Abstract

DNA-RNA hybrid (DRH) duplexes play essential roles during the replication of DNA and the reverse transcription of RNA viruses, and their flexibility is important for their biological functions. Recent experiments indicated that A-form RNA and B-form DNA have a strikingly different flexibility in stretching and twist-stretch coupling, and the structural flexibility of DRH duplex is of great interest, especially in stretching and twist-stretch coupling. In this work, we performed microsecond all-atom molecular dynamics simulations with new AMBER force fields to characterize the structural flexibility of DRH duplex in stretching and twist-stretch coupling. We have calculated all the helical parameters, stretch modulus, and twist-stretch coupling parameters for the DRH duplex. First, our analyses on structure suggest that the DRH duplex exhibits an intermediate conformation between A- and B-forms and closer to A-form, which can be attributed to the stronger rigidity of the RNA strand than the DNA strand. Second, our calculations show that the DRH duplex has the stretch modulus of 834 ± 34 pN and a very weak twist-stretch coupling. Our quantitative analyses indicate that, compared with DNA and RNA duplexes, the different flexibility of the DRH duplex in stretching and twist-stretch coupling is mainly attributed to its apparently different basepair inclination in the helical structure.

Significance

DNA-RNA hybrid (DRH) duplexes are important intermediates in molecular biology and can play critical roles in the cell life. The flexibility of DRH duplexes can be important for their biological functions and may be very different from those of DNA and RNA duplexes. Here, we performed microsecond molecular dynamics simulations to quantitatively characterize the flexibility of the DRH duplex in stretching and twist-stretch coupling. We found that a DRH duplex exhibits an intermediate conformation between A- and B-forms, closer to A-form. Furthermore, a DRH duplex has a stretch modulus of 834 ± 34 pN and a weak twist-stretch coupling. Such different flexibility of DRH duplex from DNA and RNA duplexes in stretching and twist-stretch coupling is mainly attributed to its different basepair inclination.

Introduction

DNA-RNA hybrids (DRH) are important intermediates in molecular biology (1, 2, 3, 4, 5). There are generally two major types of heterogeneous hybrids in vivo, including hybrid duplex and hybrid chimeras (1, 2, 3, 4), and they can play important roles in the cell life (1, 2, 3, 4). During DNA replication, Okazaki fragments are formed on the lagging template strand, which are hybrid chimeras, with one DNA strand and the other RNA-DNA chimera strand (2, 4). Moreover, during reverse transcription, RNA viruses create DRH duplexes with one pure DNA strand and the other pure RNA strand (1, 3). In addition, DRH duplex can be recognized with RNase H enzyme, which is endonuclease and can specifically hydrolyze the RNA strand in hybrids (6, 7), and DRH duplexes may also play an important role in the transition from the RNA world to the DNA world in evolution (8). Existing experiments suggested that the structure and flexibility of DRH duplex can be crucial for their biological functions and clinical applications, such as the design of high stability and specificity to the RNase H-susceptible DRH and antisense therapy based on the activation of the RNase H mechanism (6, 7, 9).

The structures of DRH duplexes have been individually studied by some experimental techniques, such as x-ray and NMR methods (10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15). These experiments indicated that the structures of most DRH duplexes are in a unique conformation with neither A-form nor B-form (10, 11, 12) and are biased toward A-form conformation. Furthermore, the NMR data showed the differences in the distribution of backbone angles between DNA and RNA strands in DRH duplexes (10, 11). Meanwhile, existing nanosecond-timescale all-atom molecular dynamics (MD) simulations showed that hybrid duplexes adopt an A-like conformation or intermediate conformation between A-form and B-form globally (16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21), and each strand in a DRH duplex maintains its essential dynamics in pure DNA or RNA duplexes (i.e., DNA strand is more flexible and RNA strand is more rigid in A-like DRH duplex) (16, 17, 18). This suggests that the flexibility of the DRH duplex is unique and not a simple average of those of pure DNA and RNA strands. Until now, there is still a lack of a quantitative and extensive characterization on the structural flexibility and helical parameters of the DRH duplex.

In contrast, the flexibility of A-form RNA and B-form DNA duplexes have been quantitatively measured via advanced single-molecule techniques (22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37). These experiments indicate that DNA and RNA duplexes are only slightly different in bending and torsional stiffness (e.g., bending persistence length ∼45–50 nm for DNA duplex and ∼60 ± 10 nm for RNA duplex (26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35), and torsional persistence length ∼70–110 nm for DNA duplex and ∼100 nm for RNA duplex (29, 30, 31), respectively). However, recent experiments also show that DNA and RNA duplexes are strikingly different in stretching and twist-stretch coupling: 1) RNA duplex is significantly softer than DNA in stretching (i.e., stretch modulus S ∼350–600 pN and ∼1000–1500 pN for RNA and DNA duplexes (30, 31, 34), respectively); and 2) DNA duplex has an apparently negative twist-stretch coupling, whereas such twist-stretch coupling is apparently positive for RNA duplex (31). Later, all-atom MD simulations have been performed to understand the striking differences in stretching and twist-stretch coupling between DNA and RNA duplexes, and such differences are attributed to their different helical B-form and A-form structures (38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46). However, the structural flexibility of the DRH duplex has not been quantitatively characterized via either single-molecule techniques or all-atom MD simulations, especially on stretching and twist-stretch coupling, which can be sensitive to helical structures of nucleic acids (16, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51).

In this work, we have employed microsecond all-atom MD simulations with new AMBER force fields to quantitatively characterize the flexibility of DRH duplex, including stretching and twist-stretch coupling. First, we analyzed the structure features and provided almost all the helical structure parameters for DRH duplex based on our microsecond MD trajectories. Afterwards, we calculated the stretch modulus and twist-stretch coupling parameter and performed the corresponding analyses on stretching and twist-stretch coupling for the DRH duplex. Our calculations and analyses for the DRH duplex were compared to DNA and RNA duplexes.

Methods

All-atom MD simulations

In this work, the 16-bp DNA duplex with a sequence of CGCGCATCCTTCGGCG and its complementary one in B-form and the 16-bp RNA duplex with the sequence of CGCGCAUCCUUCGGCG and its complementary one in A-form were built with the University of California San Francisco Chimera program (52). The two 16-bp DRH duplexes with the same sequence of CGCGCATCCTTCGGCG and its complementary one of CGCCGAAGGAUGCGCG were built in A-form and B-form, respectively. The random DNA sequences were chosen from the sequences constructed based on the short DNAs in the experiments that measured the fluctuations of the end-to-end distance of short DNAs through labeling gold nanocrystals at two ends (28, 48, 50). The RNA sequences were taken the same as the DNA sequences except that T was replaced by U. Excluding the three basepairs at each end, the sequences of RNA, DNA, and DRH duplexes are with a CG content of 60%. The canonical A-form and B-form DRH duplexes, A-form RNA duplex, and B-form DNA duplex are shown in Fig. 1 A and were used as initial structures for all-atom MD simulations.

Figure 1.

(A) The initial structures of 16-bp DNA-RNA hybrids, RNA, and DNA duplexes in our simulations: canonical A-form hybrid, B-form hybrid, RNA, and DNA duplexes (from left to right). (B and C) Shown are the root mean-square deviations (RMSD) versus MD running time (1 μs) for two independent MD trajectories with different initial structures: A-form DNA-RNA hybrid (B) and B-form DNA-RNA hybrid (C). Here, the RMSDs for DNA-RNA hybrids calculated with canonical A-form (red lines) and B-form (blue lines) hybrids as reference structures are denoted with red and blue lines, respectively. (D) Shown are the RMSDs versus MD running time for two independent MD trajectories with different initial structures: A-form DNA-RNA hybrid (red line) and B-form DNA-RNA hybrid (blue line). Here, the RMSDs for DNA-RNA hybrids are calculated with canonical A-form hybrid as reference structure. In (B–D), the central light lines represent the respective RMSDs averaged over every 2 ns. The structures for the nucleic acids are displayed with visual molecular dynamics (VMD) (90). To see this figure in color, go online.

The initial structures, including A-form RNA, B-form DNA, A-form DRH, and B-form DRH duplexes, were immersed in rectangular boxes containing explicit water and ions. The counterions of Na+ and the salt of 1M NaCl (50) were added with the ion model from Joung and Cheatham (53) to ensure that our simulated systems are fully neutralized (54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61). All MD simulations were performed in the isothermic-isobaric ensemble (P = 1 atm, T = 298 K) when the systems were energy minimized, thermalized, and equilibrated. Afterwards, 1 μs MD simulations were performed for the pre-equilibrated systems at a constant temperature (298 K) and pressure (1 atm), with the periodic boundary conditions and the particle mesh Ewald method for long-range interactions (62). An integration step of 2 fs was used in conjunction with the leap-frog algorithm (63). During this process, DRH, RNA, and DNA duplexes were completely free in the solutions. All of our simulations were carried out using the Gromacs 4.6 software package with newly refined AMBER ff99bsc0+χOL3 and ff99bsc0 + bsc1 force fields (53, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69) and TIP3P water model for molecular interactions (69, 70). The details for the MD simulation systems are provided in Table S1. Because of lack of a set of force field newly defined for both DNA and RNA, in this work, we can only use the above described different sets of forces fields for DNA, RNA, and DRH duplexes, respectively.

