Key Points

Question

Are trauma registries effective in capturing, tracking, and evaluating injured older adults?

Findings

In this cohort study of 8161 injured adults 65 and older transported by 44 emergency medical services agencies to 51 hospitals in Oregon and Washington, trauma registries missed 93 of 188 in-hospital deaths (49.5%), 178 of 553 patients with serious injuries (32.2%), and 68 of 186 patients requiring major nonorthopedic surgery (36.6%). When registry and nonregistry cohorts were tracked over 1 year, 1531 of 1887 deaths after injury (81.1%) occurred in the nonregistry group.

Meaning

Trauma registries are ineffective data sources for studying injured older adults, including those with serious injuries, requiring major surgery, or dying after injury.

This cohort study evaluates patient characteristics, injury patterns, surgical interventions, mortality, and causes of death up to 1 year after the index event among injured older adults who were included in compared with those who were excluded from trauma registries.

Abstract

Importance

Trauma registries are the primary data mechanism in trauma systems to evaluate and improve the care of injured patients. Research has suggested that trauma registries may miss high-risk older adults, who commonly experience morbidity and mortality after injury.

Objective

To compare injured older adults who were included in with those excluded from trauma registries, with a focus on patients with serious injuries, requiring major surgery, or dying after injury.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This cohort study included all injured adults 65 years and older transported by 44 emergency medical services agencies to 51 trauma and nontrauma centers in 7 counties in Oregon and Washington from January 1, 2011, to December 31, 2011, with follow-up through December 31, 2012. Record linkage was used to match emergency medical services records with state trauma registries, state discharge databases, state death registries, and Medicare claims. Data were analyzed from August to November 2018.

Exposures

Inclusion in vs exclusion from a trauma registry.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Mortality up to 12 months, including time to death and causes of death.

Results

Of 8161 included patients, 5579 (68.4%) were women, and the mean (SE) age was 82.2 (0.10) years. A total of 1720 older adults (21.1%) were matched to a trauma registry record. Seriously injured patients not captured by trauma registries ranged from 18% (7 of 38 patients with abdominal-pelvic Abbreviated Injury Scale score of 3 or greater) to 80.0% (1792 of 2241 patients with extremity Abbreviated Injury Scale score of 3 or greater), while 68 of 186 patients requiring major nonorthopedic surgery (36.6%) and 1809 of 2325 patients requiring orthopedic surgery (77.8%) were not included in trauma registries. Of patients with serious injuries or undergoing major surgery missed by trauma registries (range by injury and procedure type, 36.0% to 57.1%), 36.4% (39.3% when excluding serious extremity injuries and orthopedic procedures) were treated at trauma centers, particularly level III through V hospitals. When registry and nonregistry groups were tracked over 12 months, 93 of 188 in-hospital deaths (49.5%) and 1531 of 1887 total deaths (81.1%) occurred in the nonregistry cohort.

Conclusions and Relevance

In their current form, trauma registries are ineffective in capturing, tracking, and evaluating injured older adults, although mortality following injury is frequently due to noninjury causes. High-risk injured older adults are not included in registries because of care in nontrauma hospitals, restrictive registry inclusion criteria, and being missed by registries in trauma centers.

Introduction

Trauma systems function as critical, coordinated, regionalized systems of care for injured patients. Trauma registries provide the data to evaluate and improve these systems, including quality assurance, gaps in care, and outcomes. For decades, trauma registries have served as the backbone for data-driven quality improvement and research in trauma systems. More recently, the American College of Surgeons has standardized inclusion criteria and data definitions for trauma registries1 and has developed a national program for using these data to benchmark trauma centers and improve the quality and consistency of trauma care.2 To be included in a trauma registry, an injured patient must be admitted, transferred to, or die in a trauma center.1 Some hospitals further restrict their registries to patients with a minimum level of injury severity, and many registries exclude patients with certain types of injuries (eg, older adults with an isolated hip fracture). The inclusion criteria seek to balance the resources required to support continuous data collection with the usefulness of these data. It is assumed that trauma registries capture the overwhelming majority of high-risk trauma patients.

A 2017 study3 suggested that the standardized inclusion criteria for trauma registries miss a portion of patients with serious injuries, requiring critical interventions, or dying in the hospital after injury, most of whom are older adults. However, this research was limited to events during hospitalization, used a probability sample, lacked preinjury information, and was based on standard registry inclusion criteria rather than actual registry matches. Because injured older adults are a population at high risk of functional decline, loss of independence, and mortality after injury,4,5,6,7 we sought to focus on older adults as a potential blind spot in trauma data systems.

