Abstract

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDA) is a dismal malignant disease with the lowest stagecombined overall survival rate compared to any other cancer type. PDA has a unique tumor microenvironment (TME) comprised of a dense desmoplastic reaction comprising over twothirds of the total tumor volume. The TME is comprised of cellular and acellular components that all orchestrate different signaling mechanisms together to promote tumorigenesis and disease progression. Particularly, the neural portion of the TME has recently been appreciated in PDA progression. Neural remodeling and perineural invasion (PNI), the neoplastic invasion of tumor cells into nerves, are common adverse histological characteristics of PDA associated with a worsened prognosis and increased cancer aggressiveness. The TME undergoes dramatic neural hypertrophy and increase neural density that is associated with many signaling pathways to promote cell invasion. PNI is also considered one of the main routes for cancer recurrence and metastasis after surgical resection, which remains the only current cure for PDA. Recent studies have shown multiple cell types in the TME signal through autocrine and paracrine mechanisms to enhance perineural invasion, pancreatic neural remodeling and disease progression in PDA. This review summarizes the current findings of the signaling mechanisms and cellular and molecular players involved in neural signaling in the TME of PDA.

Keywords: Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, tumor microenvironment, neural remodelling, perineural invasion

I. Introduction

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDA) is a devastating malignant disease with a poor prognosis. The incidence rate continues to rise for pancreatic cancer; while the 5 year stagecombined overall survival rate is lower than any other cancer type at 9% in the United States (Siegel, Miller, & Jemal, 2019). Majority of patients present with advanced or metastatic disease upon diagnosis, while, only about 20% of patients are eligible for the only curative therapy for PDA, surgical resection. Of those who undergo surgical resection, 80% will ultimately relapse and succumb to the disease (Kleeff et al., 2016; Wolfgang et al., 2013). PDA arises from the exocrine cells of the pancreas and constitutes more than 90% of pancreatic neoplasms (Pelosi, Castelli, & Testa, 2017). Common genetic mutations associated with PDA are found in KRAS, TP53, CDKN2A, and SMAD4 genes; however, drug-targeting these mutations has yet to show significant promise (Kleeff et al., 2016; Pelosi et al., 2017).

A major characteristic of PDA is the extremely dense desmoplastic environment, or abundance of extracellular matrix (ECM), that surrounds the PDA cells constituting up to 60–90% of the total tumor volume (Chu, Kimmelman, Hezel, & DePinho, 2007; Maitra & Hruban, 2009). PDA cells induce reconstruction of their surroundings while also stimulating environmental support for disease propagation. The stroma of PDA creates a unique tumor microenvironment (TME) consisting of cellular and acellular components such as fibroblasts, immune cells, blood and lymphatic vessels, extracellular matrix, neurons, and soluble proteins such as cytokines and growth factors. Increasing research has found TME components can work together to promote tumorigenesis and disease progression (M Amit et al., 2017; Biankin et al., 2012; Bressy et al., 2018; X. Li et al., 2014; Pinho et al., 2018; Rucki et al., 2016; Q. Xu et al., 2014).

Of all the components of the TME, the biology behind neuronal signaling is least understood. Yet, several studies highlight the unique importance of neural-PDA cell signaling in pancreatic cancer disease evolution. The neuronal architecture in the pancreas is distorted during PDA development and several neuron-related genes are dysregulated to promote tumorigenesis (Biankin et al., 2012; Ceyhan et al., 2006; Dang, Zhang, Ma, & Shimahara, 2006; Gohring et al., 2014; Müller et al., 2007; Pinho et al., 2018; Saloman et al., 2018). In addition, increased innervation and neural hypertrophy in the TME is common, as well as, tumor cell invasion into the nerves which is associated with significant disease-related pain and a worsened overall prognosis (Moran Amit, Na’Ara, & Gil, 2016; Chatterjee et al., 2012; Saloman et al., 2016; Stopczynski et al., 2014). Since targeting neoplastic cells of PDA has been difficult and shown little promise, superior understanding of neuronal signaling with tumor cells and other components of the TME is essential for the development of new therapeutics and better drug infiltration and sensitivity into the dense pancreatic TME.

II. Neural and Tumor Cell Signaling Interactions

The normal pancreas is innervated by sympathetic nerve fibers derived from the splanchnic nerves and sensory nerve fibers from the dorsal root ganglion (DRG) and vagus nerve (Ihsan Ekin Demir, Friess, & Ceyhan, 2015). In pancreatic cancer, normal neural architecture of the pancreas transforms to become hyperinnervated with substantial neural hypertrophy (Moran Amit et al., 2016; Ihsan Ekin Demir et al., 2015; Jobling et al., 2015; Stopczynski et al., 2014). In addition, perineural invasion (PNI) is a common histological feature of PDA. PNI is defined as the neoplastic invasion of the nerve by surrounding tumor cells and/or invading into the spaces of the epineurium, perineurium, or endoneurium (Liang et al., 2016; Liebig, Ayala, Wilks, Berger, & Albo, 2009). PNI is common in several cancer types, but has the highest incidence in PDA at 80–100% and is an indicator of aggressive tumor behavior and poor prognosis (Bapat, Hostetter, Von Hoff, & Han, 2011; Liang et al., 2016; Nakao, Harada, Nonami, Kaneko, & Takagi, 1996; Shimada et al., 2011; Yan-Hui Yang, Liu, Gui, Lei, & Zhang, 2017). Patients with PNI have an overall survival of two years shorter than patients without PNI (Chatterjee et al., 2012). PNI can occur without vascular or lymphatic invasion, and is thought to represent the initial steps of metastasis (Chang, Kim-Fuchs, Le, Hollande, & Sloan, 2015; Liebig et al., 2009). Moreover, the grade of intrapancreatic neural innervation can be correlated to the extrapancreatic invasion observed. Patients with extrapancreatic nerve plexus invasion had significantly lower survival rates than patients without extrapancreatic nerve plexus invasion at the time of surgical resection. All patients that survived more than 3 years after surgical resection exhibited no extrapancreatic nerve invasion at the time of surgery, while portal vein wall invasion was observed in some cases, indicating that neural invasion was more predictive of poor prognosis (Nakao et al., 1996).

Several studies indicate the nervous system participates in all stages of PDAC development. Using a KPC mouse model of PDA, with mutant Kras and loss of p53 expression in the pancreas, Stopczynski et al. found that as early as 6–8 weeks of age hyperinnervation was found in the pancreas of KPC mice, implying that early changes in the microenvironment impact the pancreatic neuron innervation. Furthermore, the KPC mice had increased expression of neurotrophic factor genes in DRG cells such as neural growth factor (NGF), tropomyosin receptor kinase B (TRKB), neurturin (Nrtn), and GDNF family receptor alpha 2 (Gfrα2). This increase in DRG neurotropic factor genes was seen before an overt tumor was formed (Stopczynski et al., 2014). Moreover, another study found sensory neuron ablation by neonatal capsaicin injection prevented PNI, delayed PanIN formation and prolonged survival in a murine autochthonous model of PDA (Saloman et al., 2016). In addition, peripheral nerve supporting cells, Schwann cells have been detected around murine and human pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasias, indicating supportive neural cells also migrate towards pancreatic cancer cells at the early stages of disease progression. The presence of Schwann cells during premalignant stages of disease was significantly associated with the frequency of neural invasion during the malignant phase (Demir et al., 2014).

Studies have also shown secreted proteins from PDA cells encourage neural remodeling. Myenteric plexus and DRG cultures treated with supernant from several PDA cell lines led to significantly increased neurite outgrowth, neuronal network formation and increased somatic hypertrophy. Moreover, PDA tissue extract treatment increased complex neuronal branching capacity in myenteric plexus and DRG neurons (Demir et al., 2010). Several of these secreted signaling factors have been further investigated to understand the biological changes underlying these phenotypic changes in neural outgrowth, innervation and PNI.

Axon guidance molecules have been implicated to directly communicate between PDA and neural cells. The axon guidance gene family was found to be the most frequently altered gene family in PDA, including mutations and copy number changes, demonstrated from whole exome sequencing of human samples (Biankin et al., 2012). Axon guidance molecules were originally described for controlling growth, navigation and position of neurons; however, several axon guidance proteins are misregulated in PDA to promote tumorigenesis (Foley et al., 2015; Müller et al., 2007; Yong et al., 2016). Slit guidance ligand 2 (SLIT2) has been defined as a repellent guidance cue to impact neural and endothelial remodeling (Gohring et al., 2014). The SLIT2 receptors, ROBO1 and ROBO3 (H. Li et al., 1999) are found on nerves and PDA epithelial cells. Interestingly, SLIT2 mRNA expression is decreased in PDA cells compared to normal pancreas cells. Restoration of SLIT2 in tumor cells was shown to inhibit bidirectional chemoattraction of PDA cells to nerves and inhibit PDA cell motility. Restoration of SLIT2 expression in the pancreas decreased invasion and metastasis of PDA cells in a xenograft orthotopic model of PDA. Moreover, clinical specimens expressing low SLIT2 were significantly associated with higher amounts and fractions of lymph node invasion (Gohring et al., 2014).

