Abstract

Background

This scoping review aims to gather and map inspiration, ideas and recommendations for teaching evidence-based practice across Professional Bachelor Degree healthcare programmes by mapping literature describing evidence-based practice teaching methods for undergraduate healthcare students including the steps suggested by the Sicily Statement.

Methods

A computer-assisted literature search using PubMed, Cinahl, PsycINFO, and OpenGrey covering health, education and grey literature was performed. Literature published before 2010 was excluded. Students should be attending either a Professional Bachelor’s degree or a Bachelor’s degree programme. Full-text articles were screened by pairs of reviewers and data extracted regarding: study characteristics and key methods of teaching evidence-based practice. Study characteristics were described narratively. Thematic analysis identified key methods for teaching evidence-based practice, while full-text revisions identified the use of the Sicily Statement’s five steps and context.

Results

The database search identified 2220 records. One hundred ninety-two records were eligible for full-text assessment and 81 studies were included. Studies were conducted from 2010 to 2018. Approximately half of the studies were undertaken in the USA. Study designs were primarily qualitative and participants mainly nursing students. Seven key methods for teaching evidence-based practice were identified. Research courses and workshops, Collaboration with clinical practice and IT technology were the key methods most frequently identified. Journal clubs and Embedded librarians were referred to the least. The majority of the methods included 2–4 of the Sicily Statement’s five steps, while few methods referred to all five steps.

Conclusions

This scoping review has provided an extensive overview of literature describing methods for teaching EBP regarding undergraduate healthcare students. The two key methods Research courses and workshops and Collaboration with clinical practice are advantageous methods for teaching undergraduate healthcare students evidence-based practice; incorporating many of the Sicily Statement’s five steps. Unlike the Research courses and workshop methods, the last step of evaluation is carried out partly or entirely in a clinical context. Journal clubs and Embedded librarians should be further investigated as methods to reinforce existing methods of teaching. Future research should focus on methods for teaching EBP that incorporate as many of the five steps of teaching and conducting EBP as possible.

Keywords: Teaching methods, Undergraduate healthcare students, Evidence-based practice, The Sicily statement

Background

Dizon et al. state that healthcare can be inefficient, ineffective and/or dangerous when it is not based on current best evidence [1, 2]. Therefore, to ensure the quality of healthcare, it is important to implement evidence-based practice (EBP) in all health professional curricula, so that future health professionals learn the fundamentals of research and the application of evidence in practice [2].

Several definitions of EBP have been suggested in recent years. The scientific evidence was initially developed within medicine, but as many health professionals have embraced an evidence-based way of practice the Sicily Statement [3] suggested that the original term “evidence-based medicine” should be expanded to “evidence-based practice” in order to reflect a common approach to EBP across all health professions.

The Sicily Statement gives a clear definition of EBP together with a description of the minimum level of educational requirements and skills required to practice in an evidence-based manner. This makes the underlying processes of EBP more transparent and distinguishes between the process and outcome of EBP [3].

In order to fulfil the minimum requirements of teaching and conducting EBP, the Sicily Statement puts forward a five-step model: (I) asking a clinical question; (II) collecting the most relevant evidence; (III) critically appraising the evidence; (IV) integrating the evidence with one’s clinical expertise, patient preferences and values to make a practice decision; and (V) evaluating the change or outcome [4].

Internationally, EBP skills are essential requirements in clinical practice among both medical doctors as well as among other health professionals. Healthcare students are mainly taught the first three steps of the Sicily Statement’s five-step model. The last two steps are rarely taught, and students and graduates thus lack competencies in applying their knowledge in the clinical setting during or after graduation [5, 6].

In terms of healthcare policy and ambitions in Denmark, it was decided in 2015 that Professional Bachelor Degree healthcare students were to contribute to the development of an evidence-based way of working, a faster implementation of new knowledge in practice, and to the development of greater patient involvement and patient safety in the Danish healthcare system [7]. The Professional Bachelor’s degree is awarded after 180–270 ECTS and includes a period of work placement of at least 30 ECTS. The programmes are applied programmes. They are development-based and combine theoretical studies with a practical approach. Examples of professional bachelor degree holders are nurses. The Danish title is Professionsbachelor and the English title is Bachelor [8]. In Denmark the University College institutions solely provide professional bachelor degree educations. Master degrees are awarded at the Universities.

Based on the Sicily Statement students should be able to reflect, ask questions, gather knowledge, critically appraise, apply and evaluate various kinds of knowledge at the end of their course. The aim is that all Professional Bachelor Degree healthcare students across disciplines of nursing, physiotherapy, occupational therapy, radiography, and biomedical laboratory science develop common EBP qualifications in order to contribute towards the development of evidence-based healthcare [9]. In order to ensure shared prerequisites and mutual understanding of the EBP concepts before entering theoretical or clinical inter-professional education, further knowledge about how to teach EBP across disciplines is required [9]. By teaching the fundamental principles of EBP, students will develop their EBP skills and ability to put them into practice in their studies and as future graduates.

Previously, some systematic reviews were conducted summarising various educational interventions or strategies for teaching EBP to undergraduate healthcare students [2, 10–12].

In a review from 2014, Young and colleagues stated that multifaceted interventions integrated into clinical practice contributed to the greatest improvements in EBP knowledge, skills, and attitudes [2]. In line with this, Kyriakoulis et al. suggested that a combination of interventions, such as lectures, tutorials, workshops, conferences, journal clubs, and online sessions was best suited for teaching EBP to undergraduate healthcare students [10]. However, the majority of the articles in both reviews synthesized information from interventions or strategies aimed at medical students at various educational levels. Only a few articles elicited information about educational interventions and strategies aimed at undergraduate healthcare students in the disciplines of nursing, physiotherapy, occupational therapy, radiography, and/or biomedical laboratory science. However, two recent reviews have specifically addressed EBP teaching for undergraduate nursing students [11, 12]. A systematic review investigated the effectiveness of specific educational methods and found an effect on student knowledge, attitudes, and skills but could not draw a conclusion as to the advisability of one of the methods [11]. A literature review sought to identify knowledge experiences on teaching strategies from qualitative studies in nursing EBP education to enhance knowledge and skills and points to a limited focus on the use of EBP teaching strategies. Additionally, the study points to the need for more qualitative research investigating interactive and clinically integrated teaching strategies. Despite both reviews being well-informing, a broad scope when mapping updated EBP teaching methods and strategies across healthcare bachelor educations will further qualify future interdisciplinary practices [11, 12].

In order to implement the most effective ways of teaching EBP across healthcare undergraduate students, an investigation of existing literature on the subject needs to be undertaken. For identifying, mapping and discussing key characteristics in the literature a scoping review is the better choice [13].

Aim, objectives and review question

The aim of this scoping review is to gather and map inspiration, ideas, and recommendations for teachers implementing EBP across Professional Bachelor Degree healthcare programmes by mapping existing literature describing EBP teaching methods, including the five steps of EBP suggested by the Sicily Statement, [3] regarding undergraduate healthcare students.

The primary question of the scoping review is: “Which EBP teaching methods, including The Sicily Statement’s steps of teaching and conducting EBP, have been reported in the literature with respect to undergraduate healthcare students in classrooms and clinical practice?”

Definitions

Classroom is defined as a room where classes are taught in a school, college or university [14].

Clinical practice refers to the agreed-upon and customary means of delivering healthcare by doctors, nurses and other health professionals [15].

Methods

To ensure a systematic methodology, The Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers’ Manual - Methodology for JBI Scoping Reviews has been used throughout the scoping review process [16, 17].

Inclusion criteria

Participants

Literature which included undergraduate healthcare students in the disciplines of nursing, physiotherapy, occupational therapy, radiography, and biomedical laboratory science was selected to ensure applicability and relevance to similar scientific disciplines at other institutions of higher education. The undergraduate students should be attending either a Professional Bachelor’s degree or a Bachelor’s degree programme.

