Abstract

Objectives

To describe a well-established marker of cardiovascular risk, carotid intima–media thickness (IMT) and related measures (artery distensibility and elasticity) in children aged 11–12 years old and mid-life adults, and examine associations within parent–child dyads.

Design

Cross-sectional study (Child Health CheckPoint), nested within a prospective cohort study, the Longitudinal Study of Australian Children (LSAC).

Setting

Assessment centres in seven Australian major cities and eight selected regional towns, February 2015 to March 2016.

Participants

Of all participating CheckPoint families (n=1874), 1489 children (50.0% girls) and 1476 parents (86.8% mothers) with carotid IMT data were included. Survey weights and methods were applied to account for LSAC’s complex sample design and clustering within postcodes and strata.

Outcome measures

Ultrasound of the right carotid artery was performed using standardised protocols. Primary outcomes were mean and maximum far-wall carotid IMT, quantified using semiautomated edge detection software. Secondary outcomes were carotid artery distensibility and elasticity. Pearson’s correlation coefficients and multivariable linear regression models were used to assess parent–child concordance. Random effects modelling on a subset of ultrasounds (with repeated measurements) was used to assess reliability of the child carotid IMT measure.

Results

The average mean and maximum child carotid IMT were 0.50 mm (SD 0.06) and 0.58 mm (SD 0.05), respectively. In adults, average mean and maximum carotid IMT were 0.57 mm (SD 0.07) and 0.66 mm (SD 0.10), respectively. Mother–child correlations for mean and maximum carotid IMT were 0.12 (95% CI 0.05 to 0.23) and 0.10 (95% CI 0.03 to 0.21), respectively. For carotid artery distensibility and elasticity, mother–child correlations were 0.19 (95% CI 0.10 to 0.25) and 0.11 (95% CI 0.02 to 0.18), respectively. There was no strong evidence of father–child correlation in any measure.

Conclusions

We provide Australian values for carotid vascular measures and report a modest mother–child concordance. Both genetic and environmental exposures are likely to contribute to carotid IMT.

Keywords: intima-media thickness, distensibility, reference values, children, inheritance patterns, epidemiological studies

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the largest cross-sectional study to investigate carotid intima–media thickness (IMT) concordance in parent–child dyads.

Population-based sampling of children provides an additional Australian reference for future studies investigating carotid IMT.

Our study sample contained a large proportion of mothers, limiting generalisability of our concordance findings for fathers.

Introduction

Atherosclerosis has a long preclinical latency that begins in early life; this affords multiple opportunities for early prevention and intervention.1 2 Traditional cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factors are predictive of outcomes in adults, but do not capture the total risk.3 Widely used CVD screening tools for adults (such as the Framingham Risk Score) predict only 60%–65% of CVD risk,3 and CVD events increasingly occur in many who have no traditional risk factors.4 Non-invasive risk assessment, such as carotid intima–media thickness (IMT), may facilitate earlier intervention5 by improving CVD risk prediction and stratification for intermediate-risk individuals.3

Carotid IMT is a non-invasive ultrasound technique that measures the thickness of the intimal and medial layers of the carotid artery. It is a marker of early subclinical total atherosclerotic burden.6–11 Pignoli et al 12 first demonstrated B-mode ultrasound-assisted measurement of the intima and media layers of the carotid artery, in vivo at the time of autopsy, reflecting the direct measurement of atherosclerotic burden at that site. The extent of coronary artery atherosclerosis also correlate with carotid IMT in large clinical populations of high-risk individuals.13 14 Carotid IMT reflects the burden of multiple cardiovascular risk factors,15 predicts future cardiovascular events (including stroke and myocardial infarction)016–18 and has the potential to be used as a CVD screening tool in addition to existing risk scores.3 19

Functional artery measurements may also provide a sensitive marker of CVD risk. In adults, decreased arterial distensibility and elasticity have been observed in hypertensive patients20 and those with diabetes,21 but their use in stroke and myocardial infarction are of uncertain value.

Few studies have examined the distribution of carotid IMT and related vascular measures, such as arterial distensibility and elasticity, in children. One of the largest studies to date22 assessed 1155 children aged between 6 and 18 years and developed sex-specific reference charts normalised to age and height. Given the lack of outcome data linking childhood artery parameters with adult CVD, the meaning of these reference values remains uncertain. Nonetheless, functional and structural measures of vascular health as predictors of CVD may be particularly important for children because of the greater potential for reducing atherosclerosis through modifying CVD risk factors early in life.23–25

The relative contribution of shared and unshared factors to carotid artery parameters has important implications for the design of interventions to modify CVD risk. Parent–child concordance is a unique opportunity to add additional important information in the calculation of these relative contributions, leveraging the unique genetic and environmental exposures parents and their children share. Carotid IMT is known to be modestly heritable, however, the estimates are largely derived from studies of twins26 or older participants.27 28 One study reported modest parent–child heritability (h2 <30%).29 Understanding parent–child concordance in a larger population-based cohort could clarify sex differences and examine the generalisability of earlier findings.

The Child Health CheckPoint nested within Growing Up in Australia (also known as the Longitudinal Study of Australian Children, LSAC) offers a unique opportunity to report cross-sectional carotid artery phenotypes in Australian parent–child dyads measured on the same day using the same protocols. We aimed to (1) describe, in Australian children aged 11–12 years old and their parents, the distribution of carotid IMT and related measures (artery distensibility and elasticity) and (2) to analyse parent–child concordance. In addition, we use repeated readings on a subset of child films by both the same and a different rater to estimate the magnitude of measurement error in carotid IMT readings.

Methods

Study design and participants

Details of the initial study design and recruitment are outlined elsewhere.30 31 Briefly, LSAC recruited a nationally representative B cohort of 5107 infants using a two-stage random sampling design with the postal code as primary sampling unit, and followed them up in biennial ‘waves’ of data collection up to 2015. The initial recruitment rate in 2004 was 57.2%, of whom 73.7% (n=3764) were retained to LSAC wave 6 in 2014.

At the wave 6 visit, all families were invited to consent to their contact details being shared with the Child Health CheckPoint team (n=3513). In 2015, families who consented were then sent an information pack via post and received an information and recruitment phone call. The CheckPoint’s detailed cross-sectional biophysical assessment (the Child Health CheckPoint), nested between LSAC waves 6 and 7 (aged 11–12 years), took place between February 2015 and March 2016 (see detailed description of CheckPoint methods32 33). A total of 1874 families participated.

Consent

The attending parents/caregivers provided written informed consent for themselves and their children to participate in the study.

