Introduction

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM)[1] is a type of metabolic disease caused by metabolic disorders in the endocrine system and characterized by hyperglycemia. Insufficient insulin secretion and insulin resistance are the basic pathologic characteristics of T2DM. According to the International Diabetes Federation (IDF),[2] the prevalence of diabetes among adults aged 20–79 in 2017 was 8.8% from a total population of 425 million, which will reach 629 million by 2045. Additionally, it is estimated that approximately half of all adult patients worldwide have not been diagnosed as of 2017. In 2017, approximately 4 million adults died of diabetes, and 46.1% of patients died before reaching the age of 60 years. These data show that the number of patients with diabetes is increasing at an alarming rate and have come to represent a challenge for human health. In addition, T2DM accounts for approximately 95% of the total population of diabetes, which leads to significant losses for human and economic health.[3] T2DM is a chronic disease that can cause a series of complications that can lead to death.[4] Therefore, preventing or delaying the occurrence of complications is the main purpose of treating T2DM, and the key link for those suffering from diabetes is to maintain blood glucose levels within the normal range.[5] At present, the treatment of T2DM mainly depends on lifestyle intervention[6] (such as nutrition therapy and physical activity), oral medication[7] (such as biguanides, sulfonylureas, and α-glucoside inhibitors), injected drugs[8] (such as insulin and glucagon-like peptide-1 [7–36] amide [GLP-1] agonists), surgical treatment,[9] and complementary and alternative treatment.[10]

T2DM is known as a major “Xiao-Ke disease” in ancient Chinese books. And Chinese have used herbal medicines to treat the diseases for more than 1500 years. There is a growing body of research showing that herbal medicine can effectively treat T2DM.[11–13] In this study, we reviewed the therapeutic action of herbal medicine in T2DM via anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidation characteristics, regulation of blood lipid metabolism, anti-glucose effects, and other mechanisms [Figures 1–5].

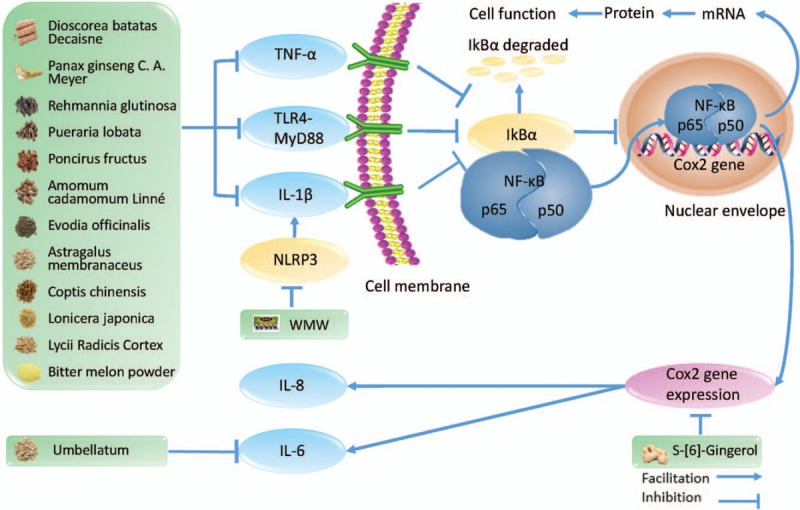

Figure 1.

The anti-inflammatory effect of herbal medicine in type 2 diabetes mellitus. TNF-α: tumor necrosis factor-α; TLR4-MyD88: toll-like receptor 4-myeloid differential protein-88; IL-1β: interleukin-1β; NLRP3: NACHT, LRR, and PYD domain-containing protein 3; WMW: Wu-Mei-Wan; NF-κB: nuclear transcription factor kappa B; IκBα: inhibitor of NF-κB; COX2: cyclo-oxgenase 2; IL-8: interleukin-8; IL-6: interleukin-6.

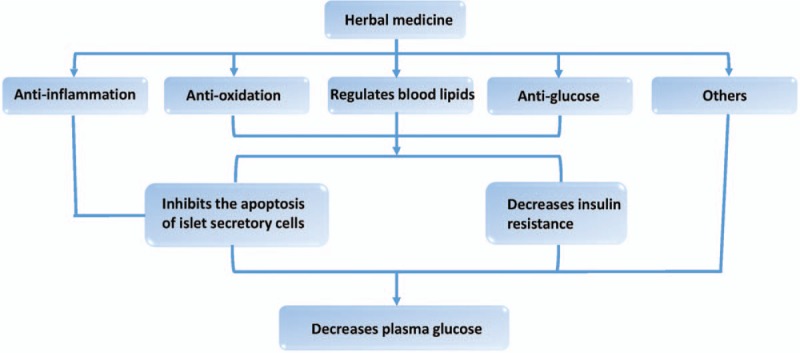

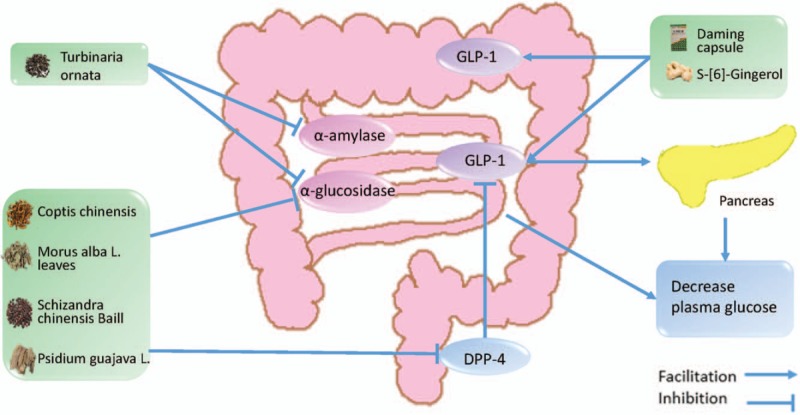

Figure 5.