Concept

Methods for teaching EBP including The Sicily Statement’s steps of teaching and conducting EBP was the main concept to be investigated in the review. That is; literature describing either recommendations of EBP teaching methods, evaluations of EBP teaching methods, teacher and/or student perceptions of EBP teaching and learning methods, or qualifications obtained when learning the principles of EBP.

Context

Literature describing methods for teaching EBP conducted in a classroom setting, in clinical practice as part of the education, or in a combination of classroom and clinical practice was included in the review.

Exclusion criteria

In the period up to 2010, the Bachelor Degree healthcare educations began to conform to European requirements regarding evidence-informed and evidence-based education [18].

A maximum time frame (2010–2018) was applied, determined by the amount of available literature/research studies and requirements of updated teaching strategies [19, 20]. Therefore, literature published before 2010 was excluded.

Literature including undergraduate students in other health disciplines such as medicine or dentistry was not reviewed as the structure of their education is based on another paradigm. Nor was literature including participants such as graduates, RN-to-BSN students, and trained health personnel accepted for inclusion as they were considered as postgraduates, not comparable to undergraduate students. With the primary aim of gathering ideas and inspiration for teaching EBP, literature that focused on issues other than methods for teaching EBP was excluded, as well as literature in languages other than English, Danish, Norwegian, or Swedish.

Search strategy

To identify literature relevant to our research question, the databases MEDLINE via PubMed, CINAHL Complete, and PsycINFO (both via EBSCO) were systematically searched. These databases cover both health and education and are available to the primary local target audience of this scoping review. Because of time limitations only the multidisciplinary European database, OpenGrey, was searched in the attempt to find unpublished literature. The searches were conducted May 9th, 2018.

As recommended in The Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers’ Manual [16, 17], the search was conducted in three steps in collaboration with a research librarian.

Step 1: The databases PubMed, covering the field of biomedicine and CINAHL, covering nursing and allied health literature were searched using the keywords: ‘teaching methods’, ‘teaching’, ‘learning methods’, ‘learning’, ‘teaching strategies’, ‘learning strategies’, ‘undergraduate’, ‘undergraduate education’, ‘student’, ‘biomedical laboratory scientist’, ‘medical laboratory scientist’, ‘medical laboratory technologist’, ‘medical laboratory technologists’, ‘radiographer’, ‘occupational therapist’, ‘physiotherapist’, ‘nurse’, and ‘evidence-based practice’.

Step 2: Through an analysis of text words in titles and abstracts of the studies found in PubMed and Cinahl, new keywords, which would improve the search, were identified. These were ‘allied health’, health students’, and ‘nursing’. All identified keywords were then included in the search as a systematic block search in PubMed, Cinahl, and PsycINFO, covering literature in the behavioural and social sciences, and OpenGrey, covering grey literature in Europe. Table 1 provides a list of the specific search queries used in all databases.

Step 3: The reference lists of identified studies were searched for additional studies.

Table 1.

Specific search queries, all databases

| Database | Search queries |

|---|---|

| PubMed | (((((teaching OR learning))) AND (undergraduate OR student OR allied health OR health students)) AND ((biomedical laboratory scientist OR medical laboratory scientist OR medical laboratory technologist OR medical laboratory technologists OR radiographer OR occupational therapist OR physiotherapist OR nurse OR nursing))) AND evidence-based practice |

| Cinahl Complete | (teaching OR learning) AND (undergraduate OR student OR allied health) AND (biomedical laboratory scientist OR medical laboratory scientist OR medical laboratory technologist OR medical laboratory technologists OR radiographer OR occupational therapist OR physiotherapist OR nurse OR nursing) AND evidence-based practice |

| PsycInfo via EBSCO | (teaching OR learning) AND (undergraduate OR student OR allied health) AND (biomedical laboratory scientist OR medical laboratory scientist OR medical laboratory technologist OR medical laboratory technologists OR radiographer OR occupational therapist OR physiotherapist OR nurse OR nursing) AND evidence-based practice |

| Open Grey | (“Evidence based practice” OR EBP OR Evidence-based practice OR Evidence based practice) AND (teaching OR education OR learning) AND (undergraduate OR student OR students) |

Study selection

All search results from the databases were imported to the web-based bibliographic management software, RefWorks 2017 by ProQuest. After exclusion of duplicates and records before 01.01.2010, two reviewers independently screened titles and abstracts of the remaining articles for relevance in relation to the research question and the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Afterwards, all full-text articles were further checked for relevance by two independent reviewers. Any inconsistencies between the two reviewers regarding study selection for final inclusion were resolved by discussion with a third reviewer.

Data collection

Data from the included articles were extracted using two data extraction tools as recommended in The Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers’ Manual [16, 17]. The first data extraction tool comprised study characteristics, while the other data extraction tool comprised methods for teaching EBP.

Prior to the process of extracting data from the included articles, a pilot test using the data extraction tools was conducted by one reviewer assessing nine articles. To ensure agreement between reviewers, a second reviewer checked the same articles. Any disagreements about the content or use of the data extraction tools were discussed and resolved.

One reviewer then extracted relevant data from all included articles to the data extraction tools. Two other reviewers split the same articles among them and extracted data using the same data extraction tools. As a final step, the first reviewer went through all extracted data from all of the included articles with each of the other reviewers to ensure comparability and completeness in the final data extraction tools.

Synthesis and analysis of results

The data extraction tools formed the basis of the final presentation of the results in two tables consisting of “Study characteristics” and “Key methods for teaching EBP, the Sicily Statement’s five steps of teaching and conducting EBP and context”. Study characteristics included author, year of publication, title, journal, country of origin, study design, study participants, methods for teaching EBP, and main study findings. The key methods for teaching EBP were identified through a thematic analysis. All full text articles were read and every teaching method found was listed. Through a revision of all teaching methods listed, seven themes were found that described the most prominent teaching methods, which were named “Key methods for teaching EBP”. All methods were then divided into one of the key methods for teaching EBP. In some articles, more than one teaching method was described. In that case, the teaching method most frequently described was selected and categorised under the relevant key method. Through full-text revision the Sicily Statement’s steps of teaching and conducting EBP and the context (classroom, clinical practice or a combination of both) in which the teaching took place was found. To further clarify the content of the two tables all results listed were described narratively. All tabulated data, except for the key methods for teaching EBP identified in Table 3, have been cited directly from the articles.

Table 3.

Key methods for teaching undergraduate healthcare students EBP, the Sicily Statement’s five steps of teaching and conducting EBP and context

| Source (first author, year) | Key methods for teaching undergraduate healthcare students EBP | The Sicily Statement’s five steps in teaching and conducting EBP | Context | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Ask a clinical question | 2. Collect the most relevant evidence | 3. Critically appraise the evidence | 4. Integrate the evidence with one’s clinical expertise, patient preferences, and values to make practice decision | 5. Evaluate change or outcome | |||

| Balakas, 2010 [23] | Research courses and workshops | Students learned how to use their clinical PICO question… | ..as a guide for conducting literature searches | Students were guided in the use of rapid appraisal guidelines for quantitative and qualitative research. Written critical appraisals were completed to further develop students’ critiquing skills | Each student group presented their PICO questions, evidence synthesis, reference list, and recommendations to the community programme managers | Students learned to evaluate a body of evidence | Classroom + clinical practice |

| Bloom, 2013 [26] | Research courses and workshops | Nursing Science I: The process of reviewing the literature is explored, and the final project for the course is a literature search designed to identify the most current evidence available for a given topic | Nursing Science II: The emphasis of the course is on critical appraisal of a primary research report | Nursing Science III: Students use evidence-based models to systematically practice decision-making skills related to a clinical question of interest to them | Classroom | ||

| Boyd, 2015 [27] | Research courses and workshops | Classroom | |||||

| Cable-Williams, 2014 [29] | Research courses and workshops | Classroom + clinical practice | |||||

| Davidson, 2016 [33] | Research courses and workshops | Students learn to develop PICO clinical questions… | …searches for external evidence to answer focused clinical questions… | …participates in the critical appraisal of published research studies… | …to determine their strength and applicability to clinical practice… | …and disseminates best practices supported by evidence to improve quality of care and patient outcomes | Classroom |

