Abstract

Aims:

The aim of this study was to analyze the thinking processes of anesthesia physicians at in Riyadh, Jeddah, and Dammam cities in Saudi Arabia.

Subjects and Methods:

This cross-sectional study was undertaken in the cities of Riyadh, Jeddah, and Dammam in Saudi Arabia. Using a previously published psychometric tool (the Rational and Experiential Inventory, REI-40), the survey was sent through email and social networks to anesthesia physicians working in the targeted hospitals. An initial survey was sent out, followed by a reminder and a second survey to nonrespondents. Analysis included descriptive statistics and Student's t-tests.

Results:

Most of the participants (69.2%) were males. At the time of the study, 35% of participants were consultants; 9.6% were associate consultants; 19.2% were registrars, fellows, or staff physicians; and 35.8% were senior residents. Anesthesia physicians’ mean “rational” score was 3.22 [standard deviation (SD) =0.49)] and their mean “experiential” score was 3.01 (SD = 0.31). According to Pearson's correlation, the difference of 0.21 between these two scores was not statistically significant (P = 0.35). Male anesthesia physicians tended more toward faster, logical thinking. Consultant anesthesia physicians had faster rational thinking than nonconsultant physicians (P = 0.01). Anesthesia physicians with more than 10 years in practice had faster rational thinking than physicians who had worked for fewer than 10 years (P = 0.001).

Conclusions:

This study evaluated anesthesia physicians’ general decision-making approaches. Despite the fact that both rational and experiential techniques are used in clinical decision-making, male consultants and physicians with more than 10 years’ experience and certified non-Saudi board anesthesiologists prefer rational decision-making style.

Keywords: Anesthesia, decision-making, experiential, rational

Introduction

In any healthcare field, decision-making is an important yet complex task. It relies on several mental processes, including perception, memory, and problem-solving skills.[1] Defects in any of these processes leading to errors can be seen in many areas of medicine, including the anesthesia department.[2] To avoid these errors, one has to understand how decision-making happens, and what flaws might occur during the process. Decision-making is a cognitive process, and cognition is complex and hierarchical.[3] It starts with simple skill-based tasks that require little cognitive input compared with coordination skills.[4] Second in line is rule-based decision-making, which includes following clinical guidelines and diagnostic algorithms and requires more cognitive effort; however, a clinician can rely greatly on these tools.[4] Finally, knowledge-based cognition, which is the highest in the hierarchy, involves clinical and diagnostic reasoning, both of which require a great deal of attentiveness to reach an appropriate endpoint in a given situation.[4]

Many studies have explored the nature of healthcare-related errors and their characteristics. In practice, vulnerability exists when a clinician is faced with a situation that requires integration between knowledge and real-life situations.[4,5] Diagnostic errors, a property of knowledge-based cognitive behavior, have also been found to be one of the most common types of errors.[6,7] Sometimes, other factors are involved in the analysis of how the diagnostic error occurred, such as having a lack of information, or false-negative results, but all these stem from cognitive error.[8] Other types of error exist in different clinical settings. For instance, errors in clinical reasoning predominate in resuscitation in trauma,[9] which can be attributed to a failure to consider all available information in the disposition of trauma patients.[9]

Several things lead to adverse outcomes. One way to understand how they occur is to understand the cognitive approaches to different situations. All cognitive processes fall under one of the two cognitive approaches: rational (conscious) and experiential (intuitive) thinking.[10] It has been postulated that individuals have an affinity to one of these approaches more than the other.[10] In a study of emergency medicine (EM) physicians registered with the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario, it was reported that EM physicians favor rational thinking.[10] However, there is no clear evidence for cognitive approaches used by anesthesia physicians in Saudi Arabia. Understanding this more fully could help prevent errors and enhance patient safety.

Therefore, the aim of this study was to analyze the thinking processes used by anesthesia physicians in the cities of Riyadh, Jeddah, and Dammam in Saudi Arabia.