The effect of herbal medicine in type 2 diabetes mellitus.

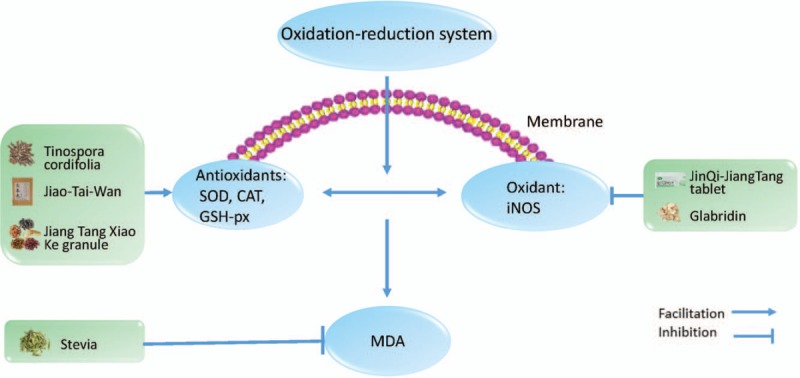

Figure 2.

The anti-oxidation effect of herbal medicine in type 2 diabetes mellitus. SOD: superoxide dismutase; CAT: catalase; GSH-px: glutathione peroxidase; iNOS: inducible nitric oxide synthase; MDA: malondialdehyde.

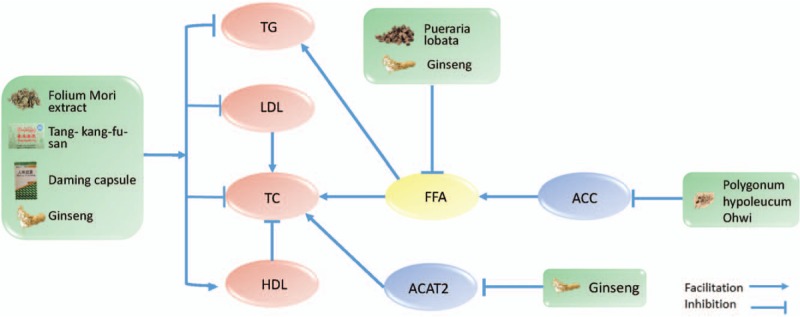

Figure 3.

The regulating blood lipids effect of herbal medicine in type 2 diabetes mellitus. TG: triglyceride; LDL: low-density lipoprotein; TC: total cholesterol; HDL: high-density lipoprotein; FFA: free fatty acids; ACC: acetyl-coenzyme A carboxylase; ACAT2: acetyl-coenzyme A acetyltransferase 2.

Figure 4.

The anti-glucose effect of herbal medicine in type 2 diabetes mellitus. GLP-1: glucagon-like peptide-1 (7–36) amide; DPP-4: dipeptidyl-peptidase 4.

Anti-inflammatory effects

The state of low-grade inflammation is a typical manifestation of T2DM that can generate increased production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin-1β (IL-1β), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α).[14,15] These inflammatory cytokines not only damage the beta cells of the pancreas, leading to decreased insulin secretion, but also contribute to insulin resistance through the decrease in glucose extraction and in utilization efficiency of the peripheral tissues.[14,16,17] Therefore, the inhibition of inflammatory cytokines is seen as an important step for treating T2DM.[18] Herbal medicine has gradually attracted attention. IL-6 is an important pro-inflammatory cytokine in the pathogenesis of T2DM. Additionally, the levels of IL-6 can directly reflect the level of inflammation in patients with T2DM.[16,19]Memecylon umbellatum[20] is a type of Melastomataceae, which is often used to treat diabetes. This herb is also known as the iron wood tree, which grows in the Western Peninsula and in most coastal areas. Reports[20] have shown that the extract of M. umbellatum produces a hypoglycemic effect in diabetic models designed by Amalraj and Ignacimuthu in 1998. Additionally, in 2017, M. umbellatum was used again by Sunil et al[21] for an experiment on mice. Additionally, they found that it clearly reduced the serum IL-6 level and insulin resistance in high-fat diet-induced obese mice, which fully demonstrated that M. umbellatum can treat diabetes by lowering the level of IL-6. The nuclear transcription factor kappa B (NF-κB) participates in the inflammatory response by controlling gene expression to promote immunity. Blocking the NF-κB-mediated signaling pathway can effectively reduce the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines.[22]Lycii Radicis Cortex is the root bark of Lycium barbarum Linnaeus or Lycium chinense Miller, which can be used to treat inflammation, diabetes, and other diseases. The study by Xie et al[23] has shown that the extracts of Lycii Radicis Cortex can effectively inhibit NF-κB activity to inhibit an inflammatory response. In China, ginger is used as both a spice and an herbal remedy for disease. S-[6]-Gingerol is an important substance that causes ginger to produce a pungent smell. It has been found that S-[6]-Gingerol can suppress cyclo-oxygenase 2 expression via blocking the NF-κB-mediated signaling pathway to inhibit IL-6 and IL-8 expression in cytokine-stimulated HuH7 cells.[24] The inhibitor of NF-κB (IκBα) is the inhibitory protein of NF-κB. The inactivation of the IκBα protein can effectively inhibit the expression of NF-κB and reduce the inflammatory response induced by the NF-κB-mediated signaling pathway.[25]Momordica charantia L., often known as bitter melon, is a plant that grows in Asia and can be used as both a food and an herb. Dietary fiber, carbohydrate, protein, and water are the main components of bitter melon, in addition to micronutrients such as calcium, phenolics, flavonoids, and saponins.[25] As early as 2003, bitter melon's hypoglycemic effect has been confirmed.[26] In 2006, Bai et al[25] found that bitter melon powder can inhibit the activation of NF-κB by inhibiting IκBα degradation, thus significantly inhibiting inflammation. JinQi-JiangTang tablets, an effective Chinese patent medicine with anti-glucose properties, containing refined extracts from Astragalus membranaceus (Leguminosae), Coptis chinensis (Ranunculaceae), and Lonicera japonica (Caprifoliaceae), can reduce the degradation of the IκBα to inhibit the activity of NF-κB.[13] The studies have also found that herbal medicine can reduce NF-κB activation via inhibiting IL-1β, TNF-α, and toll-like receptor 4 to treat T2DM.[15,19,27–31]

