Abstract

Background

Phosphorus (P) deficiency in soil is a worldwide issue and a major constraint on the production of sorghum, which is an important staple food, forage and energy crop. The depletion of P reserves and the increasing price of P fertilizer make fertilizer application impractical, especially in developing countries. Therefore, identifying sorghum accessions with low-P tolerance and understanding the underlying molecular basis for this tolerance will facilitate the breeding of P-efficient plants, thereby resolving the P crisis in sorghum farming. However, knowledge in these areas is very limited.

Results

The 29 sorghum accessions used in this study demonstrated great variability in their tolerance to low-P stress. The internal P content in the shoot was correlated with P tolerance. A low-P-tolerant accession and a low-P-sensitive accession were chosen for RNA-seq analysis to identify potential underlying molecular mechanisms. A total of 2089 candidate genes related to P starvation tolerance were revealed and found to be enriched in 11 pathways. Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analyses showed that the candidate genes were associated with oxidoreductase activity. In addition, further study showed that malate affected the length of the primary root and the number of tips in sorghum suffering from low-P stress.

Conclusions

Our results show that acquisition of P from soil contributes to low-P tolerance in different sorghum accessions; however, the underlying molecular mechanism is complicated. Plant hormone (including auxin, ethylene, jasmonic acid, salicylic acid and abscisic acid) signal transduction related genes and many transcriptional factors were found to be involved in low-P tolerance in sorghum. The identified accessions will be useful for breeding new sorghum varieties with enhanced P starvation tolerance.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12870-019-1914-8) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Sorghum, Transcriptome analysis, Phosphorus starvation, Candidate genes, Malate, Root development

Background

Phosphorus (P) is an essential macronutrient for plant growth and development and is considered to regulate energy metabolism, enzymatic reactions, and signal transduction processes [1, 2]. Inorganic orthophosphate (Pi) is the primary source of P for plants. However, Pi can be readily fixed with aluminum and iron in acidic soil and with calcium in alkaline soil [3]. Since Pi content in soil is too low to satisfy the requirements for plant growth, excessive quantities of P fertilizer must be applied, which possibly cause environmental pollution [4, 5]. The global rock phosphate reserve is a nonrenewable resource, and approximately 70% of cultivated lands worldwide suffer from P deficiency [6]. Therefore, the development of plants that are better adapted to low-P environments is a sustainable and economical approach in agricultural production.

To adapt to persistent P deficiency, plants have developed several strategies, including changing root morphology [7], exuding organic acids and phosphatases [6], and establishing symbiotic relationships with arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi [8]. These strategies in plants are dependent on changes in gene expression. Numerous genes related to low-P stress have been identified and recently reported in plants [9–11]. The phosphate transporter1 (PHT1) gene family participates in the uptake of Pi from the soil. As a member of the PHT1 family, PHT1;1 plays an important role in Pi uptake from the soil [12–15]. Moreover, many transcription factors (TFs) could regulate the expression of PHT1;1, such as phosphate starvation response 1 (PHR1) [16], WRKY75 [17], WRKY45 [18] and MYB domain protein 62 (MYB62) [19]. The PHO1 family plays an important role in Pi translocation from root to shoot [20–22] and is downregulated by WRKY6 and WRKY42 [23, 24]. Additionally, miR399, miR827 [25–27] and the zinc finger TF ZAT6 [28] modulate phosphate homeostasis. Most of these factors were identified in model plants, such as Arabidopsis and rice. In sorghum, however, only the multiple homologs of the phosphorus starvation tolerance 1 (PSTOL1) gene have been identified, which may be associated with changes in root morphology and root system architecture under low-P conditions [29].

Rice, maize, wheat and sorghum are important graminaceous crops. Among them, P uptake by sorghum was only lower than that by rice [30]. Furthermore, sorghum is not only a staple food for more than 500 million people but also a popular forage crop [29, 31, 32]. Given its high yield, extensive use and excellent adaptation to harsh environmental conditions, sorghum was planted specifically in arid and semiarid regions [33, 34]. It has been suggested that the grain yield of sorghum is highly correlated with P levels [35], and approximately 0.2% of the dry weight of this crop is contributed by P [36]. Although many genes and signal pathways related to low-P stress have been identified in rice [37], wheat [38] and maize [39] through transcript profiling, the genes and pathways related to low-P stress in sorghum remain unclear.

In this study, the P starvation tolerance of 29 sorghum accessions was evaluated. Accessions 12484 and 13443 were identified as low-P-tolerant and low-P-sensitive accessions, respectively. The gene expression in the roots of the two accessions, which both underwent P treatment for 8 days, was analyzed by mRNA sequencing (RNA-seq). Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) related to P starvation tolerance were identified through transcriptome profiles. Gene ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) analyses were performed. Moreover, the effect of malate application on root development in sorghum was investigated. The findings reported in this work increase our understanding of the molecular mechanisms of P starvation in sorghum.

Methods

Pot experiments

To evaluate the P starvation tolerance of the 29 sorghum accessions, pot experiments were performed according to Hufnagel et al. [29]. Generally, the sorghum seeds were sown in plastic pots in a greenhouse in the experimental station of Nanjing Agricultural University in 2015 and 2016. The Olsen-P of soil used in the experiments was 1.25 μg/g. After 7 days, two accessions were allowed to continue growing under sufficient-P (30 μg/g) and low-P (3 μg/g) conditions in each pot for 40 days.

The roots of sorghum were harvested and cleaned carefully after breaking the pots. Subsequently, electronic images of root morphology were captured using an EPSON scanner and analyzed by WinRHIZO software. Roots and shoots were heated at 105 °C for 30 min and then oven-dried at 65 °C for 72 h. The samples were weighed and milled. A portion of the milled samples was digested with HNO3. The total P content of shoots was determined by ICP-OES (PerkinElmer, Optima 8000, USA). The relative length of roots (RLR) was expressed by the ratio of the root length of plants treated with low P to that treated with sufficient P. The relative surface area of root (RSAR), relative average diameter of root (RADR), relative volume of root (RVR), relative number of root tips (RNRT), relative dry weight of root (RDWR), relative dry weight of shoot (RDWS) and relative P content of shoot (RPCS) were calculated using similar methods.

Hydroponic experiments

To determine the duration of the low-P treatment and facilitate the harvest of roots for RNA-seq, hydroponic experiments were performed according to Hufnagel et al. [29]. Sorghum seeds were sterilized with 75% ethanol for 5 min, dried, and then germinated in moistened filter paper. After 3 days, seedlings with similar growth vigor were transplanted into distilled water. When the seedlings reached the three-leaf stage, they were subjected to sufficient-P conditions (Hoagland (5 mmol/L Ca(NO3)2·4H2O, 5 mmol/L KNO3, 2 mmol/L MgSO4·7H2O, 0.025 mmol/L Fe-EDTA, 1 μmol/LH3BO3, 1 μmol/L MnSO4·H2O, 1 μmol/L ZnSO4·7H2O, 0.5 μmol/L CuSO4·5H2O, and 0.005 μmol/L (NH4)6Mo7O24·4H2O) with 1.0 mmol/L KH2PO4) and low-P conditions (Hoagland with 1 μmol/L KH2PO4 and 1.0 mmol/L KCl) for 2 weeks. The nutrient solution with a pH of 5.8 ± 0.1 was replaced every 3 days. The seedlings were cultured in a growth chamber under a 12 h/12 h (day/night) photoperiod and a temperature cycle of 28 °C/22 °C (day/night). Each treatment was replicated three times. Roots and shoots of plants subjected to treatment with different P concentrations (sufficient-P and low-P conditions) were harvested every 2 days and used for measuring the ratio of root dry weight to shoot dry weight (R/S ratio) and gene expression analysis.

RNA isolation and transcriptome sequencing

Total RNA was isolated using TRIZOL (Invitrogen, USA) from the roots of accessions 12484 and 13443 harvested after 8 days of P treatment. The quality and integrity of the RNA were checked by an Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 system (Agilent Technologies, CA, USA). The total RNA concentration was assessed using a QUBIT RNA ASSAY KIT (Invitrogen, USA). mRNA was enriched by the NEBNext® Poly(A) mRNA Magnetic Isolation Module (Invitrogen, USA), and the mRNA molecules were fragmented and subsequently used in first- and second-strand cDNA syntheses. The cDNA was subsequently subjected to terminal repair and poly (A) and unique adapter ligation. Prior to sequencing, the cDNA fragments were amplified and purified. The purified amplification products were sequenced on an Illumina Hiseq 2500 platform (CapitalBio Technology, Beijing, China).

RNA-seq data analysis

The original sequencing data were defined as raw reads. The clean reads were generated from the raw reads after removing the low-quality reads, mismatches, and adaptor sequences. The sequences of the clean reads were aligned with the sorghum transcript sequence (Ensembl, http://plants.ensembl.org/index.html). The perfectly matching sequences were used for further analyses. The gene expression levels were normalized by fragments per kilo base of transcript per million fragments mapped (FPKM) and analyzed using Cufflinks software (http://cole-trapnell-lab.github.io/cufflinks/) [40, 41]. DEGs were analyzed using Cuffdiff software [42]. The DEGs were identified based on the following criteria: the absolute value of the Log fold change had to be ≥1, the P value adjusted using the false discovery rate (FDR) method had to be ≤0.05, and three biological replicates had to be used.

DEGs were subjected to GO analyses, as follows: 1) all DEGs were mapped to GO terms in the database (http://www.geneontology.org/); 2) the gene numbers of each term were calculated; 3) the hypergeometric test was used to analyze the significantly enriched GO terms in the DEGs; 4) the input frequency represented the ratio of the number of DEGs with annotation to the total number of DEGs, and the background frequency represented the ratio of the number of genes with annotation to the total number of genes.

To analyze the pathways that were significantly associated with DEGs, we used the same method to blast the DEGs with the KEGG database (http://www.genome.jp/kegg/pathway.html), which is a major public pathway-related database. Then, the gene numbers of each pathway were calculated, and the hypergeometric test was used to analyze the significantly enriched pathways.

