Abstract

PAR2 is a proteolytically activated G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) that is implicated in various cancers and inflammatory diseases. Ligands with low nanomolar affinity for PAR2 have been developed, but there is a paucity of research on the development of PAR2-targeting imaging probes. Here, we report the development of seven novel PAR2-targeting compounds. Four of these compounds are highly potent and selective PAR2-targeting peptides (EC50 = 10 to 23 nM) that have a primary amine handle available for facile conjugation to various imaging components. We describe a peptide of the sequence Isox-Cha-Chg-ARK(Sulfo-Cy5)-NH2 as the most potent and highest affinity PAR2-selective fluorescent probe reported to date (EC50 = 16 nM, KD = 38 nM). This compound has a greater than 10-fold increase in potency and binding affinity for PAR2 compared to the leading previously reported probe and is conjugated to a red-shifted fluorophore, enabling in vitro and in vivo studies.

Keywords: Proteinase-activated receptor 2 (PAR2), peptide, targeted fluorescent probes, fluorescence imaging, structure−activity relationship

Proteinase-activated receptors (PARs) are a four-member family (PAR1–4) of G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) that are self-activated by a tethered ligand after a protease cleaves an N-terminal portion of the protein. While PAR1, PAR3, and PAR4 are targets for thrombin, PAR2 is activated by various trypsin-like serine proteases (e.g., trypsin, tryptase, granzyme A, KLK4) to reveal the tethered ligand sequence SLIGKV (in humans) or SLIGRL (in rodents).1−5

PAR2 is endogenously expressed in various tissues (e.g., pancreas, liver, small intestine, colon) and is involved in inflammation and cell migration.6−8 However, abnormal function and inappropriate expression of PAR2 have been linked to various cancers and inflammatory diseases. More specifically, PAR2 is implicated in conditions such as arthritis, colitis, asthma, cardiovascular disease, prostate cancer, lung cancer, gastric cancer, melanoma, ovarian cancer, and breast cancer.9−23 In cancerous tissue, this undesirable activity of PAR2 has been shown to significantly contribute to cell proliferation, angiogenesis, and metastasis.11,24,25 Given these important roles in physiology and pathology, PAR2 has emerged as a major drug target, and there is much interest in developing novel chemical probes and imaging agents that can specifically bind PAR2 with high affinity.

