Abstract

Objectives

Outcomes in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) are determined by both cancer characteristics and liver disease severity. This study aims to validate the use of inpatient electronic health records to determine liver disease severity from treatment and procedure codes.

Design

Retrospective observational study.

Setting

Two National Health Service (NHS) cancer centres in England.

Participants

339 patients with a new diagnosis of HCC between 2007 and 2016.

Main outcome

Using inpatient electronic health records, we have developed an optimised algorithm to identify cirrhosis and determine liver disease severity in a population with HCC. The diagnostic accuracy of the algorithm was optimised using clinical records from one NHS Trust and it was externally validated using anonymised data from another centre.

Results

The optimised algorithm has a positive predictive value (PPV) of 99% for identifying cirrhosis in the derivation cohort, with a sensitivity of 86% (95% CI 82% to 90%) and a specificity of 98% (95% CI 96% to 100%). The sensitivity for detecting advanced stage cirrhosis is 80% (95% CI 75% to 87%) and specificity is 98% (95% CI 96% to 100%), with a PPV of 89%.

Conclusions

Our optimised algorithm, based on inpatient electronic health records, reliably identifies and stages cirrhosis in patients with HCC. This highlights the potential of routine health data in population studies to stratify patients with HCC according to liver disease severity.

Keywords: hepatology, hepatobiliary tumours, epidemiology

Strengths and limitations of this study.

First study to use inpatient electronic health records to identify and stage cirrhosis severity in a population with hepatocellular carcinoma.

The presence of cirrhosis predicted by inpatient electronic health records is accurate and advanced stage disease identified by the algorithm is associated with increased disease severity scores in validation.

A potential limitation is a variation in coding practices between centres and over time.

This algorithm may be used in population studies to understand outcomes in hepatocellular carcinoma, which require an assessment of liver disease severity.

Introduction

Primary liver cancer accounts for 2% of all cancers diagnosed in the UK, with approximately 5700 new cases each year1 and these are most commonly hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). It is estimated that 70%–90% of HCC occurs in the background of cirrhosis2 3 and global outcomes are poor despite a number of treatment options.4 Curative treatments may be limited by poor liver function due to underlying cirrhosis, or late presentation of advanced cancer in patients not known to have cirrhosis. Therefore, to understand outcomes of patients with HCC, it is essential to consider the presence and severity of cirrhosis in all analyses.

Population-based cancer registry data are used to describe trends in cancer incidence and mortality in a number of cancer sites, as well as regional variation in clinical outcomes.5 In HCC research, registry data have been used to describe geographical variation in incidence, survival and treatment allocation in France.6 In England, the National Cancer Registration and Analysis Service (NCRAS) dataset contains patient-level information about individuals with HCC, but information on the presence of cirrhosis is not currently included. Also, blood test results are not collected, so cirrhosis severity using tools such as the Child-Pugh score and the Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score cannot be calculated.

Previous international studies have outlined methods to use electronic health records (EHRs) to identify cirrhosis.7–11 In the UK, Ratib et al used a combination of inpatient and outpatient records to identify cirrhosis and its complications, including oesophageal varices and ascites.12 These complications relate to advanced stage or ‘decompensated’ cirrhosis and they often result in admitted patient care. In England, all inpatient records are captured by the Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) database, which is linked to the cancer registry data within NCRAS.

We present a clinical validation study using EHRs from two regional cancer centres in England to assess the performance of an algorithm to determine the presence and severity of cirrhosis using the local inpatient HES records, which are subsequently transmitted to the national HES dataset. This study aims to demonstrate that the use of routinely collected diagnosis and treatment codes from inpatient records alone is sufficient to identify cirrhosis and grade its severity in patients with HCC. This will facilitate future studies of outcomes for patients with HCC by considering the severity of any underlying cirrhosis.

Methods

All patients diagnosed with HCC between 1 January 2007 and 31 December 2016 and residents in the secondary care catchment area of Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust (LTHT) were identified. The diagnosis of HCC was confirmed for all patients in a weekly hepatobiliary cancer multidisciplinary team (MDT) meeting and the reporting of all cases to the national cancer registry is mandatory. HCC was usually diagnosed by radiology, using the European Association for the Study of the Liver non-invasive criteria,13 and if indicated a targeted biopsy was performed. Live minutes are taken at these meetings and details collected into the clinical records along with a confirmed date of diagnosis. The cohort was identified from the data submitted to the central registry. We only had access to the inpatient codes from hospital episodes which occurred at LTHT. Therefore, only those patients registered with a Clinical Commissioning Group local to LTHT were included, where we would expect them to have received their inpatient cirrhosis care. The local HES records were searched to identify inpatient episodes containing codes related to cirrhosis within the International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision (ICD-10) and Office of Population, Censuses and Surveys’ Classification, fourth revision (OPCS4), together with the corresponding time interval from the HCC diagnosis date. These codes are used routinely for reimbursement and are submitted to the national HES dataset. An algorithm was developed to characterise patients from these codes, and comparison made with the clinical records. External validation of the algorithm was undertaken using the same search within the local HES records for patients diagnosed with HCC between 1 January 2013 and 31 December 2014 and local to Royal Liverpool and Broadgreen University Hospitals NHS Trust (RLBUHT).

