Abstract

Streptococcus suis is a zoonotic pathogen that causes great economic losses to the swine industry and severe threats to public health. A better understanding of its physiology would contribute to the control of its infections. Although copper is an essential micronutrient for life, it is toxic to cells when present in excessive amounts. Herein, we provide evidence that CopA is required for S. suis resistance to copper toxicity. Quantitative PCR analysis showed that copA expression was specifically induced by copper. Growth curve analyses and spot dilution assays showed that the ΔcopA mutant was defective in media supplemented with elevated concentrations of copper. Spot dilution assays also revealed that CopA protected S. suis against the copper-induced bactericidal effect. Using inductively coupled plasma-optical emission spectroscopy, we demonstrated that the role of CopA in copper resistance was mediated by copper efflux. Collectively, our data indicated that CopA protects S. suis against the copper-induced bactericidal effect via copper efflux.

Keywords: CopA, Streptococcus suis, copper toxicity, copper resistance

1. Introduction

As an important zoonotic pathogen, Streptococcus suis not only causes great economic losses to the swine industry worldwide but is also responsible for severe threats to public health. It leads to meningitis, septicemia, pneumonia, endocarditis, and arthritis in pigs, and is associated with meningitis, septicemia, and streptococcal toxic shock-like syndrome in humans [1,2,3]. Of the 29 serotypes (1–19, 21, 23–25, 27–31, and 1/2) proposed on the basis of the pathogen’s capsular polysaccharides, S. suis serotype 2 (S. suis 2) is generally considered to be the most virulent and the most prevalent in both pigs and humans [4,5,6,7,8,9]. As of 31 December 2013, there have been at least 1642 human cases of S. suis infection, with the majority reported in Vietnam, Thailand, and China [10]. In particular, two large outbreaks of human S. suis infections in China (in 1998 and 2005, respectively) have changed the opinion that this pathogen only causes sporadic human cases [2,9]. S. suis is a persistent threat both to the swine industry and to public health; therefore, a better understanding of the physiology of this agent will undoubtedly contribute to the control of its infections.

Copper, an essential micronutrient for life, functions as a cofactor for a wide variety of enzymes that are involved in various cellular processes [11]. However, an excessive amount of Cu is toxic to cells [11]. Cu has been applied as an antimicrobial agent for thousands of years [12]. Furthermore, the host can utilize Cu toxicity as a mechanism to control bacterial infections [13]. For example, guinea pigs respond to Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection by increasing the concentration of Cu in the lung lesions [14]. Moreover, mutation of the Cu-responsive genes results in attenuated virulence in many pathogens [12,13,15]. As a countermeasure, bacteria have evolved several mechanisms to avoid Cu toxicity, including Cu export, Cu sequestration, and Cu(I) oxidation [12]. Among the numerous Cu exporters that have been described, the Cu exporting P1B-type ATPases are universally present in bacteria [13]. The most extensively studied Cu-responsive system in Gram-positive bacteria is the copYZAB operon of Enterococcus hirae, which encodes two P-type ATPases [16]. Similar Cu-responsive operons have been identified in several streptococcal species, such as Streptococcus mutans [17,18], Streptococcus gordonii [19], Streptococcus pneumoniae [20], and Streptococcus pyogenes [21]. Nevertheless, no such operon or other Cu-responsive mechanism has been reported in S. suis.

In a previous study, we identified two Spx regulators (viz. SpxA1 and SpxA2) in S. suis, and found that SpxA1 modulates oxidative stress tolerance and virulence [22]. Although the copA gene (encoding a Cu-transporting ATPase) is significantly down-regulated in the ΔspxA1 mutant, it appears to play no role in oxidative stress tolerance and virulence in S. suis [23]. Analysis of the genetic organization of copA in S. suis revealed that this gene is not arranged in an operon, making it quite distinct from its homologues in certain species of streptococci [17,18,19,20,21]. Thus, we surmised whether CopA could confer protection against Cu toxicity in S. suis.

In this study, we examined the role of CopA in Cu tolerance in S. suis. Our findings revealed that expression of the copA gene was specifically induced in response to Cu. The ΔcopA mutant exhibited growth inhibition under conditions of excess Cu. Furthermore, we demonstrated that CopA was required for S. suis resistance to the Cu-induced bactericidal effect, and the role of CopA in Cu resistance was mediated by Cu efflux.