To estimate the response of stretching and twist-stretch coupling of the DRH duplex to an external stretching force, we performed additional (200 ns) all-atom MD simulations for the DRH duplex at different stretching forces based on the final equilibrium configuration of the above described simulation at zero force. In the simulations, the mass center of an end basepair was fixed with a strong harmonic constraint, and the mass center of another end basepair was applied with a constant force in the direction of helical axis (71, 72) (see Fig. S2 A) The details for the MD simulation systems under stretching forces are provided in Table S2.

Data analyses and helical parameters

To avoid the end effect of short duplexes, the three basepairs at each end were removed for all the analyses of the MD trajectories (50, 55, 60). As shown in Figs. 1, B–D and S1, all the MD simulations at zero force are nearly converged after ∼300 ns, and Fig. S2, B and C shows that the MD simulations at different stretching forces reach the equilibrium very quickly (after ∼30 ns). The rigid body parameters and the torsion angles, including backbone torsion and sugar puckering angles, are used to describe the geometry of nucleic acid helices and are illustrated in Fig. S3 (73, 74, 75, 76, 77, 78, 79, 80, 81). In this work, helical and geometrical parameters were all obtained using the program Curves+ (82).

Among the helical parameters, helical rise (H-rise) and helical twist (H-twist) are crucial because they can be directly measured in single-molecule experiments and correspond to the macroscopic contour length L and helical periodicity Φ of nucleic acid helices (50, 83). As one of the helical parameters, helical radius is referenced to the radius of phosphate groups calculated by the following formula (21, 51, 72):

| (1) |

where dpp is the distance between two adjacent phosphates, and the bracket〈…〉denotes an average over MD simulation time.

To better analyze the stretching flexibility of the DRH duplex, we would use the following formula of the relationship between H-rise and rise in our analyses (50, 84):

| (2) |

where θ is basepair inclination. Similarly, we also used the following formula of the relationship between H-twist and twist to understand the twist-stretch coupling for DRH duplex (50):

| (3) |

Calculations of elastic parameters

The macroscopic elastic parameters, such as stretch modulus S and twist-stretch coupling for a nucleic acid duplex, can be evaluated as the diagonal term of the elastic matrix K and are determined by the following (50, 51, 85):

| (4) |

where V is the 2-by-2 covariance matrix of the two global helical coordinates (L and Φ over the central 10 basepairs). L0, T, and kB are the average value of contour length, thermodynamics temperature in Kelvin, and Boltzmann constant (47, 50, 51, 83). In Eq. 2, the diagonal term of V−1 can be understood as the reciprocal of the partial variances, as described in (85). The stretch modulus and twist-stretch coupling are associated to contour length L and cumulative H-twist Φ in Eq. 4 (50), respectively.

Calculations of Pearson correlation coefficient

To examine the strength of possible correlations between microscopic parameters for DRH, DNA, and RNA duplexes, we also calculated Pearson correlation coefficients for extensive pairs of microscopic structure parameters according to the following (86):

| (5) |

where cov(a,b) = 〈(a−〈a〉)(b−〈b〉)〉 is the covariance between microscopic structure parameters a and b. The σa and σb are the SDs of the microscopic structure parameters a and b, respectively. Here, corr(a,b) = 1, −1, 0, which corresponds to a fully positive coupling, a fully negative coupling, and no coupling, respectively.

Results and Discussion

Structure and helical parameters of the DRH duplex

Based on the microsecond MD trajectories with new AMBER force fields, we examined the global structure of DRH duplex through calculating the root mean-square deviations (RMSDs). As shown in Fig. 1, B–D, the MD simulation with initial A-form DRH duplex quickly reaches its equilibrium, whereas that with initial B-form DRH duplex achieves its equilibrium only after ∼300 ns. This may suggest that the global structure of DRH duplex may be closer to A-form rather than B-form. Our further calculation indicated that mean RMSD of DRH duplex is ∼2.3 ± 0.4 Å with canonical A-form as reference structure and is ∼3.2 ± 0.1 Å with canonical B-form as reference structure. Thus, a DRH duplex exhibits an A-like helical structure rather than a B-like one. Given the RMSD between the initial canonical A-form and B-form DRH duplexes of ∼4.4 Å, we can conclude that the DRH duplex adopts an intermediate conformation between canonical A-form and B-form and is biased to A-form. Besides, as shown in Fig. 2 A, the structure of the DRH duplex is more similar to that of RNA duplex rather than DNA duplex.

Figure 2.

(A) The snapshots for DRH duplexes from initial A-form (left) and B-form (right) and for RNA and DNA duplexes in equilibrium. Shown are the probability distributions of basepair step and helical parameters, including H-rise (B), H-twist (C), helical radius (D), inclination (E), major or minor groove widths (F and G), and depths (H and I) for DNA-RNA hybrid (red line), RNA (blue line), and DNA (green line) duplexes. To see this figure in color, go online.

Beyond the analyses on the global structure through RMSDs, we would quantitatively characterize the extensive helical parameters of the DRH duplex based on the microsecond MD trajectories in a comparative way with DNA and RNA duplexes. These helical parameters include H-rise and rise, H-twist and twist, helical radius, inclination, depths of major and minor grooves, widths of major and minor grooves, etc. As shown in Fig. 2 and Table 1, all the shown helical parameters of the DRH duplex are between those of DNA and RNA duplexes. For example, the major helical parameters of H-rise (∼3.1 Å), H-twist (∼31.7°), and inclination (∼10.1°) of the DRH duplex fall in the respective ranges between RNA and DNA duplexes (i.e., 2.8, 3.3 Å for H-rise; 31.0, 33.1° for H-twist; and 4.1, 14.9° for inclination). This indicates that the DRH duplex exhibits a helical structure between the DNA and RNA duplexes. More strictly, Table 1 shows that most of the helical parameters of the DRH duplex are apparently or slightly closer to those of the RNA duplex rather than to those of the DNA duplex. For example, given a total of 12 helical parameters, 9 helical parameters of the DRH duplex are (slightly) closer to those of the RNA duplex, including twist, H-twist, rise, slide, roll, inclination, depths of major groove/minor groove, and width of minor groove (see Table 1). Therefore, the above analyses on helical parameters suggest that the DRH duplex exhibits an intermediate conformation between the DNA and RNA duplexes and is more inclined toward an A-form.

Table 1.

Macroscopic Elastic Parameters and Microscopic Structural Parameters for DRH, RNA, and DNA Duplexesa

| DRH | RNA | DNA | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stretch modulus (pN) | 834 ± 34 | 605 ± 32 | 1453 ± 46 |

| Twist-stretch coupling (nm/turn) | −0.06 ± 0.02 | −0.85 ± 0.02 | 0.59 ± 0.02 |

| H-rise (Å) | 3.10 ± 0.13 | 2.80 ± 0.15 | 3.30 ± 0.10 |

| H-twist (deg.) | 31.74 ± 0.93 | 31.02 ± 0.88 | 33.06 ± 1.13 |

| Rise (Å) | 3.33 ± 0.07 | 3.33 ± 0.07 | 3.34 ± 0.06 |

| Twist (deg.) | 31.0 ± 0.93 | 29.60 ± 0.86 | 32.85 ± 1.17 |

| Slide (Å) | −1.32 ± 0.16 | −1.63 ± 0.16 | −0.64 ± 0.23 |

| Roll (deg.) | 5.47 ± 1.75 | 7.97 ± 1.71 | 2.27 ± 1.76 |

| Inclination (deg.) | 10.13 ± 2.83 | 14.92 ± 2.79 | 4.05 ± 2.75 |

| Major groove width (Å) | 10.35 ± 1.90 | 7.22 ± 1.58 | 12.59 ± 0.91 |

| Minor groove width (Å) | 8.55 ± 0.15 | 9.80 ± 0.05 | 6.72 ± 0.34 |

| Major groove depth (Å) | 8.73 ± 0.56 | 10.40 ± 0.44 | 6.35 ± 0.74 |

| Minor groove depth (Å) | 2.63 ± 0.09 | 1.08 ± 0.04 | 4.22 ± 0.11 |

| Helical radius (Å)b | 10.30 ± 0.71 | 10.14 ± 0.58 | 10.40 ± 0.67 |

The SDs are shown alongside the average values, and the SDs are calculated for the average values of structural parameters per conformation.

Here, helical radius represents the helical radius of phosphate groups.

It is also interesting to compare the simulated structure of the DRH duplex with those deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB). The helical parameters of two DRH duplexes (PDB: 1efs and 1hg9) have been listed in Table S3, in a comparison with those of the DRH duplex from our MD simulations. The microscopic parameters from our simulations are very close to those of the experimental DRH structures, especially to those of 1efs, suggesting the reliability of our simulations and the force fields.

