Abstract

Berberine, a natural isoquinoline alkaloid derived from Berberis species, has been reported to have anticancer effects. However, the mechanisms of action in human colorectal cancer (CRC) are not well established to date. In the present study, the cell cytotoxicity effect of berberine on human CRC cells, as well as the possible mechanisms involved, was investigated. The results of the cell viability and apoptosis assay revealed that treatment of CRC cells with berberine resulted in inhibition of cell viability and activation of cell apoptosis in a concentration-dependent manner. To reveal the underlying mechanism of berberine-induced anti-tumor activity and cell apoptosis, RNA-sequencing followed by reverse-transcription quantitative PCR were performed. In addition, RNA immunoprecipitation, chromatin immunoprecipitation and western blot analysis were used to identify the functional regulation of CASC2/EZH2/BCL2 axis in berberine-induced CRC cell apoptosis. The data revealed that lncRNA CASC2 was upregulated by berberine treatment. Gain- or loss-of-function assays suggested that lncRNA CASC2 was required for the berberine-induced inhibition of cell viability and activation of cell apoptosis. Subsequently, the downstream antiapoptotic gene BCL2 was identified as a functional target of the berberine/CASC2 mechanism, as BCL2 reversed the berberine/CASC2-induced cell cytotoxicity. lncRNA CASC2 silenced BCL2 expression by binding to the promoter region of BCL2 in an EZH2-dependent manner. In summary, berberine may be a novel therapeutic agent for CRC and lncRNA CASC2 may serve as an important therapeutic target to improve the anticancer effect of berberine.

Keywords: colorectal cancer, berberine, long non-coding cancer susceptibility 2, BCL2, enhancer of zeste 2 polycomb repressive complex 2 subunit

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the most malignant cancer types worldwide. In developed countries, ~100 million people suffer from CRC each year, and the mortality rate has increased in recent years (1,2). Metastasis is the major cause of mortality in patients with CRC and increases the risk of tumor recurrence (3). Currently, chemotherapy or radiotherapy following surgical resection are the main treatment options (4). The most commonly used first line chemotherapeutic drugs are 5-fluorouracil, oxaliplatin and irinotecan (5). Although progress in diagnosis and treatment of cancer has been made in the past decade, the overall survival rate for patients with CRC remains unfavorable and a relatively high proportion of patients become chemoresistant (6). Therefore, early screening and novel therapeutic approaches are essential for improved prognosis of patients with colorectal cancer.

Herbal medicines have long been accepted as useful adjuvant therapeutic agents for a number of diseases. The use of berberine as an alternative medicine is widespread in the developed world (7). Berberine is a natural isoquinoline alkaloid derived from Berberis species, including Coptis chinensis, which has been used to treat intestinal infections, particularly bacterial diarrhea, for thousands of years in China (8). Additionally, it has been reported to have antitumor effects in various types of cancer including melanoma, glioma, lung and breast cancer and hepatocellular carcinoma (9–12). Berberine may exhibit an anticancer effect in CRC (13,14); however, the underlying functional mechanism has not been fully elucidated.

Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) are a class of non-coding RNAs >200 nucleotides in length and serve an important role in regulating gene expression (15). They can regulate target gene expression level in the cytoplasm by serving as microRNA (miRNA/miR) sponges (16), and silence or activate target genes through modification at the promoter region (17,18). lncRNAs may directly interact with signaling pathways to serve as prognostic predictors or therapeutic targets for different types of cancer (19,20). Furthermore, previous reports indicated that lncRNAs may participate in chemoresistance (21,22). However, their roles in the function of berberine are poorly understood. The identification of lncRNAs involved in the function of berberine may enhance human cancer treatment and aid to overcome chemoresistance.

In the current study, the regulatory function of lncRNA cancer susceptibility 2 (CASC2) in the tumor-suppressive role of berberine in CRC was investigated. The results revealed that berberine suppressed cell viability and promoted apoptosis of human CRC cancer cell lines in a concentration-dependent manner. Furthermore, berberine treatment increased the endogenous level of lncRNA CASC2, and this upregulation of lncRNA CASC2 promoted berberine-induced cell cytotoxicity by interacting with enhancer of zeste 2 polycomb repressive complex 2 subunit (EZH2) and silencing the expression of BCL2.

Materials and methods

Ethics statement and tissue samples

The study included 60 patients with CRC [male/female ratio, 36/24; age range, 42–73 (median age, 56)] who underwent partial or total surgical resection at the West China Second University Hospital (Chengdu, China) between June 2014 and July 2016. Paired cancer tissues and normal control tissues (>2 cm distal from the cancer area) were collected by surgical resection. Tissue specimens were stored in liquid nitrogen during transportation. The current study was approved by the West China Second University Hospital. All participants signed informed consent prior to using the tissues for scientific research.

Cell culture

Five human CRC cell lines (HT-29, HCT116, SW480, SW620 and LoVo) and one human fetal normal colonic cell line (FHC) were purchased from the American Tissue Culture Collection. Human CRC cells were cultured in DMEM (BioWhittaker; Lonza Group, AG) containing 10% FBS (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and 100 U/ml penicillin and streptomycin (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) in a humidified incubator at 37°C and 5% CO2. Normal colon FHC cells were grown in DMEM/F12 medium (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) supplemented with 10% FBS, 10 ng/ml cholera toxin, 5 µg/ml transferrin, 5 µg/ml insulin, 100 ng/ml hydrocortisone and additional 10 mM 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid, at 37°C in 5% CO2 and 95% air. Berberine was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Merck KGaA; cat. no. B3251) and used at the concentration of 50 µM (diluted with PBS and added into culture medium).

Expression profile analysis of lncRNAs

Total RNA was extracted from HT29 cells treated with berberine (50 µM for 48 h) or normal culture medium using the RNeasy Plus Mini kit (Qiagen, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's protocol. lncRNAs were sequenced using the high-throughput, high-sensitivity HiSeq 2500 sequencing platform (Illumina, Inc.). cDNA was sonicate-fragmented (10-cycles of 30 sec on and 30 sec off at 4°C; Bioruptor®; Diagenode, Inc.) to an average size of 250 bp to construct a cDNA library. Data processing and statistical analysis for the RNA-sequencing data were performed (R software version 3.5.2, Lucent Technologies Inc.) and a heat map was subsequently generated by using ggplot2 R package (http://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/ggplot2/).

Vector construction and cell transfection

The synthetic silencing oligonucleotides used for small interfering RNAs (siRNAs), si-CASC2 and si-EZH2, were synthesized by Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd. Negative control siRNA (cat. no. 12935-110; Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) was used. The sequences of small-interfering RNAs are presented in Table I. The CASC2 overexpression vector (p-CASC2) was generated by cloning the specific sequences of CASC2 into a pcDNA 3.1 vector (synthesized by Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd.). The vectors were labeled with green fluorescence protein (GFP) to confirm the transfection. For overexpression experiments, CRC cells in 6-well plate were transfected with the plasmids (2,000 ng/well) using TransFast™ Transfection Reagent (Promega Corporation) according to the manufacturer's protocol. For knockdown experiments, a total of 5×105 HT29 or HCT116 cells were seeded into each well of a 6-well plate and transfected with the oligoribonucleotides (100 nM) upon reaching 70–80% confluence. The change in the expression levels of the target genes was determined by the reverse-transcription quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) at 24 h after transfection. The transfected cells were subsequently used for functional assays.

Table I.