2. Results

2.1. S. suis CopA Is a Homologue of the Copper Efflux System

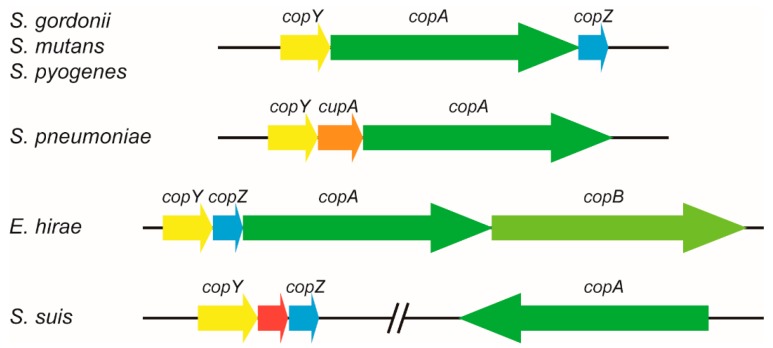

In S. suis 2 strain SC19, CopA encoded by the B9H01_RS06680 locus had 54%, 52%, and 45% amino acid sequence identity to CopA from S. mutans, S. pyogenes, and S. pneumoniae, respectively. In S. mutans, S. gordonii, and S. pyogenes, the genes copY (encoding a Cu-responsive transcriptional regulator), copA, and copZ (encoding a Cu chaperone protein) form a Cu-responsive operon, copYAZ (Figure 1) [17,18,19,21]. In S. pneumoniae, a cupA gene (encoding a hypothetical protein) is present in the operon instead of copZ (Figure 1) [20]. The cop operon of E. hirae consists of four genes that encode CopY, CopZ, CopA, and CopB, respectively (Figure 1) [24]. Unlike the operon organization in these species, the copA gene in S. suis is far away from the copY and copZ genes, and these two genes are separated by a gene that encodes a hypothetical protein (Figure 1). Multiple sequence alignment suggested that CopA from prokaryotes shares several conserved motifs (Figure 2). Furthermore, blastn searches revealed that the copA gene was present in all complete S. suis genomes, with 92% to 100% nucleotide sequence identity (Table 1), indicating that it is highly conserved among a wide range of S. suis strains.

Figure 1.

Genetic organization of the cop genes in several streptococci and Enterococcus hirae. In Streptococcus suis, the copY and copZ genes are separated by a gene (the red arrow) that encodes a hypothetical protein. Arrows indicate the direction of transcription.

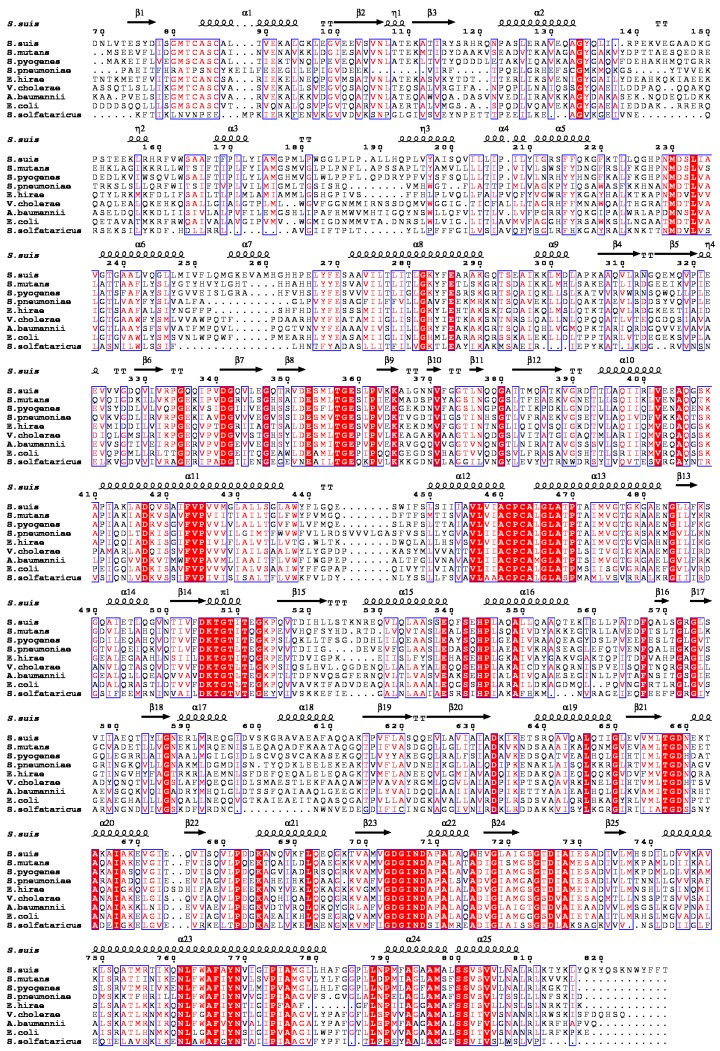

Figure 2.

Multiple sequence alignments of CopA homologues. Identical residues are in white letters with red background; similar residues are in red letters with white background. The modelled structure of Streptococcus suis CopA is shown on the top. α indicates α-helix; β indicates β-sheet; η indicates coil; and T indicates turn. The GenBank accession numbers are as follows: S. suis, WP_012775225.1; Streptococcus mutans, NP_720873.1; Streptococcus pyogenes, AAZ52023.1; Streptococcus pneumoniae, WP_000136284.1; E. hirae, WP_131773415.1; Vibrio cholerae, NP_231846.1; Acinetobacter baumannii, AKA32424.1; Escherichia coli, NP_415017.1; and Sulfolobus solfataricus, WP_009988559.1.

Table 1.

Sequence identity of the copA gene in S. suis.

