Abstract

Clostridium difficile induces antibiotic-associated diarrhea due to the release of toxin A (TcdA) and toxin B (TcdB), the latter being its main virulence factor. The epidemic strain NAP1/027 has an increased virulence attributed to different factors. We compared cellular intoxication by TcdBNAP1 with that by the reference strain VPI 10463 (TcdBVPI). In a mouse ligated intestinal loop model, TcdBNAP1 induced higher neutrophil recruitment, cytokine release, and epithelial damage than TcdBVPI. Both toxins modified the same panel of small GTPases and exhibited similar in vitro autoprocessing kinetics. On the basis of sequence variations in the frizzled-binding domain (FBD), we reasoned that TcdBVPI and TcdBNAP1 might have different receptor specificities. To test this possibility, we used a TcdB from a NAP1 variant strain (TcdBNAP1v) unable to glucosylate RhoA but with the same receptor-binding domains as TcdBNAP1. Cells were preincubated with TcdBNAP1v to block cellular receptors, prior to intoxication with either TcdBVPI or TcdBNAP1. Preincubation with TcdBNAP1v blocked RhoA glucosylation by TcdBNAP1 but not by TcdBVPI, indicating that the toxins use different host factors for cell entry. This crucial difference might explain the increased biological activity of TcdBNAP1 in the intestine, representing a contributing factor for the increased virulence of the NAP1/027 strain.

Keywords: Clostridium difficile, NAP1/027 toxin B, receptor binding, frizzled receptors

1. Introduction

Clostridium difficile is a relevant nosocomial pathogen because of its role in antibiotic-associated diarrhea and pseudomembranous colitis. These infections usually occur in hospitalized patients that receive antibiotic treatment. Under these conditions the microbiota is altered, allowing the germination and colonization by C. difficile. Upon proliferation, this bacterium releases two toxins responsible for all the signs and symptoms of the disease, i.e., toxin A (TcdA) and toxin B (TcdB) [1]. Despite some controversy, it has been proposed that TcdB is the main virulence factor of C. difficile [2,3]. These two toxins are multi-domain proteins of high molecular weight from the family of Clostridial Glucosylating Toxin (CGTs) and follow a multi-step strategy to intoxicate eukaryotic cells [4]. As for TcdB, it initially binds to receptors located on the cell surface. Three different receptors have been identified for TcdB of VPI 10463, i.e., the poliovirus receptor-like 3 (PVRL3), chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan 4 (CSPG4), and certain Wnt receptors of the frizzled family (namely, FZD1, FZD2, and FZD7) [5,6,7]. Once the toxin binds to these receptors, it enters the cell by receptor-mediated and clathrin-dependent endocytosis in a compartment that undergoes acidification [8]. This condition triggers a conformational change in the protein, allowing the insertion of hydrophobic domains and the translocation of the N-terminal end to the cytosol. Exposure to inositol hexakisphosphate (InsP6) located in the cytoplasm activates an autoprocessing activity that cleaves the protein and releases the enzymatic domain, which in turn glucosylates, and thus inactivates, members of the family of small GTPases [1,9]. This sequential and concerted action leads to the collapse of the actin cytoskeleton and to a generalized disruption of signaling processes mediated by small GTPases of the Rho subfamily. In the intestine, this cytotoxicity process is manifested by the disruption of the epithelial monolayer and the proinflammatory activation of both epithelial and immune cells [1,10,11].

C. difficile is an extremely variable species, with a core genome reported to be as low as 30% [12,13]. This diversity is reflected in the emergence of strains with varying degrees of virulence, such as the epidemic strain NAP1/027. This strain has been responsible of numerous outbreaks worldwide [14,15,16,17], and its increased virulence has been attributed to a plethora of phenotypic and genotypic characteristics, including increased toxin secretion, a mutation in the PaLoc negative regulator tcdC, production of a binary toxin, increased sporulation, and production of a TcdB with increased biological activity [18,19,20,21].

In this report, we compared TcdB from the reference strain VPI 10463 (TcdBVPI) with the corresponding toxin purified from a NAP1/027 strain (TcdBNAP1) at different steps of the intoxication process. In addition, by using a variant NAP1 TcdB previously reported to differ only in the glucosyltransferase domain (TcdBNAP1v) [22], we found evidence for differences in the exploitation of host cell entry factors between TcdBVPI and TcdBNAP1. Thus, we postulate the existence of different or additional receptors for TcdBNAP1, providing a possible explanation for its increased biological activity.

