Abstract

The experience of racial or ethnic discrimination is a salient and severe stressor that has been linked to numerous disparities in important outcomes. Yet, the link between perceived discrimination and marital outcomes has been overlooked by research on relationship stressors. The current study examined this link and tested whether ethnic identity buffered the relationship between discrimination and ratings of marital quality and verbal aggression. A sample of 330 Latino newlyweds completed measures of perceived discrimination, ethnic identity, spouse’s verbal aggression, and marital quality. Each spouse’s interviewer also independently rated marital quality. Dyadic analyses revealed that husbands’ experience of discrimination negatively predicted wives’ marital quality, but only for husbands with weak ethnic identity. Wives whose husbands had strong ethnic identity were buffered from this effect. Identity also buffered the relationship between husband’s discrimination and verbal aggression toward their wives, and this effect mediated the relationship between discrimination, identity, and marital quality.

Keywords: Marriage, Discrimination, Racial Identity, Marital Satisfaction, Verbal Aggression

For a wide range of important life outcomes, persistent racial and ethnic disparities have been linked to the experience of racial discrimination. Whether those disparities are in employment (DeFreitas, 1991; Schwartzman, 1997; Wilson, 1996), wealth accruement (Hao, 2007; Oliver & Shapiro, 2006; Shapiro, 2004), housing (Jargowsky, 1997; Massey & Denton, 1993), healthcare (Budrys, 2003), or educational attainment (Bowen & Bok, 1998; Massey, Charles, Lundy, & Fischer, 2003; Steele, 2010), the experience of discrimination on the basis of race or ethnicity has been associated with disparate outcomes between racial and ethnic groups. The attention to racial discrimination in these domains makes sense: when confronted with racial disparities, scholars and laypeople alike tend to believe that racial bigotry is lurking somewhere close by (Goff, in press; Goff & Kahn, under review).

Yet, the same cannot be said for understanding racial and ethnic disparities in marital outcomes, despite extensive evidence of such disparities. For example, compared to White couples, Black and Latino couples report higher rates of intimate partner violence (Caetano, Cunradi, Schafer, & Clark, 2000). Compared to White women, Black women experience higher rates of divorce (Bramlett & Mosher, 2002; Raley & Bumpass, 2003), and are significantly less likely to ever marry over the life course (Bramlett & Mosher, 2002). Latino couples tend to divorce slightly less than Black or White couples, but divorce and separation among Latino couples are on the rise (Kreider & Simmons, 2003; Padilla & Borrero, 2006). Furthermore, marital disruption among Latino couples is associated with increased acculturation (Frisbie, 1986; Oropesa & Landale, 2004; Padilla & Borrero, 2006), such that more acculturated Latino couples (e.g., second generation US citizens, those with more education) are more likely to divorce than are less acculturated couples.

In light of the associations between race and marital outcomes, and the attention to the relationship between discrimination and racial and ethnic disparities in other domains, it is striking that, to date, few researchers have examined the possible role that the experience of discrimination plays in producing disparities in marriage. There is ample reason to believe, however, that the experience of racial discrimination in one domain of life can have implications for other domains. For example, perceived discrimination has been consistently linked to a wide range of negative outcomes such as hypertension (Clark, Anderson, Clark, & Williams, 1999; Williams & Neighbors, 2001), cardiovascular reactivity (Richman, Bennett, Pek, Siegler, & Williams Jr, 2007), psychological distress (Gibbons, Gerrard, Cleveland, Wills, & Brody, 2004; Williams, Yu, Jackson, & Anderson, 1997), decreased subjective well-being (Jackson et al., 1996), and negative health behaviors (e.g., substance use; Gibbons et al., 2010; Gibbons, et al., 2004; see Mays, Cochran, & Barnes, 2007 for a review). Given the documented breadth of the correlates of racial discrimination, this experience seems likely to be associated with marital outcomes as well. Rather than marriage being a safe haven from the effects of discrimination, it seems more plausible that we simply know less about how the experience of discrimination may be associated with marital outcomes.

The present research was designed to fill this gap in the literature. Toward this end, the rest of this introduction is organized into four sections. First, we characterize the experience of discrimination as a source of stress and review existing models of stress and marriage, noting how these models might be applied toward understanding the specific relationship between discrimination and marital outcomes. Second, we describe prior research highlighting ethnic identity as a potential moderator of the association between discrimination and marital outcomes. Third, we describe research identifying verbal aggression as a potential mediator of this relationship, especially for husbands. Finally, we summarize the current study, which draws upon a sample of lower-income Latino newlyweds to evaluate how well existing models of stress in relationships apply toward understanding the interpersonal implications of discrimination within this understudied population.

Discrimination as a Relationship Stressor

Although the experience of racial or ethnic discrimination is a significant life stressor (Clark, et al., 1999), this fact has rarely been reflected in research on stress in relationships, perhaps because the vast majority of this research has addressed samples composed primarily of white, college-educated, middle-class couples (Karney & Bradbury, 1995). Blacks and Latinos, however, frequently report being the targets of discrimination (e.g., Dovidio, Gluszek, John, Ditlmann, & Lagunes, 2010; Pérez, Fortuna, & Alegría, 2008), and describe these experiences as among the most stressful in their lives (Cervantes, Padilla, & de Snyder, 1991). Although much of what we know about discrimination comes from studies of African Americans (Dovidio & Esses, 2001), Latinos represent the fastest growing ethnic group in the United States (Census Bureau, 2009), and furthermore are disproportionately represented among the lower-income married couples that are at highest risk for experiencing marital disruptions (Simms, Fortuny, & Henderson, 2009). Thus, concern over how the stress of experiencing discrimination may be associated with negative marital outcomes directs attention toward the experiences of Latino couples specifically.

How might Latinos’ experience of discrimination affect their relationships? Existing models and previous research suggest that, in general, stressors external to a couple are associated with decreased relationship satisfaction and increased risk of dissolution (e.g., Bolger, Foster, Vinokur, & Ng, 1996; Conger et al., 1990; Cutrona et al., 2003; Neff & Karney, 2004). Building on Hill’s (1949) original ABCX Model of family crises, contemporary frameworks generally make two claims about how these effects operate. For example, the Vulnerability-Stress-Adaptation (VSA) model of marriage (Karney & Bradbury, 1995) proposes, first, that the effects of stress on marital outcomes are moderated by vulnerabilities and strengths within the individual spouses, and, second, that stress effects are mediated by the direct effects of stress on interactions and adaptive processes between the spouses. Research elaborating on the association between stress and relationship quality generally supports these propositions, showing, for example, that preexisting vulnerabilities like neuroticism exacerbate the negative association between stressful life events and relationship quality (a moderation effect; Hellmuth & McNulty, 2008) or that financial stress hurts marriages by making effective problem-solving in the relationship more difficult (a mediation effect; Conger, et al., 1990).

Do available frameworks for understanding stress in relationships apply equally toward understanding the relationship between discrimination and relationship quality? Although research directly estimating the association between discrimination and relationship quality is rare, previous studies have demonstrated links between the perception of discrimination and an individual’s own perceptions of his or her marriage (Lincoln & Chae, 2010; Murry, Brown, Brody, Cutrona, & Simons, 2001). These researchers found that, among African American married individuals, increased perceptions of discrimination were associated with decreased marital satisfaction. The first goal of the current study was to extend this previous research in two directions: first, by examining these associations in the relationships of Latinos, and second, by addressing couples, thereby allowing estimates of the extent to which one spouse’s experience of discrimination is related to their partners’ experiences of the relationship.

