Abstract

Multivalent carbohydrate-based ligands were synthesized and evaluated as inhibitors of the adhesion protein HA of the influenza A virus (IAV). HA relies on multivalency for strong viral adhesion. While viral adhesion inhibition by large polymeric molecules has proven viable, limited success was reached for smaller multivalent compounds. By linking of sialylated LAcNAc units to di- and trivalent scaffolds, inhibitors were obtained with an up to 428-fold enhanced inhibition in various assays.

Introduction

Influenza A virus (IAV) causes the flu and poses a serious threat to human health. History has shown that the flu can lead to serious pandemics, with millions of deaths in 19181 and a risk of future outbreaks of deadly variants.2 IAV contains two envelope glycoproteins that bind to sialylated glycans. The hemagglutinin (HA) is responsible for attachment of the virus to the tissue surface to be infected, and its specificity lies at the origin of the species specificity and tissue tropism of the virus, while it is also of importance for the viral fusion with the endosome.3 The neuraminidase (NA) is a glycosidase enzyme that removes the sialic acid group from glycans which leads to a release of the HA-based attachment4 and allows the virus to burrow through the protective mucosa and enter the cell. Importantly, the NA also allows the progeny virions to be released from the cell surface to infect other cells. A functional balance is needed between the binding and cleavage properties of NA and HA.4−6

IAVs cause seasonal epidemics and occasional pandemics. The latter are caused by animal viruses that managed to cross the animal–human species barrier. Prophylactic and therapeutic options against influenza are limited. Several approaches are being used, the most common of which is the vaccination strategy. This is a valuable approach for the seasonal IAV variants that are very common and infective, yet usually only life threatening for those with weakened immune systems. Vaccination is complicated by the large antigenic variation in HA and NA with currently 16 HA and 9 NA subtypes of varying antigenicity known.3 Also within HA and NA subtypes changes in antigenicity resulting from mutational variation (antigenic drift) are observed. Nevertheless recent progress was reported toward prophylactic and therapeutic vaccines.7 In case of an epidemic, neuraminidase inhibitors such as oseltamivir or zanamivir can be used to reduce the illness symptoms and infectivity.8 Unfortunately, resistance of IAV to these neuraminidase inhibitors has been observed9 which greatly hampers the effectiveness of the therapy. Similar to the approach to HIV infections, it will likely be more effective to use a combination therapy that addresses HA and NA and possibly additional targets.

While NA was proven to be a druggable target that yielded nanomolar inhibitors with improved glycomimetic and prodrug characteristics to overcome some of the challenges of carbohydrate drugs,10 the situation is different for HA. The adhesion protein binds only with millimolar affinities to sialylated glycan receptors. Binding has been observed to α2,6-SiaLAcNAc for the human type specific HAs or α2,3-SiaLAcNAc for avian type-specific HAs.5,11−13 The low affinities are a challenging starting point for a carbohydrate based drug development program, but also non-carbohydrate approaches have faced this challenge.14 The virus, however, binds with high affinity to tissue surfaces by using multivalency,15 which increases its avidity to levels that enable infection. The multivalency effects involve the simultaneous binding of glycans to more than one of the three binding sites per HA trimer on the IAV surface but also the simultaneous binding of cell surface glycans to multiple HA protein trimers on the viral surface. The overall avidity effects are very strong4 and crucial for IAV. In that sense it is a logical step to attempt to block the viral infection via the HA protein with a multivalent inhibitor.

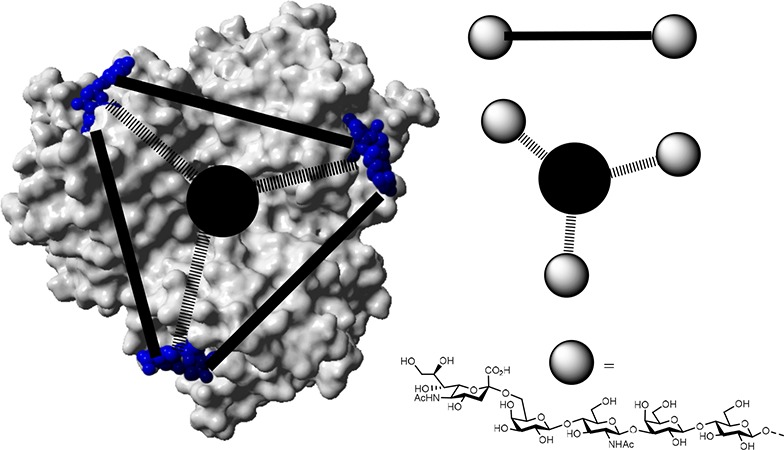

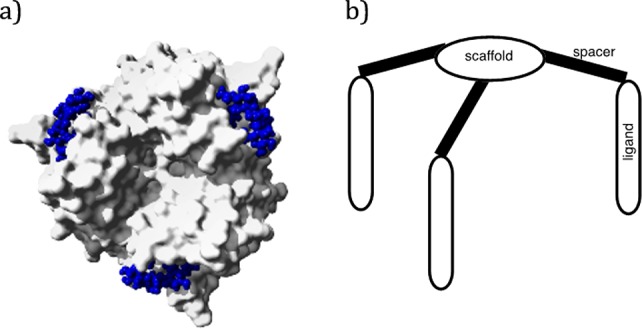

We here describe our use of di- and trivalent scaffolds as multivalent scaffolds to inhibit IAV (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

(a) Top view of an X-ray structure of an HA trimer protein bound to three molecules of α-2,3-SiaLac (PDB code 1HGG).11 (b) Schematic tripodal ligand design for the chelation type inhibition of influenza virus A hemagglutinin protein.