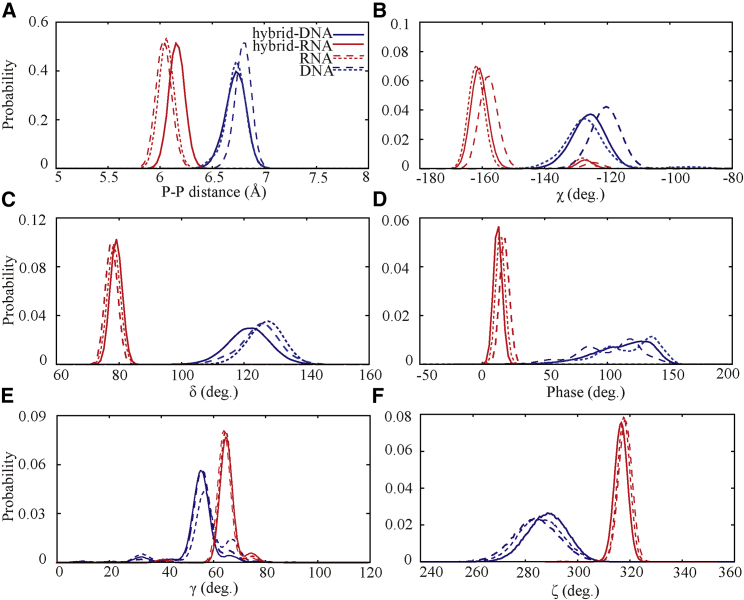

Because a DRH duplex is composed of a DNA strand and an RNA strand, we would analyze the structures of two strands instead of the whole duplex. According to previous studies on analyzing the structure of single strands (11, 16, 18), the glycosidic torsion angle between sugar and base (χ), pseudoration angle (phase), the angle (δ) related to sugar-ring puckering, and the intrastrand phosphorus-phosphorus (P-P) distance were used to characterize the structure of single DNA and RNA strands in DRH duplex (see Fig. S3 B). As shown in Fig. 3, the distributions of these quantities are visibly different for single DNA strands in the DNA duplex and single RNA strands in the RNA duplex, and the distributions of the quantities of DNA and RNA strands in the DRH duplex are close to those of DNA strands in the pure DNA duplex and those of RNA strands in the pure RNA duplex, respectively. This suggests that DNA and RNA strands have a strong tendency for keeping their intrinsic structures even in the DRH duplex. Furthermore, Fig. 3 and Table 2 show that the distributions for the DNA strand generally appear broader than those of the RNA strand, suggesting the DNA strand is more flexible than the RNA strand. Then, we can understand why a DRH duplex adopts an A-like helix as follows. During DRH duplex formation, DNA and RNA strands are mutually competitive and can become deformed slightly to fit to each other. Because the RNA strand is more rigid than the DNA strand, the deformation of the RNA strand would be slighter than that of the DNA strand, and thus, a DRH duplex would exhibit an A-like conformation rather than a B-like one. In addition to the above shown structural quantities, such as backbone dihedral angles γ and ζ, which can distinguish DNA and RNA strands, the distributions of other torsional angles are shown in Fig. S4, and they are not apparently distinguishable for DNA and RNA strands in DRH duplex.

Figure 3.

The probability distributions of intrastrand phosphorus-phosphorus distance (A), backbone and glycosyl torsion angles χ (B), δ (C), pseudorotational angle phase (D), γ (E), and ζ (F) for the RNA strand (solid red lines) and the DNA strand (solid blue lines) in the DNA-RNA hybrid duplex. For comparisons, the figure also shows the probability distributions of the corresponding RNA strand with the same sequence (dotted red lines) and its complementary one (dashed red lines) in the RNA duplex and those of the corresponding DNA strand with the same sequence (dotted blue lines) and its complementary one (dashed blue lines) in the DNA duplex. The backbone glycosyl torsion angles χ, δ, γ, ζ, and pseudorotational angle phase are generally used to characterize the strand structure and are illustrated in Fig. S2B. To see this figure in color, go online.

Table 2.

Backbone Dihedral Angles for the RNA and DNA Strands in DRH Duplex and in RNA and DNA Duplexes

| Torsion Angles | Average Value |

Average Value |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| hy-RNAa | RNAb | ΔRNAc | hy-DNAa | DNAb | ΔDNAc | |

| χ (deg.) | −157.92 ± 9.91 | −158.28 ± 10.81 | 0.36 | −125.66 ± 5.88 | −120.10 ± 5.29 | 5.56 |

| δ (deg.) | 79.34 ± 1.90 | 77.84 ± 1.93 | 1.50 | 121.81 ± 6.75 | 127.13 ± 5.62 | 5.32 |

| Phase (deg.) | 12.64 ± 3.44 | 14.85 ± 3.62 | 2.21 | 112.04 ± 22.68 | 116.18 ± 24.10 | 4.14 |

| γ (deg.) | 71.89 ± 5.20 | 70.71 ± 4.92 | 1.18 | 58.99 ± 14.72 | 60.62 ± 7.25 | 1.63 |

| ζ (deg.) | 321.59 ± 2.65 | 320.37 ± 2.64 | 1.22 | 288.55 ± 7.48 | 285.16 ± 8.33 | 3.39 |

The hy-RNA and hy-DNA are the RNA and DNA strands of the DRH duplex, respectively.

The RNA and DNA denote that the strands in the RNA and DNA duplexes with the same sequences correspond to the hy-RNA or hy-DNA, respectively.

ΔRNA and ΔDNA denote the absolutely average value deviations between hy-RNA and RNA and between hy-DNA and DNA, respectively.

Stretching flexibility and stretch modulus for DNA-RNA duplex

In the following, we would examine the stretching flexibility based on the microsecond MD trajectories with new AMBER force fields. Generally, the distribution of contour length L (H-rise × basepair steps) can directly reflect the macroscopic stretching properties of a duplex (50, 83). For the central 10 basepairs, as shown in Fig. S5 A, the L distribution of the DRH duplex is between those of RNA and DNA duplexes. The average contour lengths L0 are ∼28.1 Å for DRH duplex, ∼25.5 Å for RNA duplex, and ∼30.0 Å for DNA duplex, and the corresponding variances of contour length L for DRH duplex, RNA, and DNA duplexes are ∼1.4, ∼1.7, and ∼0.8 Å, respectively. According to Eq. 4, the stretch modulus S can be calculated based on the distributions of contour length. The calculated stretch modules S is ∼834 ± 34 pN for DRH duplex, which is between that of ∼605 ± 32 pN for RNA duplex and that of ∼1453 ± 46 pN for DNA duplex (see Table 1). Our calculations of stretch modulus for DNA and RNA duplexes are in quantitative agreement with previous experimental measurements (∼350–600 pN for RNA duplex and ∼1000–1500 pN for DNA duplex at 0.1–1 M Na+ concentration) (22, 23, 30, 31). Furthermore, our calculated stretch modulus for the DRH duplex is visibly closer to that of the RNA duplex than to that of the DNA duplex, which is in good accordance with the very recent single-molecule experiments on the bending and stretching flexibility of a DRH duplex (87). Therefore, our calculations show that the stretching flexibility of a DRH duplex is apparently stronger than that of a DNA duplex and slightly weaker than that of an RNA duplex.

To understand the different stretching flexibility of a DRH duplex from those of DNA and RNA duplexes, we analyzed the related microscopic parameters. The microscopic analyses on H-rise and rise show that the distributions of rise are almost identical for DRH, RNA, and DNA duplexes, and the average values of rise are ∼3.33 Å, whereas the distributions of H-rise are very different (see Fig. 4 A and Table 1). For analyzing the relationship between H-rise and the rise of DRH duplexes, Eq. 2 has been used (50, 84) and was also illustrated in Fig. 4 B, in which the contributions of shift and tip were ignored because their small values (50) (see Fig. S6). As shown in Fig. S7, A–C, Eq. 2 can well describe the relationship between H-rise, rise, inclination, and slide for DRH, DNA, and RNA duplexes. Furthermore, we examined the relationships between H-rise and the three variables, including rise, inclination, and slide, based on the MD trajectories. As shown in Fig. 4, C–E, there are apparent correlations between H-rise and rise and between H-rise and inclination (i.e., the increase of rise and the decrease of inclination are strongly coupled to the increase of H-rise, whereas slide seems very weakly related with H-rise). To further examine these relationships, we calculated the Pearson correlation coefficients between H-rise and the variables, including rise, inclination, and slide. Table 3 shows that H-rise strongly and negatively correlates with inclination and positively and apparently correlates with rise (i.e., corr(H-rise, inclination)’s are ∼−0.78, ∼−0.78, and ∼−0.67 for DRH, RNA, and DNA duplexes, and corr(H-rise, rise)’s are ∼0.60, ∼0.43, and ∼0.70 for DRH, RNA, and DNA duplexes, respectively). Moreover, corr(H-rise, slide)’s are ∼−0.07, ∼−0.005, and ∼−0.06 for DRH, RNA, and DNA duplexes, suggesting weak correlation between H-rise and slide. Thus, because of the very weak coupling between H-rise and slide, Eq. 2 can be approximately written as the following:

| (6) |

where 〈slide〉 represents the average value of slide. As shown in Fig. S8 A, Eq. 6 works well in analogy to Eq. 2. Furthermore, Fig. 4 F and Table 3 also show that the correlation between rise and inclination is rather weak, and consequently, rise and inclination θ in the right hand of Eq. 6 can be approximately considered as two independent variables.

Figure 4.

(A) The probability distributions of H-rise (dashed line) and rise (solid line) for DNA-RNA hybrid (red), RNA (blue), and DNA (green) duplexes, respectively. (B) The illustrations of rise, H-rise, and inclination θ between adjacent basepairs and central helical axis are shown. (C and F) Shown are the relationships between H-rise and rise (C), between H-rise and inclination (D), between H-rise and slide (E), and between rise and inclination (F) for DNA-RNA hybrid (red), RNA (blue), and DNA (green) from the statistical analyses of MD trajectories. Here, error bars are obtained as standard errors of averages in each interval, and most of the error bars are smaller than the symbols. To see this figure in color, go online.

Table 3.

