Abstract

Classic embryological studies have successfully applied genetics and cell biology principles to understand embryonic development. However, it remains unresolved how mechanics, as an integral part for shaping development, is involved in controlling tissue-scale cell fate patterning. Here we report a micropatterned human pluripotent stem (hPS) cell-based neuroectoderm developmental model, wherein pre-patterned geometrical confinement induces emergent patterning of neuroepithelial (NE) and neural plate border (NPB) cells, mimicking neuroectoderm regionalization during early neurulation. Our data support that in this hPS cell-based neuroectoderm patterning model, two tissue-scale morphogenetic signals, cell shape and cytoskeletal contractile force, instruct NE / NPB patterning via BMP-SMAD signaling. We further show that ectopic mechanical activation and exogenous BMP signaling modulation are sufficient to perturb NE / NPB patterning. This study provides a microengineered, hPS cell-based model to understand the biomechanical principles that guide neuroectoderm patterning, thereby useful for studying neural development and diseases.

One of the enduring mysteries of biology is tissue morphogenesis and patterning, where embryonic cells act in a coordinated fashion to shape the body plan of multicellular animals1–5. As a highly conserved developmental event crucial for the nervous system formation, neural induction, for example, leads to differentiation of the ectoderm into a patterned tissue, containing the neuroectoderm (neural plate, or NP) and the epidermal ectoderm separated by the neural plate border (NPB) (Fig. 1a)6,7. Classic embryological studies of neural induction have unraveled the importance of graded developmental signaling mediated by diffusible signals including bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs) (Fig. 1a)8–10. However, neural induction, like any tissue-scale morphogenetic event, occurs within the milieu of biophysical determinants including changes in shape, number, position, and force of cells7,11. Yet, it remains undetermined how these tissue-scale morphogenetic changes work in concert with classic developmental signaling events mediated by diffusible signals for proper cell fate patterning during neural induction.

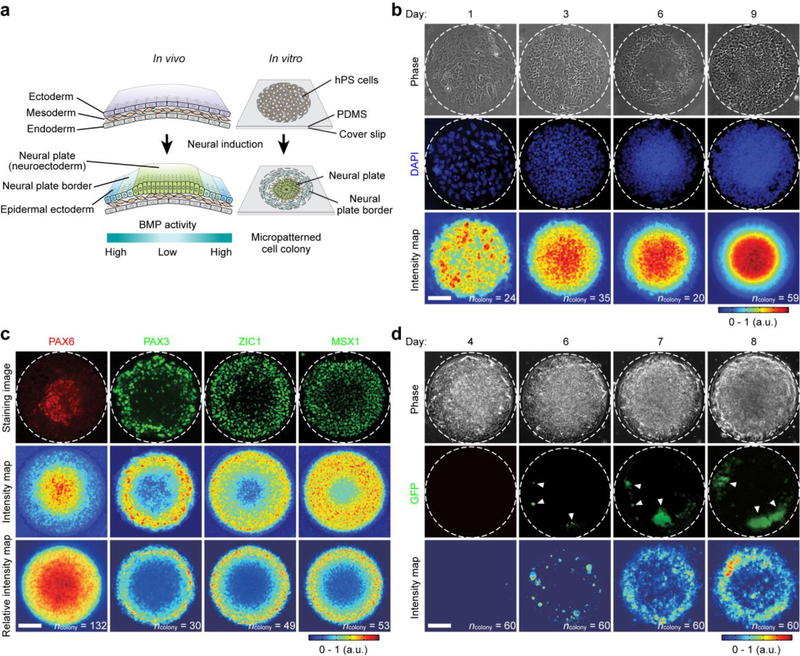

Figure 1.

Self-organized neuroectoderm patterning in circular hPS cell colonies. (a) Schematic of neural induction in vivo and in vitro. During neural induction in vivo, embryonic cells in the ectoderm form the neural plate (NP, or neuroectoderm). Embryonic cells at the neural plate border (NPB) separate the neuroectoderm from the epidermal ectoderm. Neural induction of circular hPS cell colonies leads to autonomously patterned neuroectoderm tissues, with NP cells at colony central region and NPB cells at colony periphery. (b) Representative phase contrast and fluorescence images showing cell morphology and nuclei (stained by DAPI), respectively, at different days. White dashed lines mark colony periphery. Experiments were repeated three times with similar results. Bottom average intensity maps show spatial distributions of DAPI intensity. Number of colonies analyzed were pooled from n = 3 independent experiments. Data were plotted as the mean. (c) Representative immunofluorescence micrographs and average intensity maps showing colonies at day 9 stained for neuroectoderm marker PAX6 and NPB markers PAX3, ZIC1 and MSX1. White dashed lines mark colony periphery. Experiments were repeated three times with similar results. Relative intensity maps were normalized to DAPI signals. Number of colonies analyzed were pooled from n = 3 independent experiments. Data were plotted as the mean. (d) Representative phase contrast and fluorescence images and average intensity maps from live cell assays using SOX10:EGFP hES cells. White dashed lines mark colony periphery. White arrowheads mark GFP+ cells at colony border on day 6. Experiments were repeated three times with similar results. Number of colonies analyzed were pooled from n = 3 independent experiments. Data were plotted as the mean. Scale bars in b-d, 100 μm.

Human pluripotent stem (hPS) cells, which reside in a developmental state similar to pluripotent epiblasts12,13, have been successfully utilized for the development of self-organized organoid systems14–21. To date, however, no neural induction models exist that leverage hPS cells and their innate self-organizing properties to study neuroectoderm patterning. Here, we sought to develop micropatterned hPS cell colonies on two-dimensional substrates to model neural induction. Microcontact printing was utilized to generate vitronectin-coated, circular adhesive islands with a diameter of 400 μm on flat poly-dimethylsiloxane (PDMS) surfaces coated on glass coverslips (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. 1). H1 human embryonic stem (hES) cells were plated as single cells at 20,000 cells cm−2 on adhesive islands to establish micropatterned colonies with a defined circular shape and size. A differentiation medium supplemented with the dual SMAD inhibitors, SB 431542 (SB, TGF-β inhibitor; 10 μM) and LDN 193189 (LDN, BMP4 inhibitor; 500 nM), was applied for neural induction22 (Supplementary Fig. 1; see Methods). The β-catenin stabilizer CHIR 99021 (CHIR, 3 μM), a WNT activator, was also supplemented (Supplementary Fig. 1). CHIR promotes NPB cell specification under the neural induction condition established by the dual SMAD inhibitors23,24.

While cells distributed uniformly on adhesive islands 24 hr after initial cell plating, neural induction resulted in differentiating cells gradually accumulating in colony central area, leading to a significantly greater cell density at colony center than periphery (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. 1). Cell density was further analyzed based on DAPI fluorescence intensity. The full width at half maximum (FWHM) for spatial distributions of DAPI intensity decreased continuously from 336 μm at day 1 to 240 μm at day 9 (Supplementary Fig. 1). Confocal images further showed that micropatterned colonies at day 7 remained as a monolayer. Strikingly, quantitation of colony thickness and nucleus shape revealed that at this point, cells exhibited a gradual change of cell shape from a pseudostratified columnar phenotype with columnar nuclei at colony center to a cuboidal morphology with rounded nuclei at colony periphery (Supplementary Fig. 1), consistent with characteristic neuroectoderm thickening during neural induction in vivo6,11. Importantly, PAX6+ neuroepithelial (NE) cells, the neural progenitor in the NP, were found preferentially localized at colony central region on day 9, whereas PAX3+, ZIC1+ and MSX1+ NPB cells were concentrated at colony periphery, forming a concentric ring-shaped tissue sheet consistent with neuroectoderm patterning with proper regionalization of NE and NPB cells (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Fig. 1). Interestingly, the concentric zone of PAX3+ cells at colony periphery exhibited a smaller zone width, as characterized by FWHM for spatial distribution of PAX3 intensity (92 μm), compared with concentric zones of ZIC1+ (128 μm) and MSX1+ (175 μm) cells, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 1). This observation is consistent with in vivo findings that ZIC1+ cells also exist in the neurogenic placode region25. Immunostaining and immunoblotting of E-CADHERIN and N-CADHERIN at day 2 and day 7 further confirmed successful neural conversion (Supplementary Fig. 2). To confirm differentiation potentials of neuroectoderm tissues after neural induction, they were continuously cultured under a motor neuron (MN) differentiation medium26 or a neural crest (NC) differentiation medium23,24 (Supplementary Fig. 3). Importantly, only putative NE cells at colony central region differentiated into OLIG2+ MN progenitor cells, whereas only putative NPB cells at colony periphery differentiated into AP2α+ and SOX10+ NC cells (Supplementary Fig. 3).

