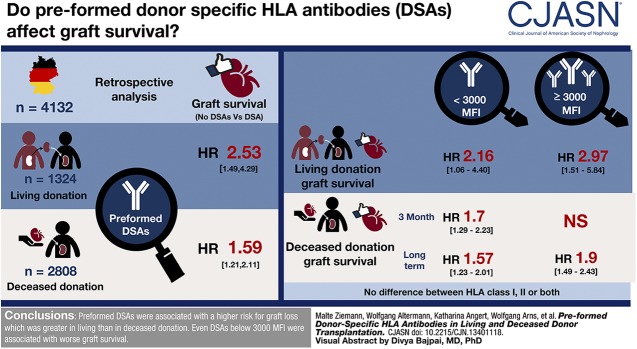

Visual Abstract

Keywords: kidney transplantation, preformed HLA antibodies, graft survival, donor-specific HLA antibodies, ABO-incompatible transplantation, Incidence, Prognosis, Fluorescence, Tissue Donors, Antibodies, HLA-A Antigens, Retrospective Studies

Abstract

Background and objectives

The prognostic value of preformed donor-specific HLA antibodies (DSA), which are only detectable by sensitive methods, remains controversial for kidney transplantation.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

The outcome of 4233 consecutive kidney transplants performed between 2012 and 2015 in 18 German transplant centers was evaluated. Most centers used a stepwise pretransplant antibody screening with bead array tests and differentiation of positive samples by single antigen assays. Using these screening results, DSA against HLA-A, -B, -C, -DRB1 and -DQB1 were determined. Data on clinical outcome and possible covariates were collected retrospectively.

Results

Pretransplant DSA were associated with lower overall graft survival, with a hazard ratio of 2.53 for living donation (95% confidence interval [95% CI], 1.49 to 4.29; P<0.001) and 1.59 for deceased donation (95% CI, 1.21 to 2.11; P=0.001). ABO-incompatible transplantation was associated with worse graft survival (hazard ratio, 2.09; 95% CI, 1.33 to 3.27; P=0.001) independent from DSA. There was no difference between DSA against class 1, class 2, or both. Stratification into DSA <3000 medium fluorescence intensity (MFI) and DSA ≥3000 MFI resulted in overlapping survival curves. Therefore, separate analyses were performed for 3-month and long-term graft survival. Although DSA <3000 MFI tended to be associated with both lower 3-month and long-term transplant survival in deceased donation, DSA ≥3000 MFI were only associated with worse long-term transplant survival in deceased donation. In living donation, only strong DSA were associated with reduced graft survival in the first 3 months, but both weak and strong DSA were associated with reduced long-term graft survival. A higher incidence of antibody-mediated rejection within 6 months was only associated with DSA ≥3000 MFI.

Conclusions

Preformed DSA were associated with an increased risk for graft loss in kidney transplantation, which was greater in living than in deceased donation. Even weak DSA <3000 MFI were associated with worse graft survival. This association was stronger in living than deceased donation.

Introduction

Avoiding kidney transplantation in case of a positive complement-dependent cytotoxicity crossmatch due to donor-specific HLA antibodies (DSA) was a pivotal step in establishing transplantation as a modality of kidney replacement therapy in patients with advanced kidney diseases (1). Still, a negative crossmatch is mandatory for kidney transplantation in the Eurotransplant region.

The prognostic value of low-level DSA, which are only detectable by more sensitive methods, remains controversial (2). A meta-analysis comprising 3061 patients showed an association of preformed DSA with a higher risk for graft failure (3), but the effect size of these findings still generates controversy (4–6). Particularly for living donation, few studies have been adequately powered to evaluate graft survival. Kwon et al. (7) compared 81 DSA-positive and 494 DSA-negative transplants; however, these investigators did not find an association of DSA with worse graft outcome. Also, a Korean study of 1964 living donor transplantations detected no association of DSA with lower graft survival in HLA-incompatible transplants, mainly performed after desensitization (8). Orandi et al. (9) evaluated graft loss and mortality of 1025 living donor transplants performed after desensitization from preformed DSA. A positive flow or complement-dependent cytotoxicity crossmatch was associated with poorer outcome, whereas the outcome of patients with a negative flow crossmatch was the same as in the control group without DSA.

Recently, Kamburova et al. reported on 4724 kidney transplants performed in the Netherlands between 1995 and 2005. Among those, 1487 were performed with a living donor transplant (10). Pretransplant serum samples were tested for DSA against HLA-A, -B, -DR, and -DQ retrospectively, in a stepwise procedure. As the DSA were not known at the time of transplantation, no desensitization procedures were performed. Patients with DSA receiving a kidney transplant from a deceased donor revealed significantly lower death-censored graft survival, whereas no clear effect of DSA could be detected in living donation. Flow crossmatches were not performed in this study, but the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of the DSA as detected by Luminex-based assays revealed no association with graft survival.

Orandi et al. (9) examined only patients in need of desensitization, and the Dutch study aimed to show the association of DSA that were not known at the time of transplantation with graft survival. Therefore, we decided to analyze graft survival of all patients tested by state-of-the-art, Luminex-based, antibody detection assays for the presence of DSA before transplantation, irrespective of the need for desensitization. As patients with increased immunosuppression due to preformed DSA and/or treatment of rejection episodes might have a higher risk of death with a functioning graft, we decided to evaluate graft survival without censoring for death as primary outcome.

Materials and Methods

Study Cohort

A total of 4233 adult patients with kidney transplants performed between 2012 and 2015 in 18 German transplant centers were included in this study. For most centers, all transplants performed in this period were included. For five centers, complete data were only available for 1 or 2 years of this period. Pediatric patients were excluded because of their low number (n=189). Patients and donors were predominantly white. There were no nonheart-beating donors. The clinical and research activities reported are consistent with the Principles of the Declaration of Istanbul as outlined in the Declaration of Istanbul on Organ Trafficking and Transplant Tourism. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Lübeck (reference 15–132).

