Abstract

Objectives

This study aimed to develop an empowerment model for burnout syndrome and quality of nursing work life (QNWL).

Methods

This study adopted a mixed-method cross-sectional approach. The variables included structural empowerment, psychological empowerment, burnout syndrome and QNWL. The population consisted of nurses who have civil servant status in one of the regional hospitals in Indonesia. The participants were recruited using multi-stage sampling measures with 134 respondents. Data were collected using questionnaires, which were then analysed using partial least squares. A focus group discussion was conducted with nurses, chief nurses and the hospital management to identify strategic issues and compile recommendations.

Results

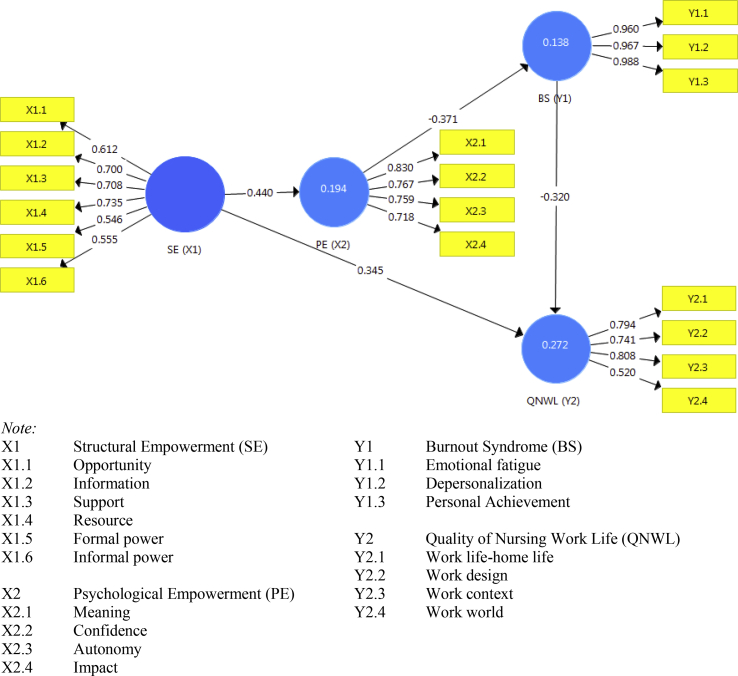

Structural empowerment influenced psychological empowerment (path coefficient = 0.440; t = 6.222) and QNWL (path coefficient = 0.345; t = 4.789). Psychological empowerment influenced burnout syndrome (path coefficient = −0.371; t = 4.303), and burnout syndrome influenced QNWL (path coefficient = −0.320; t = 5.102). Structural empowerment increased QNWL by 39.7%.

Conclusion

The development of a structural empowerment model by using the indicators of resources, support and information directly influenced the psychological empowerment of the sample of nurses. As an indicator of meaning, psychological empowerment decreased burnout syndrome. In turn, burnout syndrome, as the indicator of personal achievement, could affect the QNWL. Structural empowerment directly influenced the QNWL, particularly within the workplace context. Further studies must be conducted to analyse the effects of empowerment, leadership styles and customer satisfaction.

Keywords: Burnout, Empowerment, Nurses, Quality of working life

1. Introduction

The lack of nurse empowerment in a hospital is related to stress and poor working conditions and is the main source of nurse fatigue [1]. Such a situation reduces work satisfaction and increases the risk of burnout [2,3]. Nurses who cannot overcome work stress are prone to emotional, physical and mental fatigue and low self-appreciation [4]. Fatigue is associated with an imbalance between the number of nurses and their perceived workload. Such imbalance can result in unhealthy relationships among nurses, decreased creativity and the onset of burnout [5].

Human resource is one of the crucial factors in nurse development [[6], [7], [8]] and is a vital element of most organisations [7] as it refers to the employees who provide a service or product [2]. Nurses are a significant resource of a hospital, accounting for 55%–65% of a facility's operating budget [8,9]. Nurse empowerment remains a key strategy for improving professional engagement and role development in hospital settings.

