Abstract

Mounting evidence suggests excessive glucocorticoid activity may contribute to Alzheimer's disease (AD) and age-associated memory impairment. 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type-1 (HSD1) regulates conversion of glucocorticoids from inactive to active forms. HSD1 knock-out mice have improved cognition, and the nonselective inhibitor carbenoxolone improved verbal memory in elderly men. Together, these data suggest that HSD1 inhibition may be a potential therapy for cognitive deficits, such as those associated with AD. To investigate this, we characterized two novel and selective HSD1 inhibitors, A-918446 and A-801195. Learning, memory consolidation, and recall were evaluated in mouse 24 h inhibitory avoidance. Inhibition of brain cortisol production and phosphorylation of cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB), a transcription factor involved in cognition, were also examined. Rats were tested in a short-term memory model, social recognition, and in a separate group cortical and hippocampal acetylcholine release was measured via in vivo microdialysis. Acute treatment with A-801195 (10–30 mg/kg) or A-918446 (3–30 mg/kg) inhibited cortisol production in the ex vivo assay by ∼35–90%. Acute treatment with A-918446 improved memory consolidation and recall in inhibitory avoidance and increased CREB phosphorylation in the cingulate cortex. Acute treatment with A-801195 significantly improved short-term memory in rat social recognition that was not likely due to alterations of the cholinergic system, as acetylcholine release was not increased in a separate set of rats. These studies suggest that selective HSD1 inhibitors work through a novel, noncholinergic mechanism to facilitate cognitive processing.

Introduction

Current therapies for Alzheimer's disease (AD) only provide modest improvements in cognitive efficacy (Winblad and Jelic, 2004; Frankfort et al., 2006). Novel approaches for improving cognition in impaired individuals are clearly needed. One approach may involve targeting glucocorticoid function. Abnormally high levels of glucocorticoids are correlated with memory impairment in some patients with AD (Pomara et al., 2003) and depression (Bremmer et al., 2007). Increased glucocorticoid activity is also associated with greater hippocampal atrophy and memory impairment in the elderly (Lupien et al., 1998) and more rapid AD disease progression (Csernansky et al., 2006). Systemic administration of glucocorticoids increases β-amyloid formation and tau accumulation in transgenic AD mice (Green et al., 2006) and reduces neurogenesis in rats (Ambrogini et al., 2002). Furthermore, high glucocorticoid concentrations enhance kainic-acid induced neurotoxicity and impair mitochondrial function (Du et al., 2009).

These findings suggest that regulating glucocorticoids may mitigate the cognitive deficits of AD and slow disease progression. One potential target for regulating glucocorticoid levels is 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type-1 (HSD1). HSD1 catalyzes the enzymatic conversion of inactive glucocorticoids (cortisone in humans, 11-dehydrocorticosterone in rodents) to their respective active forms (cortisol, corticosterone). HSD1 is present in a variety of tissue, including brain regions important for cognition, such as the cortex and hippocampus. Local activation of HSD1 is believed to amplify glucocorticoid-regulated transcriptional responses, leading to, or exacerbating, glucocorticoid-mediated disorders (Tomlinson et al., 2004).

In metabolic conditions characterized by excessive glucocorticoid activity, HSD1 inhibition results in normalization of function. In mice with genetic or diet-induced obesity, selective HSD1 inhibitors normalized glucose levels (Lloyd et al., 2009; Wan et al., 2009). Similar effects of HSD1 inhibition have also been noted in humans (Rosenstock et al., 2010). Recent studies have shown that HSD1 is not strictly limited to metabolic processes. Aged C57BL/6 mice show watermaze deficits that correlate with increased HSD1 expression in the hippocampus and forebrain; overexpression of HSD1 similarly impaired performance (Holmes et al., 2010). Conversely, aged HSD1 knock-out mice have improved cognition and increased long-term potentiation relative to age-matched controls, suggesting a neuroprotective effect of HSD1 inhibition (Yau et al., 2001, 2007). The nonselective 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase inhibitor carbenoxolone improved verbal memory in elderly men and type II diabetics (Sandeep et al., 2004). In addition, metyrapone, which blocks glucocorticoid synthesis by inhibiting 11 β-hydroxylase, reversed a spatial memory deficit in tg2576 mice expressing human APP (Pedersen et al., 2006).Together, these findings suggest that HSD1 inhibition may be a potential new therapy for enhancing cognition.

In the present studies, we characterized two selective and potent HSD1 inhibitors, A-918446 in mice and A-801195 in rats. Inhibition of cortisol formation in brain tissue was examined using ex vivo preparations. Acute cognitive effects were investigated in the mouse inhibitory avoidance test of memory consolidation and recall and the rat short-term memory paradigm of social recognition. Alterations in phosphorylated cAMP response element-binding protein (pCREB), a transcription factor associated with learning and memory, were measured in mice. Last, acetylcholine efflux was examined with in vivo microdialysis in rats.

Materials and Methods

In vitro enzymatic assays and radioligand binding

The ability of test compounds to inhibit HSD1 enzymatic activity in vitro was evaluated in a scintillation proximity assay (SPA). As a source of enzyme Escherichia coli lysates expressing either truncated (lacking the first 24 aa) human, mouse, or rat HSD1 was used. For HSD2, the enzyme source was lysates from insect cells that had the full-length human, mouse, or rat 11β-HSD2 cDNA overexpressed using the baculovirus expression system. Tritiated-cortisone substrate, NADPH cofactor, and titrated compound were incubated with 11β-HSD1 enzyme at room temperature to allow the conversion to cortisol to occur. The reaction was stopped by adding a nonspecific HSD inhibitor, glycyrrhetinic acid. The tritiated cortisol was captured by a mixture of an anti-cortisol monoclonal antibody and SPA beads coated with anti-mouse antibodies. The reaction plate was shaken at room temperature and the radiolabel bound to SPA beads was then measured on a scintillation counter. Percentage inhibition was calculated based on the background (wells containing substrate without enzyme and test compound) and the maximal signal (wells containing substrate and enzyme without test compound). Percentage inhibition of each compound was calculated relative to the maximal signal, and IC50 curves were generated. Assuming competitive inhibition, the Cheng–Prusoff equation was used to calculate apparent dissociation constant (Ki) values from the IC50 values. This assay was applied to HSD2 as well, whereby tritiated cortisol and NAD+ were used as substrate and cofactor, respectively.

Binding studies were performed by CEREP under contract with Abbott Laboratories, except for glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid binding that were determined at Abbott. Binding was determined using a 10 μm concentration of A-918446 or A-801195. The binding affinities for 75 receptors, transporters, and ion channels were evaluated using radioligand binding (see supplemental Material, available at www.jneurosci.org). When available, the experiments were performed using recombinant human receptors cloned into various cell types. Glucocorticoid binding was evaluated using a Polar Screen glucocorticoid receptor competitor assay kit from Invitrogen with dexamethasone as a reference compound. Mineralocorticoid binding was determined using a PathHunter Chinese hamster ovary (CHO-K1) mineralocorticoid protein interaction nuclear hormone receptor cell line assay from DiscoveRx in both agonist and antagonist modes with aldosterone and spironolactone as reference agents, respectively.

Subjects

Male CD1/ICR mice (average 35 g; age 8–10 weeks) or Sprague Dawley rats (average 400 g; age 8–10 weeks) from Charles River were used for all experiments, except microdialysis studies, which used Sprague Dawley rats from Janvier. Food and water were available ad libitum, except during experiments. Animals were acclimated to the animal facilities for a period of 2 weeks before commencement of experimental procedures. Animals were tested in the light phase of a 12 h light/12 h dark schedule (lights on at 06:00 A.M.). All experiments were in compliance with Abbott's Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and the National Institutes of Health Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals guidelines in a facility accredited by the Association for the Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care.

