Abstract

Ovarian aging is related to the reduction of oocyte quality and ovarian follicles reservation leading to infertility. Vitamin C is a natural antioxidant which may counteract with adverse effects of aging in the ovary. The aim of this study was to evaluate the possible effect of vitamin C on NMRI mice ovarian aging according to the stereological study. In this experimental study, 36 adult female mice (25–30 g) were divided into two groups: control and vitamin C. Vitamin C (150 mg/kg/day) were administered by oral gavage for 33 weeks. Six animals of each group were sacrificed on week 8, 12, and 33, and right ovary samples were extracted for stereology analysis. Our data showed that the total volume of ovary, cortex, medulla and corpus luteum were significantly increased in vitamin C group in comparison to the control groups (P≤0.05). In addition, the total number of primordial, primary, secondary, and antral follicles as well as granulosa cells were improved in vitamin C group in compared to the control groups (P≤0.05). No significant difference was observed in total volume of oocytes in antral follicles between control and vitamin C groups. Our data showed that vitamin C could notably compensate undesirable effects of ovarian aging in a mouse model.

Keywords: Aging, Follicular reserve, Ovary, Vitamin C

Introduction

Aging is a set of changes that happen over time in the body. It is primarily affected by sexual and reproductive hormones and is the most important risk factor for several diseases [1,2]. As the age increases, the ability of women for childbearing decreases. The importance of this issue is determined by the fact that the age of childbearing has been postponed to the fourth decade of life in the modern societies [3,4]. As a result of declined fertility, such women will have more need to assisted reproductive techniques (ART) to have children [5]. ART, in turn, has high cost and more complications in advanced maternal age which is undesired [6,7].

Ovarian aging is characterized by declined ovarian reserve [8,9], low oocyte quality [10], diminished anti-Müllerian hormone [11,12], and finally menopause [3]. Ovaries are more susceptible to the complications of natural aging than other tissues for some of the known and unclear reasons [13]. Oxidative stress is one of the disturbing mechanisms involving in aged ovary. During ovarian aging, decreased antioxidant gene expression and increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) resulted in more oxidative damage [14,15]. Carbonyl stress due to dysregulation of energetic metabolism in the aging follicles is another distressing mechanism [16,17]. It is reported that mitochondrial dysfunction also has a role in ovarian damages in aging [6]. Oxidative stress, carbonyl stress, and mitochondrial dysfunction are related together and affect each other [6,16].

Application of free radicals scavengers can protect ovary from the damage of oxidative stress [18,19,20]. Vitamin C (L-ascorbic acid) is a natural antioxidant scavenging ROS effectively [21,22]. In addition, useful effects of vitamin C on metabolism, collagen synthesis, vasculogenesis, aging, cell proliferation, and differentiation has been reported previously [21,22,23,24]. Although, so far, several studies have investigated the role of vitamin C in combination with other antioxidants on female infertility [5,19,25], there are scarcely data regarding to the effect of vitamin C alone on ovarian aging. In the present study, we aimed to evaluate the effects of vitamin C on NMRI mice ovarian aging according to the stereological study.

Materials and Methods

Animals and treatments

In this experimental study, 36 adult female NMRI mice weight of 25–30 g were obtained from Iran Pasteur Institute. The animals were kept in animal house under standard conditions (22±2℃ and 12-hour light/dark) and provided with food and water ad libitum. The mice were then divided into two groups: control and experimental groups. Vitamin C (L-ascorbic acid; Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) was prepared by diluting in warm water. The experimental groups were given vitamin C (150 mg/kg) with a 24-hour interval by oral gavage (3.75 mg per animal) for 33 weeks. Control animals were treated with water. On weeks 8, 12, and 33, six animals of each group and right ovary samples were extracted for stereology analysis.

Tissue preparation

The ovaries were placed in 10% formalin fixative for 48 hours. After tissue processing, the samples were placed in paraffin blocks. Following sectioning, hematoxylin and eosin staining was performed.