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted from each sample by using the Plant RNA Extract Kit (TIANGEN, Beijing, China), and approximately 0.5 μg of total RNA was used for cDNA synthesis using HiScript® II Q RT SuperMix for qPCR (+gDNA wiper) (Vazyme, Nanjing, China). After diluting the cDNA reaction mixture five times, 2 μL of the reaction mixture was used as template in a 20-μL reaction system. In addition, the reaction system contained 0.8 μL of 10 μmol/L gene-specific primers (Additional file 1: Table S1) and 10 μL of AceQ® qPCR SYBR® Green Master Mix (Low ROX Premixed) (Vazyme, Nanjing, China). qRT-PCR was performed on an ABI 7500 real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Forster City, CA, USA), and the data were analyzed using the ABI 7500 Sequence Detection System software v.1.4. A sorghum constitutive expression gene, 18S rRNA, was used as the reference gene for normalization. Three technical replicates were carried out for each sample.

Malate application experiments

Accession 13443 was used as the experimental material. Hydroponic experiments were performed according to Mora-Macías et al. [43]. After seeds germinated in distilled water for 1 week, the seedlings displaying similar growth vigor were picked and subjected to sufficient P (1.0 mmol/L KH2PO4) with and without 1.0 mmol/L malate or low P (1.0 μmol/L KH2PO4) with and without malate for 2 weeks. Each treatment was replicated three times. The lengths of the primary root and root tips were measured.

Results

Identification of the low-P-tolerant accession (12484) and the low-P-sensitive accession (13443)

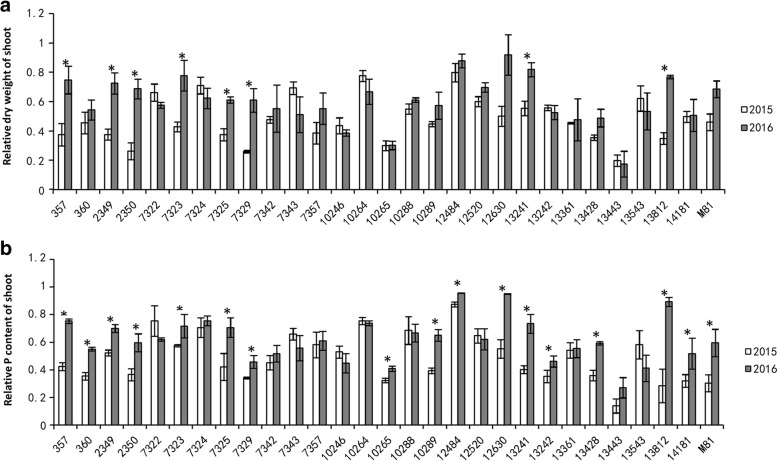

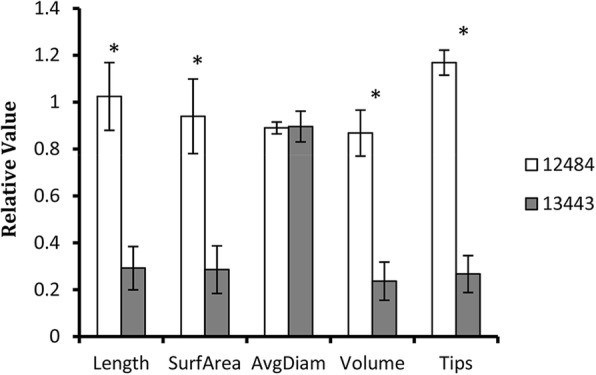

It is well documented that the biomass of the shoot is greatly reduced by P-deficient treatment [44, 45], and shoot biomass is a good indicator of plant response to P deficiency tolerance. We expected that the shoot biomass of the low-P-tolerant accession would be less negatively affected by low-P treatment than by sufficient-P treatment; thus, the low-P-tolerant accession would display a high RDWS, and vice versa for the low-P-sensitive accession. A total of 29 sorghum accessions were grown in both low-P and sufficient-P conditions. These accessions displayed great variability in RDWS with values ranging from 0.2 to 0.9. The RDWS results were generally consistent between two independent experiments carried out in two consecutive years (2015 and 2016). Among them, accession 12484 displayed the highest RDWS, while accession 13443 showed the lowest values in both years (Fig. 1). Therefore, we selected accessions 12484 and 13443 as the low-P-tolerant and low-P-sensitive accessions, respectively, for further analysis. Meanwhile, the root morphology of each accession was tested. The RPCS showed a significant positive correlation with RDWS, and there were significant positive correlations with RDWR, RNRT, RSAR, RLR, and RVR (Table 1). Moreover, the differences in RNRT, RSAR, RLR and RVR between the selected accessions 12484 and 13443 were significant (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Physiological changes of sorghum accessions in response to low-P stress. a and b Relative dry weight of shoot (a) and relative P content of shoot (b) of different accessions from 2015 and 2016 experiments. Asterisks denote statistically significant differences between the results from two independent experiments (P < 0.05). Bars represent the standard error of the mean (n = 3)

Table 1.

Correlation analysis between root morphology and P starvation tolerance. Asterisks note statistically significant differences between control and treatment groups (P < 0.05), double asterisks note statistically significant differences between control and treatment groups (P < 0.01). Bars represent the standard error of the mean (n = 3)

| 2015/2016 | Relative length of root | Relative surface area of root | Relative average diam of root | Relative volume of root | Relative number of root tips | Relative dry weight of root | Relative dry weight of shoot | Relative P content of shoot |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relative length of root | 1 | 0.893**/0.948** | 0.101/0.137 | 0.719**/0.812** | 0.918**/0.840** | 0.969**/0.422** | 0.539**/0.475** | 0.572**/0.507** |

| Relative surface area of root | 0.893**/0.948** | 1 | 0.486**/0.435** | 0.953**/0.954** | 0.695**/0.694** | 0.977**/0.529** | 0.591**/0.552** | 0.521**/0.578** |

| Relative average diam of root | 0.101/0.137 | 0.486**/0.435** | 1 | 0.678**/0.665** | −0.129/−0.208 | 0.315/0.444* | 0.429*/0.360 | 0.138/0.342 |

| Relative volume of root | 0.719**/0.812** | 0.953**/0.954** | 0.678**/0.665** | 1 | 0.468**/0.488** | 0.868**/0.587** | 0.543**/0.567** | 0.426**/0.596** |

| Relative number of root tips | 0.918**/0.840** | 0.695**/0.694** | −0.129/−0.208 | 0.468**/0.488** | 1 | 0.821**/0.405* | 0.485**/0.495** | 0.542**/0.524** |

| Relative dry weight of root | 0.969**/0.422** | 0.977**/0.529** | 0.315/0.444* | 0.868**/0.587** | 0.821**/0.405* | 1 | 0.582**/0.647** | 0.560**/0.687** |

| Relative dry weight of shoot | 0.539**/0.475** | 0.591**/0.552** | 0.429*/0.360 | 0.543**/0.567** | 0.485**/0.495** | 0.582**/0.647** | 1 | 0.797**/0.876** |

| Relative P content of shoot | 0.572**/0.507** | 0.521**/0.578** | 0.138/0.342 | 0.426**/0.596** | 0.542**/0.524** | 0.560**/0.687** | 0.797**/0.876** | 1 |

* menas P < 0.05; ** means P < 0.01

Fig. 2.

Effect of low-P stress on root morphologies of sorghum accessions 12484 and 13443 grown in soil. Asterisks denote statistically significant differences between the two accessions (P < 0.05) by Student’s t-test. Bars represent the standard error of the mean (n = 3)

Increased P content in the shoot accounts for enhanced tolerance to low P

Plants can achieve tolerance to low P availability by optimizing the P utilization and/or by improving P acquisition from the soil [46]. To understand whether the variations in low-P tolerance of the 29 sorghum accessions were due to their improved ability to acquire P, we determined the P content in the shoot tissues of these accessions grown under both low-P and sufficient-P conditions. Figure 1b shows that low-P-tolerant accessions displayed high P content, while sensitive accessions displayed low P content. In general, there was a good correlation between RPCS and RDWS, with correlation coefficients equal to 0.797 and 0.876 in 2015 and 2016, respectively, indicating variation in P acquisition ability accounts for the variation in low-P tolerance in these selected sorghum accessions.

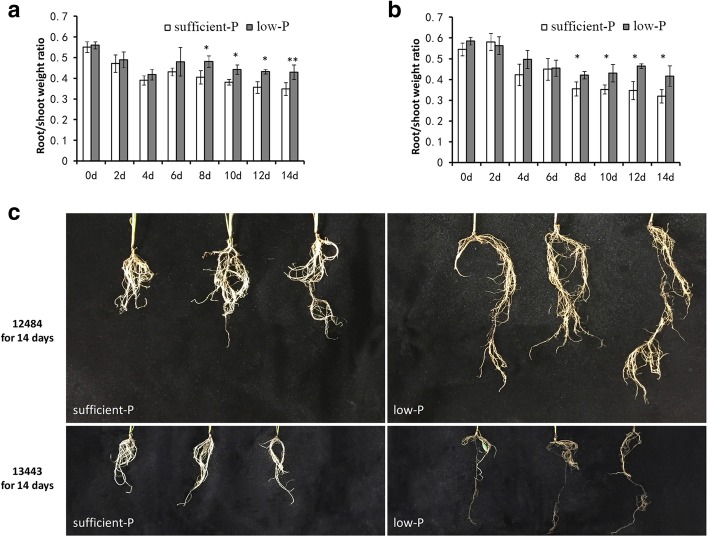

Determining optimal sampling time for RNA-seq

To analyze the transcript profiles of low-P-tolerant and -sensitive accessions in responding to low P, we first determined the optimal sampling time by analyzing the R/S of sorghum grown hydroponically under low P or sufficient P supply. An increasing R/S ratio is a hallmark indicator of plant responses to P-deficient conditions [44, 47]. The R/S ratio of accession 12484 seedlings grown under low-P conditions was not significantly different than that grown under sufficient-P conditions after six successive days of treatment (Fig. 3). In contrast, from the 8th to the 14th day after low-P treatment, the R/S ratio was significantly higher than that of plants grown under sufficient-P conditions. Moreover, a similar trend was found in accession 13443. Therefore, the roots of seedlings grown under low P and sufficient P for 8 days were sampled for RNA-seq analysis.

Fig. 3.