Subjects and Methods

Study design and sampling technique

This cross-sectional study was undertaken in the cities of Riyadh, Jeddah, and Dammam, Saudi Arabia, to assess whether anesthesia physicians make rational or experiential decisions or not. A previously published psychometric tool was used: The Rational and Experiential Inventory (REI-40).[11] Members of the research team sent the survey to all available anesthesia physicians who were working in the targeted hospitals through emails. A total of 464 physicians were asked to complete the survey, with a 57% response rate. The electronic survey was sent via a link to a document, the first page of which contained an outline of the study objectives, the researchers’ contact information, and a clear statement to assure participants that their answers would remain confidential and their anonymity would be guaranteed in the final reports. The study was approved by the institutional review board of King Abdullah International Medical Research Centre, Ministry of National Guard – Health Affairs, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Study setting and subjects

This study targeted anesthesia physicians working at one of 19 hospitals in Riyadh (King Abdulaziz Medical City, Prince Sultan Military Medical City, Security Forces Hospital, King Fahad Medical City, King Saud Medical Complex, Prince Mohammed Bin Abdulaziz Hospital, King Khaled University Hospital, King Abdullah Bin Abdulaziz University Hospital, and King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Center), Jeddah (King Abdulaziz Medical City, King Fahad Armed Forces Hospital, King Abdulaziz University Hospital, King Fahad Hospital, and King Faisal Specialist Hospital), and Dammam (Imam Abdulrahman Al Faisal Hospital, King Fahad Military Medical Complex, Security Forces Hospital, King Fahad University Hospital, and King Fahad Specialist Hospital). Anesthesia physicians of all levels who are currently practicing anesthesia were included, from senior residents to consultants. Retired physicians or those for whom contact information could not be found were excluded.

Survey instrument

All physicians were asked to complete an electronic survey in three parts: the first part was an informed consent to assure all physicians participating in the study that their answers will remain confidential and their anonymity would be guaranteed. The second part captured demographic data (age, gender, number of years of practice, medical/postgraduate training, position, and institution), and the third part was the REI-40. The latter aimed to differentiate between two different modes of thinking: fast, intuitive, automatic thinking and slower, logical thinking. This tool has been previously validated in different populations, including emergency physicians,[10] paramedics,[12] and cardiologists.[13] Cronbach's alpha score for the tool ranged between 0.74 and 0.91, which demonstrated a high internal consistency and reliability. Participants were asked to indicate their agreement with 40 statements on a five-item Likert scale, ranging from 1= “definitely false” to 5= “definitely true”.

Data collection procedure

We mailed an anonymized REI-40 to a sample of anesthesia physicians in February 2018. The survey included a cover letter outlining the goal of the study, contact information, and assuring respondents of the confidentiality of their responses and their anonymity for the analysis and data reporting. The cover letter stated that consent was implied if the survey was returned. Three weeks after the mailing of the initial survey, we sent out reminders, and another 3 weeks later we sent a second copy of the questionnaire to a random sample (n = 200) of nonrespondents. We selected a random sample using an online random generator (http://www.random.org).

Data management and analysis

Data manipulation and analysis was performed using Microsoft Excel and SPSS Statistics for Windows (version 22.0. IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA). REI-40 was scored based on a coding manual provided by the lead investigator of the instrument, which provided reverse coding for some of the statements. Categorical variables were calculated using frequencies and percentages, whereas continuous variables were calculated as mean ± standard deviation (SD), and were presented as histograms. A 95% confidence interval was calculated for the mean difference between mean rational and experiential scores. The independent Student's t-test was used to assess the differences between means. All tests were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05.