Patient and public involvement

Patients and public were not involved in this study.

Identification of cirrhosis

To determine the presence of cirrhosis at HCC diagnosis, episodes containing cirrhosis-related codes which occurred up to 5 years before the HCC diagnosis date were initially included. However, to improve the sensitivity of the algorithm by maximising the number of available inpatient codes, additional episodes occurring after HCC diagnosis were subsequently included. This approach assumes that if an inpatient cirrhosis code occurs after the HCC diagnosis, the patient is likely to have had cirrhosis at the time of HCC diagnosis. The time frame post-HCC diagnosis of included episodes was increased incrementally and the performance of the algorithm tested to validate this assumption.

Different definitions of cirrhosis within ICD-10 have been used in population studies.14 Some investigators7 8 used cirrhosis diagnosis codes only, whereas others9 11 also included varices codes. Ratib et al 15 additionally included OPCS4 procedure codes for treatment of varices and version 1 of our algorithm is based on this approach. Patients are classified as cirrhotic if they had inpatient episodes containing the diagnosis and treatment codes for cirrhosis or varices outlined in table 1. In version 2, a broader definition of cirrhosis proposed by Leon and McCambridge16 was used, including codes for ‘alcoholic liver disease’ (ALD, K70.9) and ‘alcoholic hepatic failure’ (AHF, K70.4). To assess the accuracy of including ascites as a cirrhosis-defining condition in HCC, codes for ascites and paracentesis were included in version 3 of the algorithm. Previously, some investigators9 15 excluded ascites in their definitions because this may be due to malignancy in the absence of cirrhosis in a general population. In version 4, only ascites codes occurring before the HCC diagnosis date were included.

Table 1.

Treatment and procedure codes included in the algorithm to determine cirrhosis status and cirrhosis severity

| Codes | |

| Cirrhosis diagnoses (ICD-10): | |

| Cirrhosis | K70.3, K71.7, K72.1, K74.4, K74.5, K74.6, K76.6, K72.1, K72.9 |

| Alcoholic hepatic failure | K70.4 |

| Alcoholic liver disease | K70.9 |

| Ascites | R18.X |

| Varices | I85.9, I86.4, I98.2 |

| Bleeding varices | I85.0, I98.3 |

| Cirrhosis treatments (OPCS4): | |

| Treatment of ascites | T46.1, T46.2, J06.1, J06.2 |

| Treatment of varices | G10.4, G10.8, G10.9, G14.4, G17.4, G43.4, G43.7, J06.1, J06.2 |

| Gastrointestinal haemorrhage (ICD-10): | |

| Gastrointestinal haemorrhage | K92.0, K92.1, K92.2 |

The clinical records were reviewed between April and August 2018 and data abstracted by three clinical investigators (RJD, VB and JS), each experienced hepatology fellows working in this field for at least 2 years. A standard abstraction form was used and discrepancies were resolved by consensus view. Cirrhosis at the time of HCC diagnosis was identified based on explicit mention of cirrhosis in the clinical record or MDT minutes, evidence of portal hypertension on radiological imaging or endoscopy reports, explicit mention of cirrhosis on liver biopsy or a consistent result on transient elastography. This was used as the gold standard for testing different versions of the algorithm to classify cirrhosis status. For comparison, published algorithms7–9 15 were also tested in the LTHT cohort of patients with HCC.

Classification of cirrhosis severity

Cirrhosis severity was classified using the Baveno IV consensus.17 Compensated cirrhosis is defined by Baveno stage 1 (no ascites or varices) and stage 2 (non-bleeding varices). Decompensated cirrhosis is defined by Baveno stage 3 (ascites, with or without varices) and stage 4 (bleeding varices, with or without ascites). In this model of the natural history of cirrhosis,3 patients progress to a higher Baveno stage over time, but do not return to a lower stage. For each hospital episode, the Baveno stage and compensation status were calculated using the diagnosis and treatment codes for ascites and varices in table 1. Three definitions of bleeding varices were tested; version A (based on Goldberg et al 10) contains ICD-10 codes for variceal bleeding, version B (based on Ratib et al 12) also includes OPCS4 codes for treatment of varices, and version C limits the inclusion of these treatment codes to those occurring in a hospital episode with a concurrent ICD-10 code for gastrointestinal haemorrhage (K92.0, K92.1 and K92.2). This is to distinguish between bleeding varices and the prophylactic treatment of non-bleeding varices.