Procedure

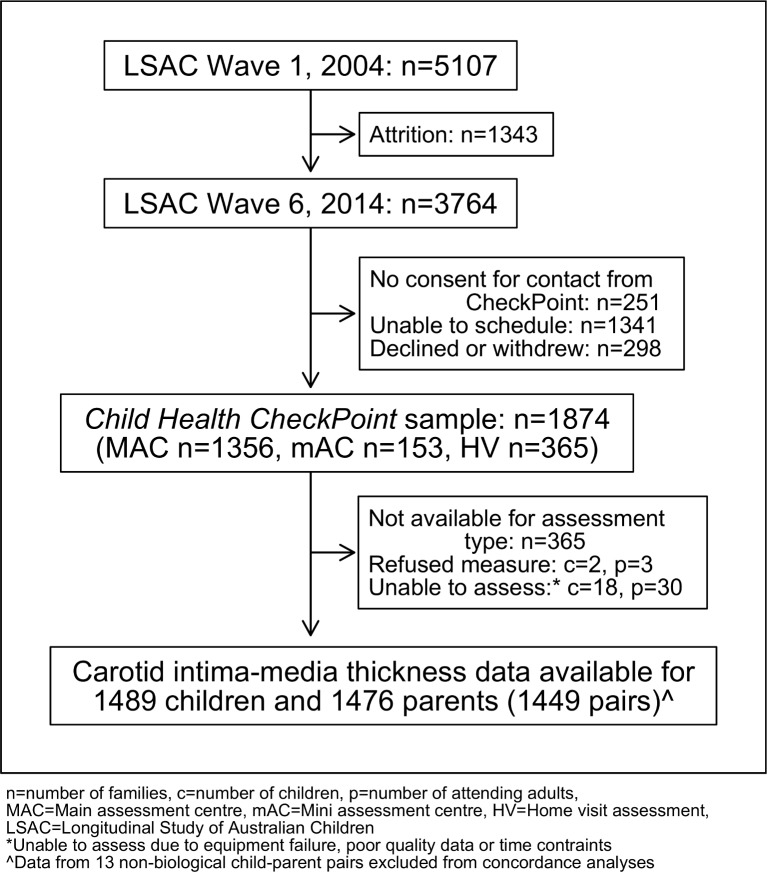

Common carotid artery IMT, lumen diameter (LD), height, weight and puberty status were collected at a specialised 3.5 hours (major cities) or 2.5 hours (smaller regional centres) CheckPoint assessment centre visit. Three hundred and sixty five families who could not arrange a centre visit completed a home visit with a reduced protocol excluding carotid ultrasound; their data were not included (figure 1). Participating families were included in the current analyses if carotid artery data from CheckPoint were available (figure 1). Parents were excluded from correlation analyses if they were non-biological caregivers.

Figure 1.

Participant flow chart. n, number of families; c, number of children; p, number of attending adults; MAC, main assessment centre; mAC, mini assessment centre; HV, home visit assessment; LSAC, Longitudinal Study of Australian Children. *Unable to assess due to equipment failure, poor quality data or time contraints. ∧Data from 13 non-biological child-parent pairs excluded from concordance analyses.

Participants underwent carotid ultrasound, vascular stiffness assessment and blood pressure measurement in a specialised 15 min station (called ‘Heart Lab’), which was within the first hour of arrival at the assessment centre visit. Participants were semifasted and ultrasound assessment was performed prior to exercise testing and salbutamol administration (part of the respiratory function assessment).

Carotid artery ultrasound

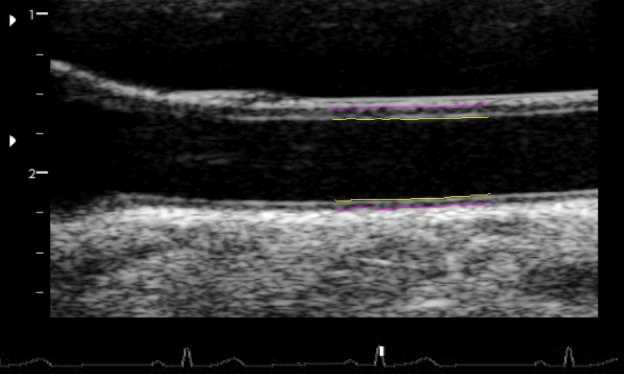

Carotid artery images were acquired using standardised protocols developed in accordance with recommendations of the American Society of Echocardiography and Mannheim Consensus statements.18 34 All participants lay supine with their head turned 45° to the left to expose the right side of neck. The right carotid artery was chosen to harmonise with other vascular measures taken in Heart Lab, such as pulse wave velocity, which also assessed the right-sided circulation. Ultrasound images were obtained using a portable ultrasound machine and 10 MHz linear array probe (Vivid-I, GE Healthcare, Chicago, Illinois, USA). Image acquisition occurred in two distinct phases. First, to confirm imaging location, technicians visualised a cross-section of arterial lumens both above and below the carotid bifurcation. Subsequent rotation of the probe, in the second phase of acquisition, allowed technicians to acquire a longitudinal image of the common carotid artery and proximal section of the carotid bulb. The carotid bulb was identifiable by its characteristic anatomical structure, close to the bifurcation (figure 2). The angle of imaging was chosen, in the absence of a Meijer Carotid Arc, at approximately 45° to the midline. Images were generally acquired at an angle such that the overlying internal jugular vein lay between the artery and the probe, producing the highest quality image. The duration of the captured real-time B-mode ultrasound cine-loops were 10 cardiac cycles. These were captured in triplicate by one of four trained technicians. We used a modified three-lead ECG to record heart rhythm concurrently.

Figure 2.

Sample single frame of ultrasound obtained in CheckPoint, with Carotid Analyzer analysis overlayed. Yellow lines indicate the lumen–intima interface, pink lines indicate the media–adventitia interface. The distance between yellow and pink lines in the lower pair of lines (far wall) is the carotid intima–media thickness. The carotid bulb characteristics are demonstrated in the left edge of the image.

Image processing and quality

All images were reviewed by one technician to select loops that met key optimisation parameters: a clear near and far wall intima–media, clear lumen, straight vessel, presence of the carotid bulb and an ECG trace. The best quality 5–7 cardiac cycle sections of the loops were trimmed and extracted. Quality of the trimmed images was graded for wall clarity; length of clarity; position of clarity relative to carotid bulb; clear lumen and straightness of vessel, on a subjective 1–4 scale.

Mean and maximum carotid IMT

These loops were further processed using Carotid Analyzer (Medical Imaging Applications, Coralville, Iowa, USA), a commercially available semiautomatic edge detection software program.35 36 Raters calibrated the images using ultrasound image markers. IMT was measured—at the vessel region of the highest quality, approximately 10 mm from the carotid bulb—using the software’s semiautomated measurement protocol. After algorithmic detection of the intima–media interface over the entire cine-loop, frames were manually adjusted as needed or rejected if the intima–media interface was unclear or blurred.

