Abstract

Background: Ensuring the strength of the physician workforce is essential to optimizing patient care. Challenges that undermine the profession include inequities in advancement, high levels of burnout, reduced career duration, and elevated risk for mental health problems, including suicide. This narrative review explores whether physicians within four subpopulations represented in the workforce at levels lower than predicted from their numbers in the general population—women, racial and ethnic minorities in medicine, sexual and gender minorities, and people with disabilities—are at elevated risk for these problems, and if present, how these problems might be addressed to support patient care. In essence, the underlying question this narrative review explores is as follows: Do physician workforce disparities affect patient care? While numerous articles and high-profile reports have examined the relationship between workforce diversity and patient care, to our knowledge, this is the first review to examine the important relationship between diversity-related workforce disparities and patient care.

Methods: Five databases (PubMed, the Cochrane Library of Systematic Reviews, EMBASE, Web of Knowledge, and EBSCO Discovery Service) were searched by a librarian. Additional resources were included by authors, as deemed relevant to the investigation.

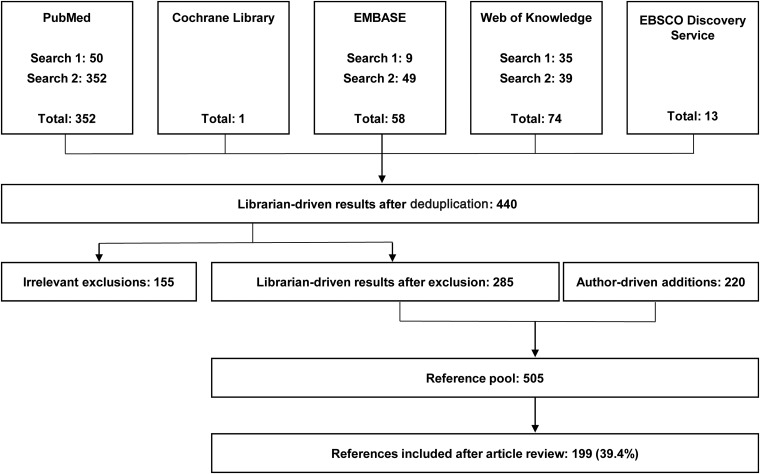

Results: The initial database searches identified 440 potentially relevant articles. Articles were categorized according to subtopics, including (1) underrepresented physicians and support for vulnerable patient populations; (2) factors that could exacerbate the projected physician deficit; (3) methods of addressing disparities among underrepresented physicians to support patient care; or (4) excluded (n=155). The authors identified another 220 potentially relevant articles. Of 505 potentially relevant articles, 199 (39.4%) were included in this review.

Conclusions: This report demonstrates an important gap in the literature regarding the impact of physician workforce disparities and their effect on patient care. This is a critical public health issue and should be urgently addressed in future research and considered in clinical practice and policy decision-making.

Keywords: women in medicine, women physicians, Black physicians, Hispanic physicians, physician burnout

Introduction

Ensuring the strength of the physician workforce is essential to optimizing patient care. Yet, current projections show there will be a deficit of between 42,600 and 121,300 physicians by 2030 in the United States, with the majority of this deficit localized to primary care providers.1 Moreover, “If underserved populations had care utilization patterns similar to populations with fewer access barriers, demand for physicians could rise substantially.”1 Even as the demand for health services rises, major problems exist in the physician workforce, including inadequate diversity,2–5 decreased recruitment of underrepresented minorities,6 decreased recruitment of physicians into nonprimary care specialties (e.g., surgical specialties and other nonmedical specialties such as psychiatry and pathology),1 inadequate funding and/or legislative/societal support for funding for physician training,7,8 inequities in advancement,9 attrition,10 high levels of burnout,11 an aging physician population,1 and elevated suicide risk.12

Diversity of the physician workforce has been the subject of numerous reports and studies. Generally, the representation of physicians identifying with four populations is at levels lower than predicted from their numbers in the general population: women, racial and ethnic minorities in medicine, sexual and gender minorities, and people with disabilities. This narrative review explores the role of physicians from these underrepresented groups in patient care, whether physicians from these groups are at elevated risk for problems that could exacerbate the projected physician deficit, and if present, how these problems may be addressed to both support physicians and enhance patient care, especially for the most vulnerable populations.

In essence, the underlying question this narrative explores is as follows: Do physician workforce disparities affect patient care? While numerous articles and high-profile reports have examined the relationship between workforce diversity and patient care,2,13 to our knowledge, this is the first review to examine the important relationship between diversity-related workforce disparities and patient care. Our findings are aimed at informing future research, policy, and practice.

Methods

Five databases (PubMed, the Cochrane Library of Systematic Reviews, EMBASE, Web of Knowledge, and EBSCO Discovery Service) were searched by a medical librarian using appropriate search terms for each database (Table 1) on March 5, 2018. The search was English language and included all reports to date. Additional resources were included by authors as deemed relevant to the investigation.

Table 1.

Key Search Terms and Results

| Database | Search date | Primary search terms | Secondary search terms | Initial results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PubMed | March 5, 2018 | “health status disparities”[mesh] or health status disparities[tiab] or “healthcare disparities”[mesh] or healthcare disparities[tiab] or health disparity[tiab] or health disparities[tiab] or “minority health”[mesh] or minority health[tiab] |

“physicians, women”[mesh] or “dentists, women”[mesh] or women physicians[tiab] or women dentists[tiab] or women in medicine[tiab] or woman physician[tiab] or woman dentist[tiab] or woman doctor[tiab] or woman dentist[tiab] or female doctor[tiab] or female dentist[tiab] or female doctors[tiab] or female dentists[tiab] or minority physicians[tiab] or minority physician[tiab] or hispanic physicians[tiab] or african physician[tiab] or african physicians[tiab] or african american physician[tiab] or african american physicians[tiab] or black physician[tiab] or black physicians[tiab] or native american physicians[tiab] |

50 |

| PubMed | March 5, 2018 | “practice patterns, physicians”[mesh] or practice patterns[tiab] |

“physicians, women”[mesh] or “dentists, women”[mesh] or women physicians[tiab] or women dentists[tiab] or women in medicine[tiab] or woman physician[tiab] or woman dentist[tiab] or woman doctor[tiab] or woman dentist[tiab] or female doctor[tiab] or female dentist[tiab] or female doctors[tiab] or female dentists[tiab] or minority physicians[tiab] or minority physician[tiab] or hispanic physicians[tiab] or african physician[tiab] or african physicians[tiab] or african american physician[tiab] or african american physicians[tiab] or black physician[tiab] or black physicians[tiab] or native american physicians[tiab] |

302 |

| Cochrane Library | March 5, 2018 | “healthcare disparities” | “physicians, women” | 1 |

| EMBASE | March 5, 2018 | “health disparity”/exp or “health disparity” or “health disparities” or “minority health” or “health status disparity”’ or “health status disparities” or “health status disparity” or “healthcare disparities” or “healthcare disparity” |

“female physician”/exp or “female physician” or “female physicians” or “woman physician” or “women physicians” or “minority physician” or “black physician” or “black physicians” or “black doctor” or “black doctors” or “african american physician” or “african american physicians” or “hispanic doctor” or “hispanic doctors” or “hispanic physician” or “hispanic physicians” or “female dentist” or “female dentists”’ or “woman dentist” or “women dentists” and ([embase]/lim not [embase]/lim and [medline]/lim) |

9 |

| EMBASE | March 5, 2018 | “clinical practice”/exp or “clinical practice” |

“female physician”/exp or “female physician” or “female physicians” or “woman physician” or “women physicians” or “minority physician” or “black physician” or “black physicians” or “black doctor” or “black doctors” or “african american physician” or “african american physicians” or “hispanic doctor” or “hispanic doctors” or “hispanic physician” or “hispanic physicians” or “female dentist” or “female dentists” or “woman dentist” or “women dentists” and ([embase]/lim not [embase]/lim and [medline]/lim |

49 |

| Web of Knowledge | March 5, 2018 | “health status disparities” or “healthcare disparities” or “health disparity” or “health disparities” or “minority health” |