Primer and siRNA sequences.

| A, RT-qPCR primers | |

|---|---|

| Name | Sequence (5′-3′) |

| CASC2 (Forward) | GCACATTGGACGGTGTTTCC |

| CASC2 (Reverse) | CCCAGTCCTTCACAGGTCAC |

| EZH2 (Forward) | GGCTCCTCTAACCATGTTTACAACT |

| EZH2 (Reverse) | AGCGGTTTTGACACTCTG AACTAC |

| BCL2 (Forward) | TCT TCCAGGAACCTCTGTGATG |

| BCL2 (Reverse) | CAATGCCGCCATCGCTTACACC |

| GAPDH (Forward) | GCACCGTCAAGGCTGAGAAC |

| GAPDH (Reverse) | ATGGTGGTGAAGACGCCAGT |

| B, RIP-qPCR primers | |

| Name | Sequence (5′-3′) |

| CASC2 (Forward) | GCACATTGGACGGTGTTTCC |

| CASC2 (Reverse) | CCCAGTCCTTCACAGGTCAC |

| lncRNA control (Forward) | GGGTGTTTACGTAGACCAGAA |

| lncRNA control (Reverse) | CTTCCAAAAGCCTTCTGCCTTA |

| β-actin (Forward) | CTCGCTTCGGCAGCACATATAC |

| β-actin (Reverse) | AACGCTTCACGAATTTGCGTGT |

| C, ChIP-qPCR primers | |

| Name | Sequence (5′-3′) |

| BCL2-A (Forward) | GAGGAGCCATCCGCACATCA |

| BCL2-A (Reverse) | AGCTTAGACTGTAAGCTGGT |

| BCL2-B (Forward) | AGTCCCACAACAGCATAGGG |

| BCL2-B (Reverse) | TCCCTAGGTCAGGACCACCT |

| BCL2-C (Forward) | CTCCAGCTTGGGTGAAAGAG |

| BCL2-C (Reverse) | GGGCTTTTACACTTGGCTAG |

| GAPDH-D (Forward) | AGGGAAGCTGACAGGGATGGCG |

| GAPDH-D (Reverse) | ATCGAAGATGGACGAGTGGGTA |

| GAPDH-E (Forward) | CCCCGCTACTCCTCCTCCTAAG |

| GAPDH-E (Reverse) | TCCACGACCAGTTGTCCATTCC |

| D, siRNA | |

| Name | Sequence (5′-3′) |

| si-CASC2-1 | UGAAAAGAGCCGUGAGCUA |

| si-CASC2-2 | AAATAAAGATGGTGGAATG |

| si-CASC2-3 | CUGCAAGGCCGCAUGAUGA |

| si-EZH2 | AUCAGCUCGUCUGAACCUCUU |

| si-NC (GFP) | GGCUACGUCCAGGAGCGCACC |

siRNA, small interfering RNA; RT, reverse transcription; qPCR, quantitative PCR; CASC2, cancer susceptibility 2; EZH2, enhancer of zeste 2 polycomb repressive complex 2 subunit; RIP, RNA immunoprecipitation; ChiP, chromatin immunoprecipitation; NC, negative control.

RNA extraction and RT-qPCR

Total RNA was extracted from cells or tissue samples by using the RNeasy Plus Mini kit (Qiagen, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The 20 µl RT reactions were performed using a PrimeScript® RT reagent kit (Takara Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Dalian, China) and incubated for 30 min at 37°C and 5 sec at 85°C. Subsequently, 2 µl of diluted RT product was mixed with 23 µl reaction buffer (Takara Inc.) to a final volume of 25 µl. The primer sequences are presented in Table I. All reactions labeled with SYBRGreen (Takara Inc.) were carried out using an Eppendorf Mastercycler EP Gradient S (Eppendorf) under the following conditions: 95°C for 30 sec, followed by 45 cycles of 95°C for 5 sec and 60°C for 30 sec. The expression levels of detected RNAs were normalized to GAPDH using the comparative 2−ΔΔCq method (23).

Cell viability assay

The cell viability following treatment with berberine was assayed using the MTT assay (Dojindo Molecular Technologies, Inc.). In brief, 3×104 cells were seeded into a 96-well plate and treated with 0–100 µM berberine (cat. no. B3251; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) or PBS control for 12–72 h. The cells were treated with the 10 µl MTT reagent and incubated for an additional 2 h at room temperature. Purple formazan was then dissolved by adding 150 µl DMSO (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) to each well. The optical density at a wavelength of 450 nm was subsequently measured with a spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.).

Apoptosis assay

Cells in 6-well plate (1–5×106/ml) were collected following berberine treatment (50 µM) or transient transfection for 48 h, and washed with PBS and 0.025% trypsin-EDTA to obtain single-cell suspensions. Cells were fixed in ice-cold 70% ethanol (60 min at 4°C) and stained with an Annexin V FITC and propidium iodide solution kit (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) for 20 min at room temperature. Apoptosis was detected using a flow cytometer (BD FACSCalibur™; BD Biosciences) and analysed using Modfit LT version 5.0 software (Verity Software House Inc.).

Cell migration and invasion assay

Cell migration was evaluated by performing a wound-healing assay. The cells were seeded at a density of 5×105 cell/well into six-well plates. After 12 h of treatment with 50 µM berberine and/or transfection with si-CASC2, the layer of cells was scratched using a sterile 20 µl pipette tip to form wounds. The non-adherent cells were washed away with culture medium, and the cells were cultured for 48 h followed by measurement of the gap area. Cell invasive ability was evaluated using a Transwell invasion assay using Boyden chambers (8 µm pore size; BD Biosciences). The membranes were coated with Matrigel. Cells in serum-free media were placed into the upper chamber. Media containing 10% FBS was added to the lower chamber. Following 24 h of incubation at 37°C, the cells that had invaded through the membrane were fixed with 100% methanol for 20 min at room temperature and stained with 0.1% crystal violet for 10 min at room temperature and 3 random fields were imaged using an inverted microscope at 10× magnification (Leica Microsystems, Inc., Buffalo Grove, IL, USA).

RNA immunoprecipitation (RIP)

HT29 and HCT116 cells were rinsed with cold PBS and fixed using 1% formaldehyde for 10 min. Following 10 min centrifugation at 1,5000 × g and 4°C, cell pellets were collected and re-suspended in NP-40 lysis buffer (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). The RIP assay was performed using the Magna RIP™ RNA-Binding Protein Immunoprecipitation kit (EMD Millipore) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Total RNA was immunoprecipitated overnight at 4°C with an antibody against EZH2 (1:50, cat. no. ab186006; Abcam) or negative control IgG (1:50, cat. no. 12-370, EMD Millipore). The magnetic bead bound complexes were immobilized with a magnet and unbound materials were washed off. RNA was extracted and analyzed by RT-qPCR.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)

An EZ-Magna ChIP kit (EMD Millipore) was used according to the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, HT29 cells (1×106/ml) were treated with 4% paraformaldehyde and incubated for 10 min at 4°C to generate DNA-protein cross-links. Cell lysates were then sonicated for with a 10 sec on and 10 sec off mode for 12 cycles to generate chromatin fragments of 200–300 bp and immunoprecipitated overnight at 4°C with anti-EZH2 antibody (1:50, cat. no. ab186006; Abcam), anti-H3K27me3 antibody (1:50, cat. no. ab6002; Abcam) or the negative control IgG (1:50, cat. no. 12-370; EMD Millipore). Two sites in the GAPDH promoter region were used as a control for the identification of interactions between GAPDH and BCL2. Precipitated DNA was recovered and analyzed by RT-qPCR.

