Abstract

Background

Early right heart failure (RHF) occurs commonly in left ventricular assist device (LVAD) recipients, and increased right ventricular (RV) afterload may contribute. Selective pulmonary vasodilators, like phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors (PDE5i), are used off-label to reduce RV afterload prior to LVAD implantation, but the association between preoperative PDE5i use and early RHF after LVAD is unknown.

Methods and Results

We analyzed adult patients from the Interagency Registry for Mechanically Assisted Circulatory Support registry who received a continuous flow (CF) LVAD after 2012. Patients on PDE5i were propensity matched 1:1 to controls. The primary outcome was the incidence of severe early RHF, defined as the composite of death from RHF within 30 days, need for RVAD support within 30 days, or use of inotropes beyond 14 days. Of 11544 CF-LVAD recipients, 1199 (10.4%) received preoperative PDE5i. Compared to controls, patients on PDE5i had higher pulmonary artery systolic pressure (53.4 mmHg vs 49.5 mmHg) and pulmonary vascular resistance (2.6 WU vs 2.3 WU, p < 0.001 for both). Before propensity matching, the incidence of severe early RHF was higher among patients on PDE5i than in controls (29.4% vs 23.1%, unadjusted OR 1.32, 95% CI 1.17–1.50). This association persisted after propensity matching (PDE5i 28.9% vs control 23.7%, OR 1.31, 95% CI 1.09–1.57), driven by a higher incidence of prolonged inotropic support. Similar results were observed across a wide range of subgroups stratified by markers of pulmonary vascular disease and RV dysfunction.

Conclusions

Patients treated with preoperative PDE5i had markers of increased RV afterload and heart failure severity compared to unmatched controls. Even after propensity matching, patients receiving pre-implant PDE5i therapy had higher rates of post-LVAD RHF.

Subject terms: cardiomyopathy, heart failure, LVAD, pulmonary hypertension

Introduction

Despite technological advances in left ventricular assist device (LVAD) therapy, postoperative right heart failure (RHF) remains a frequent clinical problem, occurring in 10–40% of patients.1-3 RHF is associated with increased morbidity and mortality after LVAD implantation.4-6 While multiple factors can contribute to the development of postoperative RHF, the right ventricle (RV) is particularly sensitive to afterload,7 and markers of increased RV afterload have been associated with a higher risk of postoperative RHF.6,8-10

While risk factors for post-LVAD RHF have been identified, there is limited evidence to support specific treatment strategies to reduce this risk. Selective pulmonary vasodilators (PVDs), particularly phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors (PDE5i), are used off-label in patients with advanced heart failure (HF) awaiting heart transplantation or LVAD implant11,12 as a means to mitigate the negative impact of secondary pulmonary hypertension (PH) commonly seen in these patients.13 While no large randomized trials have demonstrated benefit of PVD use in HF,14 small studies have shown a potential improvement in postoperative RHF outcomes with preoperative PVD therapy.15,16 This pharmacologic treatment strategy has yet to be investigated in a large cohort of LVAD recipients.

The primary aim of the present investigation was to evaluate the association between preoperative PDE5i use and the incidence of severe early RHF. We also sought to investigate the association between preoperative PDE5i use and postoperative morbidity and functional capacity, including intensive care unit (ICU) and hospital lengths of stay (LOS), incidence of major bleeding, 6-minute walk distance (6MWD), and quality of life (QOL). We hypothesized that the use of preoperative PDE5i would be associated with lower rates of severe early RHF and reduced postoperative morbidity.

Methods

The data used in this study is available to other investigators by application to the Society for Thoracic Surgeons. The methods and study materials for this study will not be made available to other investigators.

Patient selection

The Interagency Registry for Mechanically Assisted Circulatory Support (INTERMACS) protocol was approved by the National Institutes of Health, the Institutional Review Board at the Data Coordinating Center at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, and each of the institutional review boards of the participating hospitals. We queried INTERMACS for adult patients receiving their first durable continuous flow LVAD (CF-LVAD). Analyses were restricted to patients enrolled between 2012, when data regarding preoperative PDE5i use were first routinely collected, and March 31, 2017. We excluded patients with prior right ventricular assist device (RVAD) implant; atypical LVAD cannulation; upfront placement of a durable biventricular support platform (BiVAD); or missing data regarding use of preoperative PDE5i, post-operative inotropic support, or RVAD implantation.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the incidence of postoperative severe early RHF, defined as the composite of death from RHF or multi-organ system failure (MOSF) within 30 days, need for RVAD within 30 days, or use of inotropes beyond 14 days. When patients had concomitant LVAD and RVAD implanted during the same index procedure, only patients receiving temporary RVADs were counted towards the primary outcome, as these events were more likely to represent an urgent intraoperative decision in the setting of acute RHF. Concomitant durable RVAD implantation (BiVAD), which represented a minority of procedures, was felt to more likely represent a planned RVAD implant strategy to prevent severe early RHF, and such patients were excluded.

Secondary outcomes included individual components of the primary outcome, post-implant ICU and hospital LOS, 3- and 6-month 6MWD, 3- and 6-month Kansas City QOL scores, 6-month overall survival, and the cumulative incidence of major bleeding at 1 month.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (Cary, NC). The authors had full access to the study data and attest to the integrity of the data and the analysis. Data are shown as mean ± standard deviation or median (IQR) for continuous variables and total count (N) with proportion (%) for categorical variables. Baseline characteristics of patients receiving preoperative PDE5i and controls were compared with the student’s T-test or chi-square tests as appropriate. Because of the non-random allocation of our primary exposure variable, a propensity score (PS) was generated using logistic regression to model the likelihood of preoperative PDE5i use as a function of the following variables: age; sex; race; body mass index (BMI); preoperative use of β-blockers, ACE inhibitors, or IV inotropes; INTERMACS profile; device strategy (bridge to transplant vs destination therapy); preoperative sodium, creatinine, aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, and total bilirubin; presence of severe tricuspid regurgitation; right atrial pressure (RAP); pulmonary artery systolic pressure (PASP); pulmonary artery diastolic pressure (PADP); mean pulmonary artery pressure (mPAP); pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (PCWP); mean arterial pressure (MAP); and cardiac index (CI). Missing values were imputed with sequential regression methods using the IVEWare software (Ann Arbor, MI). Among all variables included in the PS model, the most frequently missing variable was PCWP, missing in 30% of cases. The remaining hemodynamic variables were each missing in fewer than 12% of cases, and all other variables were missing in fewer than 6% of cases. Patients who received preoperative PDE5i were matched 1:1 with patients not receiving preoperative PDE5i based on the logit of the PS, with a caliper width of 0.2 times the standard deviation of the logit of the PS, using nearest-neighbor matching without replacement.17 Between-group balance in matched covariates was assessed by calculating the standardized difference (StD) between groups for each covariate, with a threshold of 10% used to determine matching success.18 Overall survival and major bleeding events were compared using the Kaplan-Meier method with log-rank testing and stratified by matched pairs in our propensity-matched cohort.

