Highlights

-

•

Gene expression determined by the genome mediating a response to cell environment.

-

•

Genetic variation results in distinct individual response in gene expression.

-

•

Non-coding DNA is an important site for such functional genetic variation.

-

•

Gene expression is a major modulator of brain chemistry and thus behavior.

Abstract

Over 98% of our genome is non-coding and is now recognised to have a major role in orchestrating the tissue specific and stimulus inducible gene expression pattern which underpins our wellbeing and mental health. The non-coding genome responds functionally to our environment at all levels, encompassing the span from psychological to physiological challenge. The gene expression pattern, termed the transcriptome, ultimately gives us our neurochemistry. Therefore a major modulator of mental wellbeing is how our genes are regulated in response to life experiences. Superimposed on the aforementioned non-coding DNA framework is a vast body of genetic variation in the elements that control response to challenges. These differences, termed polymorphisms, allow for a differential response from a specific DNA element to the same challenge thus potentially allowing ‘individuality’ in the modulation of our transcriptome. This review will focus on a fundamental mechanism defining our psychological and psychiatric wellbeing, namely how genetic variation can be correlated with differential gene expression in response to specific challenges, thus resulting in altered neurochemistry which consequently may shape behaviour.

Current Opinion in Psychology 2019, 27:18–24

This review comes from a themed issue on Genetics

Edited by Brian B Boutwell and Michael A White

For a complete overview see the Issue and the Editorial

Available online 24th July 2018

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2018.07.006

2352-250X/© 2018 The Authors. Published by Elsevier Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Introduction

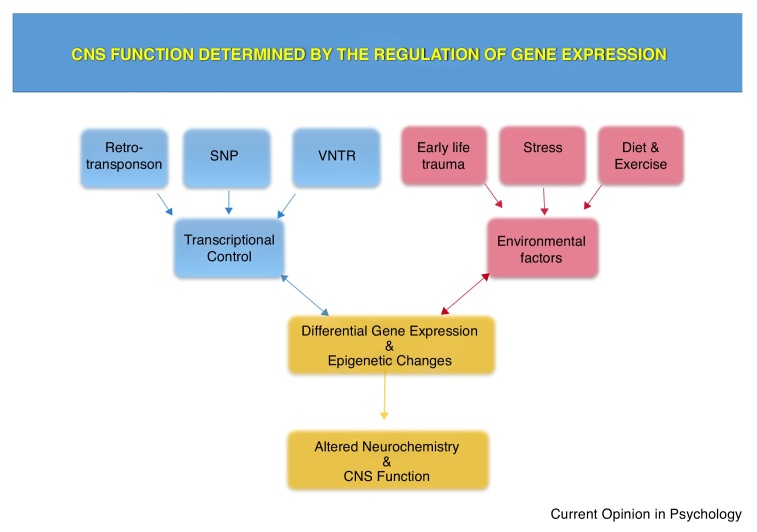

The human genome has evolved to include a combination of both highly conserved regions of regulatory non-coding DNA (ncDNA) found across many species and human-specific regulatory DNA elements which together act to regulate expression of mRNA. This combination of DNA elements allows determination of where, when, how much and for how long, genes are expressed in the human brain in response to normal developmental, psychological and physiological cues, Figure 1. Many of these elements exhibit genetic variation which is not only associated with risk for a specific condition, but has also been demonstrated to alter the regulatory properties of the gene. The functional interpretation and analysis of ncDNA variation can be initially addressed in silico by overlaying its position on databases containing characterised and predicted functional elements within the genome, Box 1. The most easily accessible free database is the Encyclopaedia of DNA Elements (ENCODE; https://www.encodeproject.org/) which is a collaboration of research groups funded by the National Human Genome Research Institute [1,2••], this can be used in combination with a plethora of other database browsers [3] such as the University of California Santa Cruz (UCSC) Genome Browser (http://genome.ucsc.edu/) [4]. This review will begin with an introduction to the most conserved regulatory regions in the genome and how these may be functionally modified by the simplest and most extensively studied class of genetic variation, single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). The review will then focus on human regulatory elements that are associated with neuropsychiatric conditions which are larger blocks of DNA variation such as variable number tandem repeats (VNTRs) and non-long terminal repeat (non-LTR) retrotransposons, Box 2.

Figure 1.

CNS function is determined by the regulation of gene expression.

Box 1. Genome Browsers to interrogate DNA function.

Encyclopaedia of DNA Elements (https://www.encodeproject.org/)

Evolutionary conserved regions browser (https://ecrbrowser.dcode.org/)

NIH Roadmap Epigenomics Consortium (http://www.roadmapepigenomics.org/)

University of California Santa Cruz (UCSC) Genome Browser (http://genome.ucsc.edu/)

Alt-text: Box 1

Box 2. Genetic variation commonly found in the genome.