Clinical and Laboratory Data

Data on preformed DSA, clinical outcome, and possible covariates were collected retrospectively from the hospital and laboratory information systems. Additional data for deceased donors was provided by the German Organ Transplantation Foundation. The Kidney Donor Risk Index (KDRI) was calculated according to Rao et al. (11). Transplants were defined as ABO-incompatible according to patients’ and donors’ blood groups irrespective of the recipients titer of ABO antibodies.

After exclusion of 101 patients because of missing follow-up data or insufficient data on HLA antibodies and/or donor typing to assign DSA against HLA-A, -B, -C, -DRB1, or -DQB1, 4132 patients remained for analyses. Some control parameters were missing for 1064 patients (mainly KDRI score for deceased kidney donations from other Eurotransplant countries and/or immunosuppressive therapy; see Table 1 for details).

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients with living and deceased kidney transplantation stratified according to presence and strength of DSA

| Variable | Living Donation, n=1324 | Deceased Donation, n=2808 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No DSA | DSA <3000 MFI | DSA ≥3000 MFI | Missing Data, n | No DSA | DSA <3000 MFI | DSA ≥3000 MFI | Missing Data, n | |

| Patient age, yr | 46 (33–55) | 49 (34–55) | 46 (37–53) | 0 | 56 (46–65) | 54 (44–65) | 55 (43–65) | 0 |

| Patient sex, women | 439 (36) | 29 (49) | 23 (49) | 0 | 977 (38) | 71 (49) | 62 (54) | 0 |

| Current % PRA | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–28) | 4 | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–24) | 15 (0–73) | 0 |

| Highest % PRA | 0 (0–0) | 2 (0–19) | 33 (1–82) | 4 | 0 (0–6) | 10 (0–79) | 57 (10–95) | 0 |

| DSA strength, maximum MFI | n.a. | 1142 (680–1683) | 6198 (4400–11,485) | 0 | n.a. | 1177 (657–2000) | 7400 (4357–12,057) | 0 |

| DSA strength, cumulative MFI | n.a. | 1200 (680–1807) | 7900 (4579–13,700) | 0 | n.a. | 1279 (774–2049) | 9400 (5783–15,700) | 0 |

| DSA class, n (%) | 0 | 0 | ||||||

| Class 1 only | n. a. | 29 (49) | 16 (34) | n. a. | 85 (58) | 54 (47) | ||

| Class 2 only | n. a. | 25 (42) | 18 (38) | n. a. | 46 (32) | 25 (22) | ||

| Class 1 and 2 | n. a. | 5 (8) | 13 (28) | n. a. | 15 (10) | 35 (30) | ||

| Retransplant, n (%) | 64 (5) | 11 (19) | 10 (21) | 0 | 252 (10) | 43 (29) | 47 (41) | 0 |

| Preemptive transplantation, n (%) | 388 (32) | 19 (32) | 9 (19) | 0 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| Time on dialysis, yr | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–1) | 1 (0–2) | 0 | 5 (3–8) | 5 (3–8) | 6 (3–9) | 62 |

| Donor age, yr | 53 (47–60) | 52 (45–58) | 53 (47–57) | 0 | 55 (44–66) | 57 (48–66) | 51 (34–63) | 0 |

| Donor sex, women | 738 (61) | 38 (64) | 20 (43) | 0 | 1201 (47) | 77 (53) | 54 (47) | 0 |

| Kidney Donor Risk Index (11) | n. a. | n. a. | n. a. | n. a. | 1.3 (1.0–1.9) | 1.4 (1.1–1.9) | 1.3 (1.0–1.8) | 484 |

| Cold ischemic period, min | 151 (120–180) | 150 (120–180) | 133 (117–183) | 32 | 713 (527–900) | 717 (495–920) | 782 (531–977) | 43 |

| No. of mismatches for HLA-A/B/DR | 3 (2–4) | 4 (3–5) | 4 (3–5) | 133 | 3 (2–4) | 3 (2–4) | 3 (3–4) | 1 |

| Induction therapy, n (%) | 164 | 255 | ||||||

| None | 177 (17) | 7 (13) | 3 (6) | 308 (13) | 13 (9) | 5 (4) | ||

| ATG | 62 (6) | 8 (14) | 11 (23) | 410 (18) | 41 (29) | 48 (42) | ||

| IL-2 | 671 (63) | 29 (52) | 16 (34) | 1538 (67) | 77 (54) | 41 (36) | ||

| CD20 | 15 (1) | 0 (0) | 4 (9) | 2 (0) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | ||

| CD52 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 6 (0) | 2 (1) | 5 (4) | ||

| IL-2 and CD20 | 119 (11) | 11 (19) | 7 (15) | 6 (0) | 3 (2) | 2 (2) | ||

| Further combinationa | 13 (1) | 1 (2) | 6 (13) | 27 (1) | 5 (4) | 13 (11) | ||

| Initial immunosuppression, n (%) | 165 | 512 | ||||||

| CsA/MMF/steroids | 141 (13) | 3 (5) | 1 (2) | 508 (22) | 21 (15) | 6 (5) | ||

| Tac/MMF/steroids | 751 (71) | 44 (79) | 40 (85) | 1434 (63) | 104 (73) | 87 (76) | ||

| Other | 164 (16) | 9 (16) | 6 (13) | 354 (15) | 17 (12) | 21 (18) | ||

| Desensitization, n (%) | 2 | 1 | ||||||

| No desensitization | 915 (75) | 36 (61) | 26 (55) | 2456 (96) | 137 (94) | 95 (83) | ||

| ABO-incompatible transplantation | 266 (22) | 13 (22) | 9 (19) | 1 (0)b | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Other desensitization | 35 (3) | 10 (17) | 12 (26) | 89 (3) | 9 (6) | 20 (17) | ||

Data are displayed as number of patients (%) or median (interquartile range). DSA, donor-specific HLA antibodies; MFI, medium fluorescence intensity; PRA, panel-reactive antibodies; n.a., not applicable; ATG, antithymocyte globulin; CD20, CD20 receptor antagonist (rituximab); CD52, CD52 receptor antagonist; CsA, cyclosporin A; MMF, mycophenolate mofetil; Tac, tacrolimus.

