Abstract

Background

Psychosocial risks during pregnancy impact maternal health in resource-limited settings, and HIV-positive women often bear a heavy burden of these factors. This study sought to use network modeling to characterize co-occurring psychosocial risks to maternal and child health among at-risk pregnant women.

Methods

Two hundred pregnant HIV-positive women attending antenatal care in South Africa were enrolled. Measured risk factors included younger age, low income, low education, unemployment, unintended pregnancy, distress about pregnancy, antenatal depression, internalized HIV stigma, violence exposure, and lack of social support. Network analysis between risk factors was conducted in R using mixed graphical modeling. Centrality statistics were examined for each risk node in the network.

Results

In the resulting network, unintended pregnancy was strongly tied to distress about pregnancy. Distress about pregnancy was most central in the network and was connected to antenatal depression and HIV stigma. Unintended pregnancy was also associated with lack of social support, which was itself linked to antenatal depression, HIV stigma, and low income. Finally, antenatal depression was connected to violence exposure.

Conclusions

Our results characterize a network of psychosocial risks among pregnant HIV-positive women. Distress about pregnancy emerged as central to this network, suggesting that unintended pregnancy is particularly distressing in this population and may contribute to further risks to maternal health, such as depression. Prevention of unintended pregnancies and interventions for coping with unplanned pregnancies may be particularly useful where multiple risks intersect. Efforts addressing single risk factors should consider an integrated, multilevel approach to support women during pregnancy.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03069417

Keywords: South Africa, Network analysis, Syndemic, Pregnancy, Perinatal mental health, Depression

Introduction

Across the world, pregnancy is a critical period for maternal and child health (MCH). Extensive literature has found that MCH outcomes are negatively impacted by a variety of risk factors experienced by mothers during pregnancy, including poverty [1, 2], lack of social support [3], exposure to partner violence [4], and depression [5–7], as well as young age [8]. Prior evidence also suggests that these psychosocial risks do not occur independently; for example, poverty has been associated with younger age at childbearing [9], while exposure to partner violence and lack of social support have each been linked to perinatal depression [10, 11]. In order to guide effective MCH interventions, there is a need to understand how multiple risks interrelate in vulnerable populations ofpregnant women.

According to syndemic theory [12], when risk factors cluster together, the combination of these risk factors interacts to produce worse outcomes than any risk factor alone. The notion of syndemics was first applied to intersecting risks among individuals living with HIV, particularly MSM or men who have sex with men [13], but recently has been extended theoretically to the co-occurrence of multiple risk factors in pregnant women in low-resourced global settings [14, 15].Limited empirical studies that explicitly describe psychosocial “syndemics” during pregnancy have tended to consider only two risk factors at once, such as HIV and unintended pregnancy [16] or HIV and food insecurity [17]. Pregnant women living with HIV—many of whom reside in sub-Saharan Africa [18]—often bear a heavy burden of multiple intersecting psychosocial disadvantages [ 19, 20] and may represent a particularly vulnerable population facing unique and additional risks, including HIV-related stigma [21]. These multiple intersecting risks are relevant not only for maternal well-being but also prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission (PMTCT) [22].

To date, many syndemic studies have used relatively basic methods for characterizing the presence of multiple risks [23], often summing them together to produce an index of cumulative risk. While useful, such methods tend to consider all risk factors equally and/or additively influential [24], without capturing the complexity of interdependence among these factors, including how they mutually influence each other to varying degrees [25]. Given that one major recommendation has been to explicitly model interactions between risk factors [26], strategies are needed to conceptualize the complex interplay of psychosocial risk factors, as consistent with syndemic theory and in order to guide the appropriate modeling of potential interactions. One promising methodology is network analysis. Network analysis is an approach that mathematically estimates simultaneous relationships between all variables—or nodes—within a network [27]. Network analysis has been used to characterize interpersonal networks [28] and is increasingly employed in psychological research to investigate symptom-based connections within and across mental disorders [29]. However, to our knowledge, it has not been applied to complex relationships between ecological risk factors. A better understanding of such relationships would allow for potential identification of key factors that are highly influential and could be targeted for maximum impact in social/ public health interventions. Such interventions are critical in low- and middle-income country (LMIC) settings where resources are limited.

This study sought to use network modeling to characterize the co-occurrence of psychosocial risks during pregnancy among HIV-positive women living in KwaZulu-Natal (KZN), South Africa, which has the world’s highest rates of HIV among pregnant women [30].

Methods

Participants and Procedures

The study was conducted in a large urban township in eThekwini District, KZN, South Africa. All participants were pregnant women enrolled in PMTCT care at an antenatal clinic of a large local district hospital. During recruitment between May 10,2013 and June 2,2014, all potential participants were screened for eligibility by a female research assistant fluent in both isiZulu and English, in a way that did not interfere with their medical care. Eligibility criteria for the study included (1) age between 18 and 45, (2) third trimester of pregnancy (28 weeks or more), (3) current antenatal care at the study site, (4) self-reported HIV-positive status, (5) fluency in isiZulu or English, and (6) access to a phone and willingness to be contacted by phone. Written informed consent was obtained from all women who were eligible and willing to participate. Recruitment continued until the target sample size of 200 for the parent study was met [31].

