Abstract

We aimed to investigate metabolites associated with the 28-joint disease activity score based on erythrocyte sedimentation rate (DAS28-ESR) in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) using capillary electrophoresis quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Plasma and urine samples were collected from 32 patients with active RA (DAS28-ESR≥3.2) and 17 with inactive RA (DAS28-ESR<3.2). We found 15 metabolites in plasma and 20 metabolites in urine which showed a significant but weak positive or negative correlation with DAS28-ESR. When metabolites between active and inactive patients were compared, 9 metabolites in plasma and 15 in urine were found to be significantly different. Consequently, we selected 11 metabolites in plasma and urine as biomarker candidates which significantly correlated positively or negatively with DAS28-ESR, and significantly differed between active and inactive patients. When a multiple logistic regression model was built to discriminate active and inactive cohorts, three variables—histidine and guanidoacetic acid from plasma and hypotaurine from urine—generated a high area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve value (AUC = 0.8934). Thus, this metabolomics approach appeared to be useful for investigating biomarkers of RA. Combination of plasma and urine analysis may lead to more precise and reliable understanding of the disease condition. We also considered the pathophysiological significance of the found biomarker candidates.

Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a systemic autoimmune disease which involves inflammation of the synovium and destruction of joint cartilage and bone [1,2]. RA is pathologically heterogeneous, with many suspected triggers for development of the disease, including environmental [3], epigenetic [4], and genetic factors [5–7] as well as several types of post-translational modifications of proteins [2]. The complexity of the disease is further suggested by the various clinical features of RA, as well as the differences in response to therapies among patients treated with synthetic and/or biological disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) [2,8,9].

To date, various omics studies have aimed to better understand the molecular pathophysiology of RA and explore the disease condition in individual patients. In recent years, metabolomics has been acknowledged to be a powerful tool for identifying potential biomarkers in RA patients using different types of samples such as plasma, serum, urine, and synovial fluids [10–14]. The advantages of metabolomics may not only be in the discovery of biomarkers but also in the identification of rapid physiological responses according to disease activities, as well as in evaluation of the prognosis and therapeutic response to treatment and understanding the pathophysiology of the disease. However, the correlation of the dynamics of metabolites with the disease activity of RA has not been well investigated.

In this study, we obtained urine and plasma samples from biologics-naive RA patients, and searched for metabolites associated with disease activity using capillary electrophoresis quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry (CE-Q-TOFMS). This method allows almost any polar and charged species to be analyzed, combines high-resolution separations with high detection selectivity and sensitivity, and maintains high reproducibility [15,16].

Materials and methods

Study cohorts

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee, Kyoto University Graduate School and Faculty of Medicine. We collected blood and urine from 50 RA patients diagnosed with RA based on the American College of Rheumatology guidelines at the Rheumatic Disease Center, Kyoto University Hospital. The data of one male patient was omitted because he was receiving hemodialysis. No patient had received treatment with biologics, and RA disease activity was categorized based on the 28-joint disease activity score based on erythrocyte sedimentation rate (DAS28-ESR). Patients with DAS28-ESR≥3.2 and those with DAS28-ESR<3.2 were defined as active and inactive patients, respectively. Other clinical information was obtained from the medical records. Blood was collected from 10 non-RA volunteers matched for age and gender who served as controls. All RA patients and control subjects were recruited from November 2012 to May 2013, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants on the day of sampling.

Sample preparation

All blood and urine samples were kept at 4°C immediately after collection and processed within 1 hour. Plasma were prepared from EDTA-anticoagulated blood. All plasma and urine samples were aliquoted and stored at -80°C until further analysis.

Metabolomics analysis

Plasma or urine samples (50 μL) were added to 450 μL of methanol (134–14523, FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation [Wako], Osaka, Japan) containing internal standards (H3304-1002; Human Metabolome Technologies, Inc. [HMT], Tsuruoka, Japan), 200 μL of Milli-Q water and 500 μL of chloroform (033–08631, Wako). The samples were then thoroughly mixed by vortex mixer and centrifuged at 9,100 × g at 4°C for 20 min. Subsequently, 350 μL of the upper aqueous layer was centrifugally filtered through a 5-kDa cutoff filter (provided by HMT) at 9,100 × g overnight at 4°C to remove proteins and macromolecules. The filtrate was evaporated and resuspended in 50 μL of Milli-Q water containing internal standards (H3304-1004, HMT) for CE-Q-TOFMS.

A Capillary Electrophoresis System (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, California) with an Agilent 6510 Q-TOF mass spectrometer (Agilent Technologies) was used for CE-Q-TOFMS. The fused silica capillary and analysis reagents were provided by HMT. To analyze cationic metabolites, the sample solution was injected at a pressure of 50 mbar for 10 s, and the applied voltage was set at 27 kV. Capillary and fragmenter voltage in positive ion mode were set at 4000 and 80 V. A flow rate of heated dry N2 gas (heater temperature, 300°C) was maintained at 5 psig and 7 L/min. The spectrometer was scanned from m/z 100 to 3000. To analyze anionic metabolites, the sample solution was injected at a pressure of 50 mbar for 25 s, and the applied voltage was 30 kV. Capillary and fragmenter voltage in negative ion mode were set at 3500 and 125 V. A flow rate of heated dry N2 gas (heater temperature, 300°C) was maintained at 5 psig and 7 L/min. The spectrometer was scanned from m/z 100 to 3000. Other conditions were as described previously [17], with slight modifications.