Moderation: Strong Ethnic Identity as a Buffer

As much as the experience of discrimination based on race may produce vulnerabilities in non-White marriages, racial and ethnic minorities may also have a unique source of strength that they can draw on to cope with and even ward off the emotional consequences of discrimination: their racial/ethnic identity. Assigning significance and meaning to one’s race or ethnicity in one’s self-concept (Sellers, Rowley, Chavous, Shelton, & Smith, 1997; Sellers, Smith, Shelton, Rowley, & Chavous, 1998) can serve as a resource for coping with stress because it provides a sense of belonging to a group (Chatman, Eccles, & Malanchuk, 2005), and it provides one with a worldview in which to make sense of maltreatment by members of an outgroup (Sellers, et al., 1997; Shelton et al., 2005). Although there are also downsides to having a strong sense of ethnic identity (e.g., people high in ethnic identity tend to perceive more discrimination and have less trust of outgroup members than do those low in identity; Sellers & Shelton, 2003), a strong sense of identity has been shown to serve as a buffer against race-related stressors (Chatman, et al., 2005; Crocker & Major, 1989; Shelton, et al., 2005). Specifically, research has demonstrated that a strong sense of ethnic identity is associated with less vulnerability to the negative impact of discrimination on psychological well-being (e.g., Hansen & Sassenberg, 2006; Neblett, Shelton, & Sellers, 2004; see Shelton, et al., 2005 for a review).

The possibility that a strong ethnic identity protects marriages from the consequences of discrimination has yet to be studied directly. The second goal of the current study was to address this oversight and test the proposition that the association between one spouse’s experience of discrimination and both partners’ relationship satisfaction is moderated by his or her level of ethnic identity.

Mediation: Verbal Aggression as a Maladaptive Response

Experiencing discrimination generally invokes feelings of anger (Broudy et al., 2007; Gibbons, et al., 2010; Hansen & Sassenberg, 2006). Accordingly, experiencing discrimination has also been associated with externalized responses such as yelling and throwing things (Scott & House, 2005) and violent behaviors (e.g., fighting; Caldwell, Kohn-Wood, Schmeelk-Cone, Chavous, & Zimmerman, 2004). The VSA model (Karney & Bradbury, 1995) points to these direct correlates of discrimination as potential mediators of the association between discrimination and marital outcomes. In other words, spouses who experience discrimination outside the home should be more likely to direct angry outbursts or threats toward their spouse within the home, and these maladaptive behaviors should mediate the associations between discrimination and relationship quality.

We expected that increased discrimination would predict more interpersonal aggression from husbands and wives, but that this association would be stronger for husbands, for two reasons. First, husbands have been shown to express more negative relationship behaviors in response to stress than do wives (Conger, et al., 1990). Second, being the target of discrimination in particular involves a loss of power (Cook, Arrow, & Malle, 2011), and stressors associated with a loss of power are more strongly associated with relationship aggression for husbands than wives (Cano & Vivian, 2003).

Overview of the Current Study

Although perceived discrimination is known to be associated with poor mental health and aggressive behavior in individuals, the possibility that one spouse’s experience of discrimination might ripple throughout a marriage has been overlooked. Because discrimination is likely to be an especially salient challenge in the lives of lower-income minority couples, and because couples in this population are disproportionately likely to identify as Latino, the current study examined moderators and mediators of the association between perceived discrimination and marital satisfaction in a sample of Latino newlyweds living in low-income neighborhoods.

To this end, spouses who had recently entered their first marriages were asked about their relationship, the quality of their interactions with each other, their own recent experiences of discrimination, and how central their ethnicity was to their self-concept. Analyzing these data using the Actor-Partner Interdependence Model (APIM; Kenny, Kashy, & Cook, 2006), we hypothesized that discrimination experienced by each spouse would negatively predict his or her own experience of relationship quality (an actor effect), replicating past research (Lincoln & Chae, 2010; Murry, et al., 2001). Extending that research, we expected that, controlling for the actor effect, each spouse’s own experiences of discrimination would be negatively associated with the partner’s experience of the marriage (a partner effect). With respect to moderation, we expected that the strength of these associations would be moderated by each spouse’s level of ethnic identity. Specifically, we expected that, for spouses with a weak sense of ethnic identity, the experience of discrimination outside the home would be negatively related to their own and their partner’s experience of the marriage. However, when spouses had a strong sense of ethnic identity, we expected that their experience of discrimination would not be associated with their own or their partner’s experience of the marriage.

With respect to mediation, we expected that a spouse’s experiences of discrimination would positively predict verbal aggression toward the partner (as reported by the partner), and that this association would also be moderated by the spouse’s level of ethnic identity. Spouses’ verbal aggression was predicted to mediate the association between discrimination, ethnic identity, and their partner’s relationship quality, and we expected this mediation effect to be stronger for husbands than for wives. We only predicted partner effects for the mediation analysis because we hypothesized that the mechanism by which discrimination affects the marriages of weakly identified spouses is through their behavior toward their partner. For example, we predicted that weakly identified husbands who experience discrimination would be verbally aggressive toward their wives, and that this verbal aggression would account for the relationship between husbands’ experience of discrimination and their wives’ lower perceptions of relationship quality. This hypothesis was represented by the partner effect in the analysis, whereas the actor effect represented, for example, how husbands’ experience of discrimination and ethnic identity were associated with their own perceptions of relationship quality. Both the actor and the partner effects are estimated by the APIM, however, so, even though it did not hold theoretical interest, this effect was included in the analysis.

Method

Sampling

Our sampling procedure was designed to yield a random sample of first-married newlywed couples in which both the husband and wife were of Latino ethnicity and lived in low-income neighborhoods. To accomplish this, participants were recruited from Los Angeles County, a region with a large and diverse low-income population. Recently married couples were identified through marriage license applications which were then matched with census data to identify applicants who resided in low-income communities, defined as census block groups wherein the median household income was no more than 160% of the 1999 federal poverty level for a four person family (a similar definition has been used in analyses of the National Survey of Family Growth; e.g., Bramlett & Mosher, 2002). Next, names on the licenses were weighted using data from a recently developed Bayesian Census Surname Combination, which integrates both Census and surname information to produce a multinomial probability of membership in each of four racial/ethnic categories (Latino, Black, Asian, White/other) based on residential address and surname. Couples were selected from the total population of recently married couples using probabilities proportionate to the ratio of target prevalences to the population prevalences, weighted by the couple’s average estimated probability of being Latino. These couples were contacted by phone and screened to ensure that they had actually married, that neither partner had been previously married, and that both spouses identified as Latino.

Participants

The first 330 couples identified with the above procedures comprised the sample. Marriages averaged 4.9 months in duration (SD = 2.6), and couples had an average of .68 children (SD = 1.02). Husbands’ mean age was 27.3 (SD = 5.5) and wives’ mean age was 25.6 (SD = 5.0). The wives had a mean income of $22,026 (SD = $21,432) and husbands had a mean income of $29,409 (SD = $19,822). All participants identified themselves as Latino. For husbands, 54% were born in the US, 33% were born in Mexico, and 13% were born in other Latin or South American countries. For wives, 59% were born in the US, 31% were born in Mexico, and 10% were born in other Latin or South American countries. Overall, 70% of respondents were of Mexican descent (either by birth or by their mother’s birthplace).