In this study, we analyzed injured older adults transported by 44 emergency medical services (EMS) agencies to 51 diverse hospitals and compared patients who were included in with those excluded from trauma registries for patient characteristics, injury patterns, surgical interventions, mortality, and causes of death up to 1 year after the index event. This analysis extends previous work3 by focusing on injured older adults, using a larger sample size, using matches to actual trauma registry records, and analyzing outcomes up to 1 year. We address whether trauma registries provide an effective mechanism for studying the care of injured older adults, including key recommendations from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine report on trauma data systems.8

Methods

Study Design

This cohort study was reviewed and approved by the Oregon Health & Science University institutional review board and additional institutional review boards at the institution and state level, who waived the requirement for informed consent. We followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline for cohort studies.9

Study Setting

We conducted the study in 7 counties in Oregon and Washington, including 2 major metropolitan areas (Portland, Oregon, and Seattle, Washington). The counties included urban, suburban, rural, and frontier settings served by 44 public and private EMS agencies. Oregon and Washington have established, inclusive trauma systems, with participating hospitals categorized as level I through V trauma centers, and statewide trauma registries. We included all 51 hospitals receiving injured older adults from EMS, plus 6 additional hospitals receiving these patients as subsequent interhospital transfers. The 57 hospitals have varying capabilities and services and included 3 level I trauma centers, 7 level II trauma centers, 10 level III trauma hospitals, 9 level IV hospitals, 1 level V hospital, and 27 nontrauma hospitals. The 2 level I hospitals and 1 level II hospital in Oregon are verified by the American College of Surgeons. The remainder of trauma centers in Oregon and all trauma centers in Washington are state verified and follow the American College of Surgeons verification criteria.

Patient Population

We included consecutive injured adults 65 years and older transported by EMS from January 1, 2011, through December 31, 2011 (with follow-up through December 31, 2012), who matched a record from Oregon or Washington statewide trauma registries, statewide inpatient data, statewide death registries, or Medicare claims data. Patients were included regardless of receiving hospital, injury severity, or admission status. We limited the sample to patients that matched a clinical record (trauma registry or other) to avoid comparing registry patients with unmatched patients and to ensure comprehensive hospital and outcome data. We also excluded patients with no documented International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) injury diagnosis for the index visit (eFigure in the Supplement).

Data Processing

We collected EMS data as part of a prospective, all-age cohort study validating the national field triage guidelines in these counties.10 We then used probabilistic linkage11 using LinkSolv version 9.0.0190 (Strategic Matching) to match multiple electronic EMS records for the same patient (generating a patient-level data set), to self-match all other data sources (identifying repeated visits over time for the same patient), and then to link the patient-level EMS data with records from state trauma registries, state discharge databases, state death registries, and Medicare claims data. We have validated the electronic data processing methods used in the study,12 probabilistic linkage routines,13,14,15 multiple imputation models,15,16 and development of key variables.15 Using 1350 randomly sampled records that underwent manual record review, sensitivity of probabilistic linkage was 98.3% (95% CI, 96.2-99.4) for state discharge matches and 98.8% (95% CI, 95.6-99.9) for trauma registry matches, and specificity of probabilistic linkage was 100% (95% CI, 99.2-100) for state discharge matches and 97.6% (95% CI, 87.4-99.9) for trauma registry matches.15

Variables

The primary exposure was a match to a trauma registry record. This comparison provided a real-world look at the type of patients captured in trauma registries compared with excluded patients. Oregon and Washington have similar inclusion criteria for their state trauma registries17,18 and do not require older adults with an isolated hip fracture to be included. We coded out-of-hospital variables based on standardized definitions from the National EMS Information System,19 including age, sex, field triage status, rural vs urban county of EMS response, initial physiologic measures (Glasgow Coma Scale score, systolic blood pressure, respiratory rate, and heart rate), mechanism of injury, procedures, mode of transport, and initial receiving hospital.

Variables from the index emergency department or hospital visit included Abbreviated Injury Scale (AIS) scores,20 Injury Severity Scores (ISSs),20,21 ICD-9-CM diagnosis code categories, ICD-9-CM procedure codes (categorized using the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Clinical Classification System22), interhospital transfer, length of hospital stay, and hospital discharge disposition (including mortality). We used a mapping function (ICDPIC module for Stata version 11 [StataCorp]) to convert ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes into AIS and ISS measures,17 which has been validated.23 For consistency in comparing injury severity between the groups, we only used ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes to generate AIS scores and ISSs rather than abstracted values that were only available for registry patients. For hospital procedures, we combined Clinical Classification System categories into major nonorthopedic procedures (ie, brain, spine, neck, chest, and abdominal-pelvic operations), orthopedic procedures (ie, orthopedic operations), and blood transfusions. Finally, we calculated the Charlson Comorbidity Index score24 and the modified Frailty Index score25 using information prior to EMS contact from Medicare and other record sources. For information on race/ethnicity, we used Medicare, discharge data, and trauma registry data.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was mortality, tracked for 1 year from the date of EMS contact, including cause of death. Secondary outcomes included ISS of 16 or greater, any serious injury (AIS score of 3 or greater in the head, chest, abdominal-pelvic, or extremity regions), major nonorthopedic surgery, and orthopedic surgery. Among patients who died following injury, we compared causes of death using ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes grouped using the standard ICD-9 categorization schema26 and further categorized into 14 clinically relevant categories. To account for all contributing factors and potential variability in the completion of death certificates, we considered all causes of death (primary and contributing).