| S. suis Strains | Locus Tag | Gene Sequence Identity (%) 1 |

|---|---|---|

| LSM102 | A9494_06425 | 100 |

| SC19 | B9H01_06680 | 100 |

| SS2-1 | BVD85_06510 | 100 |

| ZY05719 | ZY05719_06610 | 100 |

| A7 | SSUA7_1228 | 100 |

| P1/7 | SSU1214 | 100 |

| BM407 | SSUBM407_0575 | 100 |

| SC84 | SSUSC84_1247 | 100 |

| S735 | - | 99 |

| GZ1 | SSGZ1_1230 | 99 |

| SS12 | SSU12_1279 | 99 |

| 05ZYH33 | SSU05_1385 | 99 |

| 98HAH33 | SSU98_1400 | 99 |

| SH0104 | - | 97 |

| HA0609 | CR542_03955 | 97 |

| 90-1330 | AN924_03380 | 97 |

| NSUI060 | APQ97_02765 | 97 |

| NSUI002 | AA105_03890 | 97 |

| 05HAS68 | HAS68_0686 | 97 |

| YB51 | YB51_2960 | 97 |

| D9 | SSUD9_0599 | 97 |

| ST3 | SSUST3_0597 | 97 |

| CS100322 | CR541_06915 | 97 |

| T15 | T15_0568 | 97 |

| SC070731 | NJAUSS_1288 | 97 |

| JS14 | SSUJS14_1360 | 97 |

| ST1 | SSUST1_0574 | 96 |

| ISU2812 | A7J09_03980 | 96 |

| SH1510 | DP111_07130 | 96 |

| GZ0565 | BFP66_02780 | 95 |

| DN13 | A6M16_02880 | 95 |

| 6407 | ID09_03115 | 95 |

| TL13 | TL13_0615 | 95 |

| CZ130302 | CVO91_03355 | 95 |

| HN105 | DF184_07440 | 95 |

| HN136 | CWM22_09360 | 95 |

| SRD478 | A7J08_03040 | 92 |

| 1081 | BKM67_07590 | 93 |

| 0061 | BKM66_07040 | 93 |

| D12 | SSUD12_0568 | 92 |

| HA1003 | DP112_07660 | 92 |

| AH681 | CWI26_08525 | 92 |

1 Gene sequence identity is compared with the copA gene of SC19 strain.

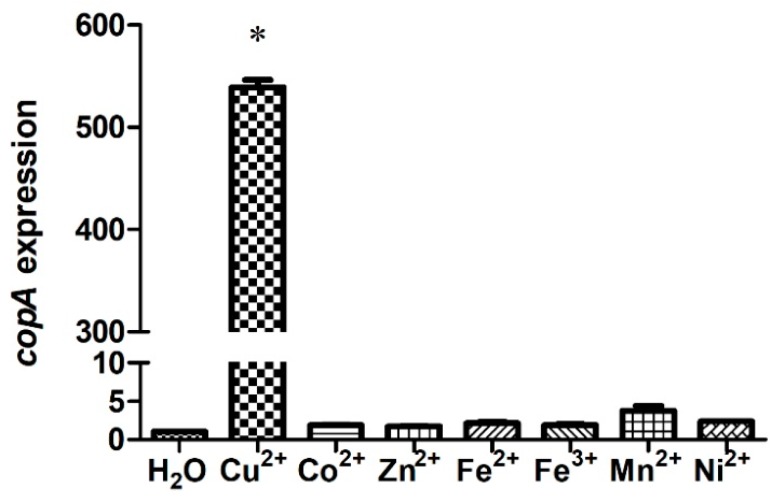

2.2. S. suis Up-regulates copA Expression in Response to Copper

To determine the involvement of S. suis CopA in the bacterial resistance to metal toxicity, the copA expression levels in the presence of elevated levels of Cu or various other metals were tested. The copA expression level of strain SC19 was approximately 530-fold higher in the medium supplemented with 0.5 mM Cu than in the control (Figure 3). In contrast, no significant difference in copA expression was detected when the SC19 strain was treated with other metals (Figure 3). Hence, copA expression was induced specifically in response to Cu.

Figure 3.

copA expression is up-regulated in response to copper. S. suis was grown in the presence of various metals, and the gene expression levels were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCT method with 16S rRNA as the reference gene. Results represent the means and standard deviations (SD) from three biological replicates. * indicates p < 0.05.

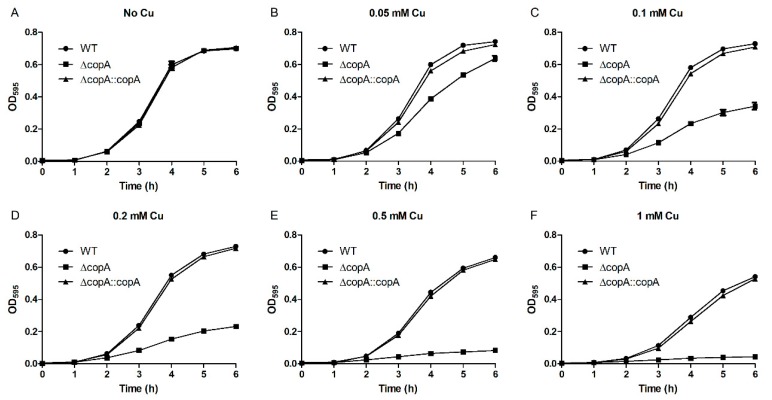

2.3. CopA Is Required for Copper Resistance in S. suis

The wild-type (WT), ΔcopA, and ΔcopA::copA strains were cultured in media supplemented with various concentrations of Cu, and their growth curves were measured to determine the role of CopA in Cu resistance. As seen in Figure 4A, all three strains showed identical growth in the absence of Cu. However, when supplemented with Cu, ΔcopA clearly exhibited impaired growth compared with the WT and ΔcopA::copA strains (Figure 4B–F). Surprisingly, defective ΔcopA growth was observed in the presence of as little as 0.05 mM Cu (Figure 4B), and 0.5 mM Cu almost completely inhibited the mutant strain’s growth (Figure 4E).

Figure 4.

CopA is required for S. suis resistance to copper toxicity in liquid medium. Growth curves of the wildtype (WT), ΔcopA, and ΔcopA::copA strains in the absence (A) and presence of 0.05 mM (B), 0.1 mM (C), 0.2 mM (D), 0.5 mM (E), and 1 mM (F) Cu. The data in the graphs are the means and SD from three wells.

