Abstract

Objective:

The Val allele of the Val158Met single-nucleotide polymorphism of the catechol-o-methyltransferase gene (COMT) results in faster metabolism and reduced bioavailability of dopamine (DA). Among persons living with HIV (PLWH), Val carriers display neurocognitive deficits relative to Met carriers, presumably due to exacerbation of HIV-related depletion of DA. COMT may also impact neurocognition by modulating cardiometabolic function, which is often dysregulated among PLWH. We examined the interaction of COMT, cardiometabolic risk, and nadir CD4 on neurocognitive impairment (NCI) among HIV+ men.

Methods:

329 HIV+ men underwent COMT genotyping and neurocognitive and neuromedical assessments. Cohort-standardized z-scores for body mass index, systolic blood pressure, glucose, triglycerides, and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol were averaged to derive a cardiometabolic risk score (CMRS). NCI was defined as demographically-adjusted global deficit score≥0.5. Logistic regression modelled NCI as a function of COMT, CMRS, and their interaction, covarying for estimated premorbid function, race/ethnicity, and HIV-specific characteristics. Follow-up analysis included the 3-way interaction of COMT, CMRS, and nadir CD4.

Results:

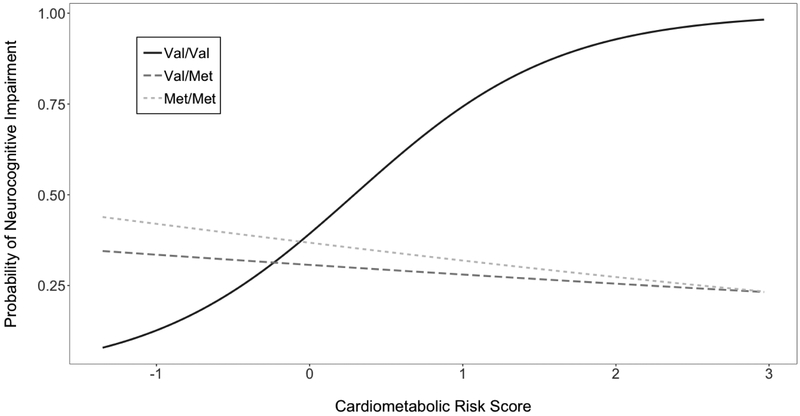

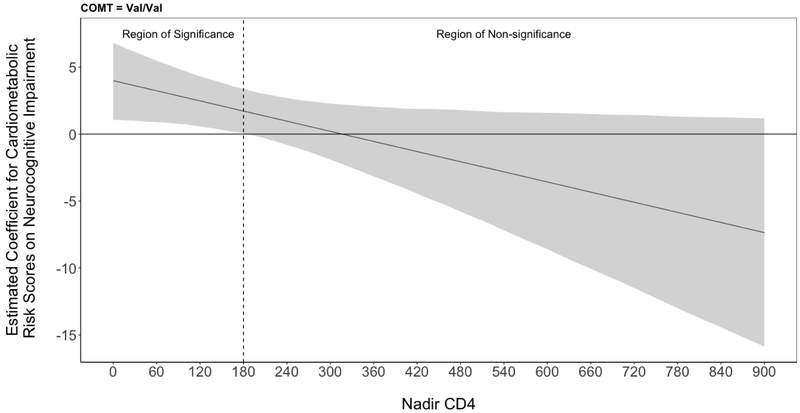

Genotypes were 81 (24.6%) Met/Met, 147 (44.7%) Val/Met, and 101 (30.7%) Val/Val. COMT interacted with CMRS (p=0.02) such that higher CMRS increased risk of NCI among Val/Val (OR=2.13, p<.01), but not Val/Met (OR=0.93, p>.05) or Met/Met (OR=0.92, p>.05) carriers. Among Val/Val, nadir CD4 moderated the effect of CMRS (p<.01) such that higher CMRS increased likelihood of NCI only when nadir CD4<180.

Discussion:

Results suggest a tripartite model by which genetically-driven low DA reserve, cardiometabolic dysfunction, and historical immunosuppression synergistically enhance risk of NCI among HIV+ men, possibly due to neuroinflammation and oxidative stress.

Keywords: NeuroAIDS, Catechol O-Methyltransferase, HIV associated neurocognitive disorders, metabolic syndrome, dopamine, immunosuppression

Introduction

Combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) prolongs life expectancies for persons living with HIV (PLWH); however, neurocognitive impairment (NCI) remains highly prevalent1,2. It is important to identify discrete neuropathological mechanisms that predict NCI in PLWH given that NCI can translate to negative and costly everyday functioning outcomes, including unemployment and poor cART adherence3,4. However, identifying these mechanisms has proven challenging5–7 because PLWH are a heterogeneous group whose neurocognition may be directly impacted by HIV, but also by comorbidities and genetic predispositions that enhance vulnerability to neural injury6,8,9.

PLWH are at greater risk of cardiometabolic complications (i.e., hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, and obesity) possibly due to HIV-related accelerated biological aging and iatrogenic consequences of cART10,11. Cardiometabolic risk contributes to NCI by triggering an array of neuro-compromising processes, including increased blood-brain-barrier permeability, chronic inflammation, and endothelial dysfunction12–16. Furthermore, cardiometabolic risk factors predict imaging biomarkers of white matter and neurochemical abnormalities among PLWH17,18. While cardiometabolic risk factors increase risk of NCI in successfully treated PLWH, they are neither necessary nor sufficient to predict NCI. Thus, susceptibility to the contribution of cardiometabolic risks may be moderated by individual differences in resilience against HIV-related CNS dysfunction.

One factor that could partially explain NCI among PLWH is dopamine (DA) bioavailability. HIV results in exposure to neurotoxic proteins Tat and gp120 that damage frontostriatal regions rich in DA19,20. Post-mortem studies demonstrate decreased frontostriatal concentrations of DA and downregulated gene expression of DA receptors in HIV-infected versus HIV-uninfected persons, and that dysregulation of DA pathways relates to greater HIV disease severity (e.g., HIV RNA level, nadir CD4) and neurocognitive deficits among PLWH21–25.

The erosion of DA homeostasis in PLWH has prompted research on catechol-o-methyltransferase (COMT)6, a functionally diverse enzyme responsible for metabolism of DA, particularly in the prefrontal cortex (PFC). Neurons exposed to macrophage-propagated HIV show increased mRNA expression of COMT and decreased expression of neuronal and synaptic proteins, suggesting that higher levels of COMT in HIV may contribute to DA and neurocognitive dysfunction. In further support of this theory, treatment of HIV-exposed neurons with a COMT inhibitor, Tolcapone, effectively reduced COMT expression and restored neuronal and synaptic integrity26. The Val158Met (rs4680) single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) of the COMT gene encodes differential levels of COMT enzymatic activity, with the Met allele resulting in 40% less activity, and therefore greater DA bioavailability, than the Val allele27. The Met allele has been linked to enhanced neural activation and neurocognitive functioning in PLWH28,29, possibly due to resilience against HIV-related depletion of DA.