Statistical Analysis

We used descriptive statistics to characterize patients, injury severity, interventions, and mortality up to 12 months for those with a matched trauma registry record and those with no matched trauma registry record. We plotted Kaplan-Meier survival curves to compare unadjusted differences in time to death between the groups, including 95% CIs, and the log-rank test, with a 2-sided P value less than .05 considered statistically significant. To handle missing values and minimize bias, we used multiple imputation.27 We have demonstrated the validity of multiple imputation for handling missing trauma data in previous studies16,28 and in this sample.15 We generated 10 multiply imputed data sets using flexible chains regression models29 using IVEware version 0.1 (University of Michigan), then combined the results using Rubin rules to account for overall variance.27 There were no missing data for mortality up to 1 year, trauma registry match status, or AIS scores. Most other variables had 5% or less missingness, except for hospital disposition (7.1% missing), physiologic measures (5.8% [heart rate] to 26.9% [Glasgow Coma Scale score] missing), modified Frailty Index score (13.5% missing), Charlson Comorbidity Index score (13.5% missing), and ethnicity (31.3% missing). We used SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute) for all analyses.

Results

Of the 15 649 injured older adults transported by 44 EMS agencies during the 12-month study period, 8161 had a matched clinical record from the index event and a confirmed injury diagnosis, forming the primary sample (eFigure in the Supplement). In eTable 1 in the Supplement, we compare characteristics of included patients with those of excluded patients. Among the 8161 included patients, 1720 (21.1%) were matched to a trauma registry record. In the Table, we compare patients with a matched trauma registry record with those with no matched trauma registry record. Injured older adults captured in trauma registries tended to be younger; had lower comorbidity burden, less frailty, greater physiologic compromise, higher injury severity, and longer hospital stays; and required more nonorthopedic procedures. Falls were the most frequent mechanism of injury in both groups, although the trauma registry group had more patients injured by nonfall mechanisms. A total of 2683 of 6441 injured older adults not included in trauma registries (41.7%) were initially transported to a trauma center. The percentage of patients with extremity AIS scores of 3 or greater and orthopedic surgeries were similar between the groups. Of the 2241 patients with a serious extremity injury, 1932 (86.2%) were femoral neck fractures (eTable 2 in the Supplement). While trauma registry patients had higher mortality through 90 days, 1-year mortality was higher among nonregistry patients.

Table. Characteristics of Injured Older Adults Transported by Emergency Medical Services (EMS).

| Characteristic | No. (%) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Matched Trauma Registry Record (n = 1720) | No Matched Trauma Registry Record (n = 6441) | ||

| Demographic Characteristics | |||

| Age, mean (SE), ya | 80.5 (0.22) | 82.6 (0.11) | <.001 |

| Women | 1032 (60.0) | 4547 (70.6) | <.001 |

| Race | |||

| White | 1578 (91.7) | 5981 (92.9) | <.001 |

| Black | 38 (2.2) | 119 (1.9) | |

| Asian | 87 (5.1) | 213 (3.3) | |

| Native American | 6 (0.4) | 38 (0.6) | |

| Other | 11 (0.7) | 90 (1.4) | |

| Latino | 43 (2.5) | 123 (1.9) | .21 |

| Preinjury comorbidities and frailty | |||

| Charlson Comorbidity Index score, mean (SE)a | 2.1 (0.06) | 2.9 (0.04) | <.001 |

