Abstract

Herein we report the first structure of topoisomerase I determined from the gram-positive bacterium, S. mutans. Bacterial topoisomerase I is an ATP-independent type 1A topoisomerase that uses the inherent torsional strain within hyper-negatively supercoiled DNA as an energy source for its critical function of DNA relaxation. Interest in the enzyme has gained momentum as it has proven to be essential in various bacterial organisms. In order to aid in further biochemical characterization, the apo 65-kDa amino-terminal fragment of DNA topoisomerase I from the gram-positive model organism Streptococcus mutans was crystalized and a three-dimensional structure was determined to 2.06 Å resolution via x-ray crystallography. The overall structure illustrates the four classic major domains that create the traditional topoisomerase I “lock” formation comprised of a sizable toroidal aperture atop what is considered to be a highly dynamic body. A catalytic tyrosine residue resides at the interface between two domains and is known to form a 5’ phosphotyrosine DNA-enzyme intermediate during transient single-stranded cleavage required for enzymatic relaxation of hyper negative DNA supercoils. Surrounding the catalytic tyrosine residue is the remainder of the highly conserved active site. Within 5 Å from the catalytic center, only one dissimilar residue is observed between topoisomerase I from S. mutans and the gram-negative model organism E. coli. Immediately adjacent to the conserved active site, however, S. mutans topoisomerase I displays a somewhat unique nine residue loop extension not present in any bacterial topoisomerase I structures previously determined other than that of an extremophile.

Keywords: Crystal structure, topoisomerase I, DNA topology, Streptococcus mutans, type IA topoisomerase, negative supercoiling

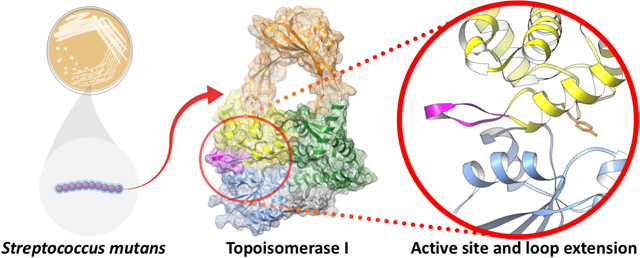

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

DNA topoisomerase I (topo I) is a monomeric enzyme found in all bacteria that is mainly responsible for relaxing hyper-negative DNA supercoils [1–3]. It is a type IA topoisomerase with a highly dynamic mechanism of action, initiating a single-stranded break in DNA while forming a 5’-phosphotyrosine intermediate [1]. The enzyme functions independently of ATP, and instead relies on the torsional strain of its hyper-negatively supercoiled DNA target as an energy source [1]. Of note, bacterial topo I and the other bacterial type IA topoisomerase, topo III, lack any clinically approved inhibitors at this time [1,4,5]. Overall interest in type IA topoisomerases continues to increase, however, especially with regard to efforts aimed at discovering and developing novel antibacterial agents—particularly topo I inhibitors [6–10]. Aiding in these efforts, several three-dimensional apo- and co-crystal structures of topo I from various bacterial species have been determined, including those from the gram-negative model organism E. coli (EcTopoI) [11], the gram-negative extremophile Thermotoga maritima (TmTopoI) [12], and the uniquely non-gram-classified Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MtTopoI) [13].

Though E. coli prevails as the predominant model organism in microbiological research, inherent differences exist between gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria. Accordingly, as Streptococcus mutans has gained utility as a gram-positive model organism [14], efforts were undertaken to obtain diffraction-quality full-length S. mutans topo I (SmTopoI) protein crystals. Though, similar to other topo I crystallization campaigns reported in the literature, such efforts were met with initial difficulty [11,13]. Therefore, rational constructs of main body N-terminal fragment of SmTopoI were cloned and expressed to remove the flexible C-terminal domain and improve chances of crystallization. This eventually led to a 65-kDa fragment (SmTopoI_N65) that yielded high diffraction-quality crystals used for structural characterization of SmTopoI. Herein we present the three-dimensional crystal structure of SmTopoI_N65, the first topoisomerase I structure determined from a gram-positive bacterium, along with its structural characterization.