Anti-oxidation properties

The oxidation–reduction (REDOX) process is an important process in the human body and is closely related to the body's metabolism and functioning. In a physiologic state, the body is in a state of redox homeostasis. When the human body is subjected to various types of harmful stimuli, the homeostasis is broken, causing oxidative stress to damage the human body.[32] Oxidative stress in patients with T2DM has been confirmed.[33] Islet secretory cells are naturally weak in antioxidant activity as the activity of various antioxidant enzymes in the islet is lower than that of other tissues.[34] Therefore, oxidative stress is most harmful to human pancreatic cells, causing diabetes. Moreover, increasing studies[35,36] have shown that oxidative stress can induce insulin resistance, which makes more evident that oxidative stress is an important factor in the onset or exacerbation of T2DM. Therefore, anti-oxidative therapy is helpful for the treatment of T2DM. Superoxide dismutase (SOD), glutathione peroxidase (GSH-px), and catalase (CAT) are important enzymes that can effectively counter the free radicals in the human body.[33,37]Tinospora cordifolia (Hook and Thomson) is part of the Menispermaceae family. Sangeetha et al[38] showed that T. cordifolia can increase SOD and CAT activities in experimentally induced T2DM in rats, and the group treated with 200 mg/kg performs better compared to the group treated with 100 mg/kg. Jiao-Tai-Wan is a famous herbal formula in China that mainly consists of 2 herbs: Rhizoma coptidis and Cinnamomum cassia. Chen et al have found that this formula has exerted an antioxidant effect by significantly increasing activities of SOD, GSH-px, and CAT.[39] The Jiang Tang Xiao Ke (JTXK) granule is a type of Chinese patent medicine that contains Radix Salviae Miltiorrhizae (Dan Shen), Radix Rehmanniae (Di Huang), Panax ginseng (Ren Shen), R. coptidis (Huang Lian), and Fructus corni (Shan Yu Rou) for treating diabetes mellitus. Zhang et al[40] found that giving JTXK in combination with metformin, compared to metformin alone, can significantly improve antioxidant capacity because of suppression of the decrease of SOD activity in diabetic mice. Nitric oxide (NO) is an important bioactive product in the human body that can exacerbate oxidative stress. Additionally, inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) is an important enzyme that promotes the formation of NO.[41] Therefore, inhibition of iNOS can effectively prevent the further development of oxidative stress. Liu et al[13] have also found that the JinQi-JiangTang tablet not only has anti-inflammatory effects but can also reduce the activity of iNOS by regulating REDOX system in palmitate-induced insulin resistant L6 myotubes. It has been shown by Yehuda et al[42] that glabridin can also regulate the synthesis of iNOS in macrophage-like cells. It is well known that malondialdehyde (MDA) is a product of lipid peroxidation and is widely used to reflect the level of oxidative stress in the body. Assaei et al[43] have found that the aquatic extract of Stevia can effectively decrease the concentration of MDA.