Results

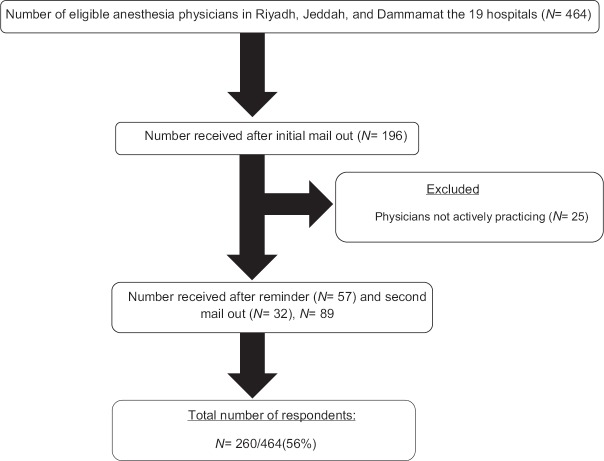

During the study period from February 2018 to June 2018, 260 anesthesia physicians responded to the survey [Figure 1]. All physicians were working in one of the targeted hospitals mentioned earlier. Most participants were males (n = 180, 69.2%). This was slightly higher than the overall ratio of male and female physicians working in Saudi Arabia (37:13, according to the last edition of the Ministry of Health Yearly Statistics Book, 2016). Among the participants, 122 were working in anesthesia departments in military hospitals (46.9%), 40 in Ministry of Health hospitals (15.4%), 53 in university hospitals (20.4%), and 45 in specialized hospitals (17.3%). At the time of the study, 35% of participants were consultants (n = 92), 9.6% were associate consultants (25), 19.2% were registrars, fellows, or staff physicians (50), and 35.8% were senior residents (93). Participants’ characteristics are described in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Flow of survey responses from 260 anesthesia physicians

Table 1.

Respondents’ demographic data (n=260)

| Variable | Category | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 180 | 69.2 |

| Female | 80 | 30.8 | |

| Number of years of practice | <5 years | 78 | 30 |

| 5-10 years | 61 | 23.5 | |

| >10-15 years | 43 | 16.5 | |

| >15 years | 78 | 30 | |

| Position | Consultant | 92 | 35.4 |

| Associate Consultant | 25 | 9.6 | |

| Registrar/Fellow/Staff physician | 50 | 19.2 | |

| Senior residents | 93 | 35.8 | |

| Hospital city | Riyadh hospitals | 124 | 47.7 |

| Jeddah hospitals | 100 | 38.5 | |

| Dammam hospitals | 36 | 13.8 | |

| Physician hospital type | Military hospitals | 122 | 46.9 |

| Ministry of Health hospitals | 40 | 15.4 | |

| University hospitals | 53 | 20.4 | |

| Specialist hospitals | 45 | 17.3 | |

| Medical/postgraduate education | Saudi Board | 132 | 54.6 |

| North American board | 33 | 127 | |

| European board | 46 | 17.7 | |

| Pakistan/India/Egypt/Syria/Arab board | 39 | 15 |

Participants’ mean rational score was 3.22 (SD = 0.49) and the mean experiential score was 3.01 (SD = 0.31). Pearson's correlation revealed that the difference of 0.21 between the two scores was not statistically significant (P = 0.23). The distribution of scores was normal, with some overlaps. Male anesthesia physicians tended toward faster logical thinking, with a mean rational score of 3.28 (SD = 0.52) versus 3.08 (SD = 0.40), whereas female physicians had a higher mean experiential score of 3.07 (SD = 0.29) versus 2.97 (SD = 0.32). Mean gender-related rational score was statistically significant (P = 0.003), as was the mean gender-related experiential score (P = 0.02). Consultant anesthesia physicians demonstrated statistically significantly faster rational thinking, with a mean rational score of 3.44 (SD = 0.59), than nonconsultant physicians, with a mean rational score of 3.10 (SD = 0.39; P = 0.01). Anesthesia physicians who had been in practice for more than 10 years had statistically significantly faster rational thinking than physicians who had been working for fewer than 10 years (P = 0.001). Table 2 summarizes the comparison of mean REI-40 scores for 260 respondents based on demographics. Our systematic search of the literature found three other studies reporting (REI-40) scores in other populations, only one of which used a population of clinicians (cardiologists from New Zealand).[14] This latter study used REI-40 to assess thinking styles of the cardiologists with regard to acute coronary syndrome guidelines. Refer Table 3 for comparisons of mean rational and experiential scores against those published for other populations. The greatest differentiation between the mean rational and experiential scores was found for cardiologists from New Zealand, followed by emergency physicians and college students.

Table 2.