| Dewar, 2012 [35] | Research courses and workshops | Four 3-h writing workshops including how to develop a clinical question… | …and identify relevant information from published researchstudies | Classroom | |||

| Friberg, 2013 [42] | Research courses and workshops | Students had a close collaboration with librarians with ten different workshops focusing on different aspects of literature retrieval | Students used knowledge-based analysis of both quantitative and qualitative results… | …and best evidence for a specific nursing action and transformed results and new knowledge into practice | Classroom | ||

| Jakubec, 2013 [47] | Research courses and workshops | Students wrote their appraisal of evidence in an existing policy or guideline… | …met with a health reference librarian to conduct a systematic search of the literature on the topic… | …provided a critical review of existing evidence with the policy or guideline and reviewed any updated or more recent evidence… | …and wrote a summary of their recommended policy changes for practice | Classroom | |

| Jalali-Nia, 2011 [48] | Research courses and workshops | The evidence-based approach, learning activities for each group included developing a clinical question using the PICO… | …searching for evidence… | …reading and critiquing nursing research… | … and discussing articles, synthesising the evidence, and developing a summary of findings | Classroom | |

| Janke, 2012 [49] | Research courses and workshops | Students had to clarify the research question… | …designing a literature search strategy and complete the search… | …select the articles and record important data from the articles… | …and submit the paper/results to the clinical partners | Classroom | |

| Jelsness-Jørgensen, 2015 [50] | Research courses and workshops | Week 1: Lectures in databases and literature search | Week 1: Introduction to Critical Appraisal Skill Tools. Week 2: Group work and seminars focusing on critical appraisal of qualitative papers. Week 3: Group work and seminars focusing on critical appraisal of quantitative papers | Classroom | |||

| Jones, 2011 [52] | Research courses and workshops | The assessment tasks were designed to enable students to conduct and report a critique of a published paper | The third and fourth assessment tasks were designed to enable students to apply the skills they had learnt in the subject | Classroom | |||

| Kiekkas, 2015 [54] | Research courses and workshops | Classroom | |||||

| Kyriakoulis, 2016 [10] | Research courses and workshops | Interventions covered different steps of the EBP domains: Research question… | …sources of evidence…2 studies focused on the searching databases skill | …evidence appraisal… | …and implementation into practice… | Classroom | |

| Leach, 2016 [55] | Research courses and workshops | Identification and development of research question from practice | Construction and execution of search strategies to retrieve relevant primary research articles | Critical appraisal of the literature | Summary, presentation and dissemination of evidence in different formats | Classroom + clinical practice | |

| Lewis, 2016 [56] | Research courses and workshops | The EBP1 course aimed to develop foundation knowledge and skills in EBP, with emphasis on three of the five EBP steps outlined in the Sicily Statement incl. Frame a research question… | …to access and search library databases and other resources and to reflect on the processes associated with this approach. | The EBP2 course had additional training inAppraising methodological bias… | …as well as teaching students how to apply each of the five EBP steps | Classroom | |

| Liou, 2013 [57] | Research courses and workshops | Mini research project with introduction how to formulate a research problem… | …conduct literature searches… | …read and select articles… | …and an oral and poster presentation of findings | Classroom | |

| Morris, 2016 [65] | Research courses and workshops | Classroom | |||||

| Phillips, 2014 [75] | Research courses and workshops | Classroom | |||||

| Pierce, 2016 [76] | Research courses and workshops | During the e-poster conference students develop a research question… | …appraise data collection… | …critique published literature… | …and write about how to begin a change to organisational visitation policy based on the research evidence from the poster conference | Classroom | |

| Rodriguez, 2012 [83] | Research courses and workshops | Students conducted a research project which included a literature review… | …presented their results and designed a scientific poster with their results | Classroom | |||

| Whalen, 2015 [97] | Research courses and workshops | The worksheet included mainly step 1–3 of EBP. Asking a clinical question using PICO… | …searching the literature… | …and critically appraising the literature found | Classroom | ||

| Zhang, 2012 [100] | Research courses and workshops | Students independently conducted online and library searches to find information | Students were asked to read an assigned article and critique it to the best of their ability | Students created presentation slides and shared an in-depth critique of one aspect of the specified research article | Classroom + clinical practice | ||

| Milner, 2017 [62] | Research courses and workshops | Students learn to build and frame practice questions by gaming | Classroom | ||||

| Sukkarieh-Haraty, 2017 [96] | Research courses and workshops | Students learned how to use a clinical PICO question | …and collected scholarly literature | Compared their observations to hospital protocol against the latest evidence-based practice guidelines | Students proposed changes in practice with scholarly literature | Classroom + clinical practice | |

| Erichsen, 2018 [40] | Research courses and workshops | Ask a clinical question | Collect relevant literature/articles | Critically appraise the articles | Students present their work in different ways; e.g. implementation-plan, poster | The results were evaluated | Classroom + clinical practice |

| Scurlock-Evans, 2017 [90] | Research courses and workshops | Students were taught what EBP is, how it links with research methodology and process and ethics (in year 2) | Students were taught how to assess quality of literature/evidence (in year 1) | Students undertook an independent research project in their final year (3 year) | Classroom | ||

| Keiffer, 2018 [53] | Research courses and workshops | Students ask a PICOT (population, intervention, control, outcomes, time) question | Develop strategies to search – and search | Appraise research | Design a change and disseminate the evidence by making recommendations for best practice | Classroom | |

| Sin, 2017 [91] | Research courses and workshops | Faculty have framed questions/students develop a question using PICO later in their nursing school | Acquiring evidence by selecting evidence-based resources through literature in collaboration with a librarian | Students state the rationale for their intervention choice incorporating the appraisal learned in the class | Students are asked to identify at least three EBP implementation strategies based on their literature review using at least two references | Classroom | |

| Coyne, 2018 [31] | Research courses and workshops | Students learned how to ask research questions and how to lean on one another for help and guidance | Students helped the faculty member in her research project to collect relevant literature | …including helping with initial review of the literature | Students did a formal podium presentation regarding their summer experiences. The programme led to changes at the health system and led to initiation of research studies | Classroom + clinical practice | |

| Hande, 2017 [44] | Research courses and workshops | Students identify the potential clinical questions as they become aware of current generalist nursing care problems | Students are guided through the sequence of steps to review research | Students critically appraise the scholarly information | Students are guided through the sequence of steps to develop an EBP implementation plan | Students make a presentation of an evidence-based project addressing a selected clinical problem for the purposes of improving clinical outcomes: Population/patient, problem, intervention, comparison, outcome, time question, recommendations for evidence-based practice change | Classroom + clinical practice |

| Malik G, 2017 [59] | Research courses and workshops | Asking clinical questions | Finding relevant evidence (sometimes workshops delivered by the library staff) | Appraising the evidence | Applying evidence into clinical practice (theoretically) | Classroom | |

| Berven, 2010 [24] | Collaboration with clinical practice | Clinical practice | |||||

| Elsborg Foss, 2014 [38] | Collaboration with clinical practice | Students were taught in computer-based literature search | Students read, appraised, and discussed the articles that were chosen | Students presented the findings from the literature search about ‘best practice’ and the recommendations for changes… | …and second-year students observed to what extent the decisions about changes were followed | Classroom | |

| Gray, 2010 [43] | Collaboration with clinical practice | In the introductory nursing research course prior to the research partnership, all nursing students are required to complete an evidence-based research project including the five steps | Classroom + clinical practice | ||||

| Moch, 2010 [64] | Collaboration with clinical practice | Classroom | |||||

| Moch, 2010 [63] | Collaboration with clinical practice | In discussion groups students found four articles related to the topic… | …and students and staff, along with faculty, read and discussed each of the articles in four discussion sessions | Classroom | |||