| Modified Frailty Index score, mean (SE)a | 1.7 (0.04) | 2.2 (0.03) | <.001 |

| Out-of-hospital characteristics | |||

| Met field triage criteria per EMS | 1240 (72.1) | 158 (2.5) | <.001 |

| SBP ≤100 mm Hg | 99 (5.8) | 269 (4.2) | <.001 |

| Respiratory rate ≤10 or ≥24 breaths per min | 186 (10.8) | 354 (5.5) | <.001 |

| GCS score ≤8 | 50 (2.9) | 8 (0.1) | <.001 |

| Assisted ventilation | 40 (2.3) | 22 (0.3) | <.001 |

| Mechanism of injury | |||

| Fall | 1412 (82.1) | 5803 (90.1) | <.001 |

| Motor vehicle crash | 195 (11.4) | 183 (2.9) | |

| Motor vehicle vs pedestrian | 38 (2.2) | 28 (0.4) | |

| Penetrating injury (gunshot wound or stabbing) | 10 (0.6) | 50 (0.8) | |

| Other | 65 (3.8) | 377 (5.9) | |

| Initial Hospitalb | |||

| Trauma hospital level | |||

| I | 501 (29.1) | 408 (6.3) | <.001 |

| II | 214 (12.4) | 401 (6.2) | |

| III | 608 (35.4) | 904 (14.0) | |

| IV/V | 263 (15.3) | 970 (15.1) | |

| Nontrauma hospital | 134 (7.8) | 3758 (58.3) | |

| Final Hospitalb | |||

| Trauma hospital level | |||

| I | 681 (39.6) | 411 (6.4) | <.001 |

| II | 235 (13.7) | 414 (6.4) | |

| III | 578 (33.6) | 952 (14.8) | |

| IV/V | 185 (10.8) | 938 (14.6) | |

| Nontrauma hospital | 34 (2.0) | 3705 (57.5) | |

| Unknown | 7 (0.4) | 20 (0.3) | |

| Index ED/Hospital Visit | |||

| Diagnosis categoriesc | |||

| Injury | 1720 (100) | 6441 (100) | NA |

| Cardiovascular | 1316 (76.5) | 4777 (74.2) | .05 |

| Endocrine/metabolic | 1001 (58.2) | 3320 (51.5) | <.001 |

| Psychiatric/behavioral | 624 (36.3) | 2000 (31.1) | <.001 |

| Neurologic (nondementia) | 602 (35.0) | 1997 (31.0) | <.001 |

| Respiratory | 587 (34.1) | 1669 (25.9) | <.001 |

| Gastrointestinal | 544 (31.6) | 1506 (23.4) | <.001 |

| Blood disorders/anemia | 520 (30.2) | 1483 (23.0) | <.001 |

| Renal/genitourinary | 500 (29.1) | 1608 (25.0) | <.001 |

| Infection | 378 (22.0) | 1308 (20.3) | .13 |

| Surgical/procedural complication | 191 (11.1) | 628 (9.8) | .10 |

| Cancer | 183 (10.6) | 457 (7.1) | <.001 |

| Dementia | 165 (9.6) | 724 (11.2) | .05 |

| Other | 1189 (69.1) | 5101 (79.2) | <.001 |

| Injury severity | |||

| ISS | |||

| Mean (SE)a | 10.4 (0.18) | 6.5 (0.05) | <.001 |

| 0-8 | 676 (39.3) | 3664 (56.9) | <.001 |

| 9-15 | 669 (38.9) | 2599 (40.4) | |

| ≥16 | 375 (21.8) | 178 (2.8) | |

| AIS score ≥3 | |||

| Head | 331 (19.2) | 179 (2.8) | <.001 |

| Chest | 185 (10.8) | 46 (0.7) | <.001 |

| Abdominal-pelvic | 31 (1.8) | 7 (0.1) | <.001 |

| Extremity | 449 (26.1) | 1792 (27.8) | .16 |

| Hospital interventions | |||

| Major nonorthopedic surgery | 118 (6.9) | 68 (1.1) | <.001 |

| Orthopedic surgery | 516 (30.0) | 1809 (28.1) | .12 |

| Blood transfusion | 285 (16.6) | 688 (10.7) | <.001 |

| Interhospital transfer | 313 (18.2) | 529 (8.2) | <.001 |

| Length of stay, mean (SE), da | 5.0 (0.13) | 2.6 (0.04) | <.001 |

| Outcomes | |||

| Discharge disposition | |||

| Death | 95 (5.5) | 93 (1.5) | <.001 |

| Rehabilitation or skilled nursing facility | 879 (51.1) | 2369 (36.8) | |

| Hospice | 27 (1.6) | 125 (1.9) | |

| Intermediate care facility | 18 (1.0) | 237 (3.7) | |

| Home | 701 (40.8) | 3617 (56.2) | |

| Mortality, d | |||

| 30 | 152 (8.8) | 392 (6.1) | <.001 |

| 90 | 229 (13.3) | 725 (11.3) | .02 |

| 365 | 356 (20.7) | 1531 (23.8) | <.001 |

Abbreviations: AIS, Abbreviated Injury Scale; ED, emergency department; GCS, Glasgow Coma Scale score; ISS, Injury Severity Score; NA, not applicable; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Because multiple imputation was used to handle missing values, SEs are provided for continuous variables.

All patients with a trauma registry record received at least a portion of their care in a trauma center.

Patients could have multiple diagnoses, so percentages do not add to 100%.

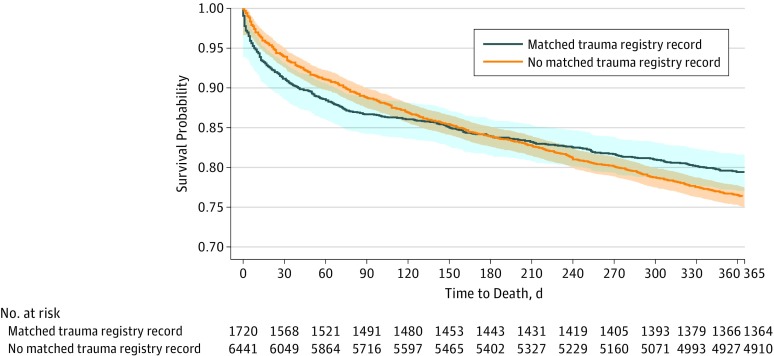

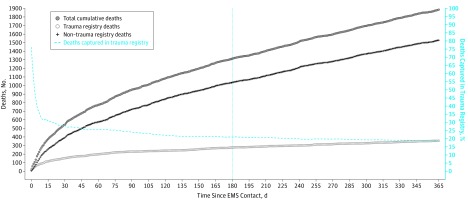

Of the 1887 deaths occurring within 1 year, 188 (10.0%) occurred during the index hospital stay, of which 93 (49.5%) were not captured by trauma registries. Early mortality was higher in the registry group, a finding which persisted through 180 days and changed thereafter (Figure 1). In Figure 2, we illustrate the cumulative number of deaths up to 1 year, both overall and by registry and nonregistry groups. When compared over time, the trauma registry cohort included 38 of 59 deaths (64%) occurring within 1 day, 81 of 225 deaths (36.0%) within 7 days, and 356 of 1887 deaths (18.9%) occurring within 1 year.

