Abstract

Background/Aims

Little evidence is available about the effect of change in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) status on risk of diabetes mellitus (DM) development. In this study, we tried to analyze the DM risk according to change in NAFLD status over time.

Methods

Among a total of 10,141 individuals for whom routine healthcare assessment was performed, 2,726 subjects were selected according to the inclusion/exclusion criteria. NAFLD status change was determined by using serial abdominal ultrasonography and fatty liver index (FLI) during the follow-up period.

Results

Subjects were categorized according to change in NAFLD status as follows: 670 subjects in the persistent NAFLD group, 155 subjects in the resolved NAFLD group, 498 subjects in the incident NAFLD group, and 1,403 subjects in the no NAFLD group. Multivariate Cox regression analysis revealed that incident NAFLD (hazard ratio [HR], 1.94; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.08 to 3.50; p=0.026) and persistent NAFLD (HR, 3.59; 95% CI, 2.05 to 6.27; p<0.001) were independent risk factors for predicting DM development, whereas the risk with resolved NAFLD was not significantly different from that with no NAFLD. FLI could reproduce the results acquired by ultrasonography.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated that future DM risk could be influenced by changes in NAFLD status over time. Resolution of NAFLD could reduce the risk of future DM development, while the development of new NAFLD could increase the risk of DM development.

Keywords: Diabetes mellitus, type 2, Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, Fatty liver, Ultrasonography, Obesity

INTRODUCTION

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is a prominent cause of chronic liver disease.1,2 Recently, the prevalence of NAFLD has increased dramatically worldwide, making it a major cause of liver-related morbidity and mortality.2 Beyond the concerns associated with its involvement in liver diseases, NAFLD has also been highlighted as a hepatic manifestation of metabolic disease.3,4 In-depth insight into the role of NAFLD in the progress of metabolic diseases would be helpful to manage the metabolic risk of the patients with NAFLD.

Among the metabolic diseases, diabetes mellitus (DM) is particularly a major medical concern of the 21st century. It is the one of the most important risk factors of cardiovascular disease and is the seventh leading cause of death in Western counties, affecting more than 10% of the adult population.5,6 Growing evidence suggests that NAFLD is strongly associated with type 2 DM. Several epidemiologic studies have shown that NAFLD detected by ultrasonography (US) could predict the development of incident DM.7–10 Previous studies showed that individuals with NAFLD were at a higher risk of developing DM than those without NAFLD.11,12 Actually, the factors affecting liver fat accumulation substantially overlap with the risk factors of DM; therefore, the strong positive correlation between NAFLD and DM is not surprising.

However, there is limited evidence about the effect on risk of DM development according to change in NAFLD status over time (e.g., NAFLD development or resolution). Few cross-sectional studies have been performed to identify the relationship between changing NAFLD status and the incident DM risk.13,14 However, it remains unclear whether a change in NAFLD status over time could modify risk of future DM development. To identify the causality between change in NAFLD status and risk of future DM development more precisely, well-designed longitudinal studies are warranted.

The aim of this study was to evaluate whether the resolution of or development of new NAFLD could affect the risk of future DM development compared to persistent NAFLD by analyzing 10-year follow-up results of routine healthcare assessment data.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

1. Study population

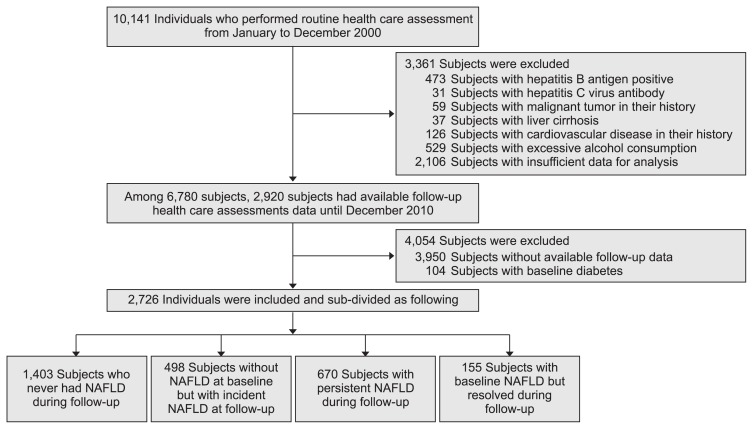

This retrospective study was conducted at the Health Promotion Center of the Ajou University Hospital, Suwon, South Korea. A total of 10,141 subjects for whom routine healthcare assessments were performed from January to December 2000 were reviewed, and the subjects who met any of the following exclusion criteria were excluded: hepatitis B antigen-positive, hepatitis C virus antibody-positive, history of any malignancies, presence of liver cirrhosis, excessive alcohol consumption (a threshold of 20 g/day for women and 30 g/day for men), DM history, and insufficient data for analysis. Among the remaining subjects after exclusion, only those who underwent follow-up abdominal US twice or more with available follow-up health-care assessment data until December 2010 were included. Some of the included subjects were followed up regularly, while some of them were not. Finally, a total of 2,726 subjects without baseline DM were included and analyzed (Fig. 1). The design and procedure of the present study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Ajou University Hospital, Suwon, South Korea (AJRIB-MED-OBS-16-287). The informed consent was waived.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart for subject inclusion.

NAFLD, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease.