Stereological study

Volume of ovary, cortex, medulla, and corpus luteum

The total volume of the ovary, cortex, medulla and corpus luteum was estimated using the Cavalieri methods applying the following formula [17,26]:

| Vtotal=Σp×a/p×t |

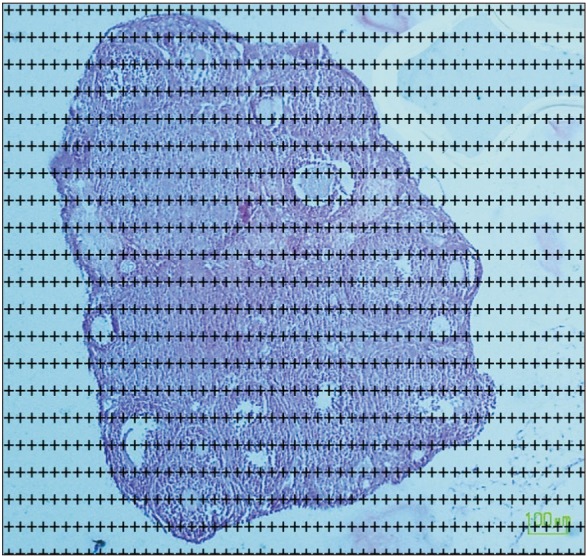

In this formula, Σp is the total number of points superimposed on the image, (t) is the thickness of the section and a/p is the area associated with each point (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Estimating the volume of ovary using the Cavalieri method. The point counting method, randomly superimposed probe on the images (H&E staining).

Total number of primordial, primary, secondary, antral follicles, and granulosa cells

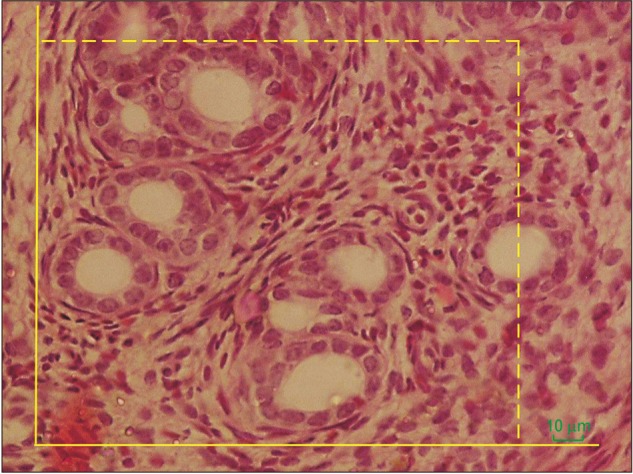

The total number of primordial, primary, secondary, and antral follicles were estimated using the optical dissector method (Fig. 2) [17,26]. The numerical density (Nv) of primordial, primary, secondary, antral follicles and granulosa cells were calculated with the following formula:

Fig. 2. Estimating the number of follicles using the optical dissector method. An unbiased counting frame superimposed on the selected field was used to sample the nucleoli profiles of the oocytes (H&E staining).

| Nv=(ΣQ)/(ΣP×h×a/f)×t/BA |

In this formula, “ΣQ” is the number of the nuclei, “ΣP” is the total number of the unbiased counting frame in all fields, “h” is the height of the dissector, “a/f” is the frame area, “t” is the real section thickness measured in every field using the microcator, and “BA” is the block advance of the microtome which was set at 10 µm. The total number of primordial, primary, secondary, antral follicles and granulosa cells was estimated by multiplying the numerical density (Nv) by the total V.

