Abstract

Growing evidence indicates that elongation factor 1α (EF1α) is involved in responses to various abiotic stresses in several plant species. Soybean EF1α proteins include three structural domains: one GTP-binding domain and two oligonucleotide binding domains that are also called as domain 2 and domain 3. In this study, 10 EF1α genes were identified in the soybean genome. We predicted structures of different domains and analyzed gene locations, gene structures, phylogenetic relationships, various cis-elements, and conserved domains of soybean EF1αs. The expression patterns of 10 EF1α genes were analyzed by quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR). Under drought stress, soybean EF1α genes were upregulated in varying degrees. In particular, GmEF4 was upregulated under drought and salt treatments. Compared to the drought- and salt-treated empty vector (EV)-control plants, drought- and salt-treated GmEF4-overexpressing (OE) plants had significantly delayed leaf wilting, longer root, higher biomass, higher proline (Pro) content, and lower H2O2, O2−, and malondialdehyde (MDA) contents. Thus, this study provides a foundation for further functional genomics research about this important family under abiotic stress.

Keywords: EF1αs, genome-wide analysis, drought tolerance, salt tolerance, hairy root assay, soybean

1. Introduction

Transcript elongation factors (EFs) mediate various growth processes, including the regulation, proliferation, and differentiation of cells [1]. In eukaryotes, EF1 includes α, β, γ, and δ subunits. The α-subunit (EF1α) is considered to be one of the most abundant soluble proteins in cell cytoplasm, where it constitutes up to 3%–10% of the total soluble protein content [2].

It is reported that EF1α plays an essential role in protein biosynthesis and proteolysis. EF1α can carry aminoacyl-tRNAs to the binding sites of ribosomes in protein synthesis. Archaeal EF1α, as a carrier GTPase protein, transfers both aRF1 and aPelota to the ribosome. Archaeal EF1α is associated with aRF1/aPelota, which confirms the absence of specific GTPases for aRF1 and aPelota in archaeal species [3]. In the anabolic metabolism process, protein synthesis was activated by the association between EF1α and AA·tRNA/GTP, but is inactive in proteolysis. By contrast, with the catabolic metabolism process, EF primarily exists as the hydrolyzed form, so EF1α is required for ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis [4].

Several EF1α members were reported to be involved in responses to abiotic stresses in plants. Several reports proposed that the expression of EF1α is related to cold stress in barley and maize [5,6]. Growing evidence indicates that EF1α expression in various plant species changes in response to different stressors, including high and low temperatures, salinity, water deficits, and pollutants [7]. Thus, these results established that EF1α genes may play an important role in the regulation of translation during abiotic stresses.

Soybean is an important economic crop, especially for Chinese. Limited water resources have become one of the main restrictive factors for soybean cultivation and production in China. A previous study has shown that Glomus mosseae can improve the drought resistance of soybean [8]. Increasing soybean yield can also be achieved by selecting and cultivating soybean genotypes with higher stem strength [9]. Although several EF1α genes have been well characterized in several plant species, their roles under abiotic stress are still unclear and need further research. In this study, we identified 10 genes of soybean EF1α members and analyzed the chromosome localization, conserved domains, phylogenetic relationships, and expression patterns of GmEF1αs. We also conducted an in-depth survey of the expression patterns of GmEF1αs in responses to abiotic stress and exogenous hormones. Among them, GmEF4 was upregulated under drought and salt treatments. Compared with control plants, GmEF4-overexpressing plants exhibited drought and salt tolerant phenotypes. Our results provide a foundation for further research on the EF1α family in response to abiotic stresses.

2. Results

2.1. Identification, Physical Locations, and Conserved Domains of Soybean EF1αs

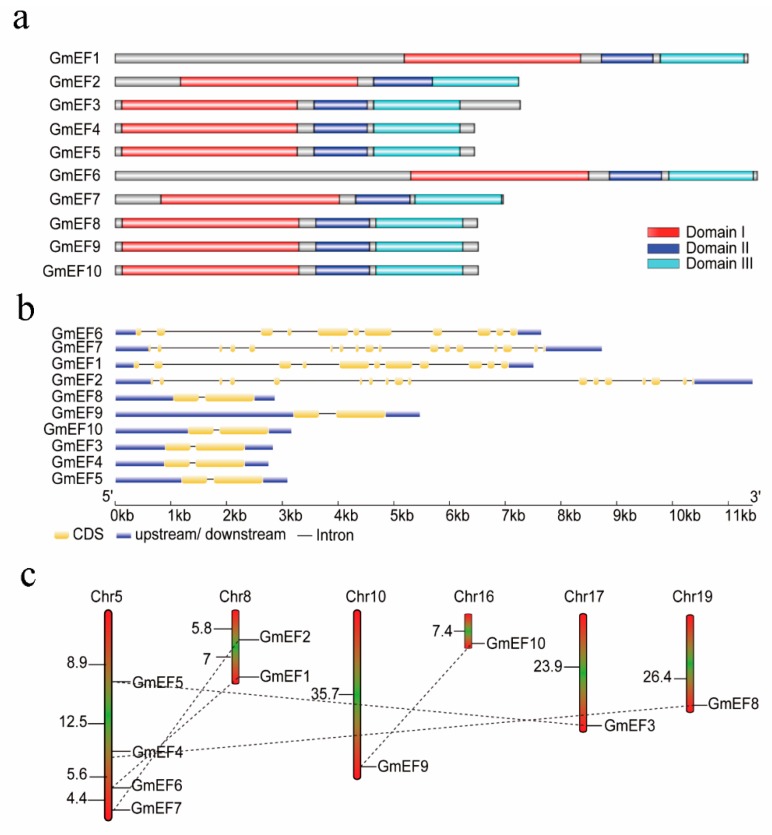

The Phytozome database and the SMART program were used as references for the identification of 10 soybean EF1α genes (Table 1). The numbers of amino acids in soybean EF1αs varied widely, ranging from 447 to 792. The predicted isoelectric points (pI) of the proteins were diverse, from 4.89 to 9.59 (Table 1). All 10 of the nonredundant GmEF1αs contained three conserved domains: the GTP-binding domain (known as domain I), and two oligonucleotide binding domains (often referred to as domain II and domain III) (TAIR) (Figure 1a). Domain I is important for GDP/GTP binding and GTPase activity. Domain II is responsible for aminoacyl tRNA binding. Domain III is the C-terminal domain.

Table 1.

