Abstract

Purpose:

Social support has been identified as a determinant of physical activity (PA), but research has been primarily cross-sectional, with mixed findings for different Hispanic subgroups and limited longitudinal research with Hispanics. The purpose of this study is to assess the longitudinal associations of social support with PA in Hispanics on the Texas-Mexico Border.

Design and sample:

We used 2 time points of data collected from Hispanic adults in the Cameron County Hispanic Cohort (N = 588).

Measures:

We collected social support for PA and self-reported leisure-time PA.

Analysis:

We used cross-lagged panel models to assess the association between friend support, family support, family punishment (criticizing or complaining) and PA over time.

Results:

Although social support overall was low for PA, fully adjusted cross-lagged panel models indicated that time 1 friend support was associated with time 2 PA (adjusted rate ratio = 1.02, 95% confidence interval = 1.00 −1.04), though family support was not associated with time 2 PA. In males, time 1 friend support was inversely associated with time 2 family punishment.

Conclusion:

As expected, the directionality of the relation appears to be from social support to PA. Friend support appears to be predictive of PA in Hispanics, whereas family support is not. This should be considered in intervention development, particularly because familismo (commitment and mutual obligation to family) is considered to be a strong value in these communities.

Keywords: social support, opportunity, strategies, racial minority groups, underserved populations, specific populations, supportive environments, opportunity, strategies, fitness, interventions, low education, underserved populations, specific populations, physical activity, health disparities

Purpose

Hispanics have lower levels of leisure-time physical activity (PA) than non-Hispanic whites.1 Social support, or assistance received from important others, has been identified as a correlate for PA.2,3 A recent systematic review concluded that there is longitudinal evidence to support the relation between friend support and PA though not enough to support the relation between family support and PA.4 Although none of the longitudinal studies involved majority Hispanic samples, cross-sectional studies with Hispanics have also found friend, though not family support, to be associated with PA.5,6 Despite these findings, especially in light of the limited longitudinal data as well as the strong Hispanic value of familismo, or commitment and mutual obligation to family, we hypothesized that family support would be positively associated with PA. The purpose of this study was to assess the longitudinal associations of both friend and family social support for PA with PA in Hispanic adults in the Lower Rio Grande Valley on the Texas-Mexico Border. We also examined trends across sex and acculturation to note possible differences in the social support-PA relationship.

Methods

Design and Sample

This study is a secondary analysis of Cameron County Hispanic Cohort data.7,8 Cameron County Hispanic Cohort (n = 2,815) is an ongoing longitudinal study examining health conditions among Hispanics, predominately Mexican Americans, living along the US-Mexico border who were randomly selected from US Census Bureau tracts/blocks and recruited at their homes. Questionnaires were administered by study staff during visits to the clinical research unit. To be included in the present study, individuals had to have at least 2-points of social support and PA data, thus we excluded individuals who did not complete the psychosocial and/or behavior questionnaire at an initial (n = 1,356) or follow-up (n = 785) assessment, or who had missing data on key study variables (n = 75) or extreme values (n = 11). Thus, our analytic sample included the 588 individuals who had 2 time points of PA and social support data collected at least 90 days apart, to ensure temporality. This study was approved by the institutional review board.

Measures

Social support for PA was collected using a validated scale that includes 10 questions on family and 10 questions on friend support for PA, as well as 2 questions on family punishment (criticizing and complaining) for PA.9 For the Spanish version, we translated and back-translated the items. On a 5-point scale, participants respond how often a family member and/or friend has said or done something over the previous 3 months. All items include a 5-point scale from “never” to “very often”. For example, participants respond to the statement “Gave you encouragement to stick with your program” with how frequently friends and family (separately) perform those behaviors. The sum for each scale is calculated separately. The subscale ranges were 10 to 50 for family support, 10 to 50 for friend support, and 2 to 10 for family punishment. Self-reported PA was assessed by an adapted Godin Leisure-Time Exercise Questionnaire, which assessed frequency and duration of moderate and vigorous leisure-time PA over the past week.10This was converted into total minutes of moderate-to-vigorous PA with extreme values excluded based on recommended cutoffs (n = 11).11 Language acculturation was assessed with the 4-item language-use subscale of the Short Acculturation Scale for Hispanics.12 This scales asks in what language individuals (1) generally read and speak, (2) usually speak at home, (3) usually think in, and (4) usually speak with their friends. Each individual is then categorized having low US acculturation, Biacculturation, or high US acculturation, though the latter 2 were combined in our stratified analyses due to small sample size. Anthropometric measures, including body mass index and waist circumference, were collected by staff. Demographic characteristics were collected using items from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, including sex, age, years of education, employment, and marital status.

