Key Points

Question

What are the precise localization, morphologic features, and chemical composition of calciphylaxis-related skin deposits?

Findings

This multicenter cohort study of 36 patients found that calcific uremic arteriolopathy calcifications are composed of pure calcium–phosphate apatite, always located circumferentially, mostly in the intima of otherwise normal-appearing vessels, and often associated with interstitial deposits, unlike calcifications observed in cutaneous arteriolosclerotic vessels, which are associated with medial hypertrophy containing the calcifications and no interstitial deposits.

Meaning

The differences observed between calcific uremic arteriolopathy and cutaneous arteriolosclerosis regarding calcification location and morphologic vascular features suggest different pathogenetic mechanisms and provide new insights into the pathogenesis of calcific uremic arteriolopathy that could explain the poor efficacy of vasodilators and the therapeutic effect of calcium-solubilizing drugs.

This multicenter cohort study compares skin calcium deposits from adult patients with calcific uremic arteriolopathy with specimens from control participants to characterize localization, morphologic features, and composition of cutaneous calcium deposits and identify mortality-associated factors.

Abstract

Importance

Calcific uremic arteriolopathy (CUA), a rare, potentially fatal, disease with calcium deposits in skin, mostly affects patients with end-stage renal disease who are receiving dialysis. Chemical composition and structure of CUA calcifications have been poorly described.

Objectives

To describe the localization and morphologic features and determine the precise chemical composition of CUA-related calcium deposits in skin, and identify any mortality-associated factors.

Design, Setting, and Participants

A retrospective, multicenter cohort study was conducted at 7 French hospitals including consecutive adults diagnosed with CUA between January 1, 2006, and January 1, 2017, confirmed according to Hayashi clinical and histologic criteria. Patients with normal renal function were excluded. For comparison, 5 skin samples from patients with arteriolosclerosis and 5 others from the negative margins of skin-carcinoma resection specimens were also analyzed.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Localization and morphologic features of the CUA-related cutaneous calcium deposits were assessed with optical microscopy and field-emission–scanning electron microscopy, and the chemical compositions of those deposits were evaluated with μ Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy, Raman spectroscopy, and energy dispersive radiographs.

Results

Thirty-six patients (median [range] age, 64 [33-89] years; 26 [72%] female) were included, and 29 cutaneous biopsies were analyzed. Calcific uremic arteriolopathy and arteriolosclerosis skin calcifications were composed of pure calcium–phosphate apatite. Calcific uremic arteriolopathy vascular calcifications were always circumferential, found in small to medium-sized vessels, with interstitial deposits in 22 (76%) of the samples. A thrombosis, most often in noncalcified capillary lumens in the superficial dermis, was seen in 5 samples from patients with CUA. Except for calcium deposits, the vessel structure of patients with CUA appeared normal, unlike thickened arteriolosclerotic vessel walls. Twelve (33%) patients died of CUA.

Conclusions and Relevance

Calcific uremic arteriolopathy–related skin calcifications were exclusively composed of pure calcium–phosphate apatite, localized circumferentially in small to medium-sized vessels and often associated with interstitial deposits, suggesting its pathogenesis differs from that of arteriolosclerosis. Although the chemical compositions of CUA and arteriolosclerosis calcifications were similar, the vessels’ appearances and deposit localizations differed, suggesting different pathogenetic mechanisms.

Introduction

Uremic calciphylaxis, also called calcific uremic arteriolopathy (CUA), is a rare and severely morbid condition that predominantly affects patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) receiving dialysis. Its frequency among patients with ESRD reaches 4% and its incidence increases for those on hemodialysis.1 Calcific uremic arteriolopathy’s high morbidity and mortality result from extensive skin necrosis and septic complications, with the latter being the leading cause of death. For patients with ESRD, an increased risk of subsequent CUA development has been associated with female sex, diabetes mellitus, higher body mass index, elevated serum calcium, phosphorus, and parathyroid hormone levels, nutritional status, and vitamin K-antagonist treatments.2

Although noninvasive imaging tools (eg, plain radiographs) have been reported to help diagnose CUA,3 none of those tools has been systematically evaluated.4 Definitive CUA diagnosis requires a skin biopsy. However, because biopsy of the skin is associated with the risk of new ulceration, bleeding, and infection, actually obtaining one is sometimes debated.5 When obtained, deep cutaneous biopsies of CUA lesions show calcifications, smaller than 500 μm, in hypodermal vessels, interstitial tissue or both, highly suggestive of CUA with good specificity.6