SNP: single nucleotide polymorphism

The most common form of genetic variation in the genome. When located in a coding exon it may change the amino acid encoded thus altering the protein. In non-coding DNA it may have a variety of functions, however since transcription factors are sequence specific DNA binding proteins it could change the affinity or specificity of that interaction thus altering the function of a specific DNA element.

VNTR: variable number tandem repeats

These are adjacent repeats of single or more nucleotides and are a large component of the non-coding DNA. Often used in forensic DNA analysis as a genetic fingerprint given their variation in the genome. They are routinely separated into microsatellites (ranging in repeat length from 1 to 9 base pairs) and minisatellites (ranging in length from 10 to 60 base pairs), both classes are generally repeated 3-50 times. They are also found in exons such as in the Huntington gene.

RTE: retrotransposon

RTEs constitute approximately 42% of the human genome. Retrotransposons can be subdivided in long terminal repeat (LTR) retrotransposons (also termed ‘endogenous retroviruses’) and non-LTR retrotransposons lacking LTRs. Non-LTR retrotransposons propagate via a copy-and-paste mechanism, meaning that retrotransposon transcripts are reverse transcribed into a cDNA intermediate which is integrated into a new site of the host genome. Non-LTR retrotransposons can be sub-divided into LINE-1, Alu and SINE-VNTR-Alu (SVA) families which have the capacity to modify gene expression at transcriptional and post transcriptional levels. They constitute 21%, 13% and 0.2% respectively of the human genome.

Alt-text: Box 2

Evolutionary conserved regions

Evolutionary conserved regions (ECRs) in the genome can be easily found using the ECR browser (https://ecrbrowser.dcode.org/) [5]. ECRs in this browser are typically defined as regions of sequence within the human genome that retain 70% or more sequence identity over a window of 100 bases when compared to the corresponding region of sequence in other species, this will frequently include exons in coding DNA. However, Pennacchio et al., were amongst the first to demonstrate that ECRs in the non-coding DNA (ncECRs) could be important, particularly in directing gene expression in the CNS. They determined by use of a transgenic mouse model that whilst ncECRs could direct expression in a broad range of anatomical structures in the embryo, the majority of the ncECRs tested directed expression to various regions of the developing nervous system [6]. Subsequently, consistent with this, a third of paralogous ncECRs examined were predicted to have regulatory activity in the brain [7], for example, deletion of ncECRs in the neuronal transcription factor Arx resulted in substantial alterations of neuron populations and structural brain defects in a trangenic model [8]. Furthermore, the combinatorial complexity of gene expression was exquistely demonstrated in a transgenic model of craniofacial morphology in which the action of multiple ncECRs driving expression of many genes resulted in a vast array of facial differences [9••]. These studies demonstrated that ncECRs can have important transcripitonal regulatory properties, therefore the expectation is that polymorphism in such domains has the potential to modify interactions with transcription factors and thus affect regulatory function.

Single nucleotide polymorphisms

Early studies of genetic variation correlated with mental health focused on DNA variation in exons encoding proteins. Most of these studies addressed SNPs; thus a SNP that changed an amino acid (non-synonymous change) or resulted in a truncation of the protein could be mechanistically relevant as it could alter protein function. However, with technological advances the ability to address SNPs in genome wide association studies (GWAS) rather than solely exons, demonstrated that the vast bulk of SNP variation associated with behavioural and psychiatric conditions was in ncDNA [10,11]. GWAS has led to significant discoveries in defining some of the genes involved in neuropsychiatric disorders and demonstrated there is genetic overlap between many of the major psychiatric disorders [12,13]. In several examples the proteins identified can work together to alter a key pathway underpinning wellbeing and mental health, such as those modifying calcium signalling [14].

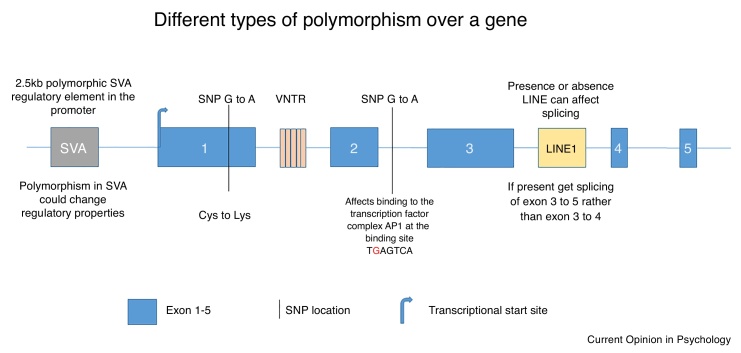

Understanding the mechanistic significance of SNPs in ncDNA for a specific condition has been a much more difficult task than for SNPs found in exons. A SNP in ncDNA could be tagging a regulatory domain 10K+ bases from itself (a tagging SNP is representative of a large section of DNA that is inherited as one, thus the SNP is not the causative agent but rather highlights a region of DNA). Analysis of SNP variation within ENCODE and associated data sets can determine if it is present in a genomic region defined as a regulatory domain. In this scenario, the SNP could affect the efficiency or specificity with which a transcription factor, proteins which modulate the process of transcription, would bind to this regulatory DNA sequence, Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Different types of polymorphism over a gene.