Western blot and antibodies

RIPA assay buffer (Sigma Aldrich; Merck KGaA) was used to extract proteins from the cells. Protein concentration was measured using a bicinchoninic acid assay (Sigma Aldrich; Merck KGaA). The same quantity of protein (25 µg) was transferred onto PVDF membranes following the separation process by performing a routine SDS-PAGE with 10% gel. The membrane was blocked with 5% (5 g/100 ml) nonfat dry milk in TBS plus Tween buffer for 2 h at room temperature. The membrane was incubated with primary antibodies against EZH2 (1:1,000; cat. no. ab186006; Abcam), BCL2 (1:1,000; cat. no. ab32124; Abcam) and β-actin (1:1,000; cat. no. ab8227; Abcam) overnight at 4°C. Following primary incubation, membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:5,000; cat. no. 7074; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.) for 1 h at room temperature. Protein bands were detected using ECL reagent (Amersham; GE Healthcare). Gray analysis by image analysis was performed using the software Gel-Pro Analyzer (version 4.0; United States Biochemical) after scanning.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as the median and interquartile range. The Mann-Whitney U test was used for the comparison of datasets containing two independent groups, and the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used for comparison of paired samples. The Kruskal-Wallis test followed by the Bonferroni post hoc analysis was used for evaluating the differences among multiple groups. The Spearman's test was used to analyze the correlation between CASC2 and BCL2 mRNA expression. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism (version 6; GraphPad Software, Inc.). P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

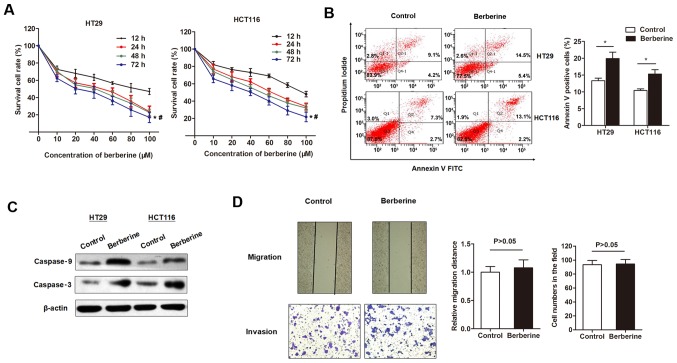

Berberine suppresses cell viability and promotes apoptosis in CRC cells

The inhibitory effects of berberine on the cell viability of CRC cell lines was investigated. The MTT assay indicated that berberine decreased the in vitro cell viability of two CRC cell lines in a dose-dependent manner, with a half maximal inhibitory concentration of 43.77 µM for HT29 and 56.44 µM for HCT116 at 48 h post-treatment (Fig. 1A). Flow cytometry analysis was subsequently used to detect cell apoptosis. The percentage of apoptotic cells was significantly increased following treatment with 50 µM berberine for 48 h compared with controls (Fig. 1B). To investigate whether the increased cell apoptosis was due to activation of apoptotic signaling pathways, the expression levels of several apoptotic proteins were detected. Western blotting revealed that the expression levels of cleaved caspase-3 and −9 were upregulated by the treatment of berberine at 50 µM for 48 h (Fig. 1C). The effect of berberine on migration and invasion capacity of HT29 cells were assessed by performing scratch and Transwell assays, respectively. The results revealed that berberine treatment did not have a significant effect on cell migration and invasion compared with controls (Fig. 1D).

Figure 1.

Berberine inhibited cell growth and promoted apoptosis in colorectal cancer cells lines. (A) The MTT assay indicated that berberine decreased the in vitro cell viability of HT29 and HCT116 cells in a dose-dependent manner, with an IC50 of 43.77 µM for HT29 and 56.44 µM for HCT116 48 h following treatment. *P<0.05 vs. 12 h group; #P<0.05 vs. 10 µM incubation group. (B) The flow cytometry apoptosis assay revealed that the percentage of apoptotic cells significantly increased following treatment with berberine (50 µM) for 48 h. *P<0.05, as indicated. (C) Western blotting suggested that berberine treatment (50 µM) promoted the expression levels of the pro-apoptotic proteins, cleaved caspase-3 and −9. (D) Berberine treatment (50 µM) did not significantly affect HT29 cell migration and invasion compared with normal cultured cells. Magnification, ×20.

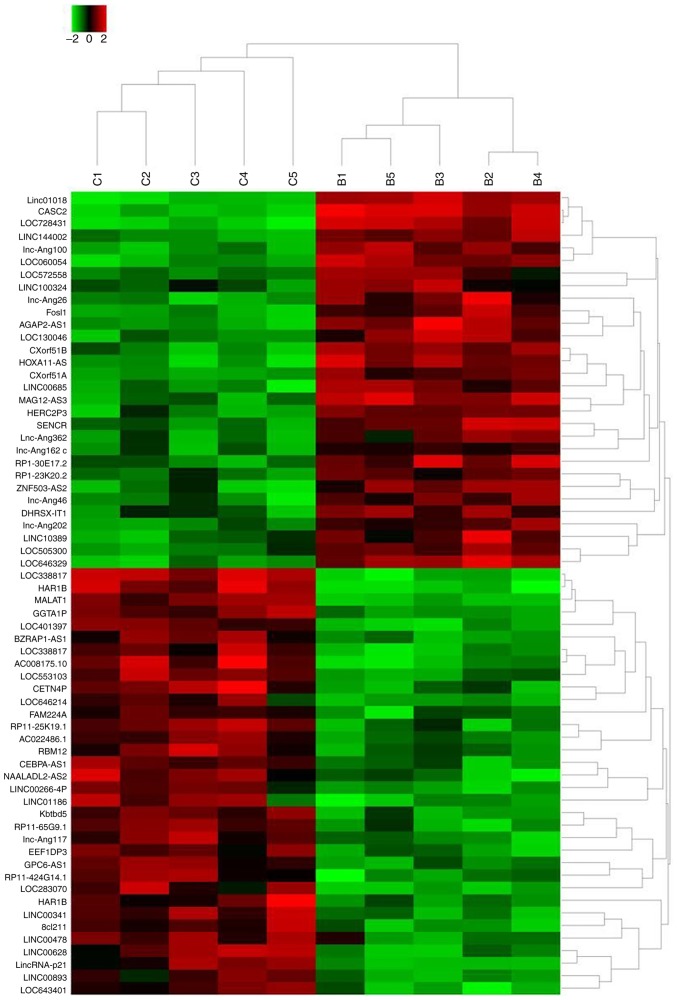

lncRNA expression profile of CRC cell lines

On the basis of the aforementioned observations, the pathways underlying berberine-induced apoptosis were further investigated. lncRNAs are important regulators for the proliferation and apoptosis of cancer cells as well as chemotherapy resistance (24). Therefore, the current study aimed to identify specific lncRNAs altered by berberine treatment. High-throughput lncRNA sequencing was performed using 50 µM berberine-treated HT29 cells and cells cultured with normal condition. The results revealed that a total of 64 lncRNAs exhibited >2-fold change in expression between berberine-treated cells and non-treated cells (Fig. 2). Specifically, the expression of 30 lncRNAs was increased following the treatment of berberine compared with control treatment. LINC01018 had 49.7953-fold higher expression, ranking as the most differentially expressed, followed by lncRNA CASC2 and LOC728431. In addition, a total of 34 lncRNAs exhibited decreased expression levels following berberine treatment. LOC338817 showed the lowest expression level (55.4954-fold lower compared with controls), followed by HAR1B and lncRNA MALAT1 (Table II).

