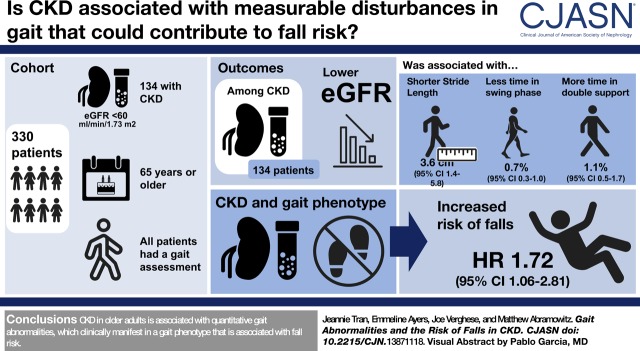

Visual Abstract

Keywords: geriatric nephrology; chronic kidney disease; Walking Speed; Accidental Falls; Independent Living; glomerular filtration rate; Proportional Hazards Models; Gait; Risk; Renal Insufficiency, Chronic; eGFR protein, human; Receptor, Epidermal Growth Factor; Phenotype

Abstract

Background and objectives

Older adults with CKD are at high risk of falls and disability. It is not known whether gait abnormalities contribute to this risk.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

Quantitative and clinical gait assessments were performed in 330 nondisabled community-dwelling adults aged ≥65 years. CKD was defined as an eGFR <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2. Cox proportional hazards models were created to examine fall risk.

Results

A total of 41% (n=134) of participants had CKD. In addition to slower gait speed, participants with CKD had gait cycle abnormalities including shorter stride length and greater time in the stance and double-support phases. Among people with CKD, lower eGFR was independently associated with the severity of gait cycle abnormalities (per 10 ml/min per 1.73 m2 lower eGFR: 3.6 cm [95% confidence interval (95% CI), 1.4 to 5.8] shorter stride length; 0.7% [95% CI, 0.3 to 1.0] less time in swing phase; 1.1% [95% CI, 0.5 to 1.7] greater time in double-support phase); these abnormalities mediated the association of lower eGFR with slower gait speed. On clinical gait exam, consistent with the quantitative abnormalities, short steps and marked swaying or loss of balance were more common among participants with CKD, yet most had no identifiable gait phenotype. A gait phenotype defined by any of these abnormal signs was associated with higher risk of falls among participants with CKD: compared with people without CKD and without the gait phenotype, the adjusted hazard ratio was 1.72 (95% CI, 1.06 to 2.81) for those with CKD and the phenotype; in comparison, the adjusted hazard ratio was 0.71 (95% CI, 0.40 to 1.25) for people with CKD but without the phenotype (P value for interaction of CKD status and gait phenotype =0.01).

Conclusions

CKD in older adults is associated with quantitative gait abnormalities, which clinically manifest in a gait phenotype that is associated with fall risk.

Introduction

CKD affects approximately 26 million adults in the United States and over 20% of individuals aged 65 and older (1,2). Older Americans with CKD are at particularly high risk of mobility impairment and disability. Numerous studies have documented high rates of functional limitation (3,4); falls are common (5,6); and the risk of fall-related injuries is compounded by bone disease, which increases the risk of fracture (7). These consequences all contribute to loss of independence, hospitalizations, and death (8,9). Improving the care of this vulnerable patient population requires an improved understanding of the underlying causes of functional impairment and better identification of individuals at high risk of functional decline.

Studies in older adults have identified several markers of physical function that provide prognostic information on adverse health outcomes. These include measures of lower extremity function and overall physical performance, as well as simple metrics such as gait speed (9,10). Among older persons, slow gait speed is associated with poor outcomes, including falls, disability, and reduced survival (10–12). However, gait is a multifaceted motor phenomenon, and other aspects of gait are also informative. For example, clinically diagnosed gait phenotypes are associated with both the onset of dementia and falls (12,13). Furthermore, subtle abnormalities may be present even in people with an apparently normal gait on clinical examination, and these can be detected by quantitative gait assessment (12). These subclinical gait abnormalities provide prognostic information: increased gait variability and time spent in the double-support phase of the gait cycle, when both feet are on the ground, are strongly associated with fall risk (12). Therefore, given the impact of fall-related injuries, quantitative gait abnormalities likely promote the development of functional limitation and disability.

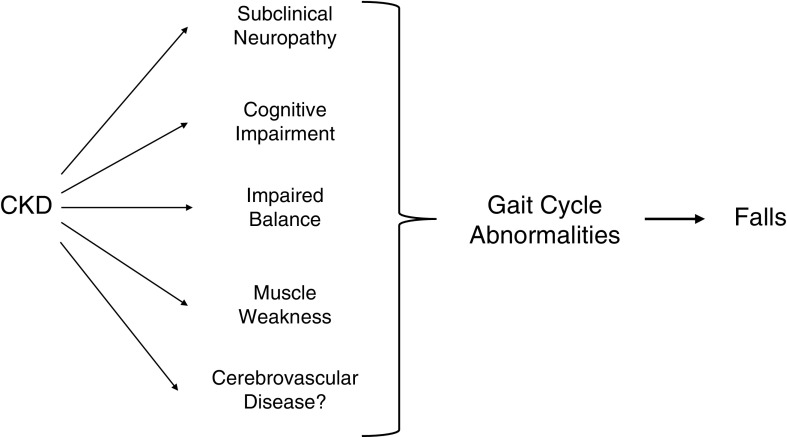

In CKD, as in the elderly, slower gait speed is associated with worse outcomes (4,14), but whether other gait abnormalities are present has not been examined. As several sequelae of CKD could affect gait, we hypothesized that CKD is associated with measurable disturbances in gait, and that these would translate into clinical gait abnormalities that contribute to fall risk (Figure 1). Because gait abnormalities are modifiable (15,16), this would have direct clinical relevance.

Figure 1.

Gait cycle abnormalities may increase fall risk in CKD. Gait cycle abnormalities could be present in older adults with CKD because of several sequelae of CKD that affect physical function. If present, gait cycle abnormalities could be an important contributor to fall risk. *The presence of cerebrovascular disease was not directly tested in this study.

Materials and Methods

Study Population

The Central Control of Mobility in Aging (CCMA) study investigates mobility and risks associated with mobility disability in older adults (17). Participants were recruited from a population-list of residents in lower Westchester County, New York, from June 2011 to October 2017. Individuals eligible for the study were those aged 65 years and older. Exclusion criteria included inability to speak English, inability to ambulate independently, presence of dementia, significant loss of vision or hearing, history of neurologic or psychiatric disorders, recent or anticipated medical procedures that may affect mobility, and current hemodialysis. Participants were evaluated annually. The study protocols for the CCMA study were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine and all participants provided written informed consent.

