Abstract

The T790M mutation is recognized as a typical mechanism of acquired resistance to first generation of epithermal growth factor receptor-tyrosine kinase inhibitors (EGFR-TKIs) such as gefitinib in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients who are commonly treated by third generation of EGFR-TKI AZD9291 (osimertinib). However, the therapeutic strategy for overcoming acquired resistance to EGFR-TKIs in NSCLC patients without T790M remains to be definitively determined. In the present study, gefitinib-resistant H1650 (H1650GR) or AZD9291 resistant H1975 (H1975AR) was generated by exposing NSCLC cell line H1650 or H1975 to progressively increased concentrations of gefitinib or AZD9291 over 11 months. The cytotoxic effects of gefitinib or AZD9291 in vitro were evaluated via the half maximal inhibitory concentrations (IC50s) determined by the MTT assay. IC50 of gefitinib in H1650GR (50.0±3.0 μM) significantly increased compared with H1650 (31.0±1.0 μM) (p<0.05). Similarly, the IC50 of AZD9291 in H1975AR (10.3± 0.9 μM) significantly increased compared with H1975 (5.5±0.6 μM) (p<0.05). However, IC50 of AZD9291 on H1650GR (8.5 ± 0.5 μM) did not increase compared with H1650 (9.7 ± 0.7 μM). On the other hand, IC50 of AZD9291 on gefitinib-resistant A549 (A549GR established in our previous study) (12.7 ± 0.8 μM) was significantly increased compared with A549 (7.0 ± 1.0 μM) (p<0.05). AZD9291 induced caspase 3/7 activation in A549, H1650, and H1650GR, but not in A549GR. Western blot analyses showed that p-Akt played a key role in determining the sensitivities of A549, A549GR, H1650, and H1650GR to gefitinib or AZD9291. Additionally, increased expression of Twist1 was observed in all cells with acquired EGFR-TKI resistance and knockdown of Twist1 by shRNA was found to significantly enhance the sensitivity of A549GR to gefitinib or AZD9291 via reversing epithelial mesenchymal transition (EMT) and downregulating p-Akt, but not of H1975AR to AZD9291. The enhanced cytotoxic effect of AZD9291 on A549GR by Twist1 knockdown in vitro was further validated by in vivo studies which showed that Twist1 knockdown could lead to significantly delayed tumor growth of A549GR xenograft with increased sensitivity to AZD9291 treatment in nude mice without any observed side toxic effects. In summary, our study demonstrated that the mechanisms of acquired resistance in different NSCLC cell lines treated by even the same EGFR-TKI might be quite different, which provide a rationale for adopting different therapeutic strategies for those NSCLC patients with acquired EGFR-TKI resistance based on different status of heterogeneous mutations.

Keywords: Gefitinib, AZD9291, EGFR-TKI, Drug resistance, p-Akt, Twist1

Introduction

Activating mutation of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) such as EGFR-exon 19 deletion (delE746-A750) in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients is a favorable predictive biomarker for clinical treatment by first-generation of EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) gefitinib (Kazandjian et al 2016; Suda and Mitsudomi 2015). Unfortunately, NSCLC patients with EGFR mutations developed disease progression after gefitinib treatment for 10 to 14 months (Wu and Shih 2018). Only a small percentage of EGFR-TKI acquired resistance in NSCLC patients could be attributed to the appearance of secondary EGFR mutation T790M (Kwak et al 2005), which can be overcome by the third generation of EGFR-TKI AZD9291 (Cross et al 2014). For other mechanisms of EGFR-TKI acquired resistance, optimal treatments are not yet clearly defined. A recent phase-I trial showed that AZD9291 (also known as osimertinib) has certain therapeutic efficacy in T790M-negative NSCLC patients at the dosage of 120 mg/day who demonstrated a 30% response rate (Jänne et al 2015). These results indicate that AZD9291 may overcome acquired resistance of gefitinib through pathways other than targeting T790M.

Persistent Akt activation was a significant feature of acquired EGFR-TKI resistance and p-Akt levels are increased in most clinical specimens obtained from EGFR-mutant NSCLC patients with acquired EGFR-TKI resistance (Jacobsen et al 2017). More importantly, the diversity coupled with unpredictability of mechanisms regarding EGFR-TKI acquired resistance might be associated with convergent activation of the Akt pathway in EGFR-mutant NSCLC, and specifically inhibiting Akt together with EGFR could effectively overcome the acquired resistance in vitro and in vivo (Jacobsen et al 2017). Therefore, the convergent activation of p-Akt might be a valuable therapeutic target or indicator whose inhibition has the potential to combat the molecular heterogeneity of EGFR-TKI acquired resistance. Interestingly, a previous study reported that the irreversible EGFR inhibitor HKI-357, still under investigation in clinical trial, was reported to may circumvent the acquired resistance of gefitinib in gefitinib-resistant H1650 cell line established by colony selection method, which could suppress p-Akt much more effectively compared with gefitinib (Kwak et al 2005).

Twist1, as a pro-metastatic factor, is silenced in most healthy adult tissues but was found to be overexpressed in various types of carcinomas including NSCLC (Gao et al 2015; Lv et al 2015; Pallier et al 2012), which promoted cell motility, invasiveness, and drug resistance through epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) (Brozovic 2017; Gavert and Ben-Ze’ev 2008). Twist1 expression was shown to inhibit the progress of programmed cell death (Puisieux et al 2006) and also override the oncogene-induced premature senescence by suppressing p53- and Rb-dependent pathways (Ansieau et al 2008). The overexpressed Twist1 in primary and metastatic NSCLC has been identified as a critical target for lung cancer therapy. For example, our previous study suggest that Twist1 overexpression was correlated with poor survival in NSCLC patients with high p-4E-BP1 expression, and silencing Twist1 inhibited H1650 xenografted tumor growth in mice (Lv et al 2015). It was also found that silencing of Twist1 by siRNA could significantly sensitize NSCLC cell lines A549 and H1299 to cisplatin via AMPK-activated mTOR inhibition (Jin et al 2012). A recent study demonstrated that Twist1 overexpression in EGFR-mutant lung cancer cells led to EGFR-TKI resistance in vitro and in vivo, and genetic knockdown of Twist1 or pharmacologic inhibition of Twist1 by harmine could enhance erlotinib sensitivity in NSCLC cell line H1650 (Yochum et al 2019). Finally, Twist1 is frequently associated with aberrant hyperactivation of phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt (de Freitas Silva et al 2012; Way et al 2014; Xu et al 2015; Xue et al 2012), which prompted us to explore the internal relationship of Twist1 and PI3K/Akt for overcoming acquired resistance of EGFR-KTI in NSCLC. More importantly, the role of Twist1 downregulation in overcoming acquired resistance of gefitinib in NSCLC cell lines has not been reported before.

Since recent studies revealed that the resistance of EGFR-TKI in NSCLC patients was closely related with heterogeneity of oncogene mutations within individual tumors (Chen et al 2012; Soucheray et al 2015), three cell lines with different EGFR and KRAS mutation status, including A549 (wt-EGFR, KRAS G12S), H1650 (EGFR exon19 delE746-A750, wt-KRAS), and H1975 (EGFR exon20 T790M and exon21 L858R, wt-KRAS), were chosen to investigate the mechanisms of overcoming the acquired resistance of gefitnib or AZD9291 in the present study. In our previous study (Liu and Gao 2017), gefitinib-resistant A549 (A549GR) was established while gefitinib-resistant H1650 (H1650GR) and AZD9291-resistant H1975 (H1975AR) were established in the current study. The responses of A549GR and H1650GR to AZ9291 treatment were compared and the mechanism of AZD9291 to overcome acquired resistance of gefitinib in H1650GR was also explored. Since our previous (Liu and Gao 2017) and current studies demonstrated that overexpressed Twist1 might play an important role in the process of developing acquired resistance to EGFR-TKI, the effect of Twist1 knockdown on the EGFR-TKI sensitivities of A549GR or H1975AR was further investigated using both in vitro and in vivo models.

Materials and Methods

Establishments of EGFR-TKI resistant cell lines and reagents

The NSCLC cell lines A549, H1650, and H1975 were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). A549GR was generated as the method described in our previous study (Liu and Gao 2017). H1650GR or H1975AR was established by the intermittent selection method through exposing H1650 or H1975 to a stepwise increased concentration of gefitinib (30 μM to 60 μM) or AZD9291 (5 μM to 15 μM) for over 11 months, which simulates the median time (6-12 months) for the development of acquired resistance of gefinitib or AZD9291 in clinical applications. A549, H1650, and H1975 (within five passages), A549GR, H1650GR, and H1975AR were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (Thermo scientific, Logan, UT) containing 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin in 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C. For all the in vitro studies, the established A549GR, H1650GR, and H1975AR were cultured in drug-free medium for at least 1 week to eliminate the effects of gefitinib or AZD9291.

Gefitinib (≥98%) was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA) and osimertinib (AZD9291) (>99%) was obtained from Selleckchem (Houston, TX, USA). The stocks of gefitinib (10 mM) and AZD9291 (10 mM) in DMSO were diluted to the required concentrations immediately before use in the growth media. Primary antibodies including EGFR, phospho-EGFR (Tyr1068), p44/42 MAPK (Erk1/2), phospho-p44/22 MAPK (Erk1/2) (Thr202/Tyr204), Akt, phospho-Akt (Ser473), E-cadherin, vimentin, and α-tubulin were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA). Twist1 antibody was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG or anti-mouse IgG, and chemiluminescence kit were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology. Radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) lysis buffer was obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology.

Cell viability assay

Cell viability was evaluated by the MTT assay as described previously (Gao et al 2015; Lu et al 2012; Shao et al 2011). A549, A549GR, H1650, H1650GR, H1975, and H1975AR were treated by gefitinib or AZD9291 at different concentrations for 24 and 48 hrs. Experiments were repeated independently three times.

Luminescent caspase-Glo 3/7 assay

A549, A549GR, H1650, and H1650GR were seeded at a density of 5000 cells in each well of the white-walled 96-well microplate (costar 3610) (Corning Incorporated, Corning, NY, USA) and treated with AZD9291 at concentrations of 5 and 10 μM for 48 hrs. Then 50 μL of caspase-Glo 3/7 reagent (G8090) (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) was added to each well of the plate containing 50 μL of blank, control cells, or treated cells in the culture medium. After shaken at 500 rpm for 30 s, the plate was incubated at room temperature, and the luminescence of each well was read on Synergy™ H4 Hybrid multi-mode microplate reader.

Western blot analyses

A549, A549GR, H1650, and H1650GR exposed to gefitinib or AZD9291 for 48 hrs, and H1975 or H1975AR were analyzed by Western blot as previously described (Lu et al 2012; Lv et al 2015). α-tubulin was used as an internal control.

PCR and T790M mutation analyses

Genomic DNAs from H1650, H1650GR, H1975, and H1975AR were isolated using a DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). EGFR exon 19 and exon 20 were amplified by PCR according to the method established previously (Conde et al 2006). The PCR products were purified by QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and sequenced. For MET, METFR (endogenous control for MET), HER2, and EFTUD2 (endogenous control for HER2), 75 ng of genomic DNA was amplified using SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad). Experiment was performed in triplicate for each group. The PCR primers sequences were reported in the previous studies (Conde et al 2006; Liu and Gao 2017).