We and others demonstrated that SNP polymorphisms in ncECRs which correlated with known behavioural problems could modify the regulatory properties of the ECR including those associated with depression located in BDNF, BICC1 and galanin genes [15, 16, 17, 18, 19]. Furthermore multiple ncECRs may be required for appropriate gene expression, for example eight conserved ncECRs were identified at the schizophrenia-associated MIR137/DPYD locus of these, six were shown to be positive transcriptional regulators, and two negative transcriptional regulators in a human cell line model [18,19]. Bioinformatic analysis of this locus using the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium GWAS dataset for schizophrenia highlighted five of the ncECRs had genome-wide significant SNPs in, or adjacent to their sequence [11].

Epigenetic marks which are indicative of active or inactive chromatin, are often found at regulatory DNA. Genetic variation such as GWAS risk SNPs, can effect such epigenetic parameters impacting on long term regulatory changes in response to challenge [20]. Both local (gene specific) and global (multigene) epigenetic changes have been implicated in neuropsychiatric disorders [21,22] and the NIH Roadmap Epigenomics Consortium (http://www.roadmapepigenomics.org/) data can be utilised to analyse such data. For example, local methylation variation at the glucocorticoid receptor gene has been associated with prenatal and postnatal depression [23•] and global differences in methylation in astrocytes have been associated with depression [24]. Simplistically, methylation of regulatory regions is considered a repressor of transcription as it interferes with transcription factor binding by limiting the accessibility of specific DNA recognition sequences. The ability to rapidly address genetic variation on a ‘road map’ of regulatory domains has allowed the development of a significantly better understanding of how the ncDNA GWAS SNPs can be mechanistically involved in mental health issues [25]. This can be further updated within the UCSC browser which permits new, novel data to be overlaid on the existing data from ENCODE.

Variable number tandem repeats

SNP variation is not the only example of ncDNA variation that can affect the regulation of gene expression. Many of the best characterised genetic polymorphisms correlating with mental health issues are found in repetitive DNA, Figure 2. These include the VNTRs [26], examples of which have been identified in key behavioural and mental health-related genes. VNTRs have been demonstrated to be both biomarkers and transcriptional regulators in genes such as the serotonin transporter, the dopamine transporter and monoamine oxidase A [21,22,27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32]. In these three examples, the primary DNA sequences of the VNTRs are rapidly evolving such that humans have their own specific VNTR sequences. All three of these monoaminergic genes contain a minimum of two VNTRs that have been demonstrated to act both independently and synergistically as transcriptional regulators whose function is further modulated by the repeat copy number within the VNTR [21,29,31]. The copy number of the repeat itself is also a biomarker for good mental health and wellbeing thus correlating function with phenotype [27,28,31,33,34]. Perhaps not unexpectedly VNTRs and GWAS SNPs in the same promoter may act additively or synergistically to regulate gene expression. This is exemplified by one of the promoters of the schizophrenia candidate risk gene, MIR137 [35,36•], where experimentally in vitro, the VNTR in the promoter can support differential reporter gene expression based on the copy number of the repeat within the VNTR, and inclusion of the promoter region encompassing the GWAS SNP can further modulate expression depending on the allele of the SNP present. This illustrates a route to identifying the potential functional significance of non-coding variants in transcriptional or post transcriptional regulatory mechanisms in areas distinct from the region of the DNA in which the GWAS SNP is found.

The rapid evolution of VNTRs has been noted more globally for contributing to primate evolution; analysis in humans and non-human great apes identified that genes with VNTRs have higher expression divergence than those without [37]. The association of VNTRs with gene expression is reflected in the finding that VNTRs are enriched in promoter regions and locations close to transcriptional start sites for mRNA expression [26,38,39]. Generally, VNTRs have not been analysed as extensively as SNPs which may be attributed to the requirement to perform PCR to genotype each VNTR target and the inability to accurately identify such regions in the initial short read whole genome sequencing protocols. Improved depth and coverage in whole genome sequence combined with the development of bioinformatic programmes such as ExpansionHunter may improve the association of VNTRs and other repeat variants with neuropsychiatric conditions [40].