Collection of blood samples was incorporated into the CCMA protocol in July 2013. Our analysis includes participant recruitment and follow-up visits conducted through June 2017, at which time 350 out of 586 participants had blood samples collected. Of the 236 without blood samples, 125 had left the study before July 2013, and 110 did not consent to collection of blood samples. Baseline characteristics did not differ between participants with and without blood samples (Supplemental Table 1). All participants with laboratory test results had serum creatinine values available for the calculation of eGFR. For our analyses, we used gait parameters measured, and comorbidity and medication data collected, during the same visit in which laboratory test samples were drawn. Exclusion criteria for this study included lack of a gait assessment during the same visit as the sample collection (n=1) and missing data for covariates of interest including race, body mass index (BMI), and history of falls (n=19). The final cohort included 330 participants.

Study Design

Information regarding participants’ demographic information, medications, and comorbidities, including physician diagnosed lung diseases, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, cancer, neurologic diseases, depression, and arthritis, were collected using structured medical questionnaires. Participants were asked if they became lightheaded or dizzy when standing. Cardiovascular disease was defined as a history of angina, myocardial infarction, or congestive heart failure. The presence of neuropathy was determined by a comprehensive neurologic examination performed by study clinicians. The Michigan Neuropathy Screening Instrument questionnaire was used to assess neuropathic symptoms (range 0–15, lower better) (18). The Michigan Neuropathy Screening Instrument is a well validated instrument and the questionnaire performs as well as the examination component for predicting clinical neuropathy (19,20). General mental status was measured using the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (21). Lower extremity functioning was tested using the Short Physical Performance Battery that incorporates gait speed, chair rise, and balance tasks (range 0–12, higher better) (22). The unipedal stance test, a sensitive test of balance, measures the time participants can stand on one self-selected leg without support for a maximum of 30 seconds (23). Somatosensory sensitivity (vibration threshold) was measured in microns and assessed using the Vibratron II manufactured by Physitemp Instruments Inc. (24). The procedure, using a standardized forced-choice protocol, has been described previously (25). Grip strength was measured as the maximum voluntary contraction in the dominant hand with a Jamar Dynamometer over three trials, and the highest value was recorded. Knee extensor strength was measured using a hand-held dynamometer (Lafayette Manual Muscle Test System; Lafayette Instrument Company, Lafayette, IL) with 90 degrees of knee flexion. The maximum value of three trials was recorded. eGFR was calculated using the creatinine-based CKD Epidemiology Collaboration equation (26, 27). Serum creatinine was measured by an IDMS-traceable modified kinetic Jaffé reaction (28). CKD was defined as an eGFR <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (29).

Gait Assessment

Quantitative Assessment.

The gait cycle describes the time between succeeding foot contacts of the same limb. It is subdivided into two main phases, the swing phase and the stance phase, for each limb. The swing phase describes the time between one foot leaving the ground and the same foot making contact with the ground again. The stance phase describes the time when that foot is on the ground. The double-support phase is a subset of the stance phase, during which both feet are on the ground at the same time. Quantitative gait data describing aspects of the gait cycle were obtained using a 20-foot instrumental computerized walkway with embedded pressure sensors operated by the GAITRite system (CIR Systems, Havertown, PA). The GAITRite system is a validated tool for quantitative measurement of gait, with excellent reported reliability (30–32). Gait markers were computed using the mean of two trials conducted while participants walked on the mat at their everyday pace. High reliability has been reported for this assessment (33,34). Slow and very slow gait speed were defined using recommended cutoff scores as ≤0.8 and ≤0.6 m/s, respectively (35,36).

Clinical Assessment.

Gait was evaluated as part of the standard neurologic examination by study clinicians (neurologists) who were blinded to CKD status and laboratory test results. Study clinicians observed gait patterns while participants walked up and down at their normal pace in a well lit hallway, and classified them as neurologic (hemiparetic, neuropathic, ataxic, frontal, Parkinsonian, spastic, or unsteady) or non-neurologic (due to causes such as arthritis or cardiac disease). Descriptions of each neurologic gait phenotype, including videos, have been previously described (13). Study clinicians also marked the presence or absence of individual neurologic gait signs such as short steps, sway while walking, foot drop, etc. This was done to capture neurologic signs that might not fit with a specific neurologic gait subtype; for instance, foot drop in a patient with Parkinsonian gait. These clinical assessments have good inter-rater reliability: percent agreement for the presence of neurologic gait ranged from 0.6 to 0.8 (13,37). They also have predictive validity: abnormal neurologic gait phenotypes diagnosed in this manner predict the risk of dementia, institutionalization, and death (13,38).

Falls Assessment

Participants were interviewed in-person on an annual basis and every 2–3 months by telephone regarding new falls, using a standardized questionnaire to ensure consistency between interviews and interviewers. Falls were defined as coming down on the floor or other lower level, not due to a major intrinsic or extrinsic event (39). For any fall, participants were asked about associated injuries, including fractures, bruises, lacerations, or other injuries. An injurious fall was defined as a fall resulting in any injury. We reported excellent test-retest reliability for fall self-reports using this protocol (12).

Statistical Analyses

Baseline characteristics were compared between participants with and without CKD using chi-squared or Fisher exact tests for categorical variables, and two-tailed t tests or Wilcoxon rank-sum tests for continuous variables. Linear regression models were created to examine associations of eGFR with quantitative gait markers. Covariates were chosen a priori as potential confounders of the association of kidney function with gait abnormalities, and included age, sex, race, education, BMI, neuropathy, and number of comorbidities. Because graphical assessments suggested a threshold relationship, associations with continuous eGFR were examined by constructing linear splines with a knot at an eGFR of 60 ml/min per 1.73 m2. A linear model of the association of eGFR with each gait marker for eGFR <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 was deemed appropriate on the basis of graphical assessment using restricted cubic splines to model the relationship.

We performed a causal mediation analysis to determine whether individual gait parameters mediated the association of eGFR with gait speed. Analyses were performed as per Vanderweele (40) using the “paramed” module in Stata (41). As there was no evidence of an interaction between eGFR and any of the gait parameters, results are presented for models that do not specify an interaction.

Cox proportional hazards models were created to examine the risk of falls. These were adjusted for age, sex, race, BMI, neuropathy, medication count, number of comorbidities, history of falling, and gait speed, and were stratified by educational status. Participants not experiencing a fall were censored at the time of their last follow-up interview. The proportional hazards assumption was tested by visual inspection of log-log plots and calculation of scaled Schoenfeld residuals. Injurious falls, for which recall bias may be less of a concern, were examined as a secondary outcome. Effect modification was tested by including multiplicative interaction terms in the model. All analyses were performed using Stata 13.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). A P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Sensitivity Analyses

Given the possible contribution of polypharmacy among patients with CKD, we specifically examined confounding by medications. As diabetes severity and complications and comorbidity burden might differ between people with and without CKD, we repeated our analyses among the subgroup of participants without diabetes, and in a subgroup with low comorbidity burden. We also excluded those with neuropathy (diagnosed by study clinicians) to determine if our findings were informative even among participants without this clinical diagnosis.