Details of the 10 soybean elongation factor 1α (EF1α) proteins, including sequence ID, protein sequence length, predicted molecular weight (MW), predicted isoelectric point (pI), chromosomal location, and predicted functional domains.

| Gene | Gene ID | Amino Acids | MW (Da) | pI | Chromosome | Domain I | Domain II | Domain III |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GmEF1 | Glyma08g12790 | 787 | 85,982.9 | 6.43 | 8 | 360–579 | 605–669 | 678–782 |

| GmEF2 | Glyma08g05570 | 504 | 56,282.4 | 4.89 | 8 | 82–302 | 322–389 | 395–502 |

| GmEF3 | Glyma17g23900 | 447 | 49,387.0 | 9.56 | 17 | 9–227 | 248–314 | 322–429 |

| GmEF4 | Glyma05g24110 | 447 | 49,254.9 | 9.58 | 5 | 9–227 | 248–314 | 322–429 |

| GmEF5 | Glyma05g11630 | 447 | 49,347.0 | 9.56 | 5 | 9–227 | 248–314 | 322–429 |

| GmEF6 | Glyma05g29675 | 792 | 86,366.4 | 6.9 | 5 | 365–584 | 610–674 | 683–787 |

| GmEF7 | Glyma05g34120 | 479 | 53,359.7 | 5.16 | 5 | 57–277 | 297–364 | 370–477 |

| GmEF8 | Glyma19g07240 | 447 | 49,270.9 | 9.58 | 19 | 9–227 | 248–314 | 322–429 |

| GmEF9 | Glyma10g35700 | 448 | 49,491.1 | 9.59 | 10 | 9–227 | 248–314 | 322–429 |

| GmEF10 | Glyma16g07350 | 447 | 49,397.1 | 9.56 | 16 | 9–227 | 248–314 | 322–429 |

Figure 1.

Bioinformatic analysis of GmEF1α proteins and GmEF1α genes. (a) Structures of EF1α proteins in soybean. (b) Intron–exon structures of EF1α genes in soybean. (c) Locations and duplications of GmEF1α genes in the soybean genome. Paralogous genes are connected by lines.

These genes are distributed on six chromosomes (5, 8, 10, 16, 17, and 19). However, the number of soybean EF1α genes on each chromosome was significantly varied. For example, chromosome 5 and 8 carry four and two EF1α genes, respectively. Each of chromosomes 10, 16, 17, and 19 carries one EF1α gene (Table 1). Using soybean genome repeat area information, five paralogous gene pairs were identified, including GmEF1/6, GmEF2/7, GmEF3/5, GmEF4/8, and GmEF9/10 (Figure 1c).

Nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequences were obtained from Phytozome v9.1 (http://www.phytozome.com/). Gene, CDS, and amino acid identities were determined in this study based on nucleotide or amino acid alignments of the 10 genes using Clustal X 2.0.

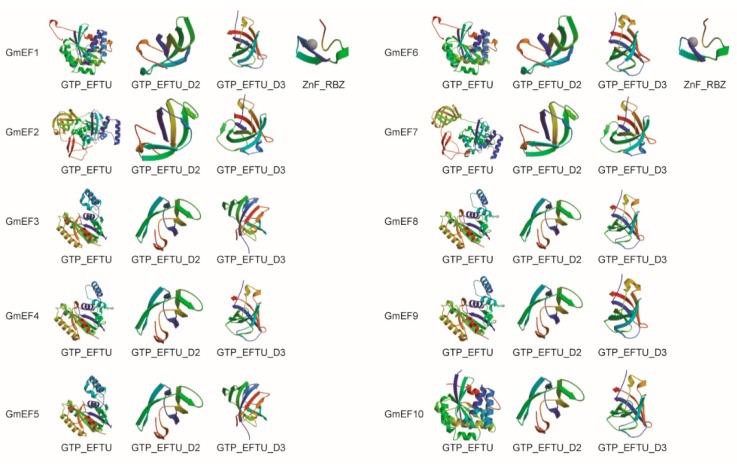

2.2. The Predicted Structures of Domains in Soybean EF1αs

Soybean EF1αs proteins consist of domain 1, domain 2, and domain 3 (Figure 2). All EF-Tu domains include α-helices and β-strands to complex with tRNA and GTP. In particular, GmEF1 and GmEF6 all have the zinc finger domain to make tandem contacts with their target molecule. Domain 2 and domain 3 adopt β-barrel structures, and are involved in binding to charged tRNA and to EF-Tus.

Figure 2.

The predicted structures of domains in soybean EF1αs. The predicted structures of soybean EF1αs proteins were analyzed by SMART (http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de/) and were drawn online (https://swissmodel.expasy.org/).

2.3. Phylogenetic and Gene Structural Analysis

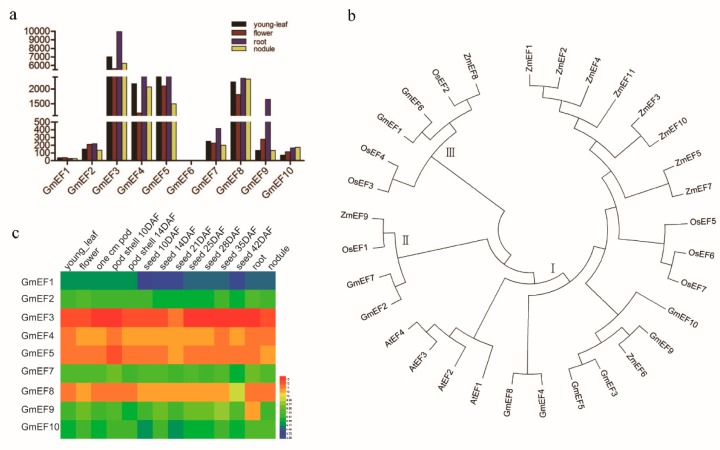

To determine the phylogenetic relationships among the soybean EF1αs, a phylogenetic analysis of 10 soybean GmEF1αs, 7 rice OsEF1αs, 11 maize ZmEF1αs, and 4 Arabidopsis AtEF1αs was performed by generating a neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree (Figure 3b). The EF1αs were grouped into three clusters. Each cluster is conserved and produces similar proteins. In cluster I, the GmEF8 protein differs from GmEF4 by two amino acids, whereas the GmEF3, GmEF5, GmEF9, and GmEF10 proteins respectively share 96.2%, 96.6%, 97.3%, and 97.5% identity with the GmEF8 protein (Figure 3b and Table 1).

Figure 3.

Differential expression analyses of soybean EF1α family members, neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree of EF1α members from Glycine max (Gm), Arabidopsis (At), Zea mays (Zm), and Oryza sativa (Os), and subcellular localization of GmEF4. (a) Expression data were extracted from soybean transcriptome data in SoyBase. In this respect, a transcriptionally active gene is a gene that has two or more sequence reads at one or more of the tested tissues/developmental stages. (b) Multiple sequence alignment was performed using the Clustal X program, and the phylogenetic tree was constructed using the neighbor-joining method. AtEF1 (AT1G07920), AtEF2 (AT1G07930), AtEF3 (AT1G07940), AtEF8 (AT5G60390), OsEF1 (Os04g20220), OsEF2 (Os04g58140), OsEF3 (Os04g50870), OsEF8 (Os01g02720), OsEF5 (Os03g08010), OsEF6 (Os03g08020), OsEF7 (Os03g08050), ZmEF1 (GRMZM2G149768), ZmEF2 (GRMZM2G001327), ZmEF3 (AC233866), ZmEF8 (GRMZM2G154218), ZmEF5 (GRMZM2G343543), ZmEF6 (GRMZM2G057535), ZmEF7 (GRMZM2G153541), ZmEF8 (GRMZM2G084252), ZmEF9 (GRMZM2G028313), ZmEF10 (GRMZM2G151193), and ZmEF11 (GRMZM2G110509). (c) An analysis was performed by the Affymetrix soybean gene chip downloaded in SoyBase (https://www.soybase.org/soyseq/), which included the 10 soybean EF1αs in the different tissues and development stages. The heatmap was drawn using the software HemI.