Analyses

To address the primary research question, we conducted a 2-wave cross-lagged panel model to simultaneously examine whether social support at time 1 was predictive of PA at time 2 and whether PA at time 1 was predictive of social support at time 2. Given the positive skew and overdispersion of the variables, we used negative binomial regression. We conducted both an unadjusted model and then a model adjusted for covariates that were theoretically and/or previously empirically relevant, including sex,4 age,4 marital status,4 language acculturation,13 waist circumference (individuals with larger waist circumference may receive a differential levels of support), and time between assessments (due to large variability). The time 2 outcome variables were regressed on the covariates and covariates were allowed to correlate with each other in the model. We assessed relative model fit between the unadjusted and adjusted analysis using the Akaike information criterion (AIC) and the Bayesian information criterion (BIC), where smaller values indicate better fit.

Additionally, we ran exploratory analyses that tested models stratified by sex and language acculturation. The purpose of assessing stratified models was to examine potential differences between sex and language acculturation groups, respectively. The stratified models were also adjusted for the same abovementioned covariates. Cameron County Hispanic Cohort allowed for multiple individuals per household, which we controlled for in our analyses. We used maximum likelihood estimation with robust standard errors for all models. Analyses were performed with MPlus version 7.31.

Results

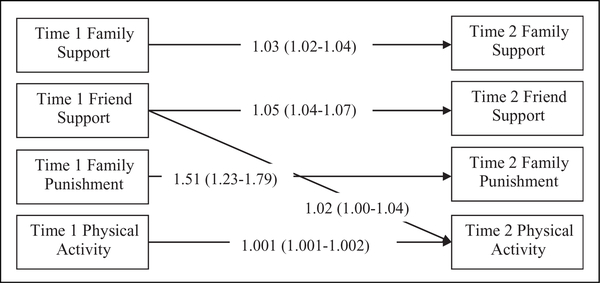

The sample (n = 588) was predominately female, married, and with low US acculturation (Table 1). On average, they were obese and had 11 years of education. From a potential range of 10 to 50, mean friend support was 15.1 and mean family support was 19.3. The AIC and BIC for the adjusted model (AIC: 12 024; BIC: 12 234) were smaller than those of the unadjusted model (AIC: 12 343; BIC: 12 448), indicating better fit, and the estimates were similar, therefore, we present only the adjusted model. Figure 1 shows the overall adjusted model for the relation between the social support variables and PA over time in the full sample (n = 588). All measures at time 1 were associated with their corresponding measure at time 2. There was a significant direct relation between friend support at time 1 and PA at time 2 (adjusted rate ratio [RR] = 1.02, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.00–1.04). This indicates that a 1-unit increase in friend support at time 1 is associated with a 2% increase in PA at time 2. For an individual who experiences a 10-unit increase in friend support (for example, goes from responding “rarely” to “a few times” on all 10 friend support items) and is currently achieving 100 minutes of activity, this would mean an additional 22 minutes in a week. There was no evidence of a relation between time 1 PA and time 2 social support variables. In models stratified by sex (not pictured), there was an additional significant inverse association between time 1 friend support and time 2 family punishment for males (Adjusted RR = 0.94, 95% CI: 0.87–0.99). In models stratified by acculturation (not pictured), models were similar to the overall model.

Table 1.