Results

Participant Characteristics

Participants with CKD were older and more likely to have cardiovascular disease than those without CKD (Table 1). Diabetes was present in 20% of the cohort, but its prevalence did not differ between the two groups nor did that of other comorbidities. Neuropathy status did not differ between CKD and non-CKD on the basis of study clinician diagnosis or symptom burden, although vibration threshold was higher among participants with CKD. Participants with CKD exhibited worse general mental status and physical functioning, including lower extremity performance, balance, and grip strength, but did not differ in their self-reported history of falls.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics by CKD status

| Characteristic | No CKD | CKD |

|---|---|---|

| (n=196) | (n=134) | |

| Age, yra | 76±6 | 81±7 |

| Women, n (%) | 109 (56) | 68 (51) |

| Race, n (%) | ||

| White | 148 (76) | 109 (81) |

| Black | 41 (21) | 23 (17) |

| Other | 7 (4) | 2 (2) |

| Education, n (%) | ||

| High school or less | 61 (31) | 44 (33) |

| College | 82 (42) | 63 (47) |

| Postgraduate | 53 (27) | 27 (20) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 28.5±7.2 | 29.0±5.4 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 36 (18) | 29 (22) |

| Neuropathy, n (%) | 22 (11) | 15 (11) |

| Peripheral arterial disease, n (%) (n=327) | 7 (4) | 1 (0.8) |

| Hypertension, n (%) (n=329) | 114 (59) | 85 (63) |

| Stroke, n (%) (n=329) | 4 (2) | 3 (2) |

| Cardiovascular disease, n (%) | 7 (4) | 16 (12) |

| Comorbidities (global health score), n (%) | ||

| 0 | 40 (20) | 15 (11) |

| 1 | 57 (29) | 41 (31) |

| 2 | 65 (33) | 45 (34) |

| 3+ | 34 (17) | 33 (25) |

| Medication count | 4 (2–6) | 5 (3–7) |

| Antidepressant use, n (%) | 12 (6) | 11 (8) |

| Mood stabilizer use, n (%) | 10 (5) | 7 (5) |

| Opioid use, n (%) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.8) |

| Other psychiatric medication use, n (%) | 4 (2) | 4 (3) |

| Dizziness upon standing, n (%)b | 12 (6) | 6 (4) |

| eGFR, ml/min per 1.73 m2 | 76±10 | 45±11 |

| History of falls, n (%) | 117 (60) | 83 (62) |

| Dependence in 2+ ADLs, n (%) (n=327) | 3 (2) | 6 (5) |

| General mental status, RBANS total score | 94.0±12.9 | 90.7±12.4 |

| Michigan neuropathy score (n=301)c | 1 (0–2) | 1 (0–2) |

| Vibration threshold, microns (n=331) | 6.8±3.6 | 7.9±4.4 |

| SPPB, points (n=328) | 11 (9–11) | 9 (8–11) |

| Sit to stand points, n (%) (n=328)d | ||

| 0 | 18 (9) | 13 (10) |

| 1 | 18 (9) | 21 (16) |

| 2 | 40 (21) | 31 (23) |

| 3 | 54 (28) | 1 (31) |

| 4 | 65 (33) | 27 (20) |

| Balance test points, n (%) (n=328)d | ||

| 0 | 2 (1) | 2 (2) |

| 1 | 3 (2) | 4 (3) |

| 2 | 17 (9) | 24 (18) |

| 3 | 27 (14) | 27 (20) |

| 4 | 146 (75) | 76 (57) |

| Unipedal stance test, sec (n=203) | 10.0 (4.5–27.9) | 7.0 (3.4–15.9) |

| Grip strength, kg (n=226) | 25.2±8.6 | 22.9±8.4 |

| Quadriceps strength, kg (n=291) | 28.4±11.2 | 27.0±12.3 |

| Quantitative gait markers | ||

| Gait speed, cm/s | 100.9±22.7 | 89.9±22.9 |

| Stride length, cm | 117.5±18.8 | 107.4±21.4 |

| Swing, % | 34.3±2.8 | 32.9±3.3 |

| Double support, % | 31.1±5.3 | 33.6±5.8 |

| Stride length variability, SD | 3.5±2.0 | 3.6±1.9 |

| Cadence, steps/min | 102.8±13.0 | 100.2±10.8 |

Data are expressed as mean±SD or median (interquartile range) for continuous variables. Percentages may not sum to 100% because of rounding. ADL, activities of daily living; RBANS, Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status; SPPB, Short Physical Performance Battery.

CKD defined as eGFR <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2.

Yes or maybe when questioned about being lightheaded or dizzy when standing.

From Michigan Neuropathy Screening Instrument questionnaire.

Sit-to-stand points and balance test points are derived from components of the SPPB.

Quantitative Gait Analysis

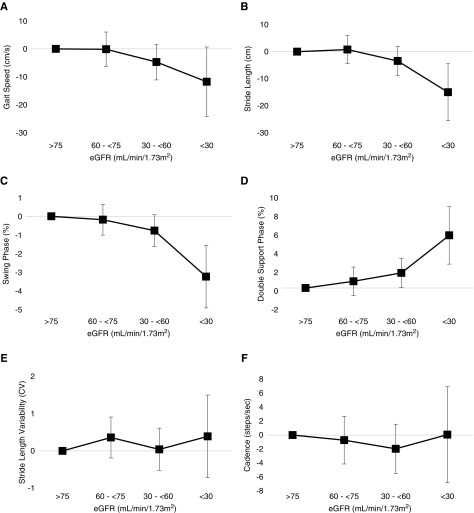

Several quantitative gait markers differed according to CKD status. Participants with CKD had slower gait speed, shorter stride length, reduced time in the swing phase, increased time in the double-support phase, and slower cadence (Table 1). With the exception of cadence, these differences persisted after adjusting for age and sex, and the largest differences in gait markers were present among those with the most advanced CKD (Figure 2). Stride length variability did not differ between CKD and non-CKD.

Figure 2.

Lower eGFR is associated with greater abnormalities in quantitative gait markers. Linear regression models were used to calculate age- and sex-adjusted differences in gait speed (A), stride length (B), percent of the gait cycle spent in the swing phase (C) and double-support phase (D), stride length variability (E), and cadence (F). Reference category for each comparison is eGFR >75 ml/min per 1.73 m2.