Regulating blood lipids effects

Lipotoxicity is a lipid metabolism disorder that causes or aggravates insulin resistance and pancreatic cell dysfunction.[44] As early as 2001, McGarry[45] suggested that the fundamental cause of the pathophysiologic changes of T2DM pathogenesis a the disorder of the lipid metabolism, which he suggested naming T2DM diabetes mellipodtus. Therefore, lipid metabolism plays an important role in the pathogenesis of T2DM. Previous studies have found that herbal medicine plays an important role in reducing blood triglyceride (TG), total cholesterol (TC), and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) levels and increasing the high-density lipoprotein (HDL) level.[46,47] The Folium Mori extract is an extract of Morus alba L., which is an herb used to treat diabetes in China. Cai et al[46] have found that it can effectively reduce serum TG, TC, and LDL levels in a T2DM rat model. Qurs Tabasheer is a polyherbal formulation containing Portulaca oleracea, Rosa damascene, Punica granatum, Bambusa arundinacea, and Lactuca sativa Linn. Danish Ahmed et al found that can reduce TG and TC levels in diabetic rats.[48] Tang-kang-fu-san is a hypoglycemic formula in Tibetan medicine, in which gallic acid and curcumin are the main active ingredients. Duan et al[47] found that it can effectively reduce the serum TG and LDL level and increase the HDL of mice in T2DM. The Daming capsule is a type of Chinese patent medicine developed under the guidance of traditional Chinese theory. It has been proven by Zhang et al[49] that the Daming capsule can effectively reduce serum TG and LDL levels and increase HDL levels in diabetic mice. Fatty acids are an important ingredient in the synthesis of TG. Therefore, the increase of free fatty acids (FFA) can increase the level of TG in the blood.[50] Yeo et al[29] have also found that an aqueous extract of herbal compounds containing Pueraria lobata, Panax ginseng C.A. Meyer, Rehmannia glutinosa, Poncirus fructu, Dioscorea batatas Decaisne, Evodia officinalis, and Amomum cadamomum Linné can decrease plasma FFA. Acetyl-coenzyme A carboxylase (ACC) is an important substance involved in the metabolism of fatty acids. Additionally, inhibition of ACC can effectively reduce the levels of FFA in the blood.[51] Therefore, ACC inhibitors have excellent potential for treating diabetes.[52] Chen et al[51] found that an ethanol extract of Polygonum hypoleucum Ohwi can effectively inhibit ACC in C57BL/6J mice that were given a high-fat diet. Acetyl-coenzyme A (CoA) acetyltransferase 2 (ACAT2) is an important enzyme involved in TC generation and metabolism, and inhibiting ACAT2 can reduce TC levels in the blood.[53] Banz et al[54] have found that ginseng has significantly reduced the levels of TG and TC in male Zucker diabetic fatty rats. In addition, Saba et al[55] have found that ginseng extract ameliorates hypercholesterolemia by attenuating ACAT2.

Anti-glucose effects

According to the American Diabetes Association's (ADA's) “Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2018,” fasting plasma glucose ≥7.0 mmol/L and 2-h post-prandial plasma glucose ≥ 11.1 mmol/L is the important diagnostic basis for T2DM. Chronic hyperglycemia can damage the pancreatic β-cell, which leads to pancreatic β-cell glucotoxicity.[56] The damage of pancreatic β-cell can lead to a decrease in insulin secretion, which further aggravates hyperglycemia. It is important to stabilize the blood glucose level of T2DM so that it remains in a reasonable range.[5] Okchun-san is an herbal formula used to treat diabetes in Korea. Chang et al have found that it can lower blood glucose in db/db mouse model.[57] Bofu-tsusho-san is an herbal formula of Kampo, and Morimoto et al[58] have found that it is effective against hyperglycemia in KKAy mice. Under normal physiologic conditions, the body adjusts the insulin secretion of pancreatic β-cells to fight the hyperglycemia caused by food absorption after eating. The pancreatic β-cell function of T2DM is impaired, and it is difficult to produce enough insulin to fight the hyperglycemia.[56] Therefore, the post-prandial plasma glucose of in patients with T2DM is higher than normal and can even develop an acute complication of diabetes. A study in the last century[59] has found that α-amylase and α-glucosidase play important roles in the body to absorb glucose. Inhibiting α-amylase and α-glucosidase can effectively reduce post-prandial hyperglycemia to achieve treat T2DM.[60,61] In recent years, it has been shown that more types of herbal medicine can inhibit α-amylase and α-glucosidase, which can lower post-prandial hyperglycemia. Acer pycnanthum is a type of Aceraceae known as “Hana-noki” in Japan. Honma et al[62] found that the extract of the leaves of A. pycnanthum can lower hyperglycemic by inhibiting α-glucosidase. Lodhrasavam is an Ayurvedic anti-diabetic formulation that contains 19 herbal ingredients. Butala et al[63] found that Lodhrasavam has effectively anti-α-amylase and anti-α-glucosidase properties in a simulation of gastro-intestinal digestion. GLP-1[64] is a type of peptide secreted by L cells of the gastrointestinal mucosa that promotes insulin synthesis and secretion, thereby reducing blood glucose. Additionally, GLP-1 promotes insulin secretion in a positive correlation with blood glucose concentration: the higher the blood glucose is, the stronger the effect is; the lower the blood glucose is, the weaker the effect is. GLP-1 plays an important role in regulating blood glucose homeostasis.[65] Samad et al[66] have found that [6]-Gingerol increased insulin secretion by strengthening the GLP-1-mediated secretion pathway in Lepr db/db T2DM mice. Zhang et al[49] have also found that the Daming capsule can increase the secretion of GLP-1 in diabetic mice. Dipeptidyl-peptidase 4 (DPP-4)[67] is a type of high-specific serine protease that, exists in the form of a dimer. GLP-1 is a natural substrate of DPP-4. Therefore, DPP-4 can rapidly degrade GLP-1 to deactivate the function of GLP-1. As a DDP-4 inhibitor, sitagliptin[68] has been widely used in the clinical treatment of T2DM and has achieved good results. Wang and Chiang[69] have found that an herbal formula used to treat diabetes that contains C. chinensis, M. alba L. leaves, Schizandra chinensis Baill, and Psidium guajava L. can inhibit a-glucosidase and DPP-4.

