Abstract

Background and Objectives:

Although potentially dangerous, little is known about ambulatory opioid exposure (OE) in children and youth with special healthcare needs (CYSHCN). We assessed the prevalence and types of OE, and the diagnoses and healthcare encounters proximal to OE in CYSHCN.

Methods:

Retrospective cohort study of 2,597,987 CYSHCN aged 0-to-18 years from 11 states, continuously enrolled in Medicaid in 2016, with ≥1 chronic condition. OE included any filled prescription (single or multiple) for opioids. Healthcare encounters were assessed within 7-days before and 7- and 30-days after OE.

Results:

Among CYSHCN, 7.4% had OE. CYSHCN with vs. without OE were older (e.g., ages 10-to-18 years: 69.4% vs. 47.7%), had more chronic conditions (e.g., ≥3 conditions: 49.1% vs. 30.6%), and had more polypharmacy (e.g., ≥5 other medication classes: 54.7% vs. 31.2%), p<0.001 for all. Most (76.7%) OE were single fills with a median duration of 4 days (IQR 3–6). The most common OEs were acetaminophen-hydrocodone (47.5%), acetaminophen-codeine (21.5%), and oxycodone (9.5%). Emergency department visits preceded 28.8% of OEs, followed by outpatient surgery (28.8%), and outpatient specialty care (19.1%). Most OEs were preceded by a diagnosis of infection (25.9%) or injury (22.3%). Only 35.1% and 62.2% of OEs were associated with follow-up visits within 7- and 30-days, respectively.

Conclusions:

OE in CYSHCN is common, especially with multiple chronic conditions and polypharmacy. Subsequent studies should examine the appropriateness of opioid prescribing, particularly in EDs, as well as to assess for drug interactions with chronic medications, and reasons for insufficient follow-up.

Table of Contents Summary:

This study highlights ambulatory opioid exposures (OE) in children and youth with special healthcare needs, by prevalence and type of OE, diagnoses, and healthcare encounters.

INTRODUCTION

Approximately 3% of U.S. children receive opioid prescriptions in the outpatient setting for the management of acute and chronic pain.1 Opioids can be dangerous to children, as evidenced by the dramatic rise in opioid-related pediatric emergency department (ED) visits and intensive care unit hospitalizations over the past decade.2,3 Much research has focused on opioid use and the risk of subsequent misuse or development of a opioid use disorder.4,5 However, even during the course of proper administration of an opioid prescription, patients may be at increased risk of adverse drug events (ADEs) from direct dug effects or drug-drug interactions.6,7 Children and youth with special healthcare needs (CYSHCN) represent a particularly vulnerable group of children who may be at higher risk for necessary opioid exposures (OEs) and subsequent ADEs, due to their underlying chronic conditions, surgical and procedural-related needs, and to their exposure to polypharmacy with other high-risk drugs.8–12 However, recent large-scale studies of medication or opioid use in children either have not included or have not specifically analyzed CYSHCN.3,6,7

In 2016, the Centers for Disease Control released national guidelines for safer opioid prescribing, but pediatric-specific recommendations were not included.13 Still, pediatric healthcare systems have begun to implement clinical guidelines for opioid prescribing and monitoring, although CYSHCN-specific recommendations are lacking.13–16 Some states have legislated maximum limits for the prescribing of opioids.17 While no universal policy exists, it is generally recommended to 1) dispense a maximum of 3–7 days of opioid pain medications at the time of discharge from an ambulatory clinic, emergency room, or hospitalization, and 2) ensure primary, specialty, or other outpatient follow up within 7-to-30 days for children likely to experience on-going pain.13–16 It is unclear how often these safety practices are implemented during the course of clinical care, especially for CYSHCN.

To ensure the safest possible use of opioids among CYSHCN, it is essential to understand the clinical characteristics of CYSHCN who receive prescription opioids, as well as the types of healthcare utilization preceding and following prescription of an opioid. We thus designed this study to advance knowledge of OE in CYSHCN. Our specific aims were to 1) examine demographic and clinical characteristics of CYSHCN associated with OE; 2) describe the types of opioids prescribed to CYSCHN and the duration of therapy provided; 3) assess the most common diagnoses associated with OE in CYSHCN; and 4) analyze healthcare utilization by CYSHCN in the 7 days preceding OE and at 7 and 30 days following OE.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study Design, Population, and Setting

