Abstract

Background:

Oral therapies are increasingly common in oncology care. However, data are lacking regarding the physical and psychologic symptoms patients experience, or how these factors relate to medication adherence and quality of life (QoL).

Materials and Methods:

From December 2014 through August 2016, a total of 181 adult patients who were prescribed oral targeted therapy or chemotherapy enrolled in a randomized study of adherence and symptom management at Massachusetts General Hospital Cancer Center. Patients completed baseline assessments of adherence with electronic pill cap, QoL, symptom severity, mood, social support, fatigue, and satisfaction with clinicians and treatment. Relationships among these factors were examined using Pearson product-moment correlations and multivariable linear regression.

Results:

At baseline, the mean electronic pill cap adherence rate showed that patients took 85.57% of their oral therapy. The most commonly reported cancer-related symptoms were fatigue (88.60%), drowsiness (76.50%), disturbed sleep (68.20%), memory problems (63.10%), and emotional distress (60.80%). Patients who reported greater cancer-related symptom severity had lower adherence (r= –0.20). In a multivariable regression, greater depressive and anxiety symptoms, worse fatigue, less social support, lower satisfaction with clinicians and treatment, and higher symptom burden were associated with worse QoL (F[10, 146]=50.53; adjusted R2=0.77). Anxiety symptoms were most strongly associated with clinically meaningful decrements in QoL (β= –7.10; SE=0.22).

Conclusions:

Patients prescribed oral therapies struggle with adherence, and cancer-related symptom burden is high and related to worse adherence and QoL. Given perceptions that oral therapies are less impairing, these data underscore the strong need to address adherence issues, symptom burden, and QoL for these patients.

Background

Orally administered cancer therapy medications have become available in the past 2 decades,1 and the number of patients receiving oral therapies continues to multiply.2 The increased use of oral therapy has revolutionized cancer care through improved disease outcomes and patient survival, and convenience of treatment administration.3 Given the option to choose between oral and intravenous therapies, patients overwhelmingly prefer oral administration, citing convenience of home administration and reduction of both discomfort and stress of intravenous treatments.4 Although oral therapies are perceived to offer better quality of life (QoL) compared with intravenous therapies, challenges with this treatment persist, including suboptimal adherence,5 side effects, and misconceptions about convenience.4,6,7

Because patients prescribed oral therapies are not seen routinely in an infusion clinic, symptoms and side effects that influence QoL and adherence are not always reported.6 Symptom prevalence has been described mostly in patients receiving intravenous chemotherapy or patients with breast cancer on adjuvant endocrine therapy.8,9 Because patients on oral therapy do not receive the same degree of oversight and monitoring as those on intravenous treatment,10,11 which could negatively influence adherence,12 it is important to understand patients’ symptom burden, adherence, and distress in a clinical setting.

Although oral therapy is thought to impair QoL less than intravenous treatment,4 data are lacking with respect to the physical and psychologic symptoms that patients experience, which could negatively impact adherence. Furthermore, a complete understanding of QoL or the correlates of QoL for these patients does not exist, although some literature shows nonadherence is related to greater symptom distress,13 poorer QoL,14 lack of social support,15 lower satisfaction with treatment,16 and psychologic distress.15 We sought to describe rates of adherence and characterize the physical and psychologic symptoms of patients prescribed oral therapy. Additionally, we aimed to identify the factors related to medication adherence and QoL to better understand and describe the needs of patients prescribed oral therapies within the framework that nonadherence would be associated with more symptom distress, poorer QoL, and greater psychologic symptoms.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

From February 13, 2015, to December 31, 2016, patients prescribed oral therapy (ie, targeted or chemotherapy) for diverse malignancies participated in a parallel assignment, randomized controlled trial of adherence and symptom management comparing a smartphone mobile application (app) intervention to standard oncology care (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02157519). We describe the rates and correlates of symptom burden, adherence, and QoL using baseline data only, before randomization and intervention. Patients were recruited from the out-patient oncology clinics at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) Cancer Center in Boston, Massachusetts and 2 satellite clinics. The study was approved by the Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center Institutional Review Board.

