Abstract

Honeybees Apis mellifera are important pollinators of wild plants and commercial crops. For more than a decade, high percentages of honeybee colony losses have been reported worldwide. Nutritional stress due to habitat depletion, infection by different pests and pathogens and pesticide exposure has been proposed as the major causes. In this study we analyzed how nutritional stress affects colony strength and health. Two groups of colonies were set in a Eucalyptus grandis plantation at the beginning of the flowering period (autumn), replicating a natural scenario with a nutritionally poor food source. While both groups of colonies had access to the pollen available in this plantation, one was supplemented with a polyfloral pollen patty during the entire flowering period. In the short-term, colonies under nutritional stress (which consumed mainly E. grandis pollen) showed higher infection level with Nosema spp. and lower brood and adult bee population, compared to supplemented colonies. On the other hand, these supplemented colonies showed higher infection level with RNA viruses although infection levels were low compared to countries were viral infections have negative impacts. Nutritional stress also had long-term colony effects, because bee population did not recover in spring, as in supplemented colonies did. In conclusion, nutritional stress and Nosema spp. infection had a severe impact on colony strength with consequences in both short and long-term.

Subject terms: Microbial ecology, Pathogens

Introduction

Insects play a significant role in the functioning of ecosystem processes, and pollination is one of their main ecological functions1,2. During recent years, pollinator decline has been reported worldwide3,4. In particular, honeybees (Apis mellifera) are among the most important insect pollinator in temperate and tropical areas, promoting the sexual reproduction of wild plants and commercial crops5,6. Although the number of managed colonies varies in association with different socioeconomic aspects7–10, high honeybee colony losses are occurring globally9,11. Colony losses are likely the result of the effect of multiple stressors12,13. However, it has been proposed that the combination of nutritional stress, infections by pathogens and pesticide exposure are among the most important driving forces3,10,14,15. Nutritional stress is associated with land use intensification and the expansion of monoculture agricultural areas, which deprives bees of the necessary polyfloral pollen needed to fulfill their nutritional requirements14,16. Pollen nutrition affects bee lifespan17, their immunocompetence18, their resistance to pathogen infection19–22 and behavioral transition23,24. Among the pathogens affecting honeybee health, Varroa destructor, RNA viruses15,25,26 and the microsporidia Nosema ceranae27,28, have the most important impact on colony losses27,29–31. It has been shown that colonies subjected to poor nutrition suffer from increased rates of Nosema spp. infection32,33. Those results contrasts with laboratory studies, where bees fed with pollen have higher infection levels of Nosema spp. although survive longer than bees fed with syrup and no protein20,21,34. It suggests that under laboratory conditions increased nutritional resources promote Nosema spp. replication, but the beneficial effects of nutrition on honeybee physiology surpass the adverse effects of the infection. These contrasting results highlight the complex relationship between the parasite and the host and the effects of the social environment of the colony.

Eucalyptus spp. plantations provide an ideal natural model to study the impact of nutritional stress on honeybee health since its pollen has a low crude protein percentage33,35, low lipid content36 and is deficient in isoleucine35,37.

We hypothesize that nutritional stress affects the health status of colonies, having consequences on colony depopulation and colony losses. In this study, we analyzed the effect of nutritional stress on colony strength and the infection level of Nosema spp., V. destructor, RNA viruses and Lotmaria passim during the nutritional stress period and in a long-term perspective.

Results

Experimental set-up

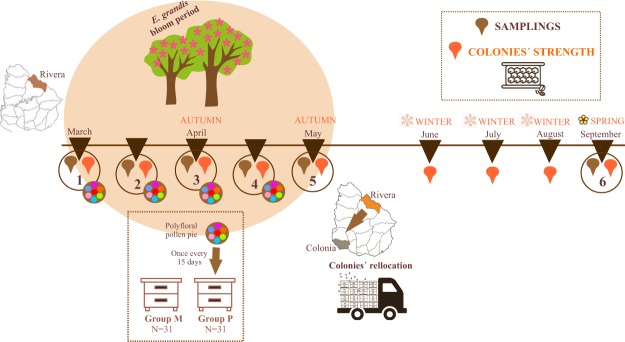

To test the effects of nutritional stress on the health status of honeybees, 62 colonies were placed in a E. grandis plantation at the beginning of the flowering season (Fig. 1). The available pollen in the foraging area was predominantly E. grandis, as confirmed by the analysis of pollen collected at the hive entrance (more than 85% of pollen corresponded to these trees in all the sampling times, Supplemental Table S1). Crude protein content varied during the flowering period (26.10% in sampling 2, 17.01% in sampling 3 and 18.95% in sampling 4) and the average lipid content was 0.96%. As colonies from group M (monofloral) consumed only the pollen available in the surrounding plantation’s foraging area, they are expected to be under nutritional stress. On the other hand, colonies from group P (polyfloral) were supplemented with a polyfloral pollen patty composed of pollen from 23 different species (Supplementary Table S1), with a crude protein content of 26.31% and 3.72% of lipids. The polyfloral pollen patty showed a higher proportion of amino acids than pollen available in the environment (Supplementary Table S2).

Figure 1.

Experimental design.

Six pesticides were detected in the polyfloral pollen patty: azoxystrobin, atrazine, carbendazym, coumaphos, pyraclostrobin and tebuconazole. However, the concentration was closed to the detection limit of the analytic technique in all cases, and more than 208,000 times lower than LD50 according to the Pesticides Properties DataBase, of the University of Hertfordshire (available at https://sitem.herts.ac.uk/aeru/footprint/es/, Supplementary Table S3). On the other hand, N. apis, N. ceranae, ABPV, BQCV, DWV and SBV were not detected in the pollen patty.

Colony pollen diversity

At the beginning of the experiment, colonies from groups P and M were collecting pollen with similar diversity (Fig. 2, Table 1). This diversity decreased significantly within 15 days in both groups (Table 1). Afterwards, colonies from group M showed higher diversity of the collected pollen than group P during the remaining flowering period, being statistically significant in sampling times 3 and 4 (Fig. 2, Table 1). The major contributor of increased forage diversity observed in group M was from two Baccharis spp.

Figure 2.