Total RNA was isolated from H1650, H1650GR, H1975, and H1975AR using the RNeasy Plus Mini Kit (Qiagen) following the manufacturer protocol. One-step RT-PCR Kit with SYBR green was used for amplification of total mRNA (75 ng) following the manufacturer’s protocol (BioRad, Hercules, CA, USA) and our previous studies (Gao et al 2015; Lu et al 2012; Lv et al 2015). Experiment was performed in triplicate for each group. The PCR primers sequences were reported in the previous studies (Conde et al 2006; Liu and Gao 2017).

Anchorage-independent growth assay

Anchorage-independent growth was determined by soft agar colony formation assay following a previous protocol (Gao et al 2015; Lv et al 2015). Colonies were stained using 0.005% crystal violet, and the number and area of colonies (six randomly selected areas/well) were measured by an image analyzer under a microscope.

Wound healing assay

The wound healing assay (scratch assay) was performed to examine and compare the migration abilities of different cell lines as previously described (Liu and Gao 2017; Lv et al 2015). Briefly, cells were grown to full confluency in 6-well plates and incubated overnight in a serum-free starvation medium. The cell monolayer was scratched with a sterile, fine pipette tip and was kept in an incubator in a serum-free culture medium for 48 hrs. Photographs of the wounded area were taken at the time of wounding and thereafter at 12, 24, and 48 hrs to determine the wound closure rate.

Transwell invasion assay

Transwell assay was performed using cell culture inserts of 6.5 mm diameter (Corning Incorporated) as described previously (Liu and Gao 2017). Pictures of five random areas in each insert were photographed by a microscopy and the number of cells that had reached the underside of the inserts was counted.

Knockdown of Twist1 in A549GR and H1975AR

shRNA plasmid for human Twist1 (TF308556) was obtained from Origene (Rockville, MD, USA). Lipofectamine™ 3000 transfection reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) was used for transfection of Twist1-specific shRNA sequences expressed in pRFP-C-RS vector according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, 2 × 105 cells/well were seeded in a 6-well plate and allowed to grow to 70% confluency. Plasmid with Twist1-shRNA (0.5 μg) or scrambled control plasmid was mixed with 2 μL P3000™ reagent in 200 μL Opti-MEM™ medium, which was mixed with another 200 μL Opti-MEM™ medium containing 2 μL Lipofectamine™ reagent. The mixtures of the transfection reagents were incubated for 15 min and overlaid on the cells for about 6 hrs, into which 400 μL Opti-MEM™ medium was then added. After transfection for 72 hrs, fresh RPMI medium containing 5% FBS was added and the cells were incubated for an additional 48 hrs. Thereafter, the transfected A549GR or H1975AR was selected by puromycin (4 μg/mL). The knockdown of Twist1 expression after transfection was verified by fluorescent imaging, RT-PCR, and Western blot. Twist1-shRNA transfected A549GR (A549GR-KO-T) and H1975AR (H1975AR-KO-T) were subject to MTT assays to determine their sensitives to gefitinib or AZD9291. The sequence of shRNA for knockdown of Twist1 is GCCGACGACAGCCTGAGCAACAGCGAGGA.

Xenograft animal model

The handling of animals was in accordance with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Female athymic mice, 7-8 weeks of age and 17.5 ± 1.8 g in weight (Charles River Laboratory, Waltham, MA) received subcutaneous injections of 1.5 × 106 A549, A549GR, or A549GR-KO-T cells in the lower right flank (n=5/group). Tumor volume was measured after cell injection. For the AZD9291 treatment experiment, mice bearing xenografts (n=4, with the tumor size of approximate 200 mm3) after A549, A549GR, or A549GR-KO-T implantation were given oral gavage of AZD9291 (25 mg/kg) in 1% Polysorbate 80 continuously once daily for 14 consecutive days (Cross et al 2014). Tumor volume was measured twice weekly. The major longitudinal diameter (length) and the major transverse diameter (width) were determined. Tumor volume was calculated based on caliper measurements by the following formula: tumor volume = ½ (length × width2) (Gao et al 2015).

Statistical analysis

Prism 6.0 was used for calculation of the 50% inhibitory concentrations (IC50s). Student t test and one-way ANOVA followed by a Fisher's LSD test were applied to determine the difference in the analytical results of cell viabilities, luminescent caspase-Glo 3/7 assays, qRT-PCR, wound healing assay, anchorage-independent growth assay, transwell invasion assay, and tumor volumes among groups when appropriate. Differences with p<0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

The cytotoxicity of gefitinib or AZD9291 in A549, A549GR, H1650, H1650GR, H1975, and H1975AR

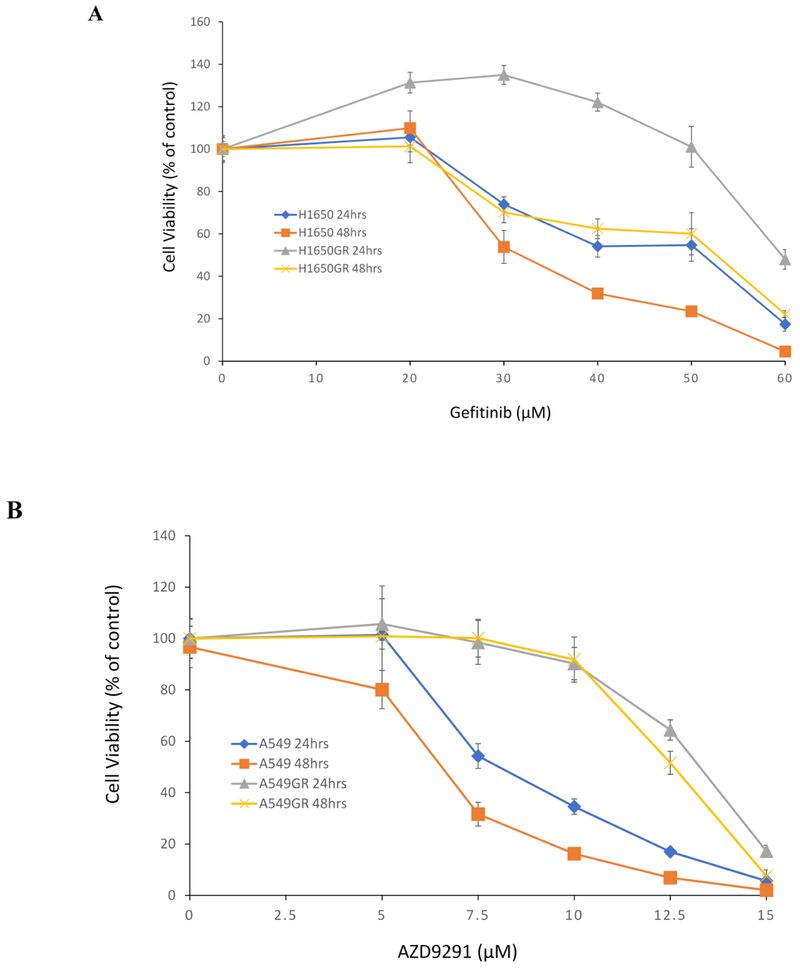

As shown in Figure 1A, the IC50s of gefitinib at 48 hrs in H1650 and H1650GR were 31.0±1.0 μM, and 50.0±3.0 μM, respectively. On the other hand, the IC50s of AZD9291 at 48 hrs in A549 and A549GR were 7.0 ± 1.0 μM and 12.7 ± 0.8 μM, respectively (Figure 1B), while the IC50s of AZD9291 at 48 hrs in H1650 and H1650GR was 9.7 ± 0.7 μM and 8.5 ± 0.5 μM, respectively (Figure 1C). IC50 of AZD9291 significantly increased in A549GR compared with A549 (p<0.05), whereas there was no significant change of IC50 of AZD9291 in H1650GR compared with H1650. H1650GR was not resistant to AZD9291 treatment, which was consistent with the sensitivity of H1650GR to another irreversible EGFR inhibitor HKI-357 reported previously (Kwak et al 2005). Additionally, Figure 1D showed that the IC50 of AZD9291 at 48 hrs in H1975AR (10.3 ± 0.9 μM) significantly increased compared with H1975 (5.5 ± 0.6 μM) (p<0.05).

Figure 1. Cytotoxic effects of gefitinib or AZD9291 on A549, A549GR, H1650, H1650GR, H1975, and H1975AR.

(A) Cytotoxic effects of gefitinib on H1650 and H1650GR at 24 hrs and 48 hrs. (B) Cytotoxic effects of AZD9291 on A549 and A549GR at 24 hrs and 48 hrs. (C) Cytotoxic effects of AZD9291 on H1650 and H1650GR at 24 hrs and 48 hrs. (D) Cytotoxic effects of AZD9291 on H1975 and H1975AR at 48 hrs. Data are expressed as the percentage by comparing to vehicle controls determined by the MTT assay. Values are represented as mean ± SD, n = 6.