Subgroup analyses were performed to investigate potential interactions between preoperative PDE5i use and the development of RHF across cohorts stratified by established markers of pulmonary vascular disease and right ventricular dysfunction. Variables associated with pulmonary vascular disease included PASP, pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR),8 transpulmonary gradient (TPG), and the presence of pre-operative PH as reported on the INTERMACS case report forms. Markers of right ventricular function included RAP,19,20 pulmonary artery pulsatility index (PAPi) (pulmonary artery pulse pressure/RAP),9 severe RV dysfunction by echocardiography,6 severe tricuspid regurgitation (TR),20 and the previously reported RV failure risk score (RVFRS).21 Patients unable to be assigned to a given subgroup due to missing data after propensity matching were excluded from that subgroup.

Data Quality

For subjects with outlier or implausible hemodynamic data points, the following rules were applied. Values of PCWP less than 1 mmHg were reset to equal 1mmHg. If PCWP was greater than PADP, it was reset to equal the PADP. RAP and central venous pressure (CVP) are both reported in the registry. RAP and CVP values less than 1 mmHg and greater than 35 mmHg were reset to 1 mmHg and 35 mmHg, respectively. For subjects who had both CVP and RAP recorded, if one value was implausible, the other value was selected. If CVP and RAP were both reported and within 20% of each other, RAP was selected. If either RAP or CVP was within 2 mmHg of mPAP, the alternative variable was selected. If none of the above conditions existed, the higher of the two values was selected, with a maximum allowed RAP value equal to PADP.

Results

Study Cohort

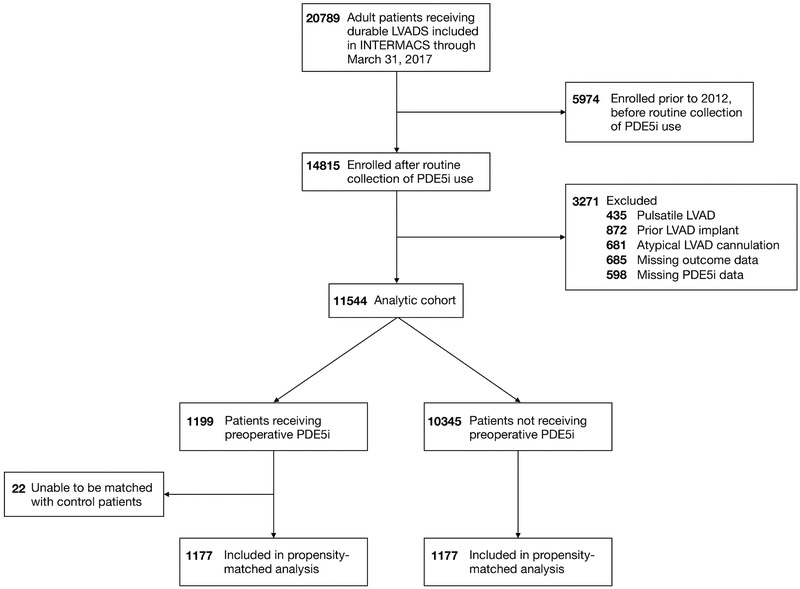

There were 20789 patients enrolled in INTERMACS with a durable LVAD, of which 14815 were enrolled between January 1, 2012 and March 31, 2017. A total of 3,271 patients met exclusion criteria, leaving a final study cohort of 11,544 patients. Of these, 1,199 (10%) were receiving preoperative PDE5i (Figure 1). Baseline characteristics are reported in Table 1. Preoperative PDE5i use was associated with less frequent ACE inhibitor use (19.3% vs 25.0%), more frequent use of preoperative intravenous inotropes (91.5% vs 81.6%) and renal replacement therapy (5.0% vs 1.6%), and more severe INTERMACS profiles compared to controls (p < 0.001 for all, Table 1). PDE5i use was associated with significantly higher PA pressures and mean PVR (2.6 WU vs 2.3 WU, p < 0.001). Severe tricuspid regurgitation was slightly more prevalent in patients receiving preoperative PDE5i (12.0% vs 10.4%, p = 0.049), as was concomitant tricuspid valve surgery (20.6% vs 15.1%, p < 0.001). The propensity-matched cohort included 1177 patients in each group. The StD between cohorts for all matched variables was < 10% (Table 1).

Figure 1: Derivation of the analytic cohort from the Interagency Registry for Mechanically Assisted Circulatory Support.

INTERMACS, Interagency Registry for Mechanically Assisted Circulatory Support; LVAD, left ventricular assist device; PDE5i, phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitor; RVAD, right ventricular assist device.

Table 1:

Baseline patient characteristics stratified by phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitor (PDE5i) use before and after propensity matching.

| Total | Unmatched | Propensity Matched | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=11544 | PDE5i N=1199 |

No PDE5i N=10345 |

p | PDE5i N=1177 |

No PDE5i N=1177 |

StD (%)* |

|

| Age | 57.1 ± 12.9 | 56.4 ± 12.6 | 57.2 ± 12.9 | 0.046 | 56.4 ± 12.6 | 57.3 ± 12.2 | 6.9 |

| Male sex | 9060 (78.5%) | 952 (79.4%) | 8108 (78.4%) | 0.64 | 936 (79.5%) | 940 (79.9%) | 0.8 |

| White | 7743 (67.1%) | 729 (60.8%) | 7014 (67.8%) | <0.001 | 722 (61.3%) | 740 (62.9%) | 3.1 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 28.6 ± 7.2 | 28.7 ± 7.9 | 28.6 ± 7.1 | 0.82 | 28.6 ± 8.0 | 28.6 ± 7.1 | 0.9 |

| Preoperative medical therapy | |||||||

| β-blockers | 5782 (50.1%) | 591 (49.3%) | 5191 (50.2%) | 0.93 | 582 (49.4%) | 578 (49.1%) | 0.7 |

| ACE inhibitors | 2813 (24.4%) | 231 (19.3%) | 2582 (25.0%) | <0.001 | 230 (19.5%) | 192 (16.3%) | 8.4 |