Colony pollen diversity during the nutritional stress period represented as the Shannon diversity index. Colonies from group M (monofloral) are represented in blue and colonies from group P (polyfloral) are represented in orange. Boxes show 1st and 3rd interquartile range and the median is represented by a line. Whiskers include the values of 90% of the samples. Significant differences of pairwise comparisons at each sampling time are represented as ** when p ≤ 0.01, and *** when p ≤ 0.001.

Table 1.

Statistical results of colony strength and infection level of different pathogens from groups M (monofloral) and P (polyfloral) at specific samplings (S). MW: Mann Whitney U Test. Significant results (p ≤ 0.05) are shown in black.

| Comparison | Pollen diversity Shannon diversity index | Brood population | Adult population | ABPV | BQCV | DWV | SBV | V. destructor | Nosema spp. (proportion of infected bees) | Nosema spp. (number of spores in a pool of bees) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1. M vs. P | MW p = 0.24 | MW p = 0.57 | MW p = 0.71 | MW p = 0.22 | MW p = 0.32 | MW p = 0.23 | MW p = 0.62 | MW p = 0.31 | T test p = 0.32 | T test p = 0.94 |

| S2. M vs. P | MW p = 0.12 | MW p = 0.05 | MW p = 0.02 | MW p ≤ 0.001 | MW p = 0.93 | MW p = 0.81 | MW p = 0.002 | MW p = 0.5 | T test p = 0.35 | T test p = 0.02 |

| S3. M vs. P | MW p ≤ 0.001 | MW p = 0.003 | MW p = 0.34 | MW p ≤ 0.001 | MW p ≤ 0.001 | MW p ≤ 0.001 | MW p = 0.79 | MW p = 0.52 | T test p = 0.12 | T test p = 0.14 |

| S4. M vs. P | MW p = 0.002 | MW p = 0.02 | MW p = 004 | MW p ≤ 0.001 | MW p = 0.01 | MW p ≤ 0.001 | MW p = 0.06 | MW p = 0.43 | T test p = 0.004 | T test p = 0.83 |

| S5. M vs. P | MW p = 0.06 | MW p = 0.28 | MW p = 0.02 | MW p ≤ 0.001 | MW p = 0.1 | MW p ≤ 0.001 | MW p = 0.01 | MW p = 0.6 | T test p ≤ 0.001 | T test p ≤ 0.001 |

| June: M vs. P | — | MW p = 0.02 | MW p = 0.01 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| July: M vs. P | — | MW p = 0.007 | MW p = 0.001 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| August: M vs. P | — | MW p = 0.004 | MW p = 0.02 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| S6: M vs. P | — | MW p = 0.28 | MW p = 0.02 | MW p = 0.90 | MW p = 0.41 | MW p = 0.80 | MW p = 0.26 | — | T test p = 0.91 | — |

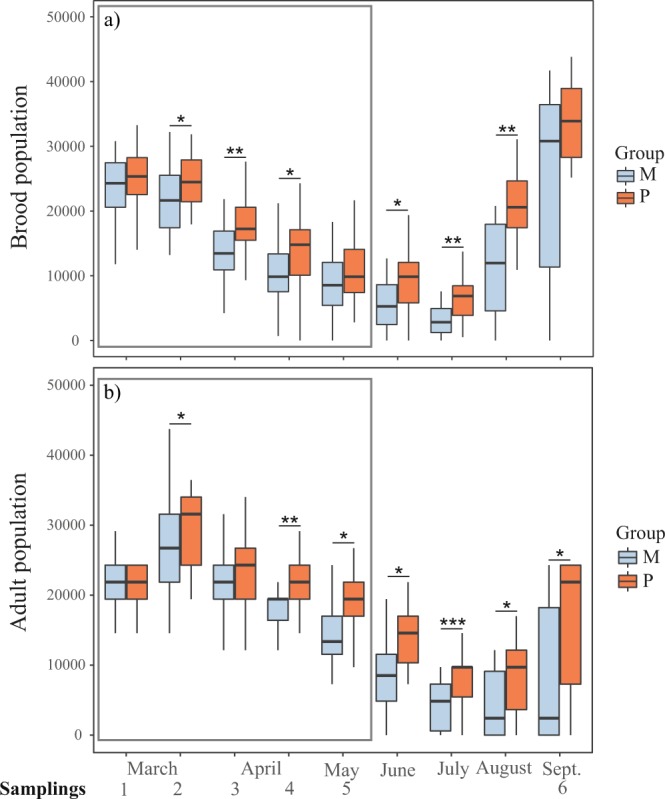

Colony strength

Generalized linear mixed models (GLMM) were used to assess the relationship between time/treatment and colony strength/pathogen infection. Brood population was affected negatively by time, since it decreased from autumn to winter, as expected (Table 2). Treatment (pollen supplementation) affected positively brood population only in a time-manner dependence (brood = time*treatment + (1|colony) (Table 2). Pollen supplementation in autumn exerted long-term consequences since colonies from group P showed higher brood population than colonies from group M in winter (Fig. 3, Table 1). In the following spring, both groups of colonies showed similar brood populations (Fig. 3, Table 1).

Table 2.

Statistical results of Generalized Lineal Mix Models.

| Dependent variable | Independent variable | Coefficient value | Intercept value | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brood population | Treatment P | 0.041 | 10.06 | 0.62 |

| Time | −0.018 | ≤0.001 | ||

| Time*TreatmentP | 0.005 | ≤0.001 | ||

| Adult population | Treatment P | 0.044 | 10.17 | 0.38 |

| Time | −0.01 | ≤0.001 | ||

| Time*TreatmentP | 0.002 | ≤0.001 | ||

| Nosema spp. | Treatment P | 0.025 | −0.26 | 0.28 |

| Time | 0.006 | ≤0.001 | ||

| Time*TreatmentP | −0.001 | 0.02 | ||

| ABPV | Treatment P | 0.729 | 0.03 | ≤0.001 |

| Time | −0.002 | ≤0.001 | ||

| Time*TreatmentP | −0.0004 | 0.46 | ||

| BQCV | Treatment P | −0.27 | 0.95 | 0.13 |

| Time | 0,00 | 0.04 | ||

| Time*TreatmentP | 0.002 | 0.34 | ||

| DWV | Treatment P | 0.53 | 0.52 | ≤0.001 |

| Time | −0.004 | ≤0.001 | ||

| Time*TreatmentP | 0.0004 | 0.81 | ||

| SBV | Treatment P | 0.64 | 0.61 | 0.03 |

| Time | −0.0008 | 0.83 | ||

| Time*TreatmentP | 0.002 | 0.69 | ||

| Adult population | Nosema spp | −0.26 | 10.09 | ≤0.001 |

| Treatment P | 0.035 | 0.66 | ||

| Nosema*TreatmentP | 0.096 | ≤0.001 |

Figure 3.