Data processing of MS was started by extracting peaks using MasterHands automatic integration software (Keio University, Tsuruoka, Japan) to obtain peak information, including m/z, migration time (MT), and peak area [18]. Signal peaks corresponding to isotopomers, adduct ions, and other product ions of known metabolites were excluded, and remaining peaks were annotated with putative metabolites from the MasterHands database based on their MTs and m/z values. The tolerance range for the peak annotation was configured at ±0.2 min (Anion)/±1.0min (Cation) for MT and ±40 ppm for m/z. In addition, peak areas were normalized against those of the internal standards, and relative area values of urine samples were further normalized by creatinine 13C peak. The metabolite IDs were adopted from the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes database (KEGG, https://www.genome.jp/kegg/).

Statistical analysis

Student’s t test or Welch’s t test was performed to assess statistical significance of differences between the two groups using Genedata Analyst (Genedata AG., Basel, Switzerland). Fisher’s exact test was performed to assess categorical variables with JMP Pro 12.2.0 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Correlation of metabolites with DAS28-ESR was analyzed by the Spearman rank correlation test with JMP Pro. Principal component analysis (PCA), partial least-squares discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) and validation of the PLS-DA model by permutation tests were conducted with normalize metabolomics data using MetaboAnalyst 4.0 (ref [19], http://www.metaboanalyst.ca/). A multiple logistic regression (MLR) model to discriminate active and inactive cohorts was developed by a stepwise variable selection method (forward and backward selection), conducted with a threshold of p<0.1 for adding and eliminating features with JMP Pro.

Results

Subject characteristics

The primary characteristics of the RA patients and control subjects are shown in Table 1. We recruited 32 active (DAS28-ESR≥3.2) and 17 inactive (DAS28-ESR<3.2) RA patients. Most RA patients had been treated with methotrexates and/or glucocorticoids, and none had been treated with biologics.

Table 1. Profiles of control subjects and RA patients.

| Control | All RA | P-value2) | Active RA1) | Inactive RA1) | P-value3) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 10 | 49 | 32 | 17 | ||

| Age | 63 ± 14 | 60 ± 13 | 0.540 | 61 ± 13 | 59 ± 12 | 0.492 |

| (range) | (51–86) | (34–81) | (34–81) | (34–81) | ||

| Sex ratio | 10/0 | 43/6 | 0.577 | 27/5 | 16/1 | 0.650 |

| (female/male) | ||||||

| DAS28-ESR | - | 3.71 ± 1.23 | 4.38 ± 0.94 | 2.46 ± 0.54 | <0.001 | |

| (range) | (1.12–7.62) | (3.23–7.62) | (1.12–3.11) | |||

| Treatment | - | MTX: 39 | MTX: 27 | MTX: 12 | 0.285 | |

| GCs: 22 | GCs: 17 | GCs: 5 | 0.140 |

RA, rheumatoid arthritis; DAS28-ESR, disease activity score using 28 joint counts based on erythrocyte sedimentation rate; MTX, methotrexate; GCs, glucocorticoids.

1) Active patients and inactive patients was defined as patients with DAS28-ESR≥3.2 and those with DAS28-ESR<3.2, respectively.

2) Student’s t test or Fisher’s exact test between control and RA groups.

3) Student’s t test or Fisher’s exact test between active and inactive RA groups.

Values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and ranges (minimum to maximum).

Comparison of metabolites in plasma between RA patients and control subjects

Using the CE-Q-TOFMS method, 104 metabolites in plasma and 217 metabolites in urine were identified and quantified (S1 Dataset). Since ketoprofen found in urine was an exogenous metabolite, we excluded it from the following analysis.

First, to evaluate the validity of the collected patient samples, principal component analysis (PCA) was performed using plasma metabolites from RA patients and control subjects, but the results showed no solid separation between the two groups (S1 Fig). However, when PLS-DA was performed, results demonstrated an acceptable cluster between the two groups (Fig 1) with good model parameters (R2 = 0.75529, Q2 = 0.4068). Validation of the PLS-DA model by permutation tests showed p = 0.022 (S2 Fig), which indicated that the separation was significant.

Fig 1. PLS-DA score plot between RA patients (n = 49) and control subjects (n = 10) based on metabolic profiles in plasma.

The green and red dots represent RA patient and control samples, respectively.