Participants

To be eligible, patients were required to have a diagnosis of cancer and a current prescription for oral targeted therapy or chemotherapy. Additional eligibility criteria included (1) age >18 years, (2) receipt of cancer care at MGH Cancer Center or a satellite clinic, (3) ECOG performance status score ≤2, (4) ability to read and respond to questions in English, and (5) possession and use of a smartphone (with iOS [iPhone] or Android operating system). Patients with comorbid acute or untreated psychiatric symptoms or neurologic dysfunction were not eligible to participate because of the potential for acute symptoms to interfere with participation. Patients enrolled in oral therapy clinical trials were not eligible to participate due to the potential for trial requirements (eg, use of drug diaries) to influence current study outcomes.

Procedure

Study staff queried the electronic health record (EHR) to identify patients with current oral therapy prescriptions and screened them for initial eligibility criteria. Patients who met inclusion criteria were approached during their next clinic visit after approval from their oncology clinician. Those who met eligibility criteria and were interested in participating signed an informed consent document with study staff and completed the baseline self-report assessments by paper or electronically with Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap), a web-based survey tool. After baseline assessment, participants were given a pill bottle with an electronic cap to monitor medication-taking patterns and were randomly assigned in a 1:1 fashion to the mobile app intervention or the standard oncology care control group.

Measures

Sociodemographic and Clinical Factors

Participants reported their age, sex, race, ethnicity, education level, relationship status, income, and employment. Research staff collected information about cancer diagnosis, oral therapy type, and other clinical characteristics from the EHR.

Electronic Adherence Monitoring

Participants were asked to store their oral therapy medication in pill bottles with electronic caps (ie, Medication Event Monitoring System cap17 or GlowCap), which record the date and time the bottle is opened. An adherence rate (0%–100%) was operationalized as the percentage of medication taken of the prescribed dosage during a 2-week baseline period after the self-reported assessments and randomization (ie, number of cap openings vs number of expected openings per prescribed dosing schedule). To record adherence accurately for patients on an interval dosing schedule compared with a continuous daily schedule, we reviewed each patient’s EHR and adjusted the electronic database to align with dosing schedules and planned chemotherapy breaks.

Quality of Life

The 27-item Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy - General (FACT-G)18 was used to assess QoL in physical, social/family, emotional, and functional domains of well-being during the past week.

Cancer-Related Symptoms

The 19-item MD Anderson Symptom Inventory (MDASI)19 was administered to assess cancer-related symptom interference and severity, with higher scores indicating greater symptom burden.

Mood

The 14-item Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)20 was used to examine depressive and anxiety symptoms during the past week. It is comprised of two 7-item subscales for assessing depressive and anxiety symptoms, with higher scores indicating worse distress.

Satisfaction With Clinician Communication and Treatment

Specific subscales of the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy - Treatment Satisfaction - Patient Satisfaction (FACIT-TS-PS)21 questionnaire were used to assess satisfaction with clinician communication and treatment, with higher scores indicating greater satisfaction.

Perceived Social Support

Perception of support was assessed using the 12-item Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS),22 with higher scores indicating greater perceived support.

Fatigue

The severity of cancer-related fatigue and its impact on functioning in the past 24 hours was measured using the 10-item Brief Fatigue Inventory (BFI),23 with higher scores indicating worse fatigue.

Statistical Analyses

Data were analyzed using the SPSS Statistics, version 22 (SPSS Inc.). All self-reported measures demonstrated strong reliability (α>0.80). Patient clinical and socio-demographic characteristics and cancer-related symptom interference and severity were described with measures of central tendency and proportions. Because no established criterion for optimal adherence to oral therapy exists, we examined adherence cutoffs of 90%24 and 80%,25 consistent with prior studies in addition to the continuous adherence rate. Bivariate Pearson product-moment correlations and one-way analyses of variance were conducted to examine relationships between socio-demographic characteristics, treatment factors, and psychosocial constructs with the continuous adherence rate and QoL. Statistical significance was based on a 2-sided alpha of 0.05. To identify independent predictors of QoL, we computed a multivariable linear regression model and determined the degree of association above and beyond the influence of other variables in the model. Unstandardized regression coefficients (βs) and CIs were obtained to determine the magnitude of the relationship, with a 2-sided α<0.05 considered statistically significant. Based on previous work, a difference in the total FACT-G of ≥5 points represented a clinically meaningful change in QoL.26 To address missing data, we repeated analyses in Mplus, which uses the full information maximum likelihood method to estimate missing data points from relationships among variables in the sample.27