Non-LTR retrotransposons

Non-long terminal repeat (non-LTR) retrotransposons are mobile DNA elements that can copy and paste themselves into new genomic loci and are therefore polymorphic for their presence or absence at specific loci in the genome. These retrotransposable elements (RTEs), also known as ‘jumping genes’, can range in size from a few hundred to 6000 base pairs and have been shown to be major modulators of gene expression at several levels. Non-LTR retrotransposons comprise three classes, long interspersed nuclear element 1 (LINE-1), Alu and ‘SINE-VNTR-Alu’ (SVA), Figure 2. LINE-1 expression has been implicated in many neuropsychiatric conditions such as depression [41], addiction [42], schizophrenia [43, 44, 45] and autism [46]. The other two classes have also been implicated in CNS function, for example variation in the Alu sequence within an intron of the TOMM40 gene is associated with non-pathogenic cognitive decline [47] and X-Linked Dystonia-Parkinsonism is associated with the presence or absence of a SVA in the TAF1 gene [48••]. SVAs contain several distinct VNTR elements and have properties consistent with transcriptional regulation [49,50•,51].

There has been tremendous interest in RTEs, due to their ability to make a copy of themselves which then can reinsert at a different locus in the genome of that cell. Depending on when this occurs, it results in either novel heritable germline variation or somatic mutation that can alter cellular function in only the individual affected. The former generates a large reservoir of de novo genomic variation in the population which, to date, is poorly characterised as it is very seldom annotated properly in the DNA sequence databases. The mobilisation or ‘jumping’ of RTEs is proposed to increase both with age within the adult CNS and to comprise one of the key mechanisms underpinning age-related CNS problems [52••,53,54•]; several instances where this variation has been addressed, have associated it with disease [48••,55]. More recently bioinformatic analysis has improved to allow robust identification of RTEs using programmes such as TEBreak (https://github.com/adamewing/tebreak) and MELT [56•].

Development

The basic transcriptional mechanisms outlined in this review will also operate during development. Conditions such as schizophrenia and autism are often referred to as having a neurodevelopmental origin [57,58]. Modulation of the transcriptome during development could have a significant effect on the wiring of the brain and therefore how information is processed in the future. Early in vivo work using a mouse transgenic model indicated how a human serotonin transporter VNTR could differentially affect gene expression in key areas of serotonergic lineage based on the copy number of the repeat unit [32,59]. The regulation of regulatory domains during development will be determined by the co-expression of transcription factors as exemplified by the schizophrenia associated gene CACNA1C whose expression in development mirrors that of the transcription factor EZH2 an important regulator of the CACNA1C gene promoter [14]. An argument can be made that alterations in the transcriptome at specific times in foetal development could result in a physical change in neuronal connections that would be more difficult to correct than transcriptome changes in the adult [60].

Summary

The identification of variation in the non-coding part of the genome which affects the regulation of gene expression in part explains the often episodic nature of mental health conditions. In addition, it offers the potential for resolution of these conditions by a variety of interventions ranging from pharmaceutical to cognitive behavioural therapy which modify the signalling pathways targeting specific gene regulatory domains, modulation of the ‘stress’ driving such pathways would alter the transcriptome and hence brain chemistry, Figure 1. A prior exposure to trauma or stress could leave a molecular scar of that event, represented by an epigenetic change which alters parameters of transcriptional or post transcriptional regulation in the medium to long term [61]. It is often considered that the environmental challenge needed to affect mental health should be severe, which is not necessarily correct. For example ‘normal’ child development could also have an effect on mental health and wellbeing [23•,27,33,62]. Similarly a more general approach to maintaining good mental health via diet and exercise could play a role as they could affect the cellular signalling pathways that affect mental health [63,64]. However these issues only illustrate the complexity of defining ‘life style/environment’ and its effect on our wellbeing given the complex nature of life-long experiences in defining our transcriptome, which in turn affects the neurochemistry that ultimately shapes CNS function. It’s often said that the genome is the roadmap through which ‘life style’ shapes the individual, however one can argue that the roadmap is unique for each one of us and we all have our own route to travel [65].

Conflict of interest

None of the authors have interests to declare, thus we are stating officially ‘Declarations of interest: none'.