| IV inotropes | 9541 (82.6%) | 1097 (91.5%) | 8444 (81.6%) | <0.001 | 1075 (91.3%) | 1076 (91.4%) | 0.3 |

| INTERMACS profile | <0.001 | 4.5 | |||||

| 1 | 1690 (14.6%) | 157 (13.1%) | 1533 (14.8%) | 151 (12.8%) | 137 (11.6%) | ||

| 2 | 4044 (35.0%) | 461 (38.4%) | 3583 (34.6%) | 448 (38.1%) | 438 (37.2%) | ||

| 3 | 3976 (34.4%) | 451 (37.6%) | 3525 (34.1%) | 448 (38.1%) | 455 (38.7%) | ||

| ≥4 | 1834 (15.9%) | 130 (10.9%) | 1704 (16.5%) | 130 (11.0%) | 147 (12.5%) | ||

| BTT device strategy | 2879 (24.9%) | 334 (27.9%) | 2545 (24.6%) | 0.07 | 333 (28.3%) | 311 (26.4%) | 4.2 |

| Preoperative interventions | |||||||

| intubation | 593 (5.1%) | 47 (3.9%) | 546 (5.3%) | 0.043 | 44 (3.7%) | 45 (3.8%) | 0 |

| ultrafiltration | 73 (0.6%) | 30 (2.5%) | 43 (0.4%) | <0.001 | 14 (1.2%) | 25 (2.1%) | 7.3 |

| dialysis | 152 (1.3%) | 30 (2.5%) | 122 (1.2%) | <0.001 | 21 (1.8%) | 23 (2.1%) | 1.3 |

| Laboratory values | |||||||

| Creatinine | 1.4 ± 0.7 | 1.4 ± 0.8 | 1.4 ± 0.7 | 0.11 | 1.4 ± 0.8 | 1.5 ± 0.8 | 7.5 |

| Total bilirubin | 1.4 ± 1.8 | 1.4 ± 2.0 | 1.3 ± 1.8 | 0.15 | 1.4 ± 2.0 | 1.4 ± 1.8 | 0.8 |

| AST | 54.2 ± 203.3 | 42.4 ± 103.7 | 55.5 ± 211.8 | 0.034 | 42.4 ± 104.5 | 41.4 ± 94.5 | 1.1 |

| ALT | 64.6 ± 208.0 | 47.0 ± 128.5 | 66.7 ± 215.2 | 0.001 | 47.1 ± 129.6 | 46.3 ± 113.7 | 0.8 |

| Sodium | 135.0 ± 4.7 | 134.4 ± 5.1 | 135.1 ± 4.7 | <0.001 | 134.5 ± 5.1 | 134.7 ± 4.7 | 5.3 |

| Severe TR | 1219 (10.6%) | 144 (12.0%) | 1075 (10.4%) | 0.049 | 137 (11.6) | 140 (11.9) | 0.1 |

| Concomitant TV surgery | 1810 (15.7%) | 247 (20.6%) | 1563 (15.1%) | <0.001 | 236 (20.1%) | 246 (20.9%) | 2.1 |

| RV failure risk score (Michigan) | 1.4 ± 2.2 | 1.6 ± 2.2 | 1.4 ± 2.2 | 0.001 | 1.6 ± 2.2 | 1.5 ± 2.3 | 3.3 |

| Hemodynamic data | |||||||

| RAP (mmHg) | 11.6 ± 6.6 | 12.0 ± 6.3 | 11.6 ± 6.6 | 0.07 | 11.9 ± 6.2 | 11.9 ± 6.9 | 0.0 |

| PASP (mmHg) | 49.9 ± 14.7 | 53.4 ± 15.4 | 49.5 ± 14.5 | <0.001 | 53.4 ± 15.4 | 53.6 ± 15.1 | 1.6 |

| Mean PAP (mmHg) | 33.3 ± 10.0 | 35.2 ± 10.1 | 33.0 ± 10.0 | <0.001 | 35.2 ± 10.1 | 35.3 ± 10.1 | 1.3 |

| PADP (mmHg) | 24.9 ± 8.8 | 26.1 ± 8.7 | 24.8 ± 8.8 | <0.001 | 26.1 ± 8.7 | 26.2 ± 8.8 | 0.8 |

| PCWP (mmHg) | 24.6 ± 9.2 | 25.2 ± 9.2 | 24.5 ± 9.2 | 0.014 | 25.1 ± 9.2 | 25.1 ± 9.2 | 0.4 |

| PVR (WU) | 2.3 ± 2.5 | 2.6 ± 2.7 | 2.3 ± 2.5 | <0.001 | 2.6 ± 2.7 | 2.7 ± 2.6 | 0.6 |

| MAP (mmHg) | 78.6 ± 11.1 | 77.9 ± 11.3 | 78.7 ± 11.0 | 0.018 | 78.0 ± 11.3 | 78.0 ± 10.3 | 0.2 |

| Cardiac index (L/min/m2) | 2.3 ± 1.0 | 2.3 ± 1.0 | 2.3 ± 1.0 | 0.20 | 2.3 ± 1.0 | 2.3 ± 1.0 | 1.7 |

ACE, angiotensin converting enzyme; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; BMI, body mass index; BTT, bridge to transplant; IV, intravenous; MAP, mean arterial pressure; PADP, pulmonary artery diastolic pressure; PAP, pulmonary artery pressure; PASP, pulmonary artery systolic pressure; PDE5i, phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitor; PVR, pulmonary vascular resistance; RAP, right atrial pressure; RV, right ventricle; StD, standardized difference; TR, tricuspid regurgitation; TV, tricuspid valve; WU, Wood units.

All p > 0.05.