2. Results

2.1. TcdBNAP1 Has an Increased Biological Activity in the Intestine

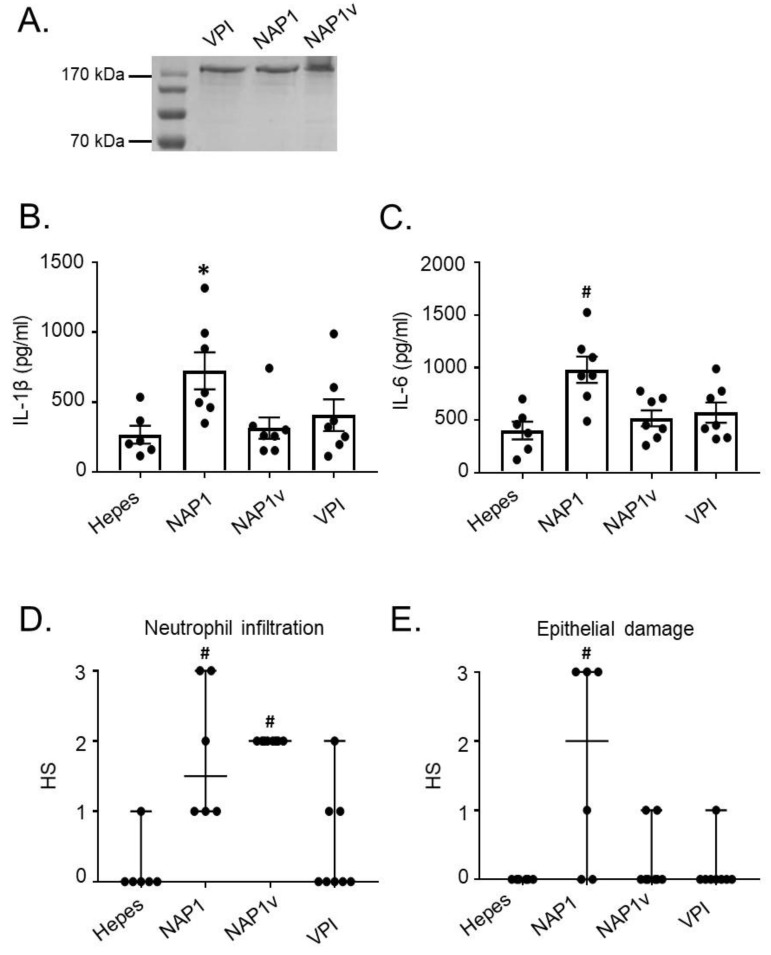

A previous report indicated that TcdBNAP1 possesses an increased biological activity compared to reference TcdB in the zebra fish model [19]. We tested whether the same was true in a mice model. Purified toxins from the hyper-producing strains NAP1, NAP1v, and VPI 10463 were used for all the experiments (Figure 1). Ligated intestinal loops were inoculated with 10 μg of TcdBNAP1, TcdBVPI, or TcdBNAP1v and after 4 h the proinflammatory response was analyzed measuring the levels of ileal cytokines. TcdBNAP1 induced a significantly higher release in the intestinal mucosa of IL-1β and IL-6 than TcdBVPI and TcdBNAP1v (Figure 1). This increased activity of TcdBNAP1 was also seen when epithelial damage was evaluated by histology (Figure 1). In the case of neutrophil migration, both TcdBNAP1 and TcdBNAP1v showed an increased activity when compared to TcdBVPI (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Toxin B (TcdB) from NAP1 induces a higher inflammatory influx and ileal disruption. The in vivo effect of various TcdBs was assayed in a murine ligated ileal loop model. (A) TcdBs were obtained from the supernatants of strains grown in a dialysis system culture and purified by ion-exchange chromatography and gel filtration. The purity of the toxins was assessed after SDS-PAGE by Coomassie staining of a 7.5% gel loaded with 1.5 µg of TcdBVPI (VPI), TcdBNAP1 (NAP1), and TcdBNAP1v (NAP1v). Then, ileal loops were treated for 4 h with 10 μg of purified TcdBVPI (VPI), TcdBNAP1 (NAP1), and TcdBNAP1v (NAP1v); (B,C) The effect of the toxins on inflammatory cytokines was measured; (D,E) Neutrophil infiltration and epithelial damage induced by the toxins was also determined using a histopathological score (HS) scale from 1 (mild) to 3 (severe). Hepes was used as a negative control. Error bars represent means ± SEM (A,B) and median ± range (C,D), n ≥ 5; * p < 0.05 compared to Hepes, # p < 0.05 compared to other groups (One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s correction, Kruskal–Wallis test, and Dunn’s multiple-comparison test).

2.2. The Cytotoxic Potency of TcdBNAP1 Depends on the Cell Line Evaluated

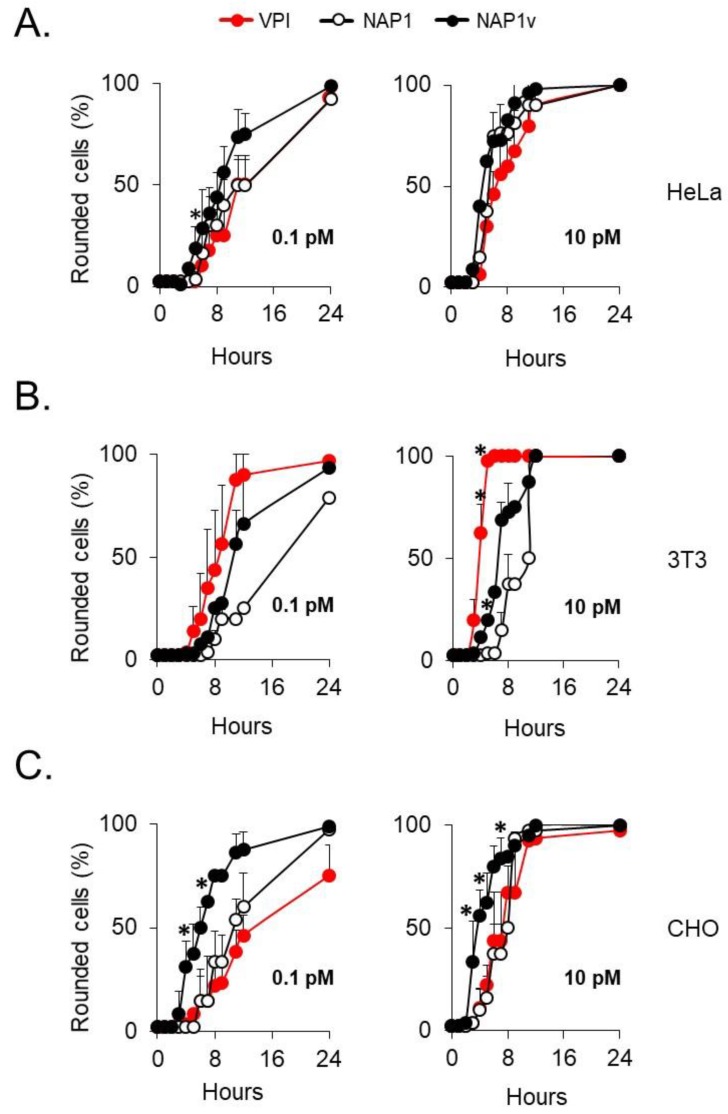

To determine whether the increased biological activity induced by TcdBNAP1 was due to an increased cytotoxic activity, we titrated the toxins in three cell lines. In HeLa cells, the three toxins displayed a similar cytopathic titer (Figure 2A). In contrast, TcdBVPI had a significantly higher cytopathic titer than TcdBNAP1 and TcdBNAP1v in 3T3 fibroblasts (Figure 2B). Interestingly, the opposite was found in CHO cells, in which both TcdBNAP1 and TcdBNAP1v presented a higher cytopathic titer than TcdBVPI (Figure 2C). These results demonstrate that the different cytotoxic potencies depend on the target cell line rather than on an intrinsic characteristic of the toxins.

Figure 2.

Cell rounding of distinct cell lines induced by TcdBs. (A) HeLa, (B) 3T3 fibroblasts, and (C) CHO cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of TcdBVPI (VPI), TcdBNAP1 (NAP1), and TcdBNAP1v (NAP1v). The percentage of round cells in each well was evaluated every hour for a period of 12 h and then after 24 h from the start of the experiment. Error bars represent means ± SD of 100 cells in three independent experiments; * p < 0.05 (One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni´s correction).

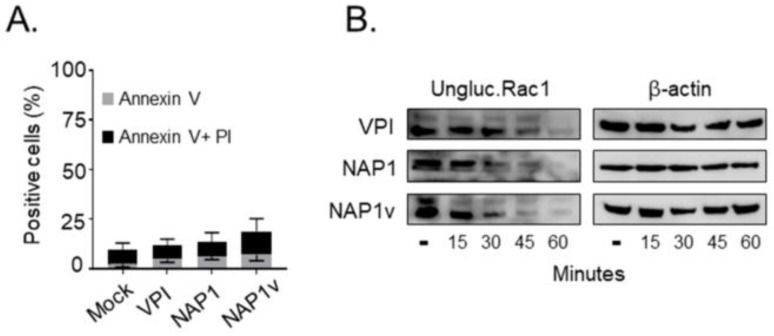

We next evaluated the ability of the three toxins to induce cell death using propidium iodide (PI)/anexin V double staining, which evaluates early apoptotic events (anexin V-positive) and late apoptotic or necrotic cell death (anexin V- and PI-positive). HeLa cells intoxicated with either of the three toxins for 24 h had a similar response, displaying a low percentage of cytotoxicity (below 20%) (Figure 3A). At the toxin concentrations used, the cells already showed a visible cytopathic effect after 2 h of treatment (data not shown), indicating that none of the toxins had an increased ability to induce cell death even if they had fully modified their intracellular substrates with a similar dynamic, as shown by the glucosylation of Rac1 (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Cytotoxicity of TcdBs in HeLa cells. (A) HeLa cells were treated with 100 pM of TcdBVPI (VPI), TcdBNAP1 (NAP1), and TcdBNAP1v (NAP1v) for 24 h. Cytotoxicity was analyzed by flow cytometry using propidium iodide (PI)/anexin V double staining. Control cells were left untreated (mock). Error bars represent means ± SD of three independent experiments; (B) Following the addition of 100 pM of TcdB, the cells were lysed at the indicated time points, and the dynamics of Rac1 glucosylation was monitored by immunoblot with a specific anti-Rac1 antibody that only recognizes the unmodified form of this protein (ungluc.Rac1). Untreated cells (-) were included as a positive control for unglucosylated Rac1, and immunodetection of beta-actin served as a loading control (β-actin). Shown are representative western blot images from three independent experiments.