Brood (a) and adult (b) population during the nutritional stress period (squared in grey) and during the winter and spring. Colonies from group M (monofloral) are represented in blue and colonies from group P (polyfloral) are represented in orange. Boxes show 1st and 3rd interquartile range and median represented by a line. Whiskers include the values of 90% of the samples. Significant differences of pairwise comparisons at each sampling time are represented as * when p ≤ 0.05, ** when p ≤ 0.01, and *** when p ≤ 0.001.

Sampling time and treatment also affected adult population in a similar trend as for brood population (adult = time*treatment + (1|colony). Time affected negatively the adult population (population decreased from autumn to winter), while pollen supplementation affected it positively in a time-manner dependence (Table 2).

On the other hand, there were no differences in colony mortality between both groups of colonies during the nutritional stress period (χ2 Test, p = 0.66). In the long-term, even though proportion of dead colonies was higher in colonies from group M (40%) compared to colonies from group P (18.5%), this difference was not statistically significant (χ2 Test, p = 0.12).

Nosema spp. infection level

During the E. grandis flowering period, pollen supplementation negatively affected the infection level of Nosema spp., since supplemented colonies showed lower infection level than non-supplemented colonies. This effect depends on time, since the difference in the infection level of this pathogen between both groups of colonies increased gradually throughout the sampling times (Nosema = time*treatment + (time|colony). On the other hand, Nosema spp. infection, increased over time (Table 2; Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Nosema spp. infection level during the nutritional stress period and in spring (September). Colonies from group M (monofloral) are represented in blue and colonies from group P (polyfloral) are represented in orange. Boxes show 1st and 3rd interquartile range and median represented by a line. Whiskers include the values of 90% of the samples. Significant differences of pairwise comparisons at each sampling time are represented as ** when p ≤ 0.01, and *** when p ≤ 0.001.

All colonies showed similar proportion of bees infected with Nosema spp. at the beginning of the experiment (an average of 11.8% in colonies from group M and 15.7% in colonies from group P) (Table 1; Fig. 4). The infection increased during the E. grandis flowering period in both groups to a level close to 100%, while it showed the opposite pattern from sampling 5 (autumn) to 6 (spring) (Fig. 4, Table 1). When the Nosema spp. infection level was determined by the number of spores in a pool of 60 bees, similar results were obtained (adult = nosema*treatment + (1|colony) (Table 1).

N. ceranae was the most frequently detected Nosema species in infected colonies during the experiment. Only one colony showed co-infection with N. apis and N. ceranae in sampling 1 but in sampling 5 this colony was only infected with N. ceranae.

Infection level with Nosema spp. decreased adult population, and this effect was treatment-dependent since this effect was observed only in non-supplemented colonies (Table 2).

Viruses and V. destructor infection levels

The infection level with ABPV was affected by time and treatment independently since the combination of both variables did not affected it (ABPV = time*treatment + (time|colony). Pollen supplementation increased ABPV titers in all sampling times (Table 1), while time decreased it (Table 2; Fig. 5). Similar results were observed for DWV (DWV = time*treatment + (time|colony) (Table 2). Pairwise comparisons at each sampling time indicates that the treatment effect was in samplings 3, 4 and 5 (Table 1; Fig. 5). On the other hand, the infection level with SBV was affected only by treatment, with pollen supplementation having a positive effect on this variable (SBV = time*treatment + (time|colony)) (Table 2). Pairwise comparisons indicate that this effect was evident mainly in samplings 2 and 5 (Table 1; Fig. 5). Finally, the infection level of BQCV was affected only by time since the treatment effect was not consistent in the different sampling times: the infection level of this virus was lower in supplemented colonies in sampling 3 and higher in sampling 4, while there were no differences at other sampling times (BQCV = time*treatment + (1|colony)). (Table 1; Fig. 5). The nutritional stress did not have long-term consequences in virus infection levels, since both groups of colonies showed similar ABPV, BQCV, DWV and SBV infection level in spring (Table 1; Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Infection level with Acute Bee Paralysis Virus (a), Black Queen Cell Virus (b), Deformed Wing Virus (c) and Sacbrood Bee Virus (d) during the nutritional stress period (squared in grey) and in spring. Colonies from group M (monofloral) are represented in blue and colonies from group P (polyfloral) are represented in orange. Boxes show 1st and 3rd interquartile range and median represented by a line. Whiskers include the values of 90% of the samples. Significant differences of pairwise comparisons at each sampling time are represented as * when p ≤ 0.05, ** when p ≤ 0.01, and *** when p ≤ 0.001.

V. destructor infestation level was similar in all colonies along the experiment and it followed its natural dynamic over time after treatment against the mite (Table 1).

Prevalence of L. passim

Prevalence of L. passim was low at the beginning of the experiment and at the end of the nutritional stress period (lower than 10% for both groups of colonies). This prevalence increased in spring in colonies from group M (57%) while it remained low in colonies from group P (11%). The prevalence of L. passim was not associated with the nutritional regimen in both groups of colonies (Sampling 1 χ2 = 2.89 p = 0.08; Sampling 5 χ2 = 0 p = 0.99; Sampling 6 χ2 = 2.03 p = 0.15).