| Odell & Barta, 2011 [71] | Collaboration with clinical practice | Assignment outcomes related to step 2 and 3: Collaborate in the collection of evidence and participate in the process of appraisal, of evidence | Clinical practice | ||||

| O’Neal, 2016 [70] | Collaboration with clinical practice | Students wrote a related PICOT question… | …conducted a review of the literature | …followed guidelines to critically appraise articles | …identified application to practice | …developed recommendation for the future | Clinical practice |

| Pennington, 2010 [73] | Collaboration with clinical practice | Students wrote up the formalised research proposal | Students performed literature searches and… | …were instruments in collection and analysis of the pre-implementation survey data | The partnerships offered students + staff an opportunity to experience how make best practice decisions using a systematic EBP process | Classroom + clinical practice | |

| Raines, 2016 [78] | Collaboration with clinical practice | Students searched relevant evidence and… | …reviewed the literature found and appraised the quality of the evidence found | Classroom + clinical practice | |||

| Reicherter, 2013 [80] | Collaboration with clinical practice | Students learn to develop an evidence-based question… | …search for and retrieve relevant journal articles… | …analyse the results… | …student teams create and present a case report to classmates and outline potential clinical decisions using the evidence | Classroom + clinical practice | |

| Schams, 2012 [87] | Collaboration with clinical practice | Students were encouraged to write a clinical question using PICOT. | The group was divided into teams who shared the responsibilities for searching and reporting EBP information that supported or refuted current practice. As a team students discussed relationships among laboratory concepts, current practice, and EBP information found in literature. By using post-conference time immediately following clinical practice experiences, students could associate their personal experiences in practice with the EBP information. | Classroom + clinical practice | |||

| Scott, 2011 [89] | Collaboration with clinical practice | Students learned to write PICOT questions… | …and search the literature | Students learned appraisal and met with therapists to validate direction of search… | …and relevance of evidence to practice | Classroom + clinical practice | |

| Smith-Stoner, 2011 [92] | Collaboration with clinical practice | Students performed literature searches… | …and presented editing policy to clinical staff | Clinical practice | |||

| Smith-Strøm, 2012 [93] | Collaboration with clinical practice | The 12 –day course trained the students in the four steps of EBP: Formulating a question… | …searching for evidence… | …critically appraising the evidence… | …and applying the evidence | Clinical practice | |

| Brown, 2015 [28] | IT Technology | The iPad provided point-of-care access to clinical guidelines and resources… | …enabling students to implement an evidence-based approach to decision making and problem solving | Classroom | |||

| Callaghan, 2011 [30] | IT technology | Staff revealed two key research processes as being vital to students’ understanding of research and subsequent critical appraisal, these being searching for… | …and evaluating literature | Classroom | |||

| Doyle, 2016 [36] | IT technology | Mobile software is a positive information tool for information literacy… | …and for informing clinical decisions | Clinical practice | |||

| Eales-Reynolds, 2012 [37] | IT technology | Students indicated that the WRAP improved their critical appraisal skills… | …and questioning of the research evidence basis for practice | Classroom | |||

| Morris, 2010 [66] | IT technology | The guideline appraisal activity helped students formulated a searchable question | The guideline appraisal activity helped students retrieve evidence | The guideline appraisal activity helped students critically appraise the evidence | The guideline appraisal activity helped students apply the evidence to practice | Clinical practice | |

| Nadelson, 2014 [68] | IT technology | Critical group appraisals of EBP websites relevant for clinicians | Classroom | ||||

| Revaitis, 2013 [81] | IT technology | Through FaceTime videoconference students benefit from interacting with research teams and are able to discuss how research findings are applied to practice | Classroom | ||||

| Strickland, 2012 [95] | IT technology | Classroom | |||||

| Blazeck, 2011 [25] | Assignments | The main purpose of the assignment is accessing research-based evidence relevant to an identified clinical problem | Classroom | ||||

| Dawley, 2011 [34] | Assignments | Students were to generate relevant clinical questions that evolved from their clinical experiences… | …and were asked to conduct a literature search to identify two research articles that began to answer their questions | Classroom | |||

| McCurry, 2010 [61] | Assignments | Students completed a database search and met with the course faculty to refine electronic searches… | …critically examined the literature… | …and submitted abstracts and prepared an oral presentation and poster of the chosen articles | Classroom | ||

| Nadelson, 2014 [67] | Assignments | Students receive an article to be reviewed, read and critically appraise using the CASP tool | Classroom | ||||

| Roberts, 2011 [82] | Assignments | Students learned to search the literature using a variety of mechanisms | Classroom | ||||

| Andre, 2016 [22] | Participation in research projects | Increased understanding of the importance of critical thinking | Increased understanding of the importance of implementation of research in daily practice | Increased understanding of the importance of evaluation of clinical practice through the use of EBP | Classroom + clinical practice | ||

| Henoch, 2014 [45] | Participation in research projects | Students collected data | Classroom + clinical practice | ||||

| Niven, 2013 [69] | Participation in research projects | Students collected both qualitative and quantitative data using questionnaires | Classroom + clinical practice | ||||

| Ruskjer, 2010 [85] | Participation in research projects | Faculty guide the team in constructing the question in PICO | Librarian provides guidance in the computer laboratory, as students gain hands-on experience conducting an online literature search | The team critically appraises systematic reviews and practice guidelines, and individual students appraise relevant research articles | Faculty assists the team in looking at the evidence and discusses any recommended changes in practice | Classroom | |

| Schreiner, 2015 [88] | Participation in research projects | Students initiated the project by conducting a literature review for EBP articles related to heart failure education | Articles were chosen by their relevance to the enhancement of staff education for heart failure patients | Clinical practice | |||

| Laaksonen, 2013 [58] | Journal clubs | Students searched for scientific knowledge to answer a clinical question of the journal club… | …evaluated the articles and other relevant material… | …and prepared short written papers based on the knowledge they had collected and evaluated | Classroom | ||

| Mattila, 2013 [60] | Journal clubs | Students prepared for the journal club by acquiring data with the help of an information specialist | After presenting the article, participants discussed how the results could be used in nursing care and what type of solution or new perspective had been gained. Students generated the discussion and gave their opinion of the both oral and written | Classroom | |||

| Phelps, 2015 [74] | Embedded librarians | The ILCSN will help students gather… | …analyse… | …and use information | Classroom | ||

| Putnam, 2011 [77] | Embedded librarians | The embedded librarian assisted students in developing appropriate search techniques | The summative EBP paper developed the review of literature, including integrating, analysing… | …applying, and presenting information | Classroom | ||

| Aglen, 2016 [21] | Theories of teaching – and learning | The pedagogical strategies presented invite the learner to become an active participant in the learning activity, e.g. assessing research, conducting a research project and assessing patients’ requirements for healthcare. This means that they are encouraged to use discretion to solve ill-structured problems related to the steps of EBP, the research process and their own clinical practice. Another strategy to enhance students’ interest and make the learning tasks relevant is to link the learning task to real clinical situations | Classroom | ||||

| Crawford, 2011 [32] | Theories of teaching – and learning | PBL enhances critical thinking… | ..and transfer of theory to practice | Classroom + clinical practice | |||

| Epstein, 2011 [39] | Theories of teaching – and learning | Classroom | |||||

| Florin, 2012 [41] | Theories of teaching – and learning | Highest correlation coefficients between students’ experience of support for research utilisation and EBP skills in formulating questions to search for research-based knowledge (step 1) and critically appraising and compiling best knowledge (step 3) on campus. | Classroom + clinical practice | ||||

| Hickman, 2014 [46] | Theories of teaching – and learning | Classroom | |||||

| Johnson, 2010 [51] | Theories of teaching – and learning | Students develop their own research proposal, which includes defining a research question… | …searching the literature… | …and formulate appropriate methods | Classroom | ||

| Oja, 2011 [72] | Theories of teaching – and learning | All studies except one in the review found significant effects of PBL on critical thinking skills | Clinical practice | ||||

| Raurell-Torredà, 2015 [79] | Theories of teaching – and learning | Classroom + clinical practice | |||||

