Abstract

Background

Osimertinib exhibits good efficacy in patients with T790M-positive non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and acquired resistance to epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)-tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs). Compared with the clinical trials, in real-world clinical practice, osimertinib must be administered to older patients and those with poor Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG-PS). Therefore, we investigated the association between osimertinib efficacy/safety and PS score, age, and other clinical features in patients with T790M-positive NSCLC.

Methods

We reviewed all patients with T790M-positive NSCLC and acquired resistance to initial EGFR-TKIs who were administered osimertinib between March 2016 and January 2018 at the Tokyo Metropolitan Cancer and Infectious Diseases Center in Komagome Hospital, Japan.

Results

In total, 31 patients, including 8 young (<65 years) and 23 elderly (≥65 years) patients, were included in the study. Of these, 10 (32.3%) patients had poor PS scores. The progression-free survival (PFS) was significantly shorter in young patients was than elderly patients [3.5 vs. 6.4 months, P=0.041; hazard ratio (HR), 2.41]. The overall survival (OS) of the young patients tended to be shorter than that of the elderly patients (5.3 vs. 19.4 months, P=0.067; HR, 2.58). The PFS (9.1 vs. 5.5 months; P=0.071; HR, 0.38) and the OS (not reached vs. 6.6 months, P=0.061; HR, 0.39) were shorter in patients with poor ECOG-PS than those with good ECOG-PS. The toxic effects of osimertinib were manageable. By multivariate analysis, both age and ECOG-PS were independent predictors of osimertinib efficacy.

Conclusions

Poor ECOG-PS and younger age were associated with lower efficacy of osimertinib in T790M-positive NSCLC.

Keywords: Lung cancer, epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), Threonine790Methionine, osimertinib, EGFR-TKI

Introduction

Lung cancer is one of the most common malignant diseases in the world. First- (gefitinib and erlotinib) and second-generation (afatinib and dacomitinib) epidermal growth factor receptor-tyrosine kinase inhibitors (EGFR-TKIs) benefit patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) harboring sensitive mutations and dramatically improve survival (1-5). However, almost all tumors with sensitive mutations acquire resistance to first- or second-generation EGFR-TKIs in approximately 1 year (6). Several mechanisms of the resistance to EGFR-TKIs were reported in the literature (7), and the most common mechanism of resistance to first- and second-generation EGFR-TKI is the mutation of threonine 790 to methionine (T790M).

Osimertinib is a third-generation irreversible EGFR-TKI. Preclinical studies demonstrated that osimertinib inhibited NSCLCs with sensitive mutations as well as those with the T790M resistance mutation (7,8). An international phase III trial, AURA3, showed that osimertinib was superior to platinum-doublet chemotherapy in patients with T790M-positive NSCLC with acquired resistance to first- or second-generation EGFR-TKIs (9). Therefore, osimertinib is considered as a treatment option for T790M-positive NSCLC.

However, real world data are necessary to determine the treatment sequence because of the restricted inclusion criteria that are used in clinical trials. For example, in a clinical trial, only patients with good Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG-PS) were administered osimertinib, whereas osimertinib is initiated in older patients and those with worse ECOG-PS in real-world clinical settings, compared with the clinical trials. In a study, younger patients who were positive for EGFR mutations and received first- or second-generation EGFR-TKIs exhibited worse prognosis than older patients (10). In another study, poor ECOG-PS and smoking index were predictors of poor overall survival (OS) in patients with advanced NSCLC harboring an activating EGFR mutation and receiving gefitinib as the first-line treatment (11). However, no studies investigated the impact of age, ECOG-PS, or other clinical variables on outcomes in patients with T790M-positive NSCLC who were initiated on osimertinib.

Therefore, we aimed to investigate the efficacy and safety of osimertinib in T790M-positive NSCLC in a real-world setting and evaluated the impact of age, ECOG-PS, and other clinical features on the outcomes of osimertinib treatment to determine the optimal treatment options for patients with T790M-positive NSCLC. This was a single-center retrospective study conducted at the Tokyo Metropolitan Cancer and Infectious Diseases Center in Komagome Hospital, Japan.