After multivariable adjustment, lower eGFR was linearly associated with greater abnormalities in gait speed, stride length, and the percent of the gait cycle in the swing and double-support phases, and there was a threshold relationship with kidney function (Table 2). At an eGFR <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2, each 10 ml/min per 1.73 m2 lower eGFR was associated with 3.3 cm/sec (95% confidence interval [95% CI], 0.6 to 5.9) slower gait speed, 3.6 cm (95% CI, 1.4 to 5.8) shorter stride length, 0.7% (95% CI 0.3 to 1.0) less time in the swing phase of the gait cycle, and 1.1% (95% CI, 0.5 to 1.7) longer time in the double-support phase. No significant relationship was observed between eGFR and stride length variability or cadence, and eGFR was not associated with quantitative gait markers among participants with an eGFR ≥60 ml/min per 1.73 m2. Results were not changed by additional adjustment for number of medications, nor by restriction to participants without diabetes or without neuropathy (Supplemental Table 2).

Table 2.

Associations of continuous eGFR with quantitative gait markers

| Gait Marker | eGFR ≥60 (n=196) | eGFR <60 (n=134) |

|---|---|---|

| Coefficient (95% CI) | Coefficient (95% CI) | |

| Age and sex adjustment, per 10 ml/min per 1.73 m2 higher eGFRa | ||

| Speed, cm/s | 0.3 (−2.3 to 2.9) | 3.6 (0.8 to 6.3) |

| Stride length, cm | −0.2 (−2.4 to 1.9) | 3.9 (1.6 to 6.1) |

| Swing, % | −0.01 (−0.4 to 0.3) | 0.7 (0.3 to 1.1) |

| Double support, % | −0.1 (−0.8 to 0.5) | −1.1 (−1.8 to −0.4) |

| Stride length variability, SD | −0.1 (−0.3 to 0.2) | 0.1 (−0.2 to 0.3) |

| Cadence, steps/min | 0.4 (−1.0 to 1.9) | 0.4 (−1.2 to 1.9) |

| Multivariable model, per 10 ml/min per 1.73 m2 higher eGFRb | ||

| Speed, cm/s | −0.1 (−2.6 to 2.4) | 3.3 (0.6 to 5.9) |

| Stride length, cm | −0.7 (−2.7 to 1.4) | 3.6 (1.4 to 5.8) |

| Swing, % | −0.2 (−0.5 to 0.1) | 0.7 (0.3 to 1.0) |

| Double support, % | 0.2 (−0.4 to 0.8) | −1.1 (−1.7 to −0.5) |

| Stride length variability, SD | −0.1 (−0.3 to 0.1) | 0.05 (−0.2 to 0.3) |

| Cadence, steps/min | 0.4 (−1.0 to 1.8) | 0.4 (−1.1 to 1.9) |

95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

Linear splines for eGFR constructed with knot placed at 60 ml/min per 1.73 m2.

Multivariable model adjusted for age, sex, race, education, body-mass index, neuropathy, and number of comorbidities.

Next, using causal mediation analysis, we sought to determine if these newly identified gait cycle abnormalities could explain slow gait speed in patients with CKD. We found that the association of eGFR with gait speed was completely mediated by stride length and time in the swing and double-support phases of the gait cycle (Table 3; see Supplemental Appendix for additional explanation). There was no evidence that other gait parameters, such as cadence, were mediators. This indicates that quantifiable gait disturbances, specifically shorter stride length and altered time spent in each phase of the gait cycle, explain the reduction in gait speed among people with CKD.

Table 3.

Causal mediation analysis examining gait markers as mediators of gait speed in individuals with CKD

| Controlled Direct Effect | Natural Indirect Effect | Total Effect | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gait Marker | Estimate (95% CI) | Estimate (95% CI) | Estimate (95% CI) |

| Stride length, cm | 14.0 (−24.9 to 52.9) | −109.3 (−176.5 to −42.2) | −95.3 (−172.3 to −18.3) |

| Swing, % | 18.3 (−36.2 to 72.9) | −113.6 (−170.5 to −56.7) | −95.3 (−172.3 to −18.3) |

| Double support, % | 8.2 (−42.4 to 58.8) | −103.5 (−163.1 to −43.9) | −95.3 (−172.3 to −18.3) |

| Stride length variability, SD | −96.6 (−173.4 to −19.8) | 1.2 (−5.6 to 8.1) | −95.3 (−172.3 to −18.3) |

| Cadence, steps/min | −80 0.5 (−131.4 to −29.7) | −14.8 (−72.6 to 43.1) | −95.3 (−172.3 to −18.3) |

CKD defined as eGFR <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2. Models adjusted for age, sex, race, education, body-mass index, self-reported neuropathy, and number of comorbidities. The total effect (TE) represents the association of eGFR with gait speed in a multivariable model that does not include the mediator (each gait marker). The TE is decomposed into effects that work through the mediator and effects that are independent of the mediator. The magnitude of the eGFR-gait speed pathway that works through the mediator is called the natural indirect effect, and the magnitude of the pathway that is independent of the mediator is called the controlled direct effect. For stride length, swing, and double support, comparison of the natural indirect effect and the TE is consistent with complete mediation. Because of the presence of inconsistent mediation (the direct and indirect effects are in opposite directions), the proportion mediated is not presented. There is no evidence of mediation through stride length variability or cadence. 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

As other aspects of physical function are also affected by kidney disease, we examined whether these could explain the quantitative gait abnormalities in participants with CKD (Table 4). Adjustment, separately, for measures of neuropathy, cognitive function, and muscle strength each attenuated the associations of eGFR with gait markers, but most associations of eGFR with each gait marker remained statistically significant (Table 4, upper panel). In a combined model adjusting for all of these parameters simultaneously, the magnitude of attenuation was substantially greater, and the association of eGFR with each gait marker was no longer statistically significant. This effect was not observed after adjustment for unipedal stance time, indicating that the gait alterations were not simply due to dysregulated static postural and balance control. Adjustment for vibration threshold (Table 4, bottom panel) and Michigan score produced similar estimates, indicating that an objective measure of sensory nerve function was not more informative than patient-reported symptoms.

Table 4.