Despite well-characterized clinical and histologic descriptions of CUA, its precise pathogenetic mechanism remains unclear.7 Arteriolar calcification is probably the first event, followed by thrombosis and skin ischemia. Determination of chemical composition determination and description of the skin calcifications through physicochemical techniques could contribute to understanding CUA pathogenesis, leading to more appropriate and specific treatments.8 Nanotechnologies are receiving increased attention to improve understanding of the effects of pathologic deposits on living tissues.9,10

The aims of this study were to determine precisely the localization, morphologic features, and chemical composition of calcifications in the skin of patients with CUA, and then examine whether any association could be established between their microscopy findings and clinical characteristics.

Methods

This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline. This study was conducted in compliance with Good Clinical Practices and the Declaration of Helsinki,11 and in accordance with French law. Formal ethics committee approval of the study protocol was obtained. Patients provided written informed consent.

Case Selection and Histopathologic Analyses

This retrospective study included consecutive adults diagnosed with CUA, confirmed according to Hayashi clinical and histologic criteria, and seen in 7 French hospitals between January 1, 2006, and January 1, 2017.12 Patients with normal renal function were excluded. Patients’ medical histories, treatments, and laboratory findings were extracted from their medical records. They were classified into 2 clinical subgroups, distal or proximal CUA, according to the skin lesion localizations described by Brandenburg et al.13

Five skin samples from patients with arteriolosclerosis and 5 control samples from the negative margins of skin carcinoma resections on the legs of 5 other patients were included and served as controls. All 10 control participants had normal renal function; only the 5 patients with arteriolosclerosis from among a cohort of patients with necrotic angiodermatitis underwent leg-skin biopsies.

Skin biopsy samples were sent to and centralized in Tenon Hospital, Department of Pathology. For each subject, 1.5-μm–thick sections of paraffin-embedded skin biopsy specimens were deposited on glass slides, for hematoxylin-eosin–saffron and von Kossa staining, and low-e microscope slides (MirrIR, Kevley Technologies, Tienta Sciences) for field-emission–scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM), μ Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy, and Raman spectroscopy.14 Vascular and interstitial calcifications, the caliber of calcified vessels, and the topography of deposits in skin sections were analyzed and compared between patients with CUA and control participants.

Field-Emission–Scanning Electron Microscopy

Field-emission–scanning electron microscopy (Zeiss SUPRA55-VP) was used to describe the ultrastructural characteristics of tissue sections. As previously described, high-resolution images were obtained with in-lens and Everhart-Thornley secondary electron detectors.15 Measurements were taken at low voltage (1–2 kV), without the usual carbon-coating of the sample surface. For some samples, energy-dispersive radiography (EDX) was also used to identify calcium in the abnormal deposits.

μ Fourier Transform Infrared and Raman Spectroscopies

Using the same sample as for FE-SEM analyses, FT-IR and Raman spectroscopies identified the chemical compositions of the CUA calcifications. All the FT-IR hyperspectral images were recorded with a Spectrum Spotlight 400 FT-IR imaging system (Perkin–Elmer Life Sciences), with 6.25-mm spatial resolution and 8-cm–1 spectral resolution.16 Raman spectra were collected with a micro-Raman system (LabRam HR-800 Evolution) using 785-nm laser excitation wavelength, 100 × objective (Olympus, numerical aperture, 0.9) and 300 grooves per millimeter grating. Spectra were corrected at baseline to suppress the strong luminescence background.17

Statistical Analyses

Data are expressed as median (range) or number (%). Fisher exact or χ2 tests were used to compare qualitative variables; Wilcoxon rank sum or Mann-Whitney tests were used to compare paired variables; and Mann-Whitney tests were used to compare nonpaired or non–normally distributed variables. Parameters with P < .20 in univariate analysis were entered into a multivariate logistic-regression model, with Y as the dependent variable. Two-tailed P <.05 was considered statistically significant Analyses were performed with JMP version 13 (SAS Institute. Inc).

Results

Clinical and Histopathologic Findings

Among the 36 patients with CUA, median (range) age was 64 (33-89) years and 26 (72%) were female. No data on race/ethnicity were collected. Twenty-nine skin biopsies could be analyzed by optical microscopy, FE-SEM, and spectroscopies. Clinical and histopathologic data are summarized in the Table.