In recent years, research on introns has made significant progress. Studies in mammals, nematodes, insects, fungi, and plants have shown that introns not only regulate gene expression but that they are also involved in gene evolution [10]. Analysis of the gene structure showed that clusters I, II, and III were characterized by 1, 16, and 10 introns, respectively. The intron numbers and intron positions of EF1αs in the same cluster were conserved even though several introns of the same corresponding locations exhibited variable lengths (Figure 1b). This suggests that the intron numbers were established in each cluster before the eudicots and monocots diverged.

2.4. Expression Patterns of Soybean EF1αs

To examine the gene expression of the 10 soybean EF1α in different tissues and organs, an expression pattern map was constructed from gene chip data that were downloaded from the soybean genome database and the expression pattern heatmap of the soybean EF1α genes was drawn (Figure 3c and Table S1). The heatmap showed that GmEF3 was highly expressed in all tissues and organs, while GmEF6 was hardly expressed in any tissues and organs and GmEF1 was only weakly expressed in the young leaves, flower, and pod in soybean.

The data analysis of four tissues and organs revealed that all GmEF1α members, except GmEF6, were expressed in the roots, young leaves, nodules, and flowers. Moreover, the expression quantity was similar in the same clusters of EF1α genes. The highest level of EF1α expression was found in cluster I, and included GmEF3, GmEF4, GmEF5, and GmEF8 (Figure 3a). However, GmEF1 in cluster III showed low levels of expression, and no expression was detected for its paralogous gene, GmEF6, perhaps because of weak promoter activity. Unlike other GmEF1αs, the transcription of GmEF9 occurred primarily in root with 5- and 12-fold stronger expression levels in root than in young leaves and flowers, suggesting that the GmEF9 promoter may contain root specific cis-elements (Figure 3a).

2.5. Soybean EF1αs Contain Various cis-Elements

The analysis of cis-elements in the promoters indicated that each soybean EF1α gene, with one exception, carried more than four MYB and MYC elements, which are known to be involved in responses to abiotic stresses [11]. The exception was GmEF10, which carried no MYC but had 8 MYB elements. All of these genes contained abscisic acid (ABA)-responsive elements (ABREs), strongly suggesting that these genes may respond to drought and ABA via combination with an ABRE binding protein (AREB) [12]. GmEF4 contains sixteen MYC elements, which is the highest number observed in the GmEF1α family. In addition, three EF1αs contain dehydration-responsive elements (DREs) (Table 2). The presence of diverse abiotic stress-responsive elements in the promoters of GmEF1αs indicates involvement of these genes in abiotic stress responses. In fact, any abiotic stresses, if sufficiently intense, will result in a non-native conformation (denaturation) of proteins [13]. Thus, members of the GmEF1α family may be required to facilitate the recovery of denatured proteins.

Table 2.

Distribution and numbers of cis-acting elements in soybean EF1α genes.

| Genes | GmEF1 | GmEF2 | GmEF3 | GmEF4 | GmEF5 | GmEF6 | GmEF7 | GmEF8 | GmEF9 | GmEF10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABRE | 1 | 1 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 8 | 6 | 1 |

| DRE | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| LTRE | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| MYB | 13 | 11 | 16 | 7 | 9 | 5 | 16 | 10 | 13 | 8 |

| MYC | 16 | 11 | 10 | 16 | 12 | 4 | 12 | 10 | 10 | 0 |

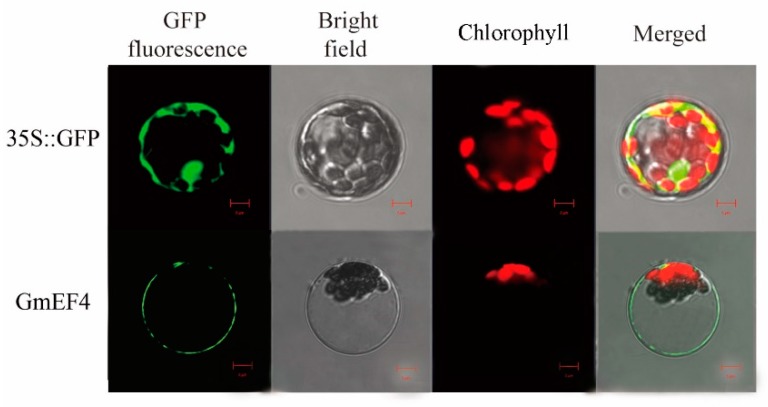

2.6. GmEF4 Localized in Cell Membranes

For subcellular localization analysis, the GmEF4 cDNA sequence was fused to the N-terminus of the GFP reporter gene and was inserted into the expression vector under the control of the double CaMV 35S promoter. The construct was transferred into Arabidopsis protoplasts and the subcellular localization of GFP expression was observed. We found that the GmEF4-GFP fusion protein was mainly localized in cell membrane, whereas the control GFP was localized uniformly throughout the Arabidopsis cells (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Localization of GmEF4 protein in Arabidopsis protoplasts. The construct was transferred into Arabidopsis protoplasts and the subcellular localization of the GFP expression was observed in cell membrane. Images were observed under a laser scanning confocal microscope. Bar = 5 μm.