Outcomes

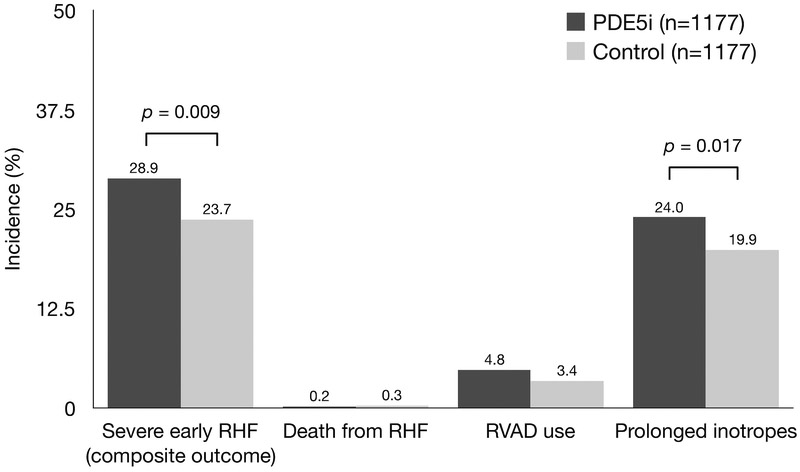

The overall incidence of severe early RHF in the study cohort was 23.7% (n=2737), and this outcome occurred in 29.4% (n=352) of patients receiving preoperative PDE5i compared with 23.1% (n=2385) of patients not receiving PDE5i (unadjusted OR 1.32, 95% CI 1.17–1.50). After propensity matching, severe early RHF remained more common in patients treated with preoperative PDE5i: PDE5i 28.9% vs control 23.7% (adjusted OR 1.31, 95% CI 1.09–1.57) (Figure 2). This difference was driven primarily by an increased frequency of prolonged inotropic support among PDE5i patients (24.0% vs 19.9%), while the proportion of patients requiring RVAD support or experiencing early death due to RHF or MSOF was similar between groups (Figure 2). We performed sensitivity analyses of the association between preoperative PDE5i and the primary outcome by performing logistic regression with a model including the propensity score and a model including variables used to calculate the propensity score, both of which yielded results similar to the primary propensity-matched analysis (adjusted OR 1.33 and 1.30, respectively).

Figure 2: Incidence of severe early right heart failure in patients treated with preoperative phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors vs controls.

PDE5i, phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitor; RHF, right heart failure; RVAD, right ventricular assist device.

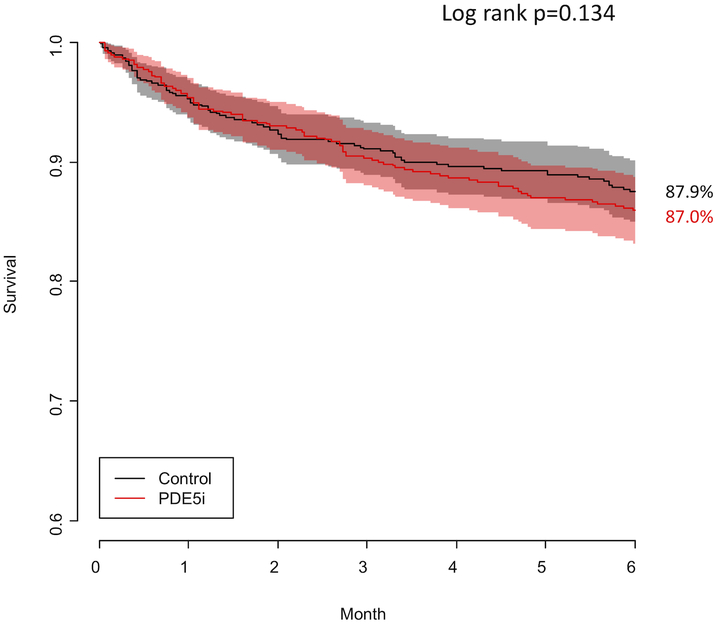

Among patients who required RVAD support, median time to RVAD implant was similar between patients receiving preoperative PDE5i (median 0 days, IQR 0–1 days) and controls (median 0 days, IQR 0–1 days, p = 0.56). Overall survival at 6 months was similar between groups (87.0% vs 87.9%, log-rank p = 0.13) (Figure 3). Median total hospital LOS was three days longer in the PDE5i group than in controls (21 days vs 18 days, p < 0.001). While median ICU LOS was identical between groups, the distribution of ICU LOS in patients receiving preoperative PDE5i was shifted towards longer ICU stays relative to control patients (Table 2). The median 6MWD and quality of life scores at 3 and 6 months post-implant were similar between groups.

Figure 3: Kaplan-Meier 6-month survival curves for patients receiving preoperative phosphodiesterase inhibitors (red line) and controls (black line).

PDE5i, phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitor.

Table 2:

Secondary outcomes among patients receiving preoperative PDE5i and controls.

| Total N=2354 |

PDE5i N=1177 |

Control N=1177 |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Post-implant inotrope duration | 0.010 | |||

| < 1 week | 922 (39.2%) | 422 (35.8%) | 500 (42.5%) | |

| 1–2 weeks | 815 (34.6%) | 416 (35.3%) | 399 (33.9%) | |

| 2–4 weeks | 314 (13.3%) | 168 (14.3%) | 146 (12.4%) | |

| > 4 weeks | 99 (4.2%) | 51 (4.3%) | 48 (4.0%) | |

| Ongoing at discharge | 106 (4.5%) | 64 (5.4%) | 42 (3.6%) | |

| Post-implant ICU LOS (days) | 7.0 (5.0, 12.0) | 7.0 (5.0, 14.0) | 7.0 (4.0, 12.0) | <0.001 |

| Post-implant hospital LOS (days) | 18 (15, 27) | 21 (15, 30) | 18 (15, 27) | 0.001 |

| 6-minute walk distance (3 months) (m) | 329.2 (61.0,390.1) | 322.8 (61.0,389.8) | 335.9 (256.0,391.4) | 0.38 |

| 6-minute walk distance (6 months) (m) | 345.9 (274.3,408.4) | 350.5 (274.3,417.0) | 337.7 (274.3,401.6) | 0.20 |

| Quality of life (3 months) | 62.5 (37.5,75.0) | 62.5 (37.5,75.0) | 62.5 (37.5,75.0) | 0.96 |

| Quality of life (6 months) | 62.5 (50.0,75.0) | 62.5 (37.5,75.0) | 62.5 (50.0,75.0) | 0.47 |

Data presented as N (%) or median (IQR). ICU, intensive care unit; LOS, length of stay.

