Abstract

Podosomes are a singular category of integrin-mediated adhesions important in the processes of cell migration, matrix degradation and cancer cell invasion. Despite a wealth of biochemical studies, the effects of mechanical forces on podosome integrity and dynamics are poorly understood. Here, we show that podosomes are highly sensitive to two groups of physical factors. First, we describe the process of podosome disassembly induced by activation of myosin-IIA filament assembly. Next, we find that podosome integrity and dynamics depends upon membrane tension and can be experimentally perturbed by osmotic swelling and deoxycholate treatment. We have also found that podosomes can be disrupted in a reversible manner by single or cyclic radial stretching of the substratum. We show that disruption of podosomes induced by osmotic swelling is independent of myosin-II filaments. The inhibition of the membrane sculpting protein, dynamin-II, but not clathrin, resulted in activation of myosin-IIA filament formation and disruption of podosomes. The effect of dynamin-II inhibition on podosomes was, however, independent of myosin-II filaments. Moreover, formation of organized arrays of podosomes in response to microtopographic cues (the ridges with triangular profile) was not accompanied by reorganization of myosin-II filaments. Thus, mechanical elements such as myosin-II filaments and factors affecting membrane tension/sculpting independently modulate podosome formation and dynamics, underlying a versatile response of these adhesion structures to intracellular and extracellular cues.

This article is part of a discussion meeting issue ‘Forces in cancer: interdisciplinary approaches in tumour mechanobiology’.

Keywords: myosin-II filaments, membrane tension, integrin-based adhesions, cell stretching, structured-illumination microscopy

1. Introduction

Podosomes are a distinct type of integrin-mediated cell–matrix adhesion typically seen in cells of monocytic origin (dendritic cells [1,2], macrophages [3] and osteoclasts [4] but also found more recently in a variety of other cell types [5–8]). In early studies, podosomes were also found in some types of cancer cells (Src-transformed fibroblasts [9,10]). Thus, podosomes could be considered as a ubiquitous category of integrin-based matrix adhesion structures, whose participation in cancer cell invasion and metastasis is now well documented [11,12].

Analogous to another class of integrin-based adhesions, focal adhesions, podosomes are membrane specializations in which clusters of integrin family transmembrane receptors are connected to actin filaments. While both integrin receptors themselves and numerous proteins linking the cytoplasmic domains of these receptors with the actin cytoskeleton are similar in podosomes and focal adhesions, the organization of the actin core is different in these types of structures. Focal adhesions are peripheral termini of actin bundles known as stress fibres and the actin scaffold of focal adhesions also consists of bundles of parallel actin filaments [13–15]. Actin filaments of focal adhesions are associated via numerous links containing talin and vinculin, with clusters of integrins located immediately underneath the actin filament layer [16]. The major nucleators of actin filaments in focal adhesions are thought to be formins [15,17–20] even though the Arp2/3 complex plays an important regulatory role, especially at the early stage of focal adhesion formation [21,22]. By contrast, the actin core of podosomes is formed mainly via Arp2/3-driven branching actin polymerization, and the Arp2/3 complex along with its activators WASP/N-WASP are essential components of podosomes [23–25]. In addition, podosomes contain a number of other actin-interacting proteins missing in focal adhesions, such as cortactin [26], gelsolin [27], cofilin [28,29] and dynamin-II [30,31]. Unlike focal adhesions, the clusters of integrin receptors are located not underneath the actin core but at its periphery forming an approximately ring-shaped structure [32–34]. Formins seem to play a less important role in podosome formation than the Arp2/3 complex, though the radial filaments connecting the podosome core with proteins of the adhesive ring are postulated to be nucleated by formins [35,36].

The formation and dynamics of focal adhesions strongly depend on physical forces developed in the course of cell interactions with the extracellular matrix. Treatment of cells with diverse inhibitors interfering with myosin-II filament assembly or mechanochemical activity, as well as knockdown of myosin-IIA, results in disassembly of mature (but not nascent) focal adhesions [37–40]. Moreover, application of external mechanical forces to focal adhesions can promote their growth, while plating on soft or fluid substrates, which do not support development of traction forces by cells, is not favourable for focal adhesion formation [17,41,42]. Focal adhesion maturation from initial nascent adhesions, as well as their further growth, depend on myosin-IIA filament mechanochemical and cross-linking activity as well as on polymerization and bundling of actin filaments [19,43]. Centripetal traction forces required for focal adhesion growth emerge due to the coupling of centripetal actin flow to integrin clusters via a stick-slip clutch mechanism [44–46]. The formation of myosin-II filament superstructures (stacks) [47] may also play a role in organization of the actin bundles in the lamellum and focal adhesion maturation.

The formation and maintenance of podosomes depends on different mechanical requirements compared to focal adhesions. In particular, podosome formation can efficiently proceed in cells plated on fluid-supported lipid bilayer membrane, a substrate which does not permit development of traction forces exerted on integrin clusters [8,48]. Moreover, fibroblast-type cells, which normally form focal adhesions on stiff matrix, switch to forming podosomes after being plated onto fluid substrates [8]. Thus, podosomes appear to self-assemble by default under conditions of deprivation of traction forces, while focal adhesions critically depend on development of such forces.

In agreement with this premise, recent experimental evidence shows that myosin-II filaments play an inhibitory rather than stimulatory role in podosome formation. Activation of myosin-IIA filament formation by a number of pathways converging to the Rho/ROCK signalling axis [49–52] as well as depletion of the regulatory protein S100A4 [53] promote podosome disassembly. Proteins known as supervillin and LSP-1 (lymphocyte-specific protein-1) appear to control the disruptive effect of myosin-IIA on podosomes by regulating the recruitment of myosin-IIA to the podosome environment [49,50].

Last but not least, unlike focal adhesions, which are essentially planar structures, podosomes are known to be small uniform membrane protrusions. This protrusional activity of podosomes is especially evident when cells are attached to soft deformable substrata [8,54–56]. This means that the processes of membrane sculpting would play an important role in the formation and dynamics of podosomes. Indeed, several proteins known to be potent regulators of membrane sculpting, such as dynamin-II [30,31], and several BAR domain proteins [30,57–60] are localized to podosomes and often required for their formation. The effects of mechanical deformation of membrane and factors affecting membrane tension on podosome formation are, however, not much studied. Furthermore, the relationship between myosin-II-driven podosome remodelling and factors affecting membrane sculpting has not yet been investigated.

The aim of the present study was to explore the effects of different categories of external and internal mechanical forces applied to podosomes. We paid special attention to factors affecting membrane tension as well as processes of membrane sculpting. We show that the effects of factors affecting membrane tension and sculpting on podosomes are independent of the effects of myosin-IIA filaments. We also found that, unlike focal adhesions, podosomes are highly sensitive to substrate stretching and demonstrate unique dependence on substrate topography. Altogether, our results clearly show that podosome formation and dynamics are regulated by two groups of mechanical factors, one operating via myosin-IIA filaments and the other being membrane deformations. This sheds a new light on the unique role of podosome-type adhesions in cell migration and environmental sensing as well as in cancer invasion and metastasis.

2. Results

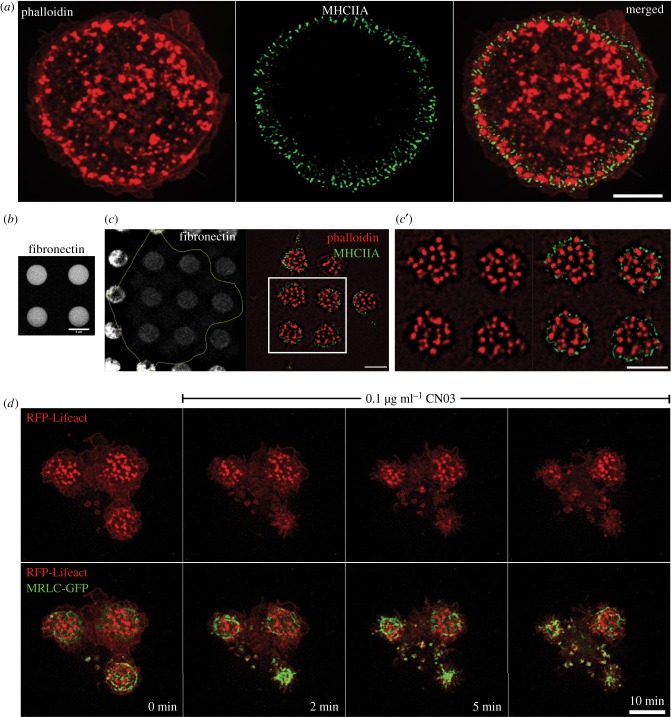

(a). Disruptive effect of myosin-II filament assembly on podosome integrity

The antagonism between myosin-II filaments overproduction and podosome formation was documented in previous studies [49–53], but the mechanism underlying this antagonism is insufficiently understood. Here, we studied the time course of podosome disruption upon activation of myosin-II filament assembly under conditions when localization of podosomes is defined by a micropatterned substrate (figure 1a–d; electronic supplementary material, movie S1). We plated THP1 cells differentiated into macrophages by TGFβ1 treatment on micropatterned surfaces consisting of 4 µm diameter adhesive islands coated with fibronectin separated by non-adhesive space (figure 1b). Under such conditions, the podosomes of adherent cells are concentrated in small clusters confined by the islands (figure 1c). Of note, the intensity of fibronectin fluorescence was significantly lower in zones of the islands underlying podosome clusters, presumably due to podosome-mediated matrix degradation (figure 1c). The myosin-II filaments in THP1 cells were located at the cell periphery but can also be found in the rims surrounding podosome clusters (figure 1c). The addition of the RhoA activator, CN03 (Cytoskeleton, Inc; see also [61]), triggered myosin-II filament formation within 2 min. These filaments are first concentrated at zones surrounding podosome clusters and then move towards the centre of the islands occupied by podosomes. The relocation of myosin-II filaments to within 2 µm of podosomes rapidly instigated podosome elimination (figure 1d; electronic supplementary material, movie S1). Detailed examination of images and movies revealed that the filaments never overlap with existing podosomes. Overall, our data suggest that podosomes disappear as a result of local remodelling of the actin network in their microenvironment induced by myosin-II filaments.