Methods

Patients and clinical features

We reviewed the clinical records of all patients with T790M-positive NSCLC and acquired resistance to first- or second-generation EGFR-TKIs who were administered osimertinib therapy between March 2016 and January 2018 at the Tokyo Metropolitan Cancer and Infectious Diseases Center in Komagome Hospital, Japan. Data related to the following variables in addition to ECOG-PS and age were extracted to confirm their association with ECOG-PS and age as confounding factors: sex, smoking history, histology, type of EGFR mutation detected at first biopsy, initial EGFR-TKI therapy, type of repeat-biopsy sample for detection of the T790M mutation (tissue or liquid biopsy sample), central nervous system (CNS) metastasis, osimertinib sequence, platinum-doublet chemotherapy administered prior to or after osimertinib, and the pattern of first- or second-generation EGFR-TKI resistance. We defined patients ≥65 years of age as elderly and those <65 years as young based on the AURA3 trial that used similar cut-off ages in subset analysis (9). An ECOG-PS score of 0–1 was considered as a good ECOG-PS, whereas and ECOG-PS 2–4 was considered as a poor ECOG-PS. We defined patients who received osimertinib as fourth-line treatment as late-line patients and those treated with osimertinib before the third line as early-line patients. We compared the clinical features between the two groups. Our study followed the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki recommendations and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Tokyo Metropolitan Cancer and Infectious Diseases Centre in Komagome Hospital.

Treatment and evaluation

Before initiation of osimertinib, Cobas EGFR mutation test kit version 2 provided by Roche Diagnostics K.K. in Tokyo, Japan was used for the detection of T790M mutation in tissue biopsy samples in all patients and the detection of T790M mutation in liquid biopsy samples for 20 patients. The SCORPION ARMS method was used to detect the T790M mutation in the liquid biopsy sample from one patient.

All patients underwent computed tomography of the chest and abdomen and magnetic resonance imaging or computed tomography of the head for staging before the first EGFR-TKI treatment, and osimertinib was initiated within one month. Whole-body bone scintigraphy or positron emission tomography was conducted, if necessary. All patients were initiated on osimertinib (80 mg once daily). All patients underwent computed tomography of the chest and abdomen every 2–3 months for the assessment of treatment efficacy. Magnetic resonance imaging or computed tomography of the head and whole-body bone scintigraphy or positron emission tomography scan were conducted, if necessary.

Efficacy and safety

The overall response rate (ORR), progression-free survival (PFS), and OS post-osimertinib treatment were compared between the two groups of patients classified by age (≥65 versus <65 years) and ECOG-PS (poor vs. good) in order to assess the impact of age and ECOG-PS. Objective tumor response was assessed using the response evaluation criteria in solid tumors guidelines version 1.1 (12). Progression patterns of osimertinib treatment were compared between the groups categorized by age and ECOG-PS.

Adverse events were assessed using the common terminology criteria for adverse events version 4.03. We compared adverse events and reduction or discontinuation of osimertinib due to adverse events between the groups categorized by age and ECOG-PS.

Statistical analysis

Patient characteristics were compared between the groups categorized by age and ECOG-PS using Fisher’s exact test or the Mann-Whitney U test. PFS and OS were assessed using the Kaplan-Meier method and the log-rank test. The prognostic value of clinical factors was assessed using the Cox regression method for univariate and multivariate analyses of PFS and OS. All statistical analyses were performed using EZR (Saitama Medical Centre, Jichi Medical University, Saitama, Japan), a graphical user interface for R (a modified R commander designed for biostatistics). P values <0.05 were considered to indicate significance of between-group differences in all statistical analyses.