Participants were surveyed by an interviewer using a structured questionnaire, regarding their demographic information, depression, stigma, social support, violence exposure, and other factors related to their PMTCT care. Surveys were conducted in isiZulu or English according to participant preference in a private room at the study site, and all women were compensated with 70 ZAR (approximately 10 USD at the time) for participating. All study procedures performed in this study involving human participants were approved by the Ethics Committee at University of Witwatersrand (Johannesburg, South Africa) and Partners (Massachusetts General Hospital) Human Research Committee (Boston, USA) and were in accordance with the ethical standards of the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Measures

We included specific risk factors based on available data; while these risk factors do not comprehensively represent all possible risk factors that women may face during pregnancy (e.g., food insecurity), the included variables were selected based on existing literature, our prior qualitative work in this setting, and for their putative contributions to pregnancy-related risk in this setting [5, 32–36]. We did not measure substance use, which has often been implicated in previous syndemic literature in women’s perinatal health [14], though our prior work in KZN suggests that women in this setting do not show high levels of drinking during pregnancy, as in other areas of South Africa such as Cape Town [37]. Where multiple variables were conceptually interrelated, we included them rather than selecting a single variable for inclusions, as network analyses can account for these relationships while detecting their respective associations.

Low Income

A multicategory variable measuring household monthly income was coded into a dichotomous variable in which monthly incomes below 500 Rand (approximately 40 US dollars) were classified as low-income status. Income included money received for work, government grants, other income, and gifts.

Younger Age at Childbearing

In order to include age as a potential risk factor in the network, rather than simply including continuous years of age as a covariate, self-reported age was coded dichotomously so that participants below 21 years of age were classified as being of younger age at childbearing. Using a cutoff of 21 years allowed us to classify a reasonable number of participants within this range (12%), while also relying on a cutoff that has previously been used to establish age of majority in South Africa [38].

Lower Educational Attainment

To index relatively lower education, self-reported years of education were coded dichotomously so that participants who did not endorse at least 12 years of schooling (i.e., completed secondary education) were classified as having lower educational attainment. Again, this cutoff allowed us to include a sizeable proportion of participants (7%) while relying on a rational cutoff.

Unemployment

Participants self-reported employment status, with those lacking current employment classified as unemployed.

Unintended Pregnancy

Unintended pregnancy was measured using one question from the 2009 CDC Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS) [39], which asked, “Thinking back to just before you got pregnant, how did you feel about becoming pregnant?” Responses were re-coded into a dichotomous variable to reflect (1) no intention for current pregnancy (“did not want to be pregnant now or at any time in the future” or “wanted to be pregnant later”) or (0) otherwise (“wanted to be pregnant now,” “wanted to be pregnant sooner,” “did not care either way,” or “do not know”).

Distress About Pregnancy

Distress about pregnancy was assessed using one question from PRAMS [39], which asked, “How did you feel when you found out you were pregnant?” Responses were re-coded into a dichotomous variable to reflect (1) definite distress (“very unhappy to be pregnant” or “unhappy to be pregnant”) or (0) otherwise (“not sure/didn’t mind,” “happy to be pregnant,” “very happy to be pregnant,” or “do not know”).

Antenatal Depression

Depression during pregnancy was assessed using a 16-item depression subscale derived from the 25-item Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HCSL) [40], validated for use with HIV-positive populations in various cross-cultural settings, including South Africa [41]. This subscale was previously adapted [42] to include an additional item on how much the participant cares about his/her health. Items are scored on a severity scale ranging from 1 (“not at all”) to 4 (“extremely”) and averaged to create a total score between 1 and 4, with higher scores indicating greater depressive symptoms. Internal consistency was high (α = 0.86). For descriptive purposes, a cutoff of > 1.75 was applied to the total scores to establish clinically significant depressive symptoms [43].

Internalized HIV Stigma

The six-item Internalized AIDS-Related Stigma Scale [44] was utilized to measure individuals’ perceived HIV stigma. Items describing internal representations of HIV stigma, such as self-defacing beliefs and negative perceptions of individuals living with HIV/AIDS, are coded dichotomously as (1) “agree” or (0) “disagree,” with possible summary scores ranging from 0 to 6. This scale has been validated in South Africa [45] and showed good internal consistency in this sample (α = 0.75). For brevity, “HIV stigma” will herein be used to refer to internalized HIV-related stigma throughout the manuscript.

Violence Exposure

Exposure to physical violence was assessed using a single dichotomous item, “In the last year, have you been hit, slapped, kicked, or otherwise physically hurt by someone?” from the Abuse Assessment Screen [46, 47].

Lack of Social Support

A modified 10-item version of the Duke-UNC Functional Social Support Questionnaire was used to evaluate availability of emotional, informational, and tangible support [48, 49]. This scale has been used with HIV-positive women in sub-Saharan Africa [50]. Items are rated from (1) “never” to (4) “as much as I would like” and summed to yield a continuous total score ranging from 10 to 40, with good internal consistency (α = 0.75). Items were reverse scored so that higher scores reflect greater lack of social support. Given that distribution was initially skewed right, a square root function was applied to all scores for normalization.