Discussion

Among the multiple causes associated with the high levels of colony losses reported worldwide, nutritional stress and sanitary conditions seem to be playing a significant role in this phenomenon3,12,14,15. In this study, we analyzed how nutritional stress affects colony strength and health under field conditions. Colonies from group P consumed pollen available in the environment and the polyfloral pollen patty, while colonies from group M consumed only pollen available in the environment. Both pollen types were different according to their pollen diversity and nutritional properties. The polyfloral pollen patty provided bees with pollen from a diverse botanical origin, a high proportion of essential amino acids and high protein and lipid content. In contrast, the pollen available in the field was primarily composed of E. grandis pollen and its protein and lipid content did not satisfy the minimum requirements needed for colony maintenance and brood rearing38. A deficit in both protein and lipids is associated with precocious foraging39,40, which accelerates the aging process and leads to decreasing colony population. Pollen from Eucalyptus spp. is one of the species with the poorest lipid35,41 and has one of the highest ratios of omega 6–3 described41,42. Omega 3 is an essential fatty acid which deficiencies are associated with diseases and neurological disorders43,44. Taking these results into account, it can be considered that colonies from group M were under nutritional stress while colonies from group P had access to more abundance of pollen and also this pollen was of good nutritional value. Unexpectedly, colonies from group M collected more diverse pollen than colonies from group P. This result could be a consequence of i) a reduction in the foraging effort of the treated colonies because of the higher quantity and diversity of the pollen available they had and/or ii) an increase in the foraging behavior of colonies under nutritional stress45,46, which seems to be due to their capacity to sense this status and try to compensate it by collecting more pollen and from different sources.

The positive effect of pollen supplementation on the decrease of Nosema spp. infection in colonies located in E. grandis plantations has been previously reported33, but in this study we prove that this effect is time dependent. These results contrast with those obtained under laboratory conditions. The discrepancy between both approaches could be associated with the behavioral transition of bees in the colonies and its relationship with their nutritionally regulated physiology. In experiments performed under laboratory conditions, bees do not experience behavioral transition (because they do not have this possibility), but their physiology changes in association with nutrition47,48. Thus, in samplings performed in the laboratory at specific time points, bees fed with different diets are in different nutritional and physiological states. However, when bees become foragers in the field, their nutritional stores decreased and consequently their physiology changed23,49. In fact, Ament et al.24 proposed that most of the maturational changes in the bee physiology are associated with behavior rather than with age, and the behavioral maturation is under nutritional control50. Since nutrition affects the immune response18, it could be expected that when bees become foragers, the magnitude of their immune response is related with the food quality consumed during the nurse stage or with the minimum quantity of the food being consumed (as royal jelly) during the forager stage51,52. Thus, it could be expected that forager bees from supplemented colonies can mount a better immune response against N. ceranae than colonies under nutritional stress. This effect on the bee immunity might be triggered directly by the pollen supplementation17,18 or because of its contribution to the establishment of the gut microbiota, which has immunomodulation functions53–55. On the other hand, it should be noted that an essential mechanism for colony homeostasis is the social immune response which cannot be displayed in cage experiments56 and social immunity has been reported to be a defense mechanism for reducing the spread of N. ceranae within the colony57. In addition, the fact that Nosema spp. levels affected adult population mainly in non-supplemented colonies, suggests that the negative effects of this pathogen at colony levels are strongly associated with the nutritional status of the colonies.

Interestingly, non-supplemented colonies showed lower viral infection levels than colonies from group P. The higher infection level of viruses in supplemented colonies was not expected since it has been proposed that pollen nutrition decreased viral replication in comparison with undernourished bees19. However, our results agreed with Alaux et al.22 who suggested that larger physiological cell machinery might favor virus multiplication but it might also help bees to resist viral infection. Moreover, the higher levels of DWV observed in the supplemented colonies, are consistent with the lower infection levels of Nosema spp. also detected in these colonies, suggesting that this parasite competes for nutritional cell resources more successfully than DWV58–60. Thus, it could be expected that DWV could replicate better in supplemented colonies in comparison with colonies from the group M. Another possibility is that colonies from group M had higher infection level of virus than colonies from group P and these colonies were dead at the sampling time. Beyond the reason associated to the higher infection level of viruses in colonies from group P, these infections had no consequences on the colony strength parameters analyzed, since they were the group that showed higher population. This result contrast with the widely reported negative impact of viruses infections on honeybee colonies12,15,25. The fact that the virus levels found in this study (especially BQCV, SBV and DWV at specific sampling times) are lower than those found in the USA (Corona, pers.com.), suggest that the viral titers observed in our experiment could not have reached a minimum threshold level to decrease colony strength.

Regarding the trypanosmatid L. passim, it was not possible to find any association between the pathogen and colony nutritional stress. However, considering its low prevalence, this conclusion should be taken with caution and future studies should be carried out.

Nutritional stress had a long-term effect in the colonies since bee population did not recover in non-supplemented colonies as did the supplemented ones in spring. However, this long-term effect did not have consequences in honeybee health as both groups of colonies showed similar infection levels with the analyzed pathogens. Finally, since colonies were re-located in a favorable environment for bees after the nutritional stress period, it is not possible to discard that nutritional stress could have consequences on colony survival if they remained in the E. grandis environment.

This study shows under field conditions, how nutritional stress impacts honeybee health. Nutritional stress had a severe impact on N. ceranae infection. Although this infection had no consequences on colony loss during the nutritional stress period, it does affect colony strength in the short and long-term. On the other hand, the non-effect of virus infections on colonies strength in well-nourished colonies and the low level of virus detected compared to the ones found in countries from the northern hemisphere as in the USA, suggests that these infection levels are not enough to have a negative impact on colonies strength. Future studies comparing viral infection levels from countries from the south and north hemisphere should be done in order to address this hypothesis. Finally, it is important to notice that all these results were obtained in an in-depth study but performed in only one location and its repetition in multiple locations would be valuable in order to corroborate the results.

Methodology

Experimental design

Sixty-two colonies of honeybees Apis mellifera (hybrid between Apis mellifera mellifera, Apis mellifera ligustica and Apis mellifera scutellata) were placed in a single apiary in a E. grandis plantation (31° 15′ 58,25″S; 55° 39′ 40,32″W) in autumn, coinciding with the flowering peak of these trees (March 2015) (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. S4). All the colonies had young sister queens and were standardized regarding brood population before the beginning of the experiment61. Colonies were treated against V. destructor using Amitraz (Apilab Lab, Tandil, Argentina) 45 days prior to the start of the experiment. Pollen and honey stores were removed.