Drug preparation and administration

A-918446, A-801195, and donepezil were synthesized at Abbott Laboratories. For most studies, A-918446 (1–100 mg/kg) was dosed in a solution of 5%Tween 80 (Sigma) and sterile water with extensive sonication in a warm bath. In the pretesting administration and no-shock 24 h inhibitory avoidance studies, A-918446 was dosed in a solution of 17% hydro-β-cyclodextrin (Sigma-Aldrich) and sterile water (to improve solubility), with extensive sonication in a warm bath. Mice received A-918446 via oral administration either 60 min before the training session, immediately after training, or 60 min before testing. A-801195 (1–30 mg/kg) was dosed in a solution of PEG400 with extensive sonication in a warm bath, and administered orally 1 h before tissue collection for the ex vivo inhibition study or 1 h before the social recognition training trial.

Blood plasma and brain concentrations

For the determination of plasma concentration and brain concentration, naive rats or mice were dosed with the compounds orally and humanely killed 1 h after dosing. Blood was collected into heparinized tubes and centrifuged, and the separated plasma was frozen at −20°C until analysis. For the determination of brain concentration of A-918446 and A-801195, brains were immediately removed, frozen at −20°C, and homogenized before analysis. Compounds were extracted from brain tissue via liquid–liquid extraction and quantified by liquid chromatography/mass spectroscopy.

HSD1 ex vivo enzymatic activity

The methods are similar to those described previously (Gao et al., 2009). Rats or mice received A-801195 (0, 3, 10, or 30 mg/kg) or A-918446 (0, 3, 10, or 30 mg/kg), respectively, 1 h before killing and removal of brain for ex vivo cortisol analysis by mass spectroscopy, as previously described (Gao et al., 2009). For rats, tissue from one hemisphere, minus the cerebellum, was extracted from each brain. For mice, the whole brain minus the cerebellum was collected. Tissue was transferred to 12-well plates containing an incubation buffer where the tissues were minced. Incubation buffer for mice was Dulbecco's PBS, and incubation buffer for rats was RPMI 1640 and 5% fetal bovine serum. A 1 mm solution of cortisone was added to each well based upon tissue weight, and the plate was incubated at 37°C for 3 h. Following incubation, media were centrifuged and supernatant from each well was transferred to a 96-well plate. The plate was stored overnight at −70°C, and the following day an equal volume of 100% acetonitrile was added to each well. The plate was centrifuged at 5°C for 30 min at 2500 rpm, and then 50 μl of the clear supernatant was added to wells on another plate containing 50 μl of a 200 nm concentration of flumethasone in 50% acetonitrile as the internal standard. Eight half-log spaced concentrations of cortisol were placed in pairs of additional cells as standards. Chromatography and mass spectroscopy was used to analyze wells for cortisol content, as previously described (Gao et al., 2009). Briefly, samples were first injected into a high-pressure liquid chromatography system (Shimadzu), with an Alltima C18 guard cartridge (Alltech Associates) used as an on-line solid phase extraction column and an YMC ODS-AQ column (Waters) used as the analytical column. The LC eluent was analyzed for cortisol content with an API 3000 triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (Applied Biosystems).

Cognitive testing

Mouse 24 h inhibitory avoidance.

Inhibitory avoidance training and testing took place in equipment purchased from Ugo Basile (Model 7550). Mice were removed from the colony room in their home cage, brought to the testing room, and allowed to habituate for at least 2 h. The effects of A-918446 on inhibitory avoidance were examined with three different dosing paradigms: 60 min before training, immediately after training, or 60 min before testing. Upon training initiation, mice were placed into the light side of a two-chambered compartment, during which time the retractable door separating the compartments was closed. After 30 s, the door was opened, and the latency to enter the dark chamber (all four paws and tail) was measured as an indication of general locomotor activity. After the subject crossed into the dark chamber, the door was closed and an inescapable footshock (0.2 mA, one second duration) was presented to the mouse. Twenty-one hours later all mice were once again moved to the testing room and allowed to habituate for a minimum of 2 h. Using the same methods as on the training day, mice were tested without being shocked. The latency to enter the dark chamber was again recorded and was the dependent variable measured for assessing memory retention (180 s is maximum latency).

Rat social recognition.

Social recognition methods are similar to those described previously (Fox et al., 2003). In this test of short-term memory, an adult rat interacts with an unfamiliar juvenile rat for 5 min. During this investigation period the adult exhibits behaviors such as close following, grooming, or sniffing the juvenile for as much as 60–80% of the 5 min trial. The juvenile rat is then removed and reintroduced after a delay period, and investigative behavior of the adult rat is again monitored. In normal adult rats, the duration of investigation is significantly reduced with delays of up to 30 min. Thus, the ratio of exploration during the second exposure relative to the first exposure (trial two:trial one) is significantly <1.0, indicating that the adult rat remembers the first exposure to the juvenile after this delay interval. However, this ratio increases with longer delays. Under the conditions used here, the ratio approaches 1.0 after a 120 min delay, indicating that the adult rat has forgotten the first exposure to the juvenile. A-801195 (1, 3, 10, and 30 mg/kg, p.o.) was administered 1 h before trial one. In an independent study the methods described above were repeated, with a novel juvenile introduced after the delay period (in trial two). If the effects of the compound are specific to cognition, the compound should not affect exploration of the unfamiliar juvenile (the ratio of trial two:trial one in this case should approach 1.0).

Neurochemistry

Phosphorylated cAMP response element binding protein.

Mice received A-918446 (0.3, 3, 30 mg/kg, p.o.) for examining dose-dependent changes in CREB phosphorylation. One hour after treatment with A-918446 or vehicle, all mice were anesthetized and perfused through the aorta with normal saline followed by 10% formalin for immunohistochemical assessment of CREB phosphorylation in the cingulate cortex. After perfusion, brains were removed, postfixed in 20% sucrose–PBS overnight, subsequently cut on a cryostat (40 μm coronal sections), and collected as free-floating sections in PBS. Sections were then immunostained using a three-step ABC peroxidase technique beginning with a 30 min incubation with blocking serum. Sections were next incubated with CREB antibody (rabbit monoclonal IgG, 1:1000; Cell Signaling Technology) for 48 h at 4°C, washed with PBS, and incubated for 1 h with either biotinylated secondary anti-mouse or anti-sheep Ab solution (1:200). Finally, sections were washed in PBS, incubated with ABC reagent (Vector Laboratories), and developed in a peroxidase substrate solution. Four to six serial sections from each animal were mounted, coverslipped, examined, and photographed with a light microscope (DMRB; Leica). A single section was then chosen on the basis of optimal immunoreactivity and anatomical similarity for immunoquantification, in which the experimenter was blind to treatment conditions. Immunoreactivity for pCREB in the cingulate cortex was quantified using an image analysis system (Leica Quantimet 500) that determined the number and/or area of peroxidase substrate-positive-stained neurons from digitized photomicrographs according to a pixel gray level empirically determined before analysis.

Microdialysis.

