The carbazolophane (Czp) donor unit is introduced to the design pool of donors in TADF emitters.

The carbazolophane (Czp) donor unit is introduced to the design pool of donors in TADF emitters.

Abstract

The carbazolophane (Czp) donor unit (indolo[2.2]paracyclophane) is introduced to the design pool of donors in thermally activated delayed fluorescence emitters. The increased steric bulk of the annelated donor unit forces an increased torsion between the carbazole and the aryl bridge resulting in a decreased ΔEST and an enhancement of the thermally activated delayed fluorescence in the triazine-containing emitter CzpPhTrz. Further, the closely stacked carbazole and benzene units of the paracyclophane show through-space π–π interactions, effectively increasing the spatial occupation for the HOMO orbital. The chiroptical properties of enantiomers of [2.2]paracyclophane reveal mirror image circular dichroism (CD) and circularly polarized luminescence (CPL) with glum of 1.3 × 10–3. rac-CzpPhTrz is a sky-blue emitter with λPL of 480 nm, a very small ΔEST of 0.16 eV and high ΦPL of 70% in 10 wt% doped DPEPO films. Sky blue-emitting OLEDs were fabricated with this new TADF emitter showing a high maximum EQE of 17% with CIE coordinates of (0.17, 0.25). A moderate EQE roll-off was also observed with an EQE of 12% at a display relevant luminance of 100 cd m–2. Our results show that the Czp donor contributes to both a decreased ΔEST and an increased photoluminescence quantum yield, both advantageous in the molecular design of TADF emitters.

Introduction

Organic Thermally Activated Delayed Fluorescence (TADF) materials have come to the fore as attractive alternative emitters in Organic Light-Emitting Diodes (OLEDs) as they, like current state-of-the-art phosphorescent emitters, can recruit 100% of the generated excitons into light.1 Since 2012, there are numerous examples in the literature of OLEDs using TADF emitters.