Figure 1.

Interrelationship between podosomes and myosin-II filaments in TGFβ1-stimulated THP1 cells. (a) Podosome actin cores visualized by phalloidin staining (red in the left panel), and myosin-IIA filaments fluorescently labelled by myosin-IIA heavy chain antibody (green in the middle panel); merged image is shown in the right panel. Scale bar, 5 µm. Note that myosin-IIA filaments are localized to the narrow peripheral zone of the cell and surround the podosome array. (b) The micropatterned substrate organized as a square lattice consisting of circular fibronectin-coated islands (4 µm diameter) arranged with 8 µm period on passivated non-adhesive substrate. The islands are visualized by fluorescently labelled fibronectin. Scale bar, 4 µm. (c) The edge of the cell attached to the fibronectin micropattern (left) is marked by the yellow line. Podosomes (actin, red) confined within the adhesive islands are surrounded by myosin-II filaments (green). The boxed area in c is shown at higher magnification in c′ (left: actin staining; right: merged image of actin and myosin-IIA filaments). Scale bars, 5 µm. (d) Time course of disruption of podosomes in cells attached to the micropatterned substrate upon activation of RhoA by CN03. The cell attached to three adhesive islands is seen. The cell was transfected with RFP-Lifeact (red) and GFP-myosin regulatory light chain (green). Podosomes are localized to the adhesive islands and surrounded by myosin-II filaments. Upper row: actin cores of podosomes; lower row: merged images of podosomes and myosin-II filaments. Note that disruption of podosomes upon addition of CN03 correlates with the assembly of myosin-II filaments. See also electronic supplementary material, movie S1. Scale bar, 5 µm. All images were taken using SIM.

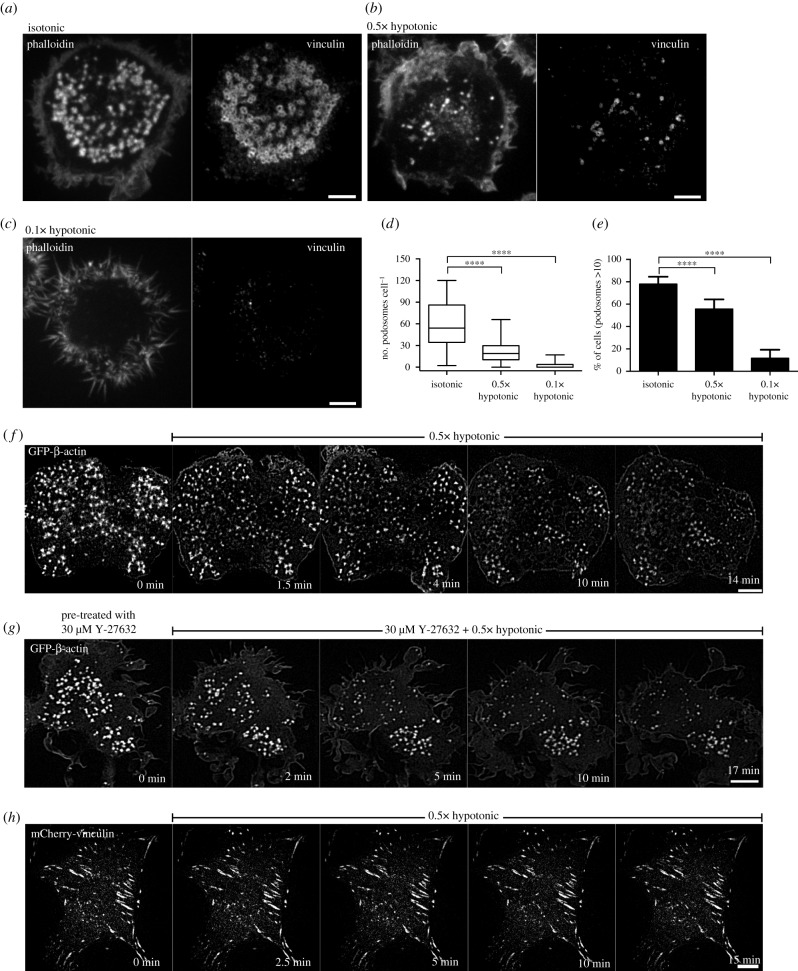

(b). Osmotic swelling disperses podosomes and promotes their disassembly

THP1 cells were exposed to RPMI media with 10% serum diluted by water to 50% or 90% dilutions (0.5× or 0.1× hypotonic, respectively) for 15 min. Such treatments are known to increase membrane tension [62–65]. Cells incubated with 0.5× hypotonic medium showed reductions in podosome number when compared with cells treated with isotonic medium (figure 2a,b,d,e). The sparse residual podosomes were approximately fivefold smaller in area than podosomes in control cells (figure 2b,f; electronic supplementary material, figure S1A,C, D and movie S2) as revealed by structured-illumination microscopy (SIM). The cells demonstrated numerous lamellipodia and increased spread area (figure 2f). The effect of 0.5× hypotonic medium on podosomes was transient, so that new podosomes appeared within an hour following medium dilution.

Figure 2.

Disruption of podosomes upon osmotic swelling. (a) Cells exposed for 15 min to isotonic (complete medium) and (b,c) hypotonic medium with 50% (b) and 90% (c) reduction in osmolarity. F-actin (left) and vinculin (right) were visualized by phalloidin and vinculin antibody staining, respectively. Scale bars, 5 µm. (d,e) Graphs showing the number of podosomes per cell presented as box-and-whiskers plots (d) and the percentage of cells with more than 10 podosomes presented as mean ± s.d. (e). In this and the following figures, the significance of the difference between groups was estimated by a two-tailed Student's t-test, and the range of p-values greater than 0.05 (non-significant), lesser than or equal to 0.05, lesser than or equal to 0.01, lesser than or equal to 0.001 and lesser than or equal to 0.0001 are denoted by ‘n.s,’, one, two, three and four asterisks (*), respectively. (f) Time-lapse SIM visualization of podosome dynamics in GFP-β-actin-transfected cell exposed to 0.5× hypotonic medium. Note dispersion and reduction in the number of podosomes upon hypotonic shock. See electronic supplementary material, movie S2. (g) Rho kinase inhibitor, Y-27632, did not prevent the disruption of podosomes upon hypotonic shock. Scale bars, 5 µm. See electronic supplementary material, movie S3. (h) Focal adhesions of mouse fibroblasts visualized by expression of mCherry-vinculin were not affected by incubation in 0.5× hypotonic medium. Scale bar, 10 µm. See electronic supplementary material, movie S4. Images a–c and d–h were taken using spinning disk confocal microscopy and SIM, respectively.

This is in line with the observations that the effect of hypotonic medium on membrane tension is transient [66]. Incubation in 0.1× hypotonic medium (90% dilution) resulted in cell retraction and formation of numerous irregular actin-rich protrusions (figure 2c). Such cells do not demonstrate any podosome-like structures for several hours. Since we demonstrated above that podosome disruption is induced by activation of myosin-II filament formation, we examined whether elimination of myosin-II filaments interfered with the effect of hypoosmotic shock. We found that in spite of complete disassembly of myosin-II filaments upon treatment with 30 µM Rho kinase inhibitor Y-27632, the 0.5× hypotonic medium still disrupts podosomes (figure 2g; electronic supplementary material, movie S3). Unlike podosomes, focal adhesions of mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) did not disassemble upon hypoosmotic shock (figure 2h; electronic supplementary material, movie S4).

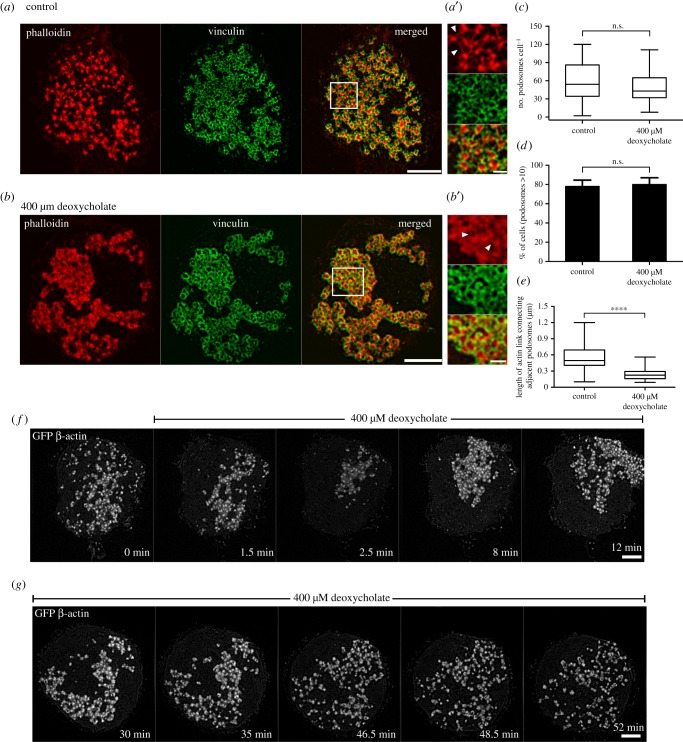

(c). Decreasing membrane tension by deoxycholate promoted the clustering of podosomes

In order to decrease membrane tension without perturbing the spread area of the cell, small concentrations of the detergent deoxycholate were used to expand the lipid bilayer [64]. The addition of 400 µM deoxycholate induced immediate disruption of podosomes, which however quickly recovered with the formation of large podosome clusters (figure 3a,b,f; electronic supplementary material, movie S5). As a result, by 5 min following deoxycholate addition, podosome number was similar to that in non-treated cells, but their organization differed significantly. Instead of individual podosomes evenly distributed over the cell ventral surface, podosomes in deoxycholate-treated cells were organized into clusters containing more than 50 podosomes each (figure 3c,d). Visualization of podosomes with high magnification using SIM revealed thin actin links connecting neighbouring podosomes in control cells. Such links were significantly shortened or entirely disappeared in the podosome clusters formed in deoxycholate-treated cells (figure 3b inset,e). The average distance between individual podosomes in the cluster was 0.24 ± 0.02 µm compared with 0.54 ± 0.04 µm in controls, so podosomes were tightly packed (figure 3e). There were no differences in actin core diameter or actin fluorescence intensity between podosomes in deoxycholate-treated and control cells (electronic supplementary material, figure S1B,C,D). The clustering effect induced by deoxycholate was, however, transient and podosomes returned to a normal distribution at about 30 min after addition of deoxycholate (figure 2g; electronic supplementary material, movie S6).