We next sought to examine the effect of colony size on self-organized neuroectoderm patterning. To this end, circular adhesive islands with diameters of 300, 400, 500 and 800 μm were fabricated and compared. Neural induction resulted in the emergence of concentric, ring-shaped neuroectoderm tissues with proper regionalization of NE and NPB cells at day 9 for all colonies (Supplementary Fig. 4). Interestingly, the PAX6+ NE circular pattern size and the concentric zone width of PAX3+ NPB cells, as characterized by FWHM for spatial distributions of PAX6 and PAX3 intensities, respectively, appeared relatively constant for colony diameters between 300 – 500 μm (Supplementary Fig. 4). Notably, neural induction for colonies with a diameter of 800 μm led to marked cell accumulation at colony periphery on day 9, coinciding with a notable number of PAX3+, ZIC1+, and MSX1+ NPB cells at colony central region (Supplementary Fig. 4). The underlying mechanism(s) leading to this different cell fate distribution remains unclear, and likely involves secondary tissue morphogenesis18. We further examined neuroectoderm patterning in circular colonies of 400 μm in diameter under two other initial cell seeding density conditions (5,000 cells cm−2 and 30,000 cells cm−2). A seeding density of 5,000 cells cm−2 led to abnormal neuroectoderm regionalization. Even though a notable number of PAX6+ NE cells appeared at colony center, PAX3+, ZIC1+ and MSX1+ NPB cells were evident across entire colonies without distinct spatial patterning (Supplementary Fig. 5). Plating cells at 30,000 cells cm−2 led to development of multilayered cellular structures by day 9, even though PAX3+ NPB cells still appeared and formed a single peripheral layer enveloping colony top surface (Supplementary Fig. 5). Together, we identified micropatterned circular colonies of 300 – 500 μm in diameter and an initial cell seeding density of 20,000 cells cm−2 as the most suitable condition for in vitro modeling of neural induction (referred to henceforth as the ‘default neural induction’ condition). Emergent patterning of neuroectoderm tissues with proper autonomous regionalization of NE and NPB cells was also achieved using another hES cell line (H9) and a human induced pluripotent stem (hiPS) cell line (Supplementary Fig. 6).

We further conducted live-cell assays to examine dynamic neuroectoderm pattering using a SOX10-EGFP bacterial artificial chromosome hES cell reporter line (H9)23. SOX10 is a specifier gene for NC induction at the NPB in vertebrates27. Surprisingly, under the default neural induction condition, GFP+ cells emerged first at colony periphery on day 6 and continuously increased its number there through day 7 and day 8 (Fig. 1d). This observation was further corroborated by immunofluorescence analysis to examine initial appearances and spatial distributions of PAX6+ NE and PAX3+ NPB cells (Supplementary Fig. 7). Together, the time course of expression of NPB markers PAX3, ZIC1 and MSX1 and NC marker SOX10 in micropatterned hES cell colonies is consistent with mouse embryo development in vivo27–29.

To examine a possible role of cell sorting in neuroectoderm patterning, live-cell imaging was conducted for tracking cell migratory behaviors. Migration of cells, regardless whether located at colony central or peripheral regions, was very limited under the default neural induction condition, with an average radial displacement less than 20 μm between day 2 – 4 (Supplementary Fig. 8). Furthermore, cell migration could be simulated well using an unbiased random walk model (Supplementary Fig. 8; see Methods). Thus, cell sorting was unlikely responsible for emergent regional neuroectoderm patterning in micropatterned colonies. Together, our data support that autonomous regionalization of NE and NPB cells probably can be attributed to cell fate-determinant, position-dependent information perceived by differentiating cells that dictates bifurcation dynamics of NE and NPB lineage commitments.

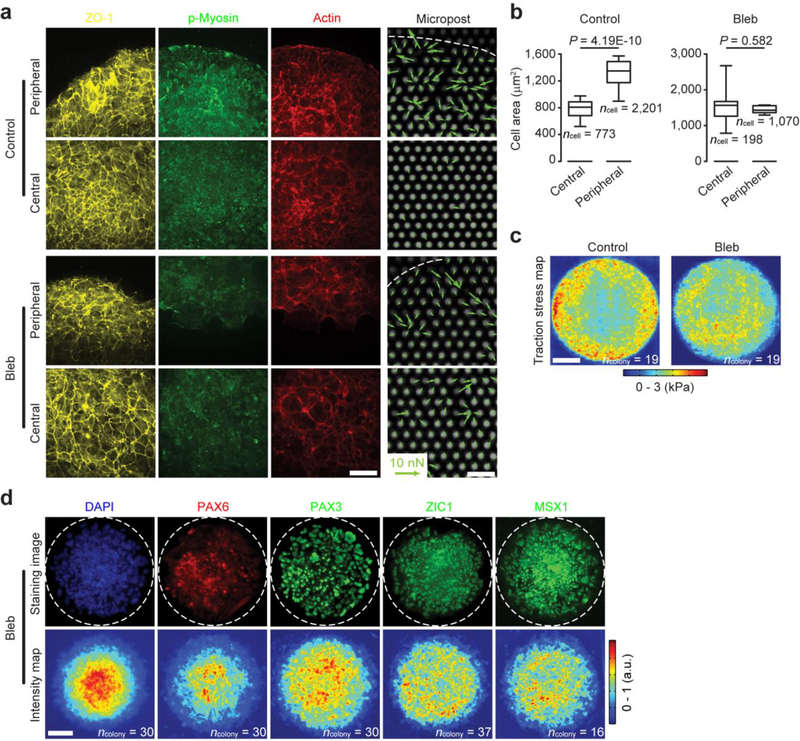

Gradual cell accumulation at colony center (Fig. 1b) suggests cell rearrangement and dynamic morphogenetic processes. Indeed, colonies stained for ZO-1 for visualization of cell-cell junctions revealed that at day 4, cells at colony periphery displayed a greater projected area than at central region (Supplementary Fig. 9, Supplementary Fig. 10, and Fig. 2a&b). Compared with those at colony center, cells at colony periphery also displayed greater intracellular cytoskeletal contractility, as revealed by stronger staining for phosphorylated myosin and greater traction stress quantitated using PDMS micropost force sensors30 (Fig. 2a&c and Supplementary Fig. 9; see Methods). Supplementing neural induction medium with blebbistatin (10 μM), which inhibits myosin motor activity and thus cytoskeletal contractility, effectively eliminated spatial differences in projected area or traction stress between colony peripheral and central regions at day 4 (Supplementary Fig. 10 and Fig. 2a–c). Of note, blebbistatin treatment did not result in notable cell toxicity (Supplementary Fig. 11). However, it decreased cell proliferation and thus effectively increased cell spreading area at colony central area (Supplementary Fig. 11). Importantly, even though NE and NBP cells still appeared at day 9 with blebbistatin treatment, proper neuroectoderm regionalization was severely impaired, with abundant PAX3+, ZIC1+ and MSX1+ NPB cells randomly distributed across entire colonies (Fig. 2d). Reducing cell seeding density under default neural induction condition to 5,000 cells cm−2 also caused more uniform spatial distributions of projected area and traction stress across entire colonies (Supplementary Fig. 10).

