Abstract

Cell division cycle associated 7 like (CDCA7L) belongs to the JPO protein family, recently identified as a target gene of c-Myc and is frequently dysregulated in multiple cancers. However, to the best of our knowledge, no studies to date have been carried out to investigate the functions of CDCA7L in glioma. Thus, in this study, the expression level of CDCA7L and its association with the prognosis in glioma were detected through the TCGA database. The mRNA expression levels of CDCA7L in glioblastoma (GBM) tissues and normal brain tissues were detected by RT-qPCR and western blot analysis. To explore the role of CDCA7L in glioma, CDCA7L siRNA was constructed and transfected into U87 glioma cells. The expression levels of CDCA7L and cyclin D1 (CCND1) in glioma U87 cells following transfection with CDCA7L siRNA were measured by RT-qPCR and western blot analysis. CCK-8, colony formation, EdU and Transwell assays were used to measure the effects of CDCA7L on U87 cell proliferation, and flow cytometry was used to monitor the changes in the cell cycle following transfection with CDCA7L siRNA. Xenograft tumors were examined in vivo for the carcinogenic effects, as well as the mechanisms and prognostic value of CDCA7L in glioma tissues. The results revealed that CDCA7L was highly expressed in human GBM tissues, and a high expression of CDCA7L was associated with a poor prognosis of glioma patients through the TCGA database. We demonstrated that CDCA7L was highly expressed in human GBM tissues and 3 glioma cell lines. The downregulation CDCA7L expression significantly inhibited the proliferation and colony formation ability of U87 cells by blocking cell cycle progression in the G0/G1 phase. In addition, we found that the mRNA and protein levels of CCND1 were markedly decreased following transfection with CDCA7L siRNA compared with NC siRNA in vitro. The downregulation CDCA7L expression reduced the number of invading cells. Consistent with the results of the in vitro assays, the xenograft assay, immunohistochemistry (IHC) assay and western blot analysis demonstrated that, in response to CDCA7L inhibition, tumor growth was inhibited, Ki-67 and CCND1 expression levels were decreased in vivo. On the whole, the results of the current study indicate that CDCA7L is highly expressed in human glioma tissues and that a high CDCA7L expression predicts a poor prognosis of glioma patients. CDCA7L promotes glioma U87 cell growth through CCND1.

Keywords: CDCA7L, CCND1, glioblastoma, proliferation, cell cycle, apoptosis

Introduction

Glioma is considered the most common malignant tumor affecting the central nervous system in adults. Glioma is associated with a poor prognosis, an aggressive behavior, rapid progression and frequent recurrence (1). In particular, the median survival time of patients with glioblastoma (GBM) is usually <1 year (2). Nowadays, there are various treatment strategies for glioma, such as chemotherapy, radiotherapy and surgery. Nonetheless, the prognosis of patients with glioma remains (3). Thus, the identification of the underlying molecular mechanisms of the initiation and progression of glioma is of utmost importance.

It has been shown that one of the targets of c-Myc is cell division cycle-associated 7-like protein (CDCA7L). CDCA7L can interact with c-Myc (4). Generally, the activation of the c-Myc oncogene is considered critical for the pathogenesis of massive human malignant tumors, which include glioma (4–7). It has been reported that CDCA7L is dysregulated in a number of cancer types (4,8). This is of utmost importance for the determination of the epigenetic mechanisms of the development and progression of cancer. Furthermore, it is also considered that CDCA7L plays a significant role in cancer and therefore, in tumor progression. It may also be a potential therapeutic target.

It has been shown in the existing research that human glioma tissues highly express CDCA7L (9). However, to the best of our knowledge, the explicit mechanism of CDCA7L in glioma remains largely unknown. In this study, we aimed to explore the role of CDCA7L in glioma progression both in vivo and in vitro and to elucidate the underlying mechanisms.

Materials and methods

OncoLnc and Oncomine databases

The OncoLnc database (http://www.oncolnc.org/) was used to obtain prognostic data of 152 patients with GBM and 510 patients with low-grade glioma (LGG), while the Oncomine database was used to obtain the CDCA7L expression data of 80 patients with GBM. Generally, each case of CDCA7l expression was obtained based on the normalized results of RSEM RNASeqV2 for all types of cancer, among which, the overall survival (OS) has been calculated in the days beginning from the date of diagnosis to death. At the same time, the mRNA expression level of CDCA7L was identified as either decreased (<0 in z-scores) or increased (>0 in z-scores). This was applied to compare the survival of the patients.

Cell lines and cell culture

The Shanghai Cell Bank provided the U251 (cat. no. TCHu58), A172 (cat. no. TCHu171), human glioma U87 (cat. no. TCHu138; glioblastoma cells of unknown origin). ScienCel provided the normal human astrocytes (HEB, cat. no. 1800). Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used to cultivate these cells; the medium was also supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and the cells were cultured at 37°C with 5% CO2.