2.3. TcdBNAP1 and TcdBVPI Possess Similar Enzymatic Activities

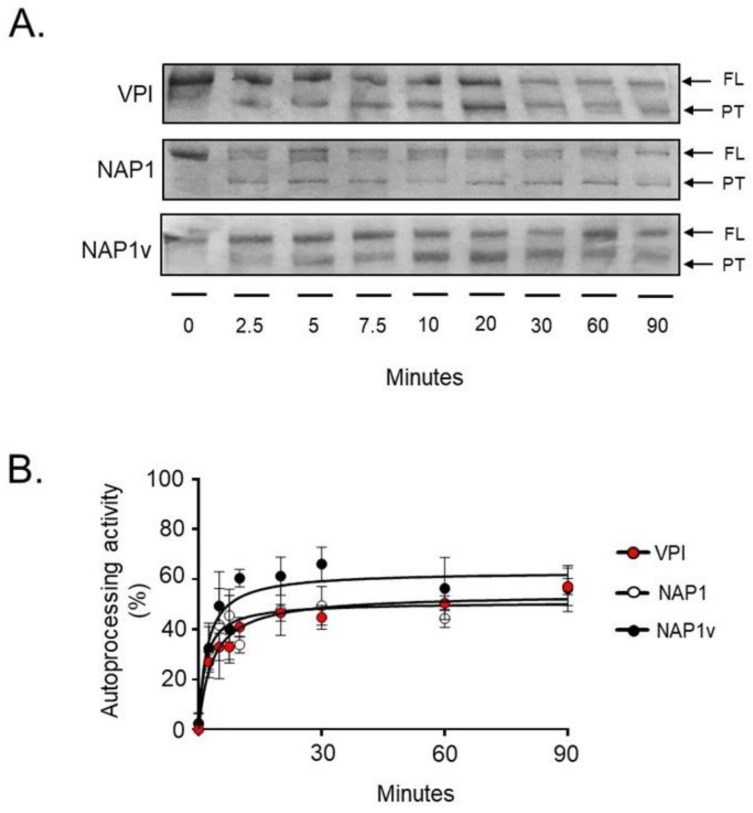

Two enzymatic activities are crucial for the intoxication of cells by TcdB: (1) the autoprocessing activity elicited by InsP6 and (2) the glucosyltransferase activity on small GTPases [4,9,23]. We compared both activities to determine whether differences at this level might explain the increased biological activity of TcdBNAP1. To this end, purified toxins were exposed in vitro to InsP6, and autoproteolysis was followed by detection of a proteolytic product corresponding to residues 544–2366 [24]. Under these conditions, the autoproteolytic event was initiated after only 2.5 min and proceeded efficiently in the three toxins (Figure 4A). Quantitation of the process did not reveal statistical differences among the autoprotolytic activities of the three toxins (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

In vitro autoprocessing of TcdB. The in vitro processing of TcdBVPI (VPI), TcdBNAP1 (NAP1), and TcdBNAP1v (NAP1v) was evaluated in the presence of 10 mM of the co-factor inositol hexakisphosphate (InsP6). The reactions were incubated at 37°C for the indicated times, and toxins or toxin fragments were then detected by Coomassie Blue staining. The enzymatic activity was determined by the presence of full-length (FL) toxin (1–2366), which decreased over time, and processed toxin (544–2366, PT), which increased over time. Shown in (A) is one representative SDS-PAGE gel from three independent experiments; (B) The bands corresponding to the FL toxin and the PT were quantified by densitometry. The autoprocessing activity of each toxin was determined by comparing the relative amounts of both forms of the toxin, and the percentage obtained was plotted using nonlinear regression. Error bars represent means ± SD of three independent experiments.

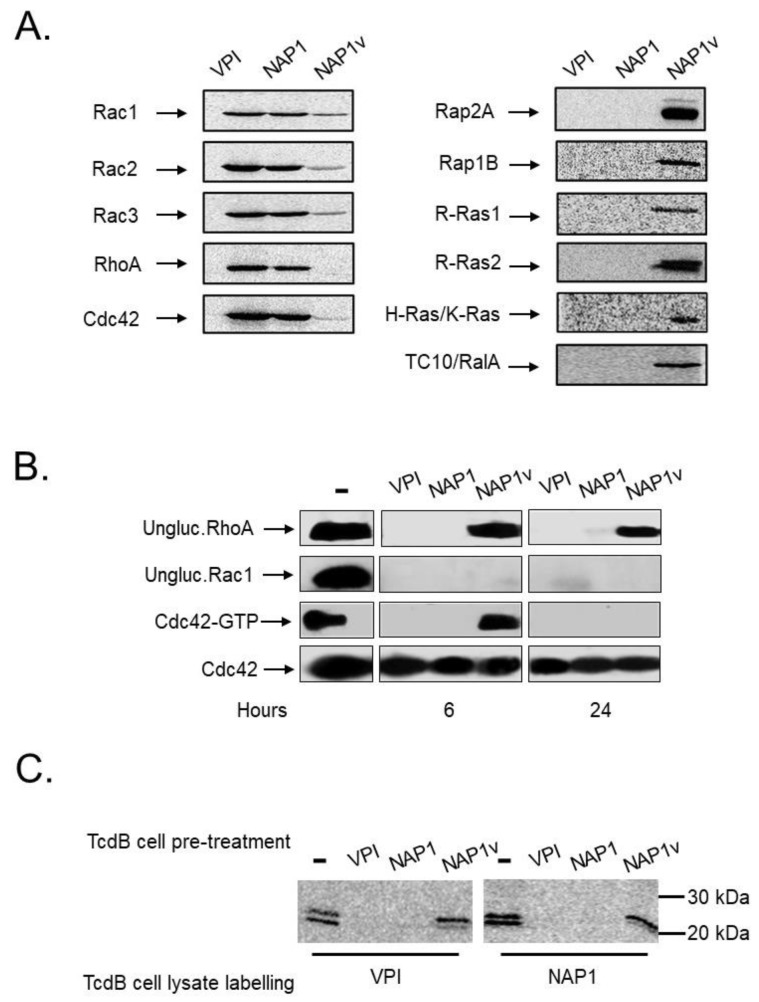

The substrates modified by the three toxins were determined in vitro using recombinant small GTPases and UDP-[14C]glucose. Both TcdBNAP1 and TcdBVPI glucosylated an identical panel of substrates, with preference for Rho GTPases (Rho, Rac, and Cdc42) (Figure 5). On the other hand, TcdBNAP1v glucosylated Ras GTPases (Rap, Ras, and Ral) and to a lower degree, Rac and Cdc42 isoforms (36% and 45% TcdBNAP1v-induced Rac1 glucosylation compared to glucosylation by TcdBVPI and TcdBNAP1, respectively; 23% and 25% TcdBNAP1v-induced Cdc42 glucosylation compared to glucosylation by TcdBVPI and TcdBNAP1 respectively), (Figure 5B), yet, it did not modify RhoA (Figure 5A). These substrate specificities were confirmed ex vivo following the modification of Rho and Rac with the use of glucosylation-sensitive antibodies or Cdc42 in GTPase activation assays (Figure 5B). Since these results suggested that TcdBNAP1 and TcdBVPI modify the same intracellular substrates, we applied a differential glucosylation approach to confirm this. Cells were intoxicated with TcdBNAP1, TcdBNAP1v, or TcdBVPI until a full cytopathic effect (CPE) developed. Lysates were then prepared and used as substrates for radioactive in vitro glucosylation. Both TcdBNAP1 and TcdBVPI were able to radioactively label substrates in the lysates from TcdBNAP1v-intoxicated cells (Figure 5C). However, neither TcdBNAP1 nor TcdBVPI were able to label any GTPase in lysates from cells previously intoxicated by themselves, demonstrating unequivocally that both toxins target the same GTPases ex vivo (Figure 5C).