These scaffolds were extended with α2,6-SiaLacNAc linked to lactose. The largest of the compounds were larger (more atoms in the spacers between sialic acid units; see Supporting Information) than a biantennary Sia(LacNAc)3 linked to a trimannose core, known for chelation.16 The constructs were evaluated as inhibitors in a viral binding assay and were shown to be significantly stronger inhibitors than their monovalent counterparts, and they were hardly affected by neuraminidases. Finally, they were also shown to inhibit IAV infection.

Multivalency as a strategy to enhance binding and inhibition has been widely explored in protein–carbohydrate interactions17,18 to bridge binding sites19 or inhibit pathogen binding20 by mechanisms such as chelation and statistical rebinding.21,22 Indeed several examples of multivalent sialic acid containing glycans have been reported. Relatively large molecular entities can take advantage of their size to bridge multiple HA trimers.23 Some of these have yielded potency enhancements of 3–4 orders of magnitude. Such systems include a polyacrylate carrier,24 polyacrylamide,25,26 polyglutamic acid,27 polyglycerol based nanoparticles,28,29 chitosan,30 and liposomes.31

For drug development it would be an advantage if monodisperse, small well-defined molecular entities can be used, with no risk of immunogenicity. Reaching this goal has proven considerably more difficult. Reported studies by Knowles et al. showed that certain divalent sialiosides,32,33 did not exhibit enhanced HA binding when exposed to an HA trimer but were able to enhance hemagglutination inhibition when the HAs were present on a viral surface. Their convincing proof showed that the compounds were able to bridge between HA trimers, an aggregation mechanism, the benefits of which are not well understood.19 Similar observations were made by others including a system containing two α-2,6-SiaLacNAc units linked via a single galactoside moiety,34 dendrimers presenting sialic acids,35 cyclic peptides presenting sialyl lactosides,36 and a calixarene linked to four sialic acids.37 These constructs resulted in moderate enhancements, and they did not have the structural features now known to be needed to bridge between binding sites within an HA trimer (∼67 atoms in the bridge between sialic acids).16 An interesting case is a system based on a trisubstituted benzene ring linked to sialic acids via peptidic spacer arms. This construct with the right dimensions to bridge binding sites was reported to bind to immobilized HA by SPR with a Kd of 450 nM.38 However, the peptidic component showed significant binding indicative of peptide protein interactions but indeed leading to an overall potent compound. In another system, a three-way junction DNA for the display of α-2,3-SiaLac units was shown to be potent, but a single arm was not much less potent. This is indicative of DNA–protein interactions and makes a bridging mechanism less likely.39 A system based on PNA-DNA complexes displaying two α-2,6-SiaLacNAc units at various distances was also reported.12 Evidence for true chelation, i.e., bridging between binding sites, was provided and yielded a ∼30-fold enhancement (15-fold per sugar) over a DNA-PNA reference construct containing only a single glycoligand. Unfortunately, these noncovalent constructs of ∼21 kDa are not small molecules. Other indications that chelation of HA binding sites is indeed possible come from carbohydrate array experiments with biantennary glycans. They showed that glycans with at least three LacNAc units in each of the arms bound more strongly to human type specific HAs.16 Molecular modeling supported the chelation mode and indicated that two LacNAc units would be too short. This chelation type binding was shown to only be possible for the human type specific HA binding to α2,6-linked sialic acid for geometrical reasons and is precluded for the α2,3-linked ones.6

On the basis of these clear indications that chelation is possible, we directed our efforts to make di- and trivalent ligands for the HA protein of IAV that can engage more than one of its three binding sites at the same time.

Results

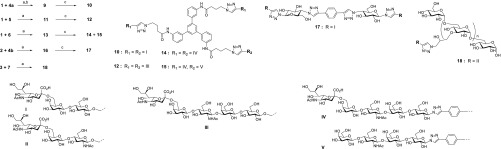

The synthesis started with the preparations of the building blocks shown in Figure 2. Their detailed syntheses can be found in the Supporting Information. Compounds 1–3 are the core or scaffold structures outfitted with azido groups. The other compounds 4–8 are the glycans that contain alkyne groups for linkage to 1–3 by CuAAC conjugation. Compound 1 represents a trivalent scaffold derived from a known triamine40 with the potential to display three glycans toward all three HA binding sites of the trimer. Compound 2 is a divalent spacer with rigid elements such as a direct linkage between glucose and triazole, a motif that was previously explored in rigid spacers for enhanced multivalency effects.41−43 Compound 3 is a polymeric dextran scaffold44 for comparison with the “small” molecule scaffolds 1 and 2. Compounds 4, 5, and 8 were made from propargyl lactose, and 7 was made from LacNAc, and azidolactose and 1,4-diethynylbenzene were the starting materials for 6 via CuAAC. The β1,3-linked GlcNAc and β1,4-linked Gal moieties of 5, 6, and 8 were introduced using glycosyl transferases. Similarly, the α-2,6-linked sialic acid part of 7 and 8 was added using a sialyl transferase.

Figure 2.

Structures of the building blocks used in the synthesis of the multivalent carbohydrate HA inhibitors.

The alkyne-linked lactose/LacNAc building blocks 4a, 5, and 6 were coupled to the azido scaffolds 1 and 2 via CuAAC conjugation as shown in Scheme 1. The products were purified and in one case deprotected (synthesis of 9) before the final sialylation with the sialyltransferase enzyme PmSTI mutant, which was mutated to achieve the desired 2,6 specificity.45 The products were purified by preparative HPLC to yield the fully sialylated 10, 12, 14, and 17.