Figure 3.

Decreasing membrane tension by the detergent deoxycholate promotes podosome cluster formation. SIM visualization of podosomes in THP1 cells exposed to (a) normal complete medium and (b) 400 µM deoxycholate-containing medium for 15 min. Actin labelled with phalloidin (left, red), vinculin visualized by antibody staining (middle, green) and their merged image (right) are shown. Scale bars, 5 µm. Boxed areas in (a) and (b) are shown at higher magnification in (a′) and (b′), respectively. Scale bars, 1 µm. White arrowheads showing actin links between neighbouring podosomes. (c–e) Quantification of 15 min-deoxycholate treatment on podosomes. (c) Number of podosomes per cell presented as box-and-whiskers plots. (d) Percentage of cells with more than 10 podosomes presented as mean ± s.d. (e) Length of the actin links between podosomes. The p-values are marked by asterisks as described in the legend to figure 1. (f,g) Time-lapse images showing the evolution of podosomes upon addition of deoxycholate. (f) First 30 min following deoxycholate addition. See electronic supplementary material, movie S5. (g) Thirty to 60 min after addition of deoxcycholate. See electronic supplementary material, movie S6. The cells were transfected with GFP-β-actin to visualize the actin cores of podosomes. Scale bars, 5 µm. Note severe decrease in podosome number at 1.5–2 min following deoxycholate addition, formation of new podosomes organized into clusters at 8–35 min of incubation, with deoxycholate and recovery of uniform podosome distribution at 35 min onwards. The significance of the difference between groups was estimated by the two-tailed Student's t-test. All images were taken using SIM.

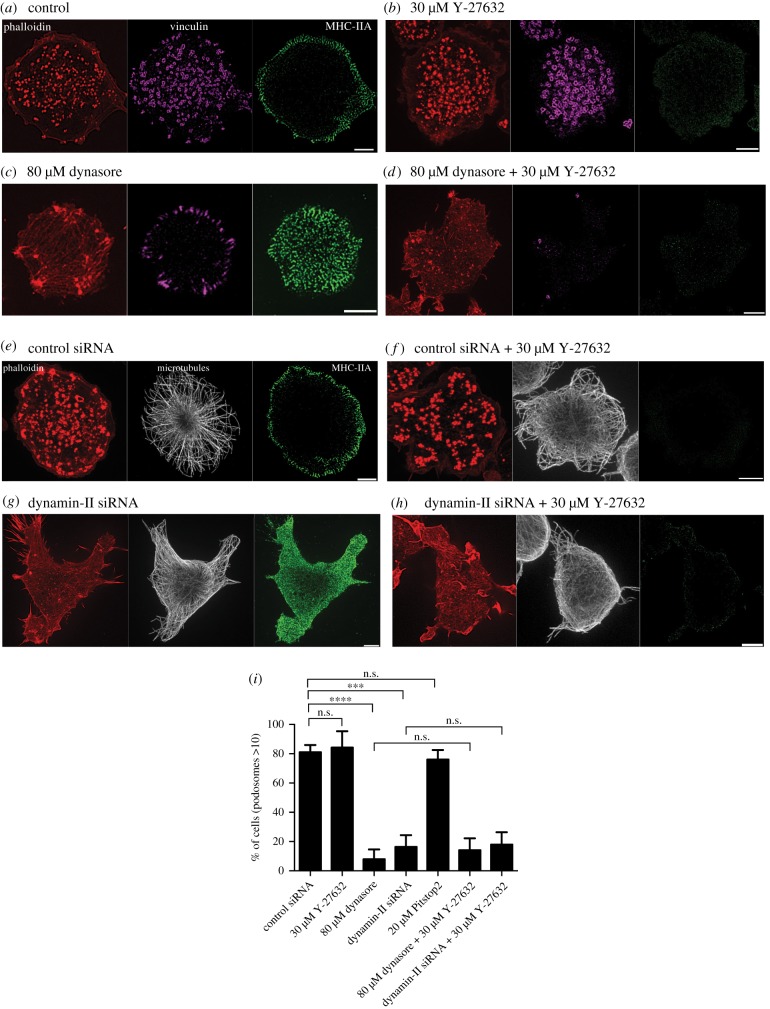

(d). Inhibition of dynamin-II but not clathrin-mediated endocytosis perturbed podosome formation

Since physical factors increasing membrane tension are known to inhibit endocytosis [63,67–70], we considered whether processes of endocytosis are involved in podosome formation and maintenance. First, we confirmed and extended previous data on the role of dynamin-II in podosomes [30] showing that inhibition of dynamin-II either by pharmacological inhibitor (dynasore) or by knockdown of dynamin-II, resulted in severe disruption of podosomes in THP1 cells and the formation of focal adhesions instead (figure 4a–i). Inspection of myosin-II organization in cells with dynamin-II inhibition revealed that such cells have significantly increased numbers of myosin-II filaments (figure 4c,g) when compared with functional dynamin-II-containing THP1 cells. These myosin-II filaments occupied the entire cytoplasm of dynasore-treated or dynamin-II knockdown cells but did not form regular myosin-II filament stacks (figure 4c,g). Since we have shown above that accumulation of myosin-II filaments leads on its own to podosome disruption, we examined whether accumulation of myosin-II filaments participate in the podosome disruption induced by dynamin-II inhibition. When dynasore was added to THP1 cells pre-treated with ROCK inhibitor Y-27632 for 30 min, podosomes were still disrupted in spite of the complete absence of myosin-II filaments in these cells (figure 4d). Of note, focal adhesions typical for dynasore-treated cells did not form in cells pre-treated with Y-27632 (figure 4c,d). Similarly, treatment with Y-27632 was insufficient to rescue podosomes in dynamin-II knockdown THP1 cells (figure 4g). These data strongly suggest that accumulation of myosin-II filaments did not participate in the disruption of podosomes induced by dynamin-II suppression.

Figure 4.

Dynamin-II inhibition or knockdown disrupts podosomes in a myosin-II-independent manner. Images of cells treated as follows: (a) 0.1% DMSO, (b) 30 µM Y-27632, (c) 80 µM dynasore, (d) 80 µM dynasore added 30 min after addition of 30 µM Y-27632, (e,f) transfected with control siRNA and untreated (e) or treated with 30 µM Y-27632 (f); (g,h) transfected with dynamin-II siRNA and untreated (g) or treated with 30 µM Y-27632 (h). The cells were fixed 1 h after addition of the last drug. Actin podosome cores were visualized by phalloidin (red); podosome rings (purple), myosin-IIA filaments (green) and microtubules (white) were visualized by immunofluorescence staining of vinculin, myosin-IIA heavy chain and α-tubulin, respectively. Scale bars, 5 µm. Note that dynasore treatment or dynamin-II knockdown disrupted podosomes and induced formation of new myosin-II filaments (c,g). Elimination of myosin-IIA filaments by Y-27632 (b,d,f,h) did not prevent the disruptive effect of dynasore or dynamin-II knockdown on podosomes (d,h). (i) Quantification of the percentage of cells having more than 10 podosomes for the treatments shown in (a–h), as well as for cells treated with the clathrin inhibitor Pitstop®2 (see electronic supplementary material, figure S2). The significance of the difference between groups was estimated by the two-tailed Student's t-test, the range of p-values > 0.05(non-significant), lesser than or equal to 0.05, lesser than or equal to 0.01, lesser than or equal to 0.001 and lesser than or equal to 0.0001 are denoted by ‘n.s.’, one, two, three and four asterisks (*), respectively. All images were taken using SIM.

We found that dynamin-II is localized to the podosome adhesive ring (electronic supplementary material, figure S2), while clathrin light chain marked patches that do not overlap with podosomes. In addition, while dynamin inhibition showed a severe disruptive effect on podosomes, the inhibitor of clathrin-mediated endocytosis via Pitstop®2 did not interfere with podosome integrity in our experiments (electronic supplementary material, figure S2A–C).