Figure 5.

Glucosyltransferase activity of TcdBs. (A) The in vitro glucosylation of distinct recombinant GTPases by TcdBVPI (VPI), TcdBNAP1 (NAP1), and TcdBNAP1v (NAP1v) was determined using UDP-[14C] glucose as a co-substrate. The reactions were incubated for 1 h and then subjected to SDS-PAGE. The radiolabeled bands were detected by phosphor imaging; (B) Following the addition of 100 pM of TcdB, HeLa cells were lysed at the indicated times, and the glucosylation of Rac1 and RhoA was monitored by immunoblot with specific anti-Rac1 and anti RhoA antibodies that only recognize the unmodified form of the proteins (ungluc.Rac1 and ungluc.RhoA, respectively). The effect of TcdBs on the activation state of Cdc42 was also evaluated. After intoxication, one part of the lysate was used as a control for the total amount of GTPase, and the rest was incubated with Rho Binding Domain–GST-sepharose beads. Cdc42 was detected by immunoblot with anti-Cdc42 antibodies; (C) HeLa cells were treated with 10 pM of TcdBVPI (VPI), TcdBNAP1 (NAP1), and TcdBNAP1v (NAP1v) for 12 h (TcdB cell pre-treatment). The cells were lysed, and the lysate proteins were glucosylated in vitro by TcdBVPI (VPI) or TcdBNAP1 (NAP1), according to the conditions stated in (A) (TcdB cell lysate labelling). Untreated cells (-) in (B) and (C) were included as a positive control for unmodified or activated proteins.

These results altogether indicate that the difference in biological activity between TcdBNAP1 and TcdBVPI toxins does not reside in intrinsic enzymatic factors.

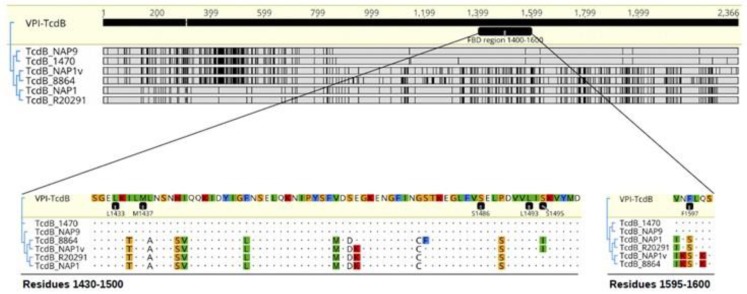

2.4. TcdBNAP1 and TcdBVPI Exploit Different Host Factors for Cell Entry

Prompted by the previous results, we decided to focus on the receptor binding properties of these toxins. We searched for differences at the amino acid level in their frizzled binding domain region (FBD) of various TcdBs (Figure 6), which is involved in the palmitoleic acid (PAM)-mediated interaction between the FBD of TcdBVPI and the frizzled receptor through the cysteine-rich domain of this eukaryotic membrane protein (TcdB-FBD–CRD2) [25]. The results obtained were clearly grouped into two distinguishable clusters (Figure 6; upper part), and considerable sequence variations between TcdBNAP1 and TcdBVPI were obvious within the entire FBD (Figure 6; upper part). Residues L1433, M1437, S1486, L1493, and S1495, which interact with the PAM tail protruding from the CRD2 groove, were conserved (Figure 6). By contrast, TcdBNAP1 and TcdBVPI differed in residue 1597, which, according to a recent 2.5-Å-resolution crystal structure, stabilizes the middle part of PAM and is crucial for PAM binding [25].

Figure 6.

Comparison of TcdB residues involved in frizzled receptor binding. Tree alignment of TcdB sequences of strains VPI 10493, 1470 (reference TcdB variant strain), NAP9 (TcdB variant strain), 8864 (TcdB variant strain), NAP1v, R20291 (NAP1 reference strain), and NAP1. TcdBVPI was used as a reference. Discrepancies are highlighted with black bars or colored-residue letters.

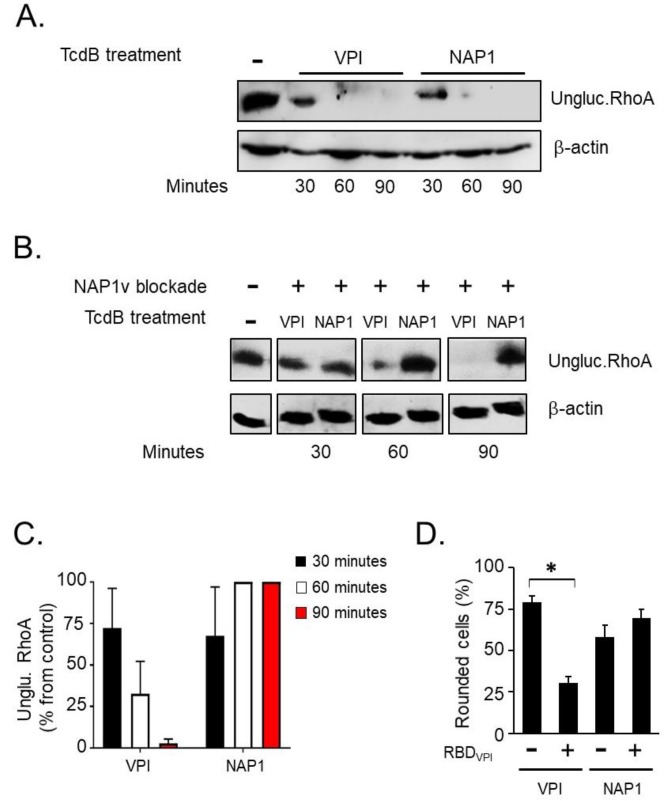

We speculated that TcdBNAP1 has a receptor specificity different from that of TcdBVPI following these observations: (i) we did not find intrinsic differences in the enzymatic activities of the two toxins, (ii) the relative cytotoxic potencies of the toxins depended on the cell line tested, and (iii) the toxins present significant differences at the sequence level in the FBD, as explained above (Figure 6). To test our hypothesis, we took advantage of the sequence similarity of the receptor-binding domains of TcdBNAP1 and TcdBNAP1v and of the fact that the latter does not glucosylate Rho. The receptors were blocked in HeLa cells by preincubation with an excess of TcdBNAP1v at 4 °C to prevent toxin internalization. The cells were then incubated with either TcdBNAP1 or TcdBVPI and switched to 37°C to initiate the intoxication process. At different time points, the successful entrance of the toxins was monitored by western blotting using an antibody that recognizes only unglucosylated RhoA. In non-blocked HeLa cells, RhoA was efficiently modified, with the same dynamics, by both TcdBNAP1 and TcdBVPI (Figure 7A). On the other hand, in cells previously blocked with TcdBNAP1V, RhoA modification was only exerted by TcdBVPI, whereas no glucosylation was detected in TcdBNAP1-intoxicated cells for the duration of the experiment (Figure 7B). This experiment was repeated in 3T3 fibroblasts and Raw 264.7 macrophages with identical results (data not shown). To independently demonstrate that TcdBNAP1 and TcdBVPI use different receptors, we took advantage of a recombinant fragment we used in previous works [26], encompassing residues 1349–1811 of TcdBVPI and referred to as Receptor Binding Domain (RBD). HeLa cells were pre incubated with this fragment for 30 min at 4 °C to block toxin receptors. The cells were then treated with either TcdBNAP1 or TcdBVPI, and the percentage of cells displaying characteristic CPE were monitored. Under these conditions, RBDVPI was able to confer a statistically significant protection from TcdBVPI but not from TcdBNAP1 (Figure 7D), further supporting the notion that both toxins use independent cell entry mechanisms.