Results

Through screening of the EHR, we identified 696 potentially eligible patients. Of these, 28.2% were deemed ineligible because the clinician did not respond to our request (n=134) or denied permission (n=62) to approach the patient. With clinician permission, study staff approached 500 patients (71.8%) to assess eligibility. Among this group, 178 did not own a smartphone and 110 declined to participate, resulting in 212 patients who signed an informed consent and enrolled. Because participants prescribed oral therapy do not have frequent oncology visits, baseline visits occurred a mean of 36 days (SD, 49) after the enrollment visit. During this time, 31 participants dropped out because they (1) became ineligible (n=11; 8 discontinued oral therapy, 2 began a clinical trial, 1 no longer received care at MGH Cancer Center); (2) declined to continue (n=17); or (3) were lost to follow-up (n=3). Therefore, the final sample consisted of 181 participants who completed the self-report baseline assessment and were randomized. Of these participants, 32 were missing the baseline MDASI (31 due to an administrative error and 1 due to incomplete measure), and the baseline electronic pill cap adherence rate was available on 170 participants. Reasons for missing pill cap data were (1) pill bottle/cap not returned (n=9); (2) no data on cap (n=1); or (3) lost in mail (n=1). Participant sociodemographic and clinical characteristics are presented in Table 1. A list of oral chemotherapy and targeted therapy drugs is provided in eAppendix 1 (available with this article at JNCCN.org). Analyses were first conducted with complete case analysis (n=149 for analyses including the MDASI and n = 170 for analyses including electronic adherence data), followed by multiple imputation (n=181).

Table 1.

Baselline Patient Characterstics (N=181).

| Characteristic | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (range, 21–88 y), mean (SD), y | 53.30 (12.91) |

| Sex | |

| Women | 97 (53.6) |

| Men | 84 (46.4) |

| Race | |

| White | 159 (87.8) |

| Asian | 10 (5.5) |

| Black or African American | 5 (2.8) |

| Hispanic or Latino | 4 (2.2) |

| Multiracial | 2 (1.1) |

| Other | 1 (0.6) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic or Latino | 5 (2.8) |

| Education | |

| Advanced degree | 81 (44.8) |

| Some college/technical school | 44 (24.3) |

| College graduate | 42 (23.2) |

| High school graduate/GED | 14 (7.7) |

| Relationship status | |

| Married/Living as if married | 136 (75.1) |

| Single | 35 (19.4) |

| Non-cohabitating relationship | 9 (5.0) |

| Declined | 1 (0.6) |

| Employment status | |

| Full-time or part-time work/school | 110 (60.8) |

| Retired/Unemployed/Disability | 69 (38.1) |

| Other/Missing | 2 (1.1) |

| Incomea | |

| <$25,000 | 16 (8.8) |

| $25,000–$50,000 | 19 (10.5) |

| $51,000–$100,000 | 40 (22.1) |

| $101,000–$150,000 | 49 (27.1) |

| >$150,000 | 51 (28.2) |

| Declined | 6 (3.3) |

| Cancer type | |

| Hematologic | 60 (33.1) |

| Non–small cell lung cancer | 33 (18.2) |

| Breast cancer | 26 (14.4) |

| High-grade glioma | 21 (11.6) |

| Sarcoma (including 2 non-GIST) | 14 (7.7) |

| Gastrointestinal | 8 (4.4) |

| Genitourinary | 7 (3.9) |

| Melanoma | 7 (3.9) |

| Low-grade glioma | 5 (2.8) |

| Disease stage (solid tumors only; n = 85) | |

| 0 | 1 (1.2) |

| I | 2 (2.3) |

| II | 5 (5.9) |

| III | 4 (4.7) |

| IV | 73 (85.9) |

| Oral therapy type | |

| Targeted | 121 (66.9) |

| Chemotherapy | 60 (33.1) |

| Months since oral therapy initiation (range, 0–136), mean (SD) | 12.70 (20.87) |