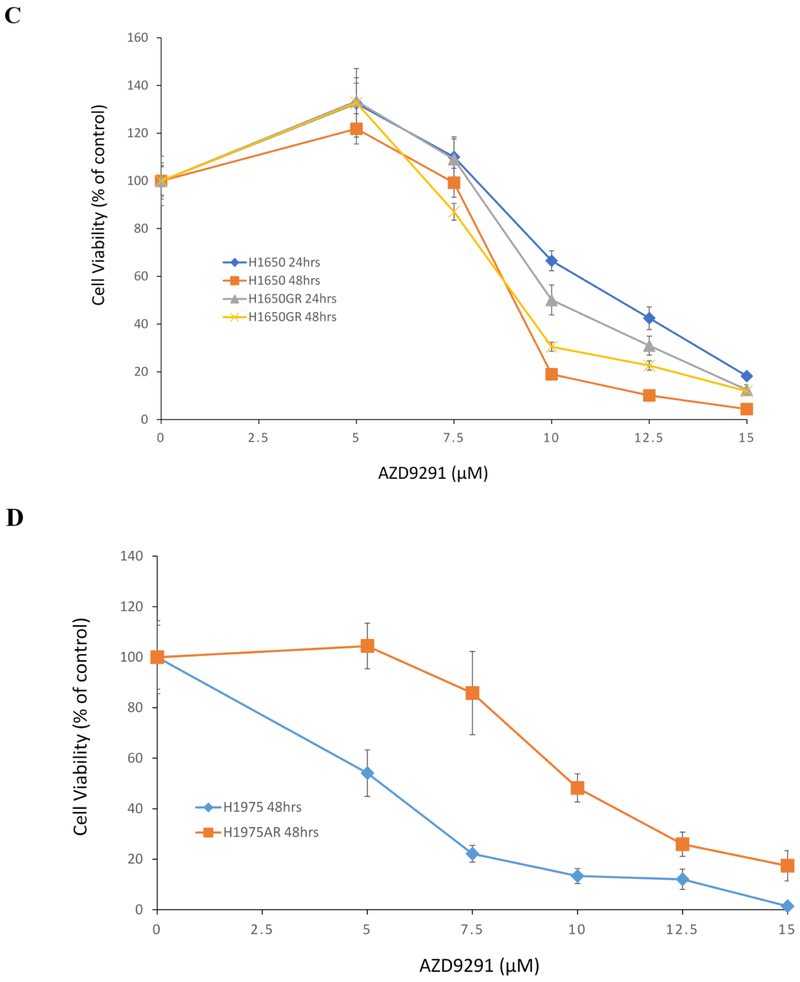

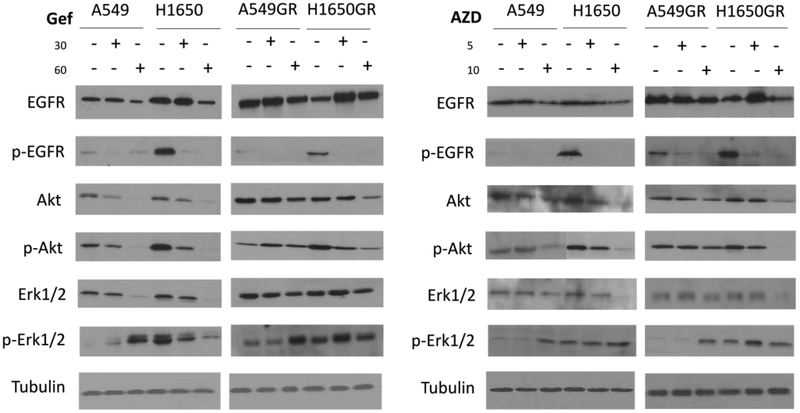

Caspase-3/7 activities in A549, A549GR, H1650, and H1650GR treated by AZD9291

Based on IC50s of AZD9291 determined in our study and concentration ranges of HKI-357 (0-10 μM) in H1650GR used for Western blot analyses reported previously (Kwak et al 2005), AZD9291 at 0, 5, and 10 μM was used for subsequent analyses of caspase-3/7 activities and Western blot. Figure 2A showed that significantly increased caspase-3/7 activities were observed in both H1650 and H1650GR treated by AZD9291 for 48 hrs compared with their respective control in a dose-response manner. As for A549 and A549GR, the only increased caspase-3/7 activities were observed in A549 but not A549GR treated by 10 μM AZD9291. These increased caspase-3/7 activities were verified by apoptosis bodies observed microscopically in A549, H1650, and H1650GR but not A549GR treated by AZD9291 at 10 μM for 48 hrs (Figure 2B).

Figure 2. Caspase 3/7 activities and morphological changes in A549, A549GR, H1650, and H1650GR after AZD9291 treatment at 5 μM (AZD5) and 10 μM (AZD10) for 48 hrs.

(A) Normalized luminescence readings of A549, A549GR, H1650, and H1650GR are compared to the control. Data are means ± SD, n = 3. Mean values of the same cell line containing different letters indicates a significant difference among the treatment groups analyzed by a one-way ANOVA followed by a Fisher's LSD test (p<0.05). Values bearing the letter “a” indicate no significant differences compared with control, those labeled “b” denote a significant difference when compared with the control, and “c” denotes a significant difference when is AZD10 compared with AZD5. (B) Microscopic images (×40) of A549, A540GR, H1650, and H1650G after 5 μM and 10 μM AZD9291 treatments.

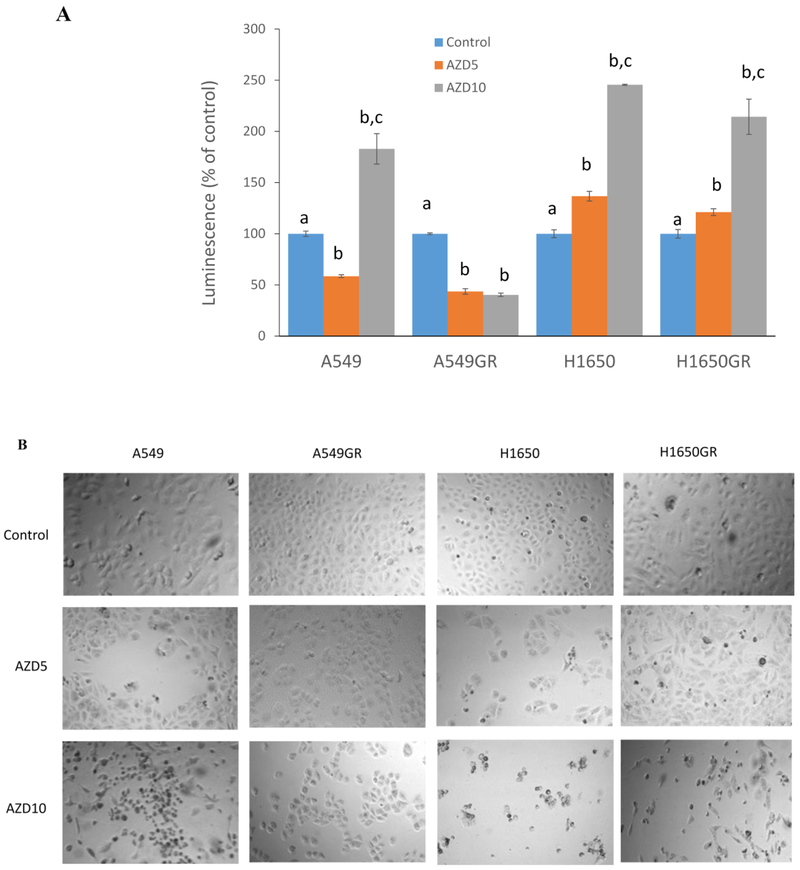

Western blot analyses of EGFR signaling pathways in A549, A549GR, H1650, and H1650GR after gefitinib or AZD9291 treatment

In order to further investigate the mechanisms accounting for acquired resistance of gefitinib overcome by AZD9291, the expression levels of EGFR, p-EGFR (Tyr1068), Akt, p-Akt (Ser473) Erk1/2, and p-Erk1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204) were evaluated. As shown in Figure 3, in gefitinib-treated A549 and H1650, the expressions of EGFR, Akt, p-Akt, and Erk1/2 were significantly downregulated compared with the control in a dose-response manner, and p-EGFR and p-Erk1/2 were downregulated in H1650 compared with the control. On the other hand, p-Erk1/2 was significantly upregulated in gefitinib-treated A549. In gefitinib-treated A549GR, EGFR was downregulated while p-Akt and p-Erk1/2 were significantly upregulated compared with the control. In contrast, in gefitinib-treated H1650GR, EGFR was significantly upregulated, while p-EGFR and p-Akt were remarkably downregulated compared with the control. In both gefitinib-treated A549GR and H1650GR, Akt and Erk1/2 were downregulated compared with the control.

Figure 3. Western blot analyses of protein expressions in A549, A549GR, H1650, and H1650GR after treatments with gefitinib (Gef) at concentrations of 30 μM and 60 μM or AZD9291 (AZD) at concentrations of 5 μM and 10 μM for 48 hrs.

In both AZD9291-treated A549 and H1650, the protein expressions of EGFR, Akt, p-Akt and Erk1/2 were decreased, while p-Erk1/2 was significantly increased compared with the control. Although p-EGFR and Akt were found to dramatically decrease in AZD9291 treated-A549GR and H1650GR compared with the control, it is noticeable that p-Akt and Erk1/2 were decreased remarkably only in H1650GR compared with control, which may explain different sensitivities of A549GR and H1650GR to AZD9291. Significantly increased p-Erk1/2 was observed in A549GR compared with the control.

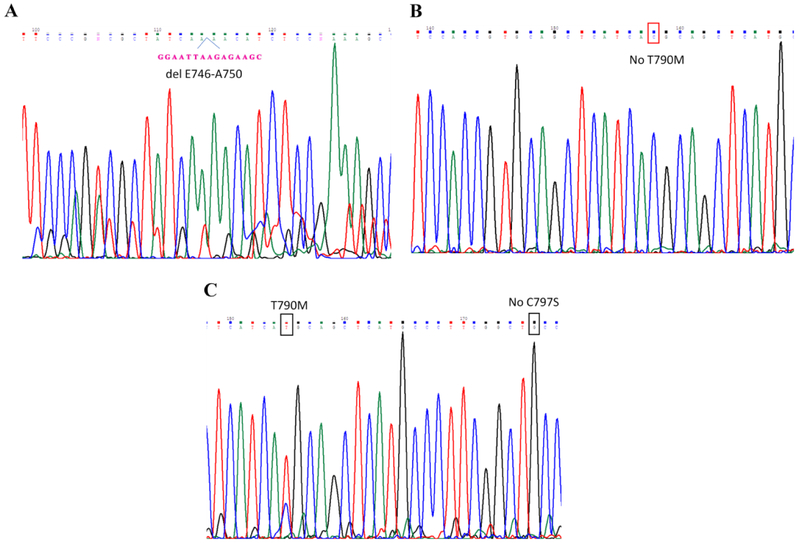

Gene analyses of H1650GR and H1975AR

The sequence analyses of PCR products of EGFR exon 19 and exon 20 demonstrated that there was a typical del E746-A750 mutation in exon 19 but no T790M in exon 20 of H1650GR (Figures 4A&4B), while there was no C797S but typical T790M in H1975AR (Figure 4C). The qRT-PCR results showed that there was no HER2 or MET amplification in H1650GR or H1975AR compared to their parental cells (Figure 4D).

Figure 4. Gene analyses of H1650, H1650GR, H1975, and H1975AR.

(A) DNA sequencing for EGFR exon 19 of H1650GR showing typical delE746-A750 mutation. (B) No T790M (c.2369C > T) was found in EGFR exon 20 of H1650GR. (C) T790M was found and no C797S mutation was found in EGFR exon 20 of H1975AR. (D) qRT-PCR analyses of H1650GR compared to H1650, and H1975AR compared to H1975. Data are means ± SD, n = 3. Mean values of the same gene containing different letters indicates a significant difference between H1650GR and H1650 or between H1975AR and H1975 analyzed by a student T-test (p<0.05).