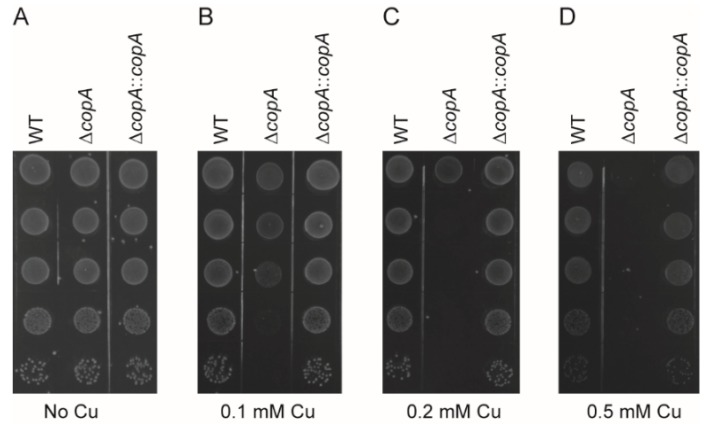

The growth defect phenotype of ΔcopA under Cu excess conditions was also observed on agar plates. The WT, ΔcopA, and ΔcopA::copA strains all formed colonies with high efficiency in the absence of Cu (Figure 5A). In the presence of Cu, however, ΔcopA clearly exhibited a decreased ability to form colonies compared with the WT and ΔcopA::copA strains (Figure 5B–D).

Figure 5.

CopA is involved in S. suis resistance to copper toxicity in agar plates. Spot dilution assays of the WT, ΔcopA, and ΔcopA::copA strains in the absence (A) and presence of 0.1 mM (B), 0.2 mM (C), and 0.5 mM (D) Cu. Overnight cultures of the strains were serially diluted, and 5 μL of each dilution was spotted onto the plates from 10−1 (top) to 10−5 (bottom). The graphs are representative of three independent experiments.

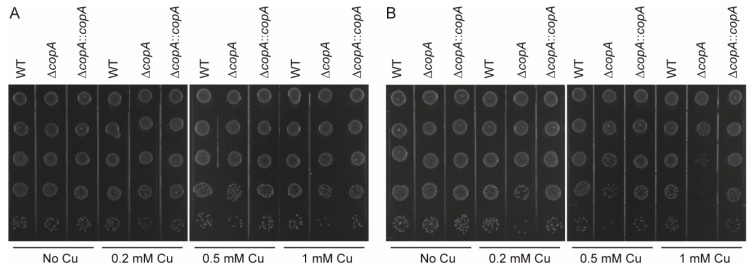

To determine whether Cu is bactericidal or bacteriostatic and to further assess the role of CopA in Cu resistance, the WT, ΔcopA, and ΔcopA::copA strains grown to an OD600 of 0.6 were treated with H2O or various concentrations of Cu, and bacterial survival was analyzed by spot dilution assays. After treatment with Cu for 2 h, ΔcopA formed a smaller number of colonies than did the WT and ΔcopA::copA strains (Figure 6A). The effect was more prominent after 3 h of treatment (Figure 6B). In contrast, the three strains formed a similar number of colonies following treatment with H2O (Figure 6). Thus, Cu is bactericidal to S. suis, and CopA protects the bacterium against this effect.

Figure 6.

CopA protects S. suis against copper-mediated bactericidal effect. The WT, ΔcopA, and ΔcopA::copA strains were grown to an OD600 of 0.6. Each culture was then divided into four equal volumes, which were treated with either varying concentrations of Cu (0.2, 0.5, and 1 mM) or deionized H2O. At 2 h (A) and 3 h (B), aliquots were removed, serially diluted 10-fold up to 10−5 dilution, and 5 μL of each dilution was then spotted onto the plates from 10−1 (top) to 10−5 (bottom). The graphs are representative of three independent experiments.

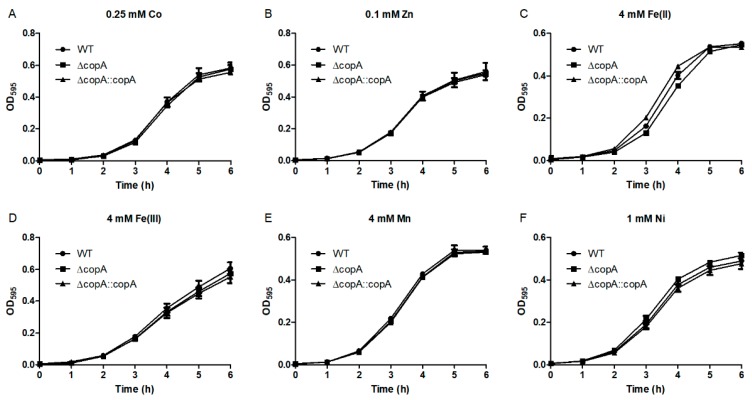

We also investigated the role of CopA in the bacterial resistance to other metals. As seen in Figure 7, ΔcopA displayed no growth inhibition effects in the presence of excess Co, Zn, Fe(II), Fe(III), Mn, or Ni. Thus, CopA is specifically required for Cu resistance in S. suis.

Figure 7.

Growth curves of the WT, ΔcopA, and ΔcopA::copA strains in the presence of various metals. 0.25 mM Co (A); 0.1 mM Zn (B); 4 mM Fe(II) (C); 4 mM Fe(III) (D); 4 mM Mn (E); 1 mM Ni (F).

Taken together, these results indicate that CopA plays an essential role in S. suis resistance to the Cu-induced bactericidal effect.