Three to five frames, at end-diastole (R wave on the ECG) from the entire cine-loop of images, were selected for analysis. Carotid IMT values were presented as the mean of 3–5 still frames of IMT. We presented both ‘mean’ carotid IMT measurements, which referred to the 3–5 frame average of the average carotid IMT over the 5–10 mm section, as well as ‘maximum’ carotid IMT, which refer to the 3–5 frame average of the thickest point of carotid IMT measurement over the 5–10 mm section.

Vessel and lumen diameter

Minimal vessel diameter (VD) at end diastole was calculated as the average media–media distance on each of the 3–5 still frames used to calculate mean and maximum carotid IMT. LD was calculated by measuring the average intima–intima distance (subtracting near and far wall IMT measurements).

Reliability of child carotid IMT readings

Six trained raters analysed all cine-loops. Training consisted of 30 example cine-loops that were subsequently assessed for consistency by an expert rater (RL). Inter-rater and intrarater reliability was assessed by reanalysing a subset of 105 randomly selected images four times at the end of the scoring process. Images were reassessed twice each by two raters in a balanced incomplete block design as not all raters assessed the complete subset. This allowed estimation of the repeatability of measurements made by the same rater and the reproducibility of measurements made by different raters. Image acquisition was only performed once.

Other carotid arterial measures

Further measures of carotid artery distensibility and elasticity were calculated from carotid artery images as follows:

Carotid arterial distensibility (%) was calculated as previously described,37 automatically from Carotid Analyzer, based on maximum and minimum media–media frame pairs in the cine-loop:

Carotid arterial elasticity (%/mm Hg) was derived using intima–intima LD, according to previously published work from the Cardiovascular Risk in Young Finns Study38 39 and other related studies37:

Measurements of VD and LD were automated and rater independent.

Other sample characteristics

Measurement of other sample characteristics is outlined in detail elsewhere.32 Briefly, age was calculated to nearest week using date of birth, either imported from the Medicare Australia enrolment database (child) or self-reported (parent) and date of assessment. Child sex was exported from the Medicare Australia enrolment database. Pubertal stage was self-reported and further categorised using the Pubertal Development Scale.40 We considered any child who was in the early pubertal category or above as having started puberty. Adult sex was self-reported.

Anthropomorphic measurements were taken as previously described.32Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight (kg) divided by height (m) squared. For children, an age-adjusted and sex-adjusted BMI z-score was calculated using the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention growth reference charts.41 Blood pressure was measured via SphygmoCor XCEL (AtCor Medical, West Ryde, NSW, Australia). Following 7 min in supine position at rest, systolic and diastolic blood pressures were measured at the brachial artery up to three times, with mean values reported.

Socioeconomic Indexes for Areas scores of the postal code region where the participating family lived were used as a measure of neighbourhood socioeconomic position. The Index of Relative Socioeconomic Disadvantage (Disadvantage Index) was a standardised score by geographical area compiled from 2011 Australian Census data, to numerically summarise the social and economic conditions of Australian neighbourhoods (national mean of 1000 and an SD of 100, where higher values represent less disadvantage).42

Diabetes requiring medical treatment, high cholesterol requiring medical treatment, heart conditions, pre-existing hypertension and the presence of a pacemaker were self-reported by parents in a questionnaire at the assessment centre. Parental and home smoking behaviour was asked at each LSAC wave. Parents reported children’s exposure to secondhand smoke as follows: ‘Including yourself, how many people who live with you smoke inside the house?’. If parents’ ever answered one person or more, children were considered exposed. Parents were classified as ever smokers if they ever answered yes to the question ‘Have you ever smoked?’ or ‘Are you currently smoking?’. Parents were classified as current smoker if yes was the most recent answer to ‘Are you currently smoking?’.

Statistical analysis

Concordance between parents and children was assessed by: (1) Pearson’s correlation coefficients with 95% CIs and (2) linear regression with child variable as dependent variable and parent variable as independent variable.

Population summary statistics and proportions were estimated by applying survey weights and survey procedures that corrected for sampling, participation and non-response biases, and took into account clustering in the sampling frame. SEs were calculated taking into account the complex design and weights.43 More detail on the calculation of weights is provided elsewhere.44

Linear regression models were adjusted for parent and child age, parent and child height, child LD, Disadvantage Index, and parent and child sex, in models including both sexes. In addition, the Pearson’s correlation coefficient and linear regression analyses were repeated using weighted multi level survey analyses, and became the main reported analyses.

In our reliability analysis, we modelled repeated measurements on child carotid IMT films with random effects for rater and child to estimate between-child variance, between-rater variance and residual error variance. These variance components were used to calculate within-rater and between-raters intraclass correlations (the ratio of explained variability to the total model variability), and within-rater and between-rater coefficients of variation (the SD of measurement error divided by the mean).

Stata V.14.2 (StataCorp) was used in all analyses.

Patient and public involvement

Because LSAC is a population-based longitudinal study, no patient groups were involved in its design or conduct. To our knowledge, the public was not involved in the study design, recruitment or conduct of the LSAC study or its CheckPoint module. Parents received a summary health report for their child and themselves at or soon after the assessment visit. They consented to take part knowing that they would not otherwise receive individual results about themselves or their child.

Results

Sample characteristics

The recruitment and retention of participants in the Child Health CheckPoint are described in detail elsewhere.32 Of the 1874 families who participated in CheckPoint assessment centres, we obtained carotid ultrasound images of analysable quality from 1489 children and 1476 parents (figure 1). The majority of excluded families undertook home visits, where carotid IMT could not be performed (n=365, 19.5%). Few data were lost due to poor quality images or inability to measure at the assessment centre (figure 1).

The sample characteristics of parents and children are outlined in table 1, stratified by sex.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics, stratified by sex, of children and parents

| Child | All | Boys | Girls | ||||||

| Characteristics | N | Mean* | SD* | N | Mean* | SD* | N | Mean* | SD* |

| Age, years | 1489 | 12.0 | 0.4 | 745 | 12.0 | 0.4 | 744 | 12.0 | 0.4 |

| Height, cm | 1488 | 153.2 | 7.9 | 744 | 152.5 | 8.0 | 744 | 153.9 | 7.8 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 1488 | 19.4 | 3.6 | 744 | 19.3 | 3.5 | 744 | 19.6 | 3.6 |

| BMI z-score (CDC) | 1488 | 0.37 | 1.02 | 744 | 0.37 | 1.02 | 744 | 0.37 | 1.01 |