Ten living donation patients without DSA (one with DSA <3000 MFI and six with DSA ≥3000 MFI) received a further combined induction therapy including ATG, as well as 27 deceased donation patients without DSA (five with DSA <3000 MFI and 13 with DSA ≥3000 MFI); 12 living donation patients without DSA (one with DSA <3000 MFI and six with DSA ≥3000 MFI) received a further combined induction therapy including CD20, as well as 14 deceased donation patients without DSA (two with DSA <3000 MFI and nine with DSA ≥3000 MFI).

ABO-incompatible transplantation because of clerical error.

Few donors were typed for HLA-DQA1, -DPA1, or -DPB1, and DSA against exclusively DQA1 or DP were found in only 15 patients; therefore, DSA against these loci were not taken into account. Strategies for antibody testing varied between centers, although most centers used a stepwise approach of screening with bead array tests and differentiation of positive samples by single antigen tests of either manufacturer (LABScreen; OneLambda, Carnoga Park, CA or Lifecodes; Immucor Transplant Diagnostics, Stamford, CT).

A total of 76 donors were lost to follow-up during the first 6 months and were excluded from the evaluation of early antibody-mediated rejections. In the analyses of graft and patient survival, patients were censored at the time they were lost to follow-up.

Statistical Analyses

For descriptive statistics, differences between groups were described using the Pearson chi-squared test and Mood median test, where appropriate. The association between the presence of preformed DSA and overall (not death-censored) graft survival was evaluated by Kaplan–Meier curves with log-rank analyses, as well as by multivariable Cox regression analyses with backward selection (selection criterion P<0.05). Patients with missing values were excluded from the multivariable analysis. Cox models were built considering patient age and sex, current and highest panel-reactive antibodies, DSA class, retransplant, preemptive transplantation (for living donation only), time on dialysis, donor age and sex, KDRI score, cold ischemia period, number of mismatches for HLA-A/B/DR, induction therapy, initial immunosuppression, and desensitization. Furthermore, for sensitivity analysis, transplant center was investigated as random effect.

As the German Society for Immunogenetics recommends to not consider low-level antibodies with <3000 MFI in the selection of allografts even in patients at risk for immunologic graft loss (12), DSA were stratified into <3000 MFI and ≥3000 MFI.

Analyses were performed using R version 3.5.0 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria; http://www.R-project.org).

Results

Patients

Baseline characteristics are given in Table 1. In both living and deceased donation, patients with DSA were more likely to be female, to have been transplanted previously, and had higher current and maximum panel-reactive antibodies values (interquartile range, 0%–20% versus 0%–0% and 0%–61% versus 0%–0% for living donation, and 0%–54% versus 0%–0% and 1%–88% versus 0%–6% for deceased donation). Patients with DSA ≥3000 MFI were more likely to have DSA against both HLA class 1 and 2 than patients with DSA <3000 MFI (28% versus 8% in living and 30% versus 10% in deceased donation; descriptive P=0.03 and <0.001, respectively).

Presence of DSA was associated with more intense immunosuppression (e.g., induction with antithymocyte globulin [ATG], desensitization by plasmapheresis or immunoadsorption). When only ABO-compatible transplantations were evaluated, the proportion of DSA-positive patients receiving a desensitization therapy (e.g., plasmapheresis and/or immunoadsorption) remained larger before living than deceased donation (26% versus 11%; descriptive P=0.002). Rituximab was given more often in living than in deceased donation and in DSA-positive patients (31% of living donation with DSA versus 17% without DSA, and 7% of deceased donations with DSA versus 1% without DSA). When only ABO-compatible living transplants were evaluated, 19% of patients with DSA and 4% without DSA received rituximab. However, patients received more ATG as induction therapy in deceased than living donation (42% versus 25% of patients with DSA, 19% versus 7% of patients without DSA; descriptive P<0.005). In living donation, patients with DSA had more mismatches for HLA-A, -B, and -DR.

Complement-dependent cytotoxicity crossmatches with unseparated cells or T cells were negative for all patients with DSA, with the exception of three living donation patients. None of these three patients lost their graft; one died with a functioning graft after about 2 years. Flow crossmatches were not performed for most patients.

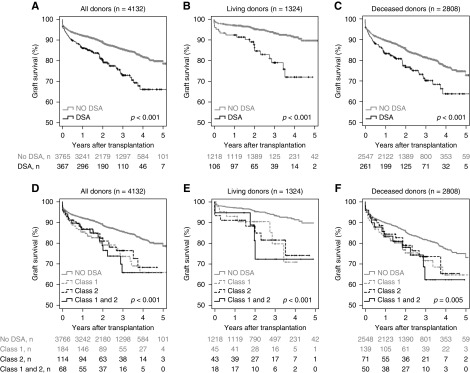

Overall Graft Survival

Lower overall graft survival was associated with pretransplant DSA in both living and deceased donation (Figure 1, A–C). The multivariable analysis revealed an independently higher risk for graft loss, with a hazard ratio of 2.53 (95% confidence interval [95% CI], 1.49 to 4.29; P<0.001) for living and 1.59 (95% CI, 1.21 to 2.11; P=0.001) for deceased donation. Further details are shown in Table 2. There was no visible difference between DSA against class 1 or class 2, or DSA against both classes 1 and 2 (Figure 1, D–F).