Patients and tissue samples

Patients with GBM (n=22) undergoing an initial glioma resection surgery at the First Affiliated Hospital of Xinxiang Medical University between 2014 and 2017 were enrolled in this study. Moreover, 6 normal white matter brain tissues (NBTs) were obtained from temporal lobectomy from patients with temporal lobe epilepsy. Informed consent was obtained from each patient taking part in this research. The Medical Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Xinxiang Medical University approved the use of the samples for this research. Prior to the resection, each patient was treatment naive.

U87 glioma cell transfection

Shanghai Genechem Biotechnology Co., Ltd. provided the negative control siRNA (NC siRNA) and GFP-expressing CDCA7L small interfering RNA (siRNA). The siRNA sequences used in this study were: CDCA7L siRNA, 5′-GCCAGAUUUCUUCCCAGUAdTdT-3′ (sense) and 5′-UACUGGGAAGAAAUCUGGCdTdT-3′ (antisense); and NC siRNA, 5′-UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGUdTdT-3′ (sense); 5′-ACGUGACACGUUCGGAGAAdTdT-3′ (antisense). In total 5×105 U87 cells at 60% confluence, were plated in each well of a 6-well plate. The cells were then transfected NC siRNA and CDCA7L siRNA using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). After being transfected for a day, the cells were observed under a fluorescence microscope (Leica Microsystems, GmbH). The CDCA7L siRNA transfection efficiency was examined by western blot analysis and reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR).

RT-qPCR

RNA was extracted from the glioma tissues and cell lines using TRIzol based on the protocol of the manufacturer (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). RT-qPCR was carried out to detect the cyclin D1 (CCND1) and CDCA7L expression levels using the one-step RT-PCR kit (Takara Bio, Inc.) based on the protocol of the manufacturer. Genechem Co. Ltd. provided the CDCA7L. β-actin was used as an internal control. The primer sequences were as follows: CDCA7L forward, 5′-TTGGCGACTCGCTACCAGAT-3′ and reverse, 5′-AATGAAAGCGCACATCCTGC-3′; CCND1 forward, 5′-CAGATCATCCGCAAACACGC-3′ and reverse, 5′-AAGTTGTTGGGGCTCCTCAG-3′; and β-actin forward, 5′-AGAGCCTCGCCTTTGCCGATCC-3′, and reverse, 5′-CTGGGCCTCGTCGCCCACATA-3′. The reaction conditions were as follows: 95°C for 30 sec, followed by 40 amplification cycles of 95°C for 5 sec and 60°C for 34 sec. The 2−ΔΔCq method (10) was used to quantify the mRNA expression levels of CDCA7L and CCND1. The β-actin mRNA expression level was used to normalize the mRNA expression levels.

Western blot analysis

At 72 h following transfection, the cells were harvested while the lysates of the cell were generated using RIPA lysis buffer for approximately 30 min at 4°C. The BCA Protein Assay kit (Pierce; Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used to determine the protein concentration. Subsequently, 12.5% SDS-PAGE was used to separate the total protein evenly (50 µg/lane) followed by transfer to PVDF membranes. Membranes were blocked with 5% skim milk powder in TBS-T for 2 h at room temperature and then incubated with primary antibodies at 4°C overnight. The primary antibodies were obtained from Abcam [anti-β-actin antibody (diluted at 1/5,000, ab6276), anti-CCND1 (diluted at 1/200, ab16663) and rabbit anti-CDCA7L (diluted at 1/2,000, ab70637)]. The secondary antibody used was horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:10,000, ab6721; Abcam) at room temperature for 1 h. β-actin was used as an internal control for the normalization of the protein expression levels. The proteins bands were visualized using an Enhanced Chemiluminescence Plus Western Blotting Detection system (GE Healthcare). Band intensities were quantified by densitometry using ImageJ Software version 1.6 (National Institutes of Health).

Cell viability analysis

After 48 h following transfection with NC siRNA or CDCA7L, the U87 cells at the exponential phase were seeded into 96-well plates at a density of 4×103 cells/well. Cell proliferation was examined using the Cell-Counting kit-8 (CCK-8) based on the instructions of the manufacturer (Beijing TransGen Biotech Co., Ltd.).

Cell proliferation assay

The U87 glioma cells, which had been plated into 6-well cell culture plates were then counted; the corresponding density was 300 cells/well for colony formation. The cells were then incubated for 20 days under 37°C. Subsequently, 4% paraformaldehyde was used to fix the visible colonies. Subsequently, 0.1% crystal violet was used to stain the cells for a further 30 min at room temperature. The colonies were viewed and counted under a light microscope (Nikon Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) with at least five fields randomly. The number of colonies was calculated as the colony-forming efficiency.

Following transfection with NC siRNA or CDCA7L siRNA, the glioma U87 cells were counted by cell counting instrument (Countess, Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and then seeded into 24-well plates at a density of 1×104 cells/well. After incubation at 37°C for 48 h, the cells were exposed to 50 µM 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EdU; Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 2.5 h. The reaction cocktail (EdU Imaging Kits, Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific), Inc. was used to stain at room temperature for 30 min and permeabilize the U87 cell nuclei. The samples were then visualized under a fluorescence microscope (Leica Microsystems, GmbH).