Materials and Methods

SmTopoI_N65 cloning, expression, purification and crystallization

SmTopoI_N65 was cloned, expressed, and purified to over 95% purity via PAGE analysis similarly to full-length SmTopoI described elsewhere [15]. However, the target construct gene of interest, topA_N65, was amplified via PCR off of the topA-containing SmTopI_16b plasmid based around the NdeI and BamHI restriction sites using the following primers:

TopA_Forward: 5′-TGT AGA CAT ATG ACA AGT AAA ACA ACG ACA ACA G-3′

TopA_N65_Rev: 5’-GGA TGG ATC CTT ACT GTT CCT CTG C-3’

The gene was ligated into a pET-15b vector (Novagen® EMD Millipore®, Billerica, MA)and the target plasmid was transformed into BL21(DE3)-Gold Competent cells (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) per protocol. The target enzyme was expressed via auto induction and purified per previous protocol, except Tris was substituted for all phosphate buffers [15,16]. Briefly, cells were lysed for 1 hour at 4°C in Lysis Buffer composed of 20 mM Tris-hydrochloride (HCl) pH 8.0, one Pierce® EDTA-free protease inhibitor tablet per 50 mL, 1 mM DTT, 0.5% Triton X, 0.5 M NaCl, 5% glycerol, 0.5 mg/mL lysozyme, and 5 mM imidazole; then sonicated, centrifuged, and filtered at 0.22 μm. Hexa-his-tagged protein was purified using a HisTrap-HP 5 mL column on an ÄKTA Purifier FPLC (GE Healthcare Lifesciences, Pittsburgh, PA) via step-gradient nickel immobilized metal affinity chromatography (IMAC) in Buffer A, composed of 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 1 M NaCl, 5 mM imidazole, and 5% glycerol, and Buffer B, composed of 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 0.5 M NaCl, 350 mM imidazole, and 5% glycerol. The sample was then purified on a GE HiLoad 26/600 Superdex 200 PG size exclusion chromatography (SEC) column in SEC Buffer, composed of 20 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 1 mM MgCl2, 0.5 M NaCl, and 1 mM DTT. Target protein fractions were pooled, concentrated with a 10,000 MWCO Amicon™ Ultra-15 Centrifugal Filter Unit from EMD Millipore® (Billerica, MA) and used for crystallography.

SmTopoI_N65 was crystallized at 4.6 mg mL−1 in a 3uL:3uL 1:1 ratio protein to condition using the hanging-drop vapor-diffusion method off of a coarse-matrix screen. The initial crystal growth condition was JCSG-plus (Molecular Dimensions, Maumee, OH) condition 1–5 (0.2 M magnesium formate dihydrate, 20% w/v PEG 3350) at 18°C. A 1:1 mixture of Izit Crystal Dye (Hampton Research, Aliso Viejo, CA) and acid red dye was added to original crystal-containing drops and allowed to stain overnight for preliminary crystal assessment. Unstained crystals from the same well, but from a different drop, were collected for X-ray diffraction analysis. Initial crystals showed relatively weak diffraction (greater than 4 Å). Optimized crystals were then obtained via fine grid screen in 0.2 M magnesium formate dihydrate, 25% w/v PEG 3350 at 4°C and unstained crystals were collected for analysis. Crystals were grown in 48-well VDX plates with sealant (Hampton Research, Aliso Viejo, CA) and were visible within two weeks.

SmTopoI_N65 structure determination, and refinement

SmTopoI_N65 crystals were harvested, looped through 20% w/v PEG 3350/30% MPD in the crystallization condition for cryo-protection, and cooled to 100 K for data collection. A complete data set was collected at GM/CA-CAT beamline 23ID-D of sector 23 of the Advanced Photon Source (APS), Argonne National Laboratory, Lemont, Illinois, USA (Table 1). Data were processed and scaled, then the structure of SmTopoI_N65 was determined via molecular replacement using the previously determined 67-kDa N-terminal fragment of EcTopoI (PDB 1ECL)[17] all using the HKL-3000 suite [18]. Initial automatic model building was performed within HKL-3000 using Buccaneer [18,19]. Refinement was then conducted using phenix.refine and the model was further built out using AutoBuild from the PHENIX suite [20]. Subsequent refinement and model building was conducted iteratively with phenix.refine and Coot [20,21]. Late-stage automated re-refinement was conducted using PDB_REDO [22]. Validation of the structure was conducted within PHENIX using MolProbity [23]. Figure 1 was produced with the UCSF Chimera package [24].

Table 1.