Pearson Correlation Coefficients between Two Microscopic Structural Parameters for DRH, RNA, and DNA Duplexes

| DRH | RNA | DNA | |

|---|---|---|---|

| corr(H-rise, inclination)a | −0.78 | −0.78 | −0.67 |

| corr(H-rise, rise)a | 0.60 | 0.43 | 0.70 |

| corr(H-rise, slide)a | −0.07 | −0.005 | −0.06 |

| corr(rise, inclination)a | −0.17 | −0.006 | −0.20 |

| corr(H-rise, H-twist)b | −0.02 | −0.16 | 0.18 |

| corr(H-rise, twist)b | 0.21 | 0.25 | 0.24 |

| corr(H-twist, inclination)b | 0.09 | 0.25 | −0.19 |

| corr(twist, inclination)b | −0.21 | −0.23 | −0.27 |

| corr(roll, inclination)b | 0.90 | 0.92 | 0.84 |

| corr(roll, H-rise)b | −0.76 | −0.75 | −0.70 |

| corr(twist, roll)b | −0.13 | −0.13 | −0.28 |

| corr(twist, rise)b | −0.12 | −0.24 | 0.039 |

The Pearson correlation coefficients are related to stretch modulus for DRH, RNA, and DNA duplexes.

The Pearson correlation coefficients are related to twist-stretch coupling for DRH, RNA, and DNA duplexes.

Because the stretching flexibility is directly coupled to the fluctuation of H-rise, Eq. 6 can be differentiated into the following formula for the fluctuation of H-rise:

| (7) |

where the approximations of sinθ∼θ and cosθ∼1 are used because of the relatively small inclination θ. When a duplex fluctuates to a stretched conformation (i.e., dH-rise > 0), drise > 0 and the second (−rise × θ × dθ) and third terms (〈slide〉 × dθ) in Eq. 6 are both positive because dθ < 0 and 〈slide〉 < 0 (see Table 1 and Fig. 4, D and E). As shown in Eq. 7 and Table 1, drise is the same for DRH, RNA, and DNA duplexes, and thus, the big difference of dH-rise comes from the second and third terms. Because the absolute values of rise and dθ are all similar for DRH, RNA, and DNA duplexes, the difference in dH-rise should be attributed to the different θ in the second term and 〈slide〉 in the third term, and thus, the larger inclination and absolute value of 〈slide〉 contribute to larger dH-rise and stronger stretching flexibility. More quantitatively, we substituted the values of corresponding quantities in Table 1 into the right hand of Eq. 7, and we can obtain that dH-rise is ∼0.16, ∼0.19, and ∼0.1 Å for DRH, RNA, and DNA duplexes, which are very close to those (∼0.13, ∼0.15, and ∼0.1 Å) directly obtained from the MD trajectories (see Table 1). This suggests that our above analyses on the relative stretching flexibility of DRH, RNA, and DNA duplexes are reasonable and quantitative.

Therefore, the apparently different stretching flexibility of the DRH duplex from DNA and RNA duplexes is attributed to the different basepair inclination and slide. Furthermore, basepair inclination is more essential because slide is almost uncorrelated to H-rise, and the contribution of slide is reflected through the fluctuation of inclination, as indicated in Eq. 7. The inclination and slide of the DRH duplex are between those of RNA and DNA duplexes and are apparently closer to those of RNA duplex, and consequently, the stretch modulus of ∼834 pN of DRH duplex is between those of ∼605 pN RNA duplex and ∼1453 pN of DNA duplex and is visibly closer to that of RNA duplex.

In addition, we estimated the response of the stretching of the DRH duplex to an external stretching force through additional all-atom MD simulations under different stretching forces based on the final equilibrium configuration at zero force. As shown in Fig. S9, the helix length of the DRH duplex increases linearly with the increase of stretching force in the force regime of <40 pN. The slope of force versus helix length can give a stretch modulus S of ∼775 ± 31 pN in the force regime (72), a value very close to that (∼834 ± 34 pN) calculated at zero force. This suggests that a DRH duplex would become stretched linearly in response to an external stretching force in the force regime of <40 pN, in analogy with DNA and RNA duplexes revealed by previous MD simulations (72).

Twist-stretch coupling for DRH duplex

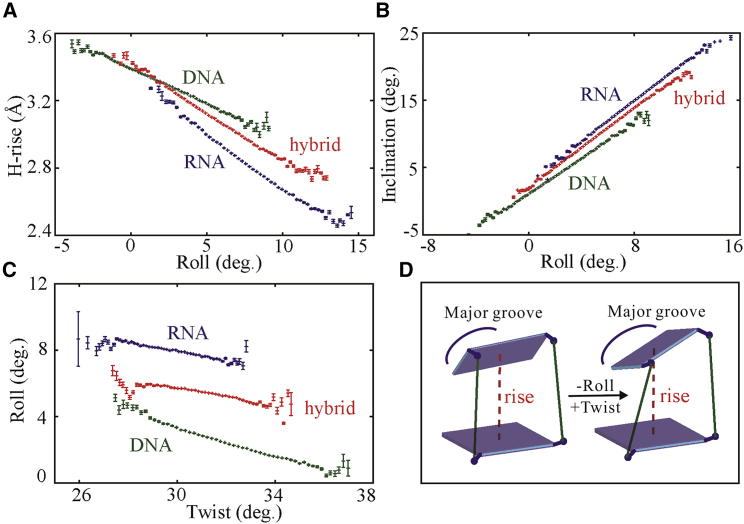

In the following, we would examine the twist-stretch coupling for DRH duplex based on our microsecond MD trajectories with the new AMBER force fields. As shown in Fig. 5 A, the twist-stretch coupling is rather weak for DRH duplex, and the coupling parameter dH-rise/dH-twist is ∼−0.06 nm/turn. In contrast, the twist-stretch coupling is visibly negative and positive for DNA and RNA duplexes, respectively, and the corresponding twist-stretch coupling parameters are ∼−0.85 nm/turn for RNA duplex and ∼0.59 nm/turn for DNA duplex, which are in good agreement with the experimental values of ∼−0.85 ± 0.04 and ∼0.5 ± 0.1 nm/turn for RNA and DNA duplexes (29, 31, 50), respectively. The twist-stretch coupling parameter of ∼−0.06 nm/turn for the DRH duplex suggests that a DRH duplex only unwinds very weakly when stretched, which is apparently different from DNA and RNA duplexes. The Pearson correlation coefficients corr(H-rise, H-twist)’s of ∼−0.02, ∼−0.16, and ∼0.18 suggest very weakly positive, visibly positive, and visibly negative twist-stretch coupling for DRH, RNA, and DNA duplexes (see Table 3).

Figure 5.

(A and B) The relationships between H-rise and H-twist (A) and between H-rise and twist (B). (C) The probability distributions of H-twist (solid line) and twist (dashed line) are directly extracted from the MD trajectories for the central 10 basepairs of DNA-RNA hybrid (red lines), RNA (blue lines), and DNA (green lines) duplexes. (D) Shown is the illustration for the relationship between the three quantities: twist, H-twist, and inclination. (E and F) The relationships between H-twist and inclination (E) and between twist and inclination (F) are shown. Here, error bars are obtained as standard errors of averages in each interval. To see this figure in color, go online.

What causes the striking difference in twist-stretch coupling between DRH, RNA, and DNA duplexes? To understand the coupling between H-rise and H-twist, we first examined the relationship between H-rise and twist. As shown in Fig. 5 B, it is interesting that H-rise is coupled with twist in a similar way (with visibly positive slope) for DRH, RNA, and DNA duplexes. Therefore, the striking different twist-stretch coupling for DRH, DNA, and RNA duplexes should be attributed to the degree of difference between H-twist and twist because H-rise is apparently and positively correlated with twist for all of DRH, DNA, and RNA duplexes (see Fig. 5, A and B). To understand such difference shown in Figs. 5, A–C and S5 B, we would examine the relationship between H-twist and twist, which is illustrated in Fig. 5 D and can be quantified by Eq. 3 (50). As shown in Fig. S7, D–F, Eq. 3 can well describe the relationship between twist and H-twist for DRH, DNA, and RNA duplexes.

To analyze the twist-stretch coupling for DRH, DNA, and RNA duplexes, Eq. 3 can be directly differentiated into the following:

| (8) |

where the approximation of sinθ∼θ and cosθ∼1 are also used because θ is relatively small. Here, we used dH-twist/dθ instead of dH-twist/dH-rise because only inclination θ is involved in the relationship between H-twist and twist, and θ is strongly and negatively coupled to H-rise (see Figs. 4 D and 5, E and F). Eq. 8 shows that the slope of dH-twist/dθ comes from the competition between the negative first term (dtwist/dθ) and the positive second term (twist×θ) (see Fig. 5, E and F). As shown in Fig. 5, E and F and Table 1, the first terms are not very different (i.e., dtwist/dθ ∼−0.081, ∼−0.073, and ∼−0.126 for DRH, RNA, and DNA duplexes, whereas the second terms are ∼0.096, ∼0.135, and ∼0.04 for DRH, RNA, and DNA duplexes, which are significantly different because of the significantly different inclinations θ. As the result, the absolute values of first term are slightly smaller than, apparently less than, and apparently larger than those of second term for DRH, RNA, and DNA duplexes, respectively, causing dH-twist/dθ to be weakly positive, visibly positive, and visibly negative for DRH, RNA, and DNA duplexes. This suggests that the different signs of dH-twist/dθ for DRH, RNA, and DNA duplexes mainly come from their significantly different basepair inclinations. Therefore, given the strong and negative coupling between inclination θ and H-rise, the different twist-stretch coupling of DRH duplex is attributed to its different basepair inclination, as compared with DNA and RNA duplexes.