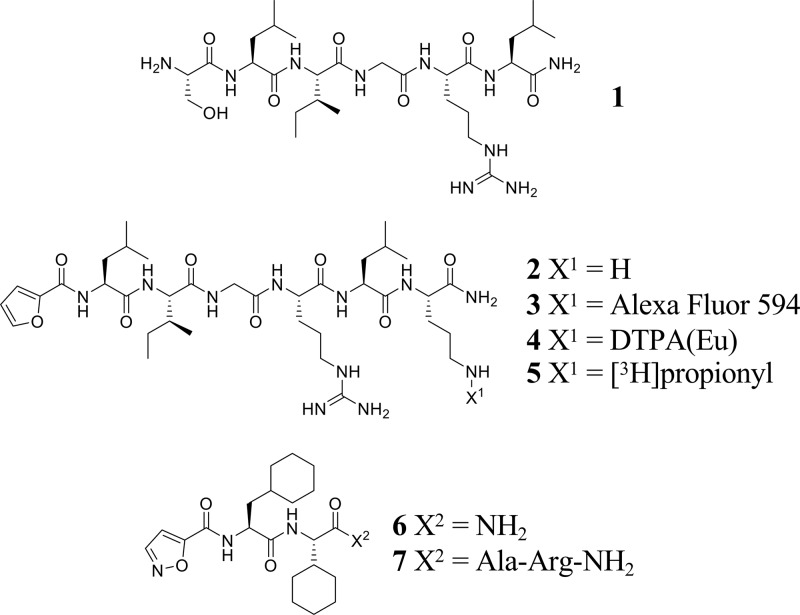

Over the years a number of agonists have been developed that specifically bind to and activate PAR2. Initial reports synthesized and evaluated peptides that resemble the tethered ligand sequences SLIGKV and SLIGRL as well as their amidated analogues, and showed that SLIGRL-NH2 (1, Figure 1) had the highest potency/affinity for human PAR2 and has thus been widely used as a PAR2 agonist with micromolar potency.2,26,27 Extensive structure–activity relationship studies have explored substitution of various natural and unnatural amino acids into these sequences, generating peptides with improved potency. In particular, substituting the serine residue in the first position with various heterocycles (e.g., 2-furoyl, 5-isoxazoloyl, 3-pyridoyl, 4-(2-methyloxazoloyl), and 2-aminothiazol-4-oyl) has substantially improved potency and affinity for PAR2.28 Of these, 2-furoyl (2f) based peptides initially showed the best improvements and have been widely used.29 The addition of ornithine to the C-terminus of the 2f-LIGRL-NH2 hexapeptide (2, Figure 1) and conjugation of various bulky substituents to the side chain of that ornithine (e.g., Alexa Fluor 594, 3 and DTPA(Eu), 4, Figure 1) have shown no appreciable effect on their potency, affinity, or selectivity for PAR2.30,31 More recently, Isox-Cha-Chg (5-isoxazoloyl-cyclohexylalanine-cyclohexylglycine) based peptides developed by Yau et al. (2016) and Jiang et al. (2017), most notably Isox-Cha-Chg-AR-NH2 (7, Figure 1), have shown substantial improvements in potency and affinity for PAR2.32,33

Figure 1.

A number of PAR2 targeted fluorescent and tritiated probes having been reported.27,30,31,34,35 In particular, 3 is the highest affinity fluorescent probe developed to date, which has submicromolar affinity and an Alexa Fluor 594 fluorescent dye (excitation maximum = 590 nm, emission maximum = 617 nm).30 The development of higher affinity fluorescent probes would improve uptake in cells and tissues expressing PAR2 and result in benefits such as reduced off target binding, less compound requirement, and reduced adverse effects when used in vivo. Development of red-shifted fluorescent probes would also allow improved in vivo imaging in small animals due to less absorption and scattering from biomolecules of the red-shifted light compared to blue-shifted light. Most imperatively, such fluorescent probes targeting PAR2 can also be useful chemical tools for various in vitro experiments (e.g., competitive binding assays, determination of PAR2 expression levels, insight into PAR2 trafficking). In the long term, targeted fluorescent probes have potential clinical applications in determining receptor expression in histopathological sections or intraoperative imaging for image guided surgery.

Compounds reported by Jiang et al. (2017) are some of the leading PAR2-targeting compounds reported to date, most notably, Isox-Cha-Chg-AR-NH2 (7), but none have been modified to allow for facile conjugation of imaging components.33 This work describes the development of Isox-Cha-Chg-AR-NH2 related peptides that contain strategically designed amine handles to allow for facile conjugation of imaging components in order to develop an improved PAR2-targeting fluorescent probe with low nanomolar affinity/potency for the receptor and with a red-shifted fluorescent dye (Sulfo-Cy5, excitation maximum = 646 nm, emission maximum = 662 nm). In addition, this work describes the evaluation of the improved fluorescent probe in vitro.

Peptides were synthesized and evaluated for PAR2-activation through a β-arrestin 2 recruitment assay in human embryonic kidney (HEK)-293T cells in an effort to develop a more potent, higher affinity PAR2-selective fluorescent probe. In the assay and cell line reported here, compounds 1, 2, 6, and 7 showed a similar potency trend to previous reports of binding affinity for PAR2 (7 ≫ 2 ≫ 6 > 1, from most to least potent, Table 1).27,30,33 Following these results, the best reported PAR2-targeting peptide (7) from Jiang et al. (2017) was modified with a primary amine on the C-terminus in various ways. These modifications were made since conjugation of imaging components directly to 7 was not synthetically feasible and because the addition of a linker region between the targeting moiety and the imaging moiety would help keep bulky substituents (e.g., Sulfo-Cy5) from interfering with the receptor–ligand interactions. We focused on C-terminal modifications of 7 because of insight from previous research on the development of compounds like 3 and 4, as well as reports demonstrating that the N-terminal portion of PAR2-targeting peptides are much more crucial for binding than the C-terminal portion.30,31,33 Furthermore, we assessed hydrophilicity measures of all peptides through a LogD experiment to optimize the peptides so that the dye-conjugated probe would be relatively water-soluble for ease of use in in vitro experiments.

Table 1. PAR2-Targeted Peptides (1, 2, and 6–12) with Their EC50 and LogD Valuesa.

| # | compound | EC50 (nM) | pEC50 ± SEM | LogD ± SEM |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | SLIGRL-NH2 | 7144 | 5.15 ± 0.03 | –1.02 ± 0.02 |