Results

Patient characteristics

Table 1 shows the patient characteristics. A total of 31 patients, including 23 (74.2%) elderly and 8 (25.8%) young patients, were enrolled in this study. The median ages of the entire cohort, young patients, and elderly patients were 72, 54, and 75 years, respectively. In this study cohort, 10 (32.3%) patients with poor ECOG-PS were initiated on osimertinib. In the study cohort, there was a tendency for patients to be female and never-smokers than to be male and past or current smokers. These were similar tendency with the historical data of EGFR mutation-positive patients (11). Histopathological diagnosis was adenocarcinoma of all specimens. Gefitinib, erlotinib, and afatinib were administered in 24 (77.4%), 5 (16.1%), and 2 (6.5%) patients, respectively, as the first EGFR-TKI treatment. Furthermore, 19 (61.3%) patients showed exon 19 deletion, and 10 (32.3%) patients had L858R as the EGFR mutation before first EGFR-TKI treatment. Additionally, two patients had an uncommon or a compound mutation, including one patient with exon 18 G719S point mutation and one patient with exon 19 deletion and exon 18 G719X point mutation. In 12 (38.7%) patients, T790M was detected by tissue biopsy. In 21 (67.7%) patients, T790M was detected by liquid biopsy. Furthermore, 14 (45.2%) patients had CNS metastases at the time of osimertinib initiation. No significant between-group differences in clinical features were observed between the young and the elderly groups. The patients with poor ECOG-PS were older than those with good ECOG-PS. The patients with good ECOG-PS received platinum-doublet chemotherapy more frequently than those with poor ECOG-PS. Furthermore, CNS metastases were more frequent in patients with good ECOG-PS than those with poor ECOG-PS.

Table 1. Patient characteristics.

| Variable | Total, n (%) | Age | PS | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Young patients, n (%) | Elderly patients, n (%) | P value | 0–1, n (%) | 2–4, n (%) | P value | |||

| Subjects | 31 | 8 (25.8) | 23 (74.2) | 21 (67.7) | 10 (32.3) | |||

| Median age [range] | 72 [34–88] | 54 [34–64] | 75 [65–88] | 0.0001 | 70 [34–84] | 70.5 [51–88] | 0.028 | |

| Sex | 0.64 | 0.21 | ||||||

| Male | 7 (22.6) | 1 (12.5) | 6 (26.1) | 4 (19.0) | 3 (30.0) | |||

| Female | 24 (77.4) | 7 (87.5) | 17 (73.9) | 17 (81.0) | 7 (70.0) | |||

| ECOG-PS | 0.22 | |||||||

| 0–1 | 21 (67.7) | 7 (87.5) | 14 (60.9) | – | – | |||

| 2–4 | 10 (32.3) | 1 (12.5) | 9 (39.1) | – | – | |||

| Smoking history | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Never smoker | 21 (67.7) | 5 (62.5) | 16 (69.6) | 14 (66.7) | 7 (70.0) | |||

| Ever or current smoker | 10 (32.3) | 3 (37.5) | 7 (30.4) | 7 (33.3) | 3 (30.0) | |||

| Previous therapy | ||||||||

| First EGFR-TKI treatment | 0.15 | 0.51 | ||||||

| Gef | 24 (77.4) | 5 (62.5) | 19 (82.6) | 15 (71.4) | 9 (90.0) | |||

| Erl | 5 (16.1) | 3 (37.5) | 2 (8.7) | 4 (19.0) | 1 (10.0) | |||

| Afa | 2 (6.5) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (8.7) | 2 (9.5) | 0 (0.0) | |||

| Platinum doublet | 1 | 0.015 | ||||||

| Yes | 22 (71.0) | 6 (75.0) | 16 (51.6) | 18 (85.7) | 4 (40.0) | |||

| No | 9 (29.0) | 2 (25.0) | 7 (30.4) | 3 (14.3) | 6 (60.0) | |||

| Median osimertinib sequence [range] | 3 [2–7] | 4 [2–5] | 3 [2–7] | 0.32 | 3 [2–7] | 2.5 [2–7] | 0.54 | |

| Mutation type | 0.67 | 0.59 | ||||||

| Ex19del | 19 (61.3) | 4 (50.0) | 15 (65.2) | 14 (66.7) | 5 (50.0) | |||

| L858R | 10 (32.3) | 4 (50.0) | 6 (26.1) | 6 (28.6) | 4 (40.0) | |||

| Others | 2 (6.5) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (8.7) | 1 (4.8) | 1 (10.0) | |||

| T790M detection sample | 0.68 | 0.27 | ||||||

| Tissue | 12 (38.7) | 2 (25.0) | 10 (43.5) | 6 (28.6) | 6 (60.0) | |||

| Liquid | 21 (67.7) | 6 (75.0) | 15 (65.2) | 15 (71.4) | 6 (60.0) | |||

| Both | 2 (6.5) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (8.7) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (20.0) | |||

| CNS metastasis | 0.41 | 0.0089 | ||||||

| Yes | 14 (45.2) | 5 (62.5) | 9 (39.1) | 13 (61.9) | 1 (10.0) | |||

| No | 17 (54.8) | 3 (37.5) | 14 (60.9) | 8 (38.1) | 9 (90.0) | |||

PS, performance status; EGFR-TKI, epidermal growth factor receptor-tyrosine kinase inhibitor; CNS, central nervous system.