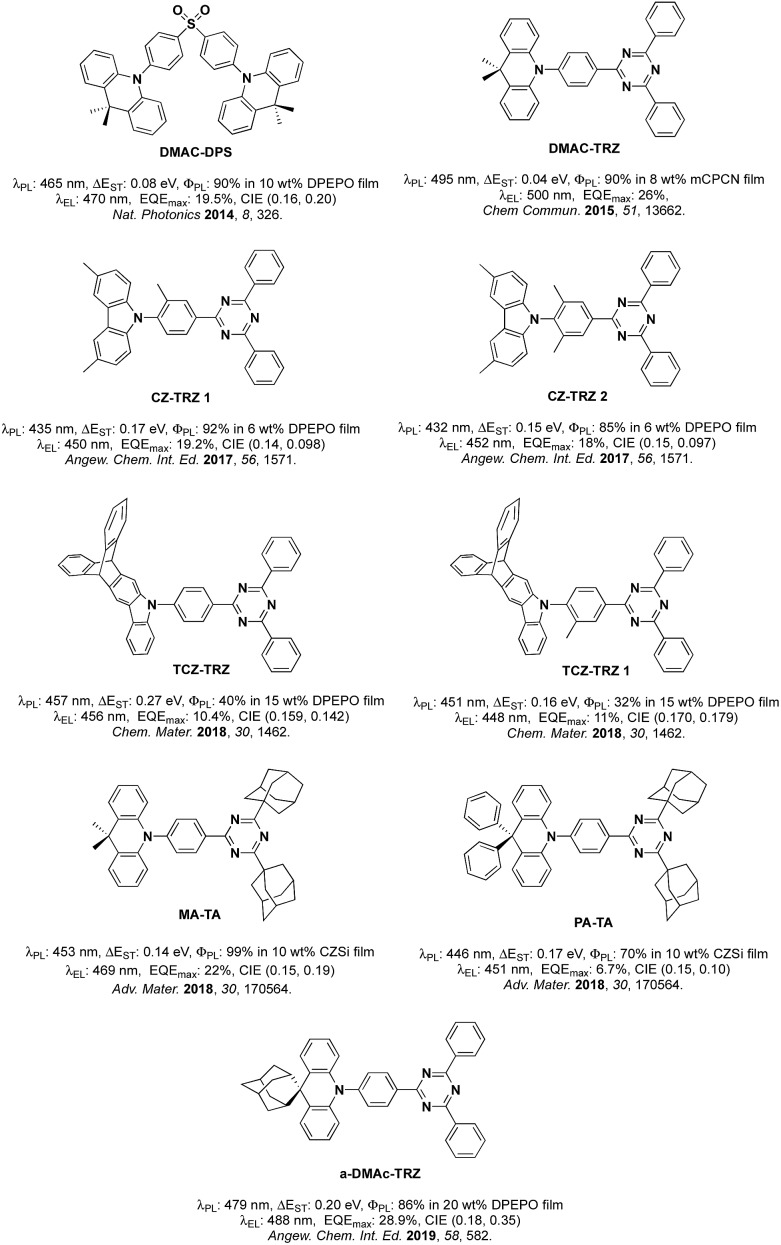

TADF in typical donor–acceptor (D–A) emitters is facilitated by a small singlet-triplet excited state energy difference, ΔEST, a consequence of the small exchange integral between spatially separated frontier molecular orbitals. The molecular design frequently relies on large torsions between the donor, where the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) resides and the bridging arene and/or between the bridge and the acceptor, where the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) is located. It becomes more difficult to adhere to this design paradigm in blue TADF emitters due to the reliance on weak carbazole (Cz) donors. The inherent size of Cz often results in much shallower torsions thereby leading to increased conjugation within the emitter and a larger ΔEST. Methylation of either Cz and/or the bridge has been explored as a strategy to combat the propensity for Cz to conjugate to the arene bridge.2 The state-of-the-art emitters based on the diphenyltriazine (cyaphenine) acceptor moiety in Fig. 1 illustrate these design principles. The methylation of bridging arene induced large torsions of between 71.2° and 82.3° in deep blue emitters Cz-Trz 1 and Cz-Trz 2, reported by Adachi et al. OLEDs using these emitters exhibited maximum external quantum efficiencies, EQEmax of 19.2 and 18.3% with CIE coordinates of (0.148, 0.09) and (0.15, 0.097) for Cz-TrZ 1 and Cz-Trz 2, respectively. Van Voorhis, Swager, Baldo, Buchwald et al.3 conducted a similar study using a triptycene extended carbazolyl donor unit (TCZ-TRZ), which showed a reduced overlap of the frontier orbitals than with the parent Cz donor-based emitter. Larger torsions were obtained through methyl substitution of the bridging arene (TCZ-TRZ 1). The photoluminescence quantum yield, ΦPL, in these blue-emitting compounds is significantly decreased compared to those reported by Adachi et al.2a OLEDs showed EQEmax values of 10.4 and 11% and CIE coordinates of (0.159, 0.142) and (0.170, 0.179) for TCZ-TRZ and TCZ-TRZ 1, respectively.

Fig. 1. Chemical structures and performance of known blue and triazine-based TADF emitters.

An alternative approach to functionalizing the weak Cz donor and arene bridge moieties of blue TADF compounds to control the balance of small ΔEST and high S1 energy is to employ a stronger, bulkier donor such as dimethylacridine (DMAC).4 For example, employing DMAC in combination with a diphenylsulfone acceptor (DMAC-DPS, Fig. 1) resulted in sky-blue emission with EQEmax and CIE coordinates of 19.5% and (0.16, 0.20).5 Upon changing the acceptor to diphenyltriazine in DMAC-TRZ, green emission (λEL = 500 nm) was obtained with EQEmax as high as 26%.6 Incorporation of adamantyl groups onto the cyaphenine acceptor (MA-TA, Fig. 1) resulted in a significant blue-shift in the emission and OLEDs with this emitter showed high EQEmax of 22% and CIE coordinates of (0.15, 0.19).4 When the donor was modified to 9,9-diphenyl-9,10-dihydroacridine (PA-TA), emission was further blue-shifted with CIE coordinates of (0.15, 0.10). However, the efficiency of the device suffered and the EQEmax was limited to 6.7%. Recently, an adamantyl-substituted acridine donor was introduced by Su et al.7 and coupled with a triazine acceptor. The rigid backbone of the donor in a-DMAc-TRZ suppressed nonradiative decay processes. Dual emission was observed from two conformers with an EQEmax of 28.9% and CIE of (0.18, 0.35).

Circularly polarized luminescence (CPL) enabled chiral molecules have been widely investigated for their potential applications in optical data storage8 and optical spintronics.9 In terms of display applications, such molecules are appealing especially in the development of circularly polarized OLEDs (CPOLEDs). At present, flat panel OLED-based display technologies require a film composed of a polarizer and a quarter wave plate to reduce the reflectance from the surroundings to a minimum in order to achieve high signal-to-noise contrast ratio.10 Such a solution is however inefficient as the polarizer absorbs half of the emission from an OLED. Such losses can be mitigated if there is CPL. CPL-active small organic molecules (CPL-SOMs), mainly fluorescent compounds, have been investigated in this context; however, currently only a small number of CPL-SOMs are efficient both in terms of high photoluminescence quantum yield (ΦPL) and luminescence dissymmetry factor (glum).11 Recently, a number of TADF-based CPL-SOMs have been reported (Fig. S1†). For example, Hirata et al. described a TADF CPL emitter, DPHN,12 by introducing a stereogenic carbon center between the donor and acceptor. This glum for this compound was 1.1 × 10–3, but there was a very low ΦPL of 4% in toluene. Pieters et al.13 enabled CPL emission in the TADF emitter R-1 through the incorporation of a BINOL unit that confers axial chirality to the molecule. The resulting compound exhibited glum of 1.3 × 10–3, a high ΦPL of 53% in toluene and OLEDs displayed EQEmax of 9.1%. A chiral trans-1,2-diaminocyclohexane was used to link two imide-based TADF emitters in CAI-Cz.14 Each enantiomer showed a glum value of 1.1 × 10–3 and ΦPL as high as 98%. The resulting CPOLEDs exhibited excellent performances with an EQEmax of 19.8% with gEL values of –1.7 × 10–3 and 2.3 × 10–3 for the two enantiomers. Tang et al.15 used a similar design to that of Pieters et al. However, in their design they combine in a single emitter BN-CF TADF, AIE (aggregation-induced emission) and CPL properties. BN-CF showed a glum of 1.2 × 10–2, ΦPL of 32% in toluene, and the CPOLEDs exhibited an EQEmax of 9.3% and gEL of 2.6 × 10–2. Recently, Zhao et al.16 explored the inherent planar chirality of a [2.2]paracyclophane moiety. Emitter g-BNMe2-Cp exhibited glum of 4.24 × 10–3 and ΦPL of 46% in toluene.