Flow cytometry

The U87 cells were infected with CDCA7L siRNA or NC siRNA and incubated at 37°C. The transfected glioma cells were then harvested, washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and fixed with 75% ice-cold ethanol. Subsequently, the cells were examined using the Cell Cycle Staining kit (Multi Sciences) and incubated for 30 min in dark accord 37°C according to the manufacturer's instructions. In addition, to detect the effect of CDCA7L siRNA on cell apoptosis, the U87 cells were harvested by trypsinization and incubated with FITC-conjugated Annexin V and PI following the manufacturer's instructions (Keygen Biotech). Finally, the cells were analyzed by flow cytometry and BD CellQuest™ software version 5.1 (BD Biosciences).

Transwell invasion assay

The invasion assay was performed using a Transwell chamber (Millipore). In brief, the transfected cells were seeded in the upper chamber containing the serum-free medium (1×105 cells), while the lower chamber contained DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and coated with Matrigel (20%; Corning Incorporated). Then cells were incubated for 6 h at 37°C. Subsequently, the cells were fixed with pre-cooled 4% methanol for 5 min at room temperature and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) for 20 min at room temperature following transfection with CDCA7L siRNA or NC siRNA, and the invading cells were photographed under a light microscope (Leica Microsystems, GmbH); the number of cells was counted.

Glioma xenografts in animals and immunohistochemistry (IHC)

The animal experiments were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Xinxiang Medical and were carried out in strict accordance with the experimental protocol. Specifically, the glioma U87 cells were transfected with CDCA7L siRNA or NC siRNA, and a total of 12 male BALB/c-A nude mice (4 weeks old) were randomly divided into the CDCA7L downregulated group or the control group. The mice were kept in an air laminar flow chamber with a temperature of 26–28°C and a humidity of 40–60%. Food and water were sterilized under high pressure and were freely available. After being anesthetized with chloral hydrate (350 mg/kg; intraperitoneally), a total of 4×106 transfected U87 cells were implanted into each nude mouse to detect the glioma xenograft formation. The survival time of the mice was observed until 1 month, and intracranial tumor formation was assessed by bioluminescence imaging. At the end of the experiment, the mice were exposed to CO2 to achieve euthanasia [CO2 (10 l/min); chamber volume: 0.15 m3 (height × width × length, 60×50×50 cm) and the brain glioma tissue sections were incubated with anti-Ki-67 (ab16667; Abcam). Subsequently, 3 fields were selected to examine the percentage of positive tumors and staining intensities, and the CCND1 expression levels in the glioma xenografts were detected through western blot analysis.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analyses applied the SPSS 21.0 statistical software package. All data are expressed as the means ± standard deviations (SD), and all experiments were repeated 3 times. Differences between 2 groups were analyzed using a Student's t-test (two-tailed). Furthermore, Kaplan-Meier analysis was used to assess the survival rate of both glioma patients and mice, while the log-rank test was used to assess the statistical significance. A P-value <0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

CDCA7L is overexpressed in human glioma tissues and predicts a poor prognosis of patients with glioma

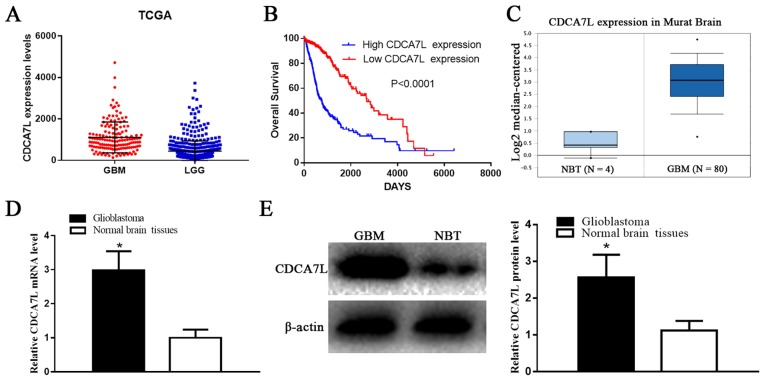

According to the OncoLnc database dataset, the CDCA7L expression levels were markedly higher in the GBM tissues compared with those in the LGG tissues (P<0.001) (Fig. 1A). Moreover, the clinical information and gene expression profiles of the 510 LGG and 152 GBM patients were matched in the current study, which further determined whether CDCA7L expression levels were associated with patient survival. Additionally, both Kaplan-Maier analysis and log-rank comparisons were performed. The results presented in Fig. 1B demonstrated that a higher CDCA7L expression was associated with a shorter overall survival (OS) of the glioma patients (P<0.0001). In addition, according to CDCA7L expression in ‘Murat Brain’ (a glioma-related dataset in the Oncomine database), the CDCA7L expression levels were markedly higher in the GBM tissues compared to those in NBTs (P<0.0001) (Fig. 1C). These findings indicate that CDCA7L may play a vital role in glioma development, and may thus potentially serve as a prognostic marker.