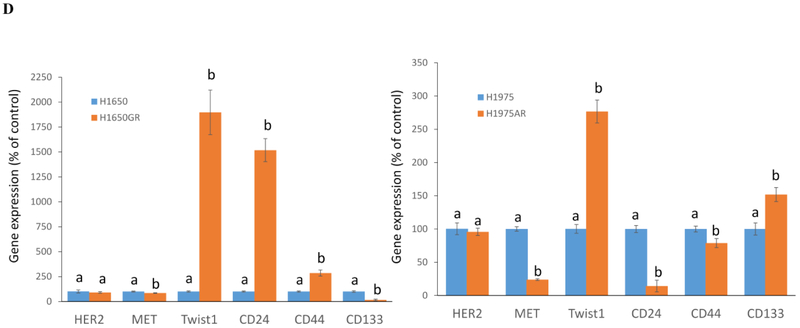

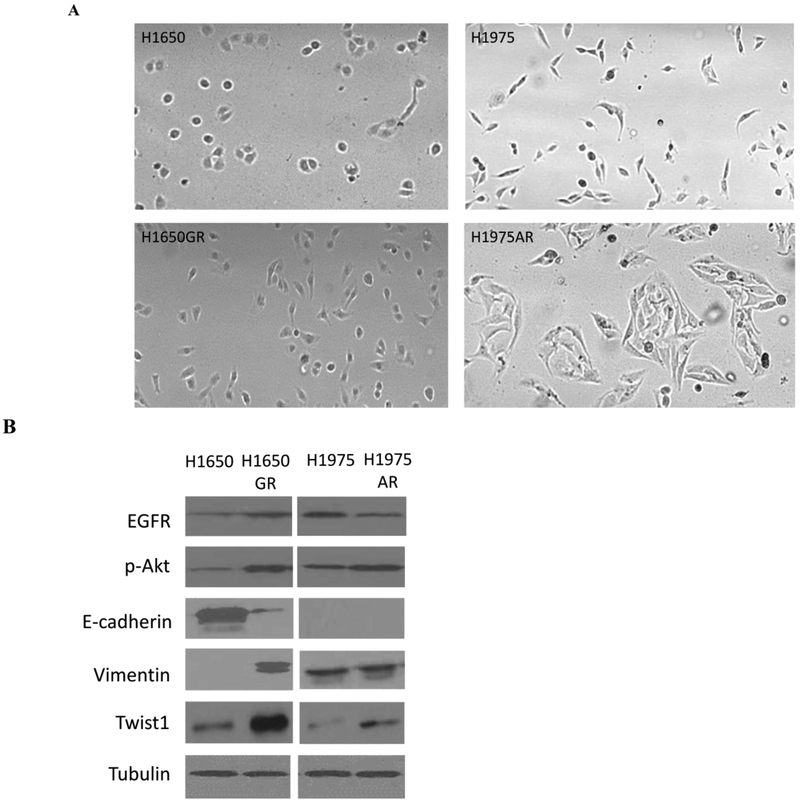

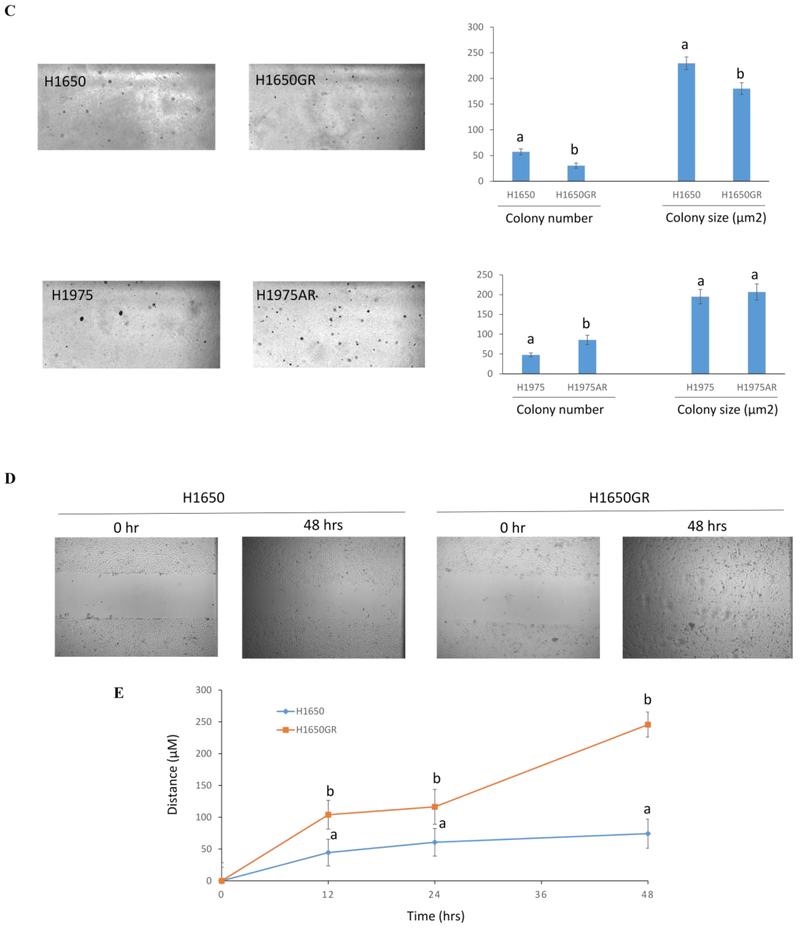

The morphological changes and anchorage-independent growth assay of H1650GR and H1975AR compared with their parental cells

Figure 5A showed that compared to H1650, H1650GR was elongated to spindle shaped, which is similar to the morphological shape change of A549GR compared to A549 (Liu and Gao 2017; Rho et al 2009). On the other hand, H1975AR was much bigger and more fibroblast-like cell shape compared to H1975, which is consistent with the morphological description of AZD9291-resistant H1975 established by a previous study (Tang et al 2016).

Figure 5. Phenotypic characterizations of H1650, H1650GR, H1975, and H1975AR.

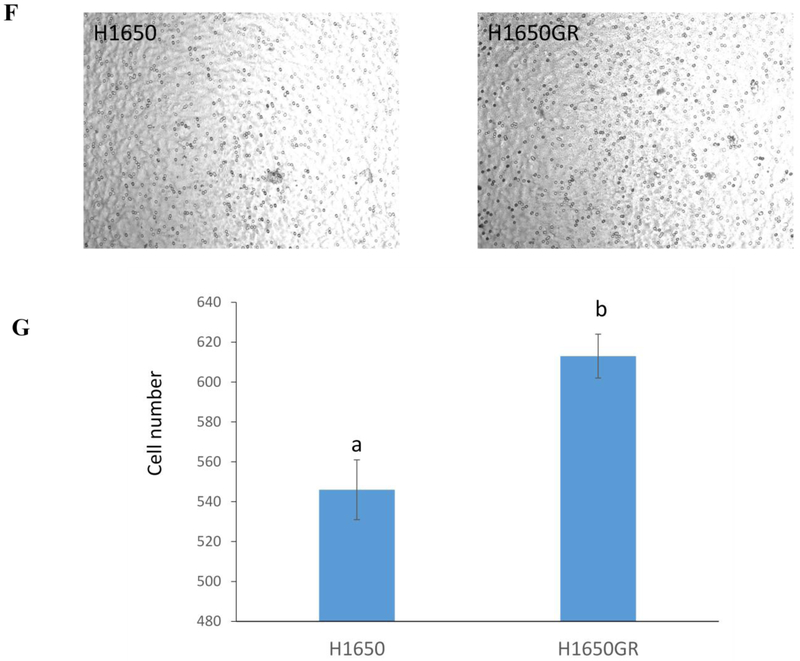

(A) Microscopic images (×40) of H1650, H1650GR, H1975, and H1975AR. (B) Western blot analyses of EGFR, p-Akt, and EMT biomarkers (E-cadherin, Vimentin, and Twist1) in H1650, H1650GR, H1975, and H1975AR. (C) Colony number and size of H1650, H1650GR, H1975 and H1975AR in anchorage-independent growth assay. (D) Microscopic images (×40) of wound healing closures of H1650 and H1650GR obtained at 0 to 48 hrs after pipette scratching. (E) The wound closure rates of H1650GR is significantly larger than H1650 at 12, 24 and 48 hrs (p<0.05). (F) Microscopic images (×200) of cells on the bottom side of cell culture inserts in the transwell invasion assay. (G) The number of cells counted on the bottom side of cell culture inserts in the transwell invasion assay. Data are represented as mean ± SD, n = 12. Different letters indicate a significant difference between H1650GR and H1650 or between H1975AR and H1975 analyzed by a student T-test (p<0.05)

Further Western blot analyses (Figure 5B) showed that classical EMT occurred in H1650GR compared with H1650, which was demonstrated by significantly increased expression of vimentin but reduced expression of E-cadherin. On the other hand, no significant change of E-cadherin or vimentin was observed in H1975AR compared with H1975. The increased Twist1 expression was observed in both H1650GR and H1975AR compared to their parental cells, which was consistent with the result of qRT-PCR (Figure 4D). In addition, the increased expressions of EGFR and p-Akt were observed in H1650GR compared with H1650, while decreased expression of EGFR but increased expression of p-Akt was observed in H1975AR compared with H1975 (Figure 5B).

To compare the tumorigenic potential of H1650 and H1650GR or H1975 and H1975AR, anchorage-independent growth assay was implemented. As shown in Figure 5C, a significant increase in colony number was found in H1975AR compared to H1975. However, significantly decreased colony number and colony size were observed in H1650GR compared to H1650. qRT-PCR results showed that the gene expressions of cancer stem cell (CSC) biomarkers CD24 and CD44 significantly increased but CD133 significantly decreased in H1650GR compared to H1650, while CD24 and CD44 significantly decreased but CD133 significantly increased in H1975AR compared to H1975 (Figure 4D).

Characterizations of H1650 and H1650GR by wound healing assay and transwell invasion assay

The differences in the migration and invasion abilities of H1650 and H1650GR were further examined by wound healing assay and transwell invasion assay. Figures 5D&5E showed that the migration abilities of H1650GR was significantly higher than H1650 at 12, 24, and 48 hrs (p<0.05). Figures 5F&5G showed that H1650GR (613±11) exhibited significantly higher invasion abilities than H1650 (546±15) (p<0.05).

The effects of Twist1 knockdown on sensitivities of A549GR and H1975AR to gefitinib or AZD9291

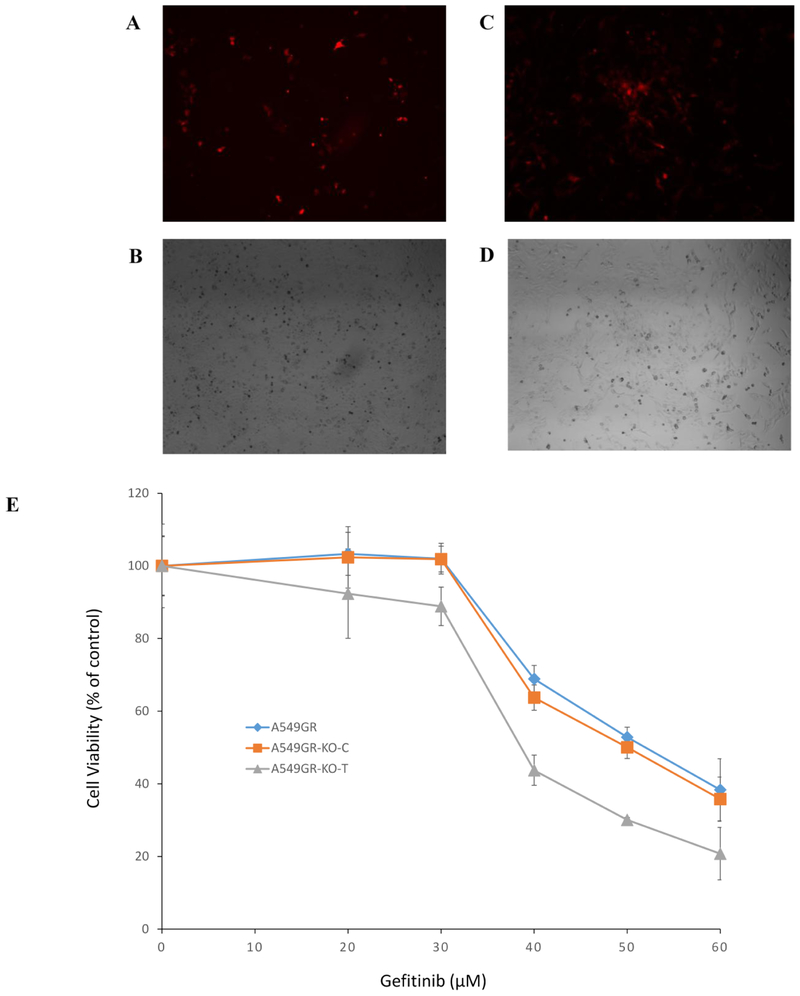

Figures 6A-6D showed that after shRNA transfection, RFP in the Twist1-knockdown A549GR (A549GR-KO-T) or H1975AR (H1975AR-KO-T) could be visible under the fluorescent microscope using TRITC filter.