| Rolloff, 2010 [84] | Theories of teaching – and learning | Students will develop information literacy skills… | …explore systematic review databases for evidence related to laboratory experiences and introduce other information literacy sources | …critique websites, research articles and clinical experiences from an EBP perspective for health information | …incorporate EBP into patient care plans and develop a research proposal based on evidence gaps identified in practice | …and evaluate clinical policies and procedures from an EBP perspective and discuss change process | Classroom |

| Ruzafa-Martinez, 2016 [86] | Theories of teaching – and learning | Students should identify a nursing problem in patients cared for during clinical training and formulate a clinical PICO question... | …identify clinical practice guidelines, systematic reviews and/or original articles… | …critically appraise search results… | …describe recommendations on the clinical question and identify the level of evidence and grade of recommendation… | …and present the results of the final exercise in a poster to the seminar group, giving reasons for implementation of the search results | Classroom |

| Stombaugh, 2013 [94] | Theories of teaching – and learning |

Sophomore-level: Students generated a PICO question…Students copied the process of the librarian describing an example of a PICO question, creation of a search term and conduction of a search in CINAHL Junior level: Students searched databases other than CINAHL Senior level: Students created PICO related to practice experience, individually searched databases and retrieved “best practice” evidence |

Classroom | ||||

| Wonder, 2015 [98] | Theories of teaching – and learning | Students critically appraised analysis methods and findings in the context of quality and safety improvement… | …and identified implications for nursing and the inter-professional team | Classroom | |||

| Yu, 2013 [99] | Theories of teaching – and learning | Classroom | |||||

Results

Literature search

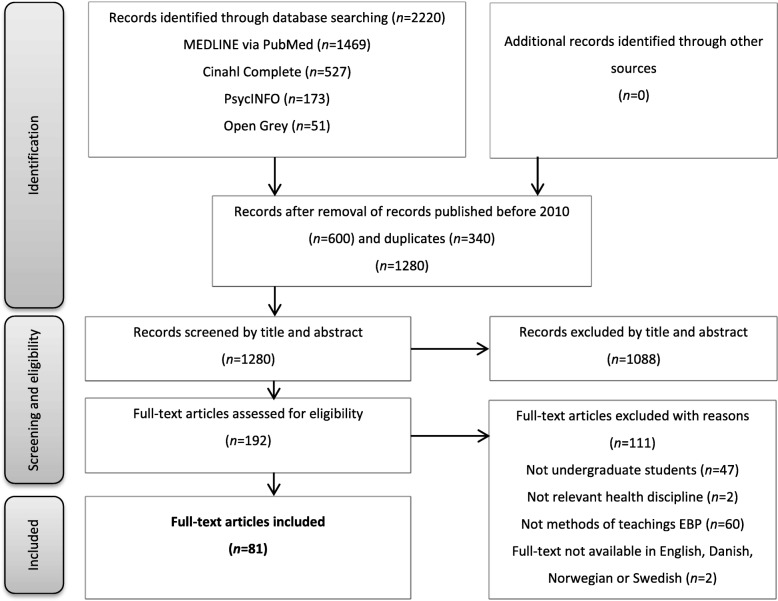

The database search returned 2220 records: PubMed (n = 1469), Cinahl (n = 527), PsycINFO (n = 173), and OpenGrey (n = 51) (Fig. 1). Records published before 01.01.2010 and duplicates were removed, which left 1280 records to be screened by title and abstract. Based on relevance, 1088 records were excluded and 192 records were found eligible for full-text assessment. In accordance with the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 111 articles were excluded. The excluded articles concerned study participants other than undergraduate healthcare students (graduates, RN-to-BSN students, trained health personnel), study participants from other healthcare disciplines (medicine, dentistry, midwifery), issues other than methods for teaching EBP (simulation teaching, community health nursing, EBP beliefs, etc.), and full-text articles not available in English, Danish, Norwegian, and Swedish (French, Chinese). In agreement with the other reviewers, 81 studies were finally included in the scoping review.

Fig. 1.

Modified PRISMA flow diagram illustrating the scoping review selection process

Study characteristics

Study characteristics are presented in Table 2. All studies were spread across the years 2010–2018. Almost half of the studies (n = 40) were conducted in the USA, followed by Canada (n = 8), Norway (n = 7), Australia (n = 6), England (n = 6), Sweden (n = 3), China (n = 2), Finland (n = 2), Spain (n = 2), Greece (n = 1), Iran (n = 1), Lebanon (n = 1), Scotland (n = 1), and Taiwan (n = 1). The study designs were primarily qualitative (n = 55), while 23 of the studies were quantitative, and three of the studies used a mixed method. The majority of the participants were nursing students (n = 72), followed by a combination of nursing students and students from other healthcare disciplines (n = 5), nursing and physiotherapy students (n = 1), physiotherapy students and students from other healthcare disciplines (n = 1), occupational and physiotherapy students (n = 1), and physiotherapy students only (n = 1).

Table 2.

Study characteristics (N = 81)

| First author | Year | Title | Journal | Country | Design | Participants | Methods for teaching EBP | Main study findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aglen [21] | 2016 | Pedagogical strategies to teach bachelor students EBP: A systematic review | Nurse Education Today | Norway | Qualitative | Nursing students | Theories of discretion, knowledge transfer and cognitive maturity development | Nursing students struggle to see the relevance of evidence for nursing practice. Before being introduced to information literacy and research topics, students need insight into knowledge transfer and their own epistemic assumptions. Knowledge transfer related to clinical problems should be the learning situations prioritised when teaching EBP at bachelor level. |

| André [22] | 2016 | Embedding evidence-based practice among nursing undergraduates: Results from a pilot study | Nurse Education in Practice | Norway | Qualitative | Nursing students | Information about voluntary participation in two different clinical research projects, education programme related to EBP, participation in clinical research projects, instructions and education in analysing and discussing findings | Improvement in skills and knowledge during the study. Students stated that EBP might have an influence on increasing the quality of nursing practice. |

| Balakas [23] | 2010 | Teaching research and evidence-based practice using a service learning approach | Journal of Nursing Education | USA | Qualitative | Nursing students | A research course from a traditional format to one of evidence appraisal and synthesis, which incorporated service learning and collaborative learning | Research courses taught from an EBP perspective can provide motivation for students to incorporate research into their practice. |

| Berven [24] | 2010 | Students collaborate with nurses from a nursing home to get an evidence based practice... Fourth European Nursing Congress | Journal of Clinical Nursing | Norway | Qualitative | Nursing students | Groups of students cooperated with professionals at Løvåsen teaching nursing home in identifying clinical issues that could be feasible to investigate and develop up to date, state-of-art guidelines in relation to model for EBP | Students have developed an understanding that the process of EBP should be utilised in clinical practice. |

| Blazeck [25] | 2011 | Building EBP into the foundations of practice | Nurse Educator | USA | Qualitative | Nursing students | Assignment including choosing relevant topic and searching relevant databases | The didactic instruction of the concepts of search and the terminology of search, collaborating with a medical librarian in the teaching and the design of the assignment, the grading rubric for the students, and the quality control visual correction tool for our multiple raters, has led to success |

| Bloom [26] | 2013 | Levelling EBP content for undergraduate nursing students | Journal of professional nursing | USA | Qualitative | Nursing students | 3 undergraduate research courses designed to prepare the graduate to identify, locate, read and critically appraise evidence at the individual study, systematic review, and clinical practice guideline levels | The foundation achieved by baccalaureate graduates stand them in good stead as they pursue their clinical and academic careers. |

| Boyd [27] | 2015 | Using Debates to Teach EBP in Large Online Courses | Journal of Nursing Education | USA | Qualitative | Nursing students | Interactive debates to teach EBP skills in an online graduate course | Students remain highly engaged while practicing critical thinking, teamwork, leadership, delegation, communication skills, and peer evaluation through participation in a series of faculty-facilitated online debates. |