Figure 1.

CDCA7L expression profiles and prognostic value in glioma. (A) CDCA7L expression levels were evidently higher in GBM tissues compared with those in LGG tissues in the OncoLnc dataset. (B) Higher CDCA7L expression is associated with a shorter OS of glioma patients. (C) CDCA7L expression levels were markedly higher in GBM tissues relative to those in NBTs from the Oncomine dataset. (D and E) CDCA7L mRNA and protein expression levels in glioma samples and NBTs. *P<0.05 indicates statistical significance compared with the NBTs group. CDCA7L, cell division cycle-associated 7 like; GBM, glioblastoma; LGG, low-grade glioma; NBTs, normal brain tissues; OS, overall survival.

Subsequently, the CDCA7L expression levels in 6 NBTs and 22 GBM samples were detected by RT-qPCR assay and western blot analysis, respectively. The results indicated that the CDCA7L mRNA (Fig. 1D) levels in the GBM tissues were notably higher than those in the NBTs, and the average CDCA7L protein expression level in the GBM tissues was higher than that in the NBTs (P<0.01; Fig. 1E).

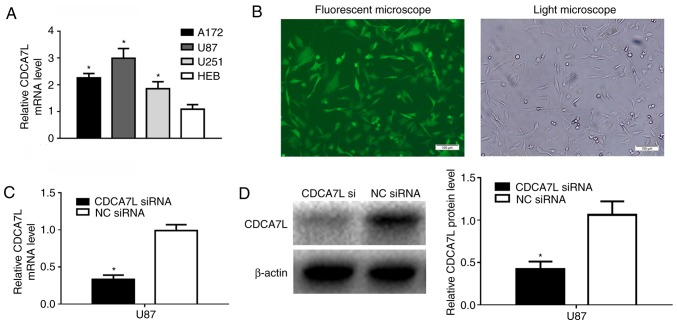

CDCA7L expression is inhibited by CDCA7L siRNA in U87 human glioma cells

The CDCA7L expression levels in the U87, A172 and U251 glioma cell lines were detected by RT-qPCR, and the results revealed that CDCA7L mRNA epxression in the 3 glioma cell lines was higher than that in the HEB cells (Fig. 2A). To explore the role of CDCA7L in glioma, GFP-expressing CDCA7L siRNA and NC siRNA were transfected into human glioma U87 cells, and >85% of the cells exhibited positive green fluorescence following transfection (Fig. 2B), and the knockdown efficiency was analyzed by RT-qPCR and western blot analysis. Following 72 h of transfection, the CDCA7L mRNA (Fig. 2C) and protein (Fig. 2D) expression levels in the U87 cells of CDCA7L siRNA group were markedly lower than those in the NC siRNA group.

Figure 2.

CDCA7L siRNA was constructed and transfected into the glioma U87 cells. (A) RT-qPCR was performed to detect the CDCA7L mRNA expression levels in glioma cell lines. (B) Infection efficiency was examined by fluorescence microscopy at 72 h following infection. Scale bar, 100 µm. (C and D) The knockdown efficiency of CDCA7L siRNA was assessed by (C) RT-qPCR assay and (D) western blot analysis. *P<0.05 indicates statistical significance compared with the control group. CDCA7L, cell division cycle-associated 7 like; NC, negative control.

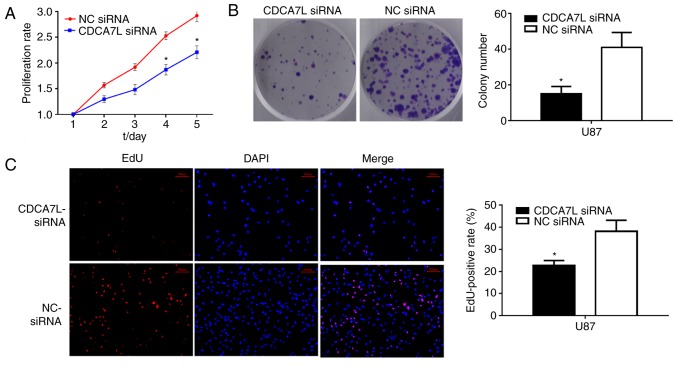

Downregulation of CDCA7L expression markedly suppresses the growth of U87 glioma cells

To examine the effects of CDCA7L on the growth of glioma cells, CCK-8 and colony formation assays were performed after the glioma U87 cells were transfected with CDCA7L siRNA or NC siRNA. As shown in Fig. 3, the knockdown of CDCA7L expression markedly reduced the proliferation potential and evidently suppressed the growth of U87 cells transfected with CDCA7L siRNA compared with those in the NC siRNA group. Moreover, the growth of the CDCA7L siRNA-transfected cells was also notably reduced in vitro on days 4 and 5 (Fig. 3A), and colony formation was also evidently reduced following the silencing of CDCA7L (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3.