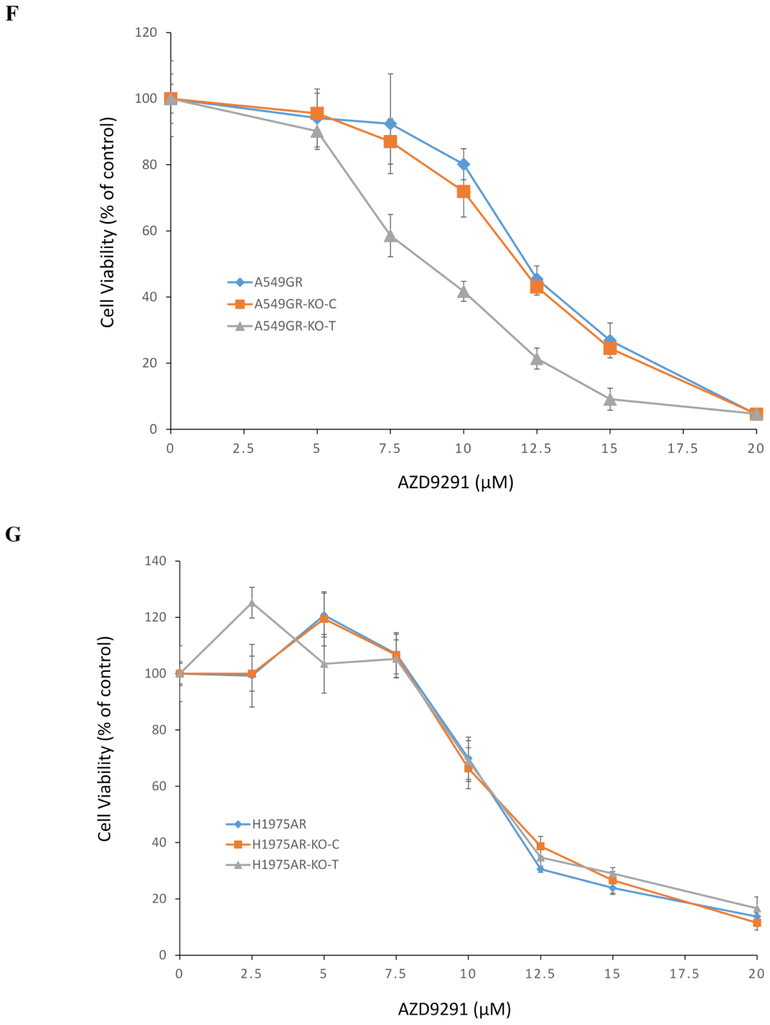

Figure 6. Cytotoxic effects of gefitinib or AZD9291 on A549GR, A549GR-KO-C, A549GR-KO-T, H1975AR, H1975AR-KO-C, and H1975AR-KO-T.

(A) Fluorescent microscopic image (×40) of A549-KO-T using TRITC filter. (B) Bright field image (×40) of A549-KO-T. (C) Fluorescent microscopic image (×40) of H1975-KO-T using TRITC filter. (D) Bright field image (×40) of H1975-KO-T. (E) Cytotoxic effects of gefitinib on A549GR, A549GR-KO-C, and A549GR-KO-T for 48 hrs. (F) Cytotoxic effects of AZD9291 on A549GR, A549GR-KO-C, and A549GR-KO-T for 48 hrs. (G) Cytotoxic effects of AZD9291 on H1975AR, H1975AR-KO-C, and H1975AR-KO-T for 48 hrs. Data are expressed as the percentage by comparing to vehicle controls determined by the MTT assay. Values are represented as mean ± SD, n = 6.

As shown in Figures 6E&6F, compared to A549GR and A549GR transfected with scrambled control sequences (A549GR-KO-C), the sensitivity of A549GR-KO-T to gefitinib or AZD9291 has significantly increased (p<0.05), The IC50 of gefitinib in A549GR and A549GR-KO-C was 51.0 ± 1.0 μM and 50.6 ± 1.6 μM, respectively, while the IC50 of gefitinib in A549GR-KO-T was 35.1 ± 2.0 μM which is close to IC50 of gefitinib in A549 (32.0 ± 2.5 μM) as reported in our previous study (Liu and Gao 2017). Similarly, the IC50 of AZD9291 in A549GR and A549GR-KO-C was 12.0 ±1.0 μM and 11.8 ± 0.7 μM, respectively; while IC50 of AZD9291 in A549GR-KO-T was 8.3 ± 0.6 μM. In contrast, there were no significant differences in sensitivity of H1975AR-KO-T to AZD9291 compared to H1975AR and H1975AR transfected with scrambled control sequences (H1975AR-KO-C) (Figure 6G).

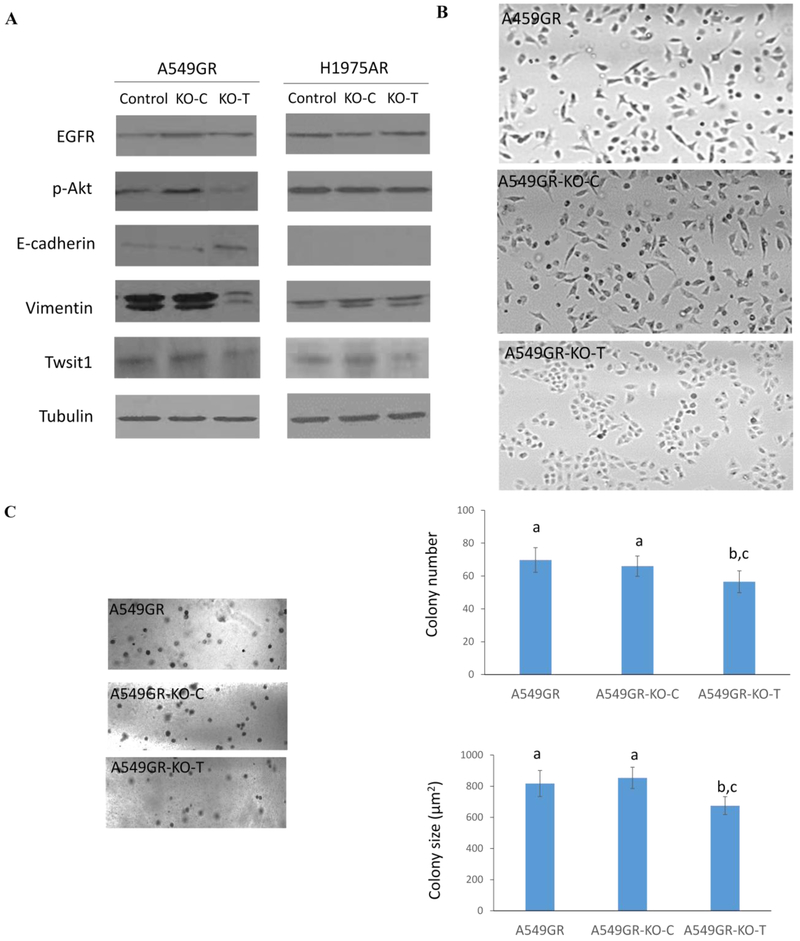

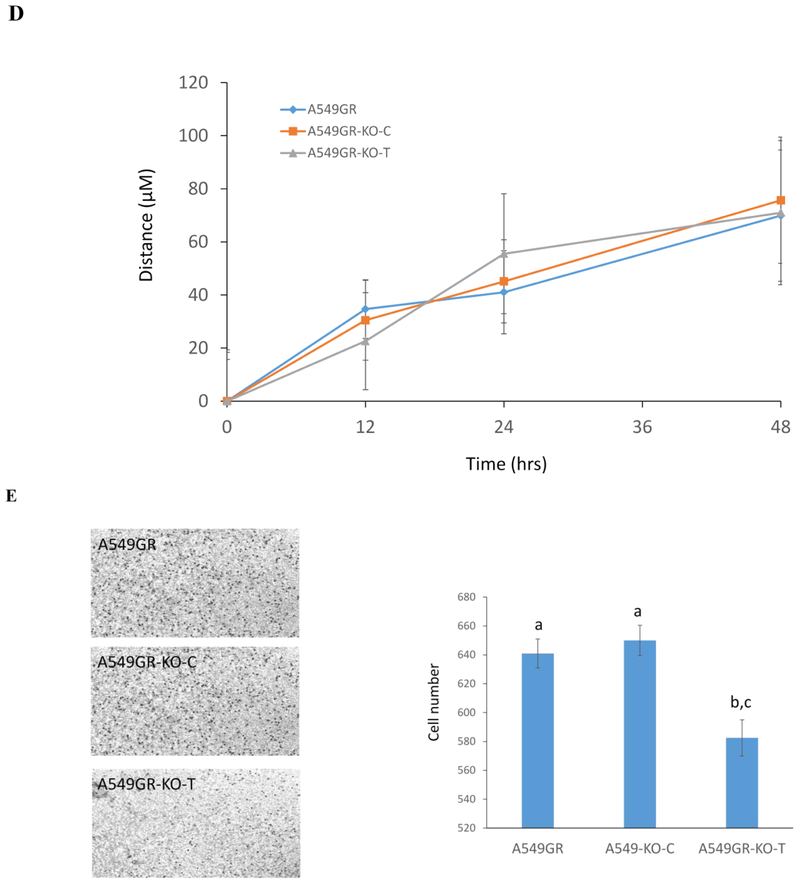

Characterizations of A549GR, A549GR-KO-C, and A549GR-KO-T in Western blot analyses, anchorage-independent growth assay, wound healing assay, and transwell invasion assay

Figure 7A showed that the expression of Twist1 in A549GR-KO-T significantly decreased compared with A549GR or A549GR-KO-C, and Twist1 expression in H1975AR-KO-T also significantly decreased compared with H1975AR and H1975AR-KO-C, which were further validated by qRT-PCR result (Data not shown). More importantly, A549GR-KO-T showed reversed EMT with increased expression of E-cadherin but decreased expression of vimentin compared with A549GR and A549GR-KO-C. On the other hand, such apparent changes of EMT markers were not observed in H1975AR-KO-T compared with H975AR and H1975AR-KO-C. Additionally, p-Akt was significantly decreased in A549-KO-T compared with A549GR and A549GR-KO-C, but not in H1975AR-KO-T compared with H975AR and H1975AR-KO-C.

Figure 7. Characterizations of A549GR, A549GR-KO-C, A549GR-KO-T, H1975AR, H1975AR-KO-C, and H1975AR-KO-T.

(A) Western blot analyses of EGFR, p-Akt, EMT biomarkers including E-cadherin, Vimentin, and Twist1 in A549GR, A549GR-KO-C, A549GR-KO-T, H1975AR, H1975AR-KO-C, and H1975AR-KO-T. (B) Microscopic images (×40) of A549GR, A549GR-KO-C, and A549GR-KO-T (C) Colony number and size of A549GR, A549GR-KO-C, and A549-KO-T in anchorage-independent growth assay. (D) The wound closure rates of A549GR, A549GR-KO-C, and A549-KO-T at 12, 24, and 48 hrs. (E) Microscopic images (×200) of cells and the number of cells counted on the bottom side of cell culture inserts in the transwell invasion assay. Values bearing the letter “a” indicate no significant differences compared with A549GR, those labeled “b” denote a significant difference when compared with A549GR, and “c” denotes a significant difference when A549GR-KO-T was compared with A549GR-KO-C.

As shown in Figure 7B, A549GR-KO-T has undergone a reversed EMT process by losing the spindled-like morphologies observed in A549GR and A549GR-KO-C. In contrast, there were no significant morphological changes observed in H1975AR-KO-T compared with H1975AR and H1975AR-KO-C.