We performed a retrospective cohort study of CYSHCN using the MarketScan Medicaid Database (IBM Watson Health, Armonk, NY). This database contains claims data from fee-for-service and managed care plans from 11 de-identified states representing all geographic regions of the United States and has been extensively utilized for studies of CYSHCN.18,19 We included children ages 0-to-18 years continuously enrolled in Medicaid (≥11 months) in 2016. Continuous enrollment was chosen for study inclusion because the database does not contain pharmacy claims that could have occurred during enrollment gaps. CYSHCN were defined by the presence of >1 chronic conditions as defined by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) Chronic Condition Indicator (CCI) system.20 The AHRQ CCI system classifies ~68,000 International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) codes as chronic or not chronic and assigns each chronic condition code to 1 of 18 mutually exclusive categories that are largely organized by organ system (e.g., digestive or respiratory).21–24 In the CCI algorithm, a chronic condition is defined as a condition that lasts 12 months or longer and has one or both of the following effects: (a) it places limitations on self-care, independent living, and social interactions; (b) it results in the need for ongoing intervention with medical products, services, and special equipment. Adapted for use in children, the AHRQ CCI system is all-inclusive of childhood chronic conditions across the spectrum of prevalence, severity, and complexity.19,24–26

Definition of Opioid Exposure

For the patient-level analysis, an OE was defined as any filled prescription for an opioid based on the 2-digit generic product indicator (GPI) code for opioids (2-digit GPI = 65). We reported exposures to specific opioids at the level of the generic product name. For the prescription-level analysis, OEs were further classified as single or multiple fill episodes. Single fill episodes consisted of an opioid fill without a refill or a new fill in the subsequent 7 days. Multiple fill episodes consisted of an opioid fill with a refill or a new fill in the subsequent 7 days and could be comprised of several sequential fills. We identified children with multiple fills because they likely indicate ongoing pain and/or prolonged opioid therapy.

Demographics and Clinical Characteristics of CYSHCN With Opioid Exposure

We described demographic characteristics including age, sex, and race/ethnicity. We assessed the type and number of chronic conditions for each child with ICD-10-CM codes using the AHRQ CCI system. To better understand the potential severity of the chronic conditions, we further identified the subset of CYSHCN with complex chronic conditions (CCCs), known to be associated with increased medical complexity (e.g. multiple co-morbidities, technology dependence, polypharmacy), higher morbidity and mortality, and increased resource use.27

Diagnoses Associated with Opioid Exposure

For each opioid fill, we utilized the AHRQ Multi-level Clinical Classification System (CCS) to comprehensively assess all health problems (e.g., injury) that were filed during healthcare encounters across the care continuum (i.e. inpatient or outpatient) during the 7 days preceding OE. The AHRQ CCS system groups related ICD-10-CM codes into mutually-exclusive categories. We determined frequencies of all CCS level 2 diagnoses to determine the most prevalent health problems in the 7 days preceding OE. Of these, we associated OE first to diagnoses with clinical indications for OE (e.g., traumatic injury, malignancy). If there was not a forthcoming clinical indication for OE, we then considered other related diagnoses (e.g., infection, non-traumatic musculoskeletal condition), and lastly the categories of symptoms or descriptions of the healthcare encounter itself (e.g., ill-defined symptoms, signs, and conditions).

Healthcare Utilization Before and After Opioid Exposure

Healthcare utilization across the continuum was assessed using pre-established service categories in the dataset. These categories included primary care, outpatient specialty, home healthcare, emergency department (ED), inpatient (including inpatient surgery), outpatient surgery, dental surgery, and mental health. Overall, and by single versus multiple-fill episodes, we reported healthcare utilization during the 7-days before an opioid fill, and during the 7- and 30-days after an opioid fill.28 In the case of multiple fills, only outcomes surrounding the first fill were considered. Only prescriptions filled between January 8 and December 1 of the calendar year of study were considered for analysis to allow for complete utilization data.

Statistical Analysis:

We used descriptive statistics to describe key characteristics of the study population, including the exposure of CYSHCN to opioids, the exposure by specific chronic condition, and the most common specific chronic medications taken by CYSHCN. Comparisons between categorical variables of interest were conducted using the chi-square test. Statistical significance was set at p<0.001. All analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). This study of de-identified data was exempt from review by the policies of the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board.

RESULTS

Among 4,032,955 continuously enrolled children, 64.4% were CYSHCN. Overall, OE occurred in 3.5% of children without a special healthcare need, 7.4% of CYSHCN, and 14.0% in CYSHCN with a CCC. CYSHCN represented 80.0% of all children who had OE. The 2,597,987 CYSHCN comprised the study population for all subsequent analyses.

Demographics and Clinical Characteristics of CYSHCN With and Without Opioid Exposure

Children with vs. without OE were older (e.g., ages 10-to-18 years: 69.4% vs. 48.7%), more likely female (52.0% vs. 47.7%), non-Hispanic white (55.0% vs. 46.9%), and had more chronic conditions (e.g., ≥3 conditions: 49.1% vs. 30.6%) as well as CCCs (18.8% vs. 9.0%), p<0.001 for all. Children with OEs were also more likely to have filled prescriptions from multiple other medication classes during the study year (e.g., ≥5 additional medication classes: 54.7% vs. 31.2%, p<0.001). Specifically, 6.5% of children with OEs had concomitant prescriptions for an anticonvulsant at some point during the study period, 5.9% for an anxiolytic, and 5.4% a benzodiazepine.