Two groups of 31 colonies each (P and M) were randomly selected. In order to avoid robbing, colonies within each group were located together between them with a distance of one meter and a half in a semi circle and both groups of colonies were separated by a distance of 15 meters. Colonies from group P consumed pollen available in the surrounding plantation’s foraging area (mainly E. grandis pollen) and were supplemented with 500 g of a polyfloral pollen patty once every 15 days during the flowering period (2 months). Colonies from group M only consumed pollen available in the E. grandis plantation’s foraging area, and therefore represent colonies under “nutritional stress”.

To identify and characterize pollen available in the environment, three honeybee colonies (not belonging to the study) were positioned next to the experimental apiary with pollen traps at the entrance. Corbicula pollen from these colonies was sampled once every 15 days (coinciding with the sampling times). One portion of the pollen obtained in all sampling times was used for determination of the botanical origin, and another portion was mixed and stored at −20 °C until the nutritional pollen analysis was performed.

Polyfloral pollen patty was prepared using stored polyfloral pollen (bee bread), collected in summer 2014–2015, from healthy bee colonies belonging to the Apiculture Section of the National Institute for Agricultural Research (INIA) La Estanzuela. This pollen was homogenized in a proportion of 15:1 of pollen:sugar syrup and the mixture was divided into portions of 500 g and stored at −20 °C.

All colonies were sampled before the experiment began (Sampling 1) and once every 15 days until the end of the flowering period (Samplings 2; 3; 4 and 5). Samplings consisted of (i) forager bees stored in ethanol to detect and quantify Nosema spp. spores, Nosema species determination and L. passim prevalence, (ii) nurse bees to detect and quantify viral infection levels (sacrificed at −80 °C), (iii) nurses bees stored in ethanol to quantify V. destructor infestation level, and iv) freshly-stored pollen from the cells next to the brood area to identify colony pollen diversity. Colony strength was estimated in all colonies through the visual inspection of adult and brood population61.

Since colonies become notably weaker if they are not removed from E. grandis environments during winter33, all the colonies were relocated to the experimental station of INIA La Estanzuela, once the flowering period ended (34° 20′ 23.72″S–57° 41′ 39.48″W). Colonies were inspected once every month during winter and colony strength was estimated61. To analyze the long-term effect of nutritional stress, all colonies were sampled in spring (September, Sampling 6) as previously described. Figure 1 summarizes the experimental design.

Pollen analysis

Pollen botanical origin

Samples of the polyfloral pollen patty, pollen available in the foraging area and freshly-stored pollen from the cells next to the brood area were analyzed to determine their botanical origin. At least 1200 pollen grains per sample were identified (400 grains per slide, 3 slides per sample) and the percentage of each pollen species was calculated62.

Crude protein, lipid content and amino acid composition

Samples of the polyfloral pollen patty and pollen available in the surrounding foraging area were also analyzed to evaluate their nutritional composition. For crude protein analysis, pollen samples (5 g) were dried at 60 °C, and the protein content was quantified using the Kjeldahl acid digestion technique37. Lipid content was analyzed as the percentage of the etheric extract63 and to assess amino acid composition, pollen samples were processed, derivatized and analyzed by HPLC (CBO Laboratory, Brazil)64–66.

Pesticides analysis

The polyfloral pollen patty was analyzed to detect the presence of thirty-three different pesticides including the most widely used in Uruguayan agriculture. Pollen samples (5 g) were processed for pesticide detection and quantification according to Niell et al.67.

Pathogens detection

Although polyfloral pollen was collected from healthy colonies, the polyfloral pollen patty was analyzed to detect for the presence of Nosema spp. and RNA viruses. A pollen sample (0.3 g) was processed according to the protocol described by Singh et al.68. The obtained supernatant was used for RNA extraction and viral quantification, and the pellet was used for DNA extraction and Nosema spp. analysis.

Detection and quantification of Nosema spp. spores

The infection level of Nosema spp. was determined as the proportion of infected bees (N = 30) and as the number of spores in a pool of bees (N = 60) in ten randomly selected colonies per group69. In addition, the Nosema species were identified in the same colonies in samplings 1, 5 (E. grandis flowering period) and 6 (next spring). Forager bees (N = 20 per sample) were processed as described in Anido et al.70 and 500 µl of the homogenate was used for DNA extraction using the Purelink Genomic DNA minikit (Invitrogen, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Nosema species determination was carried out using the protocol described by Martín-Hernández et al.71, including negative and positive controls.

Detection and quantification of RNA viruses

Virus detection and quantification in pollen were assessed by absolute quantification. The supernatant (900 µl) was mixed with an equal volume of chloroform and RLT buffer (Qiagen, USA) and centrifuged for 30 min at 11,000 rpm. Then, the aqueous phase was used for RNA extraction using the RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, USA). cDNA was synthesized using 2000 ng of RNA using the High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems, Lithuania). For both procedures, the manufacturer’s instructions were followed. The infection levels of Acute bee paralysis virus (ABPV), Black queen cell virus (BQCV), Deformed Wing Virus (DWV) and Sacbrood bee virus (SBV) were determined by quantitative PCR (qPCR) using primers previously described72,73. qPCR was performed in a final volume of 10 µl containing 5 µl of the Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, UK), 1 µM of each specific primer and 3 µl of cDNA. Negative controls were included as well as a standard curve which consisted of seven dilution points of a plasmid containing the amplified product. The thermal cycling program consisted of a denaturation step of 10 min at 95 °C, 40 cycles of 30 s at 95 °C and 1 min at 60 °C followed by a melting curve from 60 °C to 95 °C.

Virus detection and quantification in bees were assessed by relative quantification. Nurse bees (N = 20 per colony) were processed according to Anido et al.70, and 140 µl of the final supernatant was used for RNA extraction using the Purelink Viral RNA/DNA kit (Invitrogen, USA), following the manufacturer’s instructions. The co-purified DNA was digested with DNase I Amp Grade (Invitrogen, USA) and cDNA synthesis was performed using the High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems, Lithuania) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. cDNA was used to determine the infection level of ABPV, BQCV, DWV and SBV by qPCR74,75. qPCR was performed in a final volume of 20 µl, containing 10 µl of the Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, UK), 0.3 µM of each specific primer, 2 µl of cDNA and 7.76 µl of water. Negative controls including water instead of cDNA were used in each run. An inter-run calibrator plate sample and a standard curve were also included. The geometric mean of the expression level of the housekeeping genes β-actin76 and RPS-577 was used for the results normalization78. The cycling program consisted of a denaturation step of 10 min at 95 °C, 40 cycles of 15 s at 95 °C, 30 s at 50 °C (46 °C for SBV) and 30 s at 60 °C. Specificity of the reactions was checked by melting curve analysis of the amplified products (from 65 °C to 95 °C). Infection level of the different viruses were analyzed by the method described by Pfaffl79. All qPCR reactions were performed in a CFX96 TouchTM Real-Time PCR System (Biorad).