Physiological responses of sorghum accessions 12484 and 13443 to low-P stress in the hydroponic system. a and b Root/shoot dry weight ratio of accession 12484 (a) and accession 13443 (b). c Photographs of representative plants. Asterisks denote significant differences between control and treatment groups by Student’s t-test (* means P < 0.05; ** means P < 0.01). Bars represent the standard error of the mean (n = 3)

RNA-seq analysis and de novo assembly

The libraries from the roots of accessions 12484 and 13443 grown under low-P and sufficient-P conditions for 8 days were sequenced using Illumina high-throughput sequencing technology. Approximately 512 million raw reads were generated, and 492 million clean reads were obtained after cleaning and quality checks (Table 2). The clean rates and the Q20 and Q30 values of the samples reached up to 96, 97, and 93%, respectively, indicating the high quality of the sequencing results. Approximately 87% of the total clean reads were mapped to the sorghum reference sequence Sorghum_bicolor.Sorbi1.33 (Ensembl; http://plants.ensembl.org/index.html), > 97.5% of which were uniquely mapped reads.

Table 2.

Summary of RNA-seq data and de novo assembly

| accession | Sample | Raw reads number | Clean reads number | Clean rate(%) | Q20(%) | Q30(%) | Mapped reads rate(%) | Uniquely mapped reads rate(%) | Gene Number | Transcript Number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 13443 | sufficient P_1 | 44920566 | 43070114 | 95.88 | 97.62 | 93.31 | 89.36 | 97.45 | 25489 | 33223 |

| sufficient P_2 | 42063644 | 40616024 | 96.56 | 97.76 | 93.63 | 85.21 | 97.43 | 26110 | 33633 | |

| sufficient P_3 | 30906152 | 29804314 | 96.43 | 97.73 | 93.55 | 88.59 | 97.54 | 24579 | 31528 | |

| low P_2 | 37808338 | 36157312 | 95.63 | 97.6 | 93.28 | 88.36 | 97.62 | 24765 | 31741 | |

| low P_3 | 48044802 | 46225956 | 96.21 | 97.71 | 93.54 | 87.75 | 97.66 | 25942 | 33394 | |

| low P_5 | 51611204 | 49267030 | 95.46 | 97.54 | 93.16 | 89.32 | 97.41 | 25331 | 33283 | |

| 12484 | sufficient P_1 | 41036008 | 39463806 | 96.17 | 97.69 | 93.48 | 86.76 | 97.46 | 25018 | 32024 |

| sufficient P_2 | 44683368 | 42943164 | 96.11 | 97.71 | 93.56 | 84.96 | 97.37 | 25196 | 32012 | |

| sufficient P_3 | 43627358 | 41878828 | 95.99 | 97.67 | 93.46 | 84.02 | 97.46 | 25308 | 32157 | |

| low P_1 | 41144016 | 39708924 | 96.51 | 97.76 | 93.63 | 88.35 | 97.55 | 24587 | 31120 | |

| low P_2 | 46931232 | 45299694 | 96.52 | 97.75 | 93.61 | 86.93 | 97.52 | 24935 | 31395 | |

| low P_5 | 39105304 | 37577298 | 96.09 | 97.65 | 93.39 | 87.27 | 97.61 | 24670 | 31545 |

Screening of the candidate genes related to P starvation tolerance in sorghum

Comparing the transcripts of sorghum grown under low-P conditions with those under sufficient-P conditions, a total of 2627 DEGs in accession 13443 and 5240 DEGs in accession 12484 were identified. Among these DEGs, 1815 were upregulated and 812 were downregulated in accession 13443, while 2211 and 3029 DEGs were upregulated and downregulated in accession 12484, respectively (Fig. 4a). Moreover, 735 DEGs were upregulated and 414 DEGs were downregulated in both accessions (Fig. 4b). Interestingly, the numbers of DEGs, regardless of their upregulation or downregulation, in accession 13443 were lower than those in accession 12484. Here, the 5275 nonredundant DEGs and the 1296 overlapping DEGs, for a total of 6571 DEGs, were identified as DEGs in response to low-P stress in sorghum.

Fig. 4.

Comparison of the number of DEGs. 1: low-P-sensitive accession 13443; 2: low-P-tolerant accession 12484; L: low P; C: sufficient P. a The number of differentially expressed genes in each part. b Venn diagram illustrating the genes of the two accessions in response to low-P stress. c Response of DEGs to low-P stress and different accessions under low-P conditions

A total of 4762 nonredundant DEGs, of which 2237 were upregulated and 2525 were downregulated, were identified in the low-P-tolerant accession 12484 vs. the low-P-sensitive accession 13443 under low-P conditions (Fig. 4a). During our study, these 4762 nonredundant DEGs were identified as DEGs in different accessions under low-P conditions.

Finally, comparing these two groups, a total of 2089 common DEGs were found (Fig. 4c), meaning these genes were not only differentially expressed in response to low-P stress but also differentially expressed in different accessions under low-P stress. These DEGs were identified as the candidate genes related to P starvation tolerance in sorghum.

qRT-PCR verification

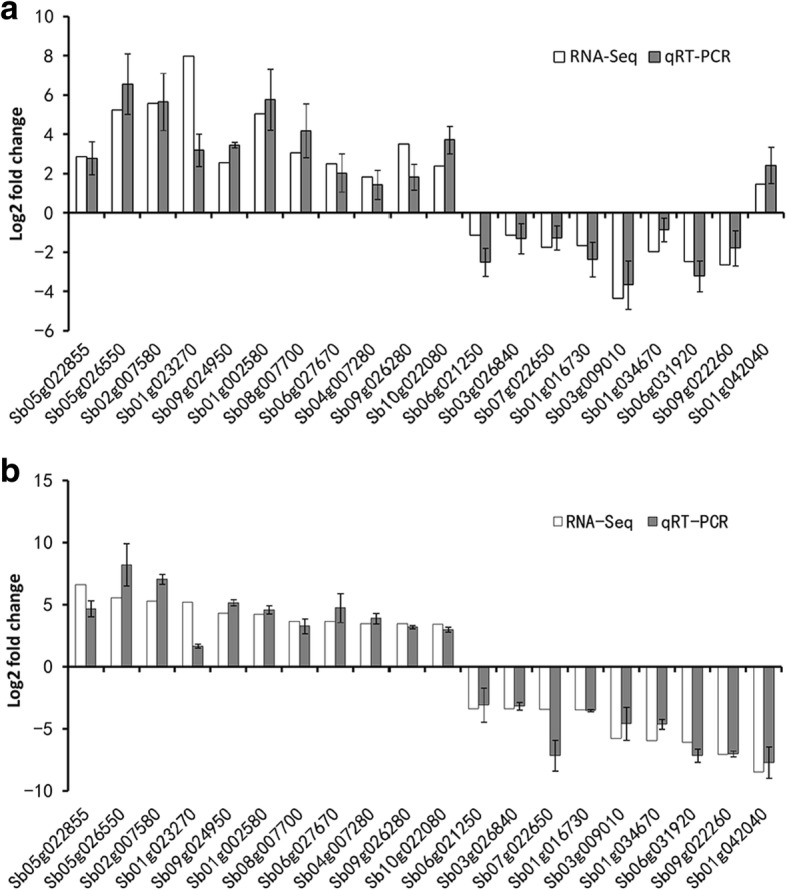

To verify the RNA-seq results, we determined the abundance of 20 randomly selected DEGs by qRT-PCR assay. The qRT-PCR assay showed that Sb05g022855, Sb05g026550, Sb02g007580, Sb01g023270, Sb09g024950, Sb01g002580, Sb08g007700, Sb06g027670, Sb04g007280, Sb09g026280 and Sb10g022080 were upregulated, whereas Sb06g021250, Sb03g026840, Sb07g022650, Sb01g016730, Sb03g009010, Sb01g034670, Sb06g031920 and Sb09g022260 were downregulated in both accessions (Fig. 5). Additionally, Sb01g042040 was downregulated in accession 12848 but was upregulated in accession 13443. These results were consistent with the data obtained from the RNA-seq analysis, indicating the reliability of the RNA-seq results.

Fig. 5.

Validation of transcript abundance obtained from RNA-seq using qRT-PCR. Twenty randomly chosen genes were used for validation. a and b Relative expression by RNA-seq and qRT-PCR of accession 13443 (a) and accession 12484 (b). Bars represent the standard error of the mean (n = 3)

Annotation and function classification of DEGs

To evaluate the potential functions of those DEGs, GO analyses were performed on the DEGs identified during each comparison. Among the DEGs identified in response to low-P stress, 1578 of the 2627 DEGs in accession 13443 were assigned to at least one GO term, whereas 3147 of the 5240 DEGs in accession 12484 were assigned to at least one GO term. Among the DEGs in different accessions under low-P conditions, 2317 of the 4762 DEGs were assigned to different GO terms. Among the candidate DEGs, 1006 of the 2089 DEGs were assigned to at least one GO term.

To deeply investigate the functions of DEGs, GO enrichment of each group was analyzed, and the top 30 GO enrichment terms were listed (Additional file 2: Figure S1). The results showed the following: 1) For the DEGs in the different accessions under low-P conditions, many of the top 30 significantly enriched GO terms were in the molecular function category, suggesting these two accessions had significant differences in molecular functions under low-P conditions. 2) Candidate genes were significantly enriched in the molecular function and biological process categories, implying that molecular functions and biological processes play important roles in P starvation tolerance of sorghum. Within the molecular function category, GO terms related to oxidoreductase activity (GO:0016491, GO:0016705, GO:0016684, GO:0051213, GO:0004601, GO:0004497) were significantly enriched.

The candidate genes enriched in GO terms for which the Input frequency/Background frequency ratio was higher than 1 were examined and are listed in Table 3. The results showed that a total of 20 GO terms exhibited a higher Input frequency than Background frequency, suggesting that the expression changes of these genes might affect the functions of these GO terms. Among them, GO terms related to antioxidant activity, transporter activity, nucleic acid binding TF activity, catalytic activity, extracellular region, membrane part and response to stimulus also showed a higher Input frequency than Background frequency in the DEGs in response to low-P stress and the DEGs in different accessions under low-P conditions.

Table 3.