Scheme 1. Synthesis of Multivalent HA Inhibitors.

Reagents and conditions: (a) CuSO4·5H2O, Na ascorbate, DMF/H2O (9:1), microwave, 80 °C; (b) NaOMe, MeOH; (c) CMP-NANA, PmSTI mutant.

In the sialyation of 13 also the disialylated 15 was obtained and purified as a useful reference compound. In our hands, performing the CuAAC conjugation with the sialylated building blocks such as 7 and 8 was problematic, which is the reason for the strategy of performing the sialylation as the last step on the multivalent precursor.

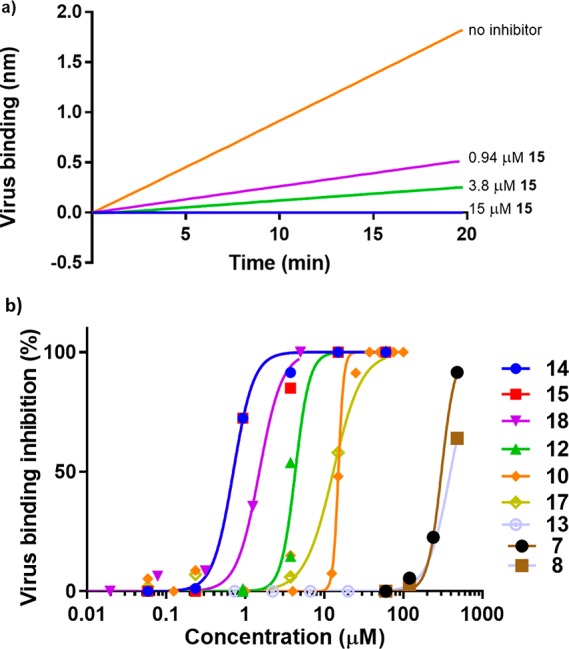

The inhibition studies were conducted with the use of a biolayer interferometry (BLI) assay.4 In this assay a streptavidin coated sensor was loaded with a sialylated glycoprotein LAMP1. Influenza A virus WU95 (containing a H3 protein of a human H3N2 virus; see Supporting Information) was used, and its binding to the sensor could readily be observed. Performing the experiment in the presence of the inhibitors clearly showed inhibition (Figure 3a). By use of a range of concentrations for each compound, inhibition curves were obtained (Figure 3B) and the results were quantified (Table 1).

Figure 3.

(a) Analysis of inhibition of virus-receptor binding by BLI. Real-time kinetic analysis of virus binding to LAMP1 was performed by BLI. A representative experiment of concentration-dependent inhibition of virus binding by 15 is shown as determined by the BLI wavelength shift. (b) Inhibition curves of compounds from left to right, 14 (blue), 15 (red, obstructed by 14), 18 (purple), 12 (green), 17 (yellow), 10 (orange), 8 (brown), and 7 (light purple), of the virus-receptor binding determined similarly as shown in (a).

Table 1. Results of IAV Inhibition by Multivalent Carbohydrates Using BLI and HAI Assays.

| entry | construct | glycoligand | valency | IC50 BLI (μM)d | rel pot. (per sugar)a | Ki HAI (μΜ) | rel pot. (per sugar)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 7 | SiaLacNAc | 1 | 304 ± 11 | 1 (1) | ndc | |

| 2 | 8 | SiaLacNAcLac | 1 | 396 ± 3 | 1 (1) | 360 ± 139 | 1 (1) |

| 3 | 13 | LacNAcLac-triazole-Ph | 3 | no inhib at 20 μM | ndc | ||

| 4 | 10 | SiaLac | 3 | 15 ± 0.3 | 20 (7) | 53 ± 15 | 7 (2) |

| 5 | 17 | SiaLac | 2 | 13 ± 1 | 23 (12) | ndc | |

| 6 | 12 | SiaLacNAcLac | 3 | 4.3 ± 3.7 | 71 (24) | ndc | |

| 7 | 14 | SiaLacNAcLac-triazole-Ph | 3 | 0.71 ± 0.08 | 428 (143) | 9.4 ± 3.8 | 38 (13) |

| 8 | 15 | SiaLacNAcLac-triazole-Ph | 2 | 0.71 ± 0.15 | 428 (214) | 10.3 ± 5.6 | 35 (17) |

| 9 | 18 | SiaLacNAc | 55 | 1.51 ± 0.16 | 201 (4) | 3.75 ± 1.4 | 96 (2) |

Relative to the potency of 7.

Relative to the potency of 8.

Not determined.

in the presence of 10 μM oseltamivir carboxylate.

First to note is that the inhibition with the two reference compounds 7 and 8 showed relatively low IC50’s below the millimolar level that is commonly associated with the binding of sialic acid derivatives to whole virus or HA. Another notable fact is that the inhibition of the two compounds is very similar, indicating that the added lactose moiety of 8 does not help the binding. Another reference compound was 13. It contains the triphenylbenzene core linked to the LacNAcLac arms. The combined presence of the hydrophobic aromatic core and the 12 sugar moieties did not yield any detectable inhibition in the assay up to the 20 μM used in the assay.