| 2 | 2f-LIGRLO-NH2 | 210 | 6.68 ± 0.04 | –1.06 ± 0.01 |

| 6 | Isox-Cha-Chg-NH2 | 2555 | 5.59 ± 0.10 | 2.00 ± 0.02 |

| 7 | Isox-Cha-Chg-AR-NH2 | 14 | 7.86 ± 0.06 | –0.15 ± 0.01 |

| 8 | Isox-Cha-Chg-AR-NH(CH2)6NH2 | 16 | 7.79 ± 0.04 | –0.40 ± 0.01 |

| 9 | Isox-Cha-Chg-ARLK-NH2 | 23 | 7.65 ± 0.07 | –0.72 ± 0.02 |

| 10 | Isox-Cha-Chg-ARAK-NH2 | 15 | 7.82 ± 0.07 | –1.58 ± 0.04 |

| 11 | Isox-Cha-Chg-ARK-NH2 | 10 | 8.00 ± 0.09 | –0.86 ± 0.02 |

| 12 | Isox-Cha-Chg-ARK(COCH3)-NH2 | 16 | 7.78 ± 0.05 | –0.24 ± 0.02 |

EC50 values determined through a dose–response curve from a β-arrestin 2 recruitment assay in HEK293T cells transiently transfected with PAR2-eYFP/Arr2-rluc BRET pair (n ≥ 3). LogD values were determined at a physiological pH of 7.4 (n = 3).

The first approach was the addition of an aminohexyl spacer extending from the peptide backbone of 7 to yield 8. This was intended such that conjugation of the dye to the C-terminus would allow the dye to lie outside of the receptor binding pocket. This modification resulted in minimal to no reduction in potency (from EC50 = 14 nM to EC50 = 16 nM) and a slight increase in hydrophilicity from a LogD value of −0.15 to −0.40 (Table 1). We however sought to further increase the hydrophilicity of the peptides because acylation of the primary amine, a result of NHS ester dye conjugation, will have a modest increase in hydrophobicity.

In an effort to increase the hydrophilicity, 9 was synthesized. The addition of leucine-lysine (position 6 and 7) to the C-terminus of 7 was proposed, in order to resemble the previously reported 2, which added ornithine (position 7) to the C-terminus of 2f-LIGRL-NH2. Although this modification increased the hydrophilicity, it showed a slight decrease in potency (EC50 = 23 nM, Table 1). From here, alanine-lysine was added to the C-terminus of 7 to further increase hydrophilicity and to reduce steric bulk at position 6 while still allowing for the same peptide backbone length as 9 and 2. This yielded 10, which was found to have improved potency and hydrophilicity compared to 9 (EC50 = 15 nM, LogD = −1.58, Table 1). Compound 11 was synthesized through the direct addition of lysine to the C-terminus of 7. It showed a decrease in hydrophilicity compared to 10 (LogD = −0.86, Table 1) but was still more hydrophilic than either 8 or 9 and showed the highest potency (EC50 = 10 nM, Table 1). Furthermore, 11 had a similar LogD value compared to 2, in which the dye-conjugated version of 2 has already shown success in in vitro experiments.30 Therefore, 11 was taken forward as the lead candidate.

The lysine side chain of 11 was then acetylated to observe the effect of losing this positive charge. This yielded 12, which was found to have only a slight reduction in potency (EC50 = 16 nM, Table 1) compared to 11 (EC50 = 10 nM, Table 1), suggesting this charge was not crucial for PAR2 binding, making 11 a good candidate to label with a fluorescent dye.

In addition to potency and hydrophobicity measures, receptor selectively was also assessed through a fluorescent calcium assay to ensure the synthesized peptides target PAR2 specifically. All known and novel PAR2-targeting peptides (1-2 and 6-12) were found to bind selectively to the PAR2 receptor as determined by the significant response in the PAR2 expressing HEK293T cells compared to the lack of response in the PAR2 knock out (KO) HEK293T cells (Table 2, see Figure S1 for representative examples of PAR2-selectivity traces). As a control, a PAR1-specific agonist (TFLLR-NH2, 13) was assessed for its calcium response in both of these cells lines as they both contain the PAR1 receptor (Table 2). These cell lines and this control were used (similar to previous reports) because it is known that some PAR2-targeting peptides can also bind to PAR1.32,33,36,37

Table 2. PAR2 Selectivity of Peptides 1, 2, and 6–12a.

| # | net % max Ca2+ release in PAR2 expressing cells ± SEM | net % max Ca2+ release in PAR2 KO cells ± SEM |

|---|---|---|

| 13 | 49.3 ± 4.4 | 67.5 ± 6.6 |

| 1 | 53.4 ± 7.9 | –0.5 ± 0.5 |

| 2 | 53.0 ± 6.4 | 0.7 ± 1.2 |

| 6 | 17.2 ± 4.2 | –1.4 ± 1.3 |

| 7 | 64.6 ± 4.9 | –0.5 ± 0.5 |

| 8 | 68.6 ± 9.3 | 0.0 ± 0.4 |

| 9 | 69.9 ± 4.1 | –0.4 ± 0.4 |

| 10 | 67.3 ± 3.9 | –1.1 ± 0.5 |

| 11 | 72.0 ± 5.0 | –0.9 ± 0.3 |

| 12 | 67.3 ± 2.6 | –1.4 ± 0.5 |

Selectivity measures are shown as calcium response in PAR2 expressing (column two) versus PAR2 KO (column three) HEK293T cells (n ≥ 2). Final concentration of 100 μM for 13 and 1 and 10 μM for 2 and 6–12.