| Brown [28] | 2015 | The iPad: tablet technology to support nursing and midwifery student learning: an evaluation in practice | Computers, Informatics, Nursing | USA | Quantitative | Nursing students | Use of iPads | iPads reportedly improved student efficiency and time management, while improving their ability to provide patient education. Students who used iPads for the purpose of formative self-assessment appreciated the immediate feedback and opportunity to develop clinical skills. |

| Cable-Williams [29] | 2014 | An educational innovation to foster evidence-informed practice | Journal of Nursing education and Practice | Canada | Qualitative | Nursing students | Threading the concept of evidence-informed practice and relevant best practice guidelines through theory courses including their use as expected elements in clinical placements | The results of research are informing client care and a critical approach to professional practice among nursing students. |

| Callaghan [30] | 2011 | Enhancing health students’ understanding of generic research concepts using a web-based video resource | Nurse Education in Practice | England | Qualitative | Physiotherapy students | Innovative video resources | Overall, students perceived the resources as demystifying the topic of research methods through the clarification of definition and application of concepts and making sense of concepts through the analogical videos. |

| Coyne [31] | 2018 | A Comprehensive Approach to Undergraduate Nursing Students’ Research Experiences | Journal of Nursing Education | USA | Qualitative | Nursing students | Summer Research Internship (8 weeks during the summer); supporting students in a one-to-one mentorship model with the goal of building a research infrastructure facilitated by researchers and students | The programme leads to practice improvements, knowledge dissemination, and student interest in research and further professional development. It gives students hands-on experience with nursing research that has proven to be beneficial clinically while increasing student interest in research and further nursing education |

| Crawford [32] | 2011 | Using problem-based learning in web-based components of nurse education | Nurse Education in Practice | Australia | Qualitative | Nursing students | PBL approaches in online education | Students accessing online nursing subjects would seem to benefit from web-based PBL as it provides flexibility, opportunities for discussion and co-participation, encourages student autonomy, and allows construction of meaning as the problems mirror the real world. PBL also promotes critical thinking and transfer of theory to practice. |

| Davidson [33] | 2016 | Teaching EBP using game-based learning: Improving the student experience | Worldviews on evidence-based nursing | Canada | Qualitative | Nursing students | Online EBP course | Students indicated a high satisfaction with the course and student engagement was also maintained throughout the course. |

| Dawley [34] | 2011 | Using a pedagogical approach to integrate evidence-based teaching in an undergraduate women’s health course | Worldviews on evidence-based nursing | USA | Qualitative | Nursing students | Pedagogical approach aimed at [1] fostering undergraduate nursing students’ EBP competencies, and [2] identifying gaps in the literature to direct future women’s health research | The assignment was an important teaching and assessment tool for EBP. |

| Dewar [35] | 2012 | The EBP course as an opportunity for writing | Nurse Educator | USA | Qualitative | Nursing students | Writing workshops | The workshop approach provides students with a “safe” place to explore their assumptions, learn from peers, and make a leap forward along their personal learning curve as writers. |

| Doyle [36] | 2016 | Information Literacy in a Digital Era: Understanding the Impact of Mobile Information for Undergraduate Nursing Students | Book chapter in: Nursing Informatics 2016: eHealth for All: Every Level Collaboration – From Project to Realization | Canada | Qualitative | Nursing students | Use of mobile information resources | Nursing students mainly assessed mobile resources to support clinical learning, and specifically for task-oriented information such as drug medication or patient conditions/diagnoses. Researchers recommend a paradigm shift whereby educators emphasise information literacy in a way that supports evidence-based quality care. |

| Eales-Reynolds [37] | 2012 | A study of the development of critical thinking skills | Nurse Education Today | Australia | Qualitative | Nursing students and students from other healthcare disciplines | A novel web 2.0-based tool – the Web Resource Appraisal Process (WRAP) | To ensure that practice developments are based on authoritative evidence, students need to develop critical thinking skills which may be facilitated by tools such as the WRAP. |

| Elsborg Foss [38] | 2014 | A model (CMBP) for collaboration between university college and nursing practice to promote research utilization in students’ clinical placements: a pilot study | Nurse Education in Practice | Norway | Quantitative | Nursing students | CMBP (The Collaboration Model of Best Practice) | The CMBP has a potential to be a useful model for teaching RNs’ and students EBP. However, further refinement of the model is needed. |

| Epstein [39] | 2011 | Teaching Statistics to Undergraduate Nursing Students: An Integrative Review to Inform our Pedagogy | International Journal of Nursing Education Scholarship | USA | Qualitative | Nursing students | Learning strategies: Schematic links between statistics and everyday nursing practice. Technological Strategies: use of data analysis software (Excel, SPSS etc.) + use of the Internet. Group learning activities: Small group/ workshop activities. Support: student, faculty, −and laboratory support | It was found that there is limited-to-no evidence concerning the pedagogy of statistics. |

| Erichsen [40] | 2018 | Kunnskapsbasert praksis i sykepleierutdanningen | Sykepleien Forskning nr. 12,016 | Norway | Qualitative | Nursing students | Description of learning-activities including all steps in teaching and conducting EBP | Systematic training in EBP in cooperation with the practice field can have a positive impact on students’ learning. More international and Norwegian research with different study designs is necessary to increase the knowledge. |

| Florin [41] | 2012 | Educational support for research utilization and capability beliefsregarding evidence-based practice skills: a national survey of senior nursing students | Journal of AdvancedNursing | Sweden | Quantitative | Nursing students | Educational support for research utilisation and capability beliefs regarding EBP skills | Students reported high capability beliefs regarding evidence-based practice skills, but large differences were found between universities for: stating a searchable question, seeking out relevant knowledge and critically appraising and compiling best knowledge. |

| Friberg [42] | 2013 | Changing Essay Writing in Undergraduate Nursing Education Through Action Research: A Swedish Example | Nursing Education Perspectives | Sweden | Qualitative | Nursing students | Workshops and literature review | Action research was found to be a relevant procedure for changing ways of working with literature-based, bachelor degree essays. |

| Gray [43] | 2010 | Research odyssey: The evolution of a research partnership between baccalaureatenursing students and practicing nurses | Nurse education Today | USA | Quantitative | Nursing students | A research partnership between baccalaureate nursing students and nurses in two acute care hospitals | The research partnership project facilitated student learning and an appreciation of the research process. |

| Hande [44] | 2017 | Leveling Evidence-based Practice Across the Nursing Curriculum | The Journal for Nurse Practitioners - JNP | USA | Qualitative | Nursing students | The article describes evolving EBP competencies related to BSN, MSN, and DSN level.BSN level:Team-based learning, seminars, small group activities, identification of clinical problems, literature search, appraisal of literature, evidence-based project addressing a selected clinical problem for the purposes of improving clinical outcomes | Seamless transition for the development of EBP competencies for nurses at each level of education requires thought, strategically placed objectives and learning activities to be woven into the curriculum and courses. Collaboration among faculty from each educational level must occur. Teaching-learning methods must be appropriate and engaging at each level. Teaching-learning methods must challenge the student to apply and produce scholarly work for dissemination |

| Henoch [45] | 2014 | Nursing students’ experiences of involvement in clinical research: an exploratory study | Nurse Education in Practice | Sweden | Quantitative | Nursing students | Students involved as data collectors in a research project | Participation as data collectors in research has the potential to increase interest in nursing research among students. |

| Hickman [46] | 2014 | EVITEACH: A study exploring ways to optimise the uptake of EBP to undergraduate nurses | Nurse Education in Practice | Australia | Mixed method | Nursing students | EVITACH to explore strategies to increase undergraduate nursing student’s engagement with EBP and to enhance their knowledge utilisation and translation capabilities | There is little robust evidence to guide the most effective way to build knowledge utilisation and translational skills. Effectively engaging undergraduate nursing students in knowledge translation and utilisation subjects could have immediate and long term benefits for nursing as a profession and patient outcomes. |