Figure 2.

High-throughput lncRNA sequencing identified 64 lncRNAs with a >2-fold difference between HT29 cells treated with berberine-containing medium and cells cultured in berberine-free medium were identified. R package was used to establish a heat map. B, berberine (50 µM)-treated HT29 cells; C, control HT29 cells.

Table II.

Candidate lncRNAs selected on a basis of the sequencing analysis.

| lncRNA | Location | Regulation (B vs. C) | Fold change | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LINC01018 | Chr5p15.31 | Up | 49.7953 | 0.00030542 |

| CASC2 | Chr10p26.11 | Up | 35.5740 | 0.00079371 |

| LOC728431 | Chr1p34.3 | Up | 24.1439 | 0.00135860 |

| LOC338817 | Chr12p13.2 | Down | 55.4954 | 0.00012671 |

| HAR1B | Chr20q13.33 | Down | 44.3649 | 0.00039834 |

| MALAT1 | Chr11p13.1 | Down | 31.7852 | 0.00068024 |

lncRNA, long non-coding RNA; B, berberine-treated cells; C, control cells; LINC01018, long intergenic non-protein coding RNA 1018; CASC2, cancer susceptibility 2; LOC728431, long intergenic non-protein coding RNA 1137; HAR1B, highly accelerated region 1B; MALAT1, metastasis associated lung adenocarcinoma transcript 1.

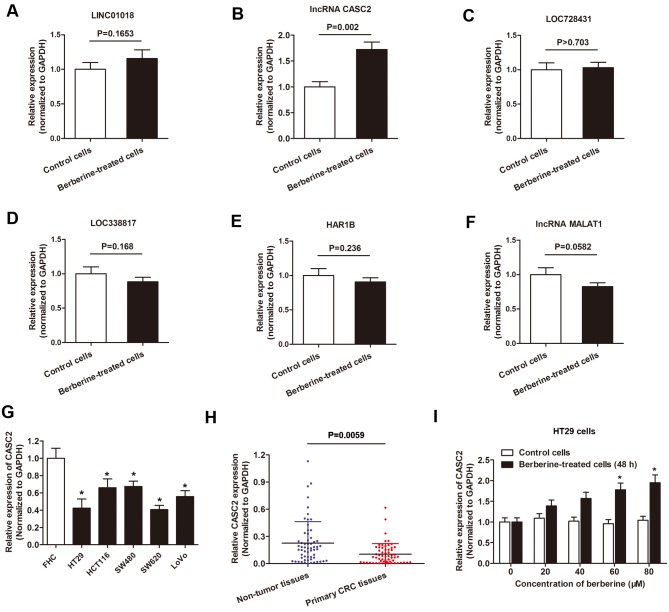

Expression level of lncRNA CASC2 in CRC cell lines is increased following berberine treatment

The aforementioned dysregulated lncRNA(s) were validated using qPCR. Compared with the RNA sequencing data, only lncRNA CASC2 showed a statistically significant increased expression level in HT29 cells following berberine treatment compared with controls. Expression of the other five lncRNAs showed little difference between the two group of cells when analyzed by RT-qPCR (Fig. 3A-F). Therefore, the functional role of CASC2 was investigated further. Previous reports indicated that lncRNA CASC2 may be involved in cell apoptosis, proliferation and cell cycle regulation in cancer (25,26). Therefore, berberine may decrease CRC cell viability and promote apoptosis through the upregulation of lncRNA CASC2. To investigate this hypothesis, the expression level of lncRNA CASC2 in CRC cell lines was determined. The results revealed that the expression level of lncRNA CASC2 was decreased in the five CRC cell lines used in the present study compared with the normal colon epithelial cell line FHC (Fig. 3G). In addition, CASC2 was downregulated in primary CRC tissues when compared with non-tumor tissues (Fig. 3H). Furthermore, lncRNA CASC2 was upregulated in HT29 cells following treatment with berberine for 48 h in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3I).

Figure 3.

lncRNA CASC2 was upregulated by berberine treatment in CRC. A-F. RT-qPCR analysis of the six indicated lncRNAs, (A) LINC01018, (B) CASC2, (C) LOC728431, (D) LOC33817, (E) HAR1B, (F) MALAT1, in HT29 cells cultured with berberine-containing medium or berberine-free medium. (G) lncRNA CASC2 expression was measured using RT-qPCR in the indicated cell lines. *P<0.05 vs. FHC cells. (H) lncRNA CASC2 level was detected via RT-qPCR in paired CRC tissues and adjacent non-tumor tissues obtained from patients with CRC. The expression of lncRNA CASC2 was significantly downregulated in primary CRC tissues when compared with noncancerous tissues. (I) lncRNA CASC2 level was increased in HT29 cells following treatment with berberine at increasing concentrations for 48 h. *P<0.05 vs. control cells. lncRNA, long non-coding RNA; CASC2, cancer susceptibility 2; CRC, colorectal cancer; RT-qPCR, reverse-transcription quantitative PC; LINC01018, long intergenic non-protein coding RNA 1018; LOC728431, long intergenic non-protein coding RNA 1137; MALAT1, metastasis associated lung adenocarcinoma transcript 1.

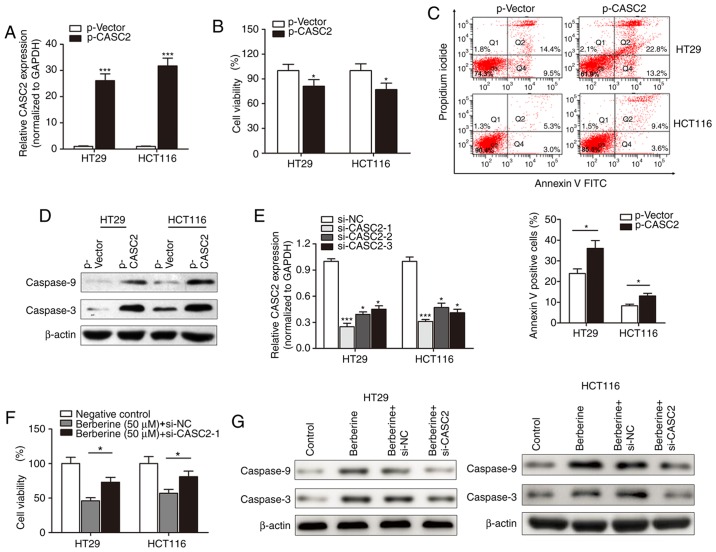

Berberine suppresses cell viability and promotes apoptosis by inducing expression of lncRNA CASC2

Following the investigation of the expression of lncRNA CASC2 in berberine-treated CRC cells, the functional role of CASC2 in berberine-induced cell apoptosis and cytotoxicity was determined. lncRNA CASC2 was significantly upregulated in HT29 and HCT116 cells following transfection with p-CASC2 compared with the control vector (Fig. 4A). The MTT assay suggested that lncRNA CASC2 suppressed cell viability in HT29 and HCT116 cells (Fig. 4B). Flow cytometry revealed that overexpression of CASC2 significantly increased the number of HT29 and HCT116 apoptotic cells compared with cells transfected with control vectors (Fig. 4C). Western blotting indicated that p-CASC2 resulted in increased expression of the pro-apoptotic proteins, cleaved caspase-3 and −9 compared with the control vector (Fig. 4D). Subsequently, si-CASC was used to determine whether lncRNA CASC2 was associated with the function of berberine. si-CASC2-1 demonstrated the best silencing effect when compared with the other two inhibitors, and was thus used for subsequent experiments (Fig. 4E). si-CASC2-1 reduced the berberine-induced inhibition of cell viability in HT29 and HCT116 cell lines (Fig. 4F). Similarly, si-CASC2-1 attenuated the berberine-induced increase in expression of cleaved caspase-3 and −9 (Fig. 4G).