List of the focused significantly enrichedment GO terms

| Namespace | ID | Term | Input frequency/Background frequency | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 13443(L/C) | 12484(L/C) | 12484 L vs 13443 L | candidate genes | |||

| molecular function | GO:0016209 | antioxidant activity | 1.9422 | 2.0953 | 1.8839 | 2.6634 |

| molecular function | GO:0005215 | transporter activity | 1.2064 | 1.3471 | 1.2791 | 1.3071 |

| molecular function | GO:0001071 | nucleic acid binding transcription factor activity | 1.3734 | 1.3157 | 1.2425 | 1.2459 |

| molecular function | GO:0003824 | catalytic activity | 1.1786 | 1.1433 | 1.1391 | 1.2145 |

| cellular component | GO:0005576 | extracellular region | 1.1444 | 1.8283 | 1.7582 | 2.4556 |

| cellular component | GO:0044425 | membrane part | 1.3049 | 1.2736 | 1.0791 | 1.0349 |

| biological process | GO:0050896 | response to stimulus | 1.0837 | 1.1235 | 1.0924 | 1.0360 |

| molecular function | GO:0060089 | molecular transducer activity | 0.8920 | 1.0287 | 1.0935 | 1.2583 |

| molecular function | GO:0030234 | enzyme regulator activity | 0.8054 | 1.0453 | 0.8389 | 1.1622 |

| molecular function | GO:0009055 | electron carrier activity | 1.0321 | 0.9704 | 0.9665 | 1.1497 |

| molecular function | GO:0098772 | molecular function regulator | 0.8312 | 1.0748 | 0.8044 | 1.1363 |

| molecular function | GO:0045735 | nutrient reservoir activity | 0.4629 | 1.7021 | 0.9457 | 1.1098 |

| cellular component | GO:0016020 | membrane | 1.1236 | 1.1582 | 0.9954 | 1.0698 |

| biological process | GO:0001906 | cell killing | – | – | – | 2.9594 |

| biological process | GO:0048511 | rhythmic process | 0.5311 | 1.3314 | 1.6275 | 2.4213 |

| biological process | GO:0040011 | locomotion | 1.1418 | 1.0370 | – | 1.6646 |

| biological process | GO:0051704 | multi-organism process | 0.9849 | 1.0975 | 0.9937 | 1.5259 |

| biological process | GO:0044699 | single-organism process | 1.0054 | 1.0551 | 0.9164 | 1.1612 |

| biological process | GO:0008152 | metabolic process | 0.9470 | 0.9064 | 0.8909 | 1.1021 |

| biological process | GO:0002376 | immune system process | 0.7807 | 1.1255 | 1.1963 | 1.0871 |

“—” means GO term not significantly enreached

Significant enrichment pathways

Genes usually play roles in certain biological processes by interacting with each other. Therefore, pathway analyses are helpful for further understanding the biological functions of genes. Pathway enrichment analysis of each group’s DEGs based on the KEGG database was performed, and the significantly enriched pathways are listed in Table 4. Notably, almost all of the significantly enriched pathways were involved in metabolism.

Table 4.

List of significantly enrichedment pathways

| Term | Pathways Identifiers | P-Value | First class | Second class | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 13443 (L/C) | 12484 (L/C) | 12484 L vs 13443 L | candidate DEGs | ||||

| Phenylpropanoid biosynthesis | map00940 | 4.2902E-06 | 6.0067E-06 | 0.0001 | 6.3352E-09 | Metabolism | Biosynthesis of other secondary metabolites |

| Phenylalanine metabolism | map00360 | 2.5179E-05 | 4.1713E-06 | 0.0010 | 1.2791E-06 | Metabolism | Amino acid metabolism |

| Biosynthesis of secondary metabolites | map01110 | 0.0002 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 2.2959E-06 | Metabolism | Global and overview maps |

| Metabolic pathways | map01100 | – | 0.0023 | 0.0084 | 0.0068 | Metabolism | Global and overview maps |

| Flavone and flavonol biosynthesis | map00944 | 0.0278 | – | 0.0244 | 0.0116 | Metabolism | Biosynthesis of other secondary metabolites |

| Carotenoid biosynthesis | map00906 | – | 0.0038 | 0.0188 | 0.0189 | Metabolism | Metabolism of terpenoids and polyketides |

| Starch and sucrose metabolism | map00500 | – | 0.0010 | – | 0.0217 | Metabolism | Carbohydrate metabolism |

| Monoterpenoid biosynthesis | map00902 | – | 0.0218 | – | 0.0223 | Metabolism | Metabolism of terpenoids and polyketides |

| Galactose metabolism | map00052 | – | 0.0168 | 0.0056 | 0.0368 | Metabolism | Carbohydrate metabolism |

| Flavonoid biosynthesis | map00941 | – | 0.0398 | – | 0.0403 | Metabolism | Biosynthesis of other secondary metabolites |

| Nitrogen metabolism | map00910 | – | 0.0359 | – | 0.0483 | Metabolism | Energy metabolism |

| Glutathione metabolism | map00480 | – | 0.0016 | – | – | Metabolism | Metabolism of other amino acids |

| Amino sugar and nucleotide sugar metabolism | map00520 | – | 0.0045 | – | – | Metabolism | Carbohydrate metabolism |

| Plant hormone signal transduction | map04075 | – | 0.0082 | – | – | Environmental Information Processing | Signal transduction |

| alpha-Linolenic acid metabolism | map00592 | – | 0.0250 | – | – | Metabolism | Lipid metabolism |

| Zeatin biosynthesis | map00908 | – | 0.0302 | – | – | Metabolism | Metabolism of terpenoids and polyketides |

| Glycerolipid metabolism | map00561 | 0.0004 | – | – | – | Metabolism | Lipid metabolism |

| Cutin, suberine and wax biosynthesis | map00073 | 0.0066 | – | – | – | Metabolism | Lipid metabolism |

| Phenylalanine, tyrosine and tryptophan biosynthesis | map00400 | 0.0213 | – | – | – | Metabolism | Amino acid metabolism |

| Taurine and hypotaurine metabolism | map00430 | 0.0277 | – | – | – | Metabolism | Metabolism of other amino acids |

| Degradation of aromatic compounds | map01220 | 0.0278 | – | – | – | Metabolism | Global and overview maps |

| Stilbenoid, diarylheptanoid and gingerol biosynthesis | map00945 | 0.0362 | – | – | – | Metabolism | Biosynthesis of other secondary metabolites |

| Glycerophospholipid metabolism | map00564 | 0.0481 | – | – | – | Metabolism | Lipid metabolism |

| Cysteine and methionine metabolism | map00270 | – | – | 0.0187 | – | Metabolism | Amino acid metabolism |

| Thiamine metabolism | map00730 | – | – | 0.0260 | – | Metabolism | Metabolism of cofactors and vitamins |

“—” means that the P-Value is greater than 0.05

For those pathways, 1) 3 pathways (phenylpropanoid biosynthesis, phenylalanine metabolism, and biosynthesis of secondary metabolites) were significantly enriched by low-P treatment in both accessions; 2) pathways specifically enriched in accession 12484 by low-P stress include sugar metabolism (starch and sucrose, galactose, amino sugar and nucleotide sugar) and carotenoid biosynthesis, while those in accession 13443 include amino acid metabolism (phenylalanine, tyrosine, tryptophan, taurine and hypotaurine) and lipid metabolism (glycerolipid and glycerophospholipid); 3) for the candidate DEGs, 11 pathways were significantly enriched, and most of them were only significantly enriched in accession 12484 in response to low-P stress.

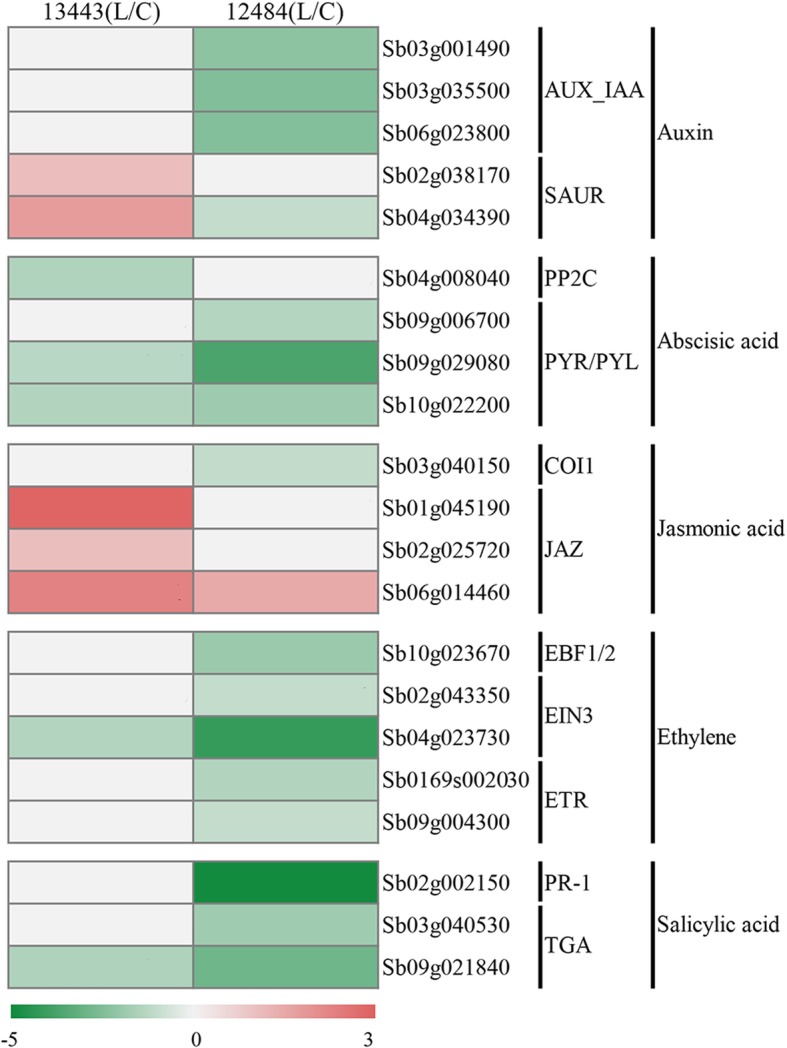

Candidate genes involved in plant hormone signal transduction

Almost all of the significantly enriched pathways were involved in metabolism. Interestingly, only one term (plant hormone signal transduction) involved in signal transduction was from the class of environmental information processing (Table 4). Recent evidence has proven that hormones participate in the control of plants in response to P starvation [48, 49]. Therefore, the DEGs related to plant hormone signal transduction were chosen for further analysis.