“women physicians” or “women dentists” or “women in medicine” or “woman physician” or “woman dentist” or “woman doctor” or “woman dentists” or “female doctor” or “female dentist” or “female doctors” or “female dentists” or “minority physicians” or “minority physician” or “hispanic physicians” or “african physician” or “african physicians” or “african american physician” or “african american physicians” or “black physician” or “black physicians” or “native american physicians” |

35 |

| Web of Knowledge | March 5, 2018 | “physician practice patterns” or “practice patterns” |

“women physicians” or “women dentists” or “women in medicine” or “woman physician” or “woman dentist” or “woman doctor” or “woman dentists” or “female doctor” or “female dentist” or “female doctors” or “female dentists” or “minority physicians” or “minority physician” or “hispanic physicians” or “african physician” or “african physicians” or “african american physician” or “african american physicians” or “black physician” or “black physicians” or “native american physicians” |

39 |

| EBSCO Discovery Service | women n3 physicians | “healthcare disparities” | Librarian selected 13 from 5140 results |

[mesh], search for keywords among; [tiab], search for keywords in title and abstract; /exp, search for keywords among lower levels of the topic hierarchy; and [embase]/lim and [embase]/lim not [embase]/lim, search for articles containing keywords in EMBASE that are not also in Medline; N3, search for keywords within three words of each other.

Institutional review board approval was not required for this study, a review of the literature, as it did not involve participants.

Results

After deduplication, the initial database searches identified 440 potentially relevant articles (Fig. 1). Articles were categorized according to subtopics, including (1) underrepresented physicians and support for vulnerable patient populations; (2) factors that could exacerbate the projected physician deficit; (3) methods of addressing disparities among underrepresented physicians to support patient care; or (4) excluded (n=155). After exclusion, 285 potentially relevant articles identified by the librarian-driven search remained. To these, the authors added another 220 potentially relevant articles. Of the 505 potentially relevant articles identified by the medical librarian or authors, 199 (39.4%) were cited because they contained information directly related to the topics included in this review.

FIG. 1.

Literature inclusion and exclusion process.

Definitions of key abbreviations and terms are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Definitions of Key Abbreviations and Terms

| Term | Description |

|---|---|

| AAMC | Association of American Medical Colleges |

| Burnout | “A state of physical or emotional exhaustion associated with chronic workplace stress that involves a sense of reduced accomplishment and loss of personal identity”136 |

| Cultural competency | “The ability to interact effectively with people of different cultures”137 and “be respectful and responsive to the health beliefs and practices—and cultural and linguistic needs—of diverse population groups,”137 sometimes also called cultural sensitivity or cultural humility |

| Effort-reward imbalance | A model developed “to identify health-adverse effects of stressful psychosocial work and employment conditions” that “posits exposure to recurrent experience of failed reciprocity at work ‘high cost/low gain’ increases the risk of incident stress-related disorders”138 |

| Explicit bias | Negative or positive attitudes that include “thoughts and feelings that people deliberately think about and can consciously report about”139 |

| Gender discrimination | Discrimination based on a person's gender103 |

| Gender harassment | The most prevalent type of sexual harassment and constitutes “a broad range of verbal and nonverbal behaviors not aimed at sexual cooperation but that convey insulting, hostile, and degrading attitudes about members of one gender,” including sexist hostility and crude harassment103 |

| Implicit bias | “Thoughts and feelings that often exist outside of conscious awareness, and thus are difficult to consciously acknowledge and control”139 |

| Intersectionality | “The acknowledgment that within groups of people with a common identity, whether it be gender, sexuality, religion, race, or one of the many other defining aspects of identity, there exist intragroup differences and that individuals may share and experience multiple identities simultaneously”140 |

| LGBTQ+ | Sexual and gender minority groups |

| Work-life balance | The “comfortable state of equilibrium achieved between an employee's primary priorities of their employment and their private lifestyle,” including time for family, personal relationships, hobbies, and potential responsibilities as a parent and/or caregiver141 |

| People with disabilities | Individuals living with “any condition of the body or mind (impairment) that makes it more difficult for the person with the condition to do certain activities (activity limitation) and interact with the world around them (participation restrictions),” such as impairments in hearing, vision, cognition, mobility, social relationships, communication, and/or self-care142 |

| Sexual harassment | “Unwelcome sexual advances, requests for sexual favors, and other verbal or physical conduct of a sexual nature constitute sexual harassment when this conduct explicitly or implicitly affects an individual's employment, unreasonably interferes with an individual's work performance, or creates an intimidating, hostile, or offensive work environment”103,143 |

| Technical standards | “A statement by a medical school of the (1) essential academic and nonacademic abilities, attributes, and characteristics in the areas of intellectual conceptual, integrative, and quantitative abilities; (2) observational skills; (3) physical abilities; (4) motor functioning; (5) emotional stability; (6) behavioral and social skills; and (7) ethics and professionalism that a medical school applicant or enrolled medical student must possess or be able to acquire, with or without reasonable accommodation, in order to be admitted to, be retained in, and graduate from that school's medical educational program”144 |

| Triple aim | A framework developed by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement that describes an approach to optimizing health system performance through simultaneous pursuit of improvement in patients' experience of care (including quality and satisfaction), population health, and reduction in the per capita cost of health care145 |

| URM | Underrepresented in medicine; defined by the AAMC as “those racial and ethnic populations that are underrepresented in the medical profession relative to their numbers in the general population”25 and was used before 2003 as the acronym for underrepresented minorities, “which consisted of Blacks, Mexican-Americans, Native Americans (i.e., American Indians, Alaska Natives, and Native Hawaiians), and mainland Puerto Ricans”25 |

The Role of Underrepresented Physicians in Patient Care

According to a 2018 report from the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) regarding accessibility and inclusion, “When health care providers have life experience that more closely matches the experiences of their patients, patients tend to be more satisfied with their care and to adhere to medical advice. This effect has been seen in studies addressing racial, ethnic, and sexual minority communities when the demographics of health care providers reflect those of underserved populations.”4 In addition, diversity has been shown to be good for business, including contributions to improved financial returns, income growth, group thinking, objectivity, and innovation.14,15

Women physicians

In 2017, women accounted for 35.2% (313,808 of 891,770) of the active physician workforce.16 The greatest numbers of women (>20,000) were found in family medicine/general practice (45,342), internal medicine (43,770), pediatrics (36,945), and obstetrics and gynecology (23,740). However, the proportion of women among physicians varies dramatically by specialty. Of 44 specialties, a far greater percentage of women than men practice pediatrics (63.3%) and obstetrics and gynecology (57.0%) than orthopedic surgery (5.3%).

Women have been credited with many advancements in the delivery of medical care, particularly in the areas of women's health.17 Moreover, women physicians are more likely to care for women18 and for patients with complex psychosocial issues, and provide more preventive care and counseling19 regardless of the sex of the patient.20 Greenwood et al. found that female patients were two to three times more likely to survive a heart attack—the leading cause of death among women—if their emergency room physician was a woman.21,22 A recent study of 1.5 million Medicare patients also found hospital mortality and readmission rates were lower for patients treated by women hospitalists than those treated by men,23 and women have been found to be less likely to be sued for malpractice.24

Physicians from racial and ethnic minority groups

Since 2004, the AAMC has referred to physicians from some racial and ethnic minority groups as being underrepresented in medicine (URM). While this flexible definition allows for adjustment due to changing physician workforce demographics, populations generally included in this group are “Blacks, Mexican-Americans, Native Americans (i.e., American Indians, Alaska Natives, and Native Hawaiians), and mainland Puerto Ricans.”25

Although assessing access to care, quality of the services delivered, patient outcomes, and patient satisfaction with care are highly complex; minority patients are more likely to choose a URM physician and are more satisfied with their care when it is provided by a URM physician.2,26,27 Moreover, URM physicians are more likely to practice primary care28 and to care for minority and vulnerable patients, including those from communities with lower socioeconomic status.2,29–33 In one study, URM physicians were noted as caring for “53.5% of minority and 70.4% of non-English-speaking patients,” and were more likely to have patients on Medicaid.34