2. Definition of terms

The diagnosis of NAFLD was based on the following criteria: (1) the evidence of steatosis using abdominal US, (2) exclusion of other causes of liver fat accumulation, such as significant alcohol consumption (20 g/day for women and 30 g/day for men), medications or hereditary disorders.15,16 The evidence of hepatic steatosis was confirmed when the liver displayed fine and bright echogenicity compared with that of the kidney on abdominal US.17,18

The included subjects were followed up until DM development. The subjects were categorized according to changes in NAFLD status over time during the follow-up period as follows: those who never had NAFLD during the follow-up period were categorized into the “no NAFLD group,” those without NAFLD at baseline but with newly developed NAFLD on follow-up examination were categorized into the “incident NAFLD group,” those with NAFLD at baseline and during follow-up period were categorized into the “persistent NAFLD group,” and those with NAFLD at baseline but which resolved during following examination were assumed as the “resolved NAFLD group.” Subjects were monitored for DM development during follow-up. The subjects who had fluctuation in NAFLD status were categorized according to NAFLD status of the first and last examination.

The included subjects were further divided according to body mass index (BMI) change for subgroup analysis. The subjects with increase BMI during follow-up were categorized into increased BMI group, while the subjects with decreased BMI during follow-up were categorized into decreased BMI group.

Diagnosis of DM was defined as fasting plasma glucose levels ≥126 mg/dL or hemoglobin A1c levels ≥6.5%.19 In addition, the subjects who reported taking antidiabetic medications in a self-reported health survey were also presumed to have DM. Hypertension was diagnosed using the following cutoff values of blood pressure: ≥140 mm Hg/≥90 mm Hg, or the subjects who reported taking antihypertensive medications in a self-reported health survey were also presumed to have hypertension.

In this study, NAFLD status by fatty liver index (FLI) was additionally analyzed to check whether NAFLD status determined by another noninvasive marker could reproduce our results. FLI is a noninvasive marker based on four simple parameters, including BMI, waist circumference (WC), triglyceride (TG), and gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT), with a satisfactory range of performance for NAFLD diagnosis.20 It was calculated according to the following formula: FLI=eL/(1+eL)×100, where L=0.953×loge TG (mg/dL) + 0.139×BMI (kg/m2) + 0.718×loge GGT (U/L) + 0.053×WC (cm) − 15.745.20 The cutoff value of FLI to diagnose NAFLD was ≥35 for men and ≥20 for women, which has been proposed for Asian subjects in several previous studies.21,22

3. Anthropometric and laboratory evaluation

BMI was calculated as body weight (kg) divided by the square of the height (m), expressed in kg/m2. WC was measured midway between the lower rib margin and iliac crest with a measuring tape.23 The cutoff values for high WC were 80 cm for women, and 90 cm for men according to the definition of central obesity in the Asian-Pacific area.24

The value of baseline and follow-up serum aspartate transaminase, alanine transaminase (ALT), uric acid levels, fasting plasma glucose, total cholesterol, TG, high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol were collected. All laboratory markers were measured using a conventional automated analyzer.

4. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 19.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and R software package R version 3.2.5 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria; http://www.R-project.org/). Kaplan-Meier analysis was performed to compare the risk of incident diabetes development between the groups. Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses were performed to identify the risk factors associated with DM. The results are presented as hazard ratios (HR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Harrell’s C-index was analyzed to assess the discriminatory power of the Cox models. The best model for predicting future DM risk was selected by considering the principle of parsimony and the discriminatory power of each model. For these exploratory analyses, a value of p<0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

1. Baseline characteristics of the subjects

A total of 2,726 subjects were included in this study. The baseline characteristics of the subjects are presented in Table 1. The subjects comprised 1,571 men (57.6%) and 1,155 women (42.4%) aged 44.2±9.3 years. The median follow-up period was 62.2 months (range, 12.0 to 135.0 months). Among the 2,726 subjects, 825 subjects (30.3%) had NAFLD at baseline, and 1,901 subjects (69.7%) did not have NAFLD. The subjects were further divided according to the changes in the NAFLD status over time. Among 825 subjects with NAFLD at baseline, 155 (5.7%) and 670 (24.6%) were subdivided into the resolved NAFLD and persistent NAFLD groups, respectively. Among 1,901 subjects without NAFLD, 498 (18.3%) and 1,403 (51.5%) were subdivided into the incident NAFLD and no NAFLD groups, respectively. In the case of incident NAFLD, the median duration of NAFLD development was 37.0 months (range, 12.1 to 132.4 months).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of the Cohort According to Stratification by Fatty Liver Development

| Variable | All included patients | Fatty liver status | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| No NAFLD | Incident NAFLD | Resolved NAFLD | Persistent NAFLD | p-value* | ||

| No. of patients | 2,726 | 1,403 (51.5) | 498 (18.3) | 155 (5.7) | 670 (24.6) | |

| Age, yr | 44.2±9.3 | 42.9±9.4 | 44.3±8.9 | 46.4±9.8 | 46.3±8.9 | <0.001 |

| Male sex | 1,571 (57.6) | 648 (44.6) | 343 (67.9) | 87 (55.4) | 542 (77.2) | <0.001 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 23.3±2.8 | 22.0±2.4 | 23.5±2.4 | 24.5±2.4 | 25.6±2.5 | <0.001 |

| Waist circumference, cm | 80.2±9.5 | 75.6±8.1 | 81.6±7.8 | 83.2±7.5 | 88.2±7.8 | <0.001 |