A total of 21 candidate DEGs were found to be associated with plant hormone (including auxin (AUX), abscisic acid (ABA), jasmonic acid (JA), ethylene (ET), and salicylic acid (SA)) signal transduction (Fig. 6). Among them, five DEGs were AUX signaling pathway-related genes, including two small auxin upregulated RNA (SAUR) genes and three Aux/IAA genes. Moreover, four candidate genes were ABA signaling pathway-related genes, including one protein phosphatase 2C (PP2C) and three PYR/PYL genes. Furthermore, four candidate genes were involved in the JA signaling pathway, including three jasmonatezim-domain (JAZ) genes and one coronatine insensitive 1 (COI1) gene. In addition, there were seven candidate genes related to the ET signaling pathway, including one EBF1/2 gene, two EIN3 genes, two Ethylene-insensitive-3-like (EIL) genes and two ETR genes, and three candidate genes related to the SA signaling pathway, including one PR-1 gene and two TGA genes.

Fig. 6.

Heatmap of the candidate genes involved in plant hormone signal transduction. The log2 fold change of the candidate genes involved in plant hormone signal transduction under low-P conditions compared with that under sufficient-P conditions in each section is represented by a color scale consisting of red (upregulated), white (not regulated) and green (downregulated)

Transcriptional factors (TFs) identified from candidate genes

A total of 127 nonredundant TFs were identified from the candidate DEGs using the plant TF database PlantTFDB version 4.0 (http://planttfdb.cbi.pku.edu.cn/). In general, 109 were responding to low P in accession 12848, while 50 were responding to low P in accession 13443. Among them, bHLH, WRKY and MYB were the top three most abundant TFs, numbering 17, 13, and 12, respectively (Table 5).

Table 5.

List of genes belonging to TFs

| TF-Family | Gene | Expression (in response to low P) | TF-Family | Gene | Expression (in response to low P) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 13443 | 12484 | 13443 | 12484 | ||||

| AP2 | Sb01g003400 | up | up | HD-ZIP | Sb01g022420 | – | up |

| B3 | Sb09g004870 | – | up | HD-ZIP | Sb06g025750 | – | up |

| bHLH | Sb03g008290 | – | up | HD-ZIP | Sb04g023410 | – | down |

| bHLH | Sb10g005650 | – | up | HD-ZIP | Sb06g024000 | – | down |

| bHLH | Sb02g027210 | – | up | HSF | Sb01g021490 | up | up |

| bHLH | Sb01g045710 | – | up | HSF | Sb01g008380 | up | – |

| bHLH | Sb01g043570 | – | up | HSF | Sb03g033750 | – | down |

| bHLH | Sb03g036100 | up | up | LSD | Sb07g004050 | – | up |

| bHLH | Sb07g004190 | up | up | LBD | Sb09g030780 | up | – |

| bHLH | Sb2250s002010 | up | – | LBD | Sb01g014800 | – | down |

| bHLH | Sb09g006220 | up | – | MIKC_MADS | Sb07g001250 | – | up |

| bHLH | Sb04g017390 | down | down | MIKC_MADS | Sb06g017660 | – | up |

| bHLH | Sb04g027280 | – | down | MYB | Sb03g004600 | – | up |

| bHLH | Sb01g041960 | – | down | MYB | Sb03g032260 | – | up |

| bHLH | Sb03g042860 | – | down | MYB | Sb02g040480 | – | up |

| bHLH | Sb05g023730 | – | down | MYB | Sb08g016620 | up | – |

| bHLH | Sb06g028750 | – | down | MYB | Sb02g030900 | up | – |

| bHLH | Sb06g020810 | – | down | MYB | Sb08g018840 | down | up |

| bHLH | Sb03g005250 | – | down | MYB | Sb03g003120 | down | down |

| bZIP | Sb08g020600 | – | up | MYB | Sb09g001590 | – | down |

| bZIP | Sb04g008840 | – | up | MYB | Sb03g012310 | – | down |

| bZIP | Sb04g007060 | – | up | MYB | Sb02g024260 | – | down |

| bZIP | Sb07g025490 | – | up | MYB | Sb02g043420 | – | down |

| bZIP | Sb01g037520 | up | up | MYB | Sb09g002680 | – | down |

| bZIP | Sb04g000300 | up | – | MYB_related | Sb09g029560 | – | up |

| bZIP | Sb09g021840 | down | down | MYB_related | Sb03g006440 | – | down |

| bZIP | Sb09g024290 | – | down | MYB_related | Sb04g031590 | – | down |

| bZIP | Sb03g040530 | – | down | MYB_related | Sb03g011280 | – | down |

| bZIP | Sb02g027410 | – | down | NAC | Sb04g036340 | – | up |

| C2H2 | Sb04g021440 | – | up | NAC | Sb03g035820 | up | – |

| C2H2 | Sb01g031900 | up | up | NAC | Sb02g028870 | up | down |

| C2H2 | Sb01g031920 | up | up | NAC | Sb04g023990 | – | down |

| C2H2 | Sb03g025790 | – | down | NAC | Sb01g048130 | – | down |

| C2H2 | Sb07g028010 | – | down | NAC | Sb01g006410 | – | down |

| C2H2 | Sb02g028220 | – | down | NAC | Sb07g005610 | – | down |

| C2H2 | Sb01g043960 | – | down | NAC | Sb06g017190 | – | down |

| C2H2 | Sb10g004570 | – | down | NAC | Sb08g022560 | – | down |

| C3H | Sb03g003110 | down | down | NAC | Sb02g043210 | down | down |

| C3H | Sb09g006050 | down | – | NF-YB | Sb02g038870 | down | down |

| CO-like | Sb04g029480 | – | down | NF-YC | Sb06g033380 | up | – |

| CO-like | Sb06g021480 | down | down | Nin-like | Sb04g002940 | – | down |

| EIL | Sb02g043350 | – | down | RAV | Sb03g031860 | – | down |

| EIL | Sb04g023730 | down | down | TALE | Sb04g008030 | – | down |

| ERF | Sb01g040280 | – | up | TALE | Sb05g003750 | – | down |

| ERF | Sb06g025890 | up | up | TALE | Sb02g002200 | – | down |

| ERF | Sb06g025900 | up | up | TCP | Sb06g023130 | up | – |

| ERF | Sb06g024540 | up | up | TCP | Sb10g008030 | down | down |

| ERF | Sb07g023803 | up | – | TCP | Sb02g030260 | – | down |

| ERF | Sb03g012890 | up | down | Trihelix | Sb03g013050 | up | – |

| ERF | Sb10g004580 | down | down | WRKY | Sb03g038170 | – | up |

| ERF | Sb03g042060 | – | down | WRKY | Sb10g025600 | up | up |

| ERF | Sb09g020690 | – | down | WRKY | Sb10g025590 | up | up |

| ERF | Sb01g044410 | – | down | WRKY | Sb09g029850 | up | – |

| FAR1 | Sb01g040730 | – | down | WRKY | Sb05g001170 | up | – |

| G2-like | Sb07g021290 | up | – | WRKY | Sb03g028530 | up | down |

| G2-like | Sb02g001600 | up | – | WRKY | Sb03g029920 | up | down |

| G2-like | Sb06g031970 | down | down | WRKY | Sb03g047350 | down | – |

| G2-like | Sb01g036680 | – | down | WRKY | Sb02g043030 | down | down |

| G2-like | Sb04g003140 | – | down | WRKY | Sb04g009800 | – | down |

| GeBP | Sb03g009480 | down | down | WRKY | Sb08g005080 | – | down |

| GeBP | Sb03g005180 | down | down | WRKY | Sb02g024760 | – | down |

| GRAS | Sb02g034550 | – | down | WRKY | Sb01g036180 | – | down |

| GRAS | Sb06g017860 | – | down | ZF-HD | Sb05g001690 | up | down |

| GRF | Sb04g034800 | – | up | ||||

Interestingly, among the TFs, two WRKY (Sb03g028530 and Sb03g029920), one NAC (Sb02g028870), one ERF (Sb03g012890) and one ZF-HD (Sb05g00169) were downregulated in accession 12848 but were upregulated in accession 13443 by low-P stress, while the opposite was observed for one MYB (Sb08g018840).

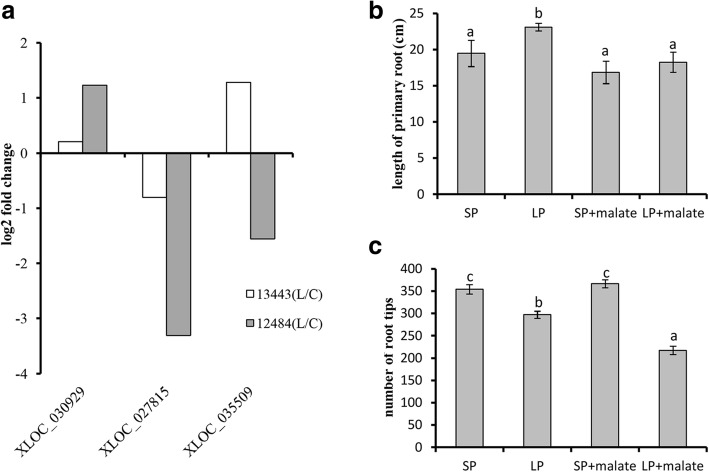

Root development of sorghum in response to low P with and without malate

Under low-P stress, plants often secrete organic acid in roots. Among the candidate genes, three were involved in malate metabolism, encoding malate dehydrogenase (Sb07g023910), malate synthase (Sb06g020720) and malic enzyme (Sb09g005810) respectively. And all of them showed different expression patterns in low-P-tolerant and -sensitive accessions in response to low-P stress (Fig. 7a). Our results showed that the primary root length and the numbers of root tips were significantly correlative with P starvation tolerance in sorghum. Therefore, we wondered whether malate affects the primary root length and the number of root tips in sorghum. The results showed that under sufficient-P conditions, application of malate did not affect the length of the primary root and the number of tips significantly (Fig. 7b and c). Under low-P conditions, however, it significantly reduced the length of the primary root and the number of root tips (Fig. 7b and c).

Fig. 7.