When the metabolites from RA patients and controls were compared, we found 24 metabolites that were significantly different (Welch t-test with p<0.05) between the two groups (Table 2). Some of the metabolites were in agreement with previously published data that compared RA patients and control subjects, such as decreased levels of histidine, methionine, and serine, and increased levels of glyceric acid, phenylalanine, and tyrosine in RA patients [12,14,20–22]. Moreover, the identified metabolites were major intermediates of metabolic pathways, including glycolysis, the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, and pathways involving amino acid metabolism, which were also in agreement with previous reports [12,14]. These data suggest that the collected samples were not derived from exceptional RA patients.

Table 2. Metabolites in plasma that were significantly different between RA patients and control subjects.

| Metabolite | KEGG ID | Mode | m/z | MT | P-value1) | Fold change2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RA/Control | ||||||

| Azelaic acid | C08261 | A | 187.097 | 12.583 | <0.001 | -2.98 |

| N-Acetylleucine | C02710 | A | 172.098 | 8.229 | <0.001 | -2.21 |

| Pyruvic acid | C00022 | A | 87.009 | 13.462 | <0.001 | 1.99 |

| Phenylalanine | C00079 | C | 166.087 | 12.137 | <0.001 | 1.36 |

| Glycerol-3-phosphate | C00093 | A | 171.006 | 12.623 | 0.001 | 1.89 |

| Cysteine-glutathione disulphide | N/A | C | 427.096 | 12.759 | 0.002 | -1.69 |

| Glutamic acid; threo-beta-methylaspartic acid | C00025; N/A | C | 148.061 | 11.953 | 0.002 | 1.44 |

| Glyceric acid | C00258 | A | 105.019 | 10.814 | 0.002 | 1.26 |

| Tyrosine | C00082 | C | 182.082 | 12.438 | 0.005 | 1.19 |

| Cysteine-glutathione disulphide–Divalent | N/A | C | 214.052 | 12.757 | 0.005 | -1.56 |

| Glucuronic acid; Galacturonic acid | C00191; C08348 | A | 193.035 | 8.302 | 0.006 | 1.99 |

| 3-Methylhistidine | C01152 | C | 170.093 | 8.046 | 0.007 | 1.70 |

| Gluconic acid | C00257 | A | 195.051 | 8.344 | 0.017 | 1.25 |

| Threonic acid | C01620 | A | 135.030 | 9.518 | 0.020 | 1.32 |

| Pelargonic acid | C01601 | A | 157.123 | 8.331 | 0.023 | 1.14 |

| gamma-Butyrobetaine | C01181 | C | 146.118 | 8.714 | 0.024 | -1.34 |

| Asymmetric dimethylarginine | C03626 | C | 203.149 | 8.251 | 0.026 | 1.11 |

| Serine | C00065 | C | 106.050 | 10.844 | 0.028 | -1.19 |

| Histidine | C00135 | C | 156.077 | 7.824 | 0.029 | -1.11 |

| N,N-Dimethylglycine | C01026 | C | 104.071 | 11.945 | 0.032 | 1.25 |

| 1-Methylnicotinamide | C02918 | C | 137.069 | 7.882 | 0.037 | -1.57 |

| Mucic acid; Glucaric acid | C00879; C00818 | A | 209.030 | 14.658 | 0.039 | 1.77 |

| Lactic acid | C00186 | A | 89.025 | 11.226 | 0.043 | 1.23 |

| 2-Hydroxybutyric acid; 2-Hydroxyisobutyric acid | C05984; N/A | A | 103.040 | 10.084 | 0.049 | 1.22 |

A, anion mode; C, cation mode; MT, migration time; N/A, not applicable

1) P-values are calculated by Welch’s t test between RA patients and control subjects.

2) Fold changes are shown as ratio of mean value of RA patients versus that of control subjects. If the number was less than one, the negative value is shown.

Metabolites associated with DAS28-ESR

Next, we sought biomarkers that were associated with RA disease activity. We performed PCA between active (DAS28-ESR≥3.2) and inactive (DAS28-ESR<3.2) patients based on metabolic profiles in plasma and urine, but no solid separation was seen (S3 Fig). PLS-DA apparently showed a clear separation, but the result suggested overfitting (S4 Fig). Thus, we decided to search for metabolites that significantly correlated with DAS28-ESR. As a result, we found 7 and 8 metabolites that positively and negatively correlated with DAS28-ESR, respectively, in patient plasma samples (Table 3), and 16 and 4 in urine, respectively. There were no overlapping metabolites in both plasma and urine.