Compounds 14 and 15 were the most potent in the assay, with IC50 of 0.7 μM, representing a 428-fold enhancement over reference 7. The two compounds were strikingly similar in the assay, clearly indicating that two sialic acid groups were sufficient and that simultaneous binding to all three HA sites with 14 was not achieved. The fact that both compounds were similar indicates that the expected statistical advantage of 14 is compensated by other factors. The trivalent compounds with the shorter linker 12 and shorter ligand moieties 10 were considerably weaker inhibitors with IC50 of 4.3 and 15 μM, respectively, indicating the importance of the length of the arm. The divalent scaffold 2 contains a similar number of atoms separating the azido groups as trivalent scaffold 1. Notably, the compound based on 2, i.e., 17, had very similar potency when compared to the one derived from 1, i.e., 10. This result again indicates that divalent binding is likely. Furthermore, it indicates the importance of the length of the arm, as the longer arms lead to enhanced inhibition. Interestingly, the polymeric glycoconjugate 18, while a potent inhibitor with an IC50 of 1.5 μM, was weaker than the tri- and divalent 14 and 15 and much more so when corrected for valency, as the relative potency per sugar is only 3.75.

In addition to BLI experiments with an H3-containing virus (WU95), we analyzed the inhibitory activity of 14 against another human virus (H1N1) and an avian H5N1 virus. The human H1N1 virus was efficiently and fully inhibited, although with a somewhat higher IC50 (2.7 μM) than the H3 containing virus. In contrast the avian H5N1 virus could be inhibited maximally 50%, which probably relates to differences in the receptor-binding properties of the different viruses. The fact that full inhibition of H5N1 was not achieved is likely caused by this virus preferring binding to α2,3- over α2,6-linked sialic acids, both of which are present on the glycoprotein receptor, while the inhibitor contains α2,6-SiaLAcNAc.46

The above experiments were run in the presence of 10 μM neuraminidase inhibitor oseltamivir carboxylate (OC) to inhibit the neuraminidase that could potentially cleave off the sialic acid moieties from the inhibitors. A direct comparison was made between experiments involving inhibitory concentrations (3 μM) of 14, 15, and 12 in the presence of oseltamivir carboxylate, with the same experiments without the NA inhibitor. These experiments showed very similar degrees of inhibition. Repeating these experiments with a different IAV, i.e., VI75 (containing H3 from another H3N2 virus; see Supporting Information), showed, first, similar degrees of inhibition and, second, no effect of oseltamivir carboxylate.

Besides the BLI assay, also a hemagglutination inhibition (HAI) assay was performed using the H3-containg WU95 virus for a number of our compounds. Results are shown in Table 1. Overall the results show the same trends but the Ki’s for the most potent compounds 14 and 15 were not as low but still in the low micromolar range. It should be noted that the conditions are different in both assays, and especially multivalency effects can vary due to the in vitro assay conditions.47 Notably the receptor density on red blood cells is considerably higher than present in the BLI assay.

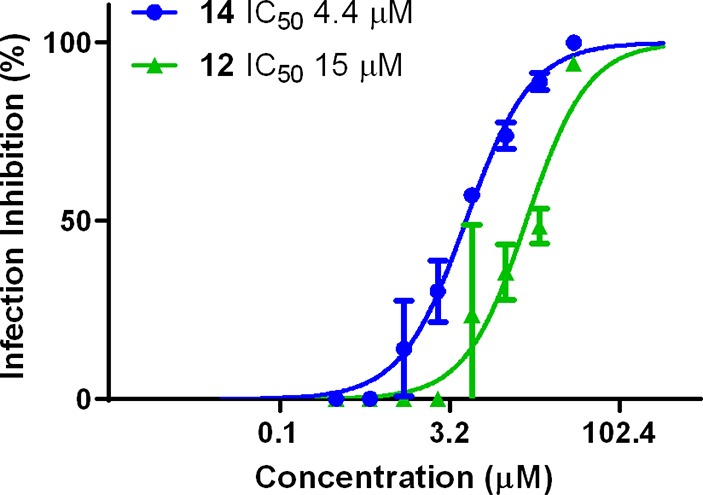

To further evaluate the potential of the compounds as IAV inhibitors, an infection inhibition test was performed using the H3-containing WU95 virus. As such, MDCK-II cells were exposed to IAV at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.005 tissue culture infectious dose 50 (TCID50) per cell in the presence and absence of 14 or 12 at different concentrations without the presence of an NA inhibitor. At 7 h postinfection the number of infected cells were determined (see Figure 4), and IC50 values were determined. In agreement with the BLI results, 14 (IC50 = 4.4 μM) inhibited infection more efficiently than 12 (IC50 = 15 μM). Furthermore, it was determined that the two compounds did not cause significant cytotoxicity (see Supporting Information). In addition, we analyzed the ability of the compounds to prevent cell killing by virus infection. Again, 14 was more effective than 12 (see Supporting Information). Finally, we analyzed whether synergy could be observed between HA inhibitor 15 and NA inhibitor oseltamivir carboxylate. Low nanomolar concentrations of each showed little effect, but when they were combined, a significant reduction of infection was observed (see Supporting Information).

Figure 4.

Infection of MDCK-II cells by H3-containing WU95 virus in the presence or absence of 14 and 12. Inhibition of infection relative to infection in the absence of compounds is graphed.

Discussion and Conclusions

We here showed the successful synthesis of multivalent sialic acid containing glycoconjugates. Their synthesis was possible by a combination of chemical scaffold synthesis, enzymatic carbohydrate synthesis, and CuAAC conjugation. The well-defined systems were found to inhibit the binding of IAV in a dose dependent manner. Clearly a combination of structural features is needed for inhibition as a single sugar arm is weakly active and the non-sialyl system is not active. Enhancements of 428-fold were achieved with the system containing two or three sialic acid units. Furthermore, the use of divalent systems showed similar results to experiments performed with trivalent systems. Therefore, not all three binding sites can be occupied simultaneously by our system, but two seem possible, as previously indicated for large biantennary glycans39 and DNA bridged divalent ligands.12 The length of the glycan arm is an important factor in the potency.