Data collection and refinement statistics for SmTopo_N65

| Data collection | |

|---|---|

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.033 |

| Space Group | P 21 21 2 |

| Unit cell parameters | |

| a, b, c (Å) | 88.58 98.37 72.71 |

| α, β, γ (°) | 90 90 90 |

| Resolution (Å) | 50.00–2.06 (2.10–2.06)a |

| CC1/2 | 0.999 (0.690) |

| Rmeas | 0.084 (1.047) |

| Rpim | 0.032 (0.441) |

| Total no. of reflections | 254919 |

| No. of unique reflections | 32714 (1394) |

| Completeness (%) | 82.17 (35.50) |

| Redundancy | 6.5 (5.1) |

| Mean I/sigma | 21.8 (1.5) |

| Refinement | |

| Number of reflections used | 32713 (1395) |

| Resolution (Å) | 49.18–2.063 (2.137–2.063) |

| Rwork | 0.2003 (0.2310) |

| Rfree | 0.2677 (0.3617) |

| No. of non-H atoms | 4700 |

| Macromolecules | 4339 |

| Ligands | 48 |

| Solvent | 313 |

| Protein residues | 538 |

| RMS (bonds) | 0.008 |

| RMS (angles) | 0.92 |

| Ramachandran favored (%) | 33.18 |

| Ramachandran allowed (%) | 3.20 |

| Ramachandran outliers (%) | 0.56 |

| Rotamer outliers (%) | 0.42 |

| Clash score | 4.98 |

| Average B-factor | 33.18 |

| Macromolecules | 33.10 |

| Ligands | 45.88 |

| Solvent | 32.35 |

Statistics for the highest-resolution shell are shown in parentheses.

CC1/2 is the Pearson’s correlation coefficient of random half sets of data.

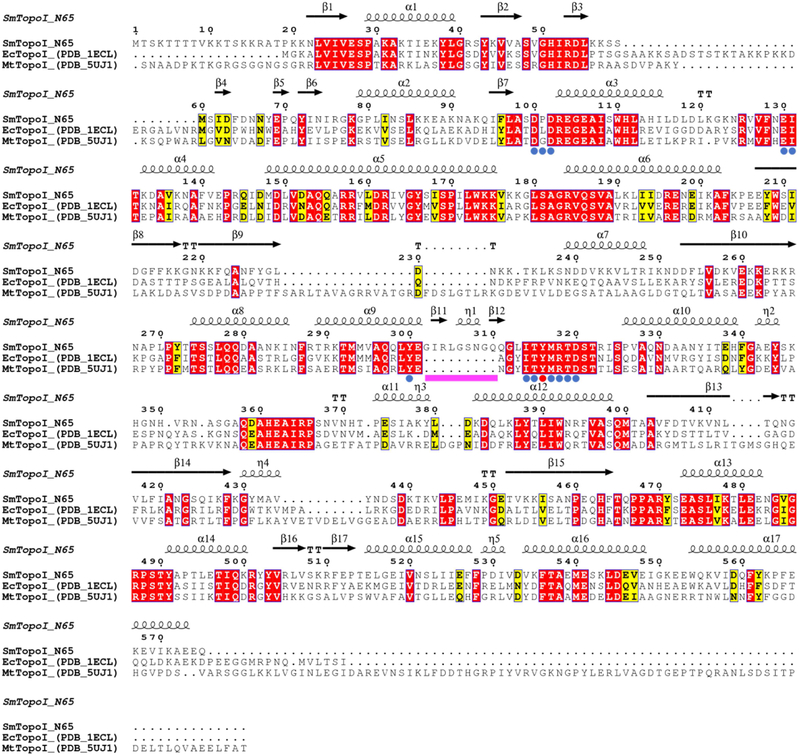

Figure 1. Multiple sequence alignment of SmTopoI_N65 and structural homologs.

Comparison of SmTopoI_N65, EcTopoI_N67, and MtTopoI via multiple sequence alignment shows high degree of sequence identity and similarity, including the highly conserved active site. Identical residues are highlighted in red, similar residues are highlighted in yellow, catalytic tyrosine is indicated with a red dot, active site residues within 5 Å from catalytic tyrosine are indicated with blue dots, and the nine-residue loop extension seen in SmTopoI_N65 is indicated with a magenta bar.

Sequence and structure alignments

SmTopoI_N65, EcTopoI_N67, and MtTopoI was generated with the ESPript 3 server (http://espript.ibcp.fr/) using a multiple protein sequence alignment produced with Clustal Omega, with secondary structure information extracted from the SmTopoI_N65 structure [25,26]. Residues within 5Å of the active site Y316 were determined with UCSF Chimera and the structure distances measurement tool [24]. Structural alignment of SmTopoI_N65 with EcTopoI_N67 (PDB 1ECL) and MtTopoI (PDB 5UJ1) conducted with UCSF Chimera MatchMaker structure comparison tool [13,17,24].