| Waist, cm | 1488 | 66.6 | 8.7 | 744 | 67.3 | 8.8 | 744 | 65.8 | 8.5 |

| SBP, mm Hg | 1371 | 108.6 | 8.0 | 673 | 108.4 | 7.8 | 698 | 108.9 | 8.2 |

| DBP, mm Hg | 1371 | 63.1 | 5.6 | 673 | 62.7 | 5.7 | 698 | 63.5 | 5.4 |

| Disadvantage Index | 1485 | 1010 | 63 | 742 | 1008 | 63 | 743 | 1011 | 63 |

| Lumen diameter, mm | 1419 | 4.9 | 0.4 | 708 | 5.0 | 0.4 | 711 | 4.7 | 0.4 |

| N | n | %* | N | n | %* | N | n | %* | |

| Diabetes | 1489 | 3 | 0.2 | 745 | 1 | 0.1 | 744 | 2 | 0.3 |

| Started puberty | 1374 | 1234 | 90.7 | 700 | 591 | 84.4 | 674 | 643 | 95.4 |

| Pacemaker | 1489 | 0 | 0.0 | 745 | – | – | 744 | – | – |

| Exposed to secondhand smoke | 1489 | 298 | 26.6 | 745 | 152 | 26.9 | 744 | 146 | 26.2 |

| Parent | All | Fathers | Mothers | ||||||

| Characteristics | N | Mean* | SD* | N | Mean* | SD* | N | Mean* | SD* |

| Age, years | 1476 | 43.7 | 5.5 | 195 | 46.2 | 7.0 | 1281 | 43.3 | 5.2 |

| Height, cm | 1474 | 166.1 | 7.8 | 195 | 177.8 | 7.6 | 1279 | 164.4 | 6.2 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 1472 | 28.2 | 6.2 | 195 | 29.0 | 5.0 | 1277 | 28.1 | 6.4 |

| Waist, cm | 1468 | 87.4 | 14.4 | 194 | 98.1 | 13.3 | 1274 | 85.8 | 13.8 |

| SBP, mm Hg | 1345 | 120.4 | 12.8 | 177 | 128.3 | 11.7 | 1168 | 119.2 | 12.6 |

| DBP, mm Hg | 1345 | 73.9 | 8.7 | 177 | 78.2 | 8.5 | 1168 | 73.2 | 8.5 |

| Disadvantage Index | 1472 | 1010 | 63 | 193 | 1004 | 72 | 1279 | 1011 | 62 |

| Lumen diameter, mm | 1336 | 5.3 | 0.5 | 160 | 5.9 | 0.5 | 1176 | 5.2 | 0.4 |

| N | n | %* | N | n | %* | N | n | %* | |

| Diabetes | 1476 | 31 | 2.6 | 195 | 9 | 7 | 1281 | 22 | 1.9 |

| Heart condition | 1476 | 32 | 3.2 | 195 | 8 | 5.1 | 1281 | 24 | 2.9 |

| Pre-existing hypertension | 1476 | 77 | 6.2 | 195 | 21 | 12.5 | 1281 | 56 | 5.3 |

| Pacemaker | 1476 | 2 | 0.1 | 195 | 0 | 0 | 1281 | 2 | 0.1 |

| Current smoker | 1471 | 126 | 12.9 | 192 | 15 | 12.0 | 1279 | 111 | 13.0 |

| Ever smoker | 1382 | 574 | 48.8 | 174 | 68 | 45.8 | 1208 | 506 | 49.2 |

N, number of participants in cohort with this measure (denominator).

Disadvantage Index: the Index of Relative Socioeconomic Disadvantage.

*Weighted mean, SD and percentage.

BMI, body mass index; CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

The parent sample was predominantly mothers (n=1281, 86.8%) from a relatively socioeconomically advantaged background (mean Disadvantage Index score, 1/10 of an SD above the national average). Approximately, 1 in 10 parents reported a cardiovascular-related health condition (diabetes, hypertension, heart condition, pacemaker) (table 1).

In children, there were similar proportions of each sex. Age-specific and sex-specific BMI z-scores were 0.37 SD above population reference values (table 1).

Carotid IMT

Summary statistics for child and parent carotid IMT are presented in table 2. Extended percentile values are found in online supplementary table 1.

Table 2.

Distribution of carotid intima–media thickness (IMT), distensibility and elasticity in children and parents

| Child characteristics | All | Boys | Girls | |||||||||

| N | Mean | SD | 95% CI | N | Mean | SD | 95% CI | N | Mean | SD | 95% CI | |

| Far wall mean IMT, mm | 1485 | 0.50 | 0.06 | 0.49 to 0.50 | 743 | 0.50 | 0.06 | 0.50 to 0.51 | 742 | 0.49 | 0.06 | 0.49 to 0.50 |

| Far wall maximum IMT, mm | 1485 | 0.58 | 0.05 | 0.58 to 0.59 | 743 | 0.59 | 0.05 | 0.58 to 0.59 | 742 | 0.58 | 0.05 | 0.57 to 0.58 |

| Carotid artery distensibility, % | 1419 | 17.4 | 3.2 | 17.2 to 17.6 | 708 | 17.1 | 3.0 | 16.8 to 17.3 | 711 | 17.7 | 3.3 | 17.4 to 18.0 |

| Carotid artery elasticity, %/mm Hg | 1312 | 0.48 | 0.09 | 0.47 to 0.48 | 641 | 0.47 | 0.08 | 0.46 to 0.48 | 671 | 0.49 | 0.09 | 0.48 to 0.50 |

| N | Median | IQR 25% | IQR 75% | N | Median | IQR 25% | IQR 75% | N | Median | IQR 25% | IQR 75% | |

| Far wall mean IMT, mm | 1485 | 0.52 | 0.46 | 0.54 | 743 | 0.52 | 0.47 | 0.55 | 742 | 0.51 | 0.45 | 0.54 |

| Far wall maximum IMT, mm | 1485 | 0.58 | 0.56 | 0.61 | 743 | 0.59 | 0.56 | 0.61 | 742 | 0.58 | 0.56 | 0.60 |

| Carotid artery distensibility, % | 1419 | 17.1 | 15.3 | 19.2 | 708 | 16.9 | 15.1 | 18.9 | 711 | 17.4 | 15.5 | 19.4 |

| Carotid artery elasticity, %/mm Hg | 1312 | 0.47 | 0.42 | 0.53 | 641 | 0.47 | 0.42 | 0.52 | 671 | 0.48 | 0.43 | 0.54 |

| Parent characteristics | All | Fathers | Mothers | |||||||||

| N | Mean | SD | 95% CI | N | Mean | SD | 95% CI | N | Mean | SD | 95% CI | |

| Far wall mean IMT, mm | 1468 | 0.57 | 0.07 | 0.56 to 0.57 | 195 | 0.61 | 0.11 | 0.59 to 0.63 | 1273 | 0.56 | 0.07 | 0.56 to 0.57 |

| Far wall maximum IMT, mm | 1468 | 0.66 | 0.10 | 0.66 to 0.67 | 195 | 0.73 | 0.14 | 0.71 to 0.76 | 1273 | 0.65 | 0.08 | 0.65 to 0.66 |