| Ntotal=Nv×V |

The volume of oocyte

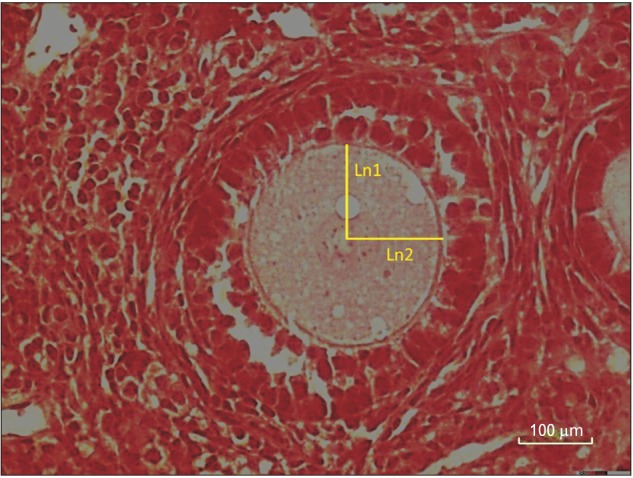

Estimating the mean volumes of oocytes by using the unbiased stereological technique of the nucleator [17,26].

| V=4/3π×Ln3 |

Ln is distance from the center of the nucleolus to the oocyte membrane (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Estimating the mean volumes of oocytes by using the nucleator method. For each sampled oocyte, the distance (intercept, ln) in both directions from the point to the boundary of the nucleus and the oocyte borders is recorded and used for volume estimation (H&E staining).

Statistical analysis

The results were analyzed by Kruskal Wallis test, using the SPSS software version 19.00 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). P≤0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Volume of ovary, cortex, medulla and corpus luteum

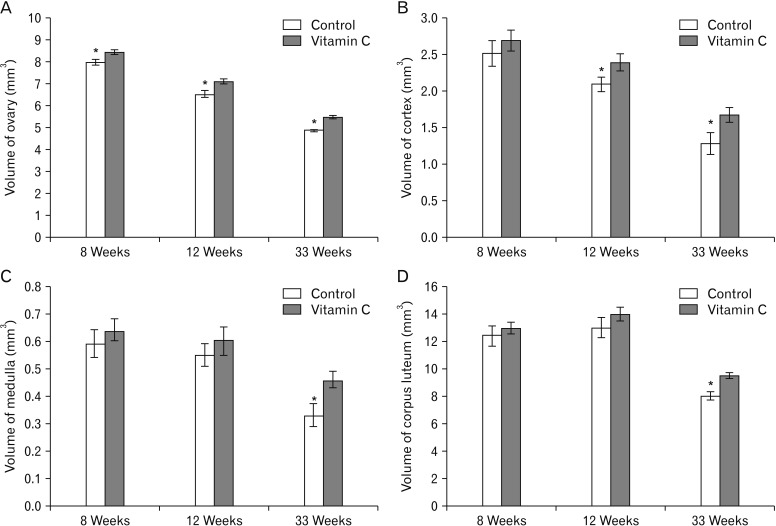

Total volume of ovary at 8, 12, and 33 weeks, total volume of cortex at 12 and 33 weeks and total volume of medulla and corpus luteum at 33 weeks were higher significantly in vitamin C group compared to control group (P≤0.05) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. The total volume of ovary, ovary (A), cortex (B), medulla (C), and corpus luteum (D) in the control and vitamin C groups. *Statistically significant difference (P≤0.05) between groups. Data are shown as mean±SD.

