Abstract

Background

Genetic counseling is under-utilized in women who meet family history criteria for BRCA1 and BRCA2 (BRCA1/2) testing, particularly among racial/ethnic minorities. We evaluated the uptake of BRCA1/2 genetic testing among women presenting for screening mammography in a predominantly Hispanic, low-income population of Washington Heights in New York City.

Methods

We administered the Six-Point Scale (SPS) to women presenting for screening mammography at Columbia University Irving Medical Center (CUIMC) in the Washington Heights neighborhood of New York, NY. The SPS is a family history screener to determine eligibility for BRCA1/2 genetic testing based upon U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) guidelines that has been validated in low-income, multiethnic populations.

Results

Among women who underwent screening mammography at CUIMC between November 2014 and June 2016, 3,055 completed the SPS family history screener. Participants were predominantly Hispanic (76.7%), and 12% met family history criteria for BRCA1/2 testing, of whom <5% had previously undergone testing.

Conclusions

In a multiethnic population, a significant proportion met family history criteria for BRCA1/2 testing, but uptake of genetic testing was low. Such underutilization of BRCA1/2 genetic testing among minorities further underscores the need to develop programs to engage high-risk women from underrepresented populations in genetic testing services.

Keywords: family history, hereditary breast and ovarian cancer, BRCA1/BRCA2 genetic testing, racial/ethnic minorities

Introduction

The majority of hereditary breast and ovarian cancers (HBOC) result from pathogenic variants in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes. Women with germline BRCA1/2 mutations have estimated risks of 40–87% and 18–88% for breast cancer, respectively [1]. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends that women whose family history may be associated with an increased risk of BRCA1/2 pathogenic variants undergo genetic counseling and/or testing [2]. However, uptake of genetic counseling for women at high risk for HBOC remains low, even among women with breast cancer [3]. Barriers to genetic counseling include patients’ lack of knowledge of personal medical history and cancer risk, inaccuracies and inconsistencies in documentation of family history of cancer [4–7], and failure of primary care providers and cancer specialists to obtain adequate family cancer histories in order to refer patients at risk for hereditary cancer to genetic counselors [8–10].

Minority populations are even less likely to undergo genetic counseling/testing for HBOC. Among women diagnosed with breast cancer or with a family history of breast and/or ovarian cancer, Hispanic and black women are less likely than white women to undergo testing for BRCA1/2 pathogenic variants, with odds ratios as low as 0.22 [11–13]. Factors that contribute to lower utilization of genetic counseling among minorities include poor understanding of genetic testing, low perception of personal cancer risk, and decreased frequency of reporting of family history compared to whites [14–17]. Despite these limitations, when provided with information about hereditary cancer, Hispanic women express high levels of interest in undergoing genetic counseling/testing, and when offered BRCA1/2 testing based on eligibility, high proportions complete testing [14, 18].

We evaluated the uptake of BRCA1/2 genetic testing among women presenting for screening mammography in a predominantly Hispanic, low-income population of Washington Heights in New York City.

Materials and Methods

We conducted a prospective study called the Know Your Risk: Assessment at Screening (KYRAS)[19]. Women were approached for enrollment during routine screening mammography at the Avon Breast Imaging Center at Columbia University Irving Medical Center (CUIMC) in the Washington Heights neighborhood of New York, NY, and provided written informed consent to complete a baseline survey and to allow access to their electronic health record (EHR). The inclusion criteria included: 1) women age ≥18 years, 2) English or Spanish-speaking, 3) no previous diagnosis of breast cancer. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at CUIMC.

We administered a questionnaire collecting information about sociodemographic characteristics, breast cancer risk factors, and prior BRCA1/2 genetic testing. The Gail model was used to estimate 5-year risk of invasive breast cancer [20]. The questionnaire included the Six-Point Scale (SPS), a family history screener to determine eligibility for BRCA1/2 genetic testing based upon USPSTF guidelines that has been validated in populations of low income, multiethnic women [21, 22]. The SPS is a simplified questionnaire that can be administered in a low-cost, efficient manner, consisting of ten questions that assess eligibility for HBOC genetic testing based upon USPSTF guidelines. The SPS includes questions regarding personal history of breast or ovarian cancer, as well as Jewish ancestry, family history of male breast cancer or ovarian cancer, and history of breast cancer among first- and second-degree female relatives. A score of six or higher on this scale indicates eligibility for HBOC genetic counseling and/or testing.