Figure 7.

Uptake of TcdB from TcdBNAP1 is blocked by TcdBNAP1v. In order to determine whether the different toxins use the same host cell entry factors, an uptake competition assay was performed in HeLa cells. (A) The cells were treated with 10 pM of TcdBVPI (VPI) or TcdBNAP1 (NAP1) for the indicated times at 37 °C. Following cell lysis, the uptake of each toxin was evaluated by western blot using an antibody that only binds to the unglucosylated form of RhoA GTPase (ungluc.RhoA); (B) The cells were treated with 1 nM of TcdBNAP1v (NAP1v) for 30 min at 4 °C to induce binding of TcdBNAP1v to the cell but not its uptake (NAP1v blockade +). The cells were then treated with 10 pM of TcdBVPI or TcdBNAP1 and incubated for 30, 60, and 90 min at 37 °C (TcdB treatment). Toxin uptake was determined by immunodetection of unmodified RhoA, as stated in (A). Untreated cells (-) were included as a positive control for unglucosylated Rac1, and immunoblot of β-actin served as a loading control (β-actin). Shown are representative western blot images from three independent experiments; (C) The bar graph shows the amount of unglucosylated RhoA in intoxicated cells relative to the unglucosylated RhoA amount in untreated cells, which was set to 100%. Error bars represent means ± SD of three independent experiments; (D) 10 nM of recombinant Receptor Binding Domain (RBDVPI) corresponding to TcdB1349-1811 of VPI 10463 was added to the cells, and these were incubated for 30 min at 4 °C to block toxin receptors. Control cells were mocked-treated with the corresponding volume of buffer and also incubated for 30 min at 4 °C (RBDVPI -). The cells were then treated with 100 pM of TcdBVPI or TcdBNAP1, and the percentage of round cells was evaluated after 60 min as a parameter of full-length toxin uptake. Error bars represent means ± SD of 1000 cells in triplicate samples; * p < 0.05 (Student t test). This experiment is representative of three independent experiments with similar results.

3. Discussion

Early studies from Stabler and colleagues showed that TcdBs from NAP1/027 strains exhibit significant sequence variation when compared to TcdBs produced by historical, non-epidemic strains (e.g., strain 630) [17]. Subsequent work in vitro [27], in the zebra fish model [19], and in mouse intoxication assays [28] suggested that TcdB from C. difficile NAP1/027 strains is more cytotoxic than TcdB from historical strains. Thus, it was hypothesized that a ‘hypertoxic’ TcdB variant might contribute to the increased morbidity and mortality associated with ‘hypervirulent’ C. difficile NAP1/027 strains [28]. Lanis and colleagues suggested that the increased cytotoxic potential of TcdBNAP1 is explained by its ability to enter into target cells more rapidly and at an earlier stage in endocytosis [19] and by the fact that autoprocessing occurs more efficiently in TcdBNAP1 [29].

In the current study, we compared TcdB from the reference strain VPI 10463 (identical to TcdB from the 630 strain) with its TcdB counterparts from a NAP1 and a NAP1v strain [22]. In agreement with previous findings mentioned above, we also observed an increased biological activity of TcdBNAP1 in our mouse ligated intestinal loop model. However, our in vitro intoxication experiments with cultured cells revealed that TcdBNAP1 is not per se more cytotoxic than TcdBVPI. For instance, TcdBVPI was capable of inducing cell rounding in 3T3 cells more efficiently than the TcdBNAP1 equivalent. This contrasts with previous findings from Stabler and colleagues, where it was shown that TcdBNAP1 is more cytotoxic than the reference TcdB in all tested cell lines, including 3T3 cells [27]. The authors used the 630 strain for native preparation of the reference TcdB, which produces an identical TcdB to that of the VPI 10463 strain. It is however of note that, in contrast to the VPI 10453 strain, the 630 strain does not overproduce toxin B [30]. In our hands, native toxin preparations from strain 630 yielded much less TcdB with decreasing activity due to ongoing degradation (data not shown). The latter fact might explain the differing cytotoxic activity of the NAP1 and 630 TcdBs observed by Stabler et al. in their cell intoxication experiments. From our data, we concluded that the difference in in vivo cytotoxicity of TcdBNAP1, TcdBNAP1v, and TcdBVPI equivalents did not result from dissimilar in vitro cytotoxic activity of the toxins.

Accordingly, when we studied the autoprocessing of TcdBVPI, TcdBNAP1, and TcdBNAP1v strains, we did not observe significantly relevant differences in the in vitro InsP6-induced autoprocessing efficiency between the toxins. Moreover, TcdBVPI and TcdBNAP1 presented an identical substrate glucosylation profile and performed glucosylation with the same efficiency. We assume from these findings that the difference in in vivo biological activity of TcdBNAP1 and TcdBVPI in mouse and zebra fish models might not be primarily based on a dissimilar efficacy and/or efficiency of their enzymatic subdomains.

Sequence comparisons between TcdBs from historical and hypervirulent strains revealed that the highest degree in sequence variation is found in the C-terminal part of the toxins [16,19,27]. Since the C-terminus of TcdB is involved in target cell interaction, Stabler and colleagues hypothesized already in 2008 that TcdBNAP1 may have a different binding capacity compared to less virulent TcdB counterparts [17]. To test this hypothesis, we took advantage of TcdBNAP1v which, in contrast to TcdBNAP1 and TcdBVPI, does not modify RhoA in target cells. We preincubated HeLa cells with TcdBNAP1v TcdB to block all cell surface receptors and additional host cell entry factors of the toxin, and, to our surprise, after intoxication with either TcdBNAP1 or TcdBVPI, RhoA modification still occurred in cells intoxicated with TcdBVPI. Thus, TcdBNAP1v blocked host receptors and cell entry of TcdBNAP1 but not of TcdBVPI, indicating differential receptor specificity of the TcdB isoforms. This was further substantiated by the observation that the recombinant receptor binding domain of TcdBVPI was able to protect the cells from TcdBVPI but not from TcdBNAP1.

Cell surface interactions of TcdB are mediated by the combined repetitive oligopeptide (CROP) domain and an additional independent receptor-binding domain preceding the CROP domain (amino acid residues 1349 to 1811) [26,31]. Manse and Baldwin suggested the presence of even two additional receptor-binding domains in front of the CROP domain [32]. In recent years, three host receptors, namely, CSPG4, PVRL3, and FZDs, such as FZD2, were identified as TcdB receptors in the strain VPI 10463 [5,6,7]. Whereas CSPG4 is considered to interact with the CROP domain, PVLR3 and FZD2 bind to the additional receptor-binding domain(s) [6].