Volume of oocyte and number of granulosa cells

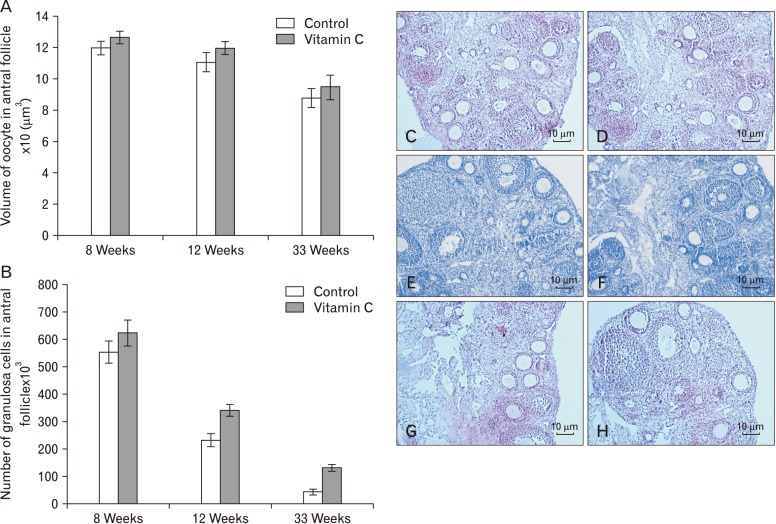

We demonstrated that the mean total volume of oocyte in antral follicles reminded unchanged in the control and vitamin C groups (Fig. 5A). In addition, the total number of granulosa cells increased significantly in vitamin C group as compared to control group at 12 and 33 weeks (P≤0.05) (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5. Comparisons of the mean volume of oocyte (A) and the total number of granulosa cells between groups (B). Data are shown as mean±SD. (C–H) Photomicrograph of the ovaries stained with H&E (×10). (C, D) Control group and vitamin C group (8 weeks). (E, F) Control group and vitamin C group (12 weeks). (G, H) Control group and vitamin C group (33 weeks).

Total number of follicles

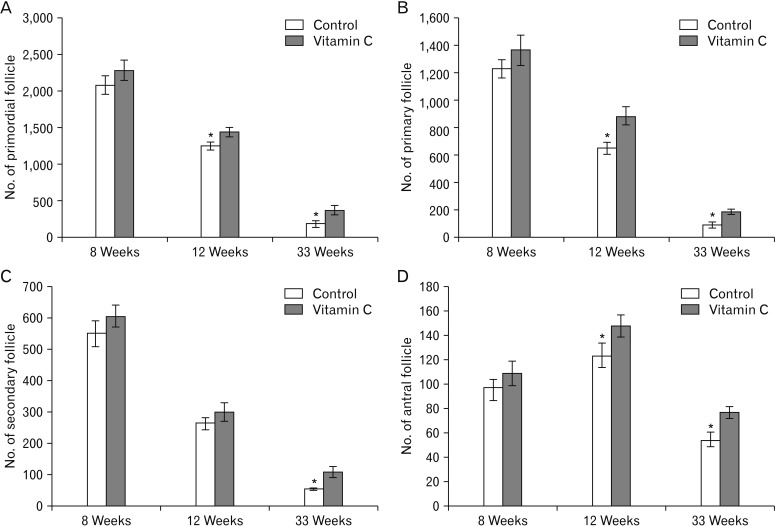

We found a significantly increased the total number of primordial, primary, and antral follicles at 12 and 33 weeks, and also secondary follicle at 33 week in vitamin C group when compared to control group (P≤0.05) (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6. Comparisons of the total number of primordial (A), primary (B), secondary (C), and antral follicles (D) in the control and vitamin C groups. *Statistically significant difference (P≤0.05) between groups. Data are shown as mean±SD.

Discussion

The scope of the current study was to evaluate the possible beneficial or adverse effects of vitamin C on NMRI mice ovarian aging according to the stereological study. We found that vitamin C could significantly prevent the reduction of ovarian volume, number of ovarian follicles and granulosa cells during a mouse model of ovarian aging, although we did not observe any significant difference in total mean oocyte volume between groups. According to our knowledge, this is the first study evaluating the impact of vitamin C alone on ovarian aging based on stereological parameters.

Following ovarian aging, extensive changes occurs at the level of molecules and genes. Some of these changes are down-regulation of germ line specific genes, oocyte specific genes, mitochondrial electron transport genes and intraovarian signaling pathways as well as up-regulation of genes related to complement activation and membrane receptors. Most of these alterations are specific to ovary and don't happen in somatic organs [27,28]. Free radical imbalance is an important part of changes during ovarian aging [29]. Lim and Luderer [15] reported decreased expression of mitochondrial (Prdx3 and Txn2) as well as cytosolic (sGlrx1 and Gstm2) antioxidants genes in ovary with increased age. The main source of free radicals is the oxidative phosphorylation and ATP generation during aerobic metabolism in the mitochondria. Mitochondrial dysfunction is one of causes of increased ROS in aged ovary [16,30]. Considering antioxidant properties of estrogen, its deficiency following menopause is one of other causes of oxidative stress in aging [31].