References and recommended reading

Papers of particular interest, published within the period of review, have been highlighted as:

• of special interest

•• of outstanding interest

Acknowledgements

JPQ is funded by the Medical Research Council (UK) G0400577

References

- 1.Rosenbloom K.R., Sloan C.A., Malladi V.S., Dreszer T.R., Learned K., Kirkup V.M., Wong M.C., Maddren M., Fang R., Heitner S.G. ENCODE data in the UCSC Genome Browser: year 5 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:D56–D63. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2••.Davis C.A., Hitz B.C., Sloan C.A., Chan E.T., Davidson J.M., Gabdank I., Hilton J.A., Jain K., Baymuradov U.K., Narayanan A.K. The Encyclopedia of DNA elements (ENCODE): data portal update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:D794–D801. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx1081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; The ENCODE consortia have given us a tool box for interpreting the potential function of DNA element.

- 3.Rigden D.J., Fernandez X.M. The 2018 Nucleic Acids Research database issue and the online molecular biology database collection. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:D1–D7. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx1235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kent W.J., Sugnet C.W., Furey T.S., Roskin K.M., Pringle T.H., Zahler A.M., Haussler D. The human genome browser at UCSC. Genome Res. 2002;12:996–1006. doi: 10.1101/gr.229102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ovcharenko I., Nobrega M.A., Loots G.G., Stubbs L. ECR Browser: a tool for visualizing and accessing data from comparisons of multiple vertebrate genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:W280–W286. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pennacchio L.A., Ahituv N., Moses A.M., Prabhakar S., Nobrega M.A., Shoukry M., Minovitsky S., Dubchak I., Holt A., Lewis K.D. In vivo enhancer analysis of human conserved non-coding sequences. Nature. 2006;444:499–502. doi: 10.1038/nature05295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matsunami M., Saitou N. Vertebrate paralogous conserved noncoding sequences may be related to gene expressions in brain. Genome Biol Evol. 2013;5:140–150. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evs128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dickel D.E., Ypsilanti A.R., Pla R., Zhu Y., Barozzi I., Mannion B.J., Khin Y.S., Fukuda-Yuzawa Y., Plajzer-Frick I., Pickle C.S. Ultraconserved enhancers are required for normal development. Cell. 2018;172 doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.12.017. 491–499 e415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9••.Attanasio C., Nord A.S., Zhu Y., Blow M.J., Li Z., Liberton D.K., Morrison H., Plajzer-Frick I., Holt A., Hosseini R. Fine tuning of craniofacial morphology by distant-acting enhancers. Science. 2013;342:1241006. doi: 10.1126/science.1241006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; A tour de force of how regulatary DNA can result in no two faces being the same.

- 10.Van der Auwera S., Peyrot W.J., Milaneschi Y., Hertel J., Baune B., Breen G., Byrne E., Dunn E.C., Fisher H., Homuth G. Genome-wide gene-environment interaction in depression: a systematic evaluation of candidate genes: the childhood trauma working-group of PGC-MDD. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2018;177:40–49. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.32593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sullivan P.F., Agrawal A., Bulik C.M., Andreassen O.A., Borglum A.D., Breen G., Cichon S., Edenberg H.J., Faraone S.V., Gelernter J. Psychiatric genomics: an update and an agenda. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175:15–27. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2017.17030283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee S.H., Ripke S., Neale B.M., Faraone S.V., Purcell S.M., Perlis R.H., Mowry B.J., Thapar A., Goddard M.E., Witte J.S. Genetic relationship between five psychiatric disorders estimated from genome-wide SNPs. Nat Genet. 2013;45:984–994. doi: 10.1038/ng.2711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Power R.A., Tansey K.E., Buttenschon H.N., Cohen-Woods S., Bigdeli T., Hall L.S., Kutalik Z., Lee S.H., Ripke S., Steinberg S. Genome-wide association for major depression through age at onset stratification: major depressive disorder working group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium. Biol Psychiatry. 2017;81:325–335. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2016.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Billingsley K.J., Manca M., Gianfrancesco O., Collier D.A., Sharp H., Bubb V.J., Quinn J.P. Regulatory characterisation of the schizophrenia-associated CACNA1C proximal promoter and the potential role for the transcription factor EZH2 in schizophrenia aetiology. Schizophr Res. 2018 doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2018.02.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davidson S., Shanley L., Cowie P., Lear M., McGuffin P., Quinn J.P., Barrett P., MacKenzie A. Analysis of the effects of depression associated polymorphisms on the activity of the BICC1 promoter in amygdala neurones. Pharmacogenomics J. 2016;16:366–374. doi: 10.1038/tpj.2015.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hing B., Davidson S., Lear M., Breen G., Quinn J., McGuffin P., Mackenzie A. A polymorphism associated with depressive disorders differentially regulates brain derived neurotrophic factor promoter IV activity. Biol Psychiatry. 2012;71:618–626. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.11.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davidson S., Lear M., Shanley L., Hing B., Baizan-Edge A., Herwig A., Quinn J.P., Breen G., McGuffin P., Starkey A. Differential activity by polymorphic variants of a remote enhancer that supports galanin expression in the hypothalamus and amygdala: implications for obesity, depression and alcoholism. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011;36:2211–2221. doi: 10.1038/npp.2011.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gianfrancesco O., Warburton A., Collier D.A., Bubb V.J., Quinn J.P. Novel brain expressed RNA identified at the MIR137 schizophrenia-associated locus. Schizophr Res. 2017;184:109–115. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2016.11.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gianfrancesco O., Griffiths D., Myers P., Collier D.A., Bubb V.J., Quinn J.P. Identification and potential regulatory properties of evolutionary conserved regions (ECRs) at the Schizophrenia-Associated MIR137 Locus. J Mol Neurosci. 2016;60:239–247. doi: 10.1007/s12031-016-0812-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kundaje A., Meuleman W., Ernst J., Bilenky M., Yen A., Heravi-Moussavi A., Kheradpour P., Zhang Z., Wang J., Ziller M.J. Integrative analysis of 111 reference human epigenomes. Nature. 2015;518:317–330. doi: 10.1038/nature14248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Manca M., Pessoa V., Lopez A.I., Harrison P.T., Miyajima F., Sharp H., Pickles A., Hill J., Murgatroyd C., Bubb V.J. The regulation of monoamine oxidase A gene expression by distinct variable number tandem repeats. J Mol Neurosci. 2018 doi: 10.1007/s12031-018-1044-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vasiliou S.A., Ali F.R., Haddley K., Cardoso M.C., Bubb V.J., Quinn J.P. The SLC6A4 VNTR genotype determines transcription factor binding and epigenetic variation of this gene in response to cocaine in vitro. Addict Biol. 2012;17:156–170. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2010.00288.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23•.Murgatroyd C., Quinn J.P., Sharp H.M., Pickles A., Hill J. Effects of prenatal and postnatal depression, and maternal stroking, at the glucocorticoid receptor gene. Transl Psychiatry. 2015;5:e560. doi: 10.1038/tp.2014.140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Interaction of mother and child affecting epigenetic variation in the child.