Treatment efficacy and safety

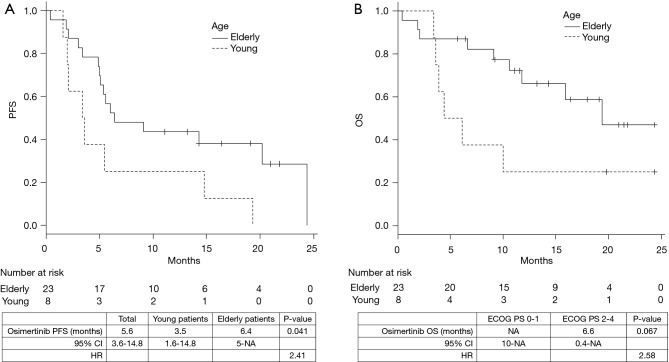

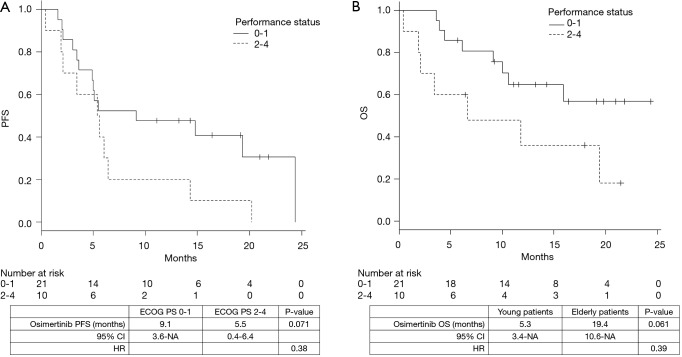

The median duration of follow-up was 12 months. The median PFS and OS were 5.6 [95% confidence interval (CI), 3.6–14.8] and 19.4 (95% CI, 9.1–not achieved) months, respectively. The PFS of young patients was significantly shorter than that of the elderly patients [3.5 vs. 6.4 months, P=0.041; hazard ratio (HR), 2.41] (Figure 1A). The OS was shorter in the young patients than the elderly patients; however, the difference was not statistically significant (5.3 vs. 19.4 months, P=0.067; HR, 2.58) (Figure 1B). Similarly, the PFS (9.1 vs. 5.5 months, P=0.071; HR, 0.38) and the OS (not reached vs. 6.6 months, P=0.061; HR, 0.39) of the patients with poor ECOG-PS were shorter than those of the patients with good ECOG-PS; however, the between-group differences were not statistically significant (Figure 2A,B). The total ORR was 53.3%, which was not significantly different between the groups categorized according to age or ECOG-PS (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Impact of age. Progression-free survival (A) and overall survival (B) of patients with T790M-positive non-small cell lung cancer treated with osimertinib.

Figure 2.

Impact of performance status. Progression-free survival (A) and overall survival (B) of patients with T790M-positive non-small cell lung cancer treated with osimertinib.

Table 2. Efficacy and safety of osimertinib treatment.

| Variable | Total | Age | ECOG PS | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Young patients | Elderly patients | P value | 0–1 | 2–4 | P value | |||

| Subjects | 31 | 8 | 23 | 21 | 10 | |||

| Osimertinib response | ||||||||

| CR | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |||

| PR | 15 | 3 | 12 | 8 | 7 | |||

| SD | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | |||

| PD | 5 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 0 | |||

| NE | 7 | 1 | 6 | 5 | 2 | |||

| ORR (%) | 53.3 | 37.5 | 56.5 | 0.43 | 42.9 | 70 | 0.25 | |

| AEs ≥ Grade 3 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 1 | |||

| ILD | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Dose reduction | 6 | 1 | 5 | 5 | 1 | |||

| Discontinuation | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | |||

| Site of progression disease | ||||||||

| Primary | 5 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 2 | |||

| CNS | 5 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 0 | |||

| Pleural or pericardial effusion | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Others | 8 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 3 | |||

| Post osimertinib therapy line | 0.34 | 1 | ||||||

| 0 | 24 | 5 | 19 | 16 | 8 | |||

| 1 | 7 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 2 | |||

PS, performance status; ORR, overall response rate; ILD, interstitial lung disease; CR, complete response; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease; PD, progressive disease; NE, not evaluated; CNS, central nervous system.