| ECOG performance status | |

| 0 | 89 (49.2) |

| 1 | 87 (48.1) |

| 2 | 5 (2.8) |

| Number of prescribed medications at baseline (range, 0–19), mean (SD) | 5.82 (3.99) |

| Received intravenous chemotherapy on study | 26 (14.4) |

| Quality of life (FACT-G; range, 40–108), mean (SD) | 81.73 (15.12) |

Abbreviations: FACT-G, Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General; GIST, gastrointestinal stromal tumor.

Income categories were prespecified and rounded where appropriate.

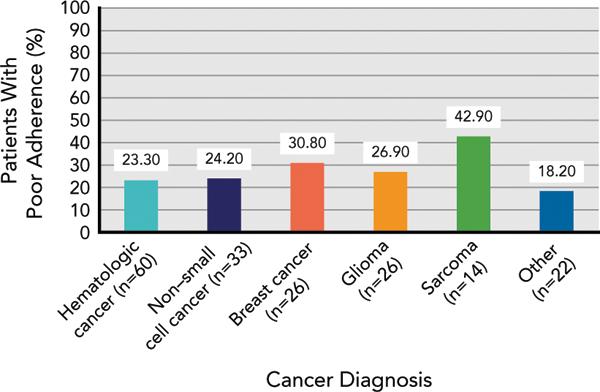

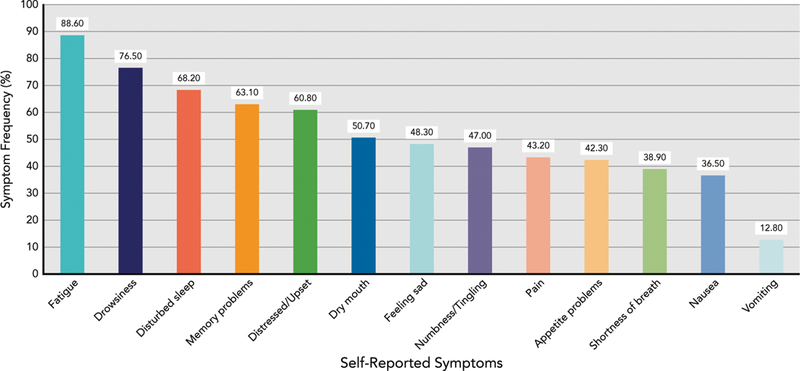

Adherence, Cancer-Related Symptom Severity, and Interference

The mean electronic pill cap adherence rate at baseline was 85.57% (SD, 28.04) and was not associated with group assignment (r= 0.008; P=.922). Using a 90% adherence cutoff score, 26% of the sample was poorly adherent (n=47); and with an 80% adherence cutoff score, 17% of the sample (n=31) was poorly adherent. Adherence rates did not differ by cancer type (Figure 1) or other clinical or treatment-related characteristics. Cancer-related symptoms with the highest rated severity on average were fatigue (mean, 3.65 [SD, 2.61]), drowsiness (mean, 2.89 [SD, 2.61]), disturbed sleep (mean, 2.60 [SD, 2.75]), memory problems (mean, 1.95 [SD, 2.21]), and distress (mean, 1.85 [SD, 2.25]; see Figure 2 for symptom frequencies). Examining differences in electronic pill cap adherence rate by sociodemographic and psychosocial characteristics, we observed that patients who reported greater cancer-related symptom severity had lower adherence (r= –0.20; P=.020). Similarly, patients who reported greater cancer-related symptom interference had worse adherence; however, this association was marginally significant (r= –0.15; P=.068). Adherence was not associated with other sociodemographic, clinical, or psychosocial constructs. Results did not differ when controlling for group assignment.

Figure 1.

Adherence rates by cancer type using a 90% adherence cutoff score.

Figure 2.

Distribution of self-reported symptoms (N = 149).