Table 3. Metabolites in plasma and urine of RA patients which significantly correlated with DAS28–ESR.

| Metabolite | KEGG ID | Mode | m/z | MT | Spearman ρ | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plasma | ||||||

| Glucuronic acid; Galacturonic acid | C00191; C08348 | A | 193.035 | 8.302 | 0.378 | 0.007 |

| Urea | C00086 | C | 61.041 | 24.252 | 0.376 | 0.008 |

| N,N-Dimethylglycine | C01026 | C | 104.071 | 11.945 | 0.365 | 0.010 |

| Gluconic acid | C00257 | A | 195.051 | 8.344 | 0.354 | 0.013 |

| Cysteine | C00097 | C | 122.027 | 12.045 | 0.298 | 0.038 |

| Sarcosine | C00213 | C | 90.055 | 10.268 | 0.292 | 0.042 |

| 3-Methylhistidine | C01152 | C | 170.093 | 8.046 | 0.287 | 0.046 |

| 4-Methyl-2-oxopentanoic acid; 3-Methyl-2-oxovaleric acid | C00233; C03465 | A | 129.055 | 9.865 | -0.298 | 0.038 |

| Cysteine-glutathione disulphide | N/A | C | 427.096 | 12.759 | -0.306 | 0.033 |

| Homoarginine; N6,N6,N6-Trimethyllysine | C01924; C03793 | C | 189.141 | 7.718 | -0.318 | 0.026 |

| Cysteine-glutathione disulphide -Divalent | N/A | C | 214.052 | 12.757 | -0.323 | 0.023 |

| Citric acid | C00158 | A | 191.020 | 27.938 | -0.324 | 0.023 |

| Methionine | C00073 | C | 150.059 | 11.709 | -0.361 | 0.011 |

| Guanidoacetic acid | C00581 | C | 118.062 | 8.874 | -0.400 | 0.005 |

| Histidine | C00135 | C | 156.077 | 7.824 | -0.477 | 0.001 |

| Urine | ||||||

| 2-Quinolinecarboxylic acid | C06325 | A | 172.044 | 9.215 | 0.378 | 0.008 |

| 4-Hydroxy-3-methoxymandelic acid; Syringic acid | C05584; C10833 | A | 197.047 | 8.349 | 0.360 | 0.011 |

| N-Acetylneuraminic acid | C00270 | A | 308.099 | 7.282 | 0.350 | 0.014 |

| p-Hydroxyphenylacetic acid; p-Anisic acid | C00642; C02519 | A | 151.040 | 8.898 | 0.340 | 0.017 |

| Homoserine | C00263 | C | 120.064 | 10.947 | 0.325 | 0.023 |

| Riboflavin | C00255 | C | 377.135 | 25.500 | 0.322 | 0.026 |

| 2'-Deoxycytidine | C00881 | C | 228.090 | 10.184 | 0.319 | 0.026 |

| Gibberellic acid | C01699 | A | 345.153 | 7.101 | 0.318 | 0.026 |

| 1-Methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine | C04599 | C | 174.124 | 9.769 | 0.311 | 0.030 |

| gamma-Glu-2-aminobutanoic acid | N/A | C | 233.113 | 13.643 | 0.307 | 0.032 |

| Methylguanidine | C02294 | C | 74.071 | 6.578 | 0.306 | 0.033 |

| 3-Hydroxy-3-methylglutaric acid | C03761 | A | 161.045 | 16.032 | 0.302 | 0.035 |

| Hypotaurine | C00519 | C | 110.027 | 20.735 | 0.298 | 0.038 |

| N-Acetylglucosamine 1-phosphate | C04256 | A | 300.041 | 9.910 | 0.285 | 0.047 |

| 4-Oxovaleric acid | N/A | A | 115.040 | 9.912 | 0.284 | 0.048 |

| Threonic acid | C01620 | A | 135.030 | 9.479 | 0.284 | 0.048 |

| N6,N6,N6-Trimethyllysine | C03793 | C | 189.160 | 7.636 | -0.283 | 0.049 |

| Hypoxanthine | C00262 | C | 137.046 | 12.041 | -0.304 | 0.034 |

| gamma-Butyrobetaine | C01181 | C | 146.118 | 8.695 | -0.304 | 0.034 |

| Alanine | C00041 | C | 90.056 | 9.758 | -0.310 | 0.030 |

A, anion mode; C, cation mode; MT, migration time; N/A, not applicable

Further, we compared metabolites between active and inactive patients. As shown in Table 4, 9 metabolites in plasma and 15 metabolites in urine were identified to be significantly different (Welch t-test with p<0.05) between active and inactive RA patients. Again, there were no metabolites that were detected both in plasma and urine.

Table 4. Metabolites in plasma and urine that were significantly different between active RA patients and inactive RA patients.

| Metabolite | KEGG ID | Mode | m/z | MT | P-value1) | Fold change2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active/inactive | ||||||

| Plasma | ||||||

| Histidine | C00135 | C | 156.077 | 7.824 | 0.003 | -1.13 |

| Urea | C00086 | C | 61.041 | 24.252 | 0.004 | 1.26 |

| N,N-Dimethylglycine | C01026 | C | 104.071 | 11.945 | 0.007 | 1.33 |

| Guanidoacetic acid | C00581 | C | 118.062 | 8.874 | 0.010 | -1.30 |

| Homoarginine; N6,N6,N6-Trimethyllysine | C01924; C03793 | C | 189.141 | 7.718 | 0.011 | -1.24 |