2.7. Responses of Soybean EF1αs to Drought, Salt, and ABA Stresses

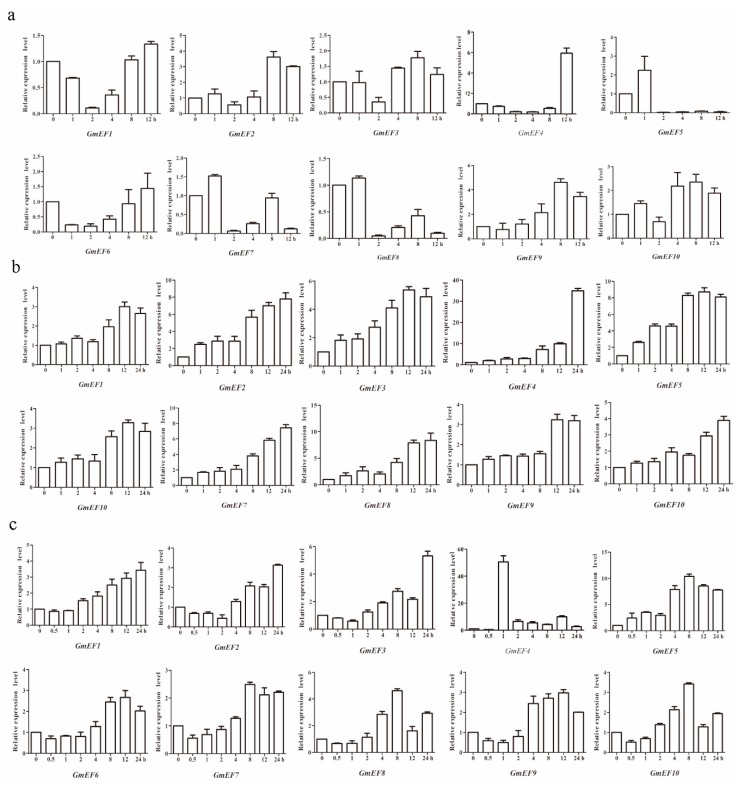

To further confirm the drought and salt stress response, the transcription of EF1α genes was investigated by quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) using soybean seedlings exposed to drought and salt treatments (Figure 5). Based on these results, soybean EF1α genes were expressed differently under drought stress (Figure 5a). Among 10 soybean EF1α members, GmEF4 reached the highest level under drought treatment at 12 h (>5.5-fold). GmEF9 was upregulated under drought stress and showed highest levels at 8 h (>4-fold), GmEF2, GmEF10, and GmEF3 showed highest levels at 8 h (>3-fold, >2-fold and >1.5-fold). GmEF1 and GmEF6 transcriptions were induced by drought and reached a maximum at 12 h (>1-fold). The transcriptions of GmEF5, GmEF7, and GmEF8 were induced by drought; the peak at 1 h was followed by a sharp decrease over the next few hours.

Figure 5.

Expression patterns of soybean EF1αs under drought stress, salt stress, and abscisic acid (ABA) treatment. (a) Expression levels of the 10 soybean EF1α genes under drought stress, as measured using qRT-PCR. Drought treatment was applied for 0, 1, 2, 4, 8, and 12 h. (b) Expression levels of 10 soybean EF1α genes under NaCl treatment for 0, 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, and 24 h. (c) Expression levels of the 10 soybean EF1α genes under ABA treatment, as measured using qRT-PCR. ABA treatment was applied for 0, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, and 24 h. The vertical coordinates are fold changes, and the horizontal ordinates are treatment times. The actin gene was used as an internal reference. The data are shown as means of three biology repeats ± SD.

In addition, soybean EF1α genes were all upregulated by salt stress (Figure 5b). GmEF1, GmEF3, GmEF5, GmEF6, and GmEF9 transcription were induced by salinity; peaking at 12 h (>2.5-fold, >5-fold, >8-fold, >3-fold, and >3-fold, respectively) was followed by an observed decrease at 24 h. GmEF2, GmEF7, GmEF8, and GmEF10 transcription were induced by salinity along with time, and increased to their highest level at 24 h (>7-fold, >7-fold, >8-fold, and >3.5-fold, respectively). In particular, GmEF4 reached the highest level under salt treatment at 24 h (>30-fold).

The transcription of EF1α genes was also investigated by qRT-PCR using soybean seedlings exposed to abscisic acid (ABA) (0, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, and 24 h) treatment (Figure 5). Based on these results, the transcription of all of soybean EF1α genes were induced by ABA and were increased to different degrees (Figure 5c). The expressions of GmEF5, GmEF7, GmEF8, and GmEF10 reached the highest levels at 8 h (>10-fold, >2-fold, >4-fold, and >3-fold, respectively), while the transcript levels of GmEF1, GmEF2, and GmEF3 reached their maximums at 24 h (>3-fold, >3-fold, and >5-fold, respectively). The transcription of GmEF6 and GmEF9 reached a maximum at 12 h (both >2.5-fold). Among 10 soybean EF1α members, GmEF4 reached the highest level under ABA treatment at 1 h (>50-fold). Hence, it may be play important role in the response to drought, salt, and ABA stress.

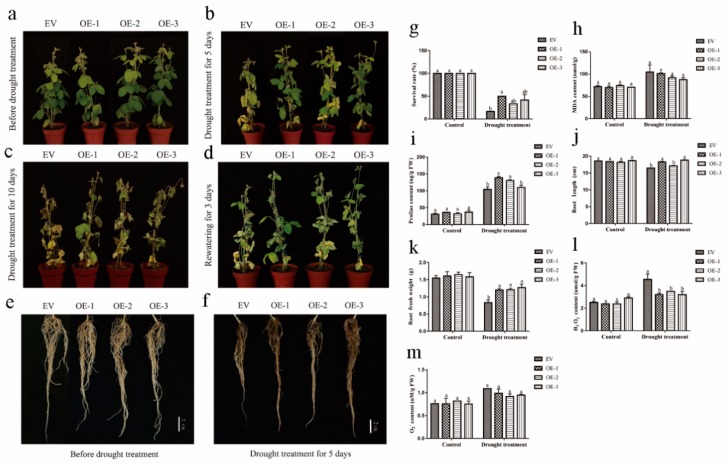

2.8. Overexpression of GmEF4 Significantly Improved Drought Tolerance in Soybean Hairy Roots

To further investigate the biological function of GmEF4 in drought response, we used Agrobacterium rhizogenes-mediated transformation of soybean hairy roots to generate soybean hairy roots overexpressing GmEF4 (GmEF4-OE). qRT-PCR analysis showed that, compared to the empty vector (EV)-transformed control hairy roots, the roots with the overexpression construct had significantly increased GmEF4 expression (Figure S1). We found that, whereas no significant differences were observed between the EV-control and the GmEF4-OE plants under normal growth conditions (Figure 6a), drought treatment caused obvious differences in the growth and physiology of the EV-control and the GmEF4-OE plants (Figure 6b,c). Compared with the EV-control, GmEF4-OE plants appeared wilted leaf under drought treatment for 5 days. The water loss of EV-control and GmEF4-OE plants are severe under drought treatment for 10 days. In addition, the leaves of GmEF4-OE plants recover phenotype compared to the EV-control plants after rewatering for 3 days (Figure 6d). We found that whereas no significant differences were observed between the EV-control and the GmEF4-OE roots under normal growth conditions (Figure 6e), but compared to the drought-treated EV-control roots, drought-treated GmEF4-OE roots were longer (Figure 6f). Drought stress can lead to the accumulation of peroxides. By measuring the contents of H2O2 and O2−, we found that the drought-treated GmEF4-OE roots have lower H2O2 content and lower O2− content (Figure 6l,m). Drought stress can also lead to the accumulation of proline. By measuring the content of Pro, we found that the content of Pro in the GmEF4-OE was significantly higher than that of the EV-control under drought treatment (Figure 6i). The drought-treated GmEF4-OE plants have higher survival rate and lower MDA content (Figure 6g,h). The drought-treated GmEF4-OE roots have higher biomass and were longer (Figure 6j,k).