Figure 2.

Self-organization of morphogenetic factors controls neuroectoderm patterning. (a) Representative fluorescence images showing staining for ZO-1, phosphorylated myosin (p-myosin) and actin, as well as micropost sensors at colony peripheral and central regions at day 4. hPS cells were cultured in neural induction medium supplemented with either DMSO (control) or blebbistatin (Bleb; 10 μM). Circular colonies were divided into 2 concentric zones (“central” vs. “peripheral”) with equal widths. White dashed lines mark colony periphery. Traction force vectors were superimposed onto individual micropost force sensors. Experiments were repeated three times with similar results. Scale bars, 40 μm (fluorescence micrographs) and 10 μm (micropost images). (b) Box-and-whisker plots showing projected cell spreading area at day 4 under different conditions as indicated (box: 25 – 75%, bar-in-box: median, whiskers: 1% and 99%). Number of colonies analyzed were pooled from n = 3 independent experiments. P values were calculated using unpaired, two-sided Student’s t-tests. (c) Maps showing spatial distribution of traction stress quantitated using micropost force sensors at day 4 under culture conditions as indicated (see Methods). Number of colonies analyzed were pooled from n = 3 independent experiments. Data were plotted as the mean. Scale bar, 100 μm. (d) Representative immunofluorescence micrographs and average intensity maps showing colonies at day 9 stained for PAX6, PAX3, ZIC1 and MSX1. DAPI counterstained nuclei. White dashed lines mark colony periphery. Experiments were repeated three times with similar results. Number of colonies analyzed were pooled from n = 3 independent experiments. Data in intensity maps were plotted as the mean. Scale bar, 100 μm.

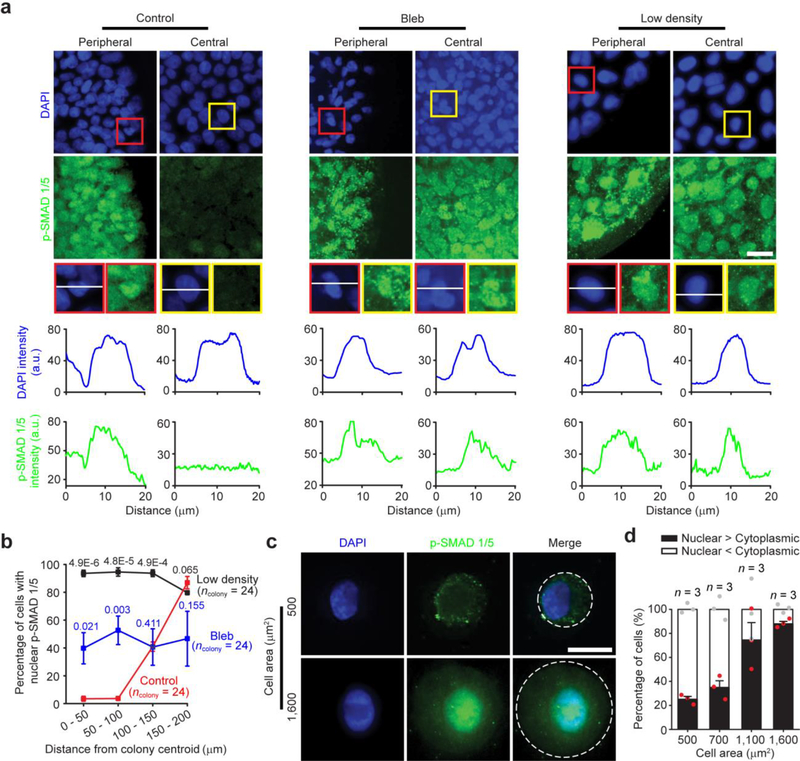

Our results in Fig. 2 suggested critical roles of morphogenetic cues in mediating neuroectoderm patterning with proper regionalization. Neural induction in vivo has been shown to be mediated through graded BMP signaling8–10,31. Specifically, a BMP signaling gradient provides positional information in the ectoderm, with high BMP activity promoting epidermal differentiation, low BMP for NP development, and intermediate BMP for NPB specification8–10,31 (Fig. 1a). Indeed, we observed strong correlations between spatial regulations of cell shape, cytoskeletal contractility and BMP activity at day 4. Most cells at colony periphery showed prominent nuclear staining of phosphorylated SMAD 1/5 (p-SMAD 1/5), a downstream target of BMP-SMAD signaling, whereas much fewer cells at colony central area were p-SMAD 1/5 nuclear positive (Fig. 3a&b). Interestingly, blebbistatin treatment or plating cells at 5,000 cells cm−2 rescued BMP activity at colony central area on day 4 (Fig. 3a&b), consistent with their effects on promoting NPB differentiation at colony central region. Replacing LDN in the default neural induction condition with NOGGIN (100 ng mL−1), a protein that antagonizes BMPs, or dorsomorphin (1 μM), which inhibits BMP receptors, led to similar results of graded SMAD transcriptional activation at day 4 and neuroectoderm regionalization at day 9 (Supplementary Fig. 12).

Figure 3.

Mechanically guided neuroectoderm patterning is mediated by BMP-SMAD signaling. (a) Representative immunofluorescence images showing colony central and peripheral zones at day 4 stained for phosphorylated SMAD 1/5 (p-SMAD 1/5). hPS cells were plated at either 20,000 cells cm−2 (control) or 5,000 cell cm−2 (low density) and were cultured in neural induction medium supplemented with either DMSO or blebbistatin (Bleb; 10 μM). Red and yellow rectangles highlight selected peripheral and central regions, respectively, where fluorescence intensities of DAPI and p-SMAD 1/5 were measured along white solid lines drawn across these selected areas. Scale bar, 40 μm. Experiments were repeated three times with similar results. (b) Percentage of cells with nuclear p-SMAD 1/5 as a function of distance from colony centroid. Based on distance of nuclei from colony centroid, cells were grouped into 4 concentric zones with equal widths as indicated. Number of colonies analyzed were pooled from n = 3 independent experiments. Data were plotted as the mean ± s.e.m. P values were calculated between Bleb vs. control and low density vs. control using unpaired, two-sided Student’s t-tests. (c) Representative immunofluorescence micrographs showing patterned circular single hPS cells with defined spreading areas (500 μm2 vs. 1,600 μm2) stained for p-SMAD 1/5. White dashed lines mark cell shape. Scale bar, 20 μm. Experiments were repeated three times with similar results. (d) Bar plot showing percentages of cells with dominant nuclear or cytoplasmic p-SMAD 1/5 as a function of cell spreading area. n = 3 independent experiments. Data were plotted as the mean ± s.e.m.

To specifically examine the functional roles of cell shape and cytoskeletal contractility in BMP activation, microcontact printing was applied to obtain patterned circular single hES cells with prescribed spreading areas (Supplementary Fig. 13 and Fig. 3c). Of note, cytoskeletal contractility of patterned single hES cells correlated positively with spreading area (Supplementary Fig. 13). Importantly, percentage of patterned single hES cells with dominant nuclear staining of p-SMAD 1/5 also increased with spreading area (Fig. 3c&d). Furthermore, qRT-PCR analysis revealed greater expression levels of BMP target genes MSX1, ID1, and ID3 in patterned single hES cells with greater spreading areas (Supplementary Fig. 13). Similar observations about BMP target genes were also obtained when seeding hES cells on vitronectin-coated flat PDMS surfaces at different plating densities to effectively modulate spreading area and cytoskeletal contractility (Supplementary Fig. 13).