Figure 4.

Berberine inhibited cell growth and increased apoptosis by increasing the expression level of CASC2. (A) The expression level of CASC2 was significantly increased in HT29 and HCT116 cells transfected with the p-CASC2 vector. ***P<0.001 vs. p-Vector group. (B) MTT assay was performed to investigate the effects of CASC2 on cell viability. The cell viability was significantly decreased in cells transfected with the p-CASC2 vector. *P<0.05 vs. p-Vector group. (C) Apoptosis was significantly increased in HT29 and HCT116 cells overexpressing CASC2. *P<0.05 vs. p-Vector group. (D) Western blotting revealed that the overexpression of CASC2 increased the expression level of cleaved caspase-3 and −9. (E) Three siRNAs against CASC2 were generated and validated by performing reverse transcription-quantitative PCR. *P<0.05, ***P<0.001 vs. si-NC group. (F) Berberine treatment (50 µM, 48 h) significantly inhibited the viability of HT29 and HCT116 cells; however, this was partly nullified by knockdown of CASC2. *P<0.05, as indicated. (G) Knockdown of CASC2 partially reversed the inhibition of cleaved caspase-3 and −9 in HT29 and HCT116 cells caused by berberine treatment. CASC2, cancer susceptibility 2; siRNA, small interfering RNA; NC, negative control.

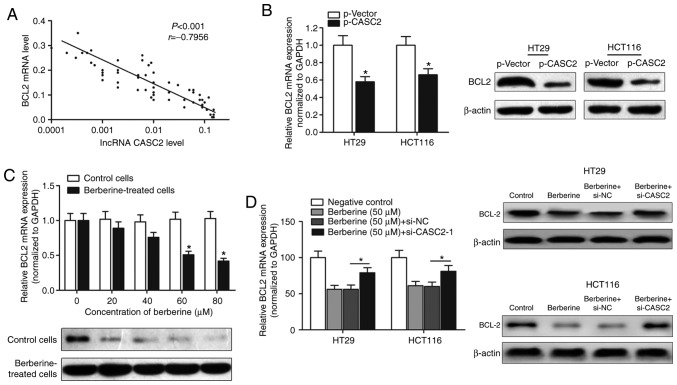

BCL2 is required for the functional effect induced by berberine and lncRNA CASC2

As the berberine/CASC2 signaling pathway affected apoptosis in CRC cell lines, the expression of apoptosis-targeted genes was investigated. Significant differences in several apoptosis-related targets regulated by lncRNA CASC2, including BCL2, which is a well-known antiapoptotic protein (27,28), were identified (Table III). Thus, lncRNA CASC2 may promote apoptosis via targeting the antiapoptotic gene, BCL2. The expression level of BCL2 in CRC tissue samples was determined using RT-qPCR. A significant negative correlation between the expression of BCL2 and lncRNA CASC2 was identified (Fig. 5A). Moreover, overexpression of CASC2 decreased the expression of BCL2 at the transcript and protein levels, as demonstrated by RT-qPCR and western blot analysis (Fig. 5B). BCL2 mRNA and protein levels were decreased in HT29 cells treated with berberine in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 5C). However, transfection with si-CASC-1 reversed the berberine-induced decrease of BCL2 mRNA and protein levels (Fig. 5D), suggesting that berberine exerted its proapoptotic effect via a CASC2-BCL2 signaling mechanism.

Table III.

Long non-coding RNA CASC2 regulated target genes associated with apoptosis.

| Gene symbol | Gene name | Location | Fold change (p-CASC2/negative control, all P<0.005) |

|---|---|---|---|

| BCL2 | BCL2 apoptosis regulator | Chr18q21.33 | 0.008 |

| BCL2A1 | BCL2 related protein A1 | Chr15q25.1 | 0.06 |

| PARP2 | Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase 2 | Chr14q11.2 | 0.19 |

| BIRC3 | Baculoviral IAP repeat containing 3 | Chr11q22.2 | 0.52 |

| BAX | BCL2-associated X, apoptosis regulator | Chr19q13.33 | 25.39 |

| MCL1 | MCL1 apoptosis regulator, BCL2 family member | Chr1q21.2 | 19.31 |

| BAK1 | BCL2 antagonist/killer 1 | Chr6p21.31 | 10.48 |

| CASP9 | Caspase 9 | Chr1p36.21 | 9.56 |

| CASP3 | Caspase 3 | Chr4p35.1 | 7.38 |

CASC2, cancer susceptibility 2.

Figure 5.

BCL2 was identified as a direct target of berberine and CASC2 in CRC. (A) The expression levels of long non-coding RNA CASC2 and BCL2 transcripts in primary CRC tissues were determined via reverse transcription-quantitative PCR and the correlation between their expression was determined using Spearman's correlation test. (B) Enhanced expression of CASC2 increased BCL2 expression at the mRNA (left panel) and protein (right panel) levels. *P<0.05 compared with the p-vector group. (C) BCL2 mRNA and protein was decreased in HT29 treated with berberine in a dose-dependent manner. *P<0.05 vs. respective control group. (D) Transfection with si-CASC-1 reversed the berberine-induced decrease of BCL2 at the mRNA (left panel) and protein levels (right panel). *P<0.05, as indicated. CASC2, cancer susceptibility 2; CRC, colorectal cancer; siRNA, small interfering RNA; NC, negative control.

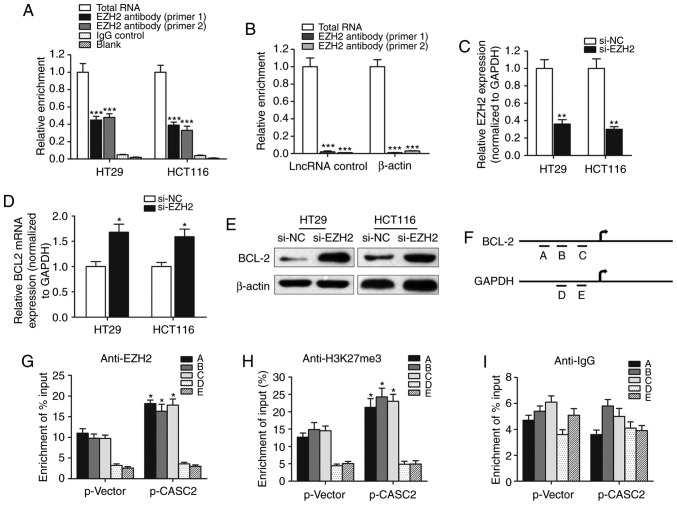

EZH2 associates with lncRNA CASC2, which subsequently suppresses BCL2 expression

A RIP assay was performed to identify whether there was a direct interaction between lncRNA CASC2 and EZH2. CASC2 was pulled down by EZH2 while no enrichment was identified when using an IgG antibody as a control (Fig. 6A). Moreover, no enrichment was identified when using the EZH2 antibody to pull down β-actin or lncRNA control, suggesting that the association between EZH2 and CASC2 was specific (Fig. 6B). Furthermore, the role of EZH2 in the regulation of BCL2 expression was evaluated. si-EZH2 was used to silence EZH2 in HT29 and HCT116 cells (Fig. 6C). Knockdown of EZH2 in HT29 and HCT116 cells upregulated the expression level of BCL2 (Fig. 6D and E). A ChIP assay was performed to detect the effect of lncRNA CASC2 on histone modification in the BCL2 gene promoter in HT29 cells. A set of detection sites were used to design specific primers for the amplification of BCL2 promoter sequences pulled down by anti-EZH2 or anti-H3K27-me3 antibodies (Fig. 6F). Overexpression of CASC2 significantly increased the enrichment of BCL2 (detection site A, B and C) when using the anti-EZH2 and anti-H3K27me3 antibodies, while no significant change in the enrichment level was identified for GAPDH (detection site D and E; Fig. 6G and H). In addition, lncRNA CASC2 had little effect on the enrichment of BCL2 when using the anti-IgG antibody (Fig. 6I). To conclude, the current study revealed that lncRNA CASC2 downregulated BCL2 expression level in CRC by binding with the promoter region of BCL2 in an EZH2-dependent manner.