Some literature suggests that COMT also operates within cardiometabolic pathways. COMT catalyzes the methylation of catechol estrogens into 2-methoxyestradiol30, which reduces risk of diabetes, hypertension, and obesity31–34. However, COMT activity produces a precursor to homocysteine, which may increase risk of cardiovascular disease, and Val carriers have significantly higher blood levels of total homocysteine than Met homozygotes35–37. Furthermore, lower central DA tone has been linked to obesity and markers of metabolic syndrome, and DA receptor neurotransmission is reduced in obese humans and animals38–40. While greater COMT activity associated with the Val allele may protect against cardiometabolic disorders through increased production of 2-methoxyestradiol, reduced COMT activity associated with the Met allele may also confer protection against cardiometabolic disorders by enhancing DA tone and limiting the accumulation of homocysteine. Although the influence of COMT on cardiometabolic health is complex, these mechanisms suggest that COMT may serve a multifactorial role in the neuropathogenesis of HIV-related NCI through the modulation of cardiometabolic risk and DA bioavailability.

Our first aim is to examine the independent and interactive effects of COMT and cardiometabolic risk on NCI. Given the putative neuroprotective effect of the Met allele in PLWH, we hypothesize that Val/Val carriers with high cardiometabolic risk will have higher rates of NCI compared to others because they are most vulnerable to the deleterious impact of cardiometabolic risk factors on the brain. Because NCI has been more reliably linked to nadir versus current CD4 count in the cART era1,41–43, we will also examine the role of nadir CD4 in the conditional relationships between COMT, cardiometabolic risk, and NCI. We hypothesize that lower nadir CD4 counts will increase likelihood of NCI regardless of COMT and cardiometabolic risk, but will make a larger contribution to NCI in Val/Val carriers with high cardiometabolic risk.

Methods

Participants and Procedure

Participants were 329 HIV+ men who underwent COMT genotyping through NIH-funded research studies coordinated by the HIV Neurobehavioral Research Program (HNRP) at the University of California, San Diego. Of the 329 participants, 76 were enrolled in the Translational Methamphetamine AIDS Research Center (TMARC), a NIDA-funded HNRP cohort study focusing on the central nervous system effects of HIV and methamphetamine. The other 253 participants were enrolled in the CNS HIV Anti-Retroviral Therapy Effects Research (CHARTER) study. All studies were approved by local Human Subjects Protection Committees and all participants provided written informed consent. Exclusion criteria were: 1) diagnosis of psychotic or mood disorder with psychotic features, neurological or medical condition that may impair neurocognitive functioning, such as traumatic brain injury, stroke, epilepsy, hepatitis C, or advanced liver disease; 2) lifetime diagnosis of methamphetamine or cocaine use disorder; 3) low verbal IQ as estimated by a Wide Range Achievement Test44 (WRAT) reading subtest score <70; 4) evidence of intoxication by positive urine toxicology for illicit drugs (except marijuana) or Breathalyzer test for alcohol on the day of testing; and 5) being female. We restricted our sample to men because sexually dimorphic effects of COMT on brain function have been reported45,46 and there were insufficient numbers of women participants in the parent studies to support separate analyses. Lifetime cocaine or methamphetamine use disorder, even remote, was exclusionary in order to eliminate potential confounding effects of stimulant-induced alteration of dopaminergic signaling.

Neuromedical Assessment

All participants underwent a comprehensive neuromedical assessment and non-fasting blood draw. Detailed history of medical and antiretroviral (ARV) use was collected and ARV treatment status was coded as currently on, past use, or never used. HIV infection was diagnosed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay with Western blot confirmation. Routine clinical chemistry panels, complete blood counts, rapid plasma reagin, hepatitis C virus antibody, and CD4+ T cell count (flow cytometry) were performed at each site’s certified clinical laboratory. HIV viral load in plasma and CSF were measured using reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (Amplicor, Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN), with a lower limit of quantitation (LLQ) of 50 copies/ml). HIV viral load was dichotomized as detectable vs. undetectable at the LLQ of 50 copies/ml.

Cardiometabolic Risk Assessment

Non-fasting levels of serum glucose, plasma triglycerides, and plasma total, high-density lipoprotein (HDL) and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol levels were assayed by standard protocols at each site’s clinical laboratory. Blood pressure (BP) was measured in the seated position with an automated sphygmomanometer and body mass index (BMI) was calculated from measured weight and height. Our primary predictor of interest was a continuously scaled, composite cardiometabolic risk score (CMRS)47 based on the five components of metabolic syndrome outlined by the Adult Treatment Panel48 including obesity, elevated BP, elevate blood glucose, elevated triglycerides, and reduced (HDL) cholesterol. Cohort-standardized z-scores for BMI, systolic BP, glucose, triglycerides, and HDL cholesterol (inverse polarity) were averaged to generate our CMRS. A CMRS was derived from 4 of the 5 component z-scores for participants who were either missing HDL (n=50) or triglycerides (n=4) values.

COMT Genotyping

For participants enrolled in TMARC, DNA for genotyping was isolated from stored whole blood or peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) using the Qiagen QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). COMT Val158Met (rs4680) SNP was assayed using an array that included SNPs associated with catecholaminergic genes49. For participants enrolled in CHARTER, DNA for genotyping was extracted from PBMCs using PUREGENE (Gentra Systems, Inc, Minneapolis, MN). All samples were genotyped using the Affymetrix Genome-Wide Human SNP Array 6.0TM50.

Neurocognitive Assessment

All participants completed a comprehensive and standardized neurocognitive assessment across seven neurocognitive domains commonly impacted by HIV1,51. Test scores were adjusted for known demographic influences (i.e., age, education, and race/ethnicity) on neurocognitive performance52–54. Deficit scores that give differential weight to impaired over normal performance were calculated for each domain and averaged to derive a global deficit score (GDS) ranging from 0 (normal) to 5 (severe). Consistent with prior studies, neurocognitive status was classified as impaired (NCI) vs. unimpaired using a validated cut-point of GDS ≥ 0.551,55 The GDS is easier to compute, more clearly operationalized (e.g., Frascati criteria do not specify how to apply a 1 SD cutoff to define “impairment” of ability domains with variable numbers of measures) and a more conservative approach to classifying NCI as compared to the clinical ratings algorithm used in Frascati criteria for HIV-associated Neurocognitive Disorders; however, an individual classified as impaired via GDS ≥ 0.5 is essentially guaranteed to meet the NCI aspect of Frascati criteria55.

Psychiatric Assessment

Current mood symptoms were assessed using the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) version one or two56. The computer-based Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI)57 was administered to determine DSM-IV diagnoses of current and lifetime substance use disorders (SUD) and Major Depressive Disorder (MDD).

Statistical Analysis

COMT group differences in demographics, HIV disease, neuropsychiatric, cardiometabolic, and neurocognitive variables were examined using ANOVAs, Kruskal-Wallis tests, and Chi-square statistics as appropriate. To follow-up on significant omnibus results, pair-wise comparisons were conducted using Tukey’s Honest Significant Difference (HSD) tests for continuous outcomes or Bonferroni-corrections for categorical outcomes58. Cohen’s d statistics are presented for estimates of effect size for statistically significant pair-wise differences. Logistic regression examined the univariate relationship between CMRS and NCI.

Next, we used multivariate logistic regression to model our NCI classification as a function of COMT, CMRS, and their interaction. COMT genotype was reference coded59 with the high enzymatic activity Val/Val group as the reference. WRAT, race/ethnicity, nadir CD4, current CD4, plasma viral load detectability, and ARV status were entered as covariates because they either significantly differed across COMT genotype or are known to influence neurocognition in the cART era1,60. A 3-way interaction term between nadir CD4*COMT*CMRS, as well as accompanying lower-order terms, was added in a follow-up model in order to explore the potential moderating effect of HIV-induced immunosuppression on the contributions of COMT and CMRS on NCI. Group differences and logistic regression analyses were performed using JMP Pro version 12.0.1 (JMP®, Version <12.0.1>, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, 1989–2007).