Comparison of Mean Rational Experiential Inventory (REI-40) Scores for 260 Respondents Based on Demographics

| Demographics | Mean rational | SD | P | Mean experiential | SD | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 3.28 | 0.52 | 0.003* | 2.97 | 0.32 | 0.02* |

| Female | 3.08 | 0.40 | 3.07 | 0.29 | ||

| Physician position | ||||||

| Consultant | 3.44 | 0.59 | 0.01* | 2.98 | 0.37 | 0.45 |

| Non-consultant | 3.10 | 0.39 | 3.01 | 0.27 | ||

| Medical/postgraduate training | ||||||

| Saudi board | 3.14 | 0.43 | 0.083 | 3.01 | 0.27 | 0.99 |

| North American/European board | 3.25 | 0.535 | 3.01 | 0.35 | ||

| Number of years of practice | ||||||

| ≤10 years | 3.13 | 0.54 | 0.001* | 3.00 | 0.26 | 0.82 |

| >10 years | 3.33 | 0.43 | 3.01 | 0.36 |

*Statistical significance at P<0.05

Table 3.

Comparison of mean Rational Experiential Inventory (REI-40) scores for 260 anesthesia physicians with other study samples

| Sample | Mean rational score (SD) | Mean experiential score (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Ontario emergency physicians (n=434) | 3.93 (0.35) | 3.33 (0.49) |

| New Zealand cardiologists (n=74) 11 | 3.93 (0.37) | 3.05 (0.53) |

| American college students (n=399) 5 | 3.39 (0.61) | 3.52 (0.47) |

| Saudi anesthesia physicians (n=260) | 3.22 (0.49) | 3.01 (0.31) |

Discussion

This study examined the decision-making styles used by anesthesia physicians at 19 hospitals in Saudi Arabian cities of Riyadh, Jeddah, and Dammam to evaluate whether physicians’ clinical decisions are made using either rational or experiential processes. Our results show that a small difference exists between anesthesia physicians’ mean rational score of 3.22 (SD = 0.49) and mean experiential score of 3.01 (SD = 0.31); however, this difference was not statistically significant. The results suggest that anesthesia physicians tend to exploit both rational and experiential decision-making approaches equally.[15]

Our findings might be influenced by the fact that more men than women were surveyed in our study. However, they may also suggest a cultural difference, in which anesthesia physicians consider rational decision-making to be better than experiential decision-making. It is also possible that these conclusions came as a result of social desirability bias. Contrary to this view, Akinci et al. assert that intuitive thinking is as accurate and effective as analysis.[16] However, Engebretsen et al. posit that individuals tend to particularly make decisions more rationally when there are higher risks involved. Indeed, several scholars would contend this as being a familiar state of affairs when it comes to working in the emergency department.[17]

Compared with female anesthesia physicians, the male physicians in our study tended toward faster, logical thinking, that is, they reported being more analytical and intuitive with a mean male rational score = 3.28 (SD = 0.52) versus mean female rational score = 3.08 (SD = 0.40). However, female anesthesia physicians demonstrated more intuitive thinking, with a mean experiential score of 3.07 (SD = 0.29) versus the male mean experiential score of 2.97 (SD = 0.32). Consistent with previous studies,[13,17,18] these differences in gender-related scores were both statistically significant. Numerous surveys have validated the REI-40 tool with interestingly similar findings, suggesting that female participants are more likely to use experiential decision-making than their male counterparts.[10,16,19]

Significant relationship was found between the number of years of practice and decision-making approach: physicians with more than 10 years in practice tended toward faster, logical thinking, with a mean rational score of 3.33 (SD = 0.43), compared with physicians who had <10 years in practice with a mean experiential score of 3.13 (SD = 0.54). However, this finding is contrary to previous assertions that decision-making is often based on acquired knowledge, and that physicians use approaches that were more applicable earlier in their training, despite any discrepancies that may exist between the present state and earlier ones.[20] Our finding is consistent with the suggestion made by McLaughlin et al. that decision-making is a complicated process that widely differs among individuals based on social and context-specific influences.[21] Our results give crucial insight into how anesthesia physicians make decisions, which might be used for future research endeavors. It appears that experience accumulated over time is not a significant factor in the use of decision-making techniques.[22,23] The evidence generated from this study could be useful, particularly in terms of changing the management in the healthcare sector because scholars opine that those individuals who favor rational decision-making tend to be more receptive to evidence-based medicine and knowledge translation efforts.[24] Our results assert the need for decision-making support tools that are specifically designed to take both decision-making approaches into consideration. Male anesthesia physicians might react differently to different decision-making support tools than female physicians. Similarly, physicians in diverse practice settings and training backgrounds might also respond differently, thus it is critical to carefully refine such tools and their specificity before choosing the most appropriate tool.[25] The findings of this investigation suggest the significance of REI-40 to measure the perceived ability and enjoyment of cognitive and intuitive tasks and not actual decision-making behavior as a tool that can be utilized for self-assessment during clinical patient encounters whereby physicians are cognizant of the decision-making approaches they use with their inherent inadequacies. This is primarily because when a physician is cognizant of their general decision-making approach, they may be in better position to engage in metacognition, which can be described as “thinking concerning how to think”, to tackle any noticeable cognitive biases.[26,27]