Figure 1. Kaplan-Meier Survival Curves for Injured Older Adults With a Matched Trauma Registry Record vs Those With No Matched Trauma Registry Record.

Of the 8161 included patients, 1720 were captured in a trauma registry and 6441 were not. The shaded regions represent 95% CIs. The log-rank test comparing Kaplan-Meier curves yielded a P value of .03. The curves are not adjusted for other covariates.

Figure 2. Deaths Following Injury Among Older Adults.

Injured older adults captured and not captured in a trauma registry were tracked for 1 year, with a total of 1887 deaths recorded. The percentage of deaths captured in the trauma registry cohort was calculated by day, using the cumulative number of deaths occurring in the trauma registry cohort divided by the cumulative total number of deaths at each time point. EMS indicates emergency medical services.

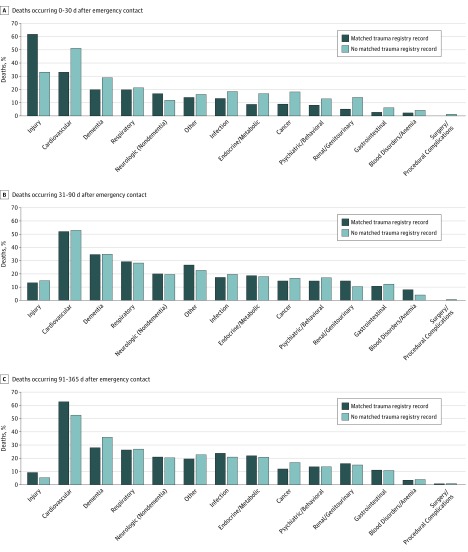

Figure 3 illustrates the causes of death among patients with a matched trauma registry record vs those with no matched trauma registry record. Among 517 deaths in the first 30 days where death certificates were available, trauma registry patients more often had injury as the cause of death (61.8% [84 of 136] vs 33.1% [126 of 381]), while patients without a registry record more often had cardiovascular causes of death (33.1% [45 of 136] vs 51.2% [195 of 381]). For the 398 deaths from 31 to 90 days, injury causes of death were uncommon in both groups (13% [10 of 75] vs 14.9% [48 of 323]), and cardiovascular causes of death were most common (52% [39 of 75] vs 52.9% [171 of 323]). For the 885 deaths occurring from 91 to 365 days, injury causes of death remained uncommon (9.3% [11 of 118] vs 5.2% [40 of 767]), with similar proportions of most other causes of death, except for cardiovascular causes (62.7% [74 of 118] vs 52.5% [403 of 767]) and dementia (28.0% [33 of 118] vs 35.7% [274 of 767]).

Figure 3. Causes of Death Among Injured Older Adults Included vs Not Included in a Trauma Registry.

Of the 1887 deaths occurring in the cohort over 12 months, death certificate data were available for 1800 (95.4%); only observed values are presented. Because a patient could have multiple contributing causes of death, the percentages do not add to 100%. A total of 517 deaths occurred 0 to 30 days after EMS contact (A), 398 deaths occurred 31 to 90 days after EMS contact (B), and 885 deaths occurred 91 to 365 days after EMS contact (C).