Time 1 Characteristics for Sample (N = 588).

| Variable (M, SD) | Baseline Value |

|---|---|

| Sex (Ref: Male) | |

| Female (n, %) | 402 (68.4) |

| Age | 48.8 (13.5) |

| Years education | 11.0 (5.3) |

| BMI | 31.3 (6.0) |

| Waist circumference, cm | 103.5 (14.0) |

| Employment status (Ref: Unemployed) | |

| Employed (n, %) | 304 (51.7) |

| Marital status (Ref: Unmarried) | |

| Married (n, %) | 401 (68.2) |

| Language acculturation (Ref: Low US acculturation) | |

| High US acculturation (n, %) | 122 (20.8) |

| Time between assessments, days | 286 (148.6) |

| Family support | 19.3 (9.8) |

| Friend support | 15.1 (7.4) |

| Family punishment | 2.2 (0.9) |

| Physical activity (MVPA minutes) | 106.0 (173.2) |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; M, mean; MVPA, moderate-to-vigorous physical activity; SD, standard deviation.

Figure 1.

Total sample (n = 588) adjusted risk ratios + 95% confidence interval for statistically significant relations between social support and physical activity, adjusted for sex, age, language acculturation, time between assessments, waist circumference, marital status, and multiple individuals per household. AIC = 12 024; BIC = 12 234. AIC indicates Akaike information criterion; BIC, Bayesian information criterion.

Discussion

Summary

In this study, we found that in the overall model assessing the longitudinal relation between family support, friend support, family punishment, and PA in a sample of predominately Mexican-American adults, only friend support was associated with future PA. This finding was also consistent across sex and acculturation levels and has been seen in previous cross-sectional studies in Hispanic adults.5,6 Our study extends previous research by testing the bidirectional relation and finding no evidence that PA is predictive of social support. Family social support was not associated with PA in the overall model, which adds to the existing mixed cross-sectional findings3,5,6 but contrasts to what Hispanics report in qualitative research.14,15 In our sample, there was higher mean family support than friend support, so it is possible that given a certain level of family support, the tipping point for PA is that friends also provide social support. However, mean social support from both friends and family was low, with on average most people indicating that support from either group occurred less than a few times in the last 3 months. Interestingly, friend support was inversely associated with family punishment in males, indicating that more friend support was associated with less criticism and complaining from their family members. This could indicate that Hispanic males receiving friend support for PA mitigates strain on the family and reduced family complaints related to PA. Additional longitudinal research is needed to provide clarity on what combination of support is ideal for encouraging PA.

Limitations

As the assessment of differences between men and women and those of different levels of acculturation were exploratory, we did not conduct formal test of interaction. Furthermore, there was reduced power due to smaller samples in the stratified analyses. For these reasons, we must exercise caution and limit the extension of these exploratory findings to a description of this current sample. We used a validated measure of social support for PA, however, the measure also contains a family punishment subscale which is both less theoretically robust and not well-validated. We also used self-reported PA, which has issues such as over-reporting. Although the average time between assessments was 286 days, there was substantial variability in time between assessments across participants, potentially influencing the results. However, we controlled for this in the analyses. Despite these limitations, we used a validated measure of both friend and family social support and a longitudinal model to assess the bidirectional relation between social support and PA, while controlling for confounding.

Significance

Generally, Hispanic adults are receiving low levels of social support from both friends and family. This study fulfilled a need for more longitudinal research on the association between social support and PA in Hispanic adults. We found friend social support was predictive of PA, though interestingly, family support was not significantly associated with PA. There is a need for further research to clarify the value of targeting friends instead of family as part of PA interventions for Hispanic adults, especially given the presumed value of familismo in Hispanic families.

So What?

This longitudinal study, using cross-lagged panel models to assess the relation between family support, friend support, family punishment, and physical activity (PA) in a sample of Hispanic adults, we found that only friend support was associated with PA. Results are contrary to what might be expected in Hispanic populations, given the general value of familismo. In general, social support for PA from both friends and family was low across the sample.