The treatment toxicity was manageable in most patients. Severe adverse events above grade 3 occurred in 3 (10%) patients, and interstitial lung disease (ILD) occurred in two elderly patients. While there were no adverse events of grade 5 including ILD, six patients required dose reduction, whereas, osimertinib had to be discontinued because of toxicity in three patients. No significant between-group differences in adverse events were observed based on age or ECOG-PS (Table 2).

Disease progression was observed in 20 patients. New CNS metastases occurred in five patients in the good ECOG-PS group. However, the sites of disease progression were not significantly different between the groups based on age or ECOG-PS. Furthermore, there were no significant differences in the number of patients who initiated post-osimertinib therapy between the groups based on age or ECOG-PS (Table 2).

Univariate and multivariate analyses of clinical features

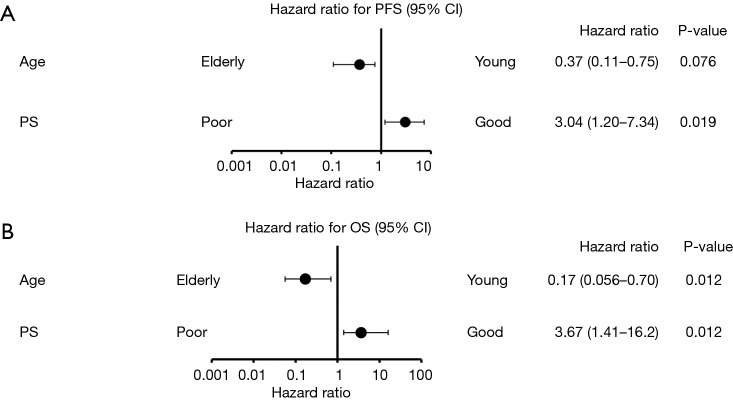

Other than age and ECOG-PS, a previous report identified sex, smoking history, T790M mutation detected by liquid biopsy, and CNS metastasis as clinical features that were associated with prognosis of patients receiving EGFR-TKI treatment (11,13-15). Figure 3 shows the results of our univariate analysis including ECOG-PS and age in PFS and OS as forest plots. Our analysis revealed that only age and ECOG-PS were associated with prognosis of patients with T790M-positive NSCLC receiving osimertinib.

Figure 3.

Univariate analysis of associations between outcomes and clinical features. PFS, progression-free survival; OS, overall survival; CNS, central nervous system.

By univariate analysis, we identified ECOG-PS and age as the only clinical features that were associated significantly with the prognosis of patients on osimertinib therapy. On multivariate analysis, both age and ECOG-PS were independent predictors of osimertinib treatment efficacy (Figure 4). Therefore, poor ECOG-PS and young age were identified as predictors of low osimertinib efficacy in the current study.

Figure 4.

Multivariate analysis of associations between outcomes and age or performance status. PFS, progression-free survival; OS, overall survival.

Discussion

The current study based on real-world data of patients with T790M-positive NSCLC who were initiated on osimertinib revealed that age and ECOG-PS were associated with the efficacy of osimertinib. The PFS and OS in patients on osimertinib therapy in the current study were shorter than those reported previously (9,16,17), which might be attributed to the initiation of osimertinib in patients with worse ECOG-PS compared to the previous studies. In a prospective phase III trial of osimertinib as the third-line treatment for T790M-mutated NSCLC, patients with an ECOG-PS score of 2 showed good PFS (10.2 months); however, that trial recruited patients with ECOG-PS scores of 0–1, with only 6.8% of the patients with an ECOG-PS score of 2 (18). Initiation of gefitinib in patients with poor ECOG-PS harboring contraindications for chemotherapy showed satisfactory tumor response and efficacy. Similarly, a case report documented a patient with poor ECOG-PS who showed improvement with osimertinib. However, patients with poor ECOG-PS, albeit demonstrating good response to osimertinib, showed shorter PFS and OS after osimertinib initiation in the current study. Generally, a poor ECOG-PS is considered a prognostic factor in patients with NSCLC. Therefore, the current study results suggest poor ECOG-PS as a prognostic factor in patients initiated on osimertinib.