Figure 6.

Phenotypic analysis of GmEF4-overexpressing (GmEF4-OE) and empty vector (EV)-control plants under drought treatment. (a) and (b,c) Phenotypes of GmEF4-OE and EV-control transgenic soybean plants under normal and drought conditions. (d) Phenotypes of GmEF4-OE and EV-control transgenic soybean plants under rewatering conditions. (e) and (f) Phenotypes of GmEF4-OE and EV-control hairy roots under normal and drought conditions. (g) Survival of normal and drought-stressed plants. (h) Malondialdehyde (MDA) content and (i) proline content of GmEF4-OE and EV-control plants grown with drought treatment. (j) the root length, (k) total fresh weight, (l) H2O2 content, and (m) O2− content of GmEF4-OE and EV-control soybean hairy roots grown with drought treatment. The different letters in the bar graphs indicate significant differences at p < 0.05 between GmEF4-OE and EV-control transgenic soybean.

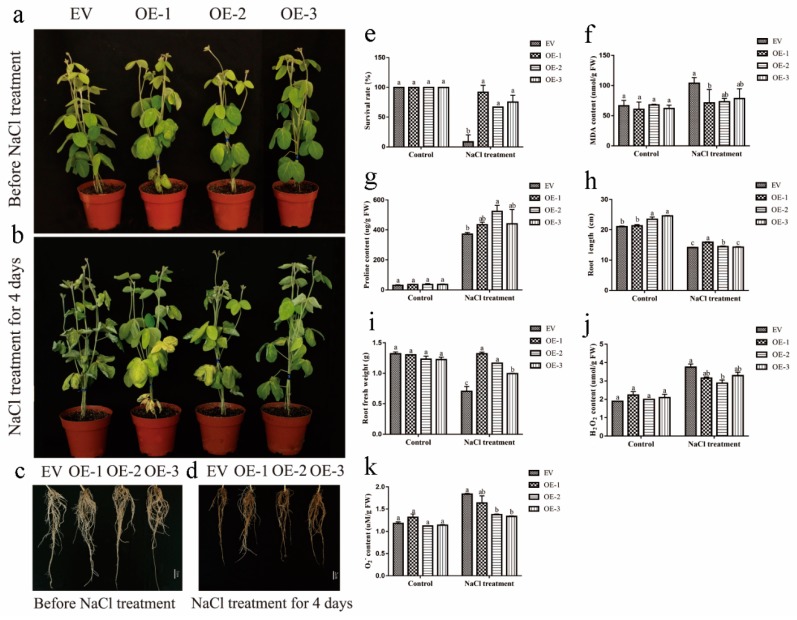

2.9. Overexpression of GmEF4 Significantly Improved Salt Tolerance in Soybean Hairy Roots

To further investigate the roles of GmEF4 in salt response, we used the same methods to generate GmEF4-OE plants. No significant differences were observed between the EV-control and the GmEF4-OE plants under normal growth conditions (Figure 7a). However, obvious differences in the growth and physiology of the EV-control and the GmEF4-OE plants appeared under salt treatment for 4 days (Figure 7b). The GmEF4-OE plants have higher biomass than EV-control plants and with fewer wilting of leaves than EV-control plants. Specifically, compared to the EV-control plants, salt-treated GmEF4-OE plants have longer roots (Figure 7c,d). The salt-treated GmEF4-OE plants have a higher survival rate, lower MDA content, and higher proline content (Figure 7e–g). The salt-treated GmEF4-OE roots have higher biomass and longer roots (Figure 7h,i). Salt stress can lead to the accumulation of peroxides. By measuring the contents of H2O2 and O2−, we found that the salt-treated GmEF4-OE roots have lower H2O2 content and lower O2− content (Figure 7j,k).

Figure 7.

Phenotypic analysis of GmEF4-overexpressing (GmEF4-OE) and EV-control plants under salt treatment. (a) and (b) Phenotypes of GmEF4-OE and EV-control transgenic soybean plants under normal and salt treatment. (c) and (d) Phenotypes of GmEF4-OE and EV-control hairy roots under normal and salt treatment. (e) Survival of normal and salt-stressed plants. (f) MDA content and (g) proline content of GmEF4-OE and EV-control plants grown with salt treatment. (h) the root length, (i) total fresh weight, (j) H2O2 content, and (k) O2− content of GmEF4-OE and EV-control soybean hairy roots grown with salt treatment. The different letters in the bar graphs indicate significant differences at p < 0.05 between GmEF4-OE and EV-control transgenic soybean.

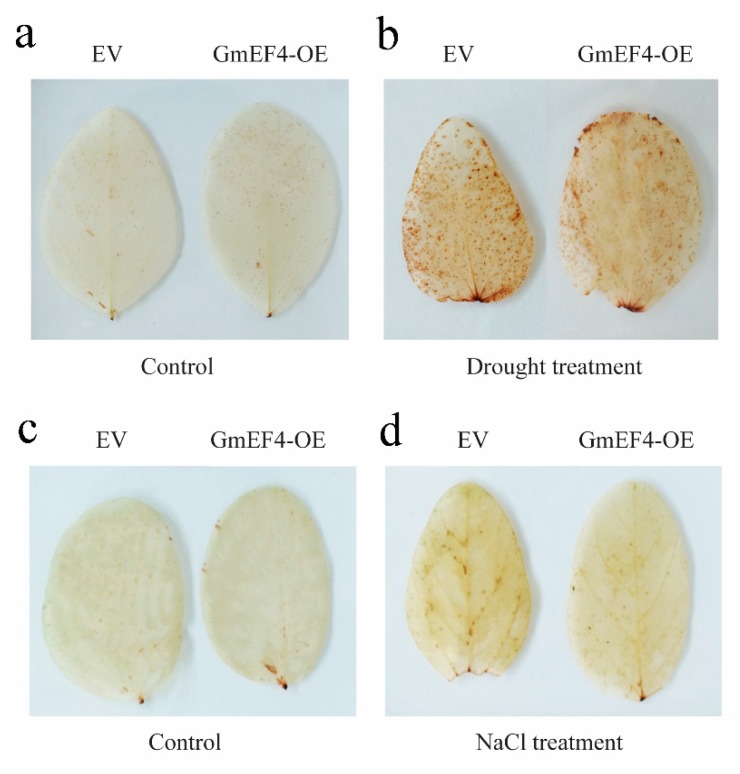

2.10. Overexpression of GmEF4 Reduced the Content of H2O2 under Drought and Salt Stresses

We used a 3, 3-diaminobenzidine (DAB) solution to detect the H2O2 content in EV-control and GmEF4-OE leaves. No significant difference was observed between the EV-control and GmEF4-OE leaves under normal growth conditions (Figure 8a,c), however, the color depth of the GmEF4-OE leaves was lower than EV-control leaves under drought and salt treatments (Figure 8b,d). This indicates that the overexpression of GmEF4 improved drought and salt tolerance in soybean.