As shown in Figure 7C, significant decreases in colony number and colony size (μm2) were found in A549GR-KO-T compared to A549GR and A549GR-KO-C (p<0.05, colony number: 70 ± 8 in A549GR, 66 ± 6 in A549GR-KO-C, and 55 ± 6 in A549GR-KO-T; colony size: 818 ± 68 in A549GR, 853 ± 84 in A549GR-KO-C, and 675 ± 58 in A549GR-KO-T). No significant differences in migration abilities were found among A549GR, A549GR-KO-C, and A549GR-KO-T in the wound healing assay (Figure 7D). However, A549GR-KO-T (583 ± 11) exhibited a significantly decreased invasion ability compared with A549GR (641 ± 10) and A549GR-KO-C (650 ± 11) in transwell invasion assay (Figure 7E).

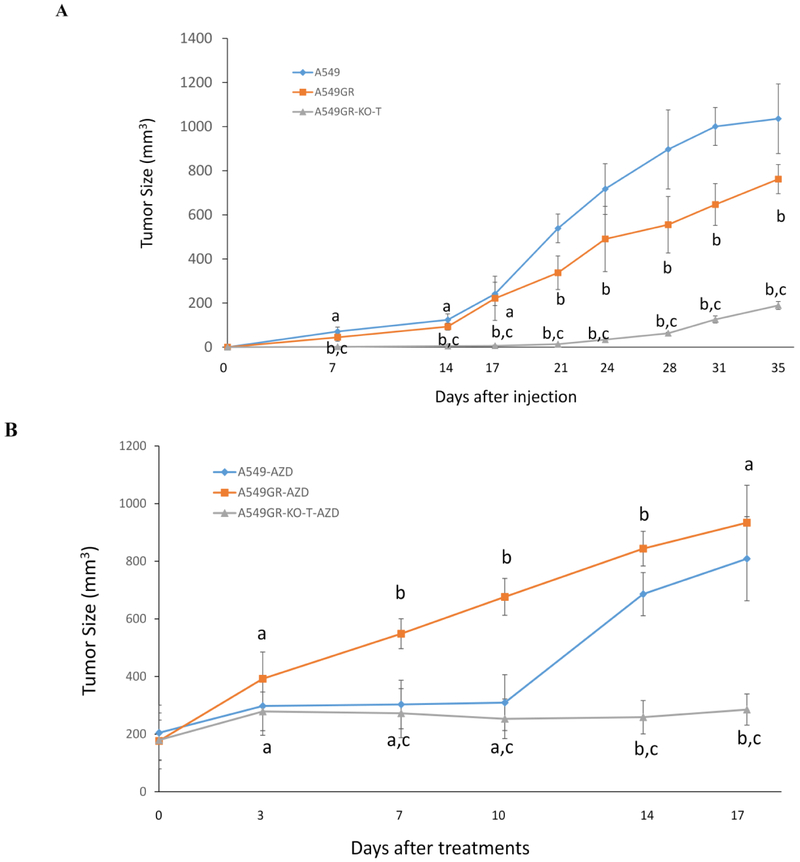

Tumor growth without/with Treatment with AZD9291 in the xenograft nude mouse model

Figure 8A showed that significantly delayed tumor growth was observed in mice injected with A549GR-KO-T compared with those injected with A549 or A549GR (p<0.05). It is noticeable that tumor growth of A549 was significantly faster than A549GR between 21-35 days after cell injections. Significantly delayed tumor growth was also observed in mice with A549GR-KO-T xenograft gavaged by AZD9291 (A549GR-KO-T-AZD) compared to those with A549 xenograft gavaged by AZD9291 (A549-AZD) or A549GR xenograft gavaged by AZD9291 (A549GR-AZD) (Figure 8B). The tumor growth in A549GR-AZD was significantly faster than A549-AZD between 7 and 14 days, suggesting that A549 was more sensitive to AZD9291 treatment than A549GR in vivo. In addition, no differences of the body weight and behavior were observed in the mice implanted with A549, A549GR, and A549GR-KO-T treated by AZD9291 or vehicle control (data not shown).

Figure 8. Tumor growths in xenograft nude mice implanted with A549, A549GR, and A549GR-KO-T.

(A) Tumor growth curves of xenograft nude mice after cell injections. (B) Tumor growth curves of xenograft nude mice gavaged by AZD9291 (25 mg/kg/day for 14 days). Values bearing the letter “a” indicate no significant differences compared with A549, those labeled “b” denote a significant difference when compared with A549, and “c” denotes a significant difference when A549GR-KO-T was compared with A549GR. Values are represented as mean ± SD.

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated that AZD9291 could overcome acquired resistance of gefitinib in H1650GR without T790M. In contrast, AZD9291 could not overcome acquired resistance of gefitinib in A549GR with KRAS mutation. The decreased luminescence values of A549GR treated by 10 μM AZD9291 might be due to the smaller cell number associated with the inhibited proliferation compared with the control as observed microscopically.

In a previous study, gefitinib-resistant PC9 (PC9-G) was established with a significantly increased IC50 of 7.21 ± 1.72 μM compared with IC50 of 0.37 ± 0.033 μM in parental PC9 (Park et al 2017). It was also found that the sensitivity of PC9-G to AZD9291 was similar to that of PC9 (IC50: 12.3 ± 1.4 nM vs. 11.2±3.2 nM) (Park et al 2017). Although PC9-G also harbors the same E746-A750 deletion in EGFR exon 19 as H1650, T790M was detected in EGFR exon 20 of PC9-G, which was considered as the reason why PC9-G and PC9 were almost equally sensitive to AZD9291, a third generation EGFR-TKI, especially effective for treatment of advanced NSCLC patients with T790M (Park et al 2017). However, in our study no T790M was detected in H1650GR, suggesting that there exist other molecular mechanisms responsible for the capacities of AZD9291 to overcome the acquired resistance of gefitinib in NSCLC cell lines such as H1650GR without T790M.

Western blot analyses demonstrated that EGFR expression in H1650GR was significantly higher than H1650. Moreover, the expression of EGFR was reduced in H1650 but significantly increased in H1650GR by the treatment of 60 μM gefitinib, suggesting that overexpression of EGFR might be another mechanism of gefitinib resistance in H1650GR in addition to EMT. However, 10 μM AZD9291 treatment could effectively overcome the acquired resistance of gefitinib in H1650GR by significantly downregulating the expression of EGFR.

As for A549GR, the refractory p-Akt expression of A549GR treated by AZD9291 signified the simultaneous presence of more than one mechanism of acquired resistance besides EMT in A549GR compared with A549 as described in our previous and other researchers’ studies (Jacobsen et al 2017; Liu and Gao 2017). The primary resistance of A549 to EGFR-TKIs could be attributed to its inherent KRAS mutation (Marchetti et al 2009; Massarelli et al 2007) which was also report to cooperate with Twist1 to promote EMT (Ansieau et al 2008). Additionally, the clinical study showed that there was a co-existence of functional KRAS mutations and PI3K/Akt activation in tumors (Polosukhina et al 2017). The results of the present study indicated that the oncogenic cooperation of KRAS mutation and p-Akt activation may also play an important role in the acquired resistance of EGFR-TKIs, the exact mechanisms of which remain to be investigated.

The persistent activation of p-Akt was also reported in the established gefitinib-resistant NSCLC cell lines with EGFR mutations (Koizumi et al 2005; Kwak et al 2005). The primary resistance of H1650 to gefitinib was attributed to the sustained activation of p-Akt compared with gefitinib-sensitive NSCLC cell lines HCC827 and PC-9 (Choi et al 2010). However, in our study AZD9291 significantly suppressed the expression of p-Akt in H1650GR compared with A549GR, which was supposed to be another important mechanism for AZD9291 to overcome acquired resistance of gefitinib in H1650GR besides downregulating EGFR.

C797S mutation is regarded as a principle mechanism of acquired resistance for AZD9291 (Thress et al 2015). However, in the present study no C797S mutation or HER2/MET amplification (Liu and Gao 2017) was detected in H1975AR, suggesting that other molecular mechanisms may exist for AZD9291 resistance. On the other hand, the decreased expression of EGFR and increased expression of p-Akt were observed in H1975AR compare to H1975, which was consistent with the resistant mechanisms of another previously established AZD9291-resistant H1975 (Tang et al 2016). Lung cancer with decreased EGFR expression was reported to be sensitive to the BIM BH3 mimetic drug, navitoclax (ABT-263) (Niederst et al 2015; Xia et al 2017), and the upregulated BIM, as a pro-apoptotic member of Bcl-2 family, was required for apoptosis induced by EGFR-TKIs (Huang and Fu 2015; Xia et al 2017). ABT-263 was also reported to be effective in overcoming the acquired resistance of AZD9291 in AZD9291-resistant H1975 by inhibition of Bcl2 and activation of caspase (Tang et al 2016). This is consistent with the finding reported by another study that pan-Bcl2 inhibitor ABT-737 was effective in overcoming the resistance of AZD9291 in doxycycline inducible Twist1 overexpressing H1975 (Yochum et al 2019).

To our surprise, H1650GR showed a significantly decreased in vitro tumorigenic potential in anchorage-independent growth assay compared with H1650. Further qRT-PCR analyses showed that significant alterations of CSC biomarkers, increased CD24 but decreased CD133, were observed in H1650GR compared with H1650, which is opposite to decreased CD24 but increased CD133 in A549GR with significantly enhanced tumorigenic potential in vitro compared with A549 as reported in our previous study (Liu and Gao 2017). Interestingly, in a previous study an established erlotinib-resistant H1650 (H1650ER) showed a significantly increased in vitro tumorigenic potential in anchorage-independent growth assay compare with H1650 (Ghosh et al 2012). However, it is also noticeable that the expression of CD133 in H1650ER was much higher than in H1650 (Ghosh et al 2012). Combined with the increased CD133 in H1975AR compared to H1975 as shown in the present study, these results may indicate that the expression of CD133 had a positive correlation with in vitro tumorigenic potential in anchorage-independent growth assay. More importantly, the comparison of in vitro tumorigenic potential of H1650ER and H1650GR suggests that the treatment of gefitinib may generate much less CSCs than erlotinib in some NSCLC patients with EGFR exon 19 activating mutation and the residue H1650GR would be more easily controlled by subsequent treatment of AZD9291. On the other hand, our study showed that H1650GR still had significantly higher migration and invasion abilities than H1650 in vitro, which might be associated with EMT changes in H1650GR compared with H1650.

Our previous study showed that A549GR has an increased expression of Twist1 compared with A549 (Liu and Gao 2017). Moreover, downregulation of Twist1 has been identified as an important pathway for reducing drug resistance by recent studies (Jin et al 2012). In the present study knockdown of Twist1 by shRNA significantly increased the sensitivities of A549GR-KO-T to gefitinib or AZD9291 compared to A549GR and A549GR-KO-C. At the same time, it was found that knockdown of Twist1 reversed the expression of EMT biomarkers such as vimentin and E-cadherin in A549GR-KO-T compared to A549GR and A549GR-KO-C, which provides a possible explanation for why decreased Twist1 could reduce the EGFR-TKI acquired resistance. Interestingly, p-Akt was significantly downregulated in A549GR-KO-T compared to A549GR and A549GR-KO-C in the present study, suggesting that Twsit1 can have a significant effect on activation of Akt signaling pathway which was also reported to play an important role in the direct induction of EMT and have a positive correlation with Twist1 expression in different types of cancers (de Freitas Silva et al 2012; Way et al 2014; Xu et al 2015).