Effect of malate application on root development. a Expression profile of the malate metabolism-related genes XLOC_030929 (Sb07g023910), XLOC_027815 (Sb06g020720) and XLOC_035509 (Sb09g005810). b Effect of applying malate on the length of the primary root. c Effect of applying malate on the number of root tips. The different lowercase letters denote significant differences among different treatments. Bars represent the standard error of the mean (n = 3)

Discussion

Different sorghum accessions displayed dramatic variability in their tolerance of P starvation, which is associated with shoot internal P content, indicating that P uptake contributes to P starvation tolerance variability. Root morphology is a key trait for optimizing the efficiency of P acquisition in plants [50, 51]. Our results showed that P starvation tolerance in sorghum was significantly correlated with root morphology, implying roots played important roles in P starvation tolerance in sorghum. Therefore, the transcription profiles in sorghum roots were studied. In our study, the majority of the accessions displayed consistent results between experiments carried out in 2 years. However, several accessions, such as 357 and 2349, showed significant differences between the 2 years. This led to the ranking of the tolerance of different accessions to low P. We chose two accessions, 12484 and 13443, as low-P-tolerant and -sensitive varieties, respectively, because these two accessions were constantly at the two extremes of the tolerance ranking. The ranking variations of tolerance to low P were concurrent with those of internal P content. The variations in internal P content of the same accession in different years indicate that there are other environmental factors beyond genotype contributing to P acquisition.

The two accessions showed great differences in root morphology under low-P stress

It was suggested that most plant responses to P deficiency included the remodeling of root morphology, which involves suppressing primary root growth and enhancing the production of root hairs and lateral roots [52–54]. In our study, both of the selected materials showed enhanced primary root elongation under low-P stress (Fig. 3), while more lateral roots were promoted in tolerant accessions than sensitive accessions, implying that the genes regulating the elongation of the primary root and the enhancement of lateral roots play important roles in the response to low-P stress. It is well documented that root morphology is regulated by many signaling pathways. For instance, the AUX signal-related genes OsARF12 and OsTOP1 were involved in primary root development in rice [55, 56]. The SA signal-related gene OsAIM1 and GA signal-related gene OsSHB were also involved in primary root development [57, 58], while the MYB type TF OsMYB1 was involved in lateral root development [59]. Root hairs play key roles in P uptake in plants [60]. In Arabidopsis, some TFs, including MYB types such as MEMBRANE ANCHORED MYB (maMYB) [61], bHLH types such as RHD SIX-LIKE 1 (RSL1) [62], RHD SIX-LIKE 3 (RSL3) [63], Lotus japonicus ROOT HAIR LESS-LIKE 2 (LRL2) [64] and HD-ZIP types such as HOMEODOMAIN GLABROUS 11 (HDG11) [65] were found to be involved in root hair growth. Moreover, P starvation-induced genes involved in root hair development have been identified. For instance, OsAUX1 encoding an auxin influx transporter could promote root hair elongation under low-P stress in rice [66]. In Arabidopsis, the ET signaling gene EIN3 and its closest homolog EIL1 were demonstrated to be involved in P starvation-induced root hair development [67]. In our study, we found two EIL proteins, Sb02g043350 and Sb04g023730, and three bHLH-type TFs, Sb03g008290, Sb01g043570 and Sb10g005650, similar to RSL1, RSL3 and LRL2, respectively, that were candidate genes, suggesting that these genes might regulate P tolerance by mediating root hair growth in sorghum. Thus, our data help reveal the related genes or mechanism controlling root morphology in sorghum under low-P stress.

More active responses to P starvation in the low-P-tolerant accession

Under different P treatments, the number of DEGs in the low-P-tolerant accession 12484 was nearly two-fold higher than that in the low-P-sensitive accession 13443, implying that the low-P-tolerant accession responded to low P more positively and dramatically. Moreover, the numbers of unique DEGs identified in accession 13443 or accession 12484 were greater than the number of overlapping DEGs, indicating that there are differences between the two accessions in response to low P. Similarly, many more DEGs in response to low P were found in low-P-tolerant accessions than in low-P-sensitive accessions in soybean [68]. In maize, however, the number of DEGs in low-P-tolerant materials was lower than that in low-P-sensitive materials under low-P stress [69]. Thus, it is not valid to evaluate whether an accession is tolerant of low P or not solely based on the number of DEGs under low-P conditions.

Complex mechanism of P starvation tolerance in sorghum

Among the candidate genes, the significantly enriched GO terms referred to molecular function, cellular component and biological process, implying that achieving P starvation tolerance required many processes. The top 30 significantly enriched GO terms of DEGs under low-P conditions suggested that the two accessions had differences in molecular functions under low-P conditions. Further analysis showed that the input frequency of antioxidant activity, catalytic activity, transporter activity and nucleic acid binding TF activity, belonging to molecular function, were higher than the background frequency, suggesting the key roles of genes belonging to these terms in low-P tolerance in sorghum.

Candidate genes related to P starvation tolerance were enriched in many pathways. Notably, genes participating in phenylpropanoid biosynthesis, secondary metabolism, starch and sucrose metabolism and nitrogen metabolism also actively responded to low-P stress in maize [39], Arabidopsis [70] and rice [71]. Phenylpropanoid biosynthesis, phenylalanine metabolism, and biosynthesis of secondary metabolites were the top 3 enriched pathways, suggesting these pathways responded actively when sorghum suffered from low-P stress. Phenylpropanoids contribute to all aspects of plant responses toward biotic and abiotic stimuli, and phenylpropanoids are not only indicators of plant stress responses under varied light, mineral treatment, and pest stresses but are also key mediators in plants [72, 73]. The same results were also reported in soybean under low-P stress [53]. Moreover, the candidate genes were significantly enriched in flavone and flavonol biosynthesis, carotenoid biosynthesis and flavonoid biosynthesis pathways. Flavonol is one of the main classes of phenylpropanoid pathway derivatives [74–76]. Flavonoids and carotenoids are widely known for their influence on the colors of plant tissues, which further contributes to plant fitness and food quality. The flavonoid pathway has been suggested to play important roles in protecting plants from oxidative stresses induced by drought [77], temperature [78], and nitrogen, P, or carbon nutrition [79, 80]. Carotenoids are crucial for driving biological processes in plants, including the assembly of photosystems and light harvesting antenna complexes for photosynthesis and the regulation of growth and development [81, 82]. A kind of carotenoid derivative, strigolactone, plays roles in root responses to low-P stress in Arabidopsis [83] and tomato [84].

In general, the results of our study show that many GO terms and pathways are enriched in sorghum suffering from low-P stress, implying that a complex mechanism of P starvation tolerance exists in sorghum.

Malate play key roles in root development in sorghum under low-P stress

Notably, we found that applying malate reduced the length of the primary root and the number of root tips under P stress, implying malate was involved in P starvation tolerance in sorghum by affecting root development. Recently, reactive oxygen species (ROS) were also found to trigger callose deposition, which further adjusts apical meristem activity in roots under low-P stress [85, 86]. For the candidate DEGs, many GO terms related to oxidoreductase activity were found, which suggested that ROS generation and elimination were active in sorghum suffering from low-P stress. In our study, applying malate only affected root development under low-P conditions, suggesting that low-P stress might generate some factors that perhaps promote malate to affect root development. Moreover, in Arabidopsis, malate was found to inhibit root growth by adjusting the accumulation of Fe in plants under low-P stress, which is dependent on ALMT [43]. It has also been reported that Fe overloading modifies root growth in P-deprived plants [87–89]. Additionally, ROS is produced during low-P stress with the accumulation of Fe3+ [85, 90]. Our GO enrichment results showed that many P candidate genes were involved in Fe binding. From these results, we speculate that malate plays key roles in root development in sorghum under low-P stress, perhaps through Fe and ROS.

Plant hormone signal transduction and TFs related to P starvation tolerance in sorghum

Plant hormones are involved in many biological processes in enhanced resistance to environmental stresses, diseases and pathogen infections [91]. In the present study, many DEGs were related to plant hormone (including AUX, ABA, JA, ET, and SA) signal transduction. AUX has been suggested to stimulate root growth and lateral root proliferation upon P starvation [7]. Notably, the 3 AUX/IAA genes (Sb03g001490, Sb03g035500, Sb06g023800) related to AUX signal transduction were downregulated in low-P-tolerant material by low-P stress but were not significantly changed in low-P-sensitive material. In Arabidopsis, the phloem-mobile transcript of IAA could target the root tip and then regulate root morphology [92]. We speculate that the 3 AUX/IAA genes play similar roles in root morphology regulation, but the specific functions of these genes under low-P stress in sorghum should be further studied.

ET was also involved in low-P stress. P starvation could alter ET biosynthesis in plants, while ET could regulate root growth under low-P stress [93–95]. In our study, several ET signal-related genes were considered to be related to low-P tolerance in sorghum. In Arabidopsis, the eto1 mutant overproducing ET exhibited reduced primary root growth and increased production of root hairs [96]. Whether a similar regulatory mechanism also exists in sorghum should be further investigated.

Although the exact roles of ABA and SA in plants suffering from low P are not clear, these hormones were found to respond to low P. In Arabidopsis, ABA biosynthesis mutants exposed to low-P stress displayed reduced expression of P starvation-responsive genes and accumulation of anthocyanins [97]. Some studies have suggested that SA is involved in the response of plants to low P by controlling their redox status [98, 99]. In the present study, two candidate bZIP genes (Sb03g040530, Sb09g021840) encoding TGA were involved in the SA signaling pathway. In Arabidopsis, type-II TGA TFs were demonstrated to be key activators of JA/ET-induced immune reactions [100]. JA accumulation occurs when plants are exposed to a low-P environment, further enhancing herbivory resistance and reducing shoot growth [101]. However, the role that SA plays in low-P stress is unclear. Thus, we speculate that SA can regulate P starvation through crosstalk with the JA/ET signaling pathway or other pathways, but the underlying mechanism should be further studied.

TFs were suggested to play a key role in the regulation of gene expression at the transcriptional level by binding to DNA regulatory elements [102]. Substantial evidences have proved that TFs are also involved in phosphate homeostasis [103–106]. In our study, besides ET- and SA-related TFs, many other TFs including bHLHs, WRKYs, MYBs, bZIPs, NACs and C2H2 zinc finger proteins, were identified. In rice, OsMYB2P-1 is involved in the regulation of P starvation responses and root architecture by suppressing or activating downstream genes [107]. Overexpression of OsMYB4P could activate the expression of several Pht genes and increase phosphate acquisition [108]. WRKY74 modulates the tolerance to phosphate starvation in rice [109]. In wheat, TaZAT8, a C2H2-ZFP-type TF gene, plays critical roles in mediating wheat tolerance to P deprivation by regulating P acquisition, ROS homeostasis and root system establishment [110]. Our results indicate that TFs may also play important roles in sorghum tolerance to low P, but their functions should be further studied.