Results

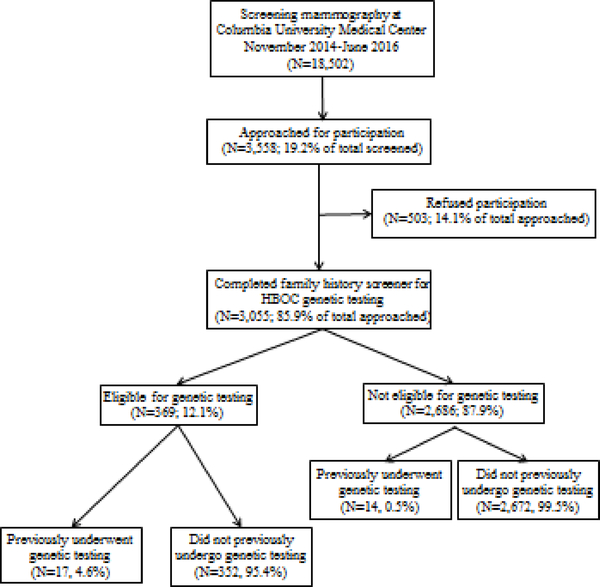

Of 18,502 women who underwent screening mammography at CUIMC between November 2014 and June 2016, 3,558 (19.2%) were approached for participation, 3,055 (85.9% of total approached) completed the SPS family history screener, and 503 (14.1% of total approached) refused participation (Figure 1). The baseline characteristics of women eligible for genetic testing are presented in Table 1. The median age was 58 years (range 29 to 91). Over two-thirds (N = 253) were Hispanic, approximately 11% (N = 39) reported being of Ashkenazi Jewish descent, and about half (N = 190) had a high school education or less. These demographic characteristics were similar to those among the 9,514 of the 18,502 women for whom ethnicity data was available by questionnaire or by EHR data, as published previously [23]. Over 75% of women reported a family history of breast cancer and over 40% a family history of ovarian cancer. About 12% (N=369) women were eligible for genetic testing by the SPS, but only 4.6% (N=17) of eligible women had previously undergone BRCA1/2 genetic testing based upon self-report and EHR review. Fourteen women not eligible for genetic testing by the SPS had undergone genetic testing.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram for the population approached at screening mammography for participation and completion of questionnaire, with responses to questions regarding previous testing for BRCA1/2 pathogenic variants.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of women who completed the Six-Point Scale (SPS) family history screener, stratified by eligibility for BRCA1/2 genetic counseling and/or testing.

| Characteristic | Eligible (n=369) | Ineligible (n=2686) | Total (n=3055) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median age, years (range) | 58(29 – 91) | 59 (33 – 99) | 59 (29 – 99) |

| Race/Ethnicity, N (%) | |||

| Hispanic | 249 (67.5) | 2093 (77.9) | 2342 (76.7) |

| White, Non-Hispanic | 74 (20.1) | 245 (9.1) | 319 (10.4) |

| Black, Non-Hispanic | 33 (8.9) | 257 (9.6) | 290 (9.5) |

| Asian | 7 (1.9) | 48 (1.8) | 55 (1.8) |

| Other | 6 (1.6) | 43 (1.6) | 49 (1.6) |

| Ashkenazi Jewish descent, N (%) | 42 (11.4) | 44 (1.6) | 86 (2.8) |

| Highest level of education, N (%) | |||

| High school diploma, GED, or less | 185 (50.1) | 1666 (62.0) | 1851 (60.6) |

| Vocational, technical, or military | 5 (1.4) | 38 (1.4) | 43 (1.4) |

| Some college or university | 56 (15.2) | 342 (12.7) | 398 (13.0) |

| Associate’s or bachelor’s degree | 56 (15.2) | 390 (14.5) | 446 (14.6) |

| Graduate or professional degree | 67 (18.2) | 247 (9.2) | 314 (10.3) |

| Unknown | 3 (0.1) | 3 (0.1) | |

| Family history of breast cancer, N (%) | 292 (79.1) | 527 (19.6) | 819 (26.8) |

| Family history of ovarian cancer, N (%) | 149 (40.4) | 141 (5.2) | 290 (9.5) |

| Reported prior BRCA1/2 testing, N (%) | 17 (4.6) | 14 (0.5) | 31 (1.0) |

| Negative genetic test result | 13 (3.5) | 11 (0.4) | 12 (0.4) |

| Pathogenic variant in BRCA1/2 | 2 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.0) |