Table. Baseline Clinical, Biological, and Histologic Characteristics of 36 Patients With CUA.

| Characteristic | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | |

| Female to male ratio | 2.6 |

| Age at diagnosis, median (range), y | 64 (33-89) |

| Comorbidities | |

| Dialysis | 30 (83) |

| Dialysis-to-CUA interval, median (range), mo | 24 (1-156) |

| Diabetes | 23 (64) |

| Hypertension | 33 (92) |

| BMI >30 kg/m2 | 14 (39) |

| Vitamin K antagonists | 16 (44) |

| Clinical characteristics | |

| Proximal CUA | 10 (28) |

| Necrosis | 26 (72) |

| Ulceration | 24 (67) |

| Livedo reticularis | 18 (50) |

| Indurated plaques | 15 (42) |

| Nodular lesions | 9 (25) |

| Biological characteristics | |

| Serum calcium, median (range), mmol/L | 2.26 (1.89-2.84) |

| Serum phosphate, median (range), mmol/L | 1.57 (0.93-3.68) |

| Calcium × phosphate product >4.5 mmol2/L2 | 12 (33) |

| Serum parathyroid hormone >90 ng/L | 24 (67) |

| Serum albumin, median (range), g/L | 28 (18-37) |

| Cutaneous histologic features | 29 |

| Vascular calcifications | 29 (100) |

| Interstitial calcifications | 22 (76) |

| Thrombosis | 5 (14) |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); CUA, calcific uremic arteriolopathy.

Conversion factors: To convert mmol/L to mg/dL, divide by 0.25; to convert ng/L to pg/mL, divide by 1.0; to convert g/L to g/dL, divide by 10.

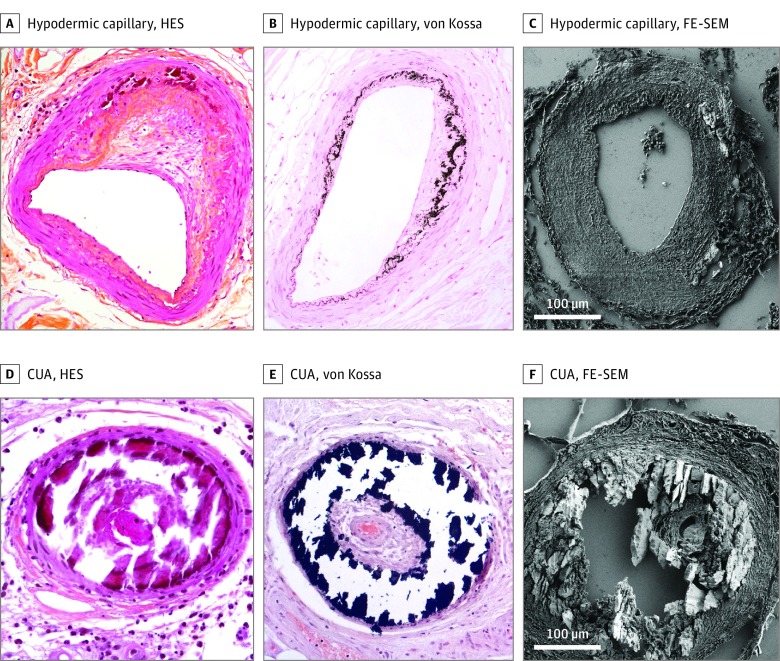

Optical microscopy analysis of hematoxylin-eosin-saffron– and von Kossa–stained CUA biopsy specimens always found calcifications in small and medium-sized vessels (diameter, 10-300 μm), mostly in hypodermal arterioles and capillaries (Figure 1). These deposits occupied the entire circumference of the vessel and were located in the intima and sometimes the media. They could be associated with intimal fibrous or myxoid changes.

Figure 1. Skin Biopsy Sections.

Arteriolosclerosis with asymmetrical fibrous intimal thickening (fibrous endarteritis) and Mönckeberg medial calcinosis (calcification of the internal elastic lamina and media): A, Hematoxylin-eosin-saffron (HES)–stained (original magnification ×400); B, von Kossa–stained (original magnification ×400); C, Field-emission–scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM). Calcific uremic arteriolopathy (CUA) hypodermic arterioles with voluminous and circumferential parietal calcium deposits: D, HES-stained (original magnification ×400); E, von Kossa–stained (original magnification ×400); F, FE-SEM.