Cirrhosis severity at the time of HCC diagnosis was determined by the highest Baveno stage recorded in hospital episodes occurring in the 5 years before HCC diagnosis. In order to increase the accuracy of this assessment, additional episodes occurring after the HCC diagnosis date were also included. The time frame post-HCC diagnosis of included episodes was increased incrementally up to 4 months. The clinical records were reviewed to determine the true Baveno stage at the time of HCC diagnosis, along with routine blood tests for calculation of Child Pugh and MELD scores. Baveno stage 2 was identified by non-bleeding varices explicitly mentioned in the clinical records or endoscopy reports, but excluded a report of portal hypertensive gastropathy. Baveno stage 3 was identified by explicit mention of ascites in the clinical record, requiring diuretic therapy or paracentesis, but a small volume of ascites only visible on cross-sectional imaging was excluded. Baveno stage 4 was identified by explicit mention of variceal haemorrhage in the clinical record or endoscopy reports. Clinical evidence of decompensation was identified by the presence of bleeding varices or ascites, as per the Baveno IV classification.

Statistical analysis

Data management and statistical analysis were performed using Stata V.15.1 (StataCorp). The diagnostic accuracy of the algorithm to identify cirrhosis status and decompensation status involved comparison of sensitivity and specificity derived from 2×2 contingency tables.18 For Baveno stage, agreement between the algorithm and the clinical records were assessed using the kappa statistic. This is used to assess observer agreement for categorical variables and allows for agreement occurring by chance.19 20

Results

Study population

During the study period, 289 patients (median age 69, 79% male) with a new diagnosis of HCC were included (table 2) and 249 (86.2%) of these had an inpatient record. Review of the clinical record identified 191 (66%) of these as cirrhotic at HCC diagnosis, 50 (26%) of whom had evidence of previous decompensation. The median age of the cirrhotic group was 67 compared with 73 in the non-cirrhotic group (p<0.001). An additional 15 patients had histological evidence of advanced fibrosis but cirrhosis was not mentioned explicitly in the clinical records. Among the patients who did not have an inpatient record, 12 had cirrhosis according to outpatient case note review. In the external validation cohort at RLBUHT, 50 patients meeting the inclusion criteria were assessed (median age 71, 82% male), 31 (62%) of whom were cirrhotic and 11 (35%) with previous decompensation.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of the LTHT cohort

| Characteristic | Total N (%) |

No cirrhosis N (%) |

Cirrhosis N (%) |

P value |

| 289 | 98 (33.9%) | 191 (66.1%) | ||

| Age group | ||||

| <50 | 22 (7.6) | 10 (10.2) | 12 (6.3) | 0.26 |

| 50–59 | 49 (17.0) | 10 (10.2) | 39 (20.4) | 0.04 |

| 60–69 | 81 (28.0) | 18 (18.4) | 63 (33.0) | 0.03 |

| 70–79 | 92 (31.8) | 31 (31.6) | 61 (31.9) | 0.95 |

| 80+ | 45 (15.6) | 29 (29.6) | 16 (8.4) | <0.001 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 228 (78.0) | 76 (77.6) | 152 (79.6) | 0.83 |

| Female | 61 (21.1) | 22 (22.4) | 39 (20.4) | 0.73 |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| White | 252 (87.1) | 87 (88.8) | 165 (86.4) | 0.86 |