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive analyses were initially conducted in SPSS (IBM SPSS Statistics v24, USA) to characterize sample characteristics and hypothesized risk factors. Network analysis was then conducted in R using the mixed graphical modeling mgm package [51] to estimate associations between risk factors, adjusting for variable type and the presence of all other variables in the network. The following binary risk factors were modeled as two-level categorical variables: violence exposure, low income, unintended pregnancy, distress about pregnancy, younger age, lower education, and unemployment. The remaining scale-based risk factors were modeled as continuous variables: depression, HIV stigma, and lack of social support. The mgm package computes conditional independence relationships between mixed variables that can be represented in undirected graphical models [51] and plotted in qgraph [52], where each variable is represented as a node in the network and pairwise connections between variables are represented as edges. A statistical penalty was applied to the mgm fit algorithm to produce a relatively sparse network in which potentially spurious edges are reduced to zero [53] using a λ regularization parameter selected using tenfold cross-validation, with the k parameter set at 2 to estimate pairwise relationships.

The resulting plot layout in qgraph was arranged using the Fruchterman and Reingold algorithm [54], which features more strongly connected nodes in the center of the graph and less strongly connected nodes on the periphery of the graph. First, the overall network and all non-zero edges were inspected. For reporting, edges from this cross-validated model were compared with those generated using a more sparse extended Bayesian information criterion (EBIC) approach, with different levels of the EBIC tuning hyperparameter for regularization (gamma = 0.10, 0.20, and 0.50, in order of increasing stringency) [55]. Second, community detection analyses were conducted to identify subclusters of risk factors using the igraph R package [56] and the walktrap algorithm [57]. Third, centrality statistics for the main network were examined to assess the relative influence of each risk factor in the network, in terms of node strength (i.e., sum of edge weights connected to a particular node), closeness (i.e., average of a node’s distance to all other nodes), and betweenness (i.e., frequency in which a node lies directly in between, or connects, two other nodes). Fourth, the predict function in mgm was used to obtain predictability estimates for each risk factor. Predictability refers to the extent to which each variable can be explained by all other variables in the estimated network [58], using either the proportion of explained variance for continuous variables or a measure of normalized accuracy for binary variables, which captures the degree to which a variable is determined by neighboring variables above and beyond an intercept-only model [58]. Estimates are provided on a scale of zero to 1, where 1 reflects full predictability. Finally, to assess stability of the main network, the bootnet package [59] with mgm specification was used to compute non-parametric bootstrapped intervals around estimated network edges and edge difference significance tests, using 1000 bootstrap samples.

Results

Descriptive Results

All 200 participants were HIV-positive pregnant women, with the majority being black and Zulu-speaking. Key demographic and psychosocial risk factors are summarized in Table 1. On average, participants were 28 years old (range 18–40 years), and 12% were under 21 years of age. The majority (77%) described their pregnancy as unintended, while 39% reported feeling initial distress about this pregnancy. Twenty-six percent met the working cutoff for clinically significant symptoms of antenatal depression. One in five participants reported exposure to physical violence in the past year.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics

| Variable | N (%) | Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Unintended pregnancy | 153 (77%) | – |