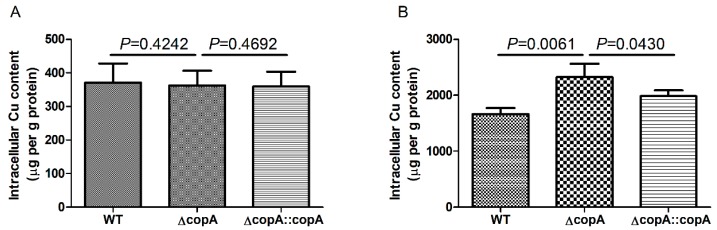

2.4. copA Deletion Leads to Increased Intracellular Accumulation of Copper

To understand the mechanism behind the role of CopA in Cu resistance, the intracellular Cu content of the WT, ΔcopA, and ΔcopA::copA strains grown in the absence or presence of Cu was determined by inductively coupled plasma-optical emission spectroscopy (ICP-OES). When grown in the absence of Cu, the three strains accumulated low and equivalent levels of intracellular Cu (Figure 8A). Following the addition of Cu to the growth medium, a markedly higher level of intracellular Cu was accumulated in all three strains (Figure 8B). However, the intracellular Cu content in ΔcopA was significantly higher than that in the WT and ΔcopA::copA strains (Figure 8B). These results suggest that the role of CopA in Cu resistance is mediated by Cu efflux.

Figure 8.

Levels of intracellular copper in the WT, ΔcopA, and ΔcopA::copA strains. The strains were grown to an OD600 of 0.3, and then treated with either H2O (A) or 0.05 mM Cu (B) for 2 h. The intracellular copper content was analyzed by inductively coupled plasma-optical emission spectroscopy (ICP-OES). Results represent the means and SD from three biological replicates.

3. Discussion

The present work focused on evaluating the role of CopA in S. suis resistance to Cu stress. Our data clearly demonstrated that CopA protects S. suis against Cu toxicity, as based on the following lines of evidence: (i) S. suis CopA shares a high level of identity (approximately 50%) with its homologues from other streptococcal species, all of which are involved in Cu export [17,18,19,20,21]; (ii) S. suis upregulates copA expression in response to Cu; (iii) the ΔcopA mutant exhibits increased sensitivity to Cu stress both in liquid media and on agar plates; (iv) the ΔcopA mutant forms less colonies after treatment with Cu; and (v) addition of Cu to the medium leads to a higher level of intracellular Cu in the ΔcopA mutant.

Generally, streptococcal species possess a Cu-responsive operon which participates in Cu resistance [17,18,19,20,21]. Although the genes (i.e. copY, copA, and copZ) that constitute an operon in other species are present in the genome of S. suis, they are not arranged into an operon. It has been well established that CopA contributes to Cu resistance in a number of bacteria and archaea, such as S. pyogenes [21], Neisseria gonorrhoeae [25], Acinetobacter baumannii [26], and Sulfolobus solfataricus [27]. Likewise, CopA is required for Cu resistance in S. suis. In addition, we showed that treatment with Cu leads to the significantly decreased survival of the ΔcopA mutant, suggesting that Cu is bactericidal to S. suis. This claim is consistent with observations in N. gonorrhoeae [25] and M. tuberculosis [28].

Cu can catalyze the formation of hydroxyl radicals via the Fenton and Haber–Weiss reactions [12,13]. The oxidative damage caused by hydroxyl radical is an important mechanism underlying Cu toxicity [12,13]. Accordingly, the Cu efflux system has been demonstrated to be involved in oxidative stress tolerance in several bacteria [18,26,29]. However, the deletion of copA has been shown to have no effect on S. suis growth under oxidative stress conditions [23]. S. suis possesses multiple regulators and enzymes, such as PerR [30], SpxA1 [22], SrtR [31], superoxide dismutase [32,33], and NADH oxidase [23], to fight against oxidative stress. It is reasonable to speculate that these factors protect ΔcopA against Cu-induced oxidative stress, resulting in the oxidative stress-tolerant phenotype of this mutant.

The involvement of Cu efflux systems in bacterial pathogenesis has been supported by several lines of evidence. Macrophages use Cu as a defense mechanism against M. tuberculosis infection [14]. Furthermore, bacterial virulence is generally attenuated by deletion of the genes that encode the Cu efflux systems [14,20,26]. However, some Cu efflux systems are not required for virulence. For example, several periplasmic proteins are required for Cu tolerance but not for virulence in Vibrio cholerae [34]. Similarly, there is no significant difference in survival times between mice inoculated with the WT strain and those inoculated with the ΔcopA mutant [23]. In line with this finding, a recent study showed that copA expression was significantly down-regulated during S. suis infection of the blood, joint, and heart of piglets [35].

In conclusion, the evidence provided here clearly demonstrates that CopA is involved in Cu tolerance in S. suis. Moreover, the role of CopA in this resistance to Cu-induced bactericidal effect is mediated by Cu efflux.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Bacterial Strains, Plasmids, and Growth Conditions

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 2. The hypervirulent S. suis 2 strain SC19 [36] and its isogenic derivatives were routinely grown at 37 °C in Tryptic Soy Broth supplemented with 10% newborn bovine serum (TSBS) or on Tryptic Soy Agar supplemented with 10% newborn bovine serum (TSAS). Escherichia coli strain DH5α was cultured at 37 °C in Luria–Bertani (LB) broth or on LB agar. Spectinomycin was added to the growth medium when required at 50 and 100 μg/mL for E. coli and S. suis, respectively.