Very recently, the crystal structure of a TcdB fragment was solved in complex with the cysteine-rich domain of human FZD2 [25]. The TcdB fragment, referred to by the authors as FZD-binding domain (FBD), covers amino acid residues 1285–1804 and matches nearly exactly the delimitations of the additional receptor-binding domain (residues 1349–1811) discovered previously [26]. Recently, Chung et al. have shown that TcdBNAP1 exhibited only weak binding to FZD2 [33]. In line with this observation, the authors showed that a fragment of TcdBVPI covering amino acid residues 1101–1836 (and which largely overlaps with the FBD described above) was capable of competitively inhibiting TcdBVPI but not TcdBNAP1. Thus, it seems that TcdBNAP1 and TcdBVPI mainly differ in the interaction with FZD2 due to variations in the FBD. Here, we compared the FBD sequences of TcdBNAP1 and TcdBVPI and found that, among other residues, a phenylalanine at position 1597, crucially involved in the interaction of TcdBVPI with FZD2, is not conserved in the TcdBNAP1 equivalent. The modification of FZD-interacting residues in TcdBVPI resulted in a significant reduction of colonic TcdB-induced damage, establishing that FZDs are the main receptors that mediate TcdBVPI intoxication [25]. However, even if this and other amino acids are not conserved in TcdBNAP1, the epithelial damage in the intestine produced by this toxin was severe, which suggests that different receptors mediate the uptake of TcdBNAP1.

Within the C-terminus of TcdBNAP1, the so-called B2’ region (amino acid residues 1651–1852), represents the most variable sequence when compared to the reference TcdB (77% identity) [34,35]. Sequence variations in the B2’ region affect protein–protein interactions within TcdB and the exposure of neutralizing epitopes [34]. Intriguingly, a peptide spanning 19 amino acids in the B2’ region (amino acid residues 1769–1787, termed PepB2) was capable of inhibiting cytotoxicity caused by NAP1/027 and reference TcdB by disrupting cell binding due to the interaction with the CROP domain of the toxins. In contrast, the analogous peptide deriving from reference TcdB (PepB1) did not exhibit these inhibitory effects [36].

Taken together, our findings presented here support a model where TcdBNAP1 and TcdBVPI utilize different or additional host receptors for cell entry, most likely as a result of sequence alterations in the FBD. The changed receptor specificity of TcdBNAP1 might have an influence on the cell tropism of the toxin, resulting in the increased virulence potential observed in vivo. Our data do not exclude that additional factors, such as the differences in the B2’ region mentioned above or sequence variations in the CROP domain, contribute to the increased in vivo cytotoxicity of TcdBNAP1.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. C. difficile Strains and TcdB Sequence Analysis

In a previous study at the Laboratorio de Investigación de Bacteriología Anaerobia (LIBA) from the University of Costa Rica, strains NAP1 and NAP1v were isolated from stool samples following established protocols [22,37].

TcdB sequences from strains VPI 10493 (GenBank: MUJV01000001.1), 1470 (GenBank: Z23277.1), R20291 (NAP1, GenBank: FN545816.1), LIBA-5757 (NAP1v) (GenBank: NZ_LJCM00000000.1), and 8864 (GenBank: AJ011301.1) were extracted manually from WGS or directly from Genbank and aligned with MUSCLE using 100 iterations and default parameters. These alignments were transformed into dendrograms using PhyML. Thereafter, TcdBVPI was selected as a reference, and discrepancies to it in the 1430–1600 region were highlighted with vertical black bars or colored residue letters using Geneious R11.

4.2. Native TcdB Purification and Recombinant Receptor Binding Domain Purification

TcdB was obtained from supernatants of strains grown in a dialysis system culture for 72 h in brain heart infusion broth (Difco, BD Life Sciences, Heidelberg, Germany) and purified as described previously [23]. The toxin was purified by anion-exchange chromatography followed by gel filtration (GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL, USA), and positive fractions were pooled and concentrated in Hepes buffer by ultrafiltration with a 100 kDa membrane. Proteins were quantified using the Bradford method (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA), and purity was assessed by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie staining. Final toxin identification was determined through mass spectrometry (LC–MS/MS), and only TcdB peptides were identified (not shown). Different toxin preparations of each TcdB were used for the various experiments and their replicates.

The RBD, comprising residues 1349–1811, from strain VPI 10463 was purified from Bacillus megaterium as previously described [26]. The C-terminal HIS-tagged fragment was purified by nickel affinity chromatography, and purity was assessed by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie staining.

4.3. Cultivation of Cells and Preparation of Cell Lysates

HeLa cells (ATCC CCL-2), 3T3 fibroblasts (ATCC CCL-163), and Chinese hamster ovarian (CHO) cells (kindly provided by Dr. Eugenia Corrales, University of Costa Rica, San José, Costa Rica) were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 5 mM L-glutamine, penicillin (100 U/mL), and streptomycin (100 μg/mL). The cells were grown under humidified conditions with 5% CO2 and, unless indicated, they were incubated at 37 °C.

Cell lysates were prepared by washing the cells with PBS and lysing with precipitation buffer (1% Triton X-100, 0.1% SDS, 0.3% NonidetP-40, 500 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 50 mM Tris, pH 7.2). Lysates were centrifuged at 21,000× g for 10 min, and protein concentration was determined using the Bradford method (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA).

4.4. Murine Ileal Loop Model

Animal experimental procedures were approved by the University of Costa Rica Animal Care and Use Committee through CICUA 01-12 and CICUA 07-13 according to Law 7451: Bienestar de los animales, 26668-MICIT. Male Swiss mice, 20 to 25 g of weight, were subjected to fasting overnight and anesthetized with ketamine (60 mg/kg of body weight) and xylazine (5 mg/kg). Then, 10 µg of each toxin or Hepes control solution was injected into an ileal, loop following established protocols. The mice were sacrificed 4 h after inoculation, and the concentrations of the proinflammatory cytokines IL-1β and IL-6 in ileal tissue were determined [38]. The tissues were macerated in 1× PBS (pH 7.0), and cytokine concentration in the homogenates was determined by commercial ELISA, according to the instructions of the manufacturer (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA). Intestinal sections were also fixed in formalin and stained with hematoxylin and eosin for histopathological evaluation according to previous protocols [38]. The samples were evaluated for the severity of epithelial damage and neutrophil infiltration using a histopathological score (HS) scale ranging from 0 (absence of alterations) to 3 (severe).

4.5. Cytotoxicity Assays

Confluent HeLa cells, 3T3 fibroblasts, and CHO cells grown in 96-well plates were intoxicated with 0.1 and 10 pM of TcdB from the different strains. The percentage of round cells in each well was evaluated every hour for a period of 12 h and then at 24 h.

For the cell death assay, confluent HeLa cells grown in 24-well plates were intoxicated with 100 pM of each toxin. Cytotoxicity was evaluated after 24 h of treatment. The cells were then harvested, washed in 1× PBS and resuspended in 100 µL 1× annexin binding buffer (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA). Afterwards, 2 µL of Alexa Fluor 488 annexin V and 1 µL 100 mg/mL PI working solution (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA) were added to the resuspended cells. After 15 min, the stained cells were analyzed by flow cytometry using a Guava easyCyte Mini (Merck Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA). The percentage of stained cells was determined with FLOWJO, LLC Data analysis software.