| 2. Distress about pregnancy | 78 (39%) | 28 (5) |

| 3. Antenatal depression | 48 (24%) | 1.58 (0.5) |

| 4. HIV stigma | – | 2.4 (1.8) |

| 5. Violence exposure | 40 (20%) | – |

| 6. Lack of social support | – | 15.3 (5.5) |

| 7. Lower education (<12 years) | 14 (7%) | 12(1.6) |

| 8. Unemployment | 145 (73%) | – |

| 9. Lower income (< 500 ZAR) | 63 (32%) | – |

| 10. Younger age (<21 years) | 23 (12%) | 28 (5) |

Network Analyses

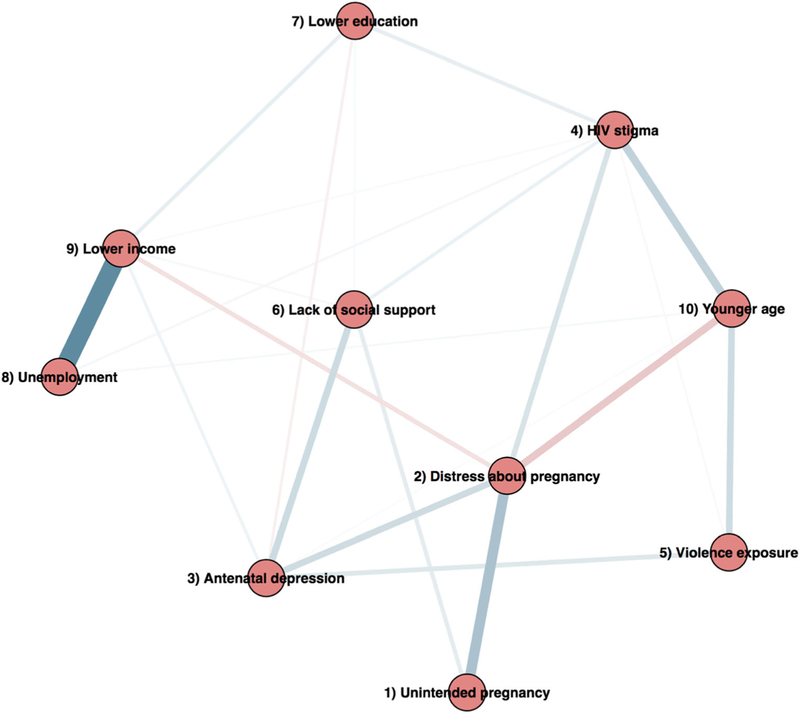

The resulting network (Fig. 1) shows interconnections between psychosocial risk factors. Edge weights are summarized in descending order of absolute strength and across varying levels of regularization in Table 2. In the main estimated network, unintended pregnancy was strongly associated with distress about pregnancy (b = 0.58), which in turn was connected to all but three other risk factors in the network. Specifically, distress about pregnancy was linked with higher levels of antenatal depression (b =0.33) and HIV stigma (b =0.27) and was paradoxically associated with older age (b = − 0.38) and higher income (b = − 0.21) though each of the proposed risk factors (i.e., younger age, lower income) was in fact associated with greater HIV stigma. Lower income was strongly connected with unemployment (b = 1.11). Unintended pregnancy was also associated with lack of social support (b = 0.19), which was itself independently linked to higher levels of antenatal depression (b = 0.35), HIV stigma (b = 0.14), and lower income (b = 0.06). In turn, antenatal depression was connected to violence exposure (b =0.12) and lower income (b = 0.07). According to community detection analyses (Supplementary Fig. D1), unemployment and lower income formed one cluster reflecting socioeconomic risk.; unintended pregnancy, distress about pregnancy, antenatal depression, and lack of social support formed a second cluster reflecting psychosocial distress; HIV stigma, violence exposure, and younger age formed a third cluster reflecting miscellaneous social risks; and lower education was not included in any cluster, though was most connected to HIV stigma.

Fig. 1.

Visualized network of psychosocial risk factors. Strength of each conditional dependency is reflected in weight or intensity of the pairwise edge. Positive edges shown in blue, negative edges in red (in color figure)

Table 2.

Non-zero edges in the network across network estimation approaches

| Variable | Variable | Cross-validated | Gamma 0.10 | Gamma 0.20 | Gamma 0.50 | Sign |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8. Unemployment | 9. Lower income | 1.11* | 0.74 | 0.74 | 0.74 | + |

| 1. Unintended pregnancy | 2. Distress about pregnancy | 0.58* | 0.53 | 0.53 | 0.53 | + |

| 4. HIV stigma | 10. Younger age | 0.42 | – | – | – | + |

| 2. Distress about pregnancy | 10. Younger age | 0.38* | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.18 | – |

| 3. Antenatal depression | 6. Lack of social support | 0.35* | 0.3 | 0.28 | 0.23 | + |

| 5. Violence exposure | 10. Younger age | 0.34 | – | – | – | + |

| 2. Distress about pregnancy | 3. Antenatal depression | 0.33* | 0.29 | 0.22 | 0.18 | + |

| 2. Distress about pregnancy | 4. HIV stigma | 0.27* | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.08 | + |

| 3. Antenatal depression | 5. Violence exposure | 0.23* | 0.12 | 0.03 | – | + |

| 2. Distress about pregnancy | 9. Lower income | 0.21* | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.10 | – |

| 1. Unintended pregnancy | 6. Lack of social support | 0.19* | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.06 | + |

| 4. HIV stigma | 7. Lower education | 0.17 | – | – | – | + |

| 7. Lower education | 9. Lower income | 0.16 | – | – | – | + |

| 4. HIV stigma | 6. Lack of social support | 0.14* | 0.02 | 0.02 | – | + |

| 3. Antenatal depression | 9. Lower income | 0.12* | 0.07 | – | – | + |

| 3. Antenatal depression | 7. Lower education | 0.10 | – | – | – | – |

| 4. HIV stigma | 8. Unemployment | 0.07 | – | – | – | + |

| 6. Lack of social support | 9. Lower income | 0.06 | – | – | – | + |

| 8. Unemployment | 10. Younger age | 0.06 | – | – | – | + |

| 4. HIV stigma | 5. Violence exposure | 0.05 | – | – | – | + |

| 6. Lack of social support | 7. Lower education | 0.05 | – | – | – | + |

| 4. HIV stigma | 9. Lower income | 0.04 | – | – | – | + |

| 3. Antenatal depression | 10. Younger age | 0.04 | – | – | – | + |

Edge weights in descending order by strength, expressed in absolute values. Sign refers to direction of association between two variables. Gamma refers to the value of the hyperparameter used to adjust regularization in the EBIC network models

Associations detected across both cross-validated and EBIC-based network models, highlighted in results

According to centrality statistics (Fig. 2), the most central risk factor in the network was distress about pregnancy. In terms of strength—how strongly a variable was connected to all other nodes, reflecting overall influence in the network—distress about pregnancy had the highest cumulative strength of connections to other variables, followed by lower income and unemployment. In terms of closeness—how close, on average, a variable was connected to all other nodes, reflecting direct influence within the network—distress about pregnancy was on average the closest to other nodes in the network, followed by younger age, antenatal depression, and unintended pregnancy. In terms of betweenness—how often a variable lies directly between two other nodes, and thus serves a central role in connecting other variables in the network—distress about pregnancy showed the highest levels of betweenness, followed by lower income and antenatal depression.

Fig. 2.