| Carotid artery distensibility, % | 1336 | 8.9 | 2.1 | 8.8 to 9.1 | 160 | 8.3 | 2.2 | 7.9 to 8.7 | 1176 | 9.0 | 2.1 | 8.9 to 9.2 |

| Carotid artery elasticity, %/mm Hg | 1229 | 0.25 | 0.06 | 0.24 to 0.25 | 145 | 0.21 | 0.06 | 0.20 to 0.23 | 1084 | 0.25 | 0.06 | 0.25 to 0.26 |

| N | Median | IQR 25% | IQR 75% | N | Median | IQR 25% | IQR 75% | N | Median | IQR 25% | IQR 75% | |

| Far wall mean IMT, mm | 1468 | 0.56 | 0.53 | 0.59 | 195 | 0.59 | 0.54 | 0.68 | 1273 | 0.55 | 0.53 | 0.58 |

| Far wall maximum IMT, mm | 1468 | 0.64 | 0.60 | 0.71 | 195 | 0.72 | 0.62 | 0.83 | 1273 | 0.63 | 0.59 | 0.69 |

| Carotid artery distensibility, % | 1336 | 8.7 | 7.5 | 10.3 | 160 | 8.2 | 6.9 | 9.7 | 1176 | 8.8 | 7.6 | 10.4 |

| Carotid artery elasticity, %/mm Hg | 1229 | 0.24 | 0.21 | 0.28 | 145 | 0.21 | 0.18 | 0.24 | 1084 | 0.25 | 0.21 | 0.29 |

N, number of participants in cohort with this measure.

bmjopen-2017-020264supp001.pdf (169.6KB, pdf)

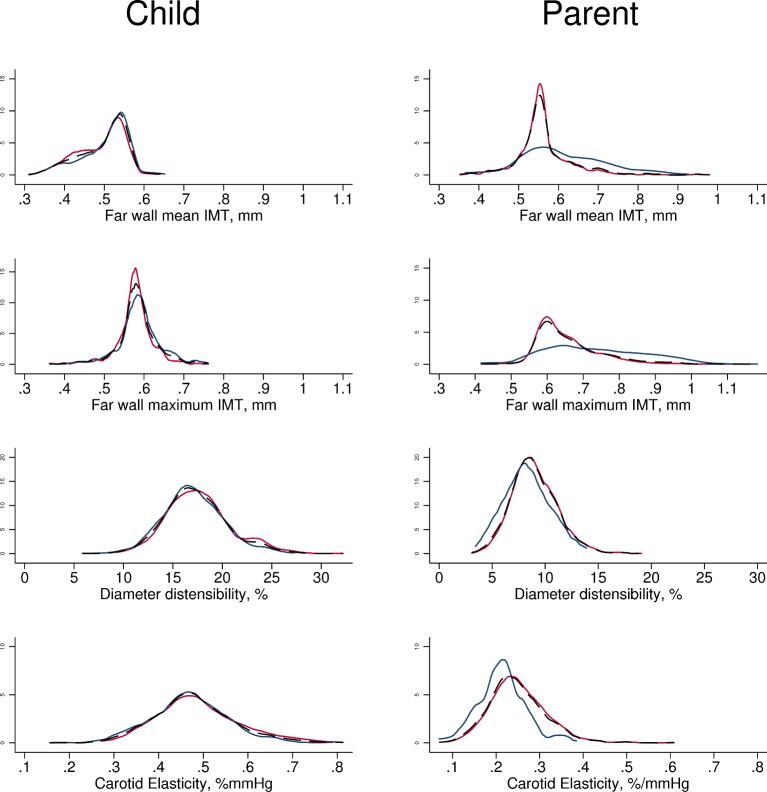

Mean and maximum carotid IMT in children approximated a normal distribution (figure 3). Boys had marginally greater average mean and maximum carotid IMT than girls (0.50 vs 0.49 mm for mean IMT). Mean carotid IMT values in children ranged from 0.31 to 0.65 mm, and maximum IMT values from 0.36 to 0.76 mm.

Figure 3.

Density plots for each primary and secondary carotid artery outcome. Males (blue), females (red) and both sexes (thin dotted black line) plotted on the same graph for each outcome. X and Y scales common between child and parent, and between mean and maximum IMT variables. IMT, intima–media thickness.

In parents, mean and maximum carotid IMT also approximated a normal distribution but with a larger positive skew. Men had substantially larger mean and maximum carotid IMT than women (0.61 vs 0.56 mm for mean IMT). Mean carotid IMT ranged from 0.35 to 0.98 mm, and maximum IMT ranged from 0.42 to 1.18 mm. Average parental carotid IMT was larger than child IMT (0.57 vs 0.50 mm for mean IMT).

Other carotid artery functional measures

Summary statistics for child and parent carotid artery distensibility and elasticity are shown in Table 2. Extended percentile values are found in online supplementary table 1. Values for both distensibility and elasticity both in children and parents approximated a normal distribution (figure 3). Boys had marginally less elastic arteries than girls, and men had substantially less elastic arteries than women (table 2). Distensibility values for children ranged from 5.8% to 32.2%, and elasticity values from 0.16% to 0.81%/mm Hg; for parents, distensibility values ranged from 3.1% to 19.1%, and elasticity values from 0.07% to 0.61%/mm Hg.

Parent–child concordance

Small, positive correlations were seen in parent–child and mother–child analyses for all measures. For example, mother–child correlations were 0.12 and 0.10 for far wall mean and maximum IMT, respectively, and 0.19 and 0.11 for carotid artery distensibility and elasticity. None of the associations attenuated in adjusted linear regression models, suggesting that parent–child concordance was independent of age, sex, height of the child and age of the parent. The small father sample size (n=195, 13.2%) made sex comparisons difficult (table 3).

Table 3.