Our findings may provide important insights on the sequence of treatment approaches using EGFR-TKIs. The results of the AURA3 trial demonstrated that osimertinib improved prognosis of patients with T790M-positive NSCLC with acquired resistance to first- or second-generation EGFR-TKIs. However, an additional T790M mutation occurred only in 60% of the patients who were administered first- or second-generation EGFR-TKIs. Conversely, osimertinib exhibited high activity in the presence of common mutations in preclinical studies. Therefore, in the FLAURA study, untreated patients with EGFR-mutated advanced NSCLC initiated on osimertinib showed longer PFS and higher response rate compared to patients who received gefitinib (19). However, there is no conclusive evidence for the EGFR-TKI sequence because the data on OS is not available for the FLAURA trial, and dacomitinib as second-generation EGFR-TKI showed longer PFS and OS than gefitinib in ARCHER1050, an international phase III randomized trial (5). In addition, patients with poor ECOG-PS were excluded from these two prospective trials. In the subset analysis of a prospective trial, gefitinib showed good PFS (6.5 months) and ORR (66%) (1). The current study results suggest that the first-generation EGFR-TKIs that should be initiated on untreated patients with NSCLC patients and poor ECOG-PS should be elucidated further in future prospective randomized trials.

Although many patients in the current study had a poor ECOG-PS score, the incidence of adverse events was relatively low, and few patients required discontinuation or reduction of osimertinib due to adverse events. ILD occurred in only two elderly Japanese patients. In a previous study, first-line EGFR-TKI therapy in elderly patients was associated with ILD (20). In a sub-group analysis of data from the AURA3 trial, ILD occurred in 7.3% of Japanese patients (16). Although the number of more elderly Japanese patients in the current study was higher than those in previous prospective studies, the frequency of ILD was comparable. The current study revealed that adverse events with osimertinib in a real-world setting were manageable.

Few studies investigated the impact of age on EGFR-TKI treatment, with inconsistent results. One prospective study showed that the efficacy and safety of erlotinib were comparable between elderly and younger patients (21). One retrospective study found that EGFR-TKI exhibited poor efficacy in patients >75 years of age (22). One meta-analysis investigating the relationship of age and the EGFR-TKIs gefitinib, erlotinib, and afatinib (23) showed no differences in EGFR-TKIs efficacy between patients aged >65 years and those aged ≤65 years. In another study, the efficacy of first- or second-generation EGFR-TKIs was better in elderly patients with NSCLC than those aged <50 years. These studies involving first- or second-generation EGFR-TKIs (10) suggest that EGFR-TKI treatment exhibited low efficacy in relatively young patients with EGFR mutation-positive lung cancer.

The mechanism underlying poor efficacy of EGFR-TKIs in young patients is not known. Previous studies demonstrated that uncommon mutations are more frequent in young patients. According to Wu et al., the high frequency of uncommon mutations may explain the relatively poor prognosis of young patients treated with first-generation EGFR-TKIs (5). Although patients enrolled in the current study with the exception of two patients had common mutations, we observed a relatively poor efficacy of first- or second-generation EGFR-TKIs as well as osimertinib in the young patients compared with the elderly patients. Some studies found an association of tumor heterogeneity with EGFR-TKI resistance and osimertinib efficacy (24). The present study showed no differences in the clinical characteristics and patterns of disease progression between the groups according to age. Osimertinib was shown to be effective in patients with some uncommon mutations (9,25). Initial EGFR-TKI treatment is expected to impact the efficacy of osimertinib against uncommon mutations because afatinib was shown to exhibit an antitumor effect against uncommon mutations. However, in the current study, most patients were administered gefitinib as the first EGFR-TKI treatment, and initial EGFR-TKI had minimal effect on osimertinib efficacy. Furthermore, in the current cohort, there were few clinical characteristics that were different between the young and elderly patients. Although seven of the eight young patients had a good ECOG-Ps, younger patients had worse outcomes in the current study. We consider that the difference in the response rate simply reflected the difference in the antitumor effect of osimertinib between the young and elderly patients. Therefore, our results suggest that molecular or clinical mechanisms other than uncommon mutations might be responsible for the low efficacy of osimertinib or other EGFR-TKIs in younger patients.