Multiple semaphorins (Sema) and plexins, other members of the axon guidance family of proteins, have been found to be overexpressed in the TME during tumorigenesis and shown to aid disease progression and metastasis, such as Sema3A, Sema3C, Sema3D, Sema3E, PlexinA1, and PlexinD1, (Foley et al., 2015; Müller et al., 2007; X. Xu et al., 2017; Yong et al., 2016). High Sema3A and PlexinA1 expression in human PDA was associated with reduced patient survival (Müller et al., 2007). In addition, Sema3A, Sema3E, Sema3D, PlexinA2, and PlexinD1 have been found upregulated in murine PDA samples compared to normal pancreas tissue indicating a role for axon guidance molecules in disease progression (Biankin et al., 2012; Foley et al., 2015). Sema3A and its receptors neuropilin-1 (Nrp1) and PlexinA1 have also been found to accumulate in the neural and malignant areas in the TME to increase PDA cell invasiveness (Müller et al., 2007). Sema3C expression was found to be positively associated with PDA tumor stage and inversely associated with survival. Expression of Sema3C increased PDA cell proliferation, invasion and epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT) of PDA cells through activation of the ERK½ signaling pathway (X. Xu et al., 2017). We reported Semaphorin 3D (Sema3D) secretion and expression to be upregulated during PDA development. Increased Sema3D expression was found to be associated with poor survival and metastasis in human PDA (Foley et al., 2015). We found Sema3D secretion to be regulated by phosphorylation of Annexin A2, a phospholipid binding protein involved in exocytosis (Foley et al., 2015; Zheng et al., 2011). Secreted Sema3D acts in an autocrine manner to increase PDA invasion and metastasis through binding of its co-receptors, PlexinD1 and Nrp1 (Foley et al., 2015). Recently our lab has found paracrine signaling of Sema3D and PlexinD1 between tumor and neurons to mediate increased innervation, perineural invasion and metastasis in PDA (Jurcak et al., submitted for publication). A comprehensive analysis of axon guidance gene expression is lacking and would provide insightful information on the synergistic functions of these proteins in regulating PNI and neural remodeling.

Neural Growth Factor (NGF) has also been implicated in neural-tumor signaling. NGF is a member of the neurotrophin family of proteins found to aid in the growth, survival and differentiation of peripheral neurons. PDA tumor cells overexpress NGF suggesting a paracrine signaling interaction between peripheral nerves and PDA cells. NGF upregulation by tumor cells has been associated with a worsened prognosis, increased perineural invasion and pain (Dang et al., 2006; Zhu et al., 1999). In addition, the high affinity receptor for NGF, tyrosine kinase receptor A (TRKA), has been significantly associated with PNI in human tissue compared to tissue without PNI. NGF promotes tumor growth while also inhibiting tumor and neuronal cell apoptosis (Ma, Jiang, Jiang, Sun, & Zhao, 2008). Anti-NGF treatment in KPC mice starting at 8 weeks of age was found to decrease expression of genes involved with neural invasion and nociception, such as TRKA, NGF receptor, tachykinin precursor-1, and calbindin-1 in neural DRG cells. Moreover, anti-NGF treatment induced a reduction in migratory PDA cells found in the thoracic spinal cord, reduced PNI and inhibited metastases formation (Saloman et al., 2018).

There is also accumulating evidence that activation of the peripheral sympathetic nervous system (SNS) through β-adrenergic receptor signaling influences PDA progression. Catecholamines, epinephrine and norepinephrine (NE), are secreted from sympathetic nerves and bind to α- and β NE in the TME (Hisatomi, Maruyama, Orci, Vasko, & Unger, 1985- adrenergic receptors to elicit cellular effects. NE is present in the TME and has been found to stimulate PDA cell growth and invasion through tumoral upregulation of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) MMP-2, MMP-9 expression. MMPs are enzymes capable of degrading components of the ECM to prompt PDA cell invasion and TME remodeling (Guo et al., 2009; Qian et al., 2018). Moreover, Qian et al., found NE enhances cell viability, invasion, and inhibition of apoptosis in a Notch-1 dependent manner (Qian et al., 2018). Not only are catecholamines produced by tumor cells, but intrapancreatic neurons also secrete NE (Renz et al., 2018); and stress-induced signaling from nerves is thought to play a role in PDA development. Physiological activation of the SNS leads to NE release into the pancreas from the post-ganglionic nerve fiber, creating a surplus of NE in the TME (Hisatomi, Maruyama, Orci, Vasko, & Unger, 1985). The β2-adrenergic receptor has been found to be a mediator of stress-induced cancers. β-adrenergic receptor agonist treatment increased PDA tumorigenesis while, a bilateral adrenalectomy was shown to reduce tumor incidence in a murine Kras-driven model of PDA (Renz et al., 2018). In addition, a nonselective selective β-blocker treatment has been found to decrease primary tumor growth, reduce PDA cell dissociation and prolong survival (Kim-Fuchs et al., 2014; Renz et al., 2018). -blocker treatment has been found to decrease primary tumor growth, reduce PDA cell dissociation and prolong survival (Kim-Fuchs et al., 2014; Renz et al., 2018). NE had also been shown to promote PNI. NE treatment of PDA cells increased tumoral STAT3 phosphorylation in a NE dose-dependent manner; and, treatment with a STAT3 inhibitor reduced the NE-dependent increased neural invasion and PDA cell migration (Guo et al., 2013). Moreover, chronic restraint stress can activate β-adrenergic receptor signaling of the SNS. Chronic restraint stress placed on tumor bearing mice increased circulating catecholamine levels. Chronic restraint stress caused expansion of tumoral intrapancreatic nerves; which was blocked with β2-adrenergic receptor antagonist treatment and subsequently also prolonged survival (Renz et al., 2018). Stromal macrophages, fibroblasts and endothelial cells also express β-adrenergic receptors indicating a possible paracrine signaling route between not only nerves and PDA cells but other components of the TME as well (Chang et al., 2015).

Other neurotrophic factors have been investigated in neural signaling of the TME. Midkine (MK), is a neurotropic factor shown to be involved in neurite outgrowth, neuronal survival, and tumorigenesis in PDA. MK was found to be expressed by tumor cells in patients with perineural invasion, while, its receptor syndecan-3, was found primarily expressed on the perineurium of pancreatic nerves, but absent in tumor cells. MK expression levels were higher in patients with PNI compared to patients without, suggesting a role for MK and syndecan-3 in PNI of PDA. (Yao, Li, Li, Feng, & Gao, 2014). Artemin is another neurotrophic factor that belongs to the GDNF family of ligands binding to GFRα3. Expression of Artemin and GFRα3 was found to be enhanced in PDA compared to the normal pancreas, particularly in primary and metastatic PDA cells and hypertrophic nerves; in addition, Artemin was also found to promote PDA cell invasion (Ceyhan et al., 2006).

Membrane anchored proteins have also been implicated in direct neural-tumoral interactions in the TME. Mucin-4 (MUC4), a membrane anchored glycoprotein, was also suggested to be involved in chemoattraction and enhancing neural invasion in PDA. MUC4 is overexpressed in PDA compared to normal pancreas tissue and even further increased in human tumors with neural invasion. MUC4 was found to regulate netrin-1 expression through the HER2/AKT/NF-kB pathway to increase tumor cell migration towards nerves and neurite outgrowth towards tumor cells (Wang et al., 2015). Another study found overexpression of L1 cell adhesion molecule (L1CAM) in PDA cells and adjacent Schwann cells, peripheral nerve supporting cells, in invaded nerves. Schwann cells were found to express L1CAM to act as a chemoattractant to PDA cells through MAP kinase signaling upregulation and induce PDA upregulation of MMP-2 and MMP-9 through STAT3 activation (Na, Ziv, & Gil, 2018). Furthermore, anti-L1CAM antibody treatment in a transgenic KPC mouse model of PDA demonstrated significantly reduced neural invasion, providing evidence that neural supporting cells can signal in a paracrine manner to promote PDA invasion (Na et al., 2018). In addition, CX3CL1, a transmembrane chemokine is expressed by neurons and nerve fibers in PDA; while, its receptor CX3CR1 is upregulated in neoplastic cells compared to the normal pancreas ducts (Marchesi et al., 2008). CX3CR1-positive PDA cells migrated in response to CX3CL1 to specifically adhere to neural CX3CL1+ cells through activation of G proteins, β1 integrins and focal adhesion kinase. In addition, positive immunohistochemical staining of CX3CR1 in PDA tissue was significantly associated with perineural invasion (Marchesi et al., 2008).