| 3-Phenylpropionic acid | C05629 | A | 149.059 | 8.998 | 0.022 | 1.44 |

| Phenylalanine | C00079 | C | 166.087 | 12.137 | 0.024 | 1.27 |

| 3-Indoxylsulfuric acid | N/A | A | 212.002 | 9.883 | 0.031 | 1.77 |

| beta-Alanine | C00099 | C | 90.055 | 7.868 | 0.049 | 1.27 |

| Urine | ||||||

| 2-Quinolinecarboxylic acid | C06325 | A | 172.044 | 9.215 | 0.002 | 3.85 |

| Gibberellic acid | C01699 | A | 345.153 | 7.101 | 0.002 | 3.52 |

| Riboflavin | C00255 | C | 377.135 | 25.500 | 0.006 | 9.95 |

| N-Acetylglucosamine 1-phosphate | C04256 | A | 300.041 | 9.910 | 0.009 | 3.10 |

| 3-Indoxylsulfuric acid | N/A | A | 212.003 | 9.821 | 0.013 | 1.74 |

| m-Hydroxybenzoic acid | C00587 | A | 137.023 | 9.555 | 0.013 | 2.50 |

| 5-Methoxyindoleacetic acid | C05660 | C | 206.077 | 25.628 | 0.017 | 2.76 |

| Hypotaurine | C00519 | C | 110.027 | 20.735 | 0.017 | 1.59 |

| Anserine; Homocarnosine | C01262; C00884 | C | 241.130 | 7.354 | 0.023 | 2.60 |

| 4-Guanidinobutyric acid | C01035 | C | 146.094 | 8.892 | 0.023 | 1.48 |

| Ophthalmic acid | N/A | C | 290.135 | 14.578 | 0.024 | 1.48 |

| Azetidine 2-carboxylic acid | C08267 | C | 102.055 | 9.568 | 0.030 | 1.72 |

| 2,6-Diaminoheptanedioic acid | C00666 | C | 191.102 | 9.574 | 0.036 | 3.09 |

| Betonicine | C08269 | C | 160.097 | 14.514 | 0.038 | 4.12 |

| 1-Methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine | C04599 | C | 174.124 | 9.769 | 0.039 | 2.08 |

A, anion mode; C, cation mode; MT, migration time; N/A, not applicable

1) P-values are calculated by Welch’s t test between active and inactive RA patients.

2) Fold changes are shown as ratio of mean value of active RA patients versus that of inactive RA patients. If the number was less than one, the negative value is shown.

Consequently, we selected 11 metabolites as biomarker candidates, which significantly correlated with DAS28-ESR, either positively or negatively, as well as those that were significantly different between active and inactive patients. The 11 metabolites were as follows: guanidoacetic acid, histidine, homoarginine or N6,N6,N6-trimethyllysine, N,N-dimethylglycine, and urea in plasma, 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine, 2-quinolinecarboxylic acid, gibberellic acid, hypotaurine, N-acetylglucosamine 1-phosphate, and riboflavin in urine.

MLR analysis

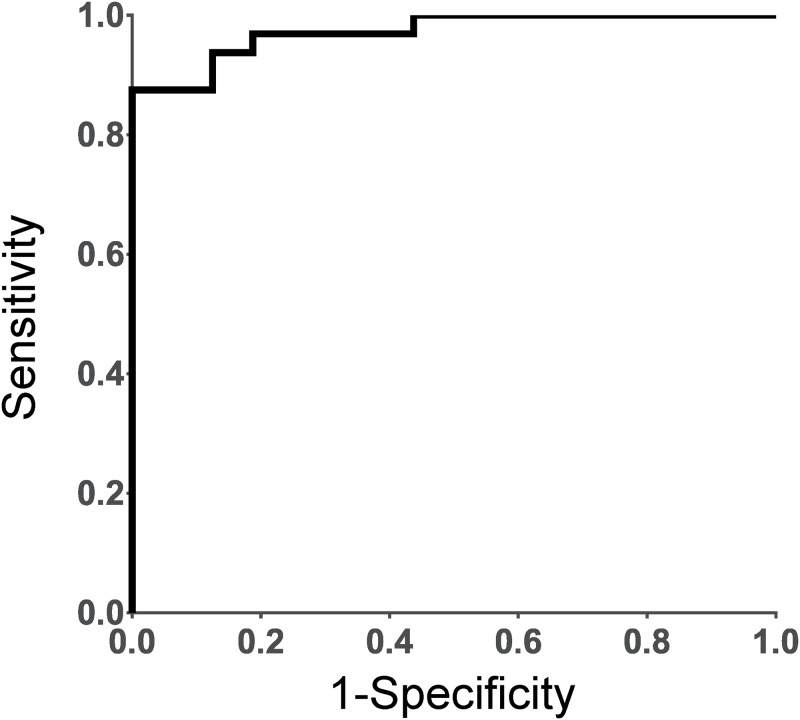

We developed MLR model to search for potential biomarkers of RA disease activity. First, we selected three metabolites, histidine and guanidoacetic acid in plasma and hypotaurine in urine, as MLR variables, which were metabolites that both correlated significantly with DAS28-ESR and significantly differed between active and inactive patients, by stepwise feature selection. Taking these three factors, the model yielded a high value of area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve (AUC = 0.8934), as shown in Fig 2. This result indicated that combining plasma and urine metabolomics analysis also identified biomarkers that correlated closely with the disease activity of RA patients.

