Abstract

Partnership and engagement are mediators of change in the efficient uptake of evidence-based patient-centered health interventions. We reflect on our process of engagement and preparation of peer mentors in the development of peer-led psychotherapy intervention for HIV infected adolescents in active care at the Comprehensive Care Centre (CCC) at Kenyatta National Hospital. The program was implemented in two phases, using a Consultation, Involve, Collaboration and Empowerment approach as stepping stones to guide our partnership and engagement process with stakeholders and ten peer mentors embedded in the CCC. Our partnership process promoted equity, power-and-resource sharing including making the peer mentors in-charge of the process and being led by them in manual development. This process of partnership and engagement demonstrated that engaging key stakeholders in projects lead to successful development, implementation, dissemination and sustainment of evidence-based interventions. Feedback and insights bridged the academic and clinical worlds of our research by helping us understand clinical, family, and real-life experiences of persons living with HIV that are often not visible in a research process.. Our findings can be used to understand and design mentorship programs targeting lay health workers and peer mentors at community health care levels.

Keywords: Engagement, partnership, peer mentors, collaboration, equity, empowerment

Introduction

Research shows that solidarity and constructive conversation on public issues yield positive outcome on development. For instance, Proctor et al. (2009) indicate that two-way communication, collaboration and stakeholders’ consensus are critical for development and sustainment of evidence-based interventions. Some models used by researchers have not successfully addressed the variety of health disparities embedded in their populations and therefore lead researchers tend to focus only to the mobilization of “community-based participatory research” (CBPR) approach. CBPR is a collaborative research approach that involves all partners and recognizes their strengths (Cukor et al., 2016). The relationship between researchers and stakeholders is important to generate evidenced-based intervention where appropriate information and empowerment are both given priority. A collaborative partnership between various stakeholders helps to translate research evidence into patient-centered practice and policy-making (Concannon et al., 2014; Sheridan, Schrandt, Forsythe, Hilliard, & Paez, 2017).

Peer support/mentoring as an engagement process

It has been observed that the inclusion of members from the target population aids in addressing the variety of health disparities and recognize the stakeholders’ unique strengths (Israel, Schulz, Parker, & Becker, 2001). Current studies have seen the inclusion of patients in designing research questions and methodology that reflect, a process of opinion building on their salience as stakeholders in research (Concannon et al., 2014). In addition, research affirms that peer mentoring interventions for mental health care and management help individuals manage their chronic conditions by sharing their difficulties with trained peers from their similar circumstances (Knox et al., 2015).

Peer support is considered a unique type of social support provided by those who share characteristics with the person being supported and is intentionally fostered within formal interventions (Davidson et al., 1999; Israel et al., 2001; Embuldeniya et al., 2013). It has been found that having access to a trusted confidant who in addition to care, provides respect and guidance, goes a long way towards creating emotional security and improving selfesteem and confidence.

Furthermore, mentoring relationships with non-parental adults or peers, have been shown to have positive effects on adolescent outcomes (Erickson, McDonald, & Elder, 2009; Haddad, Chen, & Greenberger, 2011). Studies with PLWHIV have shown that peer intervention methods improve well-being (Broadhead et al., 2002; Deering et al., 2009) as well as being developmentally sensitive for adolescents (Cai et al., 2008; Mahat, Scoloveno, De Leon, & Frenkel, 2008). Researchers have argued that a peer mentoring embraces many potentials such as development of new peer’ identities, informed choices on education, personal development, self-confidence and self-esteem (Mezey et al., 2015).

Program design

This study was approved by the Kenyatta National Hospital/University of Nairobi Institutional Review Board (KNH-UON ERC ref no. P772/10/2016). Informed consent was provided by all participants involved. The engagement and partnership process was implemented in two phases. Phase 1 was to develop and adapt the manual to suit the proposed audience and setting. This process began with a 4-week manual development process by the co-investigators. Stakeholder meetings with selected persons from the target audience of young adults living with HIV (YLHIV), HIV clinicians, government, non-governmental and community agencies working with YLHIV were held to assess the manual content and adapt it for the proposed age groups of: 10–24 years within the Kenyan setting. After the stakeholder meetings, some work was done with selected peer mentors working within the health facility (CCC) to practice the manual content (i.e., activities) in the proposed context to ascertain their “workability” in real-life settings. These practice sessions allowed us to see links in the manual and led us to a one-day manual editing and revision session which included the participation of peer mentors from the CCC.