QoL and Correlates

Baseline QoL scores in our sample (median, 81.73 [SD, 15.12]) were comparable to scores on the FACT-G in a normative sample26 (n=2,236) of patients with cancer on various treatments (median, 80.9 [SD, 17.0]; mean difference, 0.83; SE difference, 1.31; t(2,413), 0.63; P=.528; 95% CI, –1.75 to 3.40). Bivariate examination of associations of baseline characteristics with QoL showed that patients with a poorer performance status (r= –0.25; P=.001), a greater number of prescribed medications (r= –0.19; P= .009), and fewer months on oral therapy (r= 0.19; P= .013) reported worse QoL. Bivariate correlations revealed that greater cancer-related symptom severity (r= –0.67; P<.0001), greater cancer-related symptom interference (r = –0.78; P<.0001), worse fatigue (r= –0.70; P<.0001), lower satisfaction with treatment and communication with clinicians (r=0.22; P=.003), more depressive symptoms (r= –0.78; P<.0001), more anxiety symptoms (r= –0.64; P<.0001), and lower perceived social support (r=0.34; P<.0001) were associated with worse QoL. Adherence was not associated with QoL in this sample (r=0.040; P=.604).

Factors associated with QoL were entered simultaneously into a multivariable linear regression that explained 77% of the variance in QoL (F[10,146] =50.53; P<.001) (Table 2). Anxiety symptoms, depressive symptoms, lower perceived social support, lower satisfaction with treatment and clinician communication, and greater cancer-related symptom interference remained significantly related to worse QoL. For example, a 1-point increase in anxiety symptoms was associated with a 7.10-point reduction in QoL (β= –7.10; SE, 0.22; 95% CI, –1.14 to –0.29; P=.001), that is both statistically and clinically significant. Furthermore, a 1-point increase in symptom interference was associated with a 2.30-point reduction in QoL (β = –2.30; SE, 0.57; 95% CI, –3.42 to –1.17; P<.001). Although this difference in QoL was statistically significant, it did not reach the threshold for a clinically meaningful change. Findings were consistent using a full case analysis in Mplus.

Table 2.

Multiple Regression Illustrating Relationships Between Psychosocial Factors and QoL

| QoL (FACT-G) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unstandardized |

Standardized |

||||

| Variable | B | SE | (95% CI) | β | P Value |

| Anxiety (HADS) | –7.10 | 0.22 | (–1.14 to –0.29) | –0.18 | .001a |

| Depressive symptoms (HADS) | –1.45 | 0.33 | (–2.11 to –0.79) | –0.30 | <.001a |

| Fatigue severity (BFI) | –0.59 | 0.53 | (–1.63 to 0.45) | –0.09 | .262 |

| Perceived social support (MSPSS) | 2.09 | 0.67 | (0.77–3.42) | 0.13 | .002a |

| Satisfaction with treatment & providers (FACIT-TS-PS) | 0.17 | 0.08 | (0.02–0.32) | 0.09 | .027a |

| Symptom severity (MDASI) | –0.18 | 0.71 | (–1.59 to 1.22) | –0.02 | .797 |

| Symptom interference (MDASI) | –2.30 | 0.57 | (–3.42 to –1.17) | –0.32 | <.001a |

| ECOG performance status | –2.09 | 1.23 | (–4.52 to 0.34) | –0.07 | .091 |

| Number of months on oral chemotherapy | –0.01 | 0.03 | (–0.06 to 0.05) | –0.01 | .848 |

| Number of other medications | –0.04 | 0.17 | (–0.37 to 0.28) | –0.01 | .790 |

| Total model: adjusted R2=0.77; F[10, 146]=50.53; P<.001 | |||||

Abbreviations: BFI, Brief Fatigue Inventory (range, 0–10); FACIT-TS-PS, Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy - Treatment Satisfaction - Patient Satisfaction (range, 0–63); FACT-G, Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–General (range, 0–108); HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (range, 0–21); MDASI, MD Anderson Symptom Inventory (range, 0–10); MSPSS, Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (range, 1–7); QoL, quality of life.

P<.05.