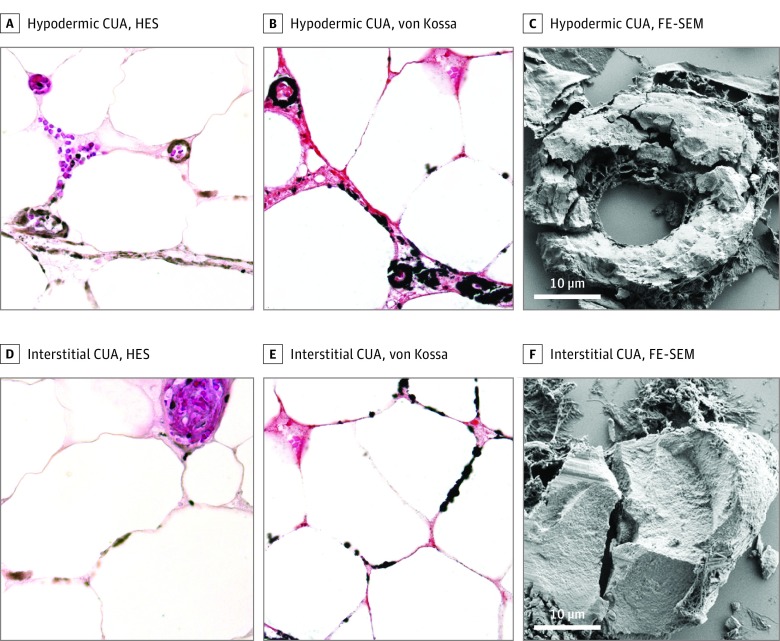

Those CUA vascular calcifications were associated with interstitial deposits, mainly localized to the hypodermis, in 22 (76%) of the samples. Calcification size ranged from 1 to 500 μm, sometimes becoming confluent, with clusters reaching several millimeters in diameter. They were either isolated, small clusters between adipocytes (Figure 2A and B) or aligned in a “pearl collar” along the cytoplasmic membranes of adipocytes (Figure 2D and E). Calcified elastic fibers, collagen fibers, or both were also seen in hypodermic septa or deep dermis. Thromboses were seen in 5 samples (17%), most often in noncalcified capillaries in the superficial dermis.

Figure 2. Skin Biopsy Sections.

Calcific uremic arteriolopathy (CUA) hypodermic capillaries with voluminous and circumferential parietal calcium deposits: A, hematoxylin-eosin-saffron (HES)–stained (×400), B, von Kossa-stained (original magnification ×400); C, Field-emission–scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM). Interstitial calcific uremic arteriolopathy (CUA) deposits, aligned along the cytoplasmic membranes of adipocytes; D, HES-stained (original magnification ×400); E, von Kossa–stained (original magnification ×400); F, FE-SEM.

The 5 arteriolosclerosis-control biopsy specimens showed classic intimal fibrous endarteritis and Mönckeberg medial calcinosis associated with calcium deposits that were localized within the media along the internal elastic lamina. Those calcifications were never circumferential and no interstitial localization was observed. Negative margins of resected carcinomas contained no vascular or interstitial calcium deposits.

Twelve patients (33%) died of CUA. Poorer CUA prognosis was only associated with male sex (10 patients; P = .02) or nodular lesions (9 patients; P = .04) (eTable in the Supplement).

FE-SEM and Energy-Dispersive Radiograph Analyses

Subcellular calcification localization and morphologic features were assessed with FE-SEM. Vascular deposits of CUA were circumferential (Figure 1F and-Figure2C); at least 1 thrombosis in 5 of the 29 samples was located in the vessel lumen or intima, whereas the media usually appeared normal with rare calcifications. Interstitial deposits surrounded adipocytes, along the cell membranes. Morphologically, these calcifications appeared to be composed of aggregated micrometric plates (Figure 2F).

Field-emission–scanning electron microscopy analyses of control skin biopsies showing arteriolosclerosis contained vascular calcifications in the media (Figure 1C), associated with medial hypertrophy and intimal fibrosis; no interstitial deposits were seen. Field-emission–scanning electron microscopy analyses of negative resected carcinoma margins confirmed the absence of vascular and interstitial deposits.