Workplace empowerment is a proven strategy for creating a positive workspace environment in organisations [3]. A successful organisation requires employees who are agile, responsive and independent [10]. A study on structural empowerment revealed that the process and structure within a health organisation was associated with the professional engagement even of the nursing cadre [11]. Appropriate human resources can strengthen the capabilities and commitment of employees [12].

Nurse empowerment in an organisation can positively impact both employee and customer satisfaction [1]. In general, hospitals dismiss strategies that could empower employees. However, the opposite is true at the Dr. Haryoto Regional Hospital, which provides nurses with opportunities to participate in education, training, seminars and workshops to improve their knowledge, competencies and skills. The team care model used in this hospital is responsible for the nursing care provided to a patient. Each team member is expected to become empowered to plan and deliver appropriate care.

In a preliminary study conducted at Dr. Haryoto Regional Hospital, Lumajang, out of 347 employees, 199 (57.3%) are categorised as civil servants. As a form of nurse involvement in working, structural empowerment was 50%, whereas psychological empowerment was less than 45%. Meanwhile, nurse empowerment in their working environment can increase performance growth [13], and ignoring this condition would negatively affect their motivation. Such a situation threatens organisational productivity because less-empowered nurses are more prone to burnout and low employee satisfaction [4,7].

Work-related stress can decrease employee performance [14], work satisfaction and commitment, resulting in employees quitting their jobs (i.e. high turnover rates and low retention) [15]. The work satisfaction of nurses can be generally used to assess quality of work life [16]. In 1976, Kanter's theory of “power in organisations” offered a framework that can guide a nurse manager to create employee empowerment. Empowerment helps nurses to negotiate for a reasonable workload, maintain control over their own work, and develop good working relationships. In addition, nurses are more likely to be treated as proportionally and equally, rewarded for their contribution and recognised within the organisation [1]. Laschinger theory explains that structural empowerment consists of opportunity, information, support, resources, formal power and informal power of individuals within the organisation [13]. Laschinger [17] found that nurses who perceive to be empowered in their workplace have increased psychological empowerment, which includes a sense of meaning, confidence, autonomy and impact.

Empowerment strategies are crucial for improving the involvement [18] and reducing the fatigue of nurses [19]. Nursing management plays a key role in creating a positive work environment that allows nurses to experience the benefits [18,20] and thus improve the quality of services to the client [21]. Thus, this study aimed to develop a model of empowerment for burnout syndrome and QNWL in one particular hospital setting.

2. Material and methods

This study was conducted from February 2017 to June 2017 at the Dr. Haryoto Regional Hospital, which is a 200-bed facility located in Lumajang, Indonesia. This study adopted a mixed-method cross-sectional approach through multistage sampling. The population included nurses from four units: critical care, inpatient, outpatient and surgery. The inclusion criteria were nurse associates who have been employed for at least five years and who have a minimum education of diploma III. The first stage involved cluster sampling, which refers to grouping associate nurses by unit for four units. The second stage involved stratified sampling to consider the number of respondents representing each unit. The third stage involved simple random sampling. The number of respondents by unit was as follows: inpatient nurses (n = 55), critical and emergency care nurses (n = 38), operating room nurses (n = 22) and outpatient nurses (n = 19) (total nurses = 134).