Discussion

We examined adherence, symptom burden, and QoL in patients with diverse malignancies who were prescribed oral therapy and enrolled in a randomized study of adherence and symptom management. Based on electronic pill cap monitoring, patients took, on average, 86% of doses as prescribed. Using cutoffs commonly reported in the literature, 26% of the sample was <90% adherent and 17% was <80% adherent. Adherence in this sample was only slightly better than reported in a recent study showing that 30% of patients reported <80% adherence to oral chemotherapy,25 and in line with prior studies showing 69.6% to 88.2% adherence after 1 year of taking oral therapies.28

Many oncology practices do not have protocols in place for educating patients about managing symptoms, taking medications appropriately, or monitoring symptoms and adherence.29 In addition, research into adherence intervention is necessary for patients prescribed oral cancer therapies, because the few published intervention studies to date were plagued by poor methodological rigor.28 Within our current Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute–funded study (IHS-1306–03616), we developed and are testing the efficacy of a mobile app that incorporates symptom tracking, oral therapy reminders and treatment planning, resources for symptom management and activity tracking, and symptom data transfer to the oncology team.30

Despite being on oral therapy, patients reported a high cancer-related symptom burden that is not being addressed in the current care delivery model. Patients in this sample reported fatigue, drowsiness, and disturbed sleep as the most burdensome and severe symptoms. Importantly, more than three-quarters of the sample reported fatigue, which is consistent with literature suggesting that >80% of outpatients receiving chemotherapy report fatigue.31 In addition, more than half of the participants reported emotional distress, which is consistent with prior work showing that nearly half of patients with cancer report psychologic distress in the form of anxiety, depression, or both.32 Notably, we found that patients reporting greater cancer-related symptom severity had worse adherence to oral therapy per electronic monitoring. Patients with greater symptom distress and interference also tended to have poorer adherence, consistent with recent findings of a study on adherence and symptom distress,13 and our previous study showing that patients with cancer who reported higher symptom distress over time experienced poorer medication adherence.16

As the number of patients receiving oral cancer therapies continues to increase, the process for monitoring side effects and managing adherence requires attention. Although patients report preference for oral administration,3 few studies have compared QoL in patients prescribed oral versus intravenous chemotherapy. A study of patients with colon cancer showed no difference in QoL between those receiving oral chemotherapy and those receiving intravenous chemotherapy.33 In contrast, a study of patients with advanced breast or ovarian cancers showed reduced QoL in those receiving intravenous chemotherapy versus those receiving oral therapy.34 Patients in this sample had comparable QoL to those from a normative sample receiving various cancer treatments.26 This question requires additional investigation to understand whether administration of oral therapy is related to better QoL, as is often purported.

Our findings suggest that patients with poorer performance status, a greater number of concomitant medications, and fewer months on oral therapy had lower QoL. In addition, those with greater cancer-related symptom severity and interference, worse fatigue, lower satisfaction with treatment and communication with clinicians, higher anxiety and depressive symptoms, and lower perceived social support had worse QoL. Contrary to previous literature showing a positive association between QoL and adherence to cancer therapies,14,16 these constructs were not related in our sample. Higher anxiety was most strongly related with worse QoL, with even minimal increases in anxiety associated with large and clinically meaningful reductions in QoL. This finding is in line with prior work showing strong relationships between anxiety disorders and deficits in QoL in patients with diverse malignancies.35 Referrals to supportive care services, such as psychiatry, psychology, or social work, are effective in the management of anxiety during cancer treatment, can lead to improvements in QoL and perhaps adherence, can address deficits in social support, and can enhance advocacy for dissatisfied patients. However, management of distress is not routinely integrated into current models of cancer care, and it is possible that patients receiving oral therapy are less likely to share mood symptoms with their healthcare team. In addition, it is possible that more routine monitoring or check-ins with patients may improve patient satisfaction and sense of support, which may, in turn, improve QoL. Notably, NCCN provides guidelines for distress management, including screening, assessment, referral to appropriate supportive care services, and follow-up.36