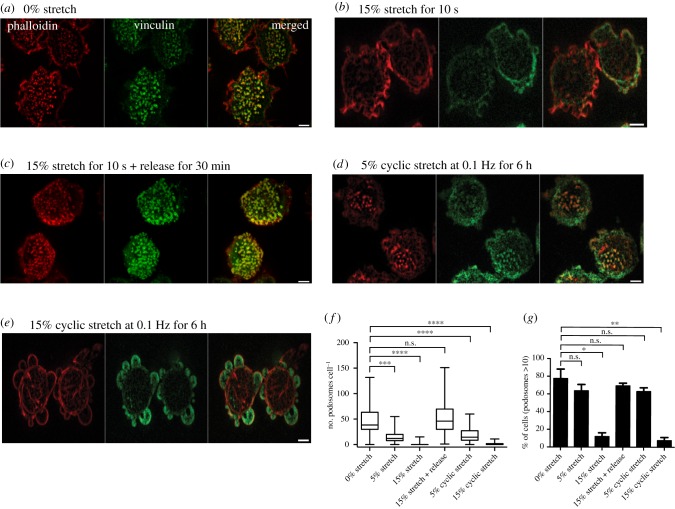

(e). Radial stretching of the substrate induces loss of podosomes

Membrane tension can also be augmented by physical stretching of the substrate to which the cell is attached [63,71]. In our study, differentiated THP1 cells were plated on PDMS surfaces coated with fibronectin which were stretched radially using a previously described device [71].

A 5% single radial stretch maintained for 10 s as well as a 5% cyclic stretch (0.1 Hz, 6 h) resulted in a modest but significant decrease in podosome number per cell (figure 5a,d,f) while the percentage of podosome-containing cells did not decrease after such treatment (figure 5g). When the stretch magnitude was increased to 15%, podosomes were completely disrupted (figure 5b,e). During such stretch, the cells formed numerous blebs (figure 5b,e). In spite of total podosome disassembly, cells remained attached to the substrate. The podosomes did not recover until the stretch was released; following stretch release, both the re-assembly of podosomes and the disappearance of the blebs were seen, with complete recovery of the control phenotype in 30 min following the release of the stretch (figure 5c). Cycles of substrate stretching and release can be repeated several times with reproducible reverse responses of podosomes and blebs. The results were not affected if the duration of single stretch was increased up to 1 min, and cyclic stretch frequency varied from 0.01 to 0.1 Hz. Collectively, the data show that podosomes respond strongly to the magnitude of stretch but not to the duration of a single stretch or frequency of cyclic stretch, and cells are capable of forming new podosomes once the strain is released (figure 5f,g).

Figure 5.

Stretching of substrate-induced podosome disassembly. (a–e) Representative images of cells on PDMS substrate coated with fibronectin fixed and stained after substrate radial stretching or release. Actin was labelled with phalloidin (left, red), vinculin was visualized by antibody staining (middle, green) and their merged image is shown in the right panel. (a) Cells on non-stretched substrate. (b) Cells subjected to 15% stretching for 10 s. (c) Cells stretched for 10 s and incubated for 30 min following the stretch release. (d,e) Cells subjected to cyclic stretching of (d) 5% and (e) 15% magnitude at 0.1 Hz for 6 h. Scale bars, 5 µm. (f,g) Quantification of (f) the number of podosomes per cell (box-and-whiskers plots), and (g) percentage of cells containing more than 10 podosomes (mean ± s.d.) for all experimental situations shown in (a–e), as well as for 5% single stretch for 10 s. Graphs represent results of two to three independent experiments. The significance of the difference between groups was estimated by the two-tailed Student's t-test, the range of p-values > 0.05(non-significant), lesser than or equal to 0.05, lesser than or equal to 0.01, lesser than or equal to 0.001 and lesser than or equal to 0.0001 are denoted by ‘n.s.’, one, two, three and four asterisks (*), respectively. All images were taken using spinning-disc confocal microscopy.

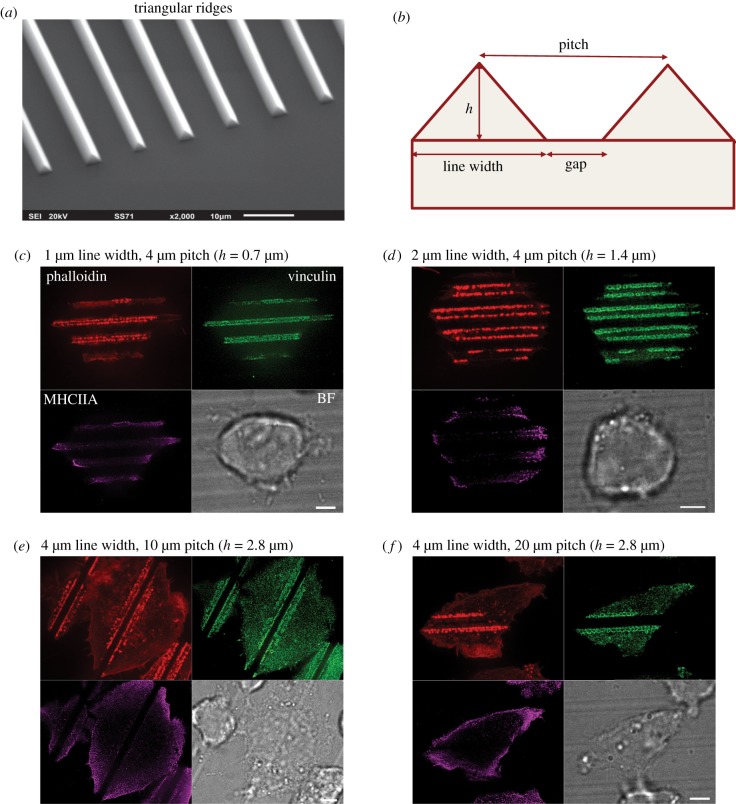

(f). Formation of linear podosome arrays induced by substrate topography

Another group of physical factors affecting podosome formation are topographical features of the substrate. It was shown previously that podosomes of dendritic cells prefer to form in the proximity of 90° steps on the substrate [72] or can be induced by pores in the nuclearpore™ filters [73]. To further explore the effects of three-dimensional topography on podosome organization, THP1 cells were plated on arrays of microfabricated parallel ridges. The ridges have the shape of a triangular prism (figure 6a) with varied widths, heights and distance between them (pitch) (figure 6b). We have found that cells plated on fibronectin-coated substrates with such ridges showed highly ordered podosome formation, which formed single or double chains along edges of the triangular ridges regardless of their heights or the spacing between them (figure 6c–f). Cells were capable of forming multiple streaks of single or double chains of podosomes depending on the spacing between the ridges (figure 6c–f). If the distance between the ridges was large, podosomes could also be formed at the flat areas between the ridges. However, the distance between neighbouring podosomes oriented along the ridges was always smaller than between those on the flat surface. Moreover, the podosomes aligned along narrow-width ridges sometimes apparently fused with each other (figure 6c). This suggests that sensing local topography can favour the assembly of podosomes.

Figure 6.

Podosome formation in response to topographical cues. (a) Scanning electron microscopy image of PDMS substrate with triangular ridges. (b) Schematic diagram of profile of the substrate with triangular ridges. The PDMS substrate was coated with fibronectin (1 µg ml−1) for 1 h. The width of the ridges, distances between them (pitch) and ridges' height (h) were varied as shown in (c–f). In each panel, four views of the same cell are presented: actin cores visualized by phalloidin staining (upper left, red), podosome adhesive domains visualized by vinculin staining (upper right, green), distribution of myosin-IIA filaments (lower left, purple) and bright field image of the cell (lower right). Scale bars, 5 µm. Note that in all cases, podosomes are aligned along both sides of the ridges, and not formed in other regions of the cell. At the substrate with smallest ridges (pitch: 1 µm), the discrete actin cores are seen but vinculin is not organized into ring-shaped structures. At pitches 2–20 µm, chains of typical podosomes are seen. Myosin-IIA filaments are located at the cell periphery similarly to the case of cells plated on planar substrate. Images (c–f) were taken using SIM.

Examination of distribution of myosin-IIA filaments in cells on the patterned substrates revealed that filaments remained at the cell periphery, forming a subcortical ring similar to that seen in cells on a flat substrate (figure 6c). This suggests that formation of podosome arrays at the edges of the triangular ridges is not a consequence of reorganization of myosin-IIA filaments. Moreover, podosomes formed in cells treated with the microtubule-disrupting drug nocodazole and Rho kinase inhibitor Y-27632 still aligned along the ridges (electronic supplementary material, figure S3). These cells had only a few residual microtubules associated with the microtubule organizing centre and completely lacked myosin-II filaments, showing that neither microtubules nor myosin-II filaments are required for the alignment of podosomes along topographical cues.

3. Discussion

In this study, we explored the effects of several types of factors on the integrity of podosomes in macrophage-type cells. We confirmed and extended the disruptive effect of myosin-IIA filaments on podosomes. By direct observation of the interaction of small groups of podosomes with surrounding myosin-IIA filaments, we found that activation of myosin-II filament formation affects podosomes locally, and the distance at which myosin-II filaments exert their effect is in the micrometre range. The process of podosome disassembly upon local activation of myosin-II filament formation was rapid and lasted less than a minute. The disassembly of myosin-II filaments, known to have a profound disruptive effect on focal adhesion integrity [17,37–40], does not affect podosomes.

There are several not necessarily mutually exclusive mechanisms by which excessive assembly of myosin-II filaments can interfere with podosome integrity. Myosin-II filaments under certain conditions can depolymerize actin [74,75] or disintegrate branching actin networks nucleated by the Arp2/3 complex. Forces generated through interaction of myosin-II and actin filaments may therefore interfere with the Arp2/3-mediated actin polymerization in podosomes. Finally, myosin-II filaments underlying the plasma membrane could affect membrane tension or curvature [76,77] in such a way that hinders the formation of podosomal protrusions.