Rates of Opioid Exposure in CYSHCN by Number and Type of Chronic Condition

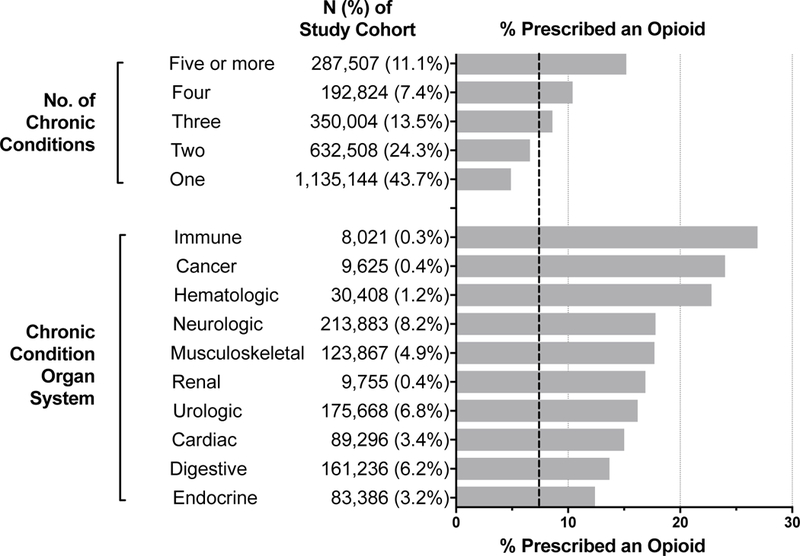

As the number of chronic conditions increased from 1 to 5 or more, the rate of OE increased from 4.9% to 15.2%, p<0.001 (Figure 1). The highest rates of OE were observed in children with immune (26.9%), cancer (24.0%), hematology (22.8%), and neurologic (17.8%) conditions. Specific, common examples of these conditions were hypogammaglobinemia (immune), benign neoplasm of skin (cancer), and sickle cell anemia (hematology), and migraine headaches and cerebral palsy (neurologic). Also, based on the CCC classifications system, OE was high (22.0%) in children assisted with medical technology.

Figure 1. Opioid Prescription by Type and Number of Chronic Conditions Among Children and Youth with Special Healthcare Needs Enrolled in Medicaid.

Each horizontal bar represents the prevalence of opioid exposure within that specific category. For example, of 26.1% of children with an immune chronic condition had an opioid exposure. The vertical dashed reference line (---) represents the overall prevalence of opioid exposure among the study cohort (7%); the prevalence of opioid exposure among all children is ~3%.

Specific Opioids Utilized by CYSHCN

Of the 271,869 opioid prescriptions, 189,040 (76.7%) were dispensed as part of a single-fill episode and the remainder were dispensed as part of 57,542 multiple-fill episodes. Single-fill episodes had a median duration of 4 days (IQR: 3–6 days), and multiple-fill episodes consisted of a median of 2 fills with a total median duration of 10 days (IQR: 7–19 days). Table 2 lists the most commonly filled opioids and the median total days supplied. Acetaminophen-hydrocodone comprised 47.5% of all opioid fills, followed by acetaminophen-codeine (21.5%), oxycodone (9.5%), acetaminophen-oxycodone (9.0%), and tramadol (6.2%).

Table 2.

Opioids Prescribed for Children and Youth with Special Healthcare Needs Enrolled in Medicaid.

| Opioid | Opioid Prescription | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| N | % of Total |