As a cross-sectional study, we cannot infer directionality based on associations among factors. In addition, our sample was restricted with respect to demographic and socioeconomic diversity, limiting the generalizability of our findings. Unfortunately, measurement of adherence to oral therapies is an ongoing challenge given the variability in dosing schedules within the treatment regimens. Although strengths of electronic adherence collection include real-time data and the provision of an objective, minimally biased adherence measure, weaknesses include the fact that opening a pill bottle does not guarantee that medication was taken at that time, and oral therapies in blister packs are difficult to store in these pill bottles. Future research should incorporate a built-in baseline assessment period for electronic pill caps before randomization. It is also important to consider that adherence among these willing study participants is likely higher than among individuals in the general population. Although most of our sample was composed of patients with stage IV disease, we were not able to ascertain whether symptom distress and QoL are related to oral therapies or to advanced-stage disease. Literature in this area is largely based on correlational studies, including the current study; therefore, future studies should use longitudinal data to examine the directionality of relationships between symptom distress, QoL, and adherence.

Conclusions

In this sample of patients with diverse malignancies prescribed oral cancer therapy, participants took only 85% of oral therapy, on average. Patients identified high levels of cancer-related symptoms, the severity of which was also associated with poor adherence by objective adherence monitoring. Despite patient preference for oral therapy, global patient-reported QoL did not differ from a normative sample receiving various cancer treatments. Moreover, elevated anxiety was most strongly associated with worse QoL, followed by cancer-related symptom interference. These data underscore the need to recognize that patients prescribed oral therapies are not necessarily better off than those on intravenous treatment, and to develop research protocols that examine strategies to better manage adherence, symptoms, and QoL for these patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: Research reported in this manuscript was funded through a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute Award (IHS-1306–03616).

Footnotes

Disclosures: Dr. Lennes has disclosed that she has received honorarium from BCBS Massachusetts and has received compensation by Kyruus for consulting/advisory work. Dr. Safren has disclosed that he has received book royalties from Oxford University Press, Guilford Press, and Springer/Human Press. Dr. Temel has disclosed that she has received research funding from Pfizer. The remaining authors have disclosed that they have not received any financial considerations from any person or organization to support the preparation, analysis, results, or discussion of this article.

Disclaimer: The statements presented in this work are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), its Board of Governors, or Methodology Committee.