Downregulation of CDCA7L inhibits glioma cell proliferation and colony formation. (A) CCK-8 assay showing that the inhibition of CDCA7L decreased the proliferation of U87 glioma cells. (B) Colony formation was also significantly reduced following CDCA7L downregulation. (C) EdU assays indicating that the downregulation of CDCA7L inhibited the proliferation of U87 glioma cells. Scale bar, 100 µm. *P<0.05 indicates statistical significance compared with the NC siRNA group. CDCA7L, cell division cycle-associated 7 like; NC, negative control.

Furthermore, the effects of CDCA7L on cell proliferation following the downregulation of CDCA7L were evaluated through an EdU cell-image assay, and the results were consistent with those of the CCK-8 and colony formation assays, indicating that the EdU-positive rates of U87 cells were lower in the CDCA7L siRNA group compared with those in the NC siRNA group and that the number of EdU-positive cells was decreased by approximately 16.6% (Fig. 3C). Thus, on the whole, these data indicate that the knockdown of CDCA7L effectively prevents the development of U87 glioma cells.

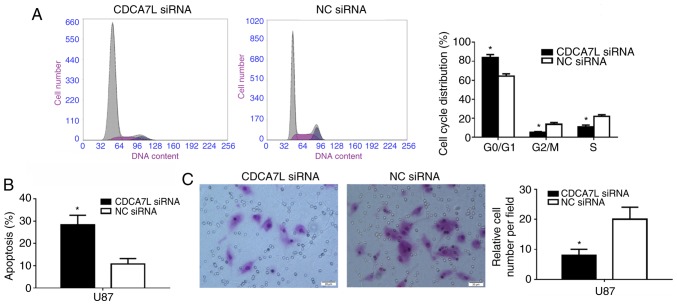

Inhibition of CDCA7L induces cell arrest at the G0/G1 phase, and the apoptosis and invasion of U87 glioma cells

The cell cycle distribution of the U87 cells following the downregulation of CDCA7L was subsequently examined since proliferation is directly connected to cell cycle distribution, and the cell cycle phases of the U87 cells were measured by flow cytometry. As shown in Fig. 4A, the number of cells entering the G0/G1 phase was increased by 19.30% (P<0.01) and that of cells entering the S phase was decreased by 10.98% in the absence of CDCA7L (P<0.01).

Figure 4.

CDCA7L modulates the U87 glioma cell cycle, apoptosis and invasion. (A and B) Flow cytometric analysis of (A) cell cycle distribution and (B) apoptosis of U87 cells transfected with CDCA7L siRNA or NC siRNA. (C) Downregulation of CDCA7L expression reduced the number of invading cells. Scale bar, 20 µm. *P<0.05 indicates statistical significance compared with the NC siRNA group. CDCA7L, cell division cycle-associated 7 like; NC, negative control.

Moreover, the effects of CDCA7L on U87 glioma cell apoptosis were also examined. The results suggested that, the percentage of apoptotic U87 cells in the CDCA7L siRNA group was markedly higher than that of those in the NC siRNA group (P<0.01; Fig. 4B). These results indicated that the knockdown of CDCA7L expression evidently inhibited the proliferation of U87 cells by increasing the percentage of cells at the G0/G1 phase, while decreasing the percentages of cells at the S and G2/M phases, and inducing apoptosis.

Following transfection with CDCA7L siRNA or NC siRNA, the invasive abilities of the transfected cells were compared. As shown in Fig. 4C, the downregulation of CDCA7L expression reduced the number of invading cells by approximately 60% compared with the NC siRNA group, as shown by Transwell assays.

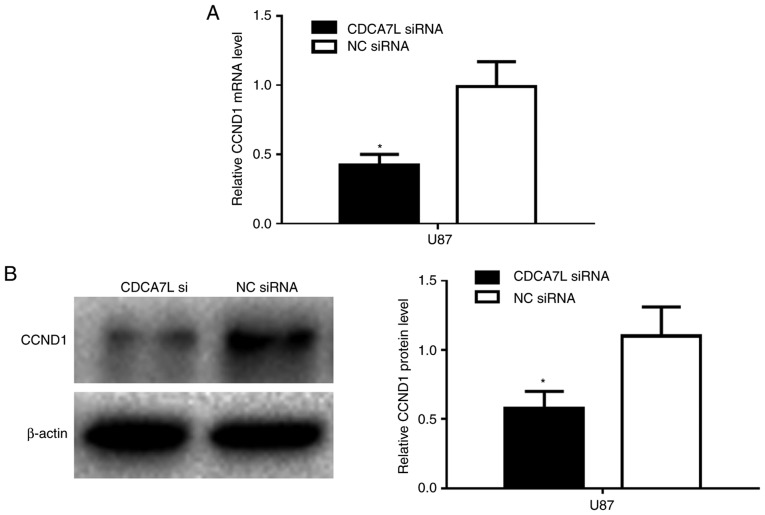

Downregulation of CDCA7L inhibits cell proliferation by targeting CCND1

Furthermore, to investigate the target of CDCA7L in GBM cells in vitro, the U87 cells were transfected with CDCA7L siRNA or NC siRNA, and the CCND1 mRNA and protein expression levels were determined by RT-qPCR and western blot analysis, respectively. The results revealed that the CCND1 mRNA expression level was markedly reduced following transfection with CDCA7L siRNA compared with NC siRNA (Fig. 5A). In addition, the CCND1 protein expression level was markedly lower in the CDCA7L siRNA-transfected group (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5.