Exploratory analyses, stratified by COMT genotype, employed the Johnson-Neyman (J-N) technique61,62 to compute any specific boundaries of nadir CD4 at which CMRS significantly predicted NCI. These boundaries are referred to as regions of significance. Compared to simple slope analyses that describe the effect of a predictor (i.e., CMRS) at fixed levels of a continuous moderator (i.e., nadir CD4), the J-N technique identifies the full range of moderator values for which the predictor slope is statistically significant. Region of significance analyses adjusted for false discovery rate63 and were computed using the jtools package in R statistical software (version 3.4.4, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Participants

Table 1 presents COMT group differences on demographic and clinical characteristics. COMT distribution across the 329 participants (age: M=44.0, SD=8.97, education: M=14.1, SD=2.34) was 81 (24.6%) Met/Met, 147 (44.7%) Val/Met, and 101 (30.7%) Val/Val. Genotype distribution was consistent with Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium in the full sample χ2 (χ2=3.49, p=0.06) and within each race/ethnicity group (ps>.11). However, genotype frequency differed significantly by race/ethnicity (χ2= 11.24, p=0.02) with non-Hispanic White participants more likely to carry a Met allele than non-Hispanic Black participants (χ2=8.75, p=0.003). COMT groups were comparable across most demographic, psychiatric, and HIV disease characteristics, with the exception of estimated premorbid verbal IQ for which Met/Met displayed significantly higher WRAT scores than Val/Val (d=0.40, p=0.007). Most participants experienced cART-induced immune reconstitution, as evidenced by active ARV use (76%) and markedly higher current CD4 counts (median=458 cells/mm3) compared to nadir CD4 counts (median=180 cells/mm3). Half the sample (51%) had detectable levels of plasma viral RNA at a limit of detection of 50 copies per ml.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics by COMT genotype (N=329)

| Variable | Met/Met (n=81) |

Val/Met (n=147) | Val/Val (n=101) |

p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Age (years) | 45.1 (9.69) | 43.7 (9.09) | 43.6 (8.16) | 0.44 |

| Education (years) | 14.3 (2.54) | 14.1 (2.39) | 13.9 (2.1) | 0.54 |

| Estimated Verbal IQ (WRAT) | 104.4 (11.41) | 101 (11.3) | 99.8 (11.76) | 0.02a |

| Ethnicity | 0.02a | |||

| Non-Hispanic White (n=245) | 66 (81%) | 110 (75%) | 69 (68%) | |

| Non-Hispanic Black (n=33) | 3 (4%) | 12 (8%) | 18 (18%) | |

| Hispanic (n=51) | 12 (15%) | 25 (17%) | 14 (14%) | |

| HIV Disease Characteristics | ||||

| AIDS diagnosis | 53 (65%) | 89 (61%) | 57 (56%) | 0.47 |

| Duration of HIV infection (years) | 10.2 (7.83) | 9.5 (6.44) | 9.2 (6.3) | 0.60 |

| Current CD4 count (cells/mm3) | 517 (255.5) | 470 (261.1) | 457 (261.5) | 0.27 |

| Nadir CD4 count (cells/mm3) | 180 [63.5–305] | 175 [44–297] | 175 [55–297.5] | 0.83 |

| Plasma viral load | ||||

| Copies/ml (log10) | 1.8 [1.7–3.3] | 1.9 [1.7–3.7] | 2.3 [1.7–3.9] | 0.45 |

| Detectable | 42 (52%) | 69 (47%) | 57 (56%) | 0.33 |

| CSF viral load | ||||

| Copies/ml (log10)b | 1.7 [1.7–1.7] | 1.7 [1.7–2.2] | 1.7 [1.7–2.4] | 0.21 |

| Detectableb | 11 (18%) | 34 (29%) | 24 (29%) | 0.24 |

| ARV status | 0.36 | |||

| Currently on | 67 (83%) | 105 (71%) | 77 (76%) | |

| Past use only | 7 (9%) | 16 (11%) | 10 (10%) | |

| ARV naïve | 7 (9%) | 26 (18%) | 14 (14%) | |

| Current regimen type | 0.21 | |||

| PI-based | 31 (46%) | 54 (51%) | 42 (55%) | |

| NNRTI-based | 27 (40%) | 38 (36%) | 30 (39%) | |

| PI/NNRTI-based | 4 (6%) | 11 (10%) | 5 (6%) | |

| Other | 5 (7%) | 2 (2%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Duration of current regimen (months) | 12 [3–33] | 13 [4–27] | 12 [4–33] | 0.96 |

| Neuropsychiatric characteristics | ||||

| Lifetime any substance use disorder | 38 (47%) | 68 (46%) | 51 (51%) | 0.80 |

| Alcohol | 35 (43%) | 57 (38%) | 42 (42%) | 0.79 |

| Cannabis | 16 (20%) | 21 (14%) | 18 (18%) | 0.54 |

| Opioid | 0 (0%) | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 0.99 |

| Major Depressive Disorder | ||||

| Lifetime | 44 (54%) | 72 (49%) | 51 (51%) | 0.74 |

| Current | 15 (19%) | 19 (13%) | 12 (12%) | 0.41 |

| BDI score | 11.8 (9.57) | 12.6 (10.14) | 11.2 (9.32) | 0.52 |

Note. Values presented as mean (SD), median [IQR], or N (%). WRAT= Wide-Range Achievement reading subtest; ARV= antiretroviral therapy; PI= Protease-inhibitor; NNRTI= non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor; BDI= Beck Depression Inventory

Significant difference between Met/Met and Val/Val

CSF viral load values available for a subset of participants: Met/Met (n=60), Val/Met (n=118), Met/Met (n=82)

COMT, Cardiometabolic Risk, and NCI

Table 2 presents COMT group differences on cardiometabolic and neurocognitive variables. Met/Met had significantly higher diastolic blood pressure than Val/Met (d=0.37, p=0.02) but not Val/Val. COMT groups did not differ significantly on any other cardiometabolic risk parameters, including the composite CMRS (F=0.09, p=0.91). Similarly, COMT groups did not differ significantly on GDS (F=0.17, p=0.84) or frequency of NCI (χ2=2.39, p=0.30), with rates ranging from 32% (Val/Met) to 42% (Val/Val). Although greater CMRS increased likelihood of NCI, this relationship was also not significant (OR=1.12, 95%CI [0.89–1.40], p=0.34).

Table 2.

Cardiometabolic risk and neurocognitive performance by COMT genotype

| Variable | Met/Met (n=81) |

Val/Met (n=147) | Val/Val (n=101) |

p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiometabolic parameters | ||||

| Cardiometabolic risk score | 0.01 (0.489) | −0.02 (0.548) | −0.01 (0.467) | 0.91 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2)a | 26.3 (4.42) | 25.8 (4.37) | 25.4 (4.46) | 0.43 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg)a | 127 (14.13) | 124.4 (15.41) | 124.6 (14.76) | 0.41 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg)a | 79.3 (9.68) | 75.8 (8.98) | 76.2 (9.66) | 0.02b |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 196.8 (54.11) | 184.6 (40.68) | 192.2 (41.24) | 0.12 |

| High-density lipoprotein (mg/dL)a | 41.8 (15.94) | 42.2 (15.71) | 44.5 (22.52) | 0.59 |

| Low-density lipoprotein (mg/dL) | 111.8 (37.63) | 100.2 (35.16) | 106.8 (35.22) | 0.10 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL)a | 217.6 (149.22) | 221.3 (140.91) | 228.8 (158.63) | 0.87 |

| Glucose (mg/dL)a | 94 [86–105.5] | 92 [81–107] | 92 [83–107.5] | 0.87 |

| Neurocognitive Performance | ||||

| Global deficit score | 0.51 (0.52) | 0.49 (0.58) | 0.47 (0.48) | 0.84 |

| Neurocognitive impairmentc | 29 (36%) | 47 (32%) | 42 (42%) | 0.30 |

Note. Values presented as mean (SD), median [IQR], or N (%).