The data were gathered using six questionnaires, namely, Condition for Work Effectiveness Questionnaire (CWEQ-II) [17], Job Activities Scale (JAS) [17], Organisational Relationship Scale (ORS) [17], Psychological Empowerment Scale (PES) [22], Maslach Burnout Inventory [23] and QNWL by Brooks and Brooks (2004) [24]. The details of each questionnaire were as follows. (1) CWEQ-II consists of 19 statements rated with a five-point rating scale. This questionnaire includes resources, supports, information, opportunities, formal power and informal power. (2) JAS contains nine items rated on a five-level Likert scale that measured the formal power within the work environment. This tool measures the perception of job flexibility and recognition within the workplace. (3) ORS contains 18 items that measure informal power. This tool measures the nurses' perception of sponsor support, peer networking, political alliances and subordinate relationship. (4) MBI measures the perceived frequency of burnout. The tool consists of 22 questions rated by five-scale Likert-type answers. This inventory explores depersonalisation, emotional exhaustion and personal accomplishment. (5) The QNWL questionnaire is a self-administered questionnaire that consists of component work life–home life, work design, work context, and work world of the nurse. (6) PES measures the empowerment aspect, which is divided into meaning, confidence, autonomy and impact. This scale consists of 12 items scored with a five-point rating scale. For all of these questionnaires, five answers can be given: 1 = ‘none’, 2 = ‘a little’, 3 = ‘some’, 4 = ‘many’ and 5 = ‘a lot’. The scores were grouped into four categories, namely, good, adequate and inadequate. All of the aforementioned tools were appraised for their validity and reliability coefficient levels. The analysis was conducted using partial least squares (PLS). The result of the PLS was used as the basis to determine strategical issues and discussed in a focus group discussion (FGD) to compile the recommendation and empowerment strategic modules for nurses. The FGD participants consisted of 14 nurses, 15 room managers, and 8 individuals from the management structure of the Dr. Haryoto Regional Hospital.

This research was approved by the Research Ethical Committee of the Faculty of Nursing, Universitas Airlangga, Surabaya (number 347-KEPK).

3. Results

The data were analysed using PLS on the SPSS software with the assistance of the Smart PLS-3 program. Table 1 provides the demographic data of the participants. The majority of the subjects were female (61.2%), and 49.3% had completed undergraduate degrees. The majority of the nurses (33.6%) were between 36 and 40 years old, and more than half (51.5%) had 5–10 years of work experience. All nurses employed at the Dr Haryoto Regional Hospital were required to complete the Emergency Care Training and Basic Cardiac Life Support certificates. Most (80.6%) were classified as clinical nurse III. All nurses had an educational background of DIII nursing and a work experience of at least 5 years in this hospital.

Table 1.

Distribution of respondent characteristics (n = 134).

| Characteristics | Category | n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 52 (38.8) |

| Female | 82 (61.2) | |

| Age(year) | 26–30 | 16 (11.9) |

| 31–35 | 38 (28.4) | |

| 36–40 | 45 (33.6) | |

| 41–45 | 20 (14.9) | |

| 46–50 | 13 (9.7) | |

| >50 | 2 (1.5) | |

| Latest education | D3 (3-year diploma) | 64 (47.8) |

| D4 (4-year diploma) | 4 (2.9) | |

| S1 (undergrad) | 66 (49.3) | |

| Work tenure (civil servant status) (years) | 5–10 | 69 (51.5) |

| 11–20 | 42 (31.3) | |

| 21–30 | 21 (15.7) | |

| > 30 | 2 (1.5) | |

| Career path | Clinical nurse I | 5 (3.7) |

| Clinical nurse II | 8 (6.0) | |

| Clinical nurse III | 108 (80.6) | |

| Clinical nurse IV | 13 (9.7) | |

| Types of training | PPGD/BCLS | 134 (100) |

| Haemodialysis | 10 (7.5) | |

| Anaesthesia | 7 (5.3) | |

| Clinical instructor | 6 (4.5) | |

| Ward management | 5 (3.7) | |

| Basic training on life support | 4 (2.9) | |

| Neonatal intensive care unit | 4 (2.9) | |

| Basic paediatric care | 3 (2.2) | |

| ICU | 3 (2.2) | |

| ECG | 3 (2.2) | |

| Instrument | 2 (1.5) | |

| RR | 2 (1.5) | |

| Operating theatre basic nursing | 2 (1.5) | |

| BLS, NLS, GELS, PPI | 4 (2.9) |

Table 2 presents the variables of structural empowerment. Formal power was the lowest and was in the inadequate category (less than 41%), and it had a mean of 8.95. By contrast, information was in the adequate category (56%), and it had a mean of 9.75. In psychological empowerment, the lowest was autonomy, which was in the adequate category (42%), and it had a mean of 11.05. Emotional fatigue was in the good category (92%), and it had a mean of 19.18. At the QNWL, work design received 71%, and work world reached 66%.

Table 2.