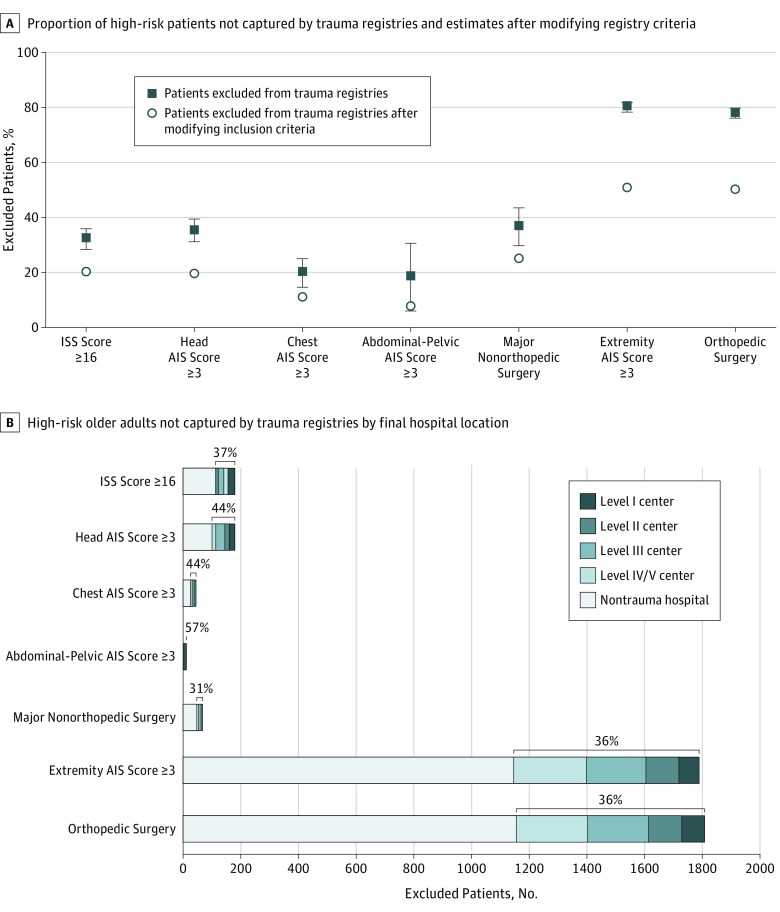

In Figure 4A, we demonstrate the proportion of high-risk injured older adults not captured by trauma registries, which ranged from 18% (7 of 38 patients with abdominal-pelvic AIS score of 3 or greater) to 80.0% (1792 of 2241 patients with extremity AIS score of 3 or greater). In addition, 68 of 186 patients requiring major nonorthopedic surgery (36.6%) and 1809 of 2325 patients requiring orthopedic surgery (77.8%) were not included in registries. We estimate that changing trauma registry inclusion criteria at trauma centers would reduce the proportion of missed high-risk patients to a range of 7.9% (patients with abdominal-pelvic AIS score of 3 or greater) to 51.2% (patients with extremity AIS score of 3 or greater). Among high-risk patients missed by trauma registries (range by injury and procedure type, 36.0% to 57.1%), 36.4% (39.3% when excluding serious extremity injuries and orthopedic procedures) were treated at trauma hospitals, most commonly level III through V trauma centers (Figure 4B) (eTable 3 in the Supplement).

Figure 4. High-Risk Patients Not Captured by Trauma Registries Among 8161 Injured Older Adults.

A, Proportion of high-risk patients not captured by trauma registries and estimates after modifying registry inclusion criteria. The error bars indicate 95% CIs. B, High-risk older adults not captured by trauma registries by final hospital location. The brackets and percentages represent the proportion of patients not captured by trauma registries who were cared for in trauma centers. There were 27 patients with unknown type of final destination hospital.

Discussion

Among injured older adults transported by EMS to 51 hospitals, most deaths after injury and many high-risk patients were not included in trauma registries. This finding is explained by several factors, including a high undertriage rate of seriously injured older adults to nontrauma hospitals, restrictive registry inclusion criteria, and seriously injured older adults at trauma centers missed by registries. By tracking registry and nonregistry older adults up to 1 year, we illustrate that most deaths following injury are not captured by registries. However, many deaths are due to noninjury causes and occur after hospital discharge. These results show that trauma registries, in their current form, are ineffective for studying and evaluating the care of injured older adults. Consequently, these patients remain a blind spot in trauma systems. There is an opportunity to rethink the form and function of trauma registries and to integrate recommendations from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine report about improving trauma data systems through broad capture of information from trauma and nontrauma centers and linkage of data across the continuum of care.8

The characteristics of older adults included in trauma registries were inherently different from those not included. Registry patients tended to be younger, have fewer comorbidities, less frailty, and more serious injuries. Registry patients also had a sharper initial decline in survival but higher survival than nonregistry patients at 1 year. Causes of death between the 2 groups illustrate the important role of noninjury disease states in older adults following injury. Many of these deaths were missed by trauma registries, even when occurring at trauma centers. The inclusion criterion of death resulting from the traumatic injury for trauma registries1 ignores the important role of injury in the decline of health and function among older adults,5,30 even when injury is not directly causal.

Care outside of trauma centers and low rates of subsequent interhospital transfer did not completely explain patients missed by trauma registries. More than 40% of injured older adults in the nonregistry group were initially transported to trauma centers, particularly level III, IV, and V hospitals. Even after restricting to high-risk subgroups, almost 40% of these patients were cared for in trauma centers. That is, these patients were available for inclusion in trauma registries but were not. Our findings may represent overly restrictive registry inclusion criteria and/or high-risk older adults at trauma centers who are simply missed by registries, suggesting opportunities for improvement.

There are a number of potential solutions to improve the capture of high-risk injured older adults in trauma data systems. First, seriously injured older adults have the highest undertriage rate of any age group10,31; addressing this issue would improve access to specialized trauma care32 and inclusion of older adults in registries. Second, registry inclusion criteria could be broadened to capture all patients with an injury diagnosis admitted to a trauma center (including observation status), regardless of injury type or whether the trauma service was involved with their care. While trauma patients seen and discharged from the ED represent an important use of resources,33 these are generally low-risk patients. Next, trauma registries should seek to capture all deaths following injury, whether or not a death appears directly related to trauma. There is also a need for increased attention to registry operations in trauma hospitals, where many high-risk older adults receive care yet are missed by trauma registries. Finally, integrating existing data systems that include nontrauma hospitals (eg, statewide inpatient databases) would capture approximately 60% of high-risk older adults currently missed by registries.