Cardiometabolic risk score component

Significant difference between Met/Met and Val/Met

Neurocognitive impairment defined as global deficit score ≥ 0.5

COMT and CMRS Interaction

Table 3 presents estimates for the multivariate logistic regression modelling NCI as a function of COMT, CMRS, and NCI, covarying for WRAT scores, race/ethnicity, and HIV disease characteristics. The overall model was significant (χ2(13,329)=392.68, p=0.001). A significant omnibus interaction between COMT and CMRS was detected (χ2(2,329)=7.93, p=0.02) such that higher CMRS levels significantly increased likelihood of NCI among Val/Val (OR=2.13, p<.01), yet the deleterious effect of CMRS on NCI was significantly attenuated in Met/Met (interaction of CMRS × Met/Met [compared to Val/Val]: ORR=0.42, p<.05) and Val/Met (interaction of CMRS × Val/Met [compared to Val/Val]: ORR=0.43, p<.05). Specifically, CMRS did not significantly predict NCI among Met/Met (OR=0.92, p>.05) or Val/Met (OR=0.93, p>.05) carriers (Figure 1). Lower WRAT, lower nadir CD4, and detectable HIV RNA significantly increased probability of NCI (ps<.05).

Table 3.

Multivariable logistic regression predicting neurocognitive impairment

| Predictor | B (SE) | p | ORa | OR 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Met/Metb | −0.15 (0.34) | 0.664 | 0.87 | [0.45, 1.67] |

| Val/Metb | −0.42 (0.29) | 0.156 | 0.66 | [0.37, 1.17] |

| Cardiometabolic risk scorec | 0.76 (0.28) | 0.007 | 2.13 | [2.13, 3.68] |

| Cardiometabolic risk score × Met/Met | −0.87 (0.39) | 0.025 | 0.42 | [0.19, 0.90] |

| Cardiometabolic risk score × Val/Met | −0.83 (0.33) | 0.012 | 0.43 | [0.23, 0.83] |

| WRATd | −0.37 (0.11) | 0.001 | 0.69 | [0.55, 0.86] |

| Nadir CD4e | −0.13 (0.03) | 0.017 | 0.88 | [0.79, 0.98] |

| Detectable plasma viral load | 0.59 (0.29) | 0.040 | 1.80 | [1.03, 3.16] |

| Current CD4e | 0.03 (0.05) | 0.338 | 1.05 | [0.95, 1.11] |

| ARV status never used | −0.26 (0.47) | 0.574 | 0.77 | [0.31, 1.93] |

| ARV status past usef | 0.15 (0.44) | 0.736 | 1.16 | [0.49, 2.72] |

| Non-Hispanic Blackg | −0.37 (0.44) | 0.398 | 0.69 | [0.29, 1.63] |

| Hispanich | 0.30 (0.34) | 0.374 | 1.36 | [0.69, 2.64] |

Note. Bolded predictors are significant at p<.05. ARV= antiretroviral therapy; OR= odds ratio; WRAT= Wide Range Achievement Test

Interaction terms reflect odds rate ratios

Compared to Val/Val

Per 1 standard deviation change

Per 10-unit change

Per 50-unit change;

Compared to ARV status currently using

Compared to non-Hispanic White

Figure 1.

Greater cardiometabolic risk predicts neurocognitive impairment among Val/Val only

Conditional Role of Nadir CD4

To determine whether HIV disease severity influenced the interactive effects of COMT and CMRS on NCI, we expanded our model with terms capturing the 3-way interaction between nadir CD4, COMT, and CMRS. A significant 3-way interaction was detected between nadir CD4, COMT, and CMRS (χ2(2,329)=8.86, p=0.01). Nadir CD4 did not significantly alter the null associations between CMRS and NCI among Val/Met and Met/Met. In Val/Val, nadir CD4 significantly moderated the deleterious effect of CMRS on NCI (for 50-unit increase: ORR=0.53, 95%CI [0.32, 0.81], p=0.008). In order to inspect changes in the slope of CMRS on NCI due to different nadir CD4 counts, we applied the J-N technique. In Val/Val, CMRS significantly increased likelihood of NCI (i.e., lower bound of CMRS slope>0) at nadir CD4 counts below 180 (Figure 2). Conversely, CMRS did not significantly predict NCI in Val/Val for nadir CD4 counts at or above 180.

Figure 2.

Greater cardiometabolic risk significantly increases likelihood of neurocognitive impairment in Val/Val with nadir CD4 below 180

To focus on a clinically relevant subgroup, we applied the 3-way interaction model in participants who were currently using cART and had undetectable HIV RNA (n=155). Results in this virologically suppressed subgroup did not differ from those in the entire study sample, with COMT, CMRS, and nadir CD4 significantly interacting to predict NCI (χ2(2,150)=10.25, p=0.006).

Discussion

Dopaminergic dysregulation, cardiometabolic dysfunction, and low nadir CD4 counts (i.e., advanced HIV-induced immunosuppression) are putative risk factors for NCI in the context of HIV. In contrast to most neuroAIDS studies that examine independent effects of risk factors on NCI, this study also examined interactions of cardiometabolic risk, COMT, and nadir CD4 in order to address the complex interplay of these risk factors. Although neither COMT nor CMRS correlated univariably with NCI, higher CMRS significantly increased probability of NCI in Val/Val individuals. Furthermore, CMRS effects on neurocognitive function in Val/Val carriers were moderated by nadir CD4: higher CMRS increased probability of NCI only in participants with nadir CD4 counts below 180. These findings remained significant in patients with fully-suppressed HIV on cART, underscoring the relevance of these genetic and environmental risk factors for NCI for even the most successfully treated PLWH.

Our group has previously reported better executive function among Met/Met, compared to Val-carriers, in HIV+ men29. In contrast, the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study found no main effects of COMT or interactive effects with stimulant use and current CD4 on neurocognitive performance in predominantly male (87%−100%) samples64,65. In our study, COMT did not univariably relate to frequency of NCI, which, consistent with prior GDS-based estimates of NCI in PLWH51,55, was 36% across the entire study sample. We may not have detected a univariable relationship between COMT and NCI because individual SNPs often exhibit modest associations with behavioral phenotypes66. Given that COMT pleiotropically influences multiple neurobiological processes, the study of moderating environmental variables can help explain under which conditions the neurocognitive effects of COMT are most salient.