Figure 8.

DAB staining of GmEF4-overexpressing (GmEF4-OE) and EV-control plants under drought and salt treatments. (a) and (b) DAB staining of GmEF4-OE and EV-control transgenic soybean plants under normal and drought treatment. (c) and (d) DAB staining of GmEF4-OE and EV-control transgenic soybean plants under normal and salt treatment.

3. Discussion

During evolution, plants have developed various mechanisms to respond to environmental factors [14,15]. A previous study has shown that higher expression of GmTIP2;3 can not only enhance the tolerance of plants to osmotic stress, but also effectively improve the tolerance of yeast to drought stress [16]. There are also several reports in barley and maize on the induction of EF1α under other abiotic stresses. In this study, 10 soybean EF1αs were identified and characterized after scanning the current version of the soybean genome. The dicotyledons soybean and Arabidopsis contain 10 and 4 EF1α genes, respectively, suggesting the possibility of a past double duplication event in the soybean genome [17] compared to a single duplication in Arabidopsis [18].

According to the qRT-PCR analysis, GmEF4 was highly expressed under exogenous ABA stress. It was reported that ABA can improve plant resistance to drought to ensure crops grow normally in challenging environments. We found that the EV-control and GmEF4-OE have no significant differences under normal growth conditions, but that drought and salt treatments caused obvious differences in the growth and physiology of the EV-control and the GmEF4 transgenic plants. Specifically, compared to the drought- and salt-treated EV-control plants, drought- and salt-treated GmEF4-OE plants had significantly delayed leaf wilting, longer roots, higher biomass, higher proline content, and lower MDA content. Hence, GmEF4 may be involved in the crosstalk of various stresses in plants.

EF1αs are associated with a number of proteins that exert their functional roles in plant biology. In previous study, the plant EF1α has been shown to physically interact with other proteins, suggesting that they may operate together in cellular processes in three ways: via enhanced translation, an interaction with the cytoskeleton, and catalysis phosphorylation in plants. EF1α is directly bound by plant calmodulins (CAMs), which inhibit its ability to bundle microtubules in vitro [19]. Wheat germ EF1α and GTP can bind with TYMV Val-RNA and form a stable complex [20], resulting in the inhibition of minus strand synthesis [21]. EF1α can bind to the PH domain of PLC-γ1. EF1α is regarded as a phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase activator through its interaction with the PH domain [22]. Thus, it is regarded as a multifunctional protein.

EF1α is involved in other cellular process through its interactions with other proteins. For example, ZmEF1α can interact with actin filaments under certain pH conditions (6.0–8.0) to regulate growth processes in plant cells [23]. Recently, it was reported that EF1αs mediate abiotic stress responses. The accumulation of EF1α was induced in ripe wheat under heat stress, which confirmed that EF1α was essential for the response to heat stress in crop [24]. In this study, soybean EF1α members highly respond to drought, salt, exogenous ABA. This could contribute to improving plant resistance to stress conditions through interactions with regulatory factors. This provides a basis for exploring the molecular mechanisms by which the EF1α family plays a specific role.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Genomic Location of Soybean EF1α Loci

To gather probable GmEF1α amino acid sequences candidates, the EF1α-type GTP-binding domain (Pfam: PF00009) was submitted as a query in BLASTP searches of the JGI Glyma1.0 genome version (http://www.phytozome.net/index.php) [25]. A total of 10 GmEF1α were identified after filtering out repeated sequences using SMART (http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de/). All nonredundant EF1αs were mapped onto six soybean chromosomes on the basis of information about their corresponding locations in the soybean database (http://soybase.org/).

4.2. Analysis of Gene Structure and cis-Acting Elements

An exon–intron structure map was created using GSDS online tools (http://gsds.cbi.pku.edu.cn/) to analyze gene structures and Promoter 2.0 (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/Promoter/) was used and to predict the promoter sequences of the GmEF1α genes. Potential cis-elements were analyzed using the plant cis-element database, PLACE26.0 (http://www.dna.affrc.go.jp/PLACE/signalscan. html).

4.3. Genomic and Phylogenetic Relationships and Expression Patterns

Both the EF1α gene sequences and protein sequences of Arabidopsis, rice, and maize were acquired from TAIR (http://arabidopsis.org), RGAP (http://rice.plantbiology.msu.edu), and TIGR (http://maize.jcvi.org/), respectively. Clustal X 2.0 was applied in a protein sequence comparison analysis of EF1αs in Arabidopsis, rice, maize, and soybean. A phylogenetic tree was constructed using the neighbor-joining method in MEGA 5.0 (http://megasoftware.net) using a bootstrap value of 500.

An analysis was performed by the Affymetrix soybean gene chip downloaded in SoyBase (https://www.soybase.org/soyseq/), which included the 10 soybean EF1αs in the different tissues and development stages. The heatmap was drawn using the software HemI.

4.4. RNA Extraction and qRT-PCR Assays

Isolation of the total RNA from soybean plants under drought and salt stress was performed using an RNA extraction kit (Takara, Shiga, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. cDNA synthesis was conducted as previously described [14]. The qRT-PCR expression was measured using an ABI Prism 7500 sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA), as described by Liu et al. [26]. Soybean actin (U60506) was used as internal controls for the normalization of the template cDNA. All primers used in the study are listed in Table S2.

4.5. Agrobacterium rhizogenes-Mediated Transformation of Soybean Hairy Roots

To generate GmEF4-OE soybean hairy roots, the coding sequences of GmEF4 were inserted into the plant transformation vector pCAMBIA3301 driven by the CaMV 35S promoter. The resultant constructs were introduced into Agrobacterium rhizogenes strain K599, and the bacterium was used to infect soybean hypocotyls by injection, as previously described [27,28]. The infected plants were transferred to a greenhouse and kept at high humidity until hairy roots were generated at the infection site. The original main roots were removed by cutting from 1 cm below the infection site. Seedlings were transplanted into a sieve-like plate containing mixed soil (1:1 vermiculite/humus) and then cultured normally in the greenhouse for 7 days (25 °C, 16 h light/8 h dark photoperiod).

4.6. Drought and Salt Tolerance Analyses

For soybean, GmEF4-OE and EV-control soybean seedlings with 3~5 cm hairy roots were planted in pots containing mixed soil (1:1 vermiculite/humus) and cultured normally in the greenhouse for 6~8 days, then EV-control and GmEF4-OE plants were grown without watering for 10 days. After drought treatment, we rewatered EV-control and GmEF4-OE plants for 3 days. For the salt stress assay, EV-control and GmEF4-OE plants were treated with 250 mM/L NaCl solution for 4 days [27,29].