We therefore investigated the role of physical factors in regulation of podosome integrity and dynamics including those affecting membrane tension and sculpting. We have clearly shown that hypoosmotic shock, known to transiently increase membrane tension [66], results in transient disassembly of podosomes. Of note, suppression of myosin-II filament formation by Rho kinase inhibitor Y-27632 does not prevent or rescue the disruptive effect of hypoosmotic shock on podosomes. The decrease in membrane tension by treatment with deoxycholate also exerts a profound effect on podosomes resulting in podosome clustering.

Dynamin-II, known for its function in membrane fission [78] and regulation of actin polymerization [79], is required for podosome integrity [30,31]. We checked whether the disruptive effect of dynamin-II inhibition on podosomes is mediated by myosin-IIA filament formation. This conjecture was motivated by our observation that treatment of THP1 cells with the dynamin inhibitor, dynasore, triggered the formation of multiple myosin-IIA filaments. However, inhibition of myosin-IIA filament formation by Rho kinase inhibitor did not prevent the disruptive effect of either dynamin inhibition or dynamin-II knockdown on podosomes. Thus, not all podosome-disrupting factors operate via myosin-II filaments and, in particular, manipulations with membrane tension or sculpting can affect podosomes directly.

We further investigated the effects of single or cyclic substrate stretching on podosome integrity and clearly showed that such manipulations result in reversible disassembly of podosomes. This effect can be explained by the increase in membrane tension upon stretching observed in previous studies [63,80]. However, in addition to membrane tension, the substrate stretching was shown to activate RhoA [81] and reinforce contractility [82] which suggests that formation of myosin-IIA filaments is activated. Thus, the effect of substrate stretching on podosomes is most probably a result of the combined action of increased membrane tension and augmented myosin-II filament formation.

A common feature of all podosome-disrupting treatments discussed above is their inhibitory effect on endocytosis. Indeed, it is well documented that increase in membrane tension via osmotic swelling inhibits endocytosis [63,67,69,83]. Substrate stretching is also known to interfere with endocytosis [63]. Finally, dynamin, a protein required for multiple forms of endocytosis [84], is indispensible for podosome integrity. The sensitivity of podosomes to factors inhibiting endocytosis can be explained by the possible role of endocytosis in the membrane balance at podosomes. Podosomes seem to be the sites of intense insertion of new membrane required for both protrusional activity and exocytosis of vesicles containing metalloproteinases degrading the extracellular matrix [11]. Therefore, compensatory endocytosis [85] could be needed for the maintenance of membrane equilibrium. Since inhibition of clathrin-mediated endocytosis did not affect podosome integrity in our experiments, the endocytosis that might be required for podosome integrity is probably clathrin-independent.

Of note, the sensitivity of both endocytosis and podosome formation to similar experimental treatments could also reflect the similarity between the processes of endocytosis and podosome formation. In both cases, the mechanism depends on membrane remodelling mediated by the actin cytoskeleton. Further elucidation of this analogy is an interesting avenue for future studies.

The unique dependence of podosome formation on substrate topography described in this study and previous publications [72,73] provides another example of podosome regulation. Indeed, we have found that alignment of podosomes along the triangular ridges of microfabricated substrates is not accompanied by apparent changes in the distribution of myosin-II filaments. Moreover, total disruption of myosin-II filaments did not prevent alignment of podosomes along the ridges. Thus, the podosome regulation by topographical cues is myosin-II independent. However, this does not prove directly that the podosome alignment in this situation is regulated by membrane deformation or changes in membrane tension. Further studies are needed to elucidate the mechanism of substrate topography-dependent regulation of podosomes.

Summing up, our study revealed two groups of mechanisms affecting podosome integrity and dynamics involving myosin-IIA filament reorganization and membrane tension/shape changes, respectively. These mechanisms seem to be operating for podosomes rather than other types of integrin adhesions, such as focal adhesions. Further elucidation of these mechanisms will be important for understanding podosome-dependent processes where these are of important biological consequence, such as three-dimensional cell migration and tumour cell invasion.

4. Material and methods

(a). Cell culture, plasmid and transfection procedures

THP1 human monocytic leukaemia cell line was obtained from the Health Protection Agency Culture Collections (Porton Down, Salisbury, UK) and cultured using Roswell Park Memorial Institute medium (RPMI-1640) supplemented with 10% HI-FBS and 50 µg ml−1 2-Mercaptoethanol (Sigma-Aldrich) at 37°C and 5% CO2.

The suspension-cultured THP-1 cells were differentiated into adherent macrophage-like cells with 1 ng ml−1 human recombinant cytokine TGFβ1 (R&D Systems) for either 24 or 48 h on fibronectin-coated glass substrates. No apparent difference between the phenotype of cells stimulated for either 24 or 48 h was detected. The 35 mm ibidi (cat. 81158) glass-bottomed dishes were coated with 1 µg ml−1 of fibronectin (Calbiochem, Merck Millipore) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for at least 1 h at 37°C, washed with PBS twice and incubated in complete medium containing TGFβ1 prior to seeding of cells.

THP1 stably expressing GFP-β-actin (described in Cox et al. [86]) or stably co-expressing red-fluorescent protein (RFP)-Lifeact and human green-fluorescent protein (GFP)-myosin regulatory light chain (MRLC) (described in Rafiq et al. [51,87]) were used in all live experiments concerning podosome studies.

For dynamin-II knockdown, THP1 cells were transfected with 100 nM of dynamin-II siRNA (Dharmacon, ON-TARGETplus SMARTpool siRNA, catalogue no. L-004007-00-0005). For control experiments, non-targeting pool siRNA (Dharmacon, ON-TARGETplus, catalogue no. D-001810-10) was used at a similar concentration. Cells were transfected using electroporation (Neon Transfection System, Life Technologies) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. Specifically, two pulses of 1400 V for 20 ms were used.

Immortalized rptp-α(+/+) MEFs [88], termed MEFs, were obtained from the Sheetz Laboratory (Mechanobiology Institute, Singapore). MEFs were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's Medium high glucose (DMEM), supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated foetal bovine serum (HI-FBS, Gibco), 1% l-glutamine and 100 IU mg−1 penicillin–streptomycin (Invitrogen) at 37°C and 5% CO2. MEFs were either seeded on fibronectin-coated 35 mm ibidi or 27 mm IWAKI (Japan) glass-bottomed dishes for 24 h post-transfection.

For focal adhesion analysis, MEFs were transiently electroporated (Neon Transfection System, Life Technologies) with mCherry-Vinculin (Dr Michael W. Davidson, Florida State University, FL, USA) with a single pulse of 1400 V for 20 ms.

(b). Immunofluorescence

THP1 cells were fixed for 15 min with 3.7% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS, washed twice in PBS, permeabilized for 10 min with 0.5% Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich) in PBS and then washed twice again in PBS. For microtubule visualization, cells were fixed and simultaneously permeabilized for 15 min at 37°C in a mixture of 3% PFA–PBS, 0.25% Triton X-100 and 0.2% glutaraldehyde in PBS, and then washed twice with PBS for 10 min. Before immunostaining, samples were quenched for 15 min on ice with 1 mg ml−1 sodium borohydride in cytoskeleton buffer (10 mM MES, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EGTA, 5 mM MgCl2, 5 mM glucose, pH 6.1). Fixed cells were blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin or 5% FBS for 1 h at room temperature prior to incubation with the following primary antibodies overnight at 4°C: anti-tubulin (Sigma-Aldrich, catalogue no. T6199, dilution 1 : 400); anti-vinculin (Sigma-Aldrich, catalogue no. V9131, dilution 1 : 400); anti-non-muscle heavy chain of myosin-IIA (Sigma-Aldrich, catalogue no. M8064, dilution 1 : 500); samples were washed with PBS three times and incubated with Alexa Fluor-conjugated secondary antibodies (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 1 h at room temperature, followed by three washes in PBS. F-actin was visualized by Alexa Fluor 488 Phalloidin (Thermo Fisher Scientific), Phalloidin-TRITC (Sigma-Aldrich) or Alexa Fluor 647 Phalloidin (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

(c). Osmotic shock and drug treatments

Pharmacological treatments were performed using the following concentrations of inhibitors or activators: 30 µM Y-27632 dihydrochloride (Sigma-Aldrich), 80 µM for dynasore (Sigma-Aldrich), 400 µM deoxycholate (Sigma-Aldrich), 0.1 µg ml−1 Rho Activator II (CN03, Cytoskeleton) and 1 µM nocodazole (Sigma-Aldrich). The duration of the treatment with the inhibitors was 1 h unless otherwise stated. In some cases, cells were pre-treated with one inhibitor for 30 min and then another inhibitor was added for an additional 1 h. For hypotonic experiments, cells were exposed to solutions containing complete medium diluted in sterile water at 1 : 1 (0.5× hypotonic) or 1 : 9 (0.1× hypotonic) using a perfusion chamber (CM-B25-1, Chamlide CMB chamber) and the image was acquired just prior to the start of acquisition.

(d). Micro-patterning of adhesive islands using UV-induced molecular adsorption

Adhesive islands with a diameter of 4 µm were printed in square lattices with a period of 8 µm. Clean glass coverslips were sealed with NOA 73 liquid adhesive to plastic-containing dishes by UV treatment for 2 min, and were then treated with oxygen plasma for 5 min. The coverslips were coated with PLL-g-PEG (PLL(20)-g[3.5]-PEG(5), SuSoS AG, Dübendorf, Switzerland) at 100 µg ml−1 in PBS for at least 8 h followed by multiple washes with PBS. For micropattern printing, the PRIMO system (Alveole, France) mounted on an inverted microscope (Nikon Eclipse Ti-E, Japan) equipped with a motorized scanning stage (Physik Instrumente, Germany) was used as Digital Micro-mirror Device (DMD) to create a UV pattern at 105 µm above the focal plane of the microscope. After alignment of specimen with the UV pattern by using the Leonardo software (Alveole, France), a solution of photoinitiator (PLPP, Alveole, France) was incubated on the dishes. Depending on the UV exposure and time, the UV-activated photoinitiator molecules locally cleaved the PEG chains, which permits subsequent local deposition of proteins. The dishes were washed with PBS multiple times prior to incubation with labelled fibronectin (Alexa 488 Fibronectin, Cytoskeleton, Inc., 50 µg ml−1) or unlabelled fibronectin mixed with Fibrinogen Alexa 647 (ThermoFisher Scientific, 50 µg ml−1) at a ratio of 20 : 1 for 10 min. After several washes with PBS, THP1 cells were plated on these micropatterned lattices for SIM imaging.