Male Sprague Dawley rats received stereotaxic surgery to implant microdialysis guide cannula (CMA/12) in the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) and the hippocampus. Rats were injected with sodium pentobarbital (50 mg/kg, i.p.) and implanted unilaterally with 14 mm guide cannula at stereotaxic coordinates 2.5 anterior to bregma, 0.6 lateral to the midline, and 3 ventral to the skull surface (mPFC) and 5.5 posterior to bregma, 4.5 lateral to the midline, and 7.5 ventral to the skull surface (hippocampus). The cannulae were secured in place with skull screws and dental acrylic. Rats were allowed to recover for 1 week after surgery. Microdialysis studies were conducted under resting conditions, with freely moving rats. Probes were perfused with Ringer solution containing 1 × 10−7 m neostigmine at a rate of 1.5 μl/min, and 30 μl of microdialysate fractions were collected every 20 min (6 before compound administration, and 9 afterward). A-801195 (30 mg/kg) or donepezil (1 mg/kg) were dosed intraperitoneally and samples were analyzed for acetylcholine by HPLC with electrochemical detection. Each 10 μl of microdialysate fraction was injected into a reversed phase column (Acetylcholine Kit; consisting of a precolumn 50 × 1.0 mm equipped with a an IMER for choline oxidase/catalase, and a microbore column, particle size 10 μm, 530 × 1.0 mm coupled to an immobilized enzyme reactor 50 × 1.0 mm, particle size 10 μm, containing acetylcholinesterase and choline oxidase; BAS) using a refrigerated autosampler (HTC PAL twin injector autosampler system, Axel Semrau). The mobile phase consisted of 50 mmol/L Na2HPO4, pH 8.5, and 5 ml/L ProClin (BAS). Flow rate was 0.12 ml/min (Rheos 2000 Flux pump, Axel Semrau), and the sample run time was <15 min. Acetylcholine was measured via an electrochemical detector (LC-4C, BAS) with a radial flow detector cell covered with a peroxidase redox polymer (electrode set at −0 mV, negative potential, switch position on back = RDN, full scale 2 nA) versus an Ag/AgCl reference electrode. The system was calibrated by standard solutions (acetylcholine) containing 0.1 pmol/10 μl injection. Acetylcholine was identified by its retention time and peak height with an external standard method using chromatography software (CP Spirit, Version 4.4.22, Justice Laboratory Software).

Statistics

Data were analyzed using Graph Pad Prism 4.0 (GraphPad Software). Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. Cortisol inhibition, pCREB, and social recognition dose–response data were analyzed using a one-way ANOVA with Dunnett's post hoc analyses, comparing the response of drug-treated groups to the response of vehicle controls. Social recognition familiar versus unfamiliar juvenile was analyzed using a two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni's post hoc analyses, comparing the vehicle familiar group to the vehicle unfamiliar and the vehicle familiar to the treated familiar group. Microdialysis data were analyzed using two-way ANOVA. For 24 h inhibitory avoidance dose–response studies, training day and test day latency data were separately analyzed with a Kruskal-Wallis nonparametric test with Dunn post hoc comparisons to compare treatment groups. For studies comparing time of administration, Mann–Whitney tests were used to compare vehicle and treatment groups at each time point. For presentation purposes, data are graphed as ± SEM.

Results

In vitro enzymatic assays and radioligand binding

The potency for human, rat, and mouse HSD1 and HSD2 inhibition are presented in Table 1. Both A-918446 and A-801195 are selective for HSD1 versus HSD2, but there is variability in potency across species. A-918446 is 10 times more potent in mice (Ki = 2.7 nm) than rats (Ki = 27.2 nm). A-801195 is over 15 times more potent in rats (Ki = 1.9 nm) compared with mice (Ki = 32.6 nm). Thus, A-918446 was used in subsequent mouse experiments while A-801195 was used in subsequent rat experiments.

Table 1.

HSD in vitro enzyme inhibition potency

| Enzyme source | A-918446 | A-801195 |

|---|---|---|

| Human HSD1 | 3.8 (n = 20) | 9.9 (n = 3) |

| Human HSD2 | 2960 (n = 6) | >10,000 (n = 2) |

| Mouse HSD1 | 2.7 (n = 11) | 32.6 (n = 7) |

| Mouse HSD2 | >10,000 (n = 3) | >10,000 (n = 3) |

| Rat HSD1 | 27.2 (n = 10) | 1.9 (n = 6) |

| Rat HSD2 | 2710 (n = 4) | >10,000 (n = 3) |

Ki values presented in nm.

Each HSD1 inhibitor was also evaluated for binding in a panel of 75 receptors, transporters, and ion channels. At a concentration of 10 μm, A-918446 did not yield >30% displacement of any reference compound. Similarly, a 10 μm concentration of A-801195 did not yield >47% displacement of any reference compound. (See supplemental Material, available at www.jneurosci.org, for a complete list of the receptors, transporters, and ion channels tested). In the glucocorticoid and mineralocortioid assays, no activity of A-918446 or A-801195 at concentrations up to 10 μm was observed (data not shown).

Blood plasma and brain concentrations

Administration of A-918446 (30 mg/kg, p.o.) in mice produced levels in brain (15.3 μg/g at 1 h) that were approximately double the plasma concentration (7.8 μg/ml at 1 h). In rat, A-801195 (30 mg/kg, p.o.) was observed in brain (6.2 μg/g at 1 h) at a level that was slightly higher than plasma concentration (5.3 μg/ml at 1 h).