Results and discussion

We recently demonstrated the first use of a [2.2]paracyclophane bridge within the design of TADF emitters where we exploited the π-stacking interactions of the two arene decks to moderate the electronic coupling of donor and acceptor groups.17 In this report, we demonstrate an effective design strategy to obtain both TADF and CPL in [2.2]paracyclophanes (PCP). We exploit the PCP to modulate the torsional angle of the donor with respect to the bridge and its inherent strength and thereby enhance the reverse intersystem crossing (RISC) efficiency in CzpPhTrz compared to the reference emitter CzPhTrz (Fig. 2). Further, the π–π stacking within the PCP enhances HOMO delocalization, thereby increasing the donor strength. Our donor design concept is based on an indole-annelated [2.2]paracyclophane, providing the carbazolophane (Czp, [2]paracyclo[2](1,4)carbazolophane). This compact skeleton features a closely coplanar stacked benzene unit on top of a carbazole bridged by two ethylene linkers that slightly bend the arenes from planarity. The short deck distance enables a through-space π–π interaction thereby delocalizing the HOMO and perturbing the electronics and strengthening the donor. We further exploited the inherent planar chirality of the PCP scaffold to develop enantiopure TADF chromophores, (RP)-CzpPhTrz and (SP)-CzpPhTrz. We report the chiroptical properties of the enantiomers both in the ground and excited states with circular dichroism (CD) and CPL spectroscopy, respectively. The photophysical investigations of (rac)-CzpPhTrz revealed its excellent TADF properties with a small ΔEST of 0.16 eV, a value smaller than those previously reported in Fig. 1, and a high photoluminescence quantum yield, ΦPL, of 69% in 10 wt% DPEPO doped films. OLEDs fabricated using (rac)-CzpPhTrz showed sky blue emission with EQEmax as high as 17% and CIE coordinates of (0.17, 0.25). The impact of this donor is clear when compared to the OLED using (rac)-CzPhTrz, which exhibited a blue-shifted emission with CIE coordinates of (0.14, 0.12) along with a much lower EQEmax of 5.8%.

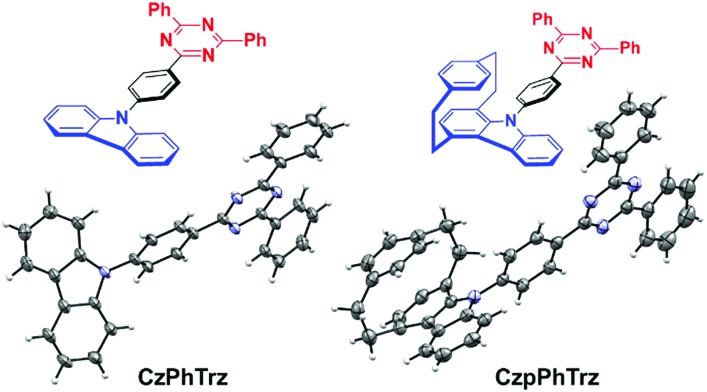

Fig. 2. Carbazol(ophan)yl triazine TADF emitters with molecular structures of CzPhTrz (left) and (rac)-CzpPhTrz (right) drawn at 50% probability level.

Synthesis

The Czp donor was synthesized according to the protocol described by Bolm et al.18 (see ESI†). Emitters CzPhTrz and (rac)-CzpPhTrz were obtained in fair and good yields of 42% and 84%, respectively following nucleophilic aromatic substitution of the respective donors with fluorophenyltriazine. Both emitters were purified using a combination of column chromatography, recrystallization and gradient sublimation.§

The structures of both emitters were unequivocally determined by single crystal X-ray diffractometry (Fig. 2). The presence of the cyclophane in (rac)-CzpPhTrz induces a torsion of 55.86° between the planes of the Czp donor and the phenyl bridge while the corresponding torsion in CzPhTrz is significantly shallower at 45.11°. The distance between decks in the PCP core is 3.07 Å at the N-connected carbon atom, which is consistent with distances in both the free carbazolophane18 (3.06 Å) and nonsubstituted [2.2]paracyclophanes (3.08–3.10 Å).19

Thermal gravimetric analysis (TGA) and differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) were employed to assess the thermal stability of (rac)-CzpPhTrz (Fig. S8†). (rac)-CzpPhTrz exhibited excellent thermal stability with a decomposition temperature, Td, corresponding to a 5% weight loss, of 360 °C, which is a little higher than 330 °C measured for CzPhTrz. CzPhTrz and (rac)-CzpPhTrz exhibited melting temperatures, Tm of 270 °C and 263 °C, respectively, ensuring the formation of stable films of both emitters by vacuum deposition. The presence of a PCP structural unit introduces planar chirality to the emitter. Enantiomeric emitters (RP)-CzpPhTrz and (SP)-CzpPhTrz were also obtained. These were synthesized from the chiral Czp intermediates, which were separated by chiral HPLC. The absolute configuration could be unambiguously assigned by CD (see ESI† Section 5).