Table 2.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study.

| Strain or Plasmid | Relevant Characteristics | Source or Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| SC19 | Virulent S. suis 2 strain isolated from the brain of a dead pig | [36] |

| ΔcopA | copA deletion mutant of strain SC19 | [23] |

| ΔcopA::copA | Complemented strain of ΔcopA | This study |

| DH5α | Cloning host for recombinant vector | TransGen |

| Plasmids | ||

| pSET4s | Thermosensitive suicide vector; SpcR 1 | [37] |

| pSET4s::CcopA | pSET4s containing copA and its flanking regions | This study |

1 SpcR, spectinomycin resistant.

4.2. Bioinformatic Analysis

Clustal Omega (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalo/) was used for the sequence alignment of S. suis CopA with its homologous proteins. The result was further processed with ESPript 3.0 (http://espript.ibcp.fr/ESPript/ESPript/). Homology modelling of S. suis CopA structure was performed with SWISS-MODEL (https://www.swissmodel.expasy.org/). The presence of the copA gene in various S. suis strains was detected using blastn searches on the NCBI website.

4.3. copA Expression Analysis

S. suis 2 strain SC19 was first grown in TSBS to an OD600 of 0.6. The culture was then divided into eight equal parts, seven of which were supplemented with 0.5 mM CuSO4, 0.25 mM CoSO4, 0.1 mM ZnSO4, 1 mM FeSO4, 1 mM Fe(NO3)3, 1 mM MnSO4, or 1 mM NiSO4, respectively. Deionized water (H2O) was added to the remaining part, which served as the control. These cultures were further incubated for 15 min, following which the bacterial cells were collected for RNA extraction. Total RNA was isolated using the Eastep Super Total RNA Isolation Kit (Promega, Shanghai, China). The RNA integrity was examined by agarose gel electrophoresis, and the RNA concentration was determined using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer. cDNA was generated from 500 ng of RNA using the PrimeScript RT Reagent Kit with gDNA Eraser (TaKaRa, Dalian, China). Quantitative PCR was performed using TB Green Premix Ex Taq II (TaKaRa, Dalian, China) and the primer pair QcopA1/QcopA2 (Table 3) on the StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA, USA). The levels of copA expression were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCT method [38], with 16S rRNA as the reference gene. The differences in gene expression were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni’s post-test.

Table 3.

Primers used in this study.

| Primer | Sequence (5’-3’) 1 | Size (bp) | Target Gene |

|---|---|---|---|

| QcopA1 | AGAGGATAGGGATGAGCAAGATAACT | 148 | an internal region of copA |

| QcopA2 | TTTGTCTGGTCAGCAGCATTTACT | ||

| Q16S1 | TAGTCCACGCCGTAAACGATG | 159 | an internal region of 16S rRNA |

| Q16S2 | TAAACCACATGCTCCACCGC | ||

| L1 | CCCCGTCGACAATGAGGGCCAAAACGTC | 3758 | copA and its flanking regions |

| R2 | CGCCGAATTCACCATCGACCAGCACTGAG | ||

| In1 | TATCACCGAAAGACCACGAC | 629 | an internal region of copA |

| In2 | ATAATGTTTTTGGCGGCAC | ||

| Out1 | GAGGACAAAATCAGGGGCT | 2769/378 | a fragment containing copA |

| Out2 | AGGGAACAGGCTGAAAACC |

1 The bold sequences are restriction sites.

4.4. Construction of the Complementation Strain

The copA gene and its flanking regions were amplified from the S. suis genome using the primer pair L1/R2 (Table 3). After digestion with the Sal I and EcoR I enzymes, the PCR fragment was cloned into pSET4s [37], yielding the pSET4s::CcopA plasmid, which was then electroporated into the ΔcopA mutant [23]. The same procedures used for mutant construction were followed to create the complementation strain (ΔcopA::copA).

4.5. Growth Curve Analyses

Growth curve analyses of the WT, ΔcopA, and ΔcopA::copA strains were performed using various concentrations of CuSO4, CoSO4, ZnSO4, FeSO4, Fe(NO3)3, MnSO4, or NiSO4. Overnight cultures of the strains were diluted 1:100 in TSBS supplemented with various amounts of the individual metals. In the case of FeSO4, trisodium citrate dihydrate was also added to the medium at a concentration of 1 g/L to reduce iron precipitation. The strains were grown at 37 °C in 96-well plates (200 μL/well), and the OD595 values were measured hourly using a CMax Plus plate reader (Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA, USA).

4.6. Spot Dilution Assays

Overnight cultures of the WT, ΔcopA, and ΔcopA::copA strains were serially diluted 10-fold up to 10−5 dilution, and 5 μL of each dilution was then spotted onto TSAS plates supplemented with varying concentrations of CuSO4 (0, 0.1, 0.2, and 0.5 mM). The plates were incubated at 37 °C for 18 h and then photographically documented.

In another assay, overnight cultures of the WT, ΔcopA, and ΔcopA::copA strains were diluted 1:100 in TSBS and grown to an OD600 of 0.6. Each culture was then divided into four equal volumes that were treated with either deionized H2O or varying concentrations of CuSO4 (0.2, 0.5, and 1 mM). At 2 and 3 h, aliquots of the cultures were serially diluted 10-fold up to 10−5 dilution, and 5 μL of each dilution was then spotted onto TSAS plates. The plates were incubated at 37 °C for 18 h and then photographically documented.