Other effects

Herbal medicine can also treat T2DM in other ways. It is well known that the gut microbiome is a large system in the human body. It is estimated that there are more than 1000 types of gut microbiomes in the human body, which is more than 100 times the number of human genes.[70] In recent years, the association between gut microbiomes and T2DM has attracted more and more attention. It has been preliminarily confirmed that gut microbiome disorders are closely related to insulin resistance and the onset of T2DM.[71,72] Therefore, can herbal medicine treat T2DM by regulating the gut microbiome? Many people have studied this problem. Wang et al[72] have found that Ephedra sinica can effectively reduce the fasting blood glucose by changing the composition of gut microbiota, especially Roseburia, Blautia, and Clostridium. Qijian mixture[73] is a new herbal formula for treating T2DM that contains Ramulus euonymi, P. lobata, A. membranaceus, and C. chinensis. Gao et al[73] have demonstrated the effectiveness and safety of the Qijian mixture in a T2DM model rat. They found that the Qijian mixture has enormously rich Bacteroidetes, which may be closely related to its role in treating T2DM. Adiponectin is a cytokine that comes from adipocytes and improves insulin resistance.[74] The use of adiponectin as a treatment strategy for T2DM has been increasingly recognized.[75] However, up to now, adiponectin biologic agents have not been used in medical practice. However, herbal medicine has been reported to improve the expression of adiponectin in treating diabetes. Cirsium japonicum DC is a type of herb used in hemostasis; however, Liao et al[76] found that flavones isolated from C. japonicum DC can also exert an anti-diabetic effect by improving severe adiponectin expressions in diabetic rats. Dangguiliuhuang decoction (DGLHD) is an herbal formula that is widely used to treat diabetes. It contains C. chinensis, golden cypress, Radix Rehmanniae preparata, Angelica, Scutellaria baicalensis, and A. membranaceus and the amount of A. membranaceus is twice that of other herbs. Cao et al[77] have found that DGLHD increased the expression of adiponectin.

Conclusion

The T2DM is a global health problem that causes significant distress for patients.[78] Although many biologic agents have been developed to treat T2DM, attention to herbal medicine in the treatment of T2DM has been growing. In this article, we summarized the roles of some herbs, herbal extracts, and herbal formulas in the treatment of T2DM. Herbal medicine is mainly used to treat T2DM through its anti-inflammatory, anti-oxidation, blood lipid regulation, and anti-glucose properties.

Herbal medicine is superior in its holistic quality, which can treat T2DM through multiple targets, and is a good complementary and alternative treatment for T2DM. However, there are some deficiencies in herbal medicine that need to be studied further. Herbs, especially some herbal formulas, contain a variety of ingredients, and it is difficult to accurately identify the active ingredients and toxic ingredients. Most of the above studies are animal experiments. Large-scale, multicenter clinical studies still lack reliable and detailed information. Furthermore, there have also been few reports on follow-up observations of patients with T2DM treated with herbal medicine. All these questions provide direction for our future research.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

This work was support by a grant from the Special Subject of TCM Science Research of Henan Province (No. 2014ZY01003).

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Author contributions

Pang GM selected topic and wrote the manuscript, Li FX, Yan Y, Zhang Y, Kong LL, Zhu P, Wang KF, Zhang F, and Liu B retrieved material and Lu C designed and modified the article.

Footnotes

How to cite this article: Pang GM, Li FX, Yan Y, Zhang Y, Kong LL, Zhu P, Wang KF, Zhang F, Liu B, Lu C. Herbal medicine in the treatment of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Chin Med J 2019;00:00–00. doi: 10.1097/CM9.0000000000000006