Theoretical properties

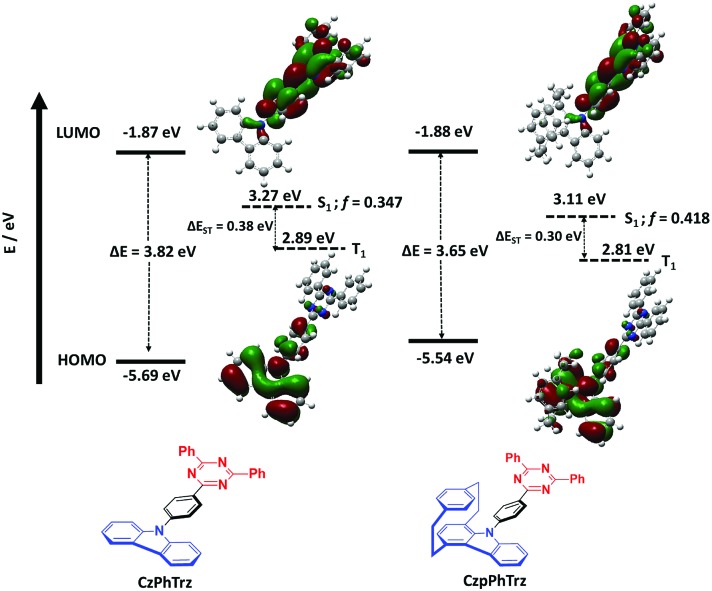

Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations were conducted on both CzPhTrz and CzpPhTrz (Fig. 3) in order to gain insight into the impact of the use of the Czp donor on the optoelectronic properties of the emitters. In both emitters, the HOMO is localized on the carbazole-based donor with some contribution extending onto the phenyl bridge while the LUMO is distributed over both the phenyl bridge and the triazine acceptor. For CzpPhTrz, the HOMO is extended significantly onto the PCP core owing to the strong π–π through-space interactions within the Czp donor. CzPhTrz has been previously studied where it has been reported20 to possess a rod-like structure coupled with a ΔEST of 0.36 eV and a calculated dihedral angle between the Cz and the phenyl bridge of 51.8°. The large ΔEST for this molecule leads to inefficient TADF. Lee et al.20 further showed CzPhTrz to be isotropic in the DPEPO film and so without the horizontal orientation desired to improve light outcoupling. OLEDs fabricated with this emitter (λEL = 449 nm) showed an EQEmax of only 4.2% (EQE1000 = 0.6%) despite a photoluminescence quantum yield, ΦPL, of 71%. We similarly calculated a small twist angle of 51° between the donor and phenyl bridge, in a good agreement with the crystal structure analysis (45.11°, Fig. 2), and a large ΔEST of 0.38 eV in CzPhTrz (Fig. 3). Introduction of the rigid and sterically bulky PCP onto the donor in CzpPhTrz not only induced a larger torsion between the donor and the bridge but also extended the conjugation length. Thus, Czp is a stronger donor, the impact of which is a lower S1 energy, a smaller ΔEST and a more efficient TADF process in CzpPhTrz. Indeed, DFT calculations predict an increased torsion of 58° (55.86° in the crystal structure), a smaller ΔEST of 0.30 eV and a lower S1 energy of 3.11 eV compared to CzPhTrz [E(S1) = 3.27 eV]. The S1 energy is nevertheless predicted to be sufficiently high such that CzpPhTrz should remain a good blue TADF emitter candidate.

Fig. 3. DFT [PBE0/6-31G(d,p)] calculated ground and TDA-based excited state energies and electron density distributions of the HOMOs and LUMOs of CzPhTrz (left) and CzpPhTrz (right), f is the oscillator strength.

Electrochemical properties

The HOMO and LUMO levels of CzPhTrz and CzpPhTrz were ascertained by cyclic voltammetry (CV) and differential pulse voltammetry (DPV) measurements, respectively, in dichloromethane. The CVs and DPVs are shown in Fig. S7† and data are summarized in Table 1. Both emitters possess similar reduction potentials at –1.78 V, which were assigned to the reduction of the cyaphenine acceptor. However, and in line with the theoretical studies, the oxidation potential of CzpPhTrz (1.14 V) is significantly cathodically shifted to that of CzPhTrz (1.43 V). Thus, the introduction of the PCP moiety appreciably reduces the ionization potential (IP) of the donor and thus the electrochemical gap. Expectedly, the oxidation waves of both compounds were found to be irreversible as the carbazole radical cation is known to be electrochemically unstable and subsequently can undergo dimerization.21

Table 1. Photophysical and electrochemical properties of CzPhTrz and CzpPhTrz.

| λ abs a , [nm] | λ PL a , [nm] | Φ PL b , [%] | λ PL c , [nm] | Φ PL c , [%] | τ p c , [ns] | τ d c , [μs] | HOMO d , e , [eV] | LUMO d , e , [eV] | ΔEredox f , [eV] | S 1/T1 g , [eV] | ΔEST g , [eV] | |

| CzPhTrz | 363 | 446 | 60 (58) | 448 | 50 | 4.8 | — | –6.11 | –3.26 | 2.86 | 3.14/2.82 | 0.32 |

| CzpPhTrz | 375 | 470 | 70 (55) | 482 | 69 | 7 | 65 | –5.80 | –3.23 | 2.58 | 2.89/2.73 | 0.16 |

aIn PhMe at 298 K.

bQuinine sulfate (0.5 m) in H2SO4 (aq) was used as the reference (ΦPL: 54.6%, λexc = 360 nm).15 Values quoted are in degassed solutions, which were prepared by three freeze-pump-thaw cycles. Values in parentheses are for aerated solutions, which were prepared by bubbling air for 10 min.

cThin films were prepared by vacuum depositing 10 wt% doped samples in DPEPO and values were determined using an integrating sphere (λexc = 360 nm); degassing was done by N2 purge for 10 minutes.

dIn DCM with 0.1 m [nBu4N]PF6 as the supporting electrolyte and Fc/Fc+ as the internal reference (0.46 V vs. SCE).16

eThe HOMO and LUMO energies were determined using EHOMO/LUMO = –(Eoxpa,1/Eredpc,1 + 4.8) eV (ref. 17) where Eoxpa and Eredpc are anodic and cathodic peak potentials, respectively.

fΔEredox = |EHOMO – ELUMO|.

gDetermined from the onset of prompt and delayed spectra of 10 wt% doped films in DPEPO, measured at 77 K (λexc = 355 nm).

Photophysical properties

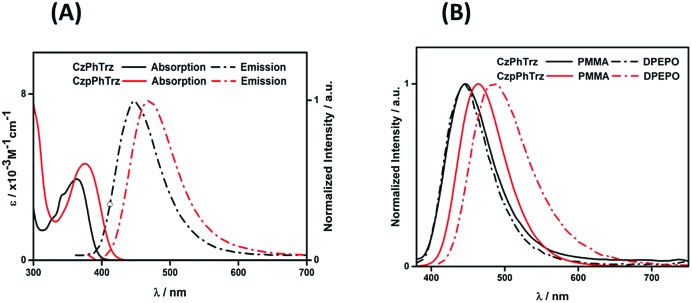

Fig. 4A shows the UV-Vis absorption and photoluminescence (PL) spectra of CzPhTrz and CzpPhTrz in toluene and the data are summarized in Table 1. Both compounds possess an intramolecular charge transfer (ICT) absorption band from the carbazole-based donor to the triazine acceptor at 363 and 375 nm, respectively, for CzPhTrz and CzpPhTrz. The more intense and red-shifted band in CzpPhTrz agrees with the calculations shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 4. (A) UV-vis absorption and PL spectra in PhMe (B) PL spectra of thin films of CzPhTrz and CzpPhTrz (λexc = 360 nm).