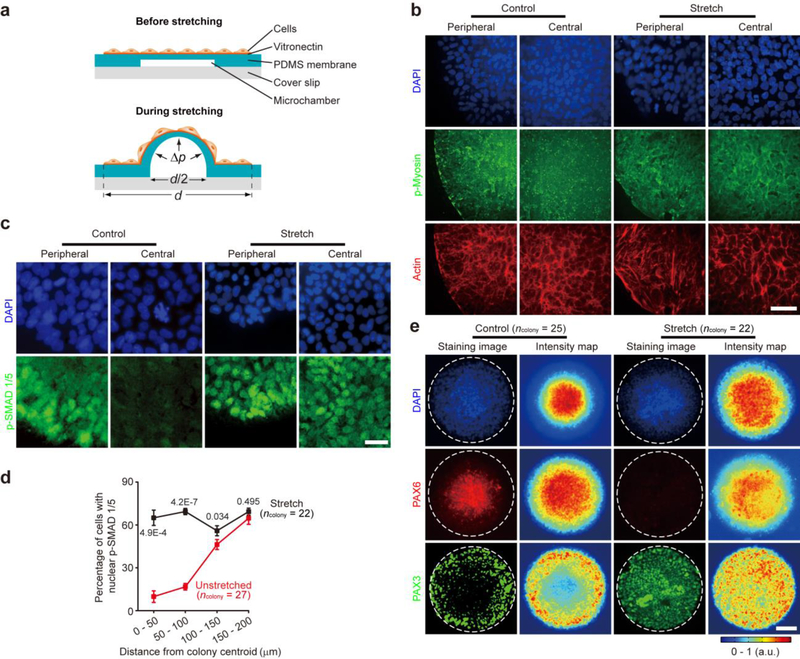

To further investigate the causal link between cell shape and mechanical force and neuroectoderm patterning, a custom designed microfluidic cell stretching device was developed and implemented for stretching central regions of micropatterned cell colonies32 (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Fig. 14). Continuous stretching with a square-wave pattern (pulse width of 2 hr and period of 4 hr) and a 100% stretch amplitude was applied starting from day 2 under the default neural induction condition (Supplementary Fig. 14). Indeed, mechanical stretching enhanced cytoskeletal contractility at colony central region, as reflected by stronger staining of phosphorylated myosin and actin filaments, as compared to unstretched controls (Fig. 4b). Furthermore, stretching of colony central area effectively rescued nuclear p-SMAD 1/5 and thus BMP activity at colony central region (Fig. 4c&d). By day 8, a significant number of PAX3+ NPB cells were evident at colony center, whereas NE differentiation was completely inhibited there (Fig. 4e). Together, these results unambiguously demonstrate that cell shape and mechanical force can directly activate BMP-SMAD signaling and thus repress NE but promote NPB differentiation.

Figure 4.

Mechanical force is sufficient for activating BMP-SMAD signaling and inducing neural plate border cell differentiation. (a) Schematic of a microfluidic device to apply stretching forces to central zones of micropatterned hPS cell colonies. (b) Representative fluorescence micrographs showing central and peripheral zones of unstretched (control) and stretched (stretch) micropatterned colonies at day 4 stained for phosphorylated myosin (p-myosin) and actin. DAPI counterstained nuclei. Scale bar, 40 μm. Experiments were repeated three times with similar results. (c) Representative immunofluorescence images showing central and peripheral zones of unstretched (control) and stretched (stretch) micropatterned colonies at day 4 stained for phosphorylated SMAD 1/5 (p-SMAD 1/5). DAPI counterstained nuclei. Scale bar, 40 μm. Experiments were repeated four times with similar results. (d) Percentage of cells with nuclear p-SMAD 1/5 as a function of distance from colony centroid under stretch and unstretched control conditions as indicated. Based on distance of nuclei from colony centroid, cells were grouped into 4 concentric zones with equal widths as indicated. Number of colonies analyzed were pooled from n = 4 independent experiments. Data were plotted as the mean ± s.e.m. P values were calculated between stretch and unstretched control conditions using unpaired, two-sided Student’s t-tests. (e) Representative immunofluorescence micrographs and average intensity maps showing unstretched (control) and stretched (stretch) colonies at day 8 stained for PAX6 and PAX3. DAPI counterstained nuclei. White dashed lines mark colony periphery. Experiments were repeated three times with similar results. Number of colonies analyzed were pooled from n = 3 independent experiments. Data in intensity maps were plotted as the mean. Scale bar, 100 μm.

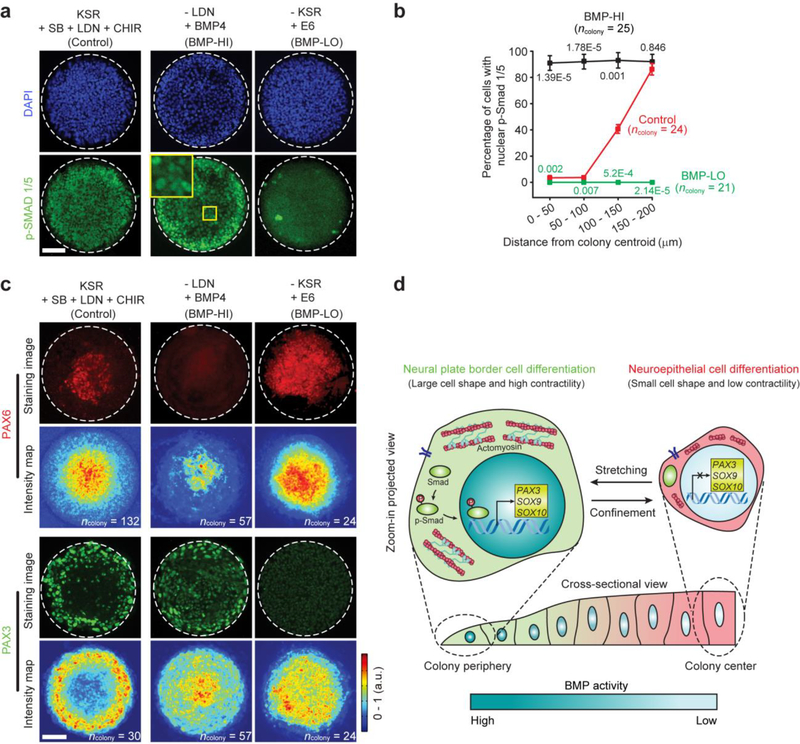

We next modified neural induction medium to elucidate the role of BMP signaling in guiding neuroectoderm patterning. Specifically, modulating LDN concentration in neural induction medium resulted in a dose-dependent BMP signaling response. With high-dose LDN (1 μM), BMP-SMAD signaling was completely repressed across entire colonies at day 4 (Supplementary Fig. 15). Without LDN supplementation, most cells across entire colonies showed prominent nuclear p-SMAD 1/5 at day 4, consistent with BMP activity-inducing properties of the KnockOut Serum Replacement (KSR) medium used in the default neural induction condition33 (Supplementary Fig. 15). Similarly, replacing LDN with BMP4 (25 ng mL−1) in neural induction medium, a condition that promotes BMP signaling, induced prominent nuclear accumulation of p-SMAD 1/5 across entire colonies (Fig. 5a–b). Consequently, by day 9 at colony center, NE differentiation was completely inhibited, whereas NPB differentiation was drastically promoted (Fig. 5c). In distinct contrast, replacing KSR serum in the default neural induction condition with chemically defined Essential 6™ medium, a condition that does not promote BMP signaling34, inhibited nuclear localization of p-SMAD 1/5 at day 4 and promoted NE differentiation at day 9 across entire colonies (Fig. 5a–c). Consistently, NPB differentiation across entire colonies by day 9 was completely suppressed (Fig. 5c).

Figure 5.