| Black | 12 (4.2) | 5 (5.1) | 7 (3.7) | 0.58 |

| South Asian | 12 (4.2) | 2 (2.0) | 10 (5.2) | 0.21 |

| Chinese | 4 (1.4) | 0 | 4 (2.1) | 0.15 |

| Other Ethnic group | 4 (1.4) | 1 (1.0) | 3 (1.6) | 0.70 |

| Not stated | 5 (1.7) | 3 (3.1) | 2 (1.0) | 0.22 |

| Aetiology | ||||

| HCV | 44 (15.2) | 4 (4.1) | 40 (20.9) | <0.001 |

| HBV | 17 (5.9) | 5 (5.1) | 12 (6.3) | 0.69 |

| PBC | 7 (2.4) | 0 | 7 (3.7) | 0.06 |

| AIH | 3 (1.0) | 0 | 3 (1.6) | 0.21 |

| Haemochromatosis | 19 (6.6) | 5 (5.1) | 14 (7.3) | 0.48 |

| Alcohol | 68 (23.5) | 4 (4.1) | 64 (33.5) | <0.001 |

| NAFLD | 43 (14.9) | 13 (13.3) | 30 (15.7) | 0.60 |

| Other/unknown | 88 (30.4) | 67 (68.4) | 21 (11.0) | <0.001 |

| MELD | ||||

| <10 | 90 (47.1) | |||

| 10–14 | 73 (38.2) | |||

| 15–19 | 21 (11.0) | |||

| 20+ | 7 (3.7) | |||

| Child-Pugh | ||||

| A | 131 (68.6) | |||

| B | 44 (23.0) | |||

| C | 16 (8.4) | |||

| Previous decompensation | ||||

| Ascites | 37 (19.3) | |||

| Variceal bleed | 13 (6.8) |

AIH, autoimmune hepatitis; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; LTHT, Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust; MELD, Model for End-Stage Liver Disease; NAFLD, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease; PBC, primary biliary cirrhosis.

Identification of cirrhosis

Limiting the inclusion of episodes to those occurring before the HCC diagnosis results in a sensitivity of less than 50% for cirrhosis detection (table 3). When additional episodes are included up until 3 years after the HCC diagnosis, the sensitivity increases to greater than 80% for all versions of the algorithm, without significant loss of specificity.

Table 3.

Performance of different versions of the cirrhosis status algorithm

| Time post-HCC diagnosis/days | Algorithm 1 No ascites - ALD - AHF |

Algorithm 2 No ascites +ALD + AHF |

Algorithm 3 Ascites +ALD + AHF |

Algorithm 4 Pre-HCC ascites +ALD + AHF |

||||||||||||

| Sens | 95% CI | Spec | 95% CI | Sens | 95% CI | Spec | 95% CI | Sens | 95% CI | Spec | 95% CI | Sens | 95% CI | Spec | 95% CI | |

| 0 | 0.45 | 0.39 to 0.51 | 1.00 | 1.00 to 1.00 | 0.47 | 0.41 to 0.52 | 1.00 | 1.00 to 1.00 | 0.49 | 0.43 to 0.54 | 1.00 | 1.00 to 1.00 | 0.49 | 0.43 to 0.54 | 1.00 | 1.00 to 1.00 |

| 30 | 0.52 | 0.47 to 0.58 | 1.00 | 1.00 to 1.00 | 0.54 | 0.49 to 0.60 | 1.00 | 1.00 to 1.00 | 0.57 | 0.51 to 0.63 | 0.99 | 0.98 to 1.00 | 0.57 | 0.51 to 0.63 | 1.00 | 1.00 to 1.00 |

| 60 | 0.60 | 0.55 to 0.66 | 1.00 | 1.00 to 1.00 | 0.64 | 0.58 to 0.69 | 1.00 | 1.00 to 1.00 | 0.66 | 0.61 to 0.72 | 0.98 | 0.96 to 1.00 | 0.66 | 0.61 to 0.71 | 1.00 | 1.00 to 1.00 |

| 90 | 0.66 | 0.61 to 0.72 | 1.00 | 1.00 to 1.00 | 0.70 | 0.65 to 0.75 | 1.00 | 1.00 to 1.00 | 0.73 | 0.68 to 0.78 | 0.97 | 0.95 to 0.99 | 0.72 | 0.67 to 0.77 | 1.00 | 1.00 to 1.00 |

| 120 | 0.69 | 0.64 to 0.74 | 1.00 | 1.00 to 1.00 | 0.73 | 0.68 to 0.78 | 1.00 | 1.00 to 1.00 | 0.75 | 0.70 to 0.80 | 0.97 | 0.95 to 0.99 | 0.75 | 0.70 to 0.80 | 1.00 | 1.00 to 1.00 |

| 150 | 0.72 | 0.67 to 0.77 | 1.00 | 1.00 to 1.00 | 0.76 | 0.72 to 0.81 | 1.00 | 1.00 to 1.00 | 0.79 | 0.74 to 0.83 | 0.96 | 0.94 to 0.98 | 0.78 | 0.73 to 0.83 | 1.00 | 1.00 to 1.00 |