Although 18% and 13% of the U.S. population identify as Hispanic and African American, respectively, as of 2014, the AAMC reported that only 4% of physicians come from these groups.28 Furthermore, despite calls by the AAMC in 2006 to increase both the number of medical schools and the enrollment of medical students, the percentages of matriculants from minority groups in 2015 remained low: Black or African American at 6.5%; Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish origin at 6.4%, and American Indian at 0.3%.3 The underrepresentation of physicians from these groups is concerning, especially because the Hispanic population is expected to increase by 26% by 2030, followed closely by the non-Hispanic others (19%), blacks (11%), and whites (9%).1 Moreover, improved access to medical insurance will increase demand for all physicians, including URM physicians.1

Physicians from sexual and gender minority groups

Historically, sexual and gender minority (LGBTQ+) health care professionals played a crucial role in the management of specific health crises such as the HIV/AIDS epidemic, including advocating for and delivering care to individuals affected by HIV.35 In 2014, the AAMC released guidelines for medical schools aimed at improving cultural competency in the care of LGBTQ+ patients.36–38 However, health care inequities persist and result in poorer health care outcomes than in the general population, including increased risk for depression, anxiety, HIV/AIDS, breast cancer, anal cancer, myocardial infarction, diabetes, and negative impacts from long-term hormone therapy.39

Although a recent study revealed that 7.7% of 14,254 matriculated U.S. medical students voluntarily identified as LGBTQ+,40 and percentages may be higher due the voluntary nature of disclosure,41 information regarding how many physicians self-identify as LGBTQ+ is sparse. Given projected physician workforce shortages, the need for a more diverse workforce, and the increasing number of American patients self-identifying as LGBTQ+, there is a need for more LGBTQ+-competent physicians.38,42,43

Physicians with disabilities

It is estimated that people with disabilities—including impairments affecting hearing, vision, cognition, mobility, self-care, and/or independent living—represent 20–25% of both the U.S. and global adult population.44 Despite a growing prevalence of disability, persons with disability represent an underserved and vulnerable patient population due to lack of physical access, low provider awareness, attitudinal barriers, and poor communication, and experience poorer health outcomes as a result.45–50

In 2012, it was reported that students with mobility and sensory impairments represented less than 1% of matriculated medical students.51 A more recent study indicated that less than 3% of currently matriculated medical students reported having a disability.52 However, this cohort also represented an expanded population in which students with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), learning disabilities, and psychological disabilities were most represented, followed by those with a chronic health issue, other functional impairment, visual impairment, mobility disability, and hearing impairment.52

Although a 2005 report noted that between 2% and 10% of physicians reported a disability,53 documented prevalence thereafter could not be located. Historically, research describing the prevalence of disability among medical trainees and practicing professionals has been limited by incomplete data, underreporting, and variable response rates among institutions, and recent analyses suggest that survey methodology may underestimate actual prevalence.52,54

Physicians with intersectional identities

Physicians with intersectional identities are those belonging simultaneously to more than one minority or underrepresented group (e.g., a Hispanic woman or a black gay man). In 2014, the AAMC reported that among younger Asian, black, African American, Hispanic, and Latino physicians, women represented a greater proportion of the workforce (52%) than men (48%).28 Although it may be reasonable to assume that physicians with intersectional identities serve multiple groups of patients either with singular or similar intersectional backgrounds and were likely included in studies of single underrepresented groups (e.g., women physicians), we found no report documenting studies of physicians with specific intersectional identities.

Physicians from Underrepresented Groups and Risk for Leaving Medicine

Physician burnout is a public health crisis and the problem is growing.55–59 “Not only does the individual suffer decreased self-esteem and a sense of failure, but his or her ability to provide care can be diminished, as can the ability to work with staff and colleagues. Absenteeism, lower productivity, and higher turnover, with subsequent disruptions in patient care continuity and patient disenrollment, can occur.”19 Burnout has been associated with increased risk to patient safety, poorer quality of care, and dissatisfaction with care.60 Physician burnout is also associated with a desire to decrease clinical hours or leave clinical practice altogether,61–63 and may exacerbate workforce shortages that ultimately impact patient care.62

Burnout is commonly defined as a triad of symptoms that occur as a result of chronic workplace stress: emotional exhaustion, depersonalization (e.g., distancing oneself from the demands of patient care by perceiving patients as impersonal objects), and low sense of personal accomplishment.64 The factors that contribute to physician burnout are complex and vary among those affected. Physician well-being may be affected by work-life imbalance, effort-reward imbalance, lack of autonomy, discrimination, poor mentorship, lack of workplace social support, isolation, work flow related to electronic health records, time pressure, and chaotic work environments.63,65

Physician burnout may be associated with an increased risk of suicidality,65 and it is estimated that approximately one physician dies by suicide each day.66 Men physicians are 1.41 times more likely and women physicians are 2.27 times more likely to die by suicide compared to nonphysicians.67 Moreover, women physicians are more than two times more likely to report thoughts of suicide than men physicians.68 In medical students, one study found that symptoms of burnout seemed to be associated with future suicidal ideation, while suicidal ideation decreased upon recovery from burnout.56

Burnout in women physicians

In 2017, the percentage of women physicians in active practice was reported at 35.2%,16 and the percentage of women among medical school matriculants passed the 50% mark for the first time.69 Recently, it has been suggested that the rising percentage of women physicians may have a negative impact on the availability of primary health care services because they work fewer hours, spend longer with patients, and see fewer patients per day.70 At the same time, women physicians have had better patient outcomes than men.21–23,71 However, women experience burnout at higher rates than men.72,73 Indeed, a recent study revealed that 42% of more than 15,000 physicians across 29 specialties reported symptoms of burnout, with more women physicians (48%) reporting burnout than men (38%).72 Among primary care physicians, women reported burnout nearly twice as much as men.63

Importantly, burnout may affect men and women differently. While men report more symptoms of depersonalization, women are more likely to report emotional exhaustion.61,74,75 Some studies show that women report similar levels of overall career satisfaction compared to men,19,76 but they may be less satisfied with specific aspects of their careers, including time for relationships at work and at home as well as career advancement opportunities, recognition, and salary.63,76

Inequities in work-life balance appear to be an important factor in women physicians' burnout. Patients expect women physicians to have a caring communication style and that may contribute to higher patient satisfaction,77 but also creates a heavier burden. Because women spend more time with their patients on average,19,78 they would likely need to work more hours per day to see the same number of patients as men physicians or bear negative impacts on compensation. One study reported every 5 h worked per week over 40 h increased the odds of burnout by 12–15%.79 Moreover, increasing work hours appears to correlate with a higher incidence of work-family/home conflict and lower overall job satisfaction.80–82

Women physicians also continue to spend disproportionately more time—8.5 h per week more—on child and elder care as well as housekeeping duties than their spouses or domestic partners,83 which may further contribute to higher levels of emotional exhaustion and burnout.83–85 This may explain why women physicians work fewer hours than men on average and are more likely to work part time.19,86,87

Effort-reward imbalance contributes to burnout in women physicians. A survey of more than 20,000 physicians across 29 specialties revealed that women primary care physicians had incomes 18% lower than men—up from 16% in 2017—and the gap increased to 36% for women specialists.86 The pay gap persists for women physicians even after adjustment for number of hours worked, type of work, and specialty.88 In academic medicine, the same is true even after adjusting for factors, including age; race/ethnicity; experience; specialty; department; faculty rank; research, teaching, administrative, or clinical focus; and marital or parental status.89,90 As a correlate to compensation, women with no debt had similar rates of high emotional exhaustion to men (40.5% vs. 38.4%); however, when debt levels exceeded $200,000, women reported much higher rates of high emotional exhaustion than men (60.0% vs. 49.8%).91

Women are also not equitably promoted. Despite representing more than one-third (35.2%) of the physician workforce,16 less than 25% of full professors and less than 18% of department chairs or deans are women.92 Women physicians do not equitably receive recognition awards,93–96 and there are troubling disparities in speaking,94,95 publishing,97,98 and leadership opportunities.99,100 Organizational barriers101 and implicit bias94,102 are often cited as major contributing factors supporting ongoing disparities for women in medicine.