BMP-SMAD signaling is required for mechanically guided neuroectoderm patterning. (a) Representative immunofluorescence images showing colonies at day 4 stained for phosphorylated SMAD 1/5 (p-SMAD 1/5). The default neural induction condition (control) was modified as following: - LDN / + BMP4, LDN was replaced with BMP4 (BMP-HI); - KSR / + E6: KSR was replaced with E6 (BMP-LO). CHIR was kept in culture protocols for both BMP-HI and BMP-LO conditions. Zoomed-in image shows a magnified view of colony central area. Scale bar, 100 μm. Experiments were repeated three times with similar results. (b) Percentage of cells with nuclear p-SMAD 1/5 as a function of distance from colony centroid. Number of colonies analyzed were pooled from n = 3 independent experiments. Data represent the mean ± s.e.m. P values were calculated between BMP-HI vs. control and BMP-LO vs. control using unpaired, two-sided Student’s t-tests. (c) Representative fluorescence micrographs and average intensity maps showing colonies at day 9 stained for PAX6 and PAX3. Scale bar, 100 μm. Experiments were repeated three times with similar results. Number of colonies analyzed were pooled from n = 3 independent experiments. Data in intensity maps represent the mean. (d) Geometrical confinement leads to self-organization of morphogenetic factors. Increased cell shape and contractile force at colony periphery result in nuclear accumulation and transcriptional activation of p-SMAD 1/5, which in turn up-regulates NPB specifier genes including PAX3, SOX9 and SOX10. Confined cell shape with limited contractile force at colony center leads to nuclear exclusion of p-SMAD 1/5 and NE differentiation. Modulating cell shape by mechanical stretching or geometrical confinement can thus mediate BMP signaling to regulate neuroectoderm patterning.

Gene expression analysis further confirmed the effect of replacing KSR with Essential 6™ on repressing BMP4 expression (Supplementary Fig. 16). However, replacing LDN with BMP4 in the default neural induction medium upregulated both BMP4 and NOGGIN expression (but not BMP2, BMP6, or BMP7), consistent with previous reports21,35 (Supplementary Fig. 16). Interestingly, silencing of BMP4 or NOGGIN expression using siRNA did not affect neuroectoderm regionalization in micropatterned colonies (Supplementary Fig. 17), excluding endogenous BMP4 or NOGGIN for instructing NE / NPB patterning.

We further seeded hES cells on flat PDMS surfaces uniformly coated with vitronectin at a low (5,000 cell cm−2) or high (50,000 cell cm−2) density condition. Consistent with our previous data, the high density condition significantly down-regulated expression of NPB markers PAX3 and SOX9 compared with the low density condition (Supplementary Fig. 18). However, exogenously activating BMP by supplementing BMP4 (25 ng mL−1) effectively rescued both PAX3 and SOX9 expression (Supplementary Fig. 18). Altogether, our data suggest that morphogenetic cues during emergent neuroectoderm patterning may function upstream of BMP-SMAD signaling to regulate its transcriptional activation (Fig. 5d). Exogenous BMP activation can rescue inhibitory effects of confined cell shape (or small cell spreading area) and impaired cytoskeletal contractile force on BMP signaling.

Our data, together with others17,18,20,21,35, highlight the dependence of fate patterning of hPS cell colonies on both colony geometry and cell density. Etoc et al. recently report a cell density-dependent mechanism for graded BMP signaling involving subcellular lateralization of BMP receptors and diffusion of endogenous NOGGIN35. To explore whether this mechanism was involved in our model, tight-junction integrity was disrupted during neural induction by a brief calcium depletion followed by incubation with Y-27632 (20 μM), a ROCK (Rho-associated protein kinase) inhibitor, a condition known to prevent tight junction formation35,36 (Supplementary Fig. 19). Such treatment has been shown to allow intercellular diffusion of apically delivered TGF-β ligands to bind basolateral receptors and thus restore downstream SMAD activity in high-density epithelial monolayers35,36. However, under this tight-junction disruption condition, proper neuroectoderm patterning was still achieved at day 9 (Supplementary Fig. 19), supporting that subcellular lateralization of BMP receptors was unlikely responsible for establishing graded BMP signaling in our model.

Recent studies suggest cell density-dependent TGF-β inhibition in epithelial cells due to crosstalk with the Hippo pathway37. The Hippo effector YAP/TAZ is also mechanosensitive and can be regulated by both cell shape and mechanical forces38,39. To examine the role of YAP/TAZ, a small molecular inhibitor cerivastatin (CER), which promotes YAP phosphorylation and thus nuclear exclusion40, was supplemented in the default neural induction medium with LDN replaced with BMP4 (25 ng mL−1) to promote BMP activity (Supplementary Fig. 20). Even though nuclear YAP was suppressed across entire colonies at day 4, nuclear localization of p-SMAD 1/5 remained evident and all cells across entire colonies differentiated into PAX3+ NPB cells at day 9. Thus, YAP nuclear translocation did not correlate with p-SMAD 1/5 responses, and YAP was unlikely to directly regulate BMP-SMAD signaling and thus neuroectoderm patterning. It remains a future goal to determine how geometrical confinement leads to spontaneous self-organization of morphogenetic factors, how cell shape and cytoskeletal contractility activate BMP-SMAD signaling41, and how BMP and WNT signals converge to regulate NPB specification42,43.

Our micropatterned neuroectoderm developmental model does not contain non-neural ectoderm or mesenchymal tissues, which may play important roles in instructing neuroectoderm formation in vivo8–10. Nonetheless, there are well documented tissue isolation studies using in vivo models that support neural induction as an autonomous process44. The origin of NPB cells is also believed to arise from neural but not epidermal ectoderm27,29. Altogether, our neuroectoderm developmental model is useful for studying self-organizing principles involved in autonomous patterning and regionalization of neuroectoderm tissues.

In this work, we demonstrate that autonomous patterning of neuroectoderm tissue with proper NP and NPB regionalization emerges de novo as the tissue physically takes shape and self-assemble in pre-patterned geometrical confinements. Self-organization of morphogenetic cues, including cell shape and cytoskeletal contractility, could directly feedback to mediate BMP activity and thus dictate spatial regulations of neuroectoderm patterning. Colony geometry can directly influence cell signaling and cell-cell communication through regulatory mechanisms involving dynamic morphogenetic cues and diffusible signals17,18,20,21,35. Such signaling crosstalk involving both biophysical and biochemical determinants may play an important role in controlling patterning networks to ensure the remarkable robustness and precision of tissue self-organization in vivo1–5. We envision that our neuroectoderm developmental model can facilitate future efforts in generating theoretical frameworks that integrate knowledge at the mechanical, cellular and gene-regulatory levels17,18,20,21,35. Future mechanistic investigations of tissue mechanics-guided neuroectoderm patterning will therefore help advance fundamental understanding of neural development and disease.

METHODS

Culture medium.

PluriQ™ Human Cell Conditioned Medium (MTI-GlobalStem) was used to support feeder-free growth of hPS cells45. Growth medium comprised DMEM/F12 (GIBCO), 20% KnockOut Serum Replacement (KSR; GIBCO), β-mercaptoethanol (0.1 mM; GIBCO), glutamax (2 mM; GIBCO), 1% non-essential amino acids (GIBCO), and human recombinant basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF, 4 ng mL−1; GlobalStem) as described previously26. Neural induction medium comprised growth medium, TGF-β inhibitor SB 431542 (10 μM; Cayman Chemical) and BMP4 inhibitor LDN 193189 (500 nM; Selleckchem)22. At day 3, CHIR99021 (3 μM; Cayman Chemical) was supplemented into neural induction medium and was withdrawn at day 423,24. Motor neuron (MN) differentiation medium comprised N2B27 medium, retinoic acid (RA, 1 μM; Stemcell Technologies) and smoothened agonist (SAG, 500 nM; Stemcell Technologies)26. N2B27 medium comprised 1:1 mixture of DMEM/F12 and neurobasal medium (GIBCO), 1% N2 supplement (GIBCO), 2% B-27 supplement (GIBCO), 2 mM glutamax and 1% non-essential amino acids. Neural crest (NC) cell differentiation medium comprised N2B27 medium and 3 μM CHIR9902123,24. Culture medium was pre-equilibrated at 37 °C and 5% CO2 before use.