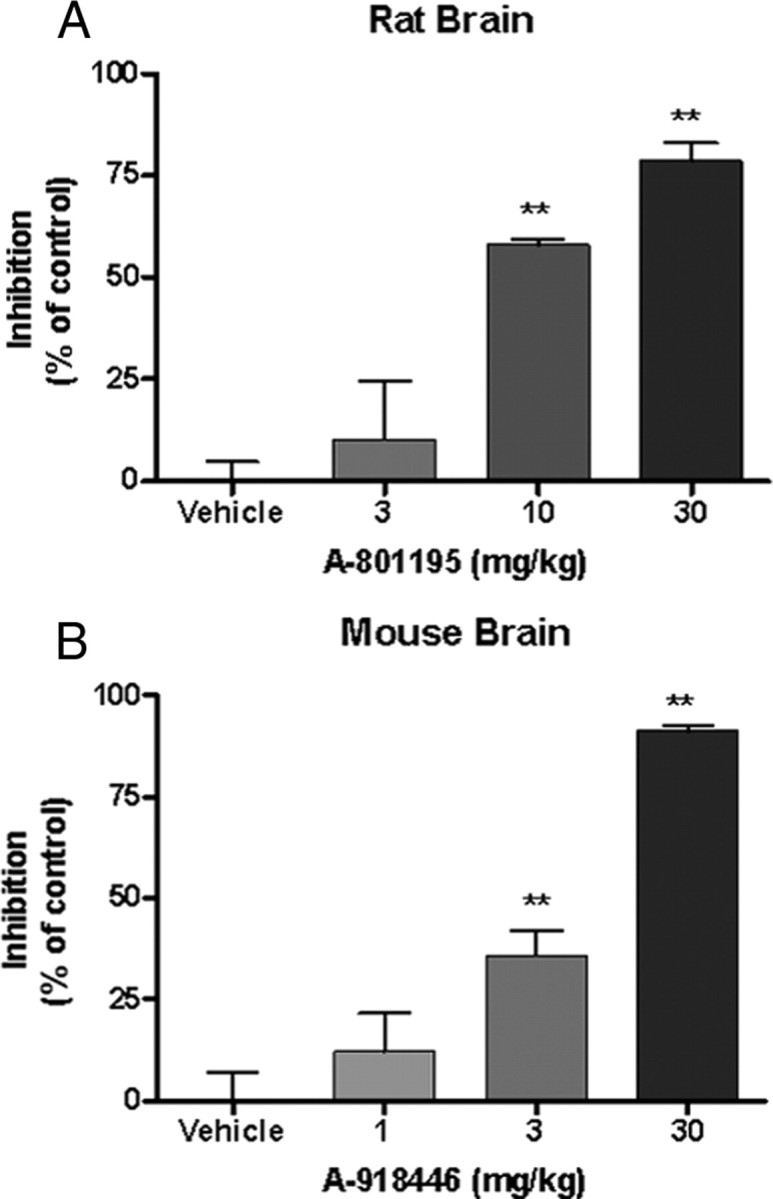

Ex vivo cortisol inhibition

A single administration of A-801195 significantly inhibited production of brain cortisol in rats, F(3,16) = 22.48, p < 0.001 (Fig. 1A). The 10 mg/kg dose resulted in a 58.0 ± 1.58% inhibition of cortisol production compared with control (p < 0.05), while the 30 mg/kg dose resulted in 78.6 ± 4.35% inhibition (p < 0.01). The 3 mg/kg dose inhibited cortisol production by 10.4 ± 14.58%, which was not significantly different from vehicle (p > 0.05). Similarly, administration of A-918446 significantly reduced brain cortisol levels in mice, F(3,42) = 23.40, p < 0.001 (Fig. 1B). A dose of 3 mg/kg inhibited cortisol production by 36.0 ± 6.22% compared with vehicle (p < 0.01), and a dose of 30 mg/kg produced 91.5 ± 1.24% inhibition (p < 0.01). The 1 mg/kg dose inhibited cortisol formation by 12.3 ± 9.40%, which was not significantly different from vehicle (p > 0.05).

Figure 1.

Effect of HSD1 inhibition on ex vivo cortisol production relative controls (presented as ± SEM). Rats or mice were injected with vehicle or HSD1 inhibitor 1 h before tissue collection. Whole brain was minced and incubated in cortisone for 3 h. A, A-801195 at doses of 10 and 30 mg/kg significantly reduced cortisol production relative to vehicle. B, A-918446 at doses of 3 and 30 mg/kg significantly reduced the formation of cortisol in rats. **p < 0.01.

Twenty-four hour inhibitory avoidance

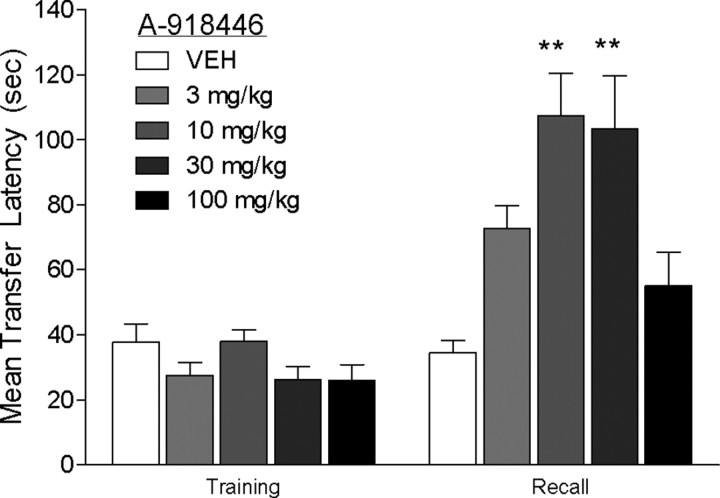

Pretraining dose–response

Acute treatment with A-918446 1 h before training did not significantly alter latency to cross during the training trial. When mice were tested for memory retention 24 h later, A-918446 significantly increased the latency to cross, H(5) = 19.99. Post hoc testing indicated significant improvement with the 10 and 30 mg/kg doses (p < 0.01), but not 3 or 100 mg/kg doses (p > 0.05) (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Inhibitory avoidance with pretraining dosing. Mice were dosed with A-918446 (3, 10, 30, or 100 mg/kg) or vehicle 1 h before inhibitory avoidance training and tested 24 h later. A-918446 significantly increased latencies during the test trial, suggesting improved learning and/or memory consolidation. Data are expressed as ± SEM (n = 8–9 per group). **p < 0.01.

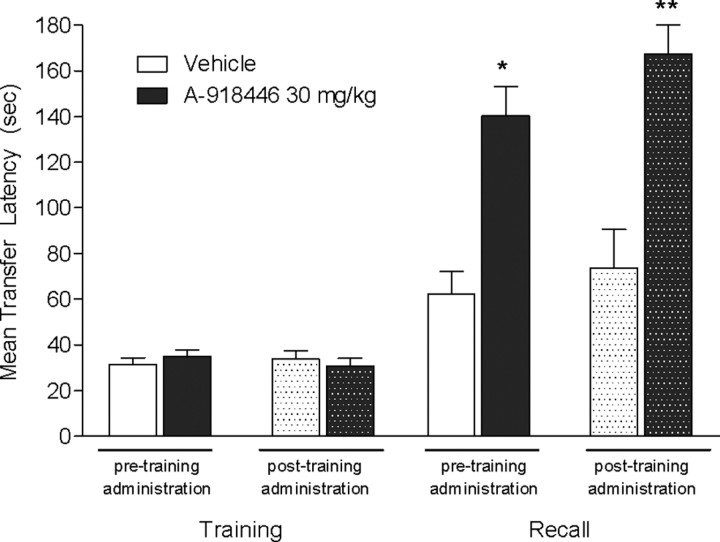

Pretraining and posttraining comparison

A-918446 was administered 1 h before training, as described in the previous experiment, or immediately after training. Significant increases in transfer latencies were observed 24 h later, H(4) = 20.92, with both pretraining (p < 0.05) and posttraining drug administration (p < 0.01), suggesting an effect on memory consolidation (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Inhibitory avoidance with pretraining or posttraining dosing. Mice were dosed with A-918446 (30 mg/kg) or vehicle 1 h before inhibitory avoidance training or immediately after training, and tested 24 h later. A-918446 significantly increased latencies during the test trial with both dosing regimens, suggesting improved memory consolidation. Data are expressed as ± SEM (n = 10 per group). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

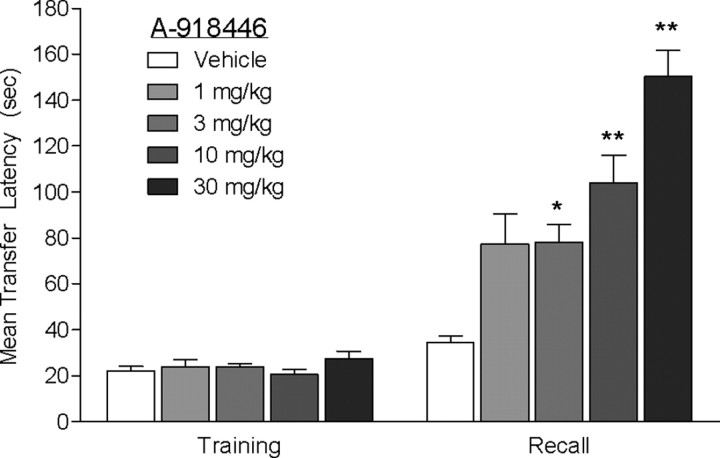

Pretesting dose–response

Mice were injected with vehicle or A-918446 1 h before testing, 23 h after inhibitory avoidance training. A Kruskal–Wallis test revealed a significant main effect of treatment on transfer latencies H(5) = 33.13 (p < 0.01) on test day. Post hoc tests revealed that A-918446 significantly increased transfer latencies at the doses of 3 mg/kg (p < 0.05), 10 mg/kg (p < 0.05), and 30 mg/kg (p < 0.01) compared with vehicle, indicating improved memory recall in this task (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Inhibitory avoidance with pretest dosing. Mice were dosed with A-918446 (1, 3, 10, or 30 mg/kg) or vehicle 1 h before inhibitory avoidance testing (mice received no treatment on the previous day). A-918446 significantly increased latencies during the test trial, suggesting improved memory recall. Data are expressed as ± SEM (n = 12 per group). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