Parent–child concordance in weighted analyses

| Pearson’s correlation | All parents | Mothers | Fathers | ||||||

| N | CC | 95% CI | N | CC | 95% CI | N | CC | 95% CI | |

| Far wall mean IMT | 1437 | 0.09 | 0.02 to 0.16 | 1245 | 0.12 | 0.05 to 0.23 | 192 | 0.01 | −0.13 to 0.14 |

| Far wall maximum IMT | 1437 | 0.08 | 0.01 to 0.15 | 1245 | 0.10 | 0.03 to 0.21 | 192 | 0.05 | −0.09 to 0.18 |

| Carotid artery distensibility | 1255 | 0.18 | 0.10 to 0.23 | 1105 | 0.19 | 0.10 to 0.25 | 150 | 0.17 | −0.05 to 0.37 |

| Carotid artery elasticity | 1133 | 0.11 | 0.03 to 0.19 | 1003 | 0.11 | 0.02 to 0.18 | 130 | 0.28 | 0.01 to 0.63 |

| Adjusted linear regression | N | ERC | P value | N | ERC | P value | N | ERC | P value |

| Far wall mean IMT, mm | 1365 | 0.08 | 0.02 | 1183 | 0.11 | 0.004 | 182 | −0.01 | 0.88 |

| Far wall maximum IMT, mm | 1365 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 1183 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 182 | 0.01 | 0.80 |

| Carotid artery distensibility, % | 1249 | 0.27 | <0.001 | 1101 | 0.29 | <0.001 | 148 | 0.08 | 0.48 |

| Carotid artery elasticity, %/mm Hg | 1127 | 0.16 | 0.002 | 999 | 0.15 | 0.004 | 128 | 0.25 | 0.13 |

Non-biological caregivers were excluded from these analyses (n=13). Covariates in adjusted linear regression models include parent and child age, parent and child height, child lumen diameter (for carotid IMT only), Disadvantage Index and child sex.

Disadvantage Index: the Index of Relative Socioeconomic Disadvantage.

N: number of participants in cohort with this measure.

CC, correlation coefficient; ERC, estimated regression coefficient; IMT, intima–media thickness.

Reliability

The within-observer coefficients of variation were 6.5% (95% CI 6.0% to 6.9%) and 4.9% (95% CI 4.6% to 5.2%) for mean and maximum carotid IMT values, respectively, and the between-observer coefficients of variation were 9.5% (95% CI 7.5% to 11.5%) and 6.2% (95% CI 5.2% to 7.2%), respectively. Within-observer intraclass correlations were 0.71 (95% CI 0.63 to 0.78) and 0.62 (95% CI 0.54 to 0.71), respectively. Between-observer intraclass correlations were 0.64 (95% CI 0.54 to 0.74) and 0.59 (95% CI 0.49 to 0.68).

Discussion

Principal findings

We provide normative carotid IMT, distensibility and elasticity values for Australian children aged 11–12 years old and their parents, together with parent–child concordance. Our results highlight that carotid IMT, distensibility and elasticity are approximately normally distributed in children, but that by middle age distributions become more skewed, potentially representing developing pathology. Mother–child concordances were modest but consistent, ranging from 0.10 to 0.19 for carotid IMT, distensibility and elasticity.

Strengths and weaknesses

This is the largest study to date to provide carotid IMT concordance data between children and their parents in a large population-based sample. Shared protocols between children and parents strengthen our conclusions about parent–child concordance. This is also the first major cohort study to identify the distribution of carotid IMT and other vascular measures in preadolescent children and mid-life parents specifically in Australia. The population-based sampling of this cohort suggests that the conclusions should generalise to the wider Australian child population. Similarities between the carotid IMT distributions in this study and those from international studies suggest our values may also be generalisable to other populations.22 45 46 Finally, raters were blinded to participants’ baseline characteristics, including age, weight, height, BMI and disadvantage score.

Potential limitations to the study include the relative mean social advantage of the participants, in keeping with attrition patterns common to many longitudinal studies. Survey weights minimise this bias, and the similarity between analyses with and without survey weights (data not shown) is reassuring. Second, relatively few fathers attended CheckPoint, which could lead to biased estimates, as the incidence of CVD and associated risk factors show strong sex differences.47 However, the reported differences between mother–child and father–child concordance in our study are minimal and have some overlap in CIs; this suggests a degree of consistency between father and mother concordance. Third, our cross-sectional data were not linked with longitudinal CVD outcomes; the relevance of carotid artery parameters in childhood is still unknown. Finally, the reliability of our carotid IMT analysis was modest, though comparable to other published results.22 The inherent underlying error in measurement may have led to underestimating true associations.48

Meaning and implications for clinicians and policy-makers

Our findings are consistent with the wider literature. In particular, our results almost exactly approximate those reported by Ryder et al of parent–offspring correlations in a US population (r=0.08 for carotid IMT, online supplementary table 2).29 Ryder’s sibling–sibling correlations were marginally higher within the same cohort (r=0.11), and were higher again, according to another study, in late middle age (r=0.36).28 This higher concordance between mid-life siblings may reflect smaller relative measurement error, because a fixed absolute measurement error becomes a smaller relative proportion of a measurement as IMT increases with age. Alternatively, it could reflect the cumulative effect of unspecified age-dependent exposures on carotid parameters. The accumulation of atheroma may have begun in childhood but is a slow, lengthy process that becomes more apparent with increasing age. Age differences could also be a significant discriminating factor that obscures true parent–child concordance if this varies across the life cycle, especially for measures that are strongly correlated with age such as IMT. Improved estimates might be achieved if parents and children were measured at the same chronological age; however, this offers little value in understanding determinants of IMT in children now.

The lack of evidence of father–child concordance for any parameter may reflect (1) a true sex difference in parent–child concordance, (2) chance and/or lack of power (with only 195 fathers in this sample) and/or (3) those fathers who attended CheckPoint not being representative of fathers of 11–12 years old children in general. Given the direction and magnitude of the point estimates, we think (2) is most likely, but this can only be verified in further studies with larger numbers of fathers. Despite their similar number of fathers (n=186), Ryder et al’s findings29 did contrast with ours in reporting a higher heritability statistic (h2=41.5%) in father–offspring dyads than mother-offspring dyads (h2=23.4%) in distensibility measures, which would also imply a higher correlation coefficient.

The relatively higher concordance in carotid artery distensibility (r=0.19) compared with other measures suggests differences between structural and functional vascular measures.23 25 Functional vascular measures such as carotid artery distensibility and elasticity are plausibly more proximal on the causal pathway than structural vascular measures such as IMT. If functional vascular changes occurred before structural changes, or if they were more sensitive to environmental exposures, concordance may be evident at an earlier age. Additionally and as above, carotid IMT may be more sensitive to measurement errors than functional measures, potentially attenuating underlying associations.

Unanswered questions and future research

These data provide a reference for future studies of LSAC participants, which would ideally map the natural history of carotid IMT from childhood onwards. The predictive value of childhood carotid IMT for future carotid IMT and future CVD is uncertain—an important scientific and clinical knowledge gap,5 given that this could inform prevention. It is possible that while the carotid IMT scores of middle-aged parents do not strongly predict the carotid IMT scores of their preadolescent children, parental values may predict the carotid IMT score of their children when they themselves reach middle age. Research effort could also be directed to finding simpler and more accurate markers of early atherosclerosis that are less prone to measurement error.