Antioxidant system in ovary is consist of non-enzymatic antioxidants (vitamins A, C, and E) [32] and enzymatic antioxidants (for example antioxidant tripeptide glutathione, glutathione peroxidase (GPX), superoxide dismutase (SOD), and catalase [33,34,35,36,37]. Based on published studies, ROS scavenging efficiency in ovary decreases during aging including reduced expression and enzymatic activity of SOD in cumulus oophorous cells [38], decreased enzymatic activity of SOD and GPX in postmenopausal women [37] and lower expression of SOD and catalase in cultured granulosa cells collected from old women subjected to in vitro fertilization [36].

In broad terms it seems that decreased antioxidative efficiency on the one hand and increased ROS production on the other hand during aging caused damages in the ovary [29]. Importantly, dysregulation of glucose and energetic metabolism in the aging follicles can produce reactive carbonyl species (RCS) and carbonyl stress. RCS, similar to ROS, contribute to DNA, protein and lipids damages causing deleterious effects in the cells. Carbonyl stress, in turn, strengthens oxidative stress and vice versa. These factors along with mitochondrial dysfunction can cause more age related damages in the ovary [6,16]. It is reported that AKT and mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling pathways are associated with ovarian diseases including ovarian aging [7]. Interestingly, AKT/mTOR signaling is related to oxidative stress and interact on each other [39]. The abnormal perifollicular vascularity also causes abnormal microenvironment in the aged ovary and in turn, may produce oxidative stress [40]. In addition, with increasing the age, the rate of inflammation in the mouse ovaries increases resulting from the function of multinucleated macrophage giant cells and increased expression of inflammatory genes [26].

According to prior published studies, some characteristic of aged ovary are lower follicular quality and quantity [41], increased level of apoptosis and accumulation of lipofuscin pigments in insterstitium [15], fibrosis in the stroma [26], increased DNA fragmentation [42], and chromosomal disturbance [43]. Via stereological analysis, we observed that the total volume of ovary, cortex, medulla and corpus luteum decreased as the age increased (at 8, 12, and 33 weeks) (Fig. 4). Moreover, the total number of follicles, the total mean oocyte volume and number of granulosa cells in antral follicles has declined progressively over time (Figs. 5, 6).

Vitamin C is a natural important water-soluble micronutrient and coenzyme which its deficiency is related to aging of different cells and tissues [44]. It can attenuate vascular dysfunction in several diseases in both in vivo and in vitro studies [22]. Adding vitamin C to culture medium can improve mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) proliferation and metabolism via mitochondrial activation [23]. It is reported that vitamin C can impact on glucose metabolism through alteration of glucose metabolites [24]. Additionally, anti-inflammatory properties of vitamin C on animal models of ischemia and sepsis has been reported previously [22].

Along with the effects of vitamin C on vascularization, metabolism, and inflammation mentioned above, it has also antioxidant effects. In this regard, vitamin C can postpone aging in MSCs via prevention of the ROS production and AKT/mTOR signaling [21]. Arab et al. [20] found that antioxidant effect of ascorbic acid could ameliorate increased oxidative stress induced by malathion in the rats ovary. In the other study, it has been shown that vitamin c amended Bisphenol A oxidative toxicity in rat ovarian tissue. In that study, total volume of ovaries and oocytes, and also the mean number of antral follicles increased following vitamin C administration [18].

Supplementation of culture medium with vitamin C stimulated the activation and growth of cattle primordial follicles and increased viability of early-stage follicles [45]. Tarin et al. [43] reported that early and late onset administration of vitamins C and E caused improving oocyte quality and quantity in aged mice. In the other study, it has been reported that vitamin C supplementation could improve development and viability of preantral follicles after six days of in vitro culture [40]. In accordance with that studies, we evaluated effects of vitamin C administration on ovarian aging and found that vitamin C enhances the survival of the total number of follicles in different stages. It also could prevent the reduction of the volume of ovary and corpus luteum as well as the number of granulosa cells in antral follicles during aging. It seems that beneficial effects of vitamin C on ovarian aging observed in the present study might be due to its antioxidant effects as well as its impact on vascularization, metabolism, inflammation, and AKT/mTOR signaling pathway as mentioned before.