Figure 1.

The graft survival of patients with DSA was worse compared with patients without DSA, but not different according to DSA class. Overall graft survival is shown for (A) the total cohort according to the presence of pretransplant DSA, (B) living donors according to the presence of pretransplant DSA, (C) deceased donors according to the presence of pretransplant DSA, (D) the total cohort according to HLA class of pretransplant DSA, (E) living donors according to HLA class of pretransplant DSA, and (F) deceased donors according to HLA class of pretransplant DSA. Numbers of patients at risk are given below the Kaplan–Meier-curves. Log-rank test after exclusion of patients without DSA: (D) P=0.74; (E) P=0.89; (F) P=0.84.

Table 2.

Multivariable Cox regression models for graft survival

| Variable | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|

| Overall graft survival for living donorsa | ||

| Pretransplant donor-specific antibodies | 2.53 (1.49 to 4.29) | <0.001 |

| Pretransplant desensitization | ||

| ABO-incompatible transplantation | 2.09 (1.33 to 3.27) | 0.001 |

| Desensitization in ABO-compatible transplantation | 1.68 (0.78 to 3.58) | 0.18 |

| Time on dialysis, per year | 1.15 (1.05 to 1.27) | 0.004 |

| Number of HLA-A/B/DR-mismatches, per mismatch | 1.19 (1.03 to 1.37) | 0.02 |

| Overall graft survival for deceased donorsb | ||

| Pretransplant donor-specific antibodies | 1.59 (1.21 to 2.11) | 0.001 |

| Patient age, per year | 1.02 (1.01 to 1.03) | <0.001 |

| Kidney Donor Risk Index (11) | 1.85 (1.53 to 2.23) | <0.001 |

95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

n=1189; 135 observations deleted because of missing data.

n=2322; 486 observations deleted because of missing data.

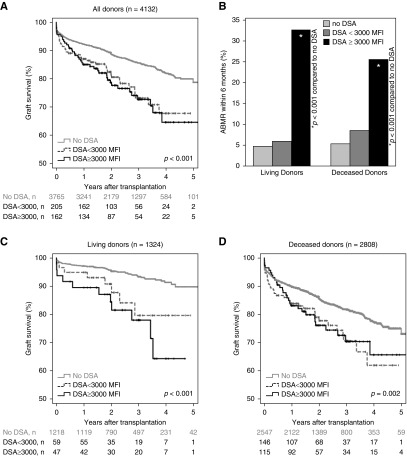

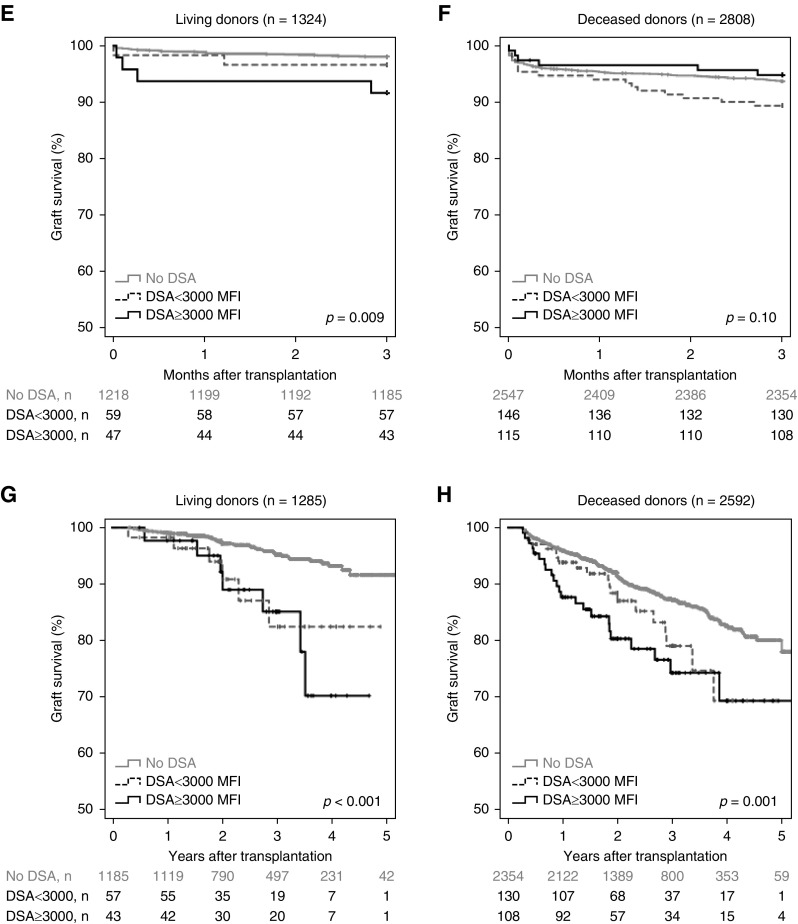

Sensitivity Analyses

Further stratification into patients with DSA <3000 MFI and patients with DSA ≥3000 MFI showed lower graft survival being associated with both DSA groups (Figure 2, A, C, and D). Overlapping survival curves prevented Cox regression analyses in deceased donation (Figure 2D). Therefore, separate analyses were performed for the early time period (to month 3) and long-term graft survival (Figure 2, F and H, Supplemental Table 1, B and C). Although DSA <3000 MFI tended to be associated with both lower 3-month and long-term transplant survival in deceased donation, DSA ≥3000 MFI were only associated with decreased transplant survival after month 3. In living donation, only strong DSA were associated with lower graft survival in the first 3 months, but both weak and strong DSA were associated with lower long-term graft survival (Figure 2, C, E, and G, Supplemental Table 1A).