Our results support a gene × environment interaction approach, as the putatively harmful effect of the Val allele only appeared under environmental conditions of high cardiometabolic burden and low nadir CD4 counts. Similar interactive effects of COMT and cardiovascular risk have been previously reported in healthy adults, with Val carriers demonstrating steeper declines in episodic memory compared to Met/Met individuals only at elevated levels of pulse pressure67. While the effects of cardiometabolic comorbidities on poor neurocognition are not unique to PLWH, cardiometabolic abnormalities may be particularly disruptive in PLWH given their high prevalence and potential to combine with other HIV-related brain insults to synergistically deplete cognitive reserve68. Although studies of cardiometabolic risk often dichotomize individual cardiometabolic conditions based on thresholds of clinical laboratory values69, we modelled cardiometabolic risk as a standardized, continuous variable. This approach is statistically advantageous because continuous predictors preserve power and precision70. Moreover, thresholds for dichotomizing cardiometabolic conditions are imprecisely defined and overlook incremental relationships between cardiovascular disease outcomes (e.g., stroke) and health indicators (e.g., BP)71. Importantly, continuous cardiometabolic risk scores inversely relate to physical activity47,72 and therefore, provide further evidence to advocate exercise in its neurocognitive benefits for PLWH.

With respect to conditional effects of HIV-induced immunosupression, Levine et al.65 did not detect interactions between current CD4 count and DA-related genes, including COMT, on neurocognitive performance. However, as the authors note, current CD4 may be a suboptimal indicator of HIV disease severity given that nadir CD4 is a stronger predictor of NCI and brain integrity in the cART era1,41,73. Furthermore, lower nadir CD4, but not current CD4, is correlated with reduced DA transporter availability in the ventral striatum25. Our results indicating that lower nadir CD4 counts independently predict higher odds of NCI are consistent with the prior findings of Ellis et al.41 that describe a monotonic relationship between lower nadir CD4 counts and higher odds of NCI, even in PLWH with viral suppression and minimal-to-moderate comorbidity burden. Importantly, we also demonstrate that nadir CD4 moderates the interactive effects of COMT and CMRS. The clinical impact of these findings is highlighted by the substantial portion (55%) of Val/Val participants with nadir CD4 counts at or below 180, a range at which our region of significance analysis indicates a heightened vulnerability to the deleterious neurocognitive effects of cardiometabolic risk. In a prior investigation that implemented machine learning to generate predictive models for NCI, the predictive utility of viral load and duration of treatment were improved when nadir CD4 was less than 22574, a threshold similar to that of the present study.

Some hypothesize that the relationship between cortical function and DA bioavailability follows an inverted U-shaped curve, with optimal neurocognition occurring at intermediate levels of DA signaling75,76. Within this framework, severe immunosuppression in PLWH may lead to persistently suboptimal levels of bioavailable DA even after successful immune reconstitution with cART. The slow rate of DA clearance conferred by the Met allele may protect against this shift, whereas the neurocognitive deficits present in Val/Val PLWH with high cardiometabolic burden may reflect an inability to compensate for reduced cognitive resources associated with DA dysfunction.

Although limitations in our data prevents us from investigating biological mechanisms that may underlie the interactive effects of COMT, CMRS, and nadir CD4 on NCI, we offer several plausible neurobiological interpretations. Chronic neuroinflammation is a hallmark feature of HIV-related CNS dysfunction77. Immunosuppression, cardiovascular disease, and metabolic syndrome are associated with increased levels of pro-inflammatory biomarkers in the periphery and in CSF, as well as neuroinflammation on magnetic resonance spectroscopy in PLWH11,17,78–80. Limited bioavailability of DA and epinephrine due to high enzymatic activity of COMT may also result in poor neuroinflammatory regulation because catecholamines play a pivotal role in modulating lymphocyte and inflammasome activity81,82. In addition to neuroinflammatory dysregulation, excessive formation of reactive oxygen species and endothelial dysfunction are neurotoxic processes associated with immunosuppression, cardiometabolic risk, and catecholamine metabolism83–89. While our data reflect the neurobehavioral consequences of genetically-driven low DA signaling, poor cardiometabolic health, and more severe HIV disease, studies at a cellular level are needed to elucidate the mechanisms of their interactions.

We acknowledge several limitations to this study. First, the cross-sectional and associative nature of our data prevent us from drawing causal inferences, especially about the relationship between NCI and CMRS in the context of genetic and HIV disease history predictors. Second, we lacked an HIV- uninfected comparison group, hindering our ability to determine the specificity of our findings to PLWH. However, by exploring the conditional effect of nadir CD4 with the J-N technique, we demonstrate how HIV disease severity in a clinically-relevant and well-represented range (i.e., nadir CD4 <180) can modulate the effects of genetic and environmental risk factors for NCI. Third, our results focused on clinically informative risk factors for NCI that may inform future interventions targeting the maintenance of cardiometabolic health (e.g., exercise, diet, sleep) and dopaminergic therapy (e.g., COMT-inhibitors), but our sample comprised men only and therefore limits the applicability of our findings to women. Fourth, we studied the effects of only one variant of COMT, but not other DA-related genetic variants on NCI in PLWH. As is the case with theoretically-driven single SNP analyses, COMT may be in linkage disequilibrium with other SNPs in the DA pathway that could account for the presumed effects of COMT. “Omics” techniques that leverage rich, multi-leveled data (e.g., genetic, transcriptomic, epigenetic) may advance the characterization of complex and subtle HIV-related neurobiological phenotypes6. Given that multiple components of the DA signaling pathway (e.g., receptors, metabolic enzymes, transporters) can be quantified across multiple levels of analysis (e.g., host genetics, microRNA expression, imaging), an “omics” approach has the potential to uncover clusters of DA-related factors that track with intermediate biological phenotypes as well as disease and neurobehavioral endpoints (e.g., NCI).

Taken together, our findings suggest a tripartite model by which genetically-driven low DA reserve, cardiometabolic dysfunction, and history of immunosuppression synergistically enhance risk of NCI among HIV+ men. These interactive effects remain significant in virally suppressed participants receiving cART, suggesting that currently effective HIV treatment alone may not sufficiently mitigate neurocognitive dysfunction associated with the combination of genetic vulnerabilities, historically severe HIV-induced immunosupression, and cardiometabolic risk factors. In addition to cART, adjunctive behavioral therapies that target modifiable lifestyle factors could be considered as a means to address this diverse combination of risk factors90. In particular, interventions to increase physical activity and/or reduce sleep disturbances may help stabilize DA function and cardiometabolic health, reduce inflammatory and oxidative stress burden, and subsequently ameliorate persisting neurocognitive deficits in HIV-infected patients91–95.