Next, we would go to understand the positive slope between H-rise and twist for DRH, DNA, and RNA duplexes at microscopic levels as follows. First, we need to find a local structure parameter in strong coupling with H-rise because twist is a local structure parameter, whereas H-rise is a helical parameter. As shown in Figs. 4 D and 6, A and B and in Table 3, H-rise is strongly and negatively coupled to the local parameter roll, and inclination is strongly positively coupled to the roll for DRH, RNA, and DNA duplexes. Here, we would understand the slope between roll and twist instead of that between H-rise and twist. Fig. 6 C shows that roll and twist are negatively correlated, in consistency with the positive correlation between H-rise and twist. Then, how is roll negatively correlated with twist? As illustrated in Fig. 6 D, when the roll decreases in response to the increase of H-rise, twist can only increase because phosphate-sugar backbones are approximately inextensible or incompressible. Therefore, twist increases when a duplex fluctuates to a stretched conformation. It is also noted that the contribution of rise to the correlation between H-rise and twist is ignored because of either the very weak coupling between rise and twist for DNA duplex or the weaker contribution to H-rise than roll (inclination) for RNA and DRH duplexes (see the Pearson correlation coefficients in Table 3).

Figure 6.

(A–C) The relationships between H-rise and roll (A), between inclination and roll (B), and between roll and twist (C) for DNA-RNA hybrid, RNA, and DNA duplexes from the statistical analyses of MD trajectories, and error bars are obtained as standard errors of averages in each interval. (D) A schematic model at one basepair step for the relationship between roll and twist is shown. Because the sugar-phosphate backbone (green) is approximately inextensible, an increase in roll would cause a decrease in twist. To see this figure in color, go online.

Therefore, the above analyses clearly show that the different (very weak) twist-stretch coupling of DRH duplex is attributed the different basepair inclinations, as compared with DNA and RNA duplexes. The inclination of DRH duplex is between those of RNA and DNA duplexes and is closer to that of RNA duplex; thus, the twist-stretch coupling of DRH is also between those of RNA and DNA duplexes and appears close to that of RNA duplex. Because DNA and RNA duplexes have apparently negative and positive twist-stretch coupling, respectively, the DRH duplex has a very weakly positive twist-stretch coupling that is closer to that of RNA duplex.

Additionally, we examined the twist-stretch coupling of the DRH duplex under different stretching forces. As shown in Fig. S10, the twist-stretch coupling parameter dH-rise/dH-twist of the DRH duplex approximately keeps invariant in the regime of stretching force <∼10 pN, which would become more negative with the increase of stretching force, suggesting that the DRH duplex unwinds more strongly at higher force in the force regime of >∼10 pN. The “critical” force of ∼10 pN for the DRH duplex is between the values for DNA and RNA duplexes revealed by previous MD simulations and experiments that showed that the twist-stretch coupling almost keeps invariant in the force regime of <∼15 pN for a DNA duplex and in the force regime of <∼5–8 pN for an RNA duplex (31, 72).

Conclusions

In this work, microsecond (1 μs) all-atom MD simulations have been performed for DRH, RNA, and DNA duplexes to examine the structural flexibility of DRH duplex in stretching and twist-stretch coupling, in a comparative way with DNA and RNA duplexes. The major conclusions are listed as follows:

-

1)

Our analyses based on microsecond MD trajectories indicate that DRH duplex is closer to an A-form structure rather than a B-form structure, which may be attributed to the fact that the RNA strand is more rigid than the DNA strand, and we provided almost all the helical parameters for the DRH duplex in a comparative way with DNA and RNA duplexes.

-

2)

The stretch modulus S of the DRH duplex is ∼834 pN, a value between those of DNA and RNA duplexes and is closer to that of the RNA duplex. Such stretch modulus of the DRH duplex is attributed to the basepair inclination and slide, which are also between those of DNA and RNA duplexes and are closer to those of the RNA duplex.

-

3)

The DRH duplex exhibits very weak twist-stretch coupling (dH-rise/dH-twist ∼−0.06 nm/turn), whereas DNA and RNA duplexes exhibit apparently negative and positive twist-stretch coupling, respectively. Such different twist-stretch coupling is attributed to the fact that the basepair inclination of the DRH duplex is between those of DNA and RNA duplexes and is closer to that of the RNA duplex because the relationships between twist and H-rise are similar for DRH, DNA, and RNA duplexes.

The structure flexibility of a DRH duplex may be of related biological significance (88, 89). When a single-stranded RNA anneals to the complementary strand in its double-stranded DNA template, an R-loop would form, composed by a DRH duplex and a displaced single-stranded DNA (ssDNA). Recent high-throughput sequencing revealed that R-loops occupied up to 5% of the mammalian genome (88) and 8% of the budding yeast genome (89). In the R-loops, the displaced ssDNAs often contain G-rich sequences and form secondary structures. Thus, the extended DRH duplex is generally bent by the ssDNA, and consequently, the flexibility of the RDH duplex can play a critical role in the formation of R-loops (88, 89).

Our calculations on the stretch modulus and twist-stretch coupling agree well with the experimental measurements for DNA and RNA duplexes, and the calculated stretch modulus of DRH duplex is also in good accordance with the very recent experiments. However, until now, there is still a lack of experimental measurements for quantifying twist-stretch coupling of the DRH duplex. Thus, our calculation of the twist-stretch coupling of DRH duplex is still required to be validated in future experiment measurements. Furthermore, this work can be extensively expanded because the flexibility may be sensitive to ionic conditions, sequence, and temperature (30, 43), and these effects are deserved to be investigated separately. Nevertheless, based on our microsecond MD trajectories with new AMBER force fields, this work provides a quantitative characterization on extensive helical parameters, stretch modulus, and twist-stretch coupling for the DRH duplex and provides comprehensive analyses on the flexibility of the DRH duplex in stretching and twist-stretch coupling in a comparative way with DNA and RNA duplexes. This work will be very helpful for understanding the relative structures and relative flexibility of DRH, DNA, and RNA duplexes.

Author Contributions

Z.J.T., X.H.Z., J.H.L., and K.X. designed the research. J.H.L. and X.Z. performed the calculations. Z.J.T., J.H.L., X.Z., K.X., and L.B. analyzed the data. J.H.L., X.Z., X.H.Z., and Z.J.T. wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and reviewed the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Profs. Xiangyun Qiu (George Washington University), Shi-Jie Chen (University of Missouri), and Wenbing Zhang (Wuhan University) for valuable discussions.

This work is supported by the National Science Foundation of China grants (11575128, 11774272, and 11647312). The numerical calculations in this work were performed on the supercomputing system in the Super Computing Center of Wuhan University.

Editor: Tamar Schlick.

Footnotes

Ju-Hui Liu and Kun Xi contributed equally to this work.

Supporting Material can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpj.2019.05.018.

Contributor Information

Xinghua Zhang, Email: zhxh@whu.edu.cn.

Zhi-Jie Tan, Email: zjtan@whu.edu.cn.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Varmus H.E. Form and function of retroviral proviruses. Science. 1982;216:812–820. doi: 10.1126/science.6177038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Varmus, H. E. 1982. Form and function of retroviral proviruses. Science. 216:812-820. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Ogawa T., Okazaki T. Discontinuous DNA replication. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1980;49:421–457. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.49.070180.002225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Ogawa, T., and T. Okazaki. 1980. Discontinuous DNA replication. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 49:421-457. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Temin H.M. Reverse transcription in the eukaryotic genome: retroviruses, pararetroviruses, retrotransposons, and retrotranscripts. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1985;2:455–468. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Temin, H. M. 1985. Reverse transcription in the eukaryotic genome: retroviruses, pararetroviruses, retrotransposons, and retrotranscripts. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2:455-468. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Clayton D.A. Transcription and replication of animal mitochondrial DNAs. Int. Rev. Cytol. 1992;141:217–232. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)62067-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Clayton, D. A. 1992. Transcription and replication of animal mitochondrial DNAs. Int. Rev. Cytol. 141:217-232. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Rich A. Discovery of the hybrid helix and the first DNA-RNA hybridization. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:7693–7696. doi: 10.1074/JBC.X600003200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Rich, A. 2006. Discovery of the hybrid helix and the first DNA-RNA hybridization. J. Biol. Chem. 281:7693-7696. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Dean N.M., Bennett C.F. Antisense oligonucleotide-based therapeutics for cancer. Oncogene. 2003;22:9087–9096. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Dean, N. M., and C. F. Bennett. 2003. Antisense oligonucleotide-based therapeutics for cancer. Oncogene. 22:9087-9096. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Wu H., Lima W.F., Crooke S.T. Determination of the role of the human RNase H1 in the pharmacology of DNA-like antisense drugs. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:17181–17189. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311683200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Wu, H., W. F. Lima, …, S. T. Crooke. 2004. Determination of the role of the human RNase H1 in the pharmacology of DNA-like antisense drugs. J. Biol. Chem. 279:17181-17189. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Gavette J.V., Stoop M., Krishnamurthy R. RNA-DNA chimeras in the context of an RNA world transition to an RNA/DNA world. Angew. Chem. Int.Engl. 2016;55:13204–13209. doi: 10.1002/anie.201607919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Gavette, J. V., M. Stoop, …, R. Krishnamurthy. 2016. RNA-DNA chimeras in the context of an RNA world transition to an RNA/DNA world. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 55:13204-13209. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Dias N., Stein C.A. Antisense oligonucleotides: basic concepts and mechanisms. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2002;1:347–355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Dias, N., and C. A. Stein. 2002. Antisense oligonucleotides: basic concepts and mechanisms. Mol. Cancer Ther. 1:347-355. [PubMed]