Associations of eGFR with gait markers among individuals with CKD after addition of possible mediators to multivariable model

| Gait Marker | Multivariable Model | + Michigan Score | + RBANS Total Score | + Grip Strength | + Michigan Score, RBANS, Grip Strength | + Unipedal Stance (n=109) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subgroup with eGFR <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 and complete data for Michigan score, RBANS Index, and grip strength (n=121) | ||||||

| Speed, cm/s | 3.7 (0.9–6.4) | 2.6 (−0.7–6.0) | 2.6 (−0.1–5.3) | 2.8 (−0.005–5.5) | 0.7 (−2.6–4.1) | 2.8 (−0.2–5.8) |

| P=0.01 | P=0.13 | P=0.06 | P=0.05 | P=0.68 | P=0.07 | |

| Stride length, cm | 4.1 (1.8–6.4) | 2.9 (−0.1–5.8) | 3.3 (1.0–5.5) | 3.2 (0.9–5.5) | 1.0 (−1.9–4.0) | 3.1 (0.6–5.6) |

| P=0.001 | P=0.05 | P=0.01 | P=0.01 | P=0.49 | P=0.02 | |

| Swing, % | 0.8 (0.4–1.1) | 0.6 (0.1–1.0) | 0.7 (0.3–1.0) | 0.7 (−0.3–1.0) | 0.4 (−0.1–0.8) | 0.5 (0.2–0.9) |

| P <0.001 | P=0.01 | P <0.001 | P <0.001 | P=0.10 | P=0.004 | |

| Double support, % | −1.2 (−1.9 to −0.6) | −0.8 (−1.6 to −0.01) | −1.0 (−1.7 to −0.4) | −1.1 (−1.7 to −0.4) | −0.3 (−1.1 to −0.5) | −1.0 (−1.7 to −0.3) |

| P <0.001 | P=0.05 | P=0.002 | P=0.001 | P=0.40 | P=0.002 | |

| Stride length variability, SD | 0.1 (−0.2–0.3) | 0.2 (−0.1–0.5) | 0.1 (−0.2–0.3) | 0.1 (−0.2–0.3), | 0.2 (−0.2–0.5) | −0.01 (−0.3–0.3) |

| P=60 | P=0.25 | P=0.69 | P=0.59 | P=0.32 | P=0.96 | |

| Cadence, steps/min | 0.3 (−1.2–1.8) | 0.3 (−1.5–2.1) | −0.1 (−1.6–1.4) | 0.1 (−1.4–1.7) | −0.05 (−1.9–1.8) | 0.4 (−1.2–2.1) |

| P=0.69 | P=0.77 | P=0.92 | P=0.87 | P=0.96 | P=0.64 | |

| Subgroup with eGFR <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 and vibration threshold data (n=92) | Multivariable Model | + Vibration Threshold | ||||

| Speed, cm/s | 2.6 (−0.7–5.9) | 2.3 (−1.0–5.6) | ||||

| P=0.12 | P=0.17 | |||||

| Stride length, cm | 3.0 (0.2–5.8) | 2.7 (−0.1–5.6) | ||||

| P=0.04 | P=0.06 | |||||

| Swing, % | 0.6 (0.1–1.0) | 0.5 (0.1–0.9) | ||||

| P=0.01 | P=0.02 | |||||

| Double support, % | −0.9 (−1.7 to −0.1) | −0.8 (−1.5–0.01) | ||||

| P=0.03 | P=0.05 | |||||

| Stride length variability, SD | 0.2 (−0.1–0.5) | 0.3 (−0.1–0.6) | ||||

| P=0.22 | P=0.12 | |||||

| Cadence, steps/min | 0.2 (−1.6–2.0) | 0.1 (−1.7–1.9) | ||||

| P=0.80 | P=0.90 |

Data are displayed as coefficient (95% CI). CKD defined as eGFR <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2. Coefficients calculated using linear regression models with linear splines for eGFR constructed with knot placed at 60 ml/min per 1.73 m2. Data are presented only for eGFR <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2. All models adjusted for variables in multivariable model plus additional variable(s) indicated. Multivariable model adjusted for age, sex, race, education, body-mass index, neuropathy, and number of comorbidities. RBANS, Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status.

Clinical Gait Phenotypes and the Risk of Falls

We hypothesized that the differences in quantitative gait markers would translate into clinical gait abnormalities that could be detected by trained examiners. Indeed, consistent with the quantitative gait findings, marked sway and loss of balance with straight or tandem walking were significantly more common among individuals with CKD, as were short steps (Supplemental Table 3). There was no difference in the prevalence of a wide-based gait, foot drop or shuffling. Festination was not observed in any participants. Among the 87 participants with CKD and any one of these gait abnormalities (marked sway, loss of balance, or short steps), only 45 were judged by a study clinician as having a clinically recognized neurologic gait phenotype (26 unsteady, six frontal, two Parkinsonian, one spastic, eight neuropathic, and two other gait subtypes). The other 42 patients had individual neurologic signs that were not considered to fit with defined neurologic gait subtypes by the study clinicians. Therefore, we defined a gait phenotype on the basis of the presence of individual gait signs (regardless of neurologic gait subtype) as (1) short steps and/or (2) marked sway or loss of balance with straight or tandem walking, and tested its prognostic value related to incident falls. Compared with people without CKD or the gait phenotype, those with both CKD and the gait phenotype had the greatest abnormalities in gait speed, stride length, and time in the swing and double-support phases of the gait cycle (Supplemental Table 4). Among people with CKD and the gait phenotype, the prevalence of slow and very slow gait speed was 46% (n=40) and 11% (n=10), respectively. Overall, 294 participants (89%) had clinical gait exams and subsequent follow-up interviews with falls assessments. Over a median follow-up time of 22.9 months (interquartile range, 10.6–35.6), 154 participants experienced a fall. Compared with participants without CKD and without this gait phenotype, participants with CKD and with the gait phenotype had higher risk of falling, whereas those without the phenotype did not (Table 5, upper panel) (P value for interaction of CKD status and gait phenotype =0.01). The gait phenotype was independently associated with the risk of falls even among participants without diabetes or neuropathy (Table 5, second panel) and among participants with no or one comorbidity (Table 5, third panel), and the risk estimate was similar after excluding participants identified as having a neurologic gait phenotype (Table 5, fourth panel). In addition, among participants with CKD, the phenotype was associated with the risk of injurious falls (Table 5, bottom panel).

Table 5.