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, is the voluntary way in which participants were recruited through personal contact by the research team. This approach involves a risk of self-selection bias, since physicians were contacted through their email addresses. Second, the sample of respondents was skewed toward male participants, which is not representative of the population of anesthesia physicians: according to the last edition of the Ministry of Health of Saudi Arabia Yearly Statistics Book 2016, the ratio of male-to-female physicians is 37:13, which was obtained for this study. We were able to determine that our sample has a similar demographic profile to that of Canadian emergency physicians (27.4% women and 72.6% men).[10] Third, our response rate was low but in keeping with typical response rates for physician surveys.[28] Fourth, our results represent the practicing anesthesiologists at only 19 centers rather than the whole anesthesiologists at the three cities. This limitation makes it difficult to generalize our data to the whole anesthesiologists’ population at these three cities. Fifth, it is possible that people who favored rational decision-making were also more likely to respond to a survey. Sixth, we also had a single physician comparator population in a different country, and in that study REI-40 was used to assess decision-making styles with respect to clinical guidelines in acute coronary syndrome rather than overall clinical practice.[14] It is possible that the similarities we found between cardiologists and anesthesia physicians are unique to these two groups and that marked differences may be noted when comparing these results with other specialties.

Conclusion

This study evaluated the general decision-making approaches used by anesthesia physicians. Despite both rational and experiential techniques being used in clinical decision-making, anesthesia physicians seem to prefer both decision-making styles. The results of this investigation have fundamental implications for evidence-based medicine and knowledge translation efforts. This study supports the implementation of strategies that are focused on reducing errors in decision-making. Both styles of decision-making are important in the clinical setting, and no approach is considered more exceptional than another. Future researchers should consider evaluating the decision-making approaches used by anesthesia physicians in broader terms, with a larger, more representative sample size, thus generating data that can support the successful design of decision-making support tools that are relevant to diverse groups of anesthesia physicians.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

To the lead investigators Pacini and Epstein for their permission to use the REI-40 tool; the original version is located in the initial article published in the Journal of Personality and Individual Differences (Pacini, R. and Epstein, S. 1999).