- 10.Salazar M., Fedoroff O.Y., Reid B.R. The DNA strand in DNA.RNA hybrid duplexes is neither B-form nor A-form in solution. Biochemistry. 1993;32:4207–4215. doi: 10.1021/bi00067a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Salazar, M., O. Y. Fedoroff, …, B. R. Reid. 1993. The DNA strand in DNA.RNA hybrid duplexes is neither B-form nor A-form in solution. Biochemistry. 32:4207-4215. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Hantz E., Larue V., Huynh Dinh T. Solution conformation of an RNA--DNA hybrid duplex containing a pyrimidine RNA strand and a purine DNA strand. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2001;28:273–284. doi: 10.1016/s0141-8130(01)00123-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Hantz, E., V. Larue, …, T. Huynh Dinh. 2001. Solution conformation of an RNA--DNA hybrid duplex containing a pyrimidine RNA strand and a purine DNA strand. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 28:273-284. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Lesnik E.A., Freier S.M. Relative thermodynamic stability of DNA, RNA, and DNA:RNA hybrid duplexes: relationship with base composition and structure. Biochemistry. 1995;34:10807–10815. doi: 10.1021/bi00034a013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Lesnik, E. A., and S. M. Freier. 1995. Relative thermodynamic stability of DNA, RNA, and DNA:RNA hybrid duplexes: relationship with base composition and structure. Biochemistry. 34:10807-10815. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Xiong Y., Sundaralingam M. Crystal structure of a DNA.RNA hybrid duplex with a polypurine RNA r(gaagaagag) and a complementary polypyrimidine DNA d(CTCTTCTTC) Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:2171–2176. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.10.2171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Xiong, Y., and M. Sundaralingam. 2000. Crystal structure of a DNA.RNA hybrid duplex with a polypurine RNA r(gaagaagag) and a complementary polypyrimidine DNA d(CTCTTCTTC). Nucleic Acids Res. 28:2171-2176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Han G.W., Kopka M.L., Dickerson R.E. Crystal structure of an RNA.DNA hybrid reveals intermolecular intercalation: dimer formation by base-pair swapping. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:9214–9219. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1533326100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Han, G. W., M. L. Kopka, …, R. E. Dickerson. 2003. Crystal structure of an RNA.DNA hybrid reveals intermolecular intercalation: dimer formation by base-pair swapping. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 100:9214-9219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Nowotny M., Gaidamakov S.A., Yang W. Crystal structures of RNase H bound to an RNA/DNA hybrid: substrate specificity and metal-dependent catalysis. Cell. 2005;121:1005–1016. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Nowotny, M., S. A. Gaidamakov, …, W. Yang. 2005. Crystal structures of RNase H bound to an RNA/DNA hybrid: substrate specificity and metal-dependent catalysis. Cell. 121:1005-1016. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Noy A., Pérez A., Orozco M. Structure, recognition properties, and flexibility of the DNA.RNA hybrid. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:4910–4920. doi: 10.1021/ja043293v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Noy, A., A. Perez, …, M. Orozco. 2005. Structure, recognition properties, and flexibility of the DNA.RNA hybrid. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127:4910-4920. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Huang Y., Chen C., Russu I.M. Dynamics and stability of individual base pairs in two homologous RNA-DNA hybrids. Biochemistry. 2009;48:3988–3997. doi: 10.1021/bi900070f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Huang, Y., C. Chen, and I. M. Russu. 2009. Dynamics and stability of individual base pairs in two homologous RNA-DNA hybrids. Biochemistry. 48:3988-3997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Suresh G., Priyakumar U.D. DNA-RNA hybrid duplexes with decreasing pyrimidine content in the DNA strand provide structural snapshots for the A- to B-form conformational transition of nucleic acids. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2014;16:18148–18155. doi: 10.1039/c4cp02478h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Suresh, G., and U. D. Priyakumar. 2014. DNA-RNA hybrid duplexes with decreasing pyrimidine content in the DNA strand provide structural snapshots for the A- to B-form conformational transition of nucleic acids. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 16:18148-18155. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Priyakumar U.D., Mackerell A.D., Jr. Atomic detail investigation of the structure and dynamics of DNA.RNA hybrids: a molecular dynamics study. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2008;112:1515–1524. doi: 10.1021/jp709827m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Priyakumar, U. D., and A. D. Mackerell, Jr. 2008. Atomic detail investigation of the structure and dynamics of DNA.RNA hybrids: a molecular dynamics study. J. Phys. Chem. B. 112:1515-1524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Pramanik S., Nagatoishi S., Sugimoto N. Conformational flexibility influences degree of hydration of nucleic acid hybrids. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2011;115:13862–13872. doi: 10.1021/jp207856p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Pramanik, S., S. Nagatoishi, …, N. Sugimoto. 2011. Conformational flexibility influences degree of hydration of nucleic acid hybrids. J. Phys. Chem. B. 115:13862-13872. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Rauzan B., McMichael E., Deckert A.A. Kinetics and thermodynamics of DNA, RNA, and hybrid duplex formation. Biochemistry. 2013;52:765–772. doi: 10.1021/bi3013005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Rauzan, B., E. McMichael, …, A. A. Deckert. 2013. Kinetics and thermodynamics of DNA, RNA, and hybrid duplex formation. Biochemistry. 52:765-772. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Baumann C.G., Smith S.B., Bustamante C. Ionic effects on the elasticity of single DNA molecules. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:6185–6190. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.12.6185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Baumann, C. G., S. B. Smith, …, C. Bustamante. 1997. Ionic effects on the elasticity of single DNA molecules. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 94:6185-6190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Wenner J.R., Williams M.C., Bloomfield V.A. Salt dependence of the elasticity and overstretching transition of single DNA molecules. Biophys. J. 2002;82:3160–3169. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75658-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Wenner, J. R., M. C. Williams, …, V. A. Bloomfield. 2002. Salt dependence of the elasticity and overstretching transition of single DNA molecules. Biophys. J. 82:3160-3169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Zhang X., Chen H., Yan J. Two distinct overstretched DNA structures revealed by single-molecule thermodynamics measurements. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:8103–8108. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1109824109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Zhang, X., H. Chen, …, J. Yan. 2012. Two distinct overstretched DNA structures revealed by single-molecule thermodynamics measurements. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 109:8103-8108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Zhang X., Chen H., Yan J. Revealing the competition between peeled ssDNA, melting bubbles, and S-DNA during DNA overstretching by single-molecule calorimetry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:3865–3870. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1213740110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Zhang, X., H. Chen, …, J. Yan. 2013. Revealing the competition between peeled ssDNA, melting bubbles, and S-DNA during DNA overstretching by single-molecule calorimetry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 110:3865-3870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Kosikov K.M., Gorin A.A., Olson W.K. DNA stretching and compression: large-scale simulations of double helical structures. J. Mol. Biol. 1999;289:1301–1326. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Kosikov, K. M., A. A. Gorin, …, W. K. Olson. 1999. DNA stretching and compression: large-scale simulations of double helical structures. J. Mol. Biol. 289:1301-1326. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Manning G.S. The persistence length of DNA is reached from the persistence length of its null isomer through an internal electrostatic stretching force. Biophys. J. 2006;91:3607–3616. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.089029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Manning, G. S. 2006. The persistence length of DNA is reached from the persistence length of its null isomer through an internal electrostatic stretching force. Biophys. J. 91:3607-3616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Mathew-Fenn R.S., Das R., Harbury P.A. Remeasuring the double helix. Science. 2008;322:446–449. doi: 10.1126/science.1158881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Mathew-Fenn, R. S., R. Das, and P. A. Harbury. 2008. Remeasuring the double helix. Science. 322:446-449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Gore J., Bryant Z., Bustamante C. DNA overwinds when stretched. Nature. 2006;442:836–839. doi: 10.1038/nature04974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Gore, J., Z. Bryant, …, C. Bustamante. 2006. DNA overwinds when stretched. Nature. 442:836-839. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Herrero-Galán E., Fuentes-Perez M.E., Arias-Gonzalez J.R. Mechanical identities of RNA and DNA double helices unveiled at the single-molecule level. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:122–131. [Google Scholar]; Herrero-Galan, E., M. E. Fuentes-Perez, …, J. R. Arias-Gonzalez. 2013. Mechanical identities of RNA and DNA double helices unveiled at the single-molecule level. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135:122-131.