Median (IQR) Days Supplied |

|

| Acetaminophen/Hydrocodone Bitartrate | 129146 | 47.5% | 4 (3, 6) |

| Acetaminophen/Codeine Phosphate | 58414 | 21.5% | 4 (3, 5) |

| Oxycodone Hydrochloride | 25761 | 9.5% | 5 (3, 8) |

| Acetaminophen/Oxycodone Hydrochloride | 24510 | 9.0% | 5 (3, 6) |

| Tramadol Hydrochloride | 16747 | 6.2% | 5 (3, 10) |

| Fentanyl Citrate2 | 10364 | 3.8% | 1 (1, 1) |

| Morphine Sulfate | 2893 | 1.1% | 1 (1, 7) |

| Hydromorphone Hydrochloride | 1438 | 0.5% | 1 (1, 5) |

| Methadone Hydrochloride | 701 | 0.3% | 30 (9, 30) |

| Meperidine Hydrochloride | 496 | 0.2% | 1 (1, 1) |

| Acetaminophen/Tramadol Hydrochloride | 406 | 0.1% | 4 (3, 7) |

| Hydrocodone Bitartrate/Ibuprofen | 386 | 0.1% | 4 (3, 5) |

| Fentanyl Patch | 236 | 0.1% | 30 (18, 30) |

| Acetaminophen/Butalbital/Caffeine/Codeine Phosphate | 153 | 0.1% | 5 (5, 10) |

| Codeine Sulfate | 66 | 0.0% | 5 (3, 8) |

| Tapentadol Hydrochloride | 43 | 0.0% | 30 (10, 30) |

| Aspirin/Butalbital/Caffeine/Codeine Phosphate | 40 | 0.0% | 6 (4, 30) |

| Remifentanil Hydrochloride2 | 22 | 0.0% | 1 (1, 1) |

| Oxymorphone Hydrochloride | 17 | 0.0% | 30 (30, 30) |

| Opium | 11 | 0.0% | 30 (30, 30) |

| Other1 | 19 | 0.0% | N/A |

Other includes (each with N ≤10): sufentanil citrate, hydrocodone bitartrate, alfentanil hydrochloride, belladonna alkaloids/opium alkaloids, aspirin/oxycodone hydrochloride, codeine/dexbrompheniramine/pseudoephedrine, morphine sulfate/naltrexone hydrochloride.

This is an intravenous opioid that may have been administered to a child with peripheral or central vascular access by a home health professional or hospice provider.

Specific Diagnoses and Procedures Associated with OE for CYSHCN

Table 3 lists the top categories of recorded diagnosis codes preceding OE. Those diagnoses most frequently included infections (25.9%), injury (22.3%), non-traumatic musculoskeletal issues (9.6%), dental issues (6.7%), mental health issues (6.6%), gastrointestinal issues (3.7%), non-traumatic neurological issues (1.6%), and malignancy (1.5%). Among specific types of infection, “respiratory infections” comprised the majority (64.1%). There was no diagnosis recorded for 12.9% of CYSHCN with an OE.

Table 3.

Clinical Classification System Diagnosis Groups Coded in 7 days Prior to an Opioid Prescription for Children and Youth with Special Healthcare Needs Enrolled in Medicaid.

| Clinical Classification System Diagnosis Group1 | Opioid Prescription | |

|---|---|---|

| N=183,653 | % of Total |

|

| Infection | 47,530 | 25.9 |

| Injury | 40,916 | 22.3 |

| No diagnosis recorded | 23,694 | 12.9 |

| Non-Traumatic Musculoskeletal Condition | 17,694 | 9.6 |

| Other | 16,872 | 9.2 |

| Dental Condition | 12,293 | 6.7 |

| Mental Health Condition | 12,196 | 6.6 |

| Gastrointestinal Condition | 6,845 | 3.7 |

| Non-Traumatic Neurological Condition | 2,893 | 1.6 |

| Malignancy | 2,720 | 1.5 |

For each opioid fill, we utilized the AHRQ Multi-level Clinical Classification System (CCS) to comprehensively assess all health problems (e.g., diagnoses) that were filed during healthcare encounters across the care continuum (e.g., inpatient or outpatient) during the 7 days preceding OE. The AHRQ CCS system groups related ICD-9-CM codes into mutually-exclusive categories. We determined frequencies of all CCS level 2 diagnoses to determine the most prevalent health problems in the 7 days preceding OE. Of these, we associated OE first to diagnoses with clinical indications for OE (e.g., traumatic injury, malignancy). If there was not a forthcoming clinical indication for OE, we then considered other related diagnoses (e.g., infection, non-traumatic musculoskeletal condition), and lastly the categories of symptoms or descriptions of the healthcare encounter itself (e.g., ill-defined symptoms, signs, and conditions).