Figure 2.

Both DSA <3000 MFI and DSA ≥3000 MFI were associated with impaired overall graft survival, while only DSA ≥3000 MFI were associated with early antibody-mediated rejection. Strength of pretransplant DSA are depicted in relation to (A) graft survival for the total cohort, (B) incidence of antibody mediated rejections during the first 6 months after transplantation (*P<0.001 compared with patients without DSA), (C) graft survival for living donors, (D) graft survival for deceased donors, (E) 3-month graft survival for living donors, (F) 3-month graft survival for deceased donors, (G) long-term graft survival starting at the fourth month for living donors, and (H) long-term graft survival starting at the fourth month for deceased donors. Graft survival has not been censored for patient death.

Among living donation patients with DSA, there was no visible difference in graft survival between female patients transplanted with a kidney from their spouse and other patients with DSA before living transplantation (Supplemental Figure 1). Also, the provider used for DSA-testing had no visible effect on the association between DSA and worse graft survival (Supplemental Figure 2). Investigating transplant center as random effect did not reveal any association between transplant center and outcome (Supplemental Table 2).

Preformed DSA were associated with both worse death-censored graft survival and worse patient survival (Supplemental Figure 3). Even desensitization in ABO-compatible transplantation was associated with a higher risk of death-censored graft failure in the multivariable model for living donation. In deceased donation, treatment with cyclosporin A instead of tacrolimus was associated with a slightly lower risk for graft failure (Supplemental Table 3).

Antibody-Mediated Rejection

The incidence of antibody-mediated rejection within 6 months was only associated with pretransplant DSA of at least 3000 MFI, but not with weaker DSA (Figure 2B). Induction treatment with ATG showed no association with a lower incidence of antibody-mediated rejection (Supplemental Figure 4).

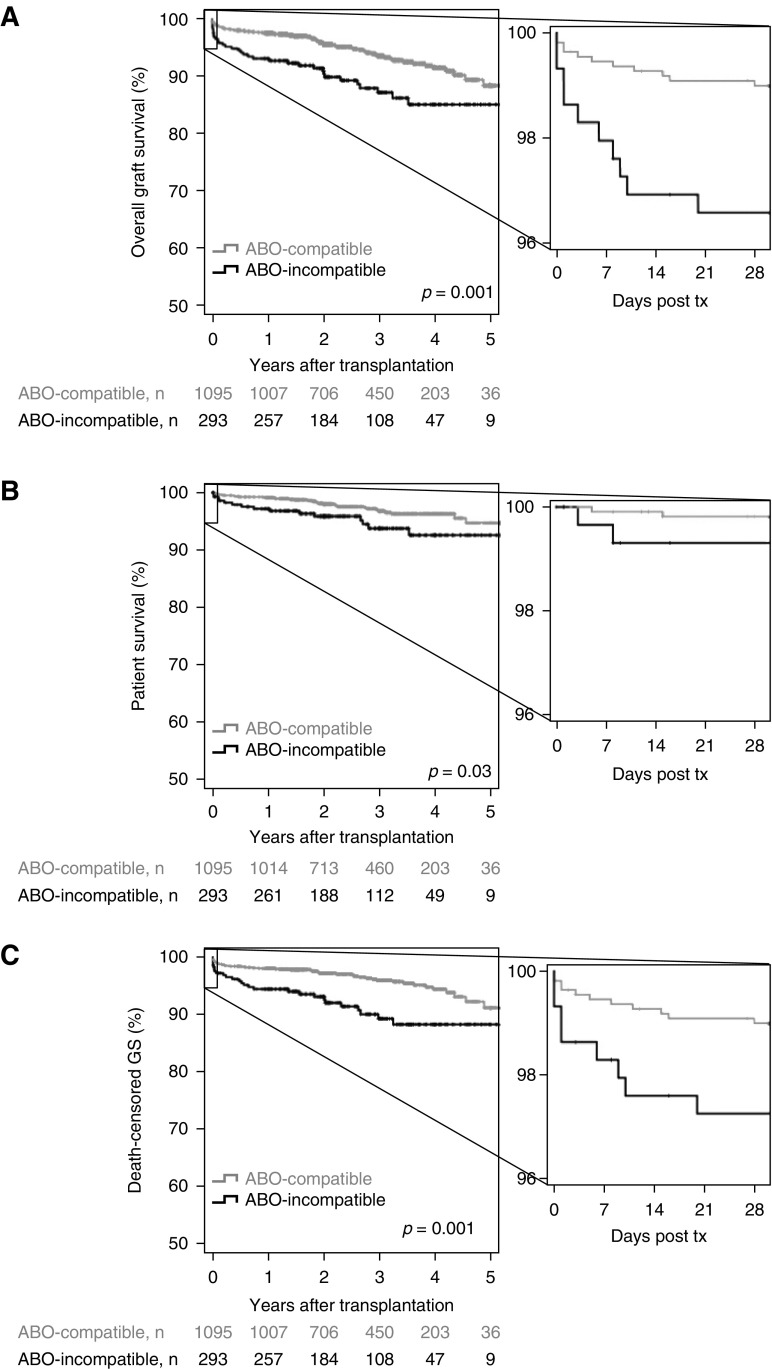

ABO-Incompatible Transplantation

ABO-incompatible living donation was an independent risk factor for overall graft survival in the multivariable analysis (Table 2). This association was most pronounced during the first 10 postoperative days (Figure 3A) and driven by both higher graft failure (lower death-censored graft survival, Figure 3B), as well as lower patient survival (Figure 3C). ABO-incompatible transplantation was still associated with worse graft survival if the analysis was restricted to patients without DSA; however, the association with patient survival lost significance.

Figure 3.