| 180 | 0.73 | 0.68 to 0.78 | 0.99 | 0.98 to 1.00 | 0.77 | 0.73 to 0.82 | 0.99 | 0.98 to 1.00 | 0.80 | 0.75 to 0.84 | 0.95 | 0.92 to 0.97 | 0.79 | 0.74 to 0.84 | 0.99 | 0.98 to 1.00 |

| 365 | 0.76 | 0.71 to 0.81 | 0.99 | 0.98 to 1.00 | 0.81 | 0.76 to 0.85 | 0.99 | 0.98 to 1.00 | 0.83 | 0.78 to 0.87 | 0.94 | 0.91 to 0.97 | 0.82 | 0.78 to 0.87 | 0.99 | 0.98 to 1.00 |

| 730 | 0.80 | 0.76 to 0.85 | 0.98 | 0.96 to 1.00 | 0.84 | 0.80 to 0.88 | 0.98 | 0.96 to 1.00 | 0.87 | 0.83 to 0.91 | 0.95 | 0.93 to 0.98 | 0.85 | 0.81 to 0.89 | 0.98 | 0.96 to 1.00 |

| 1095 | 0.81 | 0.77 to 0.86 | 0.98 | 0.96 to 1.00 | 0.85 | 0.81 to 0.89 | 0.98 | 0.96 to 1.00 | 0.88 | 0.84 to 0.92 | 0.92 | 0.89 to 0.95 | 0.86 | 0.82 to 0.90 | 0.98 | 0.96 to 1.00 |

| Total follow-up | 0.81 | 0.77 to 0.86 | 0.98 | 0.96 to 1.00 | 0.85 | 0.81 to 0.89 | 0.98 | 0.96 to 1.00 | 0.88 | 0.84 to 0.92 | 0.92 | 0.89 to 0.95 | 0.86 | 0.82 to 0.90 | 0.98 | 0.96 to 1.00 |

ALD, alcoholic liver disease; AHF, alcoholic hepatic failure; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; Spec, specificity; Sens, sensitivity.

The sensitivity of algorithm 1 is increased by including ALD and AHF (version 2), and further increased by including ascites (version 3). However, the inclusion of ascites also reduces the specificity. This is overcome by limiting the inclusion of ascites to episodes that occurred before the HCC diagnosis (version 4). Using this optimised algorithm and including records up to 3 years post-HCC diagnosis, the sensitivity is 86% (95% CI 82% to 90%) and the specificity is 98% (95% CI 96% to 100%), with a positive predictive value (PPV) of 99% and negative predictive value (NPV) of 79% (95% CI 74% to 83%) (online supplementary table 1). For external validation, when V.4 of the algorithm was applied to the RLBUHT cohort with 3 years of follow-up, the sensitivity was 79% and specificity was 100%. Additionally, version 4 of the algorithm outperformed published algorithms for cirrhosis detection when they were applied to the LTHT cohort of patients with HCC (table 4).

Table 4.

Performance of different published algorithms for cirrhosis detection in the LTHT cohort of patients with HCC

| Algorithm | Sensitivity (%) | 95% CI | Specificity (%) | 95% CI | PPV (%) | 95% CI | |||

| Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | ||||

| Kramer et al 7 | 72 | 67 | 77 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Jepsen et al 8 | 71 | 66 | 76 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Nehra et al 9 | 80 | 76 | 85 | 98 | 96 | 100 | 99 | 97 | 100 |

| Ratib et al 15 | 80 | 76 | 85 | 98 | 96 | 100 | 99 | 97 | 100 |

| Algorithm 4 | 86 | 82 | 90 | 98 | 96 | 100 | 99 | 97 | 100 |

HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; LTHT, Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust; PPV, positive predictive value.

bmjopen-2018-028571supp001.pdf (350.7KB, pdf)

Classification of cirrhosis severity

Table 5 shows the performance of the three versions of the algorithm for determining cirrhosis severity according to Baveno stage. Compared with version A, there is slightly less agreement between the calculated Baveno stage and the clinical record in version B, where Baveno stage 4 is defined by procedure codes for varices. Similarly, the sensitivity for detecting decompensation (defined by Baveno stages 3 and 4) is increased in version B, but with reduced specificity (online supplementary table 2). Agreement between the algorithm and the clinical record is optimised in version C, when bleeding varices are defined by a concurrent gastrointestinal haemorrhage code. Agreement was further improved when episodes occurring within 60 days of the registered HCC diagnosis were included. The performance characteristics of the component codes are summarised in online supplementary tables 3 and 4; the sensitivity for detecting bleeding varices is increased in algorithm B, but the PPV and overall agreement with the Baveno stage is reduced due to the misclassification of non-bleeding varices. The sensitivity for detecting ascites is increased when both diagnosis and paracentesis procedure codes are included.