Procedure

Couples were visited in their homes by two trained interviewers who conducted the interviews orally, either providing participants with choice options or, when necessary, coding participants’ responses into pre-established categories. Interviews were conducted in English (62.9%), Spanish (19.2%), or both English and Spanish (17.9%). In order to allow participants to speak freely about the marital relationship, husbands and wives were interviewed in separate locations, outside of hearing distance from each other (i.e., in separate rooms, or inside and outside the home). Care was taken to assure participants that their responses to the interview would not be shared with their spouse, and that their identity would be kept confidential. The interviews covered a range of topics, including demographics, family background, and relationship experiences and attitudes. Following the interview, each interviewer rated his or her own evaluation of the quality of the marriage. Couples were debriefed and compensated $75.

Measures

Perceived experience of discrimination.

We assessed participants’ perceived experience of day-to-day discrimination using questions adapted from the Midlife Development in the United States (MIDUS) survey (Kessler, Mickelson, & Williams, 1999). Interviewers instructed participants that they were “interested in finding out if other people discriminate against you. Specifically, I want to ask you a series of questions about how people might treat you because of your gender, your ethnicity, or your English speaking ability.” Participants were asked to indicate on a scale of 0 (“never”) to 3 (“often”) how often they experienced each of six types of discrimination: being treated as inferior, people acting “as if they are afraid of you,” being treated with less respect than others, people acting “as if you are dishonest,” being called names or insulted, and being threatened or harassed. Responses to these items were summed to create a perceived discrimination scale (Cronbach’s alpha = .75 for husbands and .69 for wives). Although this operationalization of discrimination encompassed both ethnic and gender discrimination, when most minorities think about their experiences with discrimination, they generally think about racial/ethnic discrimination (Levin, Sinclair, Veniegas, & Taylor, 2002).

Ethnic identity.

Ethnic identity was assessed using two items adapted from the Centrality subscale of the Multidimensional Inventory of Black Identity (Sellers, et al., 1997). These two items were: “In general, my ethnicity is an important part of my self-image” and “I have a strong sense of belonging to people from my ethnicity.” Participants’ indicated their agreement with each of these statements using a scale from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. The two items were summed to create an ethnic identity scale (Cronbach’s alpha = .75 for husbands and .72 for wives).

Relationship quality.

We assessed relationship quality using two measures. Participants’ own perceived marital quality was assessed using a 9-item scale. Five of the items assessed participants’ satisfaction with the amount of time the couple spent together, their sexual relations with their spouse, the amount of support provided by the spouse, the spouse’s contribution to household chores, and a general indicator of satisfaction with the marriage. These items were rated on a 5-point scale from 1 = very dissatisfied to 5 = very satisfied. The other four items asked participants to assess how much they felt they could share their thoughts and dreams with their spouse, how much they trusted their spouse (both rated on a 4-point scale from 1 = not at all to 4 = completely), how well the couple communicated during disagreements, and how well their partner understood their hopes and dreams (both rated on a 4-point scale from 1 = not at all to 4 = very well). Since the items used different response options, we first standardized all nine items then calculated the average of the standardized items to form a relationship quality scale (Cronbach’s alpha = .75 for husbands and .79 for wives).

In order to ensure that any relationships between predictor variables and marital quality were not solely the result of shared method variance, we also asked each participant’s interviewer to assess the quality of the relationship. After completion of the in-home assessment, interviewers completed a questionnaire that included two questions assessing their perception of the relationship. First, interviewers were asked, “from what you have learned today, how would you rate the quality of this marriage?” This rating was made on a 5-point scale from 0 = very bad marriage to 4 = very good marriage. Next, interviewers were asked to rate, on a 4-point scale from 0 = not at all likely to 3 = extremely likely, “in your opinion, how likely is it that this marriage will last?” These two items were standardized then averaged to create an interviewer’s perception of relationship quality scale (Cronbach’s alpha = .85 for husbands and .87 for wives).

Verbal aggression.

We assessed participants’ reports of their spouse’s level of verbal aggression toward them using items from the Verbal Aggression subscale of the Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS; Straus, 1979). Participants were asked to think about the last nine months and to indicate whether or not their spouse had ever performed a specific behavior during an argument. If participants indicated that their spouse had performed one of the behaviors, interviewers asked them to indicate how often this behavior occurred: once or twice, several times, or often. Each behavior was then coded on a 4-point scale from 0 = the behavior did not occur to 3 = it occurred often. We formed a cumulative index of verbal aggression by summing the frequency of three behaviors: how often a spouse insulted or swore at the participant, how often the spouse stomped out of the room or left the house during an argument, and how often the spouse threatened to hit the respondent.

Analysis Strategy

Analyses were conducted using the MIXED procedure in SPSS. Following Kenny, Kashy, and Cook (2006), we treated couples as distinguishable dyads (i.e., husbands can be distinguished from wives). This allowed us to construct models with separate actor and partner effects for both husbands and wives (i.e., a two-intercept model; Kenny, et al., 2006). Thus, we were able to test whether wives’ experience of discrimination significantly predicted both their own relationship outcomes and the outcomes for their husbands, while simultaneously testing the same pathways from husbands’ experiences to husbands’ outcomes and from husbands’ experiences to wives’ outcomes. Interactions were included in the models where noted, and the interpretation of these interactions is similar to the interpretation of interactions in linear regression models. Note that, although much of the following analysis focuses on the partner effects in each model, the actor effects were also estimated in all of the models. All predictor variables were grand-mean centered.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Table 1 displays means, standard deviations, and correlations among all variables. The perception of discrimination was not significantly correlated with ethnic identity for husbands or wives, indicating that these variables were independent. Ethnic identity was not significantly correlated with the measures of relationship quality or with verbal aggression. Unless otherwise reported, the main effect of ethnic identity was not significant in any of the dyadic analyses reported below. Consistent with previous research (e.g., Sellers & Shelton, 2003), husbands reported experiencing more discrimination than did wives, paired t(329) = 6.31, p < .001. Husbands also rated the quality of their marriages higher than did wives, paired t(329) = 2.84, p = .005, although interviewers assessed marital quality as higher for wives than for husbands, paired t(324) = −2.34, p = .02. Husbands reported more verbal aggression by their spouse than did wives, paired t(329) = 2.88, p = .004. Husbands and wives did not differ in ethnic identity, paired t(327) = 1.35, p = .18.

Table 1.

Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations between Variables

|

M (SD) |

1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Wife's relationship quality | −0.05 (0.63) |

-- | |||||||||

| 2 Husband's relationship quality | 0.05 (0.54) |

.361* | -- | ||||||||

| 3 Wife's interviewer's rating of marital quality | 0.12 (1.93) |

.600* | .313* | -- | |||||||

| 4 Husband's interviewer's rating of marital quality | −0.12 (1.81) |

.322* | .417* | .505* | -- | ||||||

| 5 Wife's experience of discrimination | 2.17 (2.34) |

−.203* | −.142* | −.136* | .041 | -- | |||||

| 6 Husband's experience of discrimination | 3.47 (3.12) |

−.068 | −.267* | −.049 | −.133* | .075 | -- | ||||

| 7 Wife's ethnic identity | 7.85 (1.65) |

−.030 | .060 | .058 | −.006 | −.027 | .061 | -- | |||

| 8 Husband's ethnic identity | 7.67 (1.88) |

.107 | .088 | .066 | .056 | −.024 | .006 | .156* | -- | ||

| 9 Wife's report of verbal aggression by husband | 0.99 (1.25) |

−.477* | −.247* | −.463* | −.279* | .124* | .098 | .054 | −.074 | -- | |

| 10 Husband's report of verbal aggression by wife | 1.22 (1.28) |

−.239* | −.403* | −.239* | −.317* | .061 | .230* | .040 | −.099 | .344* | -- |

Notes: Items comprising relationship quality and interviewers’ ratings of marital quality were standardized.