| SBP, mm Hg | 120.0±16.3 | 115.8±15.3 | 121.7±15.7 | 124.7±16.2 | 126.2±16.2 | <0.001 |

| DBP, mm Hg | 74.5±11.0 | 71.8±10.2 | 75.5±11.1 | 77.7±11.2 | 78.6±10.8 | <0.001 |

| Fasting glucose, mg/dL | 97.0±13.1 | 93.9±10.0 | 97.7±15.1 | 97.4±9.2 | 103.0±15.6 | <0.001 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 190.2±34.6 | 183.0±33.1 | 189.5±33.3 | 199.6±35.6 | 204.2±33.7 | <0.001 |

| Triglyceride, mg/dL | 133.2±91.2 | 100.2±58.3 | 141.6±96.0 | 159.1±98.7 | 191.6±112.1 | <0.001 |

| HDL cholesterol, mg/dL | 51.2±12.0 | 54.5±12.3 | 49.3±11.1 | 49.9±12.2 | 45.9±9.2 | <0.001 |

| LDL cholesterol, mg/dL | 112.4±31.0 | 108.1±29.4 | 111.9±31.3 | 117.9±30.9 | 120.3±32.3 | <0.001 |

| AST, U/L | 25.2±12.5 | 23.1±11.6 | 25.0±9.6 | 26.2±10.7 | 29.5±15.1 | <0.001 |

| ALT, U/L | 28.6±26.5 | 22.2±15.9 | 27.5±14.2 | 31.7±20.5 | 42.2±42.6 | <0.001 |

| ALT (≥19 U/L for women, ≥30 U/L for men) | 1,218 (44.7) | 447 (31.9) | 216 (43.4) | 87 (56.1) | 468 (69.9) | <0.001 |

| GGT, U/L | 31.4±32.2 | 22.5±20.3 | 33.8±33.8 | 37.8±48.9 | 47.0±40.4 | <0.001 |

| Uric acid, mg/dL | 5.3±4.8 | 4.9±5.6 | 5.5±6.2 | 5.2±1.4 | 5.9±1.4 | <0.001 |

| Current smoker | 852 (31.3) | 350 (26.7) | 200 (42.3) | 36 (25.7) | 266 (31.2) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 142 (5.2) | 37 (2.6) | 28 (5.9) | 13 (8.3) | 64 (9.6) | <0.001 |

| DM development | 141 (5.2) | 23 (1.6) | 5 (3.2) | 33 (6.6) | 80 (11.9) | <0.001 |

Data are presented as number (%) or mean±SD.

NAFLD, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease; BMI, body mass index; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; GGT, gamma-glutamyltransferase; DM, diabetes mellitus.

p-value using Bonferroni as the post hoc analysis for comparing the groups divided by change in NAFLD status over time.

The persistent NAFLD group was more likely to be male-dominant and have individuals who were advanced in age, were current smokers, and had hypertension at baseline. The persistent NAFLD group showed higher BMI, WC, fasting plasma glucose, total cholesterol, TG, LDL cholesterol, aspartate transaminase, ALT, GGT, and uric acid levels than other groups.