Acknowledgments

The authors of this manuscript would like to acknowledge the participants who so willingly participated in this study, our community partners, and Community Action Board members who are dedicated to eliminating health disparities. We would also like to acknowledge our Tu Salud ¡Si Cuenta! professional study team led by Lisa Mitchell-Bennett. We thank the cohort team, led by Drs Susan Fisher-Hoch and Joseph McCormick and Ms Rocio Uribe and her team, who recruited and documented the participants. We also thank Christina Villarreal for administrative support. Finally, we thank Valley Baptist Medical Center, Brownsville, Texas for providing us space for our Center for Clinical and Translational Science Clinical Research Unit.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was funded by the UTHealth School of Public Health Cancer Education and Career Development Program through a National Cancer Institute (NCI)/National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grant (R25CA57712), by the EXPORT Grant from the National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities (P20 MD000170), by the Clinical and Translational Science Awards (CTSA) from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (UL1 TR000371), by The University of Texas MD Anderson’s Cancer Center Support Grant from NIH/NCI (CA016672), by a research career development award (K12HD052023: Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women’s Health Program-BIRCWH; Berenson, PI) from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development at NIH, by the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas (RP170259) and by the Duncan Family Institute through the Center for Community-Engaged Translational Research.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Marquez DX, Neighbors CJ, Bustamante EE. Leisure time and occupational physical activity among racial or ethnic minorities. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2010;42(6):1086–1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bauman AE, Reis RS, Sallis JF, et al. Correlates of physical activity: why are some people physically active and others not? The Lancet. 2012;380(9838):258–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eyler AE, Wilcox S, Matson-Koffman D, et al. Correlates of physical activity among women from diverse racial/ethnic groups. J Womens Health Gend Based Med 2002;11(3):239–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scarapicchia TMF, Amireault S, Faulkner G, Sabiston CM. Socials upport and physical activity participation among healthy adults: a systematic review of prospective studies. Int Rev Sport Exer P. 2016;10(1):50–83. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hovell M, Sallis J, Hofstetter R, et al. Identification of correlates of physical activity among Latino adults. J Community Health 1991;16(1):23–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marquez DX, McAuley E. Social cognitive correlates of leisure time physical activity among Latinos. J Behav Med 2006;29(3): 281–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fisher-Hoch SP, Rentfro AR, Salinas JJ, et al. Socioeconomic status and prevalence of obesity and diabetes in a Mexican American community, Cameron county, Texas, 2004–2007. Prev Chronic Dis. 2010;7(3):A53. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fisher-Hoch SP, Vatcheva KP, Laing ST, et al. Peer reviewed: missed opportunities for diagnosis and treatment of diabetes, hypertension, and hypercholesterolemia in a Mexican American population, Cameron county Hispanic cohort, 2003–2008. Prev Chronic Dis. 2012;9:E135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sallis JF, Grossman RM, Pinski RB, Patterson TL, Nader PR. The development of scales to measure social support for diet and exercise behaviors. Prev Med 1987;16(6):825–836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Godin G, Shephard R. A simple method to assess exercise behavior in the community. Can J Appl Sport Sci 1985;10(3):141–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.IPAQ Research Committee. Guidelines for data processing and analysis of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ)-short and long forms. 2005. https://sites.google.com/site/theipaq/scoring-protocol Accessed June 27, 2018.

- 12.Marin G, Sabogal F, Marin BV, Otero-Sabogal R, Perez-Stable EJ. Development of a short acculturation scale for Hispanics. Hispanic J Behav Sci. 1987;9(2):183–205. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berrigan D, Dodd K, Troiano RP, Reeve BB, Ballard-Barbash R. Physical activity and acculturation among adult Hispanics in the United States. Res Q Exerc Sport. 2006;77(2):147–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eyler AA, Baker E, Cromer L, King AC, Brownson RC, Donatelle RJ. Physical activity and minority women: a qualitative study. Health Educ Behav. 1998;25(5):640–652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thornton PL, Kieffer EC, Salabarría-Peña Y, et al. Weight, diet, and physical activity-related beliefs and practices among pregnant and postpartum Latino women: the role of social support. Matern Child Healt J. 2006;10(1):95–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]