= p < .05

In sum, all measures performed as expected, justifying further analyses of our model. We first report the basic APIM analysis examining main effects of discrimination and ethnic identity on marital outcomes. We next report the results of the interaction between ethnic identity and discrimination. It is important to note that all analyses control for shared variance (interdependence) between husbands’ and wives’ data.

Marital Quality

We first examined the association between perceived discrimination and one’s own marital outcomes (actor effects in the APIM). Replicating past research (Lincoln & Chae, 2010; Murry, et al., 2001), the more that both husbands and wives perceived that they were discriminated against, the lower they rated the quality of their marriage, wives’ b = −.054, β = −.258, t(327) = −3.67, p < .001; husbands’ b = −.045, β = −.215, t(327) = −4.86 p < .001, and the strength of this association did not significantly differ between husbands and wives, t(490.8) = 0.59, p = .56. Although replicating these associations among Latino couples is an important extension of prior work, the primary goal of this study was to examine how perceived discrimination relates to one’s partner’s outcomes—the partner effects. Indeed, controlling for the actor effects, wives’ perceived discrimination significantly predicted husbands’ ratings of marital quality such that the more that wives’ felt like they were discriminated against the lower their husbands rated the quality of their marriage, b = −.029, β = −.136, t(327) = −2.32 p = .02. Contrary to our expectations, the same was not true for husbands’ perceptions of discrimination, which did not on average significantly predict wives’ ratings of marital quality, b = −.011, β = −.052, t(327) = −0.98, p = .33, although the strength of these two associations did not significantly differ, t(551.5) = −1.14, p = .25.

We next examined the interviewers’ ratings of marital quality using the same model. As with relationship quality, wives’ and husbands’ perceptions of discrimination had a significant negative actor effect on interviewers’ ratings of marital quality, wives’ actor b = −0.11, β = −.165, t(324) = −2.41, p = .02, husbands’ actor b = −0.08, β = −.118, t(322.7) = −2.45, p = .02, and the size of these associations did not differ significantly between husbands and wives, t(458.7) = 0.41, p = .68. However, neither partner effect significantly accounted for variance in the interviewer ratings, wives’ partner (i.e., the association between husbands’ discrimination and the wives’ interviewers’ ratings of marital quality) b = −0.024, β = −.037, t(324) = −0.71, p = .48, husbands’ partner b = 0.38, β = .057, t(323.1) = 0.88, p = .38 .

Moderating role of ethnic identity.

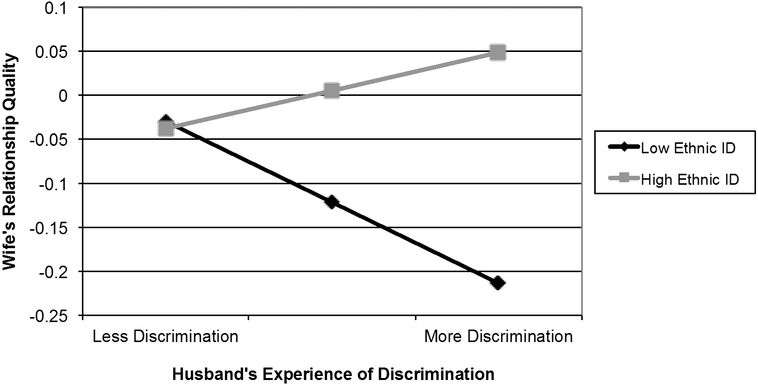

We examined the role of ethnic identity as a buffer against discrimination by entering the interaction of perceived discrimination and ethnic identity into the model. Examining the actor effects first, contrary to our hypothesis, these interactions did not significantly account for participants’ own ratings of marital quality among wives or husbands, wives’ actor b = −.015, β = −.127, t(321) = −1.66, p = .10, husbands’ actor b = .007, β = .058, t(321) = 1.50, p = .13. However, as predicted, the partner effect linking husbands’ predictors to wives’ outcomes was significant, b = .012, β = .097, t(321) = 2.12, p = .04. As shown in Figure 1, for wives whose husbands had weaker ethnic identity, the more that their husbands perceived that they were discriminated against, the lower the wives’ ratings of marital quality, slope at one SD below the mean b = −.030, t(321) = −2.09, p = .04. Wives whose husbands had stronger ethnic identity, however, showed no relationship between husbands’ discrimination and wives’ marital quality, slope at one SD above the mean b = .014, t(321) = 0.95, p = .34. Thus, husbands’ ethnic identity appears to buffer their wives from the negative association between husbands’ discrimination and marital quality. The same was not true for wives’ ethnic identity: the interaction of wives’ ethnic identity and wives’ discrimination on husbands’ marital quality was not significant, b = .006, β = .049, t(321) = 0.76, p = .45. Despite the fact that the estimate of moderation was significant for husbands and not for wives, the direct test of the difference between husbands and wives did not reach significance, t(536.9) = −0.61, p = .54.

Figure 1.

Moderating role of husbands’ ethnic identity on the relationship between husbands’ experience of discrimination and wives’ relationship quality.

Note: lines are graphed at one standard deviation above and below the mean. Simple slopes tests were significant for husbands with low ethnic identity, slope b = −.030, t(321) = −2.09, p = .04, and not significant for husbands with high ethnic identity, slope b = .014, t(321) = 0.95, p = .34.

Substituting interviewers’ ratings of marital quality as the outcome variable yielded even stronger support for our hypothesis. In this analysis, a significant husbands’ ethnic identity by husbands’ discrimination interaction emerged for husbands’ interviewer ratings of marital quality (the actor effect), b = .042, β = .113, t(316.5) = 2.68, p = .008, indicating that the relationship between husbands’ experience of discrimination and husbands’ marital quality, from the perspective of the interviewer, was moderated by husbands’ ethnic identity. The same was not true for wives, whose ethnic identity did not moderate the association between wives’ experience of discrimination and their interviewers’ ratings of marital quality, b = −.031, β = −.083, t(318) = −1.11, p = .27, and this moderation effect significantly differed between husbands and wives, t(440.4) = 2.30, p = .02.