(e). Cell stretching assay

THP1 cells were subjected to 0, 5 or 15% single or cyclic radial stretch using the stretching device described in Cui et al. [71]. Briefly, cells were plated on a layer of polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) coated with 10 µg ml−1 fibronectin, in a stretching unit. The substrate stretching was generated via changing the pressure in a chamber underneath the stretchable substrate. For single stretch experiments, cells were incubated under stretched conditions for 10 s, and then fixed as described above. The stretching itself lasted for less than a second [71]. For single stretch recovery experiments, cells were released from stretching 30 min prior to fixing. For cyclic stretching, cells were exposed to stretching with a frequency of 0.1 Hz at 5 or 15% stretch magnitude and then fixed.

(f). Fluorescence microscopy

THP1 cells (in figures 2a–c and 5) and MEFs (in figure 2h) were imaged in complete medium (unless stated otherwise) using a spinning-disc confocal microscope (PerkinElmer Ultraview VoX) attached to an Olympus IX81 inverted microscope, equipped with a 100× oil immersion objective (1.40 NA, UPlanSApo) and EMCCD camera (C9100-13, Hamamatsu Photonics) for image acquisition. Volocity software (PerkinElmer) was used to control the image acquisition. For all other images, two types of SIM equipments were used: (i) spinning-disc confocal microscopy (Roper Scientific) coupled with the Live SR module [89], Nikon Eclipse Ti-E inverted microscope with Perfect Focus System, controlled by MetaMorph software (Molecular device) supplemented with a 100× oil 1.45 NA CFI Plan Apo Lambda oil immersion objective and sCMOS camera (Prime 95B, Photometrics); (ii) Nikon N-SIM microscope, based on a Nikon Ti-E inverted microscope with Perfect Focus System controlled by Nikon NIS-Elements AR software supplemented with a 100× oil immersion objective (1.40 NA, CFI Plan-ApochromatVC) and EMCCD camera (Andor Ixon DU-897).

(g). Microfabrication of triangular ridges

The coverslips with PDMS structures on top were produced by adapting a moulding protocol from Migliorini et al. [90]. Silicon moulds 15 × 15 mm2 wide with 1.5 mm long trenches of triangular cross-section with different sizes and pitch were prepared via silicon anisotropic etching. Briefly, standard single-side-polished silicon wafers with 300 nm of thermally grown SiO2 were spin-coated with 1 µm thick AZ5214E-positive tone photo-resist. The pattern was then produced with direct writing in a DWL-66fs Heidelberg laser writer equipped with a diode-laser-emitting light at 375 nm wavelength. After development for 1 min in AZ400 K diluted 1 : 4 in DI water, the patterned resist mask was then used to etch the silicon oxide layer in a Samco 10NR RIE tool using CF4/O2 etching chemistry (40/4 sccm, respectively), 15 Pa, 150 W applied through an RF generator at 13.56 MHz, as described in Ashraf et al. [91]. After stripping the resist, 10 min of anisotropic etching in 5 M KOH at 80°C produced the triangular trenches with the designed sizes. After the anisotropic etching, the silicon oxide was removed with immersion in a buffered oxide etching solution (a solution of 1 : 7 of HF : NH4F in water; this etching solution is selective for silicon oxide but does not attack Si). The wafer was then diced in the single dyes, and each was coated with an anti-sticking self-assembled monolayer of Trichloro(1H,1H,2H,2H-perfluorooctyl)silane by vapour deposition. PDMS (Sylgard 184, Dow Cornig, USA) was prepared in 10 : 1 ratio with its reticulation agent and degassed for 30 min in a vacuum jar after careful mixing. A 10 µm layer was spin-coated on the coverslip (4000 rpm for 60 s) and degassed a second time for 10 min. A silanized mould was then placed on top of the PDMS coating and gently pressed to the coverslip with around 150 kPa of pressure to facilitate the filling of the triangular cavities. While keeping the pressure applied, the assembly was transferred on a Hot Plate and the temperature raised to 120°C, where PDMS reticulation was left to proceed for 30 min. After cooling down to room temperature, the silicon mould was peeled off revealing the structured PDMS layer on top of the coverslip with the triangular ridges.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Data accessibility

This article has no additional data.

Authors' contributions

A.D.B. conceived and designed the project together with G.E.J., V.V. and M.M.K. N.B.M.R designed and performed all experiments and prepared the manuscript; G.G. and C.K.L. provided assistance in carrying out experiments and discussed results. A.D.B. and N.B.M.R, together with G.E.J., V.V. and M.M.K. discussed results and prepared the manuscript.

Competing interest

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Funding

This research is supported by the National Research Foundation, Prime Minister's Office, Singapore and the Ministry of Education under the Research Centres of Excellence programme through the Mechanobiology Institute, Singapore (ref. no. R-714-006-006-271) (A.D.B., N.B.M.R., G.G., V.V.) and Singapore Ministry of Education Academic Research Fund Tier 3 MOE grant no. MOE2016-T3-1-002 (A.D.B., V.V.). G.E.J. is supported by the Medical Research Council, UK (G1100041, MR/K015664) and the generous provision of a visiting professorship from the Mechanobiology Institute, Singapore. A.D.B. also acknowledges support from a Maimonides Israeli-France grant (Israeli Ministry of Science Technology and Space) and EU Marie Skłodowska-Curie Network InCeM (Project ID: 642866) at the Weizmann Institute of Science. N.B.R. is also funded by a joint National University of Singapore-King's College London graduate studentship.