Figure 6.

lncRNA CASC2 decreased the expression level of BCL2 by binding with EZH2. (A) RIP experiments were performed to verify the direct interaction between EZH2 and lncRNA CASC2 by using an anit-EZH2 antibody. Primers used for amplifying CASC2 were generated to verify the enrichment of lncRNA CASC2 pulled down by the anti-EZH2 antibody. ***P<0.001 vs. control IgG group. (B) lncRNA control or β-actin was used as a negative control for CASC2. A RIP assay was performed using EZH2 antibody. ***P<0.001 vs. total RNA group. (C) The silencing effect of siRNA against EZH2 was determined via quantitative PCR. **P<0.01 vs. si-NC group. BCL2 (D) mRNA and (E) protein levels were measured in cells with EZH2 knockdown. *P<0.05 vs. si-NC group. (F) Chromatin immunoprecipitation analysis of HT29 cells overexpressing CASC2 was performed with generated primers to detect the amplification at the BCL2 promoter (detection sites A, B and C) and GAPDH promoter (detection sites D and E) regions. Measurement of BCL2 sequences with (G) EZH2, (H) H3K27m3 and (I) IgG is presented as relative to total input. *P<0.05 compared with the p-Vector group, respectively. lncRNA, long non-coding RNA; CASC2, CASC2, cancer susceptibility 2; EZH2, enhancer of zeste 2 polycomb repressive complex 2 subunit; RIP, RNA immunoprecipitation; siRNA, small interfering RNA; NC, negative control; H3K27m3, H3 lysine 27 trimethylation.

Discussion

Patients with advanced colon cancer that develop resistance to chemotherapy currently have limited therapeutic options in the clinic; therefore, many patients turn to alternative treatments (29). In recent years, the interest in herbal remedies has grown rapidly in the industrialized world, s these drugs are increasingly considered to be effective and safe alternatives to synthetic drugs. The present study focused on berberine, one of the few well-established plant products supported by clinical trials (30,31), which is the standardized extract from Coptis chinensis. The results obtained in the current study indicated that berberine inhibited the viability and promoted apoptosis of CRC cell lines. High throughput RNA sequencing identified lncRNA CASC2 as a potential functional target of berberine, and that CASC2 is involved in the chemopreventive functions of berberine. The antiapoptotic protein BCL2 was investigated and it was revealed that lncRNA CASC2 exerted its effect by suppressing BCL2 expression via EZH2.

Alkaloids are used in traditional medicine for the treatment of many diseases. These compounds are synthesized in plants as secondary metabolites and have several effects on cellular metabolism (32). The medicinal alkaloid isolated from Coptis chinensis, berberine, has attracted attention in the scientific community (33). For example, Piyanuch et al (34) demonstrated that berberine upregulated the expression levels of growth differentiation factor 15 and activating transcription factor 3 in colorectal cancer. Liu et al (35) suggested that berberine may exert antitumor effects in CRC by regulating miR-429. Chuang et al (36) indicated an anticancer role of berberine via the suppression of cell viability of hepatocellular cancer cells and the upregulation of the protein expression of multiple tumor suppressor genes. The role of berberine in CRC was further explored by Liu et al (14), which revealed that berberine inhibited the invasion and metastasis of CRC cells via the prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2/prostaglandin E2 mediated Janus kinase 2/STAT3 signaling pathway. However, the mechanism underling the cytotoxic effect of berberine and whether one or a cluster of lncRNAs are involved in this process remains unknown. The present study suggested that berberine suppresses the viability of CRC cell lines and promotes cell apoptosis in a dose-dependent manner. Moreover, RNA sequencing indicated that a number of lncRNAs may be important regulators of the berberine-dependent pathway.

During the past years, miRNAs and lncRNAs have been investigated as potential diagnostic predictors or therapeutic targets for a number of different diseases (37). lncRNAs may have novel regulatory roles in cancer and may serve as potential prognostic and therapeutic targets in clinical practice (38). However, the specific functional association between lncRNAs and berberine in cancer is not well known. Therefore, the current study sought to identify and validate specific lncRNAs, which may be important for the antitumor effects exhibited by berberine. By combining RNA sequencing array with RT-qPCR validation, lncRNA CASC2 was identified as an lncRNA that was regulated by berberine treatment. Furthermore, the gain- and loss-of-function assays revealed that berberine exerted its anticancer effect by upregulating lncRNA CASC2 expression.

lncRNA CASC2, a novel human lncRNA mapping to 10q26 in humans, has been originally characterized as a downregulated gene acting as a tumor suppressor gene in endometrial cancer (39), and recently in other cancers (25,40,41). Exogenous expression of CASC2 significantly inhibited the growth of undifferentiated endometrial cancer cells (39). Fan et al (42) revealed that CASC2 promoted the apoptosis of hepatocellular carcinoma cells by targeting miR-24. Ba et al (43) reported that the decreased expression of lncRNA CASC2 facilitated osteosarcoma growth and invasion by regulating miR-181a. Huang et al (44) demonstrated that lncRNA CASC2 inhibited CRC cell proliferation and tumor growth by sponging miR-18a and silencing the STAT3 gene. The aforementioned studies demonstrated a decreased expression of CASC2 in cancer tissues compared with normal tissues. The results obtained in the current study revealed that CASC2 was downregulated in CRC cells compared with normal epithelial cells, consistent with the aforementioned studies. Furthermore, the current study investigated the regulatory mechanism that may account for the role of CASC2 following treatment with berberine. The antiapoptotic gene, BCL2, was identified as a functional target of CASC2. Gain- and loss-of-function experiments revealed that berberine exerted its proapoptotic effect via a CASC2-BCL2 signaling mechanism.

Antiapoptosis is established as an important factor in the development of drug resistance, and disruptions of the apoptotic pathway have been demonstrated to suppress cell cytotoxicity and promote drug resistance (45). BCL2 was identified as the most dysregulated protein following silencing of lncRNA CASC2 in the current study. BCL-2 family proteins, which include BCL-2, BCL-XL, BCL-W, MCL1 apoptosis regulator BCL2 family member and BCL2 related protein A1, share structural homology in the BCL2 homology 1, 2, 3 and 4 domains. BCL2 is an important cell death regulator, and is involved in the control of the release of cytochrome c from mitochondria in the intrinsic apoptotic pathway (46–48). Thus, the current study investigated whether lncRNA CASC2 promoted apoptosis via antiapoptotic gene, BCL2. Currently, the specific mechanism by which lncRNA CASC2 regulates BCL2 remains unclear. Consequently, the current study focused on EZH2, which is frequently associated with other lncRNAs and affects cancer progression by altering H3K27 trimethylation and silencing transcription. lncRNAs may exert their function by recruiting RNA-binding portions, including EZH2, thus leading to gene methylation and chromatin modifications. EZH2 is often overexpressed in different types of human cancer and may promote cell proliferation, invasion and tumor angiogenesis. The RIP experiment in the current study revealed that lncRNA CASC2 was physically associated with EZH2 in CRC cells. It is known that EZH2 enhances methylation of H3K27, leading to gene silencing involved in cancer progression and cell apoptosis (49). This accords with the ChIP results of the present study, which indicated that overexpression of CASC2 increased binding of EZH2 at the promoter region of the BCL2 gene, causing elevated H3K27me3 formation, and potentially inhibiting the antiapoptotic effect of BCL2.