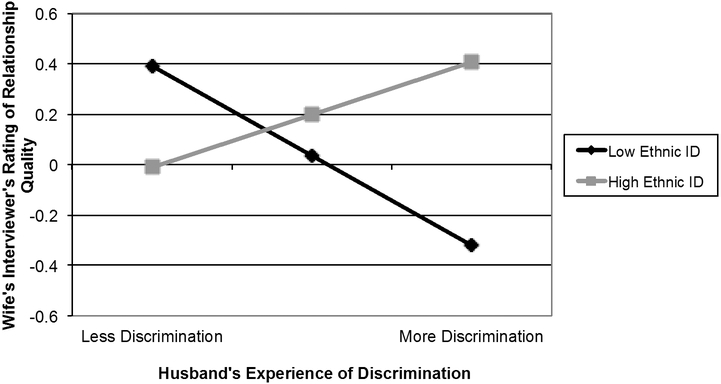

As with wives’ self-reports of relationship quality, the interaction between husbands’ experience of discrimination and husbands’ ethnic identity significantly predicted wives’ interviewer ratings of marital quality (the partner effect), b = .048, β = .129, t(318) = 2.89, p = .004. As shown in Figure 2, for wives whose husbands had weaker ethnic identity, the more that their husbands perceived that they were discriminated against, the lower the wives’ interviewers’ ratings of marital quality, slope at one SD below the mean b = −.114, t(318) = −2.50, p = .01. Wives whose husbands had stronger ethnic identity, however, did not show a signficant relationship between husbands’ discrimination and the wives’ interviewers’ ratings of marital quality, slope at one SD above the mean b = .067, t(318) = 1.45, p = .15. The interaction of wives’ ethnic identity and wives’ experience of discrimination did not significantly predict their husbands’ interviewers’ ratings of marital quality, b = .036, β = .095, t(317) = 1.36, p = .18, although this moderation effects did not significantly differ between husbands and wives, t(460.7) = −0.41, p = .68. Thus, on two measures of relationship quality—one recorded by the spouse and one recorded by an outside observer—husbands’ experience of discrimination was only negatively associated with spouses’ marital quality for husbands with weaker ethnic identity; those with stronger ethnic identity were buffered from this negative relationship.

Figure 2.

Moderating role of husbands’ ethnic identity on the relationship between husbands’ experience of discrimination and wives’ interviewers’ ratings of relationship quality.

Note: lines are graphed at one standard deviation above and below the mean. Simple slopes tests were significant for husbands with low ethnic identity, slope b = −.114, t(318) = −2.50, p = .01, and not significant for husbands with high ethnic identity, slope b = .067, t(318) = 1.45, p = .15.

Discrimination Predicting Verbal Aggression

We next examined the relationship between discrimination, ethnic identity, and reports of verbal aggression by the spouse. For these models, the partner effects are particularly relevant. Since respondents rated the level of verbal aggression by their spouse (i.e., a husband’s rating reflected the level of verbal aggression by his wife), the partner effects in these models estimated how much respondents’ experience of discrimination was associated with their own verbal aggression toward their spouse (as recorded by their spouse). Actor effects, on the other hand, estimated how much respondents’ own experience of discrimination was related to their ratings of their spouse’s verbal aggression. These actor effects were significant in both spouses [wives’ b = .063, β = .140, t(327) = 2.14, p = .03; husbands’ b = .093, β = .207, t(327) = 4.21, p < .001] and the difference between spouses was not significant[t(529.7) = 0.87, p = .39], but these estimates may be inflated by shared method variance, as the same respondent reported both the discrimination and the aggression. The partner effects involve two different respondents, and so avoid this problem, but neither of the partner main effects on verbal aggression was significant, i.e., the experience of discrimination by one spouse was not significantly associated with reporting greater verbal aggression from the other spouse, wives’ b = .036, β = .080, t(327) = 1.63, p = .10; husbands’ b = .024, β = .053, t(327) = 0.81, p < .42.

Moderating role of ethnic identity.

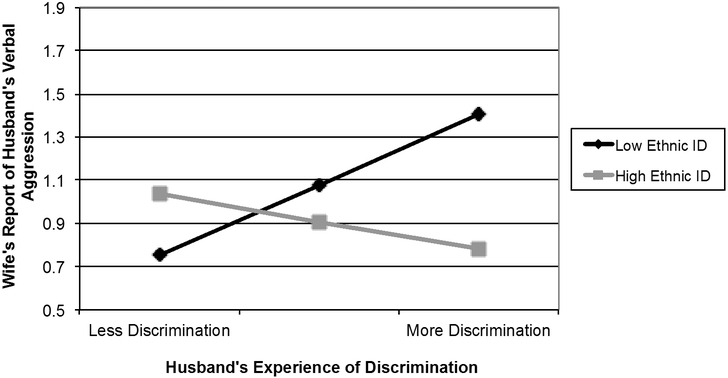

We next tested the interaction between perceived discrimination and ethnic identity on reports of verbal aggression. Again, we concentrated on the partner effects of these interactions, but we estimated both the actor effects and the partner effects in the same model. For wives’ reports of verbal aggression by their husbands, a significant interaction between husbands’ ethnic identity and husbands’ experience of discrimination emerged, b = −.038, β = −.151, t(321) = −3.56, p < .001. However, the interaction of wives’ experience of discrimination and wives’ ethnic identity predicting husbands’ reports of verbal aggression by their wives was not significant, wives’ partner b = .020, β = .077, t(321) = 1.07, p = .29. Furthermore, these two interactions significantly differed from one another, t(493.7) = 2. 74, p = .006. As shown in Figure 3, consistent with our predictions, husbands’ with weaker ethnic identity demonstrated a positive relationship between their own experience of discrimination and their level of verbal aggression against their wives (as reported by their wives; slope at one SD below the mean b = .104, t(321) = 3.54, p < .001). Husbands with stronger ethnic identity showed no such relationship, slope at one SD above the mean b = −.040, t(321) = −1.33, p = .18. No other ethnic identity by discrimination interactions approached significance, wives’ actor b = .013, β = .051, t(321) = 0.72, p = .47; husbands’ actor b = −.012, β = −.048, t(321) = −1.11, p = .27.

Figure 3.

Moderating role of husbands’ ethnic identity on the relationship between husbands’ experience of discrimination and wives’ reports of verbal aggression by their husbands.

Note: lines are graphed at one standard deviation above and below the mean. Simple slopes tests were significant for husbands with low ethnic identity, slope b = .104, t(321) = 3.54, p < .001, and not significant for husbands with high ethnic identity, slope b = −.040, t(321) = −1.33, p = .18.

Mediation analysis

We expected that the increased verbal aggression enacted by husbands with weaker ethnic identity would account for the association between their experiences of discrimination and wives’ and interviewers’ lower ratings of relationship quality. To test this hypothesis, we performed mediation analyses (Baron & Kenny, 1986). Since the interaction of husbands’ ethnic identity and husbands’ discrimination significantly predicted verbal aggression by the husband, step 1 of the mediation test was satisfied.