Results

Crystallization of SmTopoI_N65

As we reported previously, soluble full-length SmTopoI did not initially express well and, even after expression was optimized, its solubility required extremely high salt conditions not generally conducive to crystallization [15]. As such, full-length SmTopoI proved recalcitrant to crystallization and the C-terminal domain was rationally removed for subsequent crystallization trials. Iteratively shorter N-terminal fragment SmTopoI constructs corresponding to the original 67-kDa N-terminal EcTopoI (EcTopoI_N67) crystal structure (PDB 1ECL) [17,27] were cloned, expressed, purified, and screened for crystals. After multiple fragments were screened, this eventually proved successful as diffraction-quality crystals of the 65-kDa 575 residue SmTopoI fragment were attained, however the diffraction resolution was relatively low (greater than 4 Å). Upon fine grid screening and implementation of temperature trials, high-resolution quality crystals were grown (Figure S1), and the structure was determined.

Overall structure of SmTopoI_N65

The three-dimensional crystal structure of SmTopoI_N65 was determined to 2.06 Å via molecular replacement using the EcTopoI_N67 crystal structure (PDB 1ECL) as a model [17,27], followed by iterative cycles of model building and refinement (Table 1). A sequence alignment between SmTopoI_N65 and EcTopoI_N67, which share a 42.9% sequence identity, is shown (Figure 1). The root mean square deviation (RMSD) between the two structures is 1.83Å. Analysis of the crystal structure and Matthews Coefficient indicate that there is one monomeric SmTopoI_N65 molecule per asymmetric unit (Figure 2), as was expected [28–30]. The monomeric state of SmTopoI_N65 was further corroborated by PISA (Protein, Interface, Structures, and Assemblies) analysis [31]. Electron density of the hexa-histidine tag is not visible in the model, nor is density for the first leading 18 N-terminal residue peptide chain (M1 to T18), which exists as an additional N-term extension compared to EcTopoI, similar to the first 16 residues seen in MtTopoI (PDB 5UJ1) [13]. This unmodeled N-term peptide continues to be of unknown function. It carries substantial positive charge and is relatively polar, with five positively charged lysines and one positively charged arginine, as well as six polar uncharged threonines and two polar uncharged serines. The SmTopoI_N65 model begins at P19, with K21 of SmTopoI_N65 aligning with K3 of EcTopoI_N67. This represents the beginning of the highly conserved topoisomerase-primase (TOPRIM) domain, which ends at N129 and N140 of SmTopoI_N65 and EcTopoI_N67, respectively [32].

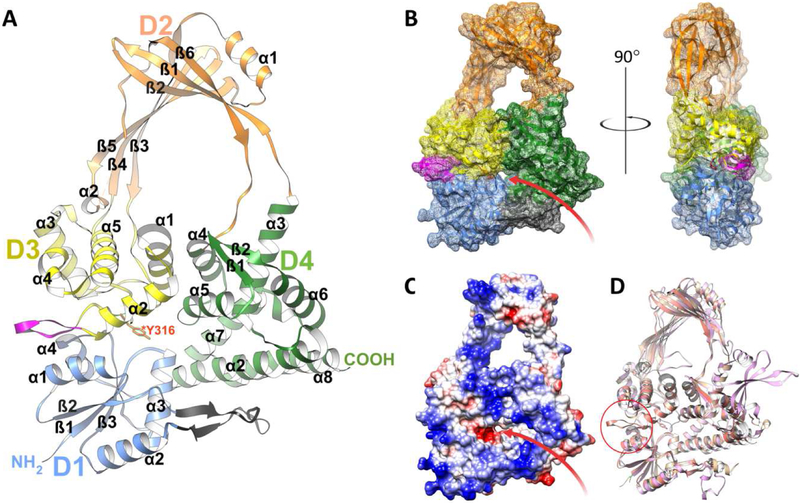

Figure 2. Overall structure of SmTopoI_N65.

A. Flat ribbon diagram of the overall structure of SmTopoI_N65 showcasing the four N-terminal domains that comprise the main body. D1, D2, D3, and D4 are colored in blue, orange, yellow, and green, respectively. Sub-domain secondary structures are also numbered respectively. The unique loop extension before and immediately adjacent to the active site in D3 between α2 and α3 is colored magenta. The small outcropping from D1 that is considered a part of D4 as in the EcTopoI and MtTopoI structures is colored charcoal. The catalytic Y316 residue in D3 is drawn in stick and colored red. B. Mesh surface diagram of SmTopoI_N65 with the same color and orientation as in A but turned on x axis by −10° for improved view of DNA binding site and groove, shown as a red arrow, with accompanying 90° turn along the y axis for profile view. C. Coulombic surface coloring showing electrostatic potential with standard red/negative and blue/positive coloring in the same orientation as B. The DNA binding site and groove is also shown with a red arrow. D. Structural alignment of SmTopoI_N65 with EcTopoI_N67 (1ECL) and MtTopoI (5UJ1) colored salmon, tan, and pink, respectively. Unique loop extension near active site of SmTopoI_N65 highlighted with red circle.