CDCA7L modulates the CCND1 expression levels. (A) The mRNA and (B) the protein expression levels of CCND1 detected by RT-qPCR and western blot analysis, respectively following transfection with CDCA7L siRNA or NC siRNA. *P<0.05 indicates statistical significance compared with the NC siRNA group. CDCA7L, cell division cycle-associated 7 like; NC, negative control; CCND1, cyclin D1.

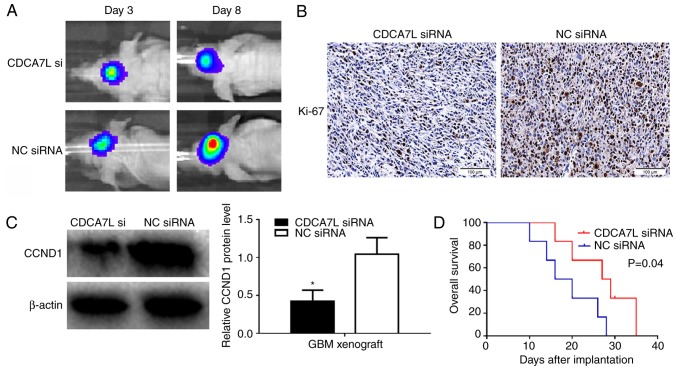

Downregulation of CDCA7L suppresses the glioma xenograft growth in vivo

To assess whether CDCA7L downregulation can could suppress glioma growth in vivo, U87 human glioma cells transfected with CDCA7L siRNA or NC siRNA were injected into the brains of nude mice to form intracranial xenografts. Bioluminescence imaging revealed that tumor growth in the CDCA7L siRNA group (maximum diameter, 0.5 cm) was inhibited compared with that in NC siRNA group (maximum diameter, 1.0 cm) (Fig. 6A). Moreover, IHC experiments were performed to examine the Ki-67 levels, which are commonly used to detect tumor proliferation. The results suggested that the Ki-67 expression levels were markedly reduced in the CDCA7L siRNA group (Fig. 6B). In addition, western blot analysis also revealed the downregulation of CCND1 expression in the CDCA7L siRNA group, which was consistent with the results in vitro (Fig. 6C). Furthermore, to analyze survival in the different treatment groups, a Kaplan-Meier survival curve was plotted, which revealed that the survival of the mice in the CDCA7L siRNA groups was evidently prolonged compared with that of mice in the NC siRNA groups (Fig. 6D). Thus, these data suggested that the knockdown of CDCA7L expression suppresses glioma growth by downregulating CCND1 expression in vivo.

Figure 6.

Downregulation of CDCA7L inhibits glioma cell growth in vivo. (A) The images of mice implanted with intracranial tumors formed by U87 on days 3 and 8. (B) Ki-67 in tumors derived from U87 cells following transfection with CDCA7L siRNA or NC siRNA examined by immunohistochemistry. Scale bar, 100 µm. (C) Downregulation CDCA7L expression reduced the CCND1 expression level in vivo shown by western blot analysis. *P<0.05 indicates statistical significance compared with the NC siRNA group. (D) Kaplan-Meier curves plotted to measure the overall survival in the 2 ×enograft groups. CDCA7L, cell division cycle-associated 7 like; NC, negative control.

Discussion

As a transcriptional regulator, c-Myc can promote tumor development by regulating a variety of target genes; however, the biological roles of these target genes in the development of GBM remains unclear. CDCA7L belongs to the JPO protein family, which has been recently identified as a target gene of c-Myc (11,12). Additionally, CDCA7L can also complement the c-Myc transformation-defective mutant W135E and potentiate the Myc-mediated transformation (13).

A high CDCA7L expression has been reported in several cancer types, and CDCA7L may be critical for cancer progression, and may serve as a potential treatment target for cancer. Moreover, CDCA7L has been shown to induce colony formation and contribute to the MYC-mediated transformation of medulloblastoma cells, suggesting that CDCA7L plays a critical role in the development of medulloblastoma (4). Tian et al (8) reported that CDCA7L activated the extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 signaling pathway and controlled the cell cycle, thereby promoting the progression of hepatic carcinoma.