| Unknown result | 2 (0.5) | 3 (0.1) | 4 (0.1) |

Discussion

We found that in our multiethnic, predominantly Hispanic population presenting for screening mammography, genetic testing for HBOC was significantly underutilized. While 12% of the women who completed the SPS family history screener were eligible for HBOC genetic counseling/testing, less than 5% of those eligible reported previous testing for BRCA1/2 pathogenic variants. This finding of underutilization of HBOC genetic testing among minorities is in agreement with previous studies [11–13].

Such underutilization of HBOC genetic testing among minorities further underscores the need to develop programs to effectively engage high-risk women from underrepresented populations in genetic testing services. Efforts to increase education about and uptake of HBOC genetic counseling/testing have increasingly focused on the use of computer-based decision aids (DAs) for both patients and providers, including online family pedigree tools such as iPrevent, Pedigree Assessment Tool (PAT), OPERA, and Cancer in the Family [24–27]. A recent systematic review of decision aids for cancer care decisions, including genetic testing, found that the use of decision aids resulted in improved patient knowledge and accuracy of risk perception, decreased decisional conflict, reduced clinician-directed decision making, and fewer patients being indecisive[28]. Our research group has developed a web-based decision aid for patients and an EHR-embedded breast cancer risk navigation tool for primary care providers. We are currently evaluating their effectiveness in increasing appropriate uptake of BRCA1/2 genetic counseling in a randomized controlled trial [29]. Our goals are to better integrate HBOC risk assessment into primary care and expand access to BRCA1/2 testing to a broader population of high-risk women.

Another challenge to expanding access to genetic testing and counseling for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer is that current guidelines for eligibility have the potential to miss women with pathogenic variants, including in BRCA1/2. Recently, an analysis of nearly 1,000 women with a diagnosis of breast cancer who had not previously undergone single- or multigene testing found that approximately half of the women did not meet National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines for genetic testing; however, when these women subsequently underwent multigene panel testing, the percentage who were found to have pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants was similar between the groups of women meeting and not meeting NCCN guidelines (9.4% vs. 7.9%, respectively, with p=0.4241) [30]. These findings highlight the limitations of current family history guidelines in identifying women who would benefit from genetic counseling and testing services for HBOC, even among patients already diagnosed with breast cancer. There has been discussion not only about modifying current guidelines to refer all women diagnosed with breast cancer for genetic testing regardless of family history, but also about implementing universal screening in the general population. A decision-analytic model evaluating the cost-effectiveness of family history-based BRCA1/2 testing compared to population-based multigene panel testing for BRCA1/2 and other moderaterisk pathogenic variants associated with HBOC in the U.S. and U.K. found that population-based testing was more cost-effective and was projected to prevent 1.86% of breast cancers in the U.K. and 1.91% in the U.S.[31]. However, the penetrance of breast and ovarian cancer in carriers of non-BRCA1/2 pathogenic variants is less well-defined, and variants of unknown significance (VUS) can be discovered as part of a multi-gene analysis, leading to potential clinical confusion and unnecessary testing, procedures, anxiety, and costs. As such, the challenge going forward in adopting broader screening guidelines for HBOC is to balance the benefits of identifying women with pathogenic variants who might benefit from additional screening and cancer prevention with the potential harms of over-testing.

The strengths of our study are the multiethnic, predominantly Hispanic population, which is underrepresented in research on HBOC genetic testing. Potential limitations include the recruitment of participants from a single institution at an urban academic medical center and from a population already actively engaged in screening mammography and potentially more likely to have access to the medical system.

In summary, our study identified significant underutilization of genetic counseling/testing for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer in a multiethnic, predominantly Hispanic and less educated population. Further efforts should be made to develop programs to effectively engage high-risk women from underrepresented populations in genetic testing services, as well as to explore potential limitations to current guidelines for HBOC screening that might further contribute to poor uptake of these services.

Acknowledgments

Grant Support: The study was supported by the National Cancer Institute (grant R01 CA177995–01A1, P30 CA013696), National Institutes of Health (U01HG008680, UL1 TR000040), and National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (KL2TR001874–03). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. This study was also supported by an American Cancer Society Research Grant: RSG-17–103-01. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the funder. The funding body has not and will not play any role in the design, conduct, analysis, or writing up of the study.