Energy-dispersive radiograph analyses of CUA samples verified the calcium and phosphate composition of vascular and interstitial deposits, with similar calcium to phosphate ratios in both sites. Energy-dispersive radiograph analyses showed the composition of vascular deposits in control arteriolosclerosis biopsies to be similar to that found in CUA.

Spectroscopic Analyses

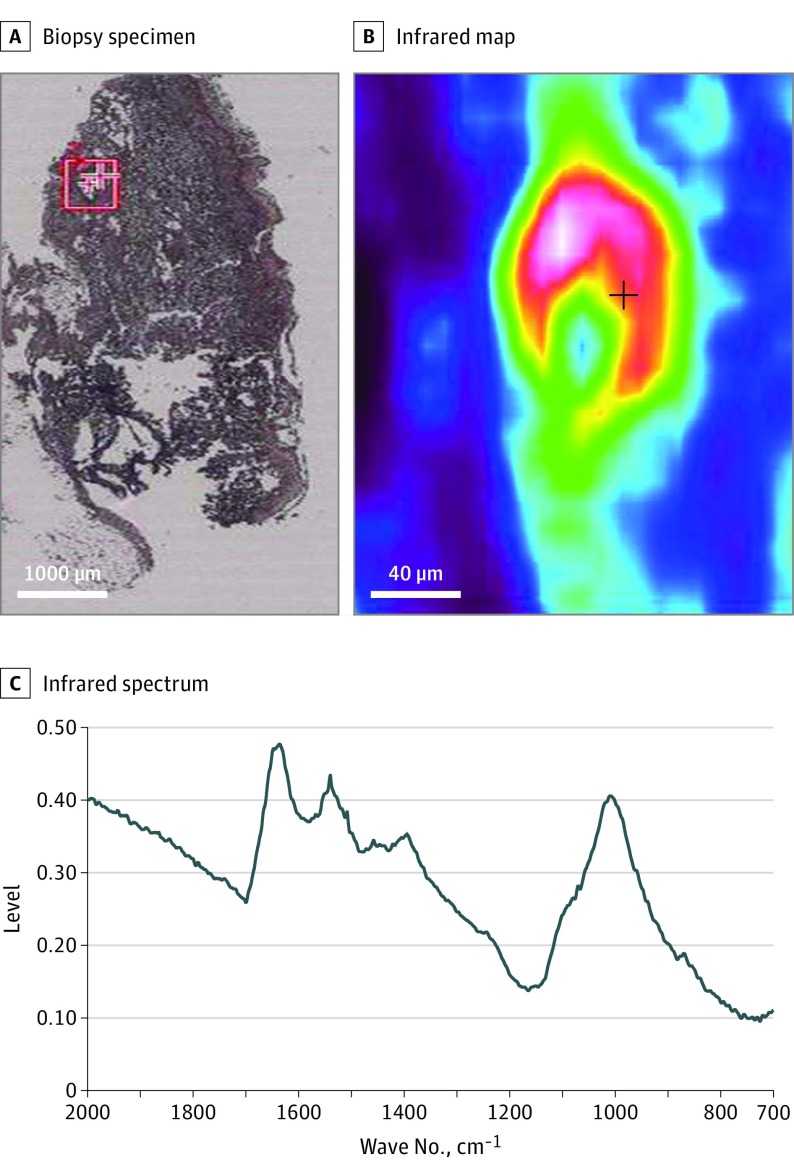

μ Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) analyses of CUA and arteriolosclerosis skin calcifications showed that all were composed of calcium–phosphate apatite (Figure 3). Careful examination of 3 CUA samples identified the presence of amorphous carbonated calcium–phosphate associated with calcium–phosphate apatite that was not seen in any samples from patients with arteriolosclerosis.

Figure 3. μ Fourier Transform Infrared (FT-IR) Spectroscopy of the Interstitial Calcific Uremic Arteriolopathy (CUA) Deposits.

A, Skin biopsy of CUA; B, Infrared map of the red square area, showing an intense vascular deposit; C, Infrared spectrum of this vascular deposit: calcium–phosphate apatite spectrum with characteristic peaks (1009, 958 and 870 cm–1) in a protein matrix (skin tissue). The same spectrum was obtained for CUA and arteriolosclerosis vascular calcifications.