Gender-based workplace discrimination and sexual harassment are also a persistent issue for women physicians,103 and gender discrimination is a predictive factor for burnout. According to a 2018 report from the National Academies of Science, Engineering and Medicine (NASEM), 40–50% of female medical students experience sexual harassment from academic faculty or staff.103 The report noted, “When women experience sexual harassment in the workplace, the professional outcomes include declines in job satisfaction; withdrawal from their organization (i.e., distancing themselves from the work either physically or mentally without actually quitting, having thoughts or intentions of leaving their job, and actually leaving their job); declines in organizational commitment (i.e., feeling disillusioned or angry with the organization); increases in job stress; and declines in productivity or performance.”103

A recent study in academic faculty found that 70% of women reported perceived gender bias and 30% reported sexual harassment during their careers, compared with 22% and 4% of men, respectively.104 With respect to medical specialty, rates of discrimination and sexual harassment experienced by women physicians were three times higher in cardiology (69% vs. 22%) and five times higher in radiology (25% vs. 5%) when compared with their male counterparts.105,106 A survey study of a large group of women physician mothers participating in an online community group found that almost 80% reported gender discrimination, maternal discrimination, or both.79

Gender discrimination often has been reported in studies with regard to women not being considered during administrative decision-making, with results suggesting that a lack of perceived workplace control and autonomy contribute significantly to career dissatisfaction and burnout in women physicians.19 Other reports have detailed more subtle and likely unintentional (implicit),102 yet pervasive and detrimental, discrimination, including microaggressions, microinequities, and bias (likely implicit/unconscious) that affect speaker introductions,107 letters of recommendation,108,109 evaluations,110 hiring decisions,111 and reviews.112

Burnout in URM physicians

Several studies provide insight into the effect of burnout on URM physicians.113–115 Hispanic doctors have reported higher career satisfaction and lower perceived stress than their white peers, while African American doctors reported similar levels of satisfaction and perceived stress.116 It has been suggested that some URM physicians may be more resilient due to educational, professional, and cultural challenges faced during their training113,117 and/or that URM physicians experience a “greater sense of community need and involvement” in their practice among lower socioeconomic status communities with vulnerable patients.33

Interestingly, a recent study of workforce longevity in Mississippi revealed that physicians from minority groups or those who practice in rural and shortage areas were among those with the longest careers.118 However, minority students have “cited racial discrimination, racial prejudice, feelings of isolation, and different cultural expectations” as negatively impacting their medical school experience.113 Further study is needed to determine how factors contributing to burnout may differ between URM and nonminority physicians, and more study is needed to identify URM physicians at risk for burnout.

There is some evidence that minority patients may prefer racially concordant physicians.119,120 A study of African-American patients and physicians found that racially concordant visits were longer and more satisfying to patients,26 and recently, African-American men were found to be more likely to participate in preventative services after being seen by a black physician.121,122 However, studies have shown that URM physicians may see a greater proportion of individuals with medical and psychosocial complexity and confront more environmental and structural challenges, while trying to provide high-quality care.123 Thus, URM physicians in certain clinical settings may experience a more challenging work environment with less physician autonomy and lower overall job satisfaction.123

Notably, these factors may contribute to physician burnout, reducing the number of hours worked or attrition from the workforce entirely.61–63 Importantly, because URM physicians are more likely to locate or remain in geographical areas with physician shortages and work with vulnerable patient populations,124 loss of URM physicians is likely to disproportionately affect minority/vulnerable patients, further increasing health care disparities.

Similar to women, URM physicians are underrepresented in leadership positions in medicine, likely also affecting income. While 26% of white faculty members held the rank of professor, 19% and 17% of Hispanic and African American physicians reached that same rank, respectively.28 Wage gaps have been reported for URM physicians,86,125 further impacting URM physicians who disproportionately come from low-income families, who lack generational wealth/physician legacy, and/or who have higher educational debt.126,127 As URM physicians have been shown to accumulate more debt and yet receive less compensation, they are likely paying a higher proportion of their income toward debt reduction.126 Concern exists whether financial factors may be contributing to burnout126,127 and deterring students from minority groups, from even entering the field of medicine.7

Burnout in LGBTQ+ physicians

LGBTQ+ physicians have reported being harassed by heterosexual colleagues, denied referrals, and ostracized.43 They are often witness to discriminatory behavior toward other LGBTQ+ individuals—patients, partners, and coworkers.43 More than 30% of patients indicated they would switch providers if they found out their physician was gay or the clinic/practice employed openly LGBTQ+ providers.128 In the one burnout-related study identified, LBGTQ+ students were 2.62 times more likely than heterosexual students to report burnout with depression, and academic, personal, and family stressors were strongly linked to symptoms.129 In another study, not directly focused on burnout, LGBTQ+ students were found to be at greater risk than heterosexual peers for factors that are often linked to burnout such as depression, anxiety, low perceived self-health, harassment, and isolation.130

Burnout in physicians with disabilities and intersectional identities

Unfortunately, we were unable to find any study specifically aimed at examining burnout in physicians with disabilities or with intersectional identities, making these important areas for future research. We postulate that physicians with disabilities or other intersectional identity, likely racial/ethnic, were included in studies of burnout in women. However, because intersectional identities were not stipulated in the studies, conclusions regarding burnout in physicians with intersectional identities could not be addressed.

Supporting Physicians from Underrepresented Groups in the Workforce

The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) recently updated their common program requirements for residency and fellowship programs. Beginning July 2019, “The program's annual evaluation must include an assessment of the program's efforts to recruit and retain a diverse workforce.”131,132 The training and support of physicians from underrepresented groups, however, have a complicated history.

Traditionally, the justification for allowances, special programs, or accommodations was, and often still is, based on the presumption that, once trained, these individuals will care for concordant, underserved, or vulnerable patient populations and therefore help to close gaps in health care service disparities—improving the overall health of the nation.34,133 Indeed, we found the literature ripe with studies documenting the benefits of patient-physician concordance,26,134 often concluding with statements such as, “increasing ethnic diversity among physicians may be the most direct strategy to improve health care experiences for members of ethnic minority groups.”26 Kelly-Blake et al. challenged this “message repetition” and explained that this type of thinking may inadvertently limit the full scope of physicians' practices as well as pursuit of research and leadership opportunities.135

Physicians from underrepresented groups have been disproportionately involved in the care of minority, underserved, and vulnerable patients. Moreover, workforce disparities contribute to burnout and the likelihood of physicians from underrepresented groups reducing hours or leaving medicine. Thus, we need to consider how we can better support them so that they may help address disparities in the care of minority, underserved, or vulnerable patient populations.

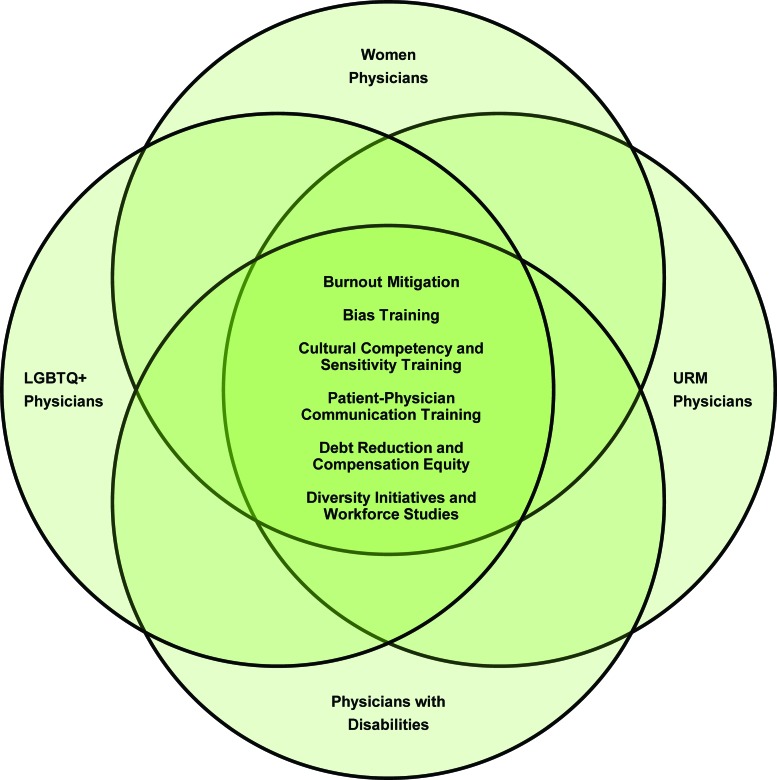

Solutions proposed by researchers and health care leaders to address issues identified in earlier sections are listed in Table 3. Notably, it is possible, although not proven, that some of the proposed solutions might be applicable to more than one of the underrepresented physician groups (Fig. 2), meaning that some single interventions may be capable of impacting multiple target groups, particularly those with intersectional identities.