Table 5.

Performance of different versions of the Baveno stage algorithm

| Time after HCC diagnosis/days | Algorithm A Variceal bleeding codes |

Algorithm B Variceal bleeding codes or treatment codes |

Algorithm C Variceal bleeding codes or treatment codes+UGIB |

|||

| Correct Baveno stage (%) | Κ-statistic | Correct Baveno stage (%) | Κ-statistic | Correct Baveno stage (%) | Κ-statistic | |

| 0 | 80 | 0.67 | 80 | 0.67 | 81 | 0.70 |

| 30 | 82 | 0.70 | 81 | 0.70 | 83 | 0.73 |

| 60 | 83 | 0.71 | 82 | 0.71 | 84 | 0.74 |

| 90 | 81 | 0.69 | 80 | 0.69 | 82 | 0.71 |

| 120 | 81 | 0.69 | 80 | 0.69 | 82 | 0.71 |

HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; UGIB, Upper gastrointestinal bleeding.

Using version C with a 60-day interval in the LTHT cohort, agreement between the clinical record and calculated Baveno stage was 84%, with a kappa coefficient of 0.74 (95% CI 71% to 77%). The sensitivity for detecting prior decompensation is 80% (95% CI 75% to 85%) and specificity is 98% (95% CI 96% to 100%), with a PPV of 89% (95% CI 85% to 93%) and NPV of 96% (95% CI 94% to 98%). When this version was applied to the RLBUHT cohort for external validation, the agreement of Baveno stage with the clinical record was 81% (kappa 0.70). The sensitivity for detecting decompensation was 73% and specificity was 90%.

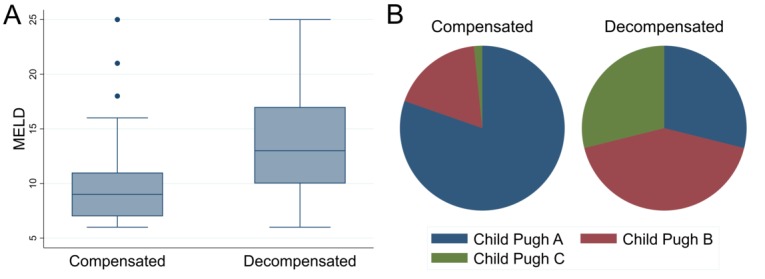

Finally, among the 167 LTHT patients identified as cirrhotic by the algorithm, 45 (27%) were coded with prior decompensation. At the time of HCC diagnosis, Child-Pugh class and MELD scores were each higher in those individuals identified with decompensation (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Box-and-whisker plots showing the distribution of MELD scores (A) and pie graphs showing the distribution of Child-Pugh class (B) within compensated and decompensated cirrhosis groups determined by the algorithm. MELD, Model for End-Stage Liver Disease.

Discussion

Main findings

This study demonstrates the reliability of an algorithm using inpatient HES records to identify and stage cirrhosis in patients with HCC. This is the first such algorithm validated in a UK population that uses only inpatient codes. Using inpatient codes from the whole follow-up period improves the sensitivity of the algorithm in cirrhosis identification, without loss of specificity. This validates the assumption that if a patient had an inpatient cirrhosis code during follow-up, they had cirrhosis at the time of HCC diagnosis. Using a broad definition of cirrhosis (versions 2–4) improves sensitivity and accounts for variations in coding practice in which ALD and AHF are coded synonymously with cirrhosis. Excluding ascites after HCC diagnosis (version 4) improves the specificity; ascites in liver disease without HCC is most likely to be due to cirrhosis, whereas it may be malignant ascites in the context of HCC. Algorithm 4 is an improvement over published algorithms for cirrhosis detection when they are applied to our cohort of patients with HCC. Algorithm C (for assessing cirrhosis severity) also outperformed published versions in this population. Inclusion of a concurrent gastrointestinal haemorrhage code alongside variceal procedures distinguishes between treatment of bleeding varices and treatment of non-bleeding varices for primary prevention.

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of this study are the systematic development of an algorithm which uses routinely available inpatient episode codes, and its applicability to large population studies in HCC. These patients often require hospital admission to manage complications in advanced cirrhosis and to receive HCC therapies, or day case procedures such as paracentesis and endoscopy which are also coded in the HES dataset. The high-performance characteristics (particularly the PPVs) derived from inpatient codes here are in part a consequence of the high pretest probability of cirrhosis in patients with HCC. This observation is supported by the improved PPVs seen in existing algorithms in our cohort. In summary, this suggests that inpatient episodes are sufficient for high-quality analyses of the impact of cirrhosis and its severity on the outcomes of patients with HCC.