In the second phase equipped with a final draft of the manual; the peer mentors were engaged, in a ten-weeks long role-play sessions in their various groups. This engagement was prompted through realization that the peer mentors needed additional training in certain psychotherapy and counseling skills that would help in the overall delivery of the support groups. The engagement sessions were targeted to bridge that gap. The peer mentors were both young adults and older individuals between late 30s and 40s who entered the facility as adolescents seeking care but had gathered a huge experience in working with adolescents.

Method

Research context

Our work took place at the outpatient Comprehensive Care Centre (CCC) in Kenyatta National Hospital (KNH), Kenya’s largest national referral and teaching hospital in East and Central Africa. Records from the CCC database indicate that there are currently 9530 patients enrolled in care, with about 10% representing adolescents aged between 10–24 years. The psychosocial program at the CCC uses multimodal therapies such as one-on-one counseling, to group sessions offered for various groups of people receiving care. The counselors and peer mentors led group session with various age groups on a weekly basis.

Process approach towards engagement - consult, involve, collaborate and empower

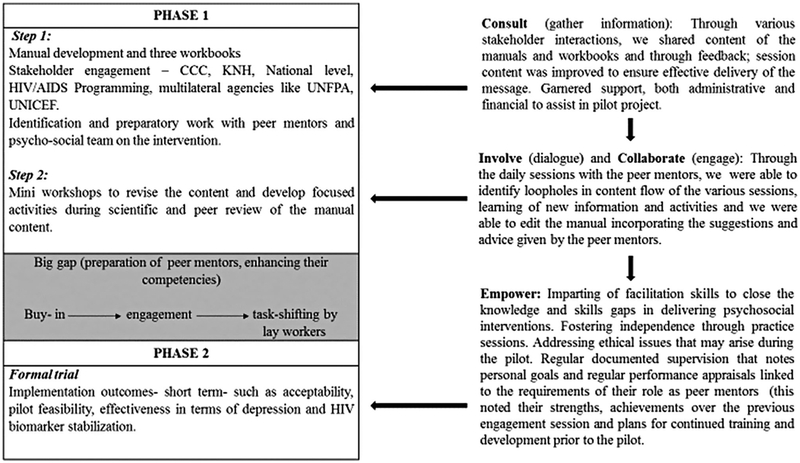

The overall engagement comprises involvement Consultation, Involve, Collaboration and Empowerment approach (CICE) as stepping stones. It can be conceptualized as seen in Figure 1, where each step was mapped by a project activity and used as a competency to master in the research team.

Figure 1.

Process approach towards engagement.

Consultation.

The co-investigators with different levels of experience and exposure to the HIV scene came together to develop the content of the “Positive living support group manual”. Through a series of individual work and group meetings, the content was created and adapted to suit the various age groups being catered for. It was important for us to bring together and consult with the appropriate stakeholders on the content we had come up with. One of our goals as we were developing this support group manual was to ensure acceptability and sustainability of the program among our target population and programs catering to the health needs of YLHIV. Our stakeholder meetings ensured that we tailored the content to ensure that the activities had impact and benefit for the adolescent community. These meetings also helped us in garnering the support of both administrative and financial nature, as well as integrating feedback from key partners in this process.

Involve (dialogue) and Collaborate (engage).

We came together with the peer mentors with the awareness that we needed not only for them to carry out the activities during the trial, but we needed their input as well as their experience with having worked with support groups within the CCC context. It was important to us that even as we assessed the workability of the different activities with the adolescent patients, that they feel included in the process and that their views were important and valued in this process. This involved weekly lunchtime sessions to discuss their views on the activities and seeking their feedback on how the activities could be improved. This collaboration between the peer mentors and coinvestigators improved the buy-in of many of the peer mentors as they felt included in the process as opposed to being used for the overall gain of the research.