Table 3.

Proposed Supports for Underrepresented Physicians

| Group | Objective | Targeted interventions proposed |

|---|---|---|

| All underrepresented physicians | Burnout mitigation Reduce stress Reduce permanent, temporary, and full-time withdrawals from medical practice Remove burnout as disincentive to medical career and/or specialty choice |

Well-being programs146 Create and appoint chief wellness officers who implement strategies aimed at the practice environment, teamwork and community building, leadership engagement, compassion for self and colleagues, and support for physicians experiencing distress147 Studies aimed at better understanding the variation in burnout and career regret across specialties57 |

| Bias training Improve communication Improve health outcomes Improve patient satisfaction Remove bias as a disincentive to medical career and/or specialty choice |

Education regarding how explicit (conscious) or implicit (unconscious) bias as well as the continuum from microinequities to macroinequities or aggressions can impact both professional interactions and patient care26,148,149 Completion of the Black-White Implicit Association Test during training to increase awareness of personal implicit bias150 Reduction or avoidance of negative comments from higher ranking physicians or negative interactions with patients150 Use of equitable language during introductions,107 blinded grant applications,112 standardized letters of recommendation,151 and conscious editing to remove negative or stereotypic language from letters of recommendation109 Increased exposure to diversity in educational and workplace settings48,150 Education and competencies for physicians-in-training with respect to meeting the needs of LGBTQ+ and other sexual and gender minority groups and effective incorporation of this information into the medical curriculum and clinical experience152,153 Creation of an affirming climate and improved accessibility to accommodations for students with disabilities4 |

|

| Cultural competency and sensitivity training Improve communication Improve patient access to care Accelerate Triple Aim154 Remove cultural differences as a disincentive to medical career and/or specialty choice Improve health outcomes |

Enactment and/or recommendation of national mandates and guidelines to improve workforce diversity and require cultural competency training155–162 Frame cultural competency training in terms of developing understanding of both the patient's and the physician's own cultural backgrounds and unconscious biases163 Acknowledge cultural competency as a life-long process, not an end-point, analogous to developing cultural sensitivity or cultural humility163,164 Advocate for collaborative relationships that value differing points of view in an effort to improve outcomes164 Tailor interactions to patient social, cultural, and communication preferences and needs156,158 Increase access to high-quality care services for the medically underserved165 Assess institutional readiness to address patient communication and environmental needs158 Strengthen the medical research agenda by improving diversity among both researchers and study participants165 Expand the pool of medically trained executives ready for health care system and governmental leadership roles165 |

|

| Patient-physician communication training Improve exchange of information Improve health outcomes Maintain or reduce appointment length Improve scheduling control Improve patient satisfaction Improve reimbursement outcomes |

Use patient-centered, conversational communication style consisting of more individualized, reciprocal and supportive responses and notetaking122,166,167 Identify patient's preferred language, communication needs, and assistive devices158 Improve awareness of patient affective cues166,168 Use patient decision aids and navigation169 Encourage use and participation of patient companions170 |

|

| Debt reduction and compensation equity Remove debt as a disincentive to medical career and/or specialty choice, and/or practice location Remove compensation inequity as a disincentive to medical career and/or specialty choice, and/or practice location |

Free or reduced medical school tuition171–173 Loan repayment, repayment delays, or loan forgiveness174,175 School-sponsored financial planning courses and/or access to personal finance experts175 State-sponsored financial incentive programs to attract qualified professionals174 Transparency in and public reporting of administrative salary information89 Accountability and initiatives to combat inequity across specialties and institutions89,176–178 Transparency in defining criteria for compensation179 Base pay structures on objective criteria179 Mitigate implicit bias in compensation decisions, including those regarding salary and bonuses179 |

|

| Diversity initiatives and workforce studies Improve patient access to care Accelerate Triple Aim154 |

Enhancement of diversity standards in medical and other professional training schools131,132,174 Establishment of workforce centers or clearinghouses to monitor data on the supply and demand for specific providers174 Evaluate the effectiveness of educational and workforce strategies174 |

|

| Women physicians | Sexual harassment | Develop methodical approaches surveying and combating sexual harassment180 Within institutions and organizations, evaluate and address (1) perceived tolerance for sexual harassment, (2) male-dominated workforce, (3) hierarchal power structures, (4) symbolic compliance, and (5) uninformed leadership103 Create diverse and respectful environments, improve transparency and accountability, diffuse power, support the targeted individual, and promote strong and diverse leadership103 |

| Gender discrimination | Adoption of systematic guidelines to end gender discrimination and improve the advancement of women in medicine94,181 Support rising women physicians through sponsorship,182 equitable funding (grant and award),183 and equitable collaboration and representation among authors,97,98 award recipients,93,94,183 faculty, editorial boards,184 committee members,100 and presidents of medical specialty societies99 Improve parental support, including but not limited to “longer paid maternity leave, backup child care, lactation support, and increased schedule flexibility”79 Improve support for physicians as family caregivers19 Improve control over patient-related decision-making, including but not limited to selection of referral physicians and determination of hospital length of stay19 Improve control or influence over work environment such as space and facilities, clinic/office schedule, patient load, and patient characteristics19 |

|

| URM physicians | Access to medical education | Increase public support for historically black medical schools133 Increase recruitment of URM physicians through holistic review of applications, conditional acceptance programs, outreach, scholarships, and branch campus locations185,186 Increase funding for k-12 education135 |

| Support for and advancement in medical ranks | Recruitment of minority physician faculty9,135 Medical specialty society support through education, pipeline programs, clinical care programs, position statements, advocacy, data management, research, and mentorship187 |

|

| LGBTQ+ physicians | Recruitment and workplace culture | Applications allowing declaration of LGBTQ+ status as well as consideration of that status as strengthening applications to medical school188 Diversity hiring policies188 LGBTQ+ advocates campus-wide, LGBTQ+-friendly training, and LGBTQ+-friendly workplaces (e.g., gender inclusive restrooms)188 Partner benefits equivalent to those available to a traditional spouse (e.g., sick leave, maternity leave, and insurance coverage)188 Healthy coping strategies, social networks, professional networks, and advocacy groups189 |

| Patient comfort, communication, and outcomes | LGBTQ+-inclusive evidence-based educational materials188,190 LGBTQ+-inclusive forms and decision-making tools188,190 |

|

| Physicians with disabilities | Recruitment and workforce culture | Include disability in discussions of diversity4,191,192 Increase recruitment193 Remove pressure on students and physicians to disclose the full nature of their disability4 Improve and standardize medical school technical standards194 addressing unclear, inconsistent, and lengthy policies and processes4 Define responsibility for accommodations4,194 Provide access to appropriate accommodations, personal and professional networks, peer support, and mentorship4 Expand study of barriers and accommodations supportive of physicians194–196 |

| Patient comfort, communication, and outcomes | Improve access, provider awareness, and communication, and address attitudinal barriers45–49,195,197–199 |

FIG. 2.

Intersection of support for physicians from underrepresented groups. Color images are available online.

Limitations

Although the list of keywords used to search for studies related to the role of physicians from underrepresented groups in medicine seemed inclusive, we found that these keywords were not sufficient to identify all of the studies relevant to this report. We postulate that this discrepancy is due, in part, to inconsistent use of keywords to tag reports applicable to the groups of physicians and patients included in this study. Nevertheless, some sections of this report are more expansive than others because some groups of underrepresented physicians have been studied more (e.g., women physicians) than others (e.g., URM, LGBTQ+, and physicians with disabilities). Moreover, it is also likely that some of the studies included could have addressed intersectionality, but did not. For example, studies of women physicians likely included women physicians who were also URM.