Healthcare Utilization Before and After OE for CYSHCN

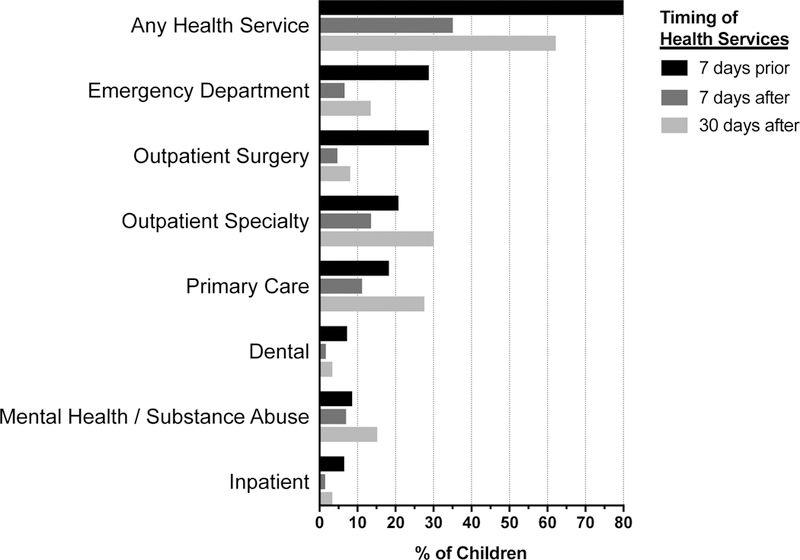

Approximately 86.3% of all OEs were preceded by contact with a healthcare provider (Figure 2). ED visits preceded 28.8% of all exposures, followed by outpatient surgery (28.8%), outpatient specialty (20.8%), primary care (18.3%), dental care (7.3%), and inpatient (6.5%) visits. Of the remaining 13.7% without care in the preceding 7 days, 12.0% had a “not elsewhere specified/injections/durable medical equipment” claim and the rest had no claims at all. Regarding follow-up care, 35.1% of single-fill OEs were associated with a follow-up visit within 7 days and 62.2% within 30 days, with the majority of follow-up visits occurring in the primary care or outpatient subspecialist office settings. Examining multiple-fill episodes only, this rose to 51.6% within 7 days and 74.7% within 30 days.

Figure 2. Health Services Before and After Opioid Prescription for Children and Youth with Special Healthcare Needs Enrolled in Medicaid.

Each horizontal bar represents the percentage of children who utilized that specific type of healthcare service at 7-days prior to opioid exposure (OE), 7-days after OE, and 30-days after OE. For example, of the total 228,019 children with OE, 177,183 (77.7%) utilized any health service 7 days prior to OE, 76,829 (33.7%) utilized any health service 7 days after OE, and 146,051 utilized any health service 30 days after OE.

DISCUSSION

The findings from the current study suggest that CYSHCN in Medicaid may be exposed to opioids at a 2-fold higher rate than the general pediatric population.1 Older, non-Hispanic white children were most likely to have OE compared with children of other race/ethnicities. The highest rates of OE were observed in children with immune, cancer, and hematologic conditions. Moreover, multiple chronic conditions, technology assistance, and polypharmacy were particularly associated with higher rates of OE. Consistent with prior literature, the majority of opioids were prescribed as a single-episode fill and for short durations, although approximately 12% of prescriptions were multiple-fill episodes.29 The types of opioids utilized were consistent with prior studies, with codeine, hydrocodone, and oxycodone representing the majority of prescriptions.30 The most frequent preceding diagnoses were consistent with potential need for opioid therapy (e.g., injury). While >80% of all children had contact with a prescribing provider in the 7 days before OE, far fewer had subsequent follow-up at 7 and 30 days. Several of these findings warrant additional discussion.

First, further investigation is needed to assess the appropriateness of OE in CYSHCN. Many CYSHCN were exposed to opioids by healthcare providers, including ED clinicians and dentists, who – because of their typical role and setting in the healthcare system – may either not have been ideally positioned to achieve strong longitudinal knowledge of the children’s past medical history (i.e., complex chronic conditions, polypharmacy, etc.) or current overall health and well-being, or situated to provide follow-up.31,32 These patient attributes may be particularly important to contemplate when choosing which medication(s) to prescribe for pain in CYSHCN. While certain chronic conditions (e.g. sickle cell anemia) may necessitate opioid therapy33, a number of prescriptions were preceded by diagnoses not synonymous with pain (e.g. respiratory infections). Recent FDA warnings have been issued to minimize OE for acute respiratory infections and to reduce use of specific opioids in children (e.g. codeine).28,34,35 High rates of OE in the current study also occurred in children with complex neuromuscular conditions, such as cerebral palsy. These conditions may make it difficult to quantify and assess pain, especially by healthcare providers lacking clinical familiarity with the child and family. Real-world clinical data is needed to assess the medical decision-making that led to OE in CYSHCN, including which non-opioid medications for pain in CYSHCN were trialed in advance of the exposure.36

Second, the high rates of polypharmacy observed in CYSHCN with OE in the current study merit additional exploration. Emerging evidence suggests that polypharmacy is prevalent among CYSHCN, especially those using Medicaid.37 While opioids themselves can result in dangerous ADEs, including digestive dysmotility, urinary retention, and respiratory depression, they also have the potential for drug-drug interactions with a variety of other medications.16,38 For example, because of the risk for severe respiratory depression, coma, and death when opioids are utilized concomitantly with benzodiazepines, the FDA has issued a black box warning against simultaneous administration of these medications. Despite this warning, some CYSHCN (e.g., those with epilepsy and musculoskeletal spasticity) using benzodiazepines in the current study were also exposed to opioids. Additional study is necessary to assess whether those CYSHCN received prescriptions from multiple outpatient providers (e.g., opioid from a dental or surgical provider and anti-epileptic from a neurologist), potentially without concerted collaboration, decision-making, and monitoring. This practice could lead to concurrent therapy with “contraindicated” drug combinations. Such combinations, like opioids and benzodiazepines, may be clinically necessary, but also require extremely close monitoring to avoid adverse events when utilized simultaneously. Although our study was not designed to look at concurrent medication use, future pediatric polypharmacy studies should investigate simultaneous exposure to opioids and other drugs, particularly to look for signals of downstream consequences.