ABO-incompatibility was associated with decreased graft and patient survival after living donation. ABO-incompatible living kidney transplantations are compared with ABO-compatible living donations for (A) overall graft survival, (B) patient survival, and (C) death-censored graft survival. GS, graft survival; tx, transplantation.

Discussion

This study shows that DSA both before living and deceased donation is associated with significantly lower graft survival. This association was independent of patient sex, which excludes pregnancies as a potential underlying immunizing event against the partner and living donor.

It is tempting to attribute the lower hazard ratio of DSA in deceased donation to the higher proportion of patients receiving ATG as induction therapy, as the potential of ATG in preventing rejection episodes and graft loss in patients with DSA is well known (13). However, ATG was not independently associated with graft survival in the multivariable analyses. As deceased donation patients were almost 10 years older and had about 5 years longer dialysis time than living donation patients, they might have had a weakened immune response. Additionally, a more indirect effect could be important: clinicians might have anticipated a higher risk from preformed DSA in deceased donation, e.g., because of the considerably worse organ quality compared with living donation. This risk awareness could have led to more careful monitoring and treatment of DSA-positive patients, which might have attenuated the potentially damaging effect of DSA in deceased donation.

Only a few DSA-positive patients received rituximab. As rituximab can reduce antibody rebound in desensitized patients and anamnestic response in patients with cryptic sensitization to HLA (14,15), it might improve graft survival in DSA-positive patients, even in those with low-MFI DSA. On the other hand, rituximab is associated with leukopenia and increased infectious complications, which might increase mortality (16,17). Therefore, randomized trials are needed to evaluate the efficacy of rituximab in DSA-positive patients (18).

The association of a higher risk of death-censored graft failure with desensitization treatment before ABO-compatible living transplantation has to be interpreted with caution because it only just reached the predefined level of significance and was not present for overall graft survival. Nevertheless, the association could be due to reverse causation: desensitization was performed more often in patients deemed to be at high risk for rejection because of unavailable information in this study (e.g., early loss of previous transplants due to rejection). As these patients also have lower graft survival, an association between desensitization treatment and worse graft survival is observed.

The same phenomenon of reverse causation might have caused the association between initial immunosuppression with cyclosporin A instead of tacrolimus, and lower risk of death-censored graft failure after deceased donation, because cyclosporin A was thought to be less suitable for patients at high risk for allograft rejection (19). A recent meta-analysis of randomized trials, however, showed only marginal differences between calcineurin inhibitor-based regimens and mTOR-inhibitors (20).

The more intense initial immunosuppression in patients with DSA (e.g., more induction with ATG and/or rituximab) could have led to increased complications and eventually higher mortality, which would have contributed to the association of DSA with lower overall graft survival. DSA were indeed associated with lower patient survival, but also with lower death-censored graft survival. The latter is likely to be caused by DSA, even if total exclusion of biases is impossible in a retrospective study.

The association of preformed DSA with a higher risk of overall graft failure in deceased donation corresponds well with the result of a meta-analysis by Mohan et al (3). The effect-size, however, varied markedly among the included studies.

A recent study from the Netherlands showed similar results for preformed DSA in deceased donation (hazard ratio for graft loss, 1.84; 95% CI, 1.55 to 2.19) (10). In living donation, however, DSA were associated with worse graft survival only in the subgroup of donors with DSA against both classes 1 and 2. This discrepancy with our results is even more astonishing because the initial immunosuppression in the Dutch study was weaker (e.g., induction therapy with ATG in only 6.9% of DSA-positive patients) and the DSA were diagnosed retrospectively. Therefore, an improved management of DSA-positive patients in living donation as the reason for a lacking association between DSA and graft survival can be ruled out.

As in our patients, the presence of DSA against both classes 1 and 2 was associated with higher cumulative and maximum MFI in the Dutch study. Contrary to the results of our study, Kamburova et al. (10) did not find an effect of DSA strength, but conclude that recipients with the combination of class 1 and 2 DSAs should be considered as patients with a higher risk of graft failure. As this conclusion is mainly on the basis of multivariable Cox regression models with largely overlapping confidence intervals for the effect of different DSA classes, it might be premature. Also, the potential influence of DSA strength, which is suggested by our results, has to be confirmed by further studies.

The multivariable analysis showed an about two-fold higher risk of graft loss for ABO-incompatible compared with ABO-compatible living donation transplants, which was most pronounced during the first 10 postoperative days. This corresponds well with data from the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients on the outcomes of 738 ABO-incompatible kidney transplantations performed between 1995 and 2010 in the United States (5.9% graft loss during the first year in ABO-incompatible living donation compared with 2.9% in controls) (21). However, the Collaborative Transplant Study (CTS) and a large German center specializing in ABO-incompatible transplants reported equal death-censored graft survival and no or only slightly decreased patient survival of ABO-incompatible transplants (22,23). Only 5% of living donations were ABO-incompatible in the CTS data, compared with >20% in our study. This might hint to the selection of low-risk patients for ABO-incompatible transplantation in the transplant centers providing their data to CTS. On the other hand, even if the increased risk of ABO-incompatible transplants was independent from all other parameters evaluated in our study, a further confounding factor associated with ABO-incompatible transplantation cannot be excluded.

A limitation of this study is the diagnosis of antibody-mediated rejection. Most centers did not perform protocol biopsies, so subclinical rejections might have been missed. We aimed to obtain data that was as accurate as possible by summarizing not only biopsy-proven, antibody-mediated rejection, but also presumed antibody-mediated rejection in the absence of biopsies. Even if the data has to be interpreted with caution, the clearly higher risk of antibody-mediated rejection associated with strong preformed DSA corresponds with the existing literature (8). A further potential limitation of this study is that both details of the procedures used for antibody testing and consequences according to the test results varied widely. Also, the strategies for long-term immunosuppression were heterogeneous, and no detailed data about modifications of the initial immunosuppressive therapy during the observation period were available. However, this heterogeneity is also an important strength of the study because the results show an association between preformed DSA and outcome in routine kidney transplantations in Germany.