Interestingly, TP53 mutations were detected more frequently in young patients compared with elderly patients in lung cancer (26). A study previously reported that TP53 mutations reduced responsiveness to first-line EGFR-TKI treatment (27). Genetic tumor heterogeneity caused by mutations in TP53 or other genes might be associated with poor efficacy of EGFR-TKIs treatment in younger patients in the current study. However, the TP53 mutation status was not known in the current study population, and these considerations remain as hypotheses. Future studies should explore these mechanisms and assess the association between osimertinib efficacy and the type of EGFR-TKI administered as the initial treatment to elucidate the optimal sequence of EGFR-TKIs for the treatment of younger patients with NSCLC.

The subset analysis in the AURA3 trial revealed that there was no significant deviation in the HR for PFS with regards to age. However, the HRs were calculated by comparison between cytotoxic chemotherapy and osimertinib alone. The current study is the first to direct compare younger and older patients, warranting further investigation using larger cohorts. Of course, it remains unclear whether younger age is a prognostic or predictive factor of osimertinib treatment efficacy in the current study. However, we suggest that younger age was a predictive factor of osimertinib efficacy because of the shorter PFS with osimertinib treatment and lower response rate in the younger patients. These findings suggest that new studies should explore the molecular mechanism underlying the low efficacy of EGFR-TKIs in younger patients to overcome this hurdle.

There are several limitations in the current study. The single-center, retrospective study design and the small sample size might have introduced an element of selection bias. Specifically, additional clinical factors should be included in multivariate analysis. However, we believe that the effect of other clinical factors on our results is unlikely because none of the known clinical correlates of poor prognosis in patients with lung cancer were significantly different between the groups according to age and ECOG-PS. Furthermore, we did not evaluate the quality of life in patients who were administered osimertinib. However, we believe that the current study provides meaningful data for future studies to explore other characteristics including molecular characteristics of patients receiving low-efficacy EGFR-TKIs and overcoming tolerance to EGFR-TKIs, due to the scarcity of data pertaining to osimertinib treatment for patients with T790M-positive NSCLC in real-world settings.

Conclusions

Osimertinib treatment exhibited low efficacy in younger patients with T790M-positive NSCLC and those with poor ECOG-PS, who experienced poor outcomes. Although the number of patients with poor ECOG-PS was higher in the current study compared with the previous studies, the toxic effects of osimertinib were manageable.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Enago (www.enago.jp) for the English language review.