Risk of falling by CKD status and clinical gait phenotype

| Outcome | Age Adjustedb | Multivariable Modelc | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Eventsa | HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | |

| Any fall | |||

| Full cohort (n=294) | |||

| No CKD, no gait phenotype (n=95) | 46 | Ref | Ref |

| No CKD, +gait phenotype (n=76) | 35 | 0.93 (0.59 to 1.47) | 0.97 (0.61 to 1.55) |

| CKD, no gait phenotype (n=40) | 18 | 0.79 (0.45 to 1.36) | 0.71 (0.40 to 1.25) |

| CKD, +gait phenotype (n=83) | 55 | 1.63 (1.04 to 2.53) | 1.72 (1.06 to 2.81) |

| Excluding diabetes and neuropathy (n=222) | |||

| No CKD, no gait phenotype (n=71) | 32 | Ref | Ref |

| No CKD, +gait phenotype (n=60) | 27 | 0.97 (0.57 to 1.65) | 0.97 (0.56 to 1.69) |

| CKD, no gait phenotype (n=27) | 12 | 0.88 (0.45 to 1.72) | 0.84 (0.42 to 1.68) |

| CKD, +gait phenotype (n=64) | 44 | 1.77 (1.05 to 3.00) | 1.84 (1.03 to 3.30) |

| Restricted to 0 or 1 comorbidity (n=135) | |||

| No CKD, no gait phenotype (n=44) | 21 | Ref | Ref |

| No CKD, +gait phenotype (n=41) | 14 | 0.68 (0.34 to 1.37) | 0.68 (0.32 to 1.46) |

| CKD, no gait phenotype (n=20) | 9 | 0.93 (0.43 to 2.04) | 1.06 (0.46 to 2.43) |

| CKD, +gait phenotype (n=30) | 21 | 2.08 (1.01 to 4.29) | 2.37 (1.01 to 5.56) |

| Restricted to participants without a neurologic gait phenotype (n=203) | |||

| No CKD, no gait phenotype (n=88) | 43 | Ref | Ref |

| No CKD, + gait phenotype (n=38) | 18 | 0.99 (0.57 to 1.72) | 0.91 (0.51 to 1.63) |

| CKD, no gait phenotype (n=36) | 18 | 0.86 (0.49 to 1.48) | 0.79 (0.44 to 1.43) |

| CKD, + gait phenotype (n=41) | 27 | 1.76 (1.09 to 2.86) | 1.85 (0.99 to 3.44) |

| Injurious falls | |||

| Full cohort (n=294) | |||

| No CKD, no gait phenotype (n=95) | 12 | Ref | Ref |

| No CKD, +gait phenotype (n=76) | 9 | 1.07 (0.44 to 2.58) | 1.39 (0.54 to 3.58) |

| CKD, no gait phenotype (n=40) | 6 | 1.16 (0.43 to 3.13) | 0.99 (0.35 to 2.82) |

| CKD, +gait phenotype (n=83) | 20 | 2.61 (1.16 to 5.89) | 2.72 (1.09 to 6.79) |

HR, hazard ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; Ref, reference value; +, positive for gait phenotype; IQR, interquartile range.

Full cohort (n=294). Any fall: 154 falls (52.4%), median follow-up time 22.9 months (IQR, 10.6–35.6); injurious falls: 47 falls (16.0%), median follow-up time 34.8 months (IQR, 24.1–39.2).

CKD defined as eGFR <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2. Gait phenotype defined as the presence of short steps or marked sway or loss of balance with straight or tandem walking. P value for interaction of CKD status and gait phenotype =0.01.

Multivariable model adjusted for age, sex, race, body mass index, neuropathy, medication count, number of comorbidities, history of falling, gait speed, and stratified by educational status.

We performed several additional analyses to determine why the gait phenotype was associated with falls only among participants with CKD. Greater severity (i.e., more characteristics) of the gait phenotype was associated with the presence of CKD (Supplemental Table 5), and only in participants with CKD, with a higher risk of falling (Supplemental Table 6; P for interaction by CKD status =0.03). Phenotype severity was not associated with fall risk in participants without CKD: whereas in the group with CKD, each characteristic of the gait phenotype appeared to contribute to fall risk, this was not the case in the group without CKD, where the direction of association of short steps was toward a reduced risk of falling (Supplemental Table 7; P for interaction by CKD status =0.01).

Discussion

Among community-dwelling older adults, gait abnormalities were more common in people with CKD than in those without, and were independently associated with the severity of kidney dysfunction. In addition to slow gait speed, older persons with CKD had other measurable disturbances in gait; the presence of slower gait speed was explained by these alterations in the timing of the gait cycle and stride length. Furthermore, abnormal gait signs detected on clinical examination identified participants with CKD at higher risk of experiencing a fall.

This has important implications: Fall-related injuries hasten the development of disability (42), reduce the likelihood of receiving a kidney transplant (43), and place a large financial burden on the health care system (44,45). Thus, identifying individuals at risk for falls is an important goal and could facilitate early interventions in patients with CKD. One useful indicator is slow gait speed; it has been associated with the risk of falls in older adults and is recommended as part of their routine care (36), and would likely have utility in CKD care as well (4). Abnormalities in the spatiotemporal characteristics of gait are also associated with fall risk in older adults, independent of gait speed (12). Our data indicate that spatiotemporal gait abnormalities may also help identify at-risk patients with CKD: the majority with the gait phenotype we studied did not have slow gait speed, and thus would not be flagged using gait speed alone as a screening tool. This approach would require further testing and validation to determine its utility.

The degree to which this gait phenotype is unique to CKD is unclear. Shortened step length has been reported in patients with advanced heart failure (46); these patients also have increased gait variability (47), which we did not observe among participants with CKD. Mild cognitive impairment syndrome has been associated with slower gait speed and shorter stride length (48). Similar gait abnormalities may be seen with neurologic diseases such as stroke, parkinsonism, and dementia, but these diseases are typically associated with well-defined neurologic gait phenotypes (13). In contrast, only 52% of our 87 participants with CKD and the gait phenotype (diagnosed by individual gait signs) had specific neurologic gait subtypes diagnosed by clinicians. Of the neurologic gait phenotypes, there is significant overlap between the phenotype definition we used and that of unsteady gait. The impaired balance component of our phenotype definition (marked sway/loss of balance) was clearly associated with fall risk, but other components of gait may also be involved. In particular, shortened steps appeared to be associated with fall risk independently of the balance component. Our data do not enable us to comment on whether this was due to differences in the ability to attend to step patterns in people with and without CKD, or an alternative explanation. It will be important to investigate if this finding is replicated in other cohorts.

In attempting to determine the contributors to these gait abnormalities, we considered multiple domains: neuropathy, cognitive function, muscle strength, vascular disease, and balance. None of these, in isolation, explained our findings. Although a diagnosis of neuropathy was equally common in people with and without CKD, vibration threshold was higher in those with CKD, suggesting subclinical neuropathy. The presence of subclinical neuropathy is supported by a recent study from the Health, Aging and Body Composition cohort, which found that CKD was associated with asymptomatic peripheral sensory nerve impairment (49). In our cohort, adjustment for both subjective and objective measures of neuropathy attenuated, but did not completely explain, the associations of eGFR with gait markers. We did not have a detailed assessment of vascular function, but peripheral vascular disease seems an unlikely explanation for our findings, given that very few participants carried this diagnosis. Subclinical cerebrovascular disease, however, may be a contributing factor, as unsteady gait is associated with the development of vascular dementia (13), and adjustment for cognitive function somewhat attenuated our estimates. A previous study found impaired postural control among patients receiving hemodialysis (50); however, our results remained significant after adjustment for unipedal stance time as a measure of balance. Thus, no single factor explains these gait abnormalities; rather, they may reflect the integration of multiple sequelae that arise either directly from progressive kidney disease or as a result of shared risk factors with CKD.