Only complement-dependent cytotoxicity crossmatches were performed in this study. Transplant programs requiring negative flow crossmatches would have avoided transplantation in some patients with strong DSA. Therefore, the effect of preformed DSA might be weaker for these centers.

The major lesson from this study is that preformed DSA irrespective of DSA class and donor type are an important risk factor for overall graft survival. Even weak DSA should be taken into account in both living and deceased donation. Whether decreased graft survival can be prevented by optimized immunosuppression and monitoring should be analyzed in further studies. The optimal strategy for deceased donation would be complete avoidance of DSA by consideration of all HLA antibodies in organ allocation. However, particularly for patients with broad sensitization, this could lead to prolonged waiting time (24). Therefore, the increased immunologic risk of DSA has to be weighed against the risk of increased waiting time for each individual patient.

Disclosures

Dr. Bakchoul reports grants from Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, Aspen gGmbH, Stago gGmbH, Expert Akamemi gGmbH, and CLS Behring gGmbH outside this study. Dr. Hugo reports personal fees from Novartis, Berlin-Chemie, Astellas, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Otsuka, Alexion, Fresenius, Ablynx, and Chiesi outside this study. Dr. Kaufmann reports grants and personal fees from Novartis Pharma outside this study. Dr. Lachmann reports personal fees from BmT GmbH (distributor for OneLambda, Carnoga Park, CA). Dr. Renders received payments from Novartis, BMS, and Astellas. Dr. Ziemann received study support in terms of free reagents for other studies from the companies OneLambda and Lifecodes, Immucor Transplant Diagnostics (Stamford, CT). Drs. Altermann, Angert, Arns, Bachmann, Banas, von Borstel, Budde, Ditt, Einecke, Eisenberger, Feldkamp, Görg, Guthoff, Habicht, Hallensleben, Heinemann, Hessler, Kauke, Koch, König, Kurschat, Lehmann, Marget, Muehlfeld, Nitschke, da Silva, Quick, Rahmel, Rath, Reinke, Sommer, Spriewald, Staeck, Stippel, Suesal, Thiele, and Zecher have nothing to disclose.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

See related editorial, “Clinical and Public Policy Implications of Pre-Formed DSA and Transplant Outcomes,” on pages 972–974.

Supplemental Material

This article contains the following supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.13401118/-/DCSupplemental.

Supplemental Table 1. Multivariable Cox regression models for graft survival differentiating for DSA strength.

Supplemental Table 2. Multivariable Cox regression models with center as random effect.

Supplemental Table 3. Multivariable Cox regression models for death-censored graft survival.

Supplemental Figure 1. Overall graft survival of females transplanted from their spouse.

Supplemental Figure 2. Overall graft survival according to test method.

Supplemental Figure 3. Patient survival and death-censored graft survival.

Supplemental Figure 4. Induction treatment with ATG and antibody-mediated rejections.