Footnotes

Declarations of interest: none

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Mavaddat N, Peock S, Frost D, Ellis S, Platte R, Fineberg E, Evans DG, Izatt L, Eeles RA, Adlard J, Davidson R, Eccles D, Cole T, Cook J, Brewer C, Tischkowitz M, Douglas F, Hodgson S, Walker L, Porteous ME, Morrison PJ, Side LE, Kennedy MJ, Houghton C, Donaldson A, Rogers MT, Dorkins H, Miedzybrodzka Z, Gregory H, Eason J, Barwell J, McCann E, Murray A, Antoniou AC, Easton DF, Embrace. Cancer risks for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers: results from prospective analysis of EMBRACE. J Natl Cancer Inst 2013;105:812–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Moyer VA. Risk assessment, genetic counseling, and genetic testing for BRCA-related cancer in women: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Annals of internal medicine 2014;160:271–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Ropka ME, Wenzel J, Phillips EK, Siadaty M, Philbrick JT. Uptake rates for breast cancer genetic testing: a systematic review. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention : a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology 2006;15:840–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Delikurt T, Williamson GR, Anastasiadou V, Skirton H. A systematic review of factors that act as barriers to patient referral to genetic services. Eur J Hum Genet 2015;23:739–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Tang EY, Trivedi MS, Kukafka R, Chung WK, David R, Respler L, Leifer S, Schechter I, Crew KD. Population-Based Study of Attitudes toward BRCA Genetic Testing among Orthodox Jewish Women. Breast J 2017;23:333–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Wideroff L, Garceau AO, Greene MH, Dunn M, McNeel T, Mai P, Willis G, Gonsalves L, Martin M, Graubard BI. Coherence and completeness of population-based family cancer reports. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention : a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology 2010;19:799–810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Mai PL, Garceau AO, Graubard BI, Dunn M, McNeel TS, Gonsalves L, Gail MH, Greene MH, Willis GB, Wideroff L. Confirmation of family cancer history reported in a population-based survey. J Natl Cancer Inst 2011;103:788–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Murff HJ, Greevy RA, Syngal S. The comprehensiveness of family cancer history assessments in primary care. Community Genet 2007;10:174–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Wood ME, Kadlubek P, Pham TH, Wollins DS, Lu KH, Weitzel JN, Neuss MN, Hughes KS. Quality of cancer family history and referral for genetic counseling and testing among oncology practices: a pilot test of quality measures as part of the American Society of Clinical Oncology Quality Oncology Practice Initiative. J Clin Oncol 2014;32:824–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Bell RA, McDermott H, Fancher TL, Green MJ, Day FC, Wilkes MS. Impact of a randomized controlled educational trial to improve physician practice behaviors around screening for inherited breast cancer. J Gen Intern Med 2015;30:334–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Cragun D, Bonner D, Kim J, Akbari MR, Narod SA, Gomez-Fuego A, Garcia JD, Vadaparampil ST, Pal T. Factors associated with genetic counseling and BRCA testing in a population-based sample of young Black women with breast cancer. Breast cancer research and treatment 2015;151:169–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Levy DE, Byfield SD, Comstock CB, Garber JE, Syngal S, Crown WH, Shields AE. Underutilization of BRCA1/2 testing to guide breast cancer treatment: black and Hispanic women particularly at risk. Genet Med 2011;13:349–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Armstrong K, Micco E, Carney A, Stopfer J, Putt M. Racial differences in the use of BRCA1/2 testing among women with a family history of breast or ovarian cancer. Jama 2005;293:1729–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Kinney AY, Gammon A, Coxworth J, Simonsen SE, Arce-Laretta M. Exploring attitudes, beliefs, and communication preferences of Latino community members regarding BRCA1/2 mutation testing and preventive strategies. Genet Med 2010;12:105–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Hann KEJ, Freeman M, Fraser L, Waller J, Sanderson SC, Rahman B, Side L, Gessler S, Lanceley A, team Ps. Awareness, knowledge, perceptions, and attitudes towards genetic testing for cancer risk among ethnic minority groups: a systematic review. BMC Public Health 2017;17:503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Orom H, Cote ML, Gonzalez HM, Underwood W, 3rd, Schwartz AG. Family history of cancer: is it an accurate indicator of cancer risk in the immigrant population? Cancer 2008;112:399–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Orom H, Kiviniemi MT, Underwood W 3rd, Ross L, Shavers VL. Perceived cancer risk: why is it lower among nonwhites than whites? Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention : a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology 2010;19:746–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Komenaka IK, Nodora JN, Madlensky L, Winton LM, Heberer MA, Schwab RB, Weitzel JN, Martinez ME. Participation of low-income women in genetic cancer risk assessment and BRCA 1/2 testing: the experience of a safety-net institution. J Community Genet 2016;7:177–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].McGuinness JE, Ueng W, Trivedi MS, Yi HS, David R, Vanegas A, Vargas J, Sandoval R, Kukafka R, Crew KD. Factors Associated with False Positive Results on Screening Mammography in a Population of Predominantly Hispanic Women. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention : a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology 2018;27:446–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Gail MH, Brinton LA, Byar DP, Corle DK, Green SB, Schairer C, Mulvihill JJ. Projecting individualized probabilities of developing breast cancer for white females who are being examined annually. J Natl Cancer Inst 1989;81:1879–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Joseph G, Kaplan C, Luce J, Lee R, Stewart S, Guerra C, Pasick R. Efficient identification and referral of low-income women at high risk for hereditary breast cancer: a practice-based approach. Public Health Genomics 2012;15:172–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Stewart SL, Kaplan CP, Lee R, Joseph G, Karliner L, Livaudais-Toman J, Pasick RJ. Validation of an Efficient Screening Tool to Identify Low-Income Women at High Risk for Hereditary Breast Cancer. Public Health Genomics 2016;19:342–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Li X, McGuinness JE, Vanegas A, Colbeth H, Vargas J, Sandoval R, Kukafka R, Crew KD. Identifying women at high-risk for breast cancer using data from the electronic health record compared to self-report. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2017;35:e13044–e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Rupert DJ, Squiers LB, Renaud JM, Whitehead NS, Osborn RJ, Furberg RD, Squire CM, Tzeng JP. Communicating risk of hereditary breast and ovarian cancer with an interactive decision support tool. Patient Educ Couns 2013;92:188–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Collins IM, Bickerstaffe A, Ranaweera T, Maddumarachchi S, Keogh L, Emery J, Mann GB, Butow P, Weideman P, Steel E, Trainer A, Bressel M, Hopper JL, Cuzick J, Antoniou AC, Phillips KA. iPrevent(R): a tailored, web-based, decision support tool for breast cancer risk assessment and management. Breast cancer research and treatment 2016;156:171–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Hoskins KF, Zwaagstra A, Ranz M. Validation of a tool for identifying women at high risk for hereditary breast cancer in population-based screening. Cancer 2006;107:1769–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Mackay J, Schulz P, Rubinelli S, Pithers A. Online patient education and risk assessment: project OPERA from Cancerbackup. Putting inherited breast cancer risk information into context using argumentation theory. Patient Educ Couns 2007;67:261–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].McAlpine K, Lewis KB, Trevena LJ, Stacey D. What Is the Effectiveness of Patient Decision Aids for Cancer-Related Decisions? A Systematic Review Subanalysis. JCO Clinical Cancer Informatics 2018:1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Silverman TB, Vanegas A, Marte A, Mata J, Sin M, Ramirez JCR, Tsai W-Y, Crew KD, Kukafka R. Study protocol: a cluster randomized controlled trial of web-based decision support tools for increasing BRCA1/2 genetic counseling referral in primary care. BMC Health Services Research 2018;18:633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Beitsch PD, Whitworth PW, Hughes K, Patel R, Rosen B, Compagnoni G, Baron P, Simmons R. Underdiagnosis of hereditary breast cancer: Are genetic testing guidelines a tool or an obstacle? J Clin Oncol 2018;37:453–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Manchanda R, Patel S, Gordeev VS, Antoniou AC, Smith S, Lee A, Hopper JL, MacInnis RJ, Turnbull C, Ramus SJ, Gayther SA, Pharoah PDP, Menon U, Jacobs I, Legood R. Cost- effectiveness of Population-Based BRCA1, BRCA2, RAD51C, RAD51D, BRIP1, PALB2 Mutation Testing in Unselected General Population Women. J Natl Cancer Inst 2018;110:714–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]