A previous study (Rho et al 2009) showed that the acquired resistance of gefitinib in A549GR with persistent activation of p-Akt was attributed to EMT which could be induced by TGF-β1 treatment. This supposition was further demonstrated by another study (Xue et al 2012) revealing that there was a cross-talk between PI3K/Akt and TGF-β signaling axes mediated by Twist1 phosphorylation which upregulated TGF-β2 leading to hyperactivation of P13K/Akt and increased lung metastasis. It may further explain why knockdown of Twist1 in our study could lead to reduced drug resistance, reversed EMT, and decreased p-Akt in A549GR. It was also demonstrated (Burns et al 2013) that Twist1 cooperated with mutant KRAS to induce lung adenocarcinoma in transgenic mouse models and silencing of Twist1 in KRAS mutant NSCLC cell lines (such as A549) led to dramatic growth inhibition as well as KRAS-induced senescence or even apoptosis. Since KRAS is one of the most frequently mutated oncogenes in NSCLC with an occurrence of about 30% in lung adenocarcinomas, it become an appealing therapeutic target for NSCLC treatment (Tomasini et al 2016). However, no targeted therapy has yet been approved for treatment of KRAS-mutant NSCLC, which is still under investigation in the preclinical studies (Caiola et al 2018; Lito et al 2016). Therefore, development of Twist1 inhibitors for pharmaceutical applications may represent an alternative therapeutic strategy not only to treat KRAS-driven tumor malignancies including NSCLC (Yochum et al 2017) but also to overcome drug resistance relevant to EMT and p-Akt activation.

On the other hand, knockdown of Twist1 in H1975AR-KO-T did not reduce the acquired resistance of AZD9291 compared with H1975AR. Considering that EMT was not the characteristic change in H1975AR compared with H1975, it is plausible that reducing EGFR-TKI resistance via inhibiting the expression of Twist1 is only effective for those resistant cell lines with apparent EMT changes compared with their parental cell lines. Since H1975 is mesenchymal at basal state (Pallier et al 2012), the mechanisms of acquired resistance to AZD9291 in H1975AR was not dependent on Twist1-mediated EMT process observed in our study. A previous study (Yochum et al 2019) showed that Twist1 overexpression in H1975 could lead to suppression of BIM expression, which is a member of Bcl-2 family that promoted apoptosis (O'Connor et al 1998) and was required for EGFR TKI-induced apoptosis (Yochum et al 2019). However, results from the same study (Yochum et al 2019) showed that Twist1 knockdown did not enhance the sensitivity of H1975 to AZD9291 even in the presence of Bcl2 inhibitor ABT-737, which may provide additional explanations to findings in our study that Twist1 knockdown in H1975AR-KO-T did not reduce the acquired resistance of AZD9291. On the other hand, different from H975, both A549 and H1650 are epithelial at basal state where Twist1 acts as a negative regulator of epithelial marker E-cadherin (Khan et al 2013). EMT driven by upregulated Twist1 conferred acquired resistance of gefitinib in A549GR or H1650GR as observed in our previous (Liu and Gao 2017) and the current studies. Similarly, a previous study (Hwang et al 2017) reported that dramatically increased Twist1 expression endowed acquired resistance of gefitinib to another epithelial NSCLC cell line HCC827 (HCC827GR) with an apparent EMT change. The study (Hwang et al 2017) also showed that p-Akt was not diminished by gefitinib in HCC827GR as compared with HCC827, suggesting persistent Akt activation as a possible mechanism of EGFR-TKI acquired resistance in NSCLC. These results indicated that the importance of Twist1 inhibition in overcoming the acquired resistance might very well be proportional to the degree of EMT progression accompanied by the dramatically upregulated Twist1. This hypothesis is further evidenced by our observation that transfection of H1650GR with Twist1 shRNA plasmid directly killed H1650GR which showed a more significantly distinctive profiles of EMT biomarkers including E-cadherin, vimentin, and Twist1 than H1650 even compared with EMT changes of A549 to A549GR.

In our animal study, it was observed that A549GR-KO-T xenograft resulted in a significantly delayed tumor growth compared with A549GR and A549 xenograft in nude mice. The anchorage-independent growth assay and transwell invasion assay in vitro revealed that A459GR-KO-T showed a significantly decreased tumorigenic potential and invasion ability compared with A549GR, which could explain the significantly delayed tumor growth of A549GR-KO-T xenograft compared with A549GR xenograft observed in vivo. In addition, it was observed in our study that the proliferate rate of A549GR was much lower that of A549 in vitro (data not shown), which may be due to the existence of quiescent and slow-cycling stem cell populations in the A549GR and other types of drug resistant cancer cells reported by our and other previous studies (El Khoury et al 2016; Liu and Gao 2017; Moore and Lyle 2011). This may explain the phenomenon observed in our animal study that A549GR xenograft grew slower than A549-control xenograft after cell injection. Although AZD9291 is a third generation of EGFR-TKI showing an effective therapy for lung patients with EGFR-sensitive and resistant mutations, it was shown by our animal study, at least, to decelerate the speed of tumor growth of A549-AZD xenograft compared with A549GR-AZD xenograft treated by the maximum gavage dosing of AZD9291 (25 mg/kg/day) reported (Cross et al 2014). The observed much slower growth rate of A549GR-KO-T xenograft and significantly higher sensitivity of A549GR-KO-T to AZD9291 than A549GR may contribute to the significantly delayed tumor growth of A549GR-KO-T-AZD xenograft compared to both A549-AZD and A549GR-AZD xenografts.

In addition to p-Akt and Twist1 inhibitions, the most straightforward strategy for overcoming other non-T790M mediated resistance mechanisms is a combination of an EGFR-TKI and molecular targeted therapeutics that inhibit the resistance mechanisms (Suda et al 2017b). Other non-T790M mediated resistance mechanisms include preexistence of MET (Ou et al 2016) or HER2 gene amplification (Takezawa et al 2012), activations of alternative bypass pathways such as IGF-1R (insulin like growth factor 1 receptor) or NF-kB (nuclear factor kappa light chain enhancer of activated B cells) (Suda et al 2017a; Suda et al 2017b), survival signaling from fibroblasts (Suda et al 2017a), poor vascularization mediated resistance caused by poor drug penetration plus hypoxia (Suda et al 2017a), and phenotypic changes like small cell lung cancer (SCLC) transformation (Watanabe et al 2013) and EMT (Suda et al 2017b). SCLC transformation in NSCLC patients as a mechanism of acquired resistance was commonly treated with SCLC regimens with cytotoxic chemotherapy (Watanabe et al 2013). MET-TKIs such as crizotinib combined with EGFR-TKIs showed dramatic responses in NSCLC patients with acquired resistance to EGFR-TKIs via MET gene amplification (Ou et al 2016). However, no MET amplification was observed in three established resistant cell lines from our studies. Activations of alternative pathways such as IGF-1R or NF-kB are considered as reversible drug-tolerant state (Suda et al 2017a), and inhibitions of these pathways were shown to eliminate persisting drug-tolerant cells or prevent acquired resistance to EGFR-TKIs in preclinical studies (Lantermann et al 2015; Sharma et al 2010) but without clinical verifications (Suda et al 2017a). To overcome EGFR-TKI acquired resistance associated with poor vascularization, the combination of bevacizumab (an antiangiogenic monoclonal antibody targeting vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)) with EGFR-TKI erlotinib has shown dramatic improvement of progression-free survival (PFS) compared to erlotinib alone (16.0 months versus 9.7 months) in clinical settings (Seto et al 2014).

To overcome acquired resistance of gefitinib or erlotinib, besides aforementioned therapeutic strategies, the anti-EGFR antibody drugs such as cetuximab combined with irreversible EGFR-TKIs such as afatinib demonstrated robust clinical activity in NSCLC patients with or without T790M (Janjigian et al 2014). The combination of AZD9291 with another anti-EGFR antibody drug necitumumab is also undergoing clinical trials currently (Suda et al 2017b). Therefore, whether the anti-EGFR antibody drugs combined with EGFR-TKIs would have a synergistic effect on overcoming the acquired resistance of EGFR-TKIs is worthwhile to be investigated in our future studies. Recently, the importance of microRNAs (miRNAs) in the EMT and/or EGFR-TKI resistance and their potential for clinical applications have been recognized (Brozovic 2017; Han et al 2015; Ricciuti et al 2015). For example, a recent study showed that the introduction of miRNA-200c significantly suppressed the cell viability of gefitinib-resistant HCC4006 (HCC4006-GR) with reversed EMT characters demonstrated by significant downregulation of vimentin and upregulation of E-cadherin (Sato et al 2017). However, the cell viability of parental HCC4006 was not affected by introduction of miRNA-200c (Sato et al 2017). Additionally, previous studies demonstrated miRNAs could significantly repress Twist1 translation (Nairismagi et al 2013) or suppress cell growth and cell invasiveness in various NSCLC cell lines via inhibiting IGF-1R or NF-kB signaling pathway (Han et al 2015). Since many genes like Twist1 may not be druggable using small molecule inhibitors or monoclonal antibodies, the effect of miRNA-based therapy on overcoming acquired resistance of EGFR-TKIs warrants further investigations in the future.

Conclusions

The present study found that AZD9291 could effectively overcome the acquired resistance of gefitinib in H1650GR without T790M by inhibiting p-Akt and EGFR. On the other hand, the cross-resistance to AZD9291 was found in A549GR which showed a convergent activation of p-Akt refractory to AZD9291 treatment. Further CSC marker analyses showed that H1650GR has a significantly decreased expression of CD133 compared with H1650, which may explain why H1650GR showed a significantly decreased tumorigenic potential in anchorage-independent growth assays. The acquired resistance of A549GR was significantly reduced by knockdown of Twist1 with shRNA which showed significantly increased sensitivities to gefitinib or AZD9291. Further mechanism investigation showed that knockdown of Twsit1 in A549GR not only reversed EMT but also downregulated p-Akt. The in vivo study also demonstrated that knockdown of Twist1 in A549GR resulted in significantly delayed tumor growth and increased sensitization to AZD9291 compared with A549 and A549GR. However, the same strategy of Twsit1 knockdown is not effective for overcoming acquired resistance of AZD9291 in H1975AR without C797S mutation, of which the resistant mechanism is not through EMT but through decreased expression of EGFR. Taken together, our finding demonstrated that the mechanisms of acquired resistance in different NSCLC cell lines treated by even the same EGFR-TKI might be quite different, which provide a rationale for adopting different therapeutic strategies for those NSCLC patients with acquired EGFR-TKI resistance based on oncogenic mutation heterogeneity.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

This research was supported by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R15ES026789. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethics approval

All procedures performed in animal studies were in accordance with the ethical standards and guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