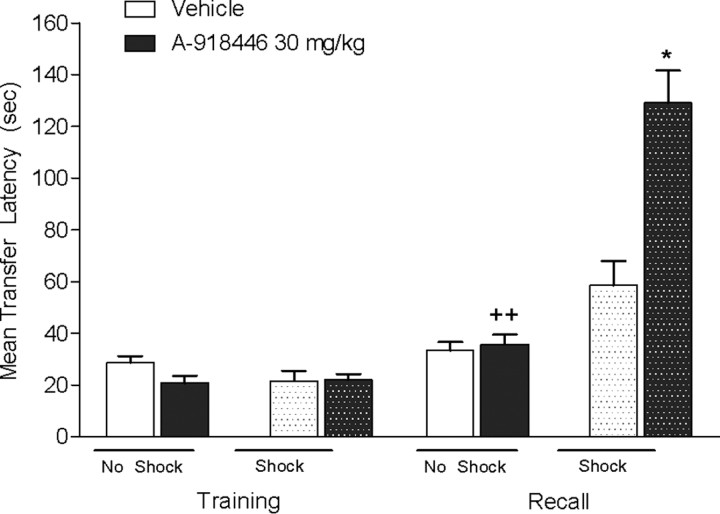

No shock control

Mice were injected with vehicle or A-918446 1 h before training and either received a 0.2 mA shock or no shock. Kruskal-Wallis revealed a significant effect on transfer latencies, H(4) = 31.26 (p < 0.01) on test day. Post hoc testing revealed that A-918446 significantly increased transfer latencies versus control in the shocked group (p < 0.05), but not the group that did not receive shock (p > 0.05). Furthermore, there was a significant difference between the A-918446 mice that received a shock compared with those that did not receive a shock (p < 0.01), indicating that increase transfer latencies are not a result of nonspecific effects of treatment (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Inhibitory avoidance with or without footshock. Mice were dosed with A-918446 (30 mg/kg) or vehicle 1 h before inhibitory avoidance training and received a 0.2 mA shock or no shock. A-918446 significantly increased latencies during the test trial when the mice were shocked and had no effect without a shock, suggesting increased latencies are not a result of nonspecific effects. Data are expressed as ± SEM (n = 15 per group). *p < 0.05 versus vehicle shock group, ++p < 0.01 versus A-918446 shock group.

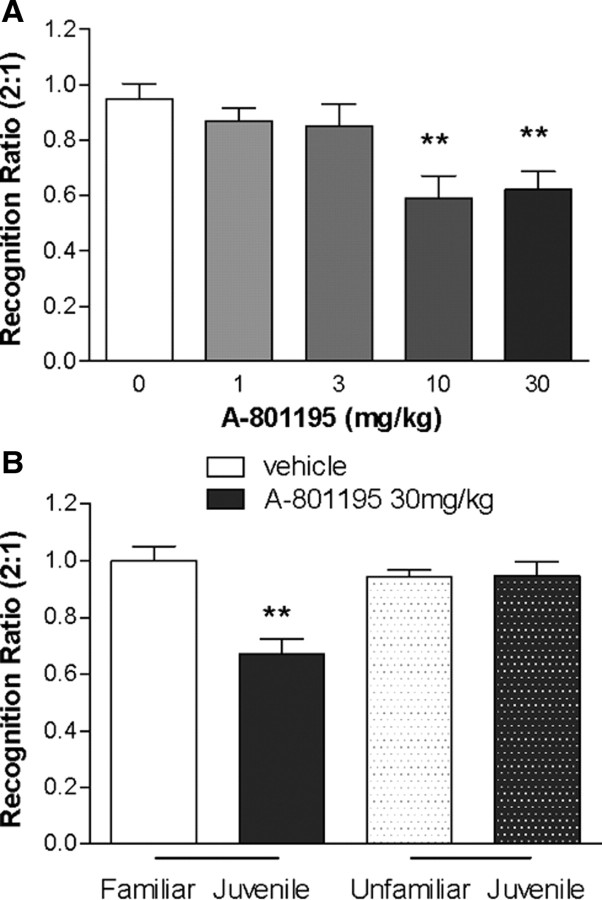

Social recognition

As shown in Figure 6A, adult rats treated with A-801195 significantly reduced the investigation time of a familiar juvenile (expressed as a decreased T2:T1 ratio), indicating significant increases in memory recall, F(4,43) = 5.683, p < 0.01. Significant treatment effects were observed at 10 and 30 mg/kg (p < 0.01), but not at 1 or 3 mg/kg (p > 0.05). To test whether the decreased T2:T1 ratio was a result of a nonspecific decrease in exploration time, rats were treated with vehicle or A-801195 (30 mg/kg) and after a normal training session were tested with either a familiar or unfamiliar juvenile rat (Fig. 6B). Significant effects of treatment, F(1,29) = 12.43, p < 0.05; juvenile familiarity, F(1,29) = 5.791, p < 0.05; and the interaction, F(1,29) = 13.08, p < 0.05, were observed. Post hoc testing showed no significant difference between vehicle-treated rats and those treated with A-801195 during exploration of a novel juvenile rat (p > 0.05), indicating the effects of A-801195 in this model are not due to general changes in investigational behavior. Consistent with the initial experiment, A-801195 (30 mg/kg) significantly decreased investigation time (p < 0.05).

Figure 6.

Social recognition with novel or familiar juvenile rats. A, Rats were injected orally with vehicle, or A-801195 1 h before being exposed to a juvenile rat (trial one). Two hours later, the rat was reexposed to the same juvenile (trial two) and the ratio of the investigation times of the two trials was determined and recorded. Data are expressed as ± SEM (n = 8–9 per group). B, Rats were dosed with vehicle or 30 mg/kg of A-801195 1 h before being exposed to a juvenile rat (trial one). Two hours later, the rat was reexposed to the same juvenile (a familiar juvenile) or exposed to a new juvenile (a novel juvenile; trial two) and the ratio of the investigation times of the two trials is recorded. **p < 0.001.

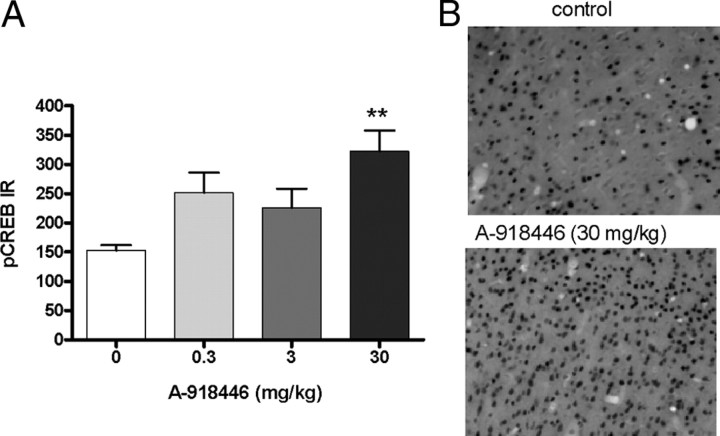

CREB phosphorylation

A significant increase of CREB phosphorylation was observed in the mouse cingulate cortex 60 min after administration of A-918446, F(3,23) = 5.57, p < 0.01 (Fig. 7A). Post hoc testing indicated that the 30 mg/kg dose, but not the 3 or 10 mg/kg doses, significantly increased pCREB staining. Representative sections are shown in Figure 7B.