Hemaglutination inhibition experiments gave the same trends as the BLI assay, but effects were smaller. A difference was seen in the degree of inhibition and multivalency effects. Overall the data are consistent with a bivalent chelating binding mode.6,12,48 As such this is the first example of a nonmacromolecular compound to demonstrate this and indicates that with additional optimization a therapeutic avenue is within reach. Compounds 14 and 12 were tested in infection inhibition assays and cell killing inhibition assays. In both of these cases inhibition is clearly observed, and the order of potency is consistent with that from the BLI assay. Furthermore, no toxicity was observed for these compounds. In the BLI assay it was remarkable that no effect of the NA inhibitor oseltamivir carboxylate was observed. Furthermore, in the infection inhibition assay no NA inhibitor was added, yet full inhibition was observed. Others38 have seen a similar nonresponse to NA blocking before and explained it with (1) the tight inhibitor binding to HA, resulting in less availability for NA, (2) weak inherent NA activity, especially on the α-2,6 isomers, and (3) a lower presence of NA compared to HA. For medical application of this type of NA inhibiting compound the introduction of an S-linked sialic acid, as previously reported,49 is nevertheless recommended to ensure sialic acid cleavage from the inhibitor by NA does not happen. In agreement herewith, 15 showed a synergistic effect with NA inhibitor OC. Low nanomolar concentrations of either reagent had no major effect, but the combination greatly reduced infections. This result supports the notion of a combination therapy, as practiced for HIV. The multivalent approach as described here may not be limited to IAV but can likely be extended to other systems as previously shown for adenovirus.50

Experimental Section

Chemistry

Compounds 2,423,514b52 and propargyl were synthesized as previously reported. Yields of individual reactions and spectra data are reported in the Supporting Information. All tested compounds were >95% pure by HPLC.

Tris-azide (1)

1,3,5-Tris(3-aminophenyl)benzene40 (70 mg, 0.2 mmol) was dissolved in DCM (5 mL). 4-Azidobutanoic acid (77 mg, 0.6 mmol, 3 equiv) was added, followed by DMAP (7.3 mg, 0.06 mmol, 0.3 equiv), EDC·HCl (190 mg, 1.0 mmol, 5 equiv). The mixture was stirred for 48 h at room temperature. Then the solution was washed with 1 M HCl solution, followed by saturated NaHCO3 solution and by saturated NaCl solution. After drying (Na2SO4) the solvent was removed, and the residue was purified using column chromatography over silica gel (eluent DCM/MeOH 75:1 v/v) to give 55 mg (40%) of an off-white solid.

General Procedure for the Synthesis of LacNAc Sequences in 5 and 6

The appropriate lactoside (1 equiv, ∼0.03 mmol) and UDP-GlcNAc (1.5 equiv) were dissolved in HEPES buffer (50 mM, pH 7.3, 2.5 mL) containing KCl (25 mM), MgCl2 (2 mM), and dithiothreitol (1 mM). To this, 20 μL of CIAP (10 mU) and 50 μL of H. pylori β3GlcNAcT (β1-3GlcNAc transferase) were added. The resulting reaction mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 14 h, followed by Biogel P-2 and silica gel (6) purification. The resulting GlcNAc glycan (0.007–0.017 mmol, 1 equiv) and UDP-Gal (1.5 equiv) were dissolved in MES buffer (100 mM, 300–500 μL) containing MnCl2 (20 mM). To this, 30–50 μL of LgtB (β1-4Gal Transferase) was added. The resulting reaction mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 3 h. The reaction mixture was centrifuged, and the supernatant was purified by gel filtration over Biogel P-2 (eluent H2O).

General Procedure for the Enzymatic 2,6-Sialylation in the Synthesis of 7, 8, 10, 12, 14, 15, and 17

The appropriate LacNAc derivative (1 equiv) and CMP-NANA (1.2–3.3 equiv per LacNAc unit) were dissolved in Tris-HCl buffer (100 mM, pH 7.5, 200–500 μL) containing MgCl2 (20 mM). To this, PmST1 mutant P34H/M144L (α2-6 sialyltransferase, 20–50 μL) was added to the reaction mixture. Then the resulting reaction mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 4 h. The reaction mixture was centrifuged and the supernatant subjected to gel filtration over Biogel P-2 (eluent H2O). Fractions containing product were combined and lyophilized for further preparative HPLC (HILIC column) for 12, 14, 15, and 16.

General Procedure for CUAAC Conjugation in the Synthesis of 9a, 11, 13, 16

The appropriate azido compound (1 equiv) and alkyne (1.3–2.3 equiv per azido group), CuSO4·5H2O (0.04–0.5 equiv), sodium l-ascorbate (2.5 equiv) were dissolved in DMF/H2O (0.2–2 mL). The reaction was performed under microwave irradiation (80–100 °C, 1–1.5 h). Then the mixture was concentrated in vacuo. The residue was purified by silica chromatography (DCM/MeOH 20:1 v/v) for 9a and Biogel P-2 (eluent H2O) for the others.