The lead candidate (11) was labeled through the lysine side chain with a Sulfo-Cy5 NHS ester fluorescent dye to yield compound 15 (Scheme 1). Compound 14 was synthesized to resemble the previously reported PAR2-targeting fluorescent probe with the highest potency/affinity (3).30 Compound 14 contains an identical PAR2-targeting peptide sequence compared to 3 but utilizes Sulfo-Cy5 dye conjugated through the ornithine side chain as opposed to an Alexa Fluor 594 dye. The Sulfo-Cy5 dye allows for a more direct comparison to the novel Sulfo-Cy5 dye conjugated peptide reported here (15) as well as it is a red-shifted and less costly dye.

Scheme 1. PAR2-Selective Fluorescent Probe (15) Synthesis.

The potency and hydrophilicity of 14 (EC50 = 296 nM, LogD = −0.88, Table 3) was similar to its unlabeled counterpart, 2 (EC50 = 210 nM, LogD = −1.06, Table 1), and consistent with previous reports for the potency of analogous probes modified from this peptide sequence.30,38 Successfully, compound 15 also showed similar potency and hydrophilicity (EC50 = 16 nM, LogD = −1.18, Table 3) compared to its unlabeled counterpart, 11 (EC50 = 10 nM, LogD = −0.86, Table 1). More importantly though, 15 was found to have a greater than 10-fold increase in potency compared to 14 (EC50 = 16 nM vs EC50 = 296 nM, Table 3, Figure 2A).

Table 3. Evaluation of Sulfo-Cy5 Labeled Peptides (14 and 15)a.

| # | compound | EC50 (nM) | pEC50 ± SEM | KD (nM) | pKD ± SEM | LogD ± SEM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 14 | 2f-LIGRLO(Sulfo-Cy5)-NH2 | 296 | 6.53 ± 0.05 | 430 | 6.24 ± 0.13 | –0.88 ± 0.04 |

| 15 | Isox-Cha-Chg-ARK(Sulfo-Cy5)-NH2 | 16 | 7.81 ± 0.09 | 38 | 7.20 ± 0.22 | –1.18 ± 0.13 |

EC50 values determined through a dose–response curve from a β-arrestin 2 recruitment assay in HEK293T cells transiently transfected with PAR2-eYFP/Arr2-rluc BRET pair (n ≥ 3). KD values determined through a flow cytometry saturation binding experiment in HEK293T cells (n ≥ 4). LogD values were determined at a physiological pH of 7.4 (n = 3).

Figure 2.

(A) PAR2 β-arrestin 2 recruitment dose–response curves of 1, 14, and 15 in HEK293T cells transiently transfected with PAR2-eYFP/Arr2-rluc BRET pair (n ≥ 3) and (B) saturation binding experiments of PAR2 for determination of affinity measures (KD) of 14 and 15 in HEK293T cells (n ≥ 4).

Similar to the increase in potency, 15 had a similar increase in affinity compared to 14 (>10 fold) for PAR2 as determined through a saturation binding experiment using flow cytometry (KD = 38 nM vs KD = 430 nM, Table 3, and binding curves shown in Figure 2B). As a control, competition of 14 and 15 with an excess of a known PAR2-specific peptide (7) was completed, which showed a substantial decrease in fluorescence signal for both of the fluorescent peptides (Table S1).