In conclusion, we provide normative data of carotid IMT and related vascular measures for Australian children aged 11–12 years old and their parents. Our demonstrated concordance—despite known measurement error and the large age difference—suggests a meaningful degree of heritability in carotid structure and function; the relative contributions of genetic and environmental underpinnings at different life stages remain to be parsed.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This paper uses unit record data from Growing Up in Australia, the Longitudinal Study of Australian Children. The study is conducted in partnership between the Department of Social Services (DSS), the Australian Institute of Family Studies (AIFS) and the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) electronic data capture tools were used in this study. More information about this software can be found at: www.project-redcap.org. The authors thank the LSAC and CheckPoint study participants, staff and students for their contributions.

Footnotes

RSL and SD contributed equally.

Contributors: RSL, SD and DPB contributed to study conception and interpretation of results, drafted the initial manuscript, critically revised further drafts and approved the final manuscript as submitted. ACG and KL contributed interpretation of results, performed the statistical analysis, drafted the initial manuscript, critically revised further drafts and approved the final manuscript as submitted. DB contributed to conception and interpretation of results of the reliability analysis, performed the statistical analysis, critically revised further drafts and approved the final manuscript as submitted. GG contributed to study conception, data collection and interpretation of results, critically revised further drafts and approved the final manuscript as submitted. JBC, MJ and MW contributed to study conception and interpretation of results, critically revised further drafts and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Funding: This work was supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) of Australia (1041352, 1109355), The Royal Children’s Hospital Foundation (2014-241), Murdoch Children’s Research Institute (MCRI), The University of Melbourne, National Heart Foundation of Australia (100660), Financial Markets Foundation for Children (2014– 055) and the Victorian Deaf Education Institute. Research at the MCRI is supported by the Victorian Government’s Operational Infrastructure Support Program. The following authors were supported by the NHMRC: Postgraduate Scholarship (1114567) to RSL, Senior Research Fellowships to MW (1046518) and DPB (1064629). RSL is supported by an Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship. MJ is supported by the Federal Research Grant of Finland to Turku University Hospital, Finnish Cardiovascular Foundation, Juho Vainio Foundation, Sigrid Juselius Foundation, Maud Kuistila Foundation, the Paulo Foundation and the MCRI (Dame Elizabeth Murdoch Fellowship). MW was supported by Cure Kids, New Zealand. DPB was supported by the National Heart Foundation of Australia Honorary Future Leader Fellowship (100369). Personalfees were received by MW from the Australian Department of Social Services (DSS). MW received grants from NZ Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment and A Better Start/Cure Kids NZ. The MCRI administered the research grants for the study and provided infrastructural support (IT and biospecimen management) to its staff and the study, but played no role in the conduct or analysis of the trial. DSS played a role in study design; however, no other funding bodies had a role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Disclaimer: The findings and views reported in this paper are those of the author and should not be attributed to DSS, AIFS or the ABS.

Competing interests: MW received support from Sandoz to present at a symposium outside the submitted work.