Figure 7.

A, pCREB phosphorylation in cingulate cortex. Mice were injected with HSD1 inhibitor (0.3, 3, or 30 mg/kg; p.o.) or vehicle 1 h before tissue collection. A-918446 at a dose of 30 mg/kg significantly increased the phosphorylation of CREB. Data are expressed as ± SEM (n = 6 per group). **p < 0.01. B, Photomicrographs of representative sections from mice receiving vehicle or A-918446 (30 mg/kg).

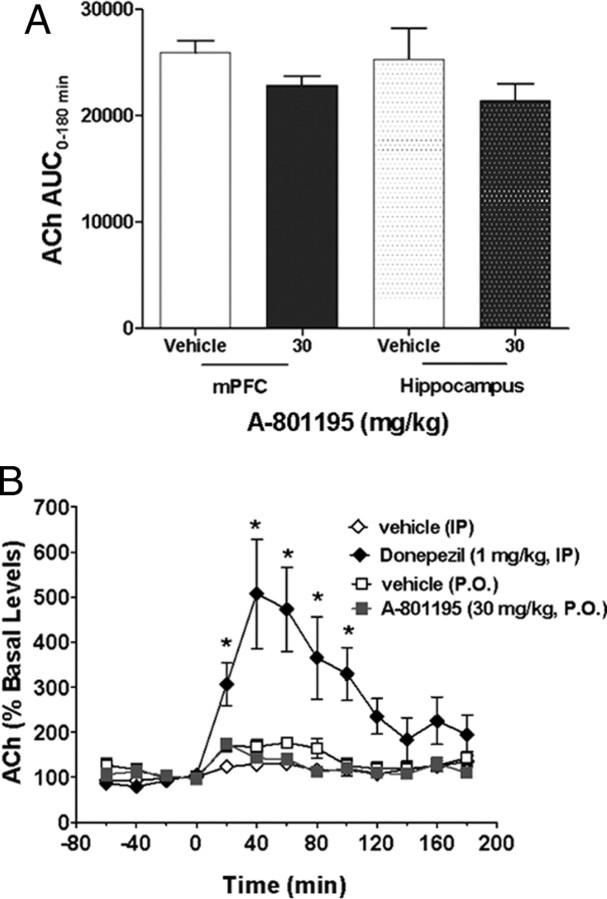

In vivo microdialysis

Acute, single administration of A-801195 (30 mg/kg, p.o.) did not significantly alter acetylcholine release in the medial prefrontal cortex or in the hippocampus over the course of the 3 h collection period (p >0.05) (Fig. 8A). In contrast, the acetylcholinesterase inhibitor donepezil robustly increased acetylcholine release in the mPFC, F(1,11) = 43.0, p < 0.001, as shown in Figure 8B. In addition, a significant effect of time, F(12,132) = 12.0, p < 0.001, and a treatment by time interaction, F(12,132) = 8.96, p < 0.001, were observed.

Figure 8.

A, Effect of A-801195 (30 mg/kg, p.o.) on cortical and hippocampal acetylcholine release in rats over the course of a 3 h collection period. No significant differences were observed in either structure. Data are presented as area under the curve (AUC) in arbitrary units as ± SEM (n = 4 vehicle group, n = 10 A-801195 group). B, Time course of acetylcholine release in the prefrontal cortex. Donepezil significantly increased acetylcholine release while no effect of A-801195 was observed. Data are ± SEM of the percentage change from baseline based on two 20 min samples before drug application [n = 8 for vehicle (i.p.), n = 5 for donepezil, n = 4 for vehicle (p.o.), n = 10 for A-801195]. *p < 0.05 versus vehicle group.

Discussion

These studies demonstrate that the potent and selective HSD1 inhibitors A-918446 and A-801195 significantly affect multiple aspects of brain function. Similar to other HSD1 inhibitors (Yeh et al., 2006), A-918446 and A-801195 robustly decrease cortisol formation in brain ex vivo tissue preparations. Although cognitive enhancement with HSD inhibitors in rodents has been shown after several days of treatment in older subjects (Sooy et al., 2010), these studies are the first to show that acute treatment with HSD1 inhibitors can improve cognitive performance. While young animals do not represent a model of AD, it is of interest to observe the glucocorticoid modulation can impact performance in otherwise healthy subjects. When cholinergic activity was investigated with in vivo microdialysis, no changes in resting acetylcholine release in the prefrontal cortex or hippocampus were observed. One possible mechanism for enhanced cognition may be glucocorticoid effects on cell signaling. Increased pCREB phosphorylation was observed after acute dosing with A-918446 in a time frame consistent with improved memory recall in inhibitory avoidance.

One of the primary modes by which glucocorticoids alter cellular signaling is through translocation of the ligand bound receptor to the nucleus, followed by transcriptional alterations and ultimately changes in the formation of proteins and enzymes. Evidence suggests that the actions of HSD1 inhibitors on metabolic functions are mediated through this cascade of events (Tomlinson et al., 2004). However, there is increasing evidence from the literature that glucocorticoid-mediated alterations of cognitive processing may be mediated in part via fast, nongenomic pathways (Makara and Holler, 2001; Joëls, 2008). In the mouse 24 h inhibitory avoidance task, pretesting treatment with A-918446 significantly improved memory recall, indicating that HSD1 inhibition can exert its effects within1 h. Similarly, significantly improved performance in the rat social recognition test was observed within 3 h of administration of A-801195. Significant decreases in cortisol production were observed in the brains of satellite animals at 1 h with the same doses. While HSD1 inhibitors may substantially inhibit activity by 78% in ex vivo preparations for over 16 h (our unpublished observations), the current experiments suggest that acute cognitive efficacy may be mediated through a nongenomic pathway. Based on these data, local inhibition of active glucocorticoid formation may lead to beneficial effects on cognition, although the level of inhibition required may differ between compounds, species, and cognitive measures. As HSD1 inhibitors lower intracellular glucocorticoids, it may also be hypothesized that active glucocortioids coming from the circulation could balance overall activity. This is unlikely in the present scenario as chronic treatment with compound A-918446 either has no effect or decreases plasma corticosterone levels in mice (our unpublished observations). Future studies measuring intracerebral corticosterone with in vivo microdialysis could potentially clarify the nature of these rapid effects of HSD1 inhibitors.