4.7. Subcellular Localization

Full-length GmEF4 was fused to the N-terminus of the GFP gene under control of the CaMV 35S promoter [14]. Transient expressions of the 35S::GmEF4-GFP fusion construct and the GFP control vector were estimated by introducing the resultant DNAs into Arabidopsis protoplasts using a protocol [30]. FM4-64 dye (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA) was excited at 543 nm, and its fluorescence was recorded using a 650 nm long-pass filter. Subcellular localization of GFP expression in Arabidopsis protoplasts was monitored using confocal microscopy after 16 h/22 °C dark incubation using PEG-mediated transformation, as described elsewhere [26]. All transient expression experiments were repeated three times.

4.8. Measurements of Fresh Weight and Main Length

The root lengths were evaluated using an Epson Expression 11000XL root system scanning analyzer (Epson, Nagano, Japan). The fresh weights were measured using a Sartorius BSA224S-CW 1/10,000 analytical balance (Sartorius, Beijing, China).

4.9. Measurements of MDA Content, Proline Content, H2O2 Content, and O2− Content

For physiological parameter measurements, the leaves of drought- and salt-treated EV-control plants and GmEF4-OE plants were harvested for the measurements of MDA content and proline content. The GmEF4-OE and EV-control soybean seedlings with 3~5 cm hairy roots were planted in pots and grown in the greenhouse for 6~8 days, and were then grown without watering for 5 days and treated with 250 mM/L NaCl solution for 4 days before being harvested for measurement of H2O2 content and O2− content. The MDA content was assayed according to the protocol at http://www.cominbio.com/uploads/soft/190325/2-1Z325154356.pdf. About 0.1 g of soybean leaf was used and absorbance values at 532 and 600 nm. The MDA content was calculated using the following formula: MDA content (nmol/g FW) = 51.6 × (OD532−OD600)/0.1. The proline content was assayed according to the protocol at http://www.cominbio.com/uploads/soft/180727/1-1PHGF414.pdf. About 0.1 g of soybean leaf was used and absorbance values at 520 nm. The proline content was calculated using the following formula: Pro content (µg/g FW) = 38.4 × (OD520 + 0.0021)/0.1. The H2O2 content was assayed as previously described (http://www.cominbio.com/uploads/soft/180727/1-1PHGF628.pdf) [31]. About 0.1 g of soybean hairy roots was used and absorbance values at 415 nm. The H2O2 content was calculated using the following formula: H2O2 content (µmol/g FW) = 2.67 × (ΔA−0.0006)/0.1. The O2− content was assayed as previously described [31] (http://www.cominbio.com/uploads/soft/190326/2-1Z326145U1.pdf). Briefly, 1 mL extract solution was added to 0.1 g soybean hairy roots, ground into tissue homogenate on ice, centrifuged at 4 °C, 10,000 g for 20 min, and then the supernatant fraction was collected for reaction according to the manufacturer’s instruction. The O2− content was calculated using the following formula: O2− content (µmol/g FW) = 148.76 × (ΔA + 0.0027) × 1000/W. Absorbance values were measured with a Varioskan LUX Multimode Microplate Reader (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Each experiment was repeated three times.

4.10. DAB Staining

The GmEF4-OE and EV-control soybean seedlings with 3~5 cm hairy roots were planted in pots and grown in the greenhouse for 6~8 days, then were grown with and without watering for 5 days and treated with and without 250 mM/L NaCl solution for 4 days before being harvested for the DAB staining assay. The detached leaves were immersed into DAB solution (Solarbio, Beijing, China) for 14 h and transferred to 75% ethanol for decoloration until the samples become white [29].

5. Conclusions

We predicted the structures of different domains and analyzed gene locations, gene structures, phylogenetic relationships, various cis-elements, and conserved domains of soybean EF1αs. The expression patterns of 10 EF1α genes were analyzed by quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR). We found that GmEF4 was upregulated under drought, salt, and ABA treatments. Compared with the EV-control plants, GmEF4-OE plants exhibited drought and salt tolerant phenotypes. Thus, it provides a foundation basis for further functional genomics research about this important family under abiotic stress.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Lijuan Qiu of the Institute of Crop Science, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences for kindly providing soybean seeds.

Abbreviations

| EF1α | elongation factor 1α |

| pI | isoelectric points |

| ABREs | ABA-responsive elements |

| DREs | dehydration-responsive elements |

| EF-Tu | elongation factor thermo unstable |

| ABA | abscisic acid |

| qRT-PCR | quantitative real-time PCR |

| CAMs | calmodulins |

| GFP | green fluorescent protein |

| MDA | malondialdehyde |

| Pro | proline |

| DAF | days after flowering |

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary materials can be found at https://www.mdpi.com/1422-0067/20/12/3001/s1. Table S1; Analysis data of 10 GmEF1αs genes for the heat map. Table S2; Primers used in the paper. Figure S1; qRT-PCR analyses of GmEF4 expression in GmEF4-OE and EV-control transgenic soybean hairy roots.