2. Risk comparison of DM development according to baseline NAFLD status or change in NAFLD status over time

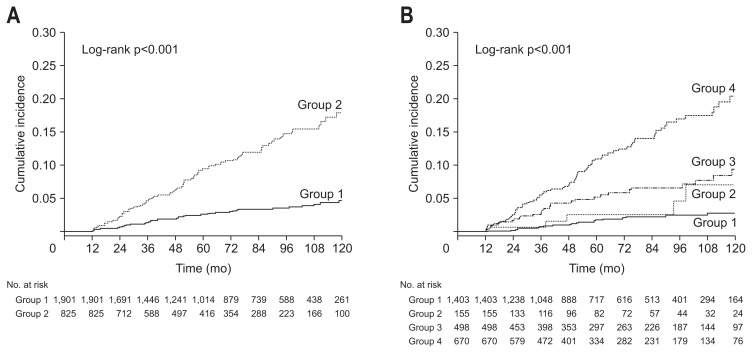

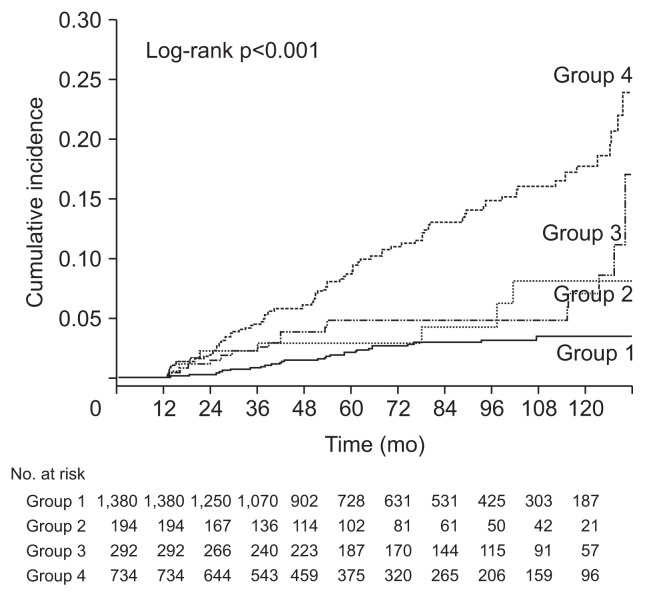

Among the included subjects, 141 (5.2%) were diagnosed with incident DM during follow-up. The cumulative risk of DM development was compared according to the baseline NAFLD status. Subjects with baseline NAFLD showed a significantly higher risk of future DM development than those without baseline NAFLD (Fig. 2A). Subjects without baseline NAFLD were subdivided into incident NAFLD and no NAFLD groups, while those with baseline NAFLD were subdivided into the persistent NAFLD and resolved NAFLD groups (Fig. 2B). The risk of DM development was significantly higher in the persistent NAFLD group than in incident NAFLD and resolved NAFLD groups, whereas the no NAFLD group showed the lowest DM risk among the groups. However, there were no significant differences in the risk of DM development between the resolved NAFLD and no NAFLD groups (p=0.167) or between the resolved NAFLD and incident NAFLD groups (p=0.208).

Fig. 2.

Comparison of diabetes mellitus (DM) incidence according to nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) status. (A) Kaplan-Meier curves of DM development according to baseline NAFLD status (group 1, subjects without baseline NAFLD; group 2, subjects with baseline NAFLD). (B) Kaplan-Meier curves of DM development between the groups categorized by change in NAFLD status over time (group 1, subjects who had no NAFLD; group 2, subjects with resolved NAFLD; group 3, subjects with incident NAFLD; and group 4, subjects with persistent NAFLD).

3. Risk factors for incidence of DM and correlation with NAFLD status change in US over time

Cox regression analyses were performed to identify the risk factors for incident DM. In univariate analysis, old age, male sex, higher WC, high BMI, high fasting glucose, low HDL cholesterol, high LDL, higher uric acid (>6 mg/dL), underlying hypertension, higher ALT (≥19 U/L for women, ≥30 U/L for men), higher GGT (>60 U/L), changes in obesity status (normal to obese, obese to normal), incident NAFLD and persistent NAFLD were identified as significant risk factors for predicting DM development. Multivariate Cox regression analyses were performed by entering various combinations of the variables by considering clinical significances and the result of univariate analysis. Incident NAFLD and persistent NAFLD remained as independent risk factors for predicting incident DM development after adjusting for various confounding factors (Table 2). Considering the principle of parsimony and Harrell’s C-index of each model, model 2 among the derived models was selected as the best predictive model for DM development. Consequently, in addition to incident NAFLD and persistent NAFLD (hazard ratio [HR], 1.94; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.08 to 3.50; p=0.026) and persistent NAFLD (HR, 3.59; 95% CI, 2.05 to 6.27; p<0.001), higher fasting plasma glucose level (HR, 1.03; 95% CI, 1.03 to 1.03; p<0.001), and higher ALT level (≥19 U/L for women, ≥30 U/L for men: HR, 1.63; 95% CI, 1.10 to 2.41; p=0.015) were identified as the independent risk factors for predicting incident DM development. The risk of DM development of the resolved NAFLD group was not significantly different with that of the no NAFLD group.

Table 2.

Univariate and Multivariate Cox Regression Analysis to Identify the Risk Factors of Incident Diabetes Mellitus, Including NAFLD Status Change Over Time as Determined by Ultrasonography

| Variable | Univariate analysis | Multivariate model 1 | Model 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||

| HR (95% CI) | p-value | HR (95% CI) | p-value | HR (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Age | 1.04 (1.03–1.06) | <0.001 | 1.02 (1.00–1.04) | 0.123 | 1.02 (1.00–1.04) | 0.039 |

| Male sex | 1.86 (1.28–2.70) | 0.001 | 0.69 (0.41–1.16) | 0.162 | 0.79 (0.50–1.26) | 0.324 |

| NAFLD status overtime | ||||||

| No NAFLD | 1 (Reference) | |||||

| Resolved NAFLD | 1.95 (0.74–5.12) | 0.177 | 1.22 (0.41–3.60) | 0.726 | 1.21 (0.41–3.57) | 0.733 |

| Incident NAFLD | 3.50 (2.05–5.96) | <0.001 | 2.39 (1.31–4.37) | 0.005 | 1.94 (1.08–3.50) | 0.026 |

| Persistent NAFLD | 7.49 (4.71–11.91) | <0.001 | 4.30 (2.41–7.68) | <0.001 | 3.59 (2.05–6.27) | <0.001 |

| Waist circumference (>80 cm for women, >90 cm for men) | 3.35 (2.41–4.66) | <0.001 | 1.07 (0.64–1.78) | 0.803 | ||

| BMI, kg/m2 | 1.23 (1.17–1.29) | <0.001 | 1.10 (0.99–1.21) | 0.063 | 1.06 (0.99–1.14) | 0.076 |

| Fasting glucose, mg/dL | 1.03 (1.03–1.03) | <0.001 | 1.03 (1.03–1.04) | <0.001 | 1.03 (1.03–1.03) | <0.001 |

| HDL cholesterol, mg/dL | 0.97 (0.69–0.99) | <0.001 | 1.01 (0.99–1.03) | 0.547 | ||

| LDL cholesterol, mg/dL | 1.01 (1.00–1.01) | <0.001 | 1.00 (1.00–1.01) | 0.878 | ||

| Uric acid (>6 mg/dL) | 1.56 (1.12–2.19) | 0.010 | 1.15 (0.76–1.74) | 0.523 | ||