Ethics approval: The CheckPoint data collection protocol was approved by the Royal Children’s Hospital (Melbourne, Australia) Human Research Ethics Committee (33225D) and the Australian Institute of Family Studies Ethics Committee (14–26).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children datasets and technical documents are available to researchers at no cost via a licence agreement. Data access requests are co-ordinated by the National Centre for Longitudinal Data. More information is available at https://dataverse.ada.edu.au/dataverse/lsac.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Beaglehole R, Magnus P. The search for new risk factors for coronary heart disease: occupational therapy for epidemiologists? Int J Epidemiol 2002;31:1117–22. 10.1093/ije/31.6.1117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Naghavi M, Wang HD, Lozano R, et al. . Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 2015;385:117–71. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Baldassarre D, Amato M, Pustina L, et al. . Measurement of carotid artery intima-media thickness in dyslipidemic patients increases the power of traditional risk factors to predict cardiovascular events. Atherosclerosis 2007;191:403–8. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2006.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Vernon ST, Coffey S, Bhindi R, et al. . Increasing proportion of ST elevation myocardial infarction patients with coronary atherosclerosis poorly explained by standard modifiable risk factors. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2017;24:1824–30. 10.1177/2047487317720287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Urbina EM, Williams RV, Alpert BS, et al. . Noninvasive assessment of subclinical atherosclerosis in children and adolescents: recommendations for standard assessment for clinical research: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Hypertension 2009;54:919–50. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.192639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chambless LE, Folsom AR, Clegg LX, et al. . Carotid wall thickness is predictive of incident clinical stroke: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. Am J Epidemiol 2000;151:478–87. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a010233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lorenz MW, von Kegler S, Steinmetz H, et al. . Carotid intima-media thickening indicates a higher vascular risk across a wide age range: prospective data from the Carotid Atherosclerosis Progression Study (CAPS). Stroke 2006;37:87–92. 10.1161/01.STR.0000196964.24024.ea [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. O’Leary DH, Polak JF, Kronmal RA, et al. . Carotid-artery intima and media thickness as a risk factor for myocardial infarction and stroke in older adults. Cardiovascular Health Study Collaborative Research Group. N Engl J Med 1999;340:14–22. 10.1056/NEJM199901073400103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Salonen JT, Salonen R. Ultrasound B-mode imaging in observational studies of atherosclerotic progression. Circulation 1993;87(3 Suppl):II56–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. van der Meer IM, Bots ML, Hofman A, et al. . Predictive value of noninvasive measures of atherosclerosis for incident myocardial infarction: the Rotterdam Study. Circulation 2004;109:1089–94. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000120708.59903.1B [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rosvall M, Janzon L, Berglund G, et al. . Incident coronary events and case fatality in relation to common carotid intima-media thickness. J Intern Med 2005;257:430–7. 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2005.01485.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pignoli P, Tremoli E, Poli A, et al. . Intimal plus medial thickness of the arterial wall: a direct measurement with ultrasound imaging. Circulation 1986;74:1399–406. 10.1161/01.CIR.74.6.1399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Persson J, Formgren J, Israelsson B, et al. . Ultrasound-determined intima-media thickness and atherosclerosis. Direct and indirect validation. Arterioscler Thromb 1994;14:261–4. 10.1161/01.ATV.14.2.261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kablak-Ziembicka A, Tracz W, Przewlocki T, et al. . Association of increased carotid intima-media thickness with the extent of coronary artery disease. Heart 2004;90:1286–90. 10.1136/hrt.2003.025080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lamotte C, Iliescu C, Libersa C, et al. . Increased intima-media thickness of the carotid artery in childhood: a systematic review of observational studies. Eur J Pediatr 2011;170:719–29. 10.1007/s00431-010-1328-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hodis HN, Mack WJ, LaBree L, et al. . The role of carotid arterial intima-media thickness in predicting clinical coronary events. Ann Intern Med 1998;128:262–9. 10.7326/0003-4819-128-4-199802150-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. van den Oord SC, Sijbrands EJ, ten Kate GL, et al. . Carotid intima-media thickness for cardiovascular risk assessment: systematic review and meta-analysis. Atherosclerosis 2013;228:1–11. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2013.01.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Stein JH, Korcarz CE, Hurst RT, et al. . Use of carotid ultrasound to identify subclinical vascular disease and evaluate cardiovascular disease risk: a consensus statement from the American Society of Echocardiography Carotid Intima-Media Thickness Task Force. Endorsed by the Society for Vascular Medicine. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2008;21:93–111. 10.1016/j.echo.2007.11.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bots ML, Sutton-Tyrrell K. Lessons from the past and promises for the future for carotid intima-media thickness. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012;60:1599–604. 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.12.061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Liao D, Arnett DK, Tyroler HA, et al. . Arterial stiffness and the development of hypertension. The ARIC study. Hypertension 1999;34:201–6. 10.1161/01.HYP.34.2.201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tentolouris N, Liatis S, Moyssakis I, et al. . Aortic distensibility is reduced in subjects with type 2 diabetes and cardiac autonomic neuropathy. Eur J Clin Invest 2003;33:1075–83. 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2003.01279.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Doyon A, Kracht D, Bayazit AK, et al. . Carotid artery intima-media thickness and distensibility in children and adolescents: reference values and role of body dimensions. Hypertension 2013;62:550–6. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.113.01297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wiegman A, Hutten BA, de Groot E, et al. . Efficacy and safety of statin therapy in children with familial hypercholesterolemia: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2004;292:331–7. 10.1001/jama.292.3.331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Woo KS, Chook P, Yu CW, Cw Y, et al. . Effects of diet and exercise on obesity-related vascular dysfunction in children. Circulation 2004;109:1981–6. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000126599.47470.BE [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Braamskamp M, Langslet G, McCrindle BW, et al. . Effect of Rosuvastatin on Carotid Intima-Media Thickness in Children With Heterozygous Familial Hypercholesterolemia: The CHARON Study (Hypercholesterolemia in Children and Adolescents Taking Rosuvastatin Open Label). Circulation 2017;136:359–66. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.025158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zhao J, Cheema FA, Bremner JD, et al. . Heritability of carotid intima-media thickness: a twin study. Atherosclerosis 2008;197:814–20. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2007.07.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sacco RL, Blanton SH, Slifer S, et al. . Heritability and linkage analysis for carotid intima-media thickness: the family study of stroke risk and carotid atherosclerosis. Stroke 2009;40:2307–12. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.554121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Fox CS, Polak JF, Chazaro I, et al. . Genetic and environmental contributions to atherosclerosis phenotypes in men and women: heritability of carotid intima-media thickness in the Framingham Heart Study. Stroke 2003;34:397–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ryder JR, Pankratz ND, Dengel DR, et al. . Heritability of vascular structure and function: a parent-child study. J Am Heart Assoc 2017;6 10.1161/JAHA.116.004757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sanson A, Johnstone R. LSAC Research Consortium, et al Growing Up in Australia takes its first steps. Family Matters 2004;67:46–52. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Edwards B. Growing Up in Australia: the Longitudinal Study of Australian Children: entering adolescence and becoming a young adult. Family Matters 2014;95. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Clifford S, Davies S, Wake M, et al. . Child Health CheckPoint: Cohort summary and methodology of a physical health and biospecimen module for the Longitudinal Study of Australian Children. BMJ Open 2019:9(suupl 3);3–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wake M, Clifford S, York E, et al. . Introducing Growing Up in Australia’s Child Health CheckPoint: A physical health and biomarkers module for the Longitudinal Study of Australian Children. Family Matters 2014;95:15. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Touboul PJ, Hennerici MG, Meairs S, et al. . Mannheim carotid intima-media thickness and plaque consensus (2004-2006-2011). An update on behalf of the advisory board of the 3rd, 4th and 5th watching the risk symposia, at the 13th, 15th and 20th European Stroke Conferences, Mannheim, Germany, 2004, Brussels, Belgium, 2006, and Hamburg, Germany, 2011. Cerebrovasc Dis 2012;34:290–6. 10.1159/000343145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Mancini GB, Abbott D, Kamimura C, et al. . Validation of a new ultrasound method for the measurement of carotid artery intima medial thickness and plaque dimensions. Can J Cardiol 2004;20:1355–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Dawson JD, Sonka M, Blecha MB, et al. . Risk factors associated with aortic and carotid intima-media thickness in adolescents and young adults: the Muscatine Offspring Study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009;53:2273–9. 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.03.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Marlatt KL, Kelly AS, Steinberger J, et al. . The influence of gender on carotid artery compliance and distensibility in children and adults. J Clin Ultrasound 2013;41:340–6. 10.1002/jcu.22015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Koivistoinen T, Virtanen M, Hutri-Kähönen N, et al. . Arterial pulse wave velocity in relation to carotid intima-media thickness, brachial flow-mediated dilation and carotid artery distensibility: the Cardiovascular Risk in Young Finns Study and the Health 2000 Survey. Atherosclerosis 2012;220:387–93. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2011.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Juonala M, Järvisalo MJ, Mäki-Torkko N, et al. . Risk factors identified in childhood and decreased carotid artery elasticity in adulthood: the Cardiovascular Risk in Young Finns Study. Circulation 2005;112:1486–93. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.502161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bond L, Clements J, Bertalli N, et al. . A comparison of self-reported puberty using the Pubertal Development Scale and the Sexual Maturation Scale in a school-based epidemiologic survey. J Adolesc 2006;29:709–20. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2005.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kuczmarski RJ, Ogden CL, Grummer-Strawn LM, et al. . CDC growth charts: United States. Adv Data 2000;314:1–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Census of population and housing: Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas (SEIFA, 2011. Cat. no. 2033.0.55.001, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Heeringa SG, West BT, Berglund PA. Applied survey data analysis: CRC Press, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ellul S, Hiscock R, Mensah FK, et al. . Longitudinal Study of Australian Children’s Child Health CheckPoint Technical Paper 1: Weighting and non-response. Melbourne: Murdoch Children’s Research Institute, 2018. 10.25374/MCRI.5687593 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Järvisalo MJ, Jartti L, Näntö-Salonen K, et al. . Increased aortic intima-media thickness: a marker of preclinical atherosclerosis in high-risk children. Circulation 2001;104:2943–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Jourdan C, Wühl E, Litwin M, et al. . Normative values for intima-media thickness and distensibility of large arteries in healthy adolescents. J Hypertens 2005;23:1707–15. 10.1097/01.hjh.0000178834.26353.d5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Maas AH, Appelman YE. Gender differences in coronary heart disease. Neth Heart J 2010;18:598–603. 10.1007/s12471-010-0841-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Carroll RJ. Measurement error in epidemiologic studies. Encyclopedia of biostatistics 1998. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-020264supp001.pdf (169.6KB, pdf)