References

- 1.O’Neill VJ, Twelves CJ. Oral cancer treatment: developments in chemotherapy and beyond. Br J Cancer 2002;87:933–937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neuss MN, Polovich M, McNiff K, et al. 2013 updated American Society of Clinical Oncology/Oncology Nursing Society chemotherapy administration safety standards including standards for the safe administration and management of oral chemotherapy. Oncol Nurs Forum 2013;40:225–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borner M, Scheithauer W, Twelves C, et al. Answering patients’ needs: oral alternatives to intravenous therapy. Oncologist 2001;6(Suppl 4):12–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eek D, Krohe M, Mazar I, et al. Patient-reported preferencesfororalversus intravenous administration for the treatment of cancer: a review of the literature. Patient Prefer Adherence 2016;10:1609–1621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weingart SN, Brown E, Bach PB, et al. NCCN task force report: oral chemotherapy. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2008;6(Suppl 3):S1–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Given BA, Spoelstra SL, Grant M. The challenges of oral agents as antineoplastic treatments. Semin Oncol Nurs 2011;27:93–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Banna GL, Collovà E, Gebbia V, et al. Anticancer oral therapy: emerging related issues. Cancer Treat Rev 2010;36:595–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cardoso G, Graca J, Klut C, et al. Depression and anxiety symptoms following cancer diagnosis: a cross-sectional study. Psychol Health Med 2016;21:562–570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kristensen A, Solheim TS, Amundsen T, et al. Measurement of health-related quality of life during chemotherapy—the importance of timing. Acta Oncol 2017;56:737–745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barton D Oral agents in cancer treatment: the context for adherence. Semin Oncol Nurs2011;27:104–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aisner J Overview of the changing paradigm in cancer treatment: oral chemotherapy. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2007;64(Suppl):S4–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bedell CH. Achanging paradigm forcancertreatment: the advent ofnew oral chemotherapy agents. Clin J Oncol Nurs 2003;7(Suppl):5–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berry DL, Blonquist TM, Hong F, et al. Self-reported adherence to oral cancer therapy: relationships with symptom distress, depression, and personal characteristics. Patient Prefer Adherence 2015;9:1587–1592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cheville AL, Alberts SR, Rummans TA, et al. Improving adherence to cancer treatment by addressing quality of life in patients with advanced gastrointestinal cancers. J Pain Symptom Manage 2015;50:321–327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mathes T, Antoine SL, Pieper D,et al. Adherence enhancing interventions fororal anticancer agents: a systematic review. Cancer Treat Rev 2014;40: 102–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jacobs JM, Pensak NA, Sporn NJ, et al. Treatment satisfaction and ad-herenceto oral chemotherapy in patients with cancer. J Oncol Pract 2017; 13:e474–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Farmer KC. Methods for measuring and monitoring medication regimen adherence in clinical trials and clinical practice. Clin Ther 1999;21: 1074–1090, discussion 1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cella DF, Tulsky DS, Gray G, et al. The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy scale: development and validation of the general measure. J Clin Oncol 1993;11:570–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cleeland CS, Mendoza TR, Wang XS, et al. Assessing symptom distress in cancer patients: the M.D. Anderson Symptom Inventory. Cancer 2000;89:1634–1646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1983;67:361–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peipert JD, Beaumont JL, Bode R, et al. Development and validation of the functional assessment of chronic illness therapy treatment satisfaction (FACIT TS) measures. [Erratum in Qual Life Res 2014; 23:1907.] Qual Life Res 2014;23:815–824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zimet GD, Dahlem NW, Zimet SG, et al. The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J Pers Assess 1988;52:30–41. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mendoza TR, Wang XS, Cleeland CS, et al. The rapid assessment of fatigue severity in cancer patients: use of the Brief Fatigue Inventory. Cancer 1999;85:1186–1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krolop L, Ko YD, Schwindt PF, et al. Adherence management for patients with cancer taking capecitabine: a prospective two-arm cohort study. BMJ Open 2013;3:e003139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mackler E, Beekman K, Bushey L, et al. Utilizing patient reported outcomes for patients receiving oral chemotherapy [abstract]. J Clin Oncol 2017;35(Suppl):Abstract 190. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brucker PS, Yost K, Cashy J, et al. General population and cancer patient norms for the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General (FACT-G). Eval Health Prof 2005;28:192–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Muthen LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide, 6th ed Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 1998–2010. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Greer JA, Amoyal N, Nisotel L, et al. A systematic review of adherence to oral antineoplastic therapies. Oncologist 2016;21:354–376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weingart SN, Li JW, Zhu J, et al. US cancer center implementation of ASCO/Oncology Nursing Society chemotherapy administration safety standards. J Oncol Pract 2012;8:7–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fishbein JN, Nisotel LE, MacDonald JJ, et al. Mobile application to promote adherence to oral chemotherapy and symptom management: a protocol for design and development. JMIR Res Protoc 2017; 6:e62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hofman M, Ryan JL, Figueroa-Moseley CD, et al. Cancer-related fatigue: the scale of the problem. Oncologist 2007;12(Suppl 1):4–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zabora J, BrintzenhofeSzoc K, Curbow B, et al. The prevalence of psychological distress by cancer site. Psychooncology 2001;10:19–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kopec JA, Yothers G, Ganz PA, et al. Quality of life in operable colon cancer patients receiving oral compared with intravenous chemotherapy: results from National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project trial C-06. J Clin Oncol 2007;25:424–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Payne SA. A study of quality of life in cancer patients receiving palliative chemotherapy. Soc Sci Med 1992;35:1505–1509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stark D, Kiely M, Smith A, et al. Anxiety disorders in cancer patients: their nature, associations, and relation to quality of life. J Clin Oncol 2002;20: 3137–3148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Holland JC, Deshields TL, Andersen B, et al. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Distress Management. Accessed January 31, 2019 To view the most recent version of these guidelines, visit NCCN.org.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.