Fig 2. ROC curve of the metabolites that correlated with DAS28-ESR and significantly differed between active and inactive patients.

The selected metabolites in this model were histidine and guanidoacetic acid in plasma and hypotaurine in urine.

Discussion

In this study, we found several candidate biomarkers of RA disease activity from metabolites in plasma and urine by the CE-Q-TOFMS method. Interestingly, only a few common metabolites were found in plasma and urine, which implied that different biomarkers could be found from the two biofluids. Indeed, we identified two metabolites in plasma, histidine and guanidoacetic acid, and one metabolite, hypotaurine, in urine, as possible biomarkers that may be closely associated with RA disease activity.

As in our study, low histidine concentration has been previously reported in RA [20–22], as well as in other diseases, such as chronic kidney disease and gallbladder inflammation with chronic cholecystitis [23, 24]. Since histidine is considered to be an anti-inflammatory and antioxidant factor [25, 26], it may be associated with the inflammation state. However, we found no other metabolites in histidine-related metabolic pathways that are associated with RA disease activity. Thus, further investigation is needed to find the underlying mechanism of how histidine level decreases in RA patients.

Guanidoacetic acid is involved in the arginine metabolism pathway. It is synthesized by the enzyme arginine:glycine amidinotransferase (AGAT) from arginine or glycine. Homoarginine is also synthesized by AGAT from arginine or lysine [27], and both guanidoacetic acid and homoarginine were inversely correlated with DAS28-ESR and decreased in active RA patients (Tables 3 and 4). In the pathway, guanidoacetic acid is then synthesized into creatine by guanidoacetic acid N-methyltransferase, which is subsequently catalyzed by creatinase to produce urea and sarcosine, both of which correlated significantly with DAS28-ESR in plasma (Table 3). These data suggest that the metabolism of arginine/glycine/lysine-guanidoacetic acid/homoarginine-urea/sarcosine pathway may be dysregulated as RA disease activity increases. Although only a few reports have reported a decrease in guanidoacetic acid level in disease, low homoarginine concentration is reported to be associated with myocardial dysfunction [28, 29] and renal failure [29, 30], and also affects the production of vasodilator nitric oxide (NO) and mineral metabolism [29]. As it is well-known that RA is sometimes comorbid with cardiovascular or renal diseases, dysregulation of the arginine metabolism pathway, represented by lower homoarginine and guanidoacetic acid in active patients, may be closely associated with the risk of these comorbidities.

Hypotaurine, another potential biomarker identified in urine, is reported to be involved in protection against oxidative stress [31]. Interestingly, we found in this study that several metabolites in the cysteine and methionine metabolism pathway, which is upstream of the taurine and hypotaurine metabolism pathway, is associated with RA disease activity. For example, cysteine and methionine in plasma positively and inversely correlated with DAS28-ESR, respectively (Table 3). Also, in urine, homoserine and gamma-glutamyl-2-aminobutyrate positively correlated with DAS28-ESR (Table 3), and ophthalmic acid was elevated in active RA patients (Table 4). These are also involved in the cysteine and methionine metabolism pathway. Furthermore, cysteine is known to be a component of the antioxidant glutathione and is involved in the transsulfuration pathway, which consists of interconversion of cysteine and homocysteine through the intermediate cystathionine [32]. Since some of the intermediates in this pathway correlate with DAS28-ESR, our study strongly suggests that the reverse transsulfuration pathway is actively induced as RA disease activity increases. Hydrogen sulfide (H2S), which is also produced from cysteine, is known as a signaling molecule that regulates the physiological process in inflammations [33, 34], and is reported to be increased in synovial fluids in RA patients [35]. Therefore, some pathways downstream of cysteine might be activated and the increase in urinary hypotaurine may represent these metabolic changes in active RA disease.

Taken together, we were able to discover the metabolites from plasma and urine that could be a combinatorial biomarker for RA. This finding supports the use of metabolomics analysis as a promising way to search for disease biomarkers, and to obtain deep insights into the disease pathophysiology, especially with multiple fluid/tissue samples. Metabolomics in combination with other omics methods, such as transcriptomics and proteomics, and the combination of the information obtained with that of other diseases would be beneficial for the better understanding of the state and course of individual RA patients such as with regard to the risk of comorbidity. However, confirming the validity of the biomarker candidates and the significance of the metabolic pathway in RA pathophysiology found in this study requires further study with a new and different set of samples and a larger sample size. We should also confirm whether or not the candidates were specific for RA, because we could not exclude the possibility that the metabolites correlated with the general inflammation process.

Conclusions

We employed metabolic profiling using the CE-Q-TOFMS method to identify metabolites that were associated with disease activity in plasma and urine of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. As a result, we generated a list of metabolites that correlated significantly with DAS28-ESR, as well as metabolites that significantly differed between patients with active and inactive RA. Using both lists, three metabolites—histidine and guanidoacetic acid in plasma and hypotaurine in urine—were selected as MLR variables. Thus, this study demonstrates that the combination of metabolomics analysis of both plasma and urine samples is a useful approach to predicting biomarkers for RA and obtaining deep insights into the pathophysiology of this disease.