Empower.

With our frequent interactions with the peer mentors, it was noted that there were skills that they needed to make them more competent facilitators during the final testing of the manual. We came up with 10-weeks engagement program to help equip them with the necessary facilitation skills such as how to create rapport in a group setting, how to communicate, how to give and receive feedback. It was also important for them to learn how to observe and assess if a group member is distressed and how to deal with that within a group setting. Managing the time for each activity, how to lead and engage them in discussions as well as how to work with a co-facilitator. During this process, we were able to work with the peer mentors to the point where they felt they had the skills needed and felt confident to carry out the sessions independently.

Partnership, stakeholder engagement, and collaboration

Partnership, stakeholder Engagement, and Collaboration (PEC) have been identified as critical strategies in mental health research and involves related strategies such as coalition building, creating a learning collaborative, developing academic partnerships, involving patient/consumers and family members, organizing clinician implementation meetings, promoting network weaving (Huang et al., 2018). On the implementation and delivery level Huang et al. (2018), suggest that for an effective team process, PEC needs to consider two domains of behaviors that function to regulate a team’s performance and management of team maintenance (keeping the team together) and tailor their strategies to meet this. Strategies like creating of action plans, coordination and co-operation between team members, monitoring and reflection of an activity, problem-solving as well as offering team members psychological support and integrative conflict management. They also suggest conceptualizing it in a multilevel context (considering individual, organizational system and environmental influences) taking into consideration inter-related team processes including cognitive team processes (such as collective team climate and safety climate, team mental models, and team learning elements), team interpersonal, motivation, and affective processes (including team cohesion, team efficacy, team affect/emotion/conflict), and team action and behavioral processes (such as team coordination/cooperation/communication, team competencies/functions, team regulation, performance dynamics, and adaptation) (Rousseau, Aube, & Savoie, 2006; Kozlowski & Ilgen, 2006; Kozlowski, 2017).

Engagement and participation of peer mentors

Nine peer mentors working within the CCC were invited to be part of the intervention program and assigned to one of the three groups. They were chosen as they had previously been identified as “health champions” due to their low viral load and good adherence to medication. Their willingness to volunteer time and effort needed to provide support to others in need, as well as successful personal adjustment to the challenges of living with an HIV and having adequate insight into personal strengths, limitations; their ability to listen and empathize were also some of the reasons they were chosen to participate in the program.

We also included two nurses, two clinical officers and one pharmacist into the team to provide their technical expertise as well as their overall experience in working with YLHIV. The peer mentors were invited to lead the three intervention groups based on their specialization, familiarity and ease in working with young participants: Tumaini (10–14years), Amani (15–19years) and Hodari (20–24years). In each of these groups, there are unique challenges such as disclosure, transition, sexual and reproductive health knowledge that will be addressed in an age-appropriate manner during the intervention.

These engagement sessions focused on enhancing their communication, listening, and attending skills and increasing their knowledge of mental health-related aspects that cross-cut HIV/AIDS diagnoses. We had a special focus on competencies such as self-esteem issues, dealing with self-stigma and discrimination, eating healthy and living positively, building a network of good social support and building self-esteem and confidence. The goal was to build their competencies to address these challenges confidently and effectively during the intervention sessions. We also built on their communication skills within a group setting as the intervention would take place as a face-to-face support group work. We also took the PEC approach into consideration when engaging with the peer mentors. While our main focus was to empower them to build their skills and competencies for optimum delivery of the manual, we recognized the importance of regulating the team’s performance and team cohesion. Encouraging them to coordinate the meetings as well as cooperate not only within their specific groups but as a unit allowed for the fostering of an effective collective team climate that worked within their strengths and organizational challenges.