| Jakubec [47] | 2013 | Students Connecting Critical Appraisal to EPB: A Teaching-Learning Activity for Research Literacy | Journal of Nursing Education | Canada | Qualitative | Nursing students | The Research in Practice Challenge including identifying research problems in practice, searching the literature, and critically evaluating evidence | Students value how the activity highlighted the relevance of research literacy for their practice. |

| Jalali-Nia [48] | 2011 | Effect of evidence-based education on Iranian nursing students’ knowledge and attitude | Nursing and Health Sciences | Iran | Quantitative | Nursing students | Evidence-based approach incl. The principles of EBP and PICO. The intervention and the control groups, respectively, were taught through an evidence-based and traditional approach | Significant difference between the average scores for attitude of the groups. No statistical significant difference between the average scores of knowledge. |

| Janke [49] | 2012 | Promoting information literacy through collaborative service learning in an undergraduate research course | Nurse Education Today | Canada | Qualitative | Nursing students | Service learning project where students worked in groups, and under the guidance of a nursing instructor and librarian, to answer a question posed by practice-based partners | Evaluation of the project indicated that although the project was challenging and labour intensive students felt they learned important skills for their future practice. |

| Jelsness-Jørgensen [50] | 2014 | Does a 3-week critical research appraisal course affect how students perceive their appraisal skills and the relevance of research for clinical practice? A repeated cross-sectional survey | Nurse Education Today | Norway | Quantitative | Nursing students and students from other healthcare disciplines | A 3-week critical research appraisal course | Teaching students’ practical critical appraisal skills improved their view of the relevance of research for patients, future work as well as their own critical appraisal skills. |

| Johnson [51] | 2010 | Research and EBP: using a blended approach to teaching and learning in undergraduate nurse education | Nurse Education in Practice | England | Qualitative | Nursing students | A discussion of one module team’s experience of working in a Higher Education Institution within the UK, teaching research and EBP to year two undergraduate nursing and midwifery students | The use of a blended approach to teaching and learning can be beneficial to the nurse educator in a variety of ways if careful consideration is given to the use of technology, the learning styles of the student and access to technology. |

| Jones [52] | 2011 | Teaching critical appraisal skills for nursing research | Nurse Education in Practice | Australia | Quantitative | Nursing students | An innovative and quality driven subject to improve critical appraisal and critical thinking skills | Students from both campuses showed considerable improvements in knowledge and confidence in the interpretation and analysis of research findings, in all areas after having completed the subject (assessment). |

| Keiffer [53] | 2018 | Engaging Nursing Students: Integrating Evidence-Based Inquiry, Informatics, and Clinical Practice | Nursing Education Perspectives | USA | Qualitative | Nursing students | Workshop format engages the students with technology and digital tools to promote active learning; enhance student collaboration and participation. Varying teaching modalities are employed to engage students and reinforce learning. The students are using the Melnyk et al. model as a framework; ask a clinical question using the PICOT criteria, develop strategies to search, appraise research, use evidence to inform clinical decision-making, design a change, and disseminate the evidence | Well-designed curricula require imagination, creativity, and team effort between theory and clinical faculty. Designing projects applicable to the clinical site provides an avenue for students to engage in EBP while demonstrating the achievement of course learning outcomes. |

| Kiekkas [54] | 2015 | Nursing students’ attitudes toward statistics: Effect of a biostatistics course and association with examination performance | Nurse Education Today | Greece | Quantitative | Nursing students | Biostatistics course | Students’ attitudes toward statistics can be improved through appropriate biostatistics courses, while positive attitudes contribute to higher course achievements and possibly to improved statistical skills in later professional life. |

| Kyriakoulis [10] | 2016 | Educational strategies for teaching EBP to undergraduate health students: systematic review | Journal of Educational Evaluation for Health Professions | USA | Quantitative | Nursing students and students from other healthcare disciplines | Lectures, tutorials, workshops, conferences, journal clubs, and online sessions or combination of these | Multifaceted approach may be best suited when teaching EBM to health students. |

| Leach [55] | 2016 | The impact of research education on student nurse attitude, kill and uptake of evidence | Journal of Clinical Nursing | Australia | Quantitative | Nursing students | Research education programme delivered as two eight-week courses in the third year of education | Research education may have a significant effect on nursing students’ research skills and use of EBP, and minimise barriers to EBP post-education. |

| Lewis [56] | 2016 | Diminishing Effect Sizes with Repeated Exposure to EBP Training in Entry-Level Health Professional Students: A Longitudinal Study | Physiotherapy Canada | Canada | Quantitative | Physiotherapy students and students from other healthcare disciplines | Two sequential EBP courses. 1. EBP course was aimed at developing foundational knowledge of and skills in the five steps in EBP. 2. EBP course designed to teach students to apply the steps | Knowledge and relevance changed most meaningfully (i.e., showed the largest effect size) for participants with minimal prior exposure to training. Changes in participants’ confidence and attitudes may require a longer timeframe and repeated training exposure. |

| Liou [57] | 2013 | Innovative strategies for teaching nursing research in Taiwan | Nursing Research | Taiwan | Quantitative | Nursing students | Innovative Teaching Strategies for a research course including teamwork, laboratory sessions on how to search for published research articles, experiments and mini research projects (experimental group).Didactic lecture, textbook readings, and research article critique (control group) | This study confirmed that using innovative teaching strategies in nursing research courses enhances student interest and enthusiasm about EBP. |

| Laaksonen [58] | 2013 | Journal club as a method for nurses and nursing students’ collaborative learning: a descriptive study | Health Science Journal | Finland | Quantitative | Nursing students | A six-phased journal clubmodel | Journal clubs support competences and discussion required for producing evidence-based care and can be recommended as learning methods for nurses’ and nursing students’ collaborative learning. |

| Malik [59] | 2017 | Using pedagogical approaches to influence evidence-based practice integration - processes and recommendations: findings from a grounded theory study | Journal of Advanced Nursing (JAN) | Australia | Qualitative | Nurse academics (regarding nursing students) | Various pedagogical approaches to influence evidence-based practice education; lectures, tutorials, laboratory work, online activities, videos, scenarios, and assignments. Emphasising information literacy and critical appraisal skills. Some use flipped classroom approach, problem-based learning, virtual simulated environment, and inquiry-based learning to facilitate students’ learning | Academics attempted to contextualise EBP by engaging students with activities aiming to link evidence to practice and with the EBP practice. Engaging students with the EBP process in practice context is imperative to increase their EBP competence. Some key challenges (limited time, insufficient resources, heavy workload, students’ disengagement, and limited awareness of effective teaching methods) require the adoption of appropriate strategies to ensure future nurses are well prepared in the paradigm of evidence-based practice |

| Mattila [60] | 2014 | Journal club intervention in promoting evidence-based nursing: Perceptions of nursing students | Nurse Education in Practice | Finland | Quantitative | Nursing students | Journal clubs | Students were not able to utilise the studies to the same extent as they learn from them. Age, work experience and participation in research and development activities were connected to learning. |

| McCurry [61] | 2010 | Teaching undergraduate nursing research: a comparison of traditional and innovative approaches for success with millennial learners | Journal of Nursing Education | USA | Mixed method | Nursing students | Innovative assignments that included interactive learning, group work, and practical applications | Students’ positive responses to the innovative learning strategies evaluated in this study support the nursing profession’s need to continue to develop activities that engage millennial students and enable them to clearly articulate the value of the research practice link vital to evidence-based nursing practice. |

| Milner [62] | 2017 | The PICO Game: An Innovative Strategy for Teaching Step 1 in Evidence-Based Practice | Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing | USA | Qualitative | Nursing students | Game | Games build and strengthen skills to frame practice questions in a searchable format (PICO). The method for teaching how to build PICO questions is the same regardless of participant education level or years of practice |

| Moch [63] | 2010 | Part II. Empowering grassroots EBP: a curricular model to foster undergraduate student-enabled practice change | Journal of professional nursing | USA | Qualitative | Nursing students | The “Student-Enabled Practice Change Curricular Model” | As the preliminary data reported here suggest, nurse educators have the power to promote practice change by enabling socially meaningful partnerships between students and practicing nurses that could percolate change up from the lowest points in the power hierarchy. |

