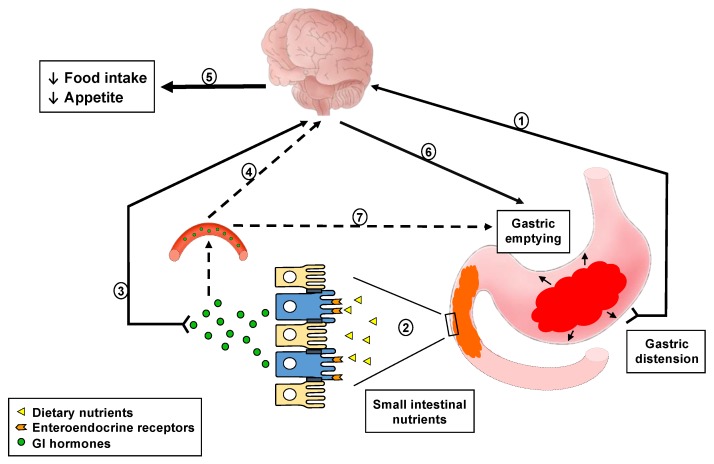

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the gastrointestinal (GI) sensing of meal-related stimuli, and effects on GI functions (specifically gut hormone release and slowing of gastric emptying), appetite and energy intake. Meal ingestion initially induces gastric distension, which activates mechanoreceptors on vagal afferents that terminate in the gastric wall and transmit this signal to the central nervous system (1). As chyme enters the small intestine in the process of gastric emptying, nutrients are sensed by receptors located on enteroendocrine cells, triggering GI hormone secretion (2). GI hormones convey meal-related information to the brain involving various pathways, including activation of hormone-specific receptors on vagal afferent endings (3) or following transport through the blood stream (4). Together, these inputs are conveyed to higher brain centres to modulate eating behaviour, appetite and energy intake (5), as well as feedback regulation of GI motor functions, particularly pyloric pressures, associated with the slowing of gastric emptying (6). The latter can also occur through endocrine pathways (7).