Distribution of research variables of the development of an empowerment model for burnout syndrome and quality of nursing work life (n = 134).

| Variable | Categories [n (%)] |

μ | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Good | Adequate | Inadequate | Score | ||

| Opportunity | 62 (46) | 54 (40) | 18 (13) | 11.16 | 3–15 |

| Information | 34 (25) | 75 (56) | 28 (21) | 9.75 | 3–15 |

| Support | 39 (29) | 77 (57) | 18 (13) | 10.32 | 3–15 |

| Resource | 38 (28) | 72 (54) | 24 (18) | 10.29 | 3–15 |

| Formal power | 20 (15) | 59 (44) | 55 (41) | 8.95 | 3–15 |

| Informal power | 39 (29) | 68 (51) | 27 (20) | 13.26 | 4–20 |

| Meaning | 84 (63) | 39 (29) | 11 (8) | 11.77 | 3–15 |

| Confidence | 85 (63) | 38 (28) | 11 (8) | 11.89 | 3–15 |

| Autonomy | 65 (49) | 56 (42) | 13 (10) | 11.04 | 3–15 |

| Impact | 81 (60) | 45 (34) | 8 (6) | 11.41 | 3–15 |

| Burnout syndrome | |||||

| Emotional fatigue | 123 (92) | 11 (8) | 0 | 19.18 | 9–45 |

| Depersonalisation | 131 (98) | 3 (2) | 0 | 8.38 | 5–25 |

| Personal achievement | 2 (1) | 22 (16) | 110 (82) | 19.00 | 8–40 |

| QNWL | |||||

| Work life–home life | 53 (40) | 70 (52) | 11 (8) | 25.42 | 7–35 |

| Work design | 32 (24) | 95 (71) | 7 (5) | 31.67 | 9–45 |

| Work context | 73 (54) | 61 (46) | 0 | 75.50 | 20–100 |

| Work world | 24 (1) | 88 (66) | 22 (16) | 16.67 | 5–25 |

The results of the hypothesis test of the developed empowerment model for burnout syndrome and QNWL are presented in Table 3. Structural empowerment influenced psychological empowerment [1] and QNWAL [3] but not burnout syndrome [2]. Psychological empowerment influenced burnout syndrome [4] but not QNWL [5]. Burnout syndrome influenced QNWL [6].

Table 3.

Final model of results of the hypothesis test on the development of an empowerment model for burnout syndrome and quality of nursing work life.

| Variable | Path coefficients | t | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| The influence of structural empowerment (X1) on psychological empowerment (X2) | 0.440 | 6.083 | <0.001 |

| The influence of structural empowerment (X1) on QNWL (Y2) | 0.345 | 4.870 | <0.001 |

| The influence of psychological empowerment (X2) on burnout syndrome (Y1) |

−0.371 | 4.179 | <0.001 |

| The influence of burnout syndrome (Y1) on QNWL (Y2) | −0.320 | 4.761 | <0.001 |

As shown in Fig. 1, the influence of structural empowerment on QNWL had a path coefficient of 0.345. The influence of structural empowerment towards QNWL through psychological empowerment and burnout syndrome had a path coefficient of 0.052 (0.440 × −0.371 × −0.320). These findings can be interpreted that the increasing QNWL was achieved through structural empowerment (0.345 > 0.052). The total effect gained from the influence of structural empowerment on QNWL was 0.397 (0.345 + 0.052).

Fig. 1.

The development of empowerment model for burnout syndrome and quality of nursing work life in Indonesia.

Fig. 1 shows that structural empowerment increased QNWL by 34.5%. Structural empowerment through psychological empowerment and burnout syndrome increased QNWL by 5.2%. These data can be interpreted that Kanter's model of structural empowerment can increase QNWL by 39.7%.

During FGD, all nurses reported the following concerns regarding the development of an empowerment model that considered burnout and QNWL: (1) to consistent and equitable participation in and conduction of seminars and trainings and facilitation of continuing education; (2) continuous communication from the smallest unit to the highest rank of nursing management; (3) transparency of reward and punishment in improving nursing performance; (4) integration of management information systems for nursing with hospital information systems; (5) strengthening inter-professional communication and collaboration with focus on patient safety; (6) scheduled transfer between units to reduce fatigue and stress; and (7) reassessment of the working shift, personal protective equipment, and work environment and facilitation of general check-up on a regular basis by the human resource management unit (Table 4).