Cell culture.

Both H1 hES cell line (WA01, WiCell; NIH registration number: 0043) and SOX10-EGFP bacterial artificial chromosome hES cell reporter line (H9; WA09, WiCell; NIH registration number: 0062) were cultured on mitotically inactive mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs; GlobalStem) in growth medium. Another H9 hES cell line was cultured using mTeSR1 medium (Stemcell Technologies) and lactate dehydrogenase-elevating virus (LDEV)-free hES cell-qualified reduced growth factor basement membrane matrix Geltrex™ (Thermo Fisher Scientific) as described previously19. The hiPS cell line, a gift from Dr. Paul H. Krebsbach, was cultured in PluriQ™ Human Cell Conditioned Medium on tissue culture dishes coated with poly[2-(methacryloyloxy)ethyl dimethyl-(3-sulfopropyl)ammonium hydroxide]45.

The STEMPRO EZPassage Disposable Stem Cell Passaging Tool (Invitrogen) was used for passaging the H1 and SOX10-EGFP hES cell lines every 5 d as described previously26. A modified pasteur pipette was used to remove differentiated cells under a stereomicroscope (Olympus). After brief treatment with TrypLE Select (Invitrogen) to release MEFs, remaining cells were collected using a cell scraper (BD Biosciences) before transferred onto a tissue culture dish coated with gelatin (Sigma) and incubated for 45 min. Contaminating MEFs would attach to the dish. hES cells in suspension were then collected, centrifuged and re-dispersed in growth medium supplemented with Y27632 (10 μM; Enzo Life Sciences) before cell seeding. For H9 hES and hiPS cells, cells were digested using TrypLE Select before cell seeding19.

The Human Pluripotent Stem Cell Research Oversight Committee at the University of Michigan have approved all protocols for the use of hPS cells. All cell lines were authenticated by Cell Line Genetics as karyotypically normal and were tested negative for mycoplasma contamination using the LookOut Mycoplasma PCR Detection Kit (Sigma-Aldrich).

Microcontact printing.

Soft lithography was used to generate patterned PDMS stamps from silicon molds fabricated using photolithography and deep reactive-ion etching (DRIE), as described previously30. These PDMS stamps were used to generate micropatterned cell colonies and patterned single cells using microcontact printing. Briefly, to generate patterned cell colonies and single cells on flat PDMS surfaces, round glass coverslips with a diameter of 18 mm (Fisher Scientific) were spin coated (Spin Coater; Laurell Technologies) with a thin layer of PDMS prepolymer comprising PDMS base monomer and curing agent (10:1 w / w; Sylgard 184, Dow-Corning). PDMS was then thermally cured at 110 °C for at least 24 hr. In parallel, PDMS stamps were immersed in a vitronectin solution (20 μg mL−1; Trevigen) for 1 hr before blown dry under nitrogen. Vitronectin has been reported to support self-renewal of hPS cells46. Vitronectin-coated PDMS stamps were then placed in conformal contact with UV ozone-treated PDMS on coverslips (ozone cleaner; Jelight). After removing PDMS stamps, coverslips were sterilized using ethanol (Fisher Scientific). Protein adsorption to PDMS surfaces not coated with vitronectin was prevented by immersing coverslips in 0.2% Pluronics F127 NF solution (BASF) for 30 min. Coverslips were rinsed with PBS before placed into tissue culture plates for cell seeding. For micropatterned cell colonies, PDMS stamps containing circular patterns with diameters of 300, 400, 500 and 800 μm were used. For patterned single cells, PDMS stamps containing circular patterns with diameters of 25 and 45 μm were used.

To apply continuous stretching to the central zone of micropatterned cell colonies, microcontact printing was performed to print circular adhesive patterns with a diameter of 400 μm onto the deformable PDMS membrane on top of pressurization compartments (with a diameter of 200 μm) in a custom designed microfluidic cell stretching device. To this end, a custom desktop aligner designed for fabrication of multilayer microfluidic devices was used47. Briefly, the vitronectin-coated PDMS stamp and the microfluidic cell stretching device were mounted onto the top and bottom layer holders of the aligner, respectively. Under a digital microscope, the X / Y / θ stage holding the bottom layer holder was carefully adjusted to align the PDMS stamp and the microfluidic cell stretching device. The PDMS stamp was then gently pressed to achieve conformal contact with the microfluidic cell stretching device to transfer vitronectin from the stamp to the PDMS membrane on top of pressurization compartments.

Stencil micropatterning.

Stencil was generated by punching through-holes into a PDMS membranes using a 500 μm biopsy puncher (Fisher Scientific). To generate PDMS membrane, PDMS prepolymer was spun on a silicon wafer before PDMS was thermally cured at 60 °C for at least 24 hr. The PDMS membrane was then peeled off from the silicon wafer before punching through-holes into the membrane. Coverslips were immersed in a vitronectin solution (20 μg mL−1) for 1 hr before the PDMS stencil was placed onto the coverslip for cell seeding.

Immunocytochemistry.

As described previously26, 4% paraformaldehyde (Electron Microscopy Sciences) was used for cell fixation before permeabilization with 0.1% Triton X-100 (Roche Applied Science). Primary antibodies listed in Supplementary Table 2 were then used for protein detection. For immunolabeling, goat-anti mouse Alexa Fluor 488 and/or goat-anti rabbit Alexa Fluor 546 secondary antibodies were used. To label actin microfilaments, Alexa Fluor 555 conjugated phalloidin (Invitrogen) was used. Cells were stained with 4,6-diamidino-2- phenylindole (DAPI; Invitrogen) to visualize the nucleus.

Image analysis.

Fluorescence images were recorded using either an inverted epifluorescence microscope (Zeiss Axio Observer Z1; Carl Zeiss MicroImaging) equipped with a monochrome CCD camera or an Olympus DSUIX81 spinning disc confocal microscope equipped with an EMCCD camera (iXon X3, Andor). Fluorescence images of micropatterned cell colonies were first cropped using a custom-developed MATLAB program (MathWorks) to a uniform circular size (as defined by colony size) with pattern centroids aligned. Due to intrinsic inhomogeneous cell seeding, multilayered cellular structures would inevitably appear in micropatterned cell colonies. These multilayered colonies were excluded from data analyses. Fluorescence intensity of each pixel in cropped images was normalized by the maximum intensity identified in each image. These normalized images were stacked together to obtain average intensity maps. To normalize fluorescence intensities of cell lineage markers by DAPI intensity, the intensity of cell lineage markers for each pixel was divided by corresponding DAPI intensity. These DAPI-normalized images were stacked together to obtain average DAPI-normalized intensity maps. To plot average intensity as a function of distance from colony centroid, average intensity maps for circular cell colonies were divided into 100 concentric zones with equal widths. The average pixel intensity in each concentric zone was calculated and plotted against the mean distance of the concentric zone from colony centroid. From average intensity plots of cell lineage markers, values of the full width at half maximum (FWHM) were determined as the difference between the two radial positions at which the average fluorescence intensity of individual markers is equal to half of its maximum value. The FWHM for average DAPI intensity plots was decided by first calculating the half width at half maximum (HWHM), which was determined as the radial position at which the average DAPI intensity is equal to half of its maximum value at colony centroid. FWHM for average DAPI intensity plots was then calculated as double the HWHM.