The present study had limitations. The cytotoxic effect of berberine requires further validation in in vivo models. Experimental conditions for the treatment of CRC tumors with berberine in mice, including the concentration, duration of treatment and administration route of berberine are to be determined. The diagnostic and prognostic functions of CASC2 expression in patients with CRC receiving berberine treatment remain unclear. Future experiments focused on the clinical importance of CASC2 in berberine treatment are required.

In conclusion, the current study revealed that berberine decreases cell viability and promote apoptosis of CRC cell lines in vitro. Moreover, mechanistic research suggested that berberine exerted its anticancer effect in CRC by increasing the expression level of lncRNA CASC2 and suppressing BCL2 in an EZH2-dependent manner. Thus, berberine may be a potential alternative treatment drug for patients with CRC, and lncRNA CASC2 may serve as an important therapeutic target to improve the anticancer effect of berberine.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Science Foundation of the Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 81301399) and the Sichuan Science and Technology Department Key Research and Development Project (grant no. 2017SZ0122).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

WD and LM acquired the data, and created a draft of the manuscript; YC and YL collected clinical samples and performed the experimental assays; PC, HX and XW analyzed and interpreted the data, and performed statistical analysis; WD, LM, YC and HX reviewed the manuscript, and produced the figures and tables. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the West China Second University Hospital. All participants signed informed consent prior to using the tissues for scientific research.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Engholm G, Kejs AM, Brewster DH, Gaard M, Holmberg L, Hartley R, Iddenden R, Møller H, Sankila R, Thomson CS, Storm HH. Colorectal cancer survival in the Nordic countries and the United Kingdom: Excess mortality risk analysis of 5 year relative period survival in the period 1999 to 2000. Int J Cancer. 2007;121:1115–1122. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jansen MC, Bueno-de-Mesquita HB, Buzina R, Fidanza F, Menotti A, Blackburn H, Nissinen AM, Kok FJ, Kromhout D. Dietary fiber and plant foods in relation to colorectal cancer mortality: The Seven Countries Study. Int J Cancer. 1999;81:174–179. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19990412)81:2<174::AID-IJC2>3.0.CO;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tomida C, Aibara K, Yamagishi N, Yano C, Nagano H, Abe T, Ohno A, Hirasaka K, Nikawa T, Teshima-Kondo S. The malignant progression effects of regorafenib in human colon cancer cells. J Med Invest. 2015;62:195–198. doi: 10.2152/jmi.62.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goldberg RM, Sargent DJ, Morton RF, Fuchs CS, Ramanathan RK, Williamson SK, Findlay BP, Pitot HC, Alberts SR. A randomized controlled trial of fluorouracil plus leucovorin, irinotecan, and oxaliplatin combinations in patients with previously untreated metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:23–30. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.09.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hiraki M, Nishimura J, Takahashi H, Wu X, Takahashi Y, Miyo M, Nishida N, Uemura M, Hata T, Takemasa I, et al. Concurrent targeting of KRAS and AKT by miR-4689 Is a novel treatment against mutant KRAS colorectal cancer. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 2015;4:e231. doi: 10.1038/mtna.2015.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wasserman I, Lee LH, Ogino S, Marco MR, Wu C, Chen X, Datta J, Sadot E, Szeglin B, Guillem JG, et al. smad4 loss in colorectal cancer patients correlates with recurrence, loss of immune infiltrate, and chemoresistance. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25:1948–1956. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-1726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li D, Zhang Y, Liu K, Zhao Y, Xu B, Xu L, Tan L, Tian Y, Li C, Zhang W, et al. Berberine inhibits colitis-associated tumorigenesis via suppressing inflammatory responses and the consequent EGFR signaling-involved tumor cell growth. Lab Invest. 2017;97:1343–1353. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2017.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li G, Zhao M, Qiu F, Sun Y, Zhao L. Pharmacokinetic interactions and tolerability of berberine chloride with simvastatin and fenofibrate: An open-label, randomized, parallel study in healthy Chinese subjects. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2019;13:129–139. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S185487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Choi MS, Yuk DY, Oh JH, Jung HY, Han SB, Moon DC, Hong JT. Berberine inhibits human neuroblastoma cell growth through induction of p53-dependent apoptosis. Anticancer Res. 2008;28:3777–3784. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang N, Feng Y, Zhu M, Tsang CM, Man K, Tong Y, Tsao SW. Berberine induces autophagic cell death and mitochondrial apoptosis in liver cancer cells: The cellular mechanism. J Cell Biochem. 2010;111:1426–1436. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang Y, Wang K, Gu C, Yu G, Zhao D, Mai W, Zhong Y, Liu S, Nie Y, Yang H. Berberine, a natural plant alkaloid, synergistically sensitizes human liver cancer cells to sorafenib. Oncol Rep. 2018;40:1525–1532. doi: 10.3892/or.2018.6552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li J, Liu F, Jiang S, Liu J, Chen X, Zhang S, Zhao H. Berberine hydrochloride inhibits cell proliferation and promotes apoptosis of non-small cell lung cancer via the suppression of the MMP2 and Bcl-2/Bax signaling pathways. Oncol Lett. 2018;15:7409–7414. doi: 10.3892/ol.2018.8249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu K, Yang Q, Mu Y, Zhou L, Liu Y, Zhou Q, He B. Berberine inhibits the proliferation of colon cancer cells by inactivating Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Int J Oncol. 2012;41:292–298. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2012.1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu X, Ji Q, Ye N, Sui H, Zhou L, Zhu H, Fan Z, Cai J, Li Q. Berberine inhibits invasion and metastasis of colorectal cancer cells via COX-2/PGE2 mediated JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0123478. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0123478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 15.Tuck AC, Tollervey D. A transcriptome-wide atlas of RNP composition reveals diverse classes of mRNAs and lncRNAs. Cell. 2013;154:996–1009. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.07.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gong C, Maquat LE. lncRNAs transactivate STAU1-mediated mRNA decay by duplexing with 3′UTRs via Alu elements. Nature. 2011;470:284–288. doi: 10.1038/nature09701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Engreitz JM, Pandya-Jones A, McDonel P, Shishkin A, Sirokman K, Surka C, Kadri S, Xing J, Goren A, Lander ES, et al. The Xist lncRNA exploits three-dimensional genome architecture to spread across the X chromosome. Science. 2013;341:1237973. doi: 10.1126/science.1237973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gayen S, Maclary E, Buttigieg E, Hinten M, Kalantry S. A primary role for the Tsix lncRNA in maintaining random X-chromosome inactivation. Cell Rep. 2015;11:1251–1265. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.04.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bai WL, Zhao SJ, Wang ZY, Zhu YB, Dang YL, Cong YY, Xue HL, Wang W, Deng L, Guo D, et al. lncRNAs in secondary hair follicle of cashmere goat: Identification, expression, and their regulatory network in Wnt signaling pathway. Anim Biotechnol. 2018;29:199–211. doi: 10.1080/10495398.2017.1356731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mullin NK, Mallipeddi NV, Hamburg-Shields E, Ibarra B, Khalil AM, Atit RP. Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway regulates specific lncRNAs that impact dermal fibroblasts and skin fibrosis. Front Genet. 2017;8:183. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2017.00183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bester AC, Lee JD, Chavez A, Lee YR, Nachmani D, Vora S, Victor J, Sauvageau M, Monteleone E, Rinn JL, et al. An integrated genome-wide CRISPRa approach to functionalize lncRNAs in drug resistance. Cell. 2018;173:649–664 e20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.03.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhu B, Xu M, Shi H, Gao X, Liang P. Genome-wide identification of lncRNAs associated with chlorantraniliprole resistance in diamondback moth Plutella xylostella (L.) BMC Genomics. 2017;18:380. doi: 10.1186/s12864-017-3748-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang L, Geng Z, Meng X, Meng F, Wang L. Screening for key lncRNAs in the progression of gallbladder cancer using bioinformatics analyses. Mol Med Rep. 2018;17:6449–6455. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2018.8655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li P, Xue WJ, Feng Y, Mao QS. Long non-coding RNA CASC2 suppresses the proliferation of gastric cancer cells by regulating the MAPK signaling pathway. Am J Transl Res. 2016;8:3522–3529. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yu Y, Liang S, Zhou Y, Li S, Li Y, Liao W. HNF1A/CASC2 regulates pancreatic cancer cell proliferation through PTEN/Akt signaling. J Cell Biochem. 2019;120:2816–2827. doi: 10.1002/jcb.26395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Durai R, Yang SY, Sales KM, Seifalian AM, Goldspink G, Winslet MC. Insulin-like growth factor binding protein-4 gene therapy increases apoptosis by altering Bcl-2 and Bax proteins and decreases angiogenesis in colorectal cancer. Int J Oncol. 2007;30:883–888. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jiang M, Milner J. Bcl-2 constitutively suppresses p53- dependent apoptosis in colorectal cancer cells. Genes Dev. 2003;17:832–837. doi: 10.1101/gad.252603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pretner E, Amri H, Li W, Brown R, Lin CS, Makariou E, Defeudis FV, Drieu K, Papadopoulos V. Cancer-related overexpression of the peripheral-type benzodiazepine receptor and cytostatic anticancer effects of Ginkgo biloba extract (EGb 761) Anticancer Res. 2006;26:9–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ming J, Xu S, Liu C, Liu X, Jia A, Ji Q. Effectiveness and safety of bifidobacteria and berberine in people with hyperglycemia: Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2018;19:72. doi: 10.1186/s13063-018-2438-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang Y, Sun J, Zhang YJ, Chai QY, Zhang K, Ma HL, Wu XK, Liu JP. The effect of berberine on insulin resistance in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: Detailed statistical analysis plan (SAP) for a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2016;17:512. doi: 10.1186/s13063-016-1633-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wink M. Quinolizidine alkaloids: Biochemistry, metabolism, and function in plants and cell suspension cultures. Planta Med. 1987;53:509–514. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-962797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang Q, Piao XL, Piao XS, Lu T, Wang D, Kim SW. Preventive effect of Coptis chinensis and berberine on intestinal injury in rats challenged with lipopolysaccharides. Food Chem Toxicol. 2011;49:61–69. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2010.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Piyanuch R, Sukhthankar M, Wandee G, Baek SJ. Berberine, a natural isoquinoline alkaloid, induces NAG-1 and ATF3 expression in human colorectal cancer cells. Cancer Lett. 2007;258:230–240. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2007.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu H, Huang C, Wu L, Wen B. Effect of evodiamine and berberine on miR-429 as an oncogene in human colorectal cancer. Onco Targets Ther. 2016;9:4121–4127. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S104729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chuang TY, Wu HL, Min J, Diamond M, Azziz R, Chen YH. Berberine regulates the protein expression of multiple tumorigenesis-related genes in hepatocellular carcinoma cell lines. Cancer Cell Int. 2017;17:59. doi: 10.1186/s12935-017-0429-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tukiainen T, Villani AC, Yen A, Rivas MA, Marshall JL, Satija R, Aguirre M, Gauthier L, Fleharty M, Kirby A, et al. Landscape of X chromosome inactivation across human tissues. Nature. 2017;550:244–248. doi: 10.1038/nature24265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sarfi M, Abbastabar M, Khalili E. Long noncoding RNAs biomarker-based cancer assessment. J Cell Physiol. 2019 Mar 5; doi: 10.1002/jcp.28417. (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Baldinu P, Cossu A, Manca A, Satta MP, Sini MC, Rozzo C, Dessole S, Cherchi P, Gianfrancesco F, Pintus A, et al. Identification of a novel candidate gene, CASC2, in a region of common allelic loss at chromosome 10q26 in human endometrial cancer. Hum Mutat. 2004;23:318–326. doi: 10.1002/humu.20015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gao Z, Wang H, Li H, Li M, Wang J, Zhang W, Liang X, Su D, Tang J. Long non-coding RNA CASC2 inhibits breast cancer cell growth and metastasis through the regulation of the miR-96-5p/SYVN1 pathway. Int J Oncol. 2018;53:2081–2090. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2018.4522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xue Z, Zhu X, Teng Y. Long non-coding RNA CASC2 inhibits progression and predicts favorable prognosis in epithelial ovarian cancer. Mol Med Rep. 2018;18:5173–5181. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2018.9550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fan JC, Zeng F, Le YG, Xin L. lncRNA CASC2 inhibited the viability and induced the apoptosis of hepatocellular carcinoma cells through regulating miR-24-3p. J Cell Biochem. 2018;119:6391–6397. doi: 10.1002/jcb.26479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ba Z, Gu L, Hao S, Wang X, Cheng Z, Nie G. Downregulation of lncRNA CASC2 facilitates osteosarcoma growth and invasion through miR-181a. Cell Prolif. 2018;51 doi: 10.1111/cpr.12409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Huang G, Wu X, Li S, Xu X, Zhu H, Chen X. The long noncoding RNA CASC2 functions as a competing endogenous RNA by sponging miR-18a in colorectal cancer. Sci Rep. 2016;6:26524. doi: 10.1038/srep26524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Johnson MI, Hamdy FC. Apoptosis regulating genes in prostate cancer (review) Oncol Rep. 1998;5:553–557. doi: 10.3892/or.5.3.553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Waters JS, Webb A, Cunningham D, Clarke PA, Raynaud F, di Stefano F, Cotter FE. Phase I clinical and pharmacokinetic study of bcl-2 antisense oligonucleotide therapy in patients with non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:1812–1823. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.9.1812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lessene G, Czabotar PE, Colman PM. BCL-2 family antagonists for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7:989–1000. doi: 10.1038/nrd2658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen Y, Zhou R, Yi Z, Li Y, Fu Y, Zhang Y, Li P, Li X, Pan Y. Porphyromonas gingivalis induced inflammatory responses and promoted apoptosis in lung epithelial cells infected with H1N1 via the Bcl-2/Bax/caspase-3 signaling pathway. Mol Med Rep. 2018;18:97–104. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2018.8983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yoo KH, Hennighausen L. EZH2 methyltransferase and H3K27 methylation in breast cancer. Int J Biol Sci. 2012;8:59–65. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.8.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.