Ethical Statement: Our study followed the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki recommendations and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Tokyo Metropolitan Cancer and Infectious Diseases Centre in Komagome Hospital (No. 2134). Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: Y Hosomi, Y Okuma, K Kubota, M Seike and A Gemma have received honoraria from AstraZeneca. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Inoue A, Kobayashi K, Usui K, et al. First-line gefitinib for patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer harboring epidermal growth factor receptor mutations without indication for chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:1394-400. 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.7658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maemondo M, Inoue A, Kobayashi K, et al. Gefitinib or chemotherapy for non-small-cell lung cancer with mutated EGFR. N Engl J Med 2010;362:2380-8. 10.1056/NEJMoa0909530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosell R, Carcereny E, Gervais R, et al. Erlotinib versus standard chemotherapy as first-line treatment for European patients with advanced EGFR mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (EURTAC): a multicentre, open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2012;13:239-46. 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70393-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu YL, Zhou C, Hu CP, et al. Afatinib versus cisplatin plus gemcitabine for first-line treatment of Asian patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer harbouring EGFR mutations (LUX-Lung 6): an open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2014;15:213-22. 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70604-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wu YL, Cheng Y, Zhou X, et al. Dacomitinib versus gefitinib as first-line treatment for patients with EGFR-mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (ARCHER 1050): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2017;18:1454-66. 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30608-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kobayashi S, Ji H, Yuza Y, et al. An alternative inhibitor overcomes resistance caused by a mutation of the epidermal growth factor receptor. Cancer Res 2005;65:7096-101. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nguyen KS, Kobayashi S, Costa DB. Acquired resistance to epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors in non-small-cell lung cancers dependent on the epidermal growth factor receptor pathway. Clin Lung Cancer 2009;10:281-9. 10.3816/CLC.2009.n.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhong WZ, Zhou Q, Wu YL. The resistance mechanisms and treatment strategies for EGFR-mutant advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Oncotarget 2017;8:71358-70. 10.18632/oncotarget.20311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mok TS, Wu YL, Ahn MJ, et al. Osimertinib or platinum-pemetrexed in EGFR T790M-positive lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2017;376:629-40. 10.1056/NEJMoa1612674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu SG, Chang YL, Yu CJ, et al. Lung adenocarcinoma patients of young age have lower EGFR mutation rate and poorer efficacy of EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors. ERJ Open Res 2017. doi: . 10.1183/23120541.00092-2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yao ZH, Liao WY, Ho CC, et al. Real-world data on prognostic factors for overall survival in EGFR mutation-positive advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients treated with first-line gefitinib. Oncologist 2017;22:1075-83. 10.1634/theoncologist.2016-0331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer 2009;45:228-47. 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jain A, Lim C, Gan EM, et al. Impact of smoking and brain metastasis on outcomes of advanced egfr mutation lung adenocarcinoma patients treated with first line epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors. PLoS One 2015. May 8;10:e0123587. 10.1371/journal.pone.0123587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim MH, Kim HR, Cho BC, et al. Impact of cigarette smoking on response to epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)-tyrosine kinase inhibitors in lung adenocarcinoma with activating EGFR mutations. Lung Cancer 2014;84:196-202. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2014.01.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oxnard GR, Thress KS, Alden RS, et al. Association between plasma genotyping and outcomes of treatment with osimertinib (AZD9291) in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 2016;34:3375-82. 10.1200/JCO.2016.66.7162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Akamatsu H, Katakami N, Okamoto I, et al. Osimertinib in Japanese patients with EGFR T790M mutation-positive advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: AURA3 trial. Cancer Sci 2018;109:1930-8. 10.1111/cas.13623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goss G, Tsai CM, Shepherd FA, et al. Osimertinib for pretreated EGFR Thr790Met-positive advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (AURA2): a multicentre, open-label, single-arm, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol 2016;17:1643-52. 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30508-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nie K, Zhang Z, Zhang C, et al. Osimertinib compared docetaxel-bevacizumab as third-line treatment in EGFR T790M mutated non-small-cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer 2018;121:5-11. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2018.04.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Soria JC, Ohe Y, Vansteenkiste J, et al. Osimertinib in untreated EGFR-mutated advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2018;378:113-25. 10.1056/NEJMoa1713137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ando M, Okamoto I, Yamamoto N, et al. Predictive factors for interstitial lung disease, antitumor response, and survival in non-small-cell lung cancer patients treated with gefitinib. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:2549-56. 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.9866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goto K, Nishio M, Yamamoto N, et al. A prospective, phase II, open-label study (JO22903) of first-line erlotinib in Japanese patients with epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutation-positive advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Lung Cancer 2013;82:109-14. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2013.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Okamoto I, Morita S, Tashiro N, et al. Real world treatment and outcomes in EGFR mutation-positive non-small cell lung cancer: Long-term follow-up of a large patient cohort. Lung Cancer 2018;117:14-9. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2018.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roviello G, Zanotti L, Cappelletti MR, et al. Are EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors effective in elderly patients with EGFR-mutated non-small cell lung cancer? Clin Exp Med 2018;18:15-20. 10.1007/s10238-017-0460-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ariyasu R, Nishikawa S, Uchibori K, et al. High ratio of T790M to EGFR activating mutations correlate with the osimertinib response in non-small-cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer 2018;117:1-6. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2017.12.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jänne PA, Yang JC, Kim DW, et al. AZD9291 in EGFR inhibitor-resistant non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2015;372:1689-99. 10.1056/NEJMoa1411817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Giordano M, Boldrini L, Servadio A, et al. Differential microRNA expression profiles between young and old lung adenocarcinoma patients. Am J Transl Res 2018;10:892-900. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Canale M, Petracci E, Delmonte A, et al. Impact of TP53 mutations on outcome in EGFR-mutated patients treated with first-line tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Clin Cancer Res 2017;23:2195-202. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-0966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]