References

- 1.Patel R, Terasaki PI: Significance of the positive crossmatch test in kidney transplantation. N Engl J Med 280: 735–739, 1969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tait BD, Süsal C, Gebel HM, Nickerson PW, Zachary AA, Claas FHJ, Reed EF, Bray RA, Campbell P, Chapman JR, Coates PT, Colvin RB, Cozzi E, Doxiadis II, Fuggle SV, Gill J, Glotz D, Lachmann N, Mohanakumar T, Suciu-Foca N, Sumitran-Holgersson S, Tanabe K, Taylor CJ, Tyan DB, Webster A, Zeevi A, Opelz G: Consensus guidelines on the testing and clinical management issues associated with HLA and non-HLA antibodies in transplantation. Transplantation 95: 19–47, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mohan S, Palanisamy A, Tsapepas D, Tanriover B, Crew RJ, Dube G, Ratner LE, Cohen DJ, Radhakrishnan J: Donor-specific antibodies adversely affect kidney allograft outcomes. J Am Soc Nephrol 23: 2061–2071, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Loupy A, Lefaucheur C, Vernerey D, Prugger C, Duong van Huyen J-P, Mooney N, Suberbielle C, Frémeaux-Bacchi V, Méjean A, Desgrandchamps F, Anglicheau D, Nochy D, Charron D, Empana JP, Delahousse M, Legendre C, Glotz D, Hill GS, Zeevi A, Jouven X: Complement-binding anti-HLA antibodies and kidney-allograft survival. N Engl J Med 369: 1215–1226, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schinstock CA, Gandhi M, Cheungpasitporn W, Mitema D, Prieto M, Dean P, Cornell L, Cosio F, Stegall M: Kidney transplant with low levels of DSA or low positive B-flow crossmatch: An underappreciated option for highly sensitized transplant candidates. Transplantation 101: 2429–2439, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Viglietti D, Loupy A, Vernerey D, Bentlejewski C, Gosset C, Aubert O, Duong van Huyen JP, Jouven X, Legendre C, Glotz D, Zeevi A, Lefaucheur C: Value of donor-specific anti-HLA antibody monitoring and characterization for risk stratification of kidney allograft loss. J Am Soc Nephrol 28: 702–715, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kwon H, Kim YH, Choi JY, Shin S, Jung JH, Park SK, Han DJ: Impact of pretransplant donor-specific antibodies on kidney allograft recipients with negative flow cytometry cross-matches. Clin Transplant 32: e13266, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ko EJ, Yu JH, Yang CW, Chung BH; Korean Organ Transplantation Registry Study Group : Clinical outcomes of ABO- and HLA-incompatible kidney transplantation: A nationwide cohort study. Transpl Int 30: 1215–1225, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Orandi BJ, Garonzik-Wang JM, Massie AB, Zachary AA, Montgomery JR, Van Arendonk KJ, Stegall MD, Jordan SC, Oberholzer J, Dunn TB, Ratner LE, Kapur S, Pelletier RP, Roberts JP, Melcher ML, Singh P, Sudan DL, Posner MP, El-Amm JM, Shapiro R, Cooper M, Lipkowitz GS, Rees MA, Marsh CL, Sankari BR, Gerber DA, Nelson PW, Wellen J, Bozorgzadeh A, Gaber AO, Montgomery RA, Segev DL: Quantifying the risk of incompatible kidney transplantation: A multicenter study. Am J Transplant 14: 1573–1580, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kamburova EG, Wisse BW, Joosten I, Allebes WA, van der Meer A, Hilbrands LB, Baas MC, Spierings E, Hack CE, van Reekum FE, van Zuilen AD, Verhaar MC, Bots ML, Drop ACAD, Plaisier L, Seelen MAJ, Sanders JSF, Hepkema BG, Lambeck AJA, Bungener LB, Roozendaal C, Tilanus MGJ, Voorter CE, Wieten L, van Duijnhoven EM, Gelens M, Christiaans MHL, van Ittersum FJ, Nurmohamed SA, Lardy NM, Swelsen W, van der Pant KA, van der Weerd NC, Ten Berge IJM, Bemelman FJ, Hoitsma A, van der Boog PJM, de Fijter JW, Betjes MGH, Heidt S, Roelen DL, Claas FH, Otten HG: Differential effects of donor-specific HLA antibodies in living versus deceased donor transplant. Am J Transplant 18: 2274–2284, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rao PS, Schaubel DE, Guidinger MK, Andreoni KA, Wolfe RA, Merion RM, Port FK, Sung RS: A comprehensive risk quantification score for deceased donor kidneys: The Kidney Donor Risk Index. Transplantation 88: 231–236, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Süsal C, Seidl C, Schönemann C, Heinemann FM, Kauke T, Gombos P, Kelsch R, Arns W, Bauerfeind U, Hallensleben M, Hauser IA, Einecke G, Blasczyk R: Determination of unacceptable HLA antigen mismatches in kidney transplant recipients: Recommendations of the German Society for Immunogenetics. Tissue Antigens 86: 317–323, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bächler K, Amico P, Hönger G, Bielmann D, Hopfer H, Mihatsch MJ, Steiger J, Schaub S: Efficacy of induction therapy with ATG and intravenous immunoglobulins in patients with low-level donor-specific HLA-antibodies. Am J Transplant 10: 1254–1262, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zachary AA, Lucas DP, Montgomery RA, Leffell MS: Rituximab prevents an anamnestic response in patients with cryptic sensitization to HLA. Transplantation 95: 701–704, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jordan SC, Lorant T, Choi J: IgG endopeptidase in highly sensitized patients undergoing transplantation. N Engl J Med 377: 1693, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van den Hoogen MWF, Kamburova EG, Baas MC, Steenbergen EJ, Florquin S, M Koenen HJ, Joosten I, Hilbrands LB: Rituximab as induction therapy after renal transplantation: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of efficacy and safety. Am J Transplant 15: 407–416, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Okada M, Watarai Y, Iwasaki K, Murotani K, Futamura K, Yamamoto T, Hiramitsu T, Tsujita M, Goto N, Narumi S, Takeda A, Morozumi K, Uchida K, Kobayashi T: Favorable results in ABO-incompatible renal transplantation without B cell-targeted therapy: Advantages and disadvantages of rituximab pretreatment. Clin Transplant 31: e13071, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sood P, Hariharan S: Anti-CD20 blocker rituximab in kidney transplantation. Transplantation 102: 44–58, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Webster AC, Woodroffe RC, Taylor RS, Chapman JR, Craig JC: Tacrolimus versus ciclosporin as primary immunosuppression for kidney transplant recipients: meta-analysis and meta-regression of randomised trial data. BMJ 331: 810, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wolf S, Hoffmann VS, Habicht A, Kauke T, Bucher J, Schoenberg M, Werner J, Guba M, Andrassy J: Effects of mTOR-is on malignancy and survival following renal transplantation: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials with a minimum follow-up of 24 months. PLoS One 13: e0194975, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Montgomery JR, Berger JC, Warren DS, James NT, Montgomery RA, Segev DL: Outcomes of ABO-incompatible kidney transplantation in the United States. Transplantation 93: 603–609, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Opelz G, Morath C, Süsal C, Tran TH, Zeier M, Döhler B: Three-year outcomes following 1420 ABO-incompatible living-donor kidney transplants performed after ABO antibody reduction: Results from 101 centers. Transplantation 99: 400–404, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zschiedrich S, Jänigen B, Dimova D, Neumann A, Seidl M, Hils S, Geyer M, Emmerich F, Kirste G, Drognitz O, Hopt UT, Walz G, Huber TB, Pisarski P, Kramer-Zucker A: One hundred ABO-incompatible kidney transplantations between 2004 and 2014: A single-centre experience. Nephrol Dial Transplant 31: 663–671, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ziemann M, Heßler N, König IR, Lachmann N, Dick A, Ditt V, Budde K, Reinke P, Eisenberger U, Suwelack B, Klein T, Westhoff TH, Arns W, Ivens K, Habicht A, Renders L, Stippel D, Bös D, Sommer F, Görg S, Nitschke M, Feldkamp T, Heinemann FM, Kelsch R: Unacceptable human leucocyte antigens for organ offers in the era of organ shortage: Influence on waiting time before kidney transplantation. Nephrol Dial Transplant 32: 880–889, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.