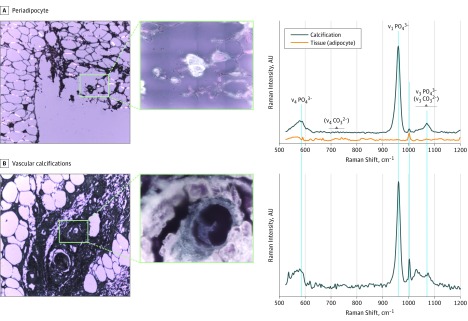

Raman spectroscopy confirmed the similar calcium–phosphate-apatite compositions of vascular and interstitial calcifications (Figure 4).17

Figure 4. Micro-Raman Signatures and Optical Micrographs of Periadipocyte and Vascular Calcifications.

Micrographs (original magnifications ×10 and ×100) of (A) Periadipocyte and (B) Vascular calcifications (excitation wavelength λexc = 785 nm; numerical aperture, 0.9). The Raman bands at 960, 1076, and 590 cm–1 correspond, respectively, to the ν1, ν3 and ν4 phosphate vibrations of apatite. The low-intensity ν4 carbonate vibrations around 680 to 715 cm–1, expected for carbapatite, are not observed. The strong fluorescence background has been corrected on the presented spectra.

Discussion

These FE-SEM, EDX, and spectroscopic analyses were able to finally specify the localization and the complete chemical composition of skin calcifications in patients with CUA. Our spectroscopic analyses demonstrated that those circumferential calcifications, located in the intima and media of skin vessels in patients with CUA, were composed exclusively of calcium–phosphate apatite. In 22 (76%) of these samples, calcium–phosphate apatite was also found in interstitial tissue of the deep dermis and hypodermis, along the cytoplasmic membranes of adipocytes, and elastic and collagen fibers.

The chemical composition and localization of cutaneous CUA calcifications have been investigated in only a few small series. Using EDX and FE-SEM, Kramann et al18 found calcium/phosphate accumulations, with a molar ratio matching that of hydroxyapatite, in the hypodermis of 7 patients with CUA. Two other studies used mass spectrometry and Raman spectroscopy to detect and characterize CUA skin calcifications. Using mass spectrometry, Amuluru et al19 showed that tissue samples from 12 CUA patients had high iron and aluminum contents, suggesting a role of metal deposition in CUA pathogenesis. Using microcomputed-tomography and Raman spectroscopy, Lloyd et al20 confirmed the presence carbonated apatite in debrided CUA tissues from 6 patients. However, those studies included small numbers of samples and performed only chemical analyses. To the best of our knowledge, the precise localization and exact morphologic features of these abnormal deposits have not yet been reported.

Patients with proximal lesions, body mass index greater than 30, ulcerated lesions, and female sex were reported to have poorer prognoses.21 Our univariate and multivariate analyses did not identify those factors as having a relationship with shorter survival, and retained only male sex and nodular lesions as being significantly associated with mortality. However, the relatively small number of patients included makes those findings less relevant than risk factors identified in larger studies.

Skin deposits in patients with CUA or arteriolosclerosis were always composed of calcium–phosphate apatite, but their different localizations in the vessel walls could indicate different pathogenetic mechanisms. Indeed, arteriolosclerotic vessel walls are thickened, with media hypertrophy, suggestive of slowly progressive thickening and degeneration of the arteriolar wall with secondary calcium–phosphate apatite accumulation. Circumferential CUA vascular deposits were located mostly in the intima of otherwise normal-appearing vessels, suggesting a faster and global process, with primary calcium deposition.

Ellis et al recently showed that pathognomonic cutaneous calcifications associated with CUA could also occur in viable tissue from patients with ESRD who did not have CUA, amputated because of peripheral arterial disease.22,23 However, Ellis et al did not consider that some of their controls might have had undiagnosed acral calciphylaxis and undergone amputations for distal ischemia. Those possibilities might explain some of their histopathologic observations of calciphylaxis in their controls. Our histologic findings (circumferential calcifications of small to medium-sized vessels often associated with interstitial calcifications) and high-technology tools, such as FE-SEM, enabled us to demonstrate several differences between the vascular calcifications seen in CUA and arteriolosclerosis, thereby confirming our previous results and those of Chen et al.6,24

Patients with calciphylaxis probably develop skin calcifications subsequent to a disequilibrium between calcification promoters and inhibitors. Calcium-inhibitor deficiency, such as matrix Gla protein, impaired inhibition of calcium–phosphate precipitation, thereby leading to skin calcifications.21

Chronic inflammatory states, including ESRD, are associated with increased levels of reactive oxygen species that impair endothelial function.25 ESRD-related endothelial dysfunction engenders vessel-wall abnormalities, including the presence of bone morphogenetic protein in medial and intimal layers.26 Such vascular protein modification, associated with increased calcium × phosphate products, might explain the intimal and medial calcifications observed in CUA.