Finally, less than 50% of children with multiple-fill episodes (indicating ongoing pain) had follow-up within 7 days. Although not assessed in the current study, it is possible that the pain experienced by these children resolved or that based on family or physician preference, follow-up occurred by phone or another communication mode that was not associated with a healthcare claim. However, because long-term opioid use often begins with treatment of acute pain, it is imperative that children who receive multiple fills of opioids are re-evaluated in some manner for ongoing need versus discontinuation.13 In a recent study investigating persistent opioid use following surgery, approximately 5% of opioid-naïve subjects filled additional opioid prescriptions >90 days after surgery, raising concern that acute exposure to opioids for postoperative pain management may be associated with a risk of long-term use.30 When follow up is indicated, improved strategies for ensuring follow-up are warranted.39 Medical homes for CYSHCN may be best positioned to identify patients with prescriptions for new high-alert medications like opioids and then conduct follow-up evaluations either in person, by phone, or via the electronic health record. Centralized electronic prescription drug monitoring programs contain the necessary data to ascertain such patients.40 Follow up evaluations should minimize impact on the families of children with high medical complexity, who may also have medical caregivers in the home who can relay information to the prescribing provider.

Our findings must be interpreted in the context of several limitations. First, our results were based on filled opioid prescriptions. Children may have used only a portion of the filled prescription, which would lead to an overestimation of risk due to opioids. We attempted to address this issue by separately analyzing children with multiple prescription episodes, which would indicate that they were utilizing their dispensed medication. Second, a percentage of prescribing episodes were not preceded by visits with a prescribing provider. This indicates that children may have received opioids from prescriptions made >7 days prior to the fill date or from other modes (e.g. called-in prescription without a healthcare encounter). In either scenario, this raises concern that children might be receiving opioids without timely, in-person assessment of their pain symptoms. Third, because these were administrative claims data, we were not able to determine an individual child’s actual need for opioid pain control. We attempted to report prescription episodes associated with diagnostic codes for conditions indicating likely physical pain (e.g. traumatic injury). For the majority of prescription episodes, however, we were not able to identify the reason(s) for opioid therapy, including their use in palliative and end-of-life care. Fourth, the continuous enrollment attribute of our study population led to under-representation of infants, which could have affected the demographic characteristics of the cohort, as well as the rate and risk factors for OE in CYSHCN. Subsequent analysis of OE in neonates and infants is warranted.

These limitations notwithstanding, we hope that the current study advances knowledge and awareness of outpatient OE in the vulnerable population of CYSHCN. Medical home clinicians for CYSHCN, in particular, may leverage these findings to counsel CYSYCN and their families on the likelihood of OE, especially for children with attributes (e.g., multiple chronic conditions and polypharmacy) associated with higher OE. To ensure the safety of OE in CYSHCN, the development of evidence-based opioid prescribing guidelines is paramount, including best practices for follow-up evaluation. As opioid prescribing guidelines are implemented, it will be important for subsequent studies to assess trends in OE over time for CYSHCN.

CONCLUSION

OE in CYSHCN is common, especially among those with multiple chronic conditions and polypharmacy. The findings may be useful to catalyze subsequent investigations on (1) the appropriateness of opioid use in CYSHCN, especially when prescribed from dental and emergency department settings; (2) opioid interactions with other chronic medications, especially in CYSHCN with polypharmacy; and (3) reasons for insufficient follow-up in CYSHCN prescribed opioids.

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Children and Youth with Special Healthcare Needs Enrolled in Medicaid.

| All Subjects N=2,597,987 |

Opioid Prescription | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| No N=2,406,816 |

Yes N=191,171 |

||

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |

| Demographics | |||

| Age in Years | |||

| <1 | 12989 (0.5) | 12688 (0.5) | 301 (0.2) |

| 1–5 | 635903 (24.5) | 608373 (25.3) | 27530 (14.4) |

| 5–9 | 642644 (24.7) | 612065 (25.4) | 30579 (16.0) |

| 10–12 | 479739 (18.5) | 455761 (18.9) | 23978 (12.5) |

| 13–18 | 826712 (31.8) | 717929 (29.8) | 108783 (56.9) |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 1,350,873 (52.0) | 1259024 (52.3) | 91849 (48.0) |

| Female | 1,247,114 (48.0) | 1147792 (47.7) | 99322 (52.0) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||

| Non-Hispanic White | 1,234,155 (47.5) | 1128993 (46.9) | 105162 (55.0) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 822,472 (31.7) | 770136 (32.0) | 52336 (27.4) |