Network centrality statistics for each risk factor

As summarized in Table 3 and depicted in Supplementary Materials Fig. B1, predictability of individual nodes [58] ranged between 18% (HIV stigma) and 30% (antenatal depression) of variance explained for continuous variables and 70% (distress about pregnancy) to 93% (lower education) in terms of normalized accuracy for binary variables. Network stability analyses revealed sizeable and overlapping distributions around edge weights (Supplementary Materials Fig. C1), as corroborated by edge difference significance tests (Supplementary Materials Fig. C2), suggesting caution in interpreting relative edge sizes. However, numerous edges persisted across varying degrees of regularization—such as distress about pregnancy and antenatal depression, and antenatal depression and lack of social support (Table 2)—suggesting particularly robust connections.

Table 3.

Predictability of individual risk factors by the full estimated network

| Variable | Predictability (between 0 and 1) | Type |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Unintended pregnancy | 0.77 | Normalized accuracy |

| 2. Distress about pregnancy | 0.70 | Normalized accuracy |

| 3. Antenatal depression | 0.30 | Variance explained |

| 4. HIV stigma | 0.18 | Variance explained |

| 5. Violence exposure | 0.80 | Normalized accuracy |

| 6. Lack of social support | 0.26 | Variance explained |

| 7. Lower education | 0.93 | Normalized accuracy |

| 8. Unemployment | 0.73 | Normalized accuracy |

| 9. Lower income | 0.74 | Normalized accuracy |

| 10. Younger age | 0.89 | Normalized accuracy |

Network estimated using tenfold cross-validation

Discussion

In a sample of 200 HIV-positive pregnant women in South Africa, a variety of psychosocial risks were documented, including elevated rates of depression, unintended pregnancy, poverty, and violence exposure. Network analysis revealed that these psychosocial risk factors were connected through a web of associations, featuring distress about pregnancy at the center of this network. Findings illustrate the complex interdependent nature of multiple psychosocial risks during pregnancy and highlight specific factors with particular influence that may be key targets for perinatal intervention.

Notably, women in this sample reported high levels of un-intended pregnancy, with most reporting that they had not intended to become pregnant. Despite these high rates, a relatively smaller proportion of women reported initial distress about their pregnancy, suggesting that only about half of those with unintended pregnancies may have difficulty accepting this news. This subset of women might be important to identify, as distress about pregnancy was the most central risk factor in this network and associated with several other psychosocial risks, including antenatal depression. While it is possible that pregnancy-related distress led to feelings of depression in these mothers, it is also possible that women with pre-existing depression were more vulnerable to general distress regarding unexpected life events. However, directional causality cannot be established from this cross-sectional data, which instead has generated a hypothesis about the central role of emotional aspects of unintended pregnancies among women in this setting.

Findings served to consolidate known associations between risk factors while further accounting for their simultaneous relationships in the presence of co-occurring factors. For example, IPV exposure has been associated with depressive symptoms during pregnancy [60], as observed in this study, though the typically robust size of this association may have been attenuated when accounting for other risk factors such as lack of social support. Lack of social support, which showed a substantial association with antenatal depression in this sample, has also been linked to depression during pregnancy. Findings complement those from a recent study in pregnant South African women [61], which found that lack of social support interacted with another marker of poverty, food insecurity, to predict antenatal depression—supporting the need to account for interactive influences of multiple risk factors. While HIV stigma has been related to antenatal depression [62], this study suggested that its influence on depression or vice versa might be indirectly mediated through other proximal risk factors. Recent IPV was also not highly connected to other risk factors, potentially due to its simple binary measurement and/or to the relatively common nature of these exposures in low-resourced South African townships [63, 64].

Surprisingly, we found that sociodemographic risk factors such as low income and younger age were inversely associated with distress about pregnancy; results suggest that when adjusting for other risk factors, unintended pregnancy might be particularly distressing for someone who is older (not of younger age) and has greater financial means (not of lower income). This could be a statistical artifact since younger age and low income were each positively related to HIV stigma, which was associated with distress about pregnancy. On the other hand, it could be that younger women are experiencing their first pregnancy and happy to confirm their fertility status, while those from the lowest income category might be eligible for governmental assistance through child support grants [65], thus offsetting anticipated stressors of having a child. Finally, internalized HIV stigma was independently associated with pregnancy-related distress on top of these other factors, suggesting that HIV status and perceived stigma may be an additional dimension of psychosocial risk to consider for mothers living with HIV [66].

This study had a number of limitations to note. First, we relied on data from an existing study focused broadly on HIV and pregnancy, for which some psychosocial indicators (e.g., violence, income status) were not measured in depth. While our depression measure has been validated for research with perinatal populations in African countries, it was not specifically designed for use in the perinatal period like other existing measures [67]. We also wanted to study theoretically hypothesized risk factors and so used rational cutoffs to dichotomize continuous variables on an absolute scale such as age, though we separately verified that results were broadly consistent when using the continuous version of these variables. Second, we drew on a relatively small sample size for network analysis, which may affect stability of results. Results thus should not be interpreted for strong clinical/policy implications—however, they have generated hypotheses about plausible links between multiple risk factors in this population, and the potential importance of unintended pregnancy and related distress as a marker for broader risk, which can be tested further. Third, as mentioned previously, directionality of observed relationships has not been established. Some static risk factors (e.g., age, income) may tend to precede others, but other factors (e.g., depression) may both contribute to and be influenced by others in the network. This precludes definite conclusions about upstream versus downstream factors and the ability to draw strong inferences of where precisely to intervene. Network analysis studies that incorporate factors measured across time, or other studies that draw on network analysis findings to inform longitudinal structural model testing, may provide necessary corroborating evidence. While the focus of this study was to characterize the interrelationships of these risk indicators during pregnancy, future prospective studies should also be designed to examine prospective relevance for postpartum health outcomes.