PDA cells can also induce neuronal plasticity. Immunohistochemical analysis of intrapancreatic nerves invading PDA tissue had upregulated levels of secretogranin II and neurosecretory protein VGF compared to nerves not invading PDA tissue (Alrawashdeh et al., 2019). Also, there are several neuropeptides that play a role in pain generation, a common symptom for PDA patients, such as calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) and substance P. Activation of transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily V (TRPV1) in neurons induces CGRP and substance P secretion that prompts pain in neurons of the DRG and the pancreas (Warzecha et al., 2001). Overall, these neural to PDA cell signaling changes in the TME prompt TME remodeling to promote disease progression and PDA metastasis.

III. Fibroblast and Tumor Signaling Interactions

Cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) use several mechanisms to directly or indirectly act on PDA cells and nerve cells to influence disease progression (Ahrens, Bhagat, Nagrath, Maitra, & Verma, 2017; Bressy et al., 2018; Sun et al., 2018; Xiao et al., 2016). In the pancreas under normal conditions, fibroblasts are distributed throughout connective tissue, ducts, blood vessels and pancreatic lobules in relatively low abundance. However, in PDA, CAFs emerge as part of the immunosuppressive TME due to paracrine signaling originating from PDA cells and function to enhance tumor cell growth, invasion, and metastasis (Hwang et al., 2008; Shan et al., 2017). CAFs derive from activation of resident fibroblasts and pancreatic stellate cells, transformation of cancer cells into fibroblast-like cells through EMT and differentiation of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (Feig, Gopinathan, et al., 2013; Sun et al., 2018; Zhang, Crawford, & Pasca di Magliano, 2018). Pancreatic stellate cells (PSCs), which express α-smooth muscle actin, comprise the largest subset of CAFs in the TME and are the main source of the desmoplastic extracellular matrix responsible for the characteristic fibrotic and hypovascular environment. CAFs are a heterogeneous cell population and can be subdivided into two categories: inflammatory fibroblasts, which express low levels of α-smooth muscle actin and high levels of tumor promoting cytokines and chemokines, and myofibroblasts, which express higher levels of α-smooth muscle actin and are located immediately adjacent to neoplastic cells (Sun et al., 2018).

Tumor cell activation of CAFs is essential for downstream signaling of CAFs to neuronal cells. During tumorigenesis, PDA cells secrete various growth factors and cytokines such as transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β), platelet derived growth factor, and fibroblast growth factor to recruit and activate fibroblasts (Sun et al., 2018). Interestingly, the axon guidance gene, Nrp-1, is expressed on fibroblasts and can bind TGF-β to increase Smad2/3 phosphorylation promoting an activated myofibroblast phenotype in fibroblasts, known to promote tumorigenesis (Cao et al., 2010; Sun et al., 2018). After activation, CAFs secrete copious elements contributing to the desmoplastic ECM found in the TME including, collagen, fibronectin, tenascin C (TnC), and MMPs (Sun et al., 2018). It has also been revealed that CAFs can signal to PDA cells to enhance tumor development and progression. An initial study highlighting the importance of CAFs in promoting tumorigenesis tested the effect of human PSC conditioned medium on PDA cells. A dose dependent increase in proliferation, migration and invasion was found in PDA cells after human PSC conditioned medium treatment suggesting a paracrine signaling axis between PSCs and PDA tumor cells (Hwang et al., 2008).

Several CAF-PDA cell paracrine signaling pathways have been revealed to be important for primary tumor growth, metastases formation, and increasing PDA cell invasion. Sonic Hedgehog (SHH) signaling ligands were found overexpressed in PDA tumor cells; while, downstream SHH signaling is restricted to the stromal component allowing for paracrine signaling between stromal and neoplastic cells (Scales & Sauvage, 2009). Moreover, SHH ligands expressed by PDA cells, such as smoothened, have been shown to facilitates CAF expansion. (Walter et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2018) SHH ligands induced CAF cell expression and secretion of insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1), which is reduced upon SHH inhibition (Rucki et al., 2016). Moreover, SHH signaling produced from PDA tumor cells has been found to induce TnC secretion in mesenchymal stem cells. TnC produced by stromal cells acts back on PDA tumor cells through its receptor, Annexin A2, to induce PDA cell invasion by stimulating focal adhesion and actin stress fiber disassembly and to induce apoptotic resistance through ERK/NF-κB signaling (Chung & Erickson, 1994; Foley, Muth, Jaffee, & Zheng, 2017).

Furthermore, studies revealed CAF-PDA cell signaling induces the epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT) of PDA cells, which is shown to enhance neural invasion. EMT involves the loss of cell-to-cell connections and polarity and transformation of epithelial cells into migratory mesenchymal cells that promotes cell invasion and increased perineural invasion (Kalluri & Weinberg, 2009). Wu et al., found that pancreatic stellate cells expressed greater mRNA levels of IL-6, compared to PDA cells which in turn expressed higher levels of the IL-6 receptor. IL-6 is an inflammatory cytokine found to be involved in PDA proliferation, migration and angiogenesis (Wu et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2013). IL-6 secreted by PSCs, induced JAK/STAT3 and nuclear factor erythroid 2 signaling in PDA cells to increase migration and increase expression of EMT-related genes such as, N-cadherin, fibronectin, Twist2, Snail, and Slug (Wu et al., 2017). G-protein coupled receptor 68 was also found to regulate IL-6 production in PDA CAF cells in a cAMP-PKA-CREB dependent manner (Wiley et al., 2018). In addition, a lectin family protein, Galectin-1 (GAL1) was shown to increase the EMT of PDA cells. Gal-1 is strongly expressed by activated PSCs and PSC GAL1 expression positively correlated with vimentin, a mesenchymal cell marker, while it negatively correlated with E-cadherin, an epithelial cell marker. Secreted GAL1 from PSCs binds to PDA cells to promote NF-κB dependent activation of EMT, as well as, increase growth and metastasis of PDA cells (Tang et al., 2017). Moreover, GAL3 has also been discovered to be secreted by PDA cells to signal in a paracrine manner on CAF cells. GAL3 stimulates increased activation and proliferation in CAFs inducing NF-κB-dependent increased CAF expression of inflammatory cytokines IL-8, GM-CSF, CXCL-1 and CCL-2. Furthermore, a GAL3 inhibitor was shown to reduce growth and metastases of orthotopic pancreatic tumors in mice. (Zhao et al., 2018). It would be interesting to study the if tumor invasion towards nerve is also impacted by these galectin proteins.

CAFs have also been shown to express several proteins that are involved in neural remodeling and perineural invasion. Supernant from human PSCs stimulated a stronger neurite outgrowth in myenteric plexus and DRG neurons than supernant from PDA cells; and induced a higher neurite density in DRG cells, indicating the significance of proteins secreted by PSCs (Demir et al., 2010). TGF-β treated PSCs have been shown to increase protein expression of NGF and both its receptors TRKA and p75NTR through the ALK-5 signal transduction pathway (Haas et al., 2009). In addition, fibroblast activation protein (FAP) positive CAF cells, but not PDA cells, were established to secrete CXCL12, which could then act in a paracrine manner to bind the receptor CXCR4, inducing PDA cell proliferation. CXCL12 has also been shown to induce NGF expression in PDA cells; and, subsequently increase PDA cell migration to nerves ( Xu et al., 2014). Interestingly, exogenous CXCL12 treatment on DRG cells has been shown to induce neurite outgrowth. Moreover, CXCL12 can also be derived from peripheral nerves to stimulate PDA cell invasion and metastasis through upregulation of MMP-2 and MMP-9 (Feig, Jones, et al., 2013; Shen et al., 2013; Q. Xu et al., 2014). A comprehensive analysis of multiple proteins secreted from CAFs and their impact of neural remodeling is warranted.