4.7. Intracellular Copper Content Analysis

The WT, ΔcopA, and ΔcopA::copA strains were grown in TSBS to an OD600 of 0.3. Each culture was then divided into two equal volumes, which were treated with either deionized H2O or 0.05 mM CuSO4 for 2 h. The cells were harvested and washed three times with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) containing 0.25 M EDTA followed by three times with PBS. The cells were resuspended in 350 μL of PBS, and part of the suspension was used to measure the total protein content with a Bradford Protein Assay Kit (Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China). The remaining 300 μL of the suspension was centrifuged, following which the cells were resuspended in 66% nitric acid and digested for 48 h at 70 °C. Next, the samples were diluted to 2% nitric acid and analyzed for Cu content by ICP-OES at Yangzhou University. The differences in intracellular Cu content were analyzed using the one-tailed unpaired t-test.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Sekizaki (National Institute of Animal Health, Japan) for supplying plasmid pSET4s.

Abbreviations

| WT | wild-type |

| ICP-OES | inductively coupled plasma-optical emission spectroscopy |

| TSBS | Tryptic Soy Broth supplemented with 10% newborn bovine serum |

| TSAS | Tryptic Soy Agar supplemented with 10% newborn bovine serum |

| PBS | phosphate buffered saline |

Author Contributions

C.Z. and M.J. conceived and designed the experiments; C.Z., M.J., T.L., M.G., and L.L. performed the experiments and analyzed the data; C.Z. wrote the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 31802210), China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2018M630615), the Natural Science Foundation of the Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions of China (18KJB230007), and the Open Project of State Key Laboratory of Agricultural Microbiology (AMLKF201804).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Lun Z.R., Wang Q.P., Chen X.G., Li A.X., Zhu X.Q. Streptococcus suis: An emerging zoonotic pathogen. Lancet. Infect. Dis. 2007;7:201–209. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(07)70001-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wertheim H.F., Nghia H.D., Taylor W., Schultsz C. Streptococcus suis: An emerging human pathogen. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2009;48:617–625. doi: 10.1086/596763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Segura M., Zheng H., de Greeff A., Gao G.F., Grenier D., Jiang Y., Lu C., Maskell D., Oishi K., Okura M., et al. Latest developments on Streptococcus suis: An emerging zoonotic pathogen: Part 1. Future Microbiol. 2014;9:441–444. doi: 10.2217/fmb.14.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Higgins R., Gottschalk M., Boudreau M., Lebrun A., Henrichsen J. Description of six new capsular types (29–34) of Streptococcus suis. J. Vet. Diagn Invest. 1995;7:405–406. doi: 10.1177/104063879500700322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hill J.E., Gottschalk M., Brousseau R., Harel J., Hemmingsen S.M., Goh S.H. Biochemical analysis, cpn60 and 16S rDNA sequence data indicate that Streptococcus suis serotypes 32 and 34, isolated from pigs, are Streptococcus orisratti. Vet. Microbiol. 2005;107:63–69. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2005.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Le H.T.T., Nishibori T., Nishitani Y., Nomoto R., Osawa R. Reappraisal of the taxonomy of Streptococcus suis serotypes 20, 22, 26, and 33 based on DNA-DNA homology and sodA and recN phylogenies. Vet. Microbiol. 2013;162:842–849. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2012.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nomoto R., Maruyama F., Ishida S., Tohya M., Sekizaki T., Osawa R. Reappraisal of the taxonomy of Streptococcus suis serotypes 20, 22 and 26: Streptococcus parasuis sp nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Micr. 2015;65:438–443. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.067116-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tohya M., Arai S., Tomida J., Watanabe T., Kawamura Y., Katsumi M., Ushimizu M., Ishida-Kuroki K., Yoshizumi M., Uzawa Y., et al. Defining the taxonomic status of Streptococcus suis serotype 33: The proposal for Streptococcus ruminantium sp nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Micr. 2017;67:3660–3665. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.002204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feng Y., Zhang H., Wu Z., Wang S., Cao M., Hu D., Wang C. Streptococcus suis infection: An emerging/reemerging challenge of bacterial infectious diseases? Virulence. 2014;5:477–497. doi: 10.4161/viru.28595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goyette-Desjardins G., Auger J.P., Xu J., Segura M., Gottschalk M. Streptococcus suis, an important pig pathogen and emerging zoonotic agent-an update on the worldwide distribution based on serotyping and sequence typing. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2014;3:e45. doi: 10.1038/emi.2014.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Samanovic M.I., Ding C., Thiele D.J., Darwin K.H. Copper in Microbial Pathogenesis: Meddling with the Metal. Cell Host Microbe. 2012;11:106–115. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hodgkinson V., Petris M.J. Copper Homeostasis at the Host-Pathogen Interface. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:13549–13555. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R111.316406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ladomersky E., Petris M.J. Copper tolerance and virulence in bacteria. Metallomics. 2015;7:957–964. doi: 10.1039/C4MT00327F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wolschendorf F., Ackart D., Shrestha T.B., Hascall-Dove L., Nolan S., Lamichhane G., Wang Y., Bossmann S.H., Basaraba R.J., Niederweis M. Copper resistance is essential for virulence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci USA. 2011;108:1621–1626. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009261108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Begg S.L. The role of metal ions in the virulence and viability of bacterial pathogens. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2019;47:77–87. doi: 10.1042/BST20180275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Solioz M., Abicht H.K., Mermod M., Mancini S. Response of gram-positive bacteria to copper stress. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2010;15:3–14. doi: 10.1007/s00775-009-0588-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vats N., Lee S.F. Characterization of a copper-transport operon, copYAZ, from Streptococcus mutans. Microbiology. 