| Current smoker | 1.36 (0.96–1.92) | 0.081 | 1.60 (1.03–2.47) | 0.036 | ||

| Hypertension | 1.91 (1.08–3.39) | 0.026 | 1.04 (0.55–1.98) | 0.902 | ||

| ALT (≥19 U/L for women & ≥30 U/L for men) | 2.28 (1.63–3.21) | <0.001 | 1.33 (0.89–2.00) | 0.160 | 1.63 (1.10–2.41) | 0.015 |

| GGT (>60 U/L) | 2.39 (1.57–3.64) | <0.001 | 0.99 (0.60–1.63) | 0.975 | ||

| Changes in obesity status | ||||||

| Normal to normal | 1 (Reference) | |||||

| Normal to obesity | 0.56 (0.35–0.90) | 0.017 | 2.48 (1.26–4.89) | 0.009 | ||

| Obesity to normal | 2.27 (1.36–3.78) | 0.02 | 1.42 (0.76–2.67) | 0.271 | ||

| Obesity to obesity | 1.59 (0.95–2.64) | 0.77 | 1.32 (0.78–2.23) | 0.301 | ||

Harrell’s C index; model 1: 0.857 (standard error estimates=0.026), model 2: 0.860 (standard error estimates=0.027).

NAFLD, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; BMI, body mass index; HDL, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; ALT, alanine transaminase; GGT, gamma-glutamyltransferase.

4. Subgroup analysis according to baseline BMI and BMI change

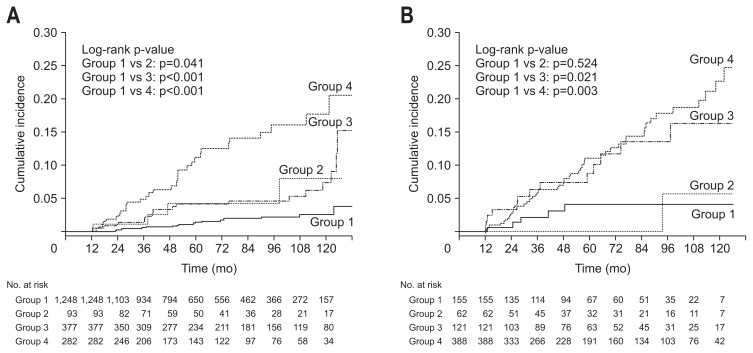

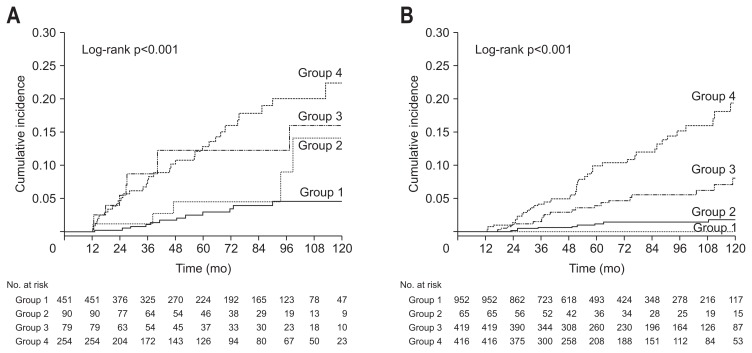

Subgroup analyses were performed to identify whether a change in the NAFLD status could influence DM development regardless of the baseline obesity status or BMI change. Subjects with baseline BMI <25 kg/m2 were categorized into the nonobese group (n=2,000), while those with baseline BMI ≥25 kg/m2 were categorized into the obese group (n=726). Subjects were also categorized by changes in BMI. Overall, 1,852 subjects had increased BMI and 874 had decreased BMI during follow-up. The results of subgroup analyses were are shown in Figs 3, 4 and Table 3. The results showed that changes in the NAFLD status influenced future DM risk more significantly in the non-obese group than in the obese group. The change in the NAFLD status was revealed as an independent predictor of future DM development regardless of BMI change.

Fig. 3.

Comparison of cumulative diabetes mellitus (DM) risk according to change in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) status in both the nonobese group and obese group. (A) Kaplan-Meier curves of DM development according to NAFLD status change in nonobese subjects. (B) Kaplan-Meier curves of DM development according to NAFLD status change in obese subjects. Group 1, subjects who had no NAFLD; group 2, subjects with resolved NAFLD; group 3, subjects with incident NAFLD; and group 4, subjects with persistent NAFLD.

Fig. 4.

Comparison of cumulative diabetes mellitus (DM) risk according to change in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) status according to body mass index (BMI) change. (A) Kaplan-Meier curves of DM development according to NAFLD status change in subjects with decreased BMI. (B) Kaplan-Meier curves of DM development according to NAFLD status change in subjects with increased BMI. Group 1, subjects who had no NAFLD; group 2, subjects with resolved NAFLD; group 3, subjects with incident NAFLD; and group 4, subjects with persistent NAFLD.

Table 3.