Quantification of V. destructor

V. destructor infestation was monitored at each sampling time with 200–300 nurse bees per colony, according to the protocol described by Dietmann et al.80.

Detection of Lotmaria passim

DNA obtained as described previously was used to detect the presence of L. passim by PCR according to Arismendi et al.81. Negative and positive controls for L. passim were included. The prevalence of this trypanosomatid was calculated as the relation between the number of infected colonies and the total number of colonies analyzed per group and per sampling time.

Statistical analysis

Generalized linear mixed models (GLMM) were used to assess the relationship between treatment (M or P) and time (both as fixed effects), and colony strength and pathogen infection levels (as dependent variables) (package {lme4})82,83. The identity of the colonies was considered as a random effect, and random intercept or slope was chosen in each model according to the variability of each dependent variable intra and inter colony, respectively. In the case of adult and brood population, a GLMM with poisson distribution and a log link function was used. In the case of Nosema spp. infection and virus titers, a GLMM with gamma distribution and a log link function were used. To assess the effect of Nosema spp. infection in adult population, a GLMM with poisson distribution and a log link function was done considering adult population as dependent variable and Nosema spp infection and treatment as independent variables.

In addition, differences in the colony strength parameters and infection levels of the different pathogens between groups P and M at different sampling times were analyzed. T-student or Mann Whitney U Test were applied if the variables fitted the assumptions of parametric statistics. Differences in the prevalence of L. passim between groups were analyzed using the χ2 Test82. Pollen diversity collected in the colonies was analyzed as the Shannon diversity index and differences between groups P and M and in sampling times were analyzed with Kruskal Wallis and Mann Whitney U Test (package {agricole})82,84. Differences in colony mortality between both groups of colonies were assessed using the χ2 Test82. In all cases, R Studio software was used and p-values under 0.05 were considered statistical significant.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

Authors thank Cecilia Chambón, Eduardo Porley, Gustavo Ramallo, Nestor Viera and Rodrigo Méndez for their technical support and to Shayne Madella for the language revisions. This study was financed by the University of the Republic (CAP and CSIC C624) and National Agency for Research and Innovation (FMV_3_2016_1_125435 and POS_NAC_2014_1_102247).

Author Contributions

B.B., I.C., M.Y. and A.K. designed the experiments. B.B., C.L., D.-C.S., I.C., M.Y. and S.C. performed the experiment. B.B., C.L. and S.E. analyzed the samples. B.B. and G.M.E. analyzed the data. B.B., C.L., C.M., I.C., Z.P. and A.K. contributed to the discussion and wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-46453-9.

References

- 1.Kim KC. Biodiversity, conservation and inventory: why insects matter. Biodivers. Conserv. 1993;2:191–214. doi: 10.1007/BF00056668. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jankielsohn A. The Importance of Insects in Agricultural Ecosystems. Adv. Entomol. 2018;06:62–73. doi: 10.4236/ae.2018.62006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goulson D, Nicholls E, Botías C, Rotheray EL. Bee declines driven by combined Stress from parasites, pesticides, and lack of flowers. Science (80-.). 2015;347:1255957. doi: 10.1126/science.1255957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Potts SG, et al. Global pollinator declines: trends, impacts and drivers. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2010;25:345–353. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2010.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Williams IH. The dependence of crop production within the European Union on pollination by honey bees. Agric. Zool. Revis. 1994;6:229–257. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morse, R. A. & Calderone, N. W. The Value of Honey Bees As Pollinators of U. S. Crops. Bee Cult. 1–15 (2000).

- 7.FAO. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. FAOSTAT Live animals (2018).