However, there are contradictions about the benefits of vitamin C on reproduction. The effects of vitamin C in combination with other supplements has been evaluated on cases with female factor infertility such as polycystic ovarian syndrome and unexplained infertility but there was insufficient evidence to support supplemental oral antioxidants prescribing in those women [25]. Similar results have been obtained in pregnant women. Administration of vitamin C alone or in combination with other supplements had no effects on pregnancy results although there were controversial results regarding premature rupture of membranes and placental abruption [46]. In a study, Camarena and Wang [44] reported that adding ascorbic acid to culture medium of hen granulosa cells did not induce antioxidant effects and interestingly the activity of SOD in granulosa decreased in higher doses of ascorbic acid. They concluded that vitamin C might have regulatory role in biochemical and physiological processes in granulosa cells [44].

Collectively, according to our study, vitamin C compensated undesirable effects of aging on ovarian tissue. Our study supports role of vitamin C supplementation for reduce and prevention of ovarian aging complications especially in women delaying childbearing for the several reasons.

References

- 1.Bowen RL, Atwood CS. Living and dying for sex: a theory of aging based on the modulation of cell cycle signaling by reproductive hormones. Gerontology. 2004;50:265–290. doi: 10.1159/000079125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dillin A, Gottschling DE, Nyström T. The good and the bad of being connected: the integrons of aging. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2014;26:107–112. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2013.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Broekmans FJ, Soules MR, Fauser BC. Ovarian aging: mechanisms and clinical consequences. Endocr Rev. 2009;30:465–493. doi: 10.1210/er.2009-0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balasch J, Gratacós E. Delayed childbearing: effects on fertility and the outcome of pregnancy. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2011;29:263–273. doi: 10.1159/000323142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aboulfoutouh I, Youssef M, Khattab S. Can antioxidants supplementation improve ICSI/IVF outcomes in women undergoing IVF/ICSI treatment cycles? Randomised controlled study. Fertil Steril. 2011;96(3 Suppl):S242. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang T, Zhang M, Jiang Z, Seli E. Mitochondrial dysfunction and ovarian aging. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2017;77:e12651. doi: 10.1111/aji.12651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu J, Wu DC, Qu LH, Liao HQ, Li MX. The role of mTOR in ovarian neoplasms, polycystic ovary syndrome, and ovarian aging. Clin Anat. 2018;31:891–898. doi: 10.1002/ca.23211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scheffer GJ, Broekmans FJ, Dorland M, Habbema JD, Looman CW, te Velde ER. Antral follicle counts by transvaginal ultrasonography are related to age in women with proven natural fertility. Fertil Steril. 1999;72:845–851. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(99)00396-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ng EH, Tang OS, Ho PC. The significance of the number of antral follicles prior to stimulation in predicting ovarian responses in an IVF programme. Hum Reprod. 2000;15:1937–1942. doi: 10.1093/humrep/15.9.1937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hunt PA, Hassold TJ. Human female meiosis: what makes a good egg go bad? Trends Genet. 2008;24:86–93. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2007.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Rooij IA, Tonkelaar I, Broekmans FJ, Looman CW, Scheffer GJ, de Jong FH, Themmen AP, te Velde ER. Anti-mullerian hormone is a promising predictor for the occurrence of the menopausal transition. Menopause. 2004;11(6 Pt 1):601–606. doi: 10.1097/01.gme.0000123642.76105.6e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sowers MR, Eyvazzadeh AD, McConnell D, Yosef M, Jannausch ML, Zhang D, Harlow S, Randolph JF., Jr Anti-mullerian hormone and inhibin B in the definition of ovarian aging and the menopause transition. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:3478–3483. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-0567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sukur YE, Kivancli IB, Ozmen B. Ovarian aging and premature ovarian failure. J Turk Ger Gynecol Assoc. 