Supporting information

(XLSX)

The green and red dots represent RA patient and control samples, respectively.

(TIF)

The p value was p = 0.022 (22/1000).

(TIF)

The red and green dots represent samples of active patients (DAS28-ESR≥3.2) and inactive patients (DAS28-ESR<3.2), respectively.

(TIF)

The red and green dots represent samples of active patients (DAS28-ESR≥3.2) and inactive patients (DAS28-ESR<3.2), respectively. R2 = 0.95405 and Q2 = 0.12656 indicate that the model was overfitted.

(TIF)

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Moritoshi Furu for his useful discussions. We also thank Rie Yamamoto for quality checking the data.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

This work was supported in part by the Special Coordination Funds for Promoting Science and Technology of the Japanese Government and in part by Astellas Pharma Inc. in the Formation of Innovation Center for Fusion of Advanced Technologies Program.

References

- 1.Aletaha D, Neogi T, Silman AJ, Funovits J, Felson DT, Bingham CO 3rd, et al. 2010 Rheumatoid arthritis classification criteria: an American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62(9):2569–2581. 10.1002/art.27584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smolen JS, Aletaha D, McInnes IB. Rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet. 2016;388(10055):2023–2038. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30173-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deane KD, Demoruelle MK, Kelmenson LB, Kuhn KA, Norris JM, Holers VM. Genetic and environmental risk factors for rheumatoid arthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2017;31(1):3–18. 10.1016/j.berh.2017.08.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu Y, Aryee MJ, Padyukov L, Fallin MD, Hesselberg E, Runarsson A, et al. Epigenome-wide association data implicate DNA methylation as an intermediary of genetic risk in rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31(2):142–147. 10.1038/nbt.2487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stahl EA, Raychaudhuri S, Remmers EF, Xie G, Eyre S, Thomson BP, et al. Genome-wide association study meta-analysis identifies seven new rheumatoid arthritis risk loci. Nat Genet. 2010;42(6):508–514. 10.1038/ng.582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Okada Y, Wu D, Trynka G, Raj T, Terao C, Ikari K, et al. Genetics of rheumatoid arthritis contributes to biology and drug discovery. Nature. 2014;506(7488):376–381. 10.1038/nature12873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Viatte S, Massey J, Bowes J, Duffus K, Eyre S, Barton A, et al. Replication of Associations of Genetic Loci Outside the HLA Region With Susceptibility to Anti-Cyclic Citrullinated Peptide-Negative Rheumatoid Arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68(7):1603–1613. 10.1002/art.39619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Malmstrom V, Catrina AI, Klareskog L. The immunopathogenesis of seropositive rheumatoid arthritis: from triggering to targeting. Nat Rev Immunol. 2017;17(1):60–75. 10.1038/nri.2016.124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smolen JS, Aletaha D. Rheumatoid arthritis therapy reappraisal: strategies, opportunities and challenges. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2015;11(5):276–289. 10.1038/nrrheum.2015.8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Surowiec I, Arlestig L, Rantapaa-Dahlqvist S, Trygg J. Metabolite and Lipid Profiling of Biobank Plasma Samples Collected Prior to Onset of Rheumatoid Arthritis. PLoS One. 2016;11(10):e0164196 10.1371/journal.pone.0164196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zheng K, Shen N, Chen H, Ni S, Zhang T, Hu M, et al. Global and targeted metabolomics of synovial fluid discovers special osteoarthritis metabolites. J Orthop Res. 2017;35(9):1973–1981. 10.1002/jor.23482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li J, Che N, Xu L, Zhang Q, Wang Q, Tan W, et al. LC-MS-based serum metabolomics reveals a distinctive signature in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2018;37(6):1493–1502. 10.1007/s10067-018-4021-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cuppen BV, Fu J, van Wietmarschen HA, Harms AC, Koval S, Marijnissen AC, et al. Exploring the Inflammatory Metabolomic Profile to Predict Response to TNF-alpha Inhibitors in Rheumatoid Arthritis. PLoS One. 2016;11(9):e0163087 10.1371/journal.pone.0163087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhou J, Chen J, Hu C, Xie Z, Li H, Wei S, et al. Exploration of the serum metabolite signature in patients with rheumatoid arthritis using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2016;127:60–67. 10.1016/j.jpba.2016.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ramautar R, Somsen GW, de Jong GJ. CE-MS for metabolomics: Developments and applications in the period 2014–2016. Electrophoresis. 2017;38(1):190–202. 10.1002/elps.201600370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hirayama A, Tomita M, Soga T. Sheathless capillary electrophoresis-mass spectrometry with a high-sensitivity porous sprayer for cationic metabolome analysis. Analyst. 2012;137(21):5026–5033. 10.1039/c2an35492f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kami K, Fujimori T, Sato H, Sato M, Yamamoto H, Ohashi Y, et al. Metabolomic profiling of lung and prostate tumor tissues by capillary electrophoresis time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Metabolomics. 