Despite its limitations, this study has potential to inform future research and intervention. While the goal of this study was to visualize the interdependence of multiple psychosocial risk factors, future applications of this method could use network results to derive more precise predictors of MCH outcomes, potentially weighted by their influence in the network. In terms of clinical intervention, our study suggests that it is possible to identify the most influential risk factors in a vulnerable population. Identifying influential risk factors is especially critical in LMICs where resources are limited. Combined interventions that address a number of key MCH domains have been shown to be efficacious even in low-resourced areas of South Africa but are intensive to deliver [68]. Targeting factors that are central to syndemic networks may create the largest impact across risk factors without having to comprehensively address each one. The observed centrality of distress about pregnancy suggests the clinical relevance of assessing emotional aspects of unintended pregnancies in this population. Alternatively, factors that are more peripheral to the network are likely to be more exogenous factors that could benefit from upstream intervention and have ripple effects across other risk factors. For example, lack of social support was the only risk factor directly linked to unintended pregnancy; it is possible that working with women to identify and leverage specific sources of support, albeit limited, and to discuss family planning issues may have a protective effect against unintended pregnancy and its downstream consequences.

In conclusion, our results characterize a network of psychosocial risks during pregnancy in a sample of HIV-positive women in South Africa. Emotional aspects of unintended pregnancy emerged as a central feature of this network, suggesting that unintended pregnancy in contexts of internalized HIV stigma, sociodemographic risk, and lack of social support is particularly distressing and may even contribute to further risks to MCH, such as depression. Prevention of unintended pregnancies and interventions for coping with unplanned pregnancies may be especially critical in populations where multiple risks intersect. In addition, efforts targeting single risk factors (e.g., depression) should recognize the influence of other contextual variables and consider an integrated, multilevel approach to supporting the well-being of HIV-infected women during the perinatal period.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to study participants and MatCH Research Unit staff on this project and support from the Prince Mshiyeni Memorial Hospital. We thank Jonas Haslbeck for his initial guidance on mixed graphical models. We thank Elsa Sweek for her generous submission support.

Funding This study was funded by a National Institute of Mental Health grant (K23 MH096651) to Dr. Psaros, and Dr. Safren’s time was supported by grant K24 DA040489.

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval This study has been approved by the appropriate ethics committees—Ethics Committee at University of Witwatersrand (Johannesburg, South Africa) and Partners (Massachusetts General Hospital) Human Research Committee (Boston, USA)—and has therefore been performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