2014;15:190–196. doi: 10.5152/jtgga.2014.0022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ito M, Muraki M, Takahashi Y, Imai M, Tsukui T, Yamakawa N, Nakagawa K, Ohgi S, Horikawa T, Iwasaki W, Iida A, Nishi Y, Yanase T, Nawata H, Miyado K, Kono T, Hosoi Y, Saito H. Glutathione S-transferase theta 1 expressed in granulosa cells as a biomarker for oocyte quality in age-related infertility. Fertil Steril. 2008;90:1026–1035. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.07.1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lim J, Luderer U. Oxidative damage increases and antioxidant gene expression decreases with aging in the mouse ovary. Biol Reprod. 2011;84:775–782. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.110.088583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tatone C, Amicarelli F. The aging ovary: the poor granulosa cells. Fertil Steril. 2013;99:12–17. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gundersen HJ, Bendtsen TF, Korbo L, Marcussen N, Moller A, Nielsen K, Nyengaard JR, Pakkenberg B, Sorensen FB, Vesterby A, West MJ. Some new, simple and efficient stereological methods and their use in pathological research and diagnosis. APMIS. 1988;96:379–394. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1988.tb05320.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Soleimani Mehranjani M, Mansoori T. Stereological study on the effect of vitamin C in preventing the adverse effects of bisphenol A on rat ovary. Int J Reprod Biomed (Yazd) 2016;14:403–410. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Panti AA, Shehu CE, Saidu Y, Tunau KA, Nwobodo EI, Jimoh A, Bilbis LS, Umar AB, Hassan M. Oxidative stress and outcome of antioxidant supplementation in patients with polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) Int J Reprod Contracept Obstet Gynecol. 2018;7:1667–1672. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arab SA, Nikravesh MR, Jalali M, Fazel A. Evaluation of oxidative stress indices after exposure to malathion and protective effects of ascorbic acid in ovarian tissue of adult female rats. Electron Physician. 2018;10:6789–6795. doi: 10.19082/6789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang M, Teng S, Ma C, Yu Y, Wang P, Yi C. Ascorbic acid inhibits senescence in mesenchymal stem cells through ROS and AKT/mTOR signaling. Cytotechnology. 2018;70:1301–1313. doi: 10.1007/s10616-018-0220-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oudemans-van Straaten HM, Spoelstra-de Man AM, de Waard MC. Vitamin C revisited. Crit Care. 2014;18:460. doi: 10.1186/s13054-014-0460-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fujisawa K, Hara K, Takami T, Okada S, Matsumoto T, Yamamoto N, Sakaida I. Evaluation of the effects of ascorbic acid on metabolism of human mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2018;9:93. doi: 10.1186/s13287-018-0825-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Park S, Ahn S, Shin Y, Yang Y, Yeom CH. Vitamin C in cancer: a metabolomics perspective. Front Physiol. 2018;9:762. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2018.00762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Showell MG, Mackenzie-Proctor R, Jordan V, Hart RJ. Antioxidants for female subfertility. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;7:CD007807. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007807.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gundersen HJ, Bagger P, Bendtsen TF, Evans SM, Korbo L, Marcussen N, Moller A, Nielsen K, Nyengaard JR, Pakkenberg B, Sorensen FB, Vesterby A, West MJ. The new stereological tools: disector, fractionator, nucleator and point sampled intercepts and their use in pathological research and diagnosis. APMIS. 1988;96:857–881. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1988.tb00954.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harman D. Free radical theory of aging: an update: increasing the functional life span. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1067:10–21. doi: 10.1196/annals.1354.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sharov AA, Falco G, Piao Y, Poosala S, Becker KG, Zonderman AB, Longo DL, Schlessinger D, Ko M. Effects of aging and calorie restriction on the global gene expression profiles of mouse testis and ovary. BMC Biol. 2008;6:24. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-6-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Agarwal A, Gupta S, Sharma RK. Role of oxidative stress in female reproduction. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2005;3:28. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-3-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Finkel T, Holbrook NJ. Oxidants, oxidative stress and the biology of ageing. Nature. 