References

- 1.Burns S, Thrasher AJ, Blundell MP, Machesky L, Jones GE. 2001. Configuration of human dendritic cell cytoskeleton by Rho GTPases, the WAS protein, and differentiation. Blood 98, 1142–1149. ( 10.1182/blood.v98.4.1142) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Calle Y, Burns S, Thrasher AJ, Jones GE. 2006. The leukocyte podosome. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 85, 151–157. ( 10.1016/j.ejcb.2005.09.003) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cervero P, Panzer L, Linder S. 2013. Podosome reformation in macrophages: assays and analysis. Methods Mol. Biol. 1046, 97–121. ( 10.1007/978-1-62703-538-5_6) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Luxenburg C, Geblinger D, Klein E, Anderson K, Hanein D, Geiger B, Addadi L. 2007. The architecture of the adhesive apparatus of cultured osteoclasts: from podosome formation to sealing zone assembly. PLoS ONE 2, e0000179 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0000179) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hai CM, Hahne P, Harrington EO, Gimona M. 2002. Conventional protein kinase C mediates phorbol-dibutyrate-induced cytoskeletal remodeling in a7r5 smooth muscle cells. Exp. Cell Res. 280, 64–74. ( 10.1006/excr.2002.5592) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moreau V, Tatin F, Varon C, Genot E. 2003. Actin can reorganize into podosomes in aortic endothelial cells, a process controlled by Cdc42 and RhoA. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23, 6809–6822. ( 10.1128/mcb.23.19.6809-6822.2003) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schachtner H, et al. 2013. Megakaryocytes assemble podosomes that degrade matrix and protrude through basement membrane. Blood 121, 2542–2552. ( 10.1182/blood-2012-07-443457) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yu CH, Rafiq NB, Krishnasamy A, Hartman KL, Jones GE, Bershadsky AD, Sheetz MP. 2013. Integrin-matrix clusters form podosome-like adhesions in the absence of traction forces. Cell Rep. 5, 1456–1468. ( 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.10.040) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen WT. 1989. Proteolytic activity of specialized surface protrusions formed at rosette contact sites of transformed cells. J. Exp. Zool. 251, 167–185. ( 10.1002/jez.1402510206) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nitsch L, Gionti E, Cancedda R, Marchisio PC. 1989. The podosomes of Rous-sarcoma virus-transformed chondrocytes show a peculiar ultrastructural organization. Cell Biol. Int. Rep. 13, 919–926. ( 10.1016/0309-1651(89)90074-X) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murphy DA, Courtneidge SA. 2011. The ‘ins’ and ‘outs’ of podosomes and invadopodia: characteristics, formation and function. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 12, 413–426. ( 10.1038/nrm3141) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yamaguchi H, Pixley F, Condeelis J. 2006. Invadopodia and podosomes in tumor invasion. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 85, 213–218. ( 10.1016/j.ejcb.2005.10.004) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Patla I, Volberg T, Elad N, Hirschfeld-Warneken V, Grashoff C, Fassler R, Spatz JP, Geiger B, Medalia O. 2010. Dissecting the molecular architecture of integrin adhesion sites by cryo-electron tomography. Nat. Cell Biol. 12, 909–915. ( 10.1038/ncb2095) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hu S, Tee YH, Kabla A, Zaidel-Bar R, Bershadsky A, Hersen P. 2015. Structured illumination microscopy reveals focal adhesions are composed of linear subunits. Cytoskeleton 72, 235–245. ( 10.1002/cm.21223) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Young LE, Higgs HN. 2018. Focal adhesions undergo longitudinal splitting into fixed-width units. Curr. Biol. 28, 2033–2045. ( 10.1016/j.cub.2018.04.073) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kanchanawong P, Shtengel G, Pasapera AM, Ramko EB, Davidson MW, Hess HF, Waterman CM. 2010. Nanoscale architecture of integrin-based cell adhesions. Nature 468, 580–584. ( 10.1038/nature09621) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Riveline D, Zamir E, Balaban NQ, Schwarz US, Ishizaki T, Narumiya S, Kam Z, Geiger B, Bershadsky AD. 2001. Focal contacts as mechanosensors: externally applied local mechanical force induces growth of focal contacts by an mDia1-dependent and ROCK-independent mechanism. J. Cell Biol. 153, 1175–1186. ( 10.1083/jcb.153.6.1175) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hotulainen P, Lappalainen P. 2006. Stress fibers are generated by two distinct actin assembly mechanisms in motile cells. J. Cell Biol. 173, 383–394. ( 10.1083/jcb.200511093) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oakes PW, Beckham Y, Stricker J, Gardel ML. 2012. Tension is required but not sufficient for focal adhesion maturation without a stress fiber template. J. Cell Biol. 196, 363–374. ( 10.1083/jcb.201107042) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iskratsch T, Yu CH, Mathur A, Liu S, Stevenin V, Dwyer J, Hone J, Ehler E, Sheetz M. 2013. FHOD1 is needed for directed forces and adhesion maturation during cell spreading and migration. Dev. Cell 27, 545–559. ( 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.11.003) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.DeMali KA, Barlow CA, Burridge K. 2002. Recruitment of the Arp2/3 complex to vinculin: coupling membrane protrusion to matrix adhesion. J. Cell Biol. 159, 881–891. ( 10.1083/jcb.200206043) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chorev DS, Moscovitz O, Geiger B, Sharon M. 2014. Regulation of focal adhesion formation by a vinculin-Arp2/3 hybrid complex. Nat. Commun. 5, 3758 ( 10.1038/ncomms4758) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Linder S, Nelson D, Weiss M, Aepfelbacher M. 1999. Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein regulates podosomes in primary human macrophages. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 96, 9648–9653. ( 10.1073/pnas.96.17.9648) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Calle Y, Jones GE, Jagger C, Fuller K, Blundell MP, Chow J, Chambers T, Thrasher AJ. 2004. WASp deficiency in mice results in failure to form osteoclast sealing zones and defects in bone resorption. Blood 103, 3552–3561. ( 10.1182/blood-2003-04-1259) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Anton IM, Jones GE, Wandosell F, Geha R, Ramesh N. 2007. WASP-interacting protein (WIP): working in polymerisation and much more. Trends Cell Biol. 17, 555–562. ( 10.1016/j.tcb.2007.08.005) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Luxenburg C, Parsons JT, Addadi L, Geiger B. 2006. Involvement of the Src-cortactin pathway in podosome formation and turnover during polarization of cultured osteoclasts. J. Cell Sci. 119, 4878–4888. ( 10.1242/jcs.03271) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chellaiah M, Kizer N, Silva M, Alvarez U, Kwiatkowski D, Hruska KA. 2000. Gelsolin deficiency blocks podosome assembly and produces increased bone mass and strength. J. Cell Biol. 148, 665–678. ( 10.1083/jcb.148.4.665) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zalli D, Neff L, Nagano K, Shin NY, Witke W, Gori F, Baron R. 2016. The actin-binding protein cofilin and its interaction with cortactin are required for podosome patterning in osteoclasts and bone resorption in vivo and in vitro. J. Bone Miner. Res. 31, 1701–1712. ( 10.1002/jbmr.2851) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Blangy A, Touaitahuata H, Cres G, Pawlak G. 2012. Cofilin activation during podosome belt formation in osteoclasts. PLoS ONE 7, e45909 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0045909) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ochoa GC, et al. 2000. A functional link between dynamin and the actin cytoskeleton at podosomes. J. Cell Biol. 150, 377–389. ( 10.1083/Jcb.150.2.377) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Destaing O, Ferguson SM, Grichine A, Oddou C, De Camilli P, Albiges-Rizo C, Baron R.. 2013. Essential function of dynamin in the invasive properties and actin architecture of v-Src induced podosomes/invadosomes. PLoS ONE 8, e77956 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0077956) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cox S, Jones GE. 2013. Imaging cells at the nanoscale. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 45, 1669–1678. ( 10.1016/j.biocel.2013.05.010) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kedziora KM, Isogai T, Jalink K, Innocenti M. 2016. Invadosomes—shaping actin networks to follow mechanical cues. Front. Biosci. 21, 1092–1117. ( 10.2741/4444) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wiesner C, Le-Cabec V, El Azzouzi K, Maridonneau-Parini I, Linder S. 2014. Podosomes in space. Cell Adhes. Migr. 8, 179–191. ( 10.4161/cam.28116) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mersich AT, Miller MR, Chkourko H, Blystone SD. 2010. The formin FRL1 (FMNL1) is an essential component of macrophage podosomes. Cytoskeleton 67, 573–585. ( 10.1002/cm.20468) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Panzer L, Trube L, Klose M, Joosten B, Slotman J, Cambi A, Linder S. 2016. The formins FHOD1 and INF2 regulate inter- and intra-structural contractility of podosomes. J. Cell Sci. 129, 298–313. ( 10.1242/jcs.177691) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Even-Ram S, Doyle AD, Conti MA, Matsumoto K, Adelstein RS, Yamada KM. 2007. Myosin IIA regulates cell motility and actomyosin-microtubule crosstalk. Nat. Cell Biol. 9, 299–309. ( 10.1038/ncb1540) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vicente-Manzanares M, Zareno J, Whitmore L, Choi CK, Horwitz AF. 2007. Regulation of protrusion, adhesion dynamics, and polarity by myosins IIA and IIB in migrating cells. J. Cell Biol. 176, 573–580. ( 10.1083/jcb.200612043) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Choi CK, Vicente-Manzanares M, Zareno J, Whitmore LA, Mogilner A, Horwitz AR. 2008. Actin and alpha-actinin orchestrate the assembly and maturation of nascent adhesions in a myosin II motor-independent manner. Nat. Cell Biol. 10, 1039–1050. ( 10.1038/ncb1763) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Alexandrova AY, Arnold K, Schaub S, Vasiliev JM, Meister JJ, Bershadsky AD, Verkhovsky AB. 2008. Comparative dynamics of retrograde actin flow and focal adhesions: formation of nascent adhesions triggers transition from fast to slow flow. PLoS ONE 3, e3234 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0003234) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yu CH, Law JB, Suryana M, Low HY, Sheetz MP. 2011. Early integrin binding to Arg-Gly-Asp peptide activates actin polymerization and contractile movement that stimulates outward translocation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 20 585–20 590. ( 10.1073/pnas.1109485108) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sniadecki NJ, Anguelouch A, Yang MT, Lamb CM, Liu Z, Kirschner SB, Liu Y, Reich DH, Chen CS. 2007. Magnetic microposts as an approach to apply forces to living cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104, 14 553–14 558. ( 10.1073/pnas.0611613104) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Geiger B, Spatz JP, Bershadsky AD. 2009. Environmental sensing through focal adhesions. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 10, 21–33. ( 10.1038/nrm2593) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shemesh T, Bershadsky AD, Kozlov MM. 2012. Physical model for self-organization of actin cytoskeleton and adhesion complexes at the cell front. Biophys. J. 102, 1746–1756. ( 10.1016/j.bpj.2012.03.006) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Elosegui-Artola A, Oria R, Chen Y, Kosmalska A, Perez-Gonzalez C, Castro N, Zhu C, Trepat X, Roca-Cusachs P. 2016. Mechanical regulation of a molecular clutch defines force transmission and transduction in response to matrix rigidity. Nat. Cell Biol. 18, 540–548. ( 10.1038/ncb3336) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Case LB, Waterman CM. 2015. Integration of actin dynamics and cell adhesion by a three-dimensional, mechanosensitive molecular clutch. Nat. Cell Biol. 17, 955–963. ( 10.1038/ncb3191) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hu S, et al. 2017. Long-range self-organization of cytoskeletal myosin II filament stacks. Nat. Cell Biol. 19, 133–141. ( 10.1038/ncb3466) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Changede R, Xu X, Margadant F, Sheetz MP. 2015. Nascent integrin adhesions form on all matrix rigidities after integrin activation. Dev. Cell 35, 614–621. ( 10.1016/j.devcel.2015.11.001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bhuwania R, Cornfine S, Fang Z, Kruger M, Luna EJ, Linder S. 2012. Supervillin couples myosin-dependent contractility to podosomes and enables their turnover. J. Cell Sci. 125, 2300–2314. ( 10.1242/jcs.100032) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cervero P, Wiesner C, Bouissou A, Poincloux R, Linder S. 2018. Lymphocyte-specific protein 1 regulates mechanosensory oscillation of podosomes and actin isoform-based actomyosin symmetry breaking. Nat. Commun. 9, 515 ( 10.1038/s41467-018-02904-x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rafiq NB, Lieu ZZ, Jiang T, Yu CH, Matsudaira P, Jones GE, Bershadsky AD. 2017. Podosome assembly is controlled by the GTPase ARF1 and its nucleotide exchange factor ARNO. J. Cell Biol. 216, 181–197. ( 10.1083/jcb.201605104) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.van Helden SF, Oud MM, Joosten B, Peterse N, Figdor CG, van Leeuwen FN.. 2008. PGE2-mediated podosome loss in dendritic cells is dependent on actomyosin contraction downstream of the RhoA-Rho-kinase axis. J. Cell Sci. 121, 1096–1106. ( 10.1242/jcs.020289) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dulyaninova NG, Ruiz PD, Gamble MJ, Backer JM, Bresnick AR. 2018. S100A4 regulates macrophage invasion by distinct myosin-dependent and myosin-independent mechanisms. Mol. Biol. Cell 29, 632–642. ( 10.1091/mbc.E17-07-0460) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Labernadie A, et al. 2014. Protrusion force microscopy reveals oscillatory force generation and mechanosensing activity of human macrophage podosomes. Nat. Commun. 5, 5343 ( 10.1038/ncomms6343) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Proag A, Bouissou A, Mangeat T, Voituriez R, Delobelle P, Thibault C, Vieu C, Maridonneau-Parini I, Poincloux R. 2015. Working together: spatial synchrony in the force and actin dynamics of podosome first neighbors. ACS Nano 9, 3800–3813. ( 10.1021/nn506745r) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kronenberg NM, Liehm P, Steude A, Knipper JA, Borger JG, Scarcelli G, Franze K, Powis SJ, Gather MC. 2017. Long-term imaging of cellular forces with high precision by elastic resonator interference stress microscopy. Nat. Cell Biol. 19, 864–872. ( 10.1038/ncb3561) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tsuboi S, et al. 2009. FBP17 mediates a common molecular step in the formation of podosomes and phagocytic cups in macrophages. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 8548–8556. ( 10.1074/jbc.M805638200) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Doherty GJ, Ahlund MK, Howes MT, Moren B, Parton RG, McMahon HT, Lundmark R. 2011. The endocytic protein GRAF1 is directed to cell-matrix adhesion sites and regulates cell spreading. Mol. Biol. Cell 22, 4380–4389. ( 10.1091/mbc.E10-12-0936) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sztacho M, Segeletz S, Sanchez-Fernandez MA, Czupalla C, Niehage C, Hoflack B. 2016. BAR proteins PSTPIP1/2 regulate podosome dynamics and the resorption activity of osteoclasts. PLoS ONE 11, e0164829 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0164829) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sanchez-Barrena MJ, Vallis Y, Clatworthy MR, Doherty GJ, Veprintsev DB, Evans PR, McMahon HT. 2012. Bin2 is a membrane sculpting N-BAR protein that influences leucocyte podosomes, motility and phagocytosis. PLoS ONE 7, e52401 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0052401) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Flatau G, Lemichez E, Gauthier M, Chardin P, Paris S, Fiorentini C, Boquet P. 1997. Toxin-induced activation of the G protein p21 Rho by deamidation of glutamine. Nature 387, 729–733. ( 10.1038/42743) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Batchelder EL, Hollopeter G, Campillo C, Mezanges X, Jorgensen EM, Nassoy P, Sens P, Plastino J. 2011. Membrane tension regulates motility by controlling lamellipodium organization. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 11 429–11 434. ( 10.1073/pnas.1010481108) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kosmalska AJ, et al. 2015. Physical principles of membrane remodelling during cell mechanoadaptation. Nat. Commun. 6, 7292 ( 10.1038/ncomms8292) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Raucher D, Sheetz MP. 2000. Cell spreading and lamellipodial extension rate is regulated by membrane tension. J. Cell Biol. 148, 127–136. ( 10.1083/jcb.148.1.127) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gauthier NC, Fardin MA, Roca-Cusachs P, Sheetz MP. 2011. Temporary increase in plasma membrane tension coordinates the activation of exocytosis and contraction during cell spreading. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 14 467–14 472. ( 10.1073/pnas.1105845108) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Raucher D, Sheetz MP. 1999. Characteristics of a membrane reservoir buffering membrane tension. Biophys. J. 77, 1992–2002. ( 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77040-2) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rauch C, Farge E. 2000. Endocytosis switch controlled by transmembrane osmotic pressure and phospholipid number asymmetry. Biophys. J. 78, 3036–3047. ( 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76842-1) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hassinger JE, Oster G, Drubin DG, Rangamani P. 2017. Design principles for robust vesiculation in clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, E1118–E1127. ( 10.1073/pnas.1617705114) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dai J, Ting-Beall HP, Sheetz MP. 1997. The secretion-coupled endocytosis correlates with membrane tension changes in RBL 2H3 cells. J. Gen. Physiol. 110, 1–10. ( 10.1085/jgp.110.1.1) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wu XS, Elias S, Liu H, Heureaux J, Wen PJ, Liu AP, Kozlov MM, Wu LG. 2017. Membrane tension inhibits rapid and slow endocytosis in secretory cells. Biophys. J. 113, 2406–2414. ( 10.1016/j.bpj.2017.09.035) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cui Y, Hameed FM, Yang B, Lee K, Pan CQ, Park S, Sheetz M. 2015. Cyclic stretching of soft substrates induces spreading and growth. Nat. Commun. 6, 6333 ( 10.1038/ncomms7333) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.van den Dries K, et al. 2012. Geometry sensing by dendritic cells dictates spatial organization and PGE(2)-induced dissolution of podosomes. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 69, 1889–1901. ( 10.1007/s00018-011-0908-y) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Baranov M, Ter Beest M, Reinieren-Beeren I, Cambi A, Figdor CG, van den Bogaart G. 2014. Podosomes of dendritic cells facilitate antigen sampling. J. Cell Sci. 127, 1052–1064. ( 10.1242/jcs.141226) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Haviv L, Gillo D, Backouche F, Bernheim-Groswasser A. 2008. A cytoskeletal demolition worker: myosin II acts as an actin depolymerization agent. J. Mol. Biol. 375, 325–330. ( 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.09.066) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wilson CA, et al. 2010. Myosin II contributes to cell-scale actin network treadmilling through network disassembly. Nature 465, 373–377. ( 10.1038/nature08994) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Elliott H, Fischer RS, Myers KA, Desai RA, Gao L, Chen CS, Adelstein RS, Waterman CM, Danuser G. 2015. Myosin II controls cellular branching morphogenesis and migration in three dimensions by minimizing cell-surface curvature. Nat. Cell Biol. 17, 137–147. ( 10.1038/ncb3092) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Fischer RS, Gardel M, Ma X, Adelstein RS, Waterman CM. 2009. Local cortical tension by myosin II guides 3D endothelial cell branching. Curr. Biol. 19, 260–265. ( 10.1016/j.cub.2008.12.045) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Antonny B, et al. 2016. Membrane fission by dynamin: what we know and what we need to know. EMBO J. 35, 2270–2284. ( 10.15252/embj.201694613) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sever S, Chang J, Gu C. 2013. Dynamin rings: not just for fission. Traffic 14, 1194–1199. ( 10.1111/tra.12116) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Diz-Munoz A, Thurley K, Chintamen S, Altschuler SJ, Wu LF, Fletcher DA, Weiner OD. 2016. Membrane tension acts through PLD2 and mTORC2 to limit actin network assembly during neutrophil migration. PLoS Biol. 14, e1002474 ( 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002474) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Goldyn AM, Rioja BA, Spatz JP, Ballestrem C, Kemkemer R. 2009. Force-induced cell polarisation is linked to RhoA-driven microtubule-independent focal-adhesion sliding. J. Cell Sci. 122, 3644–3651. ( 10.1242/jcs.054866) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Krishnan R, et al. 2009. Reinforcement versus fluidization in cytoskeletal mechanoresponsiveness. PLoS ONE 4, e5486 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0005486) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Thottacherry JJ, et al. 2018. Mechanochemical feedback control of dynamin independent endocytosis modulates membrane tension in adherent cells. Nat. Commun. 9, 4217 ( 10.1038/s41467-018-06738-5) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ferguson SM, De Camilli P.. 2012. Dynamin, a membrane-remodelling GTPase. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 13, 75–88. ( 10.1038/nrm3266) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Watanabe S, Boucrot E. 2017. Fast and ultrafast endocytosis. Curr. Opin Cell Biol. 47, 64–71. ( 10.1016/j.ceb.2017.02.013) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Cox S, Rosten E, Monypenny J, Jovanovic-Talisman T, Burnette DT, Lippincott-Schwartz J, Jones GE, Heintzmann R. 2012. Bayesian localization microscopy reveals nanoscale podosome dynamics. Nat. Methods 9, 195–200. ( 10.1038/nmeth.1812) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Rafiq NBM, et al. 2019. A mechano-signalling network linking microtubules, myosin IIA filaments and integrin-based adhesions. Nat. Mater. 18, 638–649. ( 10.1038/s41563-019-0371-y) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Su J, Muranjan M, Sap J.. 1999. Receptor protein tyrosine phosphatase α activates Src-family kinases and controls integrin-mediated responses in fibroblasts. Curr. Biol. 9, 505–511. ( 10.1016/S0960-9822(99)80234-6) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.York AG, Chandris P, Nogare DD, Head J, Wawrzusin P, Fischer RS, Chitnis A, Shroff H. 2013. Instant super-resolution imaging in live cells and embryos via analog image processing. Nat. Methods 10, 1122–1126. ( 10.1038/nmeth.2687) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Migliorini E, Grenci G, Ban J, Pozzato A, Tormen M, Lazzarino M, Torre V, Ruaro ME. 2011. Acceleration of neuronal precursors differentiation induced by substrate nanotopography. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 108, 2736–2746. ( 10.1002/bit.23232) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ashraf M, Sundararajan SV, Grenci G. 2017. Low-power, low-pressure reactive-ion etching process for silicon etching with vertical and smooth walls for mechanobiology application. J. Micro/Nanolithogr., MEMS, MOEMS 16, 034501 ( 10.1117/1.Jmm.16.3.034501) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

This article has no additional data.