Publisher’s Note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material The online version of this article (https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-019-09774-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- 1.Scorgie F, Blaauw D, Dooms T, Coovadia A, Black V, Chersich M. “I get hungry all the time”: experiences of poverty and pregnancy in an urban healthcare setting in South Africa. Glob Health. 2015;11:37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tanya-Nagahawatte N, Goldenberg RL. Poverty, maternal health, and adverse pregnancy outcomes. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2008;1136: 80–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Collins NL, Dunkel-Schetter C, Lobel M, Scrimshaw SC. Social support in pregnancy: psychosocial correlates of birth outcomes and postpartum depression. JPers Soc Psychol. 1993;65:1243–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shah PS, Shah J. Maternal exposure to domestic violence and pregnancy and birth outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analyses. J Women’s Health. 2010;19:2017–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alder J, Fink N, Bitzer J, Hösli I, Holzgreve W. Depression and anxiety during pregnancy: a risk factor for obstetric, fetal and neonatal outcome? A critical review of the literature. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2007;20:189–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patel V, Rahman A, Jacob KS, Hughes M. Effect of maternal mental health on infant growth in low income countries: new evidence from South Asia. BMJ. 2004;328:820–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rahman A, Harrington R, Bunn J. Can maternal depression increase infant risk of illness and growth impairment in developing countries? Child Care Health Dev. 2002;28:51–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gibbs CM, Wendt A, Peters S, Hogue CJ. The impact of early age at first childbirth on maternal and infant health. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2012;26:259–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kearney MS, Levine PB. Why is the teen birth rate in the United States so high and why does it matter? J Econ Perspect. 2012;26: 141–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kendall-Tackett KA. Violence against women and the perinatal period: the impact of lifetime violence and abuse on pregnancy, postpartum, and breastfeeding. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2007;8: 344–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O’Hara MW. Social support, life events, and depression during pregnancy and the puerperium. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1986;43: 569–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Singer M, Clair S. Syndemics and public health: reconceptualizing disease in bio-social context. Med Anthropol Q. 2003;17:423–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singer. AIDS and the health crisis of the US urban poor; the perspective of critical medical anthropology. Soc Sci Med. 1994;39:931–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Russell BS, Eaton LA, Petersen-Williams P. Intersecting epidemics among pregnant women: alcohol use, interpersonal violence, and HIV infection in South Africa. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2013;10:103–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Singer. Development, coinfection, and the syndemics of pregnancy in sub-Saharan Africa. Infect Dis Poverty. 2013;2:26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tsuyuki K, Gipson JD, Urada LA, Barbosa RM, Morisky DE. Dual protection to address the global syndemic of HIV and unintended pregnancy in Brazil. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2016;42:271–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garcia J, Hromi-Fiedler A, Mazur RE, Marquis G, Sellen D, Lartey A, et al. Persistent household food insecurity, HIV, and maternal stress in peri-urban Ghana. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gouws E, Stanecki KA, Lyerla R, Ghys PD. The epidemiology of HIV infection among young people aged 15–24 years in southern Africa. AIDS. 2008;22:S5–S16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ashaba S, Kaida A, Coleman JN, Burns BF, Dunkley E, O’Neil K, et al. Psychosocial challenges facing women living with HIV during the perinatal period in rural Uganda. PLoS One. 2017;12: e0176256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blaney NT, Fernandez MI, Ethier KA, Wilson TE, Walter E, Koenig LJ, et al. Psychosocial and behavioral correlates of depression among HIV-infected pregnant women. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2004;18:405–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kotzé M, Visser M, Makin J, Sikkema K, Forsyth B. Psychosocial variables associated with coping of HIV-positive women diagnosed during pregnancy. AIDS Behav. 2013;17:498–507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gourlay A, Birdthistle I, Mburu G, Iorpenda K, Wringe A. Barriers and facilitating factors to the uptake of antiretroviral drugs for prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. J Int AIDS Soc. 2013;16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tsai AC, Burns BF. Syndemics of psychosocial problems and HIV risk: a systematic review of empirical tests of the disease interaction concept. Soc Sci Med. 2015;139:26–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Halkitis PN, Moeller RW, Siconolfi DE, Storholm ED, Solomon TM, Bub KL. Measurement model exploring a syndemic in emerging adult gay and bisexual men. AIDS Behav. 2013;17: 662–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tsai AC, Mendenhall E, Trostle JA, Kawachi I. Co-occurring epidemics, syndemics, and population health. Lancet. 2017;389: 978–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tsai AC, Venkataramani AS. Syndemics and health disparities: a methodological note. AIDS Behav. 2016;20:423–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Palla G, Derényi I, Farkas I, Vicsek T. Uncovering the overlapping community structure of complex networks in nature and society. Nature. 2005;435:814–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Borgatti SP, Mehra A, Brass DJ, Labianca G. Network analysis in the social sciences. Science. 2009;323:892–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Borsboom D, Cramer AO. Network analysis: an integrative approach to the structure of psychopathology. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2013;9:91–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.National Department of Health. The 2013 National Antenatal Sentinel HIV Prevalence Survey, South Africa [Internet]. 2015. Available from: http://www.health-e.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/Dept-Health-HIV-High-Res-7102015.pdf. Accessed 15 Nov 2016

- 31.Psaros C, Mosery N, Smit JA, Luthuli F, Gordon JR, Greener R, et al. PMTCT adherence in pregnant south African women: the role ofdepression, social support, stigma and structural barriers to care. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 2014;30:A61–1. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cook JA, Grey D, Burke J, Cohen MH, Gurtman AC, Richardson JL, et al. Depressive symptoms and AIDS-related mortality among a multisite cohort of HIV-positive women. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:1133–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cooper PJ, Tomlinson M, Swartz L, Woolgar M, Murray L, Molteno C. Post-partum depression and the mother-infant relationship in a South African peri-urban settlement. Br J Psychiatry. 1999;175:554–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Peltzer K, Ramlagan S. Perceived stigma among patients receiving antiretroviral therapy: a prospective study in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. AIDS Care. 2011;23:60–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rahman A, Iqbal Z, Harrington R. Life events, social support and depression in childbirth: perspectives from a rural community in the developing world. Psychol Med. 2003;33:1161–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Simbayi LC, Kalichman S, Strebel A, Cloete A, Henda N, Mqeketo A. Internalized stigma, discrimination, and depression among men and women living with HIV/AIDS in Cape Town, South Africa. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64:1823–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Watt MH, Eaton LA, Choi KW, Velloza J, Kalichman SC, Skinner D, et al. “It’s better for me to drink, at least the stress is going away”: perspectives on alcohol use during pregnancy among South African women attending drinking establishments. Soc Sci Med. 2014;116:119–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mahery P Factsheet: at what age can children act independently from their parents and whendo they need their parents’ consent or assistance?—Google Search [Internet]. Cape Town: Children’s Institute, Child Rights in Focus; 2006. July Available from: http://www.childlinesa.org.za/wp-content/uploads/age-of-independence-of-children-from-their-parents.pdf. Accessed 20 Nov 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS): Phase 6 Standard Questions [Internet]. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2010. [cited 2017 Jul 17] Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/prams/pdf/questionnaire/phase6_standardquestions.pdf. Accessed 15 Jan 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Derogatis LR, Lipman RS, Rickels K, Uhlenhuth EH, Covi L. The Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSCL): a self-report symptom inventory. Syst Res Behav Sci. 1974;19:1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kagee A, Martin L. Symptoms of depression and anxiety among a sample of South African patients living with HIV. AIDS Care. 2010;22:159–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bolton P, Wilk CM, Ndogoni L. Assessment of depression prevalence in rural Uganda using symptom and function criteria. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2004;39:442–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Winokur A, Winokur DF, Rickels K, Cox DS. Symptoms of emotional distress in a family planning service: stability over a four-week period. Br J Psychiatry. 1984;144:395–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kalichman SC, Simbayi LC, Cloete A, Mthembu PP, Mkhonta RN, Ginindza T. Measuring AIDS stigmas in people living with HIV/AIDS: the internalized AIDS-related stigma scale. AIDS Care. 2009;21:87–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kalichman SC, Simbayi LC, Jooste S, Toefy Y, Cain D, Cherry C, et al. Development of a brief scale to measure AIDS-related stigma in South Africa. AIDS Behav. 2005;9:135–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Abuse Assessment Screen: Guide to Clinical Preventive Services [Internet]. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2005. Available from: www.ahrq.gov/clinic/uspstfix.htm. Accessed 15 Jan 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 47.The New York City Department of Health and Ment Hyg City Health Information [Internet]. 2007. p. 7–14. Available from: http://www.nyc.gov/html/doh/downloads/pdf/chi/chi26-2.pdf. Accessed 15 Jan 2017