Acknowledgments

The Translational Methamphetamine AIDS Research Center (TMARC) is supported by Center award P50DA026306 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) and is affiliated with the University of California, San Diego (UCSD), the Sanford-Burnham Medical Discovery Institute (SBMDI), and the University of California, Irvine (UCI). The TMARC comprises: Administrative Coordinating Core (ACC) – Executive Unit: Director – Igor Grant, M.D.; Co-Directors – Ronald J. Ellis, M.D., Ph.D., Scott L. Letendre, M.D., and Cristian L. Achim, M.D., Ph.D.; Center Manager – Mariana Cherner, Ph.D.; Associate Center Managers – Erin E. Morgan, Ph.D. and Jared Young, Ph.D.; Data Management and Information Systems (DMIS) Unit: Anthony C. Gamst, Ph.D. (Unit Chief), Clint Cushman, B.A. (Unit Manager); ACC – Statistics Unit: Florin Vaida, Ph.D. (Unit Chief), Ian S. Abramson, Ph.D., Reena Deutsch, Ph.D., Anya Umlauf, M.S.; ACC – Participant Unit: J. Hampton Atkinson, M.D. (Unit Chief), Jennifer Marquie-Beck, M.P.H. (Unit Manager); Behavioral Assessment and Medical (BAM) Core – Neuromedical and Laboratory Unit (NLU): Scott L. Letendre, M.D. (Core Co-Director/NLU Chief), Ronald J. Ellis, M.D., Ph.D.; BAM Core – Neuropsychiatric Unit (NPU): Robert K. Heaton, Ph.D. (Core Co-Director/NPU Chief), J. Hampton Atkinson, M.D., Thomas D. Marcotte, Ph.D., Erin E. Morgan, Ph.D., Matthew Dawson (NPU Manager); Neuroimaging (NI) Core: Gregory G. Brown, Ph.D. (Core Director), Thomas T. Liu, Ph.D., Miriam Scadeng, Ph.D., Christine Fennema-Notestine, Ph.D., Sarah L. Archibald, M.A., John R. Hesselink, M.D., Mary Jane Meloy, Ph.D., Craig E.L. Stark, Ph.D.; Neuroscience and Animal Models (NAM) Core: Cristian L. Achim, M.D., Ph.D. (Core Director), Marcus Kaul, Ph.D., Virawudh Soontornniyomkij, M.D.; Pilot and Developmental (PAD) Core: Mariana Cherner, Ph.D. (Core Director), Stuart A. Lipton, M.D., Ph.D.; Project 1: Arpi Minassian, Ph.D. (Project Director), William Perry, Ph.D., Mark A. Geyer, Ph.D., Jared W. Young, Ph.D.; Project 2: Amanda B. Grethe, Ph.D. (Project Director), Susan F. Tapert, Ph.D., Assawin Gongvatana, Ph.D.; Project 3: Erin E. Morgan, Ph.D. (Project Director), Igor Grant, M.D.; Project 4: Svetlana Semenova, Ph.D. (Project Director).; Project 5: Marcus Kaul, Ph.D. (Project Director).

The CNS HIV Anti-Retroviral Therapy Effects Research was supported by awards N01 MH22005, HHSN271201000036C and HHSN271201000030C from the National Institutes of Health. The CNS HIV Anti-Retroviral Therapy Effects Research (CHARTER) group is affiliated with Johns Hopkins University; the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai; University of California, San Diego; University of Texas, Galveston; University of Washington, Seattle; Washington University, St. Louis; and is headquartered at the University of California, San Diego and includes: Director: Igor Grant, M.D.; Co-Directors: Scott L. Letendre, M.D., Ronald J. Ellis, M.D., Ph.D., Thomas D. Marcotte, Ph.D.; Center Manager: Donald Franklin, Jr.; Neuromedical Component: Ronald J. Ellis, M.D., Ph.D. (P.I.), J. Allen McCutchan, M.D.; Laboratory and Virology Component: Scott Letendre, M.D. (Co-P.I.), Davey M. Smith, M.D. (Co-P.I.).; Neurobehavioral Component: Robert K. Heaton, Ph.D. (P.I.), J. Hampton Atkinson, M.D., Matthew Dawson; Imaging Component: Christine Fennema-Notestine, Ph.D. (P.I.), Michael J Taylor, Ph.D., Rebecca Theilmann, Ph.D.; Data Management Component: Anthony C. Gamst, Ph.D. (P.I.), Clint Cushman; Statistics Component: Ian Abramson, Ph.D. (P.I.), Florin Vaida, Ph.D.; Johns Hopkins University Site: Ned Sacktor (P.I.), Vincent Rogalski; Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai Site: Susan Morgello, M.D. (Co-P.I.) and David Simpson, M.D. (Co-P.I.), Letty Mintz, N.P.; University of California, San Diego Site: J. Allen McCutchan, M.D. (P.I.); University of Washington, Seattle Site: Ann Collier, M.D. (Co-P.I.) and Christina Marra, M.D. (Co-P.I.), Sher Storey, PA-C.; University of Texas, Galveston Site: Benjamin Gelman, M.D., Ph.D. (P.I.), Eleanor Head, R.N., B.S.N.; and Washington University, St. Louis Site: David Clifford, M.D. (P.I.), Muhammad Al-Lozi, M.D., Mengesha Teshome, M.D.

Conflicts of Interest and Source of Funding: This research was supported by the NIDA-funded Translational Methamphetamine AIDS Research Center (TMARC) award P50DA026306 (PI: Igor Grant), NIDA award R01DA026334 (PI: Mariana Cherner), and the CNS HIV Anti-Retroviral Therapy Effects Research (CHARTER) study awards N01MH22005, HHSN271201000036C, and HHSN271201000030C. R.S. is supported by NIAAA award T32AA013525 and M.J.M. is supported by NIMH award K23MH105297. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of the United States Government.

Oral presentation delivered at the Interational Neuropsychological Society (INS) Annual Conference, New York, NY (2019, February).