Our findings highlight opportunities to rethink the design of trauma registries, including how data are collected and processed. Electronic health records (EHRs) are exceedingly common and offer gains in efficiency, automation, and patient capture for registries. Conversely, collecting data by medical record review is labor intensive, expensive, and relatively inefficient. Existing EHR platforms capture discreet fields for many variables included in trauma registries, and natural language processing methods are becoming increasingly sophisticated for EHR free text. In addition, most states maintain statewide inpatient databases that include administrative data for admitted patients from all hospitals, representing an opportunity to use data already being collected. Variables such as AIS score, ISS, surgical interventions, and blood transfusion can be mapped from diagnosis and procedure codes, a process that has been validated against manually abstracted values.15,23 There have been concerns that electronic processing methods may not generate data of the same quality as manually abstracted records. However, the methodology for capturing injured patients,12 linking trauma records,13,14,15 generating key variables,15 and handling missing values13,15,16 through electronic data have been evaluated and validated across multiple hospitals and trauma systems. The accuracy, availability, and timeliness of methods for electronic data capture and processing are likely to continue improving, including data exchanges that merge data from different EHR platforms using unique identifiers. Finally, because most deaths occurred after discharge, tracking patients after discharge (eg, by matching to the National Death Index or state vital statistics records) would provide more comprehensive and longer-term outcomes. These suggestions are consistent with those in the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine report8 and represent big opportunities to expand and modernize trauma registries.

Limitations

There were limitations in our study. We limited the sample to patients with matched clinical records, which could have introduced selection bias. However, excluded patients appeared similar to the nonregistry cohort (eTable 1 in the Supplement). Also, Oregon and Washington have inclusive trauma systems where most hospitals submit registry data. Our findings likely underestimate the proportion of deaths and high-risk patients missed by trauma registries in other regions. While we relied on record linkage to identify patients included vs excluded from trauma registries, we independently validated our linkage results.15

Additionally, these data were from 2011 through 2012. While there have been major strides in the standardization of trauma registries and definitions of variables, we are not aware of major changes to the registry inclusion criteria in these states, capture of patients from nontrauma hospitals, or transition into fully electronic data methods in the interim time period.

Conclusions

In summary, we demonstrated that trauma registries in their current form are ineffective in capturing, tracking, and evaluating injured older adults, although mortality following injury is frequently due to noninjury causes. These findings highlight a major blind spot in trauma systems. Data-driven efforts to assess the quality of care and improve outcomes among injured older adults served in trauma systems will require a different approach.

eFigure. Cohort development schematic.

eTable 1. Comparison of patients included vs excluded from the primary analytic cohort.

eTable 2. Specific injury diagnoses among 2241 older adults with extremity Abbreviated Injury Scale (AIS) scores ≥3 by trauma registry status and whether the injury was isolated.

eTable 3. Absolute numbers of high-risk patients not captured by trauma registries by final hospital destination.

References

- 1.The Committee on Trauma; American College of Surgeons National Trauma Data Standard Data Dictionary: 2018 admissions. https://www.facs.org/~/media/files/quality%20programs/trauma/ntdb/ntds/data%20dictionaries/ntds%20data%20dictionary%202018.ashx. Accessed September 26, 2018.

- 2.Shafi S, Nathens AB, Cryer HG, et al. The Trauma Quality Improvement Program of the American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma. J Am Coll Surg. 2009;209(4):-. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2009.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Newgard CD, Fu R, Lerner EB, et al. Deaths and high-risk trauma patients missed by standard trauma data sources. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2017;83(3):427-437. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000001616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marquez de la Plata CD, Hart T, Hammond FM, et al. Impact of age on long-term recovery from traumatic brain injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;89(5):896-903. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2007.12.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Platts-Mills TF, Flannigan SA, Bortsov AV, et al. Persistent pain among older adults discharged home from the emergency department after motor vehicle crash: a prospective cohort study. Ann Emerg Med. 2016;67(2):166-176.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2015.05.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Platts-Mills TF, Nicholson RJ, Richmond NL, et al. Restricted activity and persistent pain following motor vehicle collision among older adults: a multicenter prospective cohort study. BMC Geriatr. 2016;16:86. doi: 10.1186/s12877-016-0260-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heron M. Deaths: leading causes for 2014. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr65/nvsr65_05.pdf. Accessed April 12, 2019.