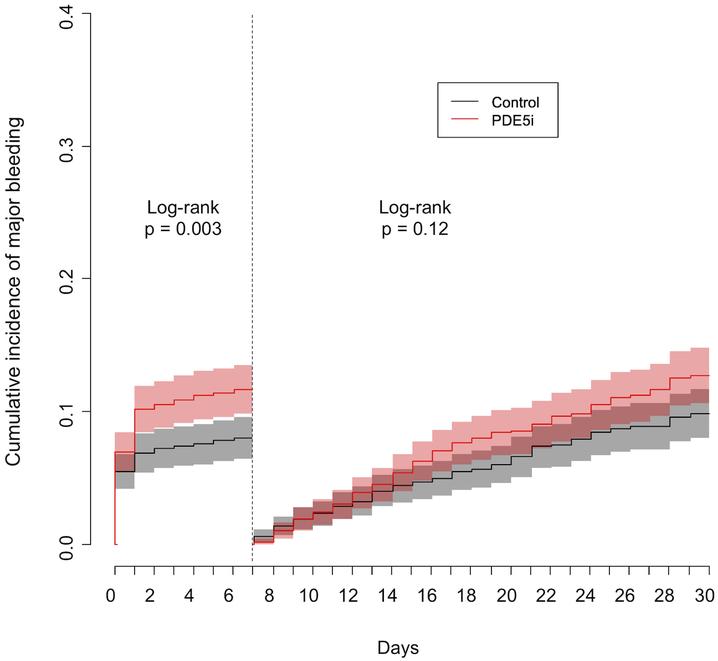

The cumulative incidence of major bleeding events at 1 month was higher in the PDE5i group compared to controls (24.5% vs 17.9%, HR 1.20, 95% CI 1.06–1.36). Because the increased bleeding risk appeared concentrated in the immediate postoperative period, we performed a landmark analysis at 7 days to assess bleeding risk in the first postoperative week and the remaining 3 weeks separately (Figure 4). The cumulative incidence of major bleeding at 7 days was significantly higher among patients receiving preoperative PDE5i than among controls (11.7% vs 8.0%, HR 1.52, 95% CI 1.15–2.00). Among patients who did not experience a major bleeding event within the first 7 days, the risk of major bleeding was not significantly different between groups at 30 days (12.8% vs 9.9%, HR 1.12, 95% CI 0.97–1.30).

Figure 4: Cumulative incidence of major bleeding events at 30 days in patients receiving preoperative phosphodiesterase inhibitors (red line) and controls (black line).

A landmark analysis was performed at 7 days. PDE5i, phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitor.

Subgroup analyses

Across multiple subgroups based on parameters associated with pulmonary vascular disease or right heart function, preoperative PDE5i use remained consistently associated with a higher incidence of severe early RHF, with frequencies similar to that observed in the overall cohort (Figure 5). The sole exception was in subgroups defined by tertiles of PASP, in which patients in the middle tertile of PASP on preoperative PDE5i had a significantly higher frequency of early severe RHF (p = 0.024 for interaction). Because values of RAP and PCWP were modified to account for implausible hemodynamic data, a sensitivity analysis was performed excluding any patient with adjusted data, and findings were similar to the primary analysis (data not shown).

Figure 5: Forest plot comparing the incidence of severe early right heart failure in various subgroups of patients receiving phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitors compared to controls.

HTN, hypertension; PAPi, pulmonary artery pulsatility index; PASP, pulmonary artery systolic pressure; PDE5i, phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitor; RAP, right atrial pressure; RHF, right heart failure; RV, right ventricle; RVFRS, right ventricular failure risk score (as described in ref. 21); TPG, transpulmonary gradient; TR, tricuspid regurgitation; WU, Wood units.

Discussion

This is the largest study to date investigating the use of PDE5i in patients with advanced heart failure. In a large, contemporary, multicenter cohort of LVAD recipients, we found that approximately 10% were treated with PDE5i prior to surgery, an off-label indication for this pharmacotherapy. Furthermore, we found that preoperative PDE5i use was associated with a higher incidence of prolonged inotropic support after LVAD implantation, resulting in an increased incidence of severe early RHF. This increased rate of severe early RHF persisted despite propensity matching to account for differences in baseline characteristics associated with PDE5i use, many of which track with overall severity of illness. We were unable to identify a signal of benefit across multiple patient subgroups defined by parameters associated with either pulmonary vascular disease or right heart dysfunction.

The prevalence of pulmonary hypertension approaches 70% among patients with left heart failure.13 Multiple studies have evaluated the therapeutic efficacy of different classes of PVD therapy in this patient population. In smaller heart failure studies, PDE5i therapy has resulted in favorable hemodynamic changes, including decreased PVR, increased CI, and increased RV ejection fraction,22-24 and has been associated with improvements in exercise capacity and ventilatory efficiency.25,26 When initiated in patients with persistent pulmonary hypertension following LVAD implantation, PDE5i therapy has also been shown to reduce PVR and increase RV contractility.27 However, randomized studies have failed to show a clinical benefit of PVD therapies in left heart failure, and there have been some signals of potential harm.28-31 For example, in a recent placebo-controlled study of patients with pulmonary hypertension due to left-sided valvular heart disease that persisted despite valve surgery, patients randomized to receive sildenafil were more likely to have a worsening composite clinical score.31 Given the lack of robust data to support the use of PVD therapy in patients with pulmonary hypertension due to left heart disease, current guidelines caution against using PVD therapy in this population.32

While the INTERMACS registry does not document the specific indication for preoperative PDE5i therapy, the higher pulmonary artery pressures and PVR noted among patients receiving PDE5i suggest that these agents were prescribed to reduce RV afterload prior to LVAD implantation. Elevated RV afterload has been associated with post-LVAD RHF,8,10 which occurs in up to 40% of patients and is one of the strongest predictors of early postoperative morbidity and mortality.3,4,6,20 There are limited data to suggest that PVD administration can reduce the risk of early RHF following LVAD implantation. In a retrospective analysis of 14 LVAD recipients with preoperative pulmonary hypertension and RV dysfunction, Hamdan et al. reported that all 8 patients receiving perioperative sildenafil (6 of whom received it preoperatively) remained free of RHF, while 4 of 6 patients not receiving perioperative sildenafil developed RHF.15 A multicenter, randomized study of perioperative inhaled nitric oxide in 150 CF-LVAD patients with elevated PVR (> 2.5 WU) similarly demonstrated a strong but non-significant trend towards a reduction in early RHF events, including lower rates of early RVAD implantation.16

Contrary to these data, our findings suggest that PDE5i therapy does not have a robust effect on mitigating the risk of early RHF in patients undergoing LVAD surgery. We cannot completely exclude residual confounding leading to an inherently higher pre-implant risk of RHF among patients in the PDE5i cohort, but our findings are generally consistent with other studies that have failed to identify a benefit of PDE5i in left heart failure.30,31 Acknowledging the known limitations of post-hoc analyses, our data suggest that preoperative PDE5i therapy could even be harmful, given the higher proportion of early RHF events and increased incidence of major bleeding observed in patients who received this treatment.

The primary beneficial impact of preoperative PDE5i would be to decrease RV afterload, so the benefit might be greatest in patients with the highest degree of RV afterload. However, we did not observe any signal of benefit for preoperative PDE5i therapy among patients stratified by various markers of pulmonary hypertension, including PASP, TPG, or PVR. There is also some evidence to suggest a modest RV inotropic effect from PDE5i.33 As such, patients with manifest right heart dysfunction might stand to benefit more from PDE5i therapy. However, we were not able to identify any signal of benefit among patients across a variety of hemodynamic or echocardiographic markers of right heart dysfunction (Figure 5).