Both compounds exhibited unstructured PL spectra in PhMe, indicative of an excited state with strong intramolecular charge transfer (ICT) character. Analogous to their relative behavior in the ground state, the photoluminescence maximum, λPL, of CzpPhTrz at 470 nm is red-shifted compared to that of CzPhTrz (λPL = 446 nm). The ΦPL values in PhMe for CzPhTrz and CzpPhTrz are 60% and 70%, which decreased to 58% and 55%, respectively, upon exposure to air. The enhanced ΦPL of CzpPhTrz is consistent with the higher predicted oscillator strength. The time-resolved PL spectra in PhMe for both emitters (Fig. S9†), however, do not show any delayed emission, which would suggest that the TADF mechanism in solution is very weak despite the oxygen sensitivity noted for ΦPL.

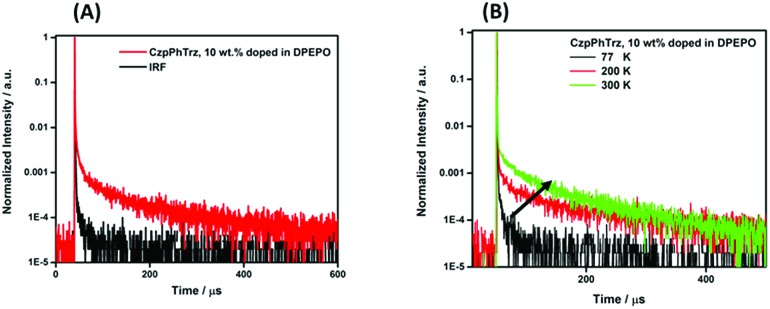

We next investigated the PL behavior in the solid-state as doped thin films (Fig. 4B). In both PMMA and DPEPO matrices, both compounds showed unstructured ICT-based emission. In 10 wt% doped solution-processed PMMA films, CzPhTrz shows deep blue emission with λPL of 446 nm; the emission energy is essentially the same in vacuum-deposited 10 wt% doped DPEPO films at 448 nm. The emission of CzpPhTrz is expectedly red-shifted at 464 nm in PMMA, and this emission is further red-shifted to 482 nm in the more polar DPEPO. The ΦPL values of the PMMA films of CzPhTrz and CzpPhTrz are 25% and 45%, respectively. Further, both compounds exhibited a mono exponential decay with PL lifetimes, τ of 5 ns for CzPhTrz and 8 ns for CzpPhTrz, suggesting that TADF mechanism is absent in a non-polar host like PMMA, results in line with those observed in PhMe. The much enhanced ΦPL of CzpPhTrz is 69% in DPEPO, which is significantly higher than that of CzPhTrz (ΦPL = 50%). Reducing the doping concentration to 1 wt% resulted in a lower ΦPL of 43% for CzpPhTrz (Table S2†). Time-resolved PL measurements of the 10 wt% DPEPO films revealed divergent behavior between the two emitters. Only a nanosecond (τ = 4.8 ns) monoexponential fluorescence decay was observed for CzPhTrz (Fig. S10†), results that agree with the literature.20 For CzpPhTrz, both prompt (τp = 7 ns) and delayed (τd = 65 μs) emission was observed (Fig. 5A). We next studied the temperature dependence of the delayed lifetime of CzpPhTrz (Fig. 5B). An increase in the intensity of the delayed emission as a function of increasing temperature provides corroborating evidence to support the TADF character of CzpPhTrz.

Fig. 5. (A) Time-resolved PL decay curve and (B) temperature dependence of time-resolved PL lifetime of CzpPhTrz in 10 wt% DPEPO film (λexc = 378 nm), IRF = instrument response function.

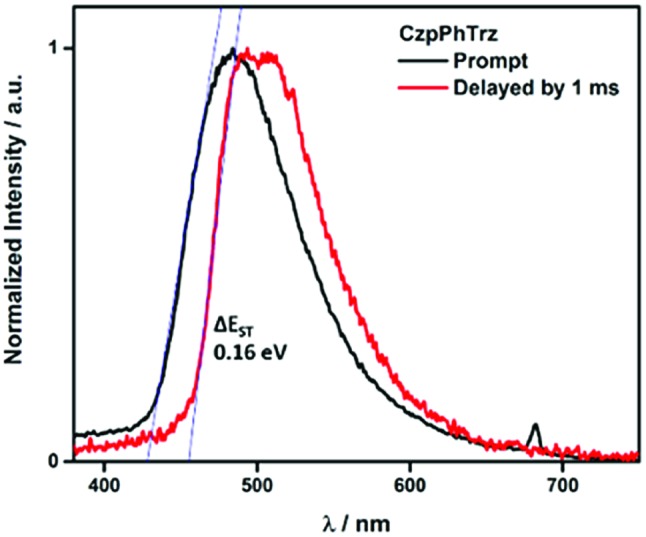

The ΔEST of CzPhTrz and CzpPhTrz were determined from the singlet and triplet energies estimated from the onset of the prompt and delayed emission spectra, respectively, measured in 10 wt% DPEPO doped films at 77 K (Fig. 6). CzpPhTrz possesses a high S1 energy of 2.90 eV [E(S1) = 2.87 eV at room temperature] coupled with a small ΔEST value of 0.16 eV, confirming its strong potential as a blue TADF emitter. The turn-on of the TADF in DPEPO is due to preferential stabilization of the 1CT state and the associated decrease in ΔEST. On the other hand, a rather large ΔEST of 0.32 eV (Fig. S11†) was determined for CzPhTrz, implying a much weaker TADF character. These results clearly demonstrate that the introduction of the bulky PCP moiety with the carbazole donor to form the carbazolophane (Czp) not only turns on the TADF channel in the emission mechanism in polar media, but the high ΦPL is maintained.

Fig. 6. Prompt and delayed spectra (at 77 K) of CzpPhTrz in 10 wt% DPEPO film (λexc = 355 nm).