Conclusions

Transcriptome analysis showed that a P starvation-tolerant accession exhibited more active responses to low-P stress. A total of 2089 genes were identified and enriched in many GO terms and pathways, suggesting that P starvation tolerance of sorghum is a complex mechanism. Malate significantly reduced the length of the primary root and numbers of root tips in sorghum suffering from low-P stress. Plant hormone (including AUX, ET, JA, SA and ABA) signal transduction-related genes and many TFs were found to be involved in low-P tolerance in sorghum. The findings reported herein increase our understanding of the molecular characteristics of sorghum tolerant of low-P stress. The identified accessions will be useful for inbreeding new sorghum varieties with a high P starvation tolerance.

Additional files

Table S1. Gene-specific primers used in gene expression analysis by qRT-PCR. (XLSX 13 kb)

Figure S1. GO annotations and GO enrichment of DEGs. a and e DEGs in accession 12484 in response to low-P stress. b and f DEGs in accession 13443 in response to low-P stress. c and g DEGs in different accessions under low-P conditions. d and h Active DEGs. DEGs in accession 12484 in response to low-P stress. (PDF 1359 kb)

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Prof. Ping Lu from the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences for providing sorghum accessions from the China National Genebank.

Abbreviations

- ABA

Abscisic acid

- AUX

Auxin

- COI1

Coronatine insensitive 1

- DEG

Differentially expressed gene

- ET

Ethylene

- FDR

False discovery rate

- FPKM

Fragments per kilobase of transcript per million fragments mapped

- GO

Gene ontology

- JA

Jasmonic acid

- JAZ

Jasmonate ZIM-domain

- KEGG

Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes

- MYB62

MYB domain protein 62

- P

Phosphorus

- PHR1

Phosphate starvation response1

- PHT

Phosphate transporter

- Pi

Inorganic orthophosphate

- PP2C

Protein phosphatase 2C

- PSTOL1

Phosphorus starvation tolerance 1

- qRT-PCR

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction

- R/S ratio

Root to shoot weight ratio

- RADR

Relative average diameter of root

- RDWR

Relative dry weight of root

- RDWS

Relative dry weight of shoot

- RLR

Relative length of roots

- RNA-Seq

mRNA sequencing

- RNRT

Relative number of root tips

- ROS

Reactive oxygen species

- RPCS

Relative P content of shoot

- RSAR

Relative surface area of root

- RVR

Relative volume of root

- SA

Salicylic acid

- SAUR

Small auxin upregulated RNA

- TF

Transcriptional factor

Authors’ contributions

YS, YC, QZ and JZ designed and performed the experiments. JZ, BB and WC performed the pot experiments. JZ performed the hydroponic experiments and collected samples. ZJ and FJ performed the qRT-PCR and malate application experiments. YC, YS and JZ analyzed the data. JZ wrote the draft manuscript. YC, YS and QZ critically revised the draft manuscript, and all authors approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31372359).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article and its additional files.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Jinglong Zhang, Email: 2014220004@njau.edu.cn.

Fangfang Jiang, Email: 2016820018@njau.edu.cn.

Yixin Shen, Email: yxshen@njau.edu.cn.

Qiuwen Zhan, Email: qwzhan@163.com.

Binqiang Bai, Email: 2015220006@njau.edu.cn.

Wei Chen, Email: 2017220002@njau.edu.cn.