Multivariate Cox Regression Analyses to Identify the Risk Factors of Incident Diabetes Mellitus in Subgroups Divided by Baseline BMI and BMI Change Over Time

| NAFLD status overtime | Baseline obesity | BMI change | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||

| Nonobese group (n=2,000) | Obese group (n=726) | Decreased BMI (n=874) | Increased BMI (n=1,852) | |||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

| HR (95% CI) | p-value | HR (95% CI) | p-value | HR (95% CI) | p-value | HR (95% CI) | p-value | |

| No NAFLD | 1 (Reference) | |||||||

| Resolved NAFLD | 1.87 (0.53–6.54) | 0.330 | 0.493 (0.06–4.24) | 0.519 | 1.38 (0.44–4.35) | 0.579 | 1.75 (0.42–7.36) | 0.412 |

| Incident NAFLD | 2.51 (1.27–4.95) | 0.008 | 1.73 (0.57–5.27) | 0.333 | 2.68 (1.08–6.65) | 0.034 | 2.41 (1.12–5.20) | 0.025 |

| Persistent NAFLD | 4.78 (2.45–9.35) | <0.001 | 2.71 (1.04–7.09) | 0.042 | 2.18 (1.03–4.62) | 0.042 | 5.51 (2.55–11.91) | <0.001 |

Adjusted for age, sex, fasting glucose, body mass index (BMI), waist circumference, and baseline alanine transaminase levels.

HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; NAFLD, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease.

5. Analysis for the incident DM risk according to the over time changes in the NAFLD status determined by FLI

Fig. 5 shows Kaplan-Meier curves for a comparison of the incident DM risk between groups divided by NAFLD status changes which were assessed over time by FLI. According to the FLI findings, the persistent NAFLD groups showed the highest risk for incident DM development followed by incident NAFLD, resolved NAFLD, and no NAFLD groups. However, the FLI findings of the resolved NAFLD group did not differ significantly from those of the no NAFLD or incident NAFLD group. Table 4 shows HRs for DM development according to changes in the NAFLD status as assessed by FLI. Consequently, incident NAFLD and persistent NAFLD were independent risk factors for predicting incident DM development after adjusting for various confounding factors.

Fig. 5.

Comparison of diabetes mellitus development by Kaplan-Meier curves in included subjects according to groups divided by change in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) status as assessed by fatty liver index (FLI). Group 1, subjects who had no NAFLD assessed by FLI; group 2, subjects with resolved NAFLD assessed by FLI; group 3, subjects with incident NAFLD assessed by FLI; and group 4, subjects with persistent NAFLD assessed by FLI.

Table 4.

Univariate and Multivariate Cox Regression Analysis to Identify the Risk Factors of Incident Diabetes Mellitus, Including NAFLD Status Change Over Time as Assessed by Fatty Liver Index

| NAFLD status overtime | Univariate analysis | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

| HR (95% CI) | p-value | HR (95% CI) | p-value | HR (95% CI) | p-value | HR (95% CI) | p-value | |

| No NAFLD | 1 (Reference) | |||||||

| Resolved NAFLD | 2.08 (0.95–4.53) | 0.066 | 1.61 (0.73–3.55) | 0.236 | 0.378 (0.14–1.01) | 0.052 | 0.44 (0.16–1.20) | 0.108 |

| Incident NAFLD | 2.34 (1.29–4.25) | 0.005 | 2.35 (1.30–4.26) | 0.005 | 2.03 (1.11–3.71) | 0.021 | 2.31 (1.22–4.36) | 0.010 |

| Persistent NAFLD | 5.41 (3.57–8.21) | <0.001 | 4.56 (2.99–6.97) | <0.001 | 2.29 (1.33–3.96) | 0.003 | 2.32 (1.30–4.12) | 0.004 |

Model 1: adjusted for age and sex; model 2: adjusted for variables of model 1 and fasting glucose, body mass index, and waist circumference; model 3: adjusted for variables of model 2 and current smoking, hypertension status, baseline alanine transaminase levels, and changes in obesity status. Harrell’s C index; model 1: 0.739 (standard error estimates=0.026), model 2: 0.846 (standard error estimates=0.026), model 3: 0.850 (standard error estimates=0.027).

NAFLD, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval.

DISCUSSION

Considerable basic and clinical evidences suggest that liver fat accumulation plays a central role in developing insulin resistance. Liver fat accumulation causes oxidative stress and endoplasmic reticulum stress of hepatocytes, and eventually, it could lead to cell dysfunction and cell death from a phenomenon known as lipotoxicity.25,26 As liver is instrumental in insulin metabolism, hepatic oxidative stress and liver damage are likely to be important contributors to insulin resistance.27 Insulin resistance is a major contributor of DM development. Many researchers have reported NAFLD as an important risk factor of incident DM.7,28–30 However, there is limited evidence about whether the resolution of NAFLD could lower the risk of future DM development or if newly developed NAFLD could increase the risk of future DM development. Herein, we evaluated the risk of future DM development according to changes in NAFLD status over time. Consequently, we revealed that the resolved NAFLD group has significantly lower future DM risk than the persistent NAFLD group, whereas the incident NAFLD group during follow-up has higher risk of future DM development than the no NAFLD group.

Sung et al.13 and Yamazaki et al.14 reported that the resolution of NAFLD identified by US was associated with a lower risk of incident DM. Those researches were designed as cross-sectional cohort studies using odds ratio. They collected the data of DM and NAFLD status at the point of analysis, therefore it is difficult to identify whether the change in NAFLD status preceded DM or vice versa. Although odds ratio could suggest association between the events, it has limitation to explain causal relationship over time. Therefore, it was difficult to ascertain the causality between NAFLD status change and future DM development from the previous studies. To analyze the causal relationship of NAFLD status change and DM development more clearly, HR of NAFLD status change was calculated by analyzing the serial follow-up data in this study. The strength of this study is that this is the first study that performed the survival analysis to confirm a more precise causal relationship between the dynamic change of NAFLD and time to DM occurrence.