2001;147:653–662. doi: 10.1099/00221287-147-3-653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Singh K., Senadheera D.B., Levesque C.M., Cvitkovitch D.G. The copYAZ Operon Functions in Copper Efflux, Biofilm Formation, Genetic Transformation, and Stress Tolerance in Streptococcus mutans. J. Bacteriol. 2015;197:2545–2557. doi: 10.1128/JB.02433-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mitrakul K., Loo C.Y., Hughes C.V., Ganeshkumar N. Role of a Streptococcus gordonii copper-transport operon, copYAZ, in biofilm detachment. Oral Microbiol. Immunol. 2004;19:395–402. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.2004.00176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shafeeq S., Yesilkaya H., Kloosterman T.G., Narayanan G., Wandel M., Andrew P.W., Kuipers O.P., Morrissey J.A. The cop operon is required for copper homeostasis and contributes to virulence in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Mol. Microbiol. 2011;81:1255–1270. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07758.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Young C.A., Gordon L.D., Fang Z., Holder R.C., Reid S.D. Copper Tolerance and Characterization of a Copper-Responsive Operon, copYAZ, in an M1T1 Clinical Strain of Streptococcus pyogenes. J. Bacteriol. 2015;197:2580–2592. doi: 10.1128/JB.00127-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zheng C., Xu J., Li J., Hu L., Xia J., Fan J., Guo W., Chen H., Bei W. Two Spx regulators modulate stress tolerance and virulence in Streptococcus suis serotype 2. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e108197. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0108197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zheng C., Ren S., Xu J., Zhao X., Shi G., Wu J., Li J., Chen H., Bei W. Contribution of NADH oxidase to oxidative stress tolerance and virulence of Streptococcus suis serotype 2. Virulence. 2017;8:53–65. doi: 10.1080/21505594.2016.1201256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Solioz M., Stoyanov J.V. Copper homeostasis in Enterococcus hirae. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2003;27:183–195. doi: 10.1016/S0168-6445(03)00053-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Djoko K.Y., Franiek J.A., Edwards J.L., Falsetta M.L., Kidd S.P., Potter A.J., Chen N.H., Apicella M.A., Jennings M.P., McEwan A.G. Phenotypic characterization of a copA mutant of Neisseria gonorrhoeae identifies a link between copper and nitrosative stress. Infect. Immun. 2012;80:1065–1071. doi: 10.1128/IAI.06163-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alquethamy S.F., Khorvash M., Pederick V.G., Whittall J.J., Paton J.C., Paulsen I.T., Hassan K.A., McDevitt C.A., Eijkelkamp B.A. The Role of the CopA Copper Efflux System in Acinetobacter baumannii Virulence. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019;20:575. doi: 10.3390/ijms20030575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vollmecke C., Drees S.L., Reimann J., Albers S.V., Lubben M. The ATPases CopA and CopB both contribute to copper resistance of the thermoacidophilic archaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus. Microbiology. 2012;158:1622–1633. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.055905-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ward S.K., Hoye E.A., Talaat A.M. The global responses of Mycobacterium tuberculosis to physiological levels of copper. J. Bacteriol. 2008;190:2939–2946. doi: 10.1128/JB.01847-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lim S.Y., Joe M.H., Song S.S., Lee M.H., Foster J.W., Park Y.K., Choi S.Y., Lee I.S. cuiD is a crucial gene for survival at high copper environment in Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium. Mol. Cells. 2002;14:177–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang T.F., Ding Y., Li T.T., Wan Y., Li W., Chen H.C., Zhou R. A Fur-like protein PerR regulates two oxidative stress response related operons dpr and metQIN in Streptococcus suis. BMC Microbiol. 2012;12:85. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-12-85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hu Y.L., Hu Q., Wei R., Li R.C., Zhao D., Ge M., Yao Q., Yu X.L. The XRE Family Transcriptional Regulator SrtR in Streptococcus suis Is Involved in Oxidant Tolerance and Virulence. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2019;8:452. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2018.00452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tang Y.L., Zhang X.Y., Wu W., Lu Z.Y., Fang W.H. Inactivation of the sodA gene of Streptococcus suis type 2 encoding superoxide dismutase leads to reduced virulence to mice. Vet. Microbiol. 2012;158:360–366. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2012.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fang L.H., Shen H.X., Tang Y.L., Fang W.H. Superoxide dismutase of Streptococcus suis serotype 2 plays a role in anti-autophagic response by scavenging reactive oxygen species in infected macrophages. Vet. Microbiol. 2015;176:328–336. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2015.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marrero K., Sanchez A., Gonzalez L.J., Ledon T., Rodriguez-Ulloa A., Castellanos-Serra L., Perez C., Fando R. Periplasmic proteins encoded by VCA0261-0260 and VC2216 genes together with copA and cueR products are required for copper tolerance but not for virulence in Vibrio cholerae. Microbiology. 2012;158:2005–2016. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.059345-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Arenas J., Bossers-de Vries R., Harders-Westerveen J., Buys H., Ruuls-van Stalle L.M.F., Stockhofe-Zurwieden N., Zaccaria E., Tommassen J., Wells J.M., Smith H.E., et al. In vivo transcriptomes of Streptococcus suis reveal genes required for niche-specific adaptation and pathogenesis. Virulence. 2019;10:334–351. doi: 10.1080/21505594.2019.1599669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Teng L., Dong X., Zhou Y., Li Z., Deng L., Chen H., Wang X., Li J. Draft Genome Sequence of Hypervirulent and Vaccine Candidate Streptococcus suis Strain SC19. Genome Announc. 2017;5:e01484-16. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.01484-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Takamatsu D., Osaki M., Sekizaki T. Thermosensitive suicide vectors for gene replacement in Streptococcus suis. Plasmid. 2001;46:140–148. doi: 10.1006/plas.2001.1532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Livak K.J., Schmittgen T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]