Table 4.

Results of the development of an empowerment model for burnout syndrome and quality of nursing work life.

| Structure | Standard | Things to be developed |

|---|---|---|

| Structural empowerment |

|

|

| Psychological empowerment |

|

|

| Burnout syndrome |

|

|

| Quality of nursing work life |

|

|

4. Discussion

The findings of this study supported Kanter's development of an empowerment model for burnout syndrome and QNWL through statistical and expert comments.

4.1. Main findings

The nurse empowerment model can improve structural empowerment, leading to psychological empowerment and reduced burnout syndrome, which will impact the QNWL. Three indicators can have a vital role in improving structural empowerment, namely, resources, support and information. Resources to support nurses, such as doing administrative duties (e.g. billing) and collaborating with other health care professionals, enable nurses to provide optimal patient care. Nurses also need support from co-workers, other nurses and hospital staff. In performing nursing duties, a team can provide guidance, support and constructive information to assist the nurse. Continuous and complete information must be received by team members, especially nurses, through effective communication and coordination, such as at shift hand over reports and periodic team meetings.

Meaning influences psychological empowerment. For nurses, meaning can be translated as their role trust, values and attitude in providing care services. To establish compatibility between the classification of the work roles and the job descriptions in the team model, nurses must understand individual duties to function in a team. To achieve this goal, the function and expectation of the team needs to be discussed; and a follow up must be conducted after implementation to create good teamwork and prevent work fatigue.

Nurses who lack the feeling of personal achievement when carrying out duties can be an early indicator of burnout syndrome. The absence of appreciation by the hospital or by the team can result in negative feelings about duties and lack of motivation to be high achievers. Consequently, nurses eventually feel exhausted, decreasing work quality. Therefore, a reward system should be introduced to increase employee motivation and loyalty towards their jobs and the hospital and improve their work quality. QNWL can be improved by maximizing the workplace context, through communication, supervision, cooperation, career development, reward, work facilities and work security. Positive relationships among nurses and other hospital staff result in a comfortable work environment and enhance employee motivation. Likewise, effective communication can decrease medical errors, increase patient safety and promote high-quality patient care.

The findings related to development of an empowerment model to prevent burnout syndrome and enhance QNWL (Fig. 2) demonstrated that structural empowerment positively influenced psychological empowerment and QNWL. Psychological empowerment negatively influenced burnout syndrome, which in turn was negatively associated with QNWL. QNWL can be directly improved through structural empowerment.

Fig. 2.

Results of findings on the development of empowerment model for Burnout Syndrome and Quality of Nursing Work Life.

Empowerment is the process of authorizing the autonomy given to nurses to make decisions, solve problems and solve work-related situations [12]. Empowerment enhances the potential and motivation of nurses [25] to adapt, accept their environment and more effectively address the bureaucratic hurdles that hinder their abilities to respond. Empowerment helps ensure that the duties and scope of practice of the nurses are consistent with the goals of the organisation [9]. Organisational processes in a hospital can also be implemented in the presence of a nurse unit manager in the hospital organisational structure. Organisational structure refers to the processes that relationship between duties and authorities, reporting connection, job divisions and organisational coordination system [7]. The function of a nurse unit manager is to give guidance, suggestions, orders or instructions to subordinates in performing their duties [26].

The benefits of nurse empowerment are to nurture staff to think critically, solve problems and develop a leadership attitude, among others. Empowerment promotes leadership, colleagueship, self-respect and professionalism [25]. Empowerment liberates staff from mechanical thinking and encourages problem solving [21]. Staff motivation and autonomy are embedded in empowerment involvement [1], such as developing knowledge and skills through education and training to develop a sense of professional responsibility [27].