2013;9(2):444–453. 10.1007/s11306-012-0452-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sugimoto M, Wong DT, Hirayama A, Soga T, Tomita M. Capillary electrophoresis mass spectrometry-based saliva metabolomics identified oral, breast and pancreatic cancer-specific profiles. Metabolomics. 2010;6(1):78–95. 10.1007/s11306-009-0178-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chong J, Soufan O, Li C, Caraus I, Li S, Bourque G, et al. MetaboAnalyst 4.0: towards more transparent and integrative metabolomics analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46(W1):W486–w494. 10.1093/nar/gky310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Madsen RK, Lundstedt T, Gabrielsson J, Sennbro CJ, Alenius GM, Moritz T, et al. Diagnostic properties of metabolic perturbations in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2011;13(1):R19 10.1186/ar3243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smolenska Z, Smolenski RT, Zdrojewski Z. Plasma concentrations of amino acid and nicotinamide metabolites in rheumatoid arthritis—potential biomarkers of disease activity and drug treatment. Biomarkers. 2016;21(3):218–224. 10.3109/1354750X.2015.1130746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gerber DA. Low free serum histidine concentration in rheumatoid arthritis. A measure of disease activity. J Clin Invest. 1975;55(6):1164–1173. 10.1172/JCI108033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Watanabe M, Suliman ME, Qureshi AR, Garcia-Lopez E, Barany P, Heimburger O, et al. Consequences of low plasma histidine in chronic kidney disease patients: associations with inflammation, oxidative stress, and mortality. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87(6):1860–1866. 10.1093/ajcn/87.6.1860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sharma RK, Mishra K, Farooqui A, Behari A, Kapoor VK, Sinha N. (1)H nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR)-based serum metabolomics of human gallbladder inflammation. Inflamm Res. 2017;66(1):97–105. 10.1007/s00011-016-0998-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pisarenko OI. Mechanisms of myocardial protection by amino acids: facts and hypotheses. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 1996;23(8):627–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wade A.M., Tucker H.N. Antioxidant characteristics of L-histidine. J Nutr Biochem 1998;9(6):308–315. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Davids M, Ndika JD, Salomons GS, Blom HJ, Teerlink T. Promiscuous activity of arginine:glycine amidinotransferase is responsible for the synthesis of the novel cardiovascular risk factor homoarginine. FEBS Lett. 2012;586(20):3653–3657. 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.08.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pilz S, Meinitzer A, Tomaschitz A, Drechsler C, Ritz E, Krane V, et al. Low homoarginine concentration is a novel risk factor for heart disease. Heart. 2011;97(15):1222–1227. 10.1136/hrt.2010.220731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pilz S, Meinitzer A, Gaksch M, Grubler M, Verheyen N, Drechsler C, et al. Homoarginine in the renal and cardiovascular systems. Amino Acids. 2015;47(9):1703–1713. 10.1007/s00726-015-1993-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Drechsler C, Kollerits B, Meinitzer A, Marz W, Ritz E, Konig P, et al. Homoarginine and progression of chronic kidney disease: results from the Mild to Moderate Kidney Disease Study. PLoS One. 2013;8(5):e63560 10.1371/journal.pone.0063560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aruoma OI, Halliwell B, Hoey BM, Butler J. The antioxidant action of taurine, hypotaurine and their metabolic precursors. Biochem J. 1988;256(1):251–255. 10.1042/bj2560251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stipanuk MH. Metabolism of sulfur-containing amino acids. Annu Rev Nutr. 1986;6:179–209. 10.1146/annurev.nu.06.070186.001143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sbodio JI, Snyder SH, Paul BD. Golgi stress response reprograms cysteine metabolism to confer cytoprotection in Huntington’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115(4):780–785. 10.1073/pnas.1717877115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kabil O, Yadav V, Banerjee R. Heme-dependent Metabolite Switching Regulates H2S Synthesis in Response to Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER) Stress. J Biol Chem. 2016;291(32):16418–16423. 10.1074/jbc.C116.742213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Muniraj N, Stamp LK, Badiei A, Hegde A, Cameron V, Bhatia M. Hydrogen sulfide acts as a pro-inflammatory mediator in rheumatic disease. Int J Rheum Dis. 2017;20(2):182–189. 10.1111/1756-185X.12472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(XLSX)

The green and red dots represent RA patient and control samples, respectively.

(TIF)

The p value was p = 0.022 (22/1000).

(TIF)

The red and green dots represent samples of active patients (DAS28-ESR≥3.2) and inactive patients (DAS28-ESR<3.2), respectively.

(TIF)

The red and green dots represent samples of active patients (DAS28-ESR≥3.2) and inactive patients (DAS28-ESR<3.2), respectively. R2 = 0.95405 and Q2 = 0.12656 indicate that the model was overfitted.

(TIF)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting Information files.