The SmTopoI_N65 model includes the first four domains of the overall structure, which comprise the main body core and show an intricate topology (Figure 2 and Figure S2) [33]. Domains D1, D3, and D4 form the base of the body, and D2 forms the bulk of the toroid arch that represents the hinge domain. D1 is comprised of four alpha helices and three beta strands. D2 is connected to D4 via a bridge of two flexible loops and is comprised overall of two alpha helices and six beta strands. D3 is comprised of five alpha helices, with a likelihood of α4 actually forming a 310 helix. The catalytic Y316 residue is also located within D3 on a loop between α2 and α3 at the interface of D1, D3, and D4. The remainder of the highly conserved active site surrounds the catalytic tyrosine residue.

While the SmTopoI_N65 fragment shares 42.9% sequence identity with the EcTopoI_N67 sequence, full-length SmTopoI shares 41.4% identity with full-length EcTopoI and 25.3% with full-length E. coli topo III, 37.1% identity with full-length MtTopoI, and 42.8% identity with full-length topo I from the thermophile T. maritima (TmTopoI). Of note, full-length SmTopoI shares 61.9% identity with the topo I enzyme from Staphylococcus aureus (SaTopoI), for which there is currently no determined three-dimensional structure [26].

Unique structural features of SmTopoI_N65

The SmTopoI_N65 model shows only 3 beta strands in D1, whereas EcTopoI and MtTopoI each contain four D1 beta strands. Within 5 Å from the catalytic center of Y316, only one dissimilar residue is observed between SmTopoI_N65 and EcTopoI_N67, found between the two aspartates on the DXD TOPRIM motif—that is, P101 on SmTopoI_N65, versus L112 on EcTopoI_N67. Interestingly, immediately prior to the conserved active site, SmTopo_N65 displays a unique nine residue loop extension (Figure 1 and Figure 2) not present in any of the topo I structures previously determined, except for a similar but non-identical extension seen in topo I from the extremophile Thermotoga maritima (PDB 2GAI; Figure S3). The SmTopoI_N65 loop extension is mainly polar, with polar uncharged residues S307, N308, Q310, and Q311. Further sequence alignment analysis of SmTopoI_N65 against several additional select bacteria shows an intriguing lack of this nine-residue extension in several prominent gut microbes, such as E. coli, Bacteroides ovatus, Bacteroides fragilis, and Bifidobacterium breve, while a similar extension exists not only in the thermophile T. maritima, but also in Staphylococcus aureus, Clostridioides difficile, and Neisseria gonorrhoeae (Figure S4). Lastly, as seen in MtTopoI, but dissimilar to EcTopoI_N67, SmTopoI_N65 lacks an equivalent α1 helix in D4.

Discussion

Because of the inherently conserved nature of topo I, SmTopoI_N65 exhibits a substantial degree of sequence identity and similarity with other previously determined topo I structures, including a highly conserved active site and similar overall structure. Therefore, any novel distinction at all among topo I homologues is likely of significant interest and, as such, the SmTopoI_N65 nine-residue extension located immediately N-term-adjacent to the active site is notably unique as this extension is not seen in topo I structures from either E. coli or M. tuberculosis. What may have gone previously overlooked as an insignificant structural variation in topo I from an extremophile that is inconsequential to human health (TmTopoI), the presence of this loop extension in S. mutans—a bacterium noted for both its utility in research as a gram-positive model organism and its significance in dental and cardiovascular health— stands as a structural dissimilarity that certainly draws attention and may warrant further analysis. Its proximity to the enzyme active site is indeed intriguing, and important questions regarding any underlying significance, including possible implications related to enzymatic efficiency, target DNA sequence selectivity or stabilization, or even the possibility of rationally designing selective catalytic topo I inhibitors that exploit partial engagement with the extension, remain unanswered.