In the current study, the public expression profiles and clinical data of glioma patients were collected from the OncoLnc and Oncomine databases. The analysis of the databases suggested that the CDCA7L expression level was markedly upregulated in GBM compared with that in LGG tissues, and a high CDCA7L expression was associated with a poor prognosis of glioma patients. Secondly, CDCA7L was proven to be highly expressed in GBM tissues compared with that in NBTs. Thirdly, to explore the role of CDCA7L in glioma, CDCA7L siRNA was constructed and transfected into U87 glioma cells, which downregulated CDCA7L expression in the U87 cells in vitro. Taken together, the results of this study demonstrated that the downregulation of CDCA7L expression evidently suppressed the proliferation of U87 cells through increasing the percentage of cells at the G0/G1 phase, while decreasing the percentage of cells in the S and G2/M phases, and inducing apoptosis. In addition, the inhibition of CDCA7L expression markedly suppressed the invasive ability of U87 glioma cells.

As a target gene of c-Myc, CDCA7L can interact with c-Myc, and c-Myc has been found in multiple studies to be closely related to cyclin D1 in a variety of tumors (14–16). Moreover, previous studies have proven that CDCA7L can regulate the cell cycle, and that CCND1 may be an important target gene of CDCA7L in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) (8). However, the mechanisms of action of CDCA7L in glioma remains to be further elucidated. It was found in the current study that the mRNA and protein expression levels of CCND1 were markedly downregulated following transfection with CDCA7L siRNA compared with NC siRNA in vitro. Consistent with the results of the assays in vitro, the xenograft assay, IHC assay and western blot analysis also demonstrated that tumor growth was inhibited in response to CDCA7L inhibition, and that the Ki-67 and CCND1 expression levels were decreased in vivo. Moreover, recent studies (17–19) have suggested that CCND1 is a proto-oncogene located on human chromosome 11q13, which is highly expressed in multiple types of cancer, such as glioma, colorectal cancer (CRC) and ovarian cancer. Typically, CCND1 can encode cyclin D1, while the latter can bind and activate CDK6 and CDK4, which can lead to the phosphorylation of pRb, thus driving cell cycle progression from the G1 phase to the S phase (20). In addition, CCND1 overexpression can also result in a number of potentially oncogenic effects, which have been shown to be associated with poor patient outcomes (21).

Therefore, these results suggest that CDCA7L promotes the growth of U87 glioma cells through targeting CCND1. Nevertheless, the role of CDCA7L in other glioma cell lines and the explicit mechanisms underlying such an association warrant further assessment and validation.

In conclusion, the findings of this study indicate that CDCA7L plays a vital role in the progression and prognosis of human glioma. Moreover, CDCA7L is highly expressed in human glioma tissues, and a high CDCA7L expression predicts a poor prognosis for glioma patients. In addition, the downregulation of CDCA7L expression by CDCA7L siRNA inhibits the proliferation of U87 glioma cells by downregulating CCND1 both in vitro and in vivo. These findings indicate that the downregulation of CDCA7L supresses the growth of glioma U87 cells by inhibiting CCND1, and that CDCA7L may serve as a novel target in the clinical treatment for gliomas.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- CDCA7L

cell division cycle-associated 7 like

- GBM

glioblastoma

- LGG

low-grade glioma

- NBTs

normal brain tissues

- siRNA

small interfering RNA

- RT-qPCR

reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction

- CCND1

cyclin D1

- CCK8

Cell-Counting kit-8

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- IHC

immunohistochemistry

Funding

This article was supported by the Youth Fund Project of the First Affiliated Hospital of Xinxiang Medical University (grant no. QN-2017-B009).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

QKJ, XSL and FZS performed the cell culture, transfection, the cell proliferation assay and glioma xenografts. JWM performed the bioluminescence imaging in vivo. LYH and LH performed the IHC, western blot analysis and RT-qPCR analysis. QKJ and RHL performed the flow cytometric analysis. YJM collected and analyzed the patient data and performed the statistical analysis. BZJ contributed to the study conception and revised the study critically for important intellectual content. XSL and RHL were the major contributors to the writing of the manuscript. QKJ and JWM were the major contributors to modifying the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