Interstitial calcifications were also seen in 22 (76%) of CUA samples. Voluminous calcifications of the subcutaneous tissue or dystrophic and metastatic calcinosis cutis are known to occur in a variety of disorders, including dermatomyositis, lupus, or trauma. The ectopic calcified masses, composed of hydroxyapatite and amorphous calcium–phosphate apatite, were disseminated throughout the dermis and hypodermis that appeared petrified, involving interstitial tissue and vessels.27 The pathophysiologic development is still unclear but it has been hypothesized that hypodermal inflammation might release the phosphate bound to denatured proteins and serve as a niche for ectopic calcifications.27 However, despite clinical and pathologic differences, the physiology of these calcifying disorders might be similar, and calcium deposits obstructing some hypodermis vessels in CUA might lead to detrimental adipocyte, collagen and elastic fiber alterations, and the release of the phosphate bound to denatured proteins and ectopic interstitial calcifications. According to that hypothesis, interstitial calcifications might be a secondary phenomenon, thereby explaining the inconstant interstitial localization. The constant presence of vascular deposits could suggest a primary vascular trigger of CUA.

Our finding that CUA vascular calcifications were always circumferential suggests that therapeutic strategies with vasodilators might be less relevant than those using calcium-solubilizing drugs. Therefore, drugs that act on calcium–phosphate precipitation, such as sodium thiosulfate, bisphosphonates, and vitamin K supplements, would seem to be more appropriate and a rational approach for future therapeutic studies on CUA.27,28 Along the same line, Dedinszki et al,29 who studied other calcifying disorders, including pseudoxanthoma elasticum and generalized arterial calcifications of infancy, reported that oral pyrophosphate inhibited tissue calcifications.30

Limitations

Because our study was retrospective, some information, including vital status, was missing for some patients. Our failure to identify factors associated with greater mortality in larger studies might be explained by the relatively small size of our series. It is worth highlighting that morphologic features of calcification can be modified by sectioning paraffin-embedded skin biopsy specimens and that the appearance of these deposits may differ between glass and low-e slides, making it more difficult to discern the association between optical microscopy and electronic microscopy.

Conclusions

Our histologic, FE-SEM, EDX, and spectroscopy results provide a better understanding of the morphologic, ultrastructural, and chemical characteristics of skin calcium–phosphate-apatite deposits in patients with CUA. Those deposits appear to be initially vascular and develop rapidly in normal vessel walls. Circumferential vascular and interstitial deposits, albeit inconstant, were specific to CUA. Although the chemical compositions of the calcifications were similar in CUA and arteriolosclerosis, the vessels’ appearances and deposit localizations differed, suggesting different pathogenetic mechanisms.

eTable. Univariate and Multivariate Analyses for the Risk of Death Related to CUA