Employing X-ray crystallographic methods, this work identifies conditions producing crystals that diffracted to 2.06 Å resolution, resulting in the first determined topo I structure from a gram-positive bacterium, SmTopoI_N65. This topo I fragment structure offers important insight into both the similarities and differences between bacterial topo I from several different relevant organisms. Continued efforts to characterize SmTopoI are still warranted, including but not limited to the structural determination of full-length SmTopoI, co-crystal structures with bound oligonucleotides, enzymatic and kinetic studies, as well as various studies focused on the relatively unique active-site-adjacent nine-residue loop extension highlighted in this work. Such studies regarding the latter topic may include studies deleting, extending, or mutating the loop itself, as well as side-by-side comparison of structural and enzymatic studies of topo I enzymes from various bacterial organisms, including those with and without the loop extension. Nonetheless, the results of these studies have improved our knowledge of topo I and will facilitate future rational research efforts targeting this important enzyme.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. SmTopoI_N65 crystals A.. Original SmTopoI_N65 crystals grown at 18°C from course JCSG plus screen, condition 1–5 (0.2 M magnesium formate dihydrate and 20% PEG 3350). B. Same crystal as in (A), but stained with a 1:1 mixture of Izit Crystal Dye (Hampton Research, Aliso Viejo, CA) and acid red dye. C. Optimized SmTopoI_N65 crystal grown in 0.2 M magnesium formate dihydrate and 25% PEG 3350 at 4°C used for structure determination.

Figure S2. SmTopoI_N65 topology diagram Topology diagram of SmTopoI_N65 created with PDBsum showing beta strands as pink arrows and alpha helices as red cylinders [33].

Figure S3. Structural alignment of SmTopoI_N65 and TmTopoI (PDB 2GUI) Structural alignment of SmTopoI_N65 (red) with topo I from the thermophile Thermotoga maritima, TmTopoI (PDB 2GUI; green) shown in flat ribbon format conducted with UCSF Chimera MatchMaker structure comparison tool [12,24]. The unique loop extension near the active site is highlighted with a red circle and the catalytic Y316 residue on SmTopoI_N65 if shown in stick format.

Figure S4. SmTopoI_N65 multiple sequence alignment with select topo I homologs of undetermined structure Comparison of SmTopoI_N65 with homologs from various select bacteria, including E. coli, M. tuberculosis, T. maritima, S. aureus, C. difficile, N. gonorrhoeae, B. ovatus, B. fragilis, and B. breve via multiple sequence alignment. Sequence alignment was generated with the ESPript 3 server (http://espript.ibcp.fr/) using a multiple protein sequence alignment produced with Clustal Omega, with secondary structure information extracted from the SmTopoI_N65 structure [12,13,17,25,26]. Alignment shows high degree of sequence identity and similarity, including the highly conserved active site. Identical residues are highlighted in red, similar residues are highlighted in yellow, catalytic tyrosine is indicated with a red dot, active site residues within 5 Å from catalytic tyrosine are indicated with blue dots, and the nine-residue loop extension seen in SmTopoI_N65 is indicated with a magenta bar.

Highlights.

A high-resolution structure of an amino terminal fragment of topoisomerase I from S. mutans has been determined.

The structure is the first topoisomerase I structure from a gram-positive bacterium.

The structure displays a highly conserved active site.

The structure shows a unique loop extension adjacent to the active site.

Acknowledgements

We wish to acknowledge and thank the CCP4/APS School in Macromolecular Crystallography 2018 for assistance with data collection through refinement. Molecular graphics and analyses performed with UCSF Chimera, developed by the Resource for Biocomputing, Visualization, and Informatics at the University of California, San Francisco, with support from NIH P41-GM103311. The graphical abstract was created with BioRender. This research was made possible by the American Foundation for Pharmaceutical Education, Pre-Doctoral Award in Pharmaceutical Sciences. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the American Foundation for Pharmaceutical Education.

Funding Sources

Funding was provided by a pilot grant from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (5 U54 GM104944). Additional funding was received from the Idaho State University (ISU), Office of Research and Economic Development, Faculty Seed Grant Program and the ISU, College of Pharmacy. This research was also made possible by the Center for Pediatric Experimental Therapeutics (CPET) via financial support to JAJ as a CPET scholar. Funding sources were not involved in study design.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Description of supplementary material: SmTopoI_N65 protein crystal figure, SmTopoI_N65 topology diagram, structural alignment of SmTopoI_N65 with topoisomerase I from the thermophile Thermotoga maritima, and an additional SmTopoI_N65 multiple sequence alignment with select homologs of undetermined structure. The preliminary validation report is also included.