References

- 1.Heaton RK, Clifford DB, Franklin DR Jr., et al. HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders persist in the era of potent antiretroviral therapy: CHARTER Study. Neurology. 2010;75(23):2087–2096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sacktor N, Skolasky RL, Seaberg E, et al. Prevalence of HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders in the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study. Neurology. 2016;86(4):334–340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heaton RK, Marcotte TD, Mindt MR, et al. The impact of HIV-associated neuropsychological impairment on everyday functioning. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2004;10(3):317–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hinkin CH, Hardy DJ, Mason KI, et al. Medication adherence in HIV-infected adults: effect of patient age, cognitive status, and substance abuse. AIDS. 2004;18(Suppl 1):S19–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Everall I, Vaida F, Khanlou N, et al. Cliniconeuropathologic correlates of human immunodeficiency virus in the era of antiretroviral therapy. J Neurovirol. 2009;15(5–6):360–370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Levine AJ, Panos SE, Horvath S. Genetic, transcriptomic, and epigenetic studies of HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;65(4):481–503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Valcour V, Sithinamsuwan P, Letendre S, Ances B. Pathogenesis of HIV in the central nervous system. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2011;8(1):54–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saylor D, Dickens AM, Sacktor N, et al. HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder — pathogenesis and prospects for treatment. Nat Rev Neurol. 2016;12(4):234–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gonzalez E, Kulkarni H, Bolivar H, et al. The influence of CCL3L1 gene-containing segmental duplications on HIV-1/AIDS susceptibility. Science. 2005;307(5714):1434–1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barbaro G Heart and HAART: Two sides of the coin for HIV-associated cardiology issues. World J Cardiol. 2010;2(3):53–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Canizares S, Cherner M, Ellis RJ. HIV and aging: effects on the central nervous system. Semin Neurol. 2014;34(1):27–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McCutchan JA, Marquie-Beck JA, Fitzsimons CA, et al. Role of obesity, metabolic variables, and diabetes in HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder. Neurology. 2012;78(7):485–492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Valcour VG, Shikuma CM, Shiramizu BT, et al. Diabetes, insulin resistance, and dementia among HIV-1-infected patients. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;38(1):31–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sattler FR, He J, Letendre S, et al. Abdominal obesity contributes to neurocognitive impairment in HIV-infected patients with increased inflammation and immune activation. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;68(3):281–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wright E, Grund B, Robertson K, et al. Cardiovascular risk factors associated with lower baseline cognitive performance in HIV-positive persons(e–Pub ahead of print). Neurology. 2010;75(10):864–873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yu B, Pasipanodya E, Montoya JL, et al. Metabolic Syndrome and Neurocognitive Deficits in HIV infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2019; Epub Ahead of Print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cysique LA, Moffat K, Moore DM, et al. HIV, vascular and aging injuries in the brain of clinically stable HIV-infected adults: a (1)H MRS study. PLoS One. 2013;8(4):e61738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saloner R, Heaton RK, Campbell LM, et al. Effects of comorbidity burden and age on brain integrity in HIV. AIDS. 2019; Epub Ahead of Print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koutsilieri E, ter Meulen V, Riederer P. Neurotransmission in HIV associated dementia: a short review. J Neural Transm (Vienna). 2001;108(6):767–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wayman WN, Chen L, Hu XT, Napier TC. HIV-1 Transgenic Rat Prefrontal Cortex Hyper-Excitability is Enhanced by Cocaine Self-Administration. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2016;41(8):1965–1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kumar AM, Fernandez JB, Singer EJ, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in the central nervous system leads to decreased dopamine in different regions of postmortem human brains. J Neurovirol. 2009;15(3):257–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kumar AM, Ownby RL, Waldrop-Valverde D, Fernandez B, Kumar M. Human immunodeficiency virus infection in the CNS and decreased dopamine availability: relationship with neuropsychological performance. J Neurovirol. 2011;17(1):26–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gelman BB, Lisinicchia JG, Chen T, et al. Prefrontal dopaminergic and enkephalinergic synaptic accommodation in HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders and encephalitis. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2012;7(3):686–700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gelman BB, Spencer JA, Holzer CE 3rd, Soukup VM. Abnormal striatal dopaminergic synapses in National NeuroAIDS Tissue Consortium subjects with HIV encephalitis. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2006;1(4):410–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang GJ, Chang L, Volkow ND, et al. Decreased brain dopaminergic transporters in HIV-associated dementia patients. Brain. 2004;127(Pt 11):2452–2458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee TT, Chana G, Gorry PR, et al. Inhibition of Catechol-O-methyl Transferase (COMT) by Tolcapone Restores Reductions in Microtubule-associated Protein 2 (MAP2) and Synaptophysin (SYP) Following Exposure of Neuronal Cells to Neurotropic HIV. J Neurovirol. 2015;21(5):535–543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen J, Lipska BK, Halim N, et al. Functional analysis of genetic variation in catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT): effects on mRNA, protein, and enzyme activity in postmortem human brain. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;75(5):807–821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sundermann EE, Bishop JR, Rubin LH, et al. Genetic predictor of working memory and prefrontal function in women with HIV. J Neurovirol. 2015;21(1):81–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bousman CA, Cherner M, Glatt SJ, et al. Impact of COMT Val158Met on executive functioning in the context of HIV and methamphetamine. Neurobehav HIV Med. 2010;2010:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dawling S, Roodi N, Mernaugh RL, Wang X, Parl FF. Catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT)-mediated metabolism of catechol estrogens: comparison of wild-type and variant COMT isoforms. Cancer Res. 2001;61(18):6716–6722. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kanasaki K, Palmsten K, Sugimoto H, et al. Deficiency in catechol-O-methyltransferase and 2-methoxyoestradiol is associated with pre-eclampsia. Nature. 2008;453(7198):1117–1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kanasaki M, Srivastava SP, Yang F, et al. Deficiency in catechol-o-methyltransferase is linked to a disruption of glucose homeostasis in mice. Sci Rep. 2017;7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ueki N, Kanasaki K, Kanasaki M, Takeda S, Koya D. Catechol-O-Methyltransferase Deficiency Leads to Hypersensitivity of the Pressor Response Against Angiotensin II. Hypertension. 2017;69(6):1156–1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Annerbrink K, Westberg L, Nilsson S, Rosmond R, Holm G, Eriksson E. Catechol O-methyltransferase val158-met polymorphism is associated with abdominal obesity and blood pressure in men. Metabolism. 2008;57(5):708–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tunbridge EM, Harrison PJ, Warden DR, Johnston C, Refsum H, Smith AD. Polymorphisms in the catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) gene influence plasma total homocysteine levels. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2008;147b(6):996–999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang Y, Chen M, Chen J, et al. Metabolic syndrome in patients taking clozapine: prevalence and influence of catechol-O-methyltransferase genotype. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2014;231(10):2211–2218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ganguly P, Alam SF. Role of homocysteine in the development of cardiovascular disease. Nutr J. 2015;14:6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brunerova L, Potockova J, Horacek J, Suchy J, Andel M. Central dopaminergic activity influences metabolic parameters in healthy men. Neuroendocrinology. 2013;97(2):132–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang GJ, Volkow ND, Logan J, et al. Brain dopamine and obesity. Lancet. 2001;357(9253):354–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hamdi A, Porter J, Prasad C. Decreased striatal D2 dopamine receptors in obese Zucker rats: changes during aging. Brain Res. 1992;589(2):338–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ellis RJ, Badiee J, Vaida F, et al. CD4 nadir is a predictor of HIV neurocognitive impairment in the era of combination antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2011;25(14):1747–1751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tozzi V, Balestra P, Lorenzini P, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for human immunodeficiency virus-associated neurocognitive impairment, 1996 to 2002: Results from an urban observational cohort. J Neurovirol. 2005;11(3):265–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Robertson KR, Smurzynski M, Parsons TD, et al. The prevalence and incidence of neurocognitive impairment in the HAART era. AIDS. 2007;21(14):1915–1921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wilkinson G, Robertson G. Wide Range Achievement Test-4 (WRAT-4). Lutz, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources Inc; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Laatikainen LM, Sharp T, Harrison PJ, Tunbridge EM. Sexually dimorphic effects of catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) inhibition on dopamine metabolism in multiple brain regions. PLoS One. 2013;8(4):e61839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tunbridge EM, Harrison PJ. Importance of the COMT gene for sex differences in brain function and predisposition to psychiatric disorders. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 2011;8:119–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.von Kanel R, Mausbach BT, Dimsdale JE, et al. Regular physical activity moderates cardiometabolic risk in Alzheimer’s caregivers. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011;43(1):181–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Daniels SR, et al. Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome: an American Heart Association/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Scientific Statement. Circulation. 2005;112(17):2735–2752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hodgkinson CA, Yuan Q, Xu K, et al. Addictions biology: haplotype-based analysis for 130 candidate genes on a single array. Alcohol Alcohol. 2008;43(5):505–515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jia P, Zhao Z, Hulgan T, et al. Genome-wide association study of HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder (HAND): A CHARTER group study. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2017;174(4):413–426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Carey CL, Woods SP, Gonzalez R, et al. Predictive validity of global deficit scores in detecting neuropsychological impairment in HIV infection. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2004;26(3):307–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Heaton RK, Miller SW, Taylor MJ, Grant I. Revised Comprehensive Norms for an Expanded Halstead Reitan Battery: Demographically Adjusted Neuropsychological Norms for African American and Caucasian Adults. Lutz, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Heaton RK, Taylor MJ, Manly J. Demographic effects and use of demographically corrected norms with the WAIS-III and WMS-III In: Clinical interpretation of the WAIS-III and WMS-III. San Diego, CA, US: Academic Press; 2003:181–210. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Norman MA, Moore DJ, Taylor M, et al. Demographically corrected norms for African Americans and Caucasians on the Hopkins Verbal Learning Test-Revised, Brief Visuospatial Memory Test-Revised, Stroop Color and Word Test, and Wisconsin Card Sorting Test 64-Card Version. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2011;33(7):793–804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Blackstone K, Moore DJ, Franklin DR, et al. Defining neurocognitive impairment in HIV: deficit scores versus clinical ratings. Clin Neuropsychol. 2012;26(6):894–908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Beck A, Steer R, Brown G. Manual for Beck Depression Inventory II (BDI-II). San Antonio, TX, Psychology Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 57.World Health Organization. Composite Diagnositic International Interview (CIDI, version 2.1). Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 58.MacDonald PL, Gardner RC. Type I error rate comparisons of post hoc procedures for I j Chi-Square tables. Educ Psychol Meas. 2000;60(5):735–754. [Google Scholar]