- 24.Nagy C., Suderman M., Yang J., Szyf M., Mechawar N., Ernst C., Turecki G. Astrocytic abnormalities and global DNA methylation patterns in depression and suicide. Mol Psychiatry. 2015;20:320–328. doi: 10.1038/mp.2014.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhao J., Cheng F., Jia P., Cox N., Denny J.C., Zhao Z. An integrative functional genomics framework for effective identification of novel regulatory variants in genome-phenome studies. Genome Med. 2018;10:7. doi: 10.1186/s13073-018-0513-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Breen G., Collier D., Craig I., Quinn J. Variable number tandem repeats as agents of functional regulation in the genome. IEEE Eng Med Biol Mag. 2008;27:103–104. doi: 10.1109/EMB.2008.915501. 108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pickles A., Hill J., Breen G., Quinn J., Abbott K., Jones H., Sharp H. Evidence for interplay between genes and parenting on infant temperament in the first year of life: monoamine oxidase A polymorphism moderates effects of maternal sensitivity on infant anger proneness. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2013;54:1308–1317. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Haddley K., Bubb V.J., Breen G., Parades-Esquivel U.M., Quinn J.P. Behavioural genetics of the serotonin transporter. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 2012;12:503–535. doi: 10.1007/7854_2011_186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ali F.R., Vasiliou S.A., Haddley K., Paredes U.M., Roberts J.C., Miyajima F., Klenova E., Bubb V.J., Quinn J.P. Combinatorial interaction between two human serotonin transporter gene variable number tandem repeats and their regulation by CTCF. J Neurochem. 2010;112:296–306. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06453.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roberts J., Scott A.C., Howard M.R., Breen G., Bubb V.J., Klenova E., Quinn J.P. Differential regulation of the serotonin transporter gene by lithium is mediated by transcription factors, CCCTC binding protein and Y-box binding protein 1, through the polymorphic intron 2 variable number tandem repeat. J Neurosci. 2007;27:2793–2801. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0892-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guindalini C., Howard M., Haddley K., Laranjeira R., Collier D., Ammar N., Craig I., O’Gara C., Bubb V.J., Greenwood T. A dopamine transporter gene functional variant associated with cocaine abuse in a Brazilian sample. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:4552–4557. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504789103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.MacKenzie A., Quinn J. A serotonin transporter gene intron 2 polymorphic region, correlated with affective disorders, has allele-dependent differential enhancer- like properties in the mouse embryo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:15251–15255. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.26.15251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hill J., Breen G., Quinn J., Tibu F., Sharp H., Pickles A. Evidence for interplay between genes and maternal stress in utero: monoamine oxidase A polymorphism moderates effects of life events during pregnancy on infant negative emotionality at 5 weeks. Genes Brain Behav. 2013;12:388–396. doi: 10.1111/gbb.12033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brotons O., O’Daly O.G., Guindalini C., Howard M., Bubb J., Barker G., Dalton J., Quinn J., Murray R.M., Breen G. Modulation of orbitofrontal response to amphetamine by a functional variant of DAT1 and in vitro confirmation. Mol Psychiatry. 2010 doi: 10.1038/mp.2009.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Warburton A., Breen G., Bubb V.J., Quinn J.P. A GWAS SNP for schizophrenia is linked to the internal MIR137 promoter and supports differential allele-specific expression. Schizophr Bull. 2016;42:1003–1008. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbv144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36•.Warburton A., Breen G., Rujescu D., Bubb V.J., Quinn J.P. Characterization of a REST-regulated internal promoter in the schizophrenia genome-wide associated gene MIR137. Schizophr Bull. 2015;41:698–707. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbu117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Demonstration of how a polymorphic regulatory variant could drive differential expression of the microRNA MIR137 by the action of a transcription previously predicted to be a major modulator of chromatin structure in schizophrenia.