CAFs undergo metabolic changes compared to normal pancreatic fibroblasts to aid PDA function. CAFs consume more glucose compared to normal pancreatic fibroblasts allowing increased production of secreted lactate. Excess lactate in the TME is actively taken up by tumor cells to aid their growth (Shan et al., 2017). In addition, PSCs use autophagy to secrete alanine which is also taken up by PDA cells to outcompete glucose and glutamine-derived carbon to fuel the TCA cycle (Sousa et al., 2016); providing another example of how PSCs can promote tumor survival in the harsh hypoxic TME environment. Interestingly, PNI has been associated with PDA cells utilizing upregulated levels of autophagy (Yan-Hui Yang et al., 2017).

IV. Suppressive Immune Cell and Tumor Signaling Interactions

There are several immunosuppressive cell types in the PDA TME including tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), regulatory T cells, and tolerogenic dendritic cells. In this review, we will focus on TAMs and MDSCs, as they have also been found to be important in neural signaling in the TME. TAMs and MDSCs play a critical role in immunosuppression in the TME and continuously communicate with PDA cells to propagate disease progression.

Myeloid cells originate from hematopoietic stem cells in the bone marrow and are continuously replenishing all tissues through the circulation. These cells include monocytes, granulocytes, macrophages, dendritic cells, and mast cells. Once monocytes arrive at various tissue they further mature into macrophages that may have unique tissue-specific functions and morphologies (Kawamoto & Minato, 2004). TAMs aid tumor progression and have been associated with a worsened overall prognosis (Hu et al., 2016; Kurahara et al., 2011).

PDA cells can influence TAM polarization. Studies have shown that lactate, secreted by cancer cells can polarize macrophages to a more tumor promoting phenotype (Feng et al., 2018; Mu et al., 2018). Lactate elevates reactive oxygen species (ROS) in macrophages to induce nuclear factor erythroid 2 mediated VEGF expression, which has been found to stimulate EMT markers in PDA cells, increasing the PDA cells ability for neural invasion (Feng et al., 2018).

The exact role of macrophages in neural plasticity and perineural invasion in PDA is not fully understood and warrants further investigation; however, a few studies have found TAMs to be linked to neural invasion. Immunohistochemical staining of human PDA tissue found that a greater TAM density was found in PDA tumors with PNI compared to tumors without PNI and was associated with a worse prognosis (Sugimoto et al., 2014; Zeng et al., 2014). Furthermore, an in vivo model of cancer perineural invasion, CCR2− deficient mice, with reduced macrophage recruitment and activation, had reduced nerve invasion compared to wild-type mice which developed complete sciatic nerve paralysis due to cancer invasion (Cavel et al., 2012). In addition, TAMs can secrete macrophage inflammatory protein-3α which interact in a paracrine manner with CCR6, a G-protein-linked receptor, on PDA tumor cells to promote tumor cell migration and invasion through PDA upregulation of MMP-9, a type 4-collagenase known to be involved in neural invasion (Campbell, Albo, Kimsey, White, & Wang, 2005; Kimsey, Campbell, Albo, & Wang, 2004; Na et al., 2018). Moreover, PDA cells overexpress Sema3A, which has been found to upregulate macrophage migration and VEGF expression (Meda et al., 2012). Macrophages are attracted to hypoxia areas through Sema3A signaling via Nrp1/PlexinA1 or A4 and become transactivated through Nrp1-dependent and Nrp1-independent VEGFR1 transactivation. This subsequently downregulates TAM Nrp1 expression, stopping their migration. Nrp1 deficiency in TAMs reduces their localization to hypoxia niches and favors an antitumor response (Casazza et al., 2013).

Myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSC)s are also an important immunosuppressive cell type in the TME. MDSCs are a heterogeneous population of early myeloid progenitors including monocytic (M-MDSC) and granulocytic (G-MDSC) subsets that can expand during tumorigenesis and encourage immunosuppression. Myeloid cells infiltrate the pancreas during PanIN formation, persist throughout invasive cancer, and are associated with poor survival (Clark et al., 2007; Ruffell & Coussens, 2015). Depletion of myeloid cells have been shown to prevent tumorigenesis Tumor cell have been found to produce several cytokines and growth factors to foster MDSC generation and expansion including GM-CSF, GCSF, IL-6, CXCL1 and CXCL2 (Marigo et al., 2010; Shi et al., 2018) Moreover, MDSCs can also secrete growth factors that act on PDA cells such as epidermal growth factor (EGF) ligand, that induces EGF receptor/MAPK signaling activation in PDA cells (Zhang et al., 2017).

Colony-stimulating factor-1 (CSF-1) is overexpressed by PDA cells and it’s receptor, CSF1R, has been associated with worse overall prognosis (Candido et al., 2018). CSF-1 and CSF-1R regulate the function, migration and survival of macrophages and myeloid cells (Ries et al., 2014). Inhibition of CSF-1R has led to TAM depletion and an increased anti-tumor phenotype of myeloid cells (Saung et al., 2018). CSF-1R was also found to be important for neural signaling as treatment with a CSF-1R antagonist reduced PNI in a mouse model of PDA (Amit et al., 2017).

Moreover, immunosuppressive cells in the TME have been associated with PDA-associated pain. One study found that cytotoxic T lymphocytes, macrophages and mast cells all infiltrate nerves in pancreatic cancer, yet only perineural mast cell were uniquely increased in intrapancreatic nerves in PDA patients with neuropathic abdominal pain (Ihsan Ekin Demir et al., 2013).

V. Multiple TME Components Enhance Neural Signaling Interactions

Several signaling interactions in the TME are directly between stromal cells and PDA cells; however, multiple signaling pathways converge to impact TME neural remodeling, perineural invasion, and disease progression in PDA.

Studies have also shown that PDA cells signal together with CAFs to promote neural invasion in the TME. Activation of PSCs by SHH signaling from paracrine PDA cells induced high secretion of PNI-associated molecules in activated PSCs such as MMP-2, MMP-9, and NGF to promote PNI in an in vitro 3D model of nerve invasion. Furthermore, co-implantation of activated PSCs with PDA cells increased xenograft perineural invasion, suggesting that activated PSCs might also play a role in stimulating PNI in pancreatic cancer (X. Li et al., 2014). Axon guidance protein, ROBO2, was found to be a strong stromal suppressor gene. During initial inflammation of the pancreas, ROBO2 was found to be downregulated in PDA cells leading to paracrine TGF-β-mediated activation of pancreatic myofibroblasts, which in turn induced secretion of proteins involved in increasing neural remodeling (Bressy et al., 2018; Pinho et al., 2018).

In addition, upregulation of pain associated genes was discovered in co-cultures with PDA cells, PSCs and nerves. Interestingly co-culture of PDA cells with PSCs and DRG cells caused DRG cells to increase expression of TRPV1 and secretion of pain factors such as substance P and CGRP more than any monoculture with DRG cells. Mechanistically, SHH secreted by PDA cells induced PSC overexpression of NGF and brain-derived neurotropic factor (BDNF). Secreted NGF from PSCs potentiated TRPV1 current in DRGs to aggravate pain behaviors. Anti-NGF treatment was found to suppress TRPV1, substance P and CGRP, as well as, reduce pain in mouse PDA model (Han et al., 2016).

In addition, Leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF) has also been recently reported to be involved in neural remodeling in PDA. LIF was found to be overexpressed in the PDA TME, particularly in tumor and stromal cells, however, it is absent in normal pancreas tissue. Meanwhile, the two common receptors for LIF, LIF receptor and GP130 were found expressed on intratumoral nerves. The study found CAFs to be the main source of secreted LIF and CAF secretion of LIF was increased upon coculture with macrophages. Secreted LIF induced neural plasticity, increased neurite outgrowth and increased neural soma areas in PDA. This study provides evidence of macrophage and CAF signaling to increase CAF secretion of LIF to promote neural remodeling in the TME of PDA. Further research is necessary to understand how macrophages can increase LIF secretion by CAFs. Moreover, human serum LIF titer positively correlated with increased intratumoral nerve number suggesting LIF as a possible biomarker and diagnostic tool of PDA progression (Bressy et al., 2018).