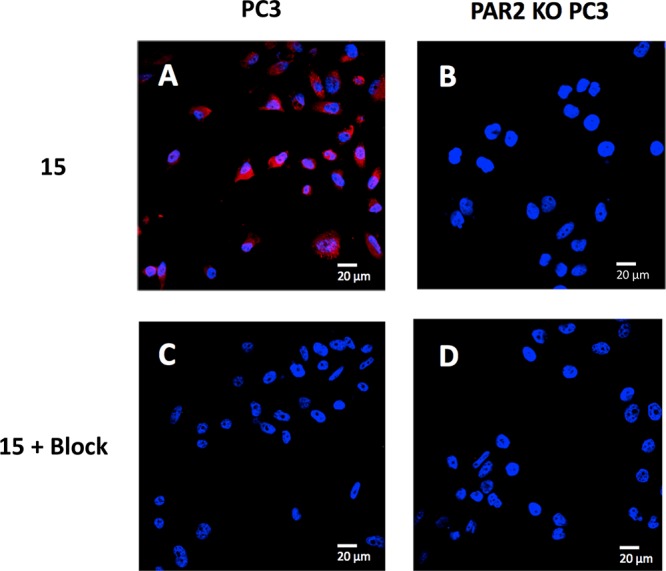

Compound 15 was further evaluated for its in vitro applications using confocal microscopy. It was found that this fluorescent probe binds selectively to PAR2 (Figure 3, see Figure S3 for additional representative examples) and colocalizes with PAR2 intracellularly (Figure S4). The PAR2 expressing prostate cancer (PC3) cells showed substantial uptake of 15 (Figure 3A) compared to the controls (PAR2 KO PC3 cells, Figure 3B; PAR2 expressing PC3 cells blocked with excess of an unlabeled known PAR2-selective peptide, 7, Figure 3C; and PAR2 KO PC3 cells with excess of 7, Figure 3D).

Figure 3.

Confocal microscopy of 15 in PC3 derived cell lines. Compound 15 (250 nM final concentration) incubated with (A) PC3 cells and (B) PAR2 KO PC3 cells (n = 3). Compound 15 and PAR2-selective blocking peptide, 7 (2500 nM final concentration) coincubated with (C) PC3 cells and (D) PAR2 KO PC3 cells (n = 3). Uptake of 15 was effectively blocked upon coincubation with 7. Sulfo-Cy5 signal shown in red and DAPI signal shown in blue. Size reference = 20 μm.

The novel peptides described here show high potency and selectively for PAR2. The various modifications led to slightly different structural and hydrophobic properties while showing minimal to no detrimental effect on PAR2 binding and with each peptide having the ability for facile conjugation of an imaging component (NHS ester dyes, common radioactive prosthetic groups, etc.) through their amine handle. Furthermore, the peptides described here provide a suitable platform for the development of targeted drug delivery conjugates for PAR2-related diseases. Targeted drug delivery conjugates generally involve conjugating a therapeutic component through a linker to a targeting moiety. The amine-modified peptides described here can be readily conjugated to a therapeutic component to develop such agents. Although functionalizing these peptides with these various other substituents could influence PAR2-binding, our findings suggest there is modest freedom with the functionalization of the C-terminal amino acids of this family of PAR2-targeted peptides.

To the best of our knowledge, compound 15 is the most potent, highest affinity PAR2-targeting fluorescent probe reported to date with a red-shifted fluorophore and a greater than 10-fold improvement in potency and affinity when compared to the best previously reported probe.30 Compound 15 was also validated in an in vitro confocal microscopy experiment, further demonstrating its candidacy as a useful chemical tool for various in vitro experiments as well as potential clinical relevance in PAR2-related diseases.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Detailed experimental procedures are found in the Supporting Information.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Mike Keeney (Coordinator Hematology/Flow Cytometry), Ben Hedley Ph.D., and Lori Lowes Ph.D. for their assistance in the flow cytometry experiments.

Glossary

ABBREVIATIONS

- 2f

2-furoyl

- Isox

5-isoxazoloyl

- Alloc

allyloxycarbonyl

- BRET

bioluminescence resonance energy transfer

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

- C-terminus

carboxy-terminus

- Cha

l-cyclohexylalanine

- Chg

l-cyclohexylglycine

- LogD

logarithm of the distribution coefficient

- DAPI

4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride

- DCM

dichloromethane

- DIPEA

N,N-diisopropylethylamine

- DMF

N,N-dimethylformamide

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- DTPA

diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid

- EC50

half-maximal effective concentration

- EDTA

ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid

- ESI

electrospray ionization

- eYFP

enhanced yellow fluorescent protein

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- Fmoc

fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl

- GPCR

G protein-coupled receptor

- HATU

O-(7-azabenzotriazol-1-yl)-N,N,N′,N′-tetramethyluronium hexafluorophosphate

- HBSS

Hank’s balanced salt solution

- HCTU

O-(1H-6-chlorobenzotriazole-1-yl)-1,1,3,3-tetramethyluronium hexafluorophosphate

- HEK293T

highly transfectable human embryonic kidney cell line

- HEPES

4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid

- HRMS

high-resolution mass spectrometry

- KD

dissociation binding constant

- KLK4

kallikrein-related peptidase 4

- KO

knock out

- N-terminus

amino-terminus

- NHS

N-hydroxysuccinimide

- PAR

proteinase-activated receptor

- PBS

phosphate buffered saline

- PC3

prostate cancer cell line

- pEC50

–Log[EC50]

- pH

–Log[H+]

- pKD

–Log[KD]

- PTI

Photon Technologies Institute

- r.t.

room temperature

- rluc

renilla luciferase

- RP-HPLC

reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography

- SEM

standard error of the mean

- SPPS

solid-phase peptide synthesis

- Sulfo-Cy5

Sulfo-Cyanine5

- TFA

trifluoroacetic acid

- TIPS

triisopropylsilane

- UV

ultraviolet

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.9b00094.