- 37.Bilgin Sonay T., Carvalho T., Robinson M.D., Greminger M.P., Krutzen M., Comas D., Highnam G., Mittelman D., Sharp A., Marques-Bonet T. Tandem repeat variation in human and great ape populations and its impact on gene expression divergence. Genome Res. 2015;25:1591–1599. doi: 10.1101/gr.190868.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Quilez J., Guilmatre A., Garg P., Highnam G., Gymrek M., Erlich Y., Joshi R.S., Mittelman D., Sharp A.J. Polymorphic tandem repeats within gene promoters act as modifiers of gene expression and DNA methylation in humans. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:3750–3762. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sawaya S., Bagshaw A., Buschiazzo E., Kumar P., Chowdhury S., Black M.A., Gemmell N. Microsatellite tandem repeats are abundant in human promoters and are associated with regulatory elements. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e54710. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dolzhenko E., van Vugt J., Shaw R.J., Bekritsky M.A., van Blitterswijk M., Narzisi G., Ajay S.S., Rajan V., Lajoie B.R., Johnson N.H. Detection of long repeat expansions from PCR-free whole-genome sequence data. Genome Res. 2017;27:1895–1903. doi: 10.1101/gr.225672.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu S., Du T., Liu Z., Shen Y., Xiu J., Xu Q. Inverse changes in L1 retrotransposons between blood and brain in major depressive disorder. Sci Rep. 2016;6:37530. doi: 10.1038/srep37530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Doyle G.A., Doucet-O’Hare T.T., Hammond M.J., Crist R.C., Ewing A.D., Ferraro T.N., Mash D.C., Kazazian H.H., Jr., Berrettini W.H. Reading LINEs within the cocaine addicted brain. Brain Behav. 2017;7:e00678. doi: 10.1002/brb3.678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Doyle G.A., Crist R.C., Karatas E.T., Hammond M.J., Ewing A.D., Ferraro T.N., Hahn C.G., Berrettini W.H. Analysis of LINE-1 elements in DNA from postmortem brains of individuals with schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2017;42:2602–2611. doi: 10.1038/npp.2017.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Guffanti G., Gaudi S., Klengel T., Fallon J.H., Mangalam H., Madduri R., Rodriguez A., DeCrescenzo P., Glovienka E., Sobell J. LINE1 insertions as a genomic risk factor for schizophrenia: Preliminary evidence from an affected family. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2016;171:534–545. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.32437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bundo M., Toyoshima M., Okada Y., Akamatsu W., Ueda J., Nemoto-Miyauchi T., Sunaga F., Toritsuka M., Ikawa D., Kakita A. Increased l1 retrotransposition in the neuronal genome in schizophrenia. Neuron. 2014;81:306–313. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.10.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shpyleva S., Melnyk S., Pavliv O., Pogribny I., Jill James S. Overexpression of LINE-1 retrotransposons in autism brain. Mol Neurobiol. 2018;55:1740–1749. doi: 10.1007/s12035-017-0421-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Payton A., Sindrewicz P., Pessoa V., Platt H., Horan M., Ollier W., Bubb V.J., Pendleton N., Quinn J.P. A TOMM40 poly-T variant modulates gene expression and is associated with vocabulary ability and decline in nonpathologic aging. Neurobiol Aging. 2016;39 doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2015.11.017. 217 e211-217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48••.Aneichyk T., Hendriks W.T., Yadav R., Shin D., Gao D., Vaine C.A., Collins R.L., Domingo A., Currall B., Stortchevoi A. Dissecting the causal mechanism of X-linked Dystonia-Parkinsonism by integrating genome and transcriptome assembly. Cell. 2018;172 doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.02.011. 897–909 e821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Intergration of molecular, genetic and clinical information to support a retrotransposon insertion is underpinning X-Linked Dystonia-Parkinsonism.