This study benefits from robust case note evaluation, using both a development and external validation cohort. In the UK, previous validation of inpatient coding was achieved using free-text analysis of primary care and death certification data,12 and the original case note validation of the cirrhosis algorithm included only 36 patients.21 The algorithm benefits from exploiting the ‘anchor point’ of the HCC diagnosis date, so that inpatient codes can be associated with a time interval. This has led to optimised cirrhosis detection and severity classification. The algorithm for cirrhosis detection was optimised using 3 years of follow-up after HCC diagnosis, but the high sensitivity and specificity using 1-year of follow-up may be sufficient in some settings.

The limitations include its location in specialist cancer centres, which may not reflect coding practices throughout the UK and these may change over time. However, portal hypertensive complications are common and often result in inpatient care and, since these are high-cost procedures, we anticipate them to be reliably coded. The analysis was limited to patients local to the two centres, in order to capture cirrhosis-related episodes. Additional episodes may have been missed if patients were admitted elsewhere, but these would be captured by the algorithm when extended to a national dataset. The majority of patients had an inpatient record, suggesting high rates of hospital admission in patients with cirrhosis and those undergoing HCC treatment. The limitations of using inpatient codes alone are common to other studies which have utilised the linked inpatient HES dataset to produce impactful analyses.22 23

The proportion of patients with cirrhosis identified from their clinical records was 66% and this is lower than previous reports.2 3 By limiting to inpatient codes, the algorithm missed 12/191 (6.3%) patients with cirrhosis and those with histological evidence of advanced fibrosis were classified as non-cirrhotic. Many patients were diagnosed with HCC in the absence of known liver disease; 68.4% of those without cirrhosis had no known underlying liver disease aetiology (table 2). If patients had advanced cancer at presentation, their clinical record may not have explicitly stated the presence of cirrhosis. Additionally, they may have not been investigated further to establish a diagnosis of cirrhosis if not clinically appropriate. It is also notable that there was a high proportion of patients aged over 80 years who were not identified to have cirrhosis. Finally, the definition of decompensation using the Baveno IV classification is limited because it does not capture hepatic encephalopathy (HE), which may occur without variceal bleeding or ascites. HE can be coded in ICD-10 code as ‘hepatic coma’, but we found that this was used uncommonly in our cohort and so we did not broaden our definition of decompensation beyond that used by Ratib et al.12

Implications

This algorithm can be applied to population cancer registries in the UK, enabling the identification and staging of cirrhosis in patients with HCC. This is essential for assessing clinical outcomes in population-based studies of individuals with HCC both in the UK and elsewhere. It is anticipated that this will lead to a better understanding of outcomes in HCC, including progression of underlying liver disease severity as well as overall survival. The algorithm may also be used in other population-based applications, which require the identification of cirrhosis and an assessment of severity.

In this study, we demonstrated the use of inpatient HES records to determine the cirrhosis severity at the time of HCC diagnosis. The algorithm may be adapted to classify the Baveno stage at different time intervals following HCC diagnosis or date of treatment, so that subsequent cirrhosis decompensation events can be identified over time. This approach is likely to have value in other health systems and we anticipate that the algorithm described will be evaluated by other investigators in outcomes-oriented research in cirrhosis and HCC.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates the reliability of an algorithm based on inpatient EHRs to stratify patients with HCC according to the presence and severity of cirrhosis. It may be used in routine health data in order to assess outcomes in HCC in population studies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work uses data provided by patients and collected by the NHS as part of their care and support. The planning of this project was discussed with members of the HCC-UK Partnership, which is coordinated by AB.

Footnotes

Contributors: IAR and RJD had the original idea for the study and AB, AD, TC and EM contributed to its design and planning. RJD, JS and VB performed the case note reviews. RJD was responsible for data management, statistical analyses and wrote the first draft of the paper. IAR reviewed the paper critically and VB, AB, JS, AD, TC and EM all approved the final version.

Funding: RJD and JS were funded by clinical research fellowships at Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust. AB is an analyst within Public Health England and receives funding from the British Association for the Study of the Liver (BASL) as part of the HCC-UK Partnership.

Disclaimer: No industrial sponsor had input into study planning, discussion of results or manuscript preparation.

Competing interests: VB has received an unrestricted educational grant from Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb and Sirtex.