Another study found CAFs and neural supporting cells, Schwann cells, can signal to enhance neural remodeling. Expression of the axon guidance gene SLIT2, was found to be reduced in PDA neoplastic cells to enhance tumor growth (Gohring et al., 2014), yet it was also found to be increased in expression in CAFs. SLIT2 produced by CAFs enabled neural remodeling by binding to ROBO receptors on Schwann cells inhibiting N-cadherin-mediated adhesion and subsequent β-catenin induced migration and proliferation (Secq et al., 2015). Since high SLIT2 expression by tumor cells was found to decrease tumor chemoattraction to nerves, this role of SLIT2 produced by CAFs acting on Schwann cells to increase neural remodeling, highlights the importance of fully distinguishing different cell-to-cell interactions that modulate the overall spatial tumor biology (Gohring et al., 2014; Secq et al., 2015). Further delineation of this this signaling pathway will help identify the overall role of SLIT2 in disease progression.

In addition, neural tissue resident macrophages have been discovered to aid in PDA cell invasion towards nerves. Immunohistochemical analysis of PDA tissue demonstrated an increased number of endoneurial macrophages present near nerves invaded with cancer cells compared to normal nerves. The study revealed invading PDA cells secreted CSF-1 to recruit endoneurial macrophages. In turn, glial-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) secreted from tumor activated endoneurial macrophages induced a 5-fold increase in tumor cell migration (Cavel et al., 2012). In addition, Schwann cells in nerves with perineural invasion can secrete CCL2 to induce the recruitment of CCR2-positive inflammatory monocytes to accumulate near tumor-invaded nerves, where they are then differentiated into macrophages. Once differentiated, the macrophages produce cathepsin B to promote PNI (Bakst et al., 2018). Furthermore, Ret proto-oncogene (RET) expression was shown to be upregulated by tumors during PDA tumorigenesis and its activation induced PNI. Bone-marrow derived macrophages expressing the RET ligand, GDNF, were found to be highly abundant around cancer invaded nerves. Inhibiting macrophage recruitment with a CSF-1R antagonist, deletion of GDNF expression from perineural macrophages and inhibition of RET all reduced PNI in KPC mouse model of PDA (Amit et al., 2017).

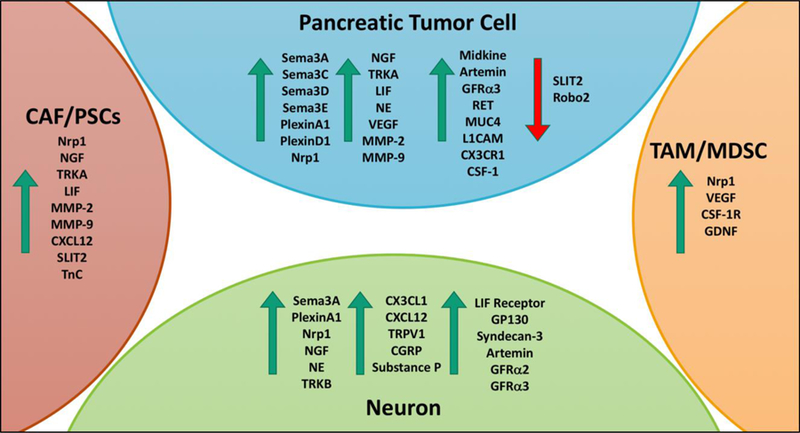

Overall, these studies highlight the multi-cellular signaling pathways involved in regulating neural remodeling and neural invasion in PDA (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Signaling interactions impacting neural architecture and PNI in PDA.

There are several complex paracrine signaling interactions that lead to the dramatic changes in neural architecture during PDA development and progression. Tumor cells reciprocally signal with neurons, CAF/PSCs, and TAM/MDSCs through axon guidance, cytokine and NGF signaling to promote changes in ECM remodeling. In addition, tumor cells and neurons utilize catecholamine signaling in the TME. Comprehensively, these signaling pathways increase the TME capability for neuron remodeling, neuron outgrowth, perineural invasion and tumor growth and metastasis in PDA. Abbreviations: ECM-Extracellular matrix, CAF-Cancer-associated fibroblast, PSC-Pancreatic Stellate Cell, NGF-Neural growth factor, TAM-Tumor-associated macrophage, and MDSC-Myeloid derived suppressor cell.

VI. Discussion

Despite innumerable efforts, PDA remains one of the most malignant human diseases and is the fourth leading cause of cancer death (Siegel et al., 2019). PDA is a very complex disease involving several other cellular components other than neoplastic cells which lead to disease progression. In addition, drug targeting neoplastic cells in PDA has shown little promise, suggesting enhanced understanding of the tumor supportive TME is necessary for novel functioning therapeutics. The neural component in the PDA TME should not be overlooked, as it has been linked with an increased aggressive and metastatic tumor phenotype. Neural signaling changes occur early in PDA development and contribute to desmoplasia and pancreatic cancer associated pain. PNI is also linked to a worse prognosis, an increase in patient pain and decreased survival. Moreover, changes in neural-associated proteins have been found to be the family of proteins most frequently altered in PDA tumorigenesis (Biankin et al., 2012). This review summarizes the cellular and molecular signaling components involved in PDA neural invasion, neural remodeling, PDA-associated pain, disease progression and metastasis (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Major molecular players involved in neural signaling in the TME.

During PDA tumorigenesis and disease progression the expression of several molecular factors is dysregulated. This figure highlights some of the major molecular players that have been identified in increasing PDA cell invasion, perineural invasion and neuron remodeling in the cell types of the PDA TME. The green arrows indicate molecular player that have increased expression in PDA and the red arrow indicates molecular players with decreased expression in PDA.

A major contributor to the dismal prognosis of PDA is the lack of effective treatments for preventing and controlling metastasis. Focusing on the molecular pathways involved in perineural invasion and neural remodeling, targets pathways intrinsic to PDA cells invasion and metastasis; therefore, better understanding tumor cells ability to invade nerves will inherently highlight mechanisms crucial for stopping PDA cell growth, invasion and metastasis. In this review, not just PDA cells but CAFs, TAMs, and MDSCs are all described in attributing to neural remodeling and perineural invasion in PDA through a variety of paracrine signaling mechanisms (Figure 1). Tumor cells upregulate several neuron related molecules during tumorigenesis. PDA cells, neurons, CAFs/PSCs, and TAMs/MDSCs can use molecules involved in axon guidance, cytokine and NGF signaling to upregulate molecules involved in ECM remodeling. In addition, PDA cells and neurons also use catecholamine signaling to promote disease progression. These changes in TME signaling allow for increased neural remodeling, neural outgrowth, perineural invasion and tumor growth and metastasis. Moreover, there are several complex changes in expression that allow for unique paracrine communication between different cell types in the TME (Figure 2). As our understanding of the complex TME evolves, researchers are better equipped to create and study therapeutics that may have significant clinical benefit in not only overall patient survival, but in PDA associated symptoms such as PDA-related pain.

Acknowledgments

This study is supported by funding from the Pancreatic Cancer Precision Medicine Center of Excellence Program at Johns Hopkins including the funding from the Johns Hopkins in Health Program and the Commonwealth Foundation. L.Z. was supported in part by NIH grant R01 CA169702, NIH grant R01 CA197296, the Viragh Foundation and the Skip Viragh Pancreatic Cancer Center at Johns Hopkins, the National Cancer Institute Specialized Programs of Research Excellence in Gastrointestinal Cancers grant P50 CA062924, the Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center grant P30 CA006973, and a Sol Goldman Pancreatic Cancer Research Center grant.

Abbreviations:

- CAFs

Cancer-associated fibroblasts

- CGRP

Calcitonin gene-related peptide

- CSF-1

Colony-stimulating factor-1

- CX3CL1

C-X3-C motif chemokine ligand 1

- CX3CR1

C-X3-C motif chemokine receptor 1

- DRG

Dorsal root ganglion

- ECM

Extracellular matrix

- EMT

Epithelial to mesenchymal transition

- GAL

Galectin

- GDNF

Glial-derived neurotrophic factor

- GFRα

GDNF family receptor alpha

- IGF-1

Insulin-like growth factor 1

- L1CAM

L1 cell adhesion molecule

- LIF

Leukemia inhibitory factor

- MDSCs

Myeloid-derived suppressor cells

- MK

Midkine

- MMPs

Matrix metalloproteinases

- MUC4

Mucin-4

- NE

Norepinephrine

- NGF

Neural growth factor

- Nrp-1

Neuropilin-1

- PDA

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

- PNI

Perineural Invasion

- PSCs

Pancreatic stellate cells

- SEMA

Semaphorin

- SHH

Sonic hedgehog

- SLIT2

Slit guidance ligand 2

- SNS

Sympathetic nervous system

- SP

Substance P

- TAMs

Tumor-associated macrophages

- TGF-β

Transforming growth factor beta

- TME

Tumor microenvironment

- TnC

Tenascin C

- TRKA

Tyrosine kinase receptor A

- TRPV1

Transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily V member 1

- VEGF

Vascular endothelial growth factor

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest:

The authors have no relevant conflict of interests to disclose.