- 8.Moritz RFA, Erler S. Lost colonies found in a data mine: Global honey trade but not pests or pesticides as a major cause of regional honeybee colony declines. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2016;216:44–50. doi: 10.1016/j.agee.2015.09.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.vanEngelsdorp D, Meixner MD. A historical review of managed honey bee populations in Europe and the United States and the factors that may affect them. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2010;103:S80–S95. doi: 10.1016/j.jip.2009.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith KM, et al. Pathogens, Pests, and Economics: Drivers of Honey Bee Colony Declines and Losses. Ecohealth. 2013;10:434–445. doi: 10.1007/s10393-013-0870-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Requier F, et al. Trends in beekeeping and honey bee colony losses in Latin America. J. Apic. Res. 2018;57:657–662. doi: 10.1080/00218839.2018.1494919. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Steinhauer N, et al. Drivers of colony losses. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 2018;26:142–148. doi: 10.1016/j.cois.2018.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carreck N, Neumann P. Honey bee colony losses. J. Apic. Res. 2010;49:1. doi: 10.3896/IBRA.1.49.1.01. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Naug D. Nutritional stress due to habitat loss may explain recent honeybee colony collapses. Biol. Conserv. 2009;142:2369–2372. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2009.04.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dainat B, Evans JD, Chen YP, Gauthier L, Neumann P. Predictive markers of honey bee colony collapse. PLoS One. 2012;7:e32151. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crailsheim K. The protein balance of the honey bee worker. Apidologie. 1990;21:417–429. doi: 10.1051/apido:19900504. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Di Pasquale G, et al. Influence of Pollen Nutrition on Honey Bee Health: Do Pollen Quality and Diversity Matter? PLoS One. 2013;8:1–13. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0072016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alaux C, Ducloz F, Crauser D, Le Conte Y. Diet effects on honeybee immunocompetence. Biol. Lett. 2010;6:562–565. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2009.0986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.DeGrandi-Hoffman G, Chen Y, Huang E, Huang MH. The effect of diet on protein concentration, hypopharyngeal gland development and virus load in worker honey bees (Apis mellifera L.) J. Insect Physiol. 2010;56:1184–1191. doi: 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2010.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Porrini MP, et al. Nosema ceranae development in Apis mellifera: influence of diet and infective inoculum. J. Apic. Res. 2011;50:35–41. doi: 10.3896/IBRA.1.50.1.04. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Basualdo M, Barragán S, Antúnez K. Bee bread increases honeybee haemolymph protein and promote better survival despite of causing higher Nosema ceranae abundance in honeybees. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 2014;6:396–400. doi: 10.1111/1758-2229.12169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alaux C, Dantec C, Parrinello H, Le Conte Y. Nutrigenomics in honey bees: Digital gene expression analysis of pollen’s nutritive effects on healthy and varroa-parasitized bees. BMC Genomics. 2011;12:496. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Toth AL, Robinson GE. Worker nutrition and division of labour in honeybees. Anim. Behav. 2005;69:427–435. doi: 10.1016/j.anbehav.2004.03.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ament SA, Wang Y, Robinson GE. Nutritional regulation of division of labor in honey bees: Toward a systems biology perspective. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Syst. Biol. Med. 2010;2:566–576. doi: 10.1002/wsbm.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dainat B, Evans JD, Chen YP, Gauthier L, Neumanna P. Dead or alive: Deformed wing virus and Varroa destructor reduce the life span of winter honeybees. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012;78:981–987. doi: 10.1128/AEM.06537-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cox-Foster DL, et al. A metagenomic survey of microbes in honey bee colony collapse disorder. Science. 2007;318:283–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1146498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Higes M, Meana A, Bartolomé C, Botías C, Martín-Hernández R. Nosema ceranae (Microsporidia), a controversial 21st century honey bee pathogen. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 2013;5:17–29. doi: 10.1111/1758-2229.12024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Higes M, et al. Honeybee colony collapse due to Nosema ceranae in professional apiaries. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 2009;1:110–113. doi: 10.1111/j.1758-2229.2009.00014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Higes M, et al. How natural infection by Nosema ceranae causes honeybee colony collapse. Environ. Microbiol. 2008;10:2659–2669. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2008.01687.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gisder S, et al. Five-year cohort study of nosema spp. in Germany: Does climate shape virulence and assertiveness of Nosema ceranae? Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2010;76:3032–3038. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03097-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Paxton R. Does infection by Nosema ceranae cause ‘Colony Collapse Disorder’ in honey bees (Apis mellifera)? J. Apic. Res. 2010;49:80. doi: 10.3896/IBRA.1.49.1.11. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Langridge DF. Nosema Disease of the Honeybee and Some Investigations into Its Control in Victoria, Australia. Bee World. 1961;42:36–40. doi: 10.1080/0005772X.1961.11096838. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Invernizzi C, et al. Sanitary and Nutritional Characterization of Honeybee Colonies in Eucalyptus Grandis Plantations. Arch. Zootec. 2011;60:1303–1314. doi: 10.4321/S0004-05922011000400045. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jack CJ, Uppala SS, Lucas HM, Sagili RR. Effects of pollen dilution on infection of Nosema ceranae in honey bees. J. Insect Physiol. 2016;87:12–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2016.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Somerville, D. C. Nutritional Value of Bee Collected Pollen. Rural Ind. Res. Dev, Corp. 1–166 (2001).

- 36.Manning R. Fatty acids in pollen: A review of their importance for honey bees. Bee World. 2001;82:60–75. doi: 10.1080/0005772X.2001.11099504. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Somerville, D. C. & Nicol, H. I. Crude protein and amino acid composition of honey bee-collected pollen pellets from south-east Australia and a note on laboratory disparity. Aust. J. Exp. Agric.46, 141–149 (2006).

- 38.Herbert EJ, Shimanuki H, Caron D. Optimum protein levels required by honey bees (Hymenoptera, Apidae) to initiate and maintain brood rearing. Apidologie. 1977;8:141–146. doi: 10.1051/apido:19770204. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Toth AL. Nutritional status influences socially regulated foraging ontogeny in honey bees. J. Exp. Biol. 2005;208:4641–4649. doi: 10.1242/jeb.01956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nilsen K-A, et al. Insulin-like peptide genes in honey bee fat body respond differently to manipulation of social behavioral physiology. J. Exp. Biol. 2011;214:1488–1497. doi: 10.1242/jeb.050393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Arien Y, Dag A, Zarchin S, Masci T, Shafir S. Omega-3 deficiency impairs honey bee learning. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2015;112:201517375. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1517375112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Roulston T’ai H., Cane James H. Pollen and Pollination. Vienna: Springer Vienna; 2000. Pollen nutritional content and digestibility for animals; pp. 187–209. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brenna JT. Animal studies of the functional consequences of suboptimal polyunsaturated fatty acid status during pregnancy, lactation and early post-natal life. Matern. Child Nutr. 2011;7:59–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8709.2011.00301.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Watson, R. R. & Meester, F. De. Omega-3 fatty acids in brain and neurological health. (Elsevier, 2014).