- 8.Committee on Military Trauma Care’s Learning Health System and Its Translation to the Civilian Sector; Board on Health Sciences Policy; Board on the Health of Select Populations; Health and Medicine Division; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine ; Berwick D, Downey A, Cornett E, eds. A National Trauma Care System: Integrating Military and Civilian Trauma Systems to Achieve Zero Preventable Deaths after Injury. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP; STROBE Initiative . The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61(4):344-349. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Newgard CD, Fu R, Zive D, et al. Prospective validation of the national field triage guidelines for identifying seriously injured persons. J Am Coll Surg. 2016;222(2):146-158.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2015.10.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dean JM, Vernon DD, Cook L, Nechodom P, Reading J, Suruda A. Probabilistic linkage of computerized ambulance and inpatient hospital discharge records: a potential tool for evaluation of emergency medical services. Ann Emerg Med. 2001;37(6):616-626. doi: 10.1067/mem.2001.115214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Newgard CD, Zive D, Jui J, Weathers C, Daya M. Electronic versus manual data processing: evaluating the use of electronic health records in out-of-hospital clinical research. Acad Emerg Med. 2012;19(2):217-227. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2011.01275.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Newgard C, Malveau S, Staudenmayer K, et al. ; WESTRN investigators . Evaluating the use of existing data sources, probabilistic linkage, and multiple imputation to build population-based injury databases across phases of trauma care. Acad Emerg Med. 2012;19(4):469-480. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2012.01324.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Newgard CD. Validation of probabilistic linkage to match de-identified ambulance records to a state trauma registry. Acad Emerg Med. 2006;13(1):69-75. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2005.07.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Newgard CD, Malveau S, Zive D, Lupton J, Lin A. Building a longitudinal cohort from 9-1-1 to 1-year using existing data sources, probabilistic linkage, and multiple imputation: a validation study [published online July 3, 2018]. Acad Emerg Med. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Newgard CD. The validity of using multiple imputation for missing out-of-hospital data in a state trauma registry. Acad Emerg Med. 2006;13(3):314-324. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2005.09.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oregon Health Authority Oregon trauma patient inclusion definition. https://www.oregon.gov/oha/PH/PROVIDERPARTNERRESOURCES/EMSTRAUMASYSTEMS/TRAUMASYSTEMS/Documents/NEW%20OTR%202017%20Inclusion%20Criteria.pdf. Accessed March, 13, 2019.

- 18.Washington State Department of Health Washington State Trauma Registry inclusion criteria. https://www.doh.wa.gov/Portals/1/Documents/Pubs/530113.pdf. Accessed March 13, 2019.

- 19.Dawson DE. National Emergency Medical Services Information System (NEMSIS). Prehosp Emerg Care. 2006;10(3):314-316. doi: 10.1080/10903120600724200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gennarelli TA, Wodzin E; Association for the Advancement of Automotive Medicine . Abbreviated Injury Scale 2005: update 2008. Barrington, IL: Association for the Advancement of Automotive Medicine; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baker SP, O’Neill B, Haddon W Jr, Long WB. The Injury Severity Score: a method for describing patients with multiple injuries and evaluating emergency care. J Trauma. 1974;14(3):187-196. doi: 10.1097/00005373-197403000-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project Clinical Classifications Software (CCS) for ICD-9-CM. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccs/ccs.jsp. Accessed January 8, 2018.

- 23.Fleischman RJ, Mann NC, Dai M, et al. Validating the use of ICD-9 code mapping to generate Injury Severity Scores. J Trauma Nurs. 2017;24(1):4-14. doi: 10.1097/JTN.0000000000000255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373-383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Farhat JS, Velanovich V, Falvo AJ, et al. Are the frail destined to fail? Frailty Index as predictor of surgical morbidity and mortality in the elderly. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;72(6):1526-1530, 1530-1531. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3182542fab [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Patel NY, Riherd JM. Focused assessment with sonography for trauma: methods, accuracy, and indications. Surg Clin North Am. 2011;91(1):195-207. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2010.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rubin DB. Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 1987. doi: 10.1002/9780470316696 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Newgard CD, Haukoos JS. Advanced statistics: missing data in clinical research—part 2: multiple imputation. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14(7):669-678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Raghunathan TE, Lepkowski JM, Van Hoewyk J, Solenberger P. A multivariate technique for multiply imputing missing values using a sequence of regression models. Surv Methodol. 2001;27(1):85-95. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Platts-Mills TF, Nebolisa BC, Flannigan SA, et al. Post-traumatic stress disorder among older adults experiencing motor vehicle collision: a multicenter prospective cohort study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2017;25(9):953-963. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2017.03.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chang DC, Bass RR, Cornwell EE, Mackenzie EJ. Undertriage of elderly trauma patients to state-designated trauma centers. Arch Surg. 2008;143(8):776-781. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.143.8.776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Calland JF, Ingraham AM, Martin N, et al. ; Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma . Evaluation and management of geriatric trauma: an Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma practice management guideline. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;73(5, suppl 4):S345-S350. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318270191f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reilly PM, Schwab CW, Kauder DR, et al. The invisible trauma patient: emergency department discharges. J Trauma. 2005;58(4):675-683, 683-685. doi: 10.1097/01.TA.0000159244.24884.9B [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure. Cohort development schematic.

eTable 1. Comparison of patients included vs excluded from the primary analytic cohort.

eTable 2. Specific injury diagnoses among 2241 older adults with extremity Abbreviated Injury Scale (AIS) scores ≥3 by trauma registry status and whether the injury was isolated.

eTable 3. Absolute numbers of high-risk patients not captured by trauma registries by final hospital destination.