It is interesting to note that pretraining doses of A-918446 increased transfer latency in the mouse inhibitory avoidance assay in a dose-dependent manner across the doses of 3–30 mg/kg, but not 100 mg/kg. There are two potential explanations for the lack of acute cognitive effects with the highest dose. The first is that some glucocorticoid activity is necessary for memory formation, and this high dose completely abolished all production. A second possibility may be attributed to nonspecific effects at higher concentrations. In vitro testing of A-918446 found off-target effects at a concentration of 10 μm with 30% or less receptor activity at σ, κ, serotonin 5-HT2C, and Neurokinin 1 receptors. The 100 mg/kg dose used in inhibitory avoidance achieved an estimated plasma concentration of approximately sixfold higher than the radioligand study, so it is possible that activity at these other receptors affected performance. It should also be noted that improvement in inhibitory avoidance performance is not strictly the result of HSD1 inhibition altering glucocorticoid activity at the time of the shock. Although treatment with the HSD1 inhibitor 1 h before training leads to lower glucocorticoid activity at the time of the shock, dosing ∼1 min after mice received the shock allows glucocorticoid levels to naturally rise in response to the shock and decline during the onset of the action of the drug. In both of these cases, an HSD1 inhibitor was not on board during the retention test, suggesting memory consolidation effects. Conversely, when the drug was administered only before the retention test, glucocorticoid levels would have been normal throughout training and the memory consolidation process and only decreased during the test trial, suggesting effects on memory recall. Combined with the finding that A-801195 significantly improved short-term memory in the rat social recognition paradigm, these data suggest that HSD1 inhibitors are not specifically interacting with aversive stimuli to improve cognition.

One of the mechanisms by which glucocorticoids may be altering cognitive processing through nongenomic pathways is through modulating neurotransmitters such as acetylcholine, dopamine, GABA, or glutamate. Interestingly, in contrast to currently available AD treatments, such as acetylcholinesterase inhibitors, the HSD1 inhibitor A-801195 (30 mg/kg) did not increase acetylcholine release in the prefrontal cortex or hippocampus. The current data suggest that HSD1 inhibitors may lead to symptomatic alleviation through a mechanism that is not dependent upon an increase in cholinergic tone. In addition to a lack of effect on extracellular ACh in the hippocampus or frontal cortex, A-801195 also did not alter dopamine levels in either of these brain regions (data not shown). Based on selectivity data, it does not appear likely that the HSD1 inhibitors used in the present experiments are affecting procognitive changes through off-target effects. The 10 mg/kg doses of A-918446 of A-801195 achieve full efficacy in inhibitory and social recognition, respectively. The plasma levels associated with those doses for each compound are approximately half of the concentrations used in the radioligand binding studies and well below the threshold for off-target effects. Another possible explanation may be GABA activity modulated by neurosteroids. For example, metyrapone, which significantly reduces serum glucocorticoid levels, leads to increases in DOC (deoxycorticosterone) and THDOC (tetrahydrodeoxycorticosterone) (Rupprecht et al., 1998), of which the latter is a positive allosteric modulator activity of the GABAA receptor that can induce memory impairments (Schwabe et al., 2007). A-918446 and A-801195 are most likely not acting through this mechanism since HSD1 inhibitors downregulate the conversion of inactive glucocorticoids (cortisone or 11-dehydrocorticosterone) back to active forms in specific tissue (Tomlinson et al., 2004), and rats and mice receiving these compounds show cognitive enhancements. In contrast, metabolites of cortisone, such as allotetrahydrocortisone and tetrahydrocortisone, are antagonists of GABAA activity (Strömberg et al., 2005). As the GABAA antagonist bicuculline exerts memory-enhancing effects (Luft et al., 2004), it is possible that metabolites of cortisone may have procognitive effects via this pathway. Last, given reports of glucocorticoid- or dexamethasone-mediated fast nongenomic changes in extracellular levels of glutamate (Semba et al., 1995; Venero and Borrell, 1999), it would be of interest to assess the effects of HSD1 inhibitors on glutamate release.

HSD1 inhibitors may also be influencing cognition through signaling transduction pathways. The activation/phosphorylation of CREB is regarded as a key biochemical event in the formation of long-term memory (Han et al., 2009). Pharmacological or molecular inhibition of pCREB activity may lead to memory impairment, while overexpression and activation may contribute to enhanced memory (Josselyn et al., 2001, 2004; Mamiya et al., 2009). A-918446 significantly increased pCREB expression in the anterior cingulate 1 h after dosing, a time frame that parallels the cognitive improvement observed in inhibitory avoidance with pretesting injections. Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that chronic glucocorticoid receptor activation inhibits CREB transcriptional activity that may contribute to the cognitive impairment associated with high circulating glucocorticoid levels (Föcking et al., 2003). This is consistent with the possibility that the cognitive enhancing mechanism of HSD1 inhibition may be mediated through reduced glucocorticoid receptor activity and subsequent increased CREB activation/phosphorylation.

Overall, these data suggest that HSD1 inhibitors provide a novel approach to improve cognition. As stress and/or excessive glucocorticoid activity are linked with the exacerbation of AD symptoms (Wilson et al., 2005; Csernansky et al., 2006), loss of hippocampal mass (Lupien et al., 1998), and reduced neurogenesis in rodents (Tanapat et al., 2001; Ambrogini et al., 2002), inhibition of HSD1 may also slow disease progress. Additional studies in models of AD, such as APP-overexpressing mice, may offer further evidence of the potential for HSD1 inhibitors to act as both symptomatic and disease-modifying agents.

Footnotes

This work was funded by Abbott Laboratories. All authors are current or past employees of Abbott Laboratories. We thank Steven Fung and Stanley Franklin for assistance with the ex vivo cortisol assays and Salam Shaaban and Tegest Kebede for providing the data from the glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid receptor assays.