Experimental methods, PAR2-selctivity measurements, flow cytometry control experiments, additional confocal microscopy data, and compound characterization data (PDF)

Author Contributions

J.C.L., P.T., M.M., R.R., and L.G.L. analyzed results and contributed to the writing of the manuscript. M.M. completed experiments for determination of LogD values; J.C.L. and P.T. performed all other experimental work.

Funding provided by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC) of Canada and supported by a grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Molino M.; Numerof R.; Barnathan E. S.; Clark J.; Dreyer M.; Cumashi A.; Hoxie J. a.; Schechter N.; Woolkalis M.; Brass L. F. Interactions of Mast Cell Tryptase with Thrombin Receptors and PAR-2. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272 (7), 4043–4049. 10.1074/jbc.272.7.4043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nystedt S.; Emilsson K.; Wahlestedt C.; Sundelin J. Molecular Cloning of a Potential Proteinase Activated Receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1994, 91 (20), 9208–9212. 10.1073/pnas.91.20.9208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen K. K.; Sherman P. M.; Cellars L.; Andrade-Gordon P.; Pan Z.; Baruch A.; Wallace J. L.; Hollenberg M. D.; Vergnolle N. A Major Role for Proteolytic Activity and Proteinase-Activated Receptor-2 in the Pathogenesis of Infectious Colitis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2005, 102 (23), 8363–8368. 10.1073/pnas.0409535102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsay A. J.; Dong Y.; Hunt M. L.; Linn M.; Samaratunga H.; Clements J. A.; Hooper J. D. Kallikrein-Related Peptidase 4 (KLK4) Initiates Intracellular Signaling via Protease-Activated Receptors (PARs): KLK4 and PAR-2 Are Co-Expressed during Prostate Cancer Progression. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283 (18), 12293–12304. 10.1074/jbc.M709493200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams M. N.; Ramachandran R.; Yau M. K.; Suen J. Y.; Fairlie D. P.; Hollenberg M. D.; Hooper J. D. Structure, Function and Pathophysiology of Protease Activated Receptors. Pharmacol. Ther. 2011, 130 (3), 248–282. 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2011.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nystedt S.; Emilsson K.; Larsson a K.; Strömbeck B.; Sundelin J. Molecular Cloning and Functional Expression of the Gene Encoding the Human Proteinase-Activated Receptor 2. Eur. J. Biochem. 1995, 232 (1), 84–89. 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.tb20784.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohm S. K.; Kong W.; Bromme D.; Smeekens S. P.; Anderson D. C.; Connolly A.; Kahn M.; Nelken N. A.; Coughlin S. R.; Payan D. G.; et al. Molecular Cloning, Expression and Potential Functions of the Human Proteinase-Activated Receptor-2. Biochem. J. 1996, 314 (12), 1009–1016. 10.1042/bj3141009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagerberg L.; Hallström B. M.; Oksvold P.; Kampf C.; Djureinovic D.; Odeberg J.; Habuka M.; Tahmasebpoor S.; Danielsson A.; Edlund K.; et al. Analysis of the Human Tissue-Specific Expression by Genome-Wide Integration of Transcriptomics and Antibody-Based Proteomics. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 2014, 13 (2), 397–406. 10.1074/mcp.M113.035600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cocks T. M.; Fong B.; Chow J. M.; Anderson G. P.; Frauman A. G.; Goldie R. G.; Henry P. J.; Carr M. J.; Hamilton J. R.; Moffatt J. D. A Protective Role for Protease-Activated Receptors in the Airways. Nature 1999, 398 (6723), 156–160. 10.1038/18223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damiano B. P.; Cheung W. M.; Santulli R. J.; Fung-Leung W. P.; Ngo K.; Ye R. D.; Darrow a L.; Derian C. K.; de Garavilla L.; Andrade-Gordon P. Cardiovascular Responses Mediated by Protease-Activated Receptor-2 (PAR-2) and Thrombin Receptor (PAR-1) Are Distinguished in Mice Deficient in PAR-2 or PAR-1. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1999, 288 (2), 671–678. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su S.; Li Y.; Luo Y.; Sheng Y.; Su Y.; Padia R. N.; Pan Z. K.; Dong Z.; Huang S. Proteinase-Activated Receptor 2 Expression in Breast Cancer and Its Role in Breast Cancer Cell Migration. Oncogene 2009, 28 (34), 3047–3057. 10.1038/onc.2009.