References

- 1.DeFronzo RA, Ferrannini E, Groop L, Henry RR, Herman WH, Holst JJ, et al. Type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2015; 1:15019.doi:10.1038/nrdp.2015.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kowluru A, Kowluru RA. RACking up ceramide-induced islet beta-cell dysfunction. Biochem Pharmacol 2018; 154:161–169. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2018.04.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zimmet P, Alberti KG, Shaw J. Global and societal implications of the diabetes epidemic. Nature 2001; 414:782–787. doi:10.1038/414782a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maletkovic J, Drexler A. Diabetic ketoacidosis and hyperglycemic hyperosmolar state. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 2013; 42:677–695. doi:10.1016/j.ecl.2013.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hickner J. Diabetes care: whose goals are they? J Fam Pract 2014; 63:420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schellenberg ES, Dryden DM, Vandermeer B, Ha C, Korownyk C. Lifestyle interventions for patients with and at risk for type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 2013; 159:543–551. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-159-8-201310150-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tran L, Zielinski A, Roach AH, Jende JA, Householder AM, Cole EE, et al. Pharmacologic treatment of type 2 diabetes: oral medications. Ann Pharmacother 2015; 49:540–556. doi:10.1177/1060028014558289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tran L, Zielinski A, Roach AH, Jende JA, Householder AM, Cole EE, et al. Pharmacologic treatment of type 2 diabetes: injectable medications. Ann Pharmacother 2015; 49:700–714. doi:10.1177/1060028015573010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maleckas A, Venclauskas L, Wallenius V, Lonroth H, Fandriks L. Surgery in the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Scand J Surg 2015; 104:40–47. doi:10.1177/1457496914561140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nahas R, Moher M. Complementary and alternative medicine for the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Can Fam Physician 2009; 55:591–596. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pang B, Zhao LH, Zhou Q, Zhao TY, Wang H, Gu CJ, et al. Application of berberine on treating type 2 diabetes mellitus. Int J Endocrinol 2015; 2015:905749.doi:10.1155/2015/905749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang LX, Liu TH, Huang ZT, Li JE, Wu LL. Research progress on the mechanism of single-Chinese medicinal herbs in treating diabetes mellitus. Chin J Integr Med 2011; 17:235–240. doi:10.1007/s11655-010-0674-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu Q, Liu S, Gao L, Sun S, Huan Y, Li C, et al. Anti-diabetic effects and mechanisms of action of a Chinese herbal medicine preparation JQ-R in vitro and in diabetic KK(Ay) mice. Acta Pharm Sin B 2017; 7:461–469. doi:10.1016/j.apsb.2017.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hameed I, Masoodi SR, Mir SA, Nabi M, Ghazanfar K, Ganai BA. Type 2 diabetes mellitus: from a metabolic disorder to an inflammatory condition. World J Diabetes 2015; 6:598–612. doi:10.4239/wjd.v6.i4.598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang Y, Zhu Y, Gao L, Yin H, Xie Z, Wang D, et al. Formononetin attenuates IL-1beta-induced apoptosis and NF-kappaB activation in INS-1 cells. Molecules 2012; 17:10052–10064. doi:10.3390/molecules170910052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pedersen BK. Anti-inflammatory effects of exercise: role in diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Eur J Clin Invest 2017; 47:600–611. doi:10.1111/eci.12781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Donath MY, Shoelson SE. Type 2 diabetes as an inflammatory disease. Nat Rev Immunol 2011; 11:98–107. doi:10.1038/nri2925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Collier JJ, Burke SJ, Eisenhauer ME, Lu D, Sapp RC, Frydman CJ, et al. Pancreatic beta-cell death in response to pro-inflammatory cytokines is distinct from genuine apoptosis. PLoS One 2011; 6:e22485.doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0022485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Qu D, Liu J, Lau CW, Huang Y. IL-6 in diabetes and cardiovascular complications. Br J Pharmacol 2014; 171:3595–3603. doi:10.1111/bph.12713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Amalraj T, Ignacimuthu S. Evaluation of the hypoglycaemic effect of Memecylon umbellatum in normal and alloxan diabetic mice. J Ethnopharmacol 1998; 62:247–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sunil V, Shree N, Venkataranganna MV, Bhonde RR, Majumdar M. The anti diabetic and anti obesity effect of Memecylon umbellatum extract in high fat diet induced obese mice. Biomed Pharmacother 2017; 89:880–886. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2017.01.182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baker RG, Hayden MS, Ghosh S. NF-kappaB, inflammation, and metabolic disease. Cell Metab 2011; 13:11–22. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2010.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xie LW, Atanasov AG, Guo DA, Malainer C, Zhang JX, Zehl M, et al. Activity-guided isolation of NF-kappaB inhibitors and PPARgamma agonists from the root bark of Lycium chinense Miller. J Ethnopharmacol 2014; 152:470–477. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2014.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li XH, McGrath KC, Tran VH, Li YM, Duke CC, Roufogalis BD, et al. Attenuation of proinflammatory responses by S-[6]-Gingerol via inhibition of ROS/NF-Kappa B/COX2 activation in HuH7 cells. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2013; 2013:146142.doi:10.1155/2013/146142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bai J, Zhu Y, Dong Y. Response of gut microbiota and inflammatory status to bitter melon (Momordica charantia L.) in high fat diet induced obese rats. J Ethnopharmacol 2016; 194:717–726. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2016.10.