Several limitations of our analyses should be considered. Because of the lack of additional laboratory data, we defined CKD on the basis of one measure of serum creatinine, as prior studies have done (1). In addition, no information on albuminuria was collected. Future studies can determine whether quantifiable gait abnormalities are present in earlier CKD. As comorbidities were self-reported, residual confounding remains a possibility. However, our results were unchanged after excluding participants with diabetes or neuropathy. The low prevalence of comorbidities could have occurred because of enrollment of a relatively healthy cohort, which is supported by the relatively low number of medications. This would reduce the generalizability of our findings. Finally, as this was a cross-sectional analysis of quantitative gait markers, we are unable to comment on the temporal evolution of gait abnormalities in CKD, and cannot rule out reverse causality, specifically that these disturbances may contribute to the development or progression of CKD.

In summary, CKD is associated with quantifiable gait abnormalities: These are present in individuals with mild to moderate CKD; are of greatest severity in those with more advanced CKD; explain the observation that lower eGFR is associated with slower gait speed; and manifest in a clinically detectable gait phenotype, identified by the presence of easily identifiable individual clinical signs, that is associated with fall risk. Future studies should determine whether these gait abnormalities contribute to the development of mobility impairment in patients with CKD, and ultimately, if quantitative gait assessments and clinical gait examinations have a role in the care of patients with CKD.

Disclosures

Dr. Abramowitz, Ms. Ayers, Dr. Tran, and Dr. Verghese have nothing to disclose.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants K23DK099438, R01AG036921, and R01AG044007 from the National Institutes of Health.

This study was presented in abstract form at the 2018 ASN Kidney Week in San Diego, CA, October 25–28, 2018 (SA-PO716: Quantitative Gait Abnormalities and Risk of Falls in CKD).

Footnotes

J.V. and M.K.A. contributed equally to this work.

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

See related editorial, “Targeting Fall Risk in CKD,” on pages 965–966.

Supplemental Material

This article contains the following supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.13871118/-/DCSupplemental.

Supplemental Appendix. Causal mediation analysis interpretation.

Supplemental Table 1. Characteristics at enrollment visit in participants with and without blood samples.

Supplemental Table 2. Associations of continuous eGFR with quantitative gait markers after adjustment for medications or exclusion of diabetes or neuropathy.

Supplemental Table 3. Clinical gait abnormalities by CKD status.

Supplemental Table 4. Associations of clinical gait phenotype and CKD status with quantitative gait markers.

Supplemental Table 5. Odds ratio for CKD by gait severity score.

Supplemental Table 6. Risk of falling by gait severity score and CKD status.

Supplemental Table 7. Risk of falling by gait characteristic and CKD status.