While this study cannot shed light on the mechanisms by which PDE5i might contribute to increased postoperative RHF, there are theoretical risks of PDE5i therapy that may be important. PDE5i have been shown to inhibit platelet activation by enhancing nitric oxide signaling within platelets.34,35 Importantly, among patients receiving preoperative PDE5i, we observed a higher risk of major bleeding over the first month after LVAD implantation that was concentrated in the immediate postoperative period (Figure 4). Unfortunately, blood transfusions are not recorded in INTERMACS, so we were unable to quantify postoperative blood product use in our cohort. These findings raise concern about the use of PDE5i in LVAD recipients, particularly in the immediate perioperative period when there is a high risk of bleeding complications and where blood transfusions could exacerbate RV dysfunction via volume loading.36

Although PDE5i are partially selective for the pulmonary vasculature, they can also induce systemic vasodilation.22,37 PDE5i treatment could therefore increase the risk of postoperative hypotension and vasoplegia secondary to augmentation of endogenous cyclic GMP-mediated nitric oxide signaling.38 Vasoplegia and hypotension can induce acute worsening of right heart function and may be associated with prolonged need for vasopressors and inotropic support. PDE5i therapy may also lead to a rise in PCWP from increased pulmonary blood flow directed towards a dilated, non-compliant left heart.39 While this risk should typically be mitigated in patients with mechanical unloading of the left heart, left-sided decongestion after LVAD implantation may be incomplete,40 particularly in patients with right heart dysfunction where there is a tendency in some centers to maintain lower LVAD speeds in the early postoperative period. We were unable to evaluate these possible mechanisms with the data available.

When considering risk factors for RHF, RV afterload cannot be considered in isolation. It is clear that the relationship between RV function and afterload (RV-PA coupling) plays an important role in the development of postoperative RHF,9,10 and multiple potential factors can contribute to hemodynamic uncoupling of the RV from the pulmonary circulation.36 In the setting of severe, chronic RV dysfunction, a vulnerable RV with reduced contractile reserve may be more susceptible to acute hemodynamic insults that may occur during cardiac surgery. These insults can include right heart volume loading from transfusion and increased blood return from improved left-sided cardiac output; increased RV afterload from lung injury, acidosis, and hypoxia; and RV contractile dysfunction induced by the initiation of left-sided mechanical support.36,41 PDE5i therapy would only be expected to impact a subset of these factors, potentially limiting its ability to substantially reduce early RHF events.

Limitations

The present data are limited by their retrospective nature, and causality between PDE5i use and the occurrence of severe early RHF cannot be assumed. Despite utilizing robust statistical adjustment via propensity matching, residual confounding almost certainly exists, as it is not possible to adjust for unmeasured variables. Despite propensity matching, a few characteristics remained unbalanced. There were differences in preoperative 6MWD between subjects receiving PDE5i compared to controls (268 m vs 235 m, StD 25.7%) and duration of LVAD surgery (278 min vs 299 min, StD 19.7%). However, higher baseline 6MWD would suggest that patients in the PDE5i group may have actually been less sick prior to surgery, and shorter average surgical duration should be less likely to induce postoperative RHF,6 both of which would tend to bias the results in favor of PDE5i.

Another limitation is the inability to determine the timing of baseline hemodynamic reporting in relation to both initiation of PDE5i therapy and LVAD implantation. We do not know whether patients were receiving PDE5i therapy at the time of right heart catheterization and therefore, cannot assess the impact of PDE5i on PVR or PCWP. Prior to propensity matching, patients treated with PDE5i had evidence of higher overall illness severity compared to those not receiving this therapy. It remains possible that the differences seen between groups may have been more exaggerated in the absence of PDE5i administration, and that the similar outcomes observed across multiple end-points actually represents a relative protective benefit of PDE5i administration.

Additionally, we were unable to determine whether PDE5i therapy was continued in the 30 days following LVAD implant or newly initiated during this period in patients not receiving it preoperatively. We were also unable to determine whether patients receiving preoperative PDE5i therapy were concentrated at a few institutions, which, if true, would bias our results if these same institutions were also more likely to use prolonged inotrope therapy after LVAD implantation. Finally, our results should not be extrapolated to inhaled pulmonary vasodilator therapies like nitric oxide or inhaled prostaglandins, which may have different effects on the incidence of postoperative right heart failure.

Conclusions

Off-label PDE5i therapy is commonly used in advanced heart failure patients undergoing LVAD surgery, but our data do not support the routine preoperative use of these agents for the prevention of severe early RHF. Despite adjustment for baseline risk factors, preoperative administration of PDE5i was associated with a higher rate of post-LVAD RHF events, predominantly related to prolonged inotropic support. A prospective study is needed to determine if there is a role for preoperative PDE5i therapy to mitigate early RHF among patients undergoing LVAD implantation.

What is new?

Approximately 10% of patients in the INTERMACS registry were receiving PDE5i therapy at the time of LVAD implantation.

Preoperative PDE5i therapy was associated with a significantly higher incidence of severe early right heart failure in a propensity-matched analysis.

Preoperative PDE5i use was associated with significantly higher cumulative incidence of major bleeding within one month after LVAD implantation, predominantly concentrated in the early postoperative period.

What are the clinical implications?

This study does not support the routine use of preoperative PDE5i therapy to prevent severe early right heart failure in LVAD recipients.

Our finding that preoperative PDE5i therapy was associated with a higher incidence of major bleeding after LVAD implantation warrants further study.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding: Dr. Gulati was supported in part by NIH grant 1TL1TR002546–01.