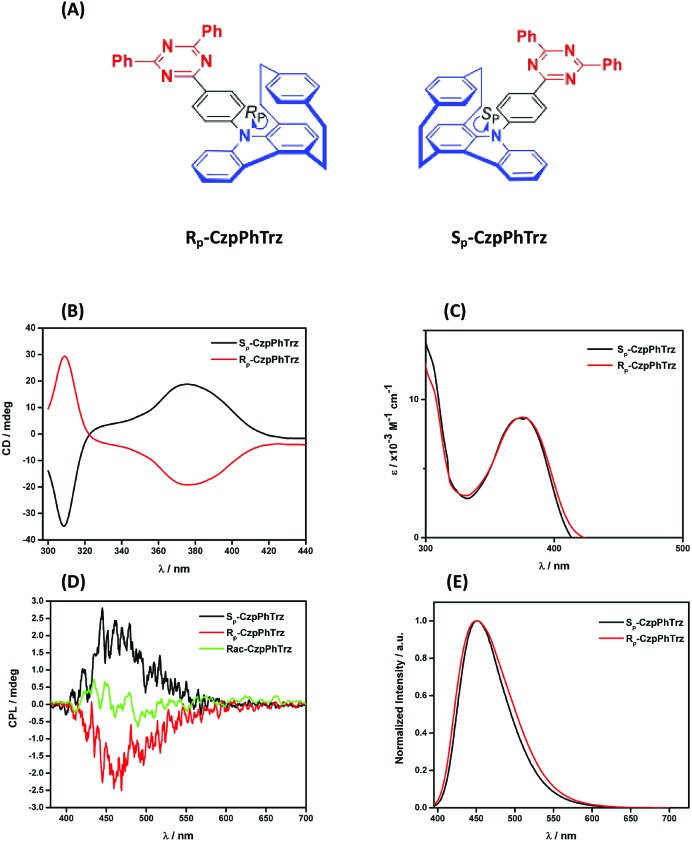

Chiroptical properties

The ground and excited state chiroptical properties of (R, S)-CzpPhTrz (Fig. 7a) were studied by CD and CPL spectroscopy, respectively in toluene. As shown in Fig. 7B, there is the expected mirror image spectra corresponding to each of the two enantiomers. Using the molar extinction coefficients ε(R) and ε(S) (Fig. 7C) of the CT band at 375 nm, the CD dissymmetry factor was estimated to be +5.0 × 10–3 and –7.0 × 10–3 for the RP and SP enantiomers, respectively. Similarly, mirror image CPL spectra (Fig. 7D) were obtained with glum values for both RP and SP enantiomers at their emission maxima at 1.2 × 10–3 and 1.3 × 10–3. These are typical values for CPL-SOMs.

Fig. 7. (A) Chemical structures (B) CD (C) UV-vis (D) CPL and (E) PL spectra of (RP)-CzpPhTrz and (SP)-CzpPhTrz in degassed PhMe (λexc = 375 nm).

Device fabrication

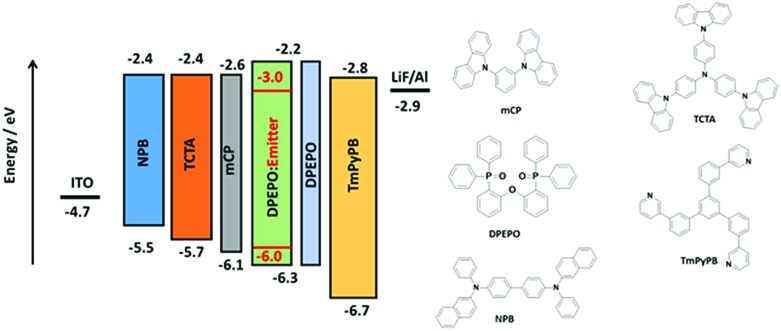

Based on the promising photophysical properties of rac-CzpPhTrz in DPEPO films, we fabricated vacuum-deposited multilayer OLEDs. A deep HOMO level of –6.06 eV for rac-CzpPhTrz was measured by UV ambient pressure photoemission spectroscopy (APS), which is deeper than that inferred from cyclic voltammetry measurements (EHOMO = 5.80 eV, Table 1) by 0.26 eV, due in part to the different measurement environments (neat film for APS and DCM for DPV). Therefore, to confine the excitons in the emissive layer, DPEPO, with a HOMO energy of –6.3 eV was chosen as a host material in the emissive layer.22 Optimum host and doping concentration were assessed by absolute ΦPL measurements (Table S2†). An energy level diagram of the OLED stack and chemical structures of the materials used are shown in Fig. 8. The OLED architecture employed consisted of: ITO/NPB (30 nm)/TCTA (20 nm)/mCP (10 nm)/rac-CzpPhTrz : DPEPO (10 wt%, 20 nm)/DPEPO (10 nm)/TmPyPB (40 nm)/LiF (1 nm)/Al (100 nm), where N,N′-bis(naphthalen-1-yl)-N,N′-bis(phenyl)benzidine (NPB) was used as a hole injection layer (HIL), tris(4-carbazoyl-9-ylphenyl)amine (TCTA) was used as a hole transporting layer (HTL), mCP (1,3-bis(N-carbazolyl)benzene) and DPEPO were used as an electron and hole blockers, respectively. The electron transporting layer (ETL) was comprised of 1,3,5-tris(3-pyridyl-3-phenyl)benzene (TmPyPB), which possesses a high electron mobility of 10–4 cm2 V–1 s–1 and a high triplet energy of 2.75 eV along with a deep HOMO energy of 6.7 eV.23 We also fabricated the reference OLED using CzPhTrz as the emitter using the same device architecture.

Fig. 8. Chemical structures and energy levels of materials used for the device fabrication.