References

- Ambrogini P, Orsini L, Mancini C, Ferri P, Barbanti I, Cuppini R. Persistently high corticosterone levels but not normal circadian fluctuations of the hormone affect cell proliferation in the adult rat dentate gyrus. Neuroendocrinology. 2002;76:366–372. doi: 10.1159/000067581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bremmer MA, Deeg DJ, Beekman AT, Penninx BW, Lips P, Hoogendijk WJ. Major depression in late life is associated with both hypo- and hypercortisolemia. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62:479–486. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csernansky JG, Dong H, Fagan AM, Wang L, Xiong C, Holtzman DM, Morris JC. Plasma cortisol and progression of dementia in subjects with Alzheimer-type dementia. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:2164–2169. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.12.2164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du J, Wang Y, Hunter R, Wei Y, Blumenthal R, Falke C, Khairova R, Zhou R, Yuan P, Machado-Vieira R, McEwen BS, Manji HK. Dynamic regulation of mitochondrial function by glucocorticoids. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:3543–3548. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812671106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Föcking M, Hölker I, Trapp T. Chronic glucocorticoid receptor activation impairs CREB transcriptional activity in clonal neurons. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;304:720–723. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)00665-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox GB, Pan JB, Radek RJ, Lewis AM, Bitner RS, Esbenshade TA, Faghih R, Bennani YL, Williams M, Yao BB, Decker MW, Hancock AA. Two novel and selective nonimidazole H3 receptor antagonists A-304121 and A-317920: II. In vivo behavioral and neurophysiological characterization. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;305:897–908. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.047241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankfort SV, Appels BA, De Boer A, Tulner LR, Van Campen JP, Koks CH, Beijnen JH. Treatment effects of rivastigmine on cognition, performance of daily living activities and behaviour in Alzheimer's disease in an outpatient geriatric setting. Int J Clin Pract. 2006;60:646–654. doi: 10.1111/j.1368-5031.2006.00970.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao L, Chiou WJ, Camp HS, Burns DJ, Cheng X. Quantitative measurements of corticosteroids in ex vivo samples using on-line SPE-LC/MS/MS. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2009;877:303–310. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2008.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green KN, Billings LM, Roozendaal B, McGaugh JL, LaFerla FM. Glucocorticoids increase amyloid beta and tau pathology in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. J Neurosci. 2006;26:9047–56. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2797-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han JH, Kushner SA, Yiu AP, Hsiang HL, Buch T, Waisman A, Bontempi B, Neve RL, Frankland PW, Josselyn SA. Selective erasure of a fear memory. Science. 2009;323:1492–1496. doi: 10.1126/science.1164139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes MC, Carter RN, Noble J, Chitnis S, Dutia A, Paterson JM, Mullins JJ, Seckl JR, Yau JL. 11β-Hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 expression is increased in the aged mouse hippocampus and parietal cortex and causes memory impairments. J Neurosci. 2010;30:6916–6920. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0731-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joëls M. Functional actions of corticosteroids in the hippocampus. Eur J Pharmacol. 2008;583:312–321. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.11.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Josselyn SA, Shi C, Carlezon WA, Jr, Neve RL, Nestler EJ, Davis M. Long-term memory is facilitated by cAMP response element-binding protein overexpression in the amygdala. J Neurosci. 2001;21:2404–2412. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-07-02404.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Josselyn SA, Kida S, Silva AJ. Inducible repression of CREB function disrupts amygdala-dependent memory. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2004;82:159–163. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2004.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd DJ, Helmering J, Cordover D, Bowsman M, Chen M, Hale C, Fordstrom P, Zhou M, Wang M, Kaufman SA, Véniant MM. Antidiabetic effects of 11β-HSD1 inhibition in a mouse model of combined diabetes, dyslipidaemia and atherosclerosis. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2009;11:688–699. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2009.01034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luft T, Pereira GS, Cammarota M, Izquierdo I. Different time course for the memory facilitating effect of bicuculline in hippocampus, entorhinal cortex, and posterior parietal cortex of rats. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2004;82:52–56. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2004.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupien SJ, de Leon M, de Santi S, Convit A, Tarshish C, Nair NP, Thakur M, McEwen BS, Hauger RL, Meaney MJ. Cortisol levels during human aging predict hippocampal atrophy and memory deficits. Nat Neurosci. 1998;1:69–73. doi: 10.1038/271. [Erratum (1998) 1:329] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makara GB, Haller J. Non-genomic effects of glucocorticoids in the neural system. Evidence, mechanisms and implications. Prog Neurobiol. 2001;65:367–390. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(01)00012-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mamiya N, Fukushima H, Suzuki A, Matsuyama Z, Homma S, Frankland PW, Kida S. Brain region-specific gene expression activation required for reconsolidation and extinction of contextual fear memory. J Neurosci. 2009;29:402–413. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4639-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen WA, McMillan PJ, Kulstad JJ, Leverenz JB, Craft S, Haynatzki GR. Rosiglitazone attenuates learning and memory deficits in Tg2576 Alzheimer mice. Exp Neurol. 2006;199:265–273. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2006.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomara N, Greenberg WM, Branford MD, Doraiswamy PM. Therapeutic implications of HPA axis abnormalities in Alzheimer's disease: review and update. Psychopharmacol Bull. 2003;37:120–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenstock J, Banarer S, Fonseca VA, Inzucchi SE, Sun W, Yao W, Hollis G, Flores R, Levy R, Williams WV, Seckl JR, Huber R. The 11-β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 inhibitor INCB13739 improves hyperglycemia in patients with type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled by metformin monotherapy. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:1516–1522. doi: 10.2337/dc09-2315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rupprecht R, Ströhle A, Hermann B, di Michele F, Spalletta G, Pasini A, Holsboer F, Romeo E. Neuroactive steroid concentrations following metyrapone administration in depressed patients and healthy volunteers. Biol Psychiatry. 1998;44:912–914. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(97)00521-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandeep TC, Yau JL, MacLullich AM, Noble J, Deary IJ, Walker BR, Seckl JR. 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase inhibition improves cognitive function in healthy elderly men and type 2 diabetics. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:6734–6739. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0306996101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwabe K, McIntyre DC, Poulter MO. The neurosteroid THDOC differentially affects spatial behavior and anesthesia in slow and fast kindling rat strains. Behav Brain Res. 2007;178:283–292. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2007.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semba J, Miyoshi R, Kanazawa M, Kito S. Effect of systemic dexamethasone on extracellular amino acids, GABA and acetylcholine release in rat hippocampus using in vivo microdialysis. Funct Neurol. 1995;10:17–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sooy K, Webster SP, Noble J, Binnie M, Walker BR, Seckl JR, Yau JL. Partial deficiency or short-term inhibition of 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 improves cognitive function in aging mice. J Neurosci. 2010;30:13867–13872. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2783-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strömberg J, Bäckström T, Lundgren P. Rapid nongenomic effect of glucocorticoid metabolites and neurosteroids on the c-aminobutyric acid-A receptor. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;21:2083–2088. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04047.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanapat P, Hastings NB, Rydel TA, Galea LA, Gould E. Exposure to fox odor inhibits cell proliferation in the hippocampus of adult rats via an adrenal hormone-dependent mechanism. J Comp Neurol. 2001;437:496–504. doi: 10.1002/cne.1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomlinson JW, Walker EA, Bujalska IJ, Draper N, Lavery GG, Cooper MS, Hewison M, Stewart PM. 11β hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1: a tissue specific regulator of glucocorticoid response. Endocr Rev. 2004;25:831–866. doi: 10.1210/er.2003-0031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venero C, Borrell J. Rapid glucocorticoid effects on excitatory amino acid levels in the hippocampus: a microdialysis study in freely moving rats. Eur J Neurosci. 1999;11:2465–2473. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00668.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan ZK, Chenail E, Xiang J, Li HQ, Ipek M, Bard J, Svenson K, Mansour TS, Xu X, Tian X, Suri V, Hahm S, Xing Y, Johnson CE, Li X, Qadri A, Panza D, Perreault M, Tobin JF, Saiah E. Efficacious 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type I inhibitors in the diet-induced obesity mouse model. J Med Chem. 2009;52:5449–5461. doi: 10.1021/jm900639u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson RS, Barnes LL, Bennett DA, Li Y, Bienias JL, Mendes de Leon CF, Evans DA. Proneness to psychological distress and risk of Alzheimer disease in a biracial community. Neurology. 2005;64:380–382. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000149525.53525.E7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winblad B, Jelic V. Long-term treatment of Alzheimer disease: efficacy and safety of AChE-Is. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2004;18(Suppl 1):S2–S8. doi: 10.1097/01.wad.0000127495.10774.a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yau JL, Noble J, Kenyon CJ, Hibberd C, Kotelevtsev Y, Mullins JJ, Seckl JR. Lack of tissue glucocorticoid reactivation in 11β -hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 knockout mice ameliorates age-related learning impairments. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:4716–4721. doi: 10.1073/pnas.071562698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yau JL, McNair KM, Noble J, Brownstein D, Hibberd C, Morton N, Mullins JJ, Morris RG, Cobb S, Seckl JR. Enhanced hippocampal long-term potentiation and spatial learning in aged 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 knock-out mice. J Neurosci. 2007;27:10487–10496. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2190-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh VSC, Patel JV, Yong H, Kurukulasuriya R, Fung S, Monzon K, Chiou W, Wang J, Stolarik D, Imade H, Beno D, Brune M, Jacobson P, Sham H, Link JT. Synthesis and biological evaluation of heterocycle containing adamantane 11β-HSD1 inhibitors. Bioorg Medicinal Chem Lett. 2006;16:5414–5419. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.07.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]