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antoniak S.; Rojas M.; Spring D.; Bullard T. A.; Verrier E. D.; Blaxall B. C.; MacKman N.; Pawlinski R. Protease-Activated Receptor 2 Deficiency Reduces Cardiac Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury. Arterioscler., Thromb., Vasc. Biol. 2010, 30 (11), 2136–2142. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.213280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D. H.; Cho Y. J.; Kim J. H.; Kim Y. B.; Lee K. J. Stress-Induced Alterations in Mast Cell Numbers and Proteinase-Activated Receptor-2 Expression of the Colon: Role of Corticotrophin-Releasing Factor. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2010, 25 (9), 1330–1335. 10.3346/jkms.2010.25.9.1330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohman R.-J.; Cotterell A. J.; Barry G. D.; Liu L.; Suen J. Y.; Vesey D. A.; Fairlie D. P. An Antagonist of Human Protease Activated Receptor-2 Attenuates PAR2 Signaling, Macrophage Activation, Mast Cell Degranulation, and Collagen-Induced Arthritis in Rats. FASEB J. 2012, 26 (7), 2877–2887. 10.1096/fj.11-201004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aman M.; Ohishi Y.; Imamura H.; Shinozaki T.; Yasutake N.; Kato K.; Oda Y. Expression of Protease-Activated Receptor-2 (PAR-2) Is Related to Advanced Clinical Stage and Adverse Prognosis in Ovarian Clear Cell Carcinoma. Hum. Pathol. 2017, 64, 156–163. 10.1016/j.humpath.2017.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cenac N.; Coelho A. M.; Nguyen C.; Compton S.; Andrade-Gordon P.; MacNaughton W. K.; Wallace J. L.; Hollenberg M. D.; Bunnett N. W.; Garcia-Villar R.; et al. Induction of Intestinal Inflammation in Mouse by Activation of Proteinase-Activated Receptor-2. Am. J. Pathol. 2002, 161 (5), 1903–1915. 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64466-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrell W. R.; Lockhart J. C.; Kelso E. B.; Dunning L.; Plevin R.; Meek S. E.; Smith A. J. H.; Hunter G. D.; Mclean J. S.; Mcgarry F.; et al. Essential Role for Proteinase- Activated Receptor-2 in Arthritis. J. Clin. Invest. 2003, 111 (1), 35–41. 10.1172/JCI16913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin E.; Fujiwara M.; Pan X.; Ghazizadeh M.; Arai S.; Ohaki Y.; Kajiwara K.; Takemura T.; Kawanami O. Protease-Activated Receptor (PAR)-1 and PAR-2 Participate in the Cell Growth of Alveolar Capillary Endothelium in Primary Lung Adenocarcinomas. Cancer 2003, 97 (3), 703–713. 10.1002/cncr.11087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massi D.; Naldini A.; Ardinghi C.; Carraro F.; Franchi A.; Paglierani M.; Tarantini F.; Ketabchi S.; Cirino G.; Hollenberg M. D.; et al. Expression of Protease-Activated Receptors 1 and 2 in Melanocytic Nevi and Malignant Melanoma. Hum. Pathol. 2005, 36 (6), 676–685. 10.1016/j.humpath.2005.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caruso R.; Pallone F.; Fina D.; Gioia V.; Peluso I.; Caprioli F.; Stolfi C.; Perfetti A.; Spagnoli L. G.; Palmieri G.; et al. Protease-Activated Receptor-2 Activation in Gastric Cancer Cells Promotes Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Trans-Activation and Proliferation. Am. J. Pathol. 2006, 169 (1), 268–278. 10.2353/ajpath.2006.050841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimoto D.; Hirono Y.; Goi T.; Katayama K.; Hirose K.; Yamaguchi A. Expression of Protease Activated Receptor-2 (PAR-2) in Gastric Cancer. J. Surg. Oncol. 2006, 93 (2), 139–144. 10.1002/jso.20420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black P. C.; Mize G. J.; Karlin P.; Greenberg D. L.; Hawley S. J.; True L. D.; Vessella R. L.; Takayama T. K. Overexpression of Protease-Activated Receptors-1,-2, and −4 (PAR-1, −2, and −4) in Prostate Cancer. Prostate 2007, 67, 743–756. 10.1002/pros.20503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyun E.; Andrade-Gordon P.; Steinhoff M.; Vergnolle N. Protease-Activated Receptor-2 Activation: A Major Actor in Intestinal Inflammation. Gut 2008, 57 (9), 1222–1229. 10.1136/gut.2008.150722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi X.; Gangadharan B.; Brass L. F.; Ruf W.; Mueller B. M. Protease-Activated Receptors (PAR1 and PAR2) Contribute to Tumor Cell Motility and Metastasis. Mol. Cancer Res. 2004, 2 (7), 395–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uusitalo-Jarvinen H.; Kurokawa T.; Mueller B. M.; Andrade-Gordon P.; Friedlander M.; Ruf W. Role of Protease Activated Receptor 1 and 2 Signaling in Hypoxia-Induced Angiogenesis. Arterioscler., Thromb., Vasc. Biol. 2007, 27 (6), 1456–1462. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.142539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Ani B.; Saifeddine M.; Hollenberg M. D. Detection of Functional Receptors for the Proteinase-Activated-Receptor-2-Activating Polypeptide, SLIGRL-NH2, in Rat Vascular and Gastric Smooth Muscle. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 1995, 73 (8), 1203–1207. 10.1139/y95-172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanke T.; Ishiwata H.; Kabeya M.; Saka M.; Doi T.; Hattori Y.; Kawabata A.; Plevin R. Binding of a Highly Potent Protease-Activated Receptor-2 (PAR2) Activating Peptide, [ 3H]2-Furoyl-LIGRL-NH2, to Human PAR2. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2005, 145 (2), 255–263. 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry G. D.; Suen J. Y.; Low H. B.; Pfeiffer B.; Flanagan B.; Halili M.; Le G. T.; Fairlie D. P. A Refined Agonist Pharmacophore for Protease Activated Receptor 2. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2007, 17 (20), 5552–5557. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire J.; Saifeddine M.; Triggle C.; Sun K.; Hollenberg M. 2-Furoyl-LIGRLO-Amide : A Potent and Selective Proteinase- Activated Receptor 2 Agonist. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2004, 309 (3), 1124–1131. 10.1124/jpet.103.064584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollenberg M. D.; Renaux B.; Hyun E.; Houle S.; Vergnolle N.; Saifeddine M.; Ramachandran R. Derivatized 2-Furoyl-LIGRLO-Amide, a Versatile and Selective Probe for Proteinase-Activated Receptor 2: Binding and Visualization. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2008, 326 (2), 453–462. 10.1124/jpet.108.136432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman J.; Flynn A. N.; Tillu D. V.; Zhang Z.; Patek R.; Price T. J.; Vagner J.; Boitano S. Lanthanide Labeling of a Potent Protease Activated Receptor-2 Agonist for Time-Resolved Fluorescence Analysis. Bioconjugate Chem. 2012, 23 (10), 2098–2104. 10.1021/bc300300q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yau M. K.; Suen J. Y.; Xu W.; Lim J.; Liu L.; Adams M. N.; He Y.; Hooper J. D.; Reid R. C.; Fairlie D. P. Potent Small Agonists of Protease Activated Receptor 2. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2016, 7 (1), 105–110. 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.5b00429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y.; Yau M. K.; Kok W. M.; Lim J.; Wu K. C.; Liu L.; Hill T. A.; Suen J. Y.; Fairlie D. P. Biased Signaling by Agonists of Protease Activated Receptor 2. ACS Chem. Biol. 2017, 12 (5), 1217–1226. 10.1021/acschembio.6b01088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Ani B.; Saifeddine M.; Kawabata a.; Renaux B.; Mokashi S.; Hollenberg M. D. Proteinase-Activated Receptor 2 (PAR(2)): Development of a Ligand-Binding Assay Correlating with Activation of PAR(2) by PAR(1)- and PAR(2)-Derived Peptide Ligands. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1999, 290 (2), 753–760. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau C.; Lytle C.; Straus D. S.; DeFea K. A. Apical and Basolateral Pools of Proteinase-Activated Receptor-2 Direct Distinct Signaling Events in the Intestinal Epithelium. AJP Cell Physiol 2011, 300 (1), C113–C123. 10.1152/ajpcell.00162.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollenberg M. D.; Saifeddine M.; Al-Ani B.; Kawabata A. Proteinase-Activated Receptors: Structural Requirements for Activity, Receptor Cross-Reactivity, and Receptor Selectivity of Receptor-Activating Peptides. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 1997, 75 (7), 832–841. 10.1139/y97-110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maryanoff B. E.; Santulli R. J.; McComsey D. F.; Hoekstra W. J.; Hoey K.; Smith C. E.; Addo M.; Darrow A. L.; Andrade-Gordon P. Protease-Activated Receptor-2 (PAR-2): Structure-Function Study of Receptor Activation by Diverse Peptides Related to Tethered-Ligand Epitopes. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2001, 386 (2), 195–204. 10.1006/abbi.2000.2207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boitano S.; Flynn A. N.; Schulz S. M.; Hoffman J.; Price T. J.; Vagner J. Potent Agonists of the Protease Activated Receptor 2 (PAR2). J. Med. Chem. 2011, 54 (5), 1308–1313. 10.1021/jm1013049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.