References

- [1].Pommier Y, Drugging topoisomerases: lessons and challenges, ACS Chem. Biol 8 (2013) 82–95. 10.1021/cb300648v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Viard T, de la Tour CB, Type IA topoisomerases: a simple puzzle?, Biochimie 89 (2007) 456–467. 10.1016/j.biochi.2006.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Forterre P, Gribaldo S, Gadelle D, Serre MC, Origin and evolution of DNA topoisomerases, Biochimie 89 (2007) 427–446. 10.1016/j.biochi.2006.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Mayer C, Janin YL, Non-quinolone inhibitors of bacterial type IIA topoisomerases: a feat of bioisosterism, Chem. Rev 114 (2014) 2313–2342. 10.1021/cr4003984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Nimesh H, Sur S, Sinha D, Yadav P, Anand P, Bajaj P, Virdi JS, Tandon V, Synthesis and biological evaluation of novel bisbenzimidazoles as Escherichia coli topoisomerase IA inhibitors and potential antibacterial agents, J. Med. Chem 57 (2014) 5238–5257. 10.1021/jm5003028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Tse-Dinh YC, Bacterial topoisomerase I as a target for discovery of antibacterial compounds, Nucleic Acids Res. 37 (2009) 731–737. 10.1093/nar/gkn936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Liu IF, Sutherland JH, Cheng B, Tse-Dinh YC, Topoisomerase I function during Escherichia coli response to antibiotics and stress enhances cell killing from stabilization of its cleavage complex, J. Antimicrob. Chemother 66 (2011) 1518–1524. 10.1093/jac/dkr150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Stockum A, Lloyd RG, Rudolph CJ, On the viability of Escherichia coli cells lacking DNA topoisomerase I, BMC Microbiol. 12 (2012) 26 10.1186/1471-2180-12-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Garcia MT, Blazquez MA, Ferrandiz MJ, Sanz MJ, Silva-Martin N, Hermoso JA, de la Campa AG, New alkaloid antibiotics that target the DNA topoisomerase I of Streptococcus pneumoniae, J. Biol. Chem 286 (2011) 6402–6413. 10.1074/jbc.M110.148148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Strahs D, Zhu CX, Cheng B, Chen J, Tse-Dinh YC, Experimental and computational investigations of Ser10 and Lys13 in the binding and cleavage of DNA substrates by Escherichia coli DNA topoisomerase I, Nucleic Acids Res. 34 (2006) 1785–1797. 10.1093/nar/gkl109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Tan K, Zhou Q, Cheng B, Zhang Z, Joachimiak A, Tse-Dinh YC, Structural basis for suppression of hypernegative DNA supercoiling by E. coli topoisomerase I, Nucleic Acids Res. 43 (2015) 11031–11046. 10.1093/nar/gkv1073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Hansen G, Harrenga A, Wieland B, Schomburg D, Reinemer P, Crystal structure of full length topoisomerase I from Thermotoga maritima, J. Mol. Biol 358 (2006) 1328–1340. 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Tan K, Cao N, Cheng B, Joachimiak A, Tse-Dinh YC, Insights from the Structure of Mycobacterium tuberculosis Topoisomerase I with a Novel Protein Fold, J. Mol. Biol 428 (2016) 182–193. 10.1016/j.jmb.2015.11.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Lemos JA, Quivey RG Jr., Koo H, Abranches J, Streptococcus mutans: a new Gram-positive paradigm?, Microbiology 159 (2013) 436–445. 10.1099/mic.0.066134-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Jones JA, Price E, Miller D, Hevener KE, A simplified protocol for high-yield expression and purification of bacterial topoisomerase I, Protein Expr. Purif 124 (2016) 32–40. 10.1016/j.pep.2016.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Studier FW, Stable expression clones and auto-induction for protein production in E. coli, Methods Mol. Biol 1091 (2014) 17–32. 10.1007/978-1-62703-691-7_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Lima CD, Wang JC, Mondragon A, Three-dimensional structure of the 67K N-terminal fragment of E. coli DNA topoisomerase I, Nature 367 (1994) 138–146. 10.1038/367138a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Otwinowski Z, Minor W, Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode, Macromolecular Crystallography, Pt A 276 (1997) 307–326. Doi 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Cowtan K, The Buccaneer software for automated model building. 1. Tracing protein chains, Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr 62 (2006) 1002–1011. 10.1107/S0907444906022116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Adams PD, Afonine PV, Bunkoczi G, Chen VB, Davis IW, Echols N, Headd JJ, Hung LW, Kapral GJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, McCoy AJ, Moriarty NW, Oeffner R, Read RJ, Richardson DC, Richardson JS, Terwilliger TC, Zwart PH, PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution, Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr 66 (2010) 213–221. 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, Cowtan K, Features and development of Coot, Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr 66 (2010) 486–501. 10.1107/S0907444910007493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Joosten RP, Salzemann J, Bloch V, Stockinger H, Berglund AC, Blanchet C, Bongcam-Rudloff E, Combet C, Da Costa AL, Deleage G, Diarena M, Fabbretti R, Fettahi G, Flegel V, Gisel A, Kasam V, Kervinen T, Korpelainen E, Mattila K, Pagni M, Reichstadt M, Breton V, Tickle IJ, Vriend G, PDB_REDO: automated re-refinement of X-ray structure models in the PDB, J. Appl. Crystallogr 42 (2009) 376–384. 10.1107/S0021889809008784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Chen VB, Arendall WB 3rd, Headd JJ, Keedy DA, Immormino RM, Kapral GJ, Murray LW, Richardson JS, Richardson DC, MolProbity: all-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography, Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr 66 (2010) 12–21. 10.1107/S0907444909042073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Pettersen EF, Goddard TD, Huang CC, Couch GS, Greenblatt DM, Meng EC, Ferrin TE, UCSF Chimera--a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis, J. Comput. Chem 25 (2004) 1605–1612. 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Robert X, Gouet P, Deciphering key features in protein structures with the new ENDscript server, Nucleic Acids Res. 42 (2014) W320–324. 10.1093/nar/gku316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Madeira F, Park YM, Lee J, Buso N, Gur T, Madhusoodanan N, Basutkar P, Tivey ARN, Potter SC, Finn RD, Lopez R, The EMBL-EBI search and sequence analysis tools APIs in 2019, Nucleic Acids Res. (2019). 10.1093/nar/gkz268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Lima CD, Wang JC, Mondragon A, Crystallization of a 67 kDa fragment of Escherichia coli DNA topoisomerase I, J. Mol. Biol 232 (1993) 1213–1216. 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Matthews BW, Solvent content of protein crystals, J. Mol. Biol 33 (1968) 491–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Kantardjieff KA, Rupp B, Matthews coefficient probabilities: Improved estimates for unit cell contents of proteins, DNA, and protein-nucleic acid complex crystals, Protein Sci. 12 (2003) 1865–1871. 10.1110/ps.0350503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Weichenberger CX, Rupp B, Ten years of probabilistic estimates of biocrystal solvent content: new insights via nonparametric kernel density estimate, Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr 70 (2014) 1579–1588. 10.1107/S1399004714005550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Krissinel E, Henrick K, Inference of macromolecular assemblies from crystalline state, J. Mol. Biol 372 (2007) 774–797. 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Aravind L, Leipe DD, Koonin EV, Toprim--a conserved catalytic domain in type IA and II topoisomerases, DnaG-type primases, OLD family nucleases and RecR proteins, Nucleic Acids Res. 26 (1998) 4205–4213. 10.1093/nar/26.18.4205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].de Beer TA, Berka K, Thornton JM, Laskowski RA, PDBsum additions, Nucleic Acids Res. 42 (2014) D292–296. 10.1093/nar/gkt940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. SmTopoI_N65 crystals A.. Original SmTopoI_N65 crystals grown at 18°C from course JCSG plus screen, condition 1–5 (0.2 M magnesium formate dihydrate and 20% PEG 3350). B. Same crystal as in (A), but stained with a 1:1 mixture of Izit Crystal Dye (Hampton Research, Aliso Viejo, CA) and acid red dye. C. Optimized SmTopoI_N65 crystal grown in 0.2 M magnesium formate dihydrate and 25% PEG 3350 at 4°C used for structure determination.