Multivariate Cox regression model demonstrated that incident NAFLD and persistent NAFLD groups had 1.94-fold and 3.76-fold higher risk of future DM development, respectively, whereas the resolved NAFLD and no NAFLD groups did not significantly differ during follow-up in terms of the risk of future DM development. This result implies that in subjects with NAFLD, future DM risk can be reduced by reducing hepatic fat accumulation. Other identified risk factors in this study for DM development were higher fasting plasma glucose, older age, and increased ALT level. Higher fasting glucose level and increasing age are well-known risk factors of type 2 DM;31 however, unlike well known risk factors such as obesity, fasting plasma glucose, and increasing age, higher ALT level, which represents hepatic necro-inflammatory activity,32 has not been considered an important risk factor of type 2 DM. However, growing evidence indicates that elevated ALT is associated with higher future DM risk.33,34 In this study, the subjects with increased ALT level had 1.61-fold higher risk of future DM independently, and this is in agreement with previous studies which suggest that hepatic necro-inflammation plays a role in the pathogenesis of type 2 DM.33,34

We tried to reveal whether a change in NAFLD status influences the incident DM risk regardless of the baseline obesity status or BMI change over time. Interestingly, changes in the NAFLD status influenced future DM risk more significantly in the nonobese group than in the baseline-obese group. In the nonobese group, persistent NAFLD and incident NAFLD groups had 4.78-fold and 2.51-fold higher risk of DM development, respectively, while only persistent NAFLD showed 2.71-fold higher DM risk in the obese group. This result represents that change in NAFLD status was a more powerful predictor of future DM development in nonobese subjects than in obese subjects. This result is in agreement with previous studies reporting that hepatic fat accumulation in nonobese subjects was associated with insulin resistance independently of the presence of other component of metabolic syndrome.35 We also revealed that a change in the NAFLD status could be an independent predictor of future DM development regardless of BMI change. Yamazaki et al.14 demonstrated that NAFLD improvement showed protective effects for DM development only in subjects with BMI decrease and not in those with BMI increase. In the present study, the DM risk in the resolved NAFLD group was not significantly different from that of the no NAFLD group in subjects with increased or decreased BMI, whereas the persistent NAFLD and incident NAFLD groups had significantly higher DM development risks. This implies that NAFLD resolution could reduce future DM development risk regardless of BMI change. This result suggests that reduction of hepatic fat accumulation could be a key for the management of and preventing future DM development in NAFLD patients regardless of weight reduction.

This study has several limitations. First, documentation of NAFLD status depended on retrospective chart review of US results without histological evaluation. It would be the main limitation of our study, because US is subjective and it is hard to detect mild fatty liver. To compensate for this limitation, FLI was applied for validation and we could confirm the results using US were reproduced by FLI. Considering that biopsy is not an easily accessible test due to the risk of possible complications, the result of the present study, which was acquired using easily accessible noninvasive tests such as US and FLI, may be more useful in clinical practice. Second, this study was designed as a retrospective cohort study, and detailed information about family history, physical activity and homeostatic model assessment for insulin resistance were not available although they have been known as important risk factor for DM development.

In conclusion, this study is the first longitudinal study to demonstrate that future DM risk could be modified by changes in the NAFLD status over time. The resolution of NAFLD status could reduce the risk of future DM development, while development of new NAFLD could increase the risk of DM development. NAFLD diagnosed by US could be used as a useful clinical indicator for predicting and managing the risk of future DM development.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (No. NRF-2017R1C1B5016814) and the Bio & Medical Technology Development Program of the NRF funded by the Korean government (MSIT) (No. NRF-2018M3A9E8023861).

Footnotes

See editorial on page 383.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Study concept: S.S.K. Analysis of data and drafting of the manuscript: H.J.C. Data acquisition: S.H., J.I.P., M.J.Y., J.H.K. Study supervision: J.C.H., B.M.Y., K.M.L., S.J.S., K.J.L. Study planning: J.Y.C. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: S.W.C. All authors have approved the final revision.