We first tested the mediating role of verbal aggression on wives’ reports of marital quality. Step 2 of the mediation test involves demonstrating a significant path from the mediator to the outcome variable in the presence of the predictor (Baron & Kenny, 1986), and this requirement was satisfied: when entered into a model predicting wives’ ratings of marital quality from the interaction of husbands’ discrimination and ethnic identity, wives’ reports of verbal aggression by their husbands significantly predicted wives’ ratings of marital quality, b = −.213, β = −.457, t(319) = 8.02, p < .001. Furthermore, the indirect effect of husbands’ ethnic identity by discrimination interaction on wives’ marital quality through verbal aggression was significant, Sobel’s = 3.26, p = .001. When verbal aggression was included in the model, the interaction of husbands’ ethnic identity and discrimination no longer significantly predicted wives’ marital quality, b = .003, β = .025, t(319) = 0.59, p = .56. Examination of the mediating role of verbal aggression on interviewers’ ratings of marriage quality yielded parallel results. Wives’ reports of their husbands’ verbal aggression significantly predicted interviewers’ ratings of marital quality, b = −.627, β = −.426, t(316) = 7.61, p < .001, and the indirect effect of the interaction between husbands’ ethnic identity and discrimination and interviewers’ ratings of marital quality through verbal aggression was significant, Sobel’s = 3.23, p = .001. In addition, when verbal aggression was entered into the model as a mediator, the direct effect of husbands’ ethnic identity by discrimination on interviewers’ ratings of marital quality dropped to non-significance, b = .023, β = .060, t(316) = 1.47, p = .14. Thus, consistent with our predictions, husbands’ verbal aggression mediated the interaction of husbands’ ethnic identity and experience of discrimination on both measures of marital quality. These analyses suggest that the buffering role of husbands’ ethnic identity is at least partly due to the fact that husbands with stronger ethnic identity are less likely to react to discrimination by acting verbally aggressive toward their wives.

Because wives’ experience of discrimination had a direct effect on husbands’ relationship quality ratings, we conducted a meditational analysis to test whether wives’ verbal aggression (as reported by their husbands) mediated this effect. This analysis failed to satisfy step 2—as reported earlier, the relationship between wives’ discrimination and husbands’ reports of wives’ verbal aggression was not significant, b = .024, β = .053 t(327) = .81, p = .42—so verbal aggression did not mediate this relationship.

Discussion

For minority couples, the experience of racial or ethnic discrimination is a salient and severe stressor; one that has been linked to numerous racial and ethnic disparities in important outcomes. Yet, the link between perceived discrimination and marital outcomes has been overlooked by research on the effects of stress on relationships. Addressing this gap, the current study demonstrated that the experience of discrimination may have effects that spread beyond the individual. Across two sources of information on the marriage—the respondent and an outside observer—the experience of discrimination predicted lower ratings of marital quality. For wives, these experiences were also independently related to their husbands’ perception of marital quality, but for husbands, the extent to which their experience of discrimination predicted their wives’ marital quality depended upon the strength of the husband’s ethnic identity. For husbands with weaker ethnic identity, the more that they experienced discrimination, the lower their own and their wives’ satisfaction with their marriage. For husbands with stronger ethnic identity, however, the experience of discrimination was unrelated to either spouse’s ratings of the marriage. This moderated effect was in turn mediated by husbands’ verbal aggression toward their wives. Thus, it seems that the stress of experiencing discrimination can seep into marriages both through its negative implications for one’s own perceptions of marital quality, and through its associations with the negative behaviors of low-identified husbands toward their wives.

Our confidence in these results is enhanced by several strengths in the methods and design of this study. First, in contrast to the majority of research on stress and relationships that has addressed primarily White, middle-class couples, these analyses addressed an as yet understudied population—low-income Latino couples—in which issues relating to discrimination and ethnic identity are likely to be highly relevant and salient. Second, all of the couples were first-married newlyweds, assessed within the first 6 months of their weddings. Studying newlyweds as opposed to more established marriages helps ensure that less stable couples have an equal chance of being included in the research; if more established marriages had been sampled, there is a possibility that the most vulnerable couples would have already exited the sampling frame through separation or divorce. Because experiences of newlyweds predict marital quality and divorce in later years (e.g., Rogge & Bradbury, 1999), understanding the processes that affect relationship quality at this stage of marriage provides insight into the potential trajectories of these relationships. Third, the presence of data from both spouses in each couple offered a window into both actor effects and partner effects, an advance on prior research that examined actor effects only. In addition, partner ratings of spousal behavior provided independent evidence of spousal aggressiveness that spouses may not have been willing to self-report. Fourth, whereas most prior research on marital quality relies exclusively on spouses’ self-reports, which may share method variance with their self-reports of discrimination, the results described here replicated on both self-reports and interviewer ratings of marital quality.

Notwithstanding these strengths, generalizations from these results should also be tempered by some important limitations of the current research. First, although studying first-married newlyweds helps control for cohort effects (Karney & Bradbury, 1995), the implications of discrimination and ethnic identity may vary in more established marriages. Second, all of the data examined here were assessed at a single occasion, preventing us from drawing conclusions about causal influence. For example, although it is consistent with current models of stress and relationships to suggest that the experience of discrimination affects marital outcomes, these data cannot rule out the possibility that unmeasured variables accounted for the associations among discrimination, ethnic identity, and marital satisfaction observed here. Stronger conclusions will require that the hypothesized causal paths in these models are verified with longitudinal or experimental designs. Third, our measure of perceived discrimination may not have adequately captured wives’ experience of ethnic discrimination, either because the measure did not distinguish between the experience of gender and ethnic discrimination, or because the items used in the MIDUS measure are more relevant for males than they are for females (e.g., people acting “as if they are afraid of you”). This lack of specificity in measuring wives’ experience of ethnic discrimination may have accounted for why wives’ ethnic identity did not buffer the negative association between wives’ experience of discrimination and marital quality.

To date, researchers interested in racial discrimination have largely ignored disparities in marriage—presumably because there was not an obvious mechanism by which discrimination might produce those disparities. The results described here, however, suggest that experiencing racial discrimination may affect marriages in much the same way that they influence individuals. For instance, emerging research suggests that subordinate group men experience racial discrimination as a threat to their masculine self-concept (Goff, Di Leone, & Kahn, under review). This masculinity threat can provoke compensatory aggression towards the threatening target (Bosson, Prewitt-Freilino, & Taylor, 2005; Goff, et al., under review; Vandello, Bosson, Cohen, Burnaford, & Weaver, 2008). This literature is informed by research on Social Dominance that suggests that racial conflict occurs most frequently and intensely between men of different races and that the need to establish status in response to racial conflict would be most acute among subordinate group men (Sidanius & Pratto, 1999). This may also account for the gender differences that emerged from our analysis. Specifically, husbands may have responded to discrimination by externalizing the threat to their masculinity through verbal aggression toward their wives. Wives, on the other hand, may have internalized and externalized these experiences of disrespect in equal measure.

While it would be premature to suggest that the current data provide support for this hypothesis in the context of marriages, they are certainly consistent with this growing literature and provide fruitful territory for future exploration. More importantly, if Social Dominance research can be applied to marriages, it is possible that other contemporary approaches to discrimination (and its costs) may also be relevant to the domain of close relationships. This suggests not only an important new domain in which to apply theoretical approaches to racial bias, but a vital opportunity to create a fuller picture of how race shapes our social lives. For example, important racial disparities exist in marital outcomes such as divorce (Bramlett & Mosher, 2002; Raley & Bumpass, 2003), and in marital processes such as intimate partner violence (Caetano, et al., 2000). These disparities can have implications that stretch beyond the couple. For example, children of divorced couples are more likely to have behavioral problems, low self-esteem, and academic difficulties (Amato & Keith, 1991), and they are more likely to divorce as adults (Glenn & Kramer, 1987) than are children of intact families. Women who are divorced have more financial problems (Smock, Manning, & Gupta, 1999), and their children are more likely to enter adulthood with fewer financial resources (McLanahan & Sandefur, 1994). Even if their parents do not divorce, children exposed to parental conflict are more likely to have low self-esteem, exhibit behavioral problems, and have difficulties in school (Amato & Booth, 1997; Rossman, Hughes, & Rosenberg, 2000). The consequences of marital disruption can even spread to affect the grandchildren of the divorced couple (Amato & Cheadle, 2005). Thus, if experiencing discrimination plays a detrimental role in marital outcomes and marital relations, then its effects could spread to affect not only the couple, but also set the stage for negative outcomes for future generations.