| Moch [64] | 2010 | Part I. Undergraduate nursing EBP education: envisioning the role of students... first of a three-part series | Journal of professional nursing | USA | Qualitative | Nursing students | Various pedagogical strategies targeted towards teaching EBP | The literature reviewed in this article that describes more active roles for students in clinical settings, albeit scant, suggests that allowing students to interact in on-going and meaningful ways with practicing nurses may remove or mitigate barriers to the adoption of EBP among practicing nurses. |

| Morris [65] | 2016 | The use of team-based learning in a second year undergraduate pre-registration nursing course on evidence-informed decision making | Nurse Education in Practice | England | Mixed method | Nursing students | Evidence-informed decision making course | Team-based learning was shown to be an effective strategy that preserved the benefits of small group teaching with large student groups. |

| Morris [66] | 2010 | Pilot study to test the use of a mobile device in the clinical setting to access evidence-based practice resources | World Views on Evidence-based Nursing | England | Quantitative | Nursing and physiotherapy students | Use of mobile device to access EBP resources in clinical setting | Students reported improvement in knowledge and skills in relation to EBP and appraisal of clinical guidelines. However a low level of utilisation of the mobile device in the clinical setting due to access to the internet and small screens. |

| Nadelson [67] | 2014 | Evidence-Based Practice Article Reviews Using CASP Tools: A Method for Teaching EBP | Worldviews on evidence-based nursing | USA | Qualitative | Nursing students | EBP Article Reviews using CASP Tools | Using the CASP Tools help students organise their reviews and learn about valuable resources. In addition, working as a group member helps foster involvement, motivation, and interest in the processes of evaluating evidence effectively. |

| Nadelson [68] | 2014 | Online resources: fostering students EBP learning through group critical appraisals | World views on Evidence-based Nursing | USA | Qualitative | Nursing students | Students in dyads or triads reviewed and evaluated one EBP related website | Having students work in groups to critically appraise websites that help promote EBP can enhance collaboration and knowledge about EBP resources. |

| Niven [69] | 2013 | Making research real: Embedding a longitudinal study in a taught research course for undergraduate nursing students | Nurse Education Today | USA | Qualitative | Nursing students | To facilitate students learning research theory and methodology by conducting a “real-life” research study in a local retirement community | We knew we had succeeded in our efforts to change student perceptions about learning research when we read a comment from one student who had completed the revised research course. |

| O’Neil [70] | 2016 | A new model in teaching undergraduate research: A collaborative approach and learning cooperatives (CALC) | Nurse Education in Practice | USA | Qualitative | Nursing students | A quality improvement study using the CALC Model | Universities and hospital administrators, nurses, and students benefit from working together and learning from each other. |

| Odell [71] | 2011 | Teaching EBP: The Bachelor of Science in Nursing Essentials at Work at the Bedside | Journal of professional nursing | USA | Qualitative | Nursing students | A group project for students that involved collaboration with the health science reference librarian and nurse managers in the clinical agencies | The learning experience is a shared partnership between the clinical agency, the faculty, and the health science librarian to assist senior nursing students in the last semester of their baccalaureate degree programme to synthesise and use the knowledge, skills, and attitudes that promote patient safety and optimal outcomes |

| Oja [72] | 2011 | Using problem-based learning (PBL) in the clinical setting to improve nursing students’ critical thinking: an evidence review | Journal of Nursing Education | USA | Qualitative | Nursing students | PBL | The studies reviewed indicate a positive relationship between PBL and improved critical thinking in nursing students. |

| Pennington [73] | 2010 | EBP partnerships: building bridges between education and practice | Nursing Management | USA | Qualitative | Nursing students | Teaming nursing students with staff nurses working on EBP projects | Students were able to learn how evidence is utilised in the practice settings. |

| Phelps [74] | 2015 | Introducing Information Literacy Competency Standards for Nursing | Nurse educator | USA | Qualitative | Nursing students | Information Literacy Competency Standards for Higher Education (ILCSHE) | Nursing librarians are the Information Literacy experts who help to integrate these skills into nursing education |

| Phillips [75] | 2014 | Creative classroom strategies for teaching nursing research | Nurse Educator | USA | Qualitative | Nursing students | Kaleidoscopes for discussion of perspectives, crossword puzzles to reinforce terminology, scavenger hunt to relate concepts to the real world, cookie experiment to have an overview of the research process and paradigms, individual reaction time, and a music activity to reinforce elements of design and sampling | Student feedback was positive. These strategies help faculty communicate important concepts of nursing research in a way that is meaningful and fun. |

| Pierce [76] | 2016 | The e-Poster Conference: An Online Nursing Research Course Learning Activity | Journal of Nursing Education | USA | Qualitative | Nursing students | e-poster conference | From all accounts, the conference was rated as positive, providing nursing students with opportunities to (a) view studies and projects from a wider nursing science audience, (b) foster the development of important evaluation and communication skills, and (c) be exposed to evidence that could be translated into their practice. |

| Putnam [77] | 2011 | Conquering EBP using an embedded librarian and online search tool | Journal of Nursing | USA | Qualitative | Nursing students | Embedded librarians + online search tools to assist students in the development and mastery of effective search techniques | Embedded librarians and online search tools are useful to students as they develop information literacy skills related to searching for and screening information. Using these strategies for formative and summative assignments allows students to develop additional information literacy skills needed to integrate, analyse, apply, and present information. |

| Raines [78] | 2016 | A collaborative strategy to bring evidence into practice | Worldviews on evidence-based nursing | USA | Qualitative | Nursing students | A teaching strategy which combines the clinical experience of nurses with nursing students’ evolving skills in reading, critiquing, and analysing research-based literature | The teaching strategy presents a win-win situation in which students become engaged with clinical nurses in a unit-based project. |

| Raurell-Torreda [79] | 2015 | Simulation-based learning as a tactic for teaching EBP | Worldviews on evidence-based nursing | Spain | Qualitative | Nursing students | Simulation-based learning (SBL) modules covering nursing competencies | The simulation helped to educate nursing students in applying EBP. |

| Reicherter [80] | 2013 | Creating disseminator champions for EBP in health professions education: An educational case report | Nurse Education Today | USA | Qualitative | Nursing and physiotherapy students | A model for developing EBP practitioners: Phase 1. Preparing students how to read, analyse and discuss levels of evidence. Phase 2. Focus on developing dissemination skills by requiring students to complete a clinical case report project. Phase 3. Review outcomes of the project and phase 4. Provide mechanisms of future plans | Increased student participation, Clinical instructors and faculty scholarship, and dissemination of EBP. Additional educational benefits derived from this project included, 1) broader participation of clinical settings, 2) requests by additional clinics to participate for purposes of developing EBP and scholarly presentation skills of clinicians, and 3) increased opportunity for academic faculty to continue engagement in contemporary clinical practice. |

| Revaitis [81] | 2013 | FaceTime: a virtual pathway between research and practice | Nurse Educator | USA | Qualitative | Nursing students | FaceTime videoconference | FaceTime videoconferencing provides numerous benefits for students and provides a virtual connection to link the classroom with the practice world. |

| Roberts [82] | 2011 | Finding and using evidence in academic assignments: The bane of student life | Nurse Education in Practice | England | Quantitative | Nursing students | Specific sessions on literature searching skills which were delivered early on in the programme | The findings indicate that students value specific teaching sessions (taught by members of library staff) delivered at the beginning of the programme but it seems that more work is required by educators in order to help students to associate literature searching skills with nursing practice. |

| Rodriguez [83] | 2012 | Action Research as a Strategy for Teaching an Undergraduate Research Course | Journal of Nursing Education | USA | Qualitative | Nursing students | Teaching of Action Research instead of teaching traditional research course methods | The students learned how to identify a research problem and move through the steps of the research process using action research. |