REFERENCES

- 1.Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Afendy M, et al. Changes in the prevalence of the most common causes of chronic liver diseases in the United States from 1988 to 2008. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:524–530. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2011.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Younossi ZM, Blissett D, Blissett R, et al. The economic and clinical burden of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in the United States and Europe. Hepatology. 2016;64:1577–1586. doi: 10.1002/hep.28785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lonardo A, Ballestri S, Marchesini G, Angulo P, Loria P. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a precursor of the metabolic syndrome. Dig Liver Dis. 2015;47:181–190. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2014.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang KC, Hung HF, Lu CW, Chang HH, Lee LT, Huang KC. Association of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease with metabolic syndrome independently of central obesity and insulin resistance. Sci Rep. 2016;6:27034. doi: 10.1038/srep27034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kannel WB, McGee DL. Diabetes and cardiovascular risk factors: the Framingham study. Circulation. 1979;59:8–13. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.59.1.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jemal A, Ward E, Hao Y, Thun M. Trends in the leading causes of death in the United States, 1970–2002. JAMA. 2005;294:1255–1259. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.10.1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anstee QM, Targher G, Day CP. Progression of NAFLD to diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease or cirrhosis. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;10:330–344. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2013.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Park SK, Seo MH, Shin HC, Ryoo JH. Clinical availability of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease as an early predictor of type 2 diabetes mellitus in Korean men: 5-year prospective cohort study. Hepatology. 2013;57:1378–1383. doi: 10.1002/hep.26183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim SS, Cho HJ, Kim HJ, et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease as a sentinel marker for the development of diabetes mellitus in non-obese subjects. Dig Liver Dis. 2018;50:370–377. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2017.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mantovani A, Byrne CD, Bonora E, Targher G. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and risk of incident type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2018;41:372–382. doi: 10.2337/dc17-1902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chang Y, Jung HS, Yun KE, Cho J, Cho YK, Ryu S. Cohort study of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, NAFLD fibrosis score, and the risk of incident diabetes in a Korean population. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:1861–1868. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Choi JH, Rhee EJ, Bae JC, et al. Increased risk of type 2 diabetes in subjects with both elevated liver enzymes and ultrasonographically diagnosed nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a 4-year longitudinal study. Arch Med Res. 2013;44:115–120. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2013.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sung KC, Wild SH, Byrne CD. Resolution of fatty liver and risk of incident diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98:3637–3643. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yamazaki H, Tsuboya T, Tsuji K, Dohke M, Maguchi H. Independent association between improvement of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and reduced incidence of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2015;38:1673–1679. doi: 10.2337/dc15-0140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Angulo P. GI epidemiology: nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25:883–889. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03246.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tarantino G, Saldalamacchia G, Conca P, Arena A. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: further expression of the metabolic syndrome. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22:293–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2007.04824.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mancini M, Prinster A, Annuzzi G, et al. Sonographic hepatic-renal ratio as indicator of hepatic steatosis: comparison with (1) H magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Metabolism. 2009;58:1724–1730. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2009.05.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Strauss S, Gavish E, Gottlieb P, Katsnelson L. Interobserver and intraobserver variability in the sonographic assessment of fatty liver. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;189:W320–W323. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.2123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.American Diabetes Association. 2. Classification and diagnosis of diabetes: standards of medical care in diabetes-2018. Diabetes Care. 2018;41(Suppl 1):S13–S27. doi: 10.2337/dc18-S002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bedogni G, Bellentani S, Miglioli L, et al. The fatty liver index: a simple and accurate predictor of hepatic steatosis in the general population. BMC Gastroenterol. 2006;6:33. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-6-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang BL, Wu WC, Fang KC, et al. External validation of fatty liver index for identifying ultrasonographic fatty liver in a large-scale cross-sectional study in Taiwan. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0120443. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0120443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang X, Xu M, Chen Y, et al. Validation of the fatty liver index for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in middle-aged and elderly Chinese. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015;94:e1682. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000001682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rowland ML. Self-reported weight and height. Am J Clin Nutr. 1990;52:1125–1133. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/52.6.1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim JA, Choi CJ, Yum KS. Cut-off values of visceral fat area and waist circumference: diagnostic criteria for abdominal obesity in a Korean population. J Korean Med Sci. 2006;21:1048–1053. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2006.21.6.1048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu Q, Bengmark S, Qu S. The role of hepatic fat accumulation in pathogenesis of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) Lipids Health Dis. 2010;9:42. doi: 10.1186/1476-511X-9-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Neuschwander-Tetri BA. Hepatic lipotoxicity and the pathogenesis of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: the central role of nontriglyceride fatty acid metabolites. Hepatology. 2010;52:774–788. doi: 10.1002/hep.23719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li YX, Han TT, Liu Y, et al. Insulin resistance caused by lipotoxicity is related to oxidative stress and endoplasmic reticulum stress in LPL gene knockout heterozygous mice. Atherosclerosis. 2015;239:276–282. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2015.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Adams LA, Waters OR, Knuiman MW, Elliott RR, Olynyk JK. NAFLD as a risk factor for the development of diabetes and the metabolic syndrome: an eleven-year follow-up study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:861–867. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shibata M, Kihara Y, Taguchi M, Tashiro M, Otsuki M. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is a risk factor for type 2 diabetes in middle-aged Japanese men. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:2940–2944. doi: 10.2337/dc07-0792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ballestri S, Zona S, Targher G, et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is associated with an almost twofold increased risk of incident type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome. Evidence from a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;31:936–944. doi: 10.1111/jgh.13264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Danaei G, Finucane MM, Lu Y, et al. National, regional, and global trends in fasting plasma glucose and diabetes prevalence since 1980: systematic analysis of health examination surveys and epidemiological studies with 370 country-years and 2 7 million participants. Lancet. 2011;378:31–40. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60679-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Prati D, Taioli E, Zanella A, et al. Updated definitions of healthy ranges for serum alanine aminotransferase levels. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:1–10. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-137-1-200207020-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vozarova B, Stefan N, Lindsay RS, et al. High alanine aminotransferase is associated with decreased hepatic insulin sensitivity and predicts the development of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2002;51:1889–1895. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.6.1889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sattar N, Scherbakova O, Ford I, et al. Elevated alanine aminotransferase predicts new-onset type 2 diabetes independently of classical risk factors, metabolic syndrome, and C-reactive protein in the west of Scotland coronary prevention study. Diabetes. 2004;53:2855–2860. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.11.2855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim D, Kim WR. Nonobese fatty liver disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:474–485. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2016.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]