The negative consequences of discrimination are not inevitable, however. These results demonstrate that ethnic identity can serve as a source of strength for husbands, buffering the negative association between experiencing discrimination and marital quality. Although the exact nature of this buffering process still needs to be explored, the literature on discrimination suggests some possibilities. For example, when confronted with ethnic discrimination, highly identified individuals seek out social support from friends and others in their community (Crocker & Major, 1989). In addition, living in a predominately same-race neighborhood may offer additional opportunities for social support and connection to one’s ethnic group, which could then buffer couples from the impact of discrimination (Postmes & Branscombe, 2002). For Latinos, the experience of discrimination has been linked to the challenges of acculturation. Immigrants in particular have to negotiate their newfound identity in their host country with the identity associated with their country of origin (Deaux, 2000, 2006; Tormala & Deaux, 2006). As immigrants become acculturated to the US, they are more likely to report being the target of ethnic discrimination (Finch, Kolody, & Vega, 2000; Pérez, et al., 2008), and they experience higher divorce rates as well (Padilla & Borrero, 2006). Therefore, for Latino couples, balancing the pressures for acculturation with maintaining their cultural identity may play a key role in helping cope with discrimination and its effects on their relationships.

In conclusion, the current research demonstrated that the experience of discrimination has implications for peoples’ lives that go far beyond the specific context in which the discrimination was experienced. These results add to the literature on the negative correlates of the experience of ethnic discrimination and well-being, and it provides further evidence of the buffering effect that ethnic identity can play in this relationship. Given the current findings that husbands’ ethnic identity can buffer the negative relationship between discrimination and marital quality, recent efforts to deemphasize ethnic studies in schools (Lewin, May 14, 2010) may prove counterproductive. On the contrary, a direction for future research is to test whether programs that directly address and enhance ethnic identity might also increase the quality and stability of minority marriages, as well as ameliorate many of the other negative effects of discrimination for minority populations.

References

- Amato PR, & Booth A (1997). A generation at risk: Growing up in an era of family upheaval. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Amato PR, & Cheadle J (2005). The long reach of divorce: Divorce and child well-being across three generations. Journal of Marriage and Family, 67, 191–206. [Google Scholar]

- Amato PR, & Keith B (1991). Parental divorce and the well-being of children: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 110, 26–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, & Kenny DA (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1173–1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger N, Foster M, Vinokur AD, & Ng R (1996). Close relationships and adjustment to a life crisis: The case of breast cancer. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70, 283–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosson JK, Prewitt-Freilino JL, & Taylor JN (2005). Role rigidity: A problem of identity misclassification? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 89, 552–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen WG, & Bok DC (1998). The shape of the river: Long-term consequences of considering race in college and university admissions. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bramlett MD, & Mosher WD (2002). Cohabitation, marriage, divorce, and remarriage in the United States. National Center for Health Statistics. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/series/sr_23/sr23_022.pdf [PubMed]

- Broudy R, Brondolo E, Coakley V, Brady N, Cassells A, Tobin JN, & Sweeney M (2007). Perceived ethnic discrimination in relation to daily moods and negative social interactions. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 30, 31–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budrys G (2003). Unequal health: How inequality contributes to health or illness. New York: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R, Cunradi CB, Schafer J, & Clark CL (2000). Intimate partner violence and drinking patterns among White, Black, and Hispanic couples in the US. Journal of Substance Abuse, 11, 123–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell CH, Kohn-Wood LP, Schmeelk-Cone KH, Chavous TM, & Zimmerman MA (2004). Racial discrimination and racial identity as risk or protective factors for violent behaviors in African American young adults. American Journal of Community Psychology, 33, 91–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cano A, & Vivian D (2003). Are life stressors associated with marital violence? Journal of Family Psychology, 17, 302–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Census Bureau US (2009). Annual estimates of the resident population by sex, race, and Hispanic origin for the United States: April 1, 2000 to July 1, 2008 (NC-EST2008-03). Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/popest/national/asrh/.

- Cervantes RC, Padilla AM, & de Snyder NS (1991). The Hispanic Stress Inventory: A culturally relevant approach to psychosocial assessment. Psychological Assessment, 3, 438–447. [Google Scholar]

- Chatman CM, Eccles JS, & Malanchuk O (2005). Identity negotiation in everyday settings In Downey G, Eccles JS & Chatman CM (Eds.), Navigating the future: Social identity, coping, and life tasks (pp. 116–140). New York: Russel Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Clark R, Anderson NB, Clark VR, & Williams DR (1999). Racism as a stressor for African Americans: A biopsychosocial model. The American Psychologist, 54, 805–816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Elder GH Jr, Lorenz FO, Conger KJ, Simons RL, Whitbeck LB, . . . Melby JN (1990). Linking economic hardship to marital quality and instability. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 52, 643–656. [Google Scholar]

- Cook JE, Arrow H, & Malle BF (2011). The effect of feeling stereotyped on social power and inhibition. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 37, 165–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crocker J, & Major B (1989). Social stigma and self-esteem: The self-protective properties of stigma. Psychological Review, 96, 608–630. [Google Scholar]

- Cutrona CE, Russell DW, Abraham WT, Gardner KA, Melby JN, Bryant C, & Conger RD (2003). Neighborhood context and financial strain as predictors of marital interaction and marital quality in African American couples. Personal Relationships, 10, 389–409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deaux K (2000). Surveying the landscape of immigration: Social psychological perspectives. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 10, 421–431. [Google Scholar]

- Deaux K (2006). To be an immigrant. New York: Russel Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- DeFreitas G (1991). Inequality at work: Hispanics in the US labor force. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dovidio JF, & Esses VM (2001). Immigrants and immigration: Advancing the psychological perspective. Journal of Social Issues, 57, 378–387. [Google Scholar]

- Dovidio JF, Gluszek A, John MS, Ditlmann R, & Lagunes P (2010). Understanding bias toward Latinos: Discrimination, dimensions of difference, and experience of exclusion. Journal of Social Issues, 66, 59–78. [Google Scholar]

- Finch BK, Kolody B, & Vega WA (2000). Perceived discrimination and depression among Mexican-origin adults in California. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 41, 295–313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisbie WP (1986). Variation in patterns of marital instability among Hispanics. Journal of Marriage and Family, 48, 99–106. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons FX, Etcheverry PE, Stock ML, Gerrard M, Weng CY, Kiviniemi M, & O’Hara RE (2010). Exploring the link between racial discrimination and substance use: What mediates? What buffers? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95, 785–801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons FX, Gerrard M, Cleveland MJ, Wills TA, & Brody G (2004). Perceived discrimination and substance use in African American parents and their children: A panel study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 86, 517–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glenn ND, & Kramer KB (1987). The marriages and divorces of the children of divorce. Journal of Marriage and Family, 49, 811–825. [Google Scholar]

- Goff PA (in press). A measure of justice: What policing racial bias research reveals In Harris FC & Lieberman RC (Eds.), Beyond discrimination: Racial inequality in a post-racial era? New York: Russel Sage Press. [Google Scholar]