Polymer 18

The azido polymer (3) was dissolved in water followed by the addition of 7 (3 mg, 1.3 equiv). CuSO4·5H2O (0.1 equiv) and sodium l-ascorbate (0.3 equiv) were dissolved in water separately and added to the reaction mixture. The reaction was carried out at 100 °C with microwave radiation for 60 min. The solvent was evaporated, and the crude reaction mixture was purified by dialysis using a cellulose based dialysis cassette (MWCO: 2K) against deionized water for 3–4 days and freeze-dried to give a white compound (3 mg, 24%). The disappearance of the azide stretching peak in the IR spectra of the final compound confirmed that all of the azido groups had reacted.

Acknowledgments

W.L., W.D., and G.Y. gratefully acknowledge financial support by a scholarship from the China Scholarship Council CSC, http://www.csc.edu.cn/), Grants 201306300064, 201603250057, and 201406210064, respectively. The authors thank Ron Fouchier (Erasmus Medical Center, The Netherlands) for generously providing recombinant influenza viruses WU95 and VI75.

Glossary

Abbreviations Used

- CCR2

CC chemokine receptor 2

- CCL2

CC chemokine ligand 2

- CCR5

CC chemokine receptor 5

- TLC

thin layer chromatography

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b00303.

Author Present Address

§ W.L.: Shaanxi Institute of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Shaanxi, China.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Palese P. Influenza: Old and New Threats. Nat. Med. 2004, 10, S82–S87. 10.1038/nm1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richard M.; Fouchier R. A. M. Influenza A Virus Transmission via Respiratory Aerosols or Droplets as It Relates to Pandemic Potential. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2016, 40, 68–85. 10.1093/femsre/fuv039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton B. S.; Whittaker G. R.; Daniel S. Influenza Virus-Mediated Membrane Fusion: Determinants of Hemagglutinin Fusogenic Activity and Experimental Approaches for Assessing Virus Fusion. Viruses 2012, 4, 1144–1168. 10.3390/v4071144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo H.; Rabouw H.; Slomp A.; Dai M.; van der Vegt F.; van Lent J. W. M.; McBride R.; Paulson J. C.; de Groot R. J.; van Kuppeveld F. J. M.; de Vries E.; de Haan C. A. M. Kinetic Analysis of the Influenza A Virus HA/NA Balance Reveals Contribution OfNA to Virus-Receptor Binding and NA-Dependent Rolling on Receptor-Containing Surfaces. PLoS Pathog. 2018, 14, e1007233 10.1371/journal.ppat.1007233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Graaf M.; Fouchier R. A. Role of Receptor Binding Specificity in Influenza A Virus Transmission and Pathogenesis. EMBO J. 2014, 33, 823–841. 10.1002/embj.201387442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji Y.; White Y. J.; Hadden J. A.; Grant O. C.; Woods R. J. New Insights into Influenza A Specificity: An Evolution of Paradigms. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2017, 44, 219–231. 10.1016/j.sbi.2017.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skalickova S.; Heger Z.; Krejcova L.; Pekarik V.; Bastl K.; Janda J.; Kostolansky F.; Vareckova E.; Zitka O.; Adam V.; Kizek R. Perspective of Use of Antiviral Peptides against Influenza Virus. Viruses 2015, 7, 5428–5442. 10.3390/v7102883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Itzstein M. The War against Influenza: Discovery and Development of Sialidase Inhibitors. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2007, 6, 967–974. 10.1038/nrd2400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moscona A. Oseltamivir Resistance — Disabling Our Influenza Defenses. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005, 353, 2633–2636. 10.1056/NEJMp058291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst B.; Magnani J. L. From Carbohydrate Leads to Glycomimetic Drugs. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2009, 8, 661–677. 10.1038/nrd2852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauter N. K.; Bednarski M. D.; Wurzburg B. A.; Hanson J. E.; Whitesides G. M.; Skehel J. J.; Wiley D. C. Hemagglutinins from Two Influenza Virus Variants Bind to Sialic Acid Derivatives with Millimolar Dissociation Constants: A 500-MHz Proton Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Study. Biochemistry 1989, 28, 8388–8396. 10.1021/bi00447a018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandlow V.; Liese S.; Lauster D.; Ludwig K.; Netz R. R.; Herrmann A.; Seitz O. Spatial Screening of Hemagglutinin on Influenza A Virus Particles: Sialyl-LacNAc Displays on DNA and PEG Scaffolds Reveal the Requirements for Bivalency Enhanced Interactions with Weak Monovalent Binders. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 16389–16397. 10.1021/jacs.7b09967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor R. J.; Kawaoka Y.; Webster R. G.; Paulson J. C. Receptor Specificity in Human, Avian, and Equine H2 and H3 Influenza Virus Isolates. Virology 1994, 205, 17–23. 10.1006/viro.1994.1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadam R. U.; Wilson I. A. A Small-Molecule Fragment That Emulates Binding of Receptor and Broadly Neutralizing Antibodies to Influenza A Hemagglutinin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2018, 115, 4240–4245. 10.1073/pnas.1801999115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mammen M.; Choi S. K.; Whitesides G. M. Polyvalent Interactions in Biological Systems: Implications for Design and Use of Multivalent Ligands and Inhibitors. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1998, 37, 2754–2794. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng W.; de Vries R. P.; Grant O. C.; Thompson A. J.; McBride R.; Tsogtbaatar B.; Lee P. S.; Razi N.; Wilson I. A.; Woods R. J.; Paulson J. C. Recent H3N2 Viruses Have Evolved Specificity for Extended, Branched Human-Type Receptors, Conferring Potential for Increased Avidity. Cell Host Microbe 2017, 21, 23–34. 10.1016/j.chom.2016.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cecioni S.; Imberty A.; Vidal S. Glycomimetics versus Multivalent Glycoconjugates for the Design of High Affinity Lectin Ligands. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 525–561. 10.1021/cr500303t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parera Pera N. P.; Branderhorst H. M.; Kooij R.; Maierhofer C.; van der Kaaden M.; Liskamp R. M. J.; Wittmann V.; Ruijtenbeek R.; Pieters R. J. Rapid Screening of Lectins for Multivalency Effects with a Glycodendrimer Microarray. ChemBioChem 2010, 11, 1896–1904. 10.1002/cbic.201000340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittmann V.; Pieters R. J. Bridging Lectin Binding Sites by Multivalent Carbohydrates. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 4492–4503. 10.1039/c3cs60089k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernardi A.; Jimenez-Barbero J.; Casnati A.; De Castro C. De; Darbre T.; Fieschi F.; Finne J.; Funken H.; Jaeger K.-E.-E.; Lahmann M.; Lindhorst T. K.; Marradi M.; Messner P.; Molinaro A.; Murphy P. V.; Nativi C.; Oscarson S.; Penades S.; Peri F.; et al. Multivalent Glycoconjugates as Anti-Pathogenic Agents. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 4709–4727. 10.1039/C2CS35408J. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiessling L. L.; Gestwicki J. E.; Strong L. E. Synthetic Multivalent Ligands as Probes of Signal Transduction. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2006, 45, 2348–2368. 10.1002/anie.200502794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieters R. J. Maximising Multivalency Effects in Protein-Carbohydrate Interactions. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2009, 7, 2013–2025. 10.1039/b901828j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu W.; Pieters R. J. Carbohydrate–Protein Interactions and Multivalency: Implications for the Inhibition of Influenza A Virus Infections. Expert Opin. Drug Discovery 2019, 14, 387–395. 10.1080/17460441.2019.1573813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matrosovich M. N.; Mochalova L. V.; Marinina V. P.; Byramova N. E.; Bovin N. V. Synthetic Polymeric Inhibitors of Influenza Virus Receptor-Binding Activity Suppress Virus Replication. FEBS Lett. 1990, 272, 209–221. 10.1016/0014-5793(90)80486-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lees W. J.; Spaltenstein A.; Kingery-Wood J. E.; Whitesides G. M. Polyacrylamides Bearing Pendant A-Sialoside Groups Strongly Inhibit Agglutination of Erythrocytes by Influenza A Virus: Multivalency and Steric Stabilization of Particulate Biological Systems. J. Med. Chem. 1994, 37, 3419–3433. 10.1021/jm00046a027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi S. K.; Mammen M.; Whitesides G. M. Generation and in Situ Evaluation of Libraries of Poly(Acrylic Acid) Presenting Sialosides as Side Chains as Polyvalent Inhibitors of Influenza- Mediated Hemagglutination. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997, 119, 4103–4111. 10.1021/ja963519x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kamitakahara H.; Suzuki T.; Nishigori N.; Suzuki Y.; Kanie O.; Wong C.-H. A Lysoganglioside/Poly-l-Glutamic Acid. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1998, 37, 1524–1528. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papp I.; Sieben C.; Sisson A. L.; Kostka J.; Böttcher C.; Ludwig K.; Herrmann A.; Haag R. Inhibition of Influenza Virus Activity by Multivalent Glycoarchitectures with Matched Sizes. ChemBioChem 2011, 12, 887–895. 10.1002/cbic.201000776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia S.; Lauster D.; Bardua M.; Ludwig K.; Angioletti-Uberti S.; Popp N.; Hoffmann U.; Paulus F.; Budt M.; Stadtmüller M.; Wolff T.; Hamann A.; Böttcher C.; Herrmann A.; Haag R. Linear Polysialoside Outperforms Dendritic Analogs for Inhibition of Influenza Virus Infection in Vitro and in Vivo. Biomaterials 2017, 138, 22–34. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2017.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X.; Wu P.; Gao G. F.; Cheng S. Carbohydrate-Functionalized Chitosan Fiber for Influenza Virus Capture. Biomacromolecules 2011, 12, 3962–3969. 10.1021/bm200970x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh H. W.; Lin T. S.; Wang H. W.; Cheng H. W.; Liu D. Z.; Liang P. H. S-Linked Sialyloligosaccharides Bearing Liposomes and Micelles as Influenza Virus Inhibitors. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2015, 13, 11518–11528. 10.1039/C5OB01376C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glick G. D.; Knowles J. R. Molecular Recognition of Bivalent Sialosides by Influenza Virus. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991, 113, 4701–4703. 10.1021/ja00012a060. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Glick G. D.; Toogood P. L.; Wiley D. C.; Skehel J. J.; Knowles J. R. Ligand Recognition by Influenza Virus. J. Biol. Chem. 1991, 266, 23660–23669. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabesan S.; Duus J. O.; Domaille P.; Kelm S.; Paulson J. C. Synthesis of Cluster Sialoside Inhibitors for Influenza Virus. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991, 113, 5865–5866. 10.1021/ja00015a052. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roy R.; Zanini D.; Meunier S. J.; Romanowska A. Solid-Phase Synthesis of Dendritic Sialoside Inhibitors of Influenza a Virus Hemagglutin. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1993, 1869–1872. 