According to the Declaration of Helsinki of 1964 and all subsequent revisions, and with approval of the Medical Ethics Committee of The First Affiliated Hospital of Xinxiang Medical University, the present study was accomplished with informed consent obtained from all patients. The animal experiments were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Xinxiang Medical and were carried out in strict accordance with the experimental protocol.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Fan YH, Xiao B, Lv SG, Ye MH, Zhu XG, Wu MJ. Lentivirus-mediated knockdown of chondroitin polymerizing factor inhibits glioma cell growth in vitro. Oncol Rep. 2017;38:1149–1155. doi: 10.3892/or.2017.5731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xiao B, Fan Y, Ye M, Lv S, Xu B, Chai Y, Wu M, Zhu X. Downregulation of COUP-TFII inhibits glioblastoma growth via targeting MPC1. Oncol Lett. 2018;15:9697–9702. doi: 10.3892/ol.2018.8601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ji CX, Fan YH, Xu F, Lv SG, Ye MH, Wu MJ, Zhu XG, Wu L. MicroRNA-375 inhibits glioma cell proliferation and migration by downregulating RWDD3 in vitro. Oncol Rep. 2018;39:1825–1834. doi: 10.3892/or.2018.6261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huang A, Ho CS, Ponzielli R, Barsyte-Lovejoy D, Bouffet E, Picard D, Hawkins CE, Penn LZ. Identification of a novel c-Myc protein interactor, JPO2, with transforming activity in medulloblastoma cells. Cancer Res. 2005;65:5607–5619. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schmidt EV. The role of c-myc in cellular growth control. Oncogene. 1999;18:2988–2996. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oster SK, Ho CS, Soucie EL, Penn LZ. The myc oncogene: Marvelously Complex. Adv Cancer Res. 2002;84:81–154. doi: 10.1016/S0065-230X(02)84004-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yi R, Feng J, Yang S, Huang X, Liao Y, Hu Z, Luo M. miR-484/MAP2/c-Myc-positive regulatory loop in glioma promotes tumor-initiating properties through ERK1/2 signaling. J Mol Histol. 2018;49:209–218. doi: 10.1007/s10735-018-9760-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tian Y, Huang C, Zhang H, Ni Q, Han S, Wang D, Han Z, Li X. CDCA7L promotes hepatocellular carcinoma progression by regulating the cell cycle. Int J Oncol. 2013;43:2082–2090. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2013.2142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shen FZ, Li XS, Ma JW, Wang XY, Zhao SP, Meng L, Liang SF, Zhao XL. Cell division cycle associated 7 like predicts unfavorable prognosis and promotes invasion in glioma. Pathol Res Pract. 2019;215:50–56. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2018.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Prescott JE, Osthus RC, Lee LA, Lewis BC, Shim H, Barrett JF, Guo Q, Hawkins AL, Griffin CA, Dang CV. A novel c-Myc-responsive gene, JPO1, participates in neoplastic transformation. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:48276–48284. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107357200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goto Y, Hayashi R, Muramatsu T, Ogawa H, Eguchi I, Oshida Y, Ohtani K, Yoshida K. JPO1/CDCA7, a novel transcription factor E2F1-induced protein, possesses intrinsic transcriptional regulator activity. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1759:60–68. doi: 10.1016/j.bbaexp.2006.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ou XM, Chen K, Shih JC. Monoamine oxidase A and repressor R1 are involved in apoptotic signaling pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:10923–10928. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601515103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li X, Tian Z, Jin H, Xu J, Hua X, Yan H, Liufu H, Wang J, Li J, Zhu J, et al. Decreased c-Myc mRNA stability via the MicroRNA 141-3p/AUF1 axis is crucial for p63alpha inhibition of cyclin D1 gene transcription and bladder cancer cell tumorigenicity. Mol Cell Biol. 2018;38 doi: 10.1128/MCB.00273-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ma J, Ren Y, Zhang L, Kong X, Wang T, Shi Y, Bu R. Knocking-down of CREPT prohibits the progression of oral squamous cell carcinoma and suppresses cyclin D1 and c-Myc expression. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0174309. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0174309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vadde R, Radhakrishnan S, Reddivari L, Vanamala JK. Triphala extract suppresses proliferation and induces apoptosis in human colon cancer stem cells via suppressing c-Myc/Cyclin D1 and elevation of Bax/Bcl-2 ratio. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:649263. doi: 10.1155/2015/649263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xu Z, Zeng X, Tian D, Xu H, Cai Q, Wang J, Chen Q. MicroRNA-383 inhibits anchorage-independent growth and induces cell cycle arrest of glioma cells by targeting CCND1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014;453:833–838. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.10.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim MK, Park GH, Eo HJ, Song HM, Lee JW, Kwon MJ, Koo JS, Jeong JB. Tanshinone I induces cyclin D1 proteasomal degradation in an ERK1/2 dependent way in human colorectal cancer cells. Fitoterapia. 2015;101:162–168. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2015.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xia B, Yang S, Liu T, Lou G. miR-211 suppresses epithelial ovarian cancer proliferation and cell-cycle progression by targeting Cyclin D1 and CDK6. Mol Cancer. 2015;14:57. doi: 10.1186/s12943-015-0322-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Monteiro LS, Diniz-Freitas M, Warnakulasuriya S, Garcia- Caballero T, Forteza-Vila J, Fraga M. Prognostic significance of cyclins A2, B1, D1, and E1 and CCND1 numerical aberrations in oral squamous cell carcinomas. Anal Cell Pathol (Amst) 2018;2018:7253510. doi: 10.1155/2018/7253510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Katunaric M, Jurisic D, Petkovic M, Grahovac M, Grahovac B, Zamolo G. EGFR and cyclin D1 in nodular melanoma: Correlation with pathohistological parameters and overall survival. Melanoma Res. 2014;24:584–591. doi: 10.1097/CMR.0000000000000123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.