Colony thickness and nucleus orientation were determined manually with ImageJ using confocal images showing X-Z sections of cell colonies stained for N-CADHERIN. Normalized nucleus dimension was further calculated as the ratio of the height to width of a circumscribed rectangle bounding the nucleus. Projected cell areas were quantified with the CellProfiler program using immunofluorescence images showing ZO-1 staining. Nuclei stained by DAPI was used for identification of each cell as primary objects in CellProfiler. ZO-1 staining images were first filtered to remove background before segregated using a propagation method to determine cell area. To determine projected cell area for central and peripheral zones of cell colonies, a binary circular mask with a diameter of half of the actual pattern diameter was used to crop original cell colony images. Cells falling on the mask boundary were excluded from quantification. Immunofluorescence images showing p-SMAD 1/5 staining were analyzed manually using ImageJ. Cells with nuclear p-SMAD 1/5 were identified as those showing dominant nuclear fluorescence and absence of cytoplasmic fluorescence. Conversely, cells with cytoplasmic p-SMAD 1/5 were identified as those showing absence of nuclear fluorescence. To quantify the spatial distribution of BMP-SMAD activation, circular colonies were divided into 4 concentric zones with equal widths. The percentage of cells with nuclear p-SMAD 1/5 in each zone was then calculated and plotted against the distance from colony centroid.

Tracking cell migration and unbiased random walk model.

On day 0 before cell seeding, hPS cells were labeled with CellTracker Red CMTPX Dye (ThermoFisher Scientific) for 30 min. Labeled hPS cells were mixed with unlabeled cells at a ratio of 1:7 before the cell mixture was seeded onto coverslips containing micropatterned circular adhesive islands. From day 2 (t = 0 hr) to day 4, live cell imaging was conducted using the Zeiss Axio Observer Z1 inverted epifluorescence microscope enclosed in the XL S1 incubator (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging) to maintain cell culture at 37 °C and 5% CO2. Both bright field and fluorescence images were recorded every 20 min for a total of 41 hr. All time-lapse images were reconstructed using the image processing software Image-Pro Plus to generate TIFF stacks for cell migration tracking. For each image, peripheries of each individual CellTracker labeled cells were marked manually. Positions of cell centroids were then identified from each image to calculate end-to-end cell displacement D and radial displacement during cell migration as a function of time. For radial displacement calculations, cells were divided into two groups based on their radial positions relative to colony centroid at t = 0 hr (R0) (‘central’: 0 ≤ R0 ≤ 100 μm; ‘peripheral’: 100 < R0 ≤ 200 μm). If labeled hPS cells divided during cell migration tracking, one of daughter cells was randomly selected to continue tracking.

An unbiased random walk model was used for modeling cell migration during emergent neuroectoderm patterning in micropatterned circular hPS cell colonies. In this model, cells move randomly without any preferred migration direction. Cell centroids at each time step n (denoted here as ) can be calculated as , where A is a random variable following a uniform distribution on [0, 1] and is a random unit direction vector. Parameter V denotes the maximum cell centroid displacement during each time step, and it can be obtained through least square fitting for experiment data of mean square end-to-end cell displacement D2 using the expression .

Cell viability and proliferation assays.

Cell viability was determined using Live/Dead, Viability/Cytotoxicity Kit (ThermoFisher Scientific) per the manufacturer’s instruction. On day 4 and day 8, culture medium was replaced with fresh medium containing ethidium homodimer (EthD-1; 4 μM). After incubation for 30 min, fluorescence images were recorded using the Zeiss Axio Observer Z1 inverted epifluorescence microscope to quantify the number of dead cells in each colony.

Click-iT™ EdU Alexa Fluor™ 488 Imaging Kit (ThermoFisher Scientific) was used to measure cell proliferation per manufacturers’ instruction. Briefly, on day 3, half of culture medium was replaced with fresh medium containing EdU (20 μM). Cells were incubated for 2 hr before fixed, permeabilized and incubated with Click-iT reaction cocktail for 30 min. Cell nuclei were counterstained with DAPI. Cells were then examined under fluorescence microscopy (Zeiss Axio Observer Z1) to detect EdU-stained cell nuclei.

Traction force measurement.

Traction force was analyzed using PDMS micropost arrays (PMAs) as described previously30. Briefly, PMAs were first prepared for cell attachment using microcontact printing to coat micropost top surfaces with vitronectin. To quantify traction forces of micropatterned cell colonies or single cells, microcontact printing was used to define circular adhesive patterns of different sizes. PMAs were labeled with Δ9-DiI (5 μg mL−1; Invitrogen) for 1 hr. Protein adsorption to all PDMS surfaces not coated with vitronectin was prevented by incubating in 0.2% Pluronics F127 NF solution (BASF) for 30 min.

Live cell imaging was conducted using the Zeiss Axio Observer Z1 inverted epifluorescence microscope enclosed in the XL S1 incubator. Images of micropost tops were recorded using a 40 × (for single cells) or 20 × (for colonies) objective (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging). All images were recorded at day 4 and were analyzed using a custom-developed MATLAB program (MathWorks), as described previously48, to obtain traction force maps. To determine average traction stress maps for micropatterned cell colonies, individual traction force maps were first adjusted to the same size before being stacked together to obtain average traction stress maps. To plot average traction stress as a function of distance from colony centroid, circular colonies were first divided into 20 concentric zones with equal widths. The average traction stress in each concentric zone was then calculated and plotted against the mean distance of the concentric zone from colony centroid.

Microfluidic cell stretching device.

The microfluidic cell stretching device comprised a PDMS structural layer, a PDMS inlet block and a glass coverslip. The PDMS structural layer, which contained a microfluidic network for applying pressures to simultaneously activate 64 pressurization compartments to induce PDMS membrane deformation, was fabricated using soft lithography. Briefly, PDMS prepolymer was spin coated on a silicon mold generated using photolithography and DRIE. The PDMS layer was thermally cured at 110 °C for at least 24 hr before peeled off from the silicon mold. An inlet for fluid connections was then punched into the PDMS structural layer using a 1 mm biopsy punch (Fisher Scientific). Both the coverslip and PDMS structural layer were briefly cleaned with 100% ethanol (Fisher Scientific) and blown dry under nitrogen before treated with air plasma (Plasma Prep II; SPI Supplies) and bonding together. In parallel, another PDMS block was prepared, and an inlet for fluid connection was punched into the PDMS block with a 0.5 mm biopsy punch. After both treated with air plasma, the PDMS block and the PDMS structural layer were bonded together with their fluid inlets aligned manually. The microfluidic cell stretching device was baked at 110 °C for at least another 24 hr to ensure robust bonding between different layers. Deionized water was injected into the microfluidic cell stretching device before applying pressure through a microfluidic pressure pump (AF1, Elveflow). Elveflow Smart Interface software was used for programming the pressure pump for continuous cell stretching with a square-wave pattern (pulse width of 2 hr, period of 4 hr, and 50% duty cycle).

RNA isolation and qRT-PCR analysis.

As described previously26, RNA was extracted from cells using RNeasy kit (Qiagen) following the manufacturer’s instruction. A CFX Connect SYBR Green PCR Master Mix system (Bio-Rad) was used for qRT-PCR. For relative quantification, human TBP primer was used as an endogenous control. An arbitrary Ct value of 40 was assigned to samples in which no expression was detected. Relative expression levels were determined by calculating 2−ΔΔCt with the corresponding s.e.m. All analyses were performed with at least 3 biological replicates and 3 technical replicates.

Western blotting.

As described previously26, whole cell lysates were prepared and separated on SDS-polyacrylamide gel before transferred to PVDF membranes. PVDF membranes were then incubated with blocking buffer (Li-Cor) for 1 hr before soaked with primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C. Blots were then incubated with IRDye secondary antibodies (Li-Cor) for 1 hr. An Odyssey Sa Infrared Imaging System (Li-Cor) was used for protein expression detection. Uncropped scans of Western blots are shown in Supplementary Fig. 2.

siRNA knockdown.

As described previously26, hPS cells were transfected with BMP4 siRNA and scramble control using Viromer Blue (OriGene). Briefly, cells were plated at 80% confluence on vitronectin coated 6-well plates and subjected to siRNA transfection the next day. After 24 hr, transfected cells were seeded onto coverslips containing micropatterned circular adhesive islands. Three additional siRNA treatments were conducted at day 2, 4, and 6 after cell seeding.