References

- 1.Weenig RH, Sewell LD, Davis MD, McCarthy JT, Pittelkow MR. Calciphylaxis: natural history, risk factor analysis, and outcome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56(4):569-579. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.08.065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nigwekar SU, Zhao S, Wenger J, et al. A nationally representative study of calcific uremic arteriolopathy risk factors. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;27(11):3421-3429. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2015091065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shmidt E, Murthy NS, Knudsen JM, et al. Net-like pattern of calcification on plain soft-tissue radiographs in patients with calciphylaxis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67(6):1296-1301. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2012.05.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Halasz CL, Munger DP, Frimmer H, Dicorato M, Wainwright S. Calciphylaxis: comparison of radiologic imaging and histopathology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77(2):241-246.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.01.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nigwekar SU, Kroshinsky D, Nazarian RM, et al. Calciphylaxis: risk factors, diagnosis, and treatment. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;66(1):133-146. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.01.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cassius C, Moguelet P, Monfort JB, et al. Calciphylaxis in haemodialysed patients: diagnostic value of calcifications in cutaneous biopsy. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178(1):292-293. doi: 10.1111/bjd.15655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jean G, Terrat JC, Vanel T, et al. Calciphylaxis in dialysis patients: to recognize and treat it as soon as possible[in French]. Nephrol Ther. 2010;6(6):499-504. doi: 10.1016/j.nephro.2010.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bazin D, Daudon M, Combes C, Rey C. Characterization and some physicochemical aspects of pathological microcalcifications. Chem Rev. 2012;112(10):5092-5120. doi: 10.1021/cr200068d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Colboc H, Moguelet P, Bazin D, et al. Physicochemical characterization of inorganic deposits associated with granulomas in cutaneous sarcoidosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019;33(1):198-203. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bazin D, Daudon M. Pathological calcifications and selected examples at the medicine–solid-state physics interface. J Phys Appl Phys. 2012;45(38):383001. doi: 10.1088/0022-3727/45/38/383001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Medical Association World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310(20):2191-2194. . doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hayashi M. Calciphylaxis: diagnosis and clinical features. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2013;17(4):498-503. doi: 10.1007/s10157-013-0782-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brandenburg VM, Cozzolino M, Ketteler M. Calciphylaxis: a still unmet challenge. J Nephrol. 2011;24(2):142-148. doi: 10.5301/JN.2011.6366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dessombz A, Bazin D, Dumas P, Sandt C, Sule-Suso J, Daudon M. Shedding light on the chemical diversity of ectopic calcifications in kidney tissues: diagnostic and research aspects. PLoS One. 2011;6(11):e28007. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brisset F. Microscopie Électronique à Balayage et Microanalyses. Paris, France: EDP Sciences; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carden A, Morris MD. Application of vibrational spectroscopy to the study of mineralized tissues (review). J Biomed Opt. 2000;5(3):259-268. doi: 10.1117/1.429994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Awonusi A, Morris MD, Tecklenburg MM. Carbonate assignment and calibration in the Raman spectrum of apatite. Calcif Tissue Int. 2007;81(1):46-52. doi: 10.1007/s00223-007-9034-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kramann R, Brandenburg VM, Schurgers LJ, et al. Novel insights into osteogenesis and matrix remodelling associated with calcific uraemic arteriolopathy. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2013;28(4):856-868. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfs466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Amuluru L, High W, Hiatt KM, et al. Metal deposition in calcific uremic arteriolopathy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61(1):73-79. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.01.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lloyd WR, Agarwal S, Nigwekar SU, et al. Raman spectroscopy for label-free identification of calciphylaxis. J Biomed Opt. 2015;20(8):80501. doi: 10.1117/1.JBO.20.8.080501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nigwekar SU, Thadhani R, Brandenburg VM. Calciphylaxis. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(18):1704-1714. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1505292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ellis CL, O’Neill WC. Questionable specificity of histologic findings in calcific uremic arteriolopathy. Kidney Int. 2018;94(2):390-395. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2018.03.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nigwekar SU, Nazarian RM. Cutaneous calcification in patients with kidney disease is not always calciphylaxis. Kidney Int. 2018;94(2):244-246. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2018.04.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen TY, Lehman JS, Gibson LE, Lohse CM, El-Azhary RA. Histopathology of calciphylaxis; cohort study with clinical correlations. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39(11):795-802. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0000000000000824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sowers KM, Hayden MR. Calcific uremic arteriolopathy: pathophysiology, reactive oxygen species and therapeutic approaches. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2010;3(2):109-121. doi: 10.4161/oxim.3.2.11354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nigwekar SU, Jiramongkolchai P, Wunderer F, et al. Increased bone morphogenetic protein signaling in the cutaneous vasculature of patients with calciphylaxis. Am J Nephrol. 2017;46(5):429-438. doi: 10.1159/000484418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reiter N, El-Shabrawi L, Leinweber B, Berghold A, Aberer E. Calcinosis cutis: part I: diagnostic pathway. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65(1):1-12. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.08.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zitt E, König M, Vychytil A, et al. Use of sodium thiosulphate in a multi-interventional setting for the treatment of calciphylaxis in dialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2013;28(5):1232-1240. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfs548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dedinszki D, Szeri F, Kozák E, et al. Oral administration of pyrophosphate inhibits connective tissue calcification. EMBO Mol Med. 2017;9(11):1463-1470. doi: 10.15252/emmm.201707532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nigwekar SU, Bloch DB, Nazarian RM, et al. Vitamin K-dependent carboxylation of matrix Gla protein influences the risk of calciphylaxis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28(6):1717-1722. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2016060651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable. Univariate and Multivariate Analyses for the Risk of Death Related to CUA