Conclusion

This report describes an evolving literature that demonstrates the potential impacts of workforce disparities on physicians from underrepresented groups and, in turn, patient care. Despite historical and contemporary challenges, physicians from underrepresented groups—including women, URM, and LGBTQ+, and those with disabilities—are crucial to health care access and quality for the broader U.S. population. As diversity efforts improve, expand, and impact the state of medicine in the U.S., it will be imperative for policymakers, stakeholders, and researchers to consider the unique experiences of physicians from these underrepresented groups when working together to address potential workforce shortages and physician well-being.

Because reasons for inequity may differ between underrepresented groups of physicians, we call on every institution and organization to examine equity in a manner consistent with a six-step data-driven and evidence-based procedure proposed for women in medical specialty societies, which involves identification of inequities, investigation of root causes, implementation of and measurement of outcomes associated with compensatory strategies, and reporting of results to all stakeholders.94,100

Abbreviations Used

- AAMC

Association of American Medical Colleges

- URM

underrepresented in medicine

Author Disclosure Statement

J.K.S. discloses that she received a grant from the Arnold P. Gold Foundation to support this work. As an academic physician, she has published books and receives royalties from book publishers, gives professional talks such as Grand Rounds and medical conference plenary lectures, and receives honoraria from conference organizers. She has grant funding from the Binational Scientific Foundation (culinary telemedicine research). She has personally funded the Be Ethical Campaign and proceeds from the campaign support disparities research. C.S. has Grant funding from National Institutes of Health, Wings for Life, Craig H. Neilsen Foundation. A.T. receives financial support for research on health outcomes from American Style Football, from a grant from the Football Players Health Study at Harvard University, which is funded by the NFL Players Association (NFLPA). He also has received funding from the American Medical Society for Sports Medicine. C.A.B. has grant funding from the International Olympic Committee (characterization of shoulder injuries in Para athletes) and is partially supported by the Spaulding New England Regional Spinal Cord Injury Center (Agency for Community Living/NIDLRR). R.Z. evaluates patients in the MGH Brain and Body-TRUST Program, which is funded by the NFL Players Association. He was partially supported by NIDILRR: 90DP0039-03-00, 90SI5007-02-04, and 90 D P0060; USAMRC-W81XWH-112-0210; and NIH: 4U01NS086090-04, 5R24HD082302-02, and 5U01NS091951-03, and by a grant from the Football Players Health Study at Harvard University, which is funded by the NFL Players Association (NFLPA). He also evaluates patients for the MGH brain and Body TRUST center sponsored, in part, by the NFLPA and serves on the Mackey White health committee. This project was made possible with a Mapping the Landscape, Journeying Together grant from the Arnold P. Gold Foundation Research Institute. C.S. received financial consulting fees from Acumen, LLC, for work related to health care payment policy and honoraria from Becker's Health care and Oakstone Publishing. C.A.B. discloses that as an academic physician, she gives professional talks such as Grand Rounds and medical conference plenary lectures, and receives honoraria from conference organizers. R.A.K. is employed by National Patient Advocate Foundation and as a consulting faculty advisor to the Center to Advance Palliative Care. R.Z. receives royalties from (1) Oakstone for an educational CD-Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation a Comprehensive Review and (2) Demos publishing for serving as co-editor of the text Brain Injury Medicine. R.Z. serves on the Scientific Advisory Board of Oxeia Biopharma, Biodirection, ElMINDA, and Myomo. H.L.A. reports time for development and completion of this work was funded by the Harvard Medical School Dupont-Warren Research Fellowship Award and the Harvard Medical School Livingston Research Award. No competing financial interests exist for the other authors.

Cite this article as: Silver JK, Bean AC, Slocum C, Poorman JA, Tenforde A, Blauwet CA, Kirch RA, Parekh R, Amonoo HL, Zafonte R, and Osterbur D (2019) Physician workforce disparities and patient care: a narrative review, Health Equity 3:1, 360–377, DOI: 10.1089/heq.2019.0040.

References

- 1. IHS Markit. The Complexities of Physician Supply and Demand: Projections from 2016 to 2030. Washington, DC: Association of American Medical Colleges, 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Institute of Medicine (US). Committee on institutional and policy-level strategies for increasing the diversity of the U.S. Healthcare Workforce. In: In the Nation's Compelling Interest: Ensuring Diversity in the Health-Care Workforce. Edited by Smedley BD, Stith Butler A, Bristow LR. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US), 2004. DOI: 10.17226/10885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Diversity in Medical Education: AAMC Facts & Figures 2016. Association of American Medical Colleges. Available at www.aamcdiversityfactsandfigures2016.org/index.html Accessed January16, 2019

- 4. Meeks LM, Jain NR. Accessibility, Inclusion, and Action in Medical Education: Lived Experiences of Learners and Physicians with Disabilities. Washington, DC: Association of American Medical Colleges, 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 5. Laurencin CT, Murray M. An American crisis: the lack of black men in medicine. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2017;4:317–321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. At a Glance: Black and African American Physicians in the Workforce. AAMC News, 2017. Available at https://news.aamc.org/diversity/article/black-history-month-facts-and-figures Accessed February28, 2019

- 7. You Can Afford Medical School. Association of American Medical Colleges, 2019. Available at https://students-residents.aamc.org/choosing-medical-career/article/you-can-afford-medical-school Accessed February7, 2019

- 8. GME Funding and Its Role in Addressing the Physician Shortage. AAMC News. Available at https://news.aamc.org/for-the-media/article/gme-funding-doctor-shortage Accessed February27, 2019

- 9. Yu PT, Parsa PV, Hassanein O, et al. . Minorities struggle to advance in academic medicine: a 12-y review of diversity at the highest levels of America's teaching institutions. J Surg Res. 2013;182:212–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pololi LH, Krupat E, Civian JT, et al. . Why are a quarter of faculty considering leaving academic medicine? A study of their perceptions of institutional culture and intentions to leave at 26 representative U.S. medical schools. Acad Med. 2012;87:859–869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Shanafelt TD, Hasan O, Dyrbye LN, et al. . Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance in physicians and the general US working population between 2011 and 2014. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90:1600–1613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lindeman S, Laara E, Hakko H, et al. . A systematic review on gender-specific suicide mortality in medical doctors. Br J Psychiatry. 1996;168:274–279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. The Sullivan Commission on Diversity in the Healthcare Workforce. Missing Persons: Minorities in the Health Professions. Alexandria, VA: The Sullivan Alliance to Transform the Health Professions, 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 14. Phillips KW. How diversity works. Sci Am. 2014;311:42–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Why Diverse Teams Are Smarter. Harv Bus Rev. Available at https://hbr.org/2016/11/why-diverse-teams-are-smarter Accessed February27, 2019

- 16. Association of American Medical Colleges. Table 1.3. Number and Percentage of Active Physicians by Sex and Specialty, 2017. Association of American Medical Colleges, 2017. Available at www.aamc.org/data/workforce/reports/492560/1-3-chart.html Accessed January4, 2019

- 17. Carnes M, Morrissey C, Geller SE. Women's health and women's leadership in academic medicine: hitting the same glass ceiling? J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2008;17:1453–1462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Guarín-Nieto E, Krugman SD. Gender disparity in women's health training at a family medicine residency program. Fam Med. 2010;42:100–104 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. McMurray JE, Linzer M, Konrad TR, et al. . The work lives of women physicians results from the physician work life study: the SGIM Career Satisfaction Study Group. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15:372–380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Henderson JT, Weisman CS. Physician gender effects on preventive screening and counseling: an analysis of male and female patients' health care experiences. Med Care. 2001;39:1281–1292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Greenwood BN, Carnahan S, Huang L. Patient-physician gender concordance and increased mortality among female heart attack patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2018;115:8569–8574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Lower Your Risk for the Number 1 Killer of Women. CDC Features, 2018. Available at www.cdc.gov/features/wearred/index.html Accessed January6, 2019