Written Assurance:

This manuscript has not been published and is not under consideration for publication elsewhere.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ahrens D Von Bhagat TD, Nagrath D, Maitra A, & Verma A (2017). The role of stromal cancer-associated fibroblasts in pancreatic cancer. Journal of Hematology & Oncology, 10(76), 1–8. doi: 10.1186/s13045-017-0448-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alrawashdeh W, Jones R, Dumartin L, Radon TP, Cutillas PR, Feakins RM, … Crnogorac‐Jurcevic T (2019). Perineural invasion in pancreatic cancer: proteomic analysis and in vitromodelling. Molecular Oncology, 10.1002/1878-0261.12463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Amit M, Na’Ara S, & Gil Z (2016). Mechanisms of cancer dissemination along nerves. Nature Reviews Cancer, 16(6), 399–408. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amit M, Na S, Binenbaum Y, Kulish N, Fridman E, Shabtai-Orbach A, … Gil Z (2017). Upregulation of RET induces perineurial invasion of pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Oncogene, 36(23), 3232–3239. doi: 10.1038/onc.2016.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakst RL, Xiong H, Chen C, Deborde S, Lyubchik A, Zhou Y, … Wong RJ (2018). Inflammatory monocytes promote perineural invasion via CCL2-mediated recruitment and cathepsin B expression. Cancer Research, 77(22), 6400–6414. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN17-1612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bapat AA, Hostetter G, Von Hoff DD, & Han H (2011). Perineural invasion and associated pain in pancreatic cancer. Nature Reviews Cancer, 11(10), 695–707. doi: 10.1038/nrc3131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biankin AV, Waddell N, Kassahn KS, Gingras M, Muthuswamy LB, Johns AL, … Grimmond SM (2012). Pancreatic cancer genomes reveal aberrations in axon guidance pathway genes. Nature, 491(7424), 399–405. doi: 10.1038/nature11547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bressy C, Lac S, Nigri JE, Leca J, Roques J, Lavaut MN, … Tomasini R (2018). LIF drives neural remodeling in pancreatic cancer and offers a new candidate biomarker. Cancer Research, 78(4), 909–921. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-2790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell AS, Albo D, Kimsey TF, White SL, & Wang TN (2005). Macrophage inflammatory Protein-3 alpha promotes pancreatic cancer cell invasion. Journal of Surgical Research, 123, 96–101. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2004.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Candido JB, Morton JP, Bailey P, Campbell AD, Karim SA, Jamieson T, … Sansom OJ (2018). CSF1R+ macrophages sustain pancreatic tumor growth through T cell suppression and maintenance of key gene programs that define the squamous subtype. Cell Reports, 23(5), 1448–1460. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.03.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Y, Szabolcs A, Dutta SK, Yaqoob U, Jagavelu K, Wang L, … Mukhopadhyay D (2010). Neuropilin-1 mediates divergent R-Smad signaling and the myofibroblast phenotype. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 285(41), 31840–31848. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.151696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casazza A, Laoui D, Wenes M, Rizzolio S, Bassani N, Mambretti M, … Mazzone M (2013). Impeding macrophage entry into hypoxic tumor areas by Sema3A/Nrp1 signaling blockade inhibits angiogenesis and restores antitumor immunity. Cancer Cell, 24(6), 695–709. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavel O, Shomron O, Shabtay A, Vital J, Trejo-leider L, Weizman N, … Gil Z (2012). Endoneurial macrophages induce perineural invasion of pancreatic cancer cells by secretion of GDNF and activation of RET tyrosine kinase receptor. Cancer Research, 72(22), 5733–5743. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-0764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceyhan GO, Giese NA, Erkan M, Kerscher AG, Wente MN, Giese T, … Friess H (2006). The neurotrophic factor artemin promotes pancreatic cancer invasion. Annals of Surgery, 244(2), 274–281. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000217642.68697.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang A, Kim-Fuchs C, Le C, Hollande F, & Sloan E (2015). Neural regulation of pancreatic cancer: A novel target for intervention. Cancers, 7(3), 1292–1312. doi: 10.3390/cancers7030838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee D, Katz MH, Rashid A, Wang H, Iuga AC, Varadhachary GR, … Wang H (2012). Perineural and intraneural invasion in posttherapy pancreaticoduodenectomy specimens predicts poor prognosis in patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. The American Journal of Surgical Pathology, 36(3), 409–417. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31824104c5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu GC, Kimmelman AC, Hezel AF, & DePinho RA (2007). Stromal biology of pancreatic cancer. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry, 101(4), 887–907. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung CY, & Erickson HP (1994). Cell surface Annexin II is a high affinity receptor for the alternatively spliced segment of Tenascin-C. The Journal of Cell Biology, 126(2), 539–548. doi: 10.1083/jcb.126.2.539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark CE, Hingorani SR, Mick R, Combs C, Tuveson DA, & Vonderheide RH (2007). Dynamics of the immune reaction to pancreatic cancer from inception to invasion. Cancer Research, 67(19), 9518–9527. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang C, Zhang Y, Ma Q, & Shimahara Y (2006). Expression of nerve growth factor receptors is correlated with progression and prognosis of human pancreatic cancer. Gastroenterology, 21(5), 850–858. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.04074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demir IE, Boldis A, Pfitzinger PL, Teller S, Brunner E, Klose N, … Ceyhan GO (2014). Investigation of Schwann cells at neoplastic cell sites before the onset of cancer invasion. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 106(8). doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demir IE, Ceyhan GO, Rauch U, Altintas B, Klotz M, Müller MW, … Schäfer K (2010). The microenvironment in chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer induces neuronal plasticity. Neurogastroenterology & Motility, 22(480), e113. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2009.01428.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demir IE, Friess H, & Ceyhan GO (2015). Neural plasticity in pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 12(11), 649–659. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2015.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demir IE, Schorn S, Schremmer-Danninger E, Wang K, Kehl T, Giese NA, … Ceyhan GO (2013). Perineural mast cells are specifically enriched in pancreatic neuritis and neuropathic pain in pancreatic cancer and chronic pancreatitis. PLoS ONE, 8(3), e60529. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feig C, Gopinathan A, Neesse A, Chan DS, Cook N, & Tuveson DA (2013). The pancreas cancer microenvironment. Clin Cancer Res, 18(16), 4266–4276. doi: 10.1158/10780432.CCR-11-3114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feig C, Jones JO, Kraman M, Wells RJB, Deonarine A, Chan DS, … Fearon DT (2013). Targeting CXCL12 from FAP-expressing carcinoma-associated fibroblasts synergizes with anti–PD-L1 immunotherapy in pancreatic cancer. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 110(50), 20212–20217. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1320318110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng R, Morine Y, Ikemoto T, Imura S, Iwahashi S, Saito Y, & Shimada M (2018). Nrf2 activation drive macrophages polarization and cancer cell epithelial- mesenchymal transition during interaction. Cell Communication and Signaling, 16(54), 1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12964-018-0262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foley K, Muth S, Jaffee E, & Zheng L (2017). Hedgehog signaling stimulates Tenascin C to promote invasion of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma cells through Annexin A2. Cell Adhesion & Migration, 11(5), 514–523. doi: 10.1080/19336918.2016.1259057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foley K, Rucki AA, Xiao Q, Zhou D, Leubner A, Mo G, … Zheng L (2015). Semaphorin 3D autocrine signaling mediates the metastatic role of annexin A2 in pancreatic cancer. Science Signaling, 8(388), ra77. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aaa5823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gohring A, Detjen KM, Hilfenhaus G, Korner JL, Welzel M, Arsenic R, … Fischer C (2014). Axon guidance factor SLIT2 inhibits neural invasion and metastasis in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Research, 74(5), 1529–1540. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo K, Ma Q, Li J, Wang Z, Shan T, Li W, … Xie K (2013). Interaction of the sympathetic nerve with pancreatic cancer cells promotes perineural invasion through the activation of STAT3 signaling. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics, 12(March), 264–273. doi: 10.1158/15357163.MCT-12-0809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo K, Ma Q, Wang L, Hu H, Li J, Zhang D, & Zhang M (2009). Norepinephrine-induced invasion by pancreatic cancer cells is inhibited by propranolol. Oncology Reports, 22(4), 825–830. doi: 10.3892/or_00000505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas SL, Fitzner B, Jaster R, Wiercinska E, Gaitantzi H, Jesenowski R, … Breitkopf K (2009). Transforming growth factor-β induces nerve growth factor expression in pancreatic stellate cells by activation of the ALK-5 pathway. Growth Factors, 27(9), 289–299. doi: 10.1080/08977190903132273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han L, Ma J, Duan W, Zhang L, Yu S, Xu Q, … Ma Z (2016). Pancreatic stellate cells contribute pancreatic cancer pain via activation of sHH signaling pathway. Oncotarget, 7(14), 18146–18158. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hisatomi A, Maruyama H, Orci L, Vasko M, & Unger RH (1985). Adrenergically mediated intrapancreatic control of the glucagon response to glucopenia in the isolated rat pancreas. Journal of Clinical Investigation, 75(2), 420–426. doi: 10.1172/JCI111716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu H, Hang J, Han T, Zhuo M, Jiao F, & Wang L-W (2016). The M2 phenotype of tumor-associated macrophages in the stroma confers a poor prognosis in pancreatic cancer. Tumor Biology, 37(7), 8657–8664. doi: 10.1007/s13277-015-4741-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang RF, Moore T, Arumugam T, Ramachandran V, Amos KD, Rivera A, … Logsdon CD (2008). Cancer-associated stromal fibroblasts promote pancreatic tumor progression. Clinical Research, 68(3), 918–927. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jobling P, Pundavela J, Oliveira SMR, Roselli S, Walker MM, & Hondermarck H (2015). Nerve-cancer cell cross-talk: A novel promoter of tumor progression. Cancer Research, 75(9), 1777–1781. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-3180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalluri R, & Weinberg RA (2009). The basics of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. The Journal of Clinical Investigation, 119(6), 1420–1428. doi: 10.1172/JCI39104.1420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawamoto H, & Minato N (2004). Myeloid cells. The International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology, 36, 1374–1379. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2004.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim-Fuchs C, Le CP, Pimentel MA, Shackleford D, Ferrari D, Angst E, … Sloan EK (2014). Chronic stress accelerates pancreatic cancer growth and invasion: A critical role for beta-adrenergic signaling in the pancreatic microenvironment. Brain, Behavior and Immunity, 40, 40–47. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2014.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimsey TF, Campbell AS, Albo D, & Wang TN (2004). Co-localization of macrophage inflammatory protein-3 alpha (Mip-3alpha) and its receptor, CCR6, promotes pancreatic cancer cell invasion. The Cancer Journal, 10(6), 374–380. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2004.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleeff J, Korc M, Apte M, Vecchia C. La, Johnson CD, Biankin AV, … Neoptolemos JP (2016). Pancreatic cancer. Nature Review Disease Primers, 2, 16022. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2016.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurahara H, Shinchi H, Mataki Y, Maemura K, Noma H, Kubo F, … Takao S (2011). Significance of M2-polarized tumor-associated macrophage in pancreatic cancer. Journal of Surgical Research, 167(2), e211–e219. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2009.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Chen J, Wu W, Fagaly T, Zhou L, Yuan W, … Rao Y (1999). Vertebrate slit, a secreted ligand for the transmembrane protein roundabout, is a repellent for olfactory bulb axons. Cell, 96(6), 807–818. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80591-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Wang Z, Ma Q, Xu Q, Liu H, Duan W, … Xie K (2014). Sonic hedgehog paracrine signaling activates stromal cells to promote perineural invasion in pancreatic cancer. Clinical Cancer Research, 20(16), 4326–4338. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-3426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang D, Shi S, Xu J, Zhang B, Qin Y, Ji S, … Yu X (2016). New insights into perineural invasion of pancreatic cancer: More than pain. BBA - Reviews on Cancer, 1865(2), 111–122. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2016.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liebig C, Ayala G, Wilks JA, Berger DH, & Albo D (2009). Perineural invasion in cancer: A review of the literature. Cancer, 115(15), 3379–3391. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma J, Jiang Y, Jiang Y, Sun Y, & Zhao X (2008). Expression of nerve growth factor and tyrosine kinase receptor A and correlation with perineural invasion in. Gastroenterology, 23(12), 1852–1859. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2008.05579.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maitra A, & Hruban RH (2009). Pancreatic Cancer. Annual Review of Pathology, 3, 157–188. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathmechdis.3.121806.154305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchesi F, Piemonti L, Fedele G, Destro A, Roncalli M, Albarello L, … Allavena P (2008). The chemokine receptor CX3CR1 is involved in the neural tropism and malignant behavior of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Research, 68(21), 9060–9070. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marigo I, Bosio E, Solito S, Mesa C, Fernandez A, Dolcetti L, … Bronte V (2010). Tumor-induced tolerance and immune suppression depend on the C/EBPbeta transcription factor. Immunity, 32(6), 790–802. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meda C, Molla F, Pizzol M De Regano D, Maione F, Capano S, … Giraudo E (2012). Semaphorin 4A exerts a proangiogenic effect by enhancing vascular endothelial growth factor-A expression in macrophages. The Journal of Immunology, 188, 4081–4092. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1101435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mu X, Shi W, Xu Y, Xu C, Zhao T, Geng B, … You Q (2018). Tumor-derived lactate induces M2 macrophage polarization via the activation of the ERK/STAT3 signaling pathway in breast cancer. Cell Cycle, 17(4), 428–438. doi: 10.1080/15384101.2018.1444305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller MW, Giese NA, Swiercz JM, Ceyhan GO, Esposito I, Hinz U, … Friess H (2007). Association of axon guidance factor Semaphorin 3A with poor outcome in pancreatic cancer. International Journal of Cancer, 121(11), 2421–2433. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Na S, Ziv A, & Gil Z (2018). L1CAM induces perineural invasion of pancreas cancer cells by upregulation of metalloproteinase expression. Oncogene, 38(4), 596–608. doi: 10.1038/s41388-018-0458-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakao A, Harada A, Nonami T, Kaneko T, & Takagi H (1996). Clinical significance of carcinoma invasion of the extrapancreatic nerve plexus in pancreatic cancer. Pancreas, 12(4), 357–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelosi E, Castelli G, & Testa U (2017). Pancreatic cancer: Molecular characterization, clonal evolution and cancer stem cells. Biomedicines, 5(4), 65. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines5040065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinho AV, Bulck M Van Chantrill L, Arshi M, Sklyarova T, Herrmann D, … Rooman I (2018). ROBO2 is a stroma suppressor gene in the pancreas and acts via TGF-β signalling. Nature Communications, 9(1). doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-07497-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian W, Lv S, Li J, Chen K, Jiang Z, Cheng L, … Duan W (2018). Norepinephrine enhances cell viability and invasion, and inhibits apoptosis of pancreatic cancer cells in a Notch‑1‑dependent manner. Oncology Reports, 40(5), 3015–3023. doi: 10.3892/or.2018.6696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renz BW, Takahashi R, Tanaka T, Macchini M, Hayakawa Y, Dantes Z, … Wang T (2018). β2 adrenergic-neurotrophin feed-forward loop promotes pancreatic cancer. Cancer Cell, 33(1), 75–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2017.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ries CH, Cannarile MA, Hoves S, Benz J, Wartha K, Runza V, … Ruttinger D (2014). Targeting tumor-associated macrophages with anti-CSF-1R antibody reveals a strategy for cancer therapy. Cancer Cell, 25(6), 846–859. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rucki AA, Foley K, Zhang P, Xiao Q, Kleponis J, Wu AA, … Zheng L (2016). Heterogeneous stromal signaling within the tumor microenvironment controls the metastasis of pancreatic cancer. Cancer Research, 77(1), 41–52. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-1383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruffell B, & Coussens LM (2015). Macrophages and therapeutic resistance in cancer. Cancer Cell, 27(4), 462–472. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saloman JL, Albers KM, Li D, Hartman DJ, Crawford HC, Muha EA, … Davis BM (2016). Ablation of sensory neurons in a genetic model of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma slows initiation and progression of cancer. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 113(11), 3078–3083. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1512603113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saloman JL, Singhi AD, Hartman DJ, Normolle DP, Albers KM, & Davis BM (2018). Systemic depletion of nerve growth factor inhibits disease progression in a genetically engineered model of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Pancreas, 47(7), 856–863. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0000000000001090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saung MT, Muth S, Ding D, Thomas DL II, Blair AB, Tsujikawa T, … Zheng L (2018). Targeting myeloid-inflamed tumor with anti-CSF-1R antibody expands CD137 + effector Tcells in the murine model of pancreatic cancer. Journal for ImmunoTherapy of Cancer, 6(1), 118. doi: 10.1186/s40425-018-0435-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scales SJ, & Sauvage F. J. De. (2009). Mechanisms of Hedgehog pathway activation in cancer and implications for therapy. Trends in Pharamcological Sciences, 30(6), 303–312. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2009.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Secq V, Leca J, Bressy C, Guillaumond F, Skrobuk P, Nigri J, … Tomasini R (2015). Stromal SLIT2 impacts on pancreatic cancer-associated neural remodeling. Cell Death and Disease, 6(1), e1592–11. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2014.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shan T, Chen S, Chen X, Lin WR, Li W, Ma J, … Kang Y (2017). Cancer-associated fibroblasts enhance pancreatic cancer cell invasion by remodeling the metabolic conversion mechanism. Oncology Repots, 37(4), 1971–1979. doi: 10.3892/or.2017.5479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen B, Zheng M, Lu J, Jiang Q, Wang T, & Huang X-E (2013). CXCL12-CXCR4 promotes proliferation and invasion of pancreatic cancer cells. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention, 14, 5403–5408. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2013.14.9.5403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi H, Han X, Sun Y, Shang C, Wei M, Ba X, & Zeng X (2018). Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 1 and CXCL2 produced by tumor promote the generation of monocytic myeloidderived suppressor cells. Cancer Science, 109(12), 3826–3839. doi: 10.1111/cas.13809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimada K, Nara S, Esaki M, Sakamoto Y, Kosuge T, & Hiraoka N (2011). Intrapancreatic nerve invasion as a predictor for recurrence after pancreaticoduodenectomy in patients with invasive ductal carcinoma of the pancreas. Pancreas, 40(3), 464–468. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e31820b5d37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, & Jemal A (2019). Cancer Statistics, 2019. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 69(1), 7–34. doi: 10.3322/caac.21551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sousa CM, Biancur DE, Wang X, Halbrook CJ, Sherman MH, Zhang L, … Kimmelman AC (2016). Pancreatic stellate cells support tumour metabolism through autophagic alanine secretion. Nature, 536, 479–483. doi: 10.1038/nature19084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stopczynski RE, Normolle DP, Hartman DJ, Ying H, Deberry JJ, Bielefeldt K, … Davis BM (2014). Neuroplastic changes occur early in the development of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Research, 74(6), 1718–1727. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-132050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugimoto M, Mitsunaga S, Yoshikawa K, Kato Y, Gotohda N, Takahashi S, … Kaneko H (2014). Prognostic impact of M2 macrophages at neural invasion in patients with invasive ductal carcinoma of the pancreas. European Journal of Cancer, 50(11), 1900–1908. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2014.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Q, Zhang B, Hu Q, Qin Y, Xu W, Liu W, … Xu J (2018). The impact of cancerassociated fibroblasts on major hallmarks of pancreatic cancer. Theranostics, 8(18), 5072–5087. doi: 10.7150/thno.26546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang D, Zhang J, Yuan Z, Zhang H, Chong Y, Huang Y, … Wang D (2017). PSC-derived Galectin-1 inducing epithelial-mesenchymal transition of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma cells by activating the NF-κB pathway. Oncotarget, 8(49), 86488–86502. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.21212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walter K, Omura N, Hong S, Griffith M, Vincent A, Borges M, & Goggins M (2010). Overexpression of Smoothened activates the Sonic Hedgehog signaling pathway in pancreatic cancer associated fibroblasts. Clinical Research, 16(6), 1781–1789. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Zhi X, Zhu Y, Zhang Q, Wang W, Li Z, … Xu Z (2015). MUC4-promoted neural invasion is mediated by the axon guidance factor netrin-1 in PDAC. Oncotarget, 6(32), 33805–33822. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.5668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warzecha Z, Dembinski A, Ceranowicz P, Stachura J, Tomaszewska R, & Konturek SJ (2001). Effect of sensory nerves and CGRP on the development of caerulein-induced pancreatitis and pancreatic recovery. Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology, 52(4.1), 679–704. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5085(00)83779-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiley SZ, Sriram K, Liang W, Chang SE, French R, Mccann T, … Insel PA (2018). GPR68, a proton-sensing GPCR, mediates interaction of cancer-associated fibroblasts and cancer cells. The FASEB Journal, 32(3), 1170–1183. doi: 10.1096/fj.201700834R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfgang CL, Herman JJM, Laheru DA, Klein AP, Erdek MA, Fishman EK, & Hruban RH (2013). Recent progress in pancreatic cancer. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 63(5), 318–348. doi: 10.3322/caac.21190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu YS, Chung I, Wong WF, Masamune A, Sim MS, & Looi CY (2017). Paracrine IL-6 signaling mediates the effects of pancreatic stellate cells on epithelial-mesenchymal transition via Stat3 / Nrf2 pathway in pancreatic cancer cells. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta, 1861(2), 296–306. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2016.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao Q, Zhou D, Rucki AA, Williams J, Zhou J, Mo G, … Zheng L (2016). Cancerassociated fibroblasts in pancreatic cancer are reprogrammed by tumor-induced alterations in genomic DNA methylation. Cancer Research, 76(18), 5395–5404. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-3264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Q, Wang Z, Chen X, Duan W, Lei J, Zong L, … Ma Q (2014). Stromal-derived factor-1α/CXCL12-CXCR4 chemotactic pathway promotes perineural invasion in pancreatic cancer. Oncotarget, 6(7), 4717–4731. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X, Zhao Z, Guo S, Li J, Liu S, You Y, … Bie P (2017). Increased semaphorin 3c expression promotes tumor growth and metastasis in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma by activating the ERK½ signaling pathway. Cancer Letters, 397, 12–22. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2017.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Yan-Hui, Liu J-B, Gui Y, Lei L-L, & Zhang S-J (2017). Relationship between autophagy and perineural invasion, clinicopathological features, and prognosis in pancreatic cancer. World Journal of Gastroenterology, 23(40), 7232–7241. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i40.7232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao J, Li W, Li S, Feng X-S, & Gao S-G (2014). Midkine promotes perineural invasion in human pancreatic cancer. World Journal of Gastroenterology, 20(11), 3018–3024. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i11.3018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yong L-K, Lai S, Liang Z, Poteet E, Chen F, van Buren G, … Yao Q (2016). Overexpression of Semaphorin-3E enhances pancreatic cancer cell growth and associates with poor patient survival. Oncotarget, 7(52), 87431–87448. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.13704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng L, Guo Y, Liang J, Chen S, Peng P, Zhang Q, … Huang K (2014). Perineural invasion and TAMs in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas: Review of the original pathology reports using immunohistochemical enhancement and relationships with clinicopathological features. Journal of Cancer, 5(9), 754–760. doi: 10.7150/jca.10238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Crawford HC, & Pasca di Magliano M (2018). Epithelial-stromal interactions in pancreatic cancer. Annual Review of Physiology, 1–23. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol020518-114515. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Zhang Y, Velez-Delgado A, Mathew E, Li D, Mendez FM, Flannagan K, … Pasca di Magliano M (2017). Myeloid cells are required for PD-1 / PD-L1 checkpoint activation and the establishment of an immunosuppressive environment in pancreatic cancer. Gut, 66, 124–136. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-312078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Yan W, Collins MA, Bednar F, Rakshit S, Zetter BR, … Pasca di Magliano M (2013). Interleukin-6 Is required for pancreatic cancer progression by promoting MAPK signaling activation and oxidative stress resistance. Tumor and Stem Cell Biology, 73(20), 6359–6375. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-1558-T. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao W, Ajani JA, Sushovan G, Ochi N, Hwang R, Hafley M, … Song S (2018). Galectin-3 mediates tumor cell–stroma interactions by activating pancreatic stellate cells to produce cytokines via integrin signaling. Gastroenterology, 154(5), 1524–1537. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng L, Foley K, Huang L, Leubner A, Mo G, Olino K, … Jaffee EM (2011). Tyrosine 23 phosphorylation-dependent cell-surface localization of annexin A2 is required for invasion and metastases of pancreatic cancer. PLoS ONE, 6(4), e19390. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu BZ, Friess H, DiMola FF, Zimmermann A, Graber HU, Korc M, & Buchler MW (1999). Nerve growth factor expression correlates with perineural invasion and pain in human pancreatic cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 17(8), 2419–2428. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.8.2419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]