References

- Ansieau S, Bastid J, Doreau A et al. (2008) Induction of EMT by twist proteins as a collateral effect of tumor-promoting inactivation of premature senescence. Cancer Cell 14(1):79–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brozovic A (2017) The relationship between platinum drug resistance and epithelial–mesenchymal transition. Arch Toxicol 91(2):605–619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns TF, Dobromilskaya I, Murphy SC et al. (2013) Inhibition of TWIST1 leads to activation of oncogene-induced senescence in oncogene-driven non–small cell lung cancer. Mol Cancer Res 11(4):329–338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caiola E, Frapolli R, Tomanelli M et al. (2018) Wee1 inhibitor MK1775 sensitizes KRAS mutated NSCLC cells to sorafenib. Sci Rep 8(1):948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen ZY, Zhong WZ, Zhang XC et al. (2012) EGFR mutation heterogeneity and the mixed response to EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors of lung adenocarcinomas. Oncologist 17(7):978–985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi YJ, Rho JK, Jeon BS et al. (2010) Combined inhibition of IGFR enhances the effects of gefitinib in H1650: a lung cancer cell line with EGFR mutation and primary resistance to EGFR-TK inhibitors. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 66(2):381–388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conde E, Angulo B, Tang M et al. (2006) Molecular context of the EGFR mutations: evidence for the activation of mTOR/S6K signaling. Clin Cancer Res 12(3):710–717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross DA, Ashton SE, Ghiorghiu S et al. (2014) AZD9291, an irreversible EGFR TKI, overcomes T790M-mediated resistance to EGFR inhibitors in lung cancer. Cancer Discov 4(9):1046–1061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Freitas Silva BS, Yamamoto FP, Pontes FSC et al. (2012) TWIST and p-Akt immunoexpression in normal oral epithelium oral dysplasia and in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal 17(1):e29–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Khoury F, Corcos L, Durand S, Simon B, Jossic C (2016) Acquisition of anticancer drug resistance is partially associated with cancer stemness in human colon cancer cells. Int J Oncol 49(6):2558–2568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao W, Lu C, Chen L, Keohavong P (2015) Overexpression of CRM1: a characteristic feature in a transformed phenotype of lung carcinogenesis and a molecular target for lung cancer adjuvant therapy. J Thorac Oncol 10(5):815–825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavert N, Ben-Ze’ev A (2008) Epithelial–mesenchymal transition and the invasive potential of tumors. Trends Mol Med 14(5):199–209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh G, Lian X, Kron SJ, Palecek SP (2012) Properties of resistant cells generated from lung cancer cell lines treated with EGFR inhibitors. BMC Cancer 12:95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han F, He J, Li F et al. (2015) Emerging roles of microRNAs in EGFR-targeted therapies for lung cancer. Biomed Res Int 2015:672759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang L, Fu L (2015) Mechanisms of resistance to EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Acta Pharm Sin B 5(5):390–401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang W, Chiu YF, Kuo MH et al. (2017) Expression of neuroendocrine factor VGF in lung cancer cells confers resistance to EGFR kinase inhibitors and triggers epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Cancer Res 77(11):3013–3026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen K, Bertran-Alamillo J, Molina MA et al. (2017) Convergent Akt activation drives acquired EGFR inhibitor resistance in lung cancer. Nat Commun 8(1):410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janjigian YY, Smit EF, Groen HJ et al. (2014) Dual inhibition of EGFR with afatinib and cetuximab in kinase inhibitor–resistant EGFR-mutant lung cancer with and without T790M mutations. Cancer Discov 4(9):1036–1045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jänne P, Ahn M, Kim D et al. (2015) LBA3 A phase I study of AZD9291 in patients with EGFR-TKI-resistant advanced NSCLC–updated progression free survival and duration of response data. Ann Oncol 26(suppl_1):i60 [Google Scholar]

- Jin H, Hong S, Woo S et al. (2012) Silencing of Twist1 sensitizes NSCLC cells to cisplatin via AMPK-activated mTOR inhibition. Cell Death Dis 3(6):e319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazandjian D, Blumenthal GM, Yuan W et al. (2016) FDA approval of gefitinib for the treatment of patients with metastatic EGFR mutation–positive non–small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res 22(6):1307–1312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan MA, Chen HC, Zhang D, Fu J (2013) Twist: a molecular target in cancer therapeutics. Tumor Biol 34(5):2497–2506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koizumi F, Shimoyama T, Taguchi F, Saijo N, Nishio K (2005) Establishment of a human non small cell lung cancer cell line resistant to gefitinib. Int J Cancer 116(1):36–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwak EL, Sordella R, Bell DW et al. (2005) Irreversible inhibitors of the EGF receptor may circumvent acquired resistance to gefitinib. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102(21):7665–7670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lantermann AB, Chen D, McCutcheon K et al. (2015) Inhibition of casein kinase 1 alpha prevents acquired drug resistance to Erlotinib in EGFR-mutant non–small cell lung cancer. Cancer Res 75(22):4937–4948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lito P, Solomon M, Li LS, Hansen R, Rosen N (2016) Allele-specific inhibitors inactivate mutant KRAS G12C by a trapping mechanism. Science 351(6273):604–608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z, Gao W (2017) Leptomycin B reduces primary and acquired resistance of gefitinib in lung cancer cells. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 335:16–27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu C, Shao C, Cobos E, Singh KP, Gao W (2012) Chemotherapeutic sensitization of leptomycin B resistant lung cancer cells by pretreatment with doxorubicin. PLoS One 7(3):e32895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lv T, Wang Q, Cromie M et al. (2015) Twist1-mediated 4E-BP1 regulation through mTOR in non-small cell lung cancer. Oncotarget 6(32):33006–33018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchetti A, Milella M, Felicioni L et al. (2009) Clinical implications of KRAS mutations in lung cancer patients treated with tyrosine kinase inhibitors: an important role for mutations in minor clones. Neoplasia 11(10):1084–1092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massarelli E, Varella-Garcia M, Tang X et al. (2007) KRAS mutation is an important predictor of resistance to therapy with epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors in non–small-cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res 13(10):2890–2896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore N, Lyle S (2011) Quiescent, slow-cycling stem cell populations in cancer: a review of the evidence and discussion of significance. J Oncol 2011:396076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nairismägi ML, Füchtbauer A, Labouriau R, Bramsen JB, Füchtbauer EM (2013) The proto-oncogene TWIST1 is regulated by microRNAs. PLoS One 8(5):e66070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niederst MJ, Sequist LV, Poirier JT et al. (2015) RB loss in resistant EGFR mutant lung adenocarcinomas that transform to small-cell lung cancer. Nat Commun 6:6377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor L, Strasser A, O'Reilly LA et al. (1998) Bim: a novel member of the Bel-2 family that promotes apoptosis. EMBO J 17(2):384–395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ou SI, Agarwal N, Ali SM (2016) High MET amplification level as a resistance mechanism to osimertinib (AZD9291) in a patient that symptomatically responded to crizotinib treatment post-osimertinib progression. Lung Cancer 98:59–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pallier K, Cessot A, Côté JF et al. (2012) TWIST1 a new determinant of epithelial to mesenchymal transition in EGFR mutated lung adenocarcinoma. PLoS One 7(1):e29954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park MY, Jung MH, Eo EY et al. (2017) Generation of lung cancer cell lines harboring EGFR T790M mutation by CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing. Oncotarget 8(22):36331–36338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polosukhina D, Love HD, Correa H et al. (2017) Functional KRAS mutations and a potential role for PI 3K/AKT activation in Wilms tumors. Mol Oncol 11(4):405–421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puisieux A, Valsesia-Wittmann S, Ansieau S (2006) A twist for survival and cancer progression. Br J Cancer 94(1):13–17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rho JK, Choi YJ, Lee JK et al. (2009) Epithelial to mesenchymal transition derived from repeated exposure to gefitinib determines the sensitivity to EGFR inhibitors in A549, a non-small cell lung cancer cell line. Lung Cancer 63(2):219–226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricciuti B, Mecca C, Cenci M et al. (2015) miRNAs and resistance to EGFR—TKIs in EGFR-mutant non-small cell lung cancer: beyond ‘traditional mechanisms’ of resistance. Ecancermedicalscience 9:569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato H, Shien K, Tomida S et al. (2017) Targeting the miR-200c/LIN28B axis in acquired EGFR-TKI resistance non-small cell lung cancer cells harboring EMT features. Sci Rep 7:40847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seto T, Kato T, Nishio M et al. (2014) Erlotinib alone or with bevacizumab as first-line therapy in patients with advanced non-squamous non-small-cell lung cancer harbouring EGFR mutations (JO25567): an open-label, randomised, multicentre, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol 15(11):1236–1244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao C, Lu C, Chen L et al. (2011) p53-Dependent anticancer effects of leptomycin B on lung adenocarcinoma. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 67(6):1369–1380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma SV, Lee DY, Li B et al. (2010) A chromatin-mediated reversible drug-tolerant state in cancer cell subpopulations. Cell 141(1):69–80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soucheray M, Capelletti M, Pulido I et al. (2015) Intratumoral heterogeneity in EGFR mutant NSCLC results in divergent resistance mechanisms in response to EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibition. Cancer Res 75(20):4372–4383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suda K, Bunn PA Jr, Rivard CJ, Mitsudomi T, Hirsch FR (2017a) Primary double-strike therapy for cancers to overcome EGFR kinase inhibitor resistance: proposal from the bench. J Thorac Oncol 12(1):27–35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suda K, Mitsudomi T (2015) Role of EGFR mutations in lung cancers: prognosis and tumor chemosensitivity. Arch Toxicol 89(8):1227–1240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suda K, Rivard CJ, Mitsudomi T, Hirsch FR (2017b) Overcoming resistance to EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors in lung cancer, focusing on non-T790M mechanisms. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther 17(9):779–786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takezawa K, Pirazzoli V, Arcila ME et al. (2012) HER2 amplification: a potential mechanism of acquired resistance to EGFR inhibition in EGFR-mutant lung cancers that lack the second-site EGFRT790M mutation. Cancer Discov 2(10):922–933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang ZH, Jiang XM, Guo X et al. (2016) Characterization of osimertinib (AZD9291)-resistant non-small cell lung cancer NCI-H1975/OSIR cell line. Oncotarget 7(49):81598–81610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thress KS, Paweletz CP, Felip E et al. (2015) Acquired EGFR C797S mutation mediates resistance to AZD9291 in non–small cell lung cancer harboring EGFR T790M. Nat Med 21(6):560–562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomasini P, Walia P, Labbe C, Jao K, Leighl N (2016) Targeting the KRAS pathway in non-small cell lung cancer. Oncologist 21(12):1450–1460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe S, Sone T, Matsui T et al. (2013) Transformation to small-cell lung cancer following treatment with EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors in a patient with lung adenocarcinoma. Lung Cancer 82(2):370–372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Way TD, Huang JT, Chou CH et al. (2014) Emodin represses TWIST1-induced epithelial–mesenchymal transitions in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cells by inhibiting the β-catenin and Akt pathways. Eur J Cancer 50(2):366–378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu SG, Shih JY (2018) Management of acquired resistance to EGFR TKI–targeted therapy in advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Mol Cancer 17(1):38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia J, Bai H, Yan B et al. (2017) Mimicking the BIM BH3 domain overcomes resistance to EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors in EGFR-mutant non-small cell lung cancer. Oncotarget 8(65):108522–108533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu W, Yang Z, Lu N (2015) A new role for the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway in the epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Cell Adh Migr 9(4):317–324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue G, Restuccia DF, Lan Q et al. (2012) Akt/PKB-mediated phosphorylation of Twist1 promotes tumor metastasis via mediating cross-talk between PI3K/Akt and TGF-β signaling axes. Cancer Discov 2(3):248–259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yochum ZA, Cades J, Mazzacurati L et al. (2017) A First-in-Class TWIST1 Inhibitor with Activity in Oncogene-Driven Lung Cancer. Mol Cancer Res 15(12):1764–1776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yochum ZA, Cades J, Wang H et al. (2019) Targeting the EMT transcription factor TWIST1 overcomes resistance to EGFR inhibitors in EGFR-mutant non-small-cell lung cancer. Oncogene 38:656–670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.