- 23. Tsugawa Y, Jena AB, Figueroa JF, et al. . Comparison of hospital mortality and readmission rates for Medicare patients treated by male vs female physicians. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:206–213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Unwin E, Woolf K, Wadlow C, et al. . Sex differences in medico-legal action against doctors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med. 2015;13:172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Underrepresented in Medicine Definition. Association of American Medical Colleges. Available at www.aamc.org/initiatives/urm Accessed February18, 2019

- 26. Cooper LA, Roter DL, Johnson RL, et al. . Patient-centered communication, ratings of care, and concordance of patient and physician race. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:907–915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Laveist TA, Nuru-Jeter A. Is doctor-patient race concordance associated with greater satisfaction with care? J Health Soc Behav. 2002;43:296–306 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Diversity in the Physician Workforce: Facts and Figures 2014. Association of American Medical Colleges, 2014. Available at www.aamcdiversityfactsandfigures.org Accessed November4, 2018

- 29. Bach PB, Pham HH, Schrag D, et al. . Primary care physicians who treat blacks and whites. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:575–584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Brotherton SE, Stoddard JJ, Tang SS. Minority and nonminority pediatricians' care of minority and poor children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2000;154:912–917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Xu G, Fields SK, Laine C, et al. . The relationship between the race/ethnicity of generalist physicians and their care for underserved populations. Am J Public Health. 1997;87:817–822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Komaromy M, Grumbach K, Drake M, et al. . The role of black and Hispanic physicians in providing health care for underserved populations. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:1305–1310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gartland JJ, Hojat M, Christian EB, et al. . African American and white physicians: a comparison of satisfaction with medical education, professional careers, and research activities. Teach Learn Med. 2003;15:106–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Marrast LM, Zallman L, Woolhandler S, et al. . Minority physicians' role in the care of underserved patients: diversifying the physician workforce may be key in addressing health disparities. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:289–291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Mayer KH, Bradford JB, Makadon HJ, et al. . Sexual and gender minority health: what we know and what needs to be done. Am J Public Health. 2008;98:989–995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Association of American Medical Colleges. New Curricula Help Students Understand Health Needs of LGBT Patients. AAMC News. Available at https://news.aamc.org/diversity/article/bring-lgbt-patient-care-medical-schools Accessed January14, 2019

- 37. Association of American Medical Colleges. Meeting the Demand for Better Transgender Care. AAMC News. Available at: https://news.aamc.org/diversity/article/meeting-demand-better-transgender-health-care Accessed January14, 2019

- 38. Association of American Medical Colleges. Gay, Lesbian, and Bisexual Health Care: Access to Medical Care and Behavioral Health Care. AAMC Workforce Studies Data Snapshot, 2017. Available at www.aamc.org/download/481232/data/lgbdatabriefinfographic.pdf Accessed January13, 2019

- 39. National Institutes of Health Sexual and Gender Minority Research Coordinating Committee. NIH FY 2016–2020 strategic plan to advance research on the health and well-being of sexual and gender minorities. Available at https://dpcpsi.nih.gov/sites/default/files/sgmStrategicPlan.pdf Accessed January14, 2019

- 40. Matriculating Student Questionnaire: 2018 All School Summary Report. Association of American Medical Colleges, 2016. Available at www.aamc.org/download/494044/data/msq2018report.pdf Accessed January13, 2019

- 41. Lourie MA. Unlocking the closet door: recurrent identity disclosure experiences among LGBTQ students. Acad Med. 2018;93:522–523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Khalili J, Leung LB, Diamant AL. Finding the perfect doctor: identifying lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender-competent physicians. Am J Public Health. 2015;105:1114–1119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Eliason MJ, Dibble SL, Robertson PA. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) physicians' experiences in the workplace. J Homosex. 2011;58:1355–1371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Okoro CA, Hollis ND, Cyrus AC, et al. . Prevalence of disabilities and health care access by disability status and type among adults—United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:882–887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. DeLisa JA, Lindenthal JJ. Commentary: reflections on diversity and inclusion in medical education. Acad Med. 2012;87:1461–1463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Iezzoni LI. Eliminating health and health care disparities among the growing population of people with disabilities. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30:1947–1954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. National Council on Disability. The Current State of Health Care for People with Disabilities. National Council on Disability, 2009

- 48. Ouellette A. Patients to peers: barriers and opportunities for doctors with disabilities. Nev Law J. 2013;13:Article 3 [Google Scholar]

- 49. Crossley M. Disability cultural competence in the medical profession. St Louis U J Health Law Policy. 2015;9:89–110 [Google Scholar]

- 50. World Health Organization. World Report on Disability. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 51. Eickmeyer SM, Do KD, Kirschner KL, et al. . North American medical schools' experience with and approaches to the needs of students with physical and sensory disabilities. Acad Med. 2012;87:567–573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Meeks LM, Herzer KR. Prevalence of self-disclosed disability among medical students in US allopathic medical schools. JAMA. 2016;316:2271–2272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. DeLisa JA, Thomas P. Physicians with disabilities and the physician workforce: a need to reassess our policies. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;84:5–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Moutsiakis D, Polisoto T. Reassessing physical disability among graduating US medical students. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2010;89:923–930 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Lacy BE, Chan JL. Physician burnout: the hidden health care crisis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16:311–317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Dyrbye LN, Thomas MR, Massie FS, et al. . Burnout and suicidal ideation among U.S. medical students. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149:334–341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Dyrbye LN, Burke SE, Hardeman RR, et al. . Association of clinical specialty with symptoms of burnout and career choice regret among US resident physicians. JAMA. 2018;320:1114–1130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Rotenstein LS, Torre M, Ramos MA, et al. . Prevalence of burnout among physicians: a systematic review. JAMA. 2018;320:1131–1150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Wiederhold BK, Cipresso P, Pizzioli D, et al. . Intervention for physician burnout: a systematic review. Open Med (Wars). 2018;13:253–263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Panagioti M, Geraghty K, Johnson J, et al. . Association between physician burnout and patient safety, professionalism, and patient satisfaction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178:1317–1330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 61. Pantenburg B, Luppa M, König H-H, et al. . Burnout among young physicians and its association with physicians' wishes to leave: results of a survey in Saxony, Germany. J Occup Med Toxicol. 2016;11:2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Dyrbye LN, Varkey P, Boone SL, et al. . Physician satisfaction and burnout at different career stages. Mayo Clin Proc. 2013;88:1358–1367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Rabatin J, Williams E, Baier Manwell L, et al. . Predictors and outcomes of burnout in primary care physicians. J Prim Care Community Health. 2016;7:41–43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Maslach C, Schaufeli WB, Leiter MP. Job burnout. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001;52:397–422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Patel RS, Bachu R, Adikey A, et al. . Factors related to physician burnout and its consequences: a review. Behav Sci (Basel). 2018;8 DOI: 10.3390/bs8110098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Collier R. Physician suicide too often “brushed under the rug.” Can Med Assoc J. 2017;189:E1240–E1241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Schernhammer ES, Colditz GA. Suicide rates among physicians: a quantitative and gender assessment (meta-analysis). Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:2295–2302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Brooks E, Gendel MH, Early SR, et al. . When doctors struggle: current stressors and evaluation recommendations for physicians contemplating suicide. Arch Suicide Res. 2017;22:519–528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Association of American Medical Colleges. A Landmark for Women in Medicine. AAMC News, 2018. Available at https://news.aamc.org/medical-education/article/word-president-landmark-women-medicine Accessed January7, 2019

- 70. Hedden L, Barer ML, Cardiff K, et al. . The implications of the feminization of the primary care physician workforce on service supply: a systematic review. Hum Resour Health. 2014;12:32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Berthold HK, Gouni-Berthold I, Bestehorn KP, et al. . Physician gender is associated with the quality of type 2 diabetes care. J Intern Med. 2008;264:340–350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Peckham C. National Physician Burnout & Depression Report 2018. Medscape, 2018. Available at www.medscape.com/slideshow/2018-lifestyle-burnout-depression-6009235 Accessed November5, 2018