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yeh GY, Eisenberg DM, Kaptchuk TJ, Phillips RS. Systematic review of herbs and dietary supplements for glycemic control in diabetes. Diabetes Care 2003; 26:1277–1294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu Z, Bruggeman LA. Assaying NF-kappaB activation and signaling from TNF receptors. Methods Mol Biol 2014; 1155:1–14. doi:10.1007/978-1-4939-0669-7_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Verstrepen L, Bekaert T, Chau TL, Tavernier J, Chariot A, Beyaert R. TLR-4, IL-1R and TNF-R signaling to NF-kappaB: variations on a common theme. Cell Mol Life Sci 2008; 65:2964–2978. doi:10.1007/s00018-008-8064-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yeo J, Kang YM, Cho SI, Jung MH. Effects of a multi-herbal extract on type 2 diabetes. Chin Med 2011; 6:10.doi:10.1186/1749-8546-6-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Naimi M, Vlavcheski F, Shamshoum H, Tsiani E. Rosemary extract as a potential anti-hyperglycemic agent: current evidence and future perspectives. Nutrients 2017; 9:E968.doi:10.3390/nu9090968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Park MY, Mun ST. Carnosic acid inhibits TLR4-MyD88 signaling pathway in LPS-stimulated 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Nutr Res Pract 2014; 8:516–520. doi:10.4162/nrp.2014.8.5.516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sies H, Berndt C, Jones DP. Oxidative stress. Annu Rev Biochem 2017; 86:715–748. doi:10.1146/annurev-biochem-061516-045037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rochette L, Zeller M, Cottin Y, et al. Diabetes, oxidative stress and therapeutic strategies. Biochim Biophys Acta 2014; 1840:2709–2729. doi:10.1016/j.bbagen.2014.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tiedge M, Lortz S, Drinkgern J, et al. Relation between antioxidant enzyme gene expression and antioxidative defense status of insulin-producing cells. Diabetes 1997; 46:1733–1742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tangvarasittichai S. Oxidative stress, insulin resistance, dyslipidemia and type 2 diabetes mellitus. World J Diabetes 2015; 6:456–480. doi:10.4239/wjd.v6.i3.456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Evans JL, Goldfine ID, Maddux BA, Grodsky GM. Are oxidative stress-activated signaling pathways mediators of insulin resistance and beta-cell dysfunction? Diabetes 2003; 52:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Newsholme P, Cruzat VF, Keane KN, Carlessi R, de Bittencourt PI., Jr Molecular mechanisms of ROS production and oxidative stress in diabetes. Biochem J 2016; 473:4527–4550. doi:10.1042/bcj20160503c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sangeetha MK, Balaji Raghavendran HR, Gayathri V, Vasanthi HR. Tinospora cordifolia attenuates oxidative stress and distorted carbohydrate metabolism in experimentally induced type 2 diabetes in rats. J Nat Med 2011; 65:544–550. doi:10.1007/s11418-011-0538-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen G, Lu F, Xu L, Dong H, Yi P, Wang F, et al. The anti-diabetic effects and pharmacokinetic profiles of berberine in mice treated with Jiao-Tai-Wan and its compatibility. Phytomedicine 2013; 20:780–786. doi:10.1016/j.phymed.2013.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang Y, An H, Pan SY, Zhao DD, Zuo JC, Li XK, et al. Jiang Tang Xiao Ke Granule, a classic chinese herbal formula, improves the effect of metformin on lipid and glucose metabolism in diabetic mice. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2016; 2016:1592731.doi:10.1155/2016/1592731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Soskic SS, Dobutovic BD, Sudar EM, et al. Regulation of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) and its potential role in insulin resistance, diabetes and heart failure. Open Cardiovasc Med J 2011; 5:153–163. doi:10.2174/1874192401105010153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yehuda I, Madar Z, Leikin-Frenkel A, Tamir S. Glabridin, an isoflavan from licorice root, downregulates iNOS expression and activity under high-glucose stress and inflammation. Mol Nutr Food Res 2015; 59:1041–1052. doi:10.1002/mnfr.201400876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Assaei R, Mokarram P, Dastghaib S, Darbandi S, Darbandi M, Zal F, et al. Hypoglycemic effect of aquatic extract of stevia in pancreas of diabetic rats: PPARgamma-dependent regulation or antioxidant potential. Avicenna J Med Biotechnol 2016; 8:65–74. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yazici D, Sezer H. Insulin resistance, obesity and lipotoxicity. Adv Exp Med Biol 2017; 960:277–304. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-48382-5_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McGarry JD. Banting lecture 2001: dysregulation of fatty acid metabolism in the etiology of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 2002; 51:7–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cai S, Sun W, Fan Y, et al. Effect of mulberry leaf (Folium Mori) on insulin resistance via IRS-1/PI3K/Glut-4 signalling pathway in type 2 diabetes mellitus rats. Pharm Biol 2016; 54:2685–2691. doi:10.1080/13880209.2016.1178779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Duan B, Zhao Z, Lin L, Jin J, Zhang L, Xiong H, et al. Antidiabetic effect of Tibetan medicine Tang-Kang-Fu-San on high-fat diet and streptozotocin-induced type 2 diabetic rats. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2017; 2017:7302965.doi:10.1155/2017/7302965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ahmed D, Sharma M, Mukerjee A, Ramteke PW, Kumar V. Improved glycemic control, pancreas protective and hepatoprotective effect by traditional poly-herbal formulation “Qurs Tabasheer” in streptozotocin induced diabetic rats. BMC Complement Altern Med 2013; 13:10.doi:10.1186/1472-6882-13-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 49.Zhang Y, Li X, Li J, Zhang Q, Chen X, Liu X, et al. The anti-hyperglycemic efficacy of a lipid-lowering drug Daming capsule and the underlying signaling mechanisms in a rat model of diabetes mellitus. Sci Rep 2016; 6:34284.doi:10.1038/srep34284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yang F, Chen G, Ma M, Qiu N, Zhu L, Li J. Fatty acids modulate the expression levels of key proteins for cholesterol absorption in Caco-2 monolayer. Lipids Health Dis 2018; 17:32.doi:10.1186/s12944-018-0675-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chen CH, Chang MY, Lin YS, Lin DG, Chen SW, Chao PM. A herbal extract with acetyl-coenzyme A carboxylase inhibitory activity and its potential for treating metabolic syndrome. Metabolism 2009; 58:1297–1305. doi:10.1016/j.metabol.2009.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Griffith DA, Kung DW, Esler WP, Amor PA, Bagley SW, Beysen C, et al. Decreasing the rate of metabolic ketone reduction in the discovery of a clinical acetyl-CoA carboxylase inhibitor for the treatment of diabetes. J Med Chem 2014; 57:10512–10526. doi:10.1021/jm5016022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Giovannoni MP, Piaz VD, Vergelli C, Barlocco D. Selective ACAT inhibitors as promising antihyperlipidemic, antiathero-sclerotic and anti-Alzheimer drugs. Mini Rev Med Chem 2003; 3:576–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Banz WJ, Iqbal MJ, Bollaert M, Chickris N, James B, Higginbotham DA, et al. Ginseng modifies the diabetic phenotype and genes associated with diabetes in the male ZDF rat. Phytomedicine 2007; 14:681–689. doi:10.1016/j.phymed.2007.