Footnotes

Disclosures:

J E Rame: consulting for Actelion Pharmaceuticals (modest), SOPRANO study steering committee member

R L Kormos: consulting for Medtronic (modest), travel support from Medtronic (modest)

J Teuteberg: consulting from Medtronic (modest), Abiomed (modest), and CareDX (modest)

M S Kiernan: consulting from Medtronic (modest), travel support from Abbott (modest)

The remaining authors report no relevant financial conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Argiriou M, Kolokotron S-M, Sakellaridis T, Argiriou O, Charitos C, Zarogoulidis P, Katsikogiannis N, Kougioumtzi I, Machairiotis N, Tsiouda T, Tsakiridis K, Zarogoulidis K. Right heart failure post left ventricular assist device implantation. J Thorac Dis. 2014;6 Suppl 1:S52–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rogers JG, Pagani FD, Tatooles AJ, Bhat G, Slaughter MS, Birks EJ, Boyce SW, Najjar SS, Jeevanandam V, Anderson AS, Gregoric ID, Mallidi H, Leadley K, Aaronson KD, Frazier OH, Milano CA. Intrapericardial Left Ventricular Assist Device for Advanced Heart Failure. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:451–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mehra MR, Naka Y, Uriel N, Goldstein DJ, Cleveland JC, Colombo PC, Walsh MN, Milano CA, Patel CB, Jorde UP, Pagani FD, Aaronson KD, Dean DA, McCants K, Itoh A, Ewald GA, Horstmanshof D, Long JW, Salerno C. A Fully Magnetically Levitated Circulatory Pump for Advanced Heart Failure. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:440–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kormos RL, Teuteberg JJ, Pagani FD, Russell SD, John R, Miller LW, Massey T, Milano CA, Moazami N, Sundareswaran KS, Farrar DJ. Right ventricular failure in patients with the HeartMate II continuous-flow left ventricular assist device: Incidence, risk factors, and effect on outcomes. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;139:1316–1324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kirklin JK, Naftel DC, Pagani FD, Kormos RL, Stevenson LW, Blume ED, Myers SL, Miller MA, Baldwin JT, Young JB. Seventh INTERMACS annual report: 15,000 patients and counting. J Hear Lung Transplant. 2015;34:1495–1504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Soliman OII, Akin S, Muslem R, Boersma E, Manintveld OC, Krabatsch T, Gummert JF, de By TMMH, Bogers AJJC, Zijlstra F, Mohacsi P, Caliskan K, EUROMACS Investigators. Derivation and Validation of a Novel Right-Sided Heart Failure Model After Implantation of Continuous Flow Left Ventricular Assist Devices: The EUROMACS (European Registry for Patients with Mechanical Circulatory Support) Right-Sided Heart Failure Risk Sc. Circulation. 2018;137:891–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Colucci WS, Holman BL, Wynne J, Carabello B, Malacoff R, Grossman W, Braunwald E. Improved right ventricular function and reduced pulmonary vascular resistance during prazosin therapy of congestive heart failure. Am J Med. 1981;71:75–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Drakos SG, Janicki L, Horne BD, Kfoury AG, Reid BB, Clayson S, Horton K, Haddad F, Li DY, Renlund DG, Fisher PW. Risk Factors Predictive of Right Ventricular Failure After Left Ventricular Assist Device Implantation. Am J Cardiol. 2010;105:1030–1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morine KJ, Kiernan MS, Pham DT, Paruchuri V, Denofrio D, Kapur NK. Pulmonary Artery Pulsatility Index is Associated with Right Ventricular Failure after Left Ventricular Assist Device Surgery. J Card Fail. 2016;22:110–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grandin EW, Zamani P, Mazurek JA, Troutman GS, Birati EY, Vorovich E, Chirinos JA, Tedford RJ, Margulies KB, Atluri P, Rame JE. Right ventricular response to pulsatile load is associated with early right heart failure and mortality after left ventricular assist device. J Hear Lung Transplant. 2017;36:97–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Groote P, El Asri C, Fertin M, Goéminne C, Vincentelli A, Robin E, Duva-Pentiah A, Lamblin N. Sildenafil in heart transplant candidates with pulmonary hypertension. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 2015;108:375–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khazanie P, Hammill BG, Patel CB, Kiernan MS, Cooper LB, Arnold SV, Fendler TJ, Spertus JA, Curtis LH, Hernandez AF. Use of Heart Failure Medical Therapies Among Patients With Left Ventricular Assist Devices: Insights From INTERMACS. J Card Fail. 2016;22:672–679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vachiéry J-L, Adir Y, Barberà JA, Champion H, Coghlan JG, Cottin V, De Marco T, Galiè N, Ghio S, Gibbs JSR, Martinez F, Semigran M, Simonneau G, Wells A, Seeger W. Pulmonary hypertension due to left heart diseases. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:D100–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sparrow CT, LaRue SJ, Schilling JD. Intersection of Pulmonary Hypertension and Right Ventricular Dysfunction in Patients on Left Ventricular Assist Device Support. Circ Hear Fail. 2018;11:e004255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hamdan R, Mansour H, Nassar P, Saab M. Prevention of Right Heart Failure After Left Ventricular Assist Device Implantation by Phosphodiesterase 5 Inhibitor. Artif Organs. 2014;38:963–967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Potapov E, Meyer D, Swaminathan M, Ramsay M, El Banayosy A, Diehl C, Veynovich B, Gregoric ID, Kukucka M, Gromann TW, Marczin N, Chittuluru K, Baldassarre JS, Zucker MJ, Hetzer R. Inhaled nitric oxide after left ventricular assist device implantation: A prospective, randomized, double-blind, multicenter, placebo-controlled trial. J Hear Lung Transplant. 2011;30:870–878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Austin PC. Optimal caliper widths for propensity-score matching when estimating differences in means and differences in proportions in observational studies. Pharm Stat. 2011;10:150–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Austin PC. Balance diagnostics for comparing the distribution of baseline covariates between treatment groups in propensity-score matched samples. Stat Med. 2009;28:3083–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Raina A, Seetha Rammohan HR, Gertz ZM, Rame JE, Woo YJ, Kirkpatrick JN. Postoperative right ventricular failure after left ventricular assist device placement is predicted by preoperative echocardiographic structural, hemodynamic, and functional parameters. J Card Fail. 2013;19:16–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kiernan MS, Grandin EW, Brinkley M, Kapur NK, Pham DT, Ruthazer R, Rame JE, Atluri P, Birati EY, Oliveira GH, Pagani FD, Kirklin JK, Naftel D, Kormos RL, Teuteberg JJ, DeNofrio D. Early Right Ventricular Assist Device Use in Patients Undergoing Continuous-Flow Left Ventricular Assist Device Implantation: Incidence and Risk Factors From the Interagency Registry for Mechanically Assisted Circulatory Support. Circ Heart Fail. 2017;10:e003863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matthews JC, Koelling TM, Pagani FD, Aaronson KD. The Right Ventricular Failure Risk Score. A Pre-Operative Tool for Assessing the Risk of Right Ventricular Failure in Left Ventricular Assist Device Candidates. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:2163–2172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alaeddini J, Uber PA, Park MH, Scott RL, Ventura HO, Mehra MR. Efficacy and safety of sildenafil in the evaluation of pulmonary hypertension in severe heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 2004;94:1475–1477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Melenovsky V, Al-Hiti H, Kazdova L, Jabor A, Syrovatka P, Malek I, Kettner J, Kautzner J. Transpulmonary B-Type Natriuretic Peptide Uptake and Cyclic Guanosine Monophosphate Release in Heart Failure and Pulmonary Hypertension. The Effects of Sildenafil. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:595–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guazzi M, Vicenzi M, Arena R, Guazzi MD. Pulmonary hypertension in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: A target of phosphodiesterase-5 inhibition in a 1-year study. Circulation. 2011;124:164–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lewis GD, Shah R, Shahzad K, Camuso JM, Pappagianopoulos PP, Hung J, Tawakol A, Gerszten RE, Systrom DM, Bloch KD, Semigran MJ. Sildenafil improves exercise capacity and quality of life in patients with systolic heart failure and secondary pulmonary hypertension. Circulation. 2007;116:1555–1562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lewis GD, Lachmann J, Camuso J, Lepore JJ, Shin J, Martinovic ME, Systrom DM, Bloch KD, Semigran MJ. Sildenafil improves exercise hemodynamics and oxygen uptake in patients with systolic heart failure. Circulation. 2007;115:59–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tedford RJ, Hemnes AR, Russell SD, Wittstein IS, Mahmud M, Zaiman AL, Mathai SC, Thiemann DR, Hassoun PM, Girgis RE, Orens JB, Shah AS, Yuh D, Conte JV,Champion HC. PDE5A inhibitor treatment of persistent pulmonary hypertension after mechanical circulatory support. Circ Heart Fail. 2008;1:213–219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Califf RM, Adams KF, McKenna WJ, Gheorghiade M, Uretsky BF, McNulty SE, Darius H, Schulman K, Zannad F, Handberg-Thurmond E, Harrell J, Wheeler W, Soler-Soler J, Swedberg K. A randomized controlled trial of epoprostenol therapy for severe congestive heart failure: The Flolan International Randomized Survival Trial (FIRST). Am Heart J. 1997;134:44–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Packer M, McMurray J, Massie BM, Caspi A, Charlon V, Cohen-Solal A, Kiowski W, Kostuk W, Krum H, Levine B, Rizzon P, Soler J, Swedberg K, Anderson S, Demets DL. Clinical effects of endothelin receptor antagonism with bosentan in patients with severe chronic heart failure: Results of a pilot study. J Card Fail. 2005;11:12–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Redfield MM, Chen HH, Borlaug BA, Semigran MJ, Lee KL, Lewis G, LeWinter MM, Rouleau JL, Bull DA, Mann DL, Deswal A, Stevenson LW, Givertz Elizabeth O Ofili MM, O’Connor CM, Felker GM, Goldsmith SR, Bart BA, McNulty SE, Ibarra JC, Lin G, Oh JK, Patel MR, Kim RJ, Tracy RP, Velazquez EJ, Anstrom KJ, Hernandez AF, Mascette AM, Braunwald E. Effect of phosphodiesterase-5 inhibition on exercise capacity and clinical status in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA - J Am Med Assoc. 2013;309:1268–1277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bermejo J, Yotti R, García-Orta R, Sánchez-Fernández PL, Castaño M, Segovia-Cubero J, Escribano-Subías P, San Román JA, Borrás X, Alonso-Gómez A, Botas J, Crespo-Leiro MG, Velasco S, Bayés-Genís A, López A, Muñoz-Aguilera R, de Teresa E, González-Juanatey JR, Evangelista A, Mombiela T, González-Mansilla A, Elízaga J, Martín-Moreiras J, González-Santos JM, Moreno-Escobar E, Fernández-Avilés F, Sildenafil for Improving Outcomes after VAlvular Correction (SIOVAC) investigators. Sildenafil for improving outcomes in patients with corrected valvular heart disease and persistent pulmonary hypertension: a multicenter, double-blind, randomized clinical trial. Eur Heart J. 2018;39:1255–1264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Galiè N, Humbert M, Vachiery J-L, Gibbs S, Lang I, Torbicki A, Simonneau G, Peacock A, Vonk Noordegraaf A, Beghetti M, Ghofrani A, Gomez Sanchez MA, Hansmann G, Klepetko W, Lancellotti P, Matucci M, McDonagh T, Pierard LA, Trindade PT, Zompatori M, Hoeper M. 2015 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension. Eur Heart J. 2016;37:67–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nagendran J, Archer SL, Soliman D, Gurtu V, Moudgil R, Haromy A, Aubin C, Webster L, Rebeyka IM, Ross DB, Light PE, Dyck JRB, Michelakis ED. Phosphodiesterase type 5 is highly expressed in the hypertrophied human right ventricle, and acute inhibition of phosphodiesterase type 5 improves contractility. Circulation. 2007;116:238–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Halcox JPJ, Nour KRA, Zalos G, Mincemoyer R, Waclawiw MA, Rivera CE, Willie G, Ellahham S, Quyyumi AA. The effect of sildenafil on human vascular function, platelet activation, and myocardial ischemia. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;40:1232–1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gudmundsdóttir IJ, McRobbie SJ, Robinson SD, Newby DE, Megson IL. Sildenafil potentiates nitric oxide mediated inhibition of human platelet aggregation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;337:382–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Houston BA, Shah KB, Mehra MR, Tedford RJ. A new “twist” on right heart failure with left ventricular assist systems. J Hear Lung Transplant. 2017;36:701–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Klodell CT, Morey TE, Lobato EB, Aranda JM, Staples ED, Schofield RS, Hess PJ, Martin TD, Beaver TM. Effect of Sildenafil on Pulmonary Artery Pressure, Systemic Pressure, and Nitric Oxide Utilization in Patients With Left Ventricular Assist Devices. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;83:68–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shaefi S, Mittel A, Klick J, Evans A, Ivascu NS, Gutsche J, Augoustides JGT. Vasoplegia After Cardiovascular Procedures-Pathophysiology and Targeted Therapy. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2018;32:1013–1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Loh E, Stamler JS, Hare JM, Loscalzo J, Colucci WS. Cardiovascular effects of inhaled nitric oxide in patients with left ventricular dysfunction. Circulation. 1994;90:2780–2785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Imamura T, Chung B, Nguyen A, Sayer G, Uriel N. Clinical implications of hemodynamic assessment during left ventricular assist device therapy. J Cardiol. 2018;71:352–358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Park CH, Nishimura K, Kitano M, Matsuda K, Okamoto Y, Ban T. Analysis of right ventricular function during bypass of the left side of the heart by afterload alterations in both normal and failing hearts. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1996;111:1092–1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]