- Goff PA, Di Leone B, & Kahn KB (under review). Racism leads to pushups: How racial discrimination threatens subordinate men’s masculinity. [Google Scholar]

- Goff PA, & Kahn KB (under review). Racial bias in policing: Why we know less than we should. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen N, & Sassenberg K (2006). Does social identification harm or serve as a buffer? The impact of social identification on anger after experiencing social discrimination. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 32, 983–996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao L (2007). Color lines, country lines: Race, immigration, and wealth stratification in America. New York: Russel Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Hellmuth JC, & McNulty JK (2008). Neuroticism, marital violence, and the moderating role of stress and behavioral skills. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95, 166–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill R (1949). Families under stress. New York: Harper & Row. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson JS, Brown TB, Williams DR, Torres M, Sellers SL, & Brown KB (1996). Racism and the physical and mental health status of African Americans: A 13-year national panel study. Ethnicity and Disease, 6, 132–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jargowsky PA (1997). Poverty and place: Ghettos, barrios, and the American city. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Karney BR, & Bradbury TN (1995). The longitudinal course of marital quality and stability: A review of theory, method, and research. Psychological Bulletin, 118, 3–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA, Kashy DA, & Cook WL (2006). Dyadic data analysis. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Mickelson KD, & Williams DR (1999). The prevalence, distribution, and mental health correlates of perceived discrimination in the United States. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 40, 208–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreider RM, & Simmons T (2003). Special report on marital status: 2000. US Census Bureau. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/prod/2003pubs/c2kbr-30.pdf

- Levin S, Sinclair S, Veniegas RC, & Taylor PL (2002). Perceived discrimination in the context of multiple group memberships. Psychological Science, 13, 557–560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewin T (May 14, 2010). Citing individualism, Arizona tries to rein in ethnic studies in school, The New York Times, p. A13. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln KD, & Chae DH (2010). Stress, marital satisfaction, and psychological distress among African Americans. Journal of Family Issues, 31, 1081–1105. [Google Scholar]

- Massey DS, Charles CZ, Lundy GF, & Fischer MJ (2003). The source of the river: The social origins of freshmen at America’s selective colleges and universities. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Massey DS, & Denton NA (1993). American apartheid: Segregation and the making of the underclass. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mays VM, Cochran SD, & Barnes NW (2007). Race, race-based discrimination, and health outcomes among African Americans. Annual Review of Psychology, 58, 201–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLanahan S, & Sandefur G (1994). Growing up with a single parent: What hurts, what helps? Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Murry VMB, Brown PA, Brody GH, Cutrona CE, & Simons RL (2001). Racial discrimination as a moderator of the links among stress, maternal psychological functioning, and family relationships. Journal of Marriage and Family, 63, 915–926. [Google Scholar]

- Neblett EW, Shelton JN, & Sellers RM (2004). The role of racial identity in managing daily racial hassles In Philogene G (Ed.), Race and identity: The legacy of Kenneth Clark (pp. 77–90). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association Press. [Google Scholar]

- Neff LA, & Karney BR (2004). How does context affect intimate relationships? Linking external stress and cognitive processes within marriage. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 30, 134–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver ML, & Shapiro TM (2006). Black wealth/White wealth: A new perspective on racial inequality (10th anniversary ed.). New York: Routledge, Taylor, and Francis Group. [Google Scholar]

- Oropesa RS, & Landale NS (2004). The future of marriage and Hispanics. Journal of Marriage and Family, 66, 901–920. [Google Scholar]

- Padilla AM, & Borrero NE (2006). The effects of acculturative stress on the Hispanic family In Wong PTP & Wong LCJ (Eds.), Handbook of multicultural perspectives on stress and coping (pp. 299–317). New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez DJ, Fortuna L, & Alegría M (2008). Prevalence and correlates of everyday discrimination among U.S. Latinos. Journal of Community Psychology, 36, 421–433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Postmes T, & Branscombe NR (2002). Influence of long-term racial environmental composition on subjective well-being in African Americans. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83, 735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raley RK, & Bumpass L (2003). The topography of the divorce plateau: Levels and trends in union stability in the United States after 1980. Demographic Research, 8, 245–260. [Google Scholar]

- Richman LS, Bennett GG, Pek J, Siegler I, & Williams RB Jr (2007). Discrimination, dispositions, and cardiovascular responses to stress. Health Psychology, 26, 675–683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogge RD, & Bradbury TN (1999). Till violence does us part: The differing roles of communication and aggression in predicting adverse marital outcomes. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 67, 340–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossman BBR, Hughes HM, & Rosenberg MS (2000). Children and interparental violence: Impact of exposure. Philadelphia: Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartzman D (1997). Black male unemployment. The Review of Black Political Economy, 25, 77–93. [Google Scholar]

- Scott LD, & House LE (2005). Relationship of distress and perceived control to coping with perceived racial discrimination among black youth. Journal of Black Psychology, 31, 254–272. [Google Scholar]

- Sellers RM, Rowley SAJ, Chavous TM, Shelton JN, & Smith MA (1997). Multidimensional Inventory of Black Identity: A preliminary investigation of reliability and construct validity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 73, 805–815. [Google Scholar]

- Sellers RM, & Shelton JN (2003). The role of racial identity in perceived racial discrimination. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84, 1079–1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellers RM, Smith MA, Shelton JN, Rowley SAJ, & Chavous TM (1998). Multidimensional model of racial identity: A reconceptualization of African American racial identity. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 2, 18–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro TM (2004). The hidden cost of being African American: How wealth perpetuates inequality. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shelton JN, Yip T, Eccles JS, Chatman CM, Fuligni A, & Wong C (2005). Ethnic identity as a buffer of psychological adjustment to stress In Downey G, Eccles JS & Chatman CM (Eds.), Navigating the future: Social identity, coping, and life tasks (pp. 96–115). New York: Russell Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Sidanius J, & Pratto F (1999). Social dominance: A theory of oppression and dominance. New York: Cambridge. [Google Scholar]

- Simms M, Fortuny K, & Henderson E (2009). Racial and ethnic disparities among low-income families. Urban Institute; Retrieved from http://www.urban.org/url.cfm?ID=411936 [Google Scholar]

- Smock PJ, Manning WD, & Gupta S (1999). The effect of marriage and divorce on women’s economic well-being. American Sociological Review, 64, 794–812. [Google Scholar]

- Steele CM (2010). Whistling Vivaldi: And other clues to how stereotypes affect us. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. [Google Scholar]

- Straus M (1979). Measuring intrafamily conflict and aggression: The Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS). Journal of Marriage and the Family, 41, 75–88. [Google Scholar]

- Tormala TT, & Deaux K (2006). Black immigrants to the United States: Confronting and constructing ethnicity and race In Mahalingham R (Ed.), Cultural psychology of immigrants (pp. 131–150). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Vandello JA, Bosson JK, Cohen D, Burnaford RM, & Weaver JR (2008). Precarious manhood. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95, 1325–1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, & Neighbors HW (2001). Racism, discrimination and hypertension: Evidence and needed research. Ethnicity & disease, 11, 800–816. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Yu Y, Jackson JS, & Anderson NB (1997). Racial differences in physical and mental health. Journal of Health Psychology, 3, 335–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson WJ (1996). When work disappears. Political Science Quarterly, 111, 567–595. [Google Scholar]