References

- 1.Coresh J, Selvin E, Stevens LA, Manzi J, Kusek JW, Eggers P, van Lente F, Levey AS: Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in the United States. JAMA 298: 2038–2047, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murphy D, McCulloch CE, Lin F, Banerjee T, Bragg-Gresham JL, Eberhardt MS, Morgenstern H, Pavkov ME, Saran R, Powe NR, Hsu CY; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Chronic Kidney Disease Surveillance Team : Trends in prevalence of chronic kidney disease in the United States. Ann Intern Med 165: 473–481, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fried LF, Lee JS, Shlipak M, Chertow GM, Green C, Ding J, Harris T, Newman AB: Chronic kidney disease and functional limitation in older people: Health, aging and body composition study. J Am Geriatr Soc 54: 750–756, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roshanravan B, Robinson-Cohen C, Patel KV, Ayers E, Littman AJ, de Boer IH, Ikizler TA, Himmelfarb J, Katzel LI, Kestenbaum B, Seliger S: Association between physical performance and all-cause mortality in CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol 24: 822–830, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cook WL, Tomlinson G, Donaldson M, Markowitz SN, Naglie G, Sobolev B, Jassal SV: Falls and fall-related injuries in older dialysis patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 1: 1197–1204, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Plantinga LC, Patzer RE, Franch HA, Bowling CB: Serious fall injuries before and after initiation of hemodialysis among older ESRD patients in the United States: A retrospective cohort study. Am J Kidney Dis 70: 76–83, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nickolas TL, McMahon DJ, Shane E: Relationship between moderate to severe kidney disease and hip fracture in the United States. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 3223–3232, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tinetti ME, Williams CS: Falls, injuries due to falls, and the risk of admission to a nursing home. N Engl J Med 337: 1279–1284, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L, Simonsick EM, Salive ME, Wallace RB: Lower-extremity function in persons over the age of 70 years as a predictor of subsequent disability. N Engl J Med 332: 556–561, 1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Studenski S, Perera S, Patel K, Rosano C, Faulkner K, Inzitari M, Brach J, Chandler J, Cawthon P, Connor EB, Nevitt M, Visser M, Kritchevsky S, Badinelli S, Harris T, Newman AB, Cauley J, Ferrucci L, Guralnik J: Gait speed and survival in older adults. JAMA 305: 50–58, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Perera S, Patel KV, Rosano C, Rubin SM, Satterfield S, Harris T, Ensrud K, Orwoll E, Lee CG, Chandler JM, Newman AB, Cauley JA, Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L, Studenski SA: Gait speed predicts incident disability: A pooled analysis. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 71: 63–71, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Verghese J, Holtzer R, Lipton RB, Wang C: Quantitative gait markers and incident fall risk in older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 64: 896–901, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Verghese J, Lipton RB, Hall CB, Kuslansky G, Katz MJ, Buschke H: Abnormality of gait as a predictor of non-Alzheimer’s dementia. N Engl J Med 347: 1761–1768, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kutner NG, Zhang R, Huang Y, Painter P: Gait speed and mortality, hospitalization, and functional status change among hemodialysis patients: A US renal data system special study. Am J Kidney Dis 66: 297–304, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oh-Park M, Holtzer R, Mahoney J, Wang C, Verghese J: Effect of treadmill training on specific gait parameters in older adults with frailty: Case series. J Geriatr Phys Ther 34: 184–188, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tinetti ME, Kumar C: The patient who falls: “It’s always a trade-off”. JAMA 303: 258–266, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li C, Verghese J, Holtzer R: A comparison of two walking while talking paradigms in aging. Gait Posture 40: 415–419, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feldman EL, Stevens MJ, Thomas PK, Brown MB, Canal N, Greene DA: A practical two-step quantitative clinical and electrophysiological assessment for the diagnosis and staging of diabetic neuropathy. Diabetes Care 17: 1281–1289, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Albers JW, Herman WH, Pop-Busui R, Feldman EL, Martin CL, Cleary PA, Waberski BH, Lachin JM; Diabetes Control and Complications Trial/Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications Research Group : Effect of prior intensive insulin treatment during the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT) on peripheral neuropathy in type 1 diabetes during the Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications (EDIC) study. Diabetes Care 33: 1090–1096, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Herman WH, Pop-Busui R, Braffett BH, Martin CL, Cleary PA, Albers JW, Feldman EL; DCCT/EDIC Research Group : Use of the Michigan neuropathy screening instrument as a measure of distal symmetrical peripheral neuropathy in type 1 diabetes: Results from the diabetes control and complications trial/epidemiology of diabetes interventions and complications. Diabet Med 29: 937–944, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Randolph C, Tierney MC, Mohr E, Chase TN: The Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS): Preliminary clinical validity. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 20: 310–319, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guralnik JM, Simonsick EM, Ferrucci L, Glynn RJ, Berkman LF, Blazer DG, Scherr PA, Wallace RB: A short physical performance battery assessing lower extremity function: Association with self-reported disability and prediction of mortality and nursing home admission. J Gerontol 49: M85–M94, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hurvitz EA, Richardson JK, Werner RA: Unipedal stance testing in the assessment of peripheral neuropathy. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 82: 198–204, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gerr FE, Letz R: Reliability of a widely used test of peripheral cutaneous vibration sensitivity and a comparison of two testing protocols. Br J Ind Med 45: 635–639, 1988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dumas K, Holtzer R, Mahoney JR: Visual-somatosensory integration in older adults: Links to sensory functioning. Multisens Res 29: 397–420, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AF 3rd, Feldman HI, Kusek JW, Eggers P, Van Lente F, Greene T, Coresh J; CKD-EPI (Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration) : A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med 150: 604–612, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Levey AS, Stevens LA: Estimating GFR using the CKD Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) creatinine equation: More accurate GFR estimates, lower CKD prevalence estimates, and better risk predictions. Am J Kidney Dis 55: 622–627, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vaishya R, Arora S, Singh B, Mallika V: Modification of Jaffe’s kinetic method decreases bilirubin interference: A preliminary report. Indian J Clin Biochem 25: 64–66, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD Work Group. KDIGO 2012 clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int Suppl 3: 1–150, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 30.McDonough AL, Batavia M, Chen FC, Kwon S, Ziai J: The validity and reliability of the GAITRite system’s measurements: A preliminary evaluation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 82: 419–425, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Menz HB, Latt MD, Tiedemann A, Mun San Kwan M, Lord SR: Reliability of the GAITRite walkway system for the quantification of temporo-spatial parameters of gait in young and older people. Gait Posture 20: 20–25, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Webster KE, Wittwer JE, Feller JA: Validity of the GAITRite walkway system for the measurement of averaged and individual step parameters of gait. Gait Posture 22: 317–321, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Verghese J, Wang C, Lipton RB, Holtzer R, Xue X: Quantitative gait dysfunction and risk of cognitive decline and dementia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 78: 929–935, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Verghese J, Kuslansky G, Holtzer R, Katz M, Xue X, Buschke H, Pahor M: Walking while talking: Effect of task prioritization in the elderly. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 88: 50–53, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Bahat G, Bauer J, Boirie Y, Bruyere O, Cederholm T, Cooper C, Landi F, Rolland Y, Sayer AA, Schneider SM, Sieber CC, Topinkova E, Vandewoude M, Visser M, Zamboni M; Writing Group for the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People 2 (EWGSOP2), and the Extended Group for EWGSOP2 : Sarcopenia: Revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis. Age Ageing 48: 16–31, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cummings SR, Studenski S, Ferrucci L: A diagnosis of dismobility--giving mobility clinical visibility: A mobility working group recommendation. JAMA 311: 2061–2062, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Verghese J, Katz MJ, Derby CA, Kuslansky G, Hall CB, Lipton RB: Reliability and validity of a telephone-based mobility assessment questionnaire. Age Ageing 33: 628–632, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Verghese J, LeValley A, Hall CB, Katz MJ, Ambrose AF, Lipton RB: Epidemiology of gait disorders in community-residing older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 54: 255–261, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.The prevention of falls in later life. A report of the kellogg international work group on the prevention of falls by the elderly. Dan Med Bull 34[Suppl 4]: 1–24, 1987 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.VanderWeele TJ: Causal mediation analysis with survival data. Epidemiology 22: 582–585, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Emsley R, Liu H: PARAMED: Stata Module to Perform Causal Mediation Analysis Using Parametric Regression models. Boston, Boston College Department of Economics, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gill TM, Murphy TE, Gahbauer EA, Allore HG: The course of disability before and after a serious fall injury. JAMA Intern Med 173: 1780–1786, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Plantinga LC, Lynch RJ, Patzer RE, Pastan SO, Bowling CB: Association of serious fall injuries among United States end stage kidney disease patients with access to kidney transplantation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 628–637, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kim SM, Long J, Montez-Rath M, Leonard M, Chertow GM: Hip fracture in patients with non-dialysis-requiring chronic kidney disease. J Bone Miner Res 31: 1803–1809, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Burns ER, Stevens JA, Lee R: The direct costs of fatal and non-fatal falls among older adults - United States. J Safety Res 58: 99–103, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Davies SW, Greig CA, Jordan SL, Grieve DW, Lipkin DP: Short-stepping gait in severe heart failure. Br Heart J 68: 469–472, 1992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hausdorff JM, Forman DE, Ladin Z, Goldberger AL, Rigney DR, Wei JY: Increased walking variability in elderly persons with congestive heart failure. J Am Geriatr Soc 42: 1056–1061, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Verghese J, Robbins M, Holtzer R, Zimmerman M, Wang C, Xue X, Lipton RB: Gait dysfunction in mild cognitive impairment syndromes. J Am Geriatr Soc 56: 1244–1251, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Moorthi RN, Doshi S, Fried LF, Moe SM, Sarnak MJ, Satterfield S, Schwartz AV, Shlipak M, Lange-Maia BS, Harris TB, Newman AB, Strotmeyer ES: Chronic kidney disease and peripheral nerve function in the health, aging and body composition study. Nephrol Dial Transplant 34: 625–632, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shin S, Chung HR, Fitschen PJ, Kistler BM, Park HW, Wilund KR, Sosnoff JJ: Postural control in hemodialysis patients. Gait Posture 39: 723–727, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.