- 31.Lipfert J., Skinner G.M., Dekker N.H. Double-stranded RNA under force and torque: similarities to and striking differences from double-stranded DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:15408–15413. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1407197111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Lipfert, J., G. M. Skinner, …, N. H. Dekker. 2014. Double-stranded RNA under force and torque: similarities to and striking differences from double-stranded DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 111:15408-15413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Zoli M. Flexibility of short DNA helices under mechanical stretching. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2016;18:17666–17677. doi: 10.1039/c6cp02981g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Zoli, M. 2016. Flexibility of short DNA helices under mechanical stretching. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 18:17666-17677. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Zoli M. Thermodynamics of twisted DNA with solvent interaction. J. Chem. Phys. 2011;135:115101. doi: 10.1063/1.3631564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Zoli, M. 2011. Thermodynamics of twisted DNA with solvent interaction. J. Chem. Phys. 135:115101. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Hagerman P.J. Flexibility of RNA. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 1997;26:139–156. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.26.1.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Hagerman, P. J. 1997. Flexibility of RNA. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 26:139-156. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Abels J.A., Moreno-Herrero F., Dekker N.H. Single-molecule measurements of the persistence length of double-stranded RNA. Biophys. J. 2005;88:2737–2744. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.052811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Abels, J. A., F. Moreno-Herrero, …, N. H. Dekker. 2005. Single-molecule measurements of the persistence length of double-stranded RNA. Biophys. J. 88:2737-2744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Lionnet T., Joubaud S., Croquette V. Wringing out DNA. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2006;96:178102. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.96.178102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Lionnet, T., S. Joubaud, …, V. Croquette. 2006. Wringing out DNA. Phys. Rev. Lett. 96:178102. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Katz A.M., Tolokh I.S., Pollack L. Spermine condenses DNA, but not RNA duplexes. Biophys. J. 2017;112:22–30. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2016.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Katz, A. M., I. S. Tolokh, …, L. Pollack. 2017. Spermine condenses DNA, but not RNA duplexes. Biophys. J. 112:22-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Strahs D., Schlick T. A-Tract bending: insights into experimental structures by computational models. J. Mol. Biol. 2000;301:643–663. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Strahs, D., and T. Schlick. 2000. A-Tract bending: insights into experimental structures by computational models. J. Mol. Biol. 301:643-663. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Jian H., Vologodskii A.V., Schlick T. A combined wormlike-chain and bead model for dynamic simulations of long linear DNA. J. Comput. Phys. 1997;136:168–179. [Google Scholar]; Jian, H., A. V. Vologodskii, and T. Schlick. 1997. A combined wormlike-chain and bead model for dynamic simulations of long linear DNA. J. Comput. Phys. 136:168-179.

- 40.Shi Y.Z., Jin L., Tan Z.J. Predicting 3D structure, flexibility, and stability of RNA hairpins in monovalent and divalent Ion solutions. Biophys. J. 2015;109:2654–2665. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2015.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Shi, Y. Z., L. Jin, …, Z. J. Tan. 2015. Predicting 3D structure, flexibility, and stability of RNA hairpins in monovalent and divalent Ion solutions. Biophys. J. 109:2654-2665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Zhang Y., Zhang J., Wang W. Atomistic analysis of pseudoknotted RNA unfolding. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:6882–6885. doi: 10.1021/ja1109425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Zhang, Y., J. Zhang, and W. Wang. 2011. Atomistic analysis of pseudoknotted RNA unfolding. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133:6882-6885. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Bian Y., Tan C., Wang W. Atomistic picture for the folding pathway of a hybrid-1 type human telomeric DNA G-quadruplex. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2014;10:e1003562. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Bian, Y., C. Tan, …, W. Wang. 2014. Atomistic picture for the folding pathway of a hybrid-1 type human telomeric DNA G-quadruplex. PLoS Comput. Biol. 10:e1003562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Bao L., Zhang X., Tan Z.J. Flexibility of nucleic acids: from DNA to RNA. Chin. Phys. B. 2016;25:018703. [Google Scholar]; Bao, L., X. Zhang, …, Z. J. Tan. 2016. Flexibility of nucleic acids: from DNA to RNA. Chin. Phys. B. 25:018703.

- 44.Sutton J.L., Pollack L. Tuning RNA flexibility with helix length and junction sequence. Biophys. J. 2015;109:2644–2653. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2015.10.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Sutton, J. L., and L. Pollack. 2015. Tuning RNA flexibility with helix length and junction sequence. Biophys. J. 109:2644-2653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Zhang X., Bao L., Tan Z.J. Radial distribution function of semiflexible oligomers with stretching flexibility. J. Chem. Phys. 2017;147:054901. doi: 10.1063/1.4991689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Zhang, X., L. Bao, …, Z. J. Tan. 2017. Radial distribution function of semiflexible oligomers with stretching flexibility. J. Chem. Phys. 147:054901. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 46.Jin L., Shi Y.Z., Tan Z.J. Modeling structure, stability, and flexibility of double-stranded RNAs in salt solutions. Biophys. J. 2018;115:1403–1416. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2018.08.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Jin, L., Y. Z. Shi, …, Z. J. Tan. 2018. Modeling structure, stability, and flexibility of double-stranded RNAs in salt solutions. Biophys. J. 115:1403-1416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Faustino I., Pérez A., Orozco M. Toward a consensus view of duplex RNA flexibility. Biophys. J. 2010;99:1876–1885. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.06.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Faustino, I., A. Perez, and M. Orozco. 2010. Toward a consensus view of duplex RNA flexibility. Biophys. J. 99:1876-1885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Wu Y.Y., Bao L., Tan Z.J. Flexibility of short DNA helices with finite-length effect: from base pairs to tens of base pairs. J. Chem. Phys. 2015;142:125103. doi: 10.1063/1.4915539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Wu, Y. Y., L. Bao, …, Z. J. Tan. 2015. Flexibility of short DNA helices with finite-length effect: from base pairs to tens of base pairs. J. Chem. Phys. 142:125103. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 49.Tolokh I.S., Pabit S.A., Onufriev A.V. Why double-stranded RNA resists condensation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:10823–10831. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Tolokh, I. S., S. A. Pabit, …, A. V. Onufriev. 2014. Why double-stranded RNA resists condensation. Nucleic Acids Res. 42:10823-10831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 50.Bao L., Zhang X., Tan Z.J. Understanding the relative flexibility of RNA and DNA duplexes: stretching and twist-stretch coupling. Biophys. J. 2017;112:1094–1104. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2017.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Bao, L., X. Zhang, …, Z. J. Tan. 2017. Understanding the relative flexibility of RNA and DNA duplexes: stretching and twist-stretch coupling. Biophys. J. 112:1094-1104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51.Liebl K., Drsata T., Zacharias M. Explaining the striking difference in twist-stretch coupling between DNA and RNA: a comparative molecular dynamics analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:10143–10156. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Liebl, K., T. Drsata, …, M. Zacharias. 2015. Explaining the striking difference in twist-stretch coupling between DNA and RNA: a comparative molecular dynamics analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 43:10143-10156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 52.Pettersen E.F., Goddard T.D., Ferrin T.E. UCSF Chimera--a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 2004;25:1605–1612. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Pettersen, E. F., T. D. Goddard, …, T. E. Ferrin. 2004. UCSF Chimera--a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 25:1605-1612. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 53.Joung I.S., Cheatham T.E., III Determination of alkali and halide monovalent ion parameters for use in explicitly solvated biomolecular simulations. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2008;112:9020–9041. doi: 10.1021/jp8001614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Joung, I. S., and T. E. Cheatham III. 2008. Determination of alkali and halide monovalent ion parameters for use in explicitly solvated biomolecular simulations. J. Phys. Chem. B. 112:9020-9041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 54.Shi Y.Z., Wang F.H., Tan Z.J. A coarse-grained model with implicit salt for RNAs: predicting 3D structure, stability and salt effect. J. Chem. Phys. 2014;141:105102. doi: 10.1063/1.4894752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Shi, Y. Z., F. H. Wang, …, Z. J. Tan. 2014. A coarse-grained model with implicit salt for RNAs: predicting 3D structure, stability and salt effect. J. Chem. Phys. 141:105102. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 55.Wu Y.Y., Zhang Z.L., Tan Z.J. Multivalent ion-mediated nucleic acid helix-helix interactions: RNA versus DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:6156–6165. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Wu, Y. Y., Z. L. Zhang, …, Z. J. Tan. 2015. Multivalent ion-mediated nucleic acid helix-helix interactions: RNA versus DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 43:6156-6165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 56.Wang J., Xiao Y. Types and concentrations of metal ions affect local structure and dynamics of RNA. Phys. Rev. E. 2016;94:040401. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.94.040401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Wang, J., and Y. Xiao. 2016. Types and concentrations of metal ions affect local structure and dynamics of RNA. Phys. Rev. E. 94:040401. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 57.Tan Z.J., Chen S.J. Nucleic acid helix stability: effects of salt concentration, cation valence and size, and chain length. Biophys. J. 2006;90:1175–1190. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.070904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Tan, Z. J., and S. J. Chen. 2006. Nucleic acid helix stability: effects of salt concentration, cation valence and size, and chain length. Biophys. J. 90:1175-1190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 58.Tan Z.J., Chen S.J. RNA helix stability in mixed Na+/Mg2+ solution. Biophys. J. 2007;92:3615–3632. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.100388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Tan, Z. J., and S. J. Chen. 2007. RNA helix stability in mixed Na+/Mg2+ solution. Biophys. J. 92:3615-3632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 59.Pabit S.A., Qiu X., Pollack L. Both helix topology and counterion distribution contribute to the more effective charge screening in dsRNA compared with dsDNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:3887–3896. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Pabit, S. A., X. Qiu, …, L. Pollack. 2009. Both helix topology and counterion distribution contribute to the more effective charge screening in dsRNA compared with dsDNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 37:3887-3896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 60.Drozdetski A.V., Tolokh I.S., Onufriev A.V. Opposing effects of multivalent ions on the flexibility of DNA and RNA. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2016;117:028101. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.117.028101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Drozdetski, A. V., I. S. Tolokh, …, A. V. Onufriev. 2016. Opposing effects of multivalent ions on the flexibility of DNA and RNA. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117:028101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 61.Shi Y.Z., Jin L., Tan Z.J. Predicting 3D structure and stability of RNA pseudoknots in monovalent and divalent ion solutions. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2018;14:e1006222. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1006222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Shi, Y. Z., L. Jin, …, Z. J. Tan. 2018. Predicting 3D structure and stability of RNA pseudoknots in monovalent and divalent ion solutions. PLoS Comput. Biol. 14:e1006222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 62.York D.M., Darden T.A., Pedersen L.G. The effect of long-range electrostatic interactions in simulations of macromolecular crystals: a comparison of the Ewald and truncated list methods. J. Chem. Phys. 1993;99:8345–8348. [Google Scholar]; York, D. M., T. A. Darden, and L. G. Pedersen. 1993. The effect of long-range electrostatic interactions in simulations of macromolecular crystals: a comparison of the Ewald and truncated list methods. J. Chem. Phys. 99:8345-8348.