References

- 1.Gigerenzer G, Gaissmaier W. Heuristic decision making. Annu Rev Psychol. 2011;62:451–82. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-120709-145346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nair B, Gabel E, Hofer I, Schwid H, Cannesson M. Intraoperative clinical decision support for anesthesia: A narrative review of available system. Anesth Analg. 2017;124:603–17. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000001636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rasmussen J, Jensen A. Mental procedures in real-life tasks: A case study of electronic trouble shooting. Ergonomics. 1974;17:293–307. doi: 10.1080/00140137408931355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Croskerry P. Cognitive forcing strategies in clinical decision making. Ann Emerg Med. 2003;41:110–20. doi: 10.1067/mem.2003.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brennan TA, Leape LL, Laird NM, Hebert L, Localio AR, Lawthers AG, et al. Incidence of adverse events and negligence in hospitalized patients. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:370–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199102073240604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Glick TH, Workman TP, Gaufberg SV. Suspected conversion disorder: Foreseeable risks and avoidable errors. Acad Emerg Med. 2000;7:1272–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2000.tb00474.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Famularo G, Salvini P, Terranova A, Gerace C. Clinical errors in emergency medicine: Experience at the emergency department of an Italian teaching hospital. Acad Emerg Med. 2000;7:1278–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2000.tb00475.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kuhn GJ. Diagnostic errors. Acad Emerg Med. 2002;9:740–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2002.tb02155.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clarke JR, Spejewski B, Gertner AS, Webber BL, Hayward CZ, Santora TA, et al. An objective analysis of process errors in trauma resuscitations. Acad Emerg Med. 2000;7:1303–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2000.tb00480.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Calder LA, Forster AJ, Stiell IG, Carr LK, Brehaut JC, Perry JJ, et al. Experiential and rational decision making: A survey to determine how emergency physicians make clinical decisions. Emerg Med J. 2012;29:811–6. doi: 10.1136/emermed-2011-200468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pacini R, Epstein S. The relation of rational and experiential information processing styles to personality, basic beliefs, and the ratio-bias phenomenon. Pers Individ Dif. 1999;76:972–87. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.76.6.972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jensen JL, Bienkowski A, Travers AH, Calder LA, Walker M, Tavares W, et al. A survey to determine decision-making styles of working paramedics and student paramedics. CJEM. 2016;18:213–22. doi: 10.1017/cem.2015.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sladek RM, Bond MJ, Phillips PA. Age and gender differences in preferences for rational and experiential thinking. Pers Individ Dif. 2010;49:907–11. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sladek RM, Bond MJ, Huynh LT, Chew DPB, Philips PA. Thinking styles and doctors’ knowledge and behaviors relating to acute coronary syndromes guidelines. Implement Sci. 2008;3:23. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-3-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Croskerry P, Cosby K, Graber ML, Singh H. Diagnosis: Interpreting the Shadows. 1st ed. London: Taylor & Francis Ltd; 2017. Individual Variability in Clinical Decision Making and Diagnosis. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Akinci C, Sadler-Smith E. Assessing individual differences in experiential (intuitive) and rational (analytical) cognitive styles. Int J Sel Assess. 2013;21:211–21. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Engebretsen E, Heggen K, Wieringa S, Greenhalgh T. Uncertainty and objectivity in clinical decision making: A clinical case in emergency medicine. Med Heal Care Philos. 2016;19:595–603. doi: 10.1007/s11019-016-9714-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Djulbegovic B, Beckstead JW, Elqayam S, Reljic T, Hozo I, Kumar A, et al. Evaluation of physicians’ cognitive styles. Med Decis Mak. 2014;34:627–37. doi: 10.1177/0272989X14525855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Phillips WJ, Fletcher JM, Marks ADG, Hine DW. Thinking styles and decision making: A meta-analysis. Psychol Bull. 2016;142:260–90. doi: 10.1037/bul0000027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iannello P, Perucca V, Riva S, Antonietti A, Pravettoni G. What do physicians believe about the way decisions are made? A pilot study on metacognitive knowledge in the medical context. Eur J Psychol. 2015;11:691–706. doi: 10.5964/ejop.v11i4.979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McLaughlin JE, Cox WC, Williams CR, Shepherd G. Rational and experiential decision-making preferences of third-year student pharmacists. Am J Pharm Educ. 2014;78:120. doi: 10.5688/ajpe786120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Riva S, Monti M, Iannello P, Pravettoni G, Schulz PJ, Antonietti A. A preliminary mixed-method investigation of trust and hidden signals in medical consultations. PLoS One. 2014;9:e90941. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cipresso P, Villani D, Repetto C, Bosone L, Balgera A, Mauri M, et al. Computational psychometrics in communication and implications in decision making. Comput Math Methods Med. 2015;2015:1–10. doi: 10.1155/2015/985032. doi: 10.1155/2015/985032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nilsen P, Neher M, Ellström P-E, Gardner B. Implementation of evidence-based practice from a learning perspective. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2017;14:192–9. doi: 10.1111/wvn.12212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vannucci A, Kras JF. Decision making, situation awareness, and communication skills in the operating room. Int Anesthesiol Clin. 2013;51:105–27. doi: 10.1097/AIA.0b013e31827d6470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Norman GR, Monteiro SD, Sherbino J, Ilgen JS, Schmidt HG, Mamede S. The causes of errors in clinical reasoning. Acad Med. 2017;92:23–30. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lambe KA, O’Reilly G, Kelly BD, Curristan S. Dual-process cognitive interventions to enhance diagnostic reasoning: A systematic review. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016;25:808–20. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Asch DA, Jedrziewski MK, Christakis NA. Response rates to mail surveys published in medical journals. J Clin Epidemiol. 1997;50:1129:e36. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(97)00126-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]