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Saba E, Jeon BR, Jeong DH, Lee K, Goo YK, Kim SH, et al. Black ginseng extract ameliorates hypercholesterolemia in rats. J Ginseng Res 2016; 40:160–168. doi:10.1016/j.jgr.2015.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bensellam M, Laybutt DR, Jonas JC. The molecular mechanisms of pancreatic beta-cell glucotoxicity: recent findings and future research directions. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2012; 364:1–27. doi:10.1016/j.mce.2012.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chang MS, Oh MS, Kim DR, Jung KJ, Park S, Choi SB, et al. Effects of okchun-san, a herbal formulation, on blood glucose levels and body weight in a model of type 2 diabetes. J Ethnopharmacol 2006; 103:491–495. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2005.08.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Morimoto Y, Sakata M, Ohno A, Maegawa T, Tajima S. Effects of Byakko-ka-ninjin-to, Bofu-tsusho-san and Gorei-san on blood glucose level, water intake and urine volume in KKAy mice (in Japanese). Yakugaku Zasshi 2002; 122:163–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gray GM. Carbohydrate digestion and absorption. Role of the small intestine. N Engl J Med 1975; 292:1225–1230. doi:10.1056/nejm197506052922308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Taslimi P, Aslan HE, Demir Y, Oztaskin N, Maras A, Gulcin I, et al. Diarylmethanon, bromophenol and diarylmethane compounds: discovery of potent aldose reductase, alpha-amylase and alpha-glycosidase inhibitors as new therapeutic approach in diabetes and functional hyperglycemia. Int J Biol Macromol 2018; 119:857–863. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Olennikov DN, Chirikova NK, Kashchenko NI, Nikolaev VM, Kim SW, Vennos C. Bioactive phenolics of the genus Artemisia (Asteraceae): HPLC-DAD-ESI-TQ-MS/MS profile of the Siberian species and their inhibitory potential against alpha-amylase and alpha-glucosidase. Front Pharmacol 2018; 9:756.doi:10.3389/fphar.2018.00756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Honma A, Koyama T, Yazawa K. Anti-hyperglycaemic effects of the Japanese red maple Acer pycnanthum and its constituents the ginnalins B and C. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem 2011; 26:176–180. doi:10.3109/14756366.2010.486795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Butala MA, Kukkupuni SK, Vishnuprasad CN. Ayurvedic anti-diabetic formulation Lodhrasavam inhibits alpha-amylase, alpha-glucosidase and suppresses adipogenic activity in vitro. J Ayurveda Integr Med 2017; 8:145–151. doi:10.1016/j.jaim.2017.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nadkarni P, Chepurny OG, Holz GG. Regulation of glucose homeostasis by GLP-1. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci 2014; 121:23–65. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-800101-1.00002-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Li X, Qie S, Wang X, Zheng Y, Liu Y, Liu G. The safety and efficacy of once-weekly glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist semaglutide in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systemic review and meta-analysis. Endocrine 2018; 62:535–545. doi:10.1007/s12020-018-1708-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Samad MB, Mohsin M, Razu BA, Hossain MT, Mahzabeen S, Unnoor N, et al. [6]-Gingerol, from Zingiber officinale, potentiates GLP-1 mediated glucose-stimulated insulin secretion pathway in pancreatic beta-cells and increases RAB8/RAB10-regulated membrane presentation of GLUT4 transporters in skeletal muscle to improve hyperglycemia in Lepr(db/db) type 2 diabetic mice. BMC Complement Altern Med 2017; 17:395.doi:10.1186/s12906-017 -1903-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rohrborn D, Wronkowitz N, Eckel J. DPP4 in diabetes. Front Immunol 2015; 6:386.doi:10.3389/fimmu.2015.00386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Derosa G, D’Angelo A, Maffioli P. Sitagliptin in type 2 diabetes mellitus: Efficacy after five years of therapy. Pharmacol Res 2015; 100:127–134. doi:10.1016/j.phrs.2015.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wang HJ, Chiang BH. Anti-diabetic effect of a traditional Chinese medicine formula. Food Funct 2012; 3:1161–1169. doi:10.1039/c2fo30139c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Eckburg PB, Bik EM, Bernstein CN, Purdom E, Dethlefsen L, Sargent M, et al. Diversity of the human intestinal microbial flora. Science 2005; 308:1635–1638. doi:10.1126/science.1110591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kootte RS, Vrieze A, Holleman F, Dallinga-Thie GM, Zoetendal EG, de Vos WM, et al. The therapeutic potential of manipulating gut microbiota in obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Obes Metab 2012; 14:112–120. doi:10.1111/j.1463-1326.2011.01483.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wang JH, Kim BS, Han K, Kim H. Ephedra-treated donor-derived gut microbiota transplantation ameliorates high fat diet-induced obesity in rats. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2017; 14:E555.doi:10.3390/ijerph14060555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gao K, Yang R, Zhang J, Wang Z, Jia C, Zhang F, et al. Effects of Qijian mixture on type 2 diabetes assessed by metabonomics, gut microbiota and network pharmacology. Pharmacol Res 2018; 130:93–109. doi:10.1016/j.phrs.2018.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Long W, Hui Ju Z, Fan Z, Jing W, Qiong L. The effect of recombinant adeno-associated virus-adiponectin (rAAV2/1-Acrp30) on glycolipid dysmetabolism and liver morphology in diabetic rats. Gen Comp Endocrinol 2014; 206:1–7. doi:10.1016/j.ygcen.2014.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lim S, Quon MJ, Koh KK. Modulation of adiponectin as a potential therapeutic strategy. Atherosclerosis 2014; 233:721–728. doi:10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2014.01.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Liao Z, Chen X, Wu M. Antidiabetic effect of flavones from Cirsium japonicum DC in diabetic rats. Arch Pharm Res 2010; 33:353–362. doi:10.1007/s12272-010-0302-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Cao H, Tuo L, Tuo Y, Xia Z, Fu R, Liu Y, et al. Immune and metabolic regulation mechanism of dangguiliuhuang decoction against insulin resistance and hepatic steatosis. Front Pharmacol 2017; 8:445.doi:10.3389/fphar.2017.00445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Unnikrishnan R, Mohan V. Why screening for type 2 diabetes is necessary even in poor resource settings. J Diabetes Complications 2015; 29:961–964. doi:10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2015.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]