- 63.Miyamoto S., Kollman P.A. Settle: an analytical version of the SHAKE and RATTLE algorithm for rigid water models. J. Comput. Chem. 1992;13:952–962. [Google Scholar]; Miyamoto, S., and P. A. Kollman. 1992. Settle: an analytical version of the SHAKE and RATTLE algorithm for rigid water models. J. Comput. Chem. 13:952-962.

- 64.Gong Z., Xiao Y., Xiao Y. RNA stability under different combinations of amber force fields and solvation models. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2010;28:431–441. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2010.10507372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Gong, Z., Y. Xiao, and Y. Xiao. 2010. RNA stability under different combinations of amber force fields and solvation models. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 28:431-441. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 65.Pérez A., Marchán I., Orozco M. Refinement of the AMBER force field for nucleic acids: improving the description of α/γ conformers. Biophys. J. 2007;92:3817–3829. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.097782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Perez, A., I. Marchan, …, M. Orozco. 2007. Refinement of the AMBER force field for nucleic acids: improving the description of α/γ conformers. Biophys. J. 92:3817-3829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 66.Zgarbová M., Otyepka M., Jurečka P. Refinement of the Cornell et al. Nucleic acids force field based on reference quantum chemical calculations of glycosidic torsion profiles. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2011;7:2886–2902. doi: 10.1021/ct200162x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Zgarbova, M., M. Otyepka, …, P. Jurečka. 2011. Refinement of the Cornell et al. Nucleic acids force field based on reference quantum chemical calculations of glycosidic torsion profiles. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 7:2886-2902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 67.Ivani I., Dans P.D., Orozco M. Parmbsc1: a refined force field for DNA simulations. Nat. Methods. 2016;13:55–58. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Ivani, I., P. D. Dans, …, M. Orozco. 2016. Parmbsc1: a refined force field for DNA simulations. Nat. Methods. 13:55-58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 68.Schlick T. Springer; New York: 2002. Molecular Modeling and Simulation: An Interdisciplinary Duide: Interdisciplinary Applied Mathematics. [Google Scholar]; Schlick, T. 2002. Molecular Modeling and Simulation: An Interdisciplinary Duide: Interdisciplinary Applied Mathematics: Springer, New York.

- 69.Hess B., Kutzner C., Lindahl E. GROMACS 4: algorithms for highly efficient, load-balanced, and scalable molecular simulation. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2008;4:435–447. doi: 10.1021/ct700301q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Hess, B., C. Kutzner, …, E. Lindahl. 2008. GROMACS 4: algorithms for highly efficient, load-balanced, and scalable molecular simulation. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 4:435-447. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 70.Jorgensen W.L., Chandrasekhar J., Klein M.L. Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating liquid water. J. Chem. Phys. 1983;79:926–935. [Google Scholar]; Jorgensen, W. L., J. Chandrasekhar, …, M. L. Klein. 1983. Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating liquid water. J. Chem. Phys. 79:926-935.

- 71.Cong P., Dai L., Yan J. Revisiting the anomalous bending elasticity of sharply bent DNA. Biophys. J. 2015;109:2338–2351. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2015.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Cong, P., L. Dai, …, J. Yan. 2015. Revisiting the anomalous bending elasticity of sharply bent DNA. Biophys. J. 109:2338-2351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 72.Marin-Gonzalez A., Vilhena J.G., Moreno-Herrero F. Understanding the mechanical response of double-stranded DNA and RNA under constant stretching forces using all-atom molecular dynamics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2017;114:7049–7054. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1705642114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Marin-Gonzalez, A., J. G. Vilhena, …, F. Moreno-Herrero. 2017. Understanding the mechanical response of double-stranded DNA and RNA under constant stretching forces using all-atom molecular dynamics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 114:7049-7054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 73.Hanson R.M., Lu X.J. DSSR-enhanced visualization of nucleic acid structures in Jmol. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:W528–W533. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Hanson, R. M., and X. J. Lu. 2017. DSSR-enhanced visualization of nucleic acid structures in Jmol. Nucleic Acids Res. 45:W528-W533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 74.Lu X.J., Olson W.K. 3DNA: a software package for the analysis, rebuilding and visualization of three-dimensional nucleic acid structures. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:5108–5121. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Lu, X. J., and W. K. Olson. 2003. 3DNA: a software package for the analysis, rebuilding and visualization of three-dimensional nucleic acid structures. Nucleic Acids Res. 31:5108-5121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 75.Zhang Z.L., Wu Y.Y., Tan Z.J. Divalent ion-mediated DNA-DNA interactions: a comparative study of triplex and duplex. Biophys. J. 2017;113:517–528. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2017.06.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Zhang, Z. L., Y. Y. Wu, …, Z. J. Tan. 2017. Divalent ion-mediated DNA-DNA interactions: a comparative study of triplex and duplex. Biophys. J. 113:517-528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 76.Wang Y., Wang Z., Zhang W. The nearest neighbor and next nearest neighbor effects on the thermodynamic and kinetic properties of RNA base pair. J. Chem. Phys. 2018;148:045101. doi: 10.1063/1.5013282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Wang, Y., Z. Wang, …, W. Zhang. 2018. The nearest neighbor and next nearest neighbor effects on the thermodynamic and kinetic properties of RNA base pair. J. Chem. Phys. 148:045101. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 77.Wang Y., Gong S., Zhang W. The thermodynamics and kinetics of a nucleotide base pair. J. Chem. Phys. 2016;144:115101. doi: 10.1063/1.4944067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Wang, Y., S. Gong, …, W. Zhang. 2016. The thermodynamics and kinetics of a nucleotide base pair. J. Chem. Phys. 144:115101. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 78.Xu X., Yu T., Chen S.J. Understanding the kinetic mechanism of RNA single base pair formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2016;113:116–121. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1517511113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Xu, X., T. Yu, and S. J. Chen. 2016. Understanding the kinetic mechanism of RNA single base pair formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 113:116-121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 79.Hurst T., Xu X., Chen S.J. Quantitative understanding of SHAPE mechanism from RNA structure and dynamics analysis. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2018;122:4771–4783. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.8b00575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Hurst, T., X. Xu, …, S. J. Chen. 2018. Quantitative understanding of SHAPE mechanism from RNA structure and dynamics analysis. J. Phys. Chem. B. 122:4771-4783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 80.Lavery R., Sklenar H. Defining the structure of irregular nucleic acids: conventions and principles. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 1989;6:655–667. doi: 10.1080/07391102.1989.10507728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Lavery, R., and H. Sklenar. 1989. Defining the structure of irregular nucleic acids: conventions and principles. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 6:655-667. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 81.Xi K., Wang F.H., Tan Z.J. Competitive binding of Mg2+ and Na+ ions to nucleic acids: from helices to tertiary structures. Biophys. J. 2018;114:1776–1790. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2018.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Xi, K., F. H. Wang, …, Z. J. Tan. 2018. Competitive binding of Mg2+ and Na+ ions to nucleic acids: from helices to tertiary structures. Biophys. J. 114:1776-1790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 82.Lavery R., Moakher M., Zakrzewska K. Conformational analysis of nucleic acids revisited: curves+ Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:5917–5929. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Lavery, R., M. Moakher, …, K. Zakrzewska. 2009. Conformational analysis of nucleic acids revisited: curves+. Nucleic Acids Res. 37:5917-5929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 83.Zoli M. End-to-end distance and contour length distribution functions of DNA helices. J. Chem. Phys. 2018;148:214902. doi: 10.1063/1.5021639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Zoli, M. 2018. End-to-end distance and contour length distribution functions of DNA helices. J. Chem. Phys. 148:214902. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 84.Calladine C.R., Drew H. Academic Press; Cambridge, UK: 1997. Understanding DNA: The Molecule and How it Works. [Google Scholar]; Calladine, C. R., and H. Drew. 1997. Understanding DNA: The Molecule and How it Works: Academic Press, Cambridge, UK.

- 85.Noy A., Golestanian R. Length scale dependence of DNA mechanical properties. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012;109:228101. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.109.228101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Noy, A., and R. Golestanian. 2012. Length scale dependence of DNA mechanical properties. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109:228101. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 86.Benesty J., Chen J., Cohen I. Volume 2. Springer; 2009. Pearson correlation coefficient. (Noise Reduction in Speech Processing, Springer Topics in Signal Processing). [Google Scholar]; Benesty, J., J. Chen, …, I. Cohen. 2009. Pearson correlation coefficient. In Noise Reduction in Speech Processing, Springer Topics in Signal Processing, Volume 2, (Springer).