Empowerment also includes providing employees with opportunities to use their knowledge, experience and motivation, leading to an assertive work performance [28]. Therefore, empowerment provides the team with the capacity and authority to take actions in solving day-to-day professional problems. Planning is a crucial component of decision making. Thus, formal steps must be undertaken to create staff empowerment at the hospital. To achieve this team goal, the manager must coordinate and communicate with all levels of employees, including the nurse unit manager, team leaders, heads of room nurses and on-duty nurses to increase nurse participation. This function helps employees to adapt with the complex environment. The organisational adaptation process conditions managers and subordinates to continuously evaluate the progress of achieving goals.

4.2. Recommendations

On the basis of the findings of this study (Table 4), the recommendations include the following. (1) Seminars and continuous education must be facilitated, and nurses must be encourage to participate. (2) Continuous communication and information sharing must be implemented among the nurse unit manager, team leaders, heads of room nurses, and on-duty nurses to optimize the supervision activities and nursing care coordination. (3) The presence of role models and offering rewards to room teams are good performance indicators. (4) The management and information system that are integrated into hospital management and patient care electronic documentation system must be improved. (5) The communication and teamwork across disciplines must also be improved to address patient safety (6) Clear job descriptions of the professional nursing care model of the team must be established, and standard routine operating procedures must be implemented. (7) Routine non-nursing activities must be redirected to reduce nurse fatigue and stress. (8) A work environment should that minimises nosocomial infections must be maintained by disciplining visiting hours and providing waiting rooms to visitors. (9) The human resource management unit should review the workplace to ensure that it is in accordance with the safety standards.

4.3. Implication to nursing practice

This study highlighted nursing care mobility opportunities. In other words, opportunities for hospital nurses must be created in accordance with competencies, and the active engagement of nurses in the decision-making to improve QNWL must be encouraged. Empowerment must be created through the support, resources and information of nursing services so that nurses are empowered to think critically, solve problems and develop leadership skills when rendering services. Continuous coordination and communication among nurses at all levels are important. Nurses should be aware of challenges that might affect their performance and be capable of articulating their ideas verbally and in writing.

4.4. Limitations

The limitation of this study includes the small sample size of nurses representing only four units in one particular hospital, which limit the generalizability of the results. Likewise, the response of the subjects in this study were dependent on the respondents' personal feelings and willingness to articulate them openly and honestly. The influence of empowerment, leadership style and customer satisfaction on QNWL needs further research.

5. Conclusions

Structural empowerment using the indicators of resources, support and information directly influenced psychological empowerment. Psychological empowerment in meaning can decrease burnout syndrome. Burnout syndrome with the indicators of personal achievement influenced QNWL. Structural empowerment directly influenced QNWL, especially in the work context. The nurse empowerment model for burnout syndrome and QNWL can directly improve QNWL by providing opportunities in work involvement, rewards, coordination and communication to enable nurses to think critically, solve problems and develop leadership skills.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chinese Nursing Association.

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnss.2018.05.001.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data related to this article:

References

- 1.Greco P., Laschinger H.K.S., Wong C. Leader empowering behaviours, staff nurse empowerment and work engagement/burnout. Nurs Leader. 2006;19:41–56. doi: 10.12927/cjnl.2006.18599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Armstrong M.A. Kogan Page; London: 2006. Handbook of human resources management practice. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Laschinger H., Laschinger H.K.S., Iwasiw C. Nurse educators’ workplace empowerment, burnout, and job satisfaction: testing Kanter’s theory satisfaction: testing Kanter’s theory. J Adv Nurs. 2004:46. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2003.02973.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nursalam N. Salemba Medika; Jakarta: 2016. Metodologi penelitian ilmu keperawatan pendekatan praktis. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matejić B., Milenović M., Kisić Tepavčević D., Simić D., Pekmezović T., Worley J.A. Psychometric properties of the Serbian version of the Maslach Burnout Inventory-Human Services Survey: a validation study among anesthesiologists from belgrade teaching hospitals. Sci World J. 2015:2015. doi: 10.1155/2015/903597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boxall P. Mutuality in the management of human resources: assessing the quality of alignment in employment relationships. Hum Resour Manag J. 2013;23:3–17. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Efendi F., Chen C.-M., Nursalam N., Andriyani N.W.F., Kurniati A., Nancarrow S.A. How to attract health students to remote areas in Indonesia: a discrete choice experiment. Int J Health Plann Manag. 2016;31(4):430–445. doi: 10.1002/hpm.2289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Efendi F., Ken Mackey T., Huang M.-C., Chen C.-M., Mackey T.K., Huang M.-C. IJEPA: gray area for health policy and international nurse migration. Nurs Ethics. 2017 May;24(3):313–328. doi: 10.1177/0969733015602052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fitzpatrick J.J., Montgomery K.S. second ed. Springer Publishing Company; New York: 2003. Internet resources for nurses. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Çavus M.F., Demir Y. The impacts of structural and psychological empowerment on burnout: a research on staff nurses in Turkish state. Can Soc Sci. 2010;6:63. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bawafaa E., Wong C.A., Laschinger H. The influence of resonant leadership on the structural empowerment and job satisfaction of registered nurses. J Res Nurs. 2015;20:610–622. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kirkman B.L., Rosen B. Beyond self-management: antecedents and consequences of team empowerment. Acad Manag J. 1999;42:58–74. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clavelle J.T., O’Grady T.P., Drenkard K. Structural empowerment and the nursing practice environment in Magnet® organizations. J. Nurs. Adm. 2013;43:566–573. doi: 10.1097/01.NNA.0000434512.81997.3f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sarmiento T.P., Laschinger H.K.S., Iwasiw C. Nurse educators’ workplace empowerment, burnout, and job satisfaction: testing Kanter’s theory. J Adv Nurs. 2004;46:134–143. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2003.02973.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cho J., Laschinger H.K.S., Wong C. vol. 19. Nurs Leadership-Academy Can Exec Nurses; 2006. Workplace empowerment, work engagement and organizational commitment of new graduate nurses; p. 43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vecchio R.P., Justin J.E., Pearce C.L. The utility of transactional and transformational leadership for predicting performance and satisfaction within a path-goal theory framework. J Occup Organ Psychol. 2008;81:71–82. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Collette J.E. Retention of nursing staff—a team-based approach. Aust Health Rev. 2004;28:349–356. doi: 10.1071/ah040349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sheel S., Sindhwani B.K., Goel S., Pathak S. Quality of work life, employee performance and career growth opportunities: a literature review. Int. J. Multidiscip. Res. 2012;2:291–300. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Laschinger H.K.S., Finegan J., Shamian J., Wilk P. 2003. Workplace empowerment as a predictor of nurse burnout in restructured healthcare settings; pp. 2–11. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sahoo C.K., Das S. Employee empowerment: a strategy towards workplace commitment. Eur J Bus Manag. 2011;3:46–55. doi:ISSN 2222-1905 (Paper) ISSN 2222-2839 (Online) [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sirin M., Sokmen S.M. Quality of nursing work life scale: the psychometric evaluation of the Turkish version. Int J Caring Sci. 2015;8:543. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spreitzer G.M. Psychological empowerment in workplace: dimensions, measurement, and validation. Acad. Manag. J. 1995;38:5. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maslach, Savicki Victor. Different perspectives on job burnout. Contemp. Psychol. APA Rev. Books. 2004;49(2):168–170. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brooks B.A., Anderson M.A. Nursing work life in acute care. J Nurs Care Qual. 2004;19:269–275. doi: 10.1097/00001786-200407000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Donahue M.O., Piazza I.M., Griffin M.Q., Dykes P.C., Fitzpatrick J.J. vol. 21. 2008. T; pp. 2–7. (he relationship between nurses â€TM perceptions of empowerment and patient satisfaction). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jones R.A.P. FA Davis; Philadelphia: 2007. Nursing leadership and management: theories, processes and practice. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bakker A.B., Leiter M.P. Where to go from here: integration and future research on work engagement. Work Engagem A Handb Essent Theory Res. 2010:181–196. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meng L., Liu Y., Liu H., Hu Y., Yang J., Liu J. Relationships among structural empowerment, psychological empowerment, intent to stay and burnout in nursing field in mainland China-based on a cross-sectional questionnaire research. Int J Nurs Pract. 2015;21:303–312. doi: 10.1111/ijn.12279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.