10.1039/c39930001869. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ohta T.; Miura N.; Fujitani N.; Nakajima F.; Niikura K.; Sadamoto R.; Guo C. T.; Suzuki T.; Suzuki Y.; Monde K.; Nishimura S. I. Glycotentacles: Synthesis of Cyclic Glycopeptides, toward a Tailored Blocker of Influenza Virus Hemagglutinin. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2003, 42, 5186–5189. 10.1002/anie.200351640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marra A.; Moni L.; Pazzi D.; Corallini A.; Bridi D.; Dondoni A. Synthesis of Sialoclusters Appended to Calix[4]Arene Platforms via Multiple Azide-Alkyne Cycloaddition. New Inhibitors of Hemagglutination and Cytopathic Effect Mediated by BK and Influenza A Viruses. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2008, 6, 1396–1409. 10.1039/b800598b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldmann M.; Jirmann R.; Hoelscher K.; Wienke M.; Niemeyer F. C.; Rehders D.; Meyer B. A Nanomolar Multivalent Ligand as Entry Inhibitor of the Hemagglutinin of Avian Influenza. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 783–788. 10.1021/ja410918a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamabe M.; Kaihatsu K.; Ebara Y. Sialyllactose-Modified Three-Way Junction DNA as Binding Inhibitor of Influenza Virus Hemagglutinin. Bioconjugate Chem. 2018, 29, 1490–1494. 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.8b00045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieters R. J.; Cuntze J.; Bonnet M.; Diederich F. Enantioselective Recognition with C-3-Symmetric Cage-like Receptors in Solution and on a Stationary Phase. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 2 1997, 1891–1900. 10.1039/a702627g. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pertici F.; De Mol N. J.; Kemmink J.; Pieters R. J. Optimizing Divalent Inhibitors of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Lectin LecA by Using a Rigid Spacer. Chem.—Eur. J. 2013, 19, 16923–16927. 10.1002/chem.201303463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu G.; Vicini A. C.; Pieters R. J. Assembling of Divalent Ligands and Their Effect on Divalent Binding to Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Lectin LecA. J. Org. Chem. 2019, 84, 2470–2488. 10.1021/acs.joc.8b02727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visini R.; Jin X.; Bergmann M.; Michaud G.; Pertici F.; Fu O.; Pukin A.; Branson T. R.; Thies-Weesie D. M. E.; Kemmink J.; Gillon E.; Imberty A.; Stocker A.; Darbre T.; Pieters R. J.; Reymond J.-L. Structural Insight into Multivalent Galactoside Binding to Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Lectin LecA. ACS Chem. Biol. 2015, 10, 2455–2462. 10.1021/acschembio.5b00302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haksar D.; de Poel E.; van Ufford L. Q.; Bhatia S.; Haag R.; Beekman J. M.; Pieters R. J. Strong Inhibition of Cholera Toxin B Subunit by Affordable, Polymer-Based Multivalent Inhibitors. Bioconjugate Chem. 2019, 30, 785–792. 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.8b00902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McArthur J. B.; Yu H.; Zeng J.; Chen X. Converting Pasteurella Multocida Α2-3-Sialyltransferase 1 (PmST1) to a Regioselective Α2-6-Sialyltransferase by Saturation Mutagenesis and Regioselective Screening. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2017, 15, 1700–1709. 10.1039/C6OB02702D. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong X.; Xiao H.; Martin S. R.; Coombs P. J.; Liu J.; Collins P. J.; Vachieri S. G.; Walker P. A.; Lin Y. P.; McCauley J. W.; Gamblin S. J.; Skehel J. J. Enhanced Human Receptor Binding by H5 Haemagglutinins. Virology 2014, 456–457, 179–187. 10.1016/j.virol.2014.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liese S.; Netz R. R. Influence of Length and Flexibility of Spacers on the Binding Affinity of Divalent Ligands. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2015, 11, 804–816. 10.3762/bjoc.11.90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemanichvili N.; Tomris I.; Turner H. L.; McBride R.; Grant O. C.; van der Woude R.; Aldosari M. H.; Pieters R. J.; Woods R. J.; Paulson J. C.; Boons G.-J.; Ward A. B.; Verheije M. H.; de Vries R. P. Fluorescent Trimeric Hemagglutinins Reveal Multivalent Receptor Binding Properties. J. Mol. Biol. 2019, 431, 842–856. 10.1016/j.jmb.2018.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kale R. R.; Mukundan H.; Price D. N.; Harris J. F.; Lewallen D. M.; Swanson B. I.; Schmidt J. G.; Iyer S. S. Detection of Intact Influenza Viruses Using Biotinylated Biantennary S-Sialosides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 8169–8171. 10.1021/ja800842v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spjut S.; Qian W.; Bauer J.; Storm R.; Frängsmyr L.; Stehle T.; Arnberg N.; Elofsson M. A Potent Trivalent Sialic Acid Inhibitor of Adenovirus Type 37 Infection of Human Corneal Cells. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 6519–6521. 10.1002/anie.201101559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pahimanolis N.; Vesterinen A.-H.; Rich J.; Seppala J. Modification of Dextran Using Click-Chemistry Approach in Aqueous Media. Carbohydr. Polym. 2010, 82, 78–82. 10.1016/j.carbpol.2010.04.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moni L.; Ciogli A.; D’Acquarica I.; Dondoni A.; Gasparrini F.; Marra A. Synthesis of Sugar-Based Silica Gels by Copper-Catalysed Azide-Alkyne Cycloaddition via a Single-Step Azido-Activated Silica Intermediate and the Use of the Gels in Hydrophilic Interaction Chromatography. Chem. - Eur. J. 2010, 16, 5712–5722. 10.1002/chem.201000106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.