Discussion

Stakeholder involvement and engagement

For the successful development, implementation, dissemination and sustainment of evidence-based interventions, it is important to engage all key stakeholders (Leeman et al., 2015; Powell et al., 2015). Researcher-driven models have been found to not always address the variety of health disparities that affect the target populations, with communities themselves becoming weary of being passive participants and are asserting their voices in setting the research agenda (Israel, Schulz, Parker, & Becker, 1998; Proctor et al., 2009). Given the importance of adolescent health for future adult health, adolescents offer a unique window of opportunity to intervene and positively impact on individuals’ health trajectories into adulthood, we felt that the inclusion of all these groups in our meetings was not only vital to the process but also bolstered the purpose of the intervention (Viner et al., 2015).

During the development of the manual content, we saw the need to engage stakeholders with expertise in HIV and adolescents. These stakeholders included: members of the target population, pediatric and mental health consultants from the Kenyatta National Hospital, related government and non-governmental organizations (Ministry of Health, National AIDS and STIs Control Programme, United Nations Populations Fund). According to Deverka et al. (2012), stakeholders bring different experiences, interests and expertise to research studies which shape both the roles they play and the contributions they make to the process. The purpose of these internal and external stakeholder meetings was to consult with them on the content we created to ensure we will have the highest potential impact and benefit for the adolescent community.

Feedback and insights from the stakeholder engagement bridged the academic and clinical worlds of our research by helping us understand clinical, family, and real-life experiences that are often not seen. Stakeholders also contributed to knowledge about how our intervention can be used by clinics and patients’ families. This inclusion valued their knowledge, insights and the experiences of those who are either involved in or potentially affected by, the implementation of interventions like ours.

Peer mentor engagement: challenges of task- sharing and task-shifting

Our work was premised on the belief that peers may have the potential to influence the health outcomes of other patients by addressing feelings of isolation, promoting a positive outlook, and encouraging healthy behavior. While their experiential knowledge is an advantage, it was important for us to create a “common base” from which they could facilitate the process. To prepare peer mentors to address the specific needs of young people with HIV, the training emphasized short-term and long-term HIV-related challenges and available community resources. In addition, communication and attending skills were emphasized as potential tools to help the adolescents obtain desired information from professionals and needed community supports. Research has found that equipping peer mentors with the needed information and skills, helps increase participants’ knowledge about the issue, providing a mechanism for enhanced coping (Hibbard et al., 2002). The proper amount of preparation and quality of training for the peer mentor applicants prior to an intervention differentiates peer mentoring from spontaneous peer leadership or unorganized peer support (Dorgo, King, Bader, & Limon, 2013).

This preparation was not without its own challenges. The challenges that are worth enlisting here for further discussion include:

A peer in the typical HIV programming context is someone who has a great amount of knowledge and empathy about barriers and constraints of those living with HIV. However, working with them practicing the manual made them feel bored, disengaged and at times leading to a feeling that practice sessions were over-indulgent in preparation of the materials. The systematic approach towards learning the materials was not always readily accepted (collaboration we learnt meant different things for different people in multi-stakeholder teams and to reach a consensus and have a consistent approach takes time).

Task-shifting in a context that is hierarchical and not always equitable in distributing resources, is a problematic area that has not been attended to adequately in mental health or HIV intervention research in LMIC (involvement or engagement mean immersion in their problems and addressing their constraints experienced by lay-or-para-professionals).

Using this workforce to gain access to relevant communities without empowering them with the tool and systematic health promotion approaches is the utilitarian stance of researchers that only serves their own interests (and we had to constantly reflect on and strive towards true partnerships).

Our peer mentors came from different backgrounds, with differing levels of education (with the lowest having only secondary education and the highest having a master’s degree and in between, we had diploma holders, and some with secretarial or hospitality experience). Except for being HIV positive and volunteering within the CCC, they had no systematic knowledge or any formalized training to carry out support groups and this made it difficult in finding a common ground from which to train from.