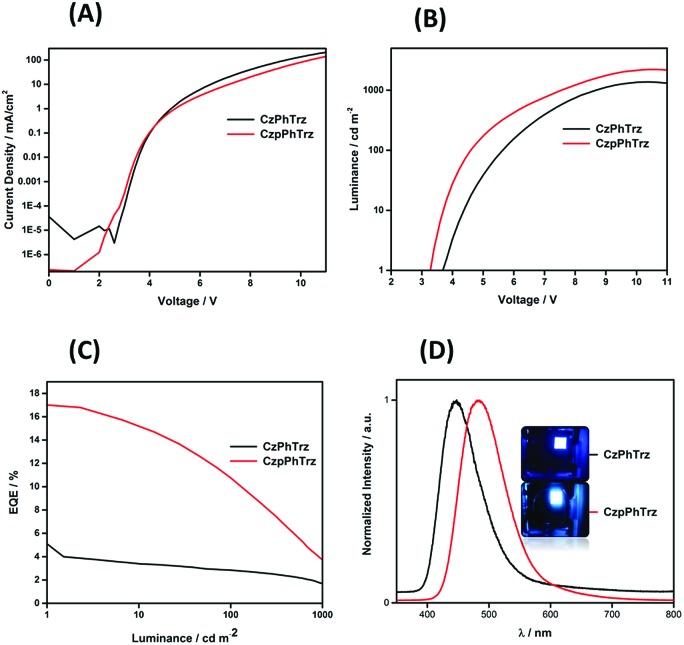

The electroluminescence (EL) properties are shown in Fig. 9 and the data are summarized in Table 2. OLEDs based on CzPhTrz exhibited a deep blue emission with a λEL of 446 nm and CIE coordinates of (0.16, 0.12) whereas devices employing rac-CzpPhTrz showed a slightly red-shifted emission with a λEL of 480 nm and CIE coordinates of (0.17, 0.25). The EL spectra matched very well to the corresponding PL spectra. Both devices exhibited steep current-voltage-luminance behavior (Fig. 9A and B) and low turn-on voltages (Von) of 3.6 V and 3.2 V for the OLEDs based on CzPhTrz and rac-CzpPhTrz, respectively. The lower Von for the OLED with rac-CzpPhTrz is attributed to the lower energy gap of this emitter.

Fig. 9. (A) Current density–voltage characteristics (B) luminance vs. voltage. (C) EQE vs. luminance (D) normalized EL spectra of CzPhTrz and CzpPhTrz.

Table 2. Electroluminescence properties of CzPhTrz and CzpPhTrz.

| V on a , [V] | λ EL b , [nm] | EQEmax c , EQE100 d , [%] | CEmax c , [cd A–1] | PEmax c , [lm W–1] | CIE e , (x, y) | |

| CzPhTrz | 3.6 | 446 | 5.8; 2.8 | 10.5 | 8.6 | (0.14, 0.12) |

| CzpPhTrz | 3.2 | 480 | 17.0; 12.0 | 34.8 | 32.5 | (0.17, 0.25) |

aMeasured at 1 cd m–2.

bEmission maxima at 1 mA cm–2.

cMaximum efficiencies at 1 cd m–2.

dEQE at 100 cd m–2.

eCommission Internationale de l'Eclairage coordinates at 1 mA cm–2.

Fig. 9C shows the EQE versus luminance of the two OLEDs. The device with rac-CzpPhTrz exhibited a high EQEmax of 17% at low brightness (at 1 cd m–2), indicating an efficient triplet harvesting in the OLED mediated by the TADF channel. Further the device showed a moderate efficiency roll-off to 12% at a display relevant brightness of 100 cd m–2. Assuming the recombination efficiency to be unity and taking the ΦPL of 70%, the device with rac-CzpPhTrz possessed an outcoupling efficiency of 25%. On the other hand, devices based on CzPhTrz showed an EQEmax of 5.8% at low brightness, which reduced to 2.8% at 100 cd m–2. The significantly poorer performance is due in part to the larger ΔEST of the emitter, which renders TADF very inefficient in the device. To summarize, we observed a three-fold enhancement in the EQEmax as a function of the use of the Czp donor in rac-CzpPhTrz. To the best of our knowledge, the OLED with rac-CzpPhTrz is the first example of an EL device incorporating a [2.2]paracyclophane moiety. rac-CzpPhTrz indeed is amongst the state-of-the art blue to sky-blue TADF triazine-based emitters in terms of EQEmax though at a cost of a red-shifted EL spectrum compared to OLEDs based on emitters shown in Fig. 1.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we have demonstrated how TADF and CPL can be turned on in triazine emitters through incorporation of a [2.2]paracyclophane moiety within the carbazole donor structure. The resulting carbazolophane (Czp) donor unit both provides a through-space π–π interaction and an increased torsion as a function of the increased inherent bulkiness of the donor. This enhances the donor strength and forces a larger torsion between the donor and the phenyl bridge, leading to a much more efficient TADF process. Moreover, the enantiomers possessed mirror image CD and CPL spectra with glum in line with other CPL-SOMs. The resulting sky-blue OLED showed a three-fold enhancement in performance compared to the reference device with EQEmax of 17%. These results demonstrate clearly the value of the Czp donor, which we believe can be applied to a whole range of TADF emitters to enhance OLED and CPL performance.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts to declare.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the EPSRC for financial support (grants EP/P010482/1, EP/R035164/1 and EP/L017008/1). We thank the EPSRC UK National Mass Spectrometry Facility at Swansea University for analytical services. E. Z.-C. thanks the University of St Andrews for support. E. S. and S. B. acknowledge funding from DFG in the frame of SFB1176 (projects A4, B3 and C6) and KSOP (fellowship to E. S.). C. M. M. greatly acknowledges financial support by the cluster of excellence (3DMM2O). We are grateful to JST-ERATO for financial support (grant JPMJER1305). We thank the JSPS Core-to-Core Program for financial support. The measurement of CPL was made using CPL-200 (JASCO) at the Natural Science Center for Basic Research and Development (N-BARD), Hiroshima University.