- 48.Antelman G, Fawzi MCS, Kaaya S, Mbwambo J, Msamanga GI, Hunter DJ, et al. Predictors of HIV-1 serostatus disclosure: a prospective study among HIV-infected pregnant women in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. AIDS. 2001;15:1865–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Broadhead WE, Gehlbach SH, De Gruy FV, Kaplan BH. The Duke-UNC Functional Social Support Questionnaire: measurement of social support in family medicine patients. Med Care. 1988;26:709–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Antelman G, Kaaya S, Wei R, Mbwambo J, Msamanga GI, Fawzi WW, et al. Depressive symptoms increase risk of HIV disease progression and mortality among women in Tanzania. JAIDS J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;44:470–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Haslbeck JM, Waldorp LJ. mgm: structure estimation for time-varying mixed graphical models in high-dimensional data. J Stat Softw 2016; [Google Scholar]

- 52.Epskamp S, Cramer AO, Waldorp LJ, Schmittmann VD, Borsboom D. qgraph: network visualizations of relationships in psychometric data. J Stat Softw. 2012;48:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Epskamp S, Borsboom D, Fried EI. Estimating psychological networks and their accuracy: a tutorial paper. Behav Res Methods. 2018;50:195–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fruchterman TM, Reingold EM. Graph drawing by force-directed placement. Softw Pract Exp. 1991;21:1129–64. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dziak JJ, Coffman DL, Lanza ST, Li R. Sensitivity and specificity of information criteria. PeerJ Prepr. 2017; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Csardi G, Nepusz T. The igraph software package for complex network research. Inter J Comp Syst. 2006;1695:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pons P, Latapy M. Computing communities in large networks using random walks. Int Symp Comput Inf Sci Springer. 2005: 284–93. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Haslbeck JMB, Fried EI. How predictable are symptoms in psychopathological networks? A reanalysis of 18 published datasets. Psychol Med. 2017;47:2767–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Epskamp S, Fried EI. Bootstrap methods for various network estimation routines [Internet]. 2017. [cited 2017 Jul 17] Available from: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/bootnet/bootnet.pdf. Accessed 1 Dec 2016

- 60.Tsai AC, Tomlinson M, Comulada WS, Rotheram-Borus MJ. Intimate partner violence and depression symptom severity among South African women during pregnancy and postpartum: population-based prospective cohort study. PLoS Med. 2016;13: e1001943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tsai AC, Tomlinson M, Comulada WS, Rotheram-Borus MJ. Food insufficiency, depression, and the modifying role of social support: evidence from a population-based, prospective cohort of pregnant women in peri-urban South Africa. Soc Sci Med. 2016;151:69–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Brittain K, Mellins CA, Phillips T, Zerbe A, Abrams EJ, Myer L, et al. Social support, stigma and antenatal depression among HIV-infected pregnant women in South Africa. AIDS Behav. 2017;21: 274–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dunkle KL, Jewkes RK, Brown HC, Yoshihama M, Gray GE, McIntyre JA, et al. Prevalence and patterns of gender-based violence and revictimization among women attending antenatal clinics in Soweto, South Africa. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;160: 230–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Groves AK, Moodley D, McNaughton-Reyes L, Martin SL, Foshee V, Maman S. Prevalence, rates and correlates of intimate partner violence among South African women during pregnancy and the postpartum period. Matern Child Health J. 2015;19:487–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Government of South Africa. Child support grant. 2014. [cited 2017 Jul 17]; Available from: http://www.gov.za/services/child-care-social-benefits/child-support-grant. Accessed 30 March 2017

- 66.Crankshaw TL, Voce A, King RL, Giddy J, Sheon NM, Butler LM. Double disclosure bind: complexities of communicating an HIV diagnosis in the context of unintended pregnancy in Durban, South Africa . AIDS Behav. 2014;18:53–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression: development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry. 1987;150:782–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tomlinson M, Rotheram-Borus MJ, Le Roux IM, Youssef M, Nelson SH, Scheffler A, et al. Thirty-six-month outcomes of a generalist paraprofessional perinatal home visiting intervention in South Africa on maternal health and child health and development. Prev Sci. 2016;17:937–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.