4.6. Rac1 and RhoA Glucosylation

Confluent HeLa cells grown in six-well plates were intoxicated with 100 pM of the corresponding toxins. Cell lysates were obtained at the indicated time points, and lysate proteins were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE and then transferred onto a PVDF membrane for western blotting. Rac1 and RhoA glucosylation were determined with monoclonal antibodies that do not recognize the modified isoforms, anti-Rac1 (clone 102; BD Transduction Laboratories, Franklin Lakes, NJ) and anti-RhoA (ab54835, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), respectively. For Rac1 glucosylation dynamics, β-actin was detected using rabbit anti-actin (A2066; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA).

4.7. In Vitro Glucosyltranferase Activity of TcdBs

A radioactive assay to determine the in vitro activity of each TcdB was performed as previously described [24]. For this, 10 µM of UDP-[14C]glucose, 10 µM of purified recombinant GST–GTPase, and 10 nM of each TcdB were mixed in glucosylation buffer (50mM HEPES, 100mM KCl; 2mM MgCl2, and 1mM MnCl2, pH 7.5). After 1 h of incubation at 37 °C, the reaction was stopped with loading buffer. Radiolabelled proteins were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE and visualized by autoradiography using a phosphorimager (GE Healthcare, Freiburg, Germany).

For the differential glucosylation assay, HeLa cells were treated with 10 pM of the corresponding TcdB for 12 h. Lysate proteins were used as substrates in a radioactive assay, following the conditions described above.

4.8. Ex vivo GTPase Activation Assay

The TcdB ability to inactivate Cdc42 was determined in HeLa cells grown in six-well plates. The cells were treated with 100 pM of each toxin for the indicated times. Cell lysates were centrifuged at 20,000× g for 1 min, and 20 μL were separated as a control for total amount of GTPase. The lysates were incubated with previously purified GST-tagged Rho binding domain coupled to glutathione-Sepharose beads. After 1 h of incubation at room temperature, the activated proteins were pulldown by centrifugation with the GST fusion effector protein. The proteins were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE and then transferred onto a PVDF membrane for western blotting. Cdc42 was detected using anti-Cdc42 antibodies (ab41429, Abcam, Cambridge, UK).

4.9. In Vitro Cleavage Assay

The in vitro autoprocessing activity of TcdBs was performed in a 20 uL reaction with 200 nM of toxin, cleavage buffer (150 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris pH 7.4), and 10 mM InsP6 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) [23]. The reaction was incubated for 0, 2.5, 5, 7.5, 10, 20, 30, 60, and 90 min at 37 °C. The reaction was stopped by addition of loading buffer and boiling at 95 °C for 5 min. The samples were separated by 7.5% SDS-PAGE and then analyzed by Coomassie staining. The activity of each toxin was quantified by comparing the densities of the bands of full-length and processed protein using Image J software (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA). The data were plotted using nonlinear regression and in GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA [29].

4.10. Uptake Competition Assay

Prior to blockade and intoxication, confluent HeLa cells were incubated at 4 °C for 30 min. For NAP1v blockade, 1 nM of TcdBNAP1v was added to the precooled cells. After incubation for 30 min at 4 °C, the cells were treated with 10 pM of TcdBVPI or TcdBNAP1 and incubated at 37 °C. Cell lysates were obtained at the indicated time points, and lysate proteins were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE and then transferred onto a PVDF membrane for western blotting. RhoA glucosylation by TcdBVPI and TcdBNAP1 was determined with a monoclonal antibody that does not recognize the modified isoform, anti-RhoA (ab54835, Abcam, Cambridge, UK); β-actin was detected using rabbit anti-actin (A2066; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). For the receptor binding domain blockade, 100 molar excess of recombinant toxin fragment was added to the cells. After incubation for 30 min at 4 °C, the cells were treated with 100 pM of TcdBVPI or TcdBNAP1 and incubated at 37 °C. The percentage of round cells in each well was evaluated after 60 min.

Acknowledgments

We thank Klaus Aktories (Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg) for fruitful discussions and for providing laboratory material and recombinant small GTPases.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.L.-U., C.R., P.P., and E.C.-O.; Formal analysis, D.L.-U., C.Q.-G., C.R., P.P., and E.C.-O.; Methodology, D.L.-U., J.O.-A., Y.C.-M., A.R.-M., A.V.-J., S.O., C.Q.-G., and C.R.; Writing—original draft, D.L.-U., P.P., and E.C.-O.; Writing—review & editing, D.L.-U., C.Q.-G., C.R., P.P. ,and E.C.-O.

Funding

This research was funded by Vicerrectoría de Investigación from Universidad de Costa Rica, grant numbers 803-B8-117, 803-B7-183, B7-158, and FEES-CONARE grant number 803-B6-657.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Key Contribution

Toxin B from the C. difficile epidemic strain NAP1/027 presents a receptor binding specificity different from that of Toxin B from classic strains, a factor that might explain its increased biological activity.