| Hispanic | 212,695 (8.2) | 201419 (8.4) | 11276 (5.9) |

| Other | 328,665 (12.6) | 306268 (12.7) | 22397 (11.7) |

| Clinical Characteristics | |||

| Complex Chronic Condition | |||

| Yes | 252,994 (9.7) | 217510 (9.0) | 35484 (18.6) |

| Technology Assistance | |||

| Yes | 21,909 (0.8) | 17098 (0.7) | 4811 (2.5) |

| Number of Additional NonOpioid Rx Classes1 Received | |||

| 0 | 449,008 (17.3) | 442260 (18.4) | 6748 (3.5) |

| 1–2 | 720,362 (27.7) | 686918 (28.5) | 33444 (17.5) |

| 3–4 | 605,602 (23.3) | 562965 (23.4) | 42637 (22.3) |

| 5–6 | 395,568 (15.2) | 357961 (14.9) | 37607 (19.7) |

| ≥7 | 427,447 (16.5) | 356712 (14.8) | 70735 (37.0) |

Based on 2-digit generic product indicator (GPI) code, which categorizes major classes of medications.

What’s Known on This Subject:

Ambulatory prescription opioid use in children is associated with harmful consequences, including increasing emergency department visits and critical care hospitalizations. Children and youth with special healthcare needs (CYSHCN) frequently utilize medications, yet little is known about their use of opioids.

What This Study Adds:

Approximately 7% of all CYSHCN and 14% of CYSHCN with a complex chronic condition received ≥1 opioid annually in the ambulatory setting. Only 35% and 62% of opioid exposures were associated with follow-up visits within 7- and 30-days, respectively.

Acknowledgments

Funding Source: Dr. Feinstein was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number K23HD091295. Drs. Berry and Hall and Mr. Rodean by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) under UA6MC31101 Children and Youth with Special Health Care Needs Research Network. Dr. Doupnik was supported by grant K23MH115162 from the National Institute of Mental Health. This information or content and conclusions are those of the author and should not be construed as the official position or policy of, nor should any endorsements be inferred by HRSA, HHS or the U.S. Government.

Abbreviations:

- ADE

Adverse drug event

- AHRQ

Agency for Healthcare Research & Quality

- CCC

Complex chronic condition

- CCI

Chronic condition indicator

- CYSHCN

Children and youth with special healthcare needs

- ED

Emergency Department

- ICD-9-CM

International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification

- OE

Opioid exposure

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: The authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Groenewald CB, Rabbitts JA, Gebert JT, Palermo TM. Trends in opioid prescriptions among children and adolescents in the United States: a nationally representative study from 1996 to 2012. Pain. 2016;157(5):1021–1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kane JM, Colvin JD, Bartlett AH, Hall M. Opioid-Related Critical Care Resource Use in US Children’s Hospitals. Pediatrics. 2018;141(4). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allen JD, Casavant MJ, Spiller HA, Chounthirath T, Hodges NL, Smith GA. Prescription Opioid Exposures Among Children and Adolescents in the United States: 2000–2015. Pediatrics. 2017;139(4). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McCabe SE, West BT, Veliz P, McCabe VV, Stoddard SA, Boyd CJ. Trends in Medical and Nonmedical Use of Prescription Opioids Among US Adolescents: 1976–2015. Pediatrics. 2017;139(4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miech R, Johnston L, O’Malley PM, Keyes KM, Heard K. Prescription Opioids in Adolescence and Future Opioid Misuse. Pediatrics. 2015;136(5):e1169–1177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Qato DM, Alexander GC, Guadamuz JS, Lindau ST. Prescription Medication Use Among Children and Adolescents in the United States. Pediatrics. 2018;142(3). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chung CP, Callahan ST, Cooper WO, et al. Outpatient Opioid Prescriptions for Children and Opioid-Related Adverse Events. Pediatrics. 2018;142(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gmuca S, Xiao R, Weiss PF, Sherry DD, Knight AM, Gerber JS. Opioid Prescribing and Polypharmacy in Children with Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain. Pain Med. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feinstein J, Dai D, Zhong W, Freedman J, Feudtner C. Potential Drug-Drug Interactions in Infant, Child, and Adolescent Patients in Children’s Hospitals. Pediatrics. 2015;135(1):e99–e108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feinstein JA, Feudtner C, Kempe A. Adverse drug event-related emergency department visits associated with complex chronic conditions. Pediatrics. 2014;133(6):e1575–1585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Simon TD, Berry J, Feudtner C, et al. Children with complex chronic conditions in inpatient hospital settings in the United States. Pediatrics. 2010;126(4):647–655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hauer J, Houtrow AJ, Section On H, Palliative Medicine COCWD. , Pain Assessment and Treatment in Children With Significant Impairment of the Central Nervous System. Pediatrics. 2017;139(6). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain - United States, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65(1):1–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nationwide Children’s Hospital. Guidelines for Safe Opioid Prescribing. https://www.nationwidechildrens.org/Document/Get/161423.