Practical constraints such as competing work schedules, organizing time to practice group activities were challenging. Some of the peer mentors experienced a “major problem” with managing their time, which impacted on their ability to attend the engagement sessions consistently. We found that this irregular attendance impacted their ability to grasp the much-needed skills to perform their role effectively.

For a valuable engagement, we found that we had to, from time to time explain implementation and intervention research to them so they could understand the research process and how it is connected to changes in clinical practice and they are therefore equipped to make meaningful contributions. This was a new experience for them and for the research team.

Foundations of trust and mutual respect between researchers and the peer mentors was a key element to being able to successfully navigate all the foreseeable and unforeseeable challenges that present themselves over the course of collaboration and threaten the productivity of the collaboration.

Conclusion

We have developed an intervention for YLWHIV to be delivered by peer mentors at the CCC of the KNH. Our engagement and partnership process of Consultation with persons of different levels of experience and fields of exposure ensure that the intervention developed are tailored made for the needs of the target population. Involve (dialogue) and Collaborate (engage) - through dialogue and engagement of lay health workers serves to improve their buy-in as well as making them feel included in the process. Empower - our process showed us that for task-shifting to happen successfully, lay workers need to be empowered with the necessary skills they need to feel confident in their work. Task sharing and collaborative care in health facilities are innovative ideas, but the process is unusually long and difficult requiring the researchers, lay health workers, clinicians and relevant stakeholders to listen and understand each other’s concerns.

Acknowledgements

The authors’ engagement sessions were supported by UNFPA through I Choose Life, Kenya. The authors would like to thank Lilian Langat, Kigen Korir from UNFPA for their support.

Funding

This work was supported by Kenyatta National Hospital research fund (ref no. KNH/R&P/23F/75/9).

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Broadhead RS, Heckathorn DD, Altice FL, van Hulst Y, Carbone M, Friedland GH,… Selwyn PA (2002). Increasing drug users’ adherence to HIV treatment: Results of a peer-driven intervention feasibility study. Social Science & Medicine, 55(2), 235–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Y, Hong H, Shi R, Ye X, Xu G, Li S, & Shen L (2008). Long-term follow-up study on peer-led school-based HIV/AIDS prevention among youths in Shanghai. International Journal of STD/AIDS, 19(12), 848–850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Concannon TW, Fuster M, Saunders T, Patel K, Wong JB, Leslie LK, & Lau J (2014). A systematic review of stakeholder engagement in comparative effectiveness and patient-centered outcomes research. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 29(12), 1692–1701. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-2878-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cukor D, Cohen LM, Cope EL, Ghahramani N, Hedayati SS, Hynes DM,… Mehrotra R (2016). Patient and other stakeholder engagement in patient-centered outcomes research institute funded studies of patients with kidney diseases. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology: CJASN, 11(9), 1703–1712. doi: 10.2215/CJN.09780915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson L, Chinman M, Kloos B, Weingarten R, Stayner D, & Tebes JK (1999). Peer support among individuals with severe mental illness: A review of the evidence. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 6(2), 165187. [Google Scholar]