References

- 1.Voth D.E., Ballard J.D. Clostridium difficile toxins: Mechanism of action and role in disease. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2005;18:247–263. doi: 10.1128/CMR.18.2.247-263.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carter G.P., Chakravorty A., Pham Nguyen T.A., Mileto S., Schreiber F., Li L., Howarth P., Clare S., Cunningham B., Sambol S.P., et al. Defining the roles of TcdA and TcdB in localized gastrointestinal disease, systemic organ damage, and the host response during Clostridium difficile Infections. mBio. 2015;6:e00551-15. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00551-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lyras D., O’Connor J.R., Howarth P.M., Sambol S.P., Carter G.P., Phumoonna T., Poon R., Adams V., Vedantam G., Johnson S., et al. Toxin B is essential for virulence of Clostridium difficile. Nature. 2009;458:1176–1179. doi: 10.1038/nature07822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jank T., Aktories K. Structure and mode of action of clostridial glucosylating toxins: The ABCD model. Trends Microbiol. 2008;16:222–229. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2008.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.LaFrance M.E., Farrow M.A., Chandrasekaran R., Sheng J., Rubin D.H., Lacy D.B. Identification of an epithelial cell receptor responsible for Clostridium difficile TcdB-induced cytotoxicity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:7073–7078. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1500791112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tao L., Zhang J., Meraner P., Tovaglieri A., Wu X., Gerhard R., Zhang X., Stallcup W.B., Miao J., He X., et al. Frizzled proteins are colonic epithelial receptors for C. difficile toxin B. Nature. 2016;538:350–355. doi: 10.1038/nature19799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yuan P., Zhang H., Cai C., Zhu S., Zhou Y., Yang X., He R., Li C., Guo S., Li S., et al. Chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan 4 functions as the cellular receptor for Clostridium difficile toxin B. Cell Res. 2015;25:157–168. doi: 10.1038/cr.2014.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Papatheodorou P., Zamboglou C., Genisyuerek S., Guttenberg G., Aktories K. Clostridial glucosylating toxins enter cells via clathrin-mediated endocytosis. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e10673. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reineke J., Tenzer S., Rupnik M., Koschinski A., Hasselmayer O., Schrattenholz A., Schild H., von Eichel-Streiber C. Autocatalytic cleavage of Clostridium difficile toxin B. Nature. 2007;446:415–419. doi: 10.1038/nature05622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jose S., Madan R. Neutrophil-mediated inflammation in the pathogenesis of Clostridium difficile infections. Anaerobe. 2016;41:85–90. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2016.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xu H., Yang J., Gao W., Li L., Li P., Zhang L., Gong Y.-N., Peng X., Xi J.J., Chen S., et al. Innate immune sensing of bacterial modifications of Rho GTPases by the pyrin inflammasome. Nature. 2014;513:237–241. doi: 10.1038/nature13449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dingle K.E., Griffiths D., Didelot X., Evans J., Vaughan A., Kachrimanidou M., Stoesser N., Jolley K.A., Golubchik T., Harding R.M., et al. Clinical Clostridium difficile: Clonality and pathogenicity locus diversity. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e19993. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Knight D.R., Elliott B., Chang B.J., Perkins T.T., Riley T.V. Diversity and evolution in the genome of Clostridium difficile. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2015;28:721–741. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00127-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.He M., Miyajima F., Roberts P., Ellison L., Pickard D.J., Martin M.J., Connor T.R., Harris S.R., Fairley D., Bamford K.B., et al. Emergence and global spread of epidemic healthcare-associated Clostridium difficile. Nat. Genet. 2013;45:109–113. doi: 10.1038/ng.2478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lopez-Urena D., Quesada-Gomez C., Miranda E., Fonseca M., Rodriguez-Cavallini E. Spread of epidemic Clostridium difficile NAP1/027 in Latin America: Case reports in Panama. J. Med. Microbiol. 2014;63:322–324. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.066399-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sebaihia M., Wren B.W., Mullany P., Fairweather N.F., Minton N., Stabler R., Thomson N.R., Roberts A.P., Cerdeño-Tárraga A.M., Wang H., et al. The multidrug-resistant human pathogen Clostridium difficile has a highly mobile, mosaic genome. Nat. Genet. 2006;38:779–786. doi: 10.1038/ng1830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stabler R.A., Dawson L.F., Phua L.T.H., Wren B.W. Comparative analysis of BI/NAP1/027 hypervirulent strains reveals novel toxin B-encoding gene (tcdB) sequences. J. Med. Microbiol. 2008;57:771–775. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.47743-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Akerlund T., Persson I., Unemo M., Noren T., Svenungsson B., Wullt M., Burman L.G. Increased sporulation rate of epidemic Clostridium difficile type 027/NAP1. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2008;46:1530–1533. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01964-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lanis J.M., Barua S., Ballard J.D. Variations in TcdB activity and the hypervirulence of emerging strains of Clostridium difficile. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1001061. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matamouros S., England P., Dupuy B. Clostridium difficile toxin expression is inhibited by the novel regulator TcdC: TcdC inhibits C. difficile toxin expression. Mol. Microbiol. 2007;64:1274–1288. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05739.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Warny M., Pepin J., Fang A., Killgore G., Thompson A., Brazier J., Frost E., McDonald L.C. Toxin production by an emerging strain of Clostridium difficile associated with outbreaks of severe disease in North America and Europe. Lancet. 2005;366:1079–1084. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67420-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Quesada-Gómez C., López-Ureña D., Chumbler N., Kroh H.K., Castro-Peña C., Rodríguez C., Orozco-Aguilar J., González-Camacho S., Rucavado A., Guzmán-Verri C., et al. Analysis of TcdB proteins within the hypervirulent Clade 2 reveals an Impact of RhoA glucosylation on Clostridium difficile proinflammatory activities. Infect. Immun. 2016;84:856–865. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01291-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pruitt R.N., Chambers M.G., Ng K.K.-S., Ohi M.D., Lacy D.B. Structural organization of the functional domains of Clostridium difficile toxins A and B. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:13467–13472. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002199107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Genisyuerek S., Papatheodorou P., Guttenberg G., Schubert R., Benz R., Aktories K. Structural determinants for membrane insertion, pore formation and translocation of Clostridium difficile toxin B: Pore formation of C. difficile toxin B. Mol. Microbiol. 2011;79:1643–1654. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07549.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen P., Tao L., Wang T., Zhang J., He A., Lam K., Liu Z., He X., Perry K., Dong M., et al. Structural basis for recognition of frizzled proteins by Clostridium difficile toxin B. Science. 2018;360:664–669. doi: 10.1126/science.aar1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schorch B., Song S., van Diemen F.R., Bock H.H., May P., Herz J., Brummelkamp T.R., Papatheodorou P., Aktories K. LRP1 is a receptor for Clostridium perfringens TpeL toxin indicating a two-receptor model of clostridial glycosylating toxins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:6431–6436. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1323790111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stabler R.A., He M., Dawson L., Martin M., Valiente E., Corton C., Lawley T.D., Sebaihia M., Quail M.A., Rose G., et al. Comparative genome and phenotypic analysis of Clostridium difficile 027 strains provides insight into the evolution of a hypervirulent bacterium. Genome Biol. 2009;10:R102. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-9-r102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lanis J.M., Heinlen L.D., James J.A., Ballard J.D. Clostridium difficile 027/BI/NAP1 encodes a hypertoxic and antigenically variable form of TcdB. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003523. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lanis J.M., Hightower L.D., Shen A., Ballard J.D. TcdB from hypervirulent Clostridium difficile exhibits increased efficiency of autoprocessing: Autoproteolysis of TcdBHIST and TcdBHV. Mol. Microbiol. 2012;84:66–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2012.08009.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Merrigan M., Venugopal A., Mallozzi M., Roxas B., Viswanathan V.K., Johnson S., Gerding D.N., Vedantam G. Human hypervirulent Clostridium difficile strains exhibit increased sporulation as well as robust toxin production. J. Bacteriol. 2010;192:4904–4911. doi: 10.1128/JB.00445-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Papatheodorou P., Song S., López-Ureña D., Witte A., Marques F., Ost G.S., Schorch B., Chaves-Olarte E., Aktories K. Cytotoxicity of Clostridium difficile toxins A and B requires an active and functional SREBP-2 pathway. FASEB J. 2018;33:4883–4892. doi: 10.1096/fj.201801440R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Manse J.S., Baldwin M.R. Binding and entry of Clostridium difficile toxin B is mediated by multiple domains. FEBS Lett. 2015;589:3945–3951. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2015.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chung S.-Y., Schöttelndreier D., Tatge H., Fühner V., Hust M., Beer L.-A., Gerhard R. The conserved Cys-2232 in Clostridioides difficile toxin B modulates receptor binding. Front. Microbiol. 2018;9:2314. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Larabee J.L., Krumholz A., Hunt J.J., Lanis J.M., Ballard J.D. Exposure of neutralizing epitopes in the carboxyl-terminal domain of TcdB Is altered by a proximal hypervariable region. J. Biol. Chem. 2015;290:6975–6985. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.612184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hunt J.J., Larabee J.L., Ballard J.D. Amino acid differences in the 1753-to-1851 region of TcdB influence variations in TcdB1 and TcdB2 cell entry. mSphere. 2017;2:e00268-17. doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00268-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Larabee J.L., Bland S.J., Hunt J.J., Ballard J.D. Intrinsic toxin-derived peptides destabilize and inactivate Clostridium difficile TcdB. mBio. 2017;8:e00503-17. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00503-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Quesada-Gomez C., Rodriguez C., del Mar Gamboa-Coronado M., Rodriguez-Cavallini E., Du T., Mulvey M.R., Villalobos-Zuniga M., Boza-Cordero R. Emergence of Clostridium difficile NAP1 in Latin America. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2010;48:669–670. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02196-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Quesada-Gómez C., López-Ureña D., Acuña-Amador L., Villalobos-Zúñiga M., Du T., Freire R., Guzmán-Verri C., del Mar Gamboa-Coronado M., Lawley T.D., Moreno E., et al. Emergence of an outbreak-associated Clostridium difficile variant with increased virulence. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2015;53:1216–1226. doi: 10.1128/JCM.03058-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]