- 15.Children’s Hospital Colorado. Opioid Prescribing Practices. https://www.childrenscolorado.org/globalassets/healthcare-professionals/clinical-pathways/opioid-prescribing-practices.pdf.

- 16.Munzing T Physician Guide to Appropriate Opioid Prescribing for Noncancer Pain. Perm J. 2017;21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.State of Colorado. Senate Bill 18–022: Concerning Clinical Practive Measures for Safer Opioid Prescribing. 2018; http://leg.colorado.gov/sites/default/files/documents/2018A/bills/2018a_022_enr.pdf?utm_medium=email&utm_source=govdelivery. Accessed 5/30/18.

- 18.Agrawal R, Hall M, Cohen E, et al. Trends in Health Care Spending for Children in Medicaid With High Resource Use. Pediatrics. 2016;138(4). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berry JG, Rodean J, Hall M, et al. Impact of Chronic Conditions on Emergency Department Visits of Children Using Medicaid. J Pediatr. 2017;182:267–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Berry JG, Toomey SL, Zaslavsky AM, et al. Pediatric readmission prevalence and variability across hospitals. Jama. 2013;309(4):372–380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Friedman B, Jiang HJ, Elixhauser A, Segal A. Hospital inpatient costs for adults with multiple chronic conditions. Med Care Res Rev. 2006;63(3):327–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Chronic Condition Indicator (CCI) for ICD-9-CM 2011; http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/chronic/chronic.jsp.

- 23.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Chronic Condition Indicator. 2012; http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/chronic/chronic.jsp.

- 24.Berry JG, Ash AS, Cohen E, Hasan F, Feudtner C, Hall M. Contributions of Children With Multiple Chronic Conditions to Pediatric Hospitalizations in the United States: A Retrospective Cohort Analysis. Hosp Pediatr. 2017;7(7):365–372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berry JG, Gay JC, Joynt Maddox K, et al. Age trends in 30 day hospital readmissions: US national retrospective analysis. BMJ. 2018;360:k497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Berry JG, Glotzbecker M, Rodean J, Leahy I, Hall M, Ferrari L. Comorbidities and Complications of Spinal Fusion for Scoliosis. Pediatrics. 2017;139(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Feinstein JA, Russell S, DeWitt PE, Feudtner C, Dai D, Bennett TD. R Package for Pediatric Complex Chronic Condition Classification. JAMA pediatrics. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chua KP, Shrime MG, Conti RM. Effect of FDA Investigation on Opioid Prescribing to Children After Tonsillectomy/Adenoidectomy. Pediatrics. 2017;140(6). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Richardson LP, Fan MY, McCarty CA, et al. Trends in the prescription of opioids for adolescents with non-cancer pain. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2011;33(5):423–428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harbaugh CM, Lee JS, Hu HM, et al. Persistent Opioid Use Among Pediatric Patients After Surgery. Pediatrics. 2018;141(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Janakiram C, Chalmers NI, Fontelo P, et al. Sex and race or ethnicity disparities in opioid prescriptions for dental diagnoses among patients receiving Medicaid. J Am Dent Assoc. 2018;149(4):246–255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dana R, Azarpazhooh A, Laghapour N, Suda KJ, Okunseri C. Role of Dentists in Prescribing Opioid Analgesics and Antibiotics: An Overview. Dent Clin North Am. 2018;62(2):279–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ehrentraut JH, Kern KD, Long SA, An AQ, Faughnan LG, Anghelescu DL. Opioid misuse behaviors in adolescents and young adults in a hematology/oncology setting. J Pediatr Psychol. 2014;39(10):1149–1160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.FDA acts to protect kids from serious risks of opioid ingredients contained in some prescription cough and cold products by revising labeling to limit pediatric use [press release]. 2018.

- 35.FDA. FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA requires labeling changes for prescription opioid cough and cold medicines to limit their use to adults 18 years and older. 2018; https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm590435.htm. Accessed 7/12/18.

- 36.McMahon AW, Dal Pan G. Assessing Drug Safety in Children - The Role of Real-World Data. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(23):2155–2157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Feinstein JA, Feudtner C, Valuck RJ, Kempe A. The depth, duration, and degree of outpatient pediatric polypharmacy in Colorado fee-for-service Medicaid patients. Pharmacoepidemiology and drug safety. 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McCance-Katz EF, Sullivan LE, Nallani S. Drug interactions of clinical importance among the opioids, methadone and buprenorphine, and other frequently prescribed medications: a review. Am J Addict. 2010;19(1):4–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Abraham J, Kannampallil T, Caskey RN, Kitsiou S. Emergency Department-Based Care Transitions for Pediatric Patients: A Systematic Review. Pediatrics. 2016;138(2). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.U.s. Department of Justice. State Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs. https://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/faq/rx_monitor.htm.