Footnotes

†Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available: CCDC 1871934 and 1871935. For ESI and crystallographic data in CIF or other electronic format see DOI: 10.1039/c9sc01821b. The research data supporting this publication can be accessed at https://doi.org/10.17630/530b50cb-3a77-4256-b5fe-47917e7eaae6

§Synthesis, NMR spectra, elemental analysis data, TGA and DSC, cyclic voltammetry data, supplementary photophysical measurements, computational data, electroluminescence data and crystallographic data (CCDC-1871934 and CCDC-1871935). During the proofs stage it has been pointed out to us that the structure and synthesis of CzpPhTRZ has appeared in a patent: Buchwald, S. L.; Huang, W., “[2.2]Paracyclophane-Derived Donor/Acceptor-Type Molecules for OLED Applications”, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, International Patent application number PCT/US2016/035655, published 8 December 2016.

References

- (a) Yang Z., Mao Z., Xie Z., Zhang Y., Liu S., Zhao J., Xu J., Chi Z., Aldred M. P. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2017;46:915–1016. doi: 10.1039/c6cs00368k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Wong M. Y., Zysman-Colman E. Adv. Mater. 2017;29:1605444. doi: 10.1002/adma.201605444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Liu Y., Li C., Ren Z., Yan S., Bryce M. R. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2018;3:18020. [Google Scholar]

- (a) Cui L. S., Nomura H., Geng Y., Kim J. U., Nakanotani H., Adachi C. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 2017;56:1571–1575. doi: 10.1002/anie.201609459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Duan Y.-C., Wen L.-L., Gao Y., Wu Y., Zhao L., Geng Y., Shan G.-G., Zhang M., Su Z.-M. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2018;122:23091–23101. [Google Scholar]

- Huang W., Einzinger M., Zhu T., Chae H. S., Jeon S., Ihn S.-G., Sim M., Kim S., Su M., Teverovskiy G., Wu T., Van Voorhis T., Swager T. M., Baldo M. A., Buchwald S. L. Chem. Mater. 2018;30:1462–1466. [Google Scholar]

- Wada Y., Kubo S., Kaji H. Adv. Mater. 2018;30:1705641. doi: 10.1002/adma.201705641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q., Li B., Huang S., Nomura H., Tanaka H., Adachi C. Nat. Photonics. 2014;8:326–332. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai W.-L., Huang M.-H., Lee W.-K., Hsu Y.-J., Pan K.-C., Huang Y.-H., Ting H.-C., Sarma M., Ho Y.-Y., Hu H.-C., Chen C.-C., Lee M.-T., Wong K.-T., Wu C.-C. Chem. Commun. 2015;51:13662–13665. doi: 10.1039/c5cc05022g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W., Cai X., Li B., Gan L., He Y., Liu K., Chen D., Wu Y.-C., Su S.-J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019;58:582–586. doi: 10.1002/anie.201811703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C., Fei H., Qiu Y., Yang Y., Wei Z., Tian Y., Chen Y., Zhao Y. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1999;74:19–21. [Google Scholar]

- Harada T., Hayakawa H., Watanabe M., Takamoto M. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2016;87:075102. doi: 10.1063/1.4954725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim B. C., Lim Y. J., Song J. H., Lee J. H., Jeong K. U., Lee J. H., Lee G. D., Lee S. H. Opt. Express. 2014;22(Suppl. 7):A1725–A1730. doi: 10.1364/OE.22.0A1725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Carnerero E. M., Agarrabeitia A. R., Moreno F., Maroto B. L., Muller G., Ortiz M. J., de la Moya S. Chemistry. 2015;21:13488–13500. doi: 10.1002/chem.201501178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imagawa T., Hirata S., Totani K., Watanabe T., Vacha M. Chem. Commun. 2015;51:13268–13271. doi: 10.1039/c5cc04105h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feuillastre S., Pauton M., Gao L., Desmarchelier A., Riives A. J., Prim D., Tondelier D., Geffroy B., Muller G., Clavier G., Pieters G. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016;138:3990–3993. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b00850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M., Li S. H., Zhang D., Cai M., Duan L., Fung M. K., Chen C. F. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 2018;57:2889–2893. doi: 10.1002/anie.201800198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song F., Xu Z., Zhang Q., Zhao Z., Zhang H., Zhao W., Qiu Z., Qi C., Zhang H., Sung H. H. Y., Williams I. D., Lam J. W. Y., Zhao Z., Qin A., Ma D., Tang B. Z. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2018;28:1800051. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M. Y., Li Z. Y., Lu B., Wang Y., Ma Y. D., Zhao C. H. Org. Lett. 2018;20:6868–6871. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.8b02995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spuling E., Sharma N., Samuel I. D. W., Zysman-Colman E., Bräse S. Chem. Commun. 2018;54:9278–9281. doi: 10.1039/c8cc04594a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lennartz P., Raabe G., Bolm C. Isr. J. Chem. 2012;52:171–179. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf H., Leusser D., Jørgensen M. R. V., Herbst-Irmer R., Chen Y.-S., Scheidt E.-W., Scherer W., Iversen B. B., Stalke D. Chem.–Eur. J. 2014;20:7048–7053. doi: 10.1002/chem.201304972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byeon S. Y., Kim J., Lee D. R., Han S. H., Forrest S. R., Lee J. Y. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2018;6:1701340. [Google Scholar]

- (a) Tomkeviciene A., Grazulevicius J. V., Volyniuk D., Jankauskas V., Sini G. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2014;16:13932–13942. doi: 10.1039/c4cp00302k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Fukushima T., Yamamoto J., Fukuchi M., Hirata S., Jung H. H., Hirata O., Shibano Y., Adachi C., Kaji H. AIP Adv. 2015;5:087124. [Google Scholar]

- Han C., Zhao Y., Xu H., Chen J., Deng Z., Ma D., Li Q., Yan P. Chem.–Eur. J. 2011;17:5800–5803. doi: 10.1002/chem.201100254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su S.-J., Chiba T., Takeda T., Kido J. Adv. Mater. 2008;20:2125–2130. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.