- 45.Fewell JH, Winston ML. Colony state and regulation of pollen foraging in the honey bee. Apis mellifera L. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. Sociobiol. 1992;30:387–393. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dreller C, Page RE, Jr., Fondrk MK. Regulation of pollen foraging in honeybee colonies: effects of young brood, stored pollen, and empty space. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 1999;45,:227–233. doi: 10.1007/s002650050557. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bomtorin AD, et al. Juvenile hormone biosynthesis gene expression in the corpora allata of honey bee (Apis mellifera L.) female castes. PLoS One. 2014;9:e86923. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0086923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Guidugli KR, et al. Vitellogenin regulates hormonal dynamics in the worker caste of a eusocial insect. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:4961–4965. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.07.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Corona M, et al. Vitellogenin, juvenile hormone, insulin signaling, and queen honey bee longevity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:7128–7133. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701909104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ament SA, Corona M, Pollock HS, Robinson GE. Insulin signaling is involved in the regulation of worker division of labor in honey bee colonies. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:4226–4231. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800630105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Crailsheim K. Trophallactic interactions in the adult honeybee (Apis mellifera L.) Apidologie. 1998;29:97–112. doi: 10.1051/apido:19980106. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Camazine S, et al. Protein trophallaxis and the regulation of pollen foraging by honey bees (Apis mellifera L.) Apidologie. 1998;29:113–126. doi: 10.1051/apido:19980107. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Engel P, Moran NA. The gut microbiota of insects - diversity in structure and function. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2013;37:699–735. doi: 10.1111/1574-6976.12025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kwong WK, Mancenido AL, Moran NA. Immune system stimulation by the native gut microbiota of honey bees. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2017;4:170003. doi: 10.1098/rsos.170003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Powell JE, Martinson VG, Urban-Mead K, Moran NA. Routes of acquisition of the gut microbiota of the honey bee Apis mellifera. Appl. Environ. Microbiol . 2014;80,:7378–7387. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01861-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cremer S, Armitage SAO, Schmid-Hempel P. Social Immunity. Curr. Biol. 2007;17:693–702. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Biganski S, Kurze C, Müller MY, Moritz RFA. Social response of healthy honeybees towards Nosema ceranae-infected workers: care or kill? Apidologie. 2018;49:325–334. doi: 10.1007/s13592-017-0557-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Doublet V, Natsopoulou ME, Zschiesche L, Paxton RJ. Within-host competition among the honey bees pathogens Nosema ceranae and Deformed wing virus is asymmetric and to the disadvantage of the virus. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2015;124:31–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jip.2014.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tritschler M, Retschnig G, Yañez O, Williams GR, Neumann P. Host sharing by the honey bee parasites Lotmaria passim and Nosema ceranae. Ecol. Evol. 2017;7:1850–1857. doi: 10.1002/ece3.2796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Costa C, Tanner G, Lodesani M, Maistrello L, Neumann P. Negative correlation between Nosema ceranae spore loads and deformed wing virus infection levels in adult honey bee workers. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2011;108:224–225. doi: 10.1016/j.jip.2011.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Delaplane KS, Steen JVD, Guzman-novoa E. Standard methods for estimating strength parameters of Apis mellifera colonies Métodos estándar para estimar parámetros sobre la fortaleza de las colonias de Apis mellifera. J. Apic. Res. 2013;52:1–12. doi: 10.3896/IBRA.1.52.4.12. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Louveaux J, Maurizio A, Vorwohl G. Methods of melissopalynology. Bee World. 1978;5:139–153. doi: 10.1080/0005772X.1978.11097714. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sindicato Nacional da Indústria de Alimentação Animal. Compêndio Brasileiro de Alimentação Animal. Gravimetria-Method 14. https://sindiracoes.org.br/compendio-brasileiro-de-alimentacao-animal-2013/ (2013).

- 64.White JA, Hart RJ, Fry JC. An evaluation of the Water Pico-Tag system for the amino-acid analysis of food materials. J. Automat. Chem. 1986;8:170–177. doi: 10.1155/S1463924686000330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hagen SR, Augustin J, Grings E, Tassinari P. Precolumn phenylisothiocyanate derivatization and liquid chromatography of free amino acids in biological samples. Food Chem. 1993;46:319–323. doi: 10.1016/0308-8146(93)90127-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lucas B, Sotelo A. Effect of different alkalies, temperature, and hydrolysis times on tryptophan determination of pure proteins and of foods. Anal. Biochem. 1980;109:192–197. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(80)90028-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Niell S, et al. QuEChERS Adaptability for the Analysis of Pesticide Residues in Beehive Products Seeking the Development of an Agroecosystem Sustainability Monitor. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2015;63:4484–4492. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.5b00795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Singh R, et al. RNA viruses in hymenopteran pollinators: Evidence of inter-taxa virus transmission via pollen and potential impact on non-Apis hymenopteran species. PLoS One. 2010;5:e14357. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Fries I, et al. Standard methods for nosema research. J. Apic. Res. 2013;52:1–28. doi: 10.3896/IBRA.1.52.1.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Anido M, et al. Prevalence and distribution of honey bee pathogens in Uruguay. J. Apic. Res. 2016;54:532–540. doi: 10.1080/00218839.2016.1175731. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Martín-Hernandez R, et al. Outcome of colonization of Apis mellifera by Nosema ceranae. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007;73:6331–6338. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00270-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.de Miranda JR, Cordoni G, Budge G. The Acute bee paralysis virus-Kashmir bee virus-Israeli acute paralysis virus complex. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2010;103:S30–S47. doi: 10.1016/j.jip.2009.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Locke B, Forsgren E, Fries I, de Miranda JR. Acaricide treatment affects viral dynamics in Varroa destructor-infested honey bee colonies via both host physiology and mite control. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012;78:227–35. doi: 10.1128/AEM.06094-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kukielka D, Esperón F, Higes M, Sánchez-Vizcaíno JM. A sensitive one-step real-time RT-PCR method for detection of deformed wing virus and black queen cell virus in honeybee Apis mellifera. J. Virol. Methods. 2008;147:275–281. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2007.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Johnson RM, Evans JD, Robinson GE, Berenbaum MR. Changes in transcript abundance relating to colony collapse disorder in honey bees (Apis mellifera) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:14790–14795. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906970106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Yang X, Cox-Foster DL. Impact of an ectoparasite on the immunity and pathology of an invertebrate: evidence for host immunosuppression and viral amplification. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:7470–7475. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501860102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Evans JD. Beepath: An ordered quantitative-PCR array for exploring honey bee immunity and disease. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2006;93:135–139. doi: 10.1016/j.jip.2006.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Vandesompele J, et al. Accurate normalization of real-time quantitative RT-PCR data by geometric averaging of multiple internal control genes. Genome Biol. 2002;3:RESEARCH0034. doi: 10.1186/gb-2002-3-7-research0034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Pfaffl MW. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:e45. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.9.e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Dietemann V, et al. Standard methods for varroa research. J. Apic. Res. 2013;52:1–54. doi: 10.3896/IBRA.1.52.1.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Arismendi N, Bruna A, Zapata N, Vargas M. PCR-specific detection of recently described Lotmaria passim (Trypanosomatidae) in Chilean apiaries. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2016;134:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jip.2015.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing (2017).

- 83.Bates, D., Maechler, M., Bolker, B., Walker, S. Fitting Linear Mixed-Effects Models Using lme4. J. Stat. Softw.67, 1–48 (2015).

- 84.Mendiburu, F. agricolae: Statistical Procedures for Agricultural Research (2017).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.