2000;408:239–247. doi: 10.1038/35041687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arteaga E, Villaseca P, Rojas A, Arteaga A, Bianchi M. Comparison of the antioxidant effect of estriol and estradiol on low density lipoproteins in post-menopausal women. Rev Med Chil. 1998;126:481–487. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aten RF, Duarte KM, Behrman HR. Regulation of ovarian antioxidant vitamins, reduced glutathione, and lipid peroxidation by luteinizing hormone and prostaglandin F2 alpha. Biol Reprod. 1992;46:401–407. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod46.3.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Luderer U, Kavanagh TJ, White CC, Faustman EM. Gonadotropin regulation of glutathione synthesis in the rat ovary. Reprod Toxicol. 2001;15:495–504. doi: 10.1016/s0890-6238(01)00157-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gardiner CS, Salmen JJ, Brandt CJ, Stover SK. Glutathione is present in reproductive tract secretions and improves development of mouse embryos after chemically induced glutathione depletion. Biol Reprod. 1998;59:431–436. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod59.2.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sato EF, Kobuchi H, Edashige K, Takahashi M, Yoshioka T, Utsumi K, Inoue M. Dynamic aspects of ovarian superoxide dismutase isozymes during the ovulatory process in the rat. FEBS Lett. 1992;303:121–125. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(92)80502-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tatone C, Carbone MC, Falone S, Aimola P, Giardinelli A, Caserta D, Marci R, Pandolfi A, Ragnelli AM, Amicarelli F. Age-dependent changes in the expression of superoxide dismutases and catalase are associated with ultrastructural modifications in human granulosa cells. Mol Hum Reprod. 2006;12:655–660. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gal080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Okatani Y, Morioka N, Wakatsuki A, Nakano Y, Sagara Y. Role of the free radical-scavenger system in aromatase activity of the human ovary. Horm Res. 1993;39(Suppl 1):22–27. doi: 10.1159/000182753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Matos L, Stevenson D, Gomes F, Silva-Carvalho JL, Almeida H. Superoxide dismutase expression in human cumulus oophorus cells. Mol Hum Reprod. 2009;15:411–419. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gap034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leridon H. Can assisted reproduction technology compensate for the natural decline in fertility with age? A model assessment. Hum Reprod. 2004;19:1548–1553. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gomes RG, Lisboa LA, Silva CB, Max MC, Marino PC, Oliveira RL, Gonzalez SM, Barreiros TR, Marinho LS, Seneda MM. Improvement of development of equine preantral follicles after 6 days of in vitro culture with ascorbic acid supplementation. Theriogenology. 2015;84:750–755. doi: 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2015.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tarin JJ. Potential effects of age-associated oxidative stress on mammalian oocytes/embryos. Mol Hum Reprod. 1996;2:717–724. doi: 10.1093/molehr/2.10.717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wu J, Zhang L, Wang X. Maturation and apoptosis of human oocytes in vitro are age-related. Fertil Steril. 2000;74:1137–1141. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(00)01597-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tarín JJ, Pérez-Albalá S, Cano A. Oral antioxidants counteract the negative effects of female aging on oocyte quantity and quality in the mouse. Mol Reprod Dev. 2002;61:385–397. doi: 10.1002/mrd.10041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Camarena V, Wang G. The epigenetic role of vitamin C in health and disease. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2016;73:1645–1658. doi: 10.1007/s00018-016-2145-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Andrade ER, van den Hurk R, Lisboa LA, Hertel MF, Melo-Sterza FA, Moreno K, Bracarense AP, Landim-Alvarenga FC, Seneda MM, Alfieri AA. Effects of ascorbic acid on in vitro culture of bovine preantral follicles. Zygote. 2012;20:379–388. doi: 10.1017/S0967199412000056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rumbold A, Ota E, Nagata C, Shahrook S, Crowther CA. Vitamin C supplementation in pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(9):CD004072. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004072.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]