Ethics approval: This retrospective study comprises an assessment of the accuracy of clinical coding for service evaluation and as such does not require formal ethical approval. All patient data were anonymised and permission was granted from the Caldicott Guardian for sharing of routinely collected anonymised data.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Statistical code is available from thecorresponding author RJD.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Cancer Research UK. Liver Cancer Statistics. 2015. https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/statistics-by-cancer-type/liver-cancer#heading-Zero (Cited 5 Jul 2018).

- 2. El-Serag HB, Rudolph KL. Hepatocellular carcinoma: epidemiology and molecular carcinogenesis. Gastroenterology 2007;132:2557–76. 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.04.061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. D’Amico G, Garcia-Tsao G, Pagliaro L. Natural history and prognostic indicators of survival in cirrhosis: a systematic review of 118 studies. J Hepatol 2006;44:217–31. 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.10.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. El-Serag HB. Hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2011;365:1118–27. 10.1056/NEJMra1001683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Coleman MP, Forman D, Bryant H, et al. . Cancer survival in Australia, Canada, Denmark, Norway, Sweden, and the UK, 1995–2007 (the International Cancer Benchmarking Partnership): an analysis of population-based cancer registry data. The Lancet 2011;377:127–38. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62231-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Goutté N, Sogni P, Bendersky N, et al. . Geographical variations in incidence, management and survival of hepatocellular carcinoma in a Western country. J Hepatol 2017;66:537–44. 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.10.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kramer JR, Davila JA, Miller ED, et al. . The validity of viral hepatitis and chronic liver disease diagnoses in Veterans Affairs administrative databases. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2008;27:274–82. 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03572.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jepsen P, Ott P, Andersen PK, et al. . Clinical course of alcoholic liver cirrhosis: a Danish population-based cohort study. Hepatology 2010;51:1675–82. 10.1002/hep.23500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nehra MS, Ma Y, Clark C, et al. . Use of administrative claims data for identifying patients with cirrhosis. J Clin Gastroenterol 2013;47:e50–4. 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3182688d2f [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Goldberg D, Lewis J, Halpern S, et al. . Validation of three coding algorithms to identify patients with end-stage liver disease in an administrative database. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2012;21:765–9. 10.1002/pds.3290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lapointe-Shaw L, Georgie F, Carlone D, et al. . Identifying cirrhosis, decompensated cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma in health administrative data: A validation study. PLoS One 2018;13:e0201120 10.1371/journal.pone.0201120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ratib S, Fleming KM, Crooks CJ, et al. . 1 and 5 year survival estimates for people with cirrhosis of the liver in England, 1998-2009: a large population study. J Hepatol 2014;60:282–9. 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.09.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. European Association For The Study Of The Liver European Organisation For Research And Treatment Of Cancer. EASL-EORTC clinical practice guidelines: management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 2012;56:908–43. 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ratib S, West J, Fleming KM. Liver cirrhosis in England-an observational study: are we measuring its burden occurrence correctly? BMJ Open 2017;7:e013752 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ratib S, West J, Crooks CJ, et al. . Diagnosis of liver cirrhosis in England, a cohort study, 1998-2009: a comparison with cancer. Am J Gastroenterol 2014;109:190–8. 10.1038/ajg.2013.405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Leon DA, McCambridge J. Liver cirrhosis mortality rates in Britain from 1950 to 2002: an analysis of routine data. Lancet 2006;367:52–6. 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)67924-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. de Franchis R. Evolving consensus in portal hypertension. Report of the Baveno IV consensus workshop on methodology of diagnosis and therapy in portal hypertension. J Hepatol 2005;43:167–76. 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.05.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Alberg AJ, Park JW, Hager BW, et al. . The use of "overall accuracy" to evaluate the validity of screening or diagnostic tests. J Gen Intern Med 2004;19(5 Pt 1):460–5. 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30091.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 1977;33:159–74. 10.2307/2529310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cohen J. A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educ Psychol Meas 1960;20:37–46. 10.1177/001316446002000104 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fleming KM, Aithal GP, Solaymani-Dodaran M, et al. . Incidence and prevalence of cirrhosis in the United Kingdom, 1992-2001: a general population-based study. J Hepatol 2008;49:732–8. 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.05.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Downing A, Aravani A, Macleod U, et al. . Early mortality from colorectal cancer in England: a retrospective observational study of the factors associated with death in the first year after diagnosis. Br J Cancer 2013;108:681–5. 10.1038/bjc.2012.585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Morris EJ, Sandin F, Lambert PC, et al. . A population-based comparison of the survival of patients with colorectal cancer in England, Norway and Sweden between 1996 and 2004. Gut 2011;60:1087–93. 10.1136/gut.2010.229575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-028571supp001.pdf (350.7KB, pdf)