- 59.West SG, Aiken LS, Krull JL. Experimental personality designs: analyzing categorical by continuous variable interactions. J Pers. 1996;64(1):1–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Heaton RK, Franklin DR, Ellis RJ, et al. HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders before and during the era of combination antiretroviral therapy: differences in rates, nature, and predictors. In: J Neurovirol. Vol 172011:3–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Johnson PO, Neyman J. Tests of certain linear hypotheses and their application to some educational problems. Statistical research memoirs. 1936. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Preacher KJ, Curran PJ, Bauer DJ. Computational tools for probing interactions in multiple linear regression, multilevel modeling, and latent curve analysis. J Educ Behav Stat. 2006;31(4):437–448. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Esarey J, Sumner JL. Marginal effects in interaction models: Determining and controlling the false positive rate. Comp Political Stud. 2015:0010414017730080. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Levine AJ, Reynolds S, Cox C, et al. The longitudinal and interactive effects of HIV status, stimulant use, and host genotype upon neurocognitive functioning. J Neurovirol. 2014;20(3):243–257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Levine AJ, Sinsheimer JS, Bilder R, Shapshak P, Singer EJ. Functional polymorphisms in dopamine-related genes: effect on neurocognitive functioning in HIV+ adults. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2012;34(1):78–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Plomin R, Owen MJ, McGuffin P. The genetic basis of complex human behaviors. Science. 1994;264(5166):1733–1739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Persson N, Lavebratt C, Sundstrom A, Fischer H. Pulse Pressure Magnifies the Effect of COMT Val(158)Met on 15 Years Episodic Memory Trajectories. Front Aging Neurosci. 2016;8:34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Vance DE, Fazeli PL, Dodson JE, Ackerman M, Talley M, Appel SJ. The Synergistic Effects of HIV, Diabetes, and Aging on Cognition: Implications for Practice and Research. J Neurosci Nurs. 2014;46(5):292–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Paula AA, Falcão MC, Pacheco AG. Metabolic syndrome in HIV-infected individuals: underlying mechanisms and epidemiological aspects. AIDS Res Ther. 2013;10(1):32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bennette C, Vickers A. Against quantiles: categorization of continuous variables in epidemiologic research, and its discontents. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2012;12(1):21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kahn R, Buse J, Ferrannini E, Stern M. The metabolic syndrome: time for a critical appraisal: joint statement from the American Diabetes Association and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(9):2289–2304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Holmes ME, Eisenmann JC, Ekkekakis P, Gentile D. Physical activity, stress, and metabolic risk score in 8- to 18-year-old boys. J Phys Act Health. 2008;5(2):294–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Jernigan TL, Archibald SL, Fennema-Notestine C, et al. Clinical factors related to brain structure in HIV: the CHARTER study. J Neurovirol. 2011;17(3):248–257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Munoz-Moreno JA, Perez-Alvarez N, Munoz-Murillo A, et al. Classification models for neurocognitive impairment in HIV infection based on demographic and clinical variables. PLoS One. 2014;9(9):e107625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Goldman-Rakic PS, Muly EC 3rd, Williams GV. D(1) receptors in prefrontal cells and circuits. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2000;31(2–3):295–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lindenberger U, Nagel IE, Chicherio C, Li SC, Heekeren HR, Backman L. Age-related decline in brain resources modulates genetic effects on cognitive functioning. Front Neurosci. 2008;2(2):234–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hong S, Banks WA. Role of the immune system in HIV-associated neuroinflammation and neurocognitive implications. Brain Behav Immun. 2015;45:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Nou E, Lo J, Grinspoon SK. Inflammation, immune activation, and cardiovascular disease in HIV. AIDS. 2016;30(10):1495–1509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Anderson AM, Fennema-Notestine C, Umlauf A, et al. CSF biomarkers of monocyte activation and chemotaxis correlate with magnetic resonance spectroscopy metabolites during chronic HIV disease. J Neurovirol. 2015;21(5):559–567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Longenecker CT, Jiang Y, Yun CH, et al. Perivascular fat, inflammation, and cardiovascular risk in HIV-infected patients on antiretroviral therapy. Int J Cardiol. 2013;168(4):4039–4045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Flierl MA, Rittirsch D, Huber-Lang M, Sarma JV, Ward PA. Catecholamines-crafty weapons in the inflammatory arsenal of immune/inflammatory cells or opening pandora’s box? Mol Med. 2008;14(3–4):195–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Yan Y, Jiang W, Liu L, et al. Dopamine controls systemic inflammation through inhibition of NLRP3 inflammasome. Cell. 2015;160(1–2):62–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Orellana RV, Fonseca HA, Monteiro AM, et al. Association of autoantibodies anti-OxLDL and markers of inflammation with stage of HIV infection. Int J Cardiol. 2013;168(2):1610–1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Pace GW, Leaf CD. The role of oxidative stress in HIV disease. Free Radic Biol Med. 1995;19(4):523–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ho JE, Scherzer R, Hecht FM, et al. The association of CD4+ T-cell counts and cardiovascular risk in treated HIV disease. AIDS. 2012;26(9):1115–1120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Fornoni A, Raij L. Metabolic syndrome and endothelial dysfunction. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2005;7(2):88–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Widmer RJ, Lerman A. Endothelial dysfunction and cardiovascular disease. Glob Cardiol Sci Pract. 2014;2014(3):291–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Sverdlov AL, Figtree GA, Horowitz JD, Ngo DT. Interplay between Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in Cardiometabolic Syndrome. Mediators Inflamm. 2016;2016:8254590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Meiser J, Weindl D, Hiller K. Complexity of dopamine metabolism. Cell Commun Signal. 2013;11(1):34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Montoya JL, Henry B, Moore DJ. Behavioral and Physical Activity Interventions for HAND. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.d’Ettorre G, Ceccarelli G, Giustini N, Mastroianni CM, Silvestri G, Vullo V. Taming HIV-related inflammation with physical activity: a matter of timing. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2014;30(10):936–944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Dirajlal-Fargo S, Webel AR, Longenecker CT, et al. The effect of physical activity on cardiometabolic health and inflammation in treated HIV infection. Antivir Ther. 2016;21(3):237–245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Lin TW, Kuo YM. Exercise benefits brain function: the monoamine connection. Brain Sci. 2013;3(1):39–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Cohrs S, Guan Z, Pohlmann K, et al. Nocturnal urinary dopamine excretion is reduced in otherwise healthy subjects with periodic leg movements in sleep. Neurosci Lett. 2004;360(3):161–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Seay JS, McIntosh R, Fekete EM, et al. Self-reported sleep disturbance is associated with lower CD4 count and 24-h urinary dopamine levels in ethnic minority women living with HIV. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2013;38(11):2647–2653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]