Author Contributions

Z.-S.X. coordinated the project, conceived and designed experiments, and edited the manuscript; Y.G. performed experiments and wrote the first draft; J.M., J.-C.Z., and J.C. conducted the bioinformatic work and performed experiments; M.C. and Y.-B.Z. provided analytical tools and managed reagents; J.-D.F., Y.-Z.M. contributed with valuable discussions. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research was financially supported by the National Key R & D program of China (2016YFD0102102), the National Transgenic Key Project of the Ministry of Agriculture of China (2018ZX0800909B), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31871624) and talents Introduced Fund of Anhui Science and Technology University (NXYJ201604).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Zheng J., Liu H., Wang Y., Wang L., Chang X., Jing R., Hao C., Zhang X. TEF-7A, a transcript elongation factor gene, influences yield-related traits in bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) J. Exp. Bot. 2014;65:5351–5365. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eru306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Merrick W.C. Mechanism and regulation of eukaryotic protein synthesis. Microbiol. Rev. 1992;56:291–315. doi: 10.1128/mr.56.2.291-315.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kazuki S., Paul S. Omnipotent role of archaeal elongation factor 1 alpha (EF1α in translational elongation and termination, and quality control of protein synthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:19242–19247. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009599107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gonen H., Dickman D., Schwartz A.L., Ciechanover A. Protein synthesis elongation factor EF-1 alpha is an isopeptidase essential for ubiquitin-dependent degradation of certain proteolytic substrates. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1996;389:209–219. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4613-0335-0_26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dunn M.A., Morris A., Jack P.L., Hughes M.A. A low-temperature-responsive translation elongation factor 1 alpha from barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) Plant Mol. Biol. 1993;23:221–225. doi: 10.1007/BF00021434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berberich T., Sugawara K., Harada M., Kusano T. Molecular cloning, characterization and expression of an elongation factor 1 alpha gene in maize. Plant Mol. Biol. 1995;29:611–615. doi: 10.1007/BF00020988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fu J., Momcilović I., Prasad P.V.V. Roles of Protein Synthesis Elongation Factor EF-Tu in Heat Tolerance in Plants. J. Exp. Bot. 2012;835836:8. doi: 10.1155/2012/835836. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rathod D.P., Brestic M., Shao H.B. Chlorophyll a fluorescence determines the drought resistance capabilities in two varieties of mycorrhized and non-mycorrhized Glycine max Linn. Afr. J. Microbil. Res. 2011;5:4197–4206. doi: 10.5897/AJMR11.737. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hussain S., Iqbal N., Rahman T., Liu T., Brestic M., Safdar M.E., Asghar M.A., Farooq M.U., Shafiq I., Ali A., et al. Shade effect on carbohydrates dynamics and stem strength of soybean genotypes. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2019;162:374–382. doi: 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2019.03.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rose A.B. Intron-mediated regulation of gene expression. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2008;326:277–290. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-76776-3_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen Y., Yang X., He K., Liu M., Li J., Gao Z., Lin Z., Zhang Y., Wang X., Qiu X., et al. The MYB Transcription Factor Superfamily of Arabidopsis: Expression Analysis and Phylogenetic Comparison with the Rice MYB Family. Plant Mol. Biol. 2006;60:107–124. doi: 10.1007/s11103-005-2910-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li W., Cui X., Meng Z., Huang X., Xie Q., Wu H., Jin H., Zhang D., Liang W. Transcriptional regulation of Arabidopsis MIR168a and argonaute1 homeostasis in abscisic acid and abiotic stress responses. Plant Physiol. 2012;158:1279–1292. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.188789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feder M.E., Hofmann G.E. Heat-shock proteins, molecular chaperones, and the stress response: Evolutionary and ecological physiology. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 1999;61:243–282. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.61.1.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu Z.S., Xia L.Q., Chen M., Cheng X.G., Zhang R.Y., Li L.C., Zhao Y.X., Lu Y., Ni Z.Y., Liu L., et al. Isolation and molecular characterization of the Triticum aestivum L. ethylene-responsive factor 1 (TaERF1) that increases multiple stress tolerance. Plant Mol. Biol. 2007;65:719–732. doi: 10.1007/s11103-007-9237-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu Z.S., Chen M., Li L.C., Ma Y.Z. Functions and application of the AP2/ERF transcription factor family in crop improvement. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2011;53:570–585. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2011.01062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang D.Y., Tong J.F., He X.L., Xu Z.L., Xu L., Wei P.P., Huang Y.H., Brestic M., Ma H.X., Shao H.B. A Novel Soybean Intrinsic Protein Gene, GmTIP2;3, Involved in Responding to Osmotic Stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2016;6 doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.01237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schlueter J.A., Dixon P., Granger C., Grant D., Clark L., Doyle J.J., Shoemaker R.C. Mining EST databases to resolve evolutionary events in major crop species. Genome. 2004;47:868–876. doi: 10.1139/g04-047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blanc G., Barakat A., Guyot R., Cooke R., Delseny M. Extensive duplication and reshuffling in the Arabidopsis genome. Plant Cell. 2000;12:1093–1102. doi: 10.1105/tpc.12.7.1093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaur K.J., Ruben L. Protein translation elongation factor-1 alpha from Trypanosoma brucei binds calmodulin. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:23045–23050. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Joshi R.L., Ravel J.M., Haenni A.L. Interaction of turnip yellow mosaic virus Val-RNA with eukaryotic elongation factor EF-1 [alpha]. Search for a function. EMBO J. 1986;5:1143–1148. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04339.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matsuda D., Yoshinari S., Dreher T.W. eEF1A binding to aminoacylated viral RNA represses minus strand synthesis by TYMV RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. J. Virol. 2004;321:47–56. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2003.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chang J.S., Seok H., Kwon T.K., Min D.S., Ahn B.H., Lee Y.H., Suh J.W., Kim J.W., Iwashita S., Omori A., et al. Interaction of elongation factor-1alpha and pleckstrin homology domain of phospholipase C-gamma 1 with activating its activity. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:19697–19702. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111206200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gungabissoon R.A., Khan S., Hussey P.J., Maciver S.K. Interaction of elongation factor 1α from Zea mays (ZmEF-1α) with F-actin and interplay with the maize actin severing protein, ZmADF3. Cytoskeleton. 2010;49:104–111. doi: 10.1002/cm.1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Urška B., Fu J., Miranda B., Vara Prasad P.V., Zoran R. Heat tolerance and expression of protein synthesis elongation factors, EF-Tu and EF-1α, in spring wheat. Funct. Plant Biol. 2009;36:234–241. doi: 10.1071/FP08266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goodstein D.M., Shu S., Howson R., Neupane R., Hayes R.D., Fazo J., Mitros T., Dirks W., Hellsten U., Putnam N., et al. Phytozome: A comparative platform for green plant genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:D1178. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu P., Xu Z.S., Lu P.P., Hu D., Chen M., Li L.C., Ma Y.Z. A wheat PI4K gene whose product possesses threonine autophophorylation activity confers tolerance to drought and salt in Arabidopsis. J. Exp. Bot. 2013;64:2915–2927. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ert133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hao Y.J., Wei W., Song Q.X., Chen H.W., Zhang Y.Q., Wang F., Zou H.F., Lei G., Tian A.G., Zhang W.K., et al. Soybean NAC transcription factors promote abiotic stress tolerance and lateral root formation in transgenic plants. Plant J. 2011;68:302–313. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04687.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang F., Chen H.W., Li Q.T., Wei W., Li W., Zhang W.K., Ma B., Bi Y.D., Lai Y.C., Liu X.L., et al. GmWRKY27 interacts with GmMYB174 to reduce expression of GmNAC29 for stress tolerance in soybean plants. Plant J. 2015;83:224–236. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Du Y.T., Zhao M.J., Wang C.T., Gao Y., Wang Y.X., Liu Y.W., Chen M., Chen J., Zhou Y.B., Xu Z.S. Identification and characterization of GmMYB118 responses to drought and salt stress. BMC Plant Biol. 2018;18:320. doi: 10.1186/s12870-018-1551-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yoo S.D., Cho Y.H., Sheen J. Arabidopsis mesophyll protoplasts: A versatile cell system for transient gene expression analysis. Nat. Protoc. 2007;2:1565–1572. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cui X.Y., Gao Y., Guo J., Yu T.F., Zheng W.J., Liu Y.W., Chen J., Xu Z.S., Ma Y.Z. BES/BZR Transcription Factor TaBZR2 Positively Regulates Drought Responses by Activation of TaGST1. Plant Physiol. 2019;180:1605–1620. doi: 10.1104/pp.19.00100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.