- 49.Savage A.L., Wilm T.P., Khursheed K., Shatunov A., Morrison K.E., Shaw P.J., Shaw C.E., Smith B., Breen G., Al-Chalabi A. An evaluation of a SVA retrotransposon in the FUS promoter as a transcriptional regulator and its association to ALS. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e90833. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50•.Quinn J.P., Bubb V.J. SVA retrotransposons as modulators of gene expression. Mob Genet Elements. 2014;4:e32102. doi: 10.4161/mge.32102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; The evolution of the regulatory components of the primate specific retrotransposon termed an SVA building on the function of VNTR domains.

- 51.Savage A.L., Bubb V.J., Breen G., Quinn J.P. Characterisation of the potential function of SVA retrotransposons to modulate gene expression patterns. BMC Evol Biol. 2013;13:101. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-13-101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52••.Baillie J.K., Barnett M.W., Upton K.R., Gerhardt D.J., Richmond T.A., De Sapio F., Brennan P., Rizzu P., Smith S., Fell M. Somatic retrotransposition alters the genetic landscape of the human brain. Nature. 2011 doi: 10.1038/nature10531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Evidence for somatic retrotransposition mutation in the adult CNS.

- 53.Cardelli M. The epigenetic alterations of endogenous retroelements in aging. Mech Ageing Dev. 2018 doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2018.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54•.Van Meter M., Kashyap M., Rezazadeh S., Geneva A.J., Morello T.D., Seluanov A., Gorbunova V. SIRT6 represses LINE1 retrotransposons by ribosylating KAP1 but this repression fails with stress and age. Nat Commun. 2014;5:5011. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Mechanisms which can alter retrotransposon activity in the brain directed by age and possibly nutrition.

- 55.Hancks D.C., Kazazian H.H., Jr. Roles for retrotransposon insertions in human disease. Mob DNA. 2016;7:9. doi: 10.1186/s13100-016-0065-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56•.Ewing A.D. Transposable element detection from whole genome sequence data. Mob DNA. 2015;6:24. doi: 10.1186/s13100-015-0055-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Great review of the different types of bioinformatic programmes for addressing genomic variation.

- 57.Ziats M.N., Grosvenor L.P., Rennert O.M. Functional genomics of human brain development and implications for autism spectrum disorders. Transl Psychiatry. 2015;5:e665. doi: 10.1038/tp.2015.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Owen M.J., O’Donovan M.C. Schizophrenia and the neurodevelopmental continuum: evidence from genomics. World Psychiatry. 2017;16:227–235. doi: 10.1002/wps.20440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.MacKenzie A., Quinn J.P. Post-genomic approaches to exploring neuropeptide gene mis-expression in disease. Neuropeptides. 2004;38:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.npep.2003.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gaspar P., Cases O., Maroteaux L. The developmental role of serotonin: news from mouse molecular genetics. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2003;4:1002–1012. doi: 10.1038/nrn1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bryant R.A., Edwards B., Creamer M., O’Donnell M., Forbes D., Felmingham K.L., Silove D., Steel Z., Nickerson A., McFarlane A.C. The effect of post-traumatic stress disorder on refugees' parenting and their children's mental health: a cohort study. Lancet Public Health. 2018;3:e249–e258. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(18)30051-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Eun J.D., Paksarian D., He J.P., Merikangas K.R. Parenting style and mental disorders in a nationally representative sample of US adolescents. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2018;53:11–20. doi: 10.1007/s00127-017-1435-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Warburton A., Vasieva O., Quinn P., Stewart J.P., Quinn J.P. Statistical analysis of human microarray data shows that dietary intervention with n-3 fatty acids, flavonoids and resveratrol enriches for immune response and disease pathways. Br J Nutr. 2018;119:239–249. doi: 10.1017/S0007114517003506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Marx W., Moseley G., Berk M., Jacka F. Nutritional psychiatry: the present state of the evidence. Proc Nutr Soc. 2017;76:427–436. doi: 10.1017/S0029665117002026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mac Giollabhui N., Hamilton J.L., Nielsen J., Connolly S.L., Stange J.P., Varga S., Burdette E., Olino T.M., Abramson L.Y., Alloy L.B. Negative cognitive style interacts with negative life events to predict first onset of a major depressive episode in adolescence via hopelessness. J Abnorm Psychol. 2018;127:1–11. doi: 10.1037/abn0000301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]