Figure S2. SmTopoI_N65 topology diagram Topology diagram of SmTopoI_N65 created with PDBsum showing beta strands as pink arrows and alpha helices as red cylinders [33].

Figure S3. Structural alignment of SmTopoI_N65 and TmTopoI (PDB 2GUI) Structural alignment of SmTopoI_N65 (red) with topo I from the thermophile Thermotoga maritima, TmTopoI (PDB 2GUI; green) shown in flat ribbon format conducted with UCSF Chimera MatchMaker structure comparison tool [12,24]. The unique loop extension near the active site is highlighted with a red circle and the catalytic Y316 residue on SmTopoI_N65 if shown in stick format.

Figure S4. SmTopoI_N65 multiple sequence alignment with select topo I homologs of undetermined structure Comparison of SmTopoI_N65 with homologs from various select bacteria, including E. coli, M. tuberculosis, T. maritima, S. aureus, C. difficile, N. gonorrhoeae, B. ovatus, B. fragilis, and B. breve via multiple sequence alignment. Sequence alignment was generated with the ESPript 3 server (http://espript.ibcp.fr/) using a multiple protein sequence alignment produced with Clustal Omega, with secondary structure information extracted from the SmTopoI_N65 structure [12,13,17,25,26]. Alignment shows high degree of sequence identity and similarity, including the highly conserved active site. Identical residues are highlighted in red, similar residues are highlighted in yellow, catalytic tyrosine is indicated with a red dot, active site residues within 5 Å from catalytic tyrosine are indicated with blue dots, and the nine-residue loop extension seen in SmTopoI_N65 is indicated with a magenta bar.