120. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0000000000000683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Glazer HS, Duncan-Meyer J, Aronberg DJ, Moragn JF, Levitt RG, Sagel SS. Pleural and chest wall invasion in bronchogenic carcinoma: CT evaluation. Radiology. 1985;157:191–194. doi: 10.1148/radiology.157.1.4034965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Imai K, Minamiya Y, Ishiyama K, et al. Use of CT to evaluate pleural invasion in non-small cell lung cancer: measurement of the ratio of the interface between tumor and neighboring structures to maximum tumor diameter. Radiology. 2013;267:619–626. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12120864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tanaka T, Shinya T, Sato S, et al. Predicting pleural invasion using HRCT and 18F-FDG PET/CT in lung adenocarcinoma with pleural contact. Ann Nucl Med. 2015;29:757–765. doi: 10.1007/s12149-015-0999-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuriyama K, Tateyishi R, Kumatani T, et al. Pleural invasion by peripheral bronchogenic carcinoma: assessment with three-dimensional helical CT. Radiology. 1994;191:365–369. doi: 10.1148/radiology.191.2.8153307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ebara K, Takashima S, Jiang B, et al. Pleural invasion by peripheral lung cancer. Acad Radiol. 2015;22:310–319. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2014.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hsu JS, Han IT, Tsai TH, et al. Pleural tags on CT scans to predict visceral pleural invasion of non-small cell lung cancer that does not abut the pleura. Radiology. 2016;279:590–596. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2015151120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhao LL, Xie HK, Zhang LP, et al. Visceral pleural invasion in lung adenocarcinoma ≤3 cm with ground-glass opacity: a clinical, pathological and radiological study. J Thorac Dis. 2016;8:1788–1797. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2016.05.90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ahn SY, Park CM, Jeon YK, et al. Predictive CT features of visceral pleural invasion by T1-sized peripheral pulmonary adenocarcinomas manifesting as subsolid nodules. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2017;209:561–566. doi: 10.2214/AJR.16.17280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hollings N, Shaw P. Diagnostic imaging of lung cancer. Eur Respir J. 2002;19:722–742. doi: 10.1183/09031936.02.00280002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Webb WR, Gatsonis C, Zerhouni EA, et al. CT and MR imaging in staging non-small cell bronchogenic carcinoma: report of the Radiologic Diagnostic Oncology Group. Radiology. 1991;178:705–713. doi: 10.1148/radiology.178.3.1847239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Musset D, Grenier P, Carette MF, et al. Primary lung cancer staging: prospective comparative study of MR imaging with CT. Radiology. 1986;160:607–611. doi: 10.1148/radiology.160.3.2426726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Akata S, Kajiwara N, Park J, et al. Evaluation of chest wall invasion by lung cancer using respiratory dynamic MRI. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol. 2008;52:36–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1673.2007.01908.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kodalli N, Erzen C, Yuksel M. Evaluation of parietal pleural invasion of lung cancers with breathhold inspiration and expiration MRI. Clin Imaging. 1999;23:227–235. doi: 10.1016/S0899-7071(99)00135-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Detterbeck FC, Marom M, Arenberg DA, et al. The IASLC lung cancer staging project: background data and proposals for the application of TNM staging rules to lung cancer presenting as multiple nodules with ground glass or lepidic features or a pneumonic type of involvement in the forthcoming eighth edition of the TNM classification. J Thorac Oncol. 2016;11:666–680. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2015.12.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Detterbeck FC, Nicholson AG, Franklin WA, et al. The IASLC lung cancer staging project: summary of proposals for revisions of the classification of lung cancers with multiple pulmonary sites of involvement in the forthcoming eighth edition of the TNM classification. J Thorac Oncol. 2016;11:639–650. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2015.12.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wei S, Asamura H, Kawachi R, Sakurai H, Watanebe S. Which is the better prognostic factor for resected non-small cell lung cancer: the number of metastatic lymph nodes or the currently used nodal stage classification? J Thorac Oncol. 2011;6:310–318. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181ff9b45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]