Yingjun Chi, Email: yingjunchi@njau.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Marschner H, Rimmington G. Mineral nutrition of higher plants. Plant Cell Environ. 1988;11:147–148. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Raghothama KG, Karthikeyan AS. Phosphate acquisition. Plant Soil. 2005;274:37–49. doi: 10.1007/s11104-004-2005-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Péret B, Clément M, Nussaume L, Desnos T. Root developmental adaptation to phosphate starvation: better safe than sorry. Trends Plant Sci. 2011;16:442–450. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2011.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holford ICR. Soil phosphorus: its measurement, and its uptake by plants. Soil Res. 1997;35:227–240. doi: 10.1071/S96047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hinsinger P. Bioavailability of soil inorganic P in the rhizosphere as affected by root-induced chemical changes: a review. Plant Soil. 2001;237:173–195. doi: 10.1023/A:1013351617532. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.López-Arredondo DL, Leyva-González MA, González-Morales SI, López-Bucio J, Herrera-Estrella L. Phosphate nutrition: improving low-phosphate tolerance in crops. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2014;65:95–123. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-050213-035949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.López-Bucio J, Hernández-Abreu E, Sánchez-Calderón L, Nieto-Jacobo MF, Simpson J, Herrera-Estrella L. Phosphate availability alters architecture and causes changes in hormone sensitivity in the Arabidopsis root system. Plant Physiol. 2002;129:244–256. doi: 10.1104/pp.010934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bucher M. Functional biology of plant phosphate uptake at root and mycorrhiza interfaces. New Phytol. 2007;173:11–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2006.01935.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rausch C, Bucher M. Molecular mechanisms of phosphate transport in plants. Planta. 2002;216:23–37. doi: 10.1007/s00425-002-0921-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jain A, Vasconcelos MJ, Raghothama KG, Sahi SV. Molecular mechanisms of plant adaptation to phosphate deficiency. Plant Breed Rev. 2007;29:359. doi: 10.1002/9780470168035.ch7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang L, Li Z, Qian W, et al. The Arabidopsis purple acid phosphatase AtPAP10 is predominantly associated with the root surface and plays an important role in plant tolerance to phosphate limitation. Plant Physiol. 2011;157:1283–1299. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.183723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Muchhal US, Pardo JM, Raghothama KG. Phosphate transporters from the higher plant Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1996;93:10519–10523. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.19.10519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mudge SR, Rae AL, Diatloff E, Smith FW. Expression analysis suggests novel roles for members of the Pht1 family of phosphate transporters in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2002;31:341–353. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2002.01356.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shin H, Shin HS, Dewbre GR, Harrison MJ. Phosphate transport in Arabidopsis: Pht1;1 and Pht1;4 play a major role in phosphate acquisition from both low- and high-phosphate environments. Plant J. 2004;39:629–642. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02161.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jia H, Ren H, Gu M, et al. The phosphate transporter gene OsPht1;8 is involved in phosphate homeostasis in rice. Plant Physiol. 2011;156:1164–1175. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.175240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rubio V, Linhares F, Solano R, et al. A conserved MYB transcription factor involved in phosphate starvation signaling both in vascular plants and in unicellular algae. Genes Dev. 2001;15:2122–2133. doi: 10.1101/gad.204401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Devaiah BN, Karthikeyan AS, Raghothama KG. WRKY75 transcription factor is a modulator of phosphate acquisition and root development in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2007;143:1789–1801. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.093971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang H, Xu Q, Kong YH, et al. Arabidopsis WRKY45 transcription factor activates PHOSPHATE TRANSPORTER1;1 expression in response to phosphate starvation. Plant Physiol. 2014;164:2020–2029. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.235077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Devaiah BN, Madhuvanthi R, Karthikeyan AS, Raghothama KG. Phosphate starvation responses and gibberellic acid biosynthesis are regulated by the MYB62 transcription factor in Arabidopsis. Mol Plant. 2009;2:43–58. doi: 10.1093/mp/ssn081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hamburger D, Rezzonico E, Petétot JMDC, Somerville C, Poirier Y. Identification and characterization of the Arabidopsis PHO1 gene involved in phosphate loading to the xylem. Plant Cell. 2002;14:889–902. doi: 10.1105/tpc.000745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang Y, Ribot C, Rezzonico E, Poirier Y. Structure and expression profile of the Arabidopsis PHO1 gene family indicates a broad role in inorganic phosphate homeostasis. Plant Physiol. 2004;135:400–411. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.037945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bari R, Pant BD, Stitt M, Scheible W. PHO2, MicroRNA399, and PHR1 define a phosphate-signaling pathway in plants. Plant Physiol. 2006;141:988–999. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.079707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen YF, Li LQ, Xu Q, Kong YH, Wang H, Wu WH. The WRKY6 transcription factor modulates PHOSPHATE1 expression in response to low pi stress in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2009;21:3554–3566. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.064980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Su T, Xu Q, Zhang FC, et al. WRKY42 modulates phosphate homeostasis through regulating phosphate translocation and acquisition in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2015;167:1579–1591. doi: 10.1104/pp.114.253799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kant S, Peng M, Rothstein SJ. Genetic regulation by NLA and microRNA827 for maintaining nitrate-dependent phosphate homeostasis in Arabidopsis. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002021. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hackenberg M, Shi BJ, Gustafson P, Langridge P. Characterization of phosphorus-regulated miR399 and miR827 and their isomirs in barley under phosphorus-sufficient and phosphorus-deficient conditions. BMC Plant Biol. 2013;13:214. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-13-214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu TY, Lin WY, Huang TK, Chiou TJ. MicroRNA-mediated surveillance of phosphate transporters on the move. Trends Plant Sci. 2014;19:647–655. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2014.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Devaiah BN, Nagarajan VK, Raghothama KG. Phosphate homeostasis and root development in Arabidopsis are synchronized by the zinc finger transcription factor ZAT6. Plant Physiol. 2007;145:147–159. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.101691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hufnagel B, de Sousa SM, Assis L, et al. Duplicate and conquer: multiple homologs of PHOSPHORUS-STARVATION TOLERANCE1 enhance phosphorus acquisition and sorghum performance on low-phosphorus soils. Plant Physiol. 2014;166:659–677. doi: 10.1104/pp.114.243949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Otani T, Ae N. Phosphorus (P) uptake mechanisms of crops grown in soils with low P status: I. screening of crops for efficient P uptake. J Soil Sci Plant Nut. 1996;42:155–163. doi: 10.1080/00380768.1996.10414699. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zerbini E, Thomas D. Opportunities for improvement of nutritive value in sorghum and pearl millet residues in South Asia through genetic enhancement. Field Crop Res. 2003;84:3–15. doi: 10.1016/S0378-4290(03)00137-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Qu H, Liu XB, Dong CF, Lu XY, Shen YX. Field performance and nutritive value of sweet sorghum in eastern China. Field Crop Res. 2014;157:84–88. doi: 10.1016/j.fcr.2013.12.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Doumbia MD, Hossner LR, Onken AB. Variable sorghum growth in acid soils of subhumid West Africa. Arid Soil Res Rehabil. 1993;7:335–346. doi: 10.1080/15324989309381366. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Doumbia MD, Hossner LR, Onken AB. Sorghum growth in acid soils of West Africa: variations in soil chemical properties. Arid Land Res Manag. 1998;12:179–190. doi: 10.1080/15324989809381507. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Leiser WL, Rattunde HFW, Weltzien E, et al. Two in one sweep: aluminum tolerance and grain yield in P-limited soils are associated to the same genomic region in west African Sorghum. BMC Plant Biol. 2014;14:206. doi: 10.1186/s12870-014-0206-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schachtman DP, Reid RJ, Ayling SM. Phosphorus uptake by plants: from soil to cell. Plant Physiol. 1998;116:447–453. doi: 10.1104/pp.116.2.447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Secco D, Jabnoune M, Walker H, et al. Spatio-temporal transcript profiling of rice roots and shoots in response to phosphate starvation and recovery. Plant Cell. 2013;25:4285–4304. doi: 10.1105/tpc.113.117325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aziz T, Finnegan PM, Lambers H, Jost R. Organ-specific phosphorus-allocation patterns and transcript profiles linked to phosphorus efficiency in two contrasting wheat genotypes. Plant Cell Environ. 2014;37:943–960. doi: 10.1111/pce.12210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Calderon-Vazquez C, Ibarra-Laclette E, Caballero-Perez J, Herrera-Estrella L. Transcript profiling of Zea mays roots reveals gene responses to phosphate deficiency at the plant- and species-specific levels. J Exp Bot. 2008;59:2479–2497. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ern115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Trapnell C, Williams BA, Pertea G, et al. Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28:511–515. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Trapnell C, Roberts A, Goff L, et al. Differential gene and transcript expression analysis of RNA-seq experiments with TopHat and cufflinks. Nat Protoc. 2012;7:562–578. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Trapnell C, Hendrickson DG, Sauvageau M, Goff L, Rinn JL, Pachter L. Differential analysis of gene regulation at transcript resolution with RNA-seq. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:46–53. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mora-Macías J, Ojeda-Rivera JO, Gutiérrez-Alanís D, et al. Malate-dependent Fe accumulation is a critical checkpoint in the root developmental response to low phosphate. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2017;114:E3563. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1701952114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mollier A, Pellerin S. Maize root system growth and development as influenced by phosphorus deficiency. J Exp Bot. 1999;50:487–497. doi: 10.1093/jxb/50.333.487. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hermans C, Hammond JP, White PJ, Verbruggen N. How do plants respond to nutrient shortage by biomass allocation? Trends Plant Sci. 2006;11(12):610–617. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2006.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Magalhaes JV, Piñeros MA, Maciel LS, Kochian LV. Emerging pleiotropic mechanisms underlying aluminum resistance and phosphorus acquisition on acidic soils. Front Plant Sci. 2018;9:1420. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.01420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lynch J, Läuchli A, Epstein E. Vegetative growth of the common bean in response to phosphorus nutrition. Crop Sci. 1991;31:380–387. doi: 10.2135/cropsci1991.0011183X003100020031x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rubio V, Bustos R, Irigoyen ML, Cardona-Lopez X, Rojas-Triana M, Paz-Ares J. Plant hormones and nutrient signaling. Plant Mol Biol. 2009;69:361–373. doi: 10.1007/s11103-008-9380-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rouached H, Arpat AB, Poirier Y. Regulation of phosphate starvation responses in plants: signaling players and cross-talks. Mol Plant. 2010;3:288–299. doi: 10.1093/mp/ssp120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lynch J. Root architecture and plant productivity. Plant Physiol. 1995;109:7–13. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.1.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Manske GGB, Ortiz-Monasterio JI, Van Ginkel M, et al. Traits associated with improved P-uptake efficiency in CIMMYT's semidwarf spring bread wheat grown on an acid Andisol in Mexico. Plant Soil. 2000;221:189–204. doi: 10.1023/A:1004727201568. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vance CP, Uhde-Stone C, Allan DL. Phosphorus acquisition and use: critical adaptations by plants for securing a nonrenewable resource. New Phytol. 2003;157(3):423–447. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-8137.2003.00695.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yuan H, Liu D. Signaling components involved in plant responses to phosphate starvation. J Integr Plant Biol. 2008;50(7):849–859. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2008.00709.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.López-Bucio J, Cruz-Ramırez A, Herrera-Estrella L. The role of nutrient availability in regulating root architecture. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2003;6(3):280–287. doi: 10.1016/S1369-5266(03)00035-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Qi YH, Wang SK, Shen CJ, et al. OsARF12, a transcription activator on auxin response gene, regulates root elongation and affects iron accumulation in rice (Oryza sativa) New Phytol. 2012;193(1):109–120. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2011.03910.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shafiq S, Chen C, Yang J, et al. DNA topoisomerase 1 prevents R-loop accumulation to modulate auxin-regulated root development in rice. Mol Plant. 2017;10(6):821–833. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2017.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Xu L, Zhao H, Ruan W, et al. ABNORMAL INFLORESCENCE MERISTEM1 functions in salicylic acid biosynthesis to maintain proper reactive oxygen species levels for root MERISTEM activity in Rice. Plant Cell. 2017;29(3):560–574. doi: 10.1105/tpc.16.00665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Li J, Zhao Y, Chu H, et al. SHOEBOX modulates root meristem size in Rice through dose-dependent effects of gibberellins on cell elongation and proliferation. PLoS Genet. 2015;11(8):e1005464. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gu M, Zhang J, Li H, et al. Maintenance of phosphate homeostasis and root development are coordinately regulated by MYB1, an R2R3-type MYB transcription factor in rice. J Exp Bot. 2017;68(13):3603–3615. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erx174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shibata M, Sugimoto K. A gene regulatory network for root hair development. J Plant Res. 2019;132:301–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 61.Slabaugh E, Held M, Brandizzi F. Control of root hair development in Arabidopsis thaliana by an endoplasmic reticulum anchored member of the R2R3-MYB transcription factor family. Plant J. 2011;67(3):395–405. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04602.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yi K, Menand B, Bell E, Dolan L. A basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor controls cell growth and size in root hairs. Nat Genet. 2010;42(3):264–267. doi: 10.1038/ng.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pires ND, Yi K, Breuninger H, Catarino B, Menand B, Dolan L. Recruitment and remodeling of an ancient gene regulatory network during land plant evolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2013;110(23):9571–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 64.Breuninger H, Thamm A, Streubel S, Sakayama H, Nishiyama T, Dolan L. Diversification of a transcription factor family led to the evolution of antagonistically acting genetic regulators of root hair growth. Curr Biol. 2016;26(12):1622–1628. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2016.04.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Xu P, Cai XT, Wang Y, Xing L, Chen Q, Xiang CB. HDG11 upregulates cell-wall-loosening protein genes to promote root elongation in Arabidopsis. J Exp Bot. 2014;65(15):4285–4295. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eru202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Giri J, Bhosale R, Huang G, et al. Rice auxin influx carrier OsAUX1 facilitates root hair elongation in response to low external phosphate. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):1408. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03850-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Song L, Yu H, Dong J, Che X, Jiao Y, Liu D. The molecular mechanism of ethylene-mediated root hair development induced by phosphate starvation. PLoS Genet. 2016;12(7):e1006194. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wang Q, Wang J, Yang Y, et al. A genome-wide expression profile analysis reveals candidate genes and pathways coping with phosphate starvation in soybean. BMC Genomics. 2016;17:192. doi: 10.1186/s12864-016-2558-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Du Q, Wang K, Xu C, et al. Strand-specific RNA-Seq transcriptome analysis of genotypes with and without low-phosphorus tolerance provides novel insights into phosphorus-use efficiency in maize. BMC Plant Biol. 2016;16:222. doi: 10.1186/s12870-016-0903-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wu P, Ma L, Hou X, et al. Phosphate starvation triggers distinct alterations of genome expression in Arabidopsis roots and leaves. Plant Physiol. 2003;132:1260–1271. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.021022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Li L, Liu C, Lian X. Gene expression profiles in rice roots under low phosphorus stress. Plant Mol Biol. 2010;72(4–5):423–432. doi: 10.1007/s11103-009-9580-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Vogt T. Phenylpropanoid biosynthesis. Mol Plant. 2010;3:2–20. doi: 10.1093/mp/ssp106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.La Camera S, Gouzerh G, Dhondt S, et al. Metabolic reprogramming in plant innate immunity: the contributions of phenylpropanoid and oxylipin pathways. Immunol Rev. 2004;198:267–284. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.0129.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lepiniec L, Debeaujon I, Routaboul JM, et al. Genetics and biochemistry of seed flavonoids. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2006;57:405–430. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.57.032905.105252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Saito K, Yonekura-Sakakibara K, Nakabayashi R, et al. The flavonoid biosynthetic pathway in Arabidopsis: structural and genetic diversity. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2013;72:21–34. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2013.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Routaboul JM, Dubos C, Beck G, et al. Metabolite profiling and quantitative genetics of natural variation for flavonoids in Arabidopsis. J Exp Bot. 2012;63:3749–3764. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ers067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Nakabayashi R, Yonekura-Sakakibara K, Urano K, et al. Enhancement of oxidative and drought tolerance in Arabidopsis by overaccumulation of antioxidant flavonoids. Plant J. 2014;77:367–379. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Catalá R, Medina J, Salinas J. Integration of low temperature and light signaling during cold acclimation response in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2011;108:16475–16480. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1107161108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Shi MZ, Xie DY. Biosynthesis and metabolic engineering of anthocyanins in Arabidopsis thaliana. Recent Pat Biotechnol. 2014;8:47–60. doi: 10.2174/1872208307666131218123538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Fei H, Ellis BE, Vessey JK. Carbon partitioning in tissues of a gain-of-function mutant (MYB75/PAP1-D) and a loss-of-function mutant (myb75-1) in Arabidopsis thaliana. Botany. 2013;92:93–99. doi: 10.1139/cjb-2013-0232. [DOI] [Google Scholar]