- Deering KN, Shannon K, Sinclair H, Parsad D, Gilbert E, & Tyndall MW (2009). Piloting a peer-driven intervention model to increase access and adherence to antiretroviral therapy and hiv care among street-entrenched hiv-positive women in Vancouver. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 23(8), 603–609. doi: 10.1089/apc.2009.0022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deverka PA, Lavallee DC, Desai PJ, Esmail LC, Ramsey SD, Veenstra DL, & Tunis SR (2012). Stakeholder participation in comparative effectiveness research: Defining a framework for effective engagement. Journal of Comparative Effectiveness Research, 1(2), 181194. doi: 10.2217/cer.12.7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorgo S, King GA, Bader JO, & Limon JS (2013). Outcomes of a peer mentor implemented fitness program in older adults: A quasi-randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 50(9), 11561165. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.12.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Embuldeniya G, Veinot P, Bell E, Bell M, Nyhof-Young J, Sale JE, & Britten N (2013). The experience and impact of chronic disease peer support interventions: A qualitative synthesis. Patient Education and Counseling, 92(1), 3–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson LD, McDonald S, & Elder GH (2009). Informal mentors and education: Complementary or compensatory resources? Sociology of Education, 82(4), 344–367. doi: 10.1177/003804070908200403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haddad E, Chen C, & Greenberger E (2011). The role of important non-parental adults (VIPs) in the lives of older adolescents: A comparison of three ethnic groups. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 40(3), 310–319. doi: 10.1007/s10964-010-9543-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibbard MR, Cantor J, Charatz H, Rosenthal R, Ashman T, Gundersen N, et al. (2002). Peer support in the community: Initial findings of a mentoring program for individuals with traumatic brain injury and their families. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 17(2), 112–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang K, Kwon SC, Cheng S, Kambuokos D, Shelley D, Brotman LM … Hoagwood K (2018). Unpacking partnership, engagement, and collaboration research to inform implementation strategies development: Theoretical frameworks and emerging methodologies. Frontiers in public health, 6(190), 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, & Becker AB (1998). Review of community-based research: Assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annual Review of Public Health, 19, 173–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, & Becker AB (2001).Community-based participatory research: Policy recommendations for promoting a partnership approach in health research. Community-Campus Partnerships for Health. Educ Health (Abingdon), 14(2), 182–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knox L, Huff J, Graham D, Henry M, Bracho A, Henderson C, & Emsermann C (2015). What peer mentoring adds to already good patient care: Implementing the Carpeta Roja peer mentoring program in a well-resourced health care system. Annals of Family Medicine, 13(Suppl 1), S59–S65. doi: 10.1370/afm.1804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozlowski SWJ (2017). Enhancing the effectiveness of work groups and teams: A reflection. Perspectives. on Psychological Science, doi: 10.1177/1745691617697078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozlowski SWJ, & Ilgen DR (2006). Enhancing the effectiveness of work groups and teams. Psychological Science in the Public interest, 7, 77–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leeman J, Calancie L, Hartman MA, Escoffery CT, Herrmann AK, Tague LE, . Samuel-Hodge C (2015). What strategies are used to build practitioners’ capacity to implement community-based interventions and are they effective? A systematic review. Implementation Science: IS, 10(80), doi: 10.1186/s13012-015-0272-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahat G, Scoloveno MA, De Leon T, & Frenkel J (2008). Preliminary evidence of an adolescent HIV/AIDS peer education program. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 23(5), 358–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mezey G, Meyer D, Robinson F, Bonell C, Campbell R, Gillard S, … White S (2015). Developing and piloting a peer mentoring intervention to reduce teenage pregnancy in looked-after children and care leavers: An exploratory randomised controlled trial. Health Technology Assessment (Winchester, England), 19(85), 1–vi. doi: 10.3310/hta19850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell BJ, Waltz TJ, Chinman MJ, Damschroder LJ, Smith JL, Matthieu MM, … Kirchner JE (2015). A refined compilation of implementation strategies: Results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing change (ERIC) project. Implementation Science: IS, 10, 21. doi: 10.1186/s13012-015-0209-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proctor EK, Landsverk J, Aarons G, Chambers D, Glisson C, & Mittman B (2009). Implementation research in mental health services: An emerging science with conceptual, methodological, and training challenges. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 36(1). doi: 10.1007/s10488-008-0197-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rousseau V, Aube C, & Savoie A (2006). Teamwork behaviors a review and an integration of frameworks. Small Group Research, 37, 540–570. [Google Scholar]

- Sheridan S, Schrandt S, Forsythe L, Advisory Panel on Patient Engagement (2013 inaugural panel), Hilliard TS, & Paez KA (2017). The PCORI engagement Rubric: Promising practices for partnering in research. Annals of Family Medicine, 15(2), 165–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viner RM, Ross D, Hardy R, Kuh D, Power C, Johnson A,… Batty GD (2015). Life course epidemiology: Recognizing the importance of adolescence. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 69(8), 719–720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]