Pharmacological treatment.

To inhibit actomyosin contractility, blebbistatin (10 μM in DMSO; Cayman Chemical) was supplemented to culture medium from day 1 till cell fixation. To modulate BMP signaling, recombinant human BMP4 (25 ng mL−1; R&D Systems) was supplemented to neural induction medium.

Statistics.

Statistical analysis was performed using Excel (Microsoft). The significance between two groups was analyzed by a two-sided Student t-test. In all cases, a P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Code availability.

MATLAB scripts used in this work are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank A. Liu for comments on the manuscript. This work is supported in part by the National Science Foundation (CMMI 1129611 and CBET 1149401 to J. Fu and CMMI 1662835 to Y. Sun), the American Heart Association (12SDG12180025 to J. Fu), and the Department of Mechanical Engineering at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. The Lurie Nanofabrication Facility at the University of Michigan, a member of the National Nanotechnology Infrastructure Network (NNIN) funded by the National Science Foundation, is acknowledged for support in microfabrication.

Footnotes

COMPETING FINANCIAL INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary information files and from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wozniak MA & Chen CS Mechanotransduction in development: A growing role for contractility. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 10, 34–43 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Keller R Physical biology returns to morphogenesis. Science 338, 201–203 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heller E & Fuchs E Tissue patterning and cellular mechanics. J. Cell Biol 211, 219–231 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chan CJ, Heisenberg C-P & Hiiragi T Coordination of morphogenesis and cell-fate specification in development. Curr. Biol 27, R1024–R1035 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gilmour D, Rembold M & Leptin M From morphogen to morphogenesis and back. Nature 541, 311–320 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schroeder TE Neurulation in Xenopus laevis. An analysis and model based upon light and electron microscopy. J. Embryol. Exp. Morphol 23, 427–462 (1970). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Colas J-F & Schoenwolf GC Towards a cellular and molecular understanding of neurulation. Dev. Dynam 221, 117–145 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Munoz-Sanjuan I & Brivanlou AH Neural induction, the default model and embryonic stem cells. Nat. Rev. Neurosci 3, 271–280 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stern CD Neural induction: Old problem, new findings, yet more questions. Development 132, 2007–2021 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bier E & De Robertis EM BMP gradients: A paradigm for morphogen-mediated developmental patterning. Science 348 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vijayraghavan DS & Davidson LA Mechanics of neurulation: From classical to current perspectives on the physical mechanics that shape, fold, and form the neural tube. Birth Defects Res 109, 153–168 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tesar PJ et al. New cell lines from mouse epiblast share defining features with human embryonic stem cells. Nature 448, 196–199 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O’Leary T et al. Tracking the progression of the human inner cell mass during embryonic stem cell derivation. Nat. Biotechnol 30, 278–282 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nakano T et al. Self-formation of optic cups and storable stratified neural retina from human ESCs. Cell Stem Cell 10, 771–785 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lancaster MA et al. Cerebral organoids model human brain development and microcephaly. Nature 501, 373–379 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Poh Y-C et al. Generation of organized germ layers from a single mouse embryonic stem cell. Nat. Commun 5, 4000 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Warmflash A et al. A method to recapitulate early embryonic spatial patterning in human embryonic stem cells. Nat. Meth 11, 847–854 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ma Z et al. Self-organizing human cardiac microchambers mediated by geometric confinement. Nat. Commun 6, 7413 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shao Y et al. Self-organized amniogenesis by human pluripotent stem cells in a biomimetic implantation-like niche. Nat. Mater 16, 419–425 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shao Y et al. A pluripotent stem cell-based model for post-implantation human amniotic sac development. Nat. Commun 8, 208 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tewary M et al. A stepwise model of reaction-diffusion and positional-information governs self-organized human peri-gastrulation-like patterning. Development 144, 4298–4312 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chambers SM et al. Highly efficient neural conversion of human ES and iPS cells by dual inhibition of Smad signaling. Nat. Biotechnol 27, 275–280 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mica Y et al. Modeling neural crest induction, melanocyte specification, and disease-related pigmentation defects in hESCs and patient-specific iPSCs. Cell Rep 3, 1140–1152 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tchieu J et al. A modular platform for differentiation of human PSCs into all major ectodermal lineages. Cell Stem Cell 21, 399–410 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hong CS & Saint-Jeannet JP The activity of Pax3 and Zic1 regulates three distinct cell fates at the neural plate border. Mol. Biol. Cell 18, 2192–2202 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sun Y et al. Hippo/YAP-mediated rigidity-dependent motor neuron differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells. Nat. Mater 13, 599–604 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sauka-Spengler T & Bronner-Fraser M A gene regulatory network orchestrates neural crest formation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 9, 557–568 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Walther C & Gruss P PAX-6, a murine paired box gene, is expressed in the developing CNS. Development 113, 1435–1449 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Milet C & Monsoro-Burq AH Neural crest induction at the neural plate border in vertebrates. Dev. Biol 366, 22–33 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fu J et al. Mechanical regulation of cell function with geometrically modulated elastomeric substrates. Nat. Meth 7, 733–736 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wilson PA et al. Concentration-dependent patterning of the Xenopus ectoderm by BMP4 and its signal transducer Smad1. Development 124, 3177–3184 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Michielin F et al. Microfluidic-assisted cyclic mechanical stimulation affects cellular membrane integrity in a human muscular dystrophy in vitro model. RSC Adv 5, 98429–98439 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xu R-H et al. Basic FGF and suppression of BMP signaling sustain undifferentiated proliferation of human ES cells. Nat. Meth 2, 185–190 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lippmann ES, Estevez-Silva MC & Ashton RS Defined human pluripotent stem cell culture enables highly efficient neuroepithelium derivation without small molecule inhibitors. Stem Cells 32, 1032–1042 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Etoc F et al. A balance between secreted inhibitors and edge sensing controls gastruloid self-organization. Dev. Cell 39, 302–315 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nallet-Staub F et al. Cell density sensing alters TGF-β signaling in a cell-type-specific manner, independent from Hippo pathway activation. Dev. Cell 32, 640–651 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Varelas X et al. The Crumbs complex couples cell density sensing to Hippo-dependent control of the TGF-β-SMAD pathway. Dev. Cell 19, 831–844 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dupont S et al. Role of YAP/TAZ in mechanotransduction. Nature 474, 179–183 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wada K-I et al. Hippo pathway regulation by cell morphology and stress fibers. Development 138, 3907–3914 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sorrentino G et al. Metabolic control of YAP and TAZ by the mevalonate pathway. Nat. Cell Biol 16, 357–366 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kopf J et al. BMP growth factor signaling in a biomechanical context. BioFactors 40, 171–187 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.de Crozé N, Maczkowiak F & Monsoro-Burq AH Reiterative AP2a activity controls sequential steps in the neural crest gene regulatory network. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 108, 155–160 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Steventon B et al. Differential requirements of BMP and Wnt signalling during gastrulation and neurulation define two steps in neural crest induction. Development 136, 771–779 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Moury JD & Schoenwolf GC Cooperative model of epithelial shaping and bending during avian neurulation: autonomous movements of the neural plate, autonomous movements of the epidermis, and interactions in the neural plate/epidermis transition zone. Dev. Dynam 204, 323–337 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Villa-Diaz LG et al. Synthetic polymer coatings for long-term growth of human embryonic stem cells. Nat. Biotechnol 28, 581–583 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Braam SR et al. Recombinant vitronectin is a functionally defined substrate that supports human embryonic stem cell self-renewal via αVβ5 integrin. Stem Cells 26, 2257–2265 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li X et al. Desktop aligner for fabrication of multilayer microfluidic devices. Rev. Sci. Instrum 86, 075008 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Weng S et al. Mechanosensitive subcellular rheostasis drives emergent single-cell mechanical homeostasis. Nat. Mater 15, 961–967 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.