- 73. Dimou FM, Eckelbarger D, Riall TS. Surgeon burnout: a systematic review. J Am Coll Surg. 2016;222:1230–1239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Prins JT, Gazendam-Donofrio SM, Tubben BJ, et al. . Burnout in medical residents: a review. Med Educ. 2007;41:788–800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Purvanova RK, Muros JP. Gender differences in burnout: a meta-analysis. J Vocat Behav. 2010;77:168–185 [Google Scholar]

- 76. Rizvi R, Raymer L, Kunik M, et al. . Facets of career satisfaction for women physicians in the United States: a systematic review. Women Health. 2012;52:403–421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Schmid Mast M, Hall JA, Roter DL. Disentangling physician sex and physician communication style: their effects on patient satisfaction in a virtual medical visit. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;68:16–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Scholle SH, Gardner W, Harman J DJ, et al. . Physician gender and psychosocial care for children: attitudes, practice characteristics, identification, and treatment. Med Care. 2001;39:26–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Adesoye T, Mangurian C, Choo EK, et al. . Perceived discrimination experienced by physician mothers and desired workplace changes: a cross-sectional survey. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:1033–1036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Dyrbye LN, Freischlag J, Kaups KL, et al. . Work-home conflicts have a substantial impact on career decisions that affect the adequacy of the surgical workforce. Arch Surg. 2012;147:933–939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Fuss I, Nübling M, Hasselhorn H-M, et al. . Working conditions and work-family conflict in German hospital physicians: psychosocial and organisational predictors and consequences. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Zutshi M, Hammel J, Hull T. Colorectal surgeons: gender differences in perceptions of a career. J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;14:830–843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Jolly S, Griffith KA, DeCastro R, et al. . Gender differences in time spent on parenting and domestic responsibilities by high-achieving young physician-researchers. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160:344–353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Carr PL, Ash AS, Friedman RH, et al. . Relation of family responsibilities and gender to the productivity and career satisfaction of medical faculty. Ann Intern Med. 1998;129:532–538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Robinson GE. Stresses on women physicians: consequences and coping techniques. Depress Anxiety. 2003;17:180–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Kane L. Physician Compensation Report 2018. Medscape, 2018. Available at www.medscape.com/slideshow/2018-compensation-overview-6009667 Accessed November5, 2018

- 87. Ly DP, Seabury SA, Jena AB. Hours worked among US dual physician couples with children, 2000 to 2015. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:1524–1525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Apaydin EA, Chen PGC, Friedberg MW. Differences in physician income by gender in a multiregion survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33:1574–1581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Jena AB, Olenski AR, Blumenthal DM. Sex differences in physician salary in US public medical schools. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176:1294–1304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Freund KM, Raj A, Kaplan SE, et al. . Inequities in academic compensation by gender: a follow-up to the National Faculty Survey Cohort Study. Acad Med. 2016;91:1068–1073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. West CP, Shanafelt TD, Kolars JC. Quality of life, burnout, educational debt, and medical knowledge among internal medicine residents. JAMA. 2011;306:952–960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Faculty Roster. Association of American Medical Colleges, 2018. Available at www.aamc.org/data/facultyroster Accessed November4, 2018

- 93. Silver JK, Blauwet CA, Bhatnagar S, et al. . Women physicians are underrepresented in recognition awards from the Association of Academic Physiatrists. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2018;97:34–40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Silver JK, Slocum CS, Bank AM, et al. . Where are the women? The underrepresentation of women physicians among recognition award recipients from medical specialty societies. PM R. 2017;9:804–815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Silver JK, Bank AM, Slocum CS, et al. . Women physicians underrepresented in American Academy of Neurology recognition awards. Neurology. 2018;91:e603–e614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Silver JK, Bhatnagar S, Blauwet CA, et al. . Female physicians are underrepresented in recognition awards from the American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. PM R. 2017;9:976–984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Larson AR, Poorman JA, Silver JK. Representation of women among physician authors of perspective-type articles in high impact dermatology journals. JAMA Dermatol 2019. [Epub ahead of print]; DOI: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.5517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Silver JK, Poorman JA, Reilly JM, et al. . Assessment of women physicians among authors of perspective-type articles published in high-impact pediatric journals. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1:e180802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Silver JK, Ghalib R, Poorman JA, et al. . Analysis of gender equity in leadership of physician-focused medical specialty societies, 2008–2017. JAMA Intern Med. 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Silver JK, Cuccurullo SJ, Ambrose AF, et al. . Association of Academic Physiatrists women's task force report. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2018;97:680–690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Silver JK. #BeEthical—a call to healthcare leaders: Ending gender workforce disparities is an ethical imperative. 2018. Available at http://sheleadshealthcare.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Be_Ethical_Campaign_101418.pdf Accessed February23, 2019

- 102. Silver JK, Rowe M, Sinha MS, et al. . Micro-inequities in medicine. PM R. 2018;10:1106–1114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, Policy and Global Affairs, Committee on Women in Science, Engineering, and Medicine, Committee on the Impacts of Sexual Harassment in Academia. In: Sexual Harassment of Women: Climate, Culture, and Consequences in Academic Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Edited by Benya FF, Widnall SE, Johnson PA, eds. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US), 2018. DOI: 10.17226/24994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Jagsi R, Griffith KA, Jones R, et al. . Sexual harassment and discrimination experiences of academic medical faculty. JAMA. 2016;315:2120–2121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Poppas A, Cummings J, Dorbala S, et al. . Survey results: a decade of change in professional life in cardiology: a 2008 report of the ACC Women in Cardiology Council. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:2215–2226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Camargo A, Liu L, Yousem DM. Sexual harassment in radiology. J Am Coll Radiol. 2017;14:1094–1099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Files JA, Mayer AP, Ko MG, et al. . Speaker introductions at internal medicine grand rounds: forms of address reveal gender bias. J. Womens Health (Larchmt). 2017;26:413–419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Madera JM, Hebl MR, Martin RC. Gender and letters of recommendation for academia: agentic and communal differences. J Appl Psychol. 2009;94:1591–1599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Trix F, Psenka C. Exploring the color of glass: letters of recommendation for female and male medical faculty. Discourse Soc. 2003;14:191–220 [Google Scholar]

- 110. Choo EK. Damned if you do, damned if you don't: bias in evaluations of female resident physicians. J Grad Med Educ. 2017;9:586–587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Moss-Racusin CA, Dovidio JF, Brescoll VL, et al. . Science faculty's subtle gender biases favor male students. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:16474–16479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Guglielmi G. Gender bias goes away when grant reviewers focus on the science. Nature. 2018;554:14–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Dyrbye LN, Thomas MR, Eacker A, et al. . Race, ethnicity, and medical student well-being in the United States. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:2103–2109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Dyrbye LN, Thomas MR, Huschka MM, et al. . A multicenter study of burnout, depression, and quality of life in minority and nonminority US medical students. Mayo Clin Proc. 2006;81:1435–1442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Dyrbye LN, Power DV, Massie FS, et al. . Factors associated with resilience to and recovery from burnout: a prospective, multi-institutional study of US medical students. Med Educ. 2010;44:1016–1026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Glymour MM, Saha S, Bigby J, et al. . Physician race and ethnicity, professional satisfaction, and work-related stress: results from the Physician Worklife Study. J Natl Med Assoc. 2004;96:1283.–1289, 1294. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Maslach C. Burnout: The Cost of Caring. Cambridge, MA: Malor Books, 1982 [Google Scholar]

- 118. Boydstun J, Cossman JS. Career expectancy of physicians active in patient care: evidence from Mississippi. Rural Remote Health. 2016;16:3813. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Porter JR, Beuf AH. The effect of a racially consonant medical context on adjustment of African-American patients to physical disability. Med Anthropol. 1994;16:1–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Saha S, Taggart SH, Komaromy M, et al. . Do patients choose physicians of their own race? Health Aff. (Millwood). 2000;19:76–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Duff-Brown B. Black Men Could Be Healthier If Seen by Black Physicians, New Research Suggests. Standford Medicine SCOPE, 2018. Available at https://scopeblog.stanford.edu/2018/07/19/black-